Effects of NAD+ in Caenorhabditis elegans Models of Neuronal Damage

Abstract

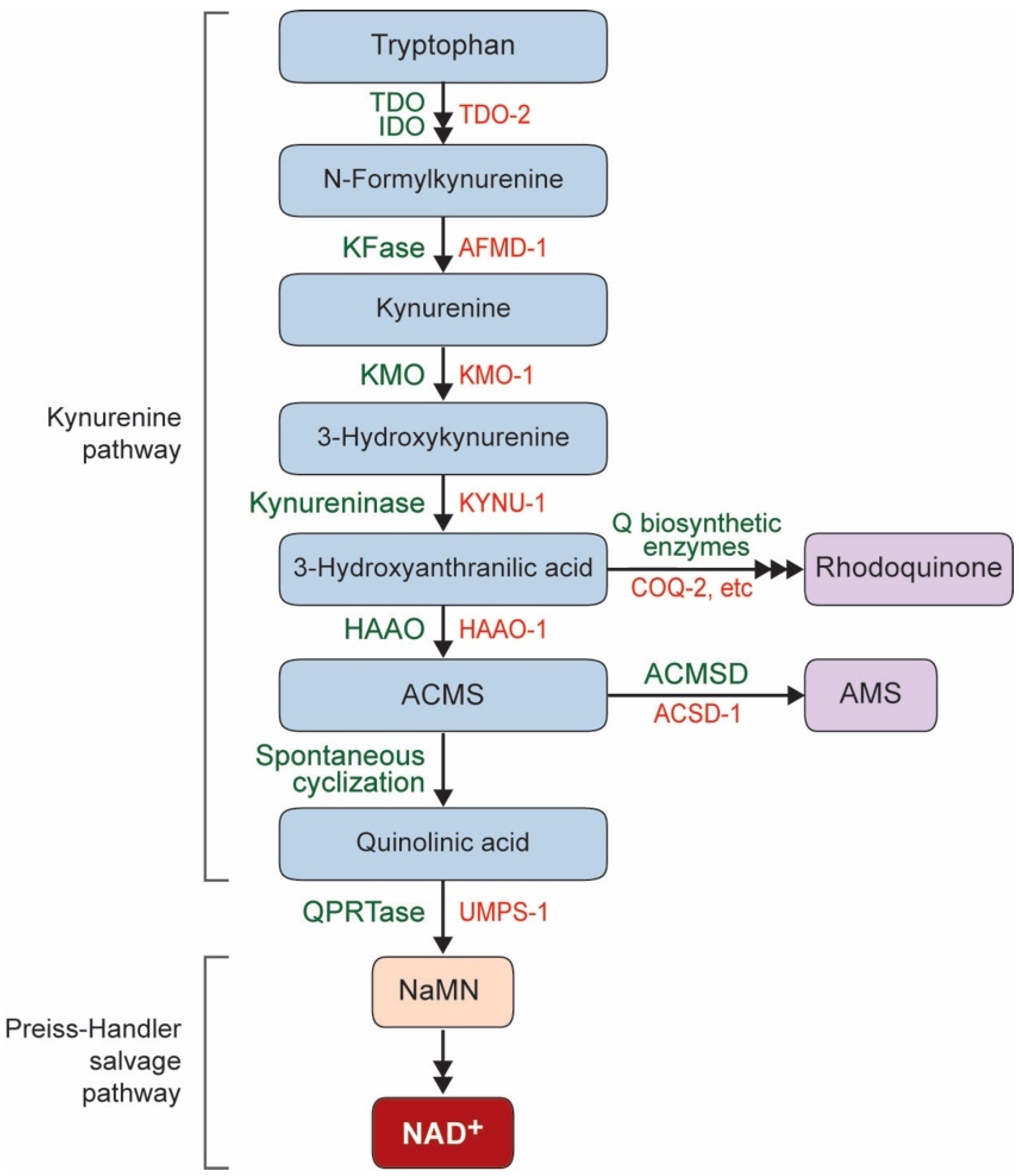

1. NAD+ Biosynthesis Pathway in C. elegans

2. Neuroprotective Effect of NAD+ in C. elegans

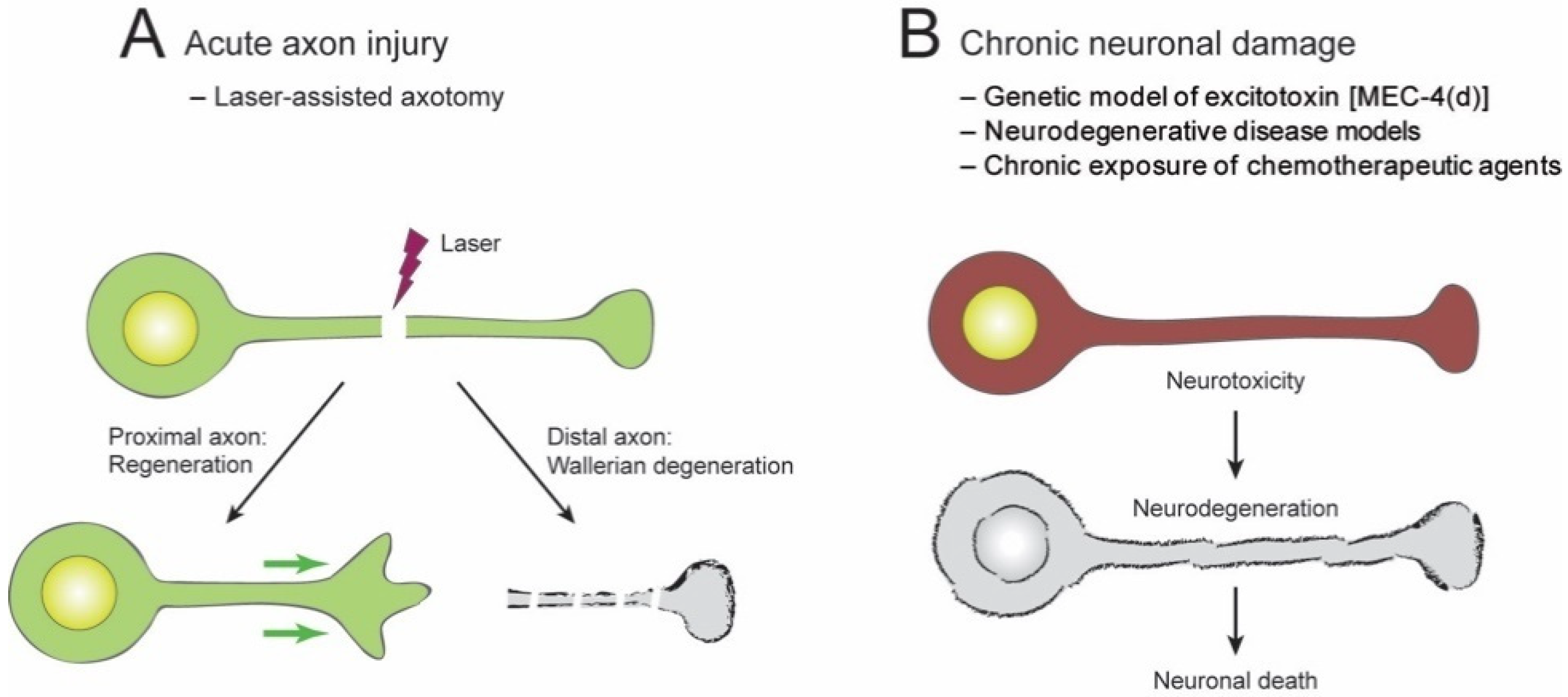

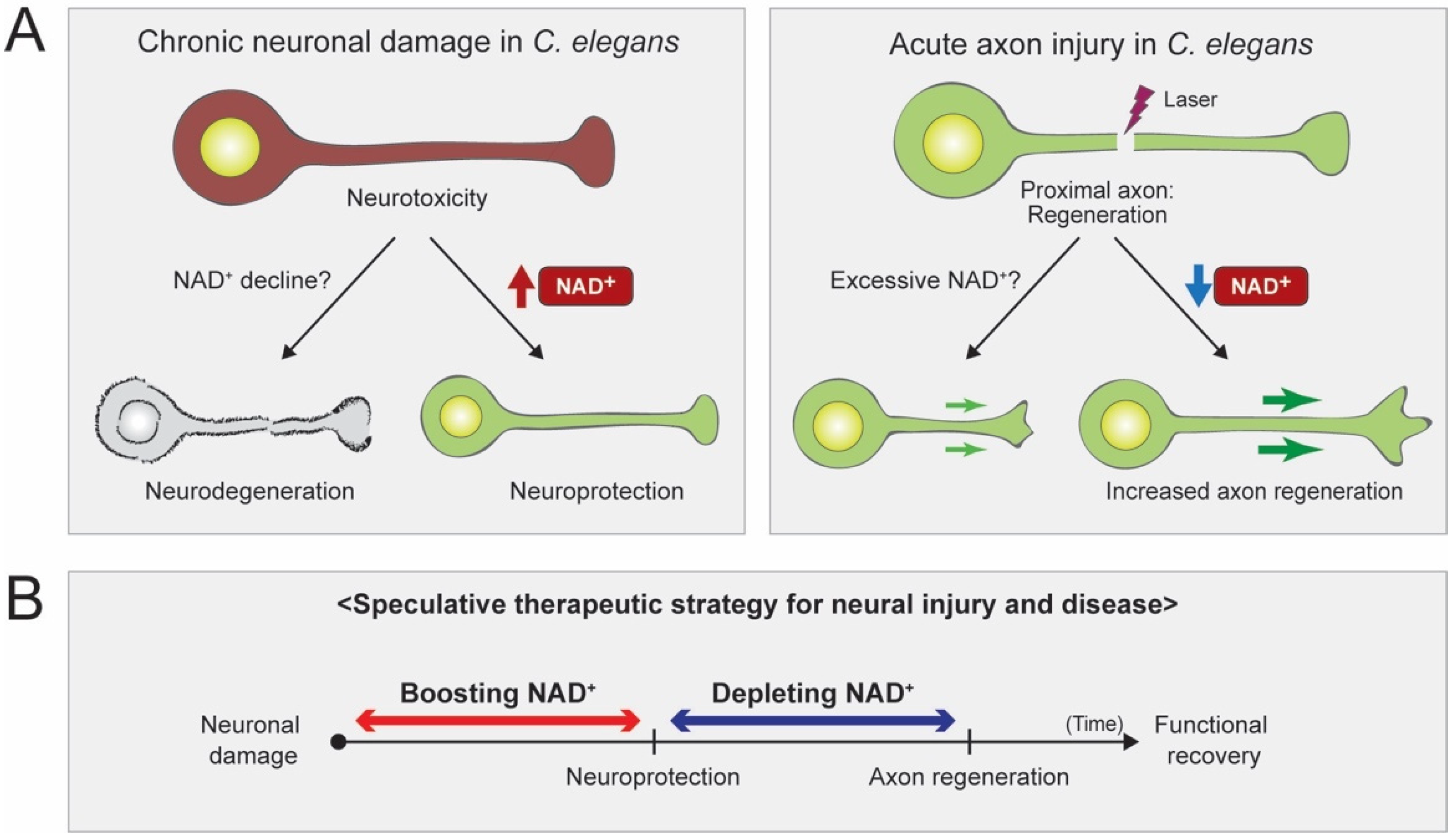

2.1. Acute Axon Injuries

2.2. Chronic Injuries

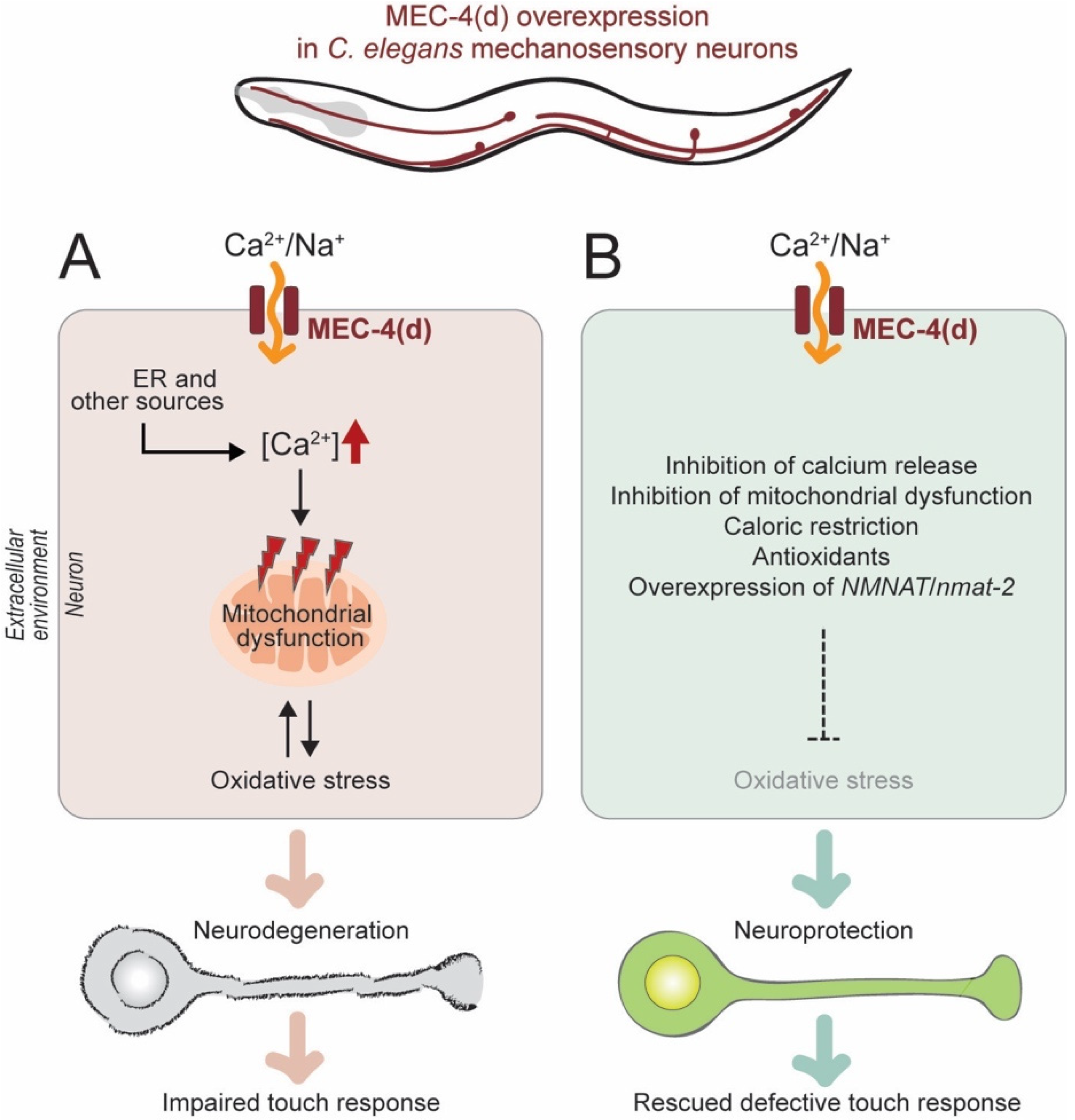

2.2.1. Genetic Model of Neuronal Excitotoxicity

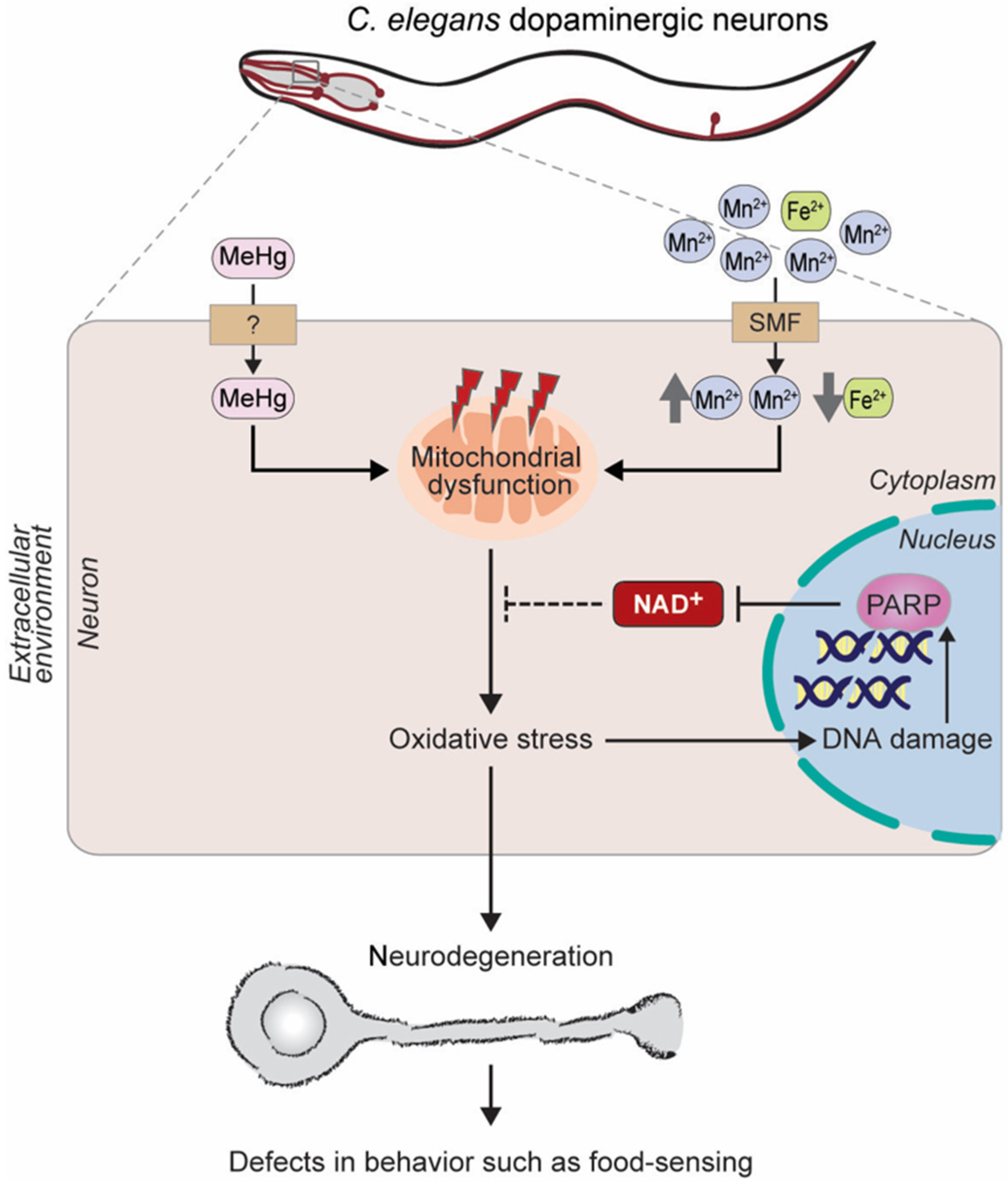

2.2.2. C. elegans Models of Neurodegenerative Diseases

Huntington’s Disease

Alzheimer’s Disease

Parkinson’s Disease

2.2.3. Chemotherapeutic Agents

3. Regulation of Axon Regeneration in C. elegans

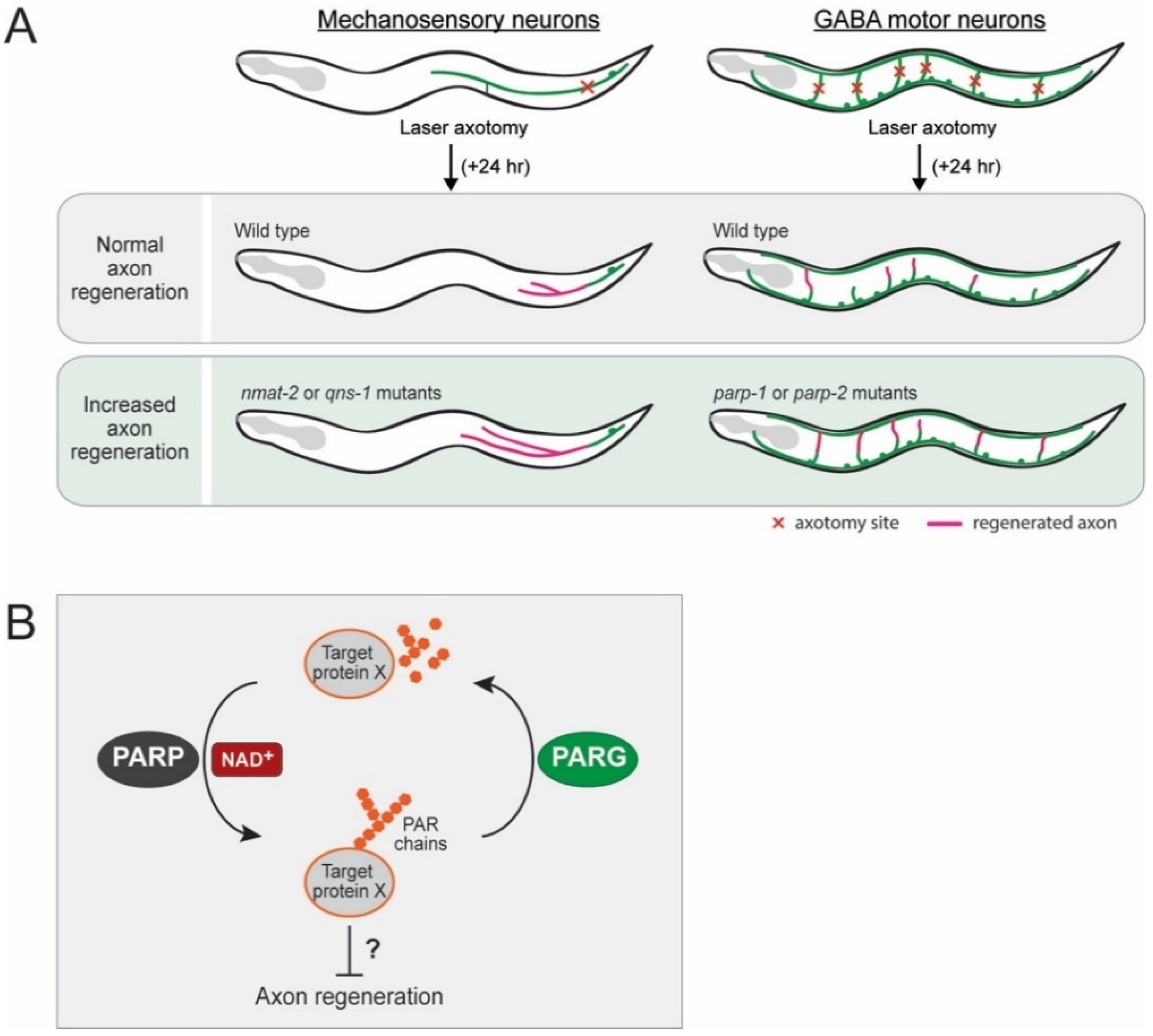

3.1. Inhibitory Role of NMNAT and NADS in Axon Regeneration

3.2. Inhibitory Role of PARPs in Axon Regeneration

4. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Canto, C.; Menzies, K.J.; Auwerx, J. NAD(+) Metabolism and the Control of Energy Homeostasis: A Balancing Act between Mitochondria and the Nucleus. Cell Metab. 2015, 22, 31–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gazzaniga, F.; Stebbins, R.; Chang, S.Z.; McPeek, M.A.; Brenner, C. Microbial NAD metabolism: Lessons from comparative genomics. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2009, 73, 529–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurnasov, O.; Goral, V.; Colabroy, K.; Gerdes, S.; Anantha, S.; Osterman, A.; Begley, T.P. NAD biosynthesis: Identification of the tryptophan to quinolinate pathway in bacteria. Chem. Biol. 2003, 10, 1195–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maddison, D.C.; Giorgini, F. The kynurenine pathway and neurodegenerative disease. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2015, 40, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magni, G.; Amici, A.; Emanuelli, M.; Orsomando, G.; Raffaelli, N.; Ruggieri, S. Enzymology of NAD+ homeostasis in man. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2004, 61, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarcz, R.; Bruno, J.P.; Muchowski, P.J.; Wu, H.Q. Kynurenines in the mammalian brain: When physiology meets pathology. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2012, 13, 465–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillemin, G.J. Quinolinic acid, the inescapable neurotoxin. FEBS J. 2012, 279, 1356–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rongvaux, A.; Andris, F.; Van Gool, F.; Leo, O. Reconstructing eukaryotic NAD metabolism. Bioessays 2003, 25, 683–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McReynolds, M.R.; Wang, W.; Holleran, L.M.; Hanna-Rose, W. Uridine monophosphate synthetase enables eukaryotic de novo NAD(+) biosynthesis from quinolinic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 11147–11153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belenky, P.; Bogan, K.L.; Brenner, C. NAD+ metabolism in health and disease. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2007, 32, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bieganowski, P.; Brenner, C. Discoveries of nicotinamide riboside as a nutrient and conserved NRK genes establish a Preiss-Handler independent route to NAD+ in fungi and humans. Cell 2004, 117, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preiss, J.; Handler, P. Biosynthesis of diphosphopyridine nucleotide. I. Identification of intermediates. J. Biol. Chem. 1958, 233, 488–492. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Preiss, J.; Handler, P. Biosynthesis of diphosphopyridine nucleotide. II. Enzymatic aspects. J. Biol. Chem. 1958, 233, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Song, S.B.; Park, J.S.; Chung, G.J.; Lee, I.H.; Hwang, E.S. Diverse therapeutic efficacies and more diverse mechanisms of nicotinamide. Metabolomics 2019, 15, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.W.; Tang, N.H.; Piggott, C.A.; Andrusiak, M.G.; Park, S.; Zhu, M.; Kurup, N.; Cherra, S.J., III; Wu, Z.; Chisholm, A.D.; et al. Expanded genetic screening in Caenorhabditis elegans identifies new regulators and an inhibitory role for NAD(+) in axon regeneration. eLife 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Collins, C.A. Mechanisms of Axonal Degeneration and Regeneration. In The Oxford Handbook of Invertebrate Neurobiology; Byrne, J.H., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 574–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llobet Rosell, A.; Neukomm, L.J. Axon death signalling in Wallerian degeneration among species and in disease. Open Biol. 2019, 9, 190118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, A. Experiments on the Section of the Glossopharyngeal and Hypoglossal Nerves of the Frog, and Observations of the Alterations Produced Thereby in the Structure of Their Primitive Fibres. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 1850, 140, 423–429. [Google Scholar]

- Raff, M.C.; Whitmore, A.V.; Finn, J.T. Axonal self-destruction and neurodegeneration. Science 2002, 296, 868–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araki, T.; Sasaki, Y.; Milbrandt, J. Increased nuclear NAD biosynthesis and SIRT1 activation prevent axonal degeneration. Science 2004, 305, 1010–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterloh, J.M.; Yang, J.; Rooney, T.M.; Fox, A.N.; Adalbert, R.; Powell, E.H.; Sheehan, A.E.; Avery, M.A.; Hackett, R.; Logan, M.A.; et al. dSarm/Sarm1 is required for activation of an injury-induced axon death pathway. Science 2012, 337, 481–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, V.H.; Lunn, E.R.; Brown, M.C.; Cahusac, S.; Gordon, S. Evidence that the Rate of Wallerian Degeneration is Controlled by a Single Autosomal Dominant Gene. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1990, 2, 408–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunn, E.R.; Perry, V.H.; Brown, M.C.; Rosen, H.; Gordon, S. Absence of Wallerian Degeneration does not Hinder Regeneration in Peripheral Nerve. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1989, 1, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conforti, L.; Gilley, J.; Coleman, M.P. Wallerian degeneration: An emerging axon death pathway linking injury and disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2014, 15, 394–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essuman, K.; Summers, D.W.; Sasaki, Y.; Mao, X.; Yim, A.K.Y.; DiAntonio, A.; Milbrandt, J. TIR Domain Proteins Are an Ancient Family of NAD(+)-Consuming Enzymes. Curr. Biol. 2018, 28, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Summers, D.W.; Gibson, D.A.; DiAntonio, A.; Milbrandt, J. SARM1-specific motifs in the TIR domain enable NAD+ loss and regulate injury-induced SARM1 activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E6271–E6280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerdts, J.; Brace, E.J.; Sasaki, Y.; DiAntonio, A.; Milbrandt, J. SARM1 activation triggers axon degeneration locally via NAD(+) destruction. Science 2015, 348, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilley, J.; Coleman, M.P. Endogenous Nmnat2 is an essential survival factor for maintenance of healthy axons. PLoS Biol. 2010, 8, e1000300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Y.; Parrish, J.Z.; He, R.; Zhai, R.G.; Kim, M.D. Nmnat exerts neuroprotective effects in dendrites and axons. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2011, 48, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, A.L.A.; Meelkop, E.; Linton, C.; Giordano-Santini, R.; Sullivan, R.K.; Donato, A.; Nolan, C.; Hall, D.H.; Xue, D.; Neumann, B.; et al. The Apoptotic Engulfment Machinery Regulates Axonal Degeneration in C. elegans Neurons. Cell Rep. 2016, 14, 1673–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvadores, N.; Sanhueza, M.; Manque, P.; Court, F.A. Axonal Degeneration during Aging and Its Functional Role in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaron, A.; Schuldiner, O. Common and Divergent Mechanisms in Developmental Neuronal Remodeling and Dying Back Neurodegeneration. Curr. Biol. 2016, 26, R628–R639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, J.B. The ‘dying back’ process. A common denominator in many naturally occurring and toxic neuropathies. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 1979, 103, 659–664. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ankarcrona, M.; Dypbukt, J.M.; Bonfoco, E.; Zhivotovsky, B.; Orrenius, S.; Lipton, S.A.; Nicotera, P. Glutamate-induced neuronal death: A succession of necrosis or apoptosis depending on mitochondrial function. Neuron 1995, 15, 961–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewerenz, J.; Maher, P. Chronic Glutamate Toxicity in Neurodegenerative Diseases-What is the Evidence? Front. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosie, K.A.; King, A.E.; Blizzard, C.A.; Vickers, J.C.; Dickson, T.C. Chronic excitotoxin-induced axon degeneration in a compartmented neuronal culture model. ASN Neuro. 2012, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, D.H.; Gu, G.; Garcia-Anoveros, J.; Gong, L.; Chalfie, M.; Driscoll, M. Neuropathology of degenerative cell death in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Neurosci. 1997, 17, 1033–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calixto, A.; Jara, J.S.; Court, F.A. Diapause formation and downregulation of insulin-like signaling via DAF-16/FOXO delays axonal degeneration and neuronal loss. PLoS Genet. 2012, 8, e1003141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangaletti, R.; D’Amico, M.; Grant, J.; Della-Morte, D.; Bianchi, L. Knock-out of a mitochondrial sirtuin protects neurons from degeneration in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 2017, 13, e1006965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; McReynolds, M.R.; Goncalves, J.F.; Shu, M.; Dhondt, I.; Braeckman, B.P.; Lange, S.E.; Kho, K.; Detwiler, A.C.; Pacella, M.J.; et al. Comparative Metabolomic Profiling Reveals That Dysregulated Glycolysis Stemming from Lack of Salvage NAD+ Biosynthesis Impairs Reproductive Development in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 26163–26179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, E.S.; Song, S.B. Nicotinamide is an inhibitor of SIRT1 in vitro, but can be a stimulator in cells. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2017, 74, 3347–3362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriadi, M.; Hart, A.C. Neurodegenerative disorders: Insights from the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Neurobiol. Dis. 2010, 40, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, J.A.; Arango, M.; Abderrahmane, S.; Lambert, E.; Tourette, C.; Catoire, H.; Neri, C. Resveratrol rescues mutant polyglutamine cytotoxicity in nematode and mammalian neurons. Nat. Genet. 2005, 37, 349–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcain, F.J.; Villalba, J.M. Sirtuin activators. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2009, 19, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michan, S.; Sinclair, D. Sirtuins in mammals: Insights into their biological function. Biochem. J. 2007, 404, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herskovits, A.Z.; Guarente, L. SIRT1 in neurodevelopment and brain senescence. Neuron 2014, 81, 471–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, D.J.; Calingasan, N.Y.; Wille, E.; Dumont, M.; Beal, M.F. Resveratrol protects against peripheral deficits in a mouse model of Huntington’s disease. Exp. Neurol. 2010, 225, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Wang, J.; Fu, J.; Du, L.; Jeong, H.; West, T.; Xiang, L.; Peng, Q.; Hou, Z.; Cai, H.; et al. Neuroprotective role of Sirt1 in mammalian models of Huntington’s disease through activation of multiple Sirt1 targets. Nat. Med. 2011, 18, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.; Cohen, D.E.; Cui, L.; Supinski, A.; Savas, J.N.; Mazzulli, J.R.; Yates, J.R., 3rd; Bordone, L.; Guarente, L.; Krainc, D. Sirt1 mediates neuroprotection from mutant huntingtin by activation of the TORC1 and CREB transcriptional pathway. Nat. Med. 2011, 18, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthi-Carter, R.; Taylor, D.M.; Pallos, J.; Lambert, E.; Amore, A.; Parker, A.; Moffitt, H.; Smith, D.L.; Runne, H.; Gokce, O.; et al. SIRT2 inhibition achieves neuroprotection by decreasing sterol biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 7927–7932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, V.; Quinti, L.; Kim, J.; Vollor, L.; Narayanan, K.L.; Edgerly, C.; Cipicchio, P.M.; Lauver, M.A.; Choi, S.H.; Silverman, R.B.; et al. The sirtuin 2 inhibitor AK-7 is neuroprotective in Huntington’s disease mouse models. Cell Rep. 2012, 2, 1492–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallos, J.; Bodai, L.; Lukacsovich, T.; Purcell, J.M.; Steffan, J.S.; Thompson, L.M.; Marsh, J.L. Inhibition of specific HDACs and sirtuins suppresses pathogenesis in a Drosophila model of Huntington’s disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2008, 17, 3767–3775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neugebauer, R.C.; Uchiechowska, U.; Meier, R.; Hruby, H.; Valkov, V.; Verdin, E.; Sippl, W.; Jung, M. Structure-activity studies on splitomicin derivatives as sirtuin inhibitors and computational prediction of binding mode. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 1203–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Kumar, V.; Singh, K.; Kumar, S.; Kim, Y.S.; Lee, Y.M.; Kim, J.J. Therapeutic Advances for Huntington’s Disease. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, H.; Sinclair, D.A.; Ellis, J.L.; Steegborn, C. Sirtuin activators and inhibitors: Promises, achievements, and challenges. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 188, 140–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sussmuth, S.D.; Haider, S.; Landwehrmeyer, G.B.; Farmer, R.; Frost, C.; Tripepi, G.; Andersen, C.A.; Di Bacco, M.; Lamanna, C.; Diodato, E.; et al. An exploratory double-blind, randomized clinical trial with selisistat, a SirT1 inhibitor, in patients with Huntington’s disease. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2015, 79, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, R.; Gergou, A.; Wacker, I.; Fath, T.; Hutter, H. A Caenorhabditis elegans model of tau hyperphosphorylation: Induction of developmental defects by transgenic overexpression of Alzheimer’s disease-like modified tau. Neurobiol. Aging 2009, 30, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyasaka, T.; Ding, Z.; Gengyo-Ando, K.; Oue, M.; Yamaguchi, H.; Mitani, S.; Ihara, Y. Progressive neurodegeneration in C. elegans model of tauopathy. Neurobiol. Dis. 2005, 20, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, A.G.; Marfil, V.; Li, C. Use of Caenorhabditis elegans as a model to study Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative diseases. Front. Genet. 2014, 5, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, E.F.; Hou, Y.; Palikaras, K.; Adriaanse, B.A.; Kerr, J.S.; Yang, B.; Lautrup, S.; Hasan-Olive, M.M.; Caponio, D.; Dan, X.; et al. Mitophagy inhibits amyloid-beta and tau pathology and reverses cognitive deficits in models of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Neurosci. 2019, 22, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.; Jeong, Y.Y. Mitophagy in Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Age-Related Neurodegenerative Diseases. Cells 2020, 9, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrentino, V.; Romani, M.; Mouchiroud, L.; Beck, J.S.; Zhang, H.; D’Amico, D.; Moullan, N.; Potenza, F.; Schmid, A.W.; Rietsch, S.; et al. Enhancing mitochondrial proteostasis reduces amyloid-beta proteotoxicity. Nature 2017, 552, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spillantini, M.G.; Crowther, R.A.; Jakes, R.; Hasegawa, M.; Goedert, M. Alpha-Synuclein in filamentous inclusions of Lewy bodies from Parkinson’s disease and dementia with lewy bodies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 6469–6473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, J.F.; Van Raamsdonk, J.M. Modeling Parkinson’s Disease in C. elegans. J. Parkinsons Dis. 2018, 8, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakso, M.; Vartiainen, S.; Moilanen, A.M.; Sirvio, J.; Thomas, J.H.; Nass, R.; Blakely, R.D.; Wong, G. Dopaminergic neuronal loss and motor deficits in Caenorhabditis elegans overexpressing human alpha-synuclein. J. Neurochem. 2003, 86, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maulik, M.; Mitra, S.; Hunter, S.; Hunstiger, M.; Oliver, S.R.; Bult-Ito, A.; Taylor, B.E. Sir-2.1 mediated attenuation of alpha-synuclein expression by Alaskan bog blueberry polyphenols in a transgenic model of Caenorhabditis elegans. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 10216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farina, M.; Avila, D.S.; da Rocha, J.B.; Aschner, M. Metals, oxidative stress and neurodegeneration: A focus on iron, manganese and mercury. Neurochem. Int. 2013, 62, 575–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garza-Lombo, C.; Posadas, Y.; Quintanar, L.; Gonsebatt, M.E.; Franco, R. Neurotoxicity Linked to Dysfunctional Metal Ion Homeostasis and Xenobiotic Metal Exposure: Redox Signaling and Oxidative Stress. Antioxid. Redox Signal 2018, 28, 1669–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Martinez-Finley, E.J.; Bornhorst, J.; Chakraborty, S.; Aschner, M. Metal-induced neurodegeneration in C. elegans. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2013, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetto, A.; Au, C.; Avila, D.S.; Milatovic, D.; Aschner, M. Extracellular dopamine potentiates mn-induced oxidative stress, lifespan reduction, and dopaminergic neurodegeneration in a BLI-3-dependent manner in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 2010, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubert, P.; Puntel, B.; Lehmen, T.; Fessel, J.P.; Cheng, P.; Bornhorst, J.; Trindade, L.S.; Avila, D.S.; Aschner, M.; Soares, F.A.A. Metabolic effects of manganese in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans through DAergic pathway and transcription factors activation. Neurotoxicology 2018, 67, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caito, S.W.; Aschner, M. NAD+ Supplementation Attenuates Methylmercury Dopaminergic and Mitochondrial Toxicity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Toxicol. Sci. 2016, 151, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zajaczkowska, R.; Kocot-Kepska, M.; Leppert, W.; Wrzosek, A.; Mika, J.; Wordliczek, J. Mechanisms of Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, Y.; Li, Y.; Segal, R.A. A Mechanistic Understanding of Axon Degeneration in Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy. Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scripture, C.D.; Figg, W.D.; Sparreboom, A. Peripheral neuropathy induced by paclitaxel: Recent insights and future perspectives. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2006, 4, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, X.R.; Kaufman, D.M.; Crowder, C.M. Nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyltransferase promotes hypoxic survival by activating the mitochondrial unfolded protein response. Cell Death Dis. 2016, 7, e2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanik, M.F.; Cinar, H.; Cinar, H.N.; Chisholm, A.D.; Jin, Y.; Ben-Yakar, A. Neurosurgery: Functional regeneration after laser axotomy. Nature 2004, 432, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh-Roy, A.; Wu, Z.; Goncharov, A.; Jin, Y.; Chisholm, A.D. Calcium and cyclic AMP promote axonal regeneration in Caenorhabditis elegans and require DLK-1 kinase. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 3175–3183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Jin, Y. Intrinsic Control of Axon Regeneration. Neuron 2016, 90, 437–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.W.; Jin, Y. Neuronal responses to stress and injury in C. elegans. FEBS Lett. 2015, 589, 1644–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Shay, J.; McLoed, M.; Roodhouse, K.; Chung, S.H.; Clark, C.M.; Pirri, J.K.; Alkema, M.J.; Gabel, C.V. Neuronal regeneration in C. elegans requires subcellular calcium release by ryanodine receptor channels and can be enhanced by optogenetic stimulation. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 15947–15956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, Z.; Ghosh-Roy, A.; Hubert, T.; Yan, D.; O’Rourke, S.; Bowerman, B.; Wu, Z.; Jin, Y.; Chisholm, A.D. Axon regeneration pathways identified by systematic genetic screening in C. elegans. Neuron 2011, 71, 1043–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Zhou, T.; Kurnasov, O.; Cheek, S.; Grishin, N.V.; Osterman, A. Crystal structures of E. coli nicotinate mononucleotide adenylyltransferase and its complex with deamido-NAD. Structure 2002, 10, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Nye, D.M.; Stone, M.C.; Weiner, A.T.; Gheres, K.W.; Xiong, X.; Collins, C.A.; Rolls, M.M. Mitochondria and Caspases Tune Nmnat-Mediated Stabilization to Promote Axon Regeneration. PLoS Genet. 2016, 12, e1006503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilley, J.; Adalbert, R.; Yu, G.; Coleman, M.P. Rescue of peripheral and CNS axon defects in mice lacking NMNAT2. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 13410–13424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, A.B.; McWhirter, R.D.; Sekine, Y.; Strittmatter, S.M.; Miller, D.M.; Hammarlund, M. Inhibiting poly(ADP-ribosylation) improves axon regeneration. eLife 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- St-Laurent, J.F.; Desnoyers, S. Poly(ADP-ribose) metabolism analysis in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Methods Mol. Biol. 2011, 780, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, S.N.; Hengartner, M.O.; Desnoyers, S. The genes pme-1 and pme-2 encode two poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases in Caenorhabditis elegans. Biochem. J. 2002, 368, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, A.L.; Lee, J.M. Climbing STAIRs towards clinical trials with a novel PARP-1 inhibitor for the treatment of ischemic stroke. Brain Res. 2011, 1410, 120–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Anwar, M.; Aslam, H.M.; Anwar, S. PARP inhibitors. Hered. Cancer Clin. Pract. 2015, 13, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, P. Biology of Poly(ADP-Ribose) Polymerases: The Factotums of Cell Maintenance. Mol. Cell 2015, 58, 947–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Sekine, Y.; Byrne, A.B.; Cafferty, W.B.; Hammarlund, M.; Strittmatter, S.M. Inhibition of Poly-ADP-Ribosylation Fails to Increase Axonal Regeneration or Improve Functional Recovery after Adult Mammalian CNS Injury. eNeuro 2016, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brochier, C.; Jones, J.I.; Willis, D.E.; Langley, B. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 is a novel target to promote axonal regeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 15220–15225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, Y.; Jeong, H.; Park, K.H.; Kim, K.W. Effects of NAD+ in Caenorhabditis elegans Models of Neuronal Damage. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 993. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom10070993

Lee Y, Jeong H, Park KH, Kim KW. Effects of NAD+ in Caenorhabditis elegans Models of Neuronal Damage. Biomolecules. 2020; 10(7):993. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom10070993

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Yuri, Hyeseon Jeong, Kyung Hwan Park, and Kyung Won Kim. 2020. "Effects of NAD+ in Caenorhabditis elegans Models of Neuronal Damage" Biomolecules 10, no. 7: 993. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom10070993

APA StyleLee, Y., Jeong, H., Park, K. H., & Kim, K. W. (2020). Effects of NAD+ in Caenorhabditis elegans Models of Neuronal Damage. Biomolecules, 10(7), 993. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom10070993