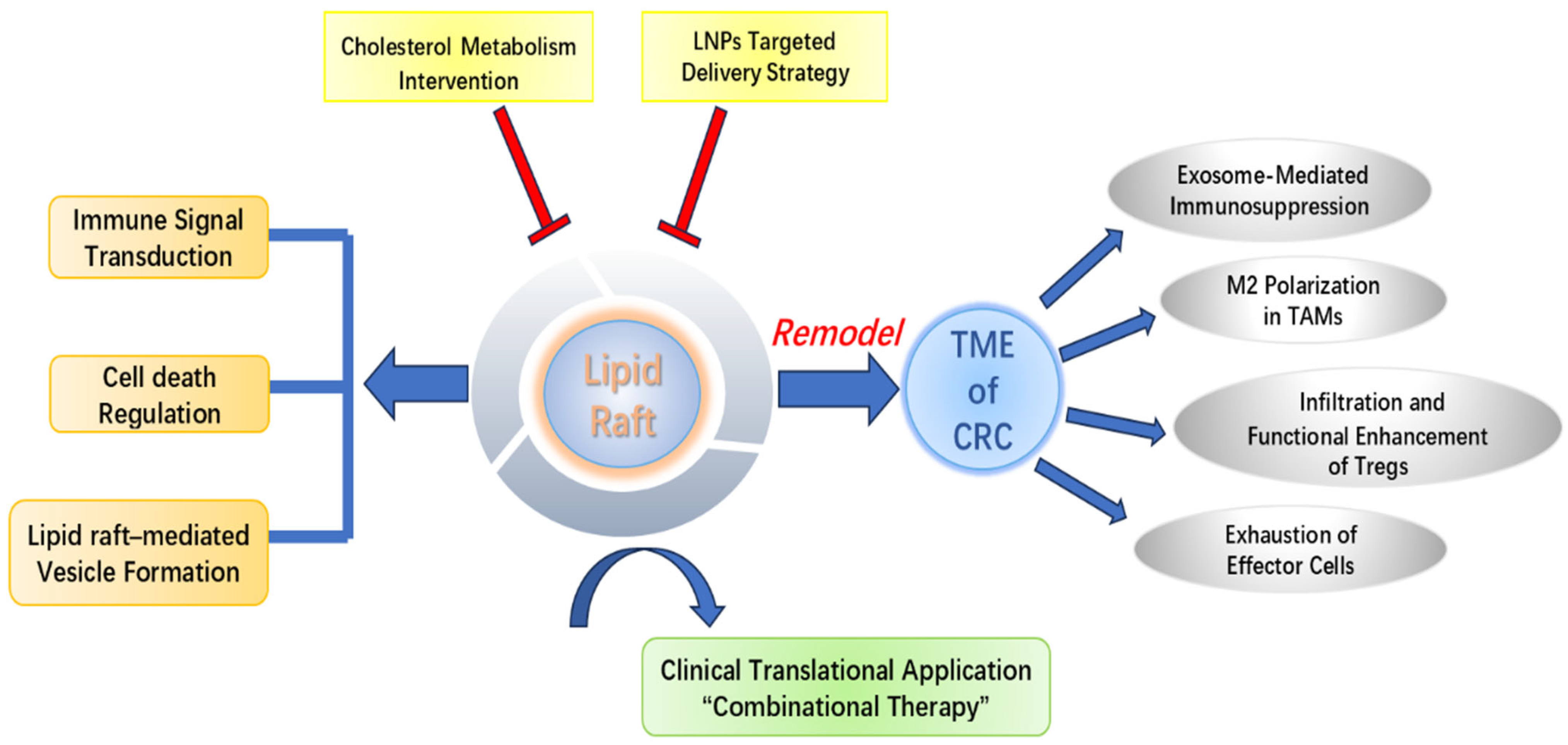

Regulatory Mechanisms of Lipid Rafts in Remodeling the Tumor Immune Microenvironment of Colorectal Cancer and Targeted Therapeutic Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Biological Basis of Lipid Rafts

