Sitagliptin Alleviates Radiation-Induced Kidney and Testis Degeneration in Rats

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Experimental Protocol

2.2. Biochemical Analyses

2.3. Histopathology

2.4. Immunohistochemical Analyses

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Biochemical Analyses

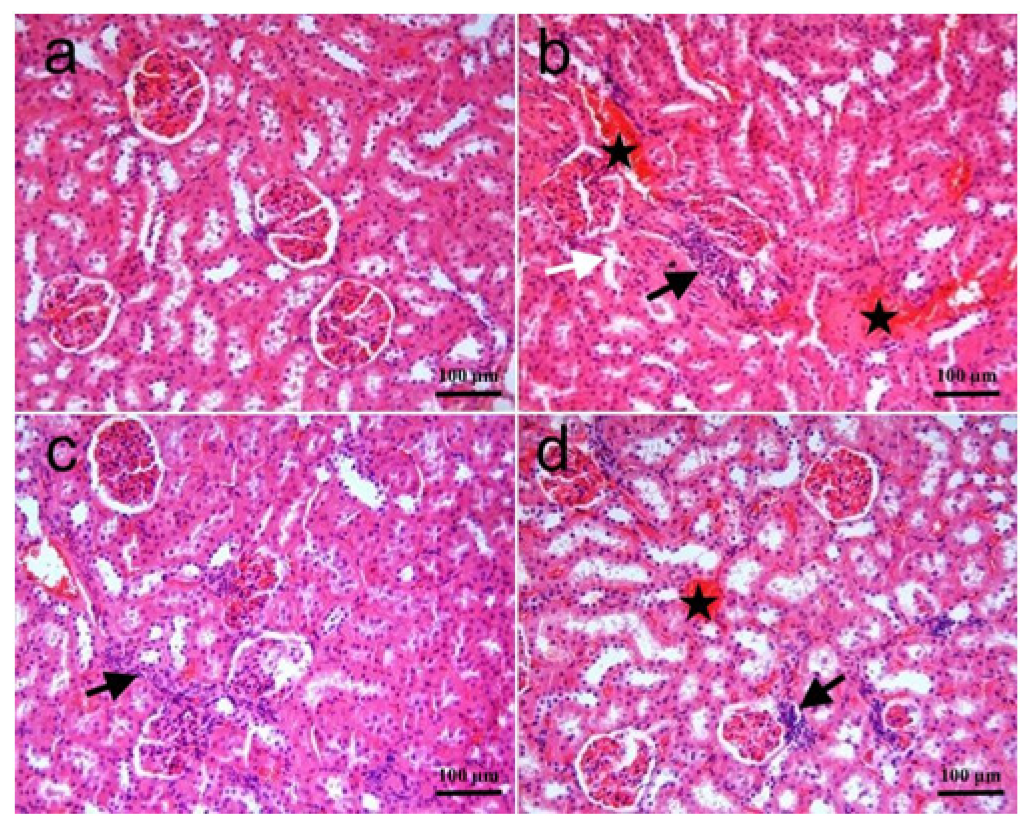

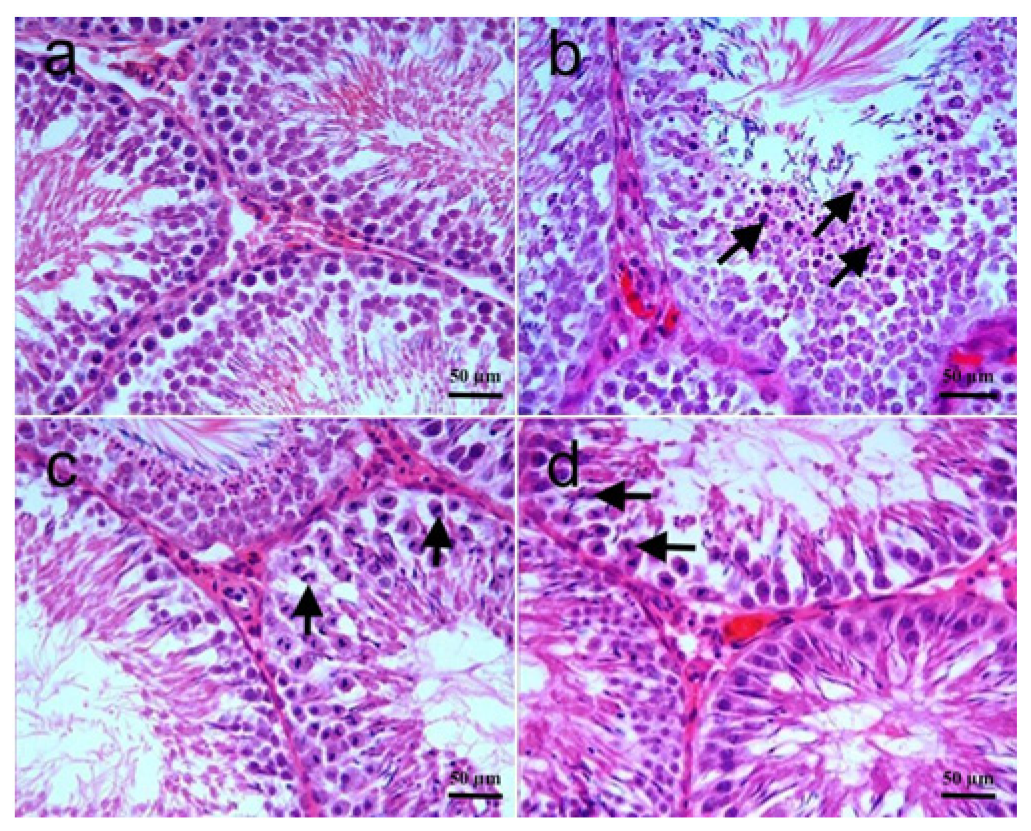

3.2. Histopathology

3.3. Immunohistochemical Analyses

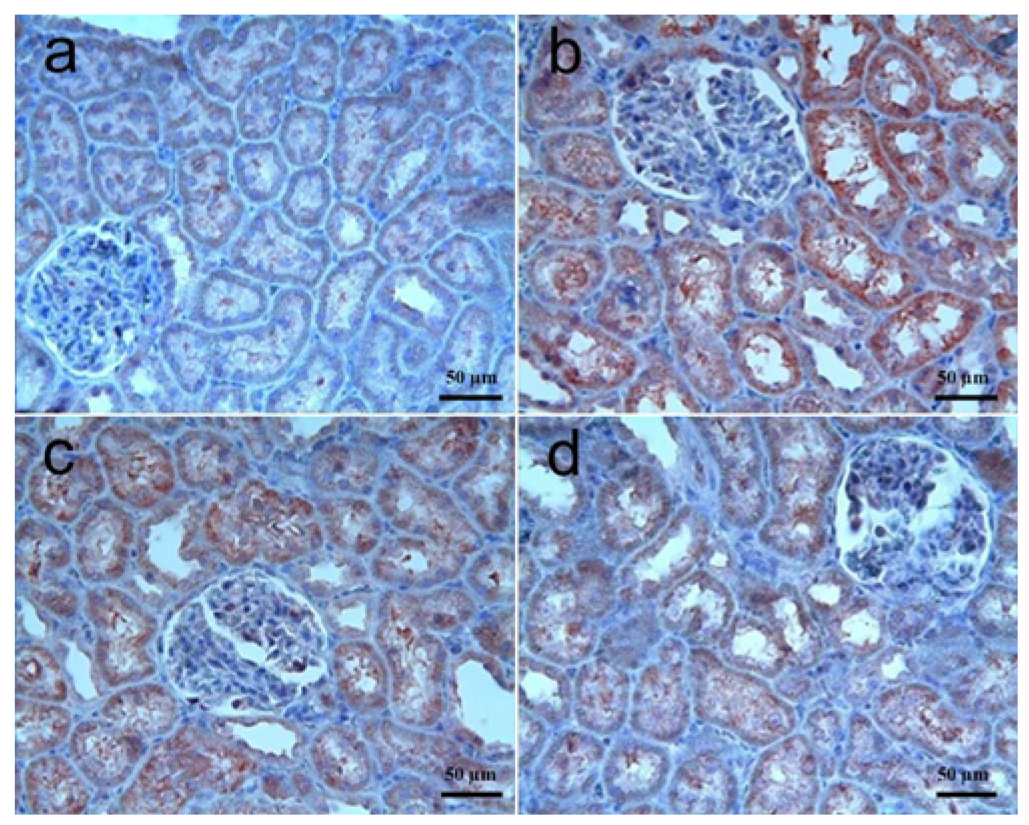

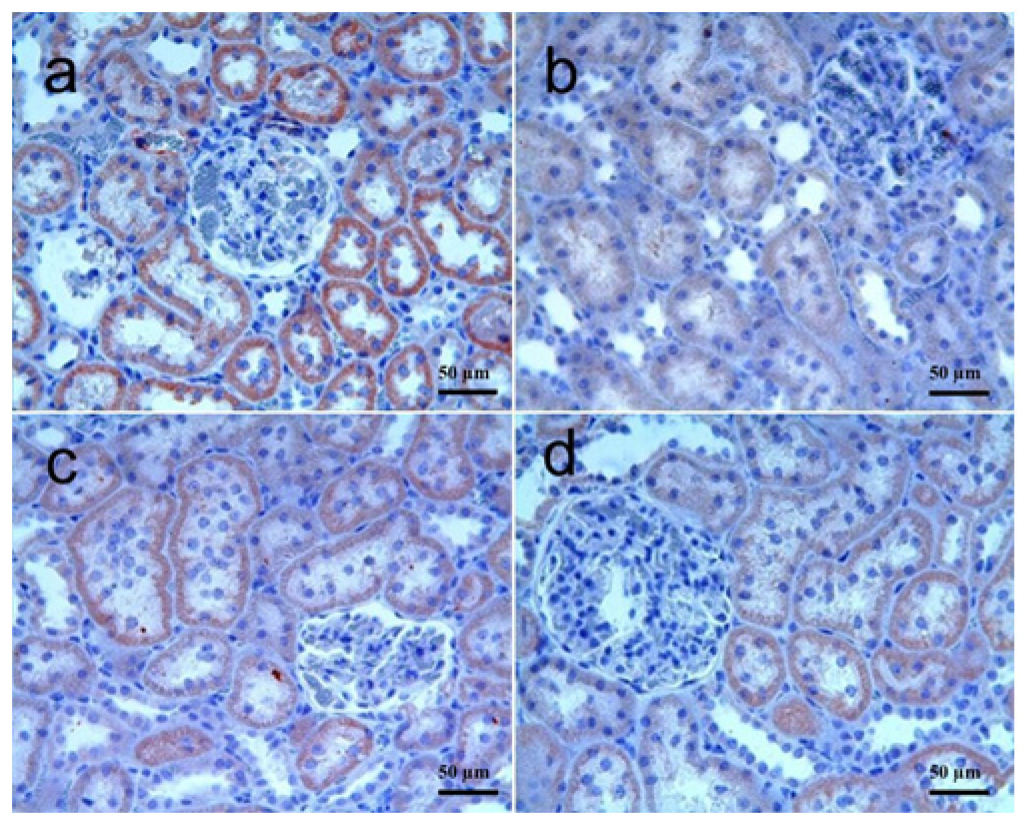

