The Role of Imaging in Monitoring Large Vessel Vasculitis: A Comprehensive Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

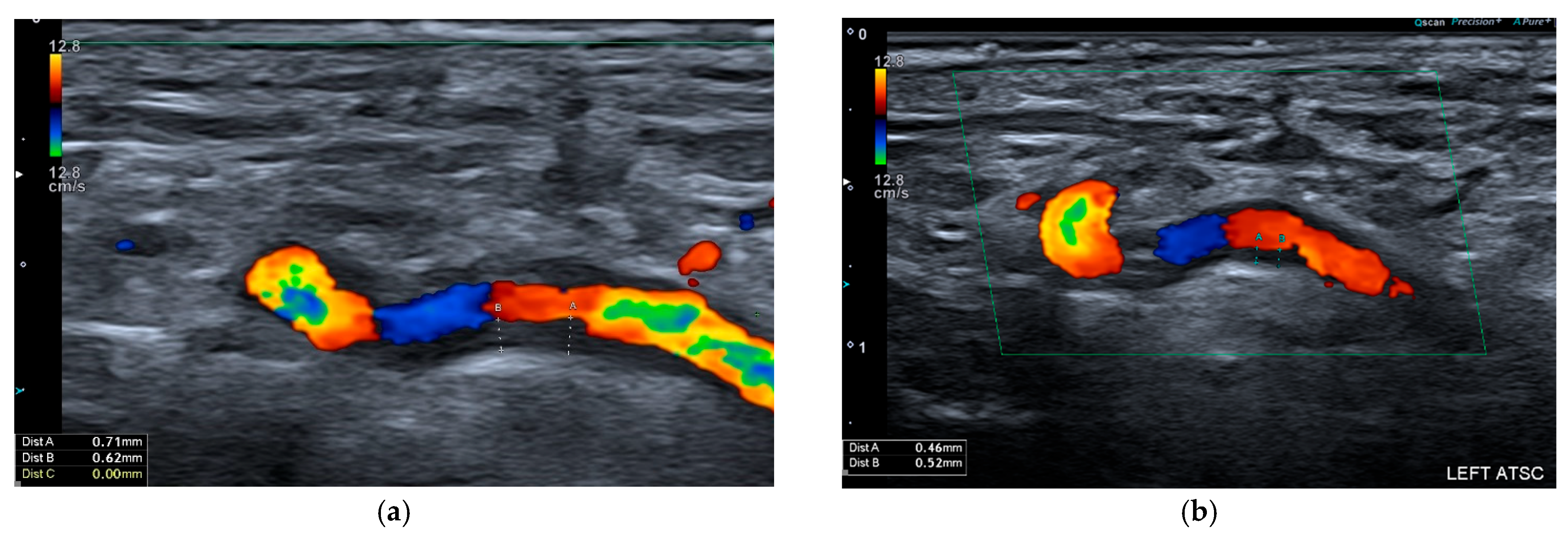

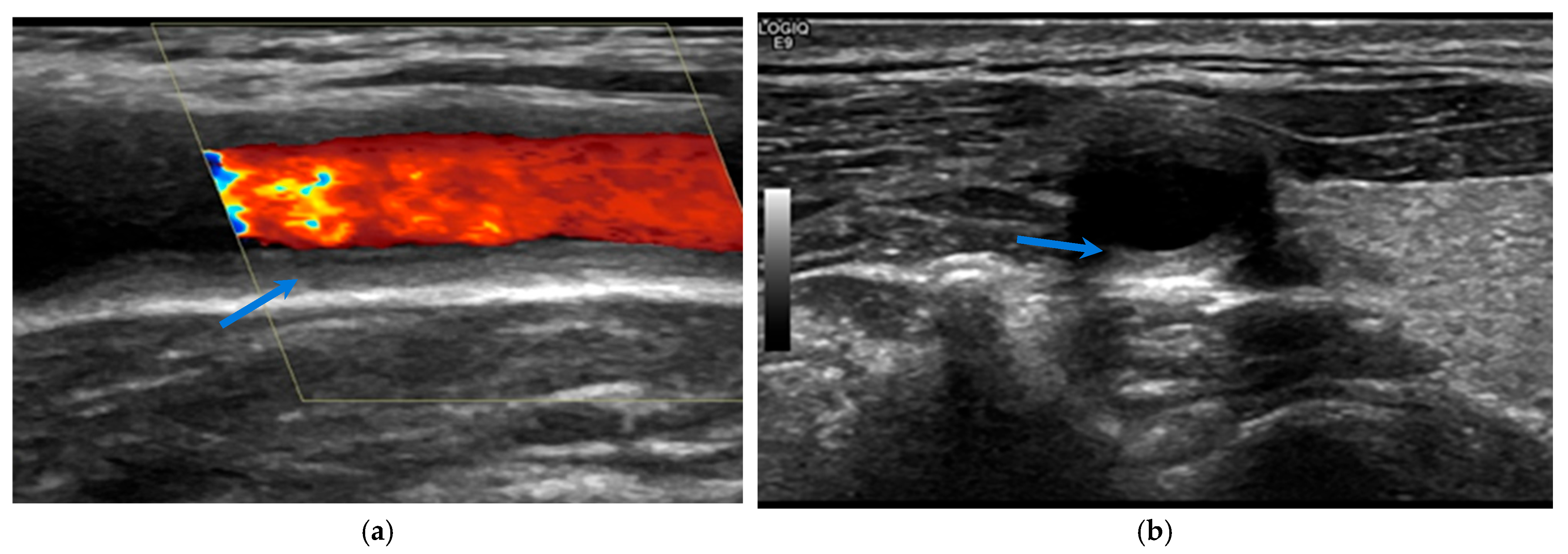

2. Ultrasound

2.1. Giant Cell Arteritis

2.2. Takayasu Arteritis

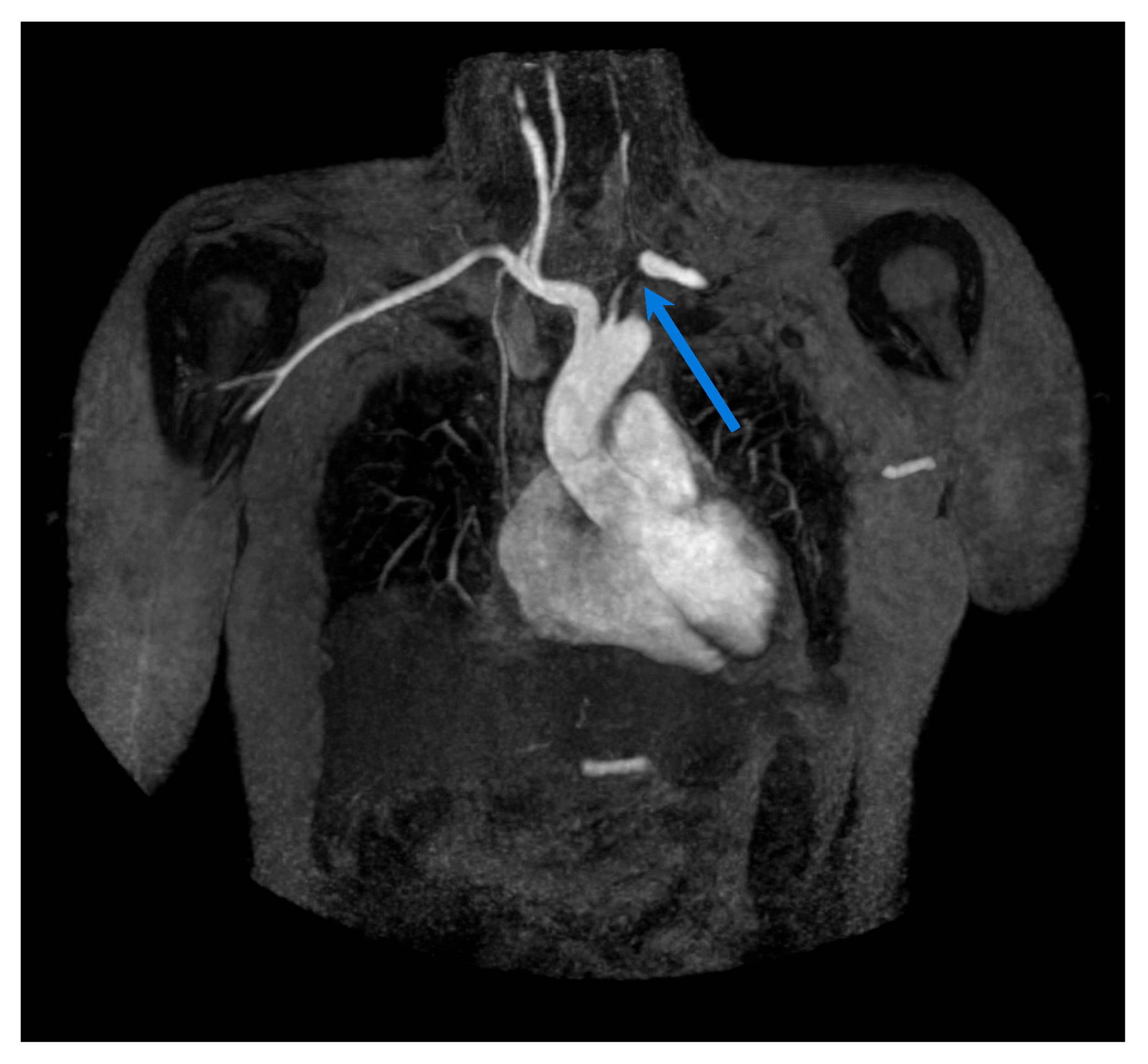

3. Magnetic Resonance Imaging

3.1. Giant Cell Arteritis

3.2. Takayasu Arteritis

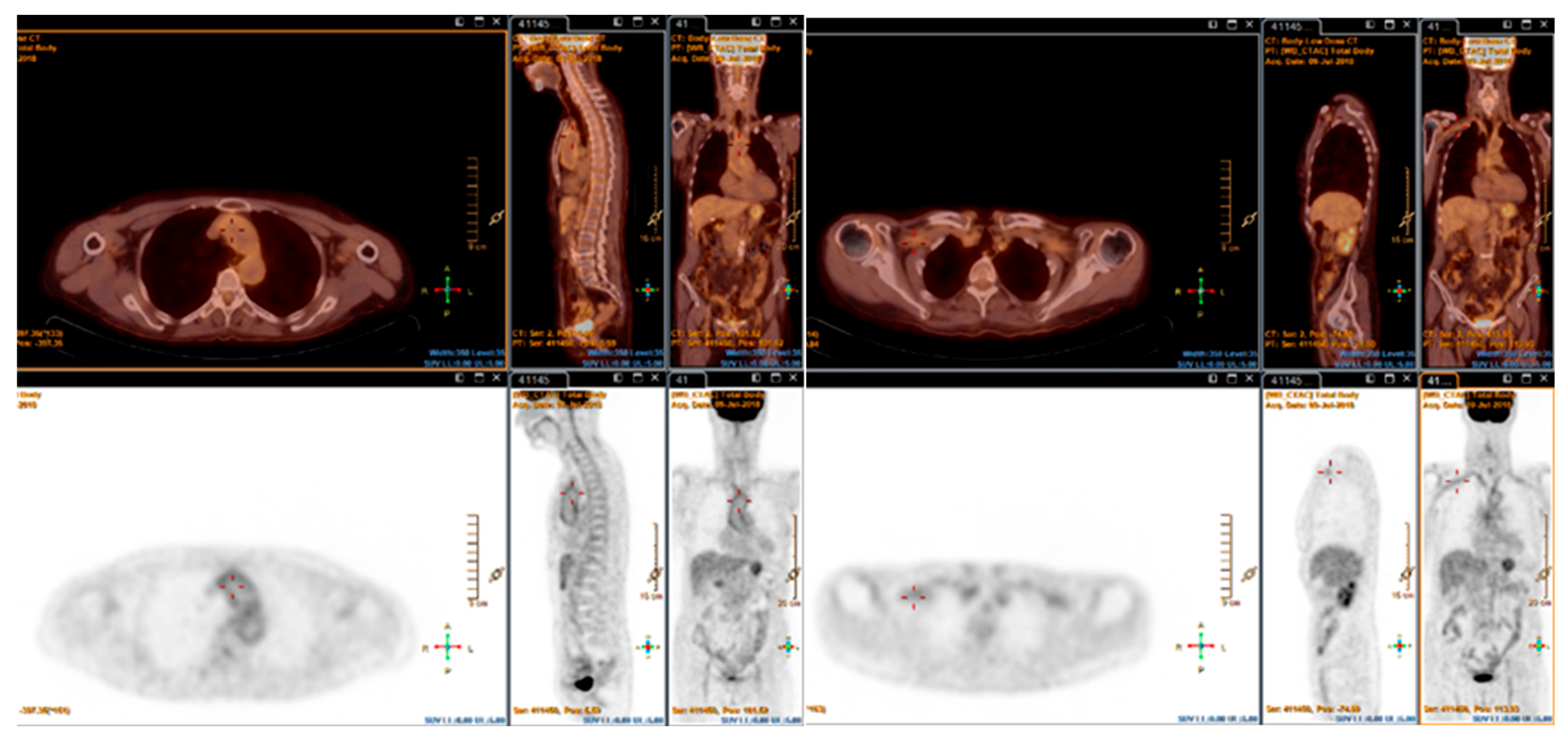

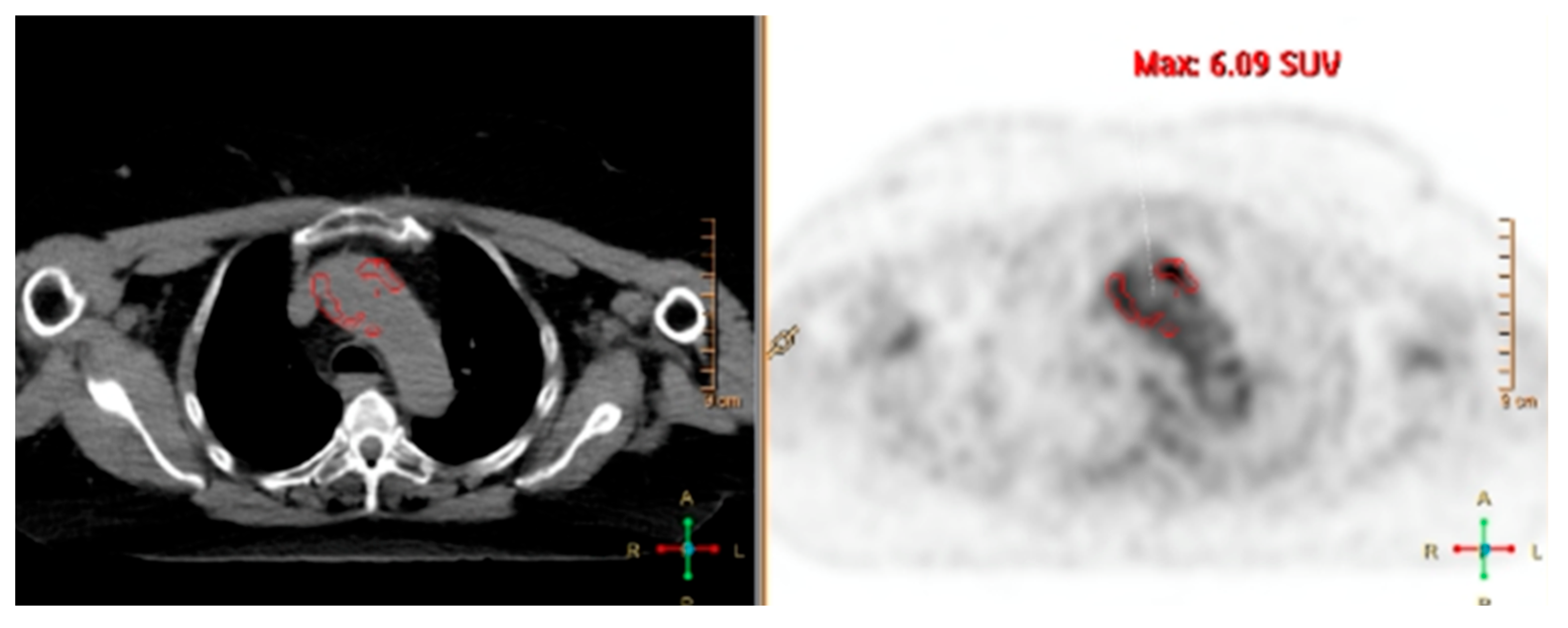

4. Fluorine-18-Fluorodeoxyglucose PET (FDG-PET)

4.1. Giant Cell Arteritis