2.1. Properties and Composition of Lipid Rafts

2.2. Types and Structural Proteins of Lipid Rafts

2.3. Physiological Functions of Lipid Rafts

2.4. Lipid Raft-Mediated Immune Signal Transduction

2.5. Lipid Raft-Mediated Cell Death

3. Immune Microenvironment Heterogeneity Between MSS and MSI-H Subtypes and Relevance to Lipid Rafts

4. Systemic Regulation of Immune Cell Function by Lipid Rafts

4.1. Exosome-Mediated Immunosuppression

4.2. Lipid Raft-Mediated Dysregulation of Immune Cell Function

4.2.1. Polarization of Tumor-Associated Macrophages

4.2.2. Infiltration and Functional Enhancement of Regulatory T Cells

4.2.3. Exhaustion of Effector Cells

5. Immunotherapeutic Strategies Targeting Lipid Rafts

5.1. Strategies Targeting Cholesterol Metabolism

5.2. Strategies for Targeted Delivery via Lipid Nanocarriers

5.3. Lipid Raft Heterogeneity and Immunotherapy Response

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABC | ATP-binding cassette |

| ABCA1 | ATP-binding cassette subfamily-A member 1 |

| APCs | antigen-presenting cells |

| CAFs | cancer-associated fibroblasts |

| CASMER | cluster of apoptotic signaling molecule-enriched raft |

| CAV-1 | caveolin-1 |

| CMS | consensus molecular subtype |

| CRC | colorectal cancer |

| CTL | cytotoxic T-lymphocyte |

| CTLA-4 | cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 |

| DCs | dendritic cells |

| DISC | death-inducing signaling complex |

| EGFR | epidermal growth factor receptor |

| EMT | epithelial–mesenchymal transition |

| ER | endoplasmic reticulum |

| GPI | glycosylphosphatidylinositol |

| HMG-CoA | 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA |

| ICI | immune checkpoint inhibition |

| LAG-3 | lymphocyte-activation gene 3 |

| Ld | liquid-disordered |

| LDL | low-density lipoprotein |

| LNPs | lipid nanoparticles |

| Lo | liquid-ordered |

| MDSCs | myeloid-derived suppressor cells |

| MHC-I | major histocompatibility complex class I |

| MSI-H | microsatellite instability-high |

| MSS | microsatellite stable |

| MβCD | methyl β-cyclodextrin |

| NK | natural killer |

| nSMase | neutral sphingomyelinase |

| PD-1 | programmed cell death protein |

| PD-L1 | programmed death-ligand 1 |

| PGE2 | prostaglandin E2 |

| SCFAs | short-chain fatty acids |

| TAMs | tumor-associated macrophages |

| TCRs | T-cell receptors |

| Tex | tumor-derived exosome |

| TGF-β | transforming growth factor-β |

| TILs | tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes |

| TIM-3 | T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-containing protein 3 |