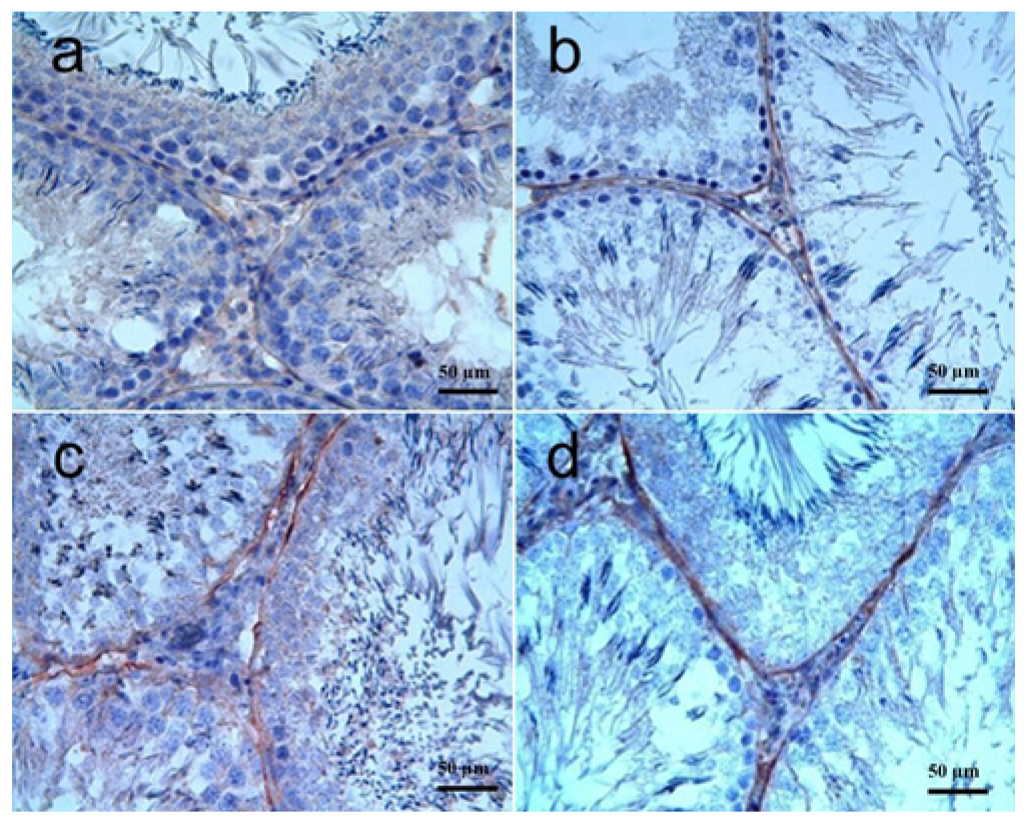

3.3.1. Kidney Tissue

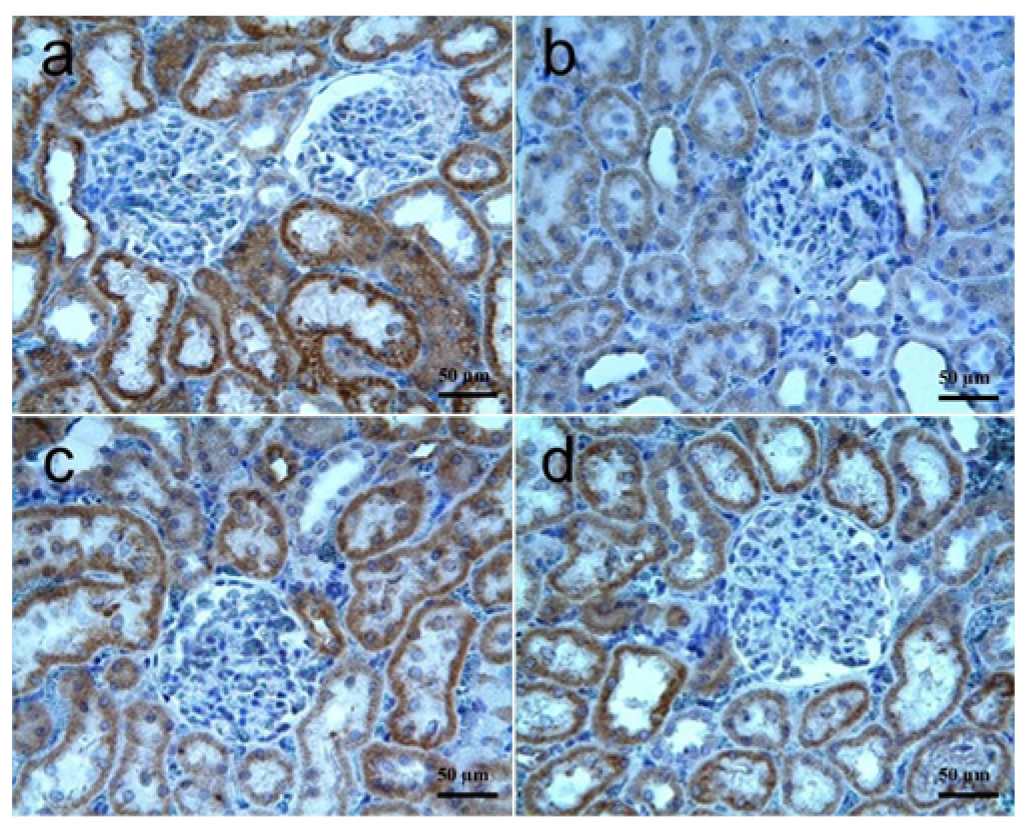

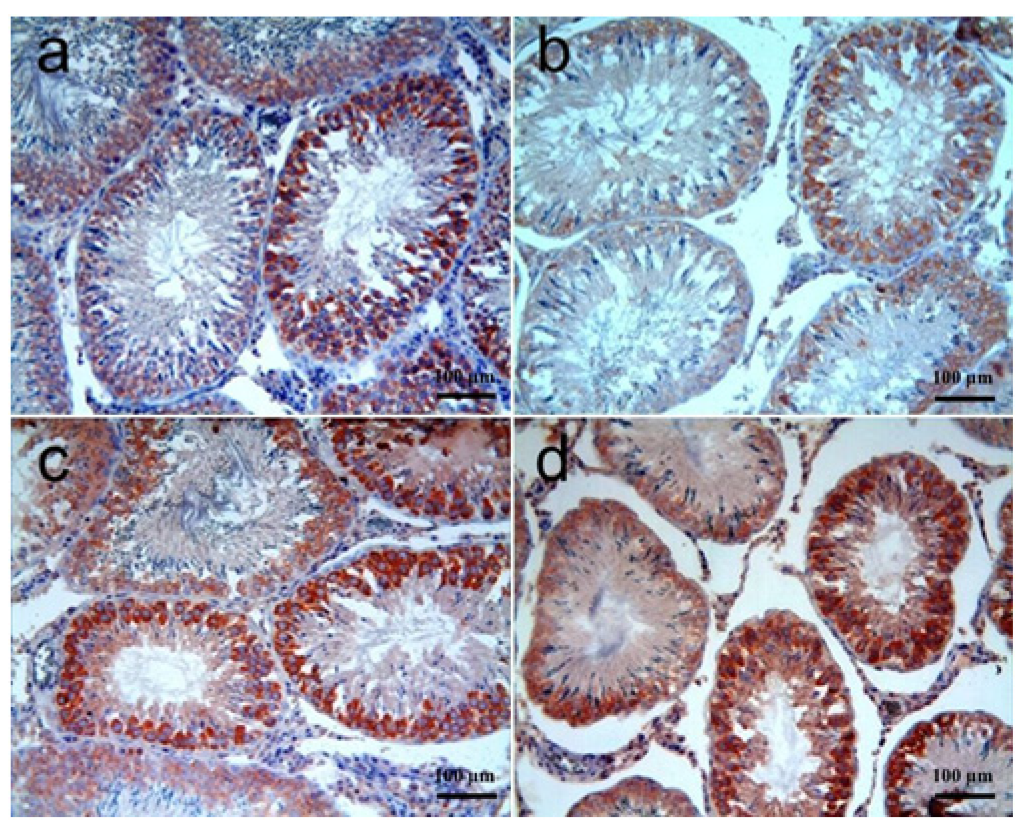

3.3.2. Testis Tissue

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GLP-1 | Glucagon-like peptide-1 |

| GIP | Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide |

| RT | Radiation |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| FGF | Fibroblast growth factor |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered solution |

