Emerging Issues Regarding the Effects of the Microbiome on Lung Cancer Immunotherapy

Abstract

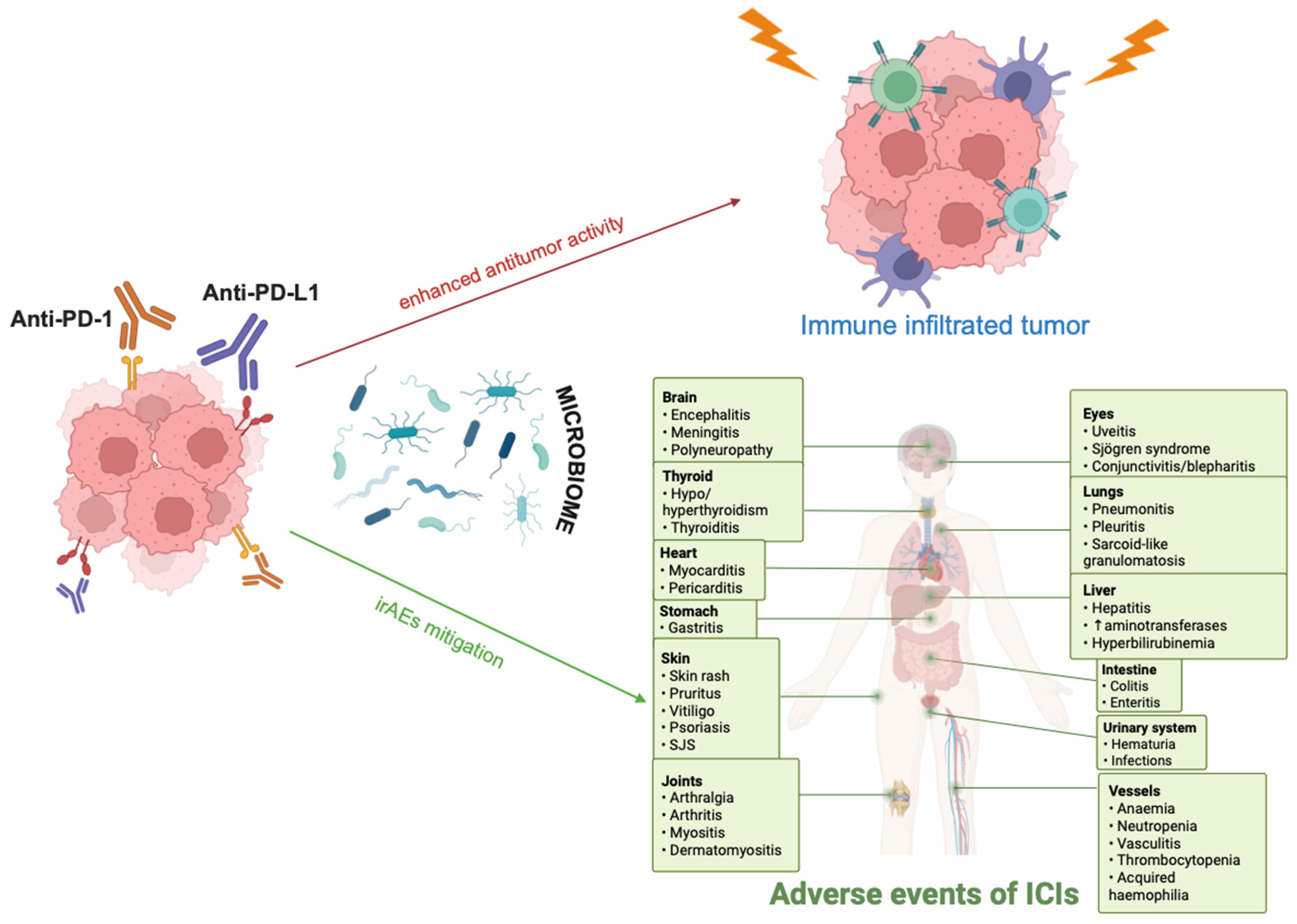

1. Introduction

2. Gut Microbiome Composition in Lung Cancer Immunotherapy Responders Versus Non-Responders

3. Molecular Mechanisms Engaged in the Interplay Between Lung Cancer Immunotherapy and Microbiome

4. Microbiome-Centered Interventions to Improve Immunotherapy Responses in Lung Cancer

4.1. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT)