| TIME | tumor immune microenvironment |

| TME | tumor microenvironment |

| Tregs | regulatory T cells |

| VEGF | vascular endothelial growth |

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Wagle, N.S.; Cercek, A.; Smith, R.A.; Jemal, A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2023. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 233–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yu, M.; Zhang, S. The characteristics of the tumor immune microenvironment in colorectal cancer with different MSI status and current therapeutic strategies. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1440830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorría, T.; Sierra-Boada, M.; Rojas, M.; Figueras, C.; Marin, S.; Madurga, S.; Cascante, M.; Maurel, J. Metabolic Singularities in Microsatellite-Stable Colorectal Cancer: Identifying Key Players in Immunosuppression to Improve the Immunotherapy Response. Cancers 2025, 17, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; He, J.; Lei, T.; Li, X.; Yue, S.; Liu, C.; Hu, Q. New insights into cancer immune checkpoints landscape from single-cell RNA sequencing. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2025, 1880, 189298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Ye, Z.; Xiong, J.; Lan, H.; Wang, F. Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes in Colorectal Cancer: The Fundamental Indication and Application on Immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 808964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, D.; Xin, X.; Xu, Y.; Xu, H.; Huang, L.; Xu, T. Improving the efficacy of immunotherapy for colorectal cancer: Targeting tumor microenvironment-associated immunosuppressive cells. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Deng, M.; Xue, D.; Guo, R.; Zhang, C.; Gao, J.; Li, H. PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors for early and middle stage microsatellite high-instability and stable colorectal cancer: A review. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2024, 39, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Qin, Y.; Yu, X.; Xu, X.; Yu, W. Lipid raft involvement in signal transduction in cancer cell survival, cell death and metastasis. Cell Prolif. 2022, 55, e13167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sezgin, E.; Levental, I.; Mayor, S.; Eggeling, C. The mystery of membrane organization: Composition, regulation and roles of lipid rafts. Nat. Reviews Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simons, K.; Toomre, D. Lipid rafts and signal transduction. Nat. Reviews Mol. Cell Biol. 2000, 1, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollinedo, F.; Gajate, C. Lipid rafts as signaling hubs in cancer cell survival/death and invasion: Implications in tumor progression and therapy: Thematic Review Series: Biology of Lipid Rafts. J. Lipid Res. 2020, 61, 611–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, L.J. Rafts defined: A report on the Keystone Symposium on Lipid Rafts and Cell Function. J. Lipid Res. 2006, 47, 1597–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruzzi, F.; Cappello, C.; Semprini, M.S.; Scalambra, L.; Angelicola, S.; Pittino, O.M.; Landuzzi, L.; Palladini, A.; Nanni, P.; Lollini, P.L. Lipid rafts, caveolae, and epidermal growth factor receptor family: Friends or foes? Cell Commun. Signal. CCS 2024, 22, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabi, I.R.; Le, P.U. Caveolae/raft-dependent endocytosis. J. Cell Biol. 2003, 161, 673–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhowmick, S.; Biswas, T.; Ahmed, M.; Roy, D.; Mondal, S. Caveolin-1 and lipids: Association and their dualism in oncogenic regulation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2023, 1878, 189002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, J.; Boscher, C.; Nabi, I.R. Caveolin-1, galectin-3 and lipid raft domains in cancer cell signalling. Essays Biochem. 2015, 57, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasubramanian, L.; Jyothi, H.; Goldbloom-Helzner, L.; Light, B.M.; Kumar, P.; Carney, R.P.; Farmer, D.L.; Wang, A. Development and Characterization of Bioinspired Lipid Raft Nanovesicles for Therapeutic Applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 54458–54477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollinedo, F.; Gajate, C. Lipid rafts as major platforms for signaling regulation in cancer. Adv. Biol. Regul. 