| DPP4 | Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| CAT | Catalase |

| GPx | Glutathione peroxidase |

| TAS | Total antioxidant status |

| TOS | Total oxidant status |

| OSI | Oxidative state index |

References

- Barazzuol, L.; Coppes, R.P.; van Luijk, P. Prevention and treatment of radiotherapy-induced side effects. Mol. Oncol. 2020, 14, 1538–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, J.Y.C.; Filippi, A.R.; Dabaja, B.S.; Yahalom, J.; Specht, L. Total Body Irradiation: Guidelines from the International Lymphoma Radiation Oncology Group (ILROG). Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2018, 101, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohan, G.; Ayisha Hamna, T.P.; Jijo, A.J.; Saradha Devi, K.M.; Narayanasamy, A.; Vellingiri, B. Recent advances in radiotherapy and its associated side effects in cancer—A review. J. Basic Appl. Zool. 2019, 80, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, J.; Chen, L.; Zeng, Y.; Xiao, G.; Tian, W.; Wu, Q.; Tang, J.; He, S.; Tanzhu, G.; Zhou, R. The scheme, and regulative mechanism of pyroptosis, ferroptosis, and necroptosis in radiation injury. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2024, 20, 1871–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Sun, G.; Wang, Y.; Luo, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, M.; Liu, H.; Lu, X.; Qin, X. Mitigating radiation-induced brain injury via NLRP3/NLRC4/Caspase-1 pyroptosis pathway: Efficacy of memantine and hydrogen-rich water. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 177, 116978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, C.E.; Kendig, C.B.; An, N.; Fazilat, A.Z.; Churukian, A.A.; Griffin, M.; Pan, P.M.; Longaker, M.T.; Dixon, S.J.; Wan, D.C. Role of ferroptosis in radiation-induced soft tissue injury. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Löbrich, M.; Kiefer, J. Assessing the likelihood of severe side effects in radiotherapy. Int. J. Cancer 2006, 118, 2652–2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Zhu, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, P.K.; Gu, Y. Mechanisms of radiation-induced tissue damage and response. MedComm 2024, 5, e725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, P.A. Free Radicals in Biology: Oxidative Stress and the Effects of Ionizing Radiation. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 1994, 65, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez, B.; Melero, A.; Montoro, A.; San Onofre, N.; Soriano, J.M. Molecular Insights into Radiation Effects and Protective Mechanisms: A Focus on Cellular Damage and Radioprotectors. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 12718–12732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Liang, Z.; Ma, S.; Li, L.; Liu, X. Radioprotective countermeasures for radiation injury (Review). Mol. Med. Rep. 2023, 27, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Dong, Y.; Wu, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, J.; Lu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Fan, S.; Li, D.; et al. Sitagliptin Mitigates Total Body Irradiation-Induced Hematopoietic Injury in Mice. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 8308616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, L.J. Sitagliptin: A Review in Type 2 Diabetes. Drugs 2017, 77, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broxmeyer, H.E.; Hoggatt, J.; O’Leary, H.A.; Mantel, C.; Chitteti, B.R.; Cooper, S.; Messina-Graham, S.; Hangoc, G.; Farag, S.; Rohrabaugh, S.L.; et al. Dipeptidylpeptidase 4 negatively regulates colony-stimulating factor activity and stress hematopoiesis. Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 1786–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Huang, Y.; Lin, W.; Wang, L.; Yang, Y.; Li, P.; Xiao, L.; Chen, Y.; Chu, Q.; Yuan, X. Sitagliptin Alleviates Radiation-Induced Intestinal Injury by Activating NRF2-Antioxidant Axis, Mitigating NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation, and Reversing Gut Microbiota Disorder. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 2586305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, X.; Ke, B.; Wang, X.; Wu, S.; Yang, R.; Hu, C. Additive effects of atorvastatin combined with sitagliptin on rats with myocardial infarction: A pilot study. Arch. Med. Sci. 2017, 13, 956–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihara, M.; Uchiyama, M. Determination of malonaldehyde precursor in tissues by thiobarbituric acid test. Anal. Biochem. 1978, 86, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellman, G.L. Tissue sulfhydryl groups. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1959, 82, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Oberley, L.W.; Li, Y. A simple method for clinical assay of superoxide dismutase. Clin. Chem. 1988, 34, 497–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aebi, H. Catalase estimation. In Methods of Enzymatic Analysis; Bergmeyer, H.U., Ed.; Verlag Chemie: New York, NY, USA, 1974; pp. 673–684. [Google Scholar]

- Lück, H. Catalase. In Methods of Enzymatic Analysis; Bergmeyer, H.U., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1965; pp. 885–894. [Google Scholar]

- Paglia, D.E.; Valentine, W.N. Studies on the quantitative and qualitative characterization of erythrocyte glutathione peroxidase. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1967, 70, 158–169. [Google Scholar]

- Johnsen, S.G. Testicular Biopsy Score Count—A Method for Registration of Spermatogenesis in Human Testes: Normal Values and Results in 335 Hypogonadal Males. Hormones 1970, 1, 2–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalçın, T.; Kaya, S.; Kaya Tektemur, N.; Ozan, İ.E. The Methods Used in Histopathological Evaluation of Testis Tissues. Batman Univ. J. Life Sci. 2020, 10, 148–157. [Google Scholar]

