Early Postnatally Induced Conditional Reelin Deficiency Causes Malformations of Hippocampal Neurons

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Genotyping of the Animals

2.3. Western Blot from Brain Tissue Two and Four Weeks Postnatally

2.4. Immunocytochemistry of Whole Brain Sections

2.5. Golgi Staining and Neurolucida Reconstructions

2.6. Statistics

3. Results

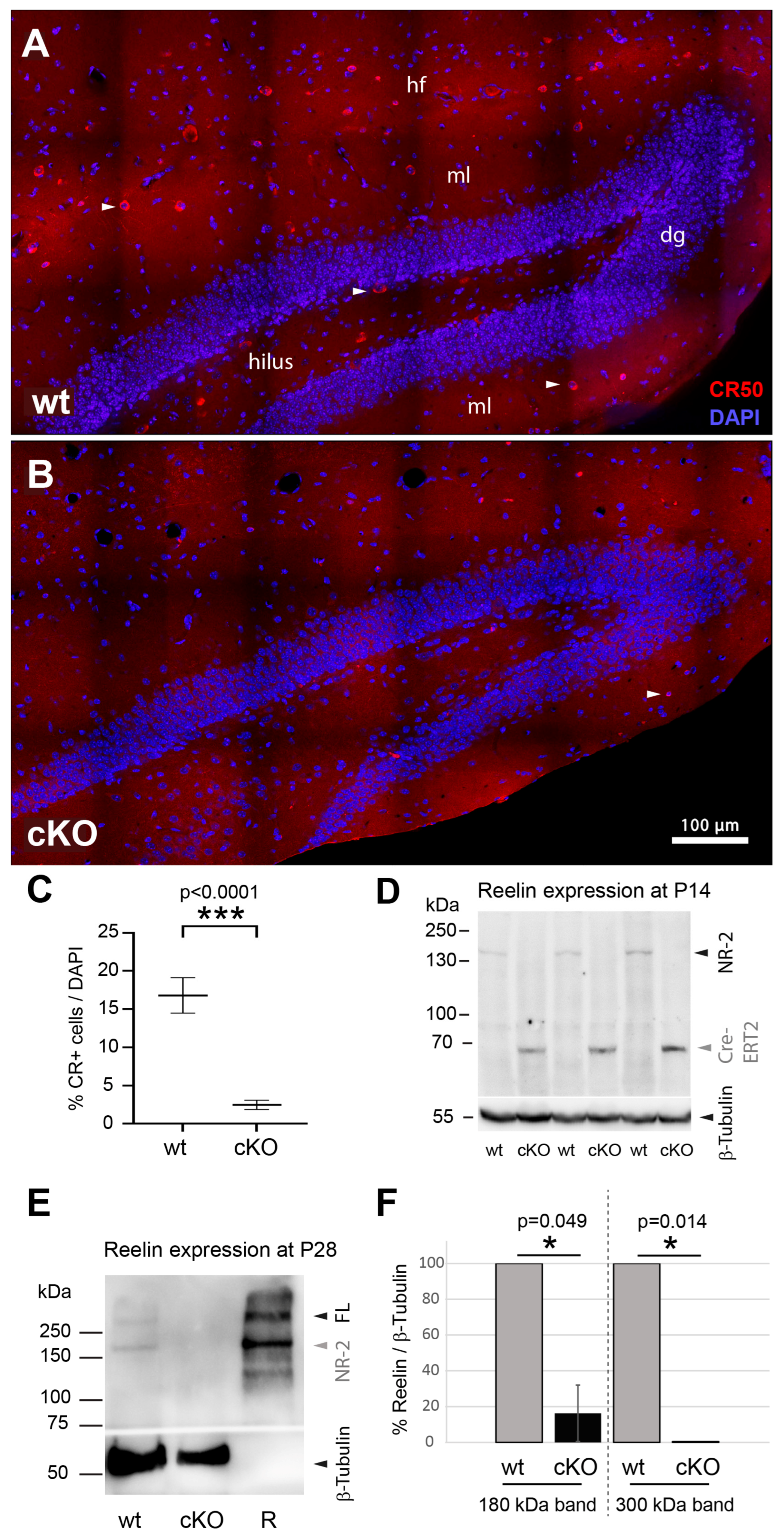

3.1. Assessment of Reelin Expression After Early Postnatal RelncKO