2015, 57, 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, K.; Sampaio, J.L. Membrane organization and lipid rafts. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011, 3, a004697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadra, A.; Cinek, T.; Imboden, J.B. Translocation of CD28 to lipid rafts and costimulation of IL-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 11422–11427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipp, D.; Moemeni, B.; Ferzoco, A.; Kathirkamathamby, K.; Zhang, J.; Ballek, O.; Davidson, D.; Veillette, A.; Julius, M. Lck-dependent Fyn activation requires C terminus-dependent targeting of kinase-active Lck to lipid rafts. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 26409–26422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipp, D.; Leung, B.L.; Zhang, J.; Veillette, A.; Julius, M. Enrichment of lck in lipid rafts regulates colocalized fyn activation and the initiation of proximal signals through TCR alpha beta. J. Immunol. 2004, 172, 4266–4274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, H.Y.; Tao, X.; Chen, Z.; Levental, I.; Lin, X. Palmitoylation of PD-L1 Regulates Its Membrane Orientation and Immune Evasion. Langmuir ACS J. Surf. Colloids 2025, 41, 5170–5178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, H.; Lan, J.; Li, C.; Shi, H.; Brosseau, J.P.; Wang, H.; Lu, H.; Fang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, L.; et al. Inhibiting PD-L1 palmitoylation enhances T-cell immune responses against tumours. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 3, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajate, C.; Mollinedo, F. The antitumor ether lipid ET-18-OCH(3) induces apoptosis through translocation and capping of Fas/CD95 into membrane rafts in human leukemic cells. Blood 2001, 98, 3860–3863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajate, C.; Mollinedo, F. Lipid raft-mediated Fas/CD95 apoptotic signaling in leukemic cells and normal leukocytes and therapeutic implications. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2015, 98, 739–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffrès, P.A.; Gajate, C.; Bouchet, A.M.; Couthon-Gourvès, H.; Chantôme, A.; Potier-Cartereau, M.; Besson, P.; Bougnoux, P.; Mollinedo, F.; Vandier, C. Alkyl ether lipids, ion channels and lipid raft reorganization in cancer therapy. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016, 165, 114–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis-Sobreiro, M.; Gajate, C.; Mollinedo, F. Involvement of mitochondria and recruitment of Fas/CD95 signaling in lipid rafts in resveratrol-mediated antimyeloma and antileukemia actions. Oncogene 2009, 28, 3221–3234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizardo, D.Y.; Kuang, C.; Hao, S.; Yu, J.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, L. Immunotherapy efficacy on mismatch repair-deficient colorectal cancer: From bench to bedside. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2020, 1874, 188447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesh, K.; Stadler, Z.K.; Cercek, A.; Mendelsohn, R.B.; Shia, J.; Segal, N.H.; Diaz, L.A., Jr. Immunotherapy in colorectal cancer: Rationale, challenges and potential. Nat. Reviews Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakis, M.; Mu, X.J.; Shukla, S.A.; Qian, Z.R.; Cohen, O.; Nishihara, R.; Bahl, S.; Cao, Y.; Amin-Mansour, A.; Yamauchi, M.; et al. Genomic Correlates of Immune-Cell Infiltrates in Colorectal Carcinoma. Cell Rep. 2016, 15, 857–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, A.; Zhang, J.; Luo, P. Crosstalk Between the MSI Status and Tumor Microenvironment in Colorectal Cancer. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, K.; Mou, P.; Wang, Z.; Liu, S.; Liu, J.; Lu, H.; Yu, G. The next bastion to be conquered in immunotherapy: Microsatellite stable colorectal cancer. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1298524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirvent, A.; Bénistant, C.; Pannequin, J.; Veracini, L.; Simon, V.; Bourgaux, J.F.; Hollande, F.; Cruzalegui, F.; Roche, S. Src family tyrosine kinases-driven colon cancer cell invasion is induced by Csk membrane delocalization. Oncogene 2010, 29, 1303–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahn, K.A.; Su, Y.; Braet, F. Multifaceted nature of membrane microdomains in colorectal cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 17, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Li, T.; Wang, Q.; You, W.; Yang, H.; Xu, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, C.; Yang, L.; et al. Shaping immune landscape of colorectal cancer by cholesterol metabolites. EMBO Mol. Med. 2024, 16, 334–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, S.; Nagao, T.; Ingolfsson, H.I.; Maxfield, F.R.; Andersen, O.S.; Kopelovich, L.; Weinstein, I.B. The inhibitory effect of (-)-epigallocatechin gallate on activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor is associated with altered lipid order in HT29 colon cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 6493–6501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remacle-Bonnet, M.; Garrouste, F.; Baillat, G.; Andre, F.; Marvaldi, J.; Pommier, G. Membrane rafts segregate pro- from anti-apoptotic insulin-like growth factor-I receptor signaling in colon carcinoma cells stimulated by members of the tumor necrosis factor superfamily. Am. J. Pathol. 2005, 167, 761–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Liang, Y.; Xiang, C.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Qing, H.; Jiang, B.; et al. CD24 promoted cancer cell angiogenesis via Hsp90-mediated STAT3/VEGF signaling pathway in colorectal cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 55663–55676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Yao, H.; Li, C.; Fang, J.Y.; Xu, J. Regulation of PD-L1: Emerging Routes for Targeting Tumor Immune Evasion. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, H.; Hsu, J.M.; Yang, W.H.; Hung, M.C. Mechanisms regulating PD-L1 expression in cancers and associated opportunities for novel small-molecule therapeutics. Nat. Reviews Clin. Oncol. 2022, 19, 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, J.; Yu, D.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, H.; Xu, M.; Zhang, H.; Tian, S.; Zheng, G.; Lu, D.; et al. Benzosceptrin C induces lysosomal degradation of PD-L1 and promotes antitumor immunity by targeting DHHC3. Cell Reports Med. 2024, 5, 101357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Cao, Y.; Shen, L.; Xiao, T.; Cao, R.; Wei, S.; Tang, M.; Du, L.; Wu, H.; Wu, B.; et al. Regulation of PD-L1 through direct binding of cholesterol to CRAC motifs. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabq4722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, H.; Chen, S.; Liu, S.; Hu, Q.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, G.; Huang, K.; Li, R.; Fang, L. Overexpressing lipid raft protein STOML2 modulates the tumor microenvironment via NF-κB signaling in colorectal cancer. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. CMLS 2024, 81, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, S.S.; Yin, Y.; Lee, T.; Lai, R.C.; Yeo, R.W.; Zhang, B.; Choo, A.; Lim, S.K. Therapeutic MSC exosomes are derived from lipid raft microdomains in the plasma membrane. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2013, 2, 22614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouweneel, A.B.; Thomas, M.J.; Sorci-Thomas, M.G. The ins and outs of lipid rafts: Functions in intracellular cholesterol homeostasis, microparticles, and cell membranes: Thematic Review Series: Biology of Lipid Rafts. J. Lipid Res. 2020, 61, 676–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Théry, C.; Ostrowski, M.; Segura, E. Membrane vesicles as conveyors of immune responses. Nat. Reviews Immunol. 2009, 9, 581–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfers, J.; Lozier, A.; Raposo, G.; Regnault, A.; Théry, C.; Masurier, C.; Flament, C.; Pouzieux, S.; Faure, F.; Tursz, T.; et al. Tumor-derived exosomes are a source of shared tumor rejection antigens for CTL cross-priming. Nat. Med. 2001, 7, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Wei, D.; Wu, Z.; Zhou, X.; Wei, X.; Huang, H.; Li, G. Phase I clinical trial of autologous ascites-derived exosomes combined with GM-CSF for colorectal cancer. Mol. Ther. J. Am. Soc. Gene Ther. 2008, 16, 782–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Yu, S.; Zinn, K.; Wang, J.; Zhang, L.; Jia, Y.; Kappes, J.C.; Barnes, S.; Kimberly, R.P.; Grizzle, W.E.; et al. Murine mammary carcinoma exosomes promote tumor growth by suppression of NK cell function. J. Immunol. 