Novel Insights into the Links between N6-Methyladenosine and Regulated Cell Death in Musculoskeletal Diseases

Abstract

1. Introduction

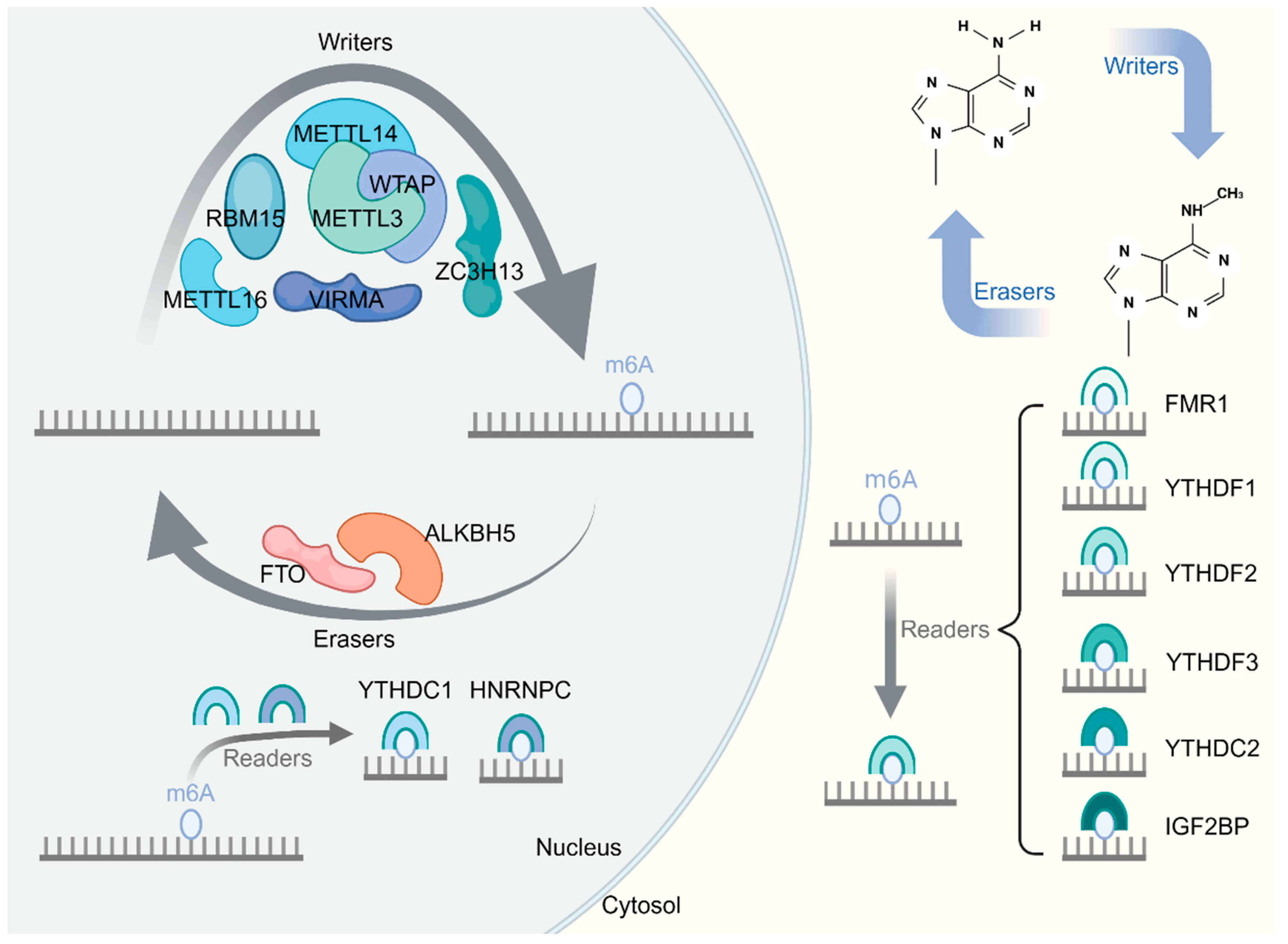

2. m6A Modification

3. The Links between m6A and Regulated Cell Death

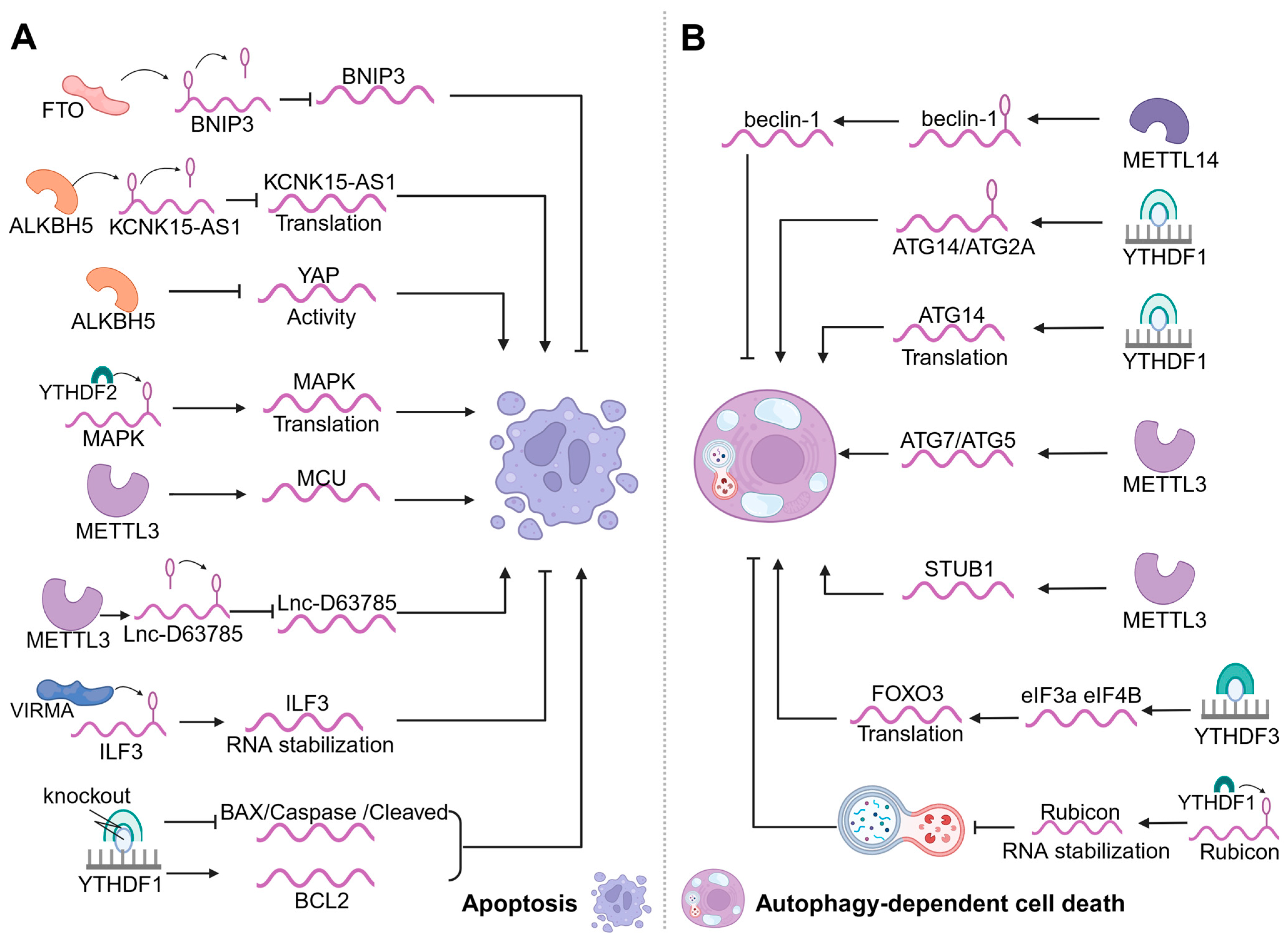

3.1. m6A Modification and Apoptosis

3.2. m6A Modification and Autophagy-Dependent Cell Death

3.3. m6A Modification and Ferroptosis

3.4. m6A Modifications and Other Regulated Cell Deaths

4. m6A and Regulated Cell Death in the Musculoskeletal System

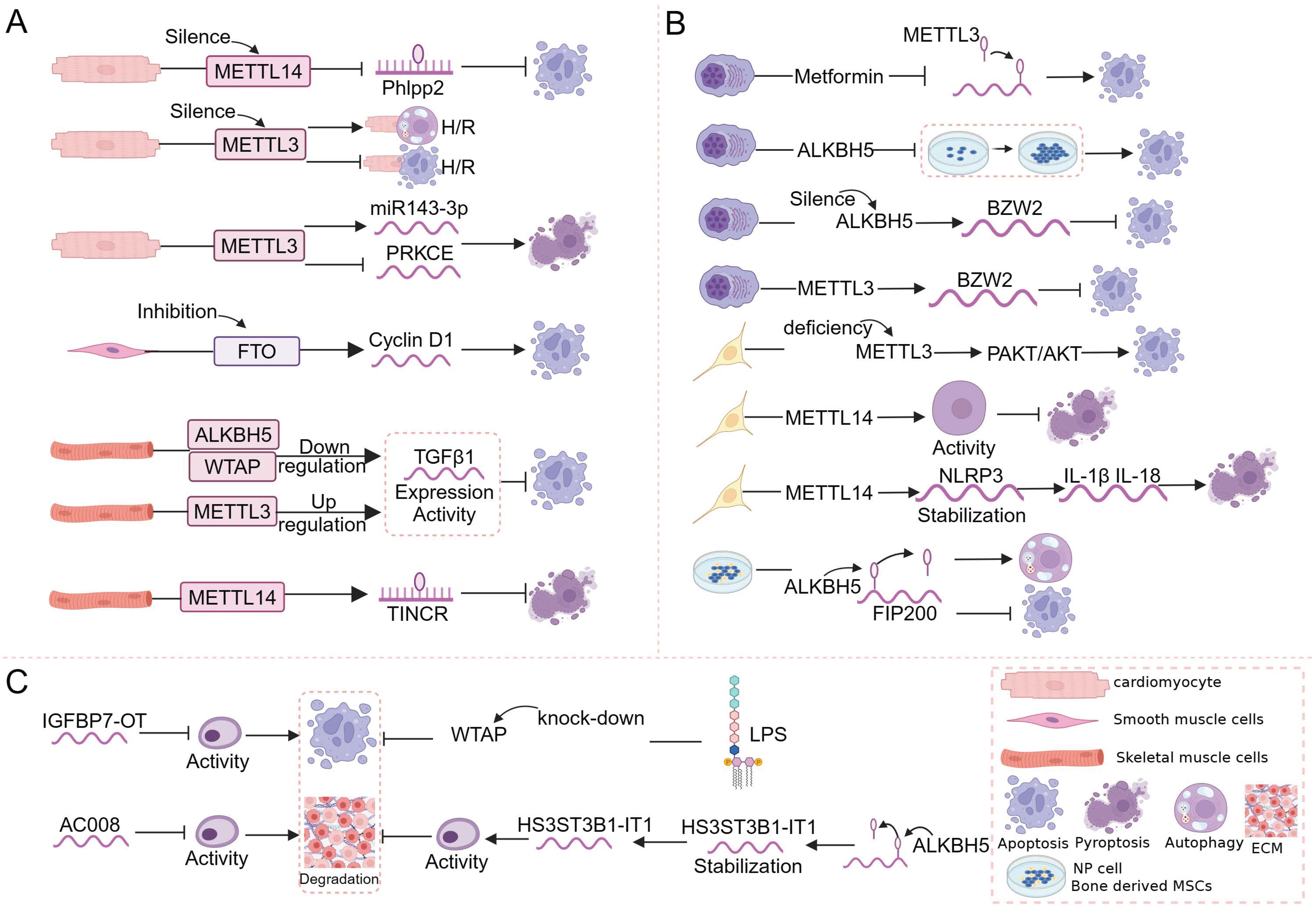

4.1. m6A and Regulated Cell Death in Muscle

4.2. m6A and Regulated Cell Death in Bone

4.3. m6A and Regulated Cell Death in Cartilage

5. Links between m6A and Regulated Cell Death in Musculoskeletal Diseases

5.1. Osteoarthritis

5.2. Osteosarcoma

5.3. Multiple Myeloma

5.4. Other Types of Musculoskeletal Disorders

6. Clinical Applications of m6A-Mediated Regulated Cell Death in Musculoskeletal Diseases

7. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Patel, H.; Chen, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, Z.S.; Wang, H. Epigenetic modification of m6A regulator proteins in cancer. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, H.; Yuan, X.; Wu, S.; Yuan, Y.; Cui, L.; Lin, D.; Peng, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, F. Effects of writers, erasers and readers within miRNA-related m6A modification in cancers. Cell Prolif. 2023, 56, e13340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Guo, H.; Wang, L.; Yang, L.; Shao, Z.; Zhang, W. Recent advances in crosstalk between N6-methyladenosine (m6A) modification and circular RNAs in cancer. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2022, 27, 947–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, C.; Yin, C.; Lin, K.; Li, Y.; Yang, Q.; Wu, Z.; Du, H.; Ren, D.; Dai, Y.; Peng, X. m6A modification of lncRNA PCAT6 promotes bone metastasis in prostate cancer through IGF2BP2-mediated IGF1R mRNA stabilization. Clin. Transl. Med. 2021, 11, e426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galluzzi, L.; Bravo-San Pedro, J.M.; Vitale, I.; Aaronson, S.A.; Abrams, J.M.; Adam, D.; Alnemri, E.S.; Altucci, L.; Andrews, D.; Annicchiarico-Petruzzelli, M.; et al. Essential versus accessory aspects of cell death: Recommendations of the NCCD 2015. Cell Death Differ. 2015, 22, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Ye, M.; Bai, J.; Hu, C.; Lu, F.; Gu, D.; Yu, P.; Tang, Q. Novel insights into the interplay between m6A modification and programmed cell death in cancer. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2023, 19, 1748–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, I.; Rayamajhi, M.; Miao, E.A. Programmed cell death as a defence against infection. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 17, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, S.K.; Li, C.Y.; Lin, I.L.; Syue, W.J.; Chen, Y.F.; Cheng, K.C.; Teng, Y.N.; Lin, Y.H.; Yen, C.H.; Chiu, C.C. Inflammation-related pyroptosis, a novel programmed cell death pathway, and its crosstalk with immune therapy in cancer treatment. Theranostics 2021, 11, 8813–8835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Zhang, X.; Yu, K.; Xu, X.; Chen, T.; Shi, Y.; Wang, Y.; Qiu, S.; Guo, S.; Cui, J.; et al. Targeting SLC3A2 subunit of system X(C)(-) is essential for m6A reader YTHDC2 to be an endogenous ferroptosis inducer in lung adenocarcinoma. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2021, 168, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Y.; Zheng, S.; Xie, X.; Ye, F.; Hu, X.; Tian, Z.; Yan, S.M.; Yang, L.; Kong, Y.; Tang, Y.; et al. N6-methyladenosine regulated FGFR4 attenuates ferroptotic cell death in recalcitrant HER2-positive breast cancer. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, F.H.; Fu, X.H.; Li, G.Q.; He, Q.; Qiu, X.G. FTO Prevents Thyroid Cancer Progression by SLC7A11 m6A Methylation in a Ferroptosis-Dependent Manner. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 857765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Hu, Y.; Weng, M.; Liu, X.; Wan, P.; Hu, Y.; Ma, M.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, H.; Lv, K. Hypoxia inducible lncRNA-CBSLR modulates ferroptosis through m6A-YTHDF2-dependent modulation of CBS in gastric cancer. J. Adv. Res. 2022, 37, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Kong, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.A. Novel insights into the interaction between N6-methyladenosine methylation and noncoding RNAs in musculoskeletal disorders. Cell Prolif. 2022, 55, e13294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Lu, M.; Liu, D.; Shi, Y.; Ren, J.; Wang, S.; Jing, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, Q.; Li, H.; et al. m6A epitranscriptomic regulation of tissue homeostasis during primate aging. Nat. Aging 2023, 3, 705–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, W.; Jin, Q.; Li, L. Protective mechanism of demethylase fat mass and obesity-associated protein in energy metabolism disorder of hypoxia-reoxygenation-induced cardiomyocytes. Exp. Physiol. 2021, 106, 2423–2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, M.; Xu, S.; Liu, L.; Zhang, M.; Guo, J.; Yuan, Y.; Xu, J.; Chen, X.; Zou, J. m6A Methylation Regulates Osteoblastic Differentiation and Bone Remodeling. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 783322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolen, J.S.; Aletaha, D.; Barton, A.; Burmester, G.R.; Emery, P.; Firestein, G.S.; Kavanaugh, A.; McInnes, I.B.; Solomon, D.H.; Strand, V.; et al. Rheumatoid arthritis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2018, 4, 18001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martel-Pelletier, J.; Barr, A.J.; Cicuttini, F.M.; Conaghan, P.G.; Cooper, C.; Goldring, M.B.; Goldring, S.R.; Jones, G.; Teichtahl, A.J.; Pelletier, J.P. Osteoarthritis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2016, 2, 16072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwinnutt, J.M.; Wieczorek, M.; Balanescu, A.; Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A.; Boonen, A.; Cavalli, G.; de Souza, S.; de Thurah, A.; Dorner, T.E.; Moe, R.H.; et al. 2021 EULAR recommendations regarding lifestyle behaviours and work participation to prevent progression of rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2023, 82, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, M.; Yang, D.; Ma, Y.; Tang, Y.; Xing, M.; Li, L.; Chen, L.; Jin, Y.; Ma, C. m6A-mediated upregulation of AC008 promotes osteoarthritis progression through the miR-328-3p-AQP1/ANKH axis. Exp. Mol. Med. 2021, 53, 1723–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Hong, F.; Ding, S.; Yang, J.; Zhang, M.; Ma, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Yang, D.; Jin, Y.; Ma, C. METTL3-mediated m6A modification of IGFBP7-OT promotes osteoarthritis progression by regulating the DNMT1/DNMT3a-IGFBP7 axis. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 112589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Shen, X.; Yan, C.; Xiong, W.; Ma, Z.; Tan, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, J.; Duan, A.; et al. Extracellular vesicles derived from human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells alleviate osteoarthritis of the knee in mice model by interacting with METTL3 to reduce m6A of NLRP3 in macrophage. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 13, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominissini, D.; Moshitch-Moshkovitz, S.; Schwartz, S.; Salmon-Divon, M.; Ungar, L.; Osenberg, S.; Cesarkas, K.; Jacob-Hirsch, J.; Amariglio, N.; Kupiec, M.; et al. Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature 2012, 485, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chelmicki, T.; Roger, E.; Teissandier, A.; Dura, M.; Bonneville, L.; Rucli, S.; Dossin, F.; Fouassier, C.; Lameiras, S.; Bourc’his, D. m6A RNA methylation regulates the fate of endogenous retroviruses. Nature 2021, 591, 312–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, K.; Hu, J.; Huang, Y.; Yu, S.; Yang, Q.; Sun, F.; Wu, C.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, X.; et al. m6A Regulator-Based Methylation Modification Patterns Characterized by Distinct Tumor Microenvironment Immune Profiles in Rectal Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 879405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Hsu, P.J.; Chen, Y.S.; Yang, Y.G. Dynamic transcriptomic m6A decoration: Writers, erasers, readers and functions in RNA metabolism. Cell Res. 2018, 28, 616–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.; Liu, J.; Jiang, W.; Wang, P.; Sun, C.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, H. METTL3 Promotes the Proliferation and Mobility of Gastric Cancer Cells. Open Med. 2019, 14, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Yue, Y.; Han, D.; Wang, X.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Jia, G.; Yu, M.; Lu, Z.; Deng, X.; et al. A METTL3-METTL14 complex mediates mammalian nuclear RNA N6-adenosine methylation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014, 10, 93–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Hsu, P.J.; Xing, X.; Fang, J.; Lu, Z.; Zou, Q.; Zhang, K.J.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, T.; et al. Mettl3-/Mettl14-mediated mRNA N6-methyladenosine modulates murine spermatogenesis. Cell Res. 2017, 27, 1216–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Peng, C.; Chen, J.; Chen, D.; Yang, B.; He, B.; Hu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, H.; Dai, L.; et al. WTAP facilitates progression of hepatocellular carcinoma via m6A-HuR-dependent epigenetic silencing of ETS1. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.Y.; Gao, J.; Sun, X.; Cao, M.D.; Shi, L.; Xia, T.S.; Zhou, W.B.; Wang, S.; Ding, Q.; Wei, J.F. KIAA1429 acts as an oncogenic factor in breast cancer by regulating CDK1 in an N6-methyladenosine-independent manner. Oncogene 2019, 38, 6123–6141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Castro-Hernández, R.; Sokpor, G.; Pham, L.; Narayanan, R.; Rosenbusch, J.; Staiger, J.F.; Tuoc, T. RBM15 Modulates the Function of Chromatin Remodeling Factor BAF155 through RNA Methylation in Developing Cortex. Mol. Neurobiol. 2019, 56, 7305–7320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, J.S. The role of m6A RNA methylation in human cancer. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Wang, X.; Xu, Z.; Cao, Y.; Gong, R.; Yu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Guo, X.; Liu, S.; Yu, M.; et al. ALKBH5 regulates cardiomyocyte proliferation and heart regeneration by demethylating the mRNA of YTHDF1. Theranostics 2021, 11, 3000–3016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wan, J.; Gao, X.; Zhang, X.; Jaffrey, S.R.; Qian, S.B. Dynamic m6A mRNA methylation directs translational control of heat shock response. Nature 2015, 526, 591–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balacco, D.L.; Soller, M. The m6A Writer: Rise of a Machine for Growing Tasks. Biochemistry 2019, 58, 363–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lu, Z.; Gomez, A.; Hon, G.C.; Yue, Y.; Han, D.; Fu, Y.; Parisien, M.; Dai, Q.; Jia, G.; et al. N6-methyladenosine-dependent regulation of messenger RNA stability. Nature 2014, 505, 117–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, P.J.; Zhu, Y.; Ma, H.; Guo, Y.; Shi, X.; Liu, Y.; Qi, M.; Lu, Z.; Shi, H.; Wang, J.; et al. Ythdc2 is an N6-methyladenosine binding protein that regulates mammalian spermatogenesis. Cell Res. 2017, 27, 1115–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Weng, H.; Sun, W.; Qin, X.; Shi, H.; Wu, H.; Zhao, B.S.; Mesquita, A.; Liu, C.; Yuan, C.L.; et al. Recognition of RNA N6-methyladenosine by IGF2BP proteins enhances mRNA stability and translation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018, 20, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Han, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wu, J.; Feng, J.; Qu, L.; Shou, C. HNRNPC as a candidate biomarker for chemoresistance in gastric cancer. Tumour. Biol. 2016, 37, 3527–3534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, L.; Meng, L.; Huang, Z.; Yi, L.; Yang, N.; Li, G. An analysis of the role of HnRNP C dysregulation in cancers. Biomark. Res. 2022, 10, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Xu, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Wu, X.; Cheng, Y.; et al. Dynamic FMR1 granule phase switch instructed by m6A modification contributes to maternal RNA decay. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, L.; Spatuzza, M.; D’Antoni, S.; Bonaccorso, C.M.; Trovato, C.; Musumeci, S.A.; Leopoldo, M.; Lacivita, E.; Catania, M.V.; Ciranna, L. Activation of 5-HT7 serotonin receptors reverses metabotropic glutamate receptor-mediated synaptic plasticity in wild-type and Fmr1 knockout mice, a model of Fragile X syndrome. Biol. Psychiatry 2012, 72, 924–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasarman, F.; Brunel-Guitton, C.; Antonicka, H.; Wai, T.; Shoubridge, E.A. LRPPRC and SLIRP interact in a ribonucleoprotein complex that regulates posttranscriptional gene expression in mitochondria. Mol. Biol. Cell 2010, 21, 1315–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzzenente, B.; Metodiev, M.D.; Wredenberg, A.; Bratic, A.; Park, C.B.; Cámara, Y.; Milenkovic, D.; Zickermann, V.; Wibom, R.; Hultenby, K.; et al. LRPPRC is necessary for polyadenylation and coordination of translation of mitochondrial mRNAs. EMBO J. 2012, 31, 443–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, S.; He, C.; Xue, P.; Zhang, L.; He, Z.; Zang, L.; Feng, B.; Sun, J.; Zheng, M. METTL14 suppresses proliferation and metastasis of colorectal cancer by down-regulating oncogenic long non-coding RNA XIST. Mol. Cancer 2020, 19, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozdarani, H.; Ezzatizadeh, V.; Rahbar Parvaneh, R. The emerging role of the long non-coding RNA HOTAIR in breast cancer development and treatment. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razak, M.A.; Begum, P.S.; Viswanath, B.; Rajagopal, S. Multifarious Beneficial Effect of Nonessential Amino Acid, Glycine: A Review. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2017, 2017, 1716701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.J.; Yu, Z.H.; Zhang, R.Y.; Zhang, Z.Y. Protein tyrosine phosphatases as potential therapeutic targets. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2014, 35, 1227–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xiao, W.; He, Y.; Wen, Z.; Cheng, S.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y. Novel Insights Into the Multifaceted Functions of RNA n6-Methyladenosine Modification in Degenerative Musculoskeletal Diseases. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 766020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.Z.; Liu, Y.D.; Li, J.; Chen, M.T.; Huang, M.; Wang, F.; Yang, Q.S.; Yuan, J.H.; Sun, S.H. METTL16 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression through downregulating RAB11B-AS1 in an m6A-dependent manner. Cell Mol. Biol. Lett. 2022, 27, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedoui, S.; Herold, M.J.; Strasser, A. Emerging connectivity of programmed cell death pathways and its physiological implications. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 678–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galluzzi, L.; Vitale, I.; Aaronson, S.A.; Abrams, J.M.; Adam, D.; Agostinis, P.; Alnemri, E.S.; Altucci, L.; Amelio, I.; Andrews, D.W.; et al. Molecular mechanisms of cell death: Recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2018. Cell Death Differ. 2018, 25, 486–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tower, J. Programmed cell death in aging. Ageing Res. Rev. 2015, 23, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.; Wang, J.; Wu, Z.; Miao, Y.; Chen, C.; Li, R.; Li, J.; Xing, H. METTL3-mediated M6A methylation modification is involved in colistin-induced nephrotoxicity through apoptosis mediated by Keap1/Nrf2 signaling pathway. Toxicology 2021, 462, 152961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Kang, X.; Pan, L.; Liu, C.; Liang, X.; Chu, J.; Dong, S.; Li, Y.; Liu, Q.; et al. Mettl3-mediated mRNA m6A modification controls postnatal liver development by modulating the transcription factor Hnf4a. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Liu, J.; Zhao, S.; Tian, F. N6-Methyladenosine METTL3 Modulates the Proliferation and Apoptosis of Lens Epithelial Cells in Diabetic Cataract. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2020, 20, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Zhang, H.; Wang, S. Vitamin D3 Suppresses Human Cytomegalovirus-Induced Vascular Endothelial Apoptosis via Rectification of Paradoxical m6A Modification of Mitochondrial Calcium Uniporter mRNA, Which Is Regulated by METTL3 and YTHDF3. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 861734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Li, Y.; Chen, J.P.; Li, D.Z.; Jiang, Q.; Wu, T.; Zhou, X.Z. Oxygen glucose deprivation/re-oxygenation-induced neuronal cell death is associated with Lnc-D63785 m6A methylation and miR-422a accumulation. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Zhu, H.; Liu, H.; Wang, M.; Chu, H.; Zhang, Z. METTL3 regulates PM(2.5)-induced cell injury by targeting OSGIN1 in human airway epithelial cells. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 415, 125573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães-Teixeira, C.; Lobo, J.; Miranda-Gonçalves, V.; Barros-Silva, D.; Martins-Lima, C.; Monteiro-Reis, S.; Sequeira, J.P.; Carneiro, I.; Correia, M.P.; Henrique, R.; et al. Downregulation of m6A writer complex member METTL14 in bladder urothelial carcinoma suppresses tumor aggressiveness. Mol. Oncol. 