Predicting the Impact of Glycosylation on the Structure and Thermostability of Helicobacter pylori Blood Group Binding Adhesin

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. BabA Expression and Purification

2.2. Solution Property Assessment of BabA by Dynamic Light Scattering

2.3. Thermal Stability of Recombinant BabA

2.4. Glycosylation Prediction

2.5. Analysis of Shielding Effects of Glycosylation of BabA Using GlycoSHIELD

2.6. Molecular Dynamics Simulations

3. Results

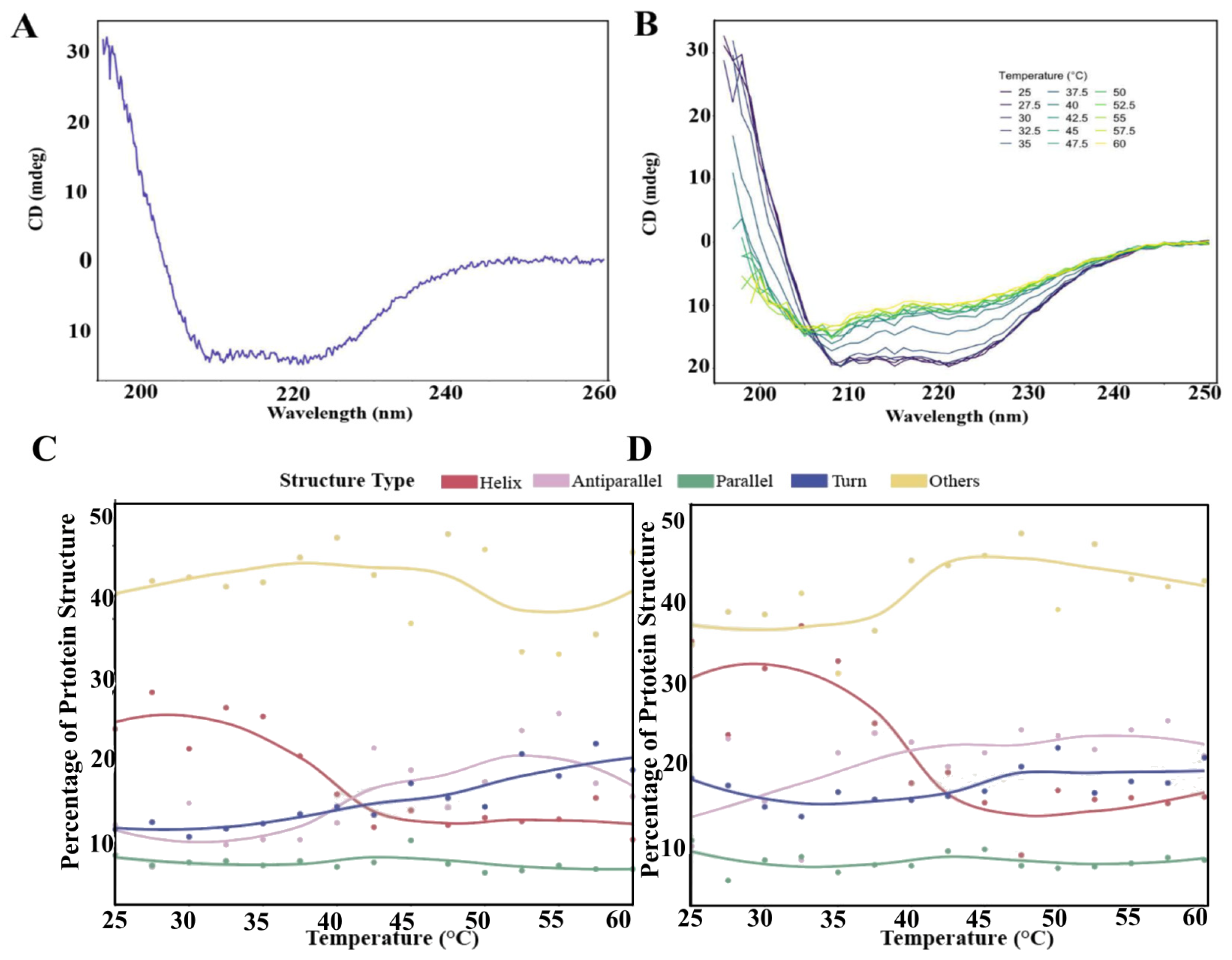

3.1. Stability Analysis of Recombinant BabA Expressed in E. coli

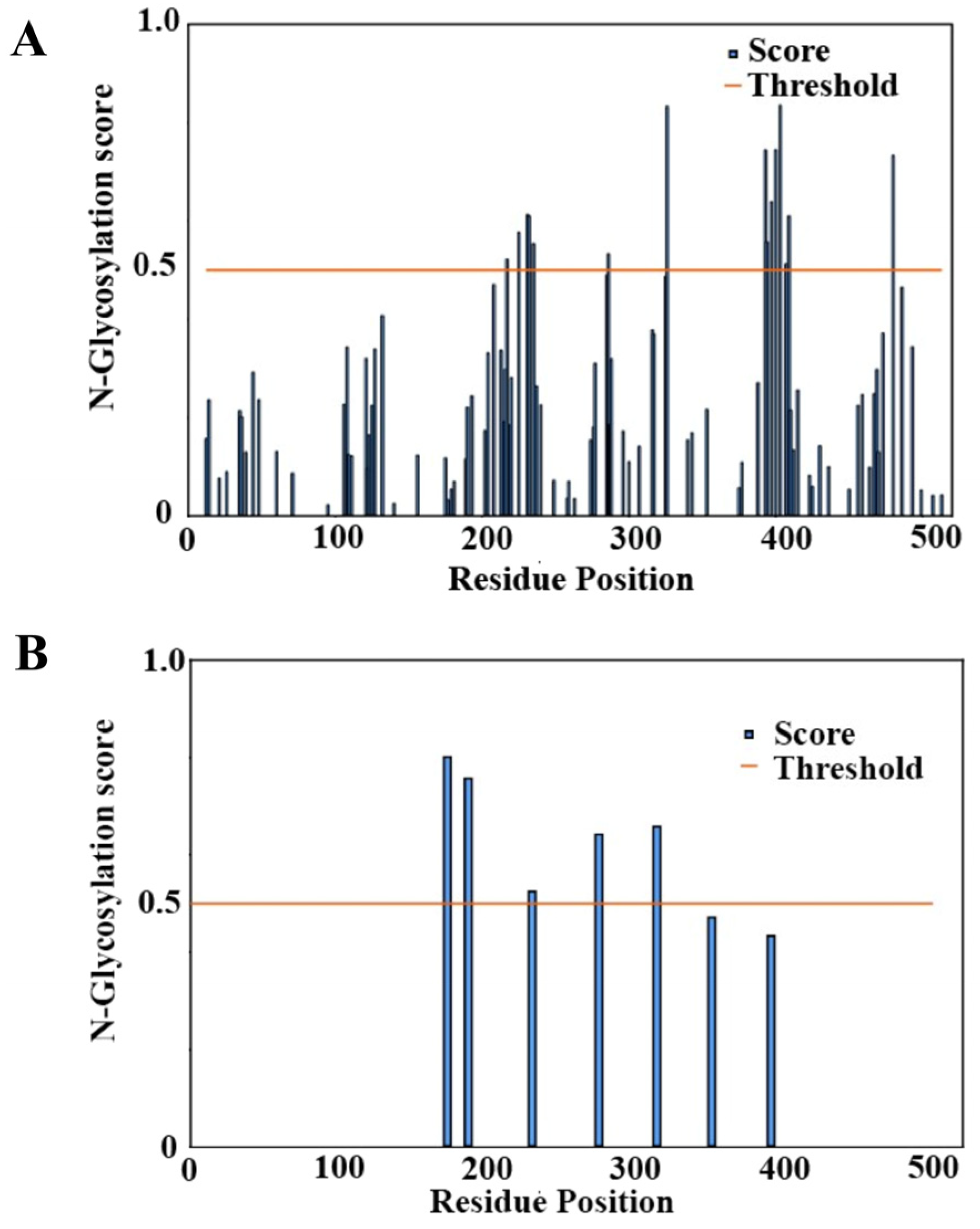

3.2. Sequence-Based Prediction of Glycosylation Sites of BabA