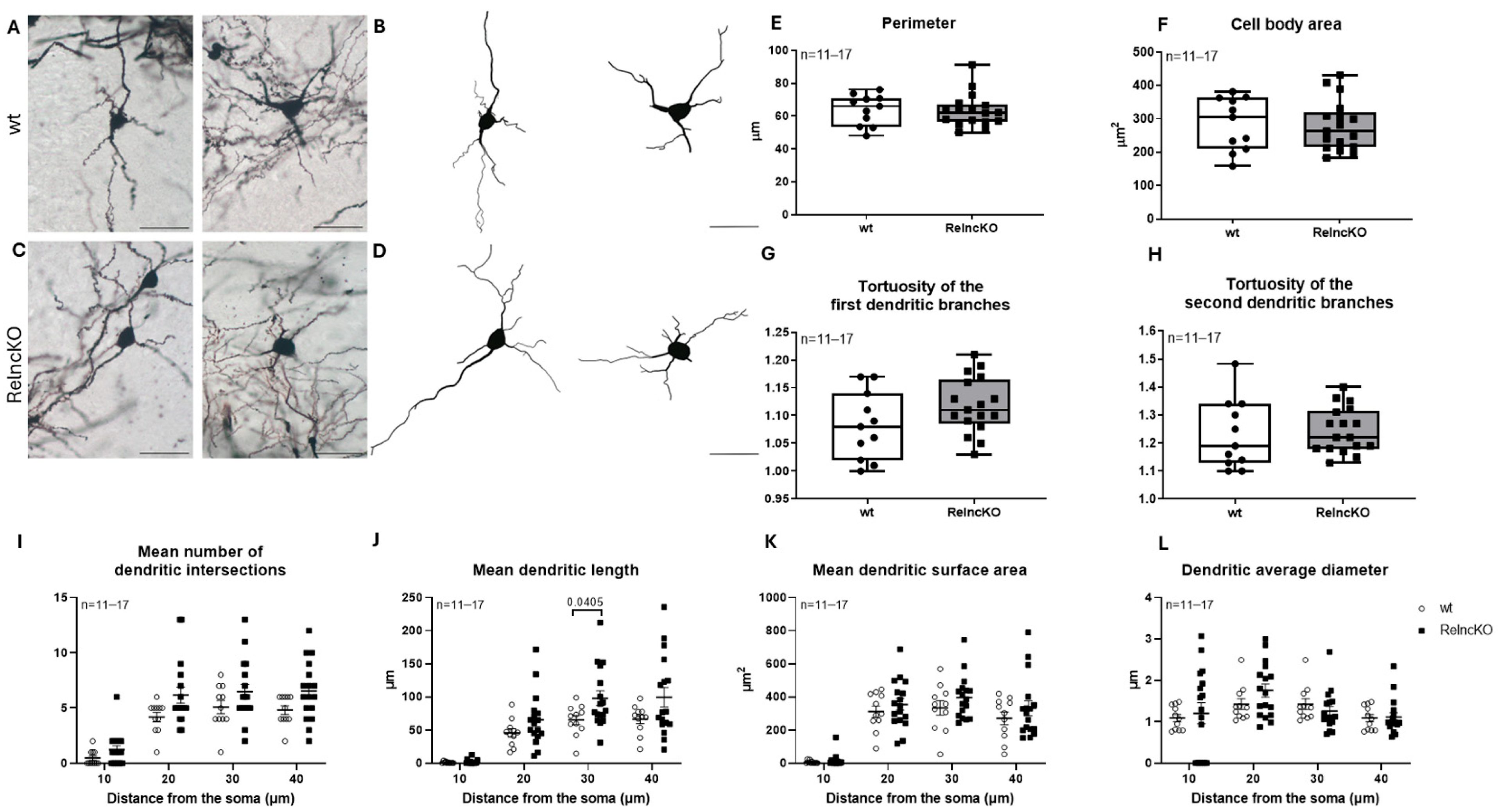

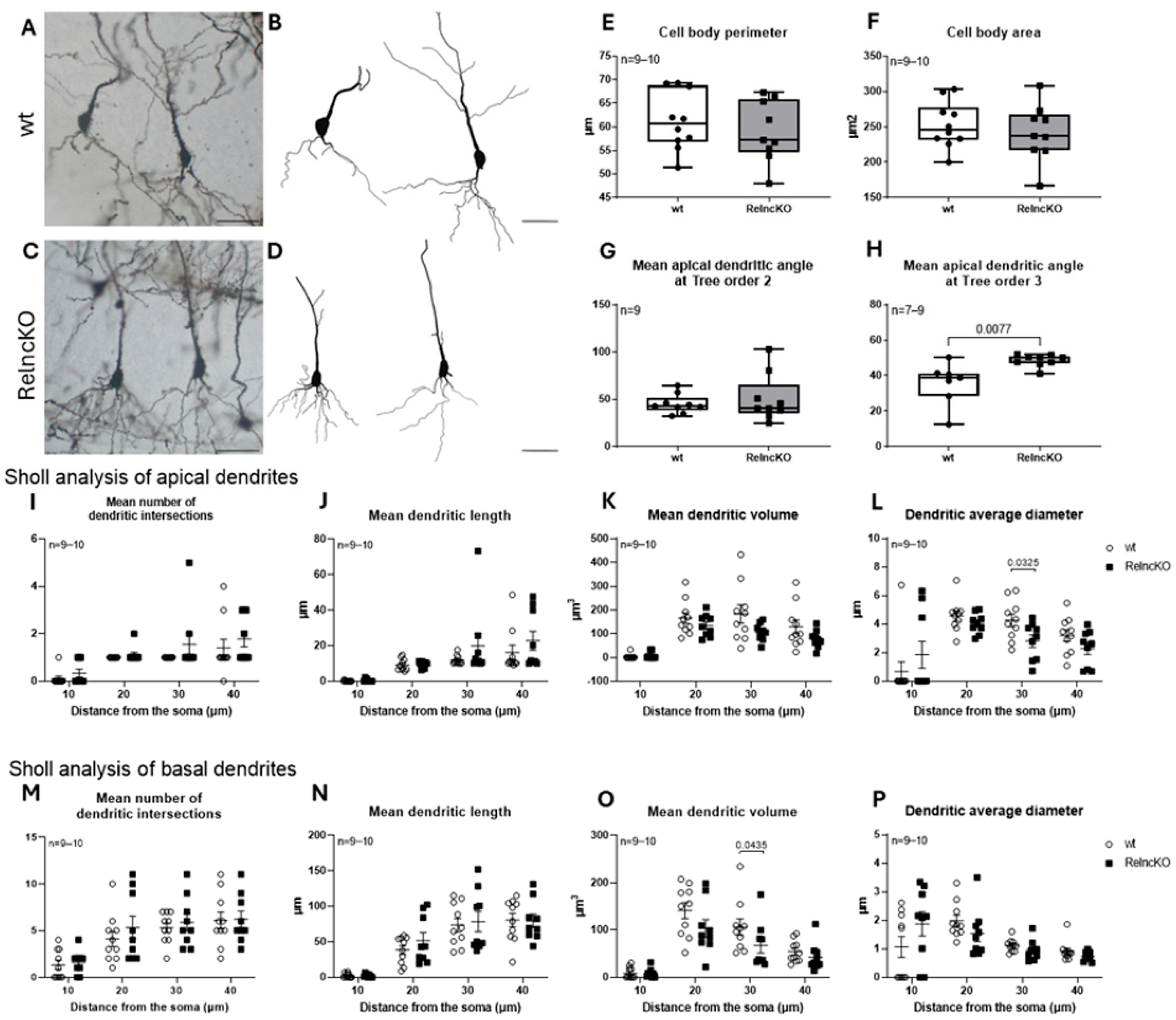

3.2. Multipolar Interneurons Develop Dendritic Hypertrophy After Early Postnatal RelncKO

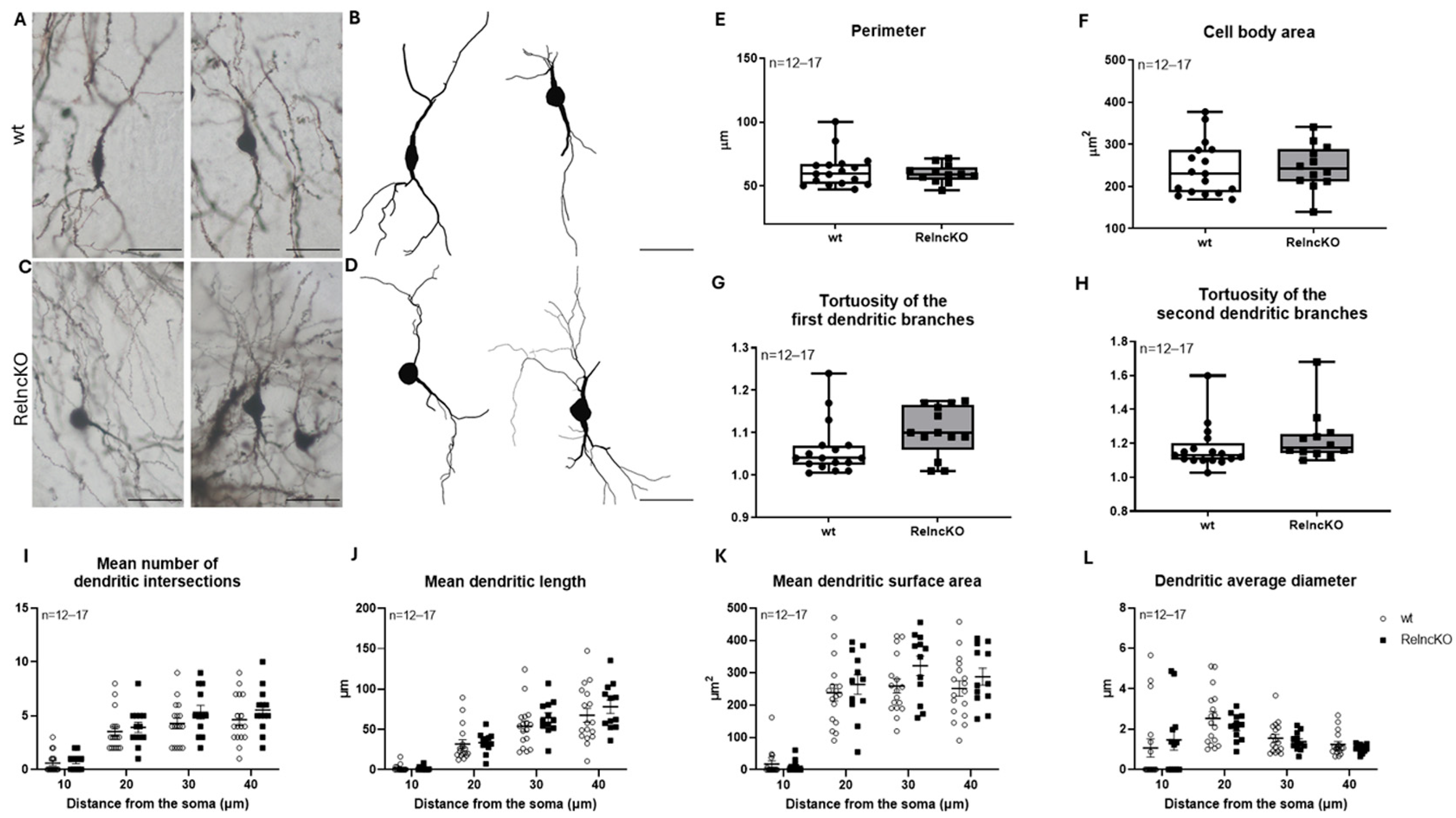

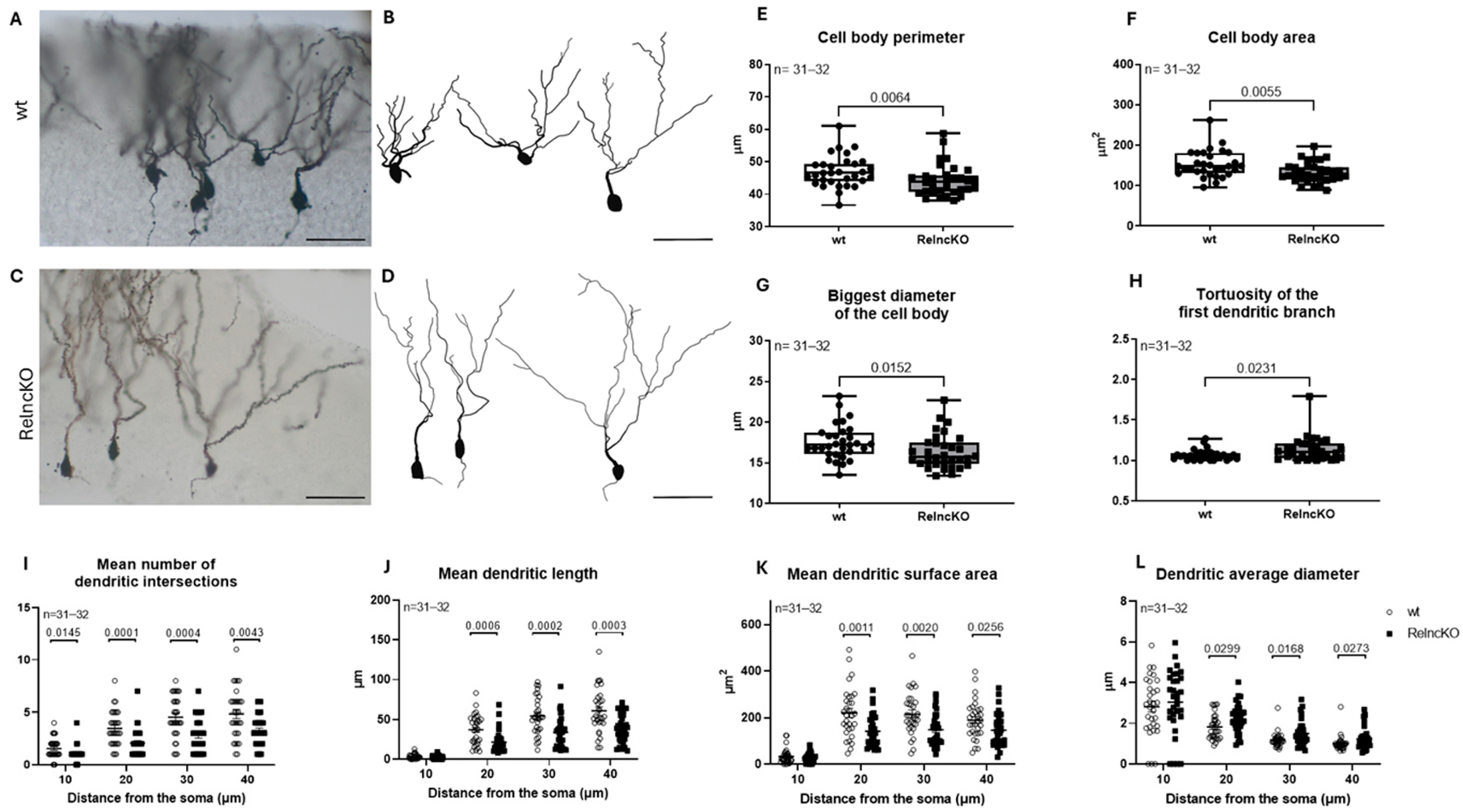