4.2. Probiotics

4.3. Diet and Nutrition

5. Conclusions—Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, M.; Liu, C.; Tu, J.; Tang, M.; Ashrafizadeh, M.; Nabavi, N.; Sethi, G.; Zhao, P.; Liu, S. Advances in Cancer Immunotherapy: Historical Perspectives, Current Developments, and Future Directions. Mol. Cancer 2025, 24, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zer, A.; Ahn, M.-J.; Barlesi, F.; Bubendorf, L.; De Ruysscher, D.; Garrido, P.; Gautschi, O.; Hendriks, L.E.; Jänne, P.A.; Kerr, K.M.; et al. Early and Locally Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-Up. Ann. Oncol. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resuli, B.; Kauffmann-Guerrero, D. Novel Immunotherapeutic Approaches in Lung Cancer: Driving beyond Programmed Death-1/Programmed Death Ligand-1 and Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte-Associated Protein-4. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2025, 37, 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russano, M.; La Cava, G.; Cortellini, A.; Citarella, F.; Galletti, A.; Di Fazio, G.R.; Santo, V.; Brunetti, L.; Vendittelli, A.; Fioroni, I.; et al. Immunotherapy for Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Therapeutic Advances and Biomarkers. Curr. Oncol. Tor. Ont. 2023, 30, 2366–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putzu, C.; Canova, S.; Paliogiannis, P.; Lobrano, R.; Sala, L.; Cortinovis, D.L.; Colonese, F. Duration of Immunotherapy in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Survivors: A Lifelong Commitment? Cancers 2023, 15, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moliner, L.; Zellweger, N.; Schmid, S.; Bertschinger, M.; Waibel, C.; Cerciello, F.; Froesch, P.; Mark, M.; Bettini, A.; Häuptle, P.; et al. First-Line Chemo-Immunotherapy in SCLC: Outcomes of a Binational Real-World Study. JTO Clin. Res. Rep. 2025, 6, 100744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zugazagoitia, J.; Osma, H.; Baena, J.; Ucero, A.C.; Paz-Ares, L. Facts and Hopes on Cancer Immunotherapy for Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2024, 30, 2872–2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cali Daylan, A.E.; Halmos, B. Long-Term Benefit of Immunotherapy in Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: The Tale of the Tail. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2023, 12, 1636–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discov. 2022, 12, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobels, A.; Van Marcke, C.; Jordan, B.F.; Van Hul, M.; Cani, P.D. The Gut Microbiome and Cancer: From Tumorigenesis to Therapy. Nat. Metab. 2025, 7, 895–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, P.; Xue, X.; Bukhari, I.; Qiu, C.; Li, Y.; Zheng, P.; Mi, Y. Gut Microbiota and Its Therapeutic Implications in Tumor Microenvironment Interactions. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1287077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Feng, T.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, Q.; Zhu, L. Leveraging Gut Microbiota for Enhanced Immune Checkpoint Blockade in Solid Tumor Therapy. Chin. Med. J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Dong, H.; Xia, L.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Shen, Y.; Zheng, H.; Yao, C.; Wang, Y.; Lu, S. The Diversity of Gut Microbiome Is Associated with Favorable Responses to Anti–Programmed Death 1 Immunotherapy in Chinese Patients with NSCLC. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2019, 14, 1378–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Jie, Z.; Fan, X. Gut Microbes and Immunotherapy for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Systematic Review. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1518474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, S.; Kikuchi, T. Does the Gut Microbiota Play a Key Role in PD-1/PD-L1 Blockade Therapy? Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2020, 9, 438–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H.; Cho, S.-Y.; Yoon, Y.; Park, C.; Sohn, J.; Jeong, J.-J.; Jeon, B.-N.; Jang, M.; An, C.; Lee, S.; et al. Bifidobacterium Bifidum Strains Synergize with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors to Reduce Tumour Burden in Mice. Nat. Microbiol. 2021, 6, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dora, D.; Ligeti, B.; Kovacs, T.; Revisnyei, P.; Galffy, G.; Dulka, E.; Krizsán, D.; Kalcsevszki, R.; Megyesfalvi, Z.; Dome, B.; et al. Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients Treated with Anti-PD1 Immunotherapy Show Distinct Microbial Signatures and Metabolic Pathways According to Progression-Free Survival and PD-L1 Status. OncoImmunology 2023, 12, 2204746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.L.; Larkinson, M.L.Y.; Clarke, T.B. Immunological Design of Commensal Communities to Treat Intestinal Infection and Inflammation. PLoS Pathog. 2021, 17, e1009191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routy, B.; Le Chatelier, E.; Derosa, L.; Duong, C.P.M.; Alou, M.T.; Daillère, R.; Fluckiger, A.; Messaoudene, M.; Rauber, C.; Roberti, M.P.; et al. Gut Microbiome Influences Efficacy of PD-1–Based Immunotherapy against Epithelial Tumors. Science 2018, 359, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, S.; Feng, L.; Liu, H.; Mao, Y.; Yu, Z. Gut Microbiome Affects the Response to Immunotherapy in Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Thorac. Cancer 2024, 15, 1149–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukhopadhya, I.; Louis, P. Gut Microbiota-Derived Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Their Role in Human Health and Disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2025, 23, 635–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, M.; Nagatomo, R.; Doi, K.; Shimizu, J.; Baba, K.; Saito, T.; Matsumoto, S.; Inoue, K.; Muto, M. Association of Short-Chain Fatty Acids in the Gut Microbiome with Clinical Response to Treatment with Nivolumab or Pembrolizumab in Patients with Solid Cancer Tumors. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e202895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Jiang, J. Exploring the Regulatory Mechanism of Intestinal Flora Based on PD-1 Receptor/Ligand Targeted Cancer Immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1359029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traisaeng, S.; Herr, D.R.; Kao, H.-J.; Chuang, T.-H.; Huang, C.-M. A Derivative of Butyric Acid, the Fermentation Metabolite of Staphylococcus Epidermidis, Inhibits the Growth of a Staphylococcus Aureus Strain Isolated from Atopic Dermatitis Patients. Toxins 2019, 11, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedayat, F.; Faghfuri, E. Harnessing Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors for Enhanced Cancer Immunotherapy. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2025, 997, 177620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazziotta, C.; Lanzillotti, C.; Gafà, R.; Touzé, A.; Durand, M.-A.; Martini, F.; Rotondo, J.C. The Role of Histone Post-Translational Modifications in Merkel Cell Carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 832047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.-F.; Shao, J.-H.; Liao, Y.-T.; Wang, L.-N.; Jia, Y.; Dong, P.-J.; Liu, Z.-Z.; He, D.-D.; Li, C.; Zhang, X. Regulation of Short-Chain Fatty Acids in the Immune System. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1186892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachem, A.; Makhlouf, C.; Binger, K.J.; De Souza, D.P.; Tull, D.; Hochheiser, K.; Whitney, P.G.; Fernandez-Ruiz, D.; Dähling, S.; Kastenmüller, W.; et al. Microbiota-Derived Short-Chain Fatty Acids Promote the Memory Potential of Antigen-Activated CD8+ T Cells. Immunity 2019, 51, 285–297.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorgdrager, F.J.H.; Naudé, P.J.W.; Kema, I.P.; Nollen, E.A.; Deyn, P.P.D. Tryptophan Metabolism in Inflammaging: From Biomarker to Therapeutic Target. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tintelnot, J.; Xu, Y.; Lesker, T.R.; Schönlein, M.; Konczalla, L.; Giannou, A.D.; Pelczar, P.; Kylies, D.; Puelles, V.G.; Bielecka, A.A.; et al. Microbiota-Derived 3-IAA Influences Chemotherapy Efficacy in Pancreatic Cancer. Nature 2023, 615, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mager, L.F.; Burkhard, R.; Pett, N.; Cooke, N.C.A.; Brown, K.; Ramay, H.; Paik, S.; Stagg, J.; Groves, R.A.; Gallo, M.; et al. Microbiome-Derived Inosine Modulates Response to Checkpoint Inhibitor Immunotherapy. Science 2020, 369, 1481–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Gnanaprakasam, J.N.R.; Chen, X.; Kang, S.; Xu, X.; Sun, H.; Liu, L.; Rodgers, H.; Miller, E.; Cassel, T.A.; et al. Inosine Is an Alternative Carbon Source for CD8+-T-Cell Function under Glucose Restriction. Nat. Metab. 