Abstract

Algae have long been exploited commercially and industrially as food, feed, additives, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, and fertilizer, but now the trend is shifting towards the algae-mediated green synthesis of nanoparticles (NPs). This trend is increasing day by day, as algae are a rich source of secondary metabolites, easy to cultivate, have fast growth, and are scalable. In recent era, green synthesis of NPs has gained widespread attention as a safe, simple, sustainable, cost-effective, and eco-friendly protocol. The secondary metabolites from algae reduce, cap, and stabilize the metal precursors to form metal, metal oxide, or bimetallic NPs. The NPs synthesis could either be intracellular or extracellular depending on the location of NPs synthesis and reducing agents. Among the diverse range of algae, the most widely investigated algae for the biosynthesis of NPs documented are brown, red, blue-green, micro and macro green algae. Due to the biocompatibility, safety and unique physico-chemical properties of NPs, the algal biosynthesized NPs have also been studied for their biomedical applications, which include anti-bacterial, anti-fungal, anti-cancerous, anti-fouling, bioremediation, and biosensing activities. In this review, the rationale behind the algal-mediated biosynthesis of metallic, metallic oxide, and bimetallic NPs from various algae have been reviewed. Furthermore, an insight into the mechanism of biosynthesis of NPs from algae and their biomedical applications has been reviewed critically.

1. Introduction

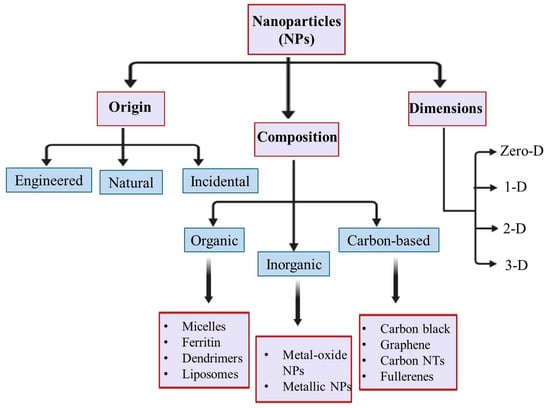

The last few decades have witnessed accelerated development in the field of nanotechnology attributed to the exceptional physio-chemical properties of nanoparticles (NPs) and associated nanomaterials. Nanotechnology has infiltrated almost every discipline of science to create novel alternatives aimed at solving different research-related bottlenecks [1]. The origin of nanobiotechnology is the fabrication of nanoscale particles by virtue of biological moieties that can influence the physical characteristics of NPs [2]. Synthesis of NPs of diverse sizes and shapes has underpinned great interest due to their novel properties as compared to their bulk counterparts. Consistency in the chemical, biochemical, and physicochemical properties of materials varies immensely at the nanoscale mainly due to the high aspect ratio of surface area to volume [3,4]. This leads to considerable differences in mechanical properties, melting point, optical absorption, thermal, electrical conductivity, biological, and catalytic activities [5]. NPs bridge the gap between bulk materials and atomic or molecular structures. NPs usually ranging in size from 1 to 100 nm and have been classified on the basis of origin, dimensions, and structural configurations, as shown in Figure 1 [6].

Figure 1.

NPs (nanoparticles; usually ranging in size from 1 to 100 nm) classification on the basis of origin, dimensions, and structural configurations.

Due to unique morphological (shape, size, and charge distribution) and physico-chemical properties of NPs, they find applications in almost every discipline of science, like space, energy, defense, communication, biomedicine, and agriculture. Use of NPs in disease diagnosis, imaging, treatment, drug delivery, tissue engineering, and cancer therapeutics is also increasing tremendously [7]. However, application of NPs in biological entities, especially humans, is very critical, and the NPs used in biomedical applications should preferably be from green sources [8]. Taking into consideration various factors, such as biocompatibility, bioavailability, bio-distribution, and most importantly biosafety of NPs, the current trend of synthesis of NPs is moving towards the safer side [9].

NPs are mostly synthesized by physical and chemical methods such laser ablation, mechanical milling, electro explosion, and sol-gel, but they are hazardous for environmental and human health [10]. The trend to synthesize NPs from alternative, environmentally safe, cost-effective, and non-toxic green methods is increasing [11]. Organisms such as algae, fungi, bacteria, and plants allow green synthesis of NPs that are free from impurities [12,13]. These biological systems possess various biological entities which behave as both reducing and capping agents in NP generation, either intracellularly or extracellularly [14]. Proteins, peptides, and functional groups (carbonyl, thiol, hydroxyl, and amine) present in biological entities reduce precursor salt into NPs called reducing or stabilizing agents [15]. They cap and stabilize NPs at the same time, hence this type of synthesis is relatively simple, reproducible, and stable [9].

The biosynthesis of NPs can be controlled by various physical factors, such as pH, concentration of metal precursor and bio-extract, contact time of reaction mixture, exposure to any light source, and temperature. These factors control the nucleation, growth, aging, agglomeration, and stabilization of NPs, which in turn can alter the size, shape, and crystallinity of the synthesized NPs [16,17,18,19]. After synthesis of NPs, they are subjected to various microscopic and spectroscopic characterization techniques to find out their unique physico-chemical characteristics. Determination of the exact morphological (size, shape, and particle distribution) and physico-chemical properties of NPs is very critical in their biomedical applications [20]. The most commonly employed microscopic techniques used to find out the size and morphological properties of NPs include transmission electron microscopy (TEM), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), atomic force microscopy (AFM), and high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM), and are employed to determine the size and morphological features of NPs [21,22]; whereas to analyze the structure, composition, and crystallinity of synthesized NPs, UV-visible spectroscopy (UV-Vis), energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS), selected area electron diffraction (SAED), dynamic lights scattering (DLS), X-ray diffraction (XRD), X-ray photo-electron spectroscopy (XPS), and fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) are used [23,24].

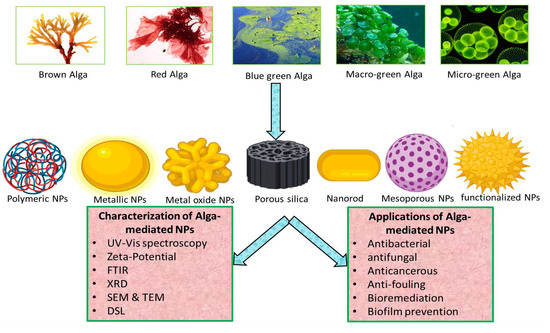

For green synthesis, the shift towards the use of algae is increasing, as they are a rich source of secondary metabolites, proteins, peptides, and pigments, which serve as nano-biofactories [25]. Moreover, they have fast growth rate, easy harvesting, and cost-effective scale-up, making them good candidates for biological synthesis of NPs [26]. Algae are the most primitive organisms inhabiting diverse ecosystems and dominant photosynthetic organisms on Earth [27]. Algae possess the ability to hyper-accumulate metals and transform them into NPs, making them the best choice for green synthesis [9]. Many metallic and metal oxides NPs are synthesized from various classes of algae, such as blue-green algae (Cyanophyceae), brown algae (Phaeophyceae), green algae (Chlorophyceae), and red algae (Rhodophyceae), as shown in Figure 2 [28,29].

Figure 2.

Graphical representation of algae-mediated biosynthesis, characterization and applications of NPs.

Algae have long been exploited commercially and industrially as food, feed, additives, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, fertilizer, and bioremediation agents. The rationale behind the use of algae for green synthesis is that no external reducing or capping agents are required, low energy input, low cost synthesis, and simple reaction. However, algal use for NPs synthesis, a branch known as phyco-nanotechnology, is still in its infancy. Henceforth, this review critically reviews the potential of algae-based biosynthesis of NPs, mechanisms involved in their synthesis, and significant industrial/biomedical applications of these algae-mediated NPs.

2. Mechanism Involved in the Algae-Mediated Biosynthesis of NPs

Algae are known to hyper-accumulate heavy metal ions and possess an exceptional capability to remodel them into more malleable forms. Because of these alluring attributes, algae have been foreseen as model organisms for fabricating various types of nanomaterials, especially metallic NPs [27]. The biosynthesis of NPs is initiated when a precursor metal solution is incubated with algal extract. The biochemical compounds in algae, such as antioxidants, pigments, phycobilins, chlorophylls, oils, minerals, carbohydrates, fats, proteins, polyunsaturated fatty acids, and various phytochemicals, aid in reducing charge of metal ion to zero valent state. Bio-reduction is a three-phase process, in which the activation phase involves metal ion reduction and nucleation due to the enzymes secreted by algal cells evident from the color change of solution. In the growth phase, nucleated metal elements amalgamate with each other, forming NPs of different sizes and shapes which are thermodynamically stable. The final shape of NPs is acquired in final termination phase. Factors such as temperature, pH, time, static conditions, substrate concentration, and stirring control the physical characteristics of NPs [30]. Herein, we have specifically discussed the mechanism involved in algae-mediated biosynthesis of AuNPs, which is almost same as that involved in synthesis of other NPs.