2022, 16, 1841–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, L.; Li, S.; Li, S.; Wang, R.; Zhao, M.; Liu, X. FTO inhibits oxidative stress by mediating m6A demethylation of Nrf2 to alleviate cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 79, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, F.; Tang, X.; Tang, C.; Hua, Z.; Ke, M.; Wang, C.; Zhao, J.; Gao, S.; Jurczyszyn, A.; Janz, S.; et al. HNRNPA2B1 promotes multiple myeloma progression by increasing AKT3 expression via m6A-dependent stabilization of ILF3 mRNA. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 14, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, Y.; Lin, Z.; Wan, A.; Chen, H.; Liang, H.; Sun, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Xiong, X.F.; Wei, B.; et al. RNA N6-methyladenosine demethylase FTO promotes breast tumor progression through inhibiting BNIP3. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Yue, H.; Cheng, Y.; Ding, Z.; Xu, Z.; Lv, C.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Yin, C.; Hao, H.; et al. ALKBH5-mediated m6A demethylation of KCNK15-AS1 inhibits pancreatic cancer progression via regulating KCNK15 and PTEN/AKT signaling. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, D.; Guo, J.; Wu, Y.; Yang, L.; Wang, X.; Du, J.; Dai, J.; Chen, W.; Gong, K.; Miao, S.; et al. m6A demethylase ALKBH5 inhibits tumor growth and metastasis by reducing YTHDFs-mediated YAP expression and inhibiting miR-107/LATS2-mediated YAP activity in NSCLC. Mol. Cancer 2020, 19, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, J.; Hou, Y.; Chen, Q.; Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, E.; Gu, H.; Xu, R.; Liu, Y.; Cao, W.; et al. RNA demethylase ALKBH5 promotes tumorigenesis in multiple myeloma via TRAF1-mediated activation of NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways. Oncogene 2022, 41, 400–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Xiong, R.; Zhou, J.; Guan, X.; Jiang, G.; Chen, Y.; Yang, Q. Involvement of m6A regulatory factor IGF2BP1 in malignant transformation of human bronchial epithelial Beas-2B cells induced by tobacco carcinogen NNK. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2022, 436, 115849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, P.; Liu, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhong, X.; Zhong, C. YTHDF1 Attenuates TBI-Induced Brain-Gut Axis Dysfunction in Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einstein, J.M.; Perelis, M.; Chaim, I.A.; Meena, J.K.; Nussbacher, J.K.; Tankka, A.T.; Yee, B.A.; Li, H.; Madrigal, A.A.; Neill, N.J.; et al. Inhibition of YTHDF2 triggers proteotoxic cell death in MYC-driven breast cancer. Mol. Cell 2021, 81, 3048–3064.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.W.; Weng, J.H.; Lee, W.X.; Hu, Y.; Gu, L.; Cho, S.; Lee, G.; Binari, R.; Li, C.; Cheng, M.E.; et al. mTORC1-chaperonin CCT signaling regulates m6A RNA methylation to suppress autophagy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2021945118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Lei, H.; He, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, A.; Ren, Z.; Liu, X.; Yan, G.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; et al. METTL14 Regulates Osteogenesis of Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells via Inducing Autophagy through m6A/IGF2BPs/Beclin-1 Signal Axis. Stem. Cells Transl. Med. 2022, 11, 987–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Liu, H.; Song, N.; Liang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Chen, J.; Ning, Y.; Hu, J.; Fang, Y.; Teng, J.; et al. METTL14 aggravates podocyte injury and glomerulopathy progression through N6-methyladenosine-dependent downregulating of Sirt1. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.M.; Zhang, S.M.; Luo, H.; Jiang, D.S.; Huo, B.; Zhong, X.; Feng, X.; Cheng, W.; Chen, Y.; Feng, G.; et al. Methyltransferase-like 3 suppresses phenotypic switching of vascular smooth muscle cells by activating autophagosome formation. Cell Prolif. 2023, 56, e13386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Z.; Cao, J.; Yao, J.; Fan, X.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, M.; Duan, Q.; Han, B.; Duan, S. KDM1A-mediated upregulation of METTL3 ameliorates Alzheimer’s disease via enhancing autophagic clearance of p-Tau through m6A-dependent regulation of STUB1. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2023, 195, 343–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Ni, Y.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, R.; Xu, J.; Yang, H.; Hu, Y.; Qiu, J.; Pu, L.; Tang, J.; et al. HIF-1α-induced expression of m6A reader YTHDF1 drives hypoxia-induced autophagy and malignancy of hepatocellular carcinoma by promoting ATG2A and ATG14 translation. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Gao, D.; Wu, Y.; Sun, L.; Chen, J.; Chen, J.; Huang, X.; Yang, J.; Li, S. YTHDF1 Protects Auditory Hair Cells from Cisplatin-Induced Damage by Activating Autophagy via the Promotion of ATG14 Translation. Mol. Neurobiol. 2022, 59, 7134–7151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Gong, Y.; Wang, X.; He, W.; Wu, L.; Zhang, L.; Xiong, L.; Huang, Y.; Su, L.; Shi, P.; et al. METTL3-m6A-Rubicon axis inhibits autophagy in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Mol. Ther. 2022, 30, 932–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, W.; Dian, M.; Zhou, Y.; Zhong, Q.; Pang, W.; Li, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, J.; Lin, X.; Luo, R.; et al. Autophagy induction promoted by m6A reader YTHDF3 through translation upregulation of FOXO3 mRNA. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Lin, W.J.; Ren, M.; Qiu, J.; Yang, C.; Wang, X.; Li, N.; Zeng, T.; Sun, K.; You, L.; et al. m6A reader YTHDC1 modulates autophagy by targeting SQSTM1 in diabetic skin. Autophagy 2022, 18, 1318–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Shao, J.; Zhang, F.; Yin, G.; Chen, A.; Zhang, Z.; Zheng, S. N6-methyladenosine modification regulates ferroptosis through autophagy signaling pathway in hepatic stellate cells. Redox Biol. 2021, 47, 102151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, M.; Guo, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Shao, J.; Zhang, F.; Xu, X.; Yin, G.; Wang, S.; et al. m6A methylation is required for dihydroartemisinin to alleviate liver fibrosis by inducing ferroptosis in hepatic stellate cells. Free Radic Biol. Med. 2022, 182, 246–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Yi, X.; He, Y.; Huo, B.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; Zhong, X.; Li, R.; et al. Targeting Ferroptosis as a Novel Approach to Alleviate Aortic Dissection. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 18, 4118–4134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, S.; Ma, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Lu, C.; Yang, F.; Jiang, N.; Ge, J.; Ju, H.; Zhong, C.; Wang, J.; et al. METTL14 promotes doxorubicin-induced cardiomyocyte ferroptosis by regulating the KCNQ1OT1-miR-7-5p-TFRC axis. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2023, 39, 1015–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Z.; Yang, G.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Q.; Liu, G.; Liu, P.; Xu, L.; Wang, J.; Yan, Z.; Han, H.; et al. Hypoxia blocks ferroptosis of hepatocellular carcinoma via suppression of METTL14 triggered YTHDF2-dependent silencing of SLC7A11. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2021, 25, 10197–10212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Y.; Han, M.; Cao, K.; Li, Q.; Pang, J.; Dou, L.; Liu, S.; Shi, Z.; Yan, F.; Feng, S. Gold Nanorods Exhibit Intrinsic Therapeutic Activity via Controlling N6-Methyladenosine-Based Epitranscriptomics in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 17689–17704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.M.; Li, Z.X.; Wu, Y.H.; Shi, Z.L.; Mi, J.L.; Hu, K.; Wang, R.S. m6A demethylase FTO renders radioresistance of nasopharyngeal carcinoma via promoting OTUB1-mediated anti-ferroptosis. Transl. Oncol. 2023, 27, 101576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, H.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Cheng, C.; Lin, J.; Yang, Y.; Lu, L.; Xiang, Q.; Bian, T.; Liu, Q. N6-Methyladenosine-modified circSAV1 triggers ferroptosis in COPD through recruiting YTHDF1 to facilitate the translation of IREB2. Cell Death Differ. 2023, 30, 1293–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Yu, Y.; Wang, R.; Chen, Y.; Tang, J. mRNA-Modified FUS/NRF2 Signalling Inhibits Ferroptosis and Promotes Prostate Cancer Growth. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2022, 2022, 8509626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, H.; Tan, H.; Hu, Y.; Wang, R.; Cai, P.; Huang, B.; Shao, X.; Yan, M.; Yin, C.; Zhang, Y. The m6A Reader YTHDF1 Promotes Lung Carcinoma Progression via Regulating Ferritin Mediate Ferroptosis in an m6A-Dependent Manner. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Gao, T.; Pang, B.; Su, X.; Guo, C.; Zhang, R.; Pang, Q. RNA binding protein NKAP protects glioblastoma cells from ferroptosis by promoting SLC7A11 mRNA splicing in an m6A-dependent manner. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, F.; An, C.; Liu, C.; Hu, Y.; Su, Y.; Guo, Z.; Che, H.; Ge, S. FTO represses NLRP3-mediated pyroptosis and alleviates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury via inhibiting CBL-mediated ubiquitination and degradation of β-catenin. FASEB J. 2023, 37, e22964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, Q.; He, S.; Bai, J.; Ma, C.; Zhang, L.; Guan, X.; Yuan, H.; Li, Y.; Zhu, X.; et al. LncRNA FENDRR with m6A RNA methylation regulates hypoxia-induced pulmonary artery endothelial cell pyroptosis by mediating DRP1 DNA methylation. Mol. Med. 2022, 28, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Li, T.; Shi, L.; Miao, J.; Guo, Y.; Chen, Y. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells deliver exogenous miR-26a-5p via exosomes to inhibit nucleus pulposus cell pyroptosis through METTL14/NLRP3. Mol. Med. 2021, 27, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Xu, X.; Yang, J.; Chen, W.; Zhao, J.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Huang, W.; Zhang, H. BPDE exposure promotes trophoblast cell pyroptosis and induces miscarriage by up-regulating lnc-HZ14/ZBP1/NLRP3 axis. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 455, 131543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, J.; Xu, B.; Shi, X.; Pan, Q.; Tao, Q. WTAP-mediated N6-methyladenosine modification of NLRP3 mRNA in kidney injury of diabetic nephropathy. Cell Mol. Biol. Lett. 2022, 27, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Guan, X.; Liu, W.; Zhu, Z.; Jin, H.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, M.; Xu, C.; Tang, X.; et al. YTHDF1 alleviates sepsis by upregulating WWP1 to induce NLRP3 ubiquitination and inhibit caspase-1-dependent pyroptosis. Cell Death Discov. 2022, 8, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zha, X.; Xi, X.; Fan, X.; Ma, M.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y. Overexpression of METTL3 attenuates high-glucose induced RPE cell pyroptosis by regulating miR-25-3p/PTEN/Akt signaling cascade through DGCR8. Aging 2020, 12, 8137–8150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.S.; Li, B.W.; Wang, L.L.; Li, N.; Lin, H.M.; Zhang, J.; Du, N.; Zhu, Y.Q.; Wu, X.; Hu, C.M.; et al. Kupffer cell pyroptosis mediated by METTL3 contributes to the progression of alcoholic steatohepatitis. FASEB J. 2023, 37, e22965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Li, H.; Hu, D.; Wang, Y.; Shao, W.; Zhong, J.; Yang, S.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J. Insights into N6-methyladenosine and programmed cell death in cancer. Mol. Cancer 2022, 21, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Zhang, D.; Zhai, S.; Wu, H.; Liu, H. METTL3–METTL14 complex induces necroptosis and inflammation of vascular smooth muscle cells via promoting N6 methyladenosine mRNA methylation of receptor-interacting protein 3 in abdominal aortic aneurysms. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 2023, 17, 897–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, H.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Guan, Z.; Du, J.; Jin, K. Tumor-Associated Macrophages Promote Oxaliplatin Resistance via METTL3-Mediated m6A of TRAF5 and Necroptosis in Colorectal Cancer. Mol. Pharm. 2021, 18, 1026–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandeya, A.; Kanneganti, T.D. Therapeutic potential of PANoptosis: Innate sensors, inflammasomes, and RIPKs in PANoptosomes. Trends Mol. Med. 2024, 30, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Yang, Y.; Meng, X.; Li, J.; Liu, X.; Liu, H. PANoptosis: Mechanisms, biology, and role in disease. Immunol. Rev. 2024, 321, 246–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Wang, X.; Lin, F.; Li, W.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, F.; Yang, H.; Rao, M.; Li, Y.; Liang, H.; et al. MiR-29a-3p Improves Acute Lung Injury by Reducing Alveolar Epithelial Cell PANoptosis. Aging Dis. 2022, 13, 899–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Guo, J.; Hu, M.; Gao, Y.; Huang, L. Icaritin Exacerbates Mitophagy and Synergizes with Doxorubicin to Induce Immunogenic Cell Death in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 4816–4828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Gao, M.; Zhang, J.; Fu, Y. IL5RA as an immunogenic cell death-related predictor in progression and therapeutic response of multiple myeloma. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Tian, R.; Yu, L.; Bian, S.; Chen, Y.; Yin, B.; Luan, Y.; Chen, S.; Fan, Z.; Yan, R.; et al. Overcoming therapeutic resistance in oncolytic herpes virotherapy by targeting IGF2BP3-induced NETosis in malignant glioma. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, L.; Wu, Z. Identification and validation of oxeiptosis-associated lncRNAs and prognosis-related signature genes to predict the immune status in uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma. Aging 2023, 15, 4236–4252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, J.; Yu, P.; Feng, J.; Xu, G.E.; Zhao, X.; Wang, T.; Lehmann, H.I.; Li, G.; Sluijter, J.P.G.; et al. METTL14 is required for exercise-induced cardiac hypertrophy and protects against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Feng, X.; Zhang, H.; Luo, Y.; Huang, J.; Lin, M.; Jin, J.; Ding, X.; Wu, S.; Huang, H.; et al. METTL3 and ALKBH5 oppositely regulate m6A modification of TFEB mRNA, which dictates the fate of hypoxia/reoxygenation-treated cardiomyocytes. Autophagy 2019, 15, 1419–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Li, S.; Wang, F. Mechanism of METTL3-Mediated m6A Modification in Cardiomyocyte Pyroptosis and Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2023, 37, 435–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Yin, D.; Zhang, W.; Xu, Y. The role and mechanism of FTO in pulmonary vessels. Biotechnol. Genet. Eng. Rev. 2023, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, K.; Liu, Z.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Fan, Y.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, F. Targeted Demethylation of the TGFβ1 mRNA Promotes Myoblast Proliferation via Activating the SMAD2 Signaling Pathway. Cells 2023, 12, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Mei, C.; Ma, X.; Du, J.; Wang, J.; Zan, L. m6A Methylases Regulate Myoblast Proliferation, Apoptosis and Differentiation. Animals 2022, 12, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Lin, H.; Huang, X.; Weng, J.; Peng, F.; Wu, S. METTL14 suppresses pyroptosis and diabetic cardiomyopathy by downregulating TINCR lncRNA. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.J.; Huang, J.Y.; Huang, J.Q.; Deng, J.Y.; Shangguan, X.H.; Chen, A.Z.; Chen, L.T.; Wu, W.H. Metformin attenuates multiple myeloma cell proliferation and encourages apoptosis by suppressing METTL3-mediated m6A methylation of THRAP3, RBM25, and USP4. Cell Cycle 2023, 22, 986–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, F.; Ye, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Ma, S.; Tan, Y.; Mao, Y.; Luo, Z. METTL3 facilitates multiple myeloma tumorigenesis by enhancing YY1 stability and pri-microRNA-27 maturation in m6A-dependent manner. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2023, 39, 2033–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Yang, Z.; Li, Y.; Long, X. m6A methyltransferase METTL3 facilitates multiple myeloma cell growth through the m6A modification of BZW2. Ann. Hematol. 2023, 102, 1801–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Yao, L.; Yin, H.; Teng, Y.; Hong, M.; Wu, Q. ALKBH5 Promotes Multiple Myeloma Tumorigenicity through inducing m6A-demethylation of SAV1 mRNA and Myeloma Stem Cell Phenotype. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 18, 2235–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Song, Y.; Liao, Z.; Wang, K.; Luo, R.; Lu, S.; Zhao, K.; Feng, X.; Liang, H.; Ma, L.; et al. Bone-derived mesenchymal stem cells alleviate compression-induced apoptosis of nucleus pulposus cells by N6 methyladenosine of autophagy. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Cai, Z.; Yang, C.; Luo, Z.; Bao, X. ALKBH5 regulates STAT3 activity to affect the proliferation and tumorigenicity of osteosarcoma via an m6A-YTHDF2-dependent manner. EBioMedicine 2022, 80, 104019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, C.; Guo, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Quan, L. HNRNPA2B1-mediated m6A modification of TLR4 mRNA promotes progression of multiple myeloma. J. Transl. Med. 2022, 20, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, X.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, X.; Ding, S.; Zheng, Q.; Zhang, M.; Yang, J.; Ma, Y.; et al. ALKBH5-mediated m6A demethylation of HS3ST3B1-IT1 prevents osteoarthritis progression. iScience 2023, 26, 107838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Z.; Jiang, T.; Zheng, W.; Zhang, J.; Li, A.; Lu, C.; Liu, W. N6-methyladenosine (m6A) methyltransferase WTAP-mediated miR-92b-5p accelerates osteoarthritis progression. Cell Commun. Signal. 2023, 21, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Li, M.; Jiang, L.; Jiang, R.; Fu, B. METTL3 promotes experimental osteoarthritis development by regulating inflammatory response and apoptosis in chondrocyte. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 516, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Gong, W.; Shao, X.; Shi, T.; Zhang, L.; Dong, J.; Shi, Y.; Shen, S.; Qin, J.; Jiang, Q.; et al. METTL3-mediated m6A modification of ATG7 regulates autophagy-GATA4 axis to promote cellular senescence and osteoarthritis progression. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2022, 81, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Xu, X.; Wang, R.; Chen, W.; Qin, K.; Yan, J. Chondroprotective effects of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes in osteoarthritis. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2024, 56, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Lin, Y.; Wei, B.; Hu, X.; Xu, L.; Zhang, W.; Lu, J. N6-methyladenosine-modified circRNA RERE modulates osteoarthritis by regulating β-catenin ubiquitination and degradation. Cell Prolif. 2023, 56, e13297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, D.; Zhang, J.; Yang, J.; Lv, Q.; Zhong, C. Overexpression of FTO alleviates osteoarthritis by regulating the processing of miR-515-5p and the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB axis. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 114, 109524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittig, J.C.; Bickels, J.; Priebat, D.; Jelinek, J.; Kellar-Graney, K.; Shmookler, B.; Malawer, M.M. Osteosarcoma: A multidisciplinary approach to diagnosis and treatment. Am. Fam. Physician 2002, 65, 1123–1132. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Yang, C.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, T.; Yu, J. Silencing METTL3 inhibits the proliferation and invasion of osteosarcoma by regulating ATAD2. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 125, 109964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, X.; Wu, W.; Yang, L.; Dong, J.; Liu, B.; Guo, J.; Chen, J.; Guo, B.; Cao, W.; Jiang, Q. ZBTB7C m6A modification incurred by METTL3 aberration promotes osteosarcoma progression. Transl. Res. 2023, 259, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, Z.; Chen, L.; Zhao, J. m6A-dependent up-regulation of DRG1 by METTL3 and ELAVL1 promotes growth, migration, and colony formation in osteosarcoma. Biosci. Rep. 2020, 40, BSR20200282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Shu, W.; Liu, T.; Li, Q.; Gong, M. Analysis of the function and mechanism of DIRAS1 in osteosarcoma. Tissue Cell 2022, 76, 101794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, N.; Huang, Z.; Wang, W. METTL14 Overexpression Promotes Osteosarcoma Cell Apoptosis and Slows Tumor Progression via Caspase 3 Activation. Cancer Manag. Res. 2020, 12, 12759–12767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Yan, G.; He, M.; Lei, H.; Li, L.; Wang, Y.; He, X.; Li, G.; Wang, Q.; Gao, Y.; et al. ALKBH5 suppresses tumor progression via an m6A-dependent epigenetic silencing of pre-miR-181b-1/YAP signaling axis in osteosarcoma. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, H.J.; Gu, W.X.; Duan, G.; Chen, H.L. Fat mass and obesity associated (FTO)-mediated N6-methyladenosine modification of Krüppel-like factor 3 (KLF3) promotes osteosarcoma progression. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 8038–8050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, D.; Ge, S.; Li, M. MiR-451a promotes cell growth, migration and EMT in osteosarcoma by regulating YTHDC1-mediated m6A methylation to activate the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. J. Bone Oncol. 2022, 33, 100412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Tao, C.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Q.; Chen, J. N6-methyladenosine modification of TGM2 mRNA contributes to the inhibitory activity of sarsasapogenin in rheumatoid arthritis fibroblast-like synoviocytes. Phytomedicine 2022, 95, 153871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Ling, M.; Li, X.; Tan, X. METTL14 promotes fibroblast-like synoviocytes activation via the LASP1/SRC/AKT axis in rheumatoid arthritis. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2023, 324, C1089–C1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, S.; Zeng, F.; Chen, R.; Li, M. SIAH1 promotes senescence and apoptosis of nucleus pulposus cells to exacerbate disc degeneration through ubiquitinating XIAP. Tissue Cell 2022, 76, 101820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.B.; Shi, G.X.; Liu, T.; Li, B.; Jiang, S.D.; Zheng, X.F.; Jiang, L.S. Oxidative Stress Aggravates Apoptosis of Nucleus Pulposus Cells through m6A Modification of MAT2A Pre-mRNA by METTL16. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2022, 2022, 4036274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, M.; Luo, J.; Cao, H.; Li, Y.; Chen, L.; Liu, G. METTL14 represses osteoclast formation to ameliorate osteoporosis via enhancing GPX4 mRNA stability. Environ. Toxicol. 2023, 38, 2057–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.B.; Huang, G.; Tu, J.; Lv, D.M.; Jin, Q.L.; Chen, J.K.; Zou, Y.T.; Lee, D.F.; Shen, J.N.; Xie, X.B. METTL14-mediated epitranscriptome modification of MN1 mRNA promote tumorigenicity and all-trans-retinoic acid resistance in osteosarcoma. EBioMedicine 2022, 82, 104142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Category | Enzyme | Characteristics and Functions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Writers | METTL3 | Catalytic subunit, acts as the catalytic core | [27] |

| METTL14 | Catalytic subunit, acts as an RNA-binding platform and promotes RNA binding | [29] | |

| WTAP | Regulatory subunit, regulates METTL3/METTL14 complex locates and binds mRNA | [30] | |

| METTL16 | Regulatory subunit, regulates intracellular S-adenosyl methionine levels by dynamically regulating the m6A modification of the small nuclear RNA, U6, and target mRNAs | [51] | |

| VIRMA | Regulatory subunit, recruits the catalytic core component METTL3/METTL14/WTAP to guide regioselective methylation | [31] | |

| RBM15/RBM15B | Regulatory subunit, consistently methylates adenosine in adjacent m6A residues by binding to the m6A–methylation complex and recruiting it to RNA molecules | [28] | |

| ZC3H13 | Regulatory subunit, anchors WTAP, a virilized protein, and Hakai to the nucleus to promote m6A methylation | [28] | |

| Erasers | FTO | Catalyzes the demethylation of m6A modifications on the mRNA | [33,34] |

| ALKBH5 | Catalyzes the demethylation of m6A modifications on the mRNA | [33,34] | |

| Readers | YTHDC1 | Regulates the mode of alternative splicing; promotes the nuclear exit of m6A-modified mRNA | [37,38] |

| YTHDC2 | Enhances the translation efficiency or decreases the abundance of its substrate | [37,38] | |

| YTHDF1 | Promotes the translation efficiency of m6A-modified RNA substrates | [37,38] | |

| YTHDF2 | Accelerates the degradation of the m6A-modified transcripts; regulates mRNA stability | [37,38] | |

| YTHDF3 | Cooperates with YTHDF1 to regulate mRNA translation efficiency; mediates mRNA degradation | [37,38] | |

| HNRNPC | Mediates the alternative splicing of m6A-modified transcripts | [40,41] | |

| IGF2BP1/2/3 | Cooperates with eIF3 to stabilize target genes and initiate the translation process | [39] | |

| eIF3 | Cooperates with IGF2BP1/2/3 to stabilize target genes and initiate the translation process | [37,38] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Han, J.; Wang, C.; Yang, H.; Luo, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.-A. Novel Insights into the Links between N6-Methyladenosine and Regulated Cell Death in Musculoskeletal Diseases. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 514. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom14050514

Han J, Wang C, Yang H, Luo J, Zhang X, Zhang X-A. Novel Insights into the Links between N6-Methyladenosine and Regulated Cell Death in Musculoskeletal Diseases. Biomolecules. 2024; 14(5):514. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom14050514

Chicago/Turabian StyleHan, Juanjuan, Cuijing Wang, Haolin Yang, Jiayi Luo, Xiaoyi Zhang, and Xin-An Zhang. 2024. "Novel Insights into the Links between N6-Methyladenosine and Regulated Cell Death in Musculoskeletal Diseases" Biomolecules 14, no. 5: 514. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom14050514

APA StyleHan, J., Wang, C., Yang, H., Luo, J., Zhang, X., & Zhang, X.-A. (2024). Novel Insights into the Links between N6-Methyladenosine and Regulated Cell Death in Musculoskeletal Diseases. Biomolecules, 14(5), 514. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom14050514