- Ekici, K.; Temelli, O.; Parlakpinar, H.; Samdanci, E.; Polat, A.; Beytur, A.; Tanbek, K.; Ekici, C.; Dursun, I.H. Beneficial effects of aminoguanidine on radiotherapy-induced kidney and testis injury. Andrologia 2016, 48, 683–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawlik, T.M.; Keyomarsi, K. Role of cell cycle in mediating sensitivity to radiotherapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2004, 59, 928–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgakopoulos, I.; Kouloulias, V.; Ntoumas, G.-N.; Desse, D.; Koukourakis, I.; Kougioumtzopoulou, A.; Kanakis, G.; Zygogianni, A. Radiotherapy and Testicular Function: A Comprehensive Review of the Radiation-Induced Effects with an Emphasis on Spermatogenesis. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitz, D.R.; Azzam, E.I.; Li, J.J.; Gius, D. Metabolic oxidation/reduction reactions and cellular responses to ionizing radiation: A unifying concept in stress response biology. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2004, 23, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Cao, F.; Liu, H. Radiation-induced Cell Death and Its Mechanisms. Health Phys. 2022, 123, 376–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.M.; Sloane, V.M.; Wu, H.; Luo, L.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, M.V.; Gewirtz, A.T.; Neish, A.S. Flagellin administration protects gut mucosal tissue from irradiation-induced apoptosis via MKP-7 activity. Gut 2011, 60, 648–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernet, M.; Mégnin-Chanet, F.; Hall, J.; Favaudon, V. Control of the G2/M checkpoints after exposure to low doses of ionising radiation: Implications for hyper-radiosensitivity. DNA Repair 2010, 9, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praveen, K.; Saxena, N. Crosstalk between Fas and JNK determines lymphocyte apoptosis after ionizing radiation. Radiat. Res. 2013, 179, 725–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, J.; Born, D.; Chamberlain, M.C. Radiation Necrosis: Relevance with Respect to Treatment of Primary and Secondary Brain Tumors. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2012, 12, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaurasia, M.; Bhatt, A.N.; Das, A.; Dwarakanath, B.S.; Sharma, K. Radiation-induced autophagy: Mechanisms and consequences. Free. Radic. Res. 2016, 50, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hippenstiel, S.; Krüll, M.; Ikemann, A.; Risau, W.; Clauss, M.; Suttorp, N. VEGF induces hyperpermeability by a direct action on endothelial cells. Am. J. Physiol.-Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 1998, 274, L678–L684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanthou, C.; Tozer, G. Targeting the vasculature of tumours: Combining VEGF pathway inhibitors with radiotherapy. Br. J. Radiol. 2019, 92, 20180405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.J.; Li, B.; Winer, J.; Armanini, M.; Gillett, N.; Phillips, H.S.; Ferrara, N. Inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor-induced angiogenesis suppresses tumour growth in vivo. Nature 1993, 362, 841–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farooq, M.; Khan, A.W.; Kim, M.S.; Choi, S. The Role of Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF) Signaling in Tissue Repair and Regeneration. Cells 2021, 10, 3242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrijvers, B.F.; Flyvbjerg, A.; De Vriese, A.S. The role of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in renal pathophysiology. Kidney Int. 2004, 65, 2003–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floege, J.; Hudkins, K.L.; Eitner, F.; Cui, Y.; Morrison, R.S.; Schelling, M.A.; Alpers, C.E. Localization of fibroblast growth factor-2 (basic FGF) and FGF receptor-1 in adult human kidney. Kidney Int. 1999, 56, 883–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaca, Z.M.; Ozen, H.; Akgöz, M.; Cigremis, Y. Effect of Caffeic Acid Phenethyl Ester (CAPE) on Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A (VEGF-A) Gene Expression in Gentamicin-induced Acute Renal Nephrotoxicity. Med. Sci. Int. Med. J. 2018, 7, 805–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaus, R.; Niyazi, M.; Lange-Sperandio, B. Radiation-induced kidney toxicity: Molecular and cellular pathogenesis. Radiat. Oncol. 2021, 16, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felice, F.D.; Marchetti, C.; Marampon, F.; Cascialli, G.; Muzii, L.; Tombolini, V. Radiation effects on male fertility. Andrology 2019, 7, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadloo, N.; Bidouei, F.; Mosleh-Shirazi, M.A.; Omrani, G.H.; Omidvari, S.; Mosalaei, A.; Mohammadianpanah, M. Impact of scattered radiation on testosterone deficiency and male hypogonadism in rectal cancer treated with external beam pelvic irradiation. Middle East J. Cancer 2010, 1, 115–122. [Google Scholar]

- Bruheim, K.; Svartberg, J.; Carlsen, E.; Dueland, S.; Haug, E.; Skovlund, E.; Guren, M.G. Radiotherapy for rectal cancer is associated with reduced serum testosterone and increased FSH and LH. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2008, 70, 722–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izard, M.A. Leydig cell function and radiation: A review of the literature. Radiother. Oncol. 1995, 34, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.A.; Kirkpatrick, D.R.; Smith, S.; Smith, T.K.; Pearson, T.; Kailasam, A.; Herrmann, K.Z.; Schubert, J.; Agrawal, D.K. Radioprotective agents to prevent cellular damage due to ionizing radiation. J. Transl. Med. 2017, 15, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pena, L.A.; Fuks, Z.; Kolesnick, R.N. Radiation-induced apoptosis of endothelial cells in the murine central nervous system: Protection by fibroblast growth factor and sphingomyelinase deficiency. Cancer Res. 2000, 60, 321–327. [Google Scholar]

- Kahne, T.; Lendeckel, U.; Wrenger, S.; Neubert, K.; Ansorge, S.; Reinhold, D. Dipeptidyl peptidase IV: A cell surface peptidase involved in regulating T cell growth (review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 1999, 4, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X. Biochemical properties of recombinant prolyl dipeptidases DPP-IV and DPP8. In Dipeptidyl Aminopeptidases (Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; Volume 575, pp. 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Mentlein, R. Dipeptidyl-peptidase IV (CD26)--role in the inactivation of regulatory peptides. Regul. Pept. 1999, 85, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; Xu, Q.; Yu, X.; Pan, R.; Chen, Y. Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors and their potential immune modulatory functions. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 209, 107503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Khafaji, A.M.; Bairam, A.F.; Abbas, S.F. Exploring the Anticancer and Antioxidant Potential Effects of Sitagliptin: An In Vitro Study on Lung Cancer Cell Lines. Al-Kufa J. Biol. 2024, 16, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makdissi, A.; Ghanim, H.; Vora, M.; Green, K.; Abuaysheh, S.; Chaudhuri, A.; Dhindsa, S.; Dandona, P. Sitagliptin exerts an antiinflammatory action. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 97, 3333–3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suda, M.; Shimizu, I.; Yoshida, Y.; Hayashi, Y.; Ikegami, R.; Katsuumi, G. Inhibition of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 ameliorates cardiac ischemia and systolic dysfunction by up-regulating the FGF-2/EGR-1 pathway. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, X.H.; Zheng, X.M.; Yu, L.X.; He, J.; Zhu, H.M.; Ge, X.P.; Ren, X.L.; Ye, F.Q.; Bellusci, S.; Xiao, J.; et al. Fibroblast growth factor 2 protects against renal ischaemia/reperfusion injury by attenuating mitochondrial damage and proinflammatory signalling. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2017, 21, 2909–2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Ma, Z.; Li, S.; Wen, L.; Huo, Y.; Wu, G.; Manicassamy, S.; Dong, Z. Fibroblast Growth Factor 2 Is Produced By Renal Tubular Cells to Act as a Paracrine Factor in Maladaptive Kidney Repair After Cisplatin Nephrotoxicity. Lab. Investig. 2023, 103, 100009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H.; Berndt, C.; Jones, D.P. Oxidative Stress. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2017, 86, 715–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, V.; Srivastava, R. 2.45 GHz microwave radiation induced oxidative stress: Role of inflammatory cytokines in regulating male fertility through estrogen receptor alpha in Gallus domesticus. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2022, 629, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.; Qin, D.; Zhao, C. Redox homeostasis maintained by GPX4 facilitates STING activation. Nat. Immunol. 2020, 21, 727–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Circu, M.L.; Aw, T.Y. Reactive oxygen species, cellular redox systems, and apoptosis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010, 48, 749–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsikas, D. Assessment of lipid peroxidation by measuring malondialdehyde (MDA) and relatives in biological samples: Analytical and biological challenges. Anal. Biochem. 2017, 524, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W.J.; Petell, J.K.; Swank, D.; Sanford, J.; Hixson, D.C.; Doyle, D. Expression of dipeptidyl peptidase IV in rat tissues is mainly regulated at the mRNA levels. Exp. Cell. Res. 1989, 182, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameters | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groups | MDA (nmol/gwt) (Mean ± SD) | GSH (µmol/gwt) (Mean ± SD) | SOD (U/mg Protein) (Mean ± SD) | CAT (K/g Protein) (Mean ± SD) | GPx (U/mg Protein) (Mean ± SD) | TAS (mmol Trolox Equiv./L) | TOS (µmol H2O2 Equiv./L) (Mean ± SD) | OSI (AU: Arbitrary Unit) (Mean ± SD) |

| C | 26.53 ± 2.9 | 18.55 ± 1.5 | 5.98 ± 1.5 | 154.72 ± 22.0 | 1.14 ± 0.3 | 2.95 (2.8–3.1) | 9.69 ± 1.0 | 3.29 ± 0.4 |

| RT | 50.56 ± 15.1 | 10.90 ± 2.3 | 3.19 ± 0.3 | 70.80 ± 29.2 | 0.48 ± 0.2 | 1.79 (1.2–2.2) | 14.96 ± 2.2 | 8.80 ± 2.7 |

| RT + SGT | 33.99 ± 10.5 | 14.28 ± 2.7 | 4.21 ± 0.5 | 108.75 ± 25.5 | 0.75 ± 0.2 | 2.72 (1.8–2.9) | 11.39 ± 2.2 | 4.35 ± 0.7 |

| SGT + RT | 40.72 ± 7.3 | 15.57 ± 2.2 | 3.92 ± 0.9 | 93.97 ± 30.8 | 0.75 ± 0.2 | 2.42 (2.2–2.8) | 9.70 ± 1.6 | 4.00 ± 0.7 |

| Statistical Comparisons (p value) | ||||||||

| C vs. RT | 0.015 * | 0 * | 0.007 * | 0 * | 0 * | 0.001 * | 0 * | 0.004 * |

| C vs. RT + SGT | 0.430 | 0.004 * | 0.079 | 0.01 * | 0.005 * | 0.005 * | 0.271 | 0.012 * |

| C vs. SGT + RT | 0.004 * | 0.057 | 0.043 * | 0.001 * | 0.005 * | 0.001 * | 1 | 0.155 |

| RT vs. RT + SGT | 0.141 | 0.025 * | 0.002 * | 0.042 * | 0.083 | 0.003 * | 0.003 * | 0.013 * |

| RT vs. SGT + RT | 0.560 | 0.001 * | 0.335 | 0.336 | 0.079 | 0.002 * | 0 * | 0.008 * |

