Charge-Exchange Emission from Hydrogen-Like Carbon Ions Colliding with Water Molecules

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Photon Emission Spectroscopy

2.2. Uncertainties

3. Results

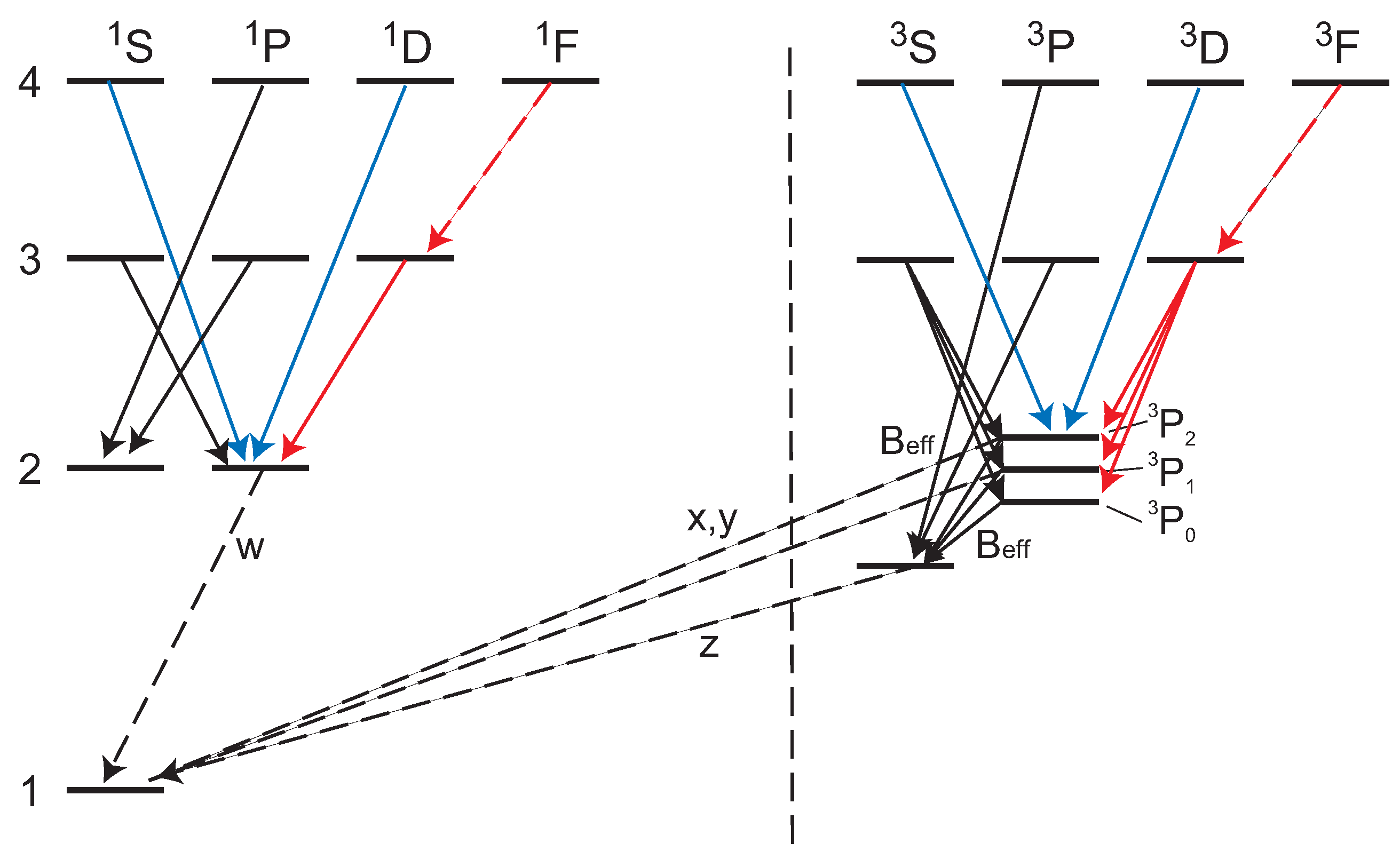

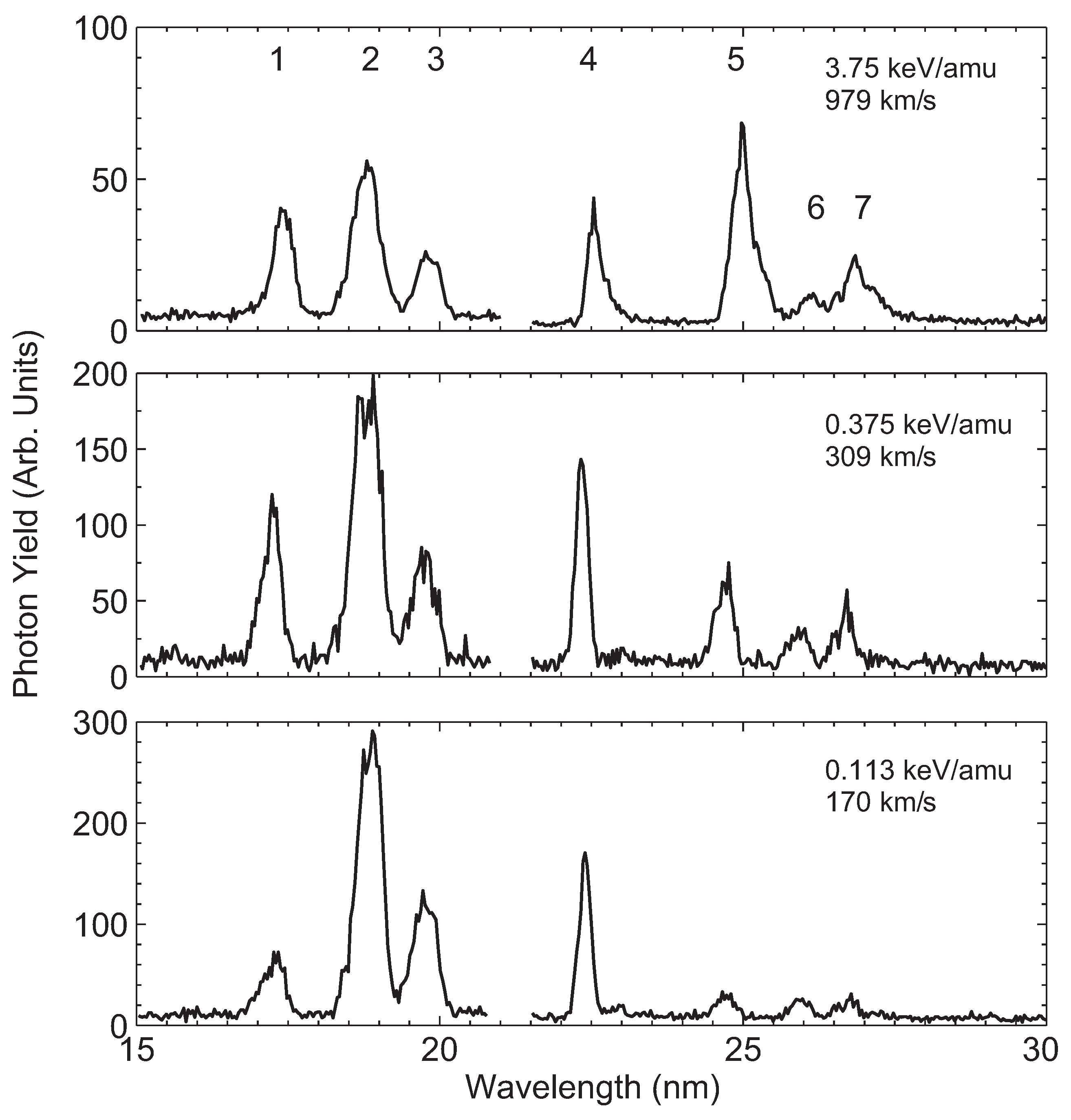

3.1. Cv EUV Line-Emission Spectra

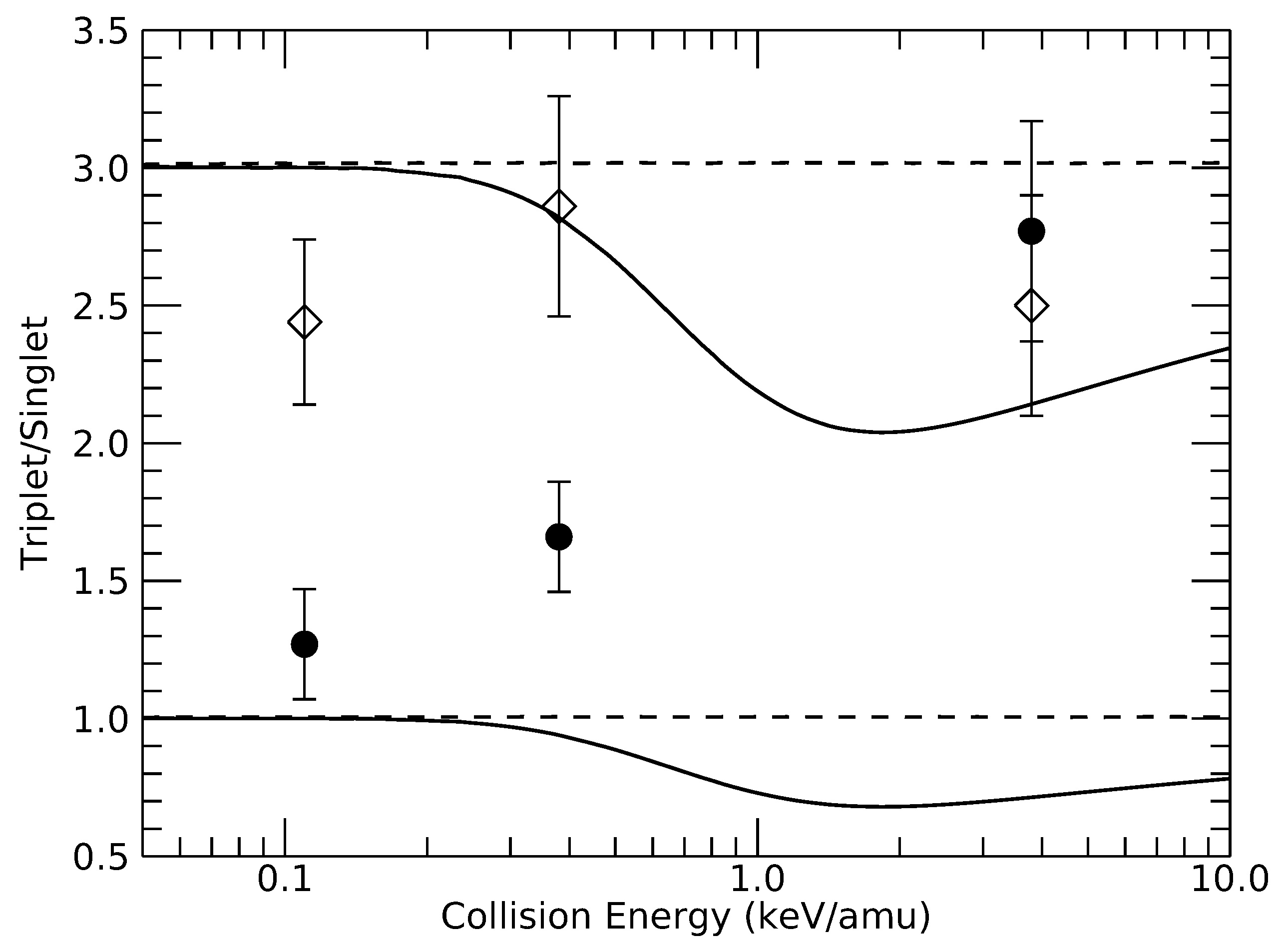

3.2. Triplet-to-Singlet Population

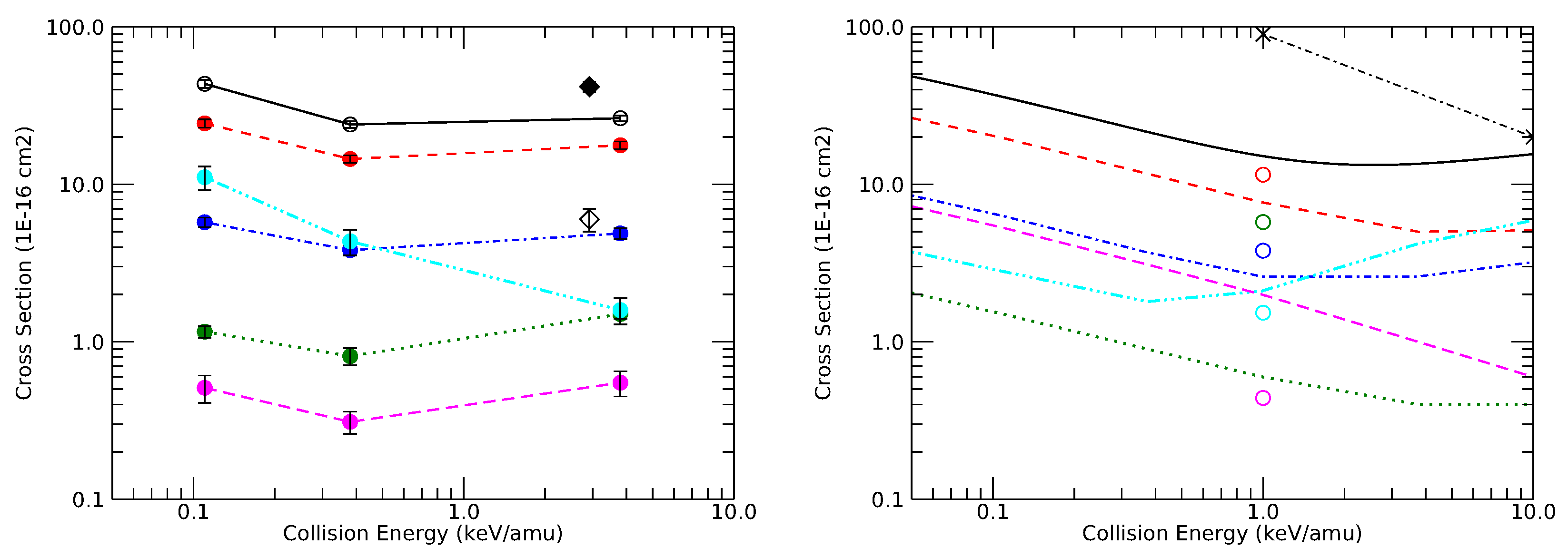

3.3. Emission Cross-Sections for the Cv K-series

3.4. Total Cross-Sections

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADC | Auto-ionizing Double Capture |

| CTMC | Classical Trajectory Monte Carlo |

| CXE | Charge-Exchange Emission |

| ECRIS | Electron Cyclotron Resonance Ion Source |

| EUV | Extreme UltraViolet |