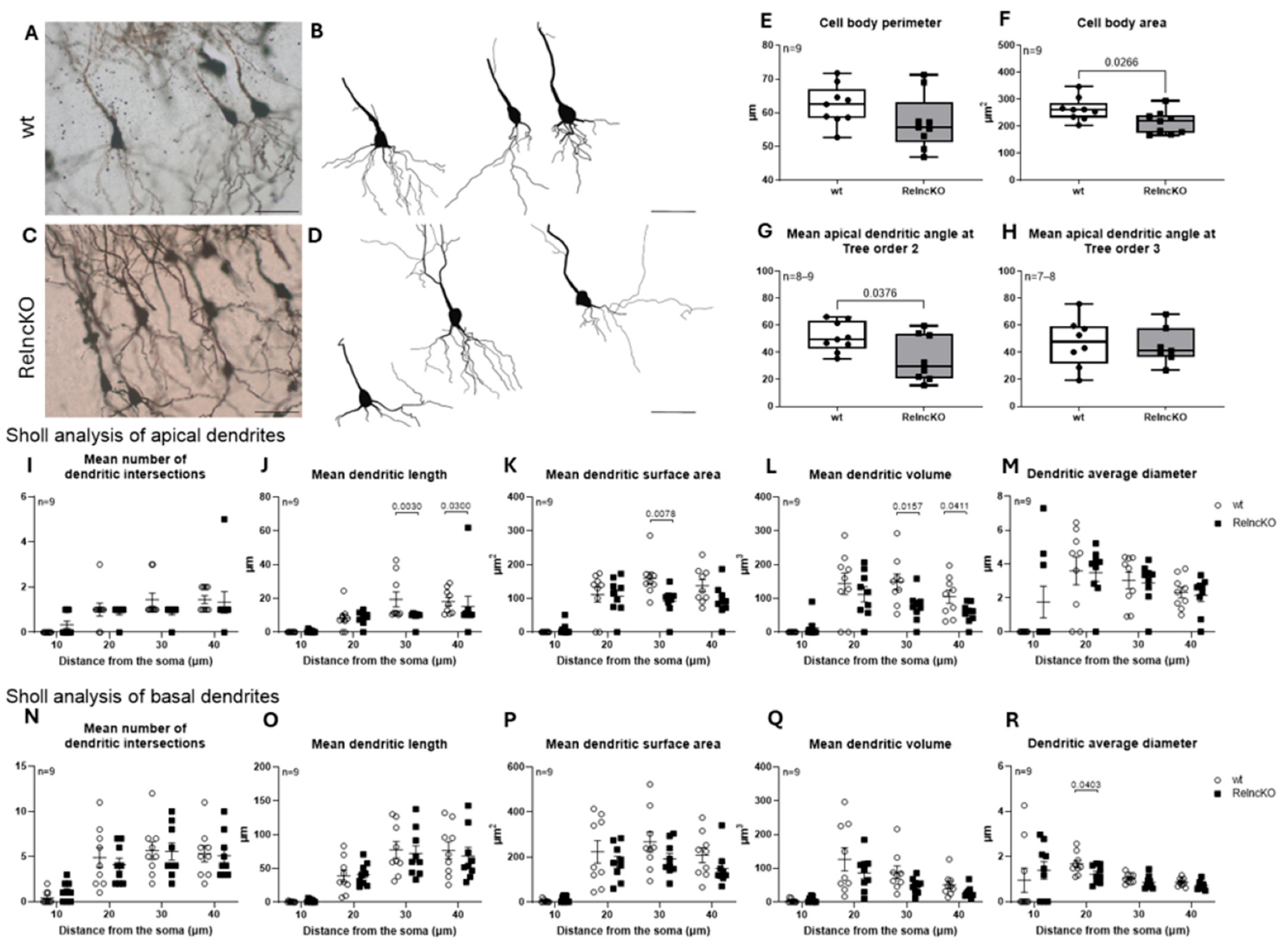

3.3. Dentate Granule Cells Develop Atrophic Proximal Dendritic Segments and Smaller Cell Bodies After Early Postnatal RelncKO

3.4. Dendritic Malformations of Hippocampal Pyramidal Cells After RelncKO Depend on the CA-Region

4. Discussion

4.1. Only Mild Malformations of Interneurons After Early Postnatal RelncKO

4.2. Of All Hippocampal Neuronal Cell Types, Dentate Granule Cells Display the Most Severe Malformations After Early Postnatal RelncKO

