Sequence Determinants of G-Quadruplex Thermostability: Aligning Evidence from High-Precision Biophysics and High-Throughput Genomics

Abstract

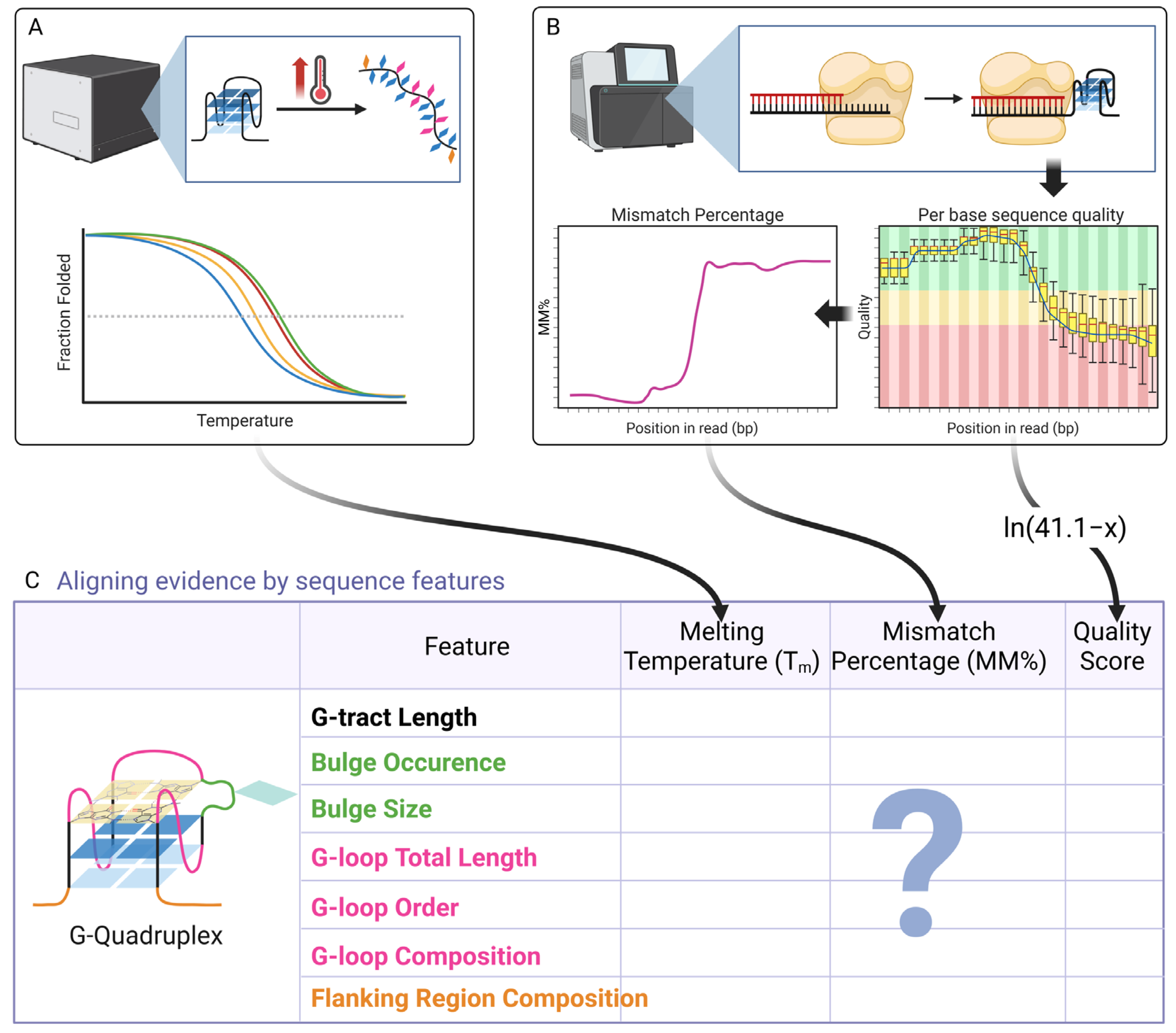

1. Introduction: The Challenge of Quantifying G-Quadruplex Stability Across Scales

1.1. The Biological Significance of G4 Stability: From Biophysical Property to Functional Determinant

1.2. The Methodological Divide in Stability Assessment

1.3. Focusing on Sequence Determinants

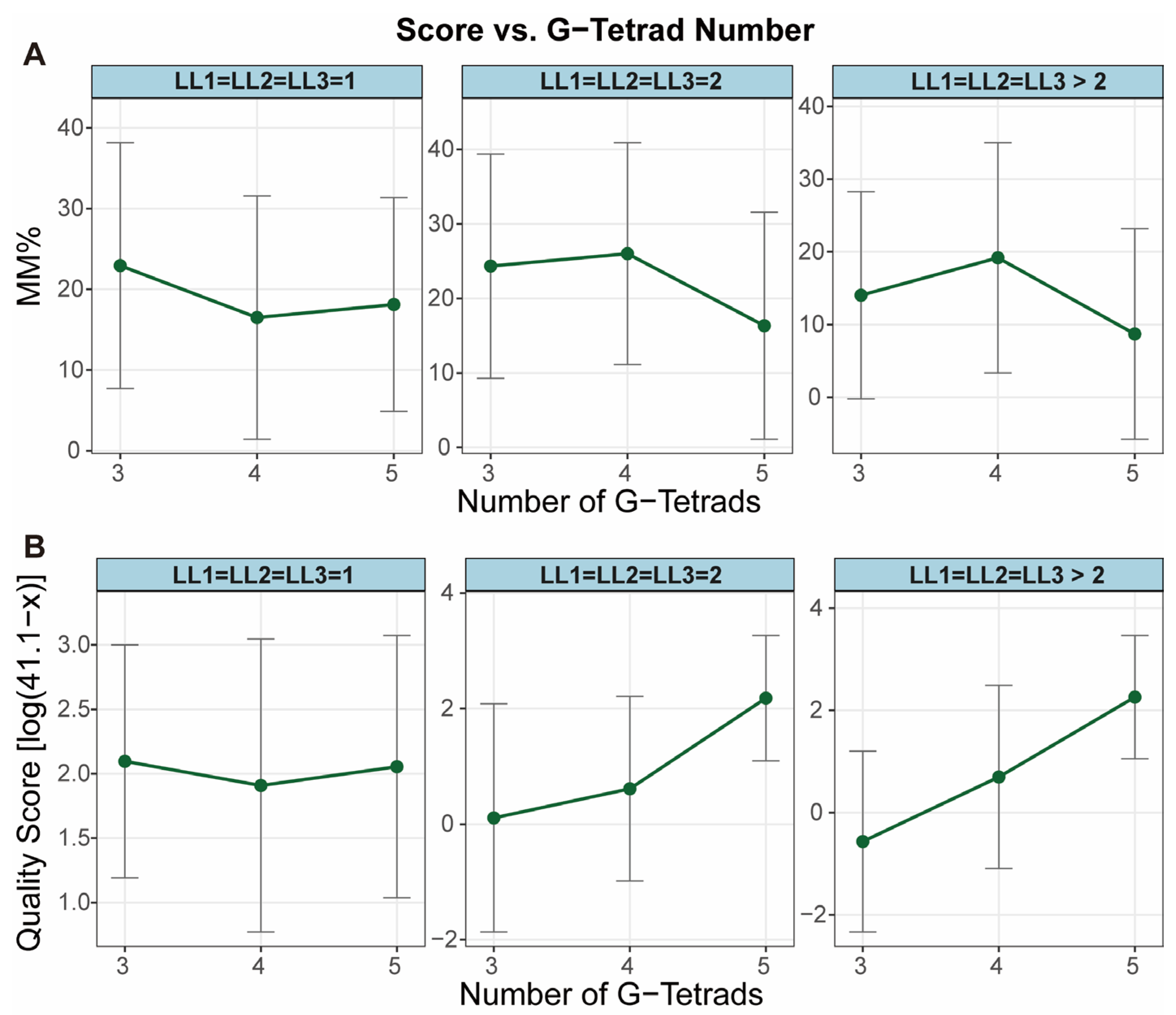

2. The G-Tract Core: The Impact of Size and Imperfections on Stability

2.1. G-Tract Length: Incomplete Monotonic Relationship with Stability

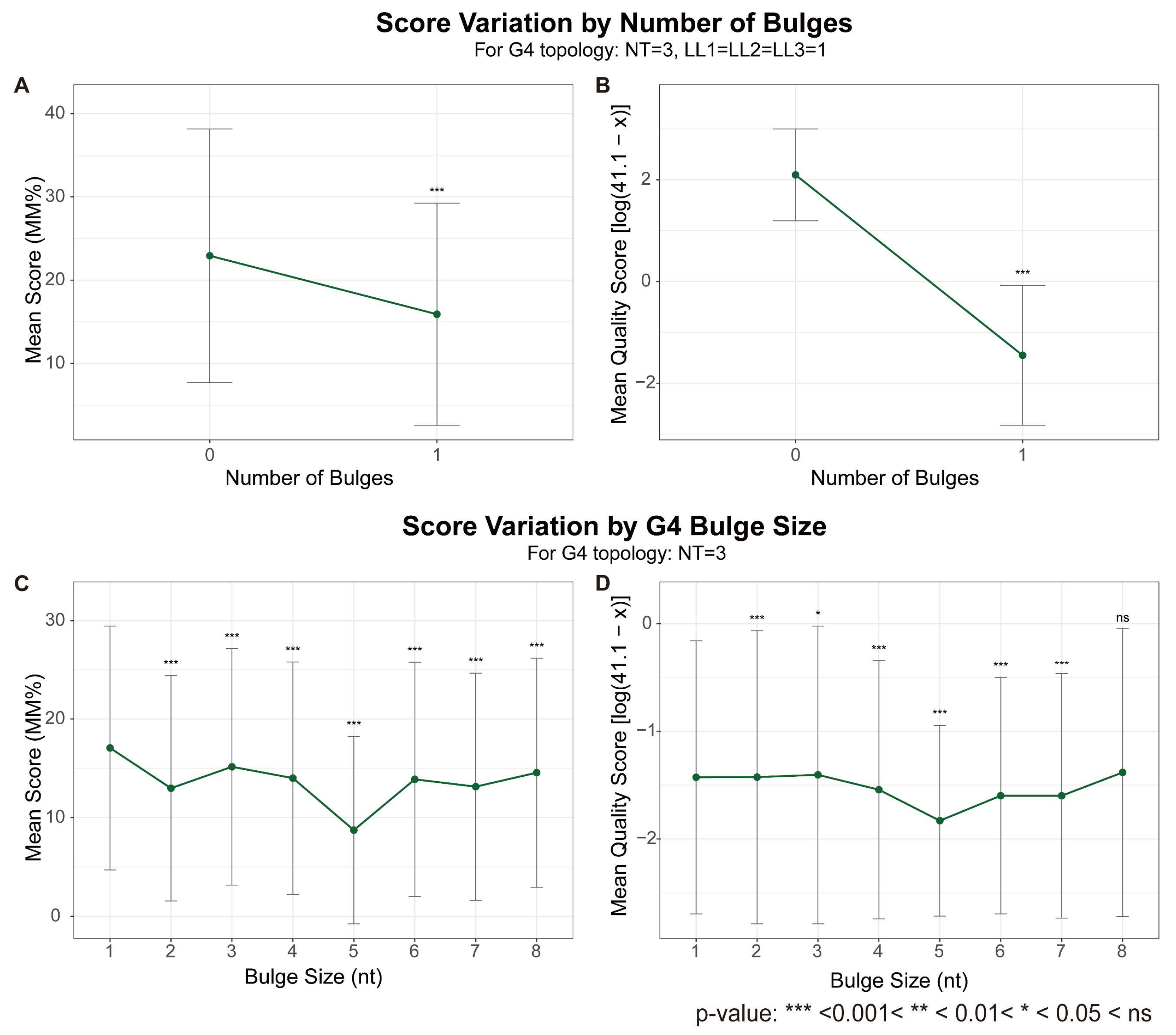

2.2. Bulges in G-Tracts: The Impact of Imperfections

2.3. Aligning the Evidence: G-Tract and Bulge Features in High-Throughput Sequencing Analysis

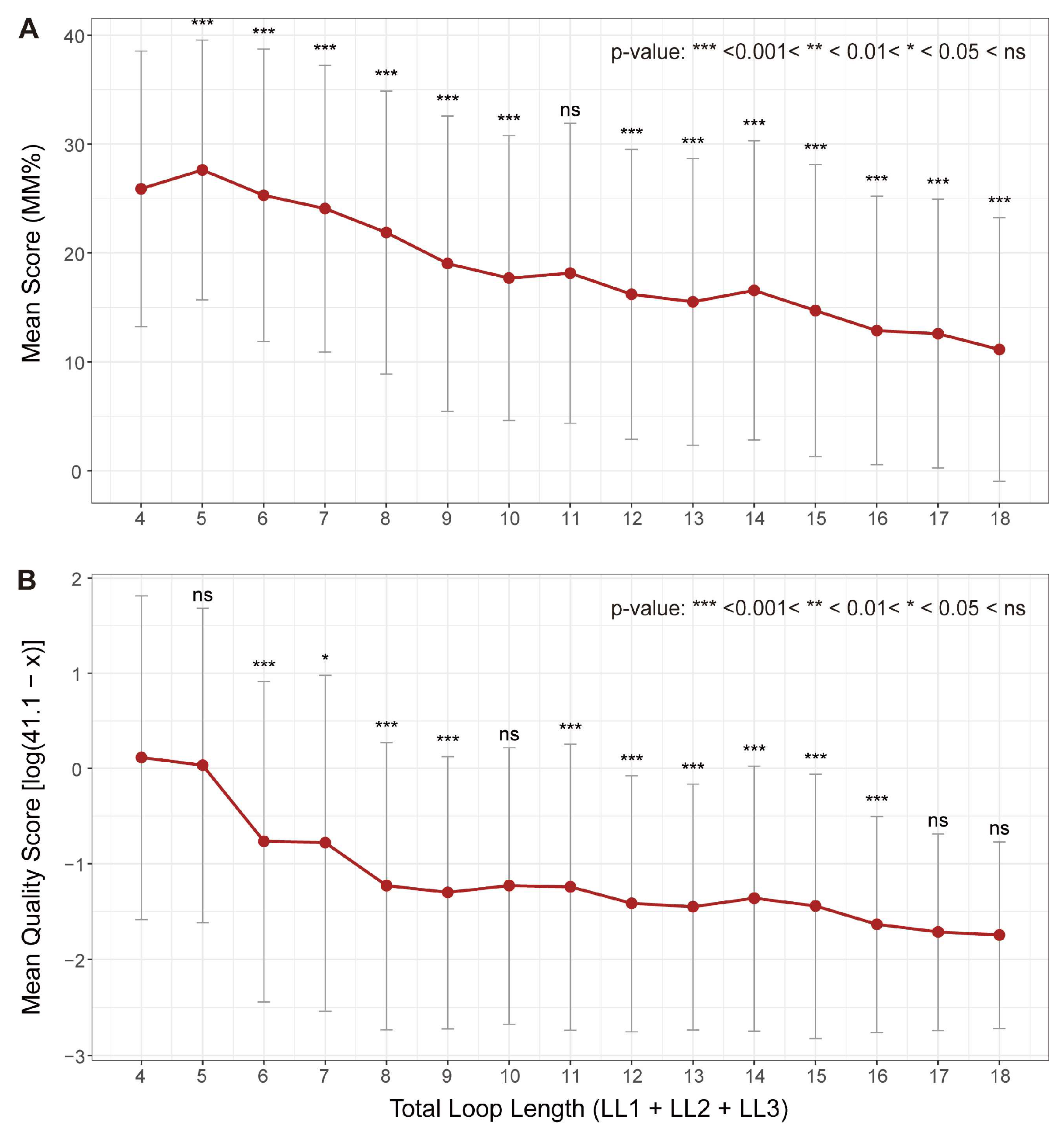

3. The Loops: The Impact of Length, Order and Nucleotide Composition on Stability

3.1. Loop Length: A General Inverse Correlation with Stability

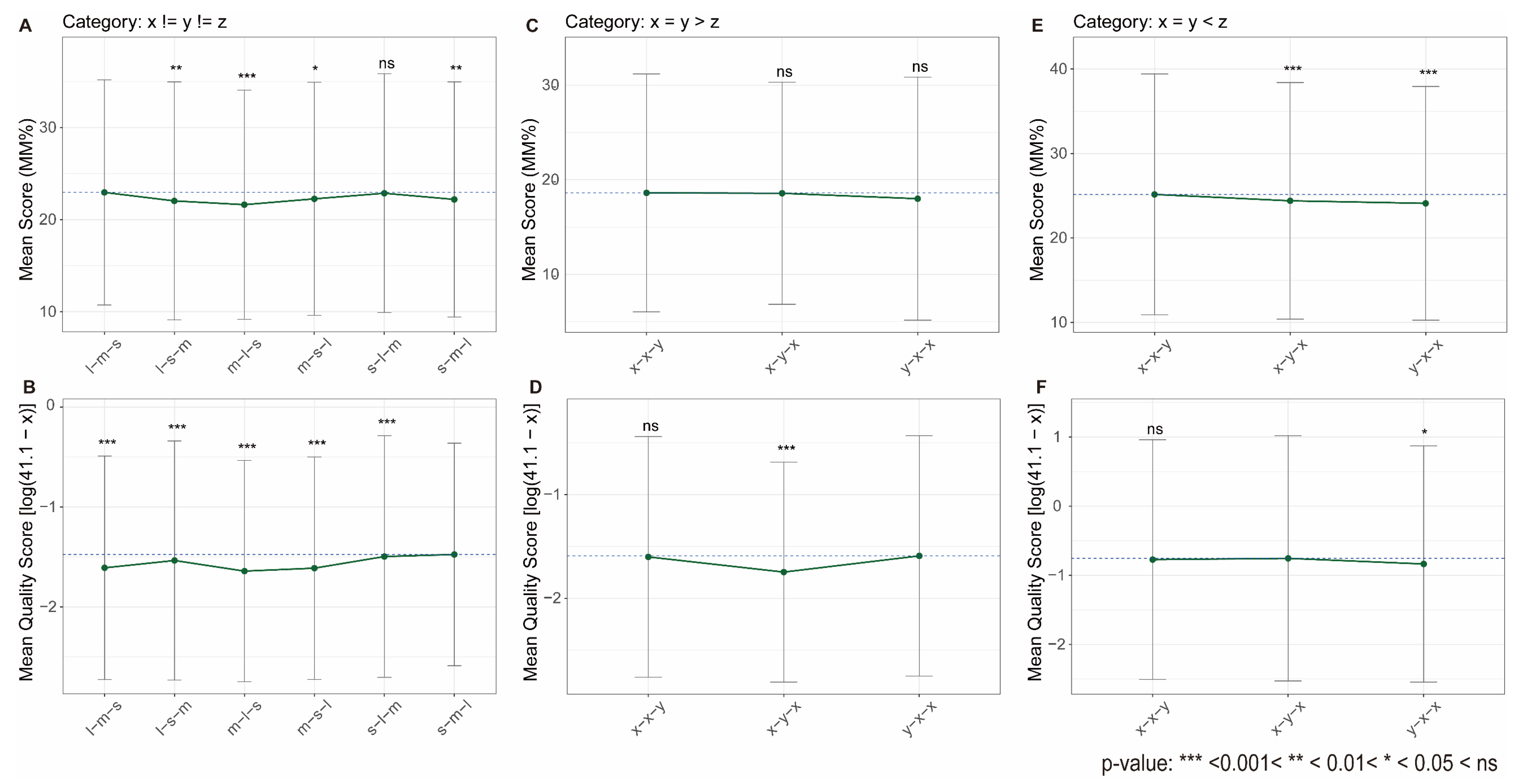

3.2. Loop Permutation: The Critical Role of Sequential Order

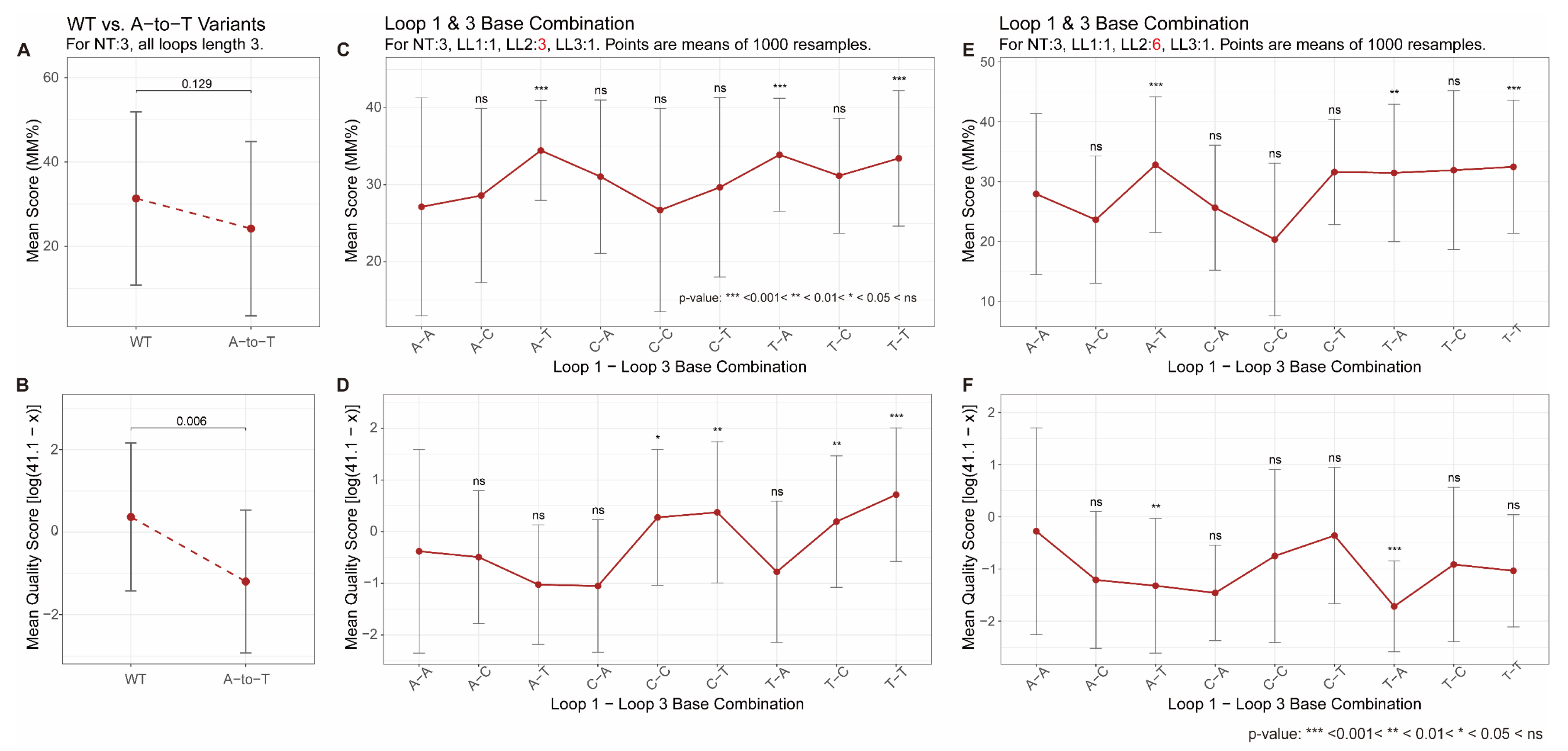

3.3. Loop Nucleotide Composition: Contradictions Depending on Context

3.4. Aligning the Evidence: Interpreting Loop Features in High-Throughput Data

4. The Influence of Flanking Regions on G4 Structure and Stability

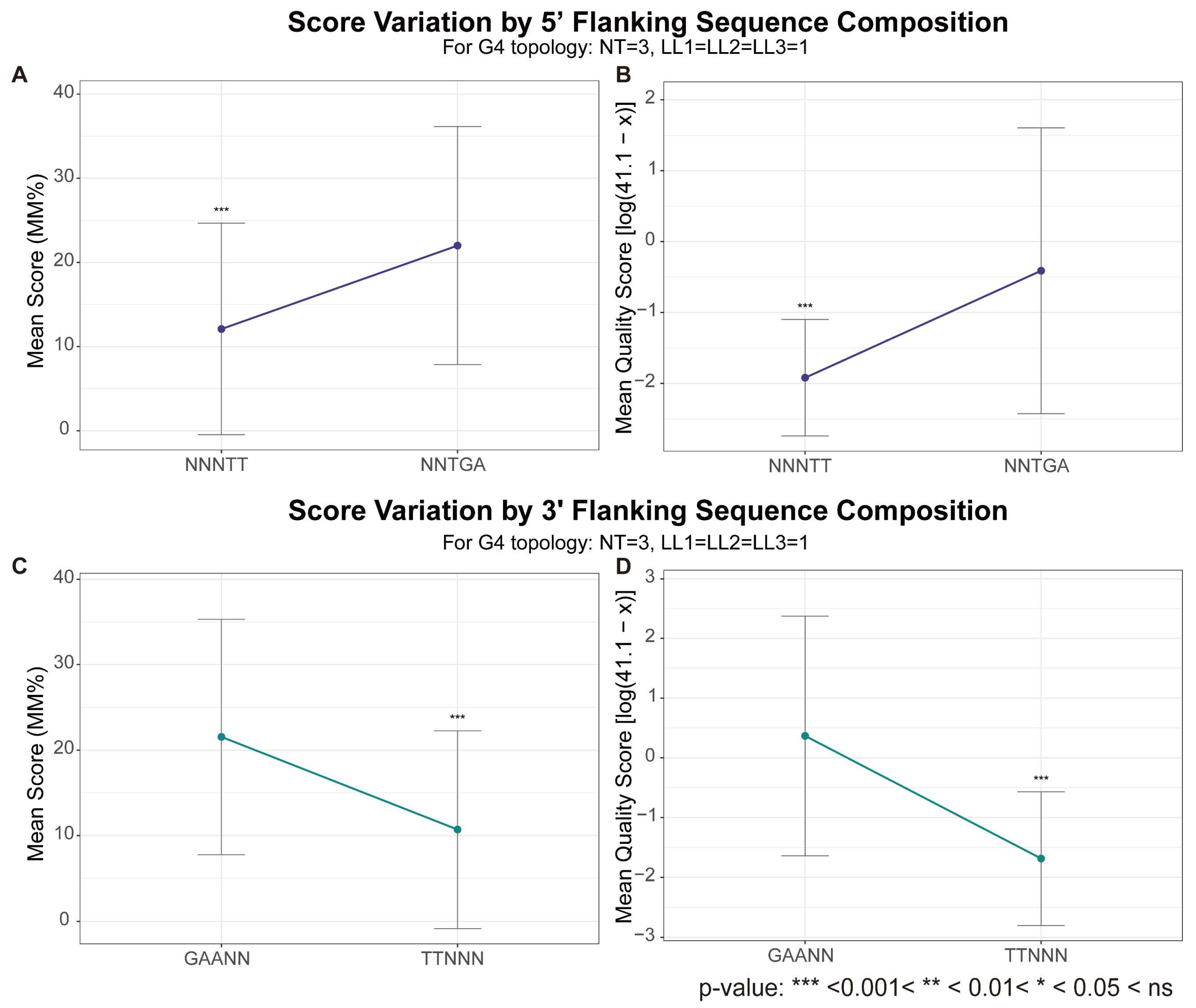

4.1. Flanking Nucleotides as Modulators of G4 Folding

4.2. Aligning the Evidence: The Flanking Effect in a Genomic Context

5. Conclusion and Outlook

5.1. Toward a Unified Understanding of Sequence-Stability Relationships