4.2. Takayasu Arteritis

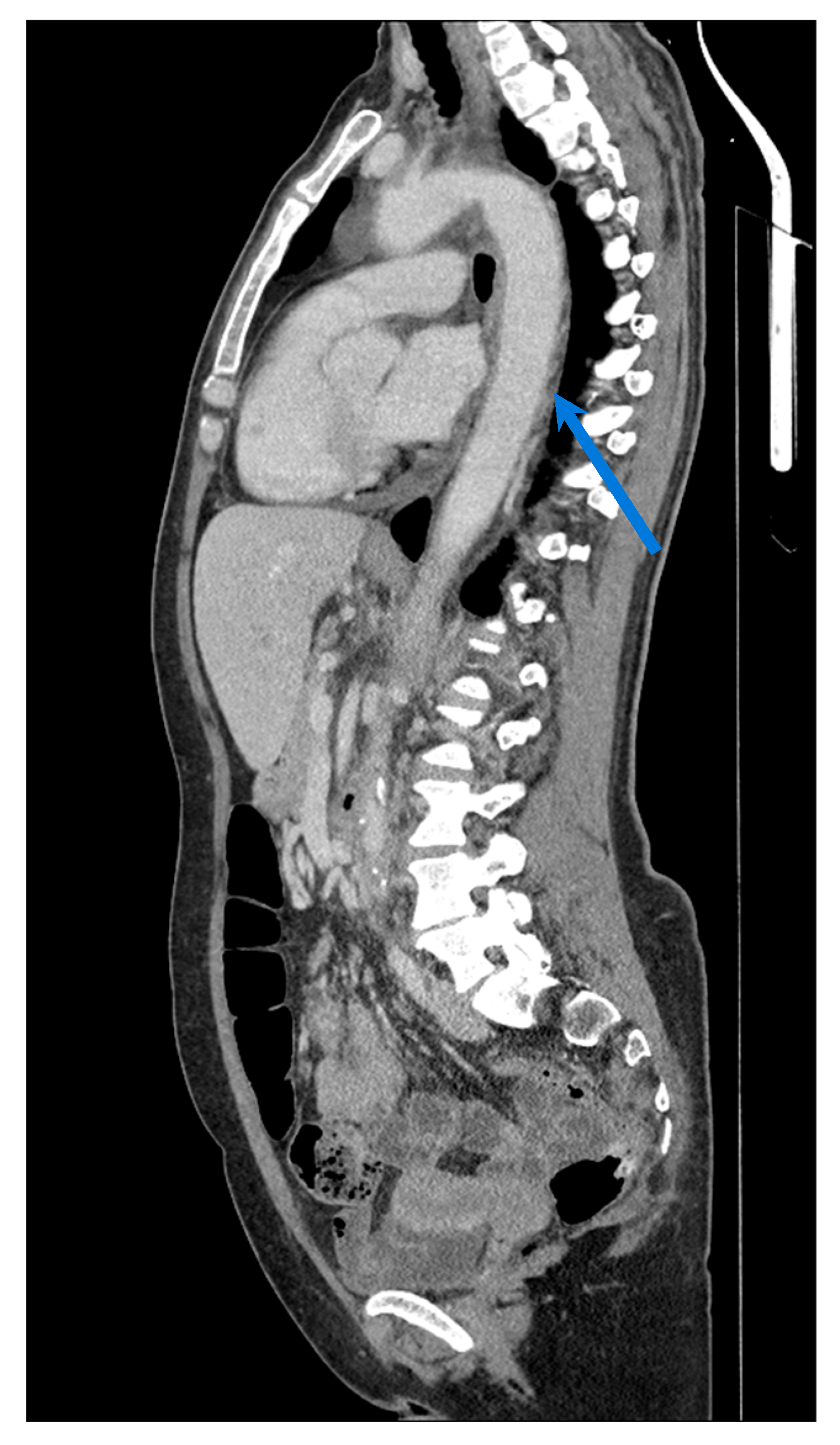

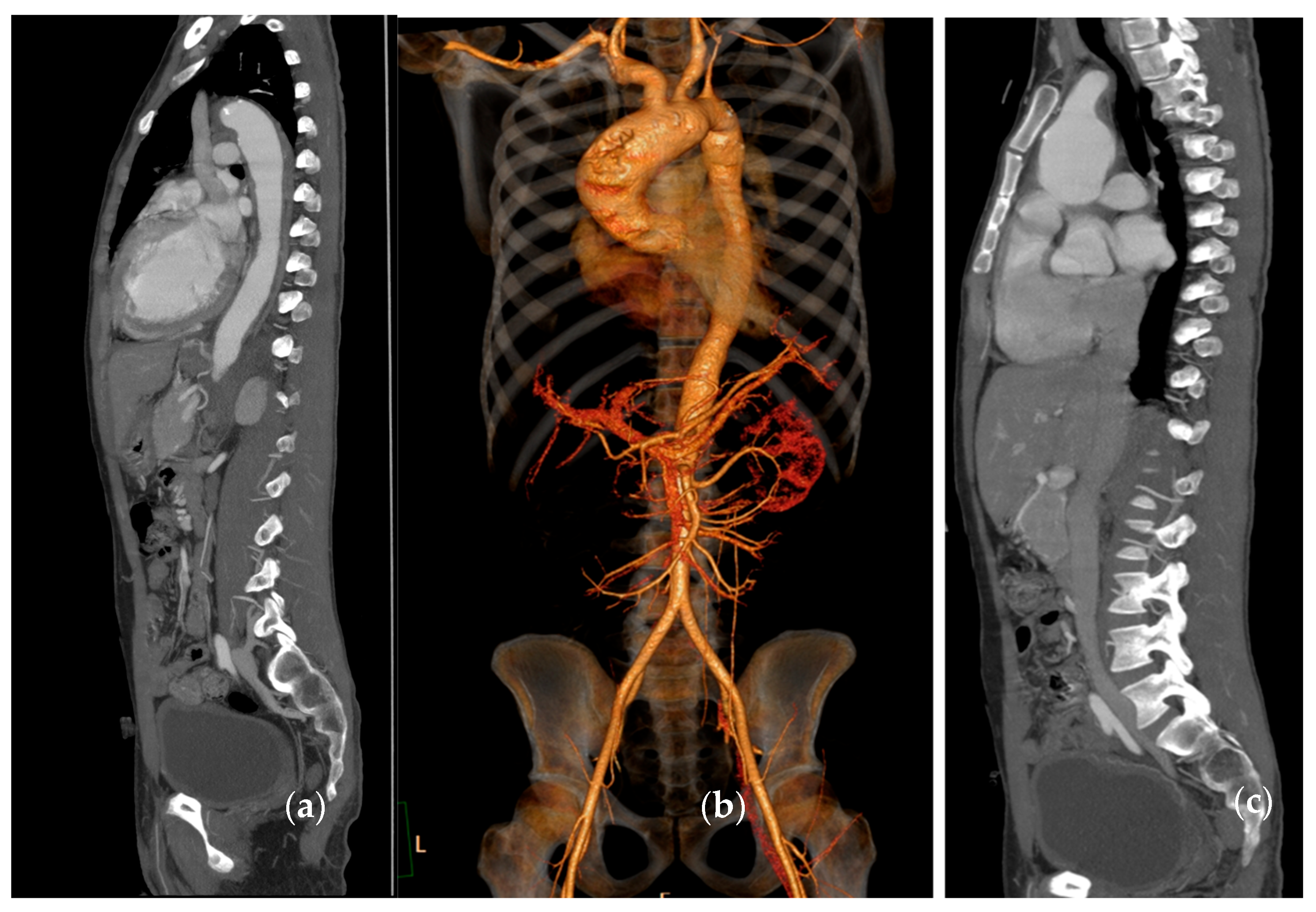

5. Computed Tomography (CT)/CT Angiography

5.1. Giant Cell Arteritis

5.2. Takayasu Arteritis

6. Conventional Angiography

6.1. Giant Cell Arteritis

6.2. Takayasu Arteritis

7. Multimodal Assessment

8. Future Perspectives

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AX | axillary artery |

| CA | Conventional angiography |

| CEUS | contrast-enhanced ultrasound |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| DEI.Tak | Disease Extent Index for Takayasu Arteritis |

| ESR | erythrocyte sedimentation rate |

| EULAR | European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology |

| FDG-PET | Fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography |

| GCA | Giant cell arteritis |

| IMT | intima-media thickness |

| ITAS-2010 | Indian Takayasu Clinical Activity Score |

| LV-GCA | Large vessel giant cell arteritis |

| LVV | large vessel vasculitide |

| MRA | magnetic resonance angiography |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| MRVAS | Magnetic Resonance Vasculitis Activity Score |