2006, 176, 1375–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X.; Poliakov, A.; Liu, C.; Liu, Y.; Deng, Z.B.; Wang, J.; Cheng, Z.; Shah, S.V.; Wang, G.J.; Zhang, L.; et al. Induction of myeloid-derived suppressor cells by tumor exosomes. Int. J. Cancer 2009, 124, 2621–2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieckowski, E.U.; Visus, C.; Szajnik, M.; Szczepanski, M.J.; Storkus, W.J.; Whiteside, T.L. Tumor-derived microvesicles promote regulatory T cell expansion and induce apoptosis in tumor-reactive activated CD8+ T lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 2009, 183, 3720–3730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szajnik, M.; Czystowska, M.; Szczepanski, M.J.; Mandapathil, M.; Whiteside, T.L. Tumor-derived microvesicles induce, expand and up-regulate biological activities of human regulatory T cells (Treg). PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e11469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trajkovic, K.; Hsu, C.; Chiantia, S.; Rajendran, L.; Wenzel, D.; Wieland, F.; Schwille, P.; Brügger, B.; Simons, M. Ceramide triggers budding of exosome vesicles into multivesicular endosomes. Science 2008, 319, 1244–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulcahy, L.A.; Pink, R.C.; Carter, D.R. Routes and mechanisms of extracellular vesicle uptake. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2014, 3, 24641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Zhan, W.; Gao, Y.; Huang, L.; Gong, R.; Wang, W.; Zhang, R.; Wu, Y.; Gao, S.; Kang, T. RAB31 marks and controls an ESCRT-independent exosome pathway. Cell Res. 2021, 31, 157–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldman, R.J.; Maestre, N.; Aduib, O.M.; Medin, J.A.; Salvayre, R.; Levade, T. A neutral sphingomyelinase resides in sphingolipid-enriched microdomains and is inhibited by the caveolin-scaffolding domain: Potential implications in tumour necrosis factor signalling. Biochem. J. 2001, 355 Pt 3, 859–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Liu, B.; Cao, Y.; Yao, S.; Liu, Y.; Jin, G.; Qin, Y.; Chen, Y.; Cui, K.; Zhou, L.; et al. Colorectal Cancer-Derived Small Extracellular Vesicles Promote Tumor Immune Evasion by Upregulating PD-L1 Expression in Tumor-Associated Macrophages. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2102620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Wang, W.; Wang, S.; Yang, T.; Zhang, G.; Wang, D.; Ju, R.; Lu, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, L. Tumor microenvironment remodeling and tumor therapy based on M2-like tumor associated macrophage-targeting nano-complexes. Theranostics 2021, 11, 2892–2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, W.; Wang, J.; Hu, Y.; Yang, H.; Xie, Y.; Lv, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wu, D.; et al. CSF1R inhibition reprograms tumor-associated macrophages to potentiate anti-PD-1 therapy efficacy against colorectal cancer. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 202, 107126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goossens, P.; Rodriguez-Vita, J.; Etzerodt, A.; Masse, M.; Rastoin, O.; Gouirand, V.; Ulas, T.; Papantonopoulou, O.; Van Eck, M.; Auphan-Anezin, N.; et al. Membrane Cholesterol Efflux Drives Tumor-Associated Macrophage Reprogramming and Tumor Progression. Cell Metab. 2019, 29, 1376–1389.e1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, P.; Phillips, M.; Grieu, F.; Morris, M.; Zeps, N.; Joseph, D.; Platell, C.; Iacopetta, B. Tumor-infiltrating FOXP3+ T regulatory cells show strong prognostic significance in colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olguín, J.E.; Medina-Andrade, I.; Rodríguez, T.; Rodríguez-Sosa, M.; Terrazas, L.I. Relevance of Regulatory T Cells during Colorectal Cancer Development. Cancers 2020, 12, 1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toor, S.M.; Sasidharan Nair, V.; Decock, J.; Elkord, E. Immune checkpoints in the tumor microenvironment. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2020, 65, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aristin Revilla, S.; Kranenburg, O.; Coffer, P.J. Colorectal Cancer-Infiltrating Regulatory T Cells: Functional Heterogeneity, Metabolic Adaptation, and Therapeutic Targeting. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 903564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Liu, H.; He, P.; An, D.; Guo, X.; Zhang, X.; Feng, M. Inhibition of PCSK9 enhances the antitumor effect of PD-1 inhibitor in colorectal cancer by promoting the infiltration of CD8(+) T cells and the exclusion of Treg cells. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 947756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.T.; Lellouch, A.; Marguet, D. Lipid rafts and the initiation of T cell receptor signaling. Semin. Immunol. 2005, 17, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, S.; Guo, W.; Xu, Z.; He, Y.; Liang, C.; Mo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xiong, F.; Guo, C.; Li, Y.; et al. Natural killer group 2D receptor and its ligands in cancer immune escape. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, W.H.; Yang, Z.S.; Li, M.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, X.F.; Qin, Y.Y.; Song, J.Q.; Wang, B.B.; Yuan, B.; Cui, X.L.; et al. High Serum Levels of Cholesterol Increase Antitumor Functions of Nature Killer Cells and Reduce Growth of Liver Tumors in Mice. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 1713–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, P.; Wu, J.D. NKG2D and its ligands in cancer. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2018, 51, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucuk, B.; Yilmaz, E.; Cacan, E. Expression profiles of Natural Killer Group 2D Ligands (NGK2DLs) in colorectal carcinoma and changes in response to chemotherapeutic agents. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 3999–4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Lu, Y.; Sanchez, D.J.; Li, J.; Wang, L.; Meng, X.; Chen, J.; Kien, T.T.; Zhong, M.; et al. Region-Specific CD16(+) Neutrophils Promote Colorectal Cancer Progression by Inhibiting Natural Killer Cells. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, e2403414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, X.; Liu, R.; Meng, Y.; Xing, D.; Xu, D.; Lu, Z. Lipid metabolism and cancer. J. Exp. Med. 2021, 218, e20201606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseini, F.S.; Ahmadi, A.; Kesharwani, P.; Hosseini, H.; Sahebkar, A. Regulatory effects of statins on Akt signaling for prevention of cancers. Cell. Signal. 2024, 120, 111213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Bi, E.; Lu, Y.; Su, P.; Huang, C.; Liu, L.; Wang, Q.; Yang, M.; Kalady, M.F.; Qian, J.; et al. Cholesterol Induces CD8(+) T Cell Exhaustion in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cell Metab. 2019, 30, 143–156.e145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Zhao, Z.; Li, B.; Huan, S.; Li, Z.; Xie, J.; Liu, G. ACSL4-mediated lipid rafts prevent membrane rupture and inhibit immunogenic cell death in melanoma. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, L.P.; Ramos-Ruiz, R.; Herranz, J.; Martín-Hernández, R.; Vargas, T.; Mendiola, M.; Guerra, L.; Reglero, G.; Feliu, J.; Ramírez de Molina, A. The transcriptional and mutational landscapes of lipid metabolism-related genes in colon cancer. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 5919–5930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-Portolés, C.; Feliu, J.; Reglero, G.; Ramírez de Molina, A. ABCA1 overexpression worsens colorectal cancer prognosis by facilitating tumour growth and caveolin-1-dependent invasiveness, and these effects can be ameliorated using the BET inhibitor apabetalone. Mol. Oncol. 2018, 12, 1735–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Pan, J.; Zhu, H.; Chen, Z.Y. Effect of Gut Microbiota on Blood Cholesterol: A Review on Mechanisms. Foods 2023, 12, 4308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nenkov, M.; Ma, Y.; Gaßler, N.; Chen, Y. Metabolic Reprogramming of Colorectal Cancer Cells and the Microenvironment: Implication for Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Kwon, J.; Shin, H.J.; Moon, S.M.; Kim, S.B.; Shin, U.S.; Han, Y.H.; Kim, Y. Butyrate enhances the efficacy of radiotherapy via FOXO3A in colorectal cancer patient-derived organoids. Int. J. Oncol. 