5.2. Toward Quantitative and Predictive Models

5.3. Unresolved Questions and Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Data Sources and Processing

References

- Varshney, D.; Spiegel, J.; Zyner, K.; Tannahill, D.; Balasubramanian, S. The Regulation and Functions of DNA and RNA G-Quadruplexes. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 459–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaires, J.B. Human Telomeric G-quadruplex: Thermodynamic and Kinetic Studies of Telomeric Quadruplex Stability. FEBS J. 2010, 277, 1098–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane, A.N.; Chaires, J.B.; Gray, R.D.; Trent, J.O. Stability and Kinetics of G-Quadruplex Structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36, 5482–5515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharyya, D.; Mirihana Arachchilage, G.; Basu, S. Metal Cations in G-Quadruplex Folding and Stability. Front. Chem. 2016, 4, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrus, A.; Chen, D.; Dai, J.; Bialis, T.; Jones, R.A.; Yang, D. Human Telomeric Sequence Forms a Hybrid-Type Intramolecular G-Quadruplex Structure with Mixed Parallel/Antiparallel Strands in Potassium Solution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, 2723–2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Y.; Fortin, J.S.; Tye, D.; Gleason-Guzman, M.; Brooks, T.A.; Hurley, L.H. Molecular Cloning of the Human Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Receptor β (PDGFR-β) Promoter and Drug Targeting of the G-Quadruplex-Forming Region to Repress PDGFR-β Expression. Biochemistry 2010, 49, 4208–4219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šponer, J.; Bussi, G.; Stadlbauer, P.; Kührová, P.; Banáš, P.; Islam, B.; Haider, S.; Neidle, S.; Otyepka, M. Folding