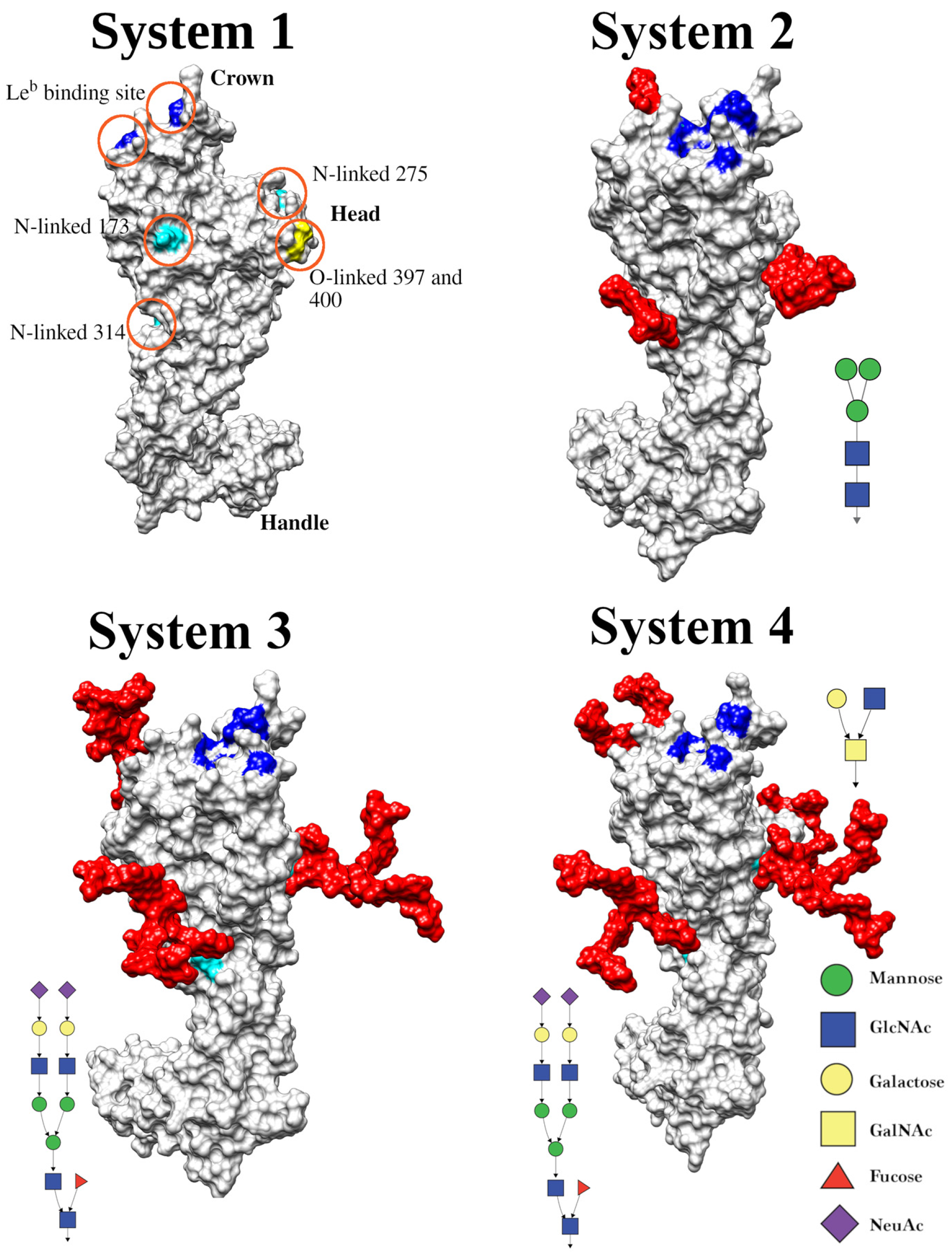

3.3. Structure-Based Prediction of Glycosylation of the BabA Extracellular Region

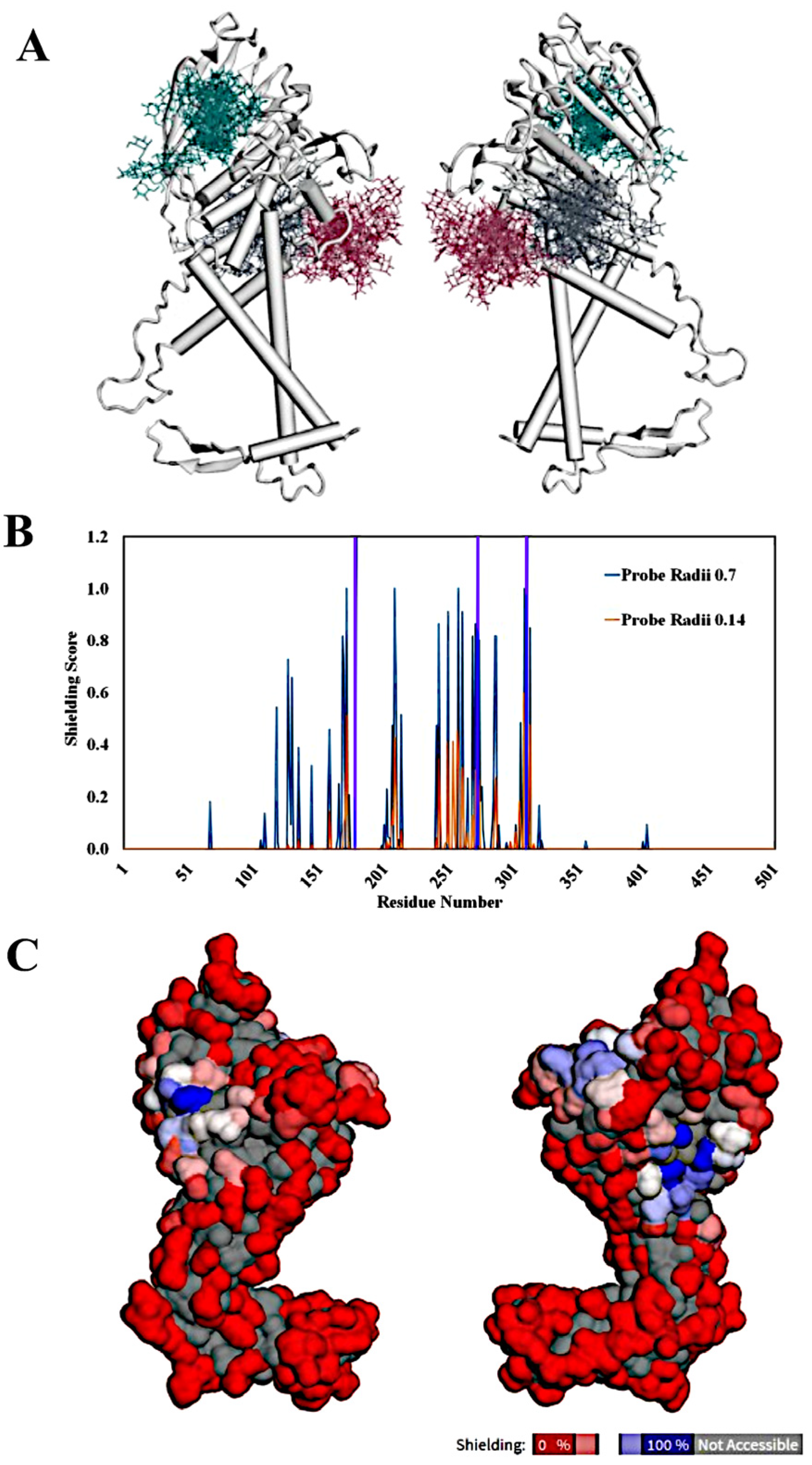

3.4. GlycoSHIELD Analysis

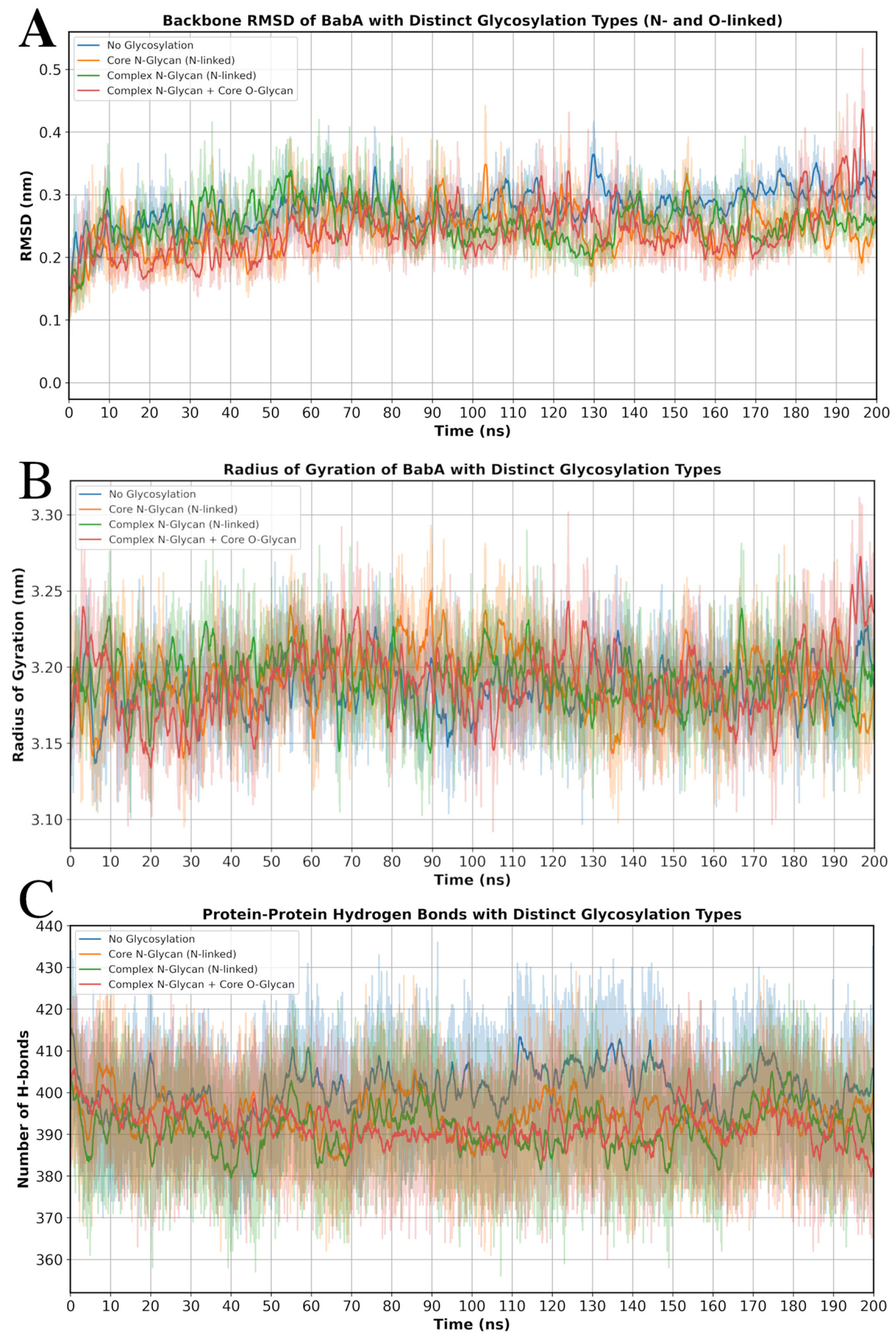