2020, 2, 635–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, K.C.; Araya, R.E.; Huang, A.; Chen, Q.; Di Modica, M.; Rodrigues, R.R.; Lopès, A.; Johnson, S.B.; Schwarz, B.; Bohrnsen, E.; et al. Microbiota Triggers STING-Type I IFN-Dependent Monocyte Reprogramming of the Tumor Microenvironment. Cell 2021, 184, 5338–5356.e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruch, E.N.; Youngster, I.; Ben-Betzalel, G.; Ortenberg, R.; Lahat, A.; Katz, L.; Adler, K.; Dick-Necula, D.; Raskin, S.; Bloch, N.; et al. Fecal Microbiota Transplant Promotes Response in Immunotherapy-Refractory Melanoma Patients. Science 2021, 371, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, W.; Liang, H.; Bugno, J.; Xu, Q.; Ding, X.; Yang, K.; Fu, Y.; Weichselbaum, R.R.; Zhao, X.; Wang, L. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG Induces cGAS/STING- Dependent Type I Interferon and Improves Response to Immune Checkpoint Blockade. Gut 2022, 71, 521–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.S.; Gazzaniga, F.S.; Wu, M.; Luthens, A.K.; Gillis, J.; Zheng, W.; LaFleur, M.W.; Johnson, S.B.; Morad, G.; Park, E.M.; et al. Targeting PD-L2–RGMb Overcomes Microbiome-Related Immunotherapy Resistance. Nature 2023, 617, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Yu, S.; Zhu, B.; Bedoret, D.; Bu, X.; Francisco, L.M.; Hua, P.; Duke-Cohan, J.S.; Umetsu, D.T.; Sharpe, A.H.; et al. RGMb Is a Novel Binding Partner for PD-L2 and Its Engagement with PD-L2 Promotes Respiratory Tolerance. J. Exp. Med. 2014, 211, 943–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Du, J.; Gao, Z.; Sun, H.; Mei, M.; Wang, Y.; Ren, Y.; Zhou, X. Evolving Landscape of PD-L2: Bring New Light to Checkpoint Immunotherapy. Br. J. Cancer 2023, 128, 1196–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Y.-B.; Cai, Y. Faecal Microbiota Transplantation Enhances Efficacy of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors Therapy against Cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 27, 5362–5375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davar, D.; Dzutsev, A.K.; McCulloch, J.A.; Rodrigues, R.R.; Chauvin, J.-M.; Morrison, R.M.; Deblasio, R.N.; Menna, C.; Ding, Q.; Pagliano, O.; et al. Fecal Microbiota Transplant Overcomes Resistance to Anti-PD-1 Therapy in Melanoma Patients. Science 2021, 371, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopalakrishnan, V.; Helmink, B.A.; Spencer, C.N.; Reuben, A.; Wargo, J.A. The Influence of the Gut Microbiome on Cancer, Immunity, and Cancer Immunotherapy. Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 570–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duttagupta, S.; Messaoudene, M.; Jamal, R.; Mihalcioiu, C.; Marcoux, N.; Hunter, S.; Piccinno, G.; Puncochár, M.; Bélanger, K.; Tehfe, M.; et al. Abstract 2210: Microbiome Profiling Reveals That Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT) Modulates Response and Toxicity When Combined with Immunotherapy in Patients with Lung Cancer and Melanoma (FMT-LUMINate NCT04951583). Cancer Res. 2025, 85, 2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Qin, L.; Wu, X.; Li, D.; Qian, D.; Jiang, H.; Geng, Q. Faecal Microbiota Transplantation Combined with Platinum-Based Doublet Chemotherapy and Tislelizumab as First-Line Treatment for Driver-Gene Negative Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC): Study Protocol for a Prospective, Multicentre, Single-Arm Exploratory Trial. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e094366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groenewegen, B.; Terveer, E.M.; Joosse, A.; Barnhoorn, M.C.; Zwittink, R.D. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation for Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-Induced Colitis Is Safe and Contributes to Recovery: Two Case Reports. J. Immunother. 2023, 46, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, K.; Sakurai, T.; De Velasco, M.A.; Nagai, T.; Chikugo, T.; Ueshima, K.; Kura, Y.; Takahama, T.; Hayashi, H.; Nakagawa, K.; et al. Intestinal Microbiota and Gene Expression Reveal Similarity and Dissimilarity Between Immune-Mediated Colitis and Ulcerative Colitis. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 763468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, M.C.; Duong, C.P.M.; Gopalakrishnan, V.; Iebba, V.; Chen, W.-S.; Derosa, L.; Khan, M.A.W.; Cogdill, A.P.; White, M.G.; Wong, M.C.; et al. Gut Microbiota Signatures Are Associated with Toxicity to Combined CTLA-4 and PD-1 Blockade. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1432–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cascone, T.; William, W.N.; Weissferdt, A.; Leung, C.H.; Lin, H.Y.; Pataer, A.; Godoy, M.C.B.; Carter, B.W.; Federico, L.; Reuben, A.; et al. Neoadjuvant Nivolumab or Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab in Operable Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: The Phase 2 Randomized NEOSTAR Trial. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 504–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.-Y.; Seo, G.S. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation: Is It Safe? Clin. Endosc. 2021, 54, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, N.T. Probiotics. Am. J. Health-Syst. Pharm. 2010, 67, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Lu, Z.; Zhao, F.; Tang, S.; Zhang, L.; Feng, C. Assessing the Impact of Probiotics on Immunotherapy Effectiveness and Antibiotic-Mediated Resistance in Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1538969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomita, Y.; Ikeda, T.; Sakata, S.; Saruwatari, K.; Sato, R.; Iyama, S.; Jodai, T.; Akaike, K.; Ishizuka, S.; Saeki, S.; et al. Association of Probiotic Clostridium butyricum Therapy with Survival and Response to Immune Checkpoint Blockade in Patients with Lung Cancer. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2020, 8, 1236–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Gharaibeh, R.Z.; Newsome, R.C.; Pope, J.L.; Dougherty, M.W.; Tomkovich, S.; Pons, B.; Mirey, G.; Vignard, J.; Hendrixson, D.R.; et al. Campylobacter jejuni Promotes Colorectal Tumorigenesis through the Action of Cytolethal Distending Toxin. Gut 2019, 68, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.A.; Shaw, H.M.; Bataille, V.; Nathan, P.; Spector, T.D. Role of the Gut Microbiome for Cancer Patients Receiving Immunotherapy: Dietary and Treatment Implications. Eur. J. Cancer 2020, 138, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, M.F.; Ahmad, F.A.; Alsayegh, A.A.; Zeyaullah, M.; Babalghith, A.O.; Faidah, H.; Ahmed, F.; Khanam, A.; Mozaffar, B.; Kambal, N.; et al. Probiotics and Cancer: Mechanistic Insights and Organ-Specific Impact. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafson, M.P.; Wheatley-Guy, C.M.; Rosenthal, A.C.; Gastineau, D.A.; Katsanis, E.; Johnson, B.D.; Simpson, R.J. Exercise and the Immune System: Taking Steps to Improve Responses to Cancer Immunotherapy. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9, e001872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, S.; Rahmy, S.; Gan, D.; Liu, G.; Zhu, Y.; Manyak, M.; Duong, L.; He, J.; Schofield, J.H.; Schafer, Z.T.; et al. Ketogenic Diet Alters the Epigenetic and Immune Landscape of Prostate Cancer to Overcome Resistance to Immune Checkpoint Blockade Therapy. Cancer Res. 2024, 84, 1597–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batch, J.T.; Lamsal, S.P.; Adkins, M.; Sultan, S.; Ramirez, M.N. Advantages and Disadvantages of the Ketogenic Diet: A Review Article. Cureus 2020, 12, e9639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolte, L.A.; Lee, K.A.; Björk, J.R.; Leeming, E.R.; Campmans-Kuijpers, M.J.E.; De Haan, J.J.; Vila, A.V.; Maltez-Thomas, A.; Segata, N.; Board, R.; et al. Association of a Mediterranean Diet with Outcomes for Patients Treated with Immune Checkpoint Blockade for Advanced Melanoma. JAMA Oncol. 2023, 9, 705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, M.S.; Chang, E.B. The Microbiome: Composition and Locations. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2020, 176, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Papavassiliou, K.A.; Sofianidi, A.A.; Spiliopoulos, F.G.; Margoni, A.; Papavassiliou, A.G. Emerging Issues Regarding the Effects of the Microbiome on Lung Cancer Immunotherapy. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1525. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15111525

Papavassiliou KA, Sofianidi AA, Spiliopoulos FG, Margoni A, Papavassiliou AG. Emerging Issues Regarding the Effects of the Microbiome on Lung Cancer Immunotherapy. Biomolecules. 2025; 15(11):1525. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15111525

Chicago/Turabian StylePapavassiliou, Kostas A., Amalia A. Sofianidi, Fotios G. Spiliopoulos, Angeliki Margoni, and Athanasios G. Papavassiliou. 2025. "Emerging Issues Regarding the Effects of the Microbiome on Lung Cancer Immunotherapy" Biomolecules 15, no. 11: 1525. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15111525

APA StylePapavassiliou, K. A., Sofianidi, A. A., Spiliopoulos, F. G., Margoni, A., & Papavassiliou, A. G. (2025). Emerging Issues Regarding the Effects of the Microbiome on Lung Cancer Immunotherapy. Biomolecules, 15(11), 1525. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15111525