of Guanine Quadruplex Molecules–Funnel-like Mechanism or Kinetic Partitioning? An Overview from MD Simulation Studies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Gen. Subj. 2017, 1861, 1246–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, V.S.; Marsico, G.; Boutell, J.M.; Di Antonio, M.; Smith, G.P.; Balasubramanian, S. High-Throughput Sequencing of DNA G-Quadruplex Structures in the Human Genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 877–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hon, J.; Martínek, T.; Zendulka, J.; Lexa, M. Pqsfinder: An Exhaustive and Imperfection-Tolerant Search Tool for Potential Quadruplex-Forming Sequences in R. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 3373–3379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stegle, O.; Payet, L.; Mergny, J.-L.; MacKay, D.J.C.; Huppert, J.L. Predicting and Understanding the Stability of G-Quadruplexes. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, i374–i1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hurley, L.H.; Salazar, M. A DNA Polymerase Stop Assay for G-Quadruplex-Interactive Compounds. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999, 27, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiblet, W.M.; DeGiorgio, M.; Cheng, X.; Chiaromonte, F.; Eckert, K.A.; Huang, Y.-F.; Makova, K.D. Selection and Thermostability Suggest G-Quadruplexes Are Novel Functional Elements of the Human Genome. Genome Res. 2021, 31, 1136–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prorok, P.; Artufel, M.; Aze, A.; Coulombe, P.; Peiffer, I.; Lacroix, L.; Guédin, A.; Mergny, J.