4.3. Malformations of Pyramidal Cells After Early Postnatal RelncKO Differ Between Subregions CA1, CA2, and CA3

4.4. Stage- and Cell Type-Specific Reelin Knock Out Strategies Reveal Different Reelin Functions

4.5. Reduced Reelin Expression and Neuropsychiatric Disorders

5. Conclusions

Methodological Considerations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Falconer, D.S. Two new mutants, ‘trembler’ and ‘reeler’, with neurological actions in the house mouse (Mus musculus L.). J. Genet. 1951, 50, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsuyama, Y.; Terashima, T. Developmental anatomy of reeler mutant mouse. Dev. Growth Differ. 2009, 51, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanfield, B.B.; Cowan, W.M. The development of the hippocampus and dentate gyrus in normal and reeler mice. J. Comp. Neurol. 1979, 185, 423–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goffinet, A.M. An early development defect in the cerebral cortex of the reeler mouse. A morphological study leading to a hypothesis concerning the action of the mutant gene. Anat. Embryol. 1979, 157, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Arcangelo, G.; Curran, T. Reeler: New tales on an old mutant mouse. Bioessays 1998, 20, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, A.; Pearlman, A.L. Abnormal reorganization of preplate neurons and their associated extracellular matrix: An early manifestation of altered neocortical development in the reeler mutant mouse. J. Comp. Neurol. 1997, 378, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, A.J.; Olson, E.C. Reelin promotes neuronal orientation and dendritogenesis during preplate splitting. Cereb. Cortex 2010, 20, 2213–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caviness, V.S., Jr. Neocortical histogenesis in normal and reeler mice: A developmental study based upon [3H]thymidine autoradiography. Brain Res. 1982, 256, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyata, T.; Nakajima, K.; Aruga, J.; Takahashi, S.; Ikenaka, K.; Mikoshiba, K.; Ogawa, M. Distribution of a reeler gene-related antigen in the developing cerebellum: An immunohistochemical study with an allogeneic antibody CR-50 on normal and reeler mice. J. Comp. Neurol. 1996, 372, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Arcangelo, G.; Miao, G.G.; Chen, S.C.; Soares, H.D.; Morgan, J.I.; Curran, T. A protein related to extracellular matrix proteins deleted in the mouse mutant reeler. Nature 1995, 374, 719–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin-Padilla, M. Dual origin of the mammalian neocortex and evolution of the cortical plate. Anat. Embryol. 1978, 152, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drakew, A.; Deller, T.; Heimrich, B.; Gebhardt, C.; Del Turco, D.; Tielsch, A.; Förster, E.; Herz, J.; Frotscher, M. Dentate granule cells in reeler mutants and VLDLR and ApoER2 knockout mice. Exp. Neurol. 2002, 176, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto Lord, M.C.; Caviness, V.S., Jr. Determinants of cell shape and orientation: A comparative Golgi analysis of cell-axon interrelationships in the developing neocortex of normal and reeler mice. J. Comp. Neurol. 1979, 187, 49–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, X.; Fan, L.; Shao, H.; Lu, X.; Zhang, W.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, S.; Frotscher, M.; Zhao, S. Reelin Induces Branching of Neurons and Radial Glial Cells during Corticogenesis. Cereb. Cortex 2015, 25, 3640–3653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meseke, M.; Cavus, E.; Förster, E. Reelin promotes microtubule dynamics in processes of developing neurons. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2013, 139, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S.; Renfro, A.; Quattrocchi, C.C.; Sheldon, M.; D’Arcangelo, G. Reelin promotes hippocampal dendrite development through the VLDLR/ApoER2-Dab1 pathway. Neuron 2004, 41, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deller, T.; Drakew, A.; Heimrich, B.; Förster, E.; Tielsch, A.; Frotscher, M. The hippocampus of the reeler mutant mouse: Fiber segregation in area CA1 depends on the position of the postsynaptic target cells. Exp. Neurol. 1999, 156, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilchez-Acosta, A.; Manso, Y.; Cardenas, A.; Elias-Tersa, A.; Martinez-Losa, M.; Pascual, M.; Alvarez-Dolado, M.; Nairn, A.C.; Borrell, V.; Soriano, E. Specific contribution of Reelin expressed by Cajal-Retzius cells or GABAergic interneurons to cortical lamination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2120079119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahle, J.; Muhia, M.; Wagener, R.J.; Tippmann, A.; Bock, H.H.; Graw, J.; Herz, J.; Staiger, J.F.; Drakew, A.; Kneussel, M.; et al. Selective Inactivation of Reelin in Inhibitory Interneurons Leads to Subtle Changes in the Dentate Gyrus But Leaves Cortical Layering and Behavior Unaffected. Cereb. Cortex 2020, 30, 1688–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujadas, L.; Gruart, A.; Bosch, C.; Delgado, L.; Teixeira, C.M.; Rossi, D.; de Lecea, L.; Martinez, A.; Delgado-Garcia, J.M.; Soriano, E. Reelin regulates postnatal neurogenesis and enhances spine hypertrophy and long-term potentiation. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 4636–4649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, C.M.; Kron, M.M.; Masachs, N.; Zhang, H.; Lagace, D.C.; Martinez, A.; Reillo, I.; Duan, X.; Bosch, C.; Pujadas, L.; et al. Cell-autonomous inactivation of the reelin pathway impairs adult neurogenesis in the hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 12051–12065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane-Donovan, C.; Philips, G.T.; Wasser, C.R.; Durakoglugil, M.S.; Masiulis, I.; Upadhaya, A.; Pohlkamp, T.; Coskun, C.; Kotti, T.; Steller, L.; et al. Reelin protects against amyloid beta toxicity in vivo. Sci. Signal 2015, 8, ra67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad, M.I.K.; Petrova, P.; Daoud, S.; Rabaya, O.; Jbara, A.; Melliti, N.; Leifeld, J.; Jakovcevski, I.; Reiss, G.; Herz, J.; et al. Reelin restricts dendritic growth of interneurons in the neocortex. Development 2021, 148, dev199718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, T.; D’Arcangelo, G. Role of reelin in the control of brain development. Brain Res. Rev. 1998, 26, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad, M.I.K.; Daoud, S.; Petrova, P.; Rabaya, O.; Jbara, A.; Al Houqani, S.; BaniYas, S.; Alblooshi, M.; Almheiri, A.; Nakhal, M.M.; et al. Reelin differentially shapes dendrite morphology of medial entorhinal cortical ocean and island cells. Development 2024, 151, dev202449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, S.; McMahon, A.P. Efficient recombination in diverse tissues by a tamoxifen-inducible form of Cre: A tool for temporally regulated gene activation/inactivation in the mouse. Dev. Biol. 2002, 244, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad, M.I.K.; Jbara, A.; Rabaya, O.; Petrova, P.; Daoud, S.; Melliti, N.; Meseke, M.; Lutz, D.; Petrasch-Parwez, E.; Schwitalla, J.C.; et al. Reelin signaling modulates GABA(B) receptor function in the neocortex. J. Neurochem. 2021, 156, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sholl, D.A. Dendritic organization in the neurons of the visual and motor cortices of the cat. J. Anat. 1953, 87, 387–406. [Google Scholar]