2020, 57, 1307–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eygeris, Y.; Gupta, M.; Kim, J.; Sahay, G. Chemistry of Lipid Nanoparticles for RNA Delivery. Acc. Chem. Res. 2022, 55, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Ali, K.; Wang, J. Research Advances of Lipid Nanoparticles in the Treatment of Colorectal Cancer. Int. J. Nanomed. 2024, 19, 6693–6715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.Y.; Ruan, L.M.; Mao, W.W.; Wang, J.Q.; Shen, Y.Q.; Sui, M.H. Preparation of RGD-modified long circulating liposome loading matrine, and its in vitro anti-cancer effects. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2010, 7, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juang, V.; Chang, C.H.; Wang, C.S.; Wang, H.E.; Lo, Y.L. pH-Responsive PEG-Shedding and Targeting Peptide-Modified Nanoparticles for Dual-Delivery of Irinotecan and microRNA to Enhance Tumor-Specific Therapy. Small 2019, 15, e1903296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, T.E.; Liko, A.F.; Gustiananda, M.; Putra, A.B.N.; Juanssilfero, A.B.; Hartrianti, P. Thiolated pectin-chitosan composites: Potential mucoadhesive drug delivery system with selective cytotoxicity towards colorectal cancer. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 225, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Chen, L.; Pan, X.; Shen, Y.; Ye, M.; Wang, G.; Cui, C.; Zhou, Q.; Tseng, Y.; Gong, Z.; et al. Targeting tumor monocyte-intrinsic PD-L1 by rewiring STING signaling and enhancing STING agonist therapy. Cancer Cell 2025, 43, 503–518.e510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Zhang, X.; Li, R.; Li, Z.; Lu, A.; Yu, F.; Sun, L.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; He, H. Lipid core-shell nanoparticles co-deliver FOLFOX regimen and siPD-L1 for synergistic targeted cancer treatment. J. Control. Release Off. J. Control. Release Soc. 2024, 368, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinney, J.; Dienstmann, R.; Wang, X.; de Reyniès, A.; Schlicker, A.; Soneson, C.; Marisa, L.; Roepman, P.; Nyamundanda, G.; Angelino, P.; et al. The consensus molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 1350–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marisa, L.; Blum, Y.; Taieb, J.; Ayadi, M.; Pilati, C.; Le Malicot, K.; Lepage, C.; Salazar, R.; Aust, D.; Duval, A.; et al. Intratumor CMS Heterogeneity Impacts Patient Prognosis in Localized Colon Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 4768–4780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunne, P.D.; McArt, D.G.; Bradley, C.A.; O’Reilly, P.G.; Barrett, H.L.; Cummins, R.; O’Grady, T.; Arthur, K.; Loughrey, M.B.; Allen, W.L.; et al. Challenging the Cancer Molecular Stratification Dogma: Intratumoral Heterogeneity Undermines Consensus Molecular Subtypes and Potential Diagnostic Value in Colorectal Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 4095–4104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cheng, Z.; Gu, J.; Lu, Y.; Cai, M.; Zhang, T.; Wang, J. Regulatory Mechanisms of Lipid Rafts in Remodeling the Tumor Immune Microenvironment of Colorectal Cancer and Targeted Therapeutic Strategies. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1675. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121675

Cheng Z, Gu J, Lu Y, Cai M, Zhang T, Wang J. Regulatory Mechanisms of Lipid Rafts in Remodeling the Tumor Immune Microenvironment of Colorectal Cancer and Targeted Therapeutic Strategies. Biomolecules. 2025; 15(12):1675. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121675

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheng, Zhihong, Jian Gu, Yaoyao Lu, Mingdong Cai, Tao Zhang, and Jiliang Wang. 2025. "Regulatory Mechanisms of Lipid Rafts in Remodeling the Tumor Immune Microenvironment of Colorectal Cancer and Targeted Therapeutic Strategies" Biomolecules 15, no. 12: 1675. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121675

APA StyleCheng, Z., Gu, J., Lu, Y., Cai, M., Zhang, T., & Wang, J. (2025). Regulatory Mechanisms of Lipid Rafts in Remodeling the Tumor Immune Microenvironment of Colorectal Cancer and Targeted Therapeutic Strategies. Biomolecules, 15(12), 1675. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121675