-L.; Damaschke, J.; Schepers, A.; et al. Involvement of G-Quadruplex Regions in Mammalian Replication Origin Activity. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogasawara, S. Transcription Driven by Reversible Photocontrol of Hyperstable G-Quadruplexes. ACS Synth. Biol. 2018, 7, 2507–2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, K.; Zhang, R.; Tao, T.; Shu, H.; Huang, H.; Sun, X.; Tu, J. Stability Matters: Revealing Causal Roles of G-Quadruplexes (G4s) in Regulation of Chromatin and Transcription. Genes 2025, 16, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Chen, J.; Zheng, K.; You, H. Mechanical Diversity and Folding Intermediates of Parallel-Stranded G-Quadruplexes with a Bulge. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 7179–7188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, H.; Zeng, X.; Xu, Y.; Lim, C.J.; Efremov, A.K.; Phan, A.T.; Yan, J. Dynamics and Stability of Polymorphic Human Telomeric G-Quadruplex under Tension. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 8789–8795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Balasubramanian, S.; Hurley, L.H.; Neidle, S. Targeting G-Quadruplexes in Gene Promoters: A Novel Anticancer Strategy? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2011, 10, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onel, B.; Lin, C.; Yang, D. DNA G-Quadruplex and Its Potential as Anticancer Drug Target. Sci. China Chem. 2014, 57, 1605–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, F.-Y.; Jiang, Z.-Z.; Guo, M.; Tan, X.-Z.; Chen, F.; Xi, X.-G.; Xu, Y. G-Quadruplex DNA: A Novel Target for Drug Design. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2021, 78, 6557–6583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.V.; Wang, T.; Chappeta, V.R.; Wu, G.; Onel, B.; Chawla, R.; Quijada, H.; Camp, S.M.; Chiang, E.T.; Lassiter, Q.R.; et al. The Consequences of Overlapping G-Quadruplexes and i-Motifs in the Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Receptor β Core Promoter Nuclease Hypersensitive Element Can Explain the Unexpected Effects of Mutations and Provide Opportunities for Selective Targeting of Both Structures by Small Molecules to Downregulate Gene Expression. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 7456–7475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puig Lombardi, E.; Holmes, A.; Verga, D.; Teulade-Fichou, M.-P.; Nicolas, A.; Londoño-Vallejo, A. Thermodynamically Stable and Genetically Unstable G-Quadruplexes are Depleted in Genomes across Species. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 6098–6113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mergny, J.-L.; Phan, A.-T.; Lacroix, L. Following G-quartet Formation by UV-spectroscopy. FEBS Lett. 1998, 435, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergny, J.; Lacroix, L. UV Melting of G-Quadruplexes. CP Nucleic Acid. Chem. 2009, 37, 17.1.1–17.1.15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachwal, P.A.; Fox, K.R. Quadruplex Melting. Methods 2007, 43, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, I.; Chowdhry, B.Z.; Jenkins, T.C. Calorimetric Techniques in the Study of High-Order DNA-Drug Interactions. In Methods in Enzymology; Drug-Nucleic Acid Interactions; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001; Volume 340, pp. 109–149. [Google Scholar]