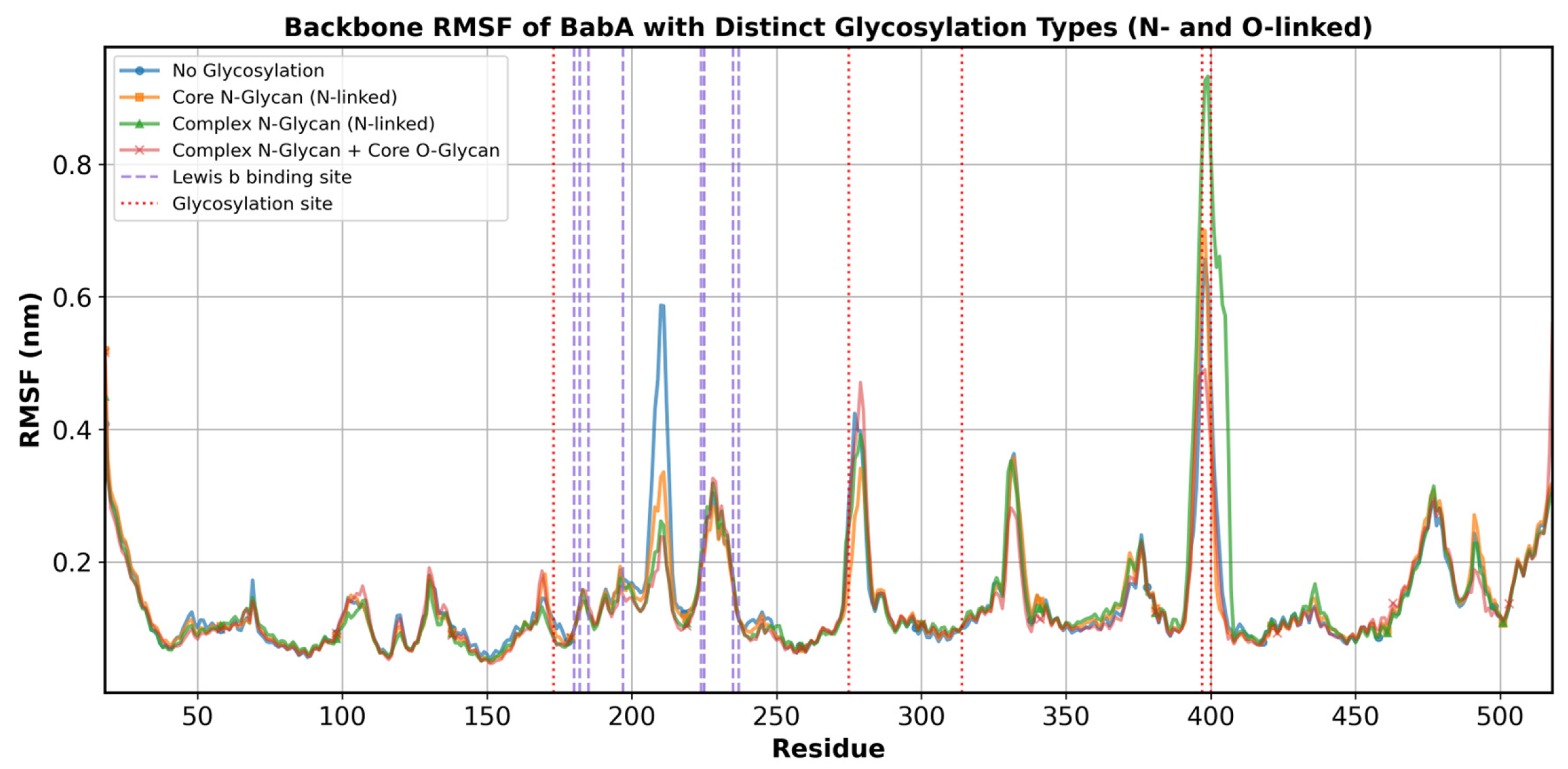

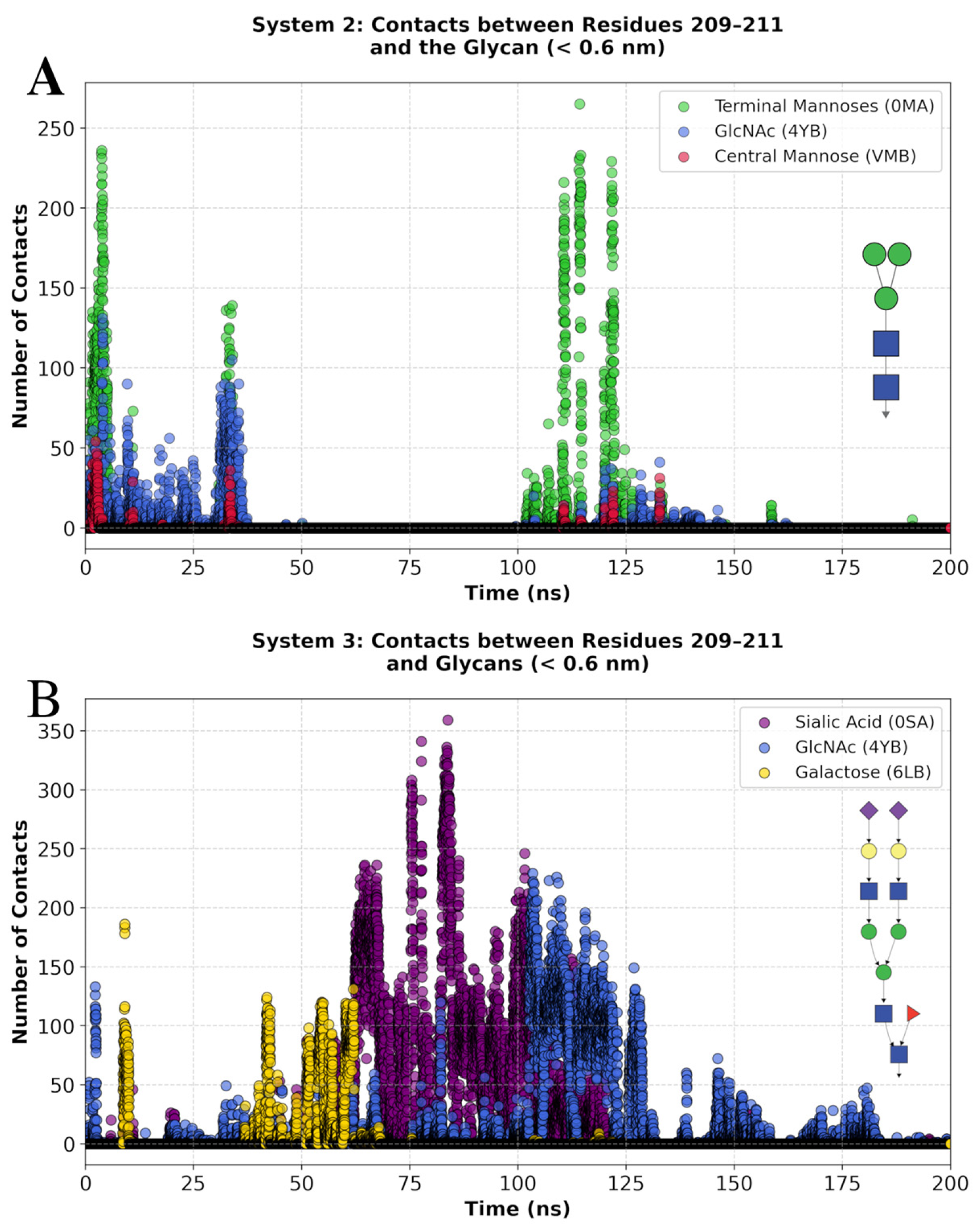

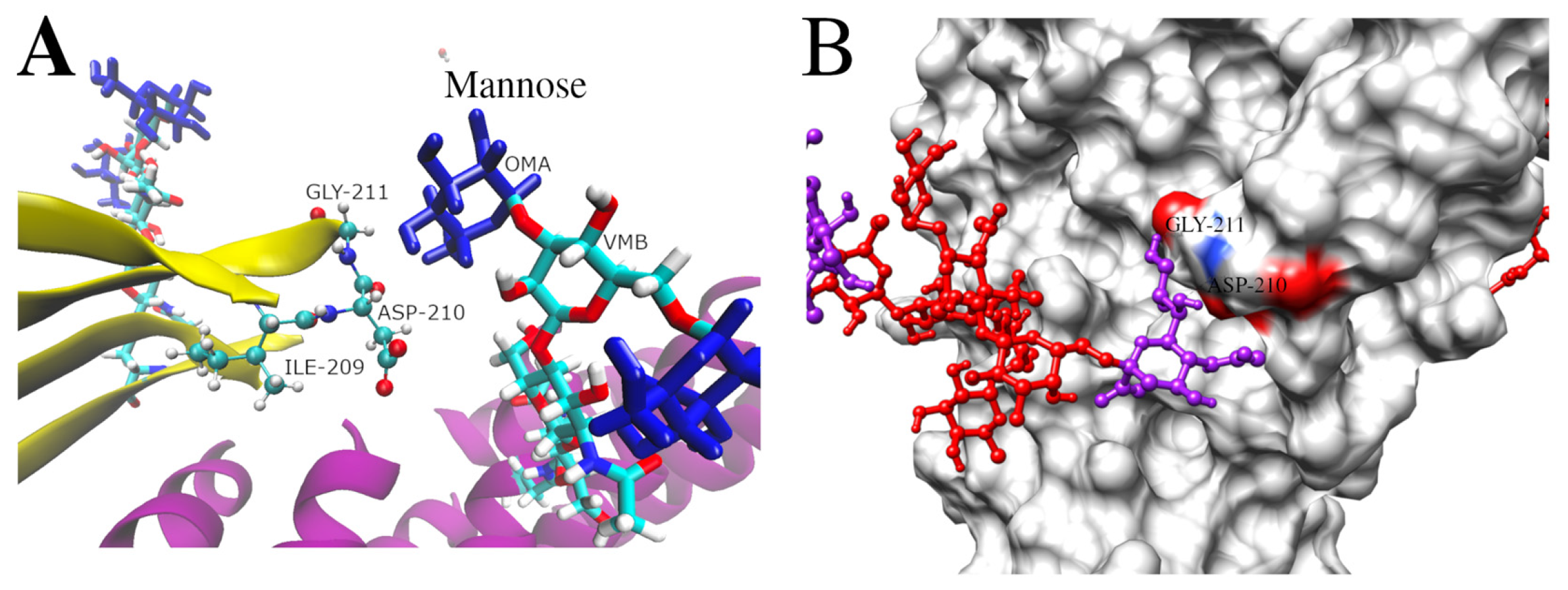

3.5. Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Glycosylated Versions and Non-Glycosylated BabA