- Benavides-Piccione, R.; Regalado-Reyes, M.; Fernaud-Espinosa, I.; Kastanauskaite, A.; Tapia-González, S.; León-Espinosa, G.; Rojo, C.; Insausti, R.; Segev, I.; DeFelipe, J. Differential Structure of Hippocampal CA1 Pyramidal Neurons in the Human and Mouse. Cereb. Cortex 2019, 30, 730–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihaljević, B.; Larrañaga, P.; Benavides-Piccione, R.; DeFelipe, J.; Bielza, C. Comparing basal dendrite branches in human and mouse hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons with Bayesian networks. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karube, F.; Kubota, Y.; Kawaguchi, Y. Axon branching and synaptic bouton phenotypes in GABAergic nonpyramidal cell subtypes. J. Neurosci. 2004, 24, 2853–2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kepecs, A.; Fishell, G. Interneuron cell types are fit to function. Nature 2014, 505, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markram, H.; Toledo-Rodriguez, M.; Wang, Y.; Gupta, A.; Silberberg, G.; Wu, C. Interneurons of the neocortical inhibitory system. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2004, 5, 793–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, U.; Frotscher, M. Postnatal development of nonpyramidal neurons in the rat hippocampus (areas CA1 and CA3): A combined Golgi/electron microscope study. Anat. Embryol. 1990, 181, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.J. Activity-dependent development of inhibitory synapses and innervation pattern: Role of GABA signalling and beyond. J. Physiol. 2009, 587, 1881–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, T.F. Interneuron Diversity series: Rhythm and mood in perisomatic inhibition. Trends Neurosci. 2003, 26, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, S.B.; Sejnowski, T.J.; Behrens, M.M. Behavioral and neurochemical consequences of cortical oxidative stress on parvalbumin-interneuron maturation in rodent models of schizophrenia. Neuropharmacology 2012, 62, 1322–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesold, C.; Liu, W.S.; Guidotti, A.; Costa, E.; Caruncho, H.J. Cortical bitufted, horizontal, and Martinotti cells preferentially express and secrete reelin into perineuronal nets, nonsynaptically modulating gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 3217–3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, J.; Das, G.D. Autoradiographic and histological studies of postnatal neurogenesis. I. A longitudinal investigation of the kinetics, migration and transformation of cells incorporating tritiated thymidine in neonate rats, with special reference to postnatal neurogenesis in some brain regions. J. Comp. Neurol. 1966, 126, 337–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer, S.A. Development of the hippocampal region in the rat. I. Neurogenesis examined with 3H-thymidine autoradiography. J. Comp. Neurol. 1980, 190, 87–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angevine, J.B., Jr. Time of neuron origin in the hippocampal region. An autoradiographic study in the mouse. Exp. Neurol. Suppl. 1965, 11 (Suppl. S2), 1–70. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalieri, D.; Angelova, A.; Islah, A.; Lopez, C.; Bocchio, M.; Bollmann, Y.; Baude, A.; Cossart, R. CA1 pyramidal cell diversity is rooted in the time of neurogenesis. Elife 2021, 10, e69270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caviness, V.S., Jr.; Sidman, R.L. Time of origin or corresponding cell classes in the cerebral cortex of normal and reeler mutant mice: An autoradiographic analysis. J. Comp. Neurol. 1973, 148, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, K.H.; Johanssen, C.; Tielsch, A.; Herz, J.; Deller, T.; Frotscher, M.; Förster, E. Malformation of the radial glial scaffold in the dentate gyrus of reeler mice, scrambler mice, and ApoER2/VLDLR-deficient mice. J. Comp. Neurol. 2003, 460, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lossi, L.; Castagna, C.; Granato, A.; Merighi, A. The Reeler Mouse: A Translational Model of Human Neurological Conditions, or Simply a Good Tool for Better Understanding Neurodevelopment? J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Chai, X.; Frotscher, M. Balance between neurogenesis and gliogenesis in the adult hippocampus: Role for reelin. Dev. Neurosci. 