- De Cian, A.; Guittat, L.; Kaiser, M.; Saccà, B.; Amrane, S.; Bourdoncle, A.; Alberti, P.; Teulade-Fichou, M.-P.; Lacroix, L.; Mergny, J.-L. Fluorescence-Based Melting Assays for Studying Quadruplex Ligands. Methods 2007, 42, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Saneyoshi, H.; Xu, P.; Oguri, N.; Yamashita, A.; Xu, Y. Manipulating DNA and RNA Structures via Click-to-Release Caged Nucleic Acids for Biological and Biomedical Applications. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, gkaf571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsico, G.; Chambers, V.S.; Sahakyan, A.B.; McCauley, P.; Boutell, J.M.; Antonio, M.D.; Balasubramanian, S. Whole Genome Experimental Maps of DNA G-Quadruplexes in Multiple Species. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 3862–3874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, J.; Duan, M.; Liu, W.; Lu, N.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, X.; Lu, Z. Direct Genome-Wide Identification of G-Quadruplex Structures by Whole-Genome Resequencing. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, Q.-M.; Wang, Y.-R.; Xi, X.-G.; Hou, X.-M. DNA-Unwinding Activity of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Pif1 is Modulated by Thermal Stability, Folding Conformation, and Loop Lengths of G-Quadruplex DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 18504–18513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahakyan, A.B.; Chambers, V.S.; Marsico, G.; Santner, T.; Di Antonio, M.; Balasubramanian, S. Machine Learning Model for Sequence-Driven DNA G-Quadruplex Formation. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 14535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, A.; Maiti, S. Stability and Molecular Recognition of Quadruplexes with Different Loop Length in the Absence and Presence of Molecular Crowding Agents. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 8784–8792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdian Doghaei, A.; Housaindokht, M.R.; Bozorgmehr, M.R. Molecular Crowding Effects on Conformation and Stability of G-Quadruplex DNA Structure: Insights from Molecular Dynamics Simulation. J. Theor. Biol. 2015, 364, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aznauryan, M.; Birkedal, V. Dynamics of G-Quadruplex Formation under Molecular Crowding. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2023, 14, 10354–10360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jana, J.; Weisz, K. Thermodynamic Stability of G-Quadruplexes: Impact of Sequence and Environment. ChemBioChem 2021, 22, 2848–2856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishio, M.; Tsukakoshi, K.; Ikebukuro, K. G-Quadruplex: Flexible Conformational Changes by Cations, pH, Crowding and Its Applications to Biosensing. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 178, 113030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H.-S.; Dong, M.-J.; Gao, F. G4Bank: A Database of Experimentally Identified DNA G-Quadruplex Sequences. Interdiscip. Sci.-Comput. Life Sci. 2023, 15, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zok, T.; Kraszewska, N.; Miskiewicz, J.; Pielacinska, P.; Zurkowski, M.; Szachniuk, M. ONQUADRO: A Database of Experimentally Determined Quadruplex Structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D253–D258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachwal, P.A.; Brown, T.; Fox, K.R. Effect of G-Tract Length on the Topology and Stability of Intramolecular DNA Quadruplexes. Biochemistry 2007, 46, 3036–3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugaut, A.; Balasubramanian, S. A Sequence-Independent Study of the Influence of Short Loop Lengths on the Stability and Topology of Intramolecular DNA G-Quadruplexes. Biochemistry 2007, 47, 689–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cang, X.; Šponer, J.; Cheatham, T.E. III Insight into G-DNA Structural Polymorphism and Folding from Sequence and Loop Connectivity through Free Energy Analysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 14270–14279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tippana, R.; Xiao, W.; Myong, S. G-Quadruplex Conformation and Dynamics Are Determined by Loop Length and Sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 8106–8114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papp, C.; Mukundan, V.T.; Jenjaroenpun, P.; Winnerdy, F.R.; Ow, G.S.; Phan, A.T.; Kuznetsov, V.A. Stable Bulged G-Quadruplexes in the Human Genome: Identification, Experimental Validation and Functionalization. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, 4148–4177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, S.; Tateishi-Karimata, H.; Ohyama, T.; Sugimoto, N. Imperfect G-Quadruplex as an Emerging Candidate for Transcriptional Regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, gkaf164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Zheng, K.; Zhang, J.; Liu, H.; He, Y.; Yuan, B.; Hao, Y.; Tan, Z. Guanine-Vacancy–Bearing G-Quadruplexes Responsive to Guanine Derivatives. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 14581–14586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grün, J.T.; Hennecker, C.; Klötzner, D.-P.; Harkness, R.W.; Bessi, I.; Heckel, A.; Mittermaier, A.K.; Schwalbe, H. Conformational Dynamics of Strand Register Shifts in DNA G-Quadruplexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 142, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukundan, V.T.; Phan, A.T. Bulges in G-Quadruplexes: Broadening the Definition of G-Quadruplex-Forming Sequences. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 5017–5028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngoc Nguyen, T.Q.; Lim, K.W.; Phan, A.T. Duplex Formation in a G-Quadruplex Bulge. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 10567–10575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, A.T.; Modi, Y.S.; Patel, D.J. Propeller-Type Parallel-Stranded G-Quadruplexes in the Human c-Myc Promoter. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 8710–8716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risitano, A.; Fox, K. Influence of Loop Size on the Stability of Intramolecular DNA Quadruplexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, 2598–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, H.; Reszka, A.P.; Huppert, J.; Ladame, S.; Rankin, S.; Venkitaraman, A.R.; Neidle, S.; Balasubramanian, S. A Conserved Quadruplex Motif Located in a Transcription Activation Site of the Human C-Kit Oncogene. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 7854–7860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guédin, A.; Gros, J.; Alberti, P.; Mergny, J.-L. How Long Is Too Long? Effects of Loop Size on G-Quadruplex Stability. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, 7858–7868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, F.; Ma, Y.; Guan, Y. Effects of Central Loop Length and Metal Ions on the Thermal Stability of G-Quadruplexes. Molecules 2019, 24, 1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smargiasso, N.; Rosu, F.; Hsia, W.; Colson, P.; Baker, E.S.; Bowers, M.T.; De Pauw, E.; Gabelica, V. G-Quadruplex DNA Assemblies: Loop Length, Cation Identity, and Multimer Formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 10208–10216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, K.W.; Khong, Z.J.; Phan, A.T. Thermal Stability of DNA Quadruplex–Duplex Hybrids. Biochemistry 2013, 53, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, K.W.; Jenjaroenpun, P.; Low, Z.J.; Khong, Z.J.; Ng, Y.S.; Kuznetsov, V.A.; Phan, A.T. Duplex Stem-Loop-Containing Quadruplex Motifs in the Human Genome: A Combined Genomic and Structural Study. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, 5630–5646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravichandran, S.; Razzaq, M.; Parveen, N.; Ghosh, A.; Kim, K.K. The Effect of Hairpin Loop on the Structure and Gene Expression Activity of the Long-Loop G-Quadruplex. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 10689–10706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wu, P.; Ohmichi, T.; Sugimoto, N. Characterization and Thermodynamic Properties of Quadruplex/Duplex Competition. FEBS Lett. 2002, 526, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotticchia, I.; Amato, J.; Pagano, B.; Novellino, E.; Petraccone, L.; Giancola, C. How are Thermodynamically Stable G-Quadruplex–Duplex Hybrids? J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2015, 121, 1121–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzakis, E.; Okamoto, K.; Yang, D. Thermodynamic Stability and Folding Kinetics of the Major G-Quadruplex and Its Loop Isomers Formed in the Nuclease Hypersensitive Element in the Human c-Myc Promoter: Effect of Loops and Flanking Segments on the Stability of Parallel-Stranded Intramolecular G-Quadruplexes. Biochemistry 2010, 49, 9152–9160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Cheng, Y.; Hao, J.; Jia, G.; Zhou, J.; Mergny, J.-L.; Li, C. Loop Permutation Affects the Topology and Stability of G-Quadruplexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, 9264–9275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Cheng, M.; Stadlbauer, P.; Šponer, J.; Mergny, J.-L.; Ju, H.; Zhou, J. Exploring Sequence Space to Design Controllable G-Quadruplex Topology Switches. CCS Chem. 2022, 4, 3036–3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, P.; Hatzakis, E.; Guo, K.; Carver, M.; Yang, D. Solution Structure of the Major G-Quadruplex Formed in the Human VEGF Promoter in K+: Insights into Loop Interactions of the Parallel G-Quadruplexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, 10584–10592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beniaminov, A.; Shchyolkina, A.; Kaluzhny, D. Conformational Features of Intramolecular G4-DNA Constrained by Single-Nucleotide Loops. Biochimie 2019, 160, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Maiti, S. A Thermodynamic Overview of Naturally Occurring Intramolecular DNA Quadruplexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36, 5610–5622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guédin, A.; De Cian, A.; Gros, J.; Lacroix, L.; Mergny, J.-L. Sequence Effects in Single-Base Loops for Quadruplexes. Biochimie 2008, 90, 686–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, C.M.; Lee, H.-T.; Marky, L.A. Unfolding Thermodynamics of Intramolecular G-Quadruplexes: Base Sequence Contributions of the Loops. J. Phys. Chem. B 2008, 113, 2587–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chu, I.-T.; Yeh, T.-A.; Chen, D.-Y.; Wang, C.-L.; Chang, T.-C. Effects of Length and Loop Composition on Structural Diversity and Similarity of (G3TG3NmG3TG3) G-Quadruplexes. Molecules 2020, 25, 1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagatoishi, S.; Isono, N.; Tsumoto, K.; Sugimoto, N. Loop Residues of Thrombin-Binding DNA Aptamer Impact G-Quadruplex Stability and Thrombin Binding. Biochimie 2011, 93, 1231–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guédin, A.; Alberti, P.; Mergny, J.-L. Stability of Intramolecular Quadruplexes: Sequence Effects in the Central Loop. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, 5559–5567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Y.; Macgregor, R.B., Jr. A Thermodynamic Study of Adenine and Thymine Substitutions in the Loops of the Oligodeoxyribonucleotide HTel. J. Phys. Chem. B 2016, 120, 8830–8836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, B.A.; Hudson, J.S.; Ding, L.; Lewis, E.; Sheardy, R.D.; Kharlampieva, E.; Graves, D. Stability of the Na+ Form of the Human Telomeric G-Quadruplex: Role of Adenines in Stabilizing G-Quadruplex Structure. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 844–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Xiao, S.; Liang, H. Structural Dynamics of Human Telomeric G-Quadruplex Loops Studied by Molecular Dynamics Simulations. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e71380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenarčič Živković, M.; Rozman, J.; Plavec, J. Adenine-Driven Structural Switch from a Two- to Three-Quartet DNA G-Quadruplex. Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 15621–15625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakata, M.; Kosaka, N.; Kawauchi, K.; Miyoshi, D. Quantitative Effects of the Loop Region on Topology, Thermodynamics, and Cation Binding of DNA G-Quadruplexes. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 35028–35036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Chen, T.; Lu, N.; Pan, X.; Tu, J. Decoding G-Quadruplex Stability: The Role of Loop Architecture and Sequence Context in the Human Genome. Biochimie 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrus, A.; Chen, D.; Dai, J.; Jones, R.A.; Yang, D. Solution Structure of the Biologically Relevant G-Quadruplex Element in the Human c-MYC Promoter. Implications for G-Quadruplex Stabilization. Biochimie 2005, 44, 2048–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, K.W.; Lacroix, L.; Yue, D.J.E.; Lim, J.K.C.; Lim, J.M.W.; Phan, A.T. Coexistence of Two Distinct G-Quadruplex Conformations in the hTERT Promoter. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 12331–12342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrane, S.; Adrian, M.; Heddi, B.; Serero, A.; Nicolas, A.; Mergny, J.-L.; Phan, A.T. Formation of Pearl-Necklace Monomorphic G-Quadruplexes in the Human CEB25 Minisatellite. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 5807–5816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Cheng, M.; Salgado, G.F.; Stadlbauer, P.; Zhang, X.; Amrane, S.; Guédin, A.; He, F.; Šponer, J.; Ju, H.; et al. The Beginning and the End: Flanking Nucleotides Induce a Parallel G-Quadruplex Topology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 9548–9559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugaut, A.; Alberti, P. Understanding the Stability of DNA G-Quadruplex Units in Long Human Telomeric Strands. Biochimie 2015, 113, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Dai, J.; Veliath, E.; Jones, R.A.; Yang, D. Structure of a Two-G-Tetrad Intramolecular G-Quadruplex Formed by a Variant Human Telomeric Sequence in K+ Solution: Insights into the Interconversion of Human Telomeric G-Quadruplex Structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 38, 1009–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavc, D.; Wang, B.; Spindler, L.; Drevenšek-Olenik, I.; Plavec, J.; Šket, P. GC Ends Control Topology of DNA G-Quadruplexes and Their Cation-Dependent Assembly. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 2749–2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, N.Q.; Phan, A.T. Monomer–Dimer Equilibrium for the 5′–5′ Stacking of Propeller-Type Parallel-Stranded G-Quadruplexes: NMR Structural Study. Chem. Eur. J. 2012, 18, 14752–14759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, A.T. Human Telomeric G-quadruplex: Structures of DNA and RNA Sequences. FEBS J. 2010, 277, 1107–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacký, J.; Vorlíčková, M.; Kejnovská, I.; Mojzeš, P. Polymorphism of Human Telomeric Quadruplex Structure Controlled by DNA Concentration: A Raman Study. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 41, 1005–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sequence Feature | Patterns from Biophysical Studies | Consistency with High-Throughput Data | Key Observations from High-Throughput Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| G-Tract Length | Stability generally increases with length, though non-monotonically; anomalous stability observed for 3-layer G4s with 1-nt loops [40] | Generally consistent (Both methods, Figure 2). |