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BabA | blood group binding adhesin |

| CD | circular dichroism |

| CV | column volume |

| DH | hydrodynamic diameter |

| DLS | dynamic light scattering |

| IMAC | immobilized metal affinity chromatography |

| IPTG | isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside |

| Leb | Lewis b |

| LPS | lipopolysaccharide |

| MD | molecular dynamics |

| nanoDSF | nano differential scanning fluorometry |

| OD | optical density |

| OMP | outer membrane proteins |

| PDI | polydispersity index |

| PTM | post-translational modifications |

| Rg | radius of gyration |

| RMSD | root mean square deviation |

| RMSF | root mean square fluctuation |

| SASA | solvent accessible surface area |

| SD | standard deviation |

References

- Xiong, Y.; Karuppanan, K.; Bernardi, A.; Li, Q.; Kommineni, V.; Dandekar, A.M.; Lebrilla, C.B.; Faller, R.; McDonald, K.A.; Nandi, S. Effects of N-Glycosylation on the Structure, Function, and Stability of a Plant-Made Fc-Fusion Anthrax Decoy Protein. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champasa, K.; Longwell, S.A.; Eldridge, A.M.; Stemmler, E.A.; Dube, D.H. Targeted Identification of Glycosylated Proteins in the Gastric Pathogen Helicobacter pylori (Hp)*. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2013, 12, 2568–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doig, P.; Kinsella, N.; Guerry, P.; Trust, T.J. Characterization of a post-translational modification of Campylobacter flagellin: Identification of a sero-specific glycosyl moiety. Mol. Microbiol. 1996, 19, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berman, H.M.; Westbrook, J.; Feng, Z.; Gilliland, G.; Bhat, T.N.; Weissig, H.; Shindyalov, I.N.; Bourne, P.E. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teng, K.W.; Hsieh, K.S.; Hung, J.S.; Wang, C.J.; Liao, E.C.; Chen, P.C.; Lin, Y.H.; Wu, D.C.; Lin, C.H.; Wang, W.C.; et al. Helicobacter pylori employs a general protein glycosylation system for the modification of outer membrane adhesins. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, 2130650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hage, N.; Howard, T.; Phillips, C.; Brassington, C.; Overman, R.; Debreczeni, J.; Gellert, P.; Stolnik, S.; Winkler, G.S.; Falcone, F.H. Structural basis of Lewis(b) antigen binding by the Helicobacter pylori adhesin BabA. Sci. Adv. 2015, 1, e1500315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walz, A.; Odenbreit, S.; Stühler, K.; Wattenberg, A.; Meyer, H.E.; Mahdavi, J.; Borén, T.; Ruhl, S. Identification of glycoprotein receptors within the human salivary proteome for the lectin-like BabA and SabA adhesins of Helicobacter pylori by fluorescence-based 2-D bacterial overlay. Proteomics 2009, 9, 1582–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borén, T.; Falk, P.; Roth, K.A.; Larson, G.; Normark, S. Attachment of Helicobacter pylori to human gastric epithelium mediated by blood group antigens. Science 1993, 262, 1892–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benktander, J.; Ångström, J.; Breimer, M.E.; Teneberg, S. Redefinition of the carbohydrate binding specificity of Helicobacter pylori BabA adhesin. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 31712–31724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilver, D.; Arnqvist, A.; Ogren, J.; Frick, I.M.; Kersulyte, D.; Incecik, E.T.; Berg, D.E.; Covacci, A.; Engstrand, L.; Borén, T. Helicobacter pylori adhesin binding fucosylated histo-blood group antigens revealed by retagging. Science 1998, 279, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottesmann, M.; Paraskevopoulou, V.; Mohammed, A.; Falcone, F.H.; Hensel, A. BabA and LPS inhibitors against Helicobacter pylori: Pectins and pectin-like rhamnogalacturonans as adhesion blockers. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moonens, K.; Gideonsson, P.; Subedi, S.; Bugaytsova, J.; Romaõ, E.; Mendez, M.; Nordén, J.; Fallah, M.; Rakhimova, L.; Shevtsova, A.; et al. Structural Insights into Polymorphic ABO Glycan Binding by Helicobacter pylori. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 19, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.-C.; Wang, C.-J.; You, C.-K.; Kao, M.-C. Effects of a HP0859 (rfaD) knockout mutation on lipopolysaccharide structure of Helicobacter pylori 26695 and the bacterial adhesion on AGS cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011, 405, 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Tang, X.; Yang, T.; Liao, T.; Debowski, A.W.; Yang, T.; Shen, Y.; Nilsson, H.O.; Haslam, S.M.; Mulloy, B.; et al. Reinvestigation into the role of lipopolysaccharide Glycosyltransferases in Helicobacter pylori protein glycosylation. Gut Microbes 2025, 17, 2455513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkx-Jacques, A.; Obhi, R.K.; Bethune, G.; Creuzenet, C. The Helicobacter pylori flaA1 and wbpB genes control lipopolysaccharide and flagellum synthesis and function. J. Bacteriol. 2004, 186, 2253–2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schirm, M.; Soo, E.C.; Aubry, A.J.; Austin, J.; Thibault, P.; Logan, S.M. Structural, genetic and functional characterization of the flagellin glycosylation process in Helicobacter pylori. Mol. Microbiol. 2003, 48, 1579–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, R.; Amorim, I.; Magalhães, A.; Haesebrouck, F.; Gärtner, F.; Reis, C.A. Adhesion of Helicobacter Species to the Human Gastric Mucosa: A Deep Look Into Glycans Role. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 656439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nothaft, H.; Scott, N.E.; Vinogradov, E.; Liu, X.; Hu, R.; Beadle, B.; Fodor, C.; Miller, W.G.; Li, J.; Cordwell, S.J.; et al. Diversity in the protein N-glycosylation pathways within the Campylobacter genus. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2012, 11, 1203–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosdah, A.A.; Abbott, B.M.; Langendorf, C.G.; Deng, Y.; Truong, J.Q.; Waddell, H.M.M.; Ling, N.X.Y.; Smiles, W.J.; Delbridge, L.M.D.; Liu, G.S.; et al. A novel small molecule inhibitor of human Drp1. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 21531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemka, A.; Nothaft, H.; Zheng, J.; Szymanski, C.M. N-glycosylation of Campylobacter jejuni surface proteins promotes bacterial fitness. Infect. Immun. 2013, 81, 1674–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, A.H.; Maity, S.; Giri, K.; Ambatipudi, K. Protein glycosylation: Sweet or bitter for bacterial pathogens? Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 45, 82–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wacker, M.; Linton, D.; Hitchen, P.G.; Nita-Lazar, M.; Haslam, S.M.; North, S.J.; Panico, M.; Morris, H.R.; Dell, A.; Wren, B.W.; et al. N-linked glycosylation in Campylobacter jejuni and its functional transfer into E. coli. Science 2002, 298, 1790–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, M.; Hu, B. The Role of Adhesion in Helicobacter pylori Persistent Colonization. Curr. Microbiol. 2023, 80, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.S.; Qi, Y.; Im, W. Effects of N-glycosylation on protein conformation and dynamics: Protein Data Bank analysis and molecular dynamics simulation study. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 8926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiß, R.G.; Losfeld, M.-E.; Aebi, M.; Riniker, S. N-Glycosylation Enhances Conformational Flexibility of Protein Disulfide Isomerase Revealed by Microsecond Molecular Dynamics and Markov State Modeling. J. Phys. Chem. B 2021, 125, 9467–9479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez Rollan, C.; Bach Falkenberg, K.; Rennig, M.; Birk Bertelsen, A.; Norholm, M. Protein Expression and Extraction of Hard-to-Produce Proteins in the Periplasmic Space of Escherichia coli v1; protocols.io: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Yoo, H.J.; Park, E.J.; Na, D.H. Nano Differential Scanning Fluorimetry-Based Thermal Stability Screening and Optimal Buffer Selection for Immunoglobulin G. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 15, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, A.J.; Ramalli, S.G.; Wallace, B.A. DichroWeb, a website for calculating protein secondary structure from circular dichroism spectroscopic data. Protein Sci. 2021, 31, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micsonai, A.; Moussong, É.; Wien, F.; Boros, E.; Vadászi, H.; Murvai, N.; Lee, Y.-H.; Molnár, T.; Réfrégiers, M.; Goto, Y.; et al. BeStSel: Webserver for secondary structure and fold prediction for protein CD spectroscopy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, W90–W98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Brunak, S. Prediction of glycosylation across the human proteome and the correlation to protein function. Pac. Symp. Biocomput. 2002, 7, 310–322. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, J.E.; Lund, O.; Tolstrup, N.; Gooley, A.A.; Williams, K.L.; Brunak, S. NetOglyc: Prediction of mucin type O-glycosylation sites based on sequence context and surface accessibility. Glycoconj. J. 1998, 15, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steentoft, C.; Vakhrushev, S.Y.; Joshi, H.J.; Kong, Y.; Vester-Christensen, M.B.; Schjoldager, K.T.B.G.; Lavrsen, K.; Dabelsteen, S.; Pedersen, N.B.; Marcos-Silva, L.; et al. Precision mapping of the human O-GalNAc glycoproteome through SimpleCell technology. EMBO J. 2013, 32, 1478–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Group, W. GLYCAM Web. Available online: https://glycam.org/ (accessed on 23 March 2024).