| MCLZ | MultiChannel Landau Zener |

| SEC | Single Electron Capture |

References

- Dennerl, K. Charge Transfer Reactions. Space Sci. Rev. 2010, 157, 57–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisse, C.M.; Dennerl, K.; Englhauser, J.; Harden, M.; Marshall, F.E.; Mumma, M.J.; Petre, R.; Pye, J.P.; Ricketts, M.J.; Schmitt, J.H.M.M.; et al. Discovery of X-ray and Extreme Ultraviolet Emission from Comet C/Hyakutake 1996 B2. Science 1996, 274, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cravens, T.E. Comet Hyakutake x-ray source: Charge transfer of solar wind heavy ions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1997, 24, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharchenko, V.; Dalgarno, A. Variability of Cometary X-Ray Emission Induced by Solar Wind Ions. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2001, 554, L99–L102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porquet, D.; Dubau, J. X-ray photoionized plasma diagnostics with helium-like ions. Application to warm absorber-emitter in active galactic nuclei. Astron. Astrophys. Suppl. Ser. 2000, 143, 495–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennerl, K.; Lisse, C.M.; Bhardwaj, A.; Burwitz, V.; Englhauser, J.; Gunell, H.; Holmström, M.; Jansen, F.; Kharchenko, V.; Rodríguez-Pascual, P.M. First observation of Mars with XMM-Newton. High resolution X-ray spectroscopy with RGS. Astron. Astrophys. 2006, 451, 709–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, A.; Elsner, R.F.; Randall gladstone, G.; Cravens, T.E.; Lisse, C.M.; Dennerl, K.; Branduardi- Raymont, G.; Wargelin, B.J.; Hunter Waite, J., Jr.; Robertson, I. X-rays from solar system objects. Planet. Space Sci. 2007, 55, 1135–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branduardi-Raymont, G. X-ray studies of solar system objects: Past, present, and the next decade. Astron. Nachrichten 2017, 338, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, J.A.; Sembay, S. Identifying XMM-Newton observations affected by solar wind charge exchange. Part I. Astron. Astrophys. Suppl. Ser. 2008, 489, 837–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutroumpa, D.; Lallement, R.; Kharchenko, V.; Dalgarno, A. The Solar Wind Charge-eXchange Contribution to the Local Soft X-ray Background. Space Sci. Rev. 2008, 143, 87. [Google Scholar]