|

| Bulges | Bulges are generally destabilizing; the effect is size-dependent [45,48]; compensatory stabilization was reported [49]. | Consistent (Both methods, Figure 3) |

|

| Total Loop Length | Strong inverse correlation with stability was observed [53]. | Consistent (Both methods, Figure 4) |

|

| Loop Permutation | Significant impact on stability and topology was observed; central loop length plays dominant role [62,64] | Partially Consistent (Figure 5) |

|

| Loop Base Composition | The effect is highly context-dependent; adenine can be stabilizing or destabilizing depending on structural context [67,70,71,72,73] | Partially Consistent (Figure 6) |

|

| Flanking Regions | The effect is composition-sensitive; specific flanking sequences differentially modulate G4 stability, with 5′-TGA/3′-GAA conferring stabilization [61] and 5′-TT/3′-TT producing destabilization [81]. | Consistent (Both methods, Figure 7) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xiao, K.; Fu, J.; Zhang, R.; Tu, J. Sequence Determinants of G-Quadruplex Thermostability: Aligning Evidence from High-Precision Biophysics and High-Throughput Genomics. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1632. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15111632

Xiao K, Fu J, Zhang R, Tu J. Sequence Determinants of G-Quadruplex Thermostability: Aligning Evidence from High-Precision Biophysics and High-Throughput Genomics. Biomolecules. 2025; 15(11):1632. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15111632

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiao, Ke, Jiye Fu, Rongxin Zhang, and Jing Tu. 2025. "Sequence Determinants of G-Quadruplex Thermostability: Aligning Evidence from High-Precision Biophysics and High-Throughput Genomics" Biomolecules 15, no. 11: 1632. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15111632

APA StyleXiao, K., Fu, J., Zhang, R., & Tu, J. (2025). Sequence Determinants of G-Quadruplex Thermostability: Aligning Evidence from High-Precision Biophysics and High-Throughput Genomics. Biomolecules, 15(11), 1632. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15111632