2007, 29, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibbe, M.; Förster, E.; Basak, O.; Taylor, V.; Frotscher, M. Reelin and Notch1 cooperate in the development of the dentate gyrus. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 8578–8585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakahira, E.; Yuasa, S. Neuronal generation, migration, and differentiation in the mouse hippocampal primoridium as revealed by enhanced green fluorescent protein gene transfer by means of in utero electroporation. J. Comp. Neurol. 2005, 483, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatemi, S.H.; Earle, J.A.; McMenomy, T. Reduction in Reelin immunoreactivity in hippocampus of subjects with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depression. Mol. Psychiatry 2000, 5, 654–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatemi, S.H.; Snow, A.V.; Stary, J.M.; Araghi-Niknam, M.; Reutiman, T.J.; Lee, S.; Brooks, A.I.; Pearce, D.A. Reelin signaling is impaired in autism. Biol. Psychiatry 2005, 57, 777–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, J.T. Glutamate and schizophrenia: Beyond the dopamine hypothesis. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 2006, 26, 365–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuchillo-Ibanez, I.; Balmaceda, V.; Mata-Balaguer, T.; Lopez-Font, I.; Saez-Valero, J. Reelin in Alzheimer’s Disease, Increased Levels but Impaired Signaling: When More is Less. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2016, 52, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsuyama, Y.; Hattori, M. REELIN ameliorates Alzheimer’s disease, but how? Neurosci. Res. 2024, 208, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valderrama-Mantilla, A.I.; Martin-Cuevas, C.; Gomez-Garrido, A.; Morente-Montilla, C.; Crespo-Facorro, B.; Garcia-Cerro, S. Shared molecular signature in Alzheimer’s disease and schizophrenia: A systematic review of the reelin signaling pathway. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2025, 169, 106032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez-Valadez, B.; Rabano, A.; Llorens-Martin, M. Progression of Alzheimer’s disease parallels unusual structural plasticity of human dentate granule cells. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2022, 10, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopera, F.; Marino, C.; Chandrahas, A.S.; O’Hare, M.; Villalba-Moreno, N.D.; Aguillon, D.; Baena, A.; Sanchez, J.S.; Vila-Castelar, C.; Ramirez Gomez, L.; et al. Resilience to autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease in a Reelin-COLBOS heterozygous man. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 1243–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schneider-Lódi, M.; Ahrari, A.; Meseke, M.; Corvace, F.; Kümmel, M.-L.; Trampe, A.-K.; Hamad, M.I.K.; Förster, E. Early Postnatally Induced Conditional Reelin Deficiency Causes Malformations of Hippocampal Neurons. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1662. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121662

Schneider-Lódi M, Ahrari A, Meseke M, Corvace F, Kümmel M-L, Trampe A-K, Hamad MIK, Förster E. Early Postnatally Induced Conditional Reelin Deficiency Causes Malformations of Hippocampal Neurons. Biomolecules. 2025; 15(12):1662. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121662

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchneider-Lódi, Mária, Ala Ahrari, Maurice Meseke, Franco Corvace, Marie-Luise Kümmel, Anne-Kathrin Trampe, Mohammad I. K. Hamad, and Eckart Förster. 2025. "Early Postnatally Induced Conditional Reelin Deficiency Causes Malformations of Hippocampal Neurons" Biomolecules 15, no. 12: 1662. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121662

APA StyleSchneider-Lódi, M., Ahrari, A., Meseke, M., Corvace, F., Kümmel, M.-L., Trampe, A.-K., Hamad, M. I. K., & Förster, E. (2025). Early Postnatally Induced Conditional Reelin Deficiency Causes Malformations of Hippocampal Neurons. Biomolecules, 15(12), 1662. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121662