| OGUS | GCA Ultrasound Score OMERACT |

| PETVAS | PET vascular activity score |

| PGA | Physician Global Assessment |

| SUV | standardised uptake value |

| TA | temporal artery |

| TAIDAI | TAK Integrated Disease Activity Index |

| TAK | Takayasu arteritis |

| TBR | target-to-background ratio |

References

- Chrysidis, S.; Duftner, C.; Dejaco, C.; Schäfer, V.S.; Ramiro, S.; Carrara, G.; Scirè, C.A.; Hocevar, A.; Diamantopoulos, A.P.; Iagnocco, A.; et al. Definitions and reliability assessment of elementary ultrasound lesions in giant cell arteritis: A study from the OMERACT Large Vessel Vasculitis Ultrasound Working Group. RMD Open 2018, 4, e000598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, W.A.; Kraft, H.E.; Vorpahl, K.; Völker, L.; Gromnica-Ihle, E.J. Color Duplex Ultrasonography in the Diagnosis of Temporal Arteritis. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997, 337, 1336–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, H.; Handa, N.; Matsumoto, M.; Hougaku, H.; Ogawa, S.; Oku, N.; Itoh, T.; Moriwaki, H.; Yoneda, S.; Kimura, K.; et al. Carotid lesions detected by B-mode ultrasonography in Takayasu’s arteritis: “Macaroni sign” as an indicator of the disease. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 1991, 17, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Fernández, E.; Monjo-Henry, I.; Bonilla, G.; Plasencia, C.; Miranda-Carús, M.-E.; Balsa, A.; De Miguel, E. False positives in the ultrasound diagnosis of giant cell arteritis: Some diseases can also show the halo sign. Rheumatol. Oxf. Engl. 2020, 59, 2443–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argyropoulou, O.D.; Protogerou, A.D.; Sfikakis, P.P. Accelerated atheromatosis and arteriosclerosis in primary systemic vasculitides: Current evidence and future perspectives. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2018, 30, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitz, L.; Christ, L.; Lötscher, F.; Scholz, G.; Sarbu, A.-C.; Bütikofer, L.; Kollert, F.; A Schmidt, W.; Reichenbach, S.; Villiger, P.M. Quantitative ultrasound to monitor the vascular response to tocilizumab in giant cell arteritis. Rheumatol. Oxf. Engl. 2021, 60, 5052–5059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponte, C.; Serafim, A.S.; Monti, S.; Fernandes, E.; Lee, E.; Singh, S.; Piper, J.; Hutchings, A.; McNally, E.; Diamantopoulos, A.P.; et al. Early variation of ultrasound halo sign with treatment and relation with clinical features in patients with giant cell arteritis. Rheumatology 2020, 59, 3717–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastian, A.; Kayani, A.; Prieto-Pena, D.; Tomelleri, A.; Whitlock, M.; Mo, J.; van der Geest, N.; Dasgupta, B. Efficacy and safety of tocilizumab in giant cell arteritis: A single centre NHS experience using imaging (ultrasound and PET-CT) as a diagnostic and monitoring tool. RMD Open 2020, 6, e001417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J.A.; DiIorio, M.A.; Huang, W.; Sobiesczcyk, P.; Docken, W.P.; Tedeschi, S.K. Follow-up vascular ultrasounds in patients with giant cell arteritis. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2020, 38 (Suppl. S124), 107–111. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, B.D.; Therkildsen, P.; Keller, K.K.; Gormsen, L.C.; Hansen, I.T.; Hauge, E.M. Ultrasonography in the assessment of disease activity in cranial and large-vessel giant cell arteritis: A prospective follow-up study. Rheumatol. Oxf. Engl. 2023, 62, 3084–3094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haaversen, A.C.B.; Brekke, L.K.; Kermani, T.A.; Molberg, Ø.; Diamantopoulos, A.P. Vascular ultrasound as a follow-up tool in patients with giant cell arteritis: A prospective observational cohort study. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1436707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, V.S.; Dejaco, C.; Karakostas, P.; Behning, C.; Brossart, P.; Burg, L.C. Follow-up ultrasound examination in patients with newly diagnosed giant cell arteritis. Rheumatol. Oxf. Engl. 2025, 64, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponte, C.; Monti, S.; Scirè, C.A.; Delvino, P.; Khmelinskii, N.; Milanesi, A.; Teixeira, V.; Brandolino, F.; Saraiva, F.; Montecucco, C.; et al. Ultrasound halo sign as a potential monitoring tool for patients with giant cell arteritis: A prospective analysis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2021, 80, 1475–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, P.; Dejaco, C.; Schmidt, W.A.; Schlüter, K.D.; Pregartner, G.; Schäfer, V.S. Ultrasound for diagnosis and follow-up of chronic axillary vasculitis in patients with long-standing giant cell arteritis. Ther. Adv. Musculoskelet. Dis. 2021, 13, 1759720X21998505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejaco, C.; Ponte, C.; Monti, S.; Rozza, D.; Scirè, C.A.; Terslev, L.; Bruyn, G.A.W.; Boumans, D.; Hartung, W.; Hočevar, A.; et al. The provisional OMERACT ultrasonography score for giant cell arteritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2023, 82, 556–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina-Collada, J.; Monjo-Henry, I.; Fernández-Fernández, E.; Álvaro-Gracia, J.M.; de Miguel, E. The OMERACT giant cell arteritis ultrasonography score: A potential predictive outcome for assessing the risk of relapse during follow-up. Rheumatol. Oxf. Engl. 2025, 64, 1448–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monti, S.; Ponte, C.; Pereira, C.; Manzoni, F.; Klersy, C.; Rumi, F.; Carrara, G.; Hutchings, A.; A Schmidt, W.; Dasgupta, B.; et al. The impact of disease extent and severity detected by quantitative ultrasound analysis in the diagnosis and outcome of giant cell arteritis. Rheumatol. Oxf. Engl. 2020, 59, 2299–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dejaco, C.; Ramiro, S.; Bond, M.; Bosch, P.; Ponte, C.; Mackie, S.L.; A Bley, T.; Blockmans, D.; Brolin, S.; Bolek, E.C.; et al. EULAR recommendations for the use of imaging in large vessel vasculitis in clinical practice: 2023 update. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2023, 83, 741–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins-Martinho, J.; Sopa, I.; Ponte, C. The value of ultrasound for monitoring disease activity in giant cell arteritis. Vessel. Plus 2024, 8, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, S.Z.; Direskeneli, H.; Merkel, P.A. Assessment of Disease Activity in Large-vessel Vasculitis: Results of an International Delphi Exercise. J. Rheumatol. 2017, 44, 1928–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, P.; Bond, M.; Dejaco, C.; Ponte, C.; Mackie, S.L.; Falzon, L.; A Schmidt, W.; Ramiro, S. Imaging in diagnosis, monitoring and outcome prediction of large vessel vasculitis: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis informing the 2023 update of the EULAR recommendations. RMD Open 2023, 9, e003379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barra, L.; Kanji, T.; Malette, J.; Pagnoux, C. Imaging modalities for the diagnosis and disease activity assessment of Takayasu’s arteritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Autoimmun. Rev. 2018, 17, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Zhu, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, W.; Li, C. Ultrasound morphological changes in the carotid wall of Takayasu’s arteritis: Monitor of disease progression. Int. Angiol. J. Int. Union Angiol. 2016, 35, 586–592. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.H.; Chung, J.W.; Lee, J.W.; Han, M.H.; Park, J.H. Carotid artery involvement in Takayasu’s arteritis: Evaluation of the activity by ultrasonography. J. Ultrasound Med. 2001, 20, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.C.; Lee, S.W.; Park, Y.B.; Chung, N.S.; Lee, S.K. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of Takayasu’s arteritis: Analysis of 108 patients using standardized criteria for diagnosis, activity assessment, and angiographic classification. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2005, 34, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.-Y.; Li, C.-L.; Ma, L.-L.; Cui, X.-M.; Dai, X.-M.; Sun, Y.; Chen, H.-Y.; Huang, B.-J.; Jiang, L.-D. Value of contrast-enhanced ultrasonography of the carotid artery for evaluating disease activity in Takayasu arteritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2019, 21, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tian, X.; Li, J.; Yang, Y.; Ge, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zou, M.; Wang, H.; et al. Ultrasonography and contrast-enhanced ultrasound for activity assessment in 115 patients with carotid involvement of Takayasu arteritis. Mod. Rheumatol. 2023, 33, 1007–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svensson, C.; Eriksson, P.; Zachrisson, H. Vascular ultrasound for monitoring of inflammatory activity in Takayasu arteritis. Clin. Physiol. Funct. Imaging 2020, 40, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordana, P.; Baqué-Juston, M.C.; Jeandel, P.Y.; Mondot, L.; Hirlemann, J.; Padovani, B.; Raffaelli, C. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound of carotid artery wall in Takayasu disease: First evidence of application in diagnosis and monitoring of response to treatment. Circulation 2011, 124, 245–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnoni, M.; Dagna, L.; Coli, S.; Cianflone, D.; Sabbadini, M.G.; Maseri, A. Assessment of Takayasu arteritis activity by carotid contrast-enhanced ultrasound. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2011, 4, e1–e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Possemato, N.; Macchioni, P.; Germanò, G.; Pipitone, N.; Versari, A.; Salvarani, C. Clinical images: PET-CT and contrast-enhanced ultrasound in Takayasu’s arteritis. Rheumatology 2014, 53, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Herlin, B.; Baud, J.M.; Chadenat, M.L.; Pico, F. Contrast-enhanced ultrasonography in Takayasu arteritis: Watching and monitoring the arterial inflammation. BMJ Case Rep. 2015, 2015, bcr2015211094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schinkel, A.F.; Oord, S.C.v.D.; van der Steen, A.F.; van Laar, J.A.; Sijbrands, E.J. Utility of contrast-enhanced ultrasound for the assessment of the carotid artery wall in patients with Takayasu or giant cell arteritis. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2014, 15, 541–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germanò, G.; Macchioni, P.; Possemato, N.; Boiardi, L.; Nicolini, A.; Casali, M.; Versari, A.; Pipitone, N.; Salvarani, C. Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound of the Carotid Artery in Patients With Large Vessel Vasculitis: Correlation with Positron Emission Tomography Findings: CEUS of the Carotid Artery in LVV. Arthritis Care Res. 2017, 69, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.H.; Tian, X.P.; Wang, H.-Y.; Li, J.; Ge, Z.-T.; Yang, Y.-J.; Cai, S.; Zeng, X.-F.; Li, J.-C. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound for evaluating arteritis activity in Takayasu arteritis patients. Clin. Rheumatol. 2020, 39, 1229–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goudot, G.; Jimenez, A.; Mohamedi, N.; Sitruk, J.; Khider, L.; Mortelette, H.; Papadacci, C.; Hyafil, F.; Tanter, M.; Messas, E.; et al. Assessment of Takayasu’s arteritis activity by ultrasound localization microscopy. EBioMedicine 2023, 90, 104502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guggenberger, K.; Bley, T. Imaging in Large Vessel Vasculitides. Rofo-Fortschritte Auf Dem Geb. Rontgenstrahlen Bild. Verfahr. 2019, 191, 1083–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavrogeni, S.; Dimitroulas, T.; Chatziioannou, S.N.; Kitas, G. The role of multimodality imaging in the evaluation of Takayasu arteritis. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2013, 42, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oura, K.; Yamaguchi Oura, M.; Itabashi, R.; Maeda, T. Vascular Imaging Techniques to Diagnose and Monitor Patients with Takayasu Arteritis: A Review of the Literature. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, V.S.; Jin, L.; Schmidt, W.A. Imaging for Diagnosis, Monitoring, and Outcome Prediction of Large Vessel Vasculitides. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2020, 22, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meller, J.; Strutz, F.; Siefker, U.; Scheel, A.; Sahlmann, C.O.; Lehmann, K.; Conrad, M.; Vosshenrich, R. Early diagnosis and follow-up of aortitis with [(18)F]FDG PET and MRI. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2003, 30, 730–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichenbach, S.; Adler, S.; Bonel, H.; Cullmann, J.L.; Kuchen, S.; Bütikofer, L.; Seitz, M.; Villiger, P.M. Magnetic resonance angiography in giant cell arteritis: Results of a randomized controlled trial of tocilizumab in giant cell arteritis. Rheumatology 2018, 57, 982–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Both, M.; Ahmadi-Simab, K.; Reuter, M.; Dourvos, O.; Fritzer, E.; Ullrich, S.; Gross, W.L.; Heller, M.; Bã¤Hre, M. MRI and FDG-PET in the assessment of inflammatory aortic arch syndrome in complicated courses of giant cell arteritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2008, 67, 1030–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, S.; Sprecher, M.; Wermelinger, F.; Klink, T.; Bonel, H.; Villiger, P.M. Diagnostic value of contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance angiography in large-vessel vasculitis. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2017, 147, w14397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheel, A.K. Diagnosis and follow up of aortitis in the elderly. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2004, 63, 1507–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siemonsen, S.; Brekenfeld, C.; Holst, B.; Kaufmann-Buehler, A.K.; Fiehler, J.; Bley, T.A. 3T MRI reveals extra- and intracranial involvement in giant cell arteritis. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2015, 36, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bley, T.A.; Weiben, O.; Uhl, M.; Vaith, P.; Schmidt, D.; Warnatz, K.; Langer, M. Assessment of the cranial involvement pattern of giant cell arteritis with 3T magnetic resonance imaging. Arthritis Rheum. 2005, 52, 2470–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poillon, G.; Collin, A.; Benhamou, Y.; Clavel, G.; Savatovsky, J.; Pinson, C.; Zuber, K.; Charbonneau, F.; Vignal, C.; Picard, H.; et al. Increased diagnostic accuracy of giant cell arteritis using three-dimensional fat-saturated contrast-enhanced vessel-wall magnetic resonance imaging at 3 T. Eur. Radiol. 2020, 30, 1866–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhee, R.L.; Rebello, R.; Tamhankar, M.A.; Banerjee, S.; Liu, F.; Cao, Q.; Kurtz, R.; Baker, J.F.; Fan, Z.; Bhatt, V.; et al. Combined Orbital and Cranial Vessel Wall Magnetic Resonance Imaging for the Assessment of Disease Activity in Giant Cell Arteritis. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2024, 6, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froehlich, M.; Guggenberger, K.V.; Vogt, M.; Mihatsch, P.W.; Torre, G.D.; A Werner, R.; Gernert, M.; Strunz, P.P.; Portegys, J.; Weng, A.M.; et al. MRVAS-introducing a standardized magnetic resonance scoring system for assessing the extent of inflammatory burden in giant cell arteritis. Rheumatol. Oxf. Engl. 2024, 63, 2781–2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, K.A.; Ahlman, M.A.; Malayeri, A.A.; Marko, J.; Civelek, A.C.; Rosenblum, J.S.; A Bagheri, A.; A Merkel, P.; Novakovich, E.; Grayson, P.C. Comparison of magnetic resonance angiography and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in large-vessel vasculitis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2018, 77, 1165–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christ, L.; Bonel, H.M.; Cullmann, J.L.; Seitz, L.; Bütikofer, L.; Wagner, F.; Villiger, P.M. Magnetic resonance imaging to monitor disease activity in giant cell arteritis treated with ultra-short glucocorticoids and tocilizumab. Rheumatol. Oxf. Engl. 2025, 64, 2059–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, I.; Nakagawa, T.; Himeno, Y.; Kobayashi, Y.; Numano, F.; Shibuya, H. Takayasu arteritis: Diagnosis with breath-hold contrast-enhanced three-dimensional MR angiography. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging JMRI 2000, 11, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, Y.H.; Han, B.K.; Koh, E.M.; Kim, D.K.; Do, Y.S.; Lee, W.R. Takayasu’s arteritis: Assessment of disease activity with contrast-enhanced MR imaging. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2000, 175, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tso, E.; Flamm, S.D.; White, R.D.; Schvartzman, P.R.; Mascha, E.; Hoffman, G.S. Takayasu arteritis: Utility and limitations of magnetic resonance imaging in diagnosis and treatment. Arthritis Rheum. 2002, 46, 1634–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshet, Y.; Pauzner, R.; Goitein, O.; Langevitz, P.; Eshed, I.; Hoffmann, C.; Konen, E. The limited role of MRI in long-term follow-up of patients with Takayasu’s arteritis. Autoimmun. Rev. 2011, 11, 132–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Huang, Q.; Jiang, L. Radiology and biomarkers in assessing disease activity in Takayasu arteritis. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2018, 22 (Suppl. S1), 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; Li, D.; Yan, F.; Dai, X.; Li, Y.; Ma, L. Evaluation of Takayasu arteritis activity by delayed contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Int. J. Cardiol. 2012, 155, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tombetti, E.; Godi, C.; Ambrosi, A.; Doyle, F.; Jacobs, A.; Kiprianos, A.P.; Youngstein, T.; Bechman, K.; Manfredi, A.A.; Ariff, B.; et al. Novel Angiographic Scores for evaluation of Large Vessel Vasculitis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 15979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhocine, T.; Blockmans, D.; Hustinx, R.; Vandevivere, J.; Mortelmans, L. Imaging of large vessel vasculitis with 18FDG PET: Illusion or reality? A critical review of the literature data. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2003, 30, 1305–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, H.; Kubota, K.; Mimori, A. Clinical value of whole-body PET/CT in patients with active rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2014, 16, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blockmans, D.; de Ceuninck, L.; Vanderschueren, S.; Knockaert, D.; Mortelmans, L.; Bobbaers, H. Repetitive 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in giant cell arteritis: A prospective study of 35 patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2006, 55, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, E.; Muratore, F.; Mancuso, P.; Boiardi, L.; Marvisi, C.; Besutti, G.; Spaggiari, L.; Casali, M.; Versari, A.; Rossi, P.G.; et al. The role of PET/CT in disease activity assessment in patients with large vessel vasculitis. Rheumatol. Oxf. Engl. 2022, 61, 4809–4816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slart, R.H.J.A.; Writing Group; Reviewer Group; Members of EANM Cardiovascular; Members of EANM Infection & Inflammation; Members of Committees; SNMMI Cardiovascular; Members of Council; PET Interest Group; Members of ASNC & EANM Committee Coordinator. FDG-PET/CT(A) imaging in large vessel vasculitis and polymyalgia rheumatica: Joint procedural recommendation of the EANM, SNMMI, and the PET Interest Group (PIG), and endorsed by the ASNC. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2018, 45, 1250–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Geest, K.S.M.; Gheysens, O.; Gormsen, L.C.; Glaudemans, A.W.; Tsoumpas, C.; Brouwer, E.; Nienhuis, P.H.; van Praagh, G.D.; Slart, R.H. Advances in PET Imaging of Large Vessel Vasculitis: An Update and Future Trends. Semin. Nucl. Med. 2024, 54, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashora, H.R.; Rosenblum, J.S.; Quinn, K.A.; Alessi, H.; Novakovich, E.; Saboury, B.; Ahlman, M.A.; Grayson, P.C. Comparing Semiquantitative and Qualitative Methods of Vascular 18F-FDG PET Activity Measurement in Large-Vessel Vasculitis. J. Nucl. Med. Off. Publ. Soc. Nucl. Med. 2022, 63, 280–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammel, A.M.; Hsiao, E.; Schembri, G.; Nguyen, K.; Brewer, J.; Schrieber, L.; Janssen, B.; Youssef, P.; Fraser, C.L.; Bailey, E.; et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography of the Head, Neck, and Chest for Giant Cell Arteritis: A Prospective, Double-Blind, Cross-Sectional Study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019, 71, 1319–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nienhuis, P.H.; Sandovici, M.; Glaudemans, A.W.; Slart, R.H.; Brouwer, E. Visual and semiquantitative assessment of cranial artery inflammation with FDG-PET/CT in giant cell arteritis. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2020, 50, 616–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Geest, K.S.M.; Treglia, G.; Glaudemans, A.W.J.M.; Brouwer, E.; Sandovici, M.; Jamar, F.; Gheysens, O.; A Slart, R.H.J. Diagnostic value of [18F]FDG-PET/CT for treatment monitoring in large vessel vasculitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2021, 48, 3886–3902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grayson, P.C.; Alehashemi, S.; Bs, A.A.B.; Civelek, A.C.; Cupps, T.R.; Kaplan, M.J.; Malayeri, A.A.; Merkel, P.A.; Novakovich, E.; Bluemke, D.A.; et al. 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose-Positron Emission Tomography as an Imaging Biomarker in a Prospective, Longitudinal Cohort of Patients with Large Vessel Vasculitis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018, 70, 439–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sammel, A.M.; Hsiao, E.; Schembri, G.; Bailey, E.; Nguyen, K.; Brewer, J.; Schrieber, L.; Janssen, B.; Youssef, P.; Fraser, C.L.; et al. Cranial and large vessel activity on positron emission tomography scan at diagnosis and 6 months in giant cell arteritis. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2020, 23, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, B.D.; Gormsen, L.C.; Hansen, I.T.; Keller, K.K.; Therkildsen, P.; Hauge, E.M. Three days of high-dose glucocorticoid treatment attenuates large-vessel 18F-FDG uptake in large-vessel giant cell arteritis but with a limited impact on diagnostic accuracy. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2018, 45, 1119–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, K.A.; Dashora, H.; Novakovich, E.; Ahlman, M.A.; Grayson, P.C. Use of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography to monitor tocilizumab effect on vascular inflammation in giant cell arteritis. Rheumatol. Oxf. Engl. 2021, 60, 4384–4389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Rodríguez, I.; Jiménez-Alonso, M.; Quirce, R.; Jiménez-Bonilla, J.; Martínez-Amador, N.; De Arcocha-Torres, M.; Loricera, J.; Blanco, R.; González-Gay, M.Á.; Banzo, I. 18F-FDG PET/CT in the follow-up of large-vessel vasculitis: A study of 37 consecutive patients. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2018, 47, 530–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prieto Peña, D.; Martínez-Rodríguez, I.; Atienza-Mateo, B.; Calderón-Goercke, M.; Banzo, I.; González-Vela, M.C.; Castañeda, S.; Llorca, J.; González-Gay, M.Á.; Blanco, R. Evidence for uncoupling of clinical and 18-FDG activity of PET/CT scan improvement in tocilizumab-treated patients with large-vessel giant cell arteritis. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2021, 39 (Suppl. S129), 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönau, V.; Roth, J.; Tascilar, K.; Corte, G.; Manger, B.; Rech, J.; Schmidt, D.; Cavallaro, A.; Uder, M.; Crescentini, F.; et al. Resolution of vascular inflammation in patients with new-onset giant cell arteritis: Data from the RIGA study. Rheumatol. Oxf. Engl. 2021, 60, 3851–3861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertagna, F.; Bosio, G.; Caobelli, F.; Motta, F.; Biasiotto, G.; Giubbini, R. Role of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography for therapy evaluation of patients with large-vessel vasculitis. Jpn. J. Radiol. 2010, 28, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Leeuw, K.; Bijl, M.; Jager, P.L. Additional value of positron emission tomography in diagnosis and follow-up of patients with large vessel vasculitides. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2004, 22 (Suppl. S36), S21–S26. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, M.A.; Melzer, R.A.; Schindler, C.; Müller-Brand, J.; Tyndall, A.; Nitzsche, E.U. The value of [18F]FDG-PET in the diagnosis of large-vessel vasculitis and the assessment of activity and extent of disease. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2005, 32, 674–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fröhlich, M.; Schmalzing, M.; Buck, A.; Bley, T.A.; Guggenberger, K.V.; Werner, R.A. PET-Derived Increased Inflammation in Large Vessels is linked to Relapse-Free Survival in Patients with Giant Cell Arteritis. Nukl. Nucl. Med. 2023, 62, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellavedova, L.; Carletto, M.; Faggioli, P.; Sciascera, A.; Del Sole, A.; Mazzone, A.; Maffioli, L.S. The prognostic value of baseline 18F-FDG PET/CT in steroid-naïve large-vessel vasculitis: Introduction of volume-based parameters. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2016, 43, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreel, L.; Coudyzer, W.; Boeckxstaens, L.; Betrains, A.; Molenberghs, G.; Vanderschueren, S.; Claus, E.; Van Laere, K.; Blockmans, D. Association Between Vascular 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose Uptake at Diagnosis and Change in Aortic Dimensions in Giant Cell Arteritis: A Cohort Study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2023, 176, 1321–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Boysson, H.; Liozon, E.; Lambert, M.; Parienti, J.-J.; Artigues, N.; Geffray, L.; Boutemy, J.; Ollivier, Y.; Maigné, G.; Ly, K.; et al. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography and the risk of subsequent aortic complications in giant-cell arteritis: A multicenter cohort of 130 patients. Medicine 2016, 95, e3851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maleszewski, J.J.; Younge, B.R.; Fritzlen, J.T.; Hunder, G.G.; Goronzy, J.J.; Warrington, K.J.; Weyand, C.M. Clinical and pathological evolution of giant cell arteritis: A prospective study of follow-up temporal artery biopsies in 40 treated patients. Mod. Pathol. Off. J. U. S. Can. Acad. Pathol. Inc. 2017, 30, 788–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soussan, M.; Nicolas, P.; Schramm, C.; Katsahian, S.; Pop, G.; Fain, O.; Mekinian, A. Management of large-vessel vasculitis with FDG-PET: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2015, 94, e622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schramm, N.; Ingenhoff, J.; Dechant, C.; Treitl, K.; Treitl, M.; Proft, F.; Schulze-Koops, H.; Hoffmann, U.; Bartenstein, P.; Rominger, A.; et al. Diagnostic accuracy of positron emission tomography for assessment of disease activity in large vessel vasculitis. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2019, 22, 1371–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lensen, K.D.F.; Comans, E.F.I.; Voskuyl, A.E.; van der Laken, C.J.; Brouwer, E.; Zwijnenburg, A.T.; Arias-Bouda, L.M.P.; Glaudemans, A.W.J.M.; Slart, R.H.J.A.; Smulders, Y.M. Large-vessel vasculitis: Interobserver agreement and diagnostic accuracy of 18F-FDG-PET/CT. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 914692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Haim, S.; Kupzov, E.; Tamir, A.; Israel, O. Evaluation of 18F-FDG uptake and arterial wall calcifications using 18F-FDG PET/CT. J. Nucl. Med. Off. Publ. Soc. Nucl. Med. 2004, 45, 1816–1821. [Google Scholar]