- Singh, A.; Montgomery, D.; Xue, X.; Foley, B.L.; Woods, R.J. GAG Builder: A web-tool for modeling 3D structures of glycosaminoglycans. Glycobiology 2019, 29, 515–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.-X.; Chang, N.-E.; Reuter, K.; Chang, H.-T.; Yang, T.-J.; von Bülow, S.; Sehrawat, V.; Zerrouki, N.; Tuffery, M.; Gecht, M.; et al. Rapid simulation of glycoprotein structures by grafting and steric exclusion of glycan conformer libraries. Cell 2024, 187, 1296–1311.e1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, M.J.; Murtola, T.; Schulz, R.; Páll, S.; Smith, J.C.; Hess, B.; Lindahl, E. GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 2015, 1–2, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S.; Kim, T.; Iyer, V.G.; Im, W. CHARMM-GUI: A web-based graphical user interface for CHARMM. J. Comput. Chem. 2008, 29, 1859–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, B.R.; Brooks, C.L., 3rd; Mackerell, A.D., Jr.; Nilsson, L.; Petrella, R.J.; Roux, B.; Won, Y.; Archontis, G.; Bartels, C.; Boresch, S.; et al. CHARMM: The biomolecular simulation program. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 1545–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Cheng, X.; Swails, J.M.; Yeom, M.S.; Eastman, P.K.; Lemkul, J.A.; Wei, S.; Buckner, J.; Jeong, J.C.; Qi, Y.; et al. CHARMM-GUI Input Generator for NAMD, GROMACS, AMBER, OpenMM, and CHARMM/OpenMM Simulations Using the CHARMM36 Additive Force Field. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2016, 12, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-J.; Lee, J.; Qi, Y.; Kern, N.R.; Lee, H.S.; Jo, S.; Joung, I.; Joo, K.; Lee, J.; Im, W. CHARMM-GUI Glycan Modeler for modeling and simulation of carbohydrates and glycoconjugates. Glycobiology 2019, 29, 320–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S.; Song, K.C.; Desaire, H.; MacKerell, A.D., Jr.; Im, W. Glycan Reader: Automated sugar identification and simulation preparation for carbohydrates and glycoproteins. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 3135–3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.J.; Lee, J.; Patel, D.S.; Ma, H.; Lee, H.S.; Jo, S.; Im, W. Glycan Reader is improved to recognize most sugar types and chemical modifications in the Protein Data Bank. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 3051–3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branka, A.C. Nose-Hoover chain method for nonequilibrium molecular dynamics simulation. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Phys. Plasmas Fluids Relat. Interdiscip. Top. 2000, 61, 4769–4773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrinello, M.; Rahman, A. Polymorphic transitions in single crystals: A new molecular dynamics method. J. Appl. Phys. 1981, 52, 7182–7190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Rauscher, S.; Nawrocki, G.; Ran, T.; Feig, M.; de Groot, B.L.; Grubmüller, H.; MacKerell, A.D. CHARMM36m: An improved force field for folded and intrinsically disordered proteins. Nat. Methods 2016, 14, 71–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, E.C.; Goddard, T.D.; Pettersen, E.F.; Couch, G.S.; Pearson, Z.J.; Morris, J.H.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF ChimeraX: Tools for structure building and analysis. Protein Sci. 2023, 32, e4792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, D.; Yang, C.; Liu, Z. How Hydrophobicity and the Glycosylation Site of Glycans Affect Protein Folding and Stability: A Molecular Dynamics Simulation. J. Phys. Chem. B 2011, 116, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, F.; Radivojac, P. Post-translational modifications induce significant yet not extreme changes to protein structure. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 2905–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasala, C.; Sharma, S.; Roychowdhury, T.; Moroni, E.; Colombo, G.; Chiosis, G. N-Glycosylation as a Modulator of Protein Conformation and Assembly in Disease. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, D.; Mereiter, S.; Jin Oh, Y.; Monteil, V.; Elder, E.; Zhu, R.; Canena, D.; Hain, L.; Laurent, E.; Grünwald-Gruber, C.; et al. Identification of lectin receptors for conserved SARS-CoV-2 glycosylation sites. EMBO J. 2021, 40, e108375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Jia, Y.; Yuan, K.; Huang, L.; Nadolny, C.; Dong, X.; Ren, X.; Liu, J. Serum Antibody Against Helicobacter pylori FlaA and Risk of Gastric Cancer. Helicobacter 2014, 19, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Parsons, L.M.; Jankowska, E.; Cipollo, J.F. Site-Specific Glycosylation Patterns of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Derived from Recombinant Protein and Viral WA1 and D614G Strains. Front. Chem. 2021, 9, 767448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casalino, L.; Gaieb, Z.; Goldsmith, J.A.; Hjorth, C.K.; Dommer, A.C.; Harbison, A.M.; Fogarty, C.A.; Barros, E.P.; Taylor, B.C.; McLellan, J.S.; et al. Beyond Shielding: The Roles of Glycans in the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein. ACS Cent. Sci. 2020, 6, 1722–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.-L.; Moutoussamy, C.; Tuffery, M.; Varangot, A.; Piskorowski, R.; Hanus, C. Core-N-glycans are atypically abundant at the neuronal surface and regulate glutamate receptor signaling. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, N.M.; Brisson, J.R.; Kelly, J.; Watson, D.C.; Tessier, L.; Lanthier, P.H.; Jarrell, H.C.; Cadotte, N.; St Michael, F.; Aberg, E.; et al. Structure of the N-linked glycan present on multiple glycoproteins in the Gram-negative bacterium, Campylobacter jejuni. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 42530–42539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverman, J.M.; Imperiali, B. Bacterial N-Glycosylation Efficiency Is Dependent on the Structural Context of Target Sequons. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 22001–22010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valderrama-Rincon, J.D.; Fisher, A.C.; Merritt, J.H.; Fan, Y.Y.; Reading, C.A.; Chhiba, K.; Heiss, C.; Azadi, P.; Aebi, M.; DeLisa, M.P. An engineered eukaryotic protein glycosylation pathway in Escherichia coli. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2012, 8, 434–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, F.; Huang, W.; Li, C.; Schulz, B.L.; Lizak, C.; Palumbo, A.; Numao, S.; Neri, D.; Aebi, M.; Wang, L.X. A combined method for producing homogeneous glycoproteins with eukaryotic N-glycosylation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2010, 6, 264–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandhal, J.; Woodruff, L.B.; Jaffe, S.; Desai, P.; Ow, S.Y.; Noirel, J.; Gill, R.T.; Wright, P.C. Inverse metabolic engineering to improve Escherichia coli as an N-glycosylation host. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2013, 110, 2482–2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayaraghavan, J.; Kumar, V.; Krishnan, N.P.; Kaufhold, R.T.; Zeng, X.; Lin, J.; van den Akker, F. Structural studies and molecular dynamics simulations suggest a processive mechanism of exolytic lytic transglycosylase from Campylobacter jejuni. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0197136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abouelhadid, S.; Raynes, J.; Bui, T.; Cuccui, J.; Wren, B.W. Characterization of Posttranslationally Modified Multidrug Efflux Pumps Reveals an Unexpected Link between Glycosylation and Antimicrobial Resistance. mBio 2020, 11, e02604-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira, M.V.D.; da Costa, K.S.; Silva, J.R.A.; Lameira, J.; Lima, A.H. Role of UDP-N-acetylmuramic acid in the regulation of MurA activity revealed by molecular dynamics simulations. Protein Sci. 2024, 33, e4969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Month | Mean DH a (nm) | SD b DH a (nm) | Mean PDI c | SD b PDI c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 9.58 | 0.27 | 0.3 | 0.02 |