- Katsuda, S.; Tsunemi, H.; Mori, K.; Uchida, H.; Kosugi, H.; Kimura, M.; Nakajima, H.; Takakura, S.; Petre, R.; Hewitt, J.W.; Yamaguchi, H. Possible Charge-exchange X-ray Emission in the Cygnus Loop Detected with Suzaku. Astrophys. J. 2011, 730, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumbee, R.S.; Henley, D.B.; Stancil, P.C.; Shelton, R.L.; Nolte, J.L.; Wu, Y.; Schultz, D.R. Can Charge Exchange Explain Anomalous Soft X-Ray Emission in the Cygnus Loop? Astrophys. J. Lett. 2014, 787, L31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, Q.D.; Mao, S. Charge-exchange X-ray emission of nearby star-forming galaxies. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2012, 420, 3389–3395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezoe, Y.; Miyoshi, Y.; Kasahara, S.; Kimura, T.; Ishikawa, K.; Fujimoto, M.; Mitsuda, K.; Sahara, H.; Isobe, N.; Nakajima, H.; et al. Small Satellites With MEMS X-Ray Telescopes for X-Ray Astronomy and Solar System Exploration; Tokyo Metropolitan University: Hachioji, Japan, 2018; p. 106990V. [Google Scholar]

- Bodewits, D.; Juhasz, Z.; Hoekstra, R.; Tielens, A.G.G.M. Catching Some Sun: Probing the Solar Wind with Cometary X-Ray and Far-Ultraviolet Emission. Astrophys. J. 2004, 606, L81–L84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodewits, D.; Hoekstra, R. Electron capture in collisions between O6+ ions and H2O molecules. Phys. Rev. A 2007, 76, 32703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharchenko, V.; Rigazio, M.; Dalgarno, A.; Krasnopolsky, V.A. Charge Abundances of the Solar Wind Ions Inferred from Cometary X-Ray Spectra. Astrophys. J. 2003, 585, L73–L75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasnopolsky, V.A. CXO X-ray spectroscopy of comets and abundances of heavy ions in the solar wind. Icarus 2015, 247, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibeck, D.G.; Allen, R.; Aryan, H.; Bodewits, D.; Brandt, P.; Branduardi-Raymont, G.; Brown, G.; Carter, J.A.; Collado-Vega, Y.M.; Collier, M.; et al. Imaging Plasma Density Structures in the Soft X-Rays Generated by Solar Wind Charge Exchange with Neutrals. Space Sci. Rev. 2018, 214, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegmann, R.; Dennerl, K. X-ray tomography of a cometary bow shock. Astron. Astrophys. Suppl. Ser. 2005, 430, L33–L36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisse, C.M.; Christian, D.J.; Dennerl, K.; Wolk, S.J.; Bodewits, D.; Hoekstra, R.; Combi, M.R.; Makinen, J.T.T.; Dryer, M.; Fry, C.D.; et al. Chandra Observations of Comet 2P/Encke 2003: First Detection of a Collisionally Thin, Fast Solar Wind Charge Exchange System. Astrophys. J. 2005, 635, 1329–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, P.D.; Cumbee, R.S.; Lyons, D.; Gu, L.; Kaastra, J.; Shelton, R.L.; Stancil, P.C. Line Ratios for Solar Wind Charge Exchange with Comets. Astrophys. J. 2017, 844, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasnopolsky, V.A.; Greenwood, J.B.; Stancil, P.C. X-Ray and extreme ultraviolet emissions from comets. Space Sci. Rev. 2004, 113, 271–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porquet, D.; Mewe, R.; Dubau, J.; Raassen, A.J.J.; Kaastra, J.S. Line ratios for helium-like ions: Applications to collision-dominated plasmas. Astron. Astrophys. 2001, 376, 1113–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwadron, N.A.; Cravens, T.E. Implications of Solar Wind Composition for Cometary X-Rays. Astrophys. J. 2000, 544, 558–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodewits, D.; Hoekstra, R.; Seredyuk, B.; McCullough, R.W.; Jones, G.H.; Tielens, A.G.G.M. Charge Exchange Emission from Solar Wind Helium Ions. Astrophys. J. 2006, 642, 593–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seredyuk, B.; McCullough, R.; Tawara, H.; Gilbody, H.; Bodewits, D.; Hoekstra, R.; Tielens, A.; Sobocinski, P.; Pesic, D.; Hellhammer, R.; et al. Charge exchange and dissociative processes in collisions of slow He2+ ions with H2O molecules. Phys. Rev. A 2005, 71, 022705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodewits, D. Cometary X-rays. Solar Wind Charge Exchange in Cometary Atmospheres. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mawhