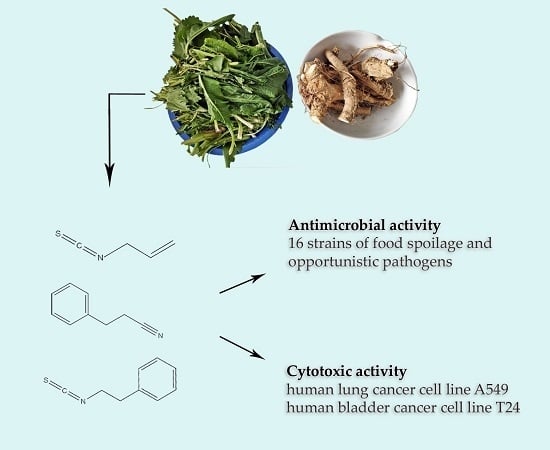

Biological Effects of Glucosinolate Degradation Products from Horseradish: A Horse that Wins the Race

Abstract

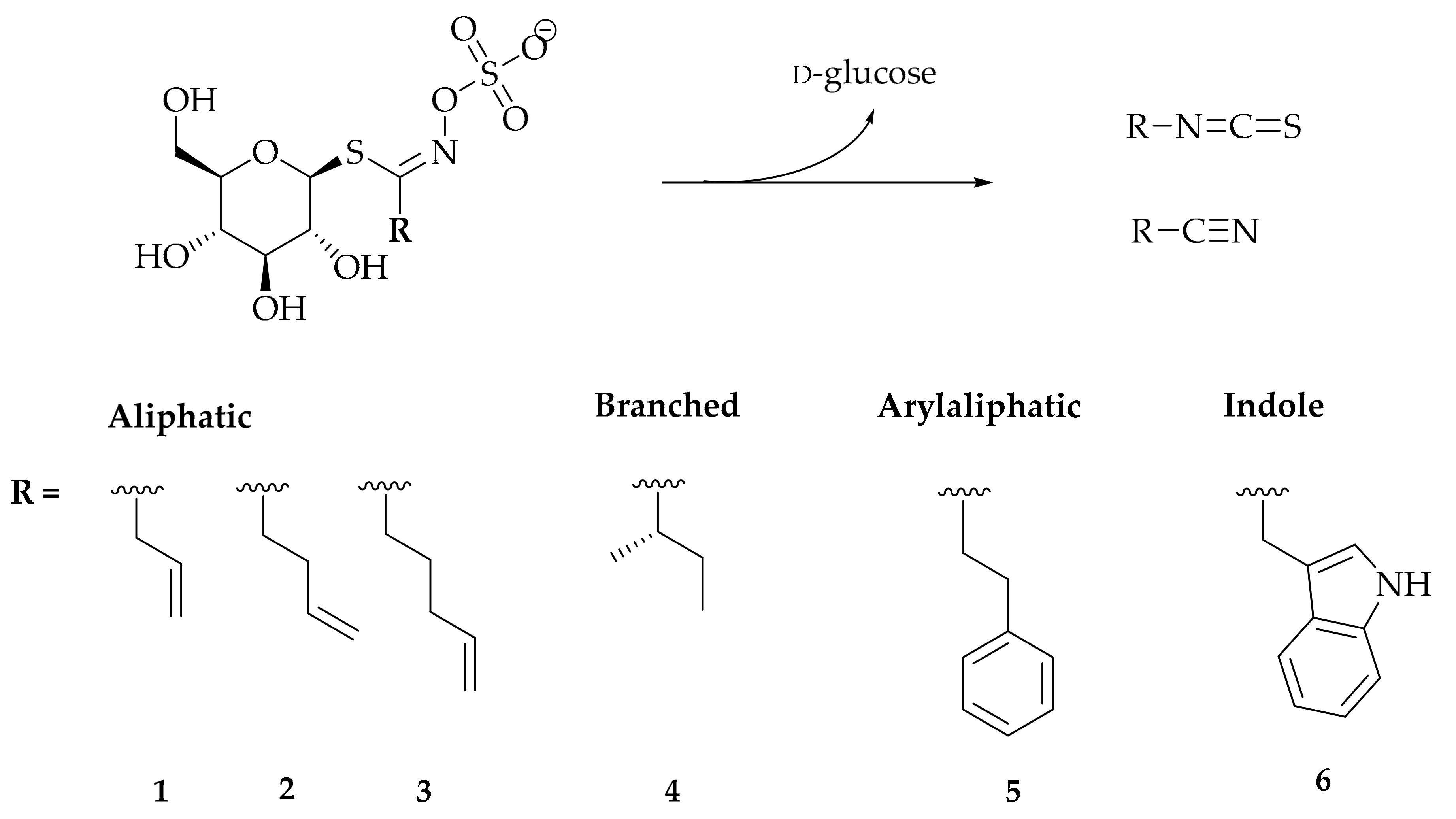

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Standards

2.2. Analysis of Glucosinolates and Volatiles

2.2.1. Isolation of Desulfoglucosinolates

2.2.2. HPLC-DAD Analysis of Desulfoglucosinolates

2.2.3. UHPLC-MS/MS Analysis of Desulfoglucosinolates

2.2.4. Isolation of Volatiles

2.2.5. GC-MS Analysis of Volatiles

2.3. Antimicrobial Activity

2.3.1. Bacterial Strains

2.3.2. Microdilution Assays

2.4. Cytotoxic Activity

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemical Characterization

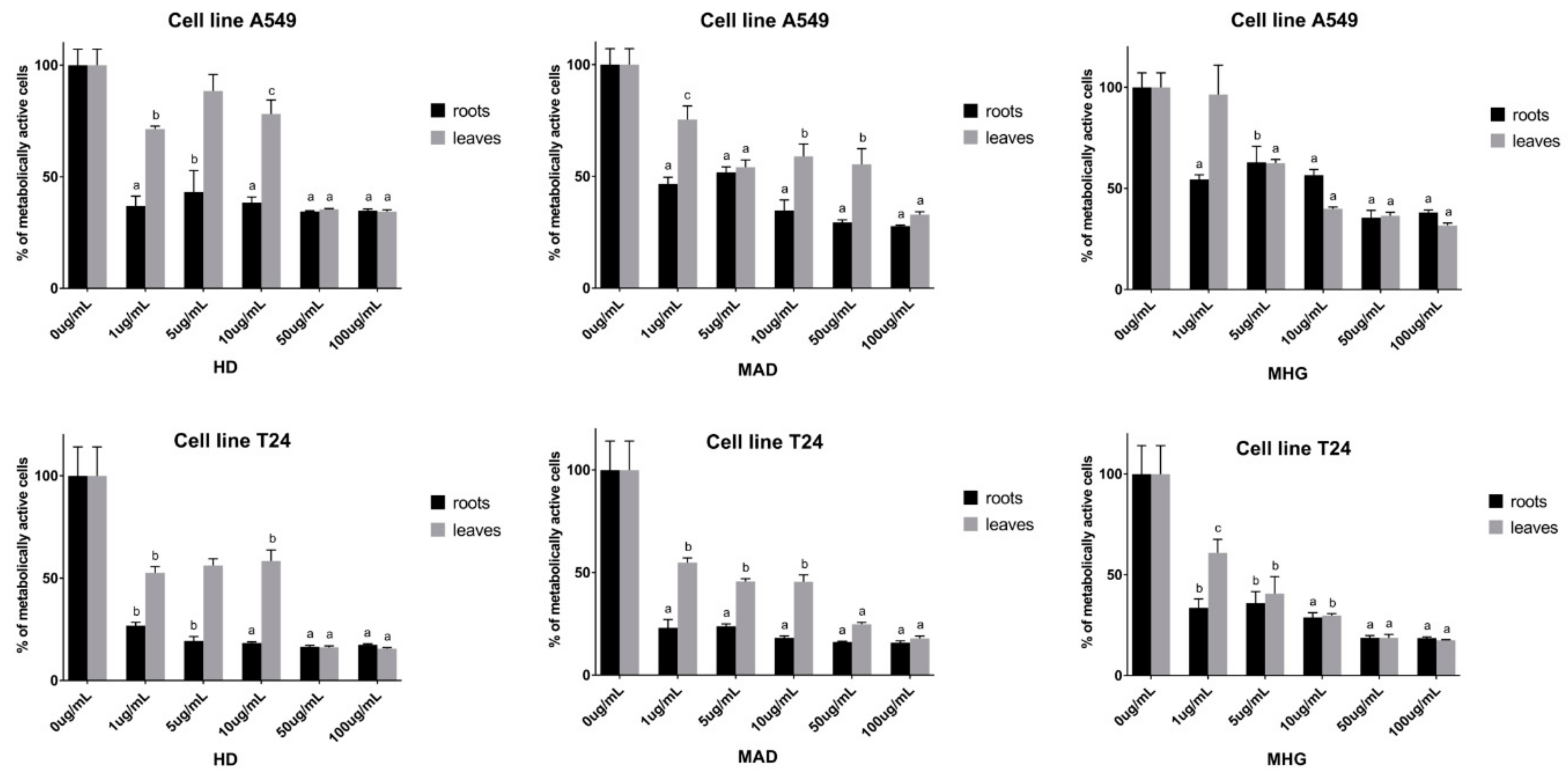

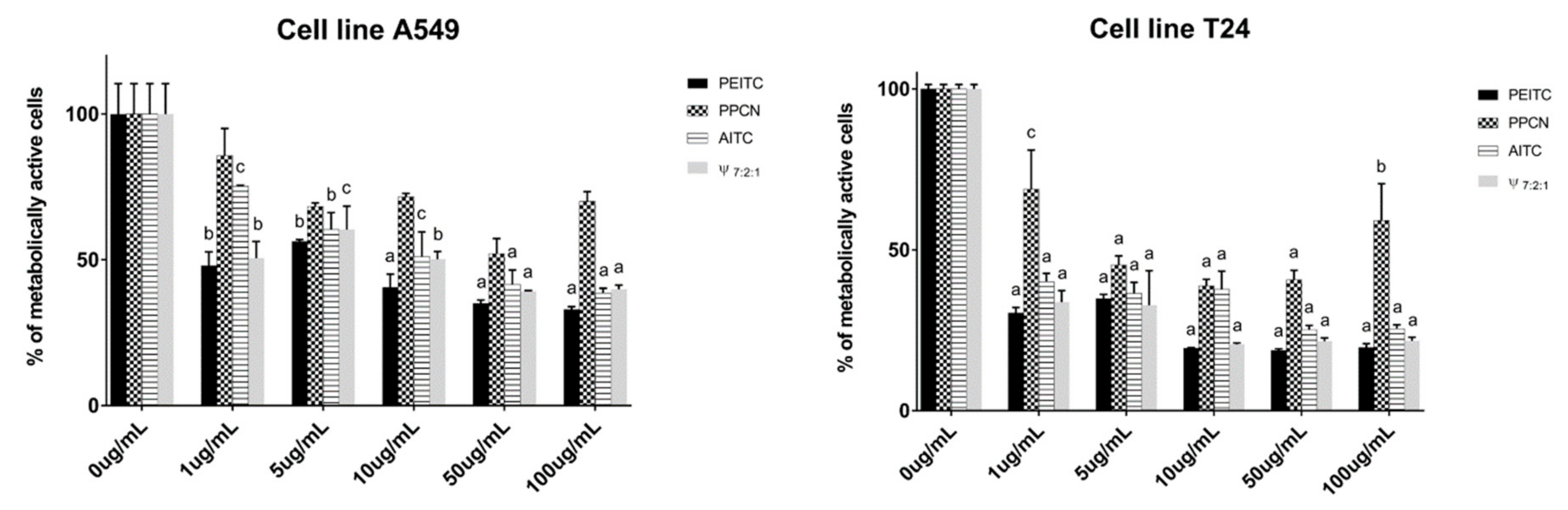

3.2. Biological Activities

3.2.1. Antimicrobial Effect of Horseradish and Its Main Volatiles

3.2.2. Cytotoxic Activity of Horseradish and Its Main Volatiles

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saladino, F.; Bordin, K.; Luciano, F.B.; Franzón, M.F.; Mañes, J.; Meca, G. Antimicrobial activity of the glucosinolates. In Glucosinolates; Mérillon, J.-M., Ramawat, K.G., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 249–274. [Google Scholar]

- Mazarakis, N.; Snibson, K.; Licciardi, P.V.; Karagiannis, T.C. The potential use of l-sulforaphane for the treatment of chronic inflammatory diseases: A review of the clinical evidence. Clin. Nutr. 2019, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pendleton, J.N.; Gorman, S.P.; Gilmore, B.F. Clinical relevance of the eskape pathogens. Expert Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther. 2013, 11, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, W.W. Seed production in horseradish. J. Hered. 1949, 40, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blažević, I.; Montaut, S.; Burčul, F.; Olsen, C.E.; Burow, M.; Rollin, P.; Agerbirk, N. Glucosinolate structural diversity, identification, chemical synthesis and metabolism in plants. Phytochemistry 2020, 169, 112100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, R.A. Isothiocyanates, nitriles and thiocyanates as products of autolysis of glucosinolates in cruciferae. Phytochemistry 1976, 15, 759–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochkoeppler, A.; Palmieri, S. Kinetic properties of myrosinase in hydrated reverse micelles. Biotechnol. Progr. 1992, 8, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blažević, I.; Maleš, T.; Ruščić, M. Glucosinolates of Lunaria annua: Thermal, enzymatic, and chemical degradation. Chem. Nat. Comp. 2014, 49, 1154–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedelsbäck Bladh, K.; Olsson, K.; Yndgaard, F. Evaluation of glucosinolates in nordic horseradish (Armoracia rusticana). Bot. Lith. 2013, 19, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agneta, R.; Lelario, F.; De Maria, S.; Mollers, C.; Bufo, S.A.; Rivelli, A.R. Glucosinolate profile and distribution among plant tissues and phenological stages of field-grown horseradish. Phytochemistry 2014, 106, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciska, E.; Horbowicz, M.; Rogowska, M.; Kosson, R.; Drabińska, N.; Honke, J. Evaluation of seasonal variations in the glucosinolate content in leaves and roots of four european horseradish (Armoracia rusticana) landraces. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2017, 67, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Agneta, R.; Möllers, C.; Rivelli, A.R.; Evolution, C. Horseradish (Armoracia rusticana), a neglected medical and condiment species with a relevant glucosinolate profile: A review. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2013, 60, 1923–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grob, K.; Matile, P. Capillary GC of glucosinolate-derived horseradish constituents. Phytochemistry 1980, 19, 1789–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, H.; Harada, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Nakajima, M.; Tabeta, H. Characteristic odorants of wasabi (Wasabia japonica matum), japanese horseradish, in comparison with those of horseradish (Armoracia Rusticana). ACS Sym Ser. Biotech. Impr. Food Flav. 1996, 637, 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Petrović, S.; Drobac, M.; Ušjak, L.J.; Filipović, V.; Milenković, M.; Niketić, M. Volatiles of roots of wild-growing and cultivated Armoracia macrocarpa and their antimicrobial activity, in comparison to horseradish, A. rusticana. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 109, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekić, M.S.; Radulović, N.S.; Stojanović, N.M.; Ranđelović, P.J.; Stojanović-Radić, Z.Z.; Najman, S.; Stojanović, S. Spasmolytic, antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities of 5-phenylpentyl isothiocyanate, a new glucosinolate autolysis product from horseradish (Armoracia rusticana P. Gaertn., B. Mey. & Scherb., Brassicaceae). Food Chem. 2017, 232, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hayes, J.D.; Kelleher, M.O.; Eggleston, I.M. The cancer chemopreventive actions of phytochemicals derived from glucosinolates. Eur. J. Nutr. 2008, 47, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.M.; Kim, J.; Du, W.X.; Wei, C.I. Bactericidal activity of isothiocyanate against pathogens on fresh produce. J. Food Protect. 2000, 63, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, A.E.; Martine, B.; Bindler, F.; Marchioni, E.; Lintz, A.; Ennahar, S. In vitro efficacies of various isothiocyanates from cruciferous vegetables as antimicrobial agents against foodborne pathogens and spoilage bacteria. Food Control 2013, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutters, N.T.; Mampel, A.; Kropidlowski, R.; Biehler, K.; Gunther, F.; Balu, I.; Malek, V.; Frank, U. Treating urinary tract infections due to MDR E. coli with isothiocyanates—A phytotherapeutic alternative to antibiotics? Fitoterapia 2018, 129, 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Poppel, G.; Verhoeven, D.T.; Verhagen, H.; Goldbohm, R.A. Brassica vegetables and cancer prevention. In Advances in Nutrition and Cancer 2; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1999; pp. 159–168. [Google Scholar]

- Conaway, C.; Yang, Y.M.; Chung, F.L. Isothiocyanates as cancer chemopreventive agents: Their biological activities and metabolism in rodents and humans. Curr. Drug Metab. 2002, 3, 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, I.K.; Choi, K.S.; Kim, D.H.; Choi, I.H.; Kim, L.S.; Bak, W.C.; Choi, J.W.; Shin, S.C. Fumigant activity of plant essential oils and components from horseradish (Armoracia rusticana), anise (Pimpinella anisum) and garlic (Allium sativum) oils against Lycoriella ingenua (Diptera: Sciaridae). Pest Manag. Sci. 2006, 62, 723–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chemat, F.; Vian, M.A.; Cravotto, G. Green extraction of natural products: Concept and principles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 8615–8627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vian, M.A.; Fernandez, X.; Visinoni, F.; Chemat, F. Microwave hydrodiffusion and gravity, a new technique for extraction of essential oils. J. Chromatogr. A 2008, 1190, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamadi, M.; Shamspur, T.; Mostafavi, A. Comparison of microwave-assisted distillation and conventional hydrodistillation in the essential oil extraction of flowers Rosa damascena Mill. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2013, 25, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahmoune, F.; Spigno, G.; Moussi, K.; Remini, H.; Cherbal, A.; Madani, K. Pistacia lentiscus leaves as a source of phenolic compounds: Microwave-assisted extraction optimized and compared with ultrasound-assisted and conventional solvent extraction. Ind. Crops Prod. 2014, 61, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blažević, I.; Đulović, A.; Čikeš Čulić, V.; Burčul, F.; Ljubenkov, I.; Ruščić, M.; Generalić Mekinić, I. Bunias erucago L.: Glucosinolate profile and in vitro biological potential. Molecules 2019, 24, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosser, K.; van Dam, N.M. A straightforward method for glucosinolate extraction and analysis with high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC). J. Vis. Exp. 2017, 121, e55425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.D.; Tokuhisa, J.G.; Reichelt, M.; Gershenzon, J. Variation of glucosinolate accumulation among different organs and developmental stages of Arabidopsis thaliana. Phytochemistry 2003, 62, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wathelet, J.P.; Iori, R.; Leoni, O.; Quinsac, A.; Palmieri, S. Guidelines for glucosinolate analysis in green tissues used for biofumigation. Agroindustria 2004, 3, 257–266. [Google Scholar]

- Blažević, I.; Mastelić, J. Free and bound volatiles of rocket (Eruca sativa Mill.). Flavour Frag. J. 2008, 23, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezić, N.; Vuko, E.; Dunkić, V.; Ruščić, M.; Blažević, I.; Burčul, F. Antiphytoviral activity of sesquiterpene-rich essential oils from four croatian Teucrium species. Molecules 2011, 16, 8119–8129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, R.P. Identification of Essential Oil Components by Gas Chromatography/Quadrupole Mass Spectroscopy; Allured Carol Stream: Carol Stream, IL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kjær, A.; Ohashi, M.; Wilson, J.M.; Djerassi, C. Mass spectra of isothiocyanates. Acta Chem. Scand. 1963, 17, 2143–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, G.F.; Daxenbichler, M.E. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry of nitriles, isothiocyanates and oxazolidinethiones derived from cruciferous glucosinolates. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1980, 31, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rončević, T.; Vukičević, D.; Ilić, N.; Krče, L.; Gajski, G.; Tonkić, M.; Goić-Barišić, I.; Zoranić, L.; Sonavane, Y.; Benincasa, M.; et al. Antibacterial activity affected by the conformational flexibility in glycine-lysine based alpha-helical antimicrobial peptides. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 2924–2936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CLSI. Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts, 3rd ed.; Approved Standard; CLSI document M27-A3; CLSI document M27-A3; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 26th ed.; CLSI Supplement M100S; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Blažević, I.; Đulović, A.; Maravić, A.; Čikeš Čulić, V.; Montaut, S.; Rollin, P. Antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities of Lepidium latifolium L. Hydrodistillate, extract and its major sulfur volatile allyl isothiocyanate. Chem. Biodivers. 2019, 16, e1800661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Gendy, A.A.; Nematallah, K.A.; Zaghloul, S.S.; Ayoub, N.A. Glucosinolates profile, volatile constituents, antimicrobial, and cytotoxic activities of Lobularia libyca. Pharm. Biol. 2016, 54, 3257–3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, T.-C. Theoretical basis, experimental design, and computerized simulation of synergism and antagonism in drug combination studies. Pharmacol. Rev. 2006, 58, 621–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compusyn. Available online: http://www.combosyn.com (accessed on 4 February 2019).

- Choi, K.-D.; Kim, H.-Y.; Shin, I.-S. Antifungal activity of isothiocyanates extracted from horseradish (Armoracia rusticana) root against pathogenic dermal fungi. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2017, 26, 847–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Zhang, Y. Dietary isothiocyanates inhibit the growth of human bladder carcinoma cells. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 2004–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, K.; Hussein, U.K.; Anupalli, R.; Barnett, R.; Bachaboina, L.; Scalici, J.; Rocconi, R.P.; Owen, L.B.; Piazza, G.A.; Palle, K. Allyl isothiocyanate induces replication-associated DNA damage response in NSCLC cells and sensitizes to ionizing radiation. Oncotarget. 2015, 6, 5237–5252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, Y.F.; Chen, Y.H. Induction of apoptosis in a non-small cell human lung cancer cell line by isothiocyanates is associated with p53 and p21. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2004, 42, 1711–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Glucosinolate (Trivial Name) | tR (min) | Roots (μmol/g DW) | Leaves (μmol/g DW) | [M + Na]+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aliphatic | ||||

| Allyl GSL (1) * (Sinigrin) | 2.0 | 3.53 ± 0.37 | 11.43 ± 0.26 | 302 |

| But-3-enyl GSL (2) (Gluconapin) | 4.4 | tr | tr | 316 |

| Pent-4-enyl GSL (3) (Glucobrassicanapin) | 6.0 | tr | tr | 330 |

| Branched | ||||

| sec-Butyl GSL (4) (Glucocochlearin) | 5.4 | tr | tr | 318 |

| Arylaliphatic | ||||

| 2-Phenylethyl GSL (5) (Gluconasturtiin) | 7.6 | 7.21 ± 0.25 | tr | 366 |

| Indole | ||||

| Indol-3-yl GSL (6) (Glucobrassicin) | 6.7 | 0.15 ± 0.08 | tr | 391 |

| Total (μmol/g DW) | 10.89 ± 0.70 | 11.43 ± 0.26 |

| Compound | RI1 | RI2 | HD | MAD | MHG | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roots | Leaves | Roots | Leaves | Roots | Leaves | |||

| But-3-enenitrile a,b,c | 1272 | - | 6.58 | 1.64 | 1.05 | 37.16 | 11.76 | 37.05 |

| (E)-Hex-2-enal a,b,c | 1311 | - | - | 1.12 | - | 0.12 | - | 0.11 |

| sec-Butyl isothiocyanate a,c | 1360 | 936 | 1.04 | 4.31 | 0.17 | 2.76 | 0.04 | 0.10 |

| (Z)-Pent-2-en-1-ol a,b,c | 1393 | - | - | 0.07 | - | - | - | 0.06 |

| Allyl isothiocyanate (AITC) a,b,c | 1429 | 879 | 46.36 | 73.45 | 14.29 | 54.77 | 13.81 | 52.36 |

| (Z)-Hex-3-en-1-ol a,b,c | 1452 | 862 | 0.30 | 5.22 | 0.03 | 0.74 | 0.15 | 1.65 |

| (E)-Hex-2-en-1-ol a,b,c | 1474 | - | - | 0.22 | - | 0.04 | - | 0.02 |

| Nonanal a,b,c | 1481 | - | - | - | - | 0.41 | - | - |

| Allyl thiocyanate a,c | 1504 | - | 1.15 | 1.76 | 0.32 | 0.41 | 0.26 | 0.31 |

| But-3-enyl isothiocyanate a,b,c | 1514 | 992 | 0.51 | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| Pent-4-enyl isothiocyanate a,c | 1589 | 1094 | 0.24 | 0.32 | 0.20 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.02 |

| Benzeneacetaldehyde a,b,c | 1676 | - | - | 0.12 | - | 0.37 | - | 0.19 |

| 2-Methoxy-3-(1-methylpropyl)pyrazine a,b | - | 1173 | 0.37 | - | 0.10 | - | 0.06 | - |

| 2-Phenylethyl alcohol a,b,c | 1914 | - | - | 0.03 | - | - | 0.04 | 0.06 |

| 3-Phenylpropanenitrile (PPCN) a,b,c | 2024 | 1248 | 15.44 | 1.69 | 18.61 | 0.49 | 34.44 | 0.23 |

| Octanoic acid a,b,c | 2056 | - | 0.01 | 0.15 | 0.24 | 0.25 | - | 0.00 |

| Nonanoic acid a,b,c | 2154 | - | 0.01 | - | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.70 | 0.12 |

| (E)-β-Ionone a,b,c | - | 1493 | - | - | - | 1.28 | - | - |

| 2-Phenylethyl isothiocyanate (PEITC) a,b,c | 2197 | 1513 | 27.61 | 2.81 | 62.82 | 0.29 | 30.53 | 0.07 |

| Decanoic acid a,b,c | 2254 | - | 0.01 | 0.96 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.83 | 0.77 |

| Undecanoic acid a,b,c | 2351 | - | - | 0.57 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.44 | 0.41 |

| Benzoic acid a,b,c | 2371 | - | - | - | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.14 |

| Tridecanoic acid a,b,c | 2561 | - | - | 0.33 | - | - | 0.13 | 0.14 |

| Tetradecanoic acid a,b,c | 2645 | - | - | 0.74 | - | - | 0.35 | 0.33 |

| Pentadecanoic acid a,b,c | 2744 | - | - | 0.50 | - | - | 0.46 | 0.40 |

| Total sum (%) | 99.66 | 96.18 | 98.36 | 99.55 | 94.22 | 94.60 | ||

| Yield (ng/g) | 66.34 | 138.96 | 35.43 | 3.96 | 7.57 | 3.39 | ||

| Isothiocyanates (%) | 75.76 | 81.09 | 77.58 | 57.94 | 44.46 | 52.59 | ||

| Nitriles (%) | 22.02 | 3.33 | 19.66 | 37.65 | 46.20 | 37.28 | ||

| Others (%) | 1.88 | 11.76 | 1.12 | 3.96 | 3.56 | 4.73 | ||

| Species | Strain Origin | HD | MAD | MHG | Agent c | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC | MBC b | MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | |||

| Gram-positive bacteria | ||||||||

| Listeria monocytogenes | ATCC 19111 | 50 | 200 | 25 | 100 | 7.5 | 30 | ≤1 (S) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | ATCC 29213 | 25 | >100 | 25 | >100 | 30 | >120 | 0.25 (S) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Clinical/MRSA | 50 | >200 | 12.5 | >50 | 3.75 | >15 | ≥16 (R) |

| Enterococcus faecalis | ATCC 29212 | 50 | 200 | 50 | 200 | 15 | 60 | ≤1 (S) |

| Streptococcus pyogenes | ATCC 19615 | 50 | 200 | 50 | 200 | 15 | 60 | ≤1 (S) |

| Bacillus cereus | Food | 50 | 50 | 25 | 25 | 15 | 15 | ≤1 (S) |

| Gram-negative bacteria | ||||||||

| Salmonella Typhimurium | WDCM 00031 | 50 | 100 | 25 | 50 | 15 | 30 | ≤1 (S) |

| Escherichia coli | ATCC 25922 | 50 | 50 | 25 | 50 | 15 | 30 | 0.5 (S) |

| Escherichia coli | Clinical | 100 | 200 | 50 | 100 | 15 | 30 | ≤1 (S) |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | ATCC 13883 | 100 | 200 | 100 | 100 | 30 | 30 | 0.12 (S) |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Clinical | 200 | 400 | 100 | 100 | 30 | 30 | ≥16 (R) |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | ATCC 19606 | 50 | 100 | 25 | 50 | 7.5 | 15 | 1 (S) |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | Clinical | 50 | 100 | 25 | 50 | 7.5 | 15 | ≥16 (R) |

| Fungi | MIC50 | MIC90 | MIC50 | MIC90 | MIC50 | MIC90 | MIC90 | |

| Candida albicans | Environmental | <0.78 | ≤0.78 | <0.39 | ≤0.39 | <0.12 | ≤0.12 | 1 (S) |

| Penicillium notatum | Food | 3.125 | 6.25 | 3.125 | 6.25 | 0.47 | 0.94 | 0.5 (S) |

| Aspergillus niger | Food | 3.125 | 6.25 | 1.56 | 3.125 | 0.47 | 0.94 | 0.5 (S) |

| Species | Strain Origin | PEITC | PPCN | Ψ7:2:1c | Ψ4:4:2 | Ψ2:3:5 | Agent d | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC | MBC b | MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | |||

| Gram-positive bacteria | ||||||||||||

| Listeria monocytogenes | ATCC 19111 | 125 | 500 | 125 | 1000 | 12.5 | 50 | 7.5 | 30 | 25 | 100 | ≤1 (S) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | ATCC 29213 | 31.25 | >125 | 500 | 2000 | 25 | >100 | 30 | >120 | 25 | >100 | 0.25 (S) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Clinical/MRSA | 15.6 | 62.5 | 500 | 2000 | 25 | 50 | 7.5 | 30 | 50 | 100 | ≥16 (R) |

| Enterococcus faecalis | ATCC 29212 | 125 | 500 | 500 | 2000 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 15 | 60 | 50 | 200 | ≤1 (S) |

| Streptococcus pyogenes | ATCC 19615 | 62.5 | 250 | 500 | 2000 | 25 | 100 | 15 | 60 | 50 | 200 | ≤1 (S) |

| Bacillus cereus | Food | 62.5 | 62.5 | 500 | 1000 | 25 | 25 | 15 | 15 | 50 | 50 | ≤1 (S) |

| Gram-negative bacteria | ||||||||||||

| Salmonella Typhimurium | WDCM 00031 | 62.5 | 125 | 500 | 1000 | 25 | 50 | 15 | 30 | 50 | 100 | ≤1 (S) |

| Escherichia coli | ATCC 25922 | 15.6 | 31.25 | 500 | 1000 | 25 | 25 | 30 | 60 | 50 | 50 | 0.5 (S) |

| Escherichia coli | Clinical | 250 | 500 | 500 | 1000 | 50 | 100 | 15 | 30 | 100 | 200 | ≤1 (S) |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | ATCC 13883 | 250 | 250 | 500 | 1000 | 50 | 100 | 30 | 30 | 100 | 200 | 0.12 (S) |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Clinical | 500 | 500 | 500 | 1000 | 100 | 100 | 30 | 30 | 200 | 400 | ≥16 (R) |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | ATCC 19606 | 125 | 250 | 250 | 500 | 25 | 50 | 7.5 | 15 | 50 | 100 | 1 (S) |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | Clinical | 31.25 | 31.25 | 125 | 500 | 12.5 | 25 | 7.5 | 15 | 25 | 50 | ≥16 (R) |

| Fungi | MIC50 | MIC90 | MIC50 | MIC90 | MIC50 | MIC90 | MIC50 | MIC90 | MIC50 | MIC90 | MIC90 | |

| Candida albicans | Environmental | <1.95 | ≤1.95 | 125 | 250 | 0.39 | 0.78 | 0.12 | 0.23 | 0.78 | 1.56 | 1 (S) |

| Penicillium notatum | Food | 3.9 | 7.8 | 31.25 | 62.5 | 3.125 | 6.25 | 0.47 | 0.94 | 3.125 | 6.25 | 0.5 (S) |

| Aspergillus niger | Food | 1.95 | 3.9 | 31.25 | 125 | 3.125 | 6.25 | 0.94 | 1.875 | 6.25 | 12.5 | 0.5 (S) |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Popović, M.; Maravić, A.; Čikeš Čulić, V.; Đulović, A.; Burčul, F.; Blažević, I. Biological Effects of Glucosinolate Degradation Products from Horseradish: A Horse that Wins the Race. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom10020343

Popović M, Maravić A, Čikeš Čulić V, Đulović A, Burčul F, Blažević I. Biological Effects of Glucosinolate Degradation Products from Horseradish: A Horse that Wins the Race. Biomolecules. 2020; 10(2):343. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom10020343

Chicago/Turabian StylePopović, Marijana, Ana Maravić, Vedrana Čikeš Čulić, Azra Đulović, Franko Burčul, and Ivica Blažević. 2020. "Biological Effects of Glucosinolate Degradation Products from Horseradish: A Horse that Wins the Race" Biomolecules 10, no. 2: 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom10020343

APA StylePopović, M., Maravić, A., Čikeš Čulić, V., Đulović, A., Burčul, F., & Blažević, I. (2020). Biological Effects of Glucosinolate Degradation Products from Horseradish: A Horse that Wins the Race. Biomolecules, 10(2), 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom10020343