| RT + SGT vs. SGT + RT | 0.654 | 0.658 | 0.968 | 0.697 | 1 | 0.103 | 0.276 | 0.906 |

| Parameters | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groups | MDA (nmol/gwt) (Median (Min–Max)) | GSH (µmol/gwt) (Mean ± SD) | SOD (U/mg Protein) (Mean ± SD) | CAT (K/g Protein) (Mean ± SD) | GPx (U/mg Protein) (Mean ± SD) | TAS (mmol Trolox Equiv./L) (Median (Min–Max)) | TOS (µmol H2O2 Equiv./L) (Mean ± SD) | OSI (AU: Arbitrary Unit) (Mean ± SD) |

| C | 18.25 (15.6–21.8) | 16.35 ± 2.4 | 7.29 ± 1.9 | 175.18 ± 24.4 | 0.61 ± 0.2 | 2.32 (2.1–2.7) | 9.90 ± 1.9 | 4.28 ± 1.0 |

| RT | 31.94 (22.1–34.7) | 13.90 ± 2.1 | 4.65 ± 0.5 | 93.04 ± 35.6 | 0.32 ± 0.1 | 2.29 (1.4–2.5) | 14.01 ± 1.4 | 6.67 ± 1.4 |

| RT + SGT | 18.86 (15.6–23.9) | 15.24 ± 2.5 | 5.88 ± 1.5 | 154.43 ± 45.9 | 0.45 ± 0.1 | 2.39 (1.6–2.6) | 10.93 ± 2.4 | 5.04 ± 1.5 |

| SGT + RT | 21.98 (18.0–23.2) | 14.23 ±1.4 | 6.69 ± 2.2 | 114.33 ± 28.4 | 0.51 ± 0.2 | 2.51 (1.3–2.8) | 12.12 ± 1.4 | 5.37 ± 1.7 |

| Statistical comparisons (p value) | ||||||||

| C vs. RT | 0.001 * | 0.124 | 0.031 * | 0 * | 0.01 * | 0.344 | 0.001 * | 0.012 * |

| C vs. RT + SGT | 0.529 | 0.727 | 0.529 | 0.631 | 0.283 | 1 | 0.668 | 0.717 |

| C vs. SGT + RT | 0.006 * | 0.219 | 0.993 | 0.008 * | 0.683 | 0.226 | 0.091 | 0.443 |

| RT vs. RT + SGT | 0.001 * | 0.601 | 0.262 | 0.007 * | 0.404 | 0.207 | 0.011 * | 0.128 |

| RT vs. SGT + RT | 0.002 * | 0.989 | 0.194 | 0.612 | 0.124 | 0.052 | 0.183 | 0.286 |

| RT + SGT vs. SGT + RT | 0.027 * | 0.784 | 0.957 | 0.117 | 0.893 | 0.207 | 0.568 | 0.968 |

| Parameters | Groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | RT | RT + SGT | SGT + RT | |

| Hemorrhage | 0 (0–0) | 1 (0–3) a | 0 (0–2) b | 0 (0–2) b |

| Cellular infiltration | 0 (0–0) | 1 (0–3) a | 0 (0–2) b | 0 (0–2) b |

| Glomerular collapse | 0 (0–0) | 1 (0–3) a | 0 (0–2) b | 0 (0–2) b |

| Tubular cellular degeneration | 0 (0–0) | 1 (0–2) a | 0 (0–2) b | 0 (0–2) b |

| Caspase-3 immunoreactivity | 0 (0–0) | 1 (0–2) a | 1 (0–2) a | 1 (0–2) a |

| VEGF immunoreactivity | 1 (0–2) | 0 (0–1) c | 1 (0–2) d | 1 (0–2) d |

| FGF immunoreactivity | 1 (0–2) | 0 (0–1) c | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) |

| Parameters | Groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | RT | RT + SGT | SGT + RT | |

| Johnsen score | 9 (8–10) | 7 (1–10) a | 8 (7–10) b | 8 (7–10) b |

| VEGF immunoreactivity | 1 (0–2) | 0 (0–1) c | 1 (0–2) d | 1 (0–2) d |

| FGF immunoreactivity | 1 (0–2) | 0 (0–1) c | 1 (0–2) d | 1 (0–2) d |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Celik, H.; Temelli, O.; Ozhan, O.; Taslidere, E.; Dogru, F. Sitagliptin Alleviates Radiation-Induced Kidney and Testis Degeneration in Rats. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1702. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121702

Celik H, Temelli O, Ozhan O, Taslidere E, Dogru F. Sitagliptin Alleviates Radiation-Induced Kidney and Testis Degeneration in Rats. Biomolecules. 2025; 15(12):1702. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121702

Chicago/Turabian StyleCelik, Huseyin, Oztun Temelli, Onural Ozhan, Elif Taslidere, and Feyzi Dogru. 2025. "Sitagliptin Alleviates Radiation-Induced Kidney and Testis Degeneration in Rats" Biomolecules 15, no. 12: 1702. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121702

APA StyleCelik, H., Temelli, O., Ozhan, O., Taslidere, E., & Dogru, F. (2025). Sitagliptin Alleviates Radiation-Induced Kidney and Testis Degeneration in Rats. Biomolecules, 15(12), 1702. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121702