| 1 | 8.17 | 0.32 | 0.19 | 0.04 |

| 6 | 9.11 | 1.9 | 0.18 | 0.04 |

| Context | Chain | Linkage | Residue Number | SASA a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LVN * QT | A | N | 314 | 84.1 + |

| ASN * SS | A | N | 275 | 82.8 + |

| AGT * GG | A | O | 397 | 76.5 + |

| KVN * VT | A | N | 173 | 70.5 + |

| GGT * QG | A | O | 400 | 40.4 + |

| PGT * VT | A | O | 407 | 38.2 |

| Indicator | System 1 a | System 2 | System 3 | System 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSD (Backbone) [nm] | 0.243 ± 0.038 | 0.244 ± 0.044 | 0.254 ± 0.039 | 0.241 ± 0.049 |

| Radius of Gyration [nm] | 3.186 ± 0.024 | 3.192 ± 0.026 | 3.192 ± 0.025 | 3.191 ± 0.029 |

| H-bonds (average) | 400.64 ± 9.45 | 394.25 ± 8.87 | 391.2 ± 9.2 | 392.1 ± 8.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sijmons, D.; Islas Rios, H.; Turner, B.R.; Wanicek, E.; Holien, J.K.; Walduck, A.K.; Ramsland, P.A. Predicting the Impact of Glycosylation on the Structure and Thermostability of Helicobacter pylori Blood Group Binding Adhesin. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1480. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15101480

Sijmons D, Islas Rios H, Turner BR, Wanicek E, Holien JK, Walduck AK, Ramsland PA. Predicting the Impact of Glycosylation on the Structure and Thermostability of Helicobacter pylori Blood Group Binding Adhesin. Biomolecules. 2025; 15(10):1480. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15101480

Chicago/Turabian StyleSijmons, Daniel, Heber Islas Rios, Benjamin R. Turner, Emma Wanicek, Jessica K. Holien, Anna K. Walduck, and Paul A. Ramsland. 2025. "Predicting the Impact of Glycosylation on the Structure and Thermostability of Helicobacter pylori Blood Group Binding Adhesin" Biomolecules 15, no. 10: 1480. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15101480

APA StyleSijmons, D., Islas Rios, H., Turner, B. R., Wanicek, E., Holien, J. K., Walduck, A. K., & Ramsland, P. A. (2025). Predicting the Impact of Glycosylation on the Structure and Thermostability of Helicobacter pylori Blood Group Binding Adhesin. Biomolecules, 15(10), 1480. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15101480