- Marvisi, C.; Bolek, E.C.; Ahlman, M.A.; Alessi, H.; Redmond, C.; Muratore, F.; Galli, E.; Ricordi, C.; Kaymaz-Tahra, S.; Ozguven, S.; et al. Development of the Takayasu Arteritis Integrated Disease Activity Index. Arthritis Care Res. 2024, 76, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karapolat, I.; Kalfa, M.; Keser, G.; Yalçin, M.; Inal, V.; Kumanlioğlu, K.; Pirildar, T.; Aksu, K. Comparison of F18-FDG PET/CT findings with current clinical disease status in patients with Takayasu’s arteritis. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2013, 31 (Suppl. S75), S15–S21. [Google Scholar]

- Misra, R.; Danda, D.; Rajappa, S.M.; Ghosh, A.; Gupta, R.; Mahendranath, K.M.; Jeyaseelan, L.; Lawrence, A.; Bacon, P.A. Development and initial validation of the Indian Takayasu Clinical Activity Score (ITAS2010). Rheumatol. Oxf. Engl. 2013, 52, 1795–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivakumar, M.R.; Misra, R.N.; Bacon, P.A. Op14. The Indian perspective of Takayasu arteritis and development of a Disease Extent Index (DEI. Tak) to assess Takayasu arteritis. Rheumatology 2005, 44 (Suppl. S3), iii6–iii7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lee, K.H.; Cho, A.; Choi, Y.J.; Lee, S.; Ha, Y.; Jung, S.; Park, M.; Lee, J.; Lee, S.; Park, Y. The role of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography in the assessment of disease activity in patients with takayasu arteritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2012, 64, 866–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, F.; Han, Q.; Zhou, X.; Zheng, Z.; Wang, S.; Ma, W.; Zhang, K.; Quan, Z.; Yang, W.; Wang, J.; et al. Performance of the PET vascular activity score (PETVAS) for qualitative and quantitative assessment of inflammatory activity in Takayasu’s arteritis patients. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2020, 47, 3107–3117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, J.; Sun, Y.; Shi, H.; Ji, Z.; Jiang, L. 18F-FDG-PET/CT: An accurate method to assess the activity of Takayasu’s arteritis. Clin. Rheumatol. 2018, 37, 1927–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaud, L.; Haroche, J.; Malek, Z.; Archambaud, F.; Gambotti, L.; Grimon, G.; Kas, A.; Costedoat-Chalumeau, N.; Cacoub, P.; Toledano, D.; et al. Is 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography scanning a reliable way to assess disease activity in Takayasu arteritis? Arthritis Rheum. 2009, 60, 1193–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahra, S.K.; Özgüven, S.; Ünal, A.U.; Öner, F.A.; Öneş, T.; Erdil, T.Y.; Direskeneli, R.H. Assessment of Takayasu arteritis in routine practice with PETVAS, an 18F-FDG PET quantitative scoring tool. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 52, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, Y.; Ishii, K.; Oda, K.; Nariai, T.; Tanaka, Y.; Ishiwata, K.; Numano, F. Aortic wall inflammation due to Takayasu arteritis imaged with 18F-FDG PET coregistered with enhanced CT. J. Nucl. Med. Off. Publ. Soc. Nucl. Med. 2005, 46, 917–922. [Google Scholar]

- Tezuka, D.; Haraguchi, G.; Ishihara, T.; Ohigashi, H.; Inagaki, H.; Suzuki, J.-I.; Hirao, K.; Isobe, M. Role of FDG PET-CT in Takayasu arteritis: Sensitive detection of recurrences. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2012, 5, 422–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhosh, S.; Mittal, B.R.; Gayana, S.; Bhattacharya, A.; Sharma, A.; Jain, S. F-18 FDG PET/CT in the evaluation of Takayasu arteritis: An experience from the tropics. J. Nucl. Cardiol. Off. Publ. Am. Soc. Nucl. Cardiol. 2014, 21, 993–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, J.; Al-Nahhas, A.; Pennell, D.J.; Hossain, M.S.; A Davies, K.; O Haskard, D.; Mason, J.C. Non-invasive imaging in the diagnosis and management of Takayasu’s arteritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2004, 63, 995–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campochiaro, C.; Tomelleri, A.; Sartorelli, S.; Sembenini, C.; Papa, M.; Fallanca, F.; Picchio, M.; Cavalli, G.; De Cobelli, F.; Baldissera, E.; et al. A Prospective Observational Study on the Efficacy and Safety of Infliximab-Biosimilar (CT-P13) in Patients With Takayasu Arteritis (TAKASIM). Front. Med. 2021, 8, 723506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, K.A.; Ahlman, M.A.; Alessi, H.D.; LaValley, M.P.; Neogi, T.; Marko, J.; Novakovich, E.; Grayson, P.C. Association of 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose-Positron Emission Tomography Activity with Angiographic Progression of Disease in Large Vessel Vasculitis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2023, 75, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röhrich, M.; Rosales, J.J.; Hoppner, J.; Kvacskay, P.; Blank, N.; Loi, L.; Paech, D.; Schreckenberger, M.; Giesel, F.; Kauczor, H.U.; et al. Fibroblast activation protein inhibitor-positron emission tomography in aortitis: Fibroblast pathology in active inflammation and remission. Rheumatol. Oxf. Engl. 2024, 63, 2473–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.A.; Srivastava, M.K.; Sree lekha, K.; Madhuri, C.; Kumar, P. Intracranial and Extracranial Vascular Involvement in Takayasu Arteritis Unresponsive to Multiple Lines of Immunomodulation on 68Ga-FAPI PET/CT: A Game Changer. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, K.; Chen, H.; Hou, P.; Cheng, L.; Guo, W.; Li, Y.; Lv, J.; Ke, M.; Wu, X.; Lei, Y.; et al. Comparison of [18F]FAPI-42 and [18F]FDG PET/CT in the evaluation of systemic vasculitis. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2025, 52, 1083–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peverelli, M.; Tarkin, J.M. Emerging PET radiotracers for vascular imaging. Rheumatol. Oxf. Engl. 2025, 64 (Suppl. S1), i33–i37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto-González, S.; Arguis, P.; García-Martínez, A.; Espígol-Frigolé, G.; Tavera-Bahillo, I.; Butjosa, M.; Sánchez, M.; Hernández-Rodríguez, J.; Grau, J.M.; Cid, M.C. Large vessel involvement in biopsy-proven giant cell arteritis: Prospective study in 40 newly diagnosed patients using CT angiography. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2012, 71, 1170–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto-González, S.; García-Martínez, A.; Tavera-Bahillo, I.; Hernández-Rodríguez, J.; Gutiérrez-Chacoff, J.; Alba, M.A.; Murgia, G.; Espígol-Frigolé, G.; Sánchez, M.; Arguis, P.; et al. Effect of glucocorticoid treatment on computed tomography angiography detected large-vessel inflammation in giant-cell arteritis. A prospective, longitudinal study. Medicine 2015, 94, e486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, R.; Smyth, A.E.; Kavanagh, R.G.; O’donohoe, R.L.; Purcell, Y.; Heffernan, E.J.; Molloy, E.S.; McNeill, G.; Killeen, R.P. Diagnostic Utility of Computed Tomographic Angiography in Giant-Cell Arteritis. Stroke 2018, 49, 2233–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duftner, C.; Dejaco, C.; Sepriano, A.; Falzon, L.; Schmidt, W.A.; Ramiro, S. Imaging in diagnosis, outcome prediction and monitoring of large vessel vasculitis: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis informing the EULAR recommendations. RMD Open 2018, 4, e000612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therkildsen, P.; de Thurah, A.; Nielsen, B.D.; Hansen, I.T.; Eldrup, N.; Nørgaard, M.; Hauge, E.-M. Increased risk of thoracic aortic complications among patients with giant cell arteritis: A nationwide, population-based cohort study. Rheumatol. Oxf. Engl. 2022, 61, 2931–2941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.M.; O’Fallon, W.M.; Hunder, G.G. Increased incidence of aortic aneurysm and dissection in giant cell (temporal) arteritis. A population-based study. Ann. Intern. Med. 1995, 122, 502–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, J.C.; Kiran, A.; Maskell, J.; Hutchings, A.; Arden, N.; Dasgupta, B.; Hamilton, W.; Emin, A.; Culliford, D.; A Luqmani, R. The relative risk of aortic aneurysm in patients with giant cell arteritis compared with the general population of the UK. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2015, 74, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martínez, A.; Hernández-Rodríguez, J.; Arguis, P.; Paredes, P.; Segarra, M.; Lozano, E.; Nicolau, C.; Ramírez, J.; Lomeña, F.; Josa, M.; et al. Development of aortic aneurysm/dilatation during the followup of patients with giant cell arteritis: A cross-sectional screening of fifty-four prospectively followed patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2008, 59, 422–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martínez, A.; Arguis, P.; Prieto-González, S.; Espígol-Frigolé, G.; A Alba, M.; Butjosa, M.; Tavera-Bahillo, I.; Hernández-Rodríguez, J.; Cid, M.C. Prospective long term follow-up of a cohort of patients with giant cell arteritis screened for aortic structural damage (aneurysm or dilatation). Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2014, 73, 1826–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.F.; Fiessinger, J.N.; Sapoval, M.; Hernigou, A.; Mousseaux, E.; Emmerich, J.; Piette, J.-C. Follow-up electron beam CT for the management of early phase Takayasu arteritis. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 2001, 25, 924–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, S.; Akiba, H.; Tamakawa, M.; Yama, N.; Takeda, M.; Hareyama, M.; Nakata, T.; Shimamoto, K. The spectrum of findings in supra-aortic Takayasu’s arteritis as seen on spiral CT angiography and digital subtraction angiography. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2001, 24, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarma, K.; Handique, A.; Phukan, P.; Daniala, C.; Chutia, H.; Barman, B. Magnetic Resonance Angiography and Multidetector CT Angiography in the Diagnosis of Takayasu’s Arteritis: Assessment of Disease Extent and Correlation with Disease Activity. Curr. Med. Imaging 2022, 18, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keleşoğlu Dinçer, A.B.; Kılıç, L.; Erden, A.; Kalyoncu, U.; Hazirolan, T.; KirAz, S.; Karadağ, Ö. Imaging modalities used in diagnosis and follow-up of patients with Takayasu’s arteritis. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2021, 51, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, J.T.; Statler, J.D. Advances in vascular imaging. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2007, 87, 975–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanson, A.W. Imaging findings in extracranial (giant cell) temporal arteritis. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2000, 18 (Suppl. S20), S43–S48. [Google Scholar]

- Endo, M.; Tomizawa, Y.; Nishida, H.; Aomi, S.; Nakazawa, M.; Tsurumi, Y.; Kawana, M.; Kasanuki, H. Angiographic findings and surgical treatments of coronary artery involvement in Takayasu arteritis. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2003, 125, 570–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Direskeneli, H. Clinical assessment in Takayasu’s arteritis: Major challenges and controversies. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2017, 35 (Suppl. S103), 189–193. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aeschlimann, F.A.; Raimondi, F.; Leiner, T.; Aquaro, G.D.; Saadoun, D.; Grotenhuis, H.B. Overview of Imaging in Adult- and Childhood-onset Takayasu Arteritis. J. Rheumatol. 2022, 49, 346–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastri, M.V.; Baptista, L.P.S.; Baroni, R.H.; de Ávila, L.F.; Leite, C.C.; de Castro, C.C.; Cerri, G.G. Gadolinium-enhanced three-dimensional MR angiography of Takayasu arteritis. Radiogr. Rev. Publ. Radiol. Soc. N. Am. Inc. 2004, 24, 773–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, W.A. Imaging in vasculitis. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2013, 27, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, W.A.; Moll, A.; Seifert, A.; Schicke, B.; Gromnica-Ihle, E.; Krause, A. Prognosis of large-vessel giant cell arteritis. Rheumatology 2008, 47, 1406–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kebed, D.T.; Bois, J.P.; Connolly, H.M.; Scott, C.G.; Bowen, J.M.; Warrington, K.J.; Makol, A.; Greason, K.L.; Schaff, H.V.; Anavekar, N.S. Spectrum of Aortic Disease in the Giant Cell Arteritis Population. Am. J. Cardiol. 2018, 121, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Gay, M.A.; Garcia-Porrua, C.; Piñeiro, A.; Pego-Reigosa, R.; Llorca, J.; Hunder, G.G. Aortic aneurysm and dissection in patients with biopsy-proven giant cell arteritis from northwestern Spain: A population-based study. Medicine 2004, 83, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuenninghoff, D.M.; Hunder, G.G.; Christianson, T.J.H.; McClelland, R.L.; Matteson, E.L. Incidence and predictors of large-artery complication (aortic aneurysm, aortic dissection, and/or large-artery stenosis) in patients with giant cell arteritis: A population-based study over 50 years. Arthritis Rheum. 2003, 48, 3522–3531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, I.; Shibuya, H.; Matsubara, O.; Umehara, I.; Makino, T.; Numano, F.; Suzuki, S. Pulmonary artery disease in Takayasu’s arteritis: Angiographic findings. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 1992, 159, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, M.; Hatron, P.Y.; Hachulla, E.; Warembourg, H.; Devulder, B. Takayasu’s arteritis diagnosed at the early systemic phase: Diagnosis with noninvasive investigation despite normal findings on angiography. J. Rheumatol. 1998, 25, 376–377. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mason, J.C. Takayasu arteritis—Advances in diagnosis and management. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2010, 6, 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canyigit, M.; Peynircioglu, B.; Hazirolan, T.; Dagoglu, M.G.; Cil, B.E.; Haliloglu, M.; Balkanci, F.; Besim, A. Imaging characteristics of Takayasu arteritis. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2007, 30, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülcü, A.; Gezer, N.S.; Akar, S.; Akkoç, N.; Önen, F.; Göktay, A.Y. Long-Term Follow-Up of Endovascular Repair in the Management of Arterial Stenosis Caused by Takayasu’s Arteritis. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2017, 42, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, G.S.; Hallahan, C.W.; Giordano, J.; Leavitt, R.Y.; Fauci, A.S.; Rottem, M.; Hoffman, G.S. Takayasu arteritis. Ann. Intern. Med. 1994, 120, 919–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelhamer, J.H.; Volkman, D.J.; Parrillo, J.E.; Lawley, T.J.; Johnston, M.R.; Fauci, A.S. Takayasu’s arteritis and its therapy. Ann. Intern. Med. 1985, 103, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Nieuwland, M.; Colin, E.M.; Vermeer, M.; Wagenaar, N.R.L.; Vijlbrief, O.D.; van Zandwijk, J.K.; A Slart, R.H.J.; Koffijberg, H.; Jebbink, E.G.; van der Geest, K.S.M.; et al. A direct comparison in diagnostic performance of CDUS, FDG-PET/CT and MRI in patients suspected of giant cell arteritis. Rheumatol. Oxf. Engl. 2025, 64, 1392–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukhtyar, C.B.; Alanoor, S.; Ducker, G. An analysis of the first relapse in giant cell arteritis using ultrasonography. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2025, 71, 152646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, R.; Rebello, R.; Guggenberger, K.V.; Baker, J.F.; Banerjee, S.; Kurtz, R.; Amudala, N.; Merkel, P.A.; Rhee, R.L. Longitudinal changes on cranial magnetic resonance imaging in relapsing giant cell arteritis. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2025, 74, 152815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brittain, J.M.; Hansen, M.S.; Hamann, S. Giant Cell Arteritis Confirmed by 2-[18F]FDG PET/CT, Missed on Biopsy. Ophthalmology 2024, 131, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pugh, D.; Patel, D.; Macnaught, G.; Czopek, A.; Bruce, L.; Donachie, J.; Gallacher, P.J.; Tan, S.; Ahlman, M.; Grayson, P.C.; et al. 18F-FDG-PET/MR imaging to monitor disease activity in large vessel vasculitis. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vries, H.S.; van Praagh, G.D.; Nienhuis, P.H.; Alic, L.; Slart, R.H.J.A. A Machine Learning Model Based on Radiomic Features as a Tool to Identify Active Giant Cell Arteritis on [18F]FDG-PET Images During Follow-Up. Diagn. Basel Switz. 2025, 15, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roncato, C.; Perez, L.; Brochet-Guégan, A.; Allix-Beguec, C.; Raimbeau, A.; Gautier, G.; Agard, C.; Ploton, G.; Moisselin, S.; Lorcerie, F.; et al. Colour Doppler ultrasound of temporal arteries for the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis: A multicentre deep learning study. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2020, 38 (Suppl. S124), 120–125. [Google Scholar]

| Modality | Resolution | Specificity | Monitoring Capability | Clinical Utility | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrasound | High for superficial arteries; limited for deep vessels. | Moderate–high, mostly based on halo and macaroni signs. | Sensitive to inflammatory changes (wall thickness and halo sign). Responsive under IL-6 blockade. Enables evaluation of structural damage. | Non-invasive, radiation-free, cost-effective, repeatable. | Operator-dependent; limited resolution for deep vessel evaluation; uncertain significance of residual or subclinical vascular changes. |

| MRI/MRA | High for vessel wall and lumen evaluation; broad anatomic coverage. | High—detects mural thickening, oedema, and contrast enhancement. | Suitable for serial monitoring of inflammation and structural damage. | Radiation-free. Preferred imaging monitoring relapse and disease extent in TAK. | Limited availability and high cost; contraindicated in patients with non-MRI-compatible devices. The clinical significance of persistent mural enhancement or subclinical findings remains uncertain. |

| FDG-PET/CT | Moderate; whole-body coverage. | High for active metabolic activity. | Sensitive to metabolic changes; useful for assessing treatment response. | Valuable in detecting relapse and for patients receiving IL-6 inhibitors. | Radiation exposure, high cost, limited availability, and low spatial resolution; limited sensitivity for vascular complications; uncertain significance of persistent or low-grade vascular uptake. |

| CT/CTA | High; wide anatomic coverage. | High for vascular structural characterisation; poor for inflammatory changes. | Better suited for evaluating chronic vascular damage rather than active inflammation. | Widely available; rapid acquisition time; enables anatomic mapping. | Ionising radiation; use of iodinated contrast; limited ability to detect active inflammation. |

| Conventional angiography | Moderate. | High for vascular lumen characterisation; no wall assessment. | Useful for evaluating structural vessel damage; not suitable for inflammation monitoring. | Reserved for guiding or planning endovascular interventions. | Invasive; radiation exposure; contrast use; procedural risks. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sopa, I.; Pereira da Costa, R.; Martins Martinho, J.; Ponte, C. The Role of Imaging in Monitoring Large Vessel Vasculitis: A Comprehensive Review. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1505. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15111505

Sopa I, Pereira da Costa R, Martins Martinho J, Ponte C. The Role of Imaging in Monitoring Large Vessel Vasculitis: A Comprehensive Review. Biomolecules. 2025; 15(11):1505. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15111505

Chicago/Turabian StyleSopa, Inês, Roberto Pereira da Costa, Joana Martins Martinho, and Cristina Ponte. 2025. "The Role of Imaging in Monitoring Large Vessel Vasculitis: A Comprehensive Review" Biomolecules 15, no. 11: 1505. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15111505

APA StyleSopa, I., Pereira da Costa, R., Martins Martinho, J., & Ponte, C. (2025). The Role of Imaging in Monitoring Large Vessel Vasculitis: A Comprehensive Review. Biomolecules, 15(11), 1505. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15111505