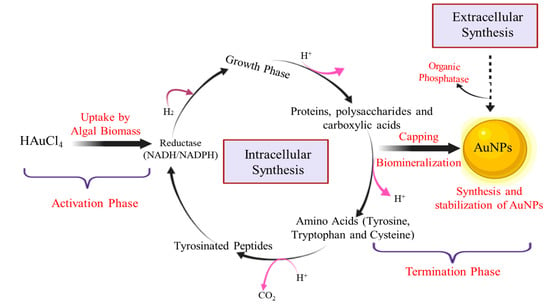

Biosynthesis of NPs from algae could either be intracellular or extracellular depending on the location of NPs formed. The intracellular method is a dose-dependent process in which NP biosynthesis occurs inside the algal cell, as shown in Figure 3. NADPH or NADPH-dependent reductase released during the metabolic processes such as nitrogen fixation, photosynthesis, and respiration act as reducing agents [31,32]. AuNPs were synthesized intracellularly by incubating chloroauric acid with Ulva intestinalis and Rhizoclonium fontinale algae at 20 °C for 72 h. A visible purple color change of thallus from green indicated the biosynthesis of AuNPs. Furthermore, incubating gold metal solution with biomass resulted in no color change, which established that no intracellular enzyme or metabolites were associated with the bio-reduction process. In another experiment, the silica gel suspension encapsulated Klebsormidium flaccidum showed a visual purple color change of chloroplast from green, which is an indication of the potential of cells to reduce gold precursor (chloroauric acid). This was further confirmed by TEM analysis, which showed dark-colored spots within the thylakoid membrane, indicating the presence of reduced gold precursor salt by the NADPH-dependent reductase enzyme or NADPH [33]. Similarly, Senapati and co-workers (2012) demonstrated the intracellular synthesis of AuNPs by the algal cell wall in Tetraselmis kochinensis. UV-visible spectroscopy clearly proved that there was no extracellular synthesis. The AuNPs were more densely present near the cell wall rather than the cytoplasmic area, which is most likely due to the presence of bioactive moieties responsible for bioreduction [34].

Figure 3.

Schematic illustration of mechanism involved in extracellular and intracellular synthesis of algae-mediated gold nanoparticles (AuNPs).

The extracellular mode of synthesis occurs when metal ions become attached to the surface of algal cells and metabolites such as proteins, lipids, non-protein RNA, DNA, ions, pigments, and enzymes reduce them at the surface [35]. The extracellular mode of synthesis is more convenient as NPs are easily purified, however some essential pre-treatments like washing and blending of algal biomass are required [36]. Certain physio-chemical conditions like pH, temperature, and type and initial concentration of metal and substrate influence the size, shape, and agglomeration of NPs [32,37]. Higher pH prevents the agglomeration of NPs by enhancing the reducing power of functional groups [18,38]. Basic pH helps in the capping and stabilization of NPs by interacting with the amine groups of surface-bound proteins and their residual amino acids [39]. Extracellular synthesis of AuNPs synthesized by S. platensis at varying concentrations of chloroauric acid was confirmed by the presence of surface plasmon peak at 530 nm, which gives a clue of the involvement of proteins, enzymes, and biomolecules in algae-mediated synthesis of NPs [40].

3. Biosynthesis of NPs from Algae

Algae are a diverse group of photoautotrophic, eukaryotic, aquatic, unicellular/multicellular organisms and have been classified on the basis of the pigmentation they release, which includes brown algae (phaeophytes), red algae (rhodophytes), and green algae (chlorophytes) [41,42]. Algae are commonly used for the biosynthesis of various metallic and metal oxide NPs, because they grow rapidly, are easy to handle, and their biomass growth, on average, is ten-times faster than higher plants. Different algal strains have been researched for the green synthesis of different types of NPs to date. Herein, the literature is critically reviewed for biosynthesis of NPs from different classes of algae in detail.

3.1. Brown Algae-Mediated Biosynthesis of NPs

Brown algae belongs to the order Fucales and family Sargassaceae. The dominant components of Fucales are sterols such as cholesterols, fucosterols, sulfated polysaccharides, and functional groups like glucuroronic acid, muramic acid, alginic acid, and vinyl derivatives which act as reducing as well as capping agents for the synthesis of NPs [43]. Currently, various metallic (silver and gold) and metal oxide (Zinc oxide and titanium oxide) NPs have been synthesized from different species of brown algae, as discussed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Brown algae-mediated biosynthesis of metallic NPs.

Metallic NPs such as silver (AgNPs), gold (AuNPs), and copper (CuNPs) are some of the most widely synthesized NPs from brown algae [11,44,45,50,51]. Among different metallic NPs, more than half of the reported data in literature are about the synthesis of AgNPs from different algae strains. This is because the AgNPs possess superior physico-chemical characteristics as compared to their bulk forms, thus making them extremely useful in different industries, such as in jewelry, paints, textile, dental alloys, drug-delivery, and wound-healing [76,77,78]. In order to biosynthesize AgNPs from brown algae, a variety of species have been reported in literature, such as Gelidiella acerosa, Turbinaria conoides, Desmarestia menziesii, Sargassum polycystum, Padina pavonica, and Cystophora moniliformis [11,44,45,50,51]. In one report, spherical AgNPs (96 nm) have been synthesized extracellularly from T. conoides, which exhibited tremendous anti-bacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermis, Escherichia coli, Candida albicans, Aspergillus niger, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa [44]. The organic moieties, amines, polyamines, free hydroxyl, and carbonyl groups of Turbinaria species (T. ornate and T. conoides) have been reported to act as reducing agents of precursor silver salts used in the synthesis of AgNPs [48,79].

The other type of NP that has been extensively synthesized from brown algae strains is AuNPs, which has exhibited a number of medicinally important bio-activities, such as anti-fouling, anti-coagulant, and anti-bacterial activities [47,50,80]. Among all reported species of brown algae, T. conoides is one of the most prominent types that are traditionally used in the generation of AuNPs. A variety of shapes, like polydispersed, rectangular, spherical, and triangular AuNPs, were generated from T. conoides by extracellular pathway [81]. In most of the cases, AuNPs were synthesized by using chloroauric acid as a precursor of gold ions along with T. conoides. Another important species of brown algae, Laminaria japonica, has also been investigated in the green synthesis of AuNPs. L. japonica is a rich source of bio-active components such as polyphenols, peptides, proteins, vitamins, carotenoids, and fibers [80]. Spherical (15–20 nm) AuNPs were extracellularly synthesized from L. japonica with the involvement of phytochemicals and functional groups that behaved as reducing and capping agents [50]. Other species of brown algae, such as Fucus vesiculosus, Sargassum myriocystum, Ecklonia cava, Sargassum wightii, Stereospermum marginatum, Padina gymnospora, Dictyota bartayresianna, and Cystoseira baccata, have also been reported in the biosynthesis of AuNPs (Table 1).

In addition to the metallic NPs, brown algae have also been reported for biosynthesizing various metal oxide NPs, such as zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnONPs) and titanium oxide nanoparticles (TiO2NPs) [82]. According to one study, ZnONPs were synthesized by mixing dried algal powder from S. muticum with distilled water and heated until completely mixed, then zinc acetate salt solution was added, and it was placed on continuous stirring for hours until the generation of NPs. The synthesized ZnONPs were hexagonal in shape, ranging from 35 to 57 nm in size, and were capped by bioactive functional groups like sulfate, amines, hydroxyl, and carbonyl [11,83].

3.2. Red Algae-Mediated Biosynthesis of NPs

Red algae belong to the family Rhodophyta and are primarily used as food in many countries due to their unique flavour and the richness of several important vitamins and proteins [84]. These vitamins and proteins could be the best contenders for reduction and stabilization in algae-mediated biosynthesis of NPs. However, the synthesis of NPs from seaweed red algae is still in the developmental stages due to of its self-aggregation, slow crystallization growth, and stability issues [54,85]. Among various red algae strains, Porphyra vietnamensis is one of the most evident species which has been reported numerous times for synthesis of various types of NPs, due to the presence of a strong reducing agent, such as sulfated polysaccharides, that contain anionic disaccharides units, comprised of 3-linked-d-galactosyl residues flashing with 4-linked 3,6-anhydro-l-galactose and 6-sulfate residues [86,87]. A number of red algae strains have been reported in literature for the biosynthesis of AgNPs, such as Kappaphycus alvarezii, Palmaria decipiens, Gelidiella acerosa, Gracilaria dura, Kappaphycus sp., and many others, as summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Red algae-mediated biosynthesis of metallic NPs.

Red algae-mediated AgNPs are efficient, eco-friendly, less time consuming, and cost-effective in comparison to the physio-chemical method [108]. The size and shape of NPs are the crucial factors that matter a lot in biomedical applications. It has been reported that the AgNPs synthesized from different red algae strains are mainly spherical in shape and ranging in size from 20 to 60 nm [88]. These extracellularly synthesized AgNPs show anti-microfouling activity, which is of great interest in the medical field [88,109]. It requires a number of steps in the intracellular synthesis of NPs to evacuate microfouling, but the prevention of microfouling in extracellular synthesis is a single step process [110]. Gelidium amansii is another red algae that is reported in the biosynthesis of AgNPs as well as in the minimization of micro-fouling by the 96-well method [89,111].

A limited number of studies have been carried on the red algae-mediated biosynthesis of AuNPs in comparison to AgNPs. Lemanea fluviatilis is one such marine red alga that is investigated for the biosynthesis of AuNPs, using chloroauric acid as a precursor salt. It generated face-centered cubic and poly-dispersed crystalline AuNPs of 5.9 nm in size which were observed by TEM [112,113]. In another report, Corallina officinalis has also been reported for extracellular synthesis of spherical AuNPs with reducing agents like hydroxyl, phenol, and carbonyl functional groups [95]. In addition to L. flaviatilis and C. officinalis, many other red algae species, such as Kappaphycus alvarezii, Galaxaura elongata, and Chondrus crispus, have been reported for facile biosynthesis of AuNPs [92]. Besides monometallic NPs, the red algae strain Gracilaria edulis efficiently biosynthesized bimetallic Ag-Au NPs by using different molar ratios (1:1, 1:3, and 3:1) of AgNO3 and HAuCl4 [107]. These synthesized bimetallic NPs have exhibited potent anticancerous activities against human breast cancer lines.

3.3. Blue-Green Algae-Mediated Biosynthesis of NPs

Blue-green algae have an anomalous state in the biological world and belong to the order of Chroococcales, which has two distinct families of Chroococcaceae and Entophysalidaceae. The members of these two families are distinguished by their growth habitat forming colonies [114]. They grow in dense patterns as parenchymatous cell masses found on moist rocks. Blue-green algae are photoautotrophic in nature, as they use water as an electron donor and contain two photo-pigments, chlorophyll a and carotene, which help in photosynthesis. On the basis of their morphology, they are also considered counterparts of unicellular bacteria [115]. Unlike brown and red algae, blue-green algae have also been widely exploited for the synthesis of various types of NPs, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Blue-green algae-mediated biosynthesis of NPs.

The major contributor of AgNPs by blue-green algae is Spirulina platensis. S. platensis is free floating, filamentous cyanobacteria that has multicellular trichomes with one open end and left-handed helix [135]. It also contains 60–70% vegetable protein, which is rich in essential amino acids, beta carotene, iron, natural vitamins, and essential fatty acids, which can help in reduction and capping of NPs [128]. Spherical-shaped AgNPs (2–8 nm) have been synthesized from S. platensis, which are efficiently used in pharmaceuticals, health, and food industries. Besides S. platensis, AgNPs of different sizes and shapes have also been synthesized from various other blue-green algae species, such as Oscillato riawillei (spherical, 10–25 nm), Plectonema boryanum (octahedral, 200 nm), Microchaete diplosiphon (spherical, 80 nm), and Cylindrospermum stagnale (pentagonal, 38–88 nm) [132].

Like AgNPs, S. platensis has also shown its contribution in the biosynthesis of AuNPs. Various researchers have reported the S. platensis-mediated extracellular synthesis of spherical, octahedral, and cubic AuNPs, showing the involvement of proteins and peptides as reducing agents [40,136]. Phormidium valderianum is another important type of blue-green algae, known as alkalo-tolerant Rhodococcus, which has generated intracellular mono-dispersive triangular AuNPs at wavelength of 530 nm with absorbance 1.897 by UV-Vis spectrometry [124]. The appearance of one broad peak of AuNP at 530 nm is because of surface plasmon resonance (SPR), which depends on particle size, constant di-electric medium, and surface absorbed species [137,138]. P. valderianum has also been reported for extracellular synthesis of spherical, hexagonal, and FCC (24 nm) AuNPs by using cytoplasmic metabolites as reducing agents [38,115]. Besides monometallic NPs, S. platensis has also been reported in the biosynthesis of bimetallic NPs, such as core shell Ag-AuNPs and magnetic crystalline-shaped silica-NPs with the help of extracellular proteins [62,133]. Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, another important fresh-water green algae species, was reported to be involved in the mediation of cadmium sulfide bimetallic nanoparticles (CdSNPs) [134]. CdS belongs to the II-VI group of semiconductors, possesses unique optoelectronic properties, and has been widely used in photo-catalysis, LEDs, and biosensors.

3.4. Green Algae-Mediated Biosynthesis of NPs

Green algae are divided into two main groups on the basis of their habitat as micro and macro green algae [139]. Micro green algae are unicellular and mainly cultivated/habitat in fresh water, whereas macro green algae are multicellular marine-living plant-like organisms [140]. Biosynthesis of various monometallic, bimetallic, and metal oxide NPs from green algae is currently widely practiced [58]. Herein, we have separately described the biosynthesis of NPs from both types of green algae as micro-mediated and macro-mediated biosynthesis.

3.4.1. Green Micro Algae-Mediated Biosynthesis of NPs

Micro green algae belong to the order Cladophorales and have been extensively used in various industrial, health, and biotechnological applications. They are a rich source of many essential components, such as alkaloids, phenols, flavonoids, carbohydrates, and functional groups that could behave as reducing as well as stabilizing agents in micro-mediated biosynthesis of NPs [141]. Among various monometallic NPs, AgNPs are most extensively in-vitro generated NPs from different species of micro green algae, as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Micro green algae-mediated biosynthesis of Metallic NPs.

To date, more than 20 different species of green micro algae have been exploited for biosynthesis of AgNPs. The AgNPs synthesized from different species exhibit interesting and variable physico-chemical characteristics when analyzed by different spectroscopic and microscopic techniques, such as SEM, XRD, FTIR, DLS, and EDX [13,47,143,144,145]. Almost all micro green algae species used extracellularly generate AgNPs of varying size and morphology, such as Pithophora oedogonia, (cubical and hexagonal, 24–55 nm), Chlorococcum humicola (spherical, 16 nm), Chlorella vulgaris (triangular, 28 nm), C. reinhardtii (rectangular and rounded, 1–15 nm), and Enteromorpha flexuosa (circular, 15 nm) [141,145,149,151]. Similar to AgNPs, a lot of data have been published in recent years on green micro algae-mediated biosynthesis of AuNPs, as mentioned in Table 4. Pithophora crispa from higher altitude is one of the most widely exploited species of micro algae involved in the biosynthesis of AuNPs by reducing chloroauric acid precursor salt with the help of intracellular and extracellular proteins and peptides [146]. The majority of the reported primarily metabolites involved in the biosynthesis of metallic NPs from green micro algae are proteins, peptides, cyclic compounds, and carboxylic acids [92,158,161].

Apart from AgNPs and AuNPs, micro green algae have also been used for the synthesis of semiconductor NPs. Many attempts have been done to synthesize silicon-NPs from micro green algae. Silicon-NPs are semiconductor in nature and are used as bio-indicators in many industrial wastes to identify the presence of toxic compounds. They also possess an important position in the ecological cycle, as they play essential roles in oxygen production and nutrient recycling. For this, green algae C. vulgaris was taken into account, silicon alkaloids were used as silicon precursor, and were mixed with algal extract. Silicon-NPs were synthesized by hydrolysis and poly-condensation of silicon alkaloids by peptides and proteins present in C. vulgaris extract [142]. Other than silicon-NPs, a number of other metallic, bi-metallic, metal oxide, and semiconductor NPs’ biosynthesis is in process and a lot of research and experiments are in their exponential phases.

3.4.2. Green Macro Algae-Mediated Biosynthesis of NPs

Green macro algae are also called bio-factories for the synthesis of metallic NPs, because they possess numerous valuable compounds which are responsible for reduction and capping of NPs [58,163]. Besides being involved in the synthesis of NPs, these compounds also exhibit strong anti-tumor, anti-viral, anti-bacterial, and cytotoxic effects to microbes [164]. In recent trends, various green macro algae strains have been extensively used in the generation of metallic NPs, as summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Macro green algae-mediated biosynthesis of Metallic NPs.

Ulva fasciata is one of most useful green macro algae species, and was utilized to generate nano-sized silver colloids which were further applied to cotton fabric in the presence and absence of citric acid in order to evaluate their anti-microbial efficacy [68]. In another report, Gracilaria edulis (rich in amide, carboxylic, and nitro compounds) was used for the synthesis of spherical AgNPs and octahedral ZnONPs [163,168]. Chaetomorpha linum, another important species of seaweed green macro algae, is well recognized for its ecological roles in the regulation of nutrients availability to its habitat, has been also used for the synthesize of AgNPs by catalyzing the reduction of silver ions (Ag+) to Ag0 with the help of peptides, flavonoids, and terpenoids in extracellular environment [163]. Besides AgNPs, AuNPs have also been synthesized by green macro algae species such as Prasiola crispa and Rhizoclonium fontinale [65,125]. During the past few years AuNPs have been of great interest due to their use in targeted drug delivery in cancer treatment. There is always a challenge in AuNP synthesis because of their non-reproducibility at the perfect size and shape, but green macro algae took over this challenge and synthesized stable and reproducible AuNPs [65,125,163].

4. Biomedical Applications of Algae-Mediated NPs

NPs synthesized from various green approaches are usually biocompatible and free from toxic chemicals entangled on their surfaces, because they do not use any external capping or reducing agents during the synthesis of NPs and therefore show less toxicity than chemically synthesized NPs. Algae species also do not involve the use of any toxic chemicals during reduction and stabilization of NPs, as they contain naturally occurring biomolecules which impart less or no toxicity, and thus can be preferably used in various biomedical applications [165,169]. Various applications of algae-mediated NPs, predominantly in biomedicine are discussed herein in detail.

4.1. Antibacterial Activity

The widespread use of antibiotics to treat bacterial infections has led to the emergence of multi-drug-resistant bacterial strains. Providing a safe and efficient treatment for drug-resistant bacterial strains is a major health challenge faced globally. Therefore, there has been a shift towards the use of NPs as an alternative antibacterial agent, which has demonstrated efficient and superior bactericidal activity. Since NPs kill bacteria by disrupting the cell membrane and generating reactive oxygen species (ROS), they have broad-spectrum antibacterial activity against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria [170].

The NPs synthesized from algae have been investigated for their antibacterial activity against a range of bacterial strains. The AgNPs biosynthesized from brown seaweed Padina tetrastromatica efficiently retarded the growth of P. aeuroginosa, Klebsiella planticola, Bacillus subtilis, and other Bacillus sp. [171]. In another study, stable and colloidal-shaped AgNPs prepared from the aqueous extract of green marine algae Caulerpa serrulata exhibited exceptional antimicrobial ability at lower concentrations against Shigella sp., S. aureus, E. coli, P. aeruginosa, and Salmonella typhi. The highest zone of inhibition of 21 mm of AgNPs (75 µl) was recorded against E. coli, whereas the smallest zone of inhibition of 10 mm at 50 μL AgNPs was observed against S. typhi [19]. Similarly, AgNPs synthesized from Pithophora oedogonia aqueous extract have shown potential antibacterial activity against E. coli, Micrococcus luteus, S. aureus, B. subtilis, Vibrio cholerae, P. aeruginosa, and Shigella flexneri. The highest zone of inhibition (17.2 mm) was measured for P. aeruginosa, which shows exceptional antibacterial activity of AgNPs against more resistant gram-negative rods [13].

Furthermore, spherical AuNPs synthesized from the protein extract of blue-green alga S. platensis significantly inhibited the growth of S. aureus and B. subtilis [118]. AuNPs synthesized by from Ecklonia cava and Nitzschia have been tested for their antibacterial activity against E. coli, S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, B. subtilis, Aspergillus fumigatus, C. albicans, and A. niger [52,172]. The AuNPs synthesized from Stoechospermum marginatum displayed superior antibacterial activity against Enterobacter faecalis as compared to tetracycline antibiotic standard [57]. In another study, Neodesmus pupukensis-mediated AgNPs and AuNPs were tested for their antibacterial potential against various strains of bacteria. The results showed that the zones of inhibition of AgNPs were: Pseudomonas sp (43 mm); E. coli (24.5 mm); K. pneumoniae (27 mm); S. marcescens (39 mm), while AuNPs showed activity to only Pseudomonas sp. (27.5 mm) and S. marcescens (28.5 mm) [173]. These findings show the promising application of algae-mediated NPs as antibacterial agents in future.

4.2. Antifungal Activity

Fungal infections are becoming a growing public health concern due to the limited availability of antifungal drugs and emerging resistance to antifungal drugs. There is a strong incentive to develop new, strong, and effective antifungal agents. NPs could be a novel treatment option for fungal infections, as they demonstrate excellent fungicidal activity [174]. AgNPs have been the most effective antifungal agent synthesized by the green approach so far. A study reported the synthesis of AgNPs from Sargassum longifolium which have been examined for their antifungal activities at various concentrations against different pathogenic fungal strains, including A. fumigatus, Fusarium sp., and C. albicans. The results showed that AgNPs significantly inhibited the growth of each fungal strain in a dose-dependent manner [175]. In another study, AgNPs were synthesized using red seaweed Gelidiella acerosa aqueous extract and tested for antifungal activity against Fusarium dimerum, Mucor indicus, Humicola insolens, and Trichoderma reesei. The results indicated considerable antifungal activity of AgNPs as compared to standard antifungal drug [96]. AgNPs biosynthesized from green algae Ulva latica and red algae Hypnea musciformis have been effective in retarding the growth of A. niger, C. albicans, and Candida parapsilosis fungal strains [176].

Algae-synthesized AuNPs have also been investigated for their antifungal activity, however only a few studies have been reported in this regard. AuNPs synthesized by using aqueous extract of brown seaweed Dictyota bartayresiana showed antifungal activity against soft rot fungus F.dimerum and Humicola insolens [177]. Similarly, Neodesmus pupukensis-mediated AgNPs and AuNPs were tested for their antifungal potential. The antifungal potency of AgNPs was confirmed with mycelial inhibition of 80.6%, 57.1%, 79.4%, 65.4%, and 69.8% against A. niger, A. fumigatus, A. flavus, F. solani, and C. albicans, respectively, while AuNPs had 79.4%, 44.3%, 75.4%, 54.9%, and 66.4% against A. niger, A. fumigatus, A. flavus, F. solani, and C. albicans, respectively [173].

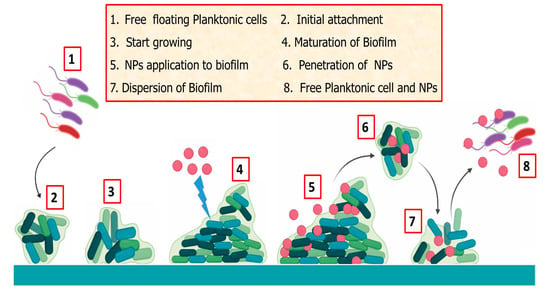

4.3. Antifouling Agent and Biofilm Prevention

Most bacteria exist as biofilms which contain diverse species, such as fungi and algae, that interact with each other and their environment [178]. This undesirable growth on submerged surfaces is regarded as biofouling, which poses significant health risks and financial losses in marine, medical, and industrial fields [179]. Antifouling methods range from biocides to the use of toxic chemicals, however they end up accumulating and polluting the environment. Therefore, NPs have been investigated as alternative antifouling agents, as they can effectively inhibit bacterial adhesion through NP-ligand interaction and biofilm formation on surfaces, as shown in Figure 4 [180]. AgNPs have been reported to significantly prevent biofilm formation against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, including E. coli, Salmonella sp., Aeromonas hydrophila, and S. liquefaciens. Circular AgNPs (2–17 nm) proved lethal to A. salina brine shrimp, having an LC50 of 88.94 μLmL−1 [35]. Likewise, AgNPs synthesized from S. ilicifolium (33–40 nm) exhibited cytotoxicity against A. salina [181]. In another study, phytagel and apcomin zinc chrome paint coated with T. ornate-synthesized AgNPs inhibited the growth of macroflora as well as microflora. The AgNPs limited biofilm formation, with over 71.9% inhibition in E. coli and 40% inhibition in Micrococcus specie. AgNPs can also serve as antifouling agents selective towards target species; e.g., AgNPs showed a 100% mortality rate for Balanu samphitrite larvae hatchlings, while 56.6% for A. marina [74].

Figure 4.

Graphical representation of the antifouling activity of the algae-mediated NPs.

In addition to AgNPs, CuNPs have also been used as anti-biofilm agents against some clinical P. aeruginosa isolates; results showed that CuNPs not only prevented biofilm formation but also diminished hydrophobicity of cell surfaces and extracellular polymeric substances of P. aeruginosa [180]. In a recent study, S. myriocystum-mediated AgNPs of different concentrations (10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 µg/mL) were tested against biofilm-producing bacterial strains S. epidermidis and P. aeruginosa; the maximum percent of biofilm inhibition (67.75%) was obtained at 50 µg/mL conc., whereas 48.34% was obtained in 50 µg/mL AgNPs treated with S. epidermidis. Besides P. aureginosa, the inhibition of biofilm formation rate recorded was 55.49% for AgNPs at higher concentration (50 µg/mL) [182]. These findings suggest that the algal-mediated NPs can be replaceable formulations of antifouling agents in the near future and biofilm inhibition of NPs at minimum inhibitory concentrations was linked to their inhibitory effect on gene expressions connected to motility and biofilm formation [183].

4.4. Anti-Cancerous Activity

One of the most active areas of nano-biotechnology research includes the use of NPs for cancer therapy and for targeted delivery of anti-cancerous drugs [184]. Various studies have been published in the recent era on anti-cancerous activities of algae-mediated NPs. In a study, Sargassum vulgare-synthesized AgNPs (10 nm) exhibited significant anti-cancerous activity against HeLa cells and human myeloblastic leukemic cells HL60 [180]. Silver nano-triangles coated with algal-derived chitosan polymers (Chit-AgNPs) served as photothermal agents against non-small human lung cancer cell line (NCI-H460) [185]. Moreover, S. muticum-mediated AgNPs have shown in-vitro cytotoxic effects against MCF7 breast cancer cell line. Varying concentrations of AgNPs from 3 µg/mL to 50 µg/mL were treated with MCF7 cell line for about 48 h and the highest viability rate of 100.36% was observed at 12.5 µg/mL concentration. These AgNPs have induced ROS intracellularly, which results in the apoptosis and eventually death of cancer cells [186]. In another study, S. myriocystum-synthesized AgNPs were assessed for their cytotoxic abilities against the HeLa cell line by being used in various concentrations ranging from 0, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, to 512 µg/mL via MTT assay. Results showed that the AgNP-treated HeLa cell line showed 50% inhibitory and apoptotic activities and overall cytotoxic abilities increased with an increase in concentration of AgNPs in the medium [182]. Similarly, in vitro cytotoxicity potential of algal-mediated AgNPs against breast cancer MCF-7 cell line was observed by using various concentrations (0–100 µg/mL) for time intervals of 24, 36, and 48 h. The maximum inhibitory concentration value of AgNPs was recorded 20 µg/mL against breast cancer cells which have shown nuclear fragmentation, apoptosis, and cell death, confirming the anticancerous potential of AgNPs [187].

Algae-mediated AuNPs have also been reported to show strong anti-cancerous activities against various cell lines. In one study, Acanthophora spicifera-mediated AuNPs exhibited strong anti-cancerous activities against the colorectal adenocarcinoma HT-29 cell line. AuNPs were added in concentrations of 1.88, 3.75, 7.5, 15, and 30 µg/mL and incubated for about 24 h and observed via MTT assay. The maximum inhibitory concentration of 21.86 µg/mL was reported, which led to apoptosis, lack of morphological structure, and cell shrinkage in cancer cell lines [188]. Another study reported marine algae Chaetomorpha linum-mediated AuNPs, which showed in-vitro anti-cancerous potential against HCT-116 colon cancer cell line. Dose-dependent cytotoxic effects of AuNPs were reported in colon cancer cell lines after incubation with these nanoparticles. A series of apoptotic inductions were observed which triggered the activation of apoptotic caspase 3 and 9 along with reduction in anti-apoptotic proteins like Bcl-xl and Bcl-2, which veritably confirmed that the algal-synthesized AuNPs are efficient anti-cancerous agents [189]. Similarly, AuNPs coated with polyethylene glycol can kill maximum tumor cells as compared to an anticancer cytokine tumor necrosis factor-alpha [8,190]. These studies depict the anti-cancerous potential of algal-derived NPs.

4.5. Nano-Bioremediation

The use of NPs as an innovative method to remediate contaminated sites has received great attention recently. Algal-synthesized NPs have been tested as bioremediation agents; for example, U. lactuca-synthesized AgNPs photo-catalyzed the breakdown of methyl orange dye when illuminated with visible light. Further, it was observed that a low dosage of U. lactuca-mediated AgNPs greatly reduced the population of Plasmodium falciparum, which is otherwise a chloroquine-resistant species [89]. In a comparative study, the AgNPs synthesized from Microchaete showed great de-colorization ability against methyl red azo dyes as compared to cyanobacterial extract [131]. Another study showed the catalytic activity of AuNPs synthesized from the aqueous extract of brown algae S. tenerrimum and T. conoides against the organic dyes sulforhodamine, rhodamine B, and aromatic nitro compounds [60]. Similarly, the S. myriocystum-mediated AgNPs exhibited potential photocatalytic activity against methylene blue. The maximum percentage of MB degradation was observed at 98% within 60 min [182]. In a recent study, the Chlorella ellipsoidea-mediated biomatrix-loaded AgNPs exhibited high photocatalytic activity for the degradation of the hazardous pollutant dyes methylene blue and methyl orange. The catalytic efficiency was sustained even after three reduction cycles [191]. In one study, the green alga Scenedesmus obliquus was used to synthesize lipid-cadmium sulfide NPs. During synthesis, it was observed that the adsorption kinetics of Cd2+ ions was significantly increased and chemisorbed monolayer (Cd2+) irreversibly attached to the biomass of alga. Thus, Scenedesmus proved to be efficient model alga for the bioremediation of Cd2+ ions due to its high retention capability [192]. In this way, various algae-mediated mediated NPs are playing their positive role in remediating various kinds of heavy metals, organic/aromatic compounds, and numerous types of dyes.

4.6. Biosensing

Algal-synthesized AuNPs have shown great optical properties which can be utilized in biosensing applications, such as sensing the type and level of hormones in human body, particularly useful in cancer diagnostics. The algal-synthesized nano Au-Ag alloy demonstrated significant electro-catalytic ability against 2-butanone under room temperature, acting as a platform for developing an early-stage cancer detecting biosensor which can easily sense the presence of malignant cells at very initial stages [193]. In a recent report, Noctiluca scintillans-mediated AgNPs were evaluated for colorimetric sensing of hydrogen peroxide, which is used as an antiseptic and is indicated for small dermal scratches; in mouth, gum, teeth pain, or whitening and oral discharge. Results showed that the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide on AgNPs’ catalytic surface was found to be pH-, temperature-, and time-dependent. The test showed also a color change from brown to colorless, with hydrogen peroxide presenting the most noticeable change in color [194]. In another study, The biosynthesized AuNPs by Hypnea valencia also showed the ability to detect human chorionic gonadotrophin (HCG) hormone in urine samples of pregnant women during HCG blood pregnancy test [195]. Furthermore, Platinum NPs (PtNPs) synthesized from S. myriocystum serve as biosensors for detecting the adrenaline level in the body, which is a hormone-based drug used to treat heart attacks, asthma, and allergies [196].

5. Limitations and Future Prospects

There is no doubt that algae serve as excellent candidates for the green synthesis of NPs, as they are rich sources of secondary metabolites, which act as reducing and capping agents. However, this field is still in its infancy and could not be scaled up for commercial uses. This could be due to several limitations of algal-mediated biosynthesis of NPs, such as slow kinetics of reactions (taking a few days to weeks), low yield of NPs, poor morphological characteristic of biosynthesized NPs, choice of algal strain, and lack of optimization of synthesis conditions, such as pH, temperature, contact time, and concentration. Besides these, the yield of NPs is also variable, and the process control is an issue to be addressed. Moreover, colloidal stability is also often an issue that needs serious attention, because in certain cases a high level of agglomeration has been reported. A little knowledge regarding synthesis mechanism has also limited the use of alga in NP production. Therefore, to build large-scale photo-bioreactors, further research is needed to address the issues of kinetics, yield, and cell viability, along with a comparative study on the physiochemical properties of NPs synthesized by conventional methods and using algae is also a big knowledge gap that should be filled by the scientific community. Moreover, a significant amount of research is needed to identify and establish the role of specific biomolecules responsible for the reduction and capping of NPs during the algae-mediated biosynthesis process. In addition to this, only a limited number and types of NPs have been synthesized from algae, there are still other NPs like zinc oxide, palladium, silicon, and carbon-based NPs whose synthesis could be explored in the future. With new emerging characterization technologies, controlled and comparative synthesis of algal-based NPs could be done, which will help in refining the qualities of algal-mediated NPs for their industrial applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A., B.H.A. and C.H.; methodology, R.C., K.N., and A.K.K.; software, S.A. and C.H.; validation, B.H.A., A.K.K. and C.H.; formal analysis, S.A., R.C. and C.H.; investigation, R.C., K.N., A.K.K., C.H., B.H.A. and S.A.; resources, S.A. and C.H.; data curation, S.A., and K.N.; writing—original draft preparation, R.C., K.N. and A.K.K.; writing—review and editing, S.A., C.H. and A.K.K.; visualization, R.C., K.N., A.K.K., C.H. and B.H.A.; supervision, S.A. and C.H.; project administration, S.A.; funding acquisition, C.H., S.A. and B.H.A.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no funding.

Acknowledgments

S.A. acknowledges the administration of Kinnaird College for Women, Lahore for providing support. B.H.A. and C.H. acknowledge Le Studium-Institute for Advanced Studies, Loire Valley, Orléans, France.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Tran, P.H.-L.; Tran, T.T.-D.; Van Vo, T.; Lee, B.-J. Promising iron oxide-based magnetic nanoparticles in biomedical engineering. Arch. Pharmacal. Res. 2012, 35, 2045–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, E.J.; Holback, H.; Liu, K.C.; Abouelmagd, S.A.; Park, J.; Yeo, Y. Nanoparticle characterization: State of the art, challenges, and emerging technologies. Mol. Pharm. 2013, 10, 2093–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, S.; Harini, B.; Rakshith, D.; Satish, S. Marine microbes: Invisible nanofactories. J. Pharm. Res. 2013, 6, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amato, R.; Falconieri, M.; Gagliardi, S.; Popovici, E.; Serra, E.; Terranova, G.; Borsella, E. Synthesis of ceramic nanoparticles by laser pyrolysis: From research to applications. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2013, 104, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zharov, V.P.; Kim, J.-W.; Curiel, D.T.; Everts, M. Self-assembling nanoclusters in living systems: Application for integrated photothermal nanodiagnostics and nanotherapy. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2005, 1, 326–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Wang, E. Noble metal nanomaterials: Controllable synthesis and application in fuel cells and analytical sensors. Nano Today 2011, 6, 240–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.G.; Gokavarapu, S.D.; Rajeswari, A.; Dhas, T.S.; Karthick, V.; Kapadia, Z.; Shrestha, T.; Barathy, I.; Roy, A.; Sinha, S. Facile green synthesis of gold nanoparticles using leaf extract of antidiabetic potent Cassia auriculata. Colloids Surf. B. Biointerfaces 2011, 87, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Gao, T.; Hong, H.; Sun, J. Applications of gold nanoparticles in cancer nanotechnology. Nanotechnol. Sci. Appl. 2008, 1, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, G.S.; Brar, S.K.; Kaur, S.; Verma, M. Green approach for nanoparticle biosynthesis by fungi: Current trends and applications. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2012, 32, 49–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Zhang, W.; Hu, L.; Ding, W.; Wu, F.; Li, J. Etching synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles for adsorption of arsenic from water. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 15900–15910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, S.; Ahmad, M.B.; Namvar, F.; Mohamad, R. Green biosynthesis and characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles using brown marine macroalga Sargassum muticum aqueous extract. Mater. Lett. 2014, 116, 275–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaiarasi, R.; Jayallakshmi, N.; Venkatachalam, P. Phytosynthesis of nanoparticles and its applications. Plant Cell Biotechnol. Mol. Biol. 2010, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha, S.N.; Paul, D.; Halder, N.; Sengupta, D.; Patra, S.K. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using fresh water green alga Pithophora oedogonia (Mont.) Wittrock and evaluation of their antibacterial activity. Appl. Nanosci. 2015, 5, 703–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iravani, S. Green synthesis of metal nanoparticles using plants. Green Chem. 2011, 13, 2638–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, Z.S.; Kamat, P.V. What factors control the size and shape of silver nanoparticles in the citrate ion reduction method? J. Phys. Chem. B 2004, 108, 945–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahoumane, S.A.; Djediat, C.; Yéprémian, C.; Couté, A.; Fiévet, F.; Coradin, T.; Brayner, R. Species selection for the design of gold nanobioreactor by photosynthetic organisms. J. Nanopart. Res. 2012, 14, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahoumane, S.A.; Wijesekera, K.; Filipe, C.D.; Brennan, J.D. Stoichiometrically controlled production of bimetallic gold-silver alloy colloids using micro-alga cultures. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2014, 416, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parial, D.; Pal, R. Biosynthesis of monodisperse gold nanoparticles by green alga Rhizoclonium and associated biochemical changes. J. Appl. Phycol. 2015, 27, 975–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboelfetoh, E.F.; El-Shenody, R.A.; Ghobara, M.M. Eco-friendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles using green algae (Caulerpa serrulata): Reaction optimization, catalytic and antibacterial activities. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2017, 189, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulkoti, N.I.; Taranath, T. Biosynthesis of nanoparticles using microbes—A review. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2014, 121, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahdar, A. Study of different capping agents effect on the structural and optical properties of Mn doped ZnS nanostructures. World Appl. Program 2013, 3, 56–60. [Google Scholar]

- Menon, S.; Rajeshkumar, S.; Kumar, V. A review on biogenic synthesis of gold nanoparticles, characterization, and its applications. Resour. Effic. Technol. 2017, 3, 516–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.; Fawcett, D.; Sharma, S.; Tripathy, S.K.; Poinern, G.E.J. Green synthesis of metallic nanoparticles via biological entities. Materials 2015, 8, 7278–7308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakibaie, M.; Forootanfar, H.; Mollazadeh-Moghaddam, K.; Bagherzadeh, Z.; Nafissi-Varcheh, N.; Shahverdi, A.R.; Faramarzi, M.A. Green synthesis of gold nanoparticles by the marine microalga Tetraselmis suecica. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2010, 57, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, V.; Berthold, D.; Puranik, P.; Gantar, M. Screening of cyanobacteria and microalgae for their ability to synthesize silver nanoparticles with antibacterial activity. Biotechnol. Rep. 2015, 5, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandran, P.R.; Naseer, M.; Udupa, N.; Sandhyarani, N. Size controlled synthesis of biocompatible gold nanoparticles and their activity in the oxidation of NADH. Nanotechnology 2011, 23, 015602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fawcett, D.; Verduin, J.J.; Shah, M.; Sharma, S.B.; Poinern, G.E.J. A review of current research into the biogenic synthesis of metal and metal oxide nanoparticles via marine algae and seagrasses. J. Nanosci. 2017, 2017, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, P.C.; Kausar, F.; Lee, J.H.; Han, J.I. Facile fabrication of silver nanoparticle embedded CaCO3 microspheres via microalgae-templated CO2 biomineralization: Application in antimicrobial paint development. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 32562–32569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnihotri, S.; Mukherji, S.; Mukherji, S. Size-controlled silver nanoparticles synthesized over the range 5–100 nm using the same protocol and their antibacterial efficacy. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 3974–3983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, R.; Pandey, R.; Barman, I. Engineering tailored nanoparticles with microbes: Quo vadis? Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2016, 8, 316–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Sharma, S.; Sharma, K.; Chetri, S.P.; Vashishtha, A.; Singh, P.; Kumar, R.; Rathi, B.; Agrawal, V. Algae as crucial organisms in advancing nanotechnology: A systematic review. J. Appl. Phycol. 2016, 28, 1759–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahoumane, S.A.; Yéprémian, C.; Djédiat, C.; Couté, A.; Fiévet, F.; Coradin, T.; Brayner, R. A global approach of the mechanism involved in the biosynthesis of gold colloids using micro-algae. J. Nanopart. Res. 2014, 16, 2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicard, C.; Brayner, R.; Margueritat, J.; Hémadi, M.; Couté, A.; Yéprémian, C.; Djediat, C.; Aubard, J.; Fiévet, F.; Livage, J. Nano-gold biosynthesis by silica-encapsulated micro-algae: A “living” bio-hybrid material. J. Mater. Chem. 2010, 20, 9342–9347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senapati, S.; Syed, A.; Moeez, S.; Kumar, A.; Ahmad, A. Intracellular synthesis of gold nanoparticles using alga Tetraselmis kochinensis. Mater. Lett. 2012, 79, 116–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayan, S.R.; Santhiyagu, P.; Singamuthu, M.; Kumari Ahila, N.; Jayaraman, R.; Ethiraj, K. Synthesis and characterization of silver and gold nanoparticles using aqueous extract of seaweed, Turbinaria conoides, and their antimicrofouling activity. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 938272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahoumane, S.A.; Wujcik, E.K.; Jeffryes, C. Noble metal, oxide and chalcogenide-based nanomaterials from scalable phototrophic culture systems. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2016, 95, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oza, G.; Pandey, S.; Mewada, A.; Kalita, G.; Sharon, M.; Phata, J.; Ambernath, W.; Sharon, M. Facile biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles exploiting optimum pH and temperature of fresh water algae Chlorella pyrenoidusa. Adv. Appl. Sci. Res. 2012, 3, 1405–1412. [Google Scholar]

- Parial, D.; Patra, H.K.; Roychoudhury, P.; Dasgupta, A.K.; Pal, R. Gold nanorod production by cyanobacteria—A green chemistry approach. J. Appl. Phycol. 2012, 24, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namvar, F.; Azizi, S.; Ahmad, M.B.; Shameli, K.; Mohamad, R.; Mahdavi, M.; Tahir, P.M. Green synthesis and characterization of gold nanoparticles using the marine macroalgae Sargassum muticum. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2015, 41, 5723–5730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalabegishvili, T.L.; Kirkesali, E.I.; Rcheulishvili, A.N.; Ginturi, E.N.; Murusidze, I.G.; Pataraya, D.T.; Gurielidze, M.A.; Tsertsvadze, G.I.; Gabunia, V.N.; Lomidze, L.G. Synthesis of gold nanoparticles by some strains of Arthrobacter genera. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2012, 2, 164–173. [Google Scholar]

- Sahayaraj, K.; Rajesh, S.; Rathi, J. Silver nanoparticles biosynthesis using marine alga Padina pavonica (linn.) and its microbicidal activity. Dig. J. Nanomater. Bios. 2012, 7, 1557–1567. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad, T.N.; Kambala, V.S.R.; Naidu, R. Phyconanotechnology: Synthesis of silver nanoparticles using brown marine algae Cystophora moniliformis and their characterisation. J. Appl. Phycol. 2013, 25, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.S.; Kumar, Y.; Khan, M.; Anbu, J.; De Clercq, E. Antihistaminic and antiviral activities of steroids of Turbinaria conoides. Nat. Prod. Res. 2011, 25, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeshkumar, S.; Kannan, C.; Annadurai, G. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using marine brown algae Turbinaria conoides and its antibacterial activity. Int. J. Pharma. Bio Sci. 2012, 3, 502–510. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Xie, J.; Lee, J.; Ting, Y.; Chen, J.P. Optimization of high-yield biological synthesis of single-crystalline gold nanoplates. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 15256–15263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mata, Y.; Torres, E.; Blazquez, M.; Ballester, A.; González, F.; Munoz, J. Gold (III) biosorption and bioreduction with the brown alga Fucus vesiculosus. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 166, 612–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, P.; Kaur, A.; Goyal, D. Algae-based metallic nanoparticles: Synthesis, characterization and applications. J. Microbiol. Methods 2019, 163, 105656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M.M.; Ismail, E.H.; El-Baghdady, K.Z.; Mohamed, D. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using olive leaf extract and its antibacterial activity. Arab. J. Chem. 2014, 7, 1131–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhiyazhagan, P.; Murugan, K.; Kumar, A.N.; Nataraj, T.; Dinesh, D.; Panneerselvam, C.; Subramaniam, J.; Kumar, P.M.; Suresh, U.; Roni, M. Sargassum muticum-synthesized silver nanoparticles: An effective control tool against mosquito vectors and bacterial pathogens. Parasitol. Res. 2015, 114, 4305–4317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghodake, G.; Lee, D.S. Biological synthesis of gold nanoparticles using the aqueous extract of the brown algae Laminaria japonica. J. Nanoelectron. Optoelectron. 2011, 6, 268–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeshkumar, S.; Malarkodi, C.; Gnanajobitha, G.; Paulkumar, K.; Vanaja, M.; Kannan, C.; Annadurai, G. Seaweed-mediated synthesis of gold nanoparticles using Turbinaria conoides and its characterization. J. Nanostructure Chem. 2013, 3, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, J.; Manivasagan, P.; Kim, S.-K.; Kirthi, A.V.; Marimuthu, S.; Rahuman, A.A. Marine algae-mediated synthesis of gold nanoparticles using a novel Ecklonia cava. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2014, 37, 1591–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahoumane, S.A.; Mechouet, M.; Wijesekera, K.; Filipe, C.D.; Sicard, C.; Bazylinski, D.A.; Jeffryes, C. Algae-mediated biosynthesis of inorganic nanomaterials as a promising route in nanobiotechnology—A review. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 552–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singaravelu, G.; Arockiamary, J.; Kumar, V.G.; Govindaraju, K. A novel extracellular synthesis of monodisperse gold nanoparticles using marine alga, Sargassum wightii Greville. Colloids Surf. B. Biointerfaces 2007, 57, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Ballesteros, N.; Rodríguez-Argüelles, M.; Lastra-Valdor, M.; González-Mediero, G.; Rey-Cao, S.; Grimaldi, M.; Cavazza, A.; Bigi, F. Synthesis of silver and gold nanoparticles by Sargassum muticum biomolecules and evaluation of their antioxidant activity and antibacterial properties. J. Nanostructure Chem. 2020, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhas, T.S.; Kumar, V.G.; Abraham, L.S.; Karthick, V.; Govindaraju, K. Sargassum myriocystum mediated biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles. Spectrochim. Acta. A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2012, 99, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajathi, F.A.A.; Parthiban, C.; Kumar, V.G.; Anantharaman, P. Biosynthesis of antibacterial gold nanoparticles using brown alga, Stoechospermum marginatum (kützing). Spectrochim. Acta. A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2012, 99, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Kalaivani, R.; Manikandan, S.; Sangeetha, N.; Kumaraguru, A. Facile green synthesis of variable metallic gold nanoparticle using Padina gymnospora, a brown marine macroalga. Appl. Nanosci. 2013, 3, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varun, S.; Sudha, S. P Senthil Kumar. Biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles from aqueous extract of Dictyota bartayresiana and their anti-fungal activity. Indian J. Adv. Chem. Sci. 2014, 2, 190–193. [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishna, M.; Babu, D.R.; Gengan, R.M.; Chandra, S.; Rao, G.N. Green synthesis of gold nanoparticles using marine algae and evaluation of their catalytic activity. J. Nanostructure Chem. 2016, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Ballesteros, N.; Prado-López, S.; Rodríguez-González, J.; Lastra, M.; Rodríguez-Argüelles, M. Green synthesis of gold nanoparticles using brown algae Cystoseira baccata: Its activity in colon cancer cells. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2017, 153, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govindaraju, K.; Basha, S.K.; Kumar, V.G.; Singaravelu, G. Silver, gold and bimetallic nanoparticles production using single-cell protein (Spirulina platensis) Geitler. J. Mater. Sci. 2008, 43, 5115–5122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. Green Energy for Sustainability and Energy Security; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Thangaraju, N.; Venkatalakshmi, R.; Chinnasamy, A.; Kannaiyan, P. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles and the antibacterial and anticancer activities of the crude extract of Sargassum polycystum C. Agardh. Nano Biomed. Eng. 2012, 4, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanalakshmi, P.; Azeez, R.; Rekha, R.; Poonkodi, S.; Nallamuthu, T. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles using green and brown seaweeds. Phykos 2012, 42, 39–45. [Google Scholar]

- Bhuyar, P.; Rahim, M.H.A.; Sundararaju, S.; Ramaraj, R.; Maniam, G.P.; Govindan, N. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles using marine macroalgae Padina sp. and its antibacterial activity towards pathogenic bacteria. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2020, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiny, P.; Mukherjee, A.; Chandrasekaran, N. Marine algae mediated synthesis of the silver nanoparticles and its antibacterial efficiency. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 5, 239–241. [Google Scholar]

- El-Rafie, H.; El-Rafie, M.; Zahran, M. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using polysaccharides extracted from marine macro algae. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 96, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohandass, C.; Vijayaraj, A.; Rajasabapathy, R.; Satheeshbabu, S.; Rao, S.; Shiva, C.; De-Mello, I. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles from marine seaweed Sargassum cinereum and their antibacterial activity. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 75, 606. [Google Scholar]

- Devi, J.S.; Bhimba, B.V.; Peter, D.M. Production of biogenic silver nanoparticles using Sargassum longifolium and its applications. Indian J. Geomarine Sci. 2013, 42, 125–130. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad, T.; Elumalai, E. Marine algae mediated synthesis of silver nanopaticles using Scaberia agardhü Greville. J. Biol. Sci. 2013, 13, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asha, K.; Johnson, M.; Chandra, P.; Shibila, T.; Revathy, I. Extracellular synthesis of silver nanoparticles from a marine Alga, Sargassum polycystum C. agardh and their biopotentials. WJPPS 2015, 4, 1388–1400. [Google Scholar]

- Govindaraju, K.; Krishnamoorthy, K.; Alsagaby, S.A.; Singaravelu, G.; Premanathan, M. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles for selective toxicity towards cancer cells. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2015, 9, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, M.; Sivanandham, V.; Hans-Uwe, D.; Murugaiah, S.G.; Seeni, P.; Gopalan, S.; Rathinam, A.J. Antifouling assessments on biogenic nanoparticles: A field study from polluted offshore platform. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 101, 816–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdavi, M.; Namvar, F.; Ahmad, M.B.; Mohamad, R. Green biosynthesis and characterization of magnetic iron oxide (Fe3O4) nanoparticles using seaweed (Sargassum muticum) aqueous extract. Molecules 2013, 18, 5954–5964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanpuria, P.; Rana, N.K.; Yadav, S.K. Biosynthesis of nanoparticles: Technological concepts and future applications. J. Nanopart. Res. 2008, 10, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidyanathan, R.; Kalishwaralal, K.; Gopalram, S.; Gurunathan, S. Nanosilver—The burgeoning therapeutic molecule and its green synthesis (Retraction of vol 27, pg 924, 2009). Biotechnol. Adv. 2010, 28, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maneerung, T.; Tokura, S.; Rujiravanit, R. Impregnation of silver nanoparticles into bacterial cellulose for antimicrobial wound dressing. Carbohydr. Polym. 2008, 72, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar-Krishnan, S.; Prokhorov, E.; Hernández-Iturriaga, M.; Mota-Morales, J.D.; Vázquez-Lepe, M.; Kovalenko, Y.; Sanchez, I.C.; Luna-Bárcenas, G. Chitosan/silver nanocomposites: Synergistic antibacterial action of silver nanoparticles and silver ions. Eur. Polym. J. 2015, 67, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushnerova, N.; Fomenko, S.; Sprygin, V.; Kushnerova, T.; Khotimchenko, Y.S.; Kondrat’eva, E.; Drugova, L. An extract from the brown alga Laminaria japonica: A promising stress-protective preparation. Russ. J. Mar. Biol. 2010, 36, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodashenas, B.; Ghorbani, H.R. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles with different shapes. Arab. J. Chem. 2019, 12, 1823–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirelkhatim, A.; Mahmud, S.; Seeni, A.; Kaus, N.H.M.; Ann, L.C.; Bakhori, S.K.M.; Hasan, H.; Mohamad, D. Review on zinc oxide nanoparticles: Antibacterial activity and toxicity mechanism. Nanomicro Lett. 2015, 7, 219–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, S.; Mahdavi Shahri, M.; Mohamad, R. Green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles for enhanced adsorption of lead ions from aqueous solutions: Equilibrium, kinetic and thermodynamic studies. Molecules 2017, 22, 831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, H.S.; Müller, K.M.; Sheath, R.G.; Ott, F.D.; Bhattacharya, D. Defining the major lineages of red algae (Rhodophyta) 1. J. Phycol. 2006, 42, 482–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakritinan, C.; Shankar, S.; Anand, M.; Kumaraguru, A. Biosynthesis of silver, gold and bimetallic alloy (Ag: Au) Nanoparticles from green alga, Lyngpya sp. In Proceedings of the 3rd National Conference on Nanaomaterials and Nanotechnology, Lucknow, India, 21–23 December 2020; pp. 174–187. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, P.S.; Mantri, V.A.; Ganesan, K. Mineral composition of edible seaweed Porphyra vietnamensis. Food Chem. 2007, 102, 215–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatpurwar, V.; Pokharkar, V. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using marine polysaccharide: Study of in-vitro antibacterial activity. Mater. Lett. 2011, 65, 999–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugazhendhi, A.; Prabakar, D.; Jacob, J.M.; Karuppusamy, I.; Saratale, R.G. Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Gelidium amansii and its antimicrobial property against various pathogenic bacteria. Microb. Pathog. 2018, 114, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Govindaraju, M.; Senthamilselvi, S.; Premkumar, K. Photocatalytic degradation of methyl orange dye using silver (Ag) nanoparticles synthesized from Ulva lactuca. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2013, 103, 658–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajasulochana, P.; Krishnamoorthy, P.; Dhamotharan, R. Potential application of Kappaphycus alvarezii in agricultural and pharmaceutical industry. J. Chem. Pharm. Res. 2012, 4, 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Raouf, N.; Al-Enazi, N.M.; Ibraheem, I.B. Green biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles using Galaxaura elongata and characterization of their antibacterial activity. Arab. J. Chem. 2017, 10, S3029–S3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, L.; Blázquez, M.L.; Muñoz, J.A.; González, F.; Ballester, A. Biological synthesis of metallic nanoparticles using algae. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2013, 7, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.; Purkayastha, D.D.; Hazra, S.; Thajamanbi, M.; Bhattacharjee, C.R.; Ghosh, N.N.; Rout, J. Biosynthesis of fluorescent gold nanoparticles using an edible freshwater red alga, Lemanea fluviatilis (L.) C. Ag. and antioxidant activity of biomatrix loaded nanoparticles. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2014, 37, 2559–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naveena, B.E.; Prakash, S. Biological synthesis of gold nanoparticles using marine algae Gracilaria corticata and its application as a potent antimicrobial and antioxidant agent. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2013, 6, 179–182. [Google Scholar]

- El-Kassas, H.Y.; El-Sheekh, M.M. Cytotoxic activity of biosynthesized gold nanoparticles with an extract of the red seaweed Corallina officinalis on the MCF-7 human breast cancer cell line. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2014, 15, 4311–4317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vivek, M.; Kumar, P.S.; Steffi, S.; Sudha, S. Biogenic silver nanoparticles by Gelidiella acerosa extract and their antifungal effects. Avicenna J. Med. Biotechnol. 2011, 3, 143. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kumar, P.; Senthamilselvi, S.; Lakshmipraba, A.; Premkumar, K.; Muthukumaran, R.; Visvanathan, P.; Ganeshkumar, R.; Govindaraju, M. Efficacy of bio-synthesized silver nanoparticles using Acanthophora spicifera to encumber biofilm formation. Dig. J. Nanomater. Biostructures 2012, 7, 511–522. [Google Scholar]

- Shukla, M.K.; Singh, R.P.; Reddy, C.; Jha, B. Synthesis and characterization of agar-based silver nanoparticles and nanocomposite film with antibacterial applications. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 107, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devi, J.S.; Bhimba, B.V.; Ratnam, K. In vitro anticancer activity of silver nanoparticles synthesized using the extract of Gelidiella sp. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 4, 710–715. [Google Scholar]

- Baskar, B.B. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using Kappa phycus species. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 2013, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P.; Selvi, S.S.; Govindaraju, M. Seaweed-mediated biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using Gracilaria corticata for its antifungal activity against Candida spp. Appl. Nanosci. 2013, 3, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, V.; Aruna Devi, J.; Astalakshmi, A.; Nima, P.; Thangaraja, A. Eco-friendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles using a sea weed, Kappaphycus alvarezii (Doty) Doty ex PC Silva. Int. J. Eng. Adv. Technol. 2013, 2, 559–563. [Google Scholar]

- de Aragao, A.P.; de Oliveira, T.M.; Quelemes, P.V.; Perfeito, M.L.G.; Araujo, M.C.; Santiago, J.d.A.S.; Cardoso, V.S.; Quaresma, P.; de Almeida, J.R.d.S.; da Silva, D.A. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using the seaweed Gracilaria birdiae and their antibacterial activity. Arab. J. Chem. 2019, 12, 4182–4188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibraheem, I.; Abd-Elaziz, B.; Saad, W.; Fathy, W. Green biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using marine Red Algae Acanthophora specifera and its antimicrobial activity. J. Nanomed Nanotechnol. 2016, 7, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Sajidha Parveen, K.; Lakshmi, D. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using red algae, Amphiroa fragilissima and its antibacterial potential against gram positive and gram negative bacteria. Int. J. Curr. Sci. 2016, 19, 93–100. [Google Scholar]

- González-Ballesteros, N.; González-Rodríguez, J.; Rodríguez-Argüelles, M.; Lastra, M. New application of two Antarctic macroalgae Palmaria decipiens and Desmarestia menziesii in the synthesis of gold and silver nanoparticles. Polar Sci. 2018, 15, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Naamani, L.; Dobretsov, S.; Dutta, J.; Burgess, J.G. Chitosan-zinc oxide nanocomposite coatings for the prevention of marine biofouling. Chemosphere 2017, 168, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Senthamil Selvi, S.; Lakshmi Prabha, A.; Prem Kumar, K.; Ganeshkumar, R.; Govindaraju, M. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Sargassum tenerrimum and screening phytochemicals for its antibacterial activity. Nano Biomed. Eng. 2012, 4, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadlapudi, V.; Amanchy, R. Synthesis, characterization and antibacterial activity of Silver Nanoparticles from Red Algae, Hypnea musciformis. Adv. Biol. Res. 2017, 11, 242–249. [Google Scholar]

- Nabikhan, A.; Kandasamy, K.; Raj, A.; Alikunhi, N.M. Synthesis of antimicrobial silver nanoparticles by callus and leaf extracts from saltmarsh plant, Sesuvium portulacastrum L. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2010, 79, 488–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvam, G.G.; Sivakumar, K. Phycosynthesis of silver nanoparticles and photocatalytic degradation of methyl orange dye using silver (Ag) nanoparticles synthesized from Hypnea musciformis (Wulfen) JV Lamouroux. Appl. Nanosci. 2015, 5, 617–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, C.R.; Kathiresan, K.; Anandhan, S. A review on marine based nanoparticles and their potential applications. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2015, 14, 1525–1532. [Google Scholar]

- Murugesan, S.; Bhuvaneswari, S.; Sivamurugan, V. Green synthesis, characterization of silver nanoparticles of a marine red alga Spyridia fusiformis and their antibacterial activity. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 9, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosulishvili, L.; Belokobylsky, A.; Kirkesali, E.; Frontasyeva, M.; Pavlov, S.; Aksenova, N. Neutron activation analysis for studying Cr uptake in the blue-green microalga Spirulina platensis. J. Neutron Res. 2007, 15, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.U.; Khan, M.; Malik, N.; Cho, M.H.; Khan, M.M. Recent progress of algae and blue–green algae-assisted synthesis of gold nanoparticles for various applications. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2019, 42, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parial, D.; Gopal, P.K.; Paul, S.; Pal, R. Gold (III) bioreduction by cyanobacteria with special reference to in vitro biosafety assay of gold nanoparticles. J. Appl. Phycol. 2016, 28, 3395–3406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sheekh, M.M.; Shabaan, M.T.; Hassan, L.; Morsi, H.H. Antiviral activity of algae biosynthesized silver and gold nanoparticles against Herps Simplex (HSV-1) virus in vitro using cell-line culture technique. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2020, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suganya, K.U.; Govindaraju, K.; Kumar, V.G.; Dhas, T.S.; Karthick, V.; Singaravelu, G.; Elanchezhiyan, M. Blue green alga mediated synthesis of gold nanoparticles and its antibacterial efficacy against Gram positive organisms. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2015, 47, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lengke, M.F.; Fleet, M.E.; Southam, G. Morphology of gold nanoparticles synthesized by filamentous cyanobacteria from gold (I)− thiosulfate and gold (III)− chloride complexes. Langmuir 2006, 22, 2780–2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Focsan, M.; Ardelean, I.I.; Craciun, C.; Astilean, S. Interplay between gold nanoparticle biosynthesis and metabolic activity of cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. Nanotechnology 2011, 22, 485101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, N.; Banerjee, A.; Lahiri, S.; Panda, A.; Ghosh, A.N.; Pal, R. Biorecovery of gold using cyanobacteria and an eukaryotic alga with special reference to nanogold formation—A novel phenomenon. J. Appl. Phycol. 2009, 21, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parial, D.; Patra, H.K.; Dasgupta, A.K.; Pal, R. Screening of different algae for green synthesis of gold nanoparticles. Eur. J. Phycol. 2012, 47, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MubarakAli, D.; Gopinath, V.; Rameshbabu, N.; Thajuddin, N. Synthesis and characterization of CdS nanoparticles using C-phycoerythrin from the marine cyanobacteria. Mater. Lett. 2012, 74, 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosulishvili, L.; Kirkesali, E.; Belokobylsky, A.; Khizanishvili, A.; Frontasyeva, M.; Pavlov, S.; Gundorina, S. Experimental substantiation of the possibility of developing selenium-and iodine-containing pharmaceuticals based on blue–green algae Spirulina platensis. J. Pharm. Biomed 2002, 30, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parial, D.; Pal, R. Green synthesis of gold nanoparticles using cyanobacteria and their characterization. Indian J. Appl. Res 2014, 4, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rösken, L.M.; Cappel, F.; Körsten, S.; Fischer, C.B.; Schönleber, A.; van Smaalen, S.; Geimer, S.; Beresko, C.; Ankerhold, G.; Wehner, S. Time-dependent growth of crystalline Au0-nanoparticles in cyanobacteria as self-reproducing bioreactors: 2. Anabaena cylindrica. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2016, 7, 312–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Ali, M.A.; Ali, M.U.; Mohammad, S. Hospital outcomes of obstetrical-related acute renal failure in a tertiary care teaching hospital. Ren. Fail. 2011, 33, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doshi, H.; Ray, A.; Kothari, I. Bioremediation potential of live and dead Spirulina: Spectroscopic, kinetics and SEM studies. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2007, 96, 1051–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lengke, M.F.; Fleet, M.E.; Southam, G. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles by filamentous cyanobacteria from a silver (I) nitrate complex. Langmuir 2007, 23, 2694–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudha, S.; Rajamanickam, K.; Rengaramanujam, J. Microalgae mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their antibacterial activity against pathogenic bacteria. Int. J. Nanomed. 2013, 51, 393–399. [Google Scholar]

- Husain, S.; Afreen, S.; Yasin, D.; Afzal, B.; Fatma, T. Cyanobacteria as a bioreactor for synthesis of silver nanoparticles-an effect of different reaction conditions on the size of nanoparticles and their dye decolorization ability. J. Microbiol. Methods 2019, 162, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, S.; Sardar, M.; Fatma, T. Screening of cyanobacterial extracts for synthesis of silver nanoparticles. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 31, 1279–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]