The Contribution of Cytosolic Group IVA and Calcium-Independent Group VIA Phospholipase A2s to Adrenic Acid Mobilization in Murine Macrophages

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

2.2. Cell Culture

2.3. Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry (GC/MS) Analyses

2.4. Liquid Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry (LC/MS) Analyses of Phospholipids

3. Results

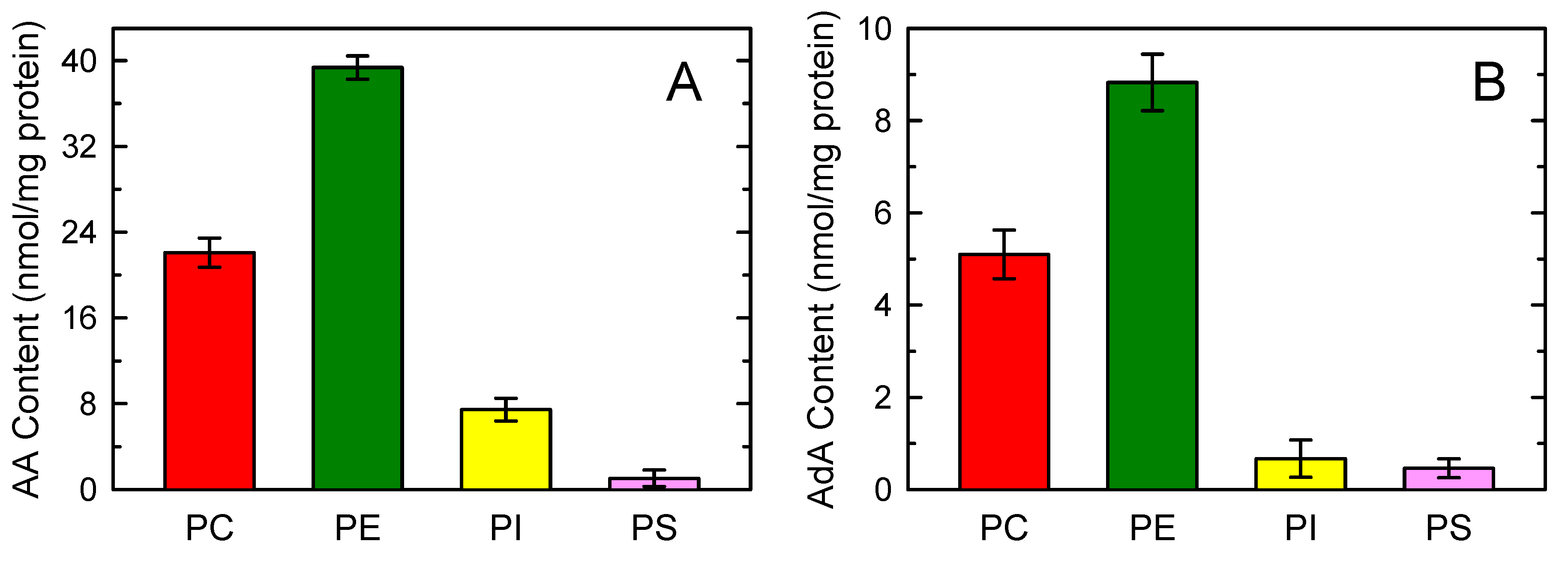

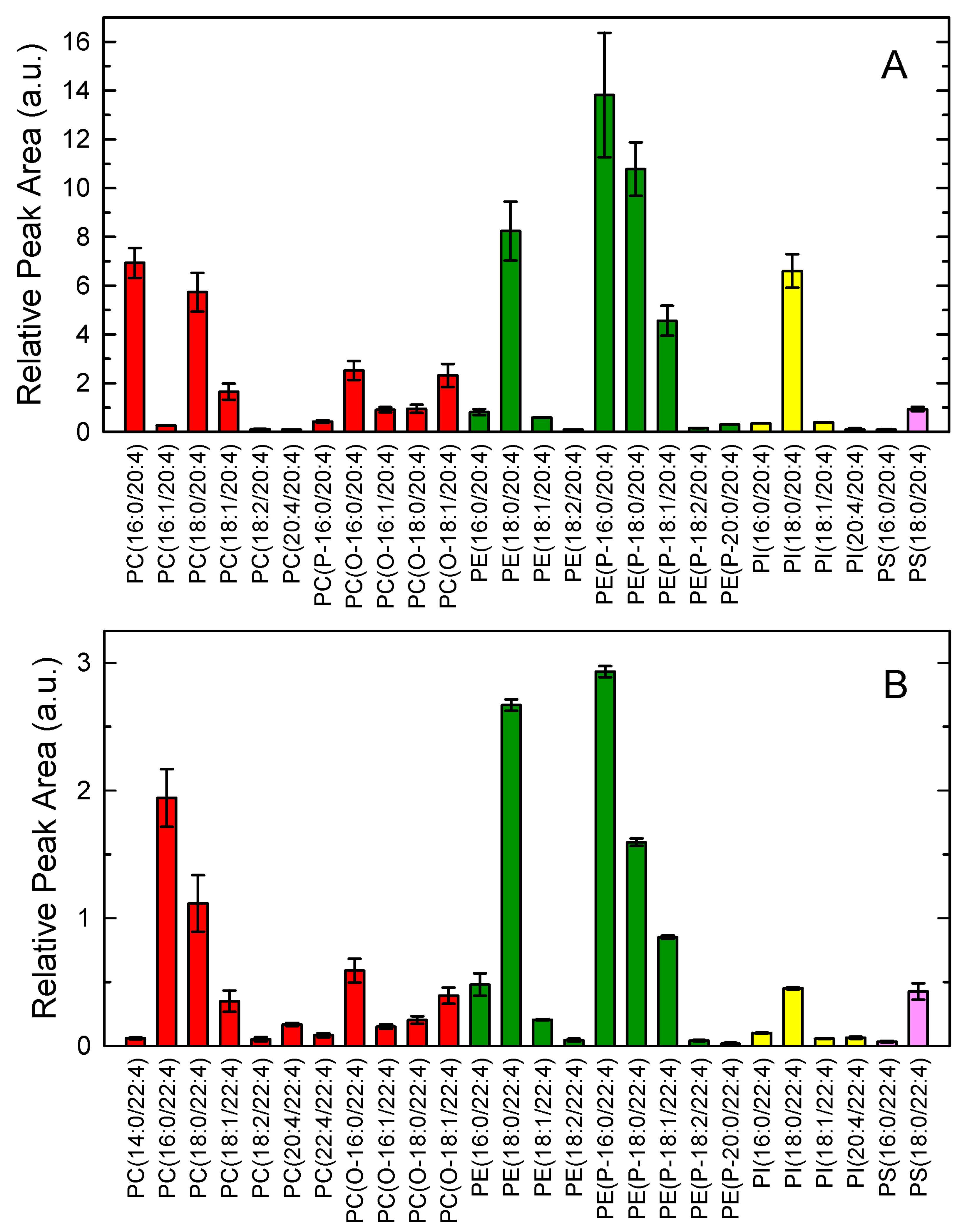

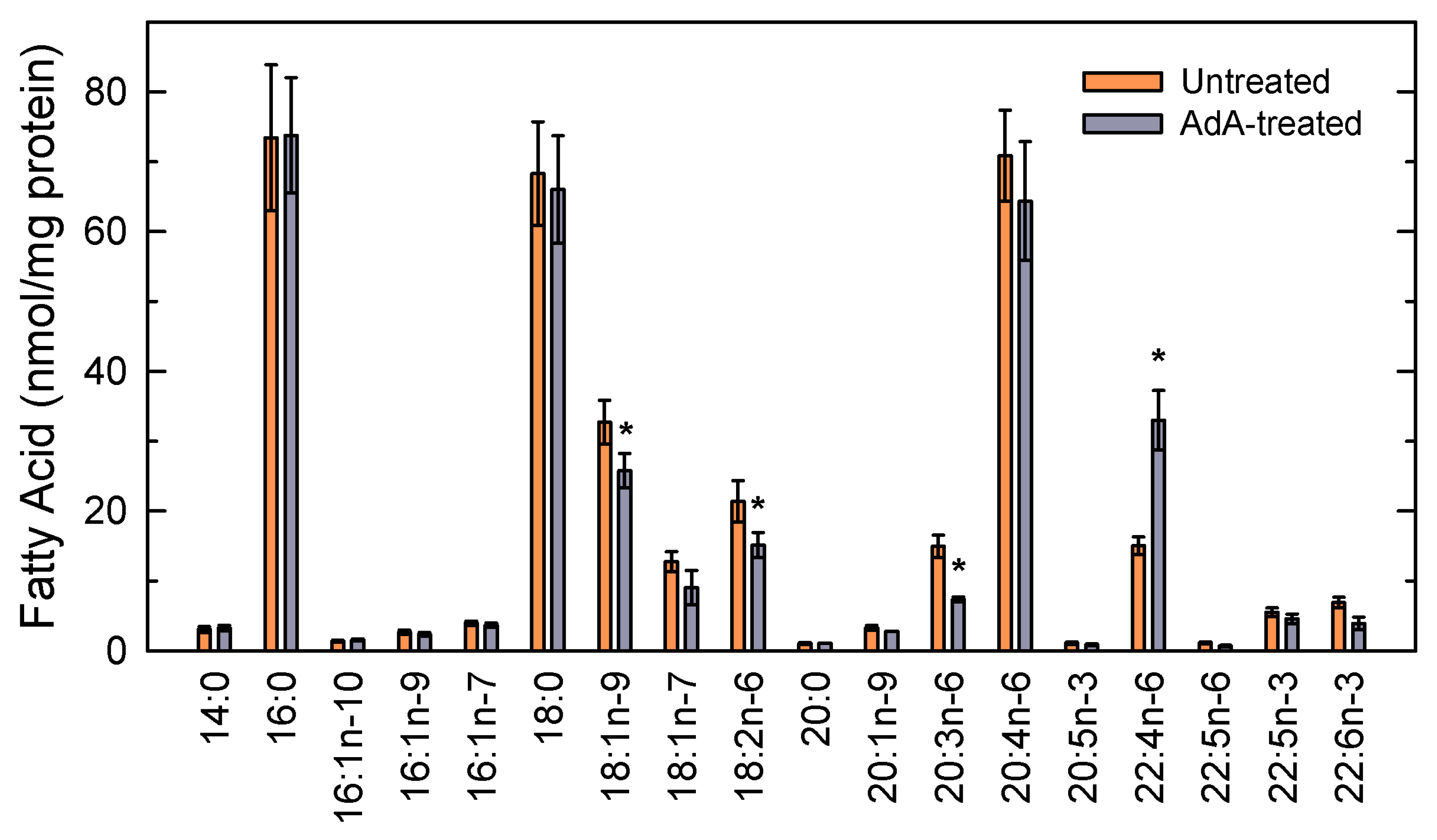

3.1. Adrenic Acid and Arachidonic Acid Contents of Murine Peritoneal Macrophages

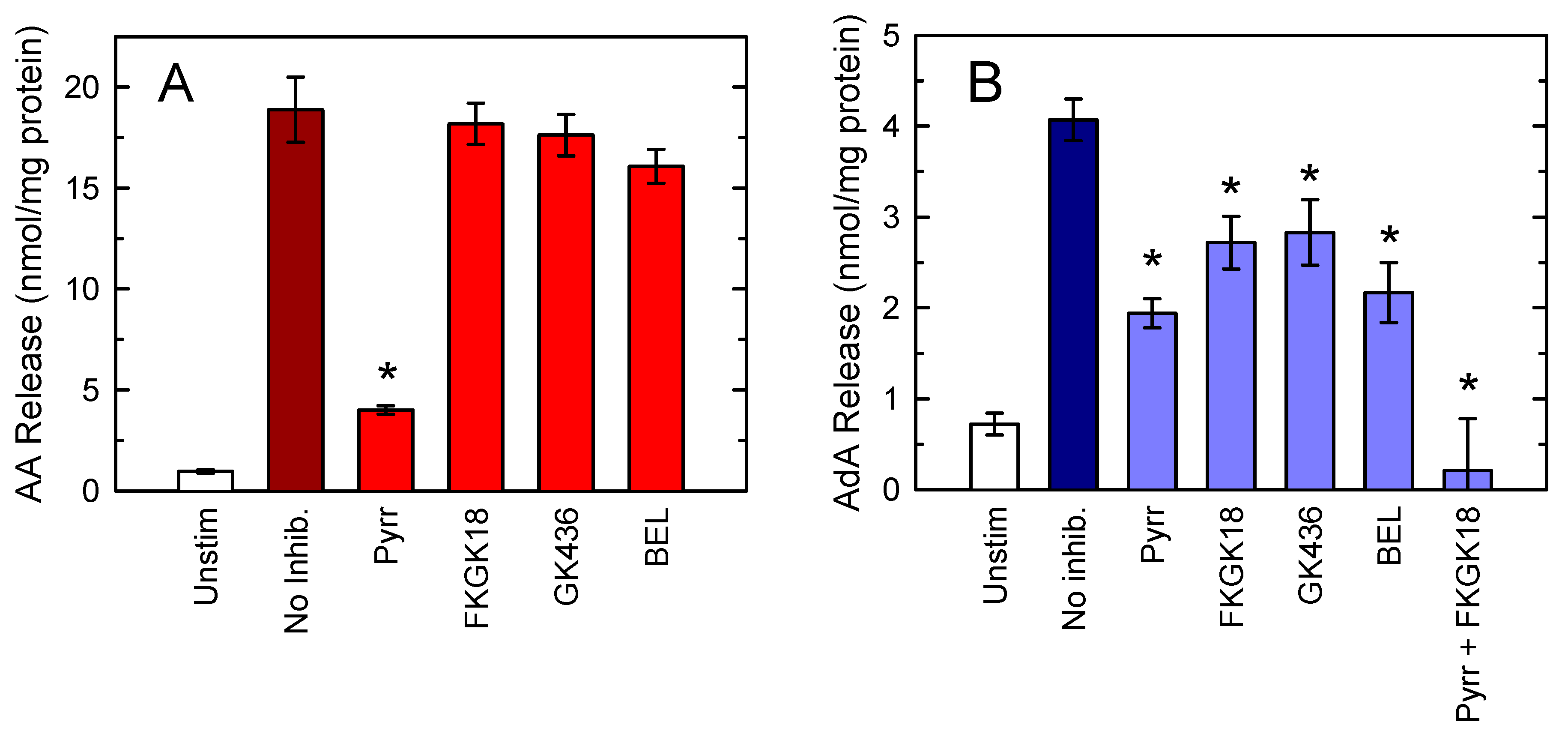

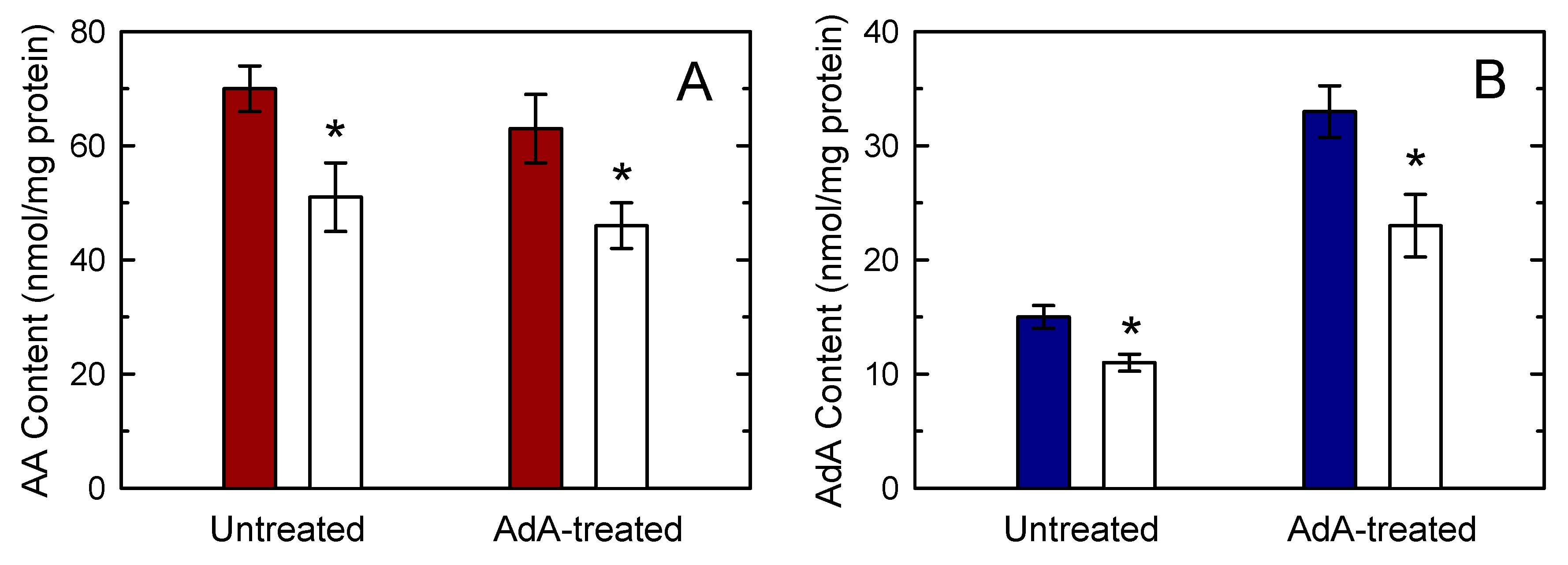

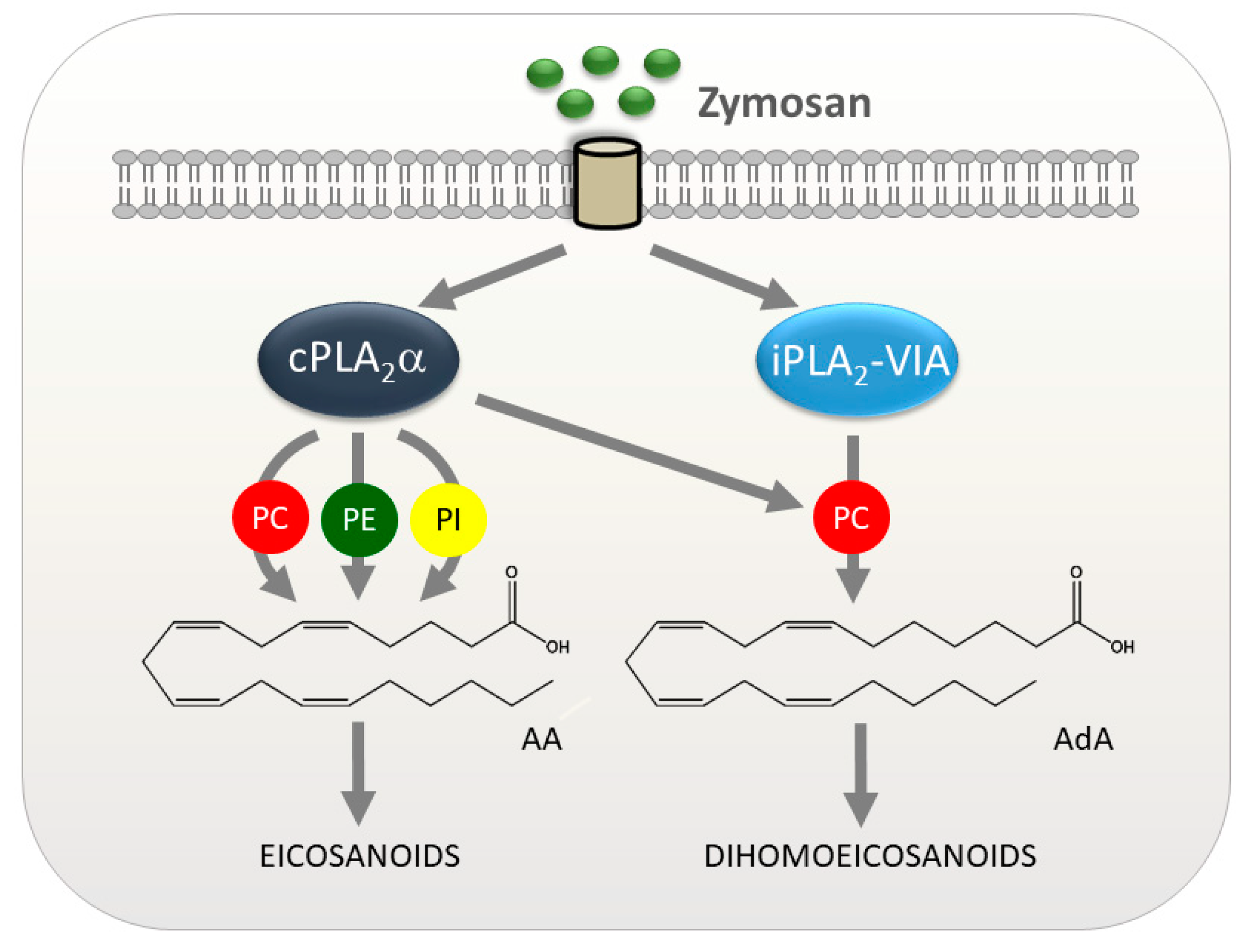

3.2. Defining the Role of Various PLA2 Forms in Stimulus-Induced AA and AdA Mobilization

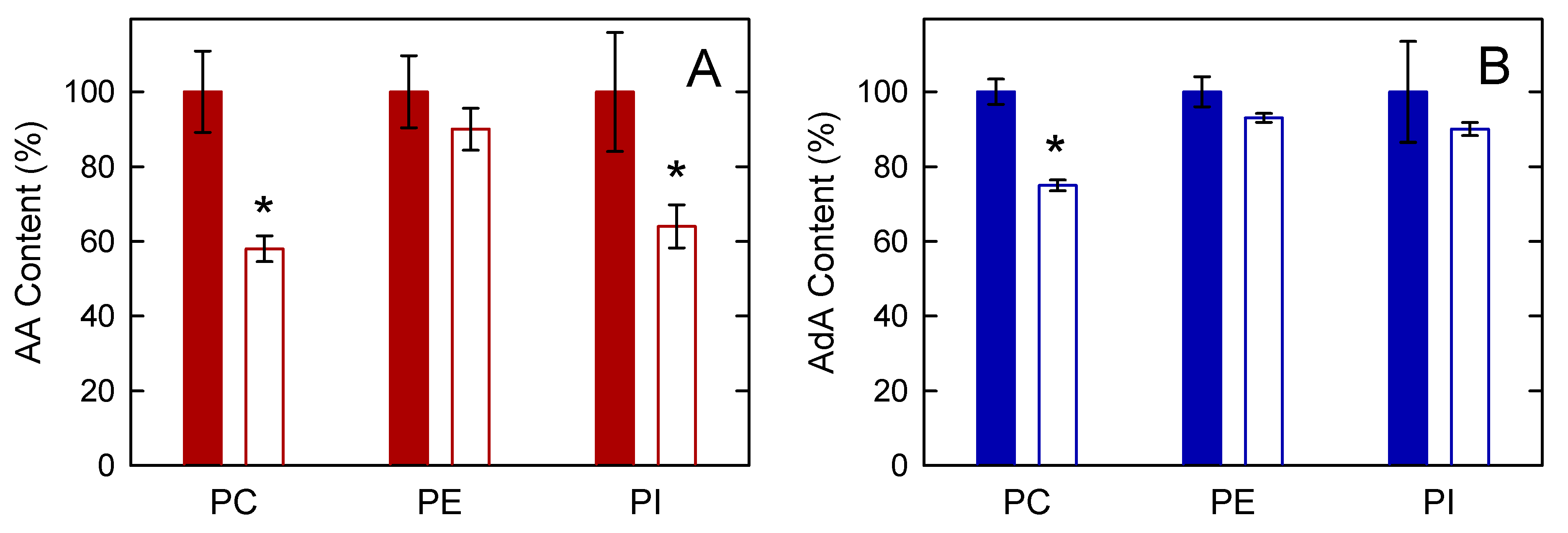

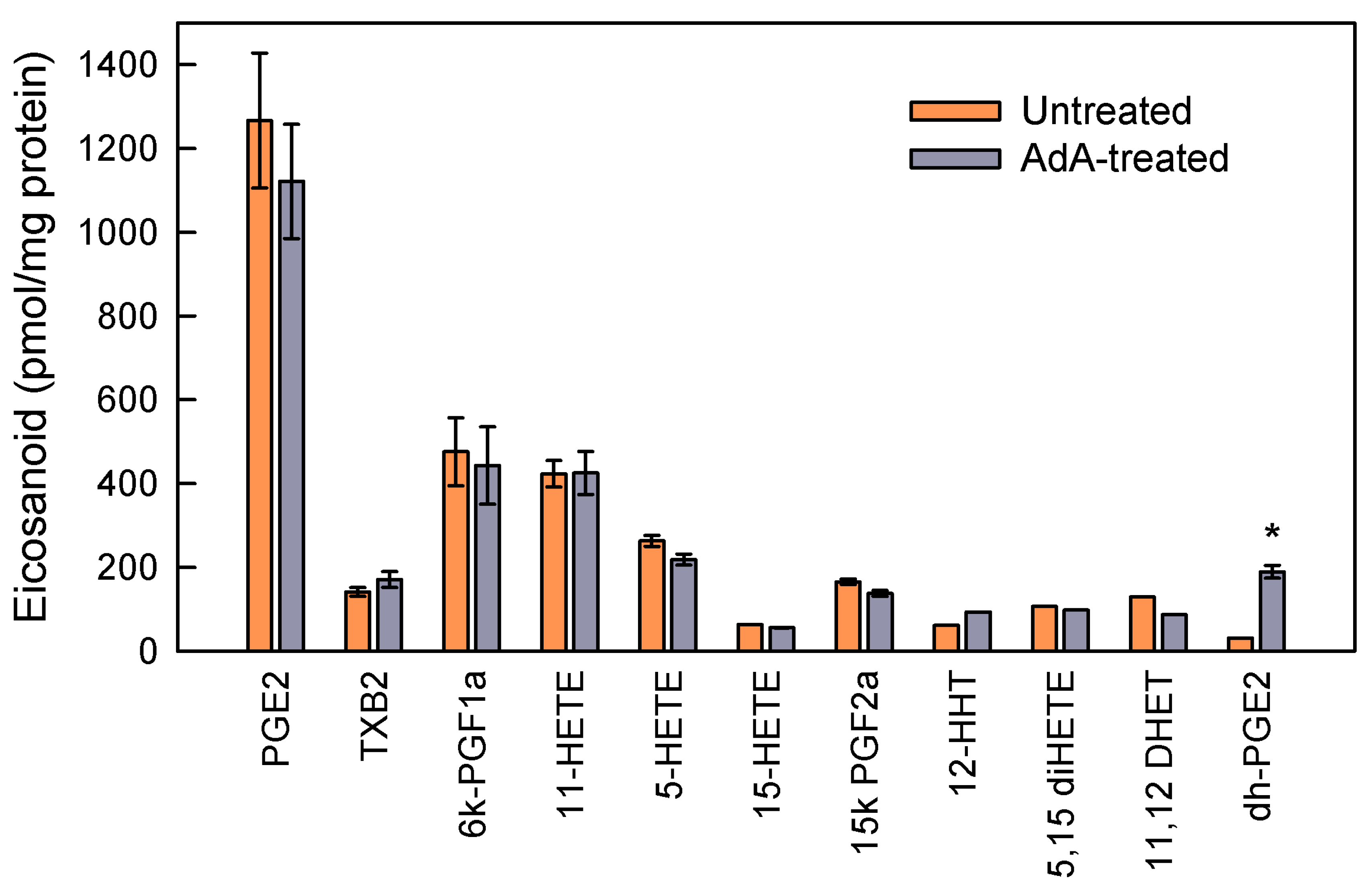

3.3. Studies with AdA-Enriched Cells

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Astudillo, A.M.; Meana, C.; Guijas, C.; Pereira, L.; Lebrero, R.; Balboa, M.A.; Balsinde, J. Occurrence and biological activity of palmitoleic acid isomers in phagocytic cells. J. Lipid Res. 2018, 59, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, E.A.; Norris, P.C. Eicosanoid storm in infection and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 15, 511–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astudillo, A.M.; Balboa, M.A.; Balsinde, J. Selectivity of phospholipid hydrolysis by phospholipase A2 enzymes in activated cells leading to polyunsaturated fatty acid mobilization. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2019, 1864, 772–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guijas, C.; Rodríguez, J.P.; Rubio, J.M.; Balboa, M.A.; Balsinde, J. Phospholipase A2 regulation of lipid droplet formation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1841, 1661–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astudillo, A.M.; Balgoma, D.; Balboa, M.A.; Balsinde, J. Dynamics of arachidonic acid mobilization by inflammatory cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1821, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Chacón, G.; Astudillo, A.M.; Balgoma, D.; Balboa, M.A.; Balsinde, J. Control of free arachidonic acid levels by phospholipases A2 and lysophospholipid acyltransferases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2009, 1791, 1103–1113. [Google Scholar]

- Peters-Golden, M.; Canetti, C.; Mancuso, P.; Coffey, M.J. Leukotrienes: Underappreciated mediators of innate immune responses. J. Immunol. 2005, 174, 589–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serhan, C.N. Resolution phase of inflammation: Novel endogenous antiinflammatory and proresolving lipid mediators and pathways. Ann. Rev. Immunol. 2007, 25, 101–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricciotti, E.; Fitzgerald, G.A. Prostaglandins and inflammation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2011, 31, 986–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinski, P. Regulation of immune responses by prostaglandin E2. J. Immunol. 2012, 188, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, C.J.; Kaduce, T.L.; Figard, P.H.; Spector, A.A. Docosatetraenoic acid in endothelial cells: Formation, retroconversion to arachidonic acid and effect on prostacyclin production. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1986, 244, 813–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, W.B.; Falck, J.R.; Okita, J.R.; Johnson, A.R.; Callahan, K.S. Synthesis of dihomoprostaglandins from adrenic acid (7,10,13,16-docosatetraenoic acid) by human endothelial cells in culture. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1985, 837, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.Y.; Gauthier, K.M.; Cui, L.; Nithipatikom, K.; Falck, J.R.; Campbell, W.B. Metabolism of adrenic acid to vasodilatory 1α,1β-dihomo-epoxyeicosatrienoic acids by bovine coronary arteries. Am. J. Physiol. 2007, 292, H2265–H2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopf, P.G.; Zhang, D.X.; Gauthier, K.M.; Nithipatikom, K.; Yi, X.Y.; Falck, J.R.; Campbell, W.B. Adrenic acid metabolites as endogenous endothelium-derived and zona glomerulosa-derived hyperpolarizing actors. Hypertension 2010, 55, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nababan, S.H.H.; Nishiumi, S.; Kawano, Y.; Kobayashi, T.; Yoshida, M.; Azuma, T. Adrenic acid as an inflammation enhancer in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Arch Biochem. Biophys. 2017, 623, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brouwers, H.; Jonasdottir, H.; Kwekkeboom, J.; López-Vicario, C.; Claria, J.; Freysdottir, J.; Hardardottir, I.; Huizinga, T.; Toes, R.; Giera, M.; et al. Adrenic acid as a novel anti-inflammatory player in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2018, 26, S126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guijas, C.; Astudillo, A.M.; Gil-de-Gómez, L.; Rubio, J.M.; Balboa, M.A.; Balsinde, J. Phospholipid sources for adrenic acid mobilization in RAW 264.7 macrophages: Comparison with arachidonic acid. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1821, 1386–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balgoma, D.; Astudillo, A.M.; Pérez-Chacón, G.; Montero, O.; Balboa, M.A.; Balsinde, J. Markers of monocyte activation revealed by lipidomic profiling of arachidonic acid-containing phospholipids. J. Immunol. 2010, 184, 3857–3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astudillo, A.M.; Pérez-Chacón, G.; Meana, C.; Balgoma, D.; Pol, A.; del Pozo, M.A.; Balboa, M.A.; Balsinde, J. Altered arachidonate distribution in macrophages from caveolin-1 null mice leading to reduced eicosanoid synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 35299–35307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdearcos, M.; Esquinas, E.; Meana, C.; Gil-de-Gómez, L.; Guijas, C.; Balsinde, J.; Balboa, M.A. Subcellular localization and role of lipin-1 in human macrophages. J. Immunol. 2011, 186, 6004–6013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-de-Gómez, L.; Astudillo, A.M.; Meana, C.; Rubio, J.M.; Guijas, C.; Balboa, M.A.; Balsinde, J. A phosphatidylinositol species acutely generated by activated macrophages regulates innate immune responses. J. Immunol. 2013, 190, 5169–5177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil-de-Gómez, L.; Astudillo, A.M.; Guijas, C.; Magrioti, V.; Kokotos, G.; Balboa, M.A.; Balsinde, J. Cytosolic group IVA and calcium-independent group VIA phospholipase A2s act on distinct phospholipid pools in zymosan-stimulated mouse peritoneal macrophages. J. Immunol. 2014, 192, 752–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubio, J.M.; Rodríguez, J.P.; Gil-de-Gómez, L.; Guijas, C.; Balboa, M.A.; Balsinde, J. Group V secreted phospholipase A2 is up-regulated by interleukin-4 in human macrophages and mediates phagocytosis via hydrolysis of ethanolamine phospholipids. J. Immunol. 2015, 194, 3327–3339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil-de-Gómez, L.; Astudillo, A.M.; Lebrero, P.; Balboa, M.A.; Balsinde, J. Essential role for ethanolamine plasmalogen hydrolysis in bacterial lipopolysaccharide priming of macrophages for enhanced arachidonic acid release. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubio, J.M.; Astudillo, A.M.; Casas, J.; Balboa, M.A.; Balsinde, J. Regulation of phagocytosis in macrophages by membrane ethanolamine plasmalogens. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1723. [Google Scholar]

- Lebrero, P.; Astudillo, A.M.; Rubio, J.M.; Fernández-Caballero, J.; Kokotos, G.; Balboa, M.A.; Balsinde, J. Cellular plasmalogen content does not influence arachidonic acid levels or distribution in macrophages: A role for cytosolic phospholipase A2γ in phospholipid remodeling. Cells 2019, 8, 799. [Google Scholar]

- Guijas, C.; Bermúdez, M.A.; Meana, C.; Astudillo, A.M.; Pereira, L.; Fernández-Caballero, L.; Balboa, M.A.; Balsinde, J. Neutral lipids are not a source of arachidonic acid for lipid mediator signaling in human foamy monocytes. Cells 2019, 8, 941. [Google Scholar]

- Chilton, F.H. Potential phospholipid source(s) of arachidonate used for the synthesis of leukotrienes by the human neutrophil. Biochem. J. 1989, 258, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, T.; Yamada, K.; Chikazawa, Y.; Ueno, M.; Nakamoto, S.; Okuno, T.; Seno, K. Characterization of a novel inhibitor of cytosolic phospholipase A2α, pyrrophenone. Biochem. J. 2002, 363, 727–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokotos, G.; Hsu, Y.H.; Burke, J.E.; Baskakis, C.; Kokotos, C.G.; Magrioti, V.; Dennis, E.A. Potent and selective fluoroketone inhibitors of group VIA calcium-independent phospholipase A2. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 3602–3610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedaki, C.; Kokotou, M.G.; Mouchlis, V.D.; Limnios, D.; Lei, X.; Mu, C.T.; Ramanadham, S.; Magrioti, V.; Dennis, E.A.; Kokotos, G. β-Lactones: A novel class of Ca2+-independent phospholipase A2 (group VIA iPLA2) inhibitors with the ability to inhibit β-cell apoptosis. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 2916–2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balsinde, J.; Fernández, B.; Diez, E. Regulation of arachidonic acid release in mouse peritoneal macrophages. The role of extracellular calcium and protein kinase C. J. Immunol. 1990, 144, 4298–4304. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Balsinde, J.; Fernández, B.; Solís-Herruzo, J.A.; Diez, E. Pathways for arachidonic acid mobilization in zymosan-stimulated mouse peritoneal macrophages. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1992, 1136, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balboa, M.A.; Sáez, Y.; Balsinde, J. Calcium-independent phospholipase A2 is required for lysozyme secretion in U937 promonocytes. J. Immunol. 2003, 170, 5276–5280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balboa, M.A.; Pérez, R.; Balsinde, J. Amplification mechanisms of inflammation: Paracrine stimulation of arachidonic acid mobilization by secreted phospholipase A2 is regulated by cytosolic phospholipase A2-derived hydroperoxyeicosatetraenoic acid. J. Immunol. 2003, 171, 989–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsinde, J.; Balboa, M.A.; Insel, P.A.; Dennis, E.A. Differential regulation of phospholipase D and phospholipase A2 by protein kinase C in P388D1 macrophages. Biochem. J. 1997, 321, 805–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, R.; Matabosch, X.; Llebaria, A.; Balboa, M.A.; Balsinde, J. Blockade of arachidonic acid incorporation into phospholipids induces apoptosis in U937 promonocytic cells. J. Lipid Res. 2006, 47, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bligh, E.G.; Dyer, W.J. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 1959, 37, 911–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez, E.; Balsinde, J.; Aracil, M.; Schüller, A. Ethanol induces release of arachidonic acid but not synthesis of eicosanoids in mouse peritoneal macrophages. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1987, 921, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, J.B.; Sprecher, H. Unidimensional thin-layer chromatography of phospholipids on boric acid-impregnated plates. J. Lipid Res. 1982, 23, 660–663. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Astudillo, A.M.; Pérez-Chacón, G.; Balgoma, D.; Gil-de-Gómez, L.; Ruipérez, V.; Guijas, C.; Balboa, M.A.; Balsinde, J. Influence of cellular arachidonic acid levels on phospholipid remodeling and CoA-independent transacylase activity in human monocytes and U937 cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2011, 1811, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guijas, C.; Pérez-Chacón, G.; Astudillo, A.M.; Rubio, J.M.; Gil-de-Gómez, L.; Balboa, M.A.; Balsinde, J. Simultaneous activation of p38 and JNK by arachidonic acid stimulates the cytosolic phospholipase A2-dependent synthesis of lipid droplets in human monocytes. J. Lipid Res. 2012, 53, 2343–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guijas, C.; Meana, C.; Astudillo, A.M.; Balboa, M.A.; Balsinde, J. Foamy monocytes are enriched in cis-7-hexadecenoic fatty acid (16:1n-9), a possible biomarker for early detection of cardiovascular disease. Cell Chem. Biol. 2016, 23, 689–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez, J.P.; Guijas, C.; Astudillo, A.M.; Rubio, J.M.; Balboa, M.A.; Balsinde, J. Sequestration of 9-hydroxystearic acid in FAHFA (fatty acid esters of hydroxy fatty acids) as a protective mechanism for colon carcinoma cells to avoid apoptotic cell death. Cancers 2019, 11, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Axelsen, P.H.; Murphy, R.C. Quantitative analysis of phospholipids containing arachidonate and docosahexaenoate chains in microdissected regions of mouse brain. J. Lipid Res. 2010, 51, 660–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahy, E.; Subramaniam, S.; Brown, H.A.; Glass, C.K.; Merrill, A.H., Jr.; Murphy, R.C.; Raetz, C.R.; Russell, D.W.; Seyama, Y.; Shaw, W.; et al. A comprehensive classification system for lipids. J. Lipid Res. 2005, 46, 839–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, R.C.; Folco, G. Lysophospholipid acyltransferases and leukotriene biosynthesis: Intersection of the Lands cycle and the arachidonate PI cycle. J. Lipid Res. 2019, 60, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouzer, C.A.; Ivanova, P.T.; Byrne, M.O.; Milne, S.B.; Brown, H.A.; Marnett, L.J. Lipid profiling reveals glycerophospholipid remodeling in zymosan-stimulated macrophages. Biochemistry 2007, 46, 6026–6042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gijón, M.A.; Spencer, D.M.; Siddiqi, A.R.; Bonventre, J.V.; Leslie, C.C. Cytosolic phospholipase A2 is required for macrophage arachidonic acid release by agonists that do and do not mobilize calcium. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 20146–20156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaou, A.; Kokotou, M.G.; Vasilakaki, S.; Kokotos, G. Small-molecule inhibitors as potential therapeutics and as tools to understand the role of phospholipases A2. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2019, 1864, 941–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balboa, M.A.; Balsinde, J. Involvement of calcium-independent phospholipase A2 in hydrogen peroxide-induced accumulation of free fatty acids in human U937 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 40384–40389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghomashchi, F.; Stewart, A.; Hefner, Y.; Ramanadham, S.; Turk, J.; Leslie, C.C.; Gelb, M.H. A pyrrolidine-based specific inhibitor of cytosolic phospholipase A2α blocks arachidonic acid release in a variety of mammalian cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2001, 1513, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, E.A.; Cao, J.; Hsu, Y.H.; Magrioti, V.; Kokotos, G. Phospholipase A2 enzymes: Physical structure, biological function, disease implication, chemical inhibition, and therapeutic intervention. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 6130–6185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonventre, J.V. Cytosolic phospholipase A2α reigns supreme in arthritis and bone resorption. Trends Immunol. 2004, 25, 116–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bone, R.N.; Gai, Y.; Magrioti, V.; Kokotou, M.G.; Ali, T.; Lei, X.; Tse, H.M.; Kokotos, G.; Ramanadham, S. Inhibition of Ca2+-independent phospholipase A2β (iPLA2β) ameliorates islet infiltration and incidence of diabetes in NOD mice. Diabetes 2015, 64, 541–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, T.; Kokotos, G.; Magrioti, V.; Bone, R.N.; Mobley, J.A.; Hancock, W.; Ramanadham., S. Characterization of FKGK18 as inhibitor of group VIA Ca2+-independent phospholipase A2 (iPLA2β): Candidate drug for preventing beta-cell apoptosis and diabetes. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e71748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiba, S.; Mizunaga, S.; Kume, K.; Hayama, M.; Sato, T. Involvement of Group VI Ca2+-independent phospholipase A2 in protein kinase C-dependent arachidonic acid liberation in zymosan-stimulated macrophage-like P388D1 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 19906–19912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsinde, J.; Balboa, M.A.; Dennis, E.A. Identification of a third pathway for arachidonic acid mobilization and prostaglandin production in activated P388D1 macrophage-like cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 22544–22549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsinde, J.; Dennis, E.A. Distinct roles in signal transduction for each of the phospholipase A2 enzymes present in P388D1 macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 6758–6765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsinde, J.; Balboa, M.A.; Yedgar, S.; Dennis, E.A. Group V phospholipase A2-mediated oleic acid mobilization in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated P388D1 macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 4783–4786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balboa, M.A.; Balsinde, J.; Dillon, D.A.; Carman, G.M.; Dennis, E.A. Proinflammatory macrophage-activating properties of the novel phospholipid diacylglycerol pyrophosphate. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 522–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balboa, M.A.; Shirai, Y.; Gaietta, G.; Ellisman, M.H.; Balsinde, J.; Dennis, E.A. Localization of group V phospholipase A2 in caveolin-enriched granules in activated P388D1 macrophage-like cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 48059–48065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casas, J.; Gijón, M.A.; Vigo, A.G.; Crespo, M.S.; Balsinde, J.; Balboa, M.A. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate anchors cytosolic group IVA phospholipase A2 to perinuclear membranes and decreases its calcium requirement for translocation in live cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 2006, 17, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramanadham, S.; Ali, T.; Ashley, J.W.; Bone, R.N.; Hancock, W.D.; Lei, X. Calcium-independent phospholipases A2 and their roles in biological processes and diseases. J. Lipid Res. 2015, 56, 1643–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, C.M.; Mancuso, D.J.; Yan, W.; Sims, H.F.; Gibson, B.; Gross, R.W. Identification, cloning, expression and purification of three novel human calcium-independent phospholipase A2 family members possessing triacylglycerol lipase and acylglycerol transacylase activities. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 48968–48975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pindado, J.; Balsinde, J.; Balboa, M.A. TLR3-dependent induction of nitric oxide synthase in RAW 264.7 macrophage-like cells via a cytosolic phospholipase A2/cyclooxygenase-2 pathway. J. Immunol. 2007, 179, 4821–4828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balboa, M.A.; Balsinde, J.; Dennis, E.A. Involvement of phosphatidate phosphohydrolase in arachidonic acid mobilization in human amnionic WISH cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 7684–7690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, L.; Pérez, R.; Nieto, M.L.; Balsinde, J.; Balboa, M.A. Bromoenol lactone promotes cell death by a mechanism involving phosphatidate phosphohydrolase-1 rather than calcium-independent phospholipase A2. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 44683–44690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagen, L.M.; Baer, P.G. Adrenic acid inhibits prostaglandin synthesis. Life Sci. 1980, 26, 765–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, M.D.; Hill, J.R. Elongation of arachidonic and eicosapentaenoic acids limits their availability for thrombin-stimulated release from the glycerolipids of vascular endothelial cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1986, 875, 382–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkewicz, R.; Fahy, E.; Andreyev, A.; Dennis, E.A. Arachidonate-derived dihomoprostaglandin production observed in endotoxin-stimulated macrophage-like cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 2899–2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonard, A.E.; Pereira, S.L.; Sprecher, H.; Huang, Y.S. Elongation of long-chain fatty acids. Prog. Lipid Res. 2004, 43, 36–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprecher, H.; Luthria, D.L.; Mohammed, B.S.; Baykousheva, S.P. Reevaluation of the pathways for the biosynthesis of polyunsaturated fatty acids. J. Lipid Res. 1995, 36, 2471–2477. [Google Scholar]

- Sprecher, H.; Van Rollins, M.; Sun, F.; Wyche, A.; Needleman, P. Dihomo prostaglandin and dihomo-thromboxane. A prostaglandin family from adrenic acid that may be preferentially synthesized in the kidney. J. Biol. Chem. 1982, 257, 3912–3918. [Google Scholar]

- Leslie, C.C. Cytosolic phospholipase A₂: Physiological function and role in disease. J. Lipid Res. 2015, 56, 1386–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsinde, J.; Winstead, M.V.; Dennis, E.A. Phospholipase A2 regulation of arachidonic acid mobilization. FEBS Lett. 2002, 531, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winstead, M.V.; Balsinde, J.; Dennis, E.A. Calcium-independent phospholipase A2: Structure and function. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2000, 1488, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsinde, J.; Balboa, M.A. Cellular regulation and proposed biological functions of group VIA calcium-independent phospholipase A2 in activated cells. Cell. Signal. 2005, 17, 1052–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirai, Y.; Balsinde, J.; Dennis, E.A. Localization and functional interrelationships among cytosolic group IV, secreted group V, and Ca2+-independent group VI phospholipase A2s in P388D1 macrophages using GFP/RFP constructs. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2005, 1735, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Chacón, G.; Astudillo, A.M.; Ruipérez, V.; Balboa, M.A.; Balsinde, J. Signaling role for lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3 in receptor-regulated arachidonic acid reacylation reactions in human monocytes. J. Immunol. 2010, 184, 1071–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Underhill, D.M. Macrophage recognition of zymosan particles. J. Endotoxin Res. 2003, 9, 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suram, S.; Brown, G.D.; Ghosh, M.; Gordon, S.; Loper, R.; Taylor, P.R.; Akira, S.; Uematsu, S.; Williams, D.L.; Leslie, C.C. Regulation of cytosolic phospholipase A2 activation and cyclooxygenase-2 expression in macrophages by the β-glucan receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 5506–5514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suram, S.; Gangelhoff, T.A.; Taylor, P.R.; Rosas, M.; Brown, G.D.; Bonventre, J.V.; Akira, S.; Uematsu, S.; Williams, D.L.; Murphy, R.C.; et al. Pathways regulating cytosolic phospholipase A2 activation and eicosanoid production in macrophages by Candida albicans. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 30676–30685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noor, S.; Goldfine, H.; Tucker, D.E.; Suram, S.; Lenz, L.L.; Akira, S.; Suematsu, S.; Girotti, M.; Bonventre, J.V.; Breuel, K.; et al. Activation of cytosolic phospholipase A2α in resident peritoneal macrophages by Listeria monocytogenes involves listeriolysin O and TLR2. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 4744–4755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruipérez, V.; Astudillo, M.A.; Balboa, M.A.; Balsinde, J. Coordinate regulation of TLR-mediated arachidonic acid mobilization in macrophages by group IVA and group V phospholipase A2s. J. Immunol. 2009, 182, 3877–3883. [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara, H.; Balboa, M.A.; Johnson, C.A.; Balsinde, J.; Dennis, E.A. Regulation od delayed prostaglandin production in activated P388D1 macrophages by group IV cytosolic and group V secretory phospholipase A2s. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 12263–12268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aderem, A.A.; Cohen, D.S.; Wright, S.D.; Cohn, Z.A. Bacterial lipopolysaccharides prime macrophages for enhanced release of arachidonic acid metabolites. J. Exp. Med. 1986, 164, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, R.M.; Sharp, J.D. Structure, function and regulation of Ca2+-sensitive cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2). FEBS Lett. 1997, 410, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouchlis, V.D.; Chen, Y.; McCammon, J.A.; Dennis, E.A. Membrane allostery and unique hydrophobic sites promote enzyme substrate specificity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 3285–3291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilton, F.H.; Fonteh, A.N.; Surette, M.E.; Triggiani, M.; Winkler, J.D. Control of arachidonate levels within inflammatory cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1996, 1299, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, A.; Hayashi, Y.; Matsumoto, N.; Nemoto-Sasaki, Y.; Koizumi, T.; Inagaki, Y.; Oka, S.; Tanikawa, T.; Sugiura, T. Coenzyme-A-independent transacylation system; possible involvement of phospholipase A2 in transacylation. Biology 2017, 6, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Monge, P.; Garrido, A.; Rubio, J.M.; Magrioti, V.; Kokotos, G.; Balboa, M.A.; Balsinde, J. The Contribution of Cytosolic Group IVA and Calcium-Independent Group VIA Phospholipase A2s to Adrenic Acid Mobilization in Murine Macrophages. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 542. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom10040542

Monge P, Garrido A, Rubio JM, Magrioti V, Kokotos G, Balboa MA, Balsinde J. The Contribution of Cytosolic Group IVA and Calcium-Independent Group VIA Phospholipase A2s to Adrenic Acid Mobilization in Murine Macrophages. Biomolecules. 2020; 10(4):542. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom10040542

Chicago/Turabian StyleMonge, Patricia, Alvaro Garrido, Julio M. Rubio, Victoria Magrioti, George Kokotos, María A. Balboa, and Jesús Balsinde. 2020. "The Contribution of Cytosolic Group IVA and Calcium-Independent Group VIA Phospholipase A2s to Adrenic Acid Mobilization in Murine Macrophages" Biomolecules 10, no. 4: 542. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom10040542

APA StyleMonge, P., Garrido, A., Rubio, J. M., Magrioti, V., Kokotos, G., Balboa, M. A., & Balsinde, J. (2020). The Contribution of Cytosolic Group IVA and Calcium-Independent Group VIA Phospholipase A2s to Adrenic Acid Mobilization in Murine Macrophages. Biomolecules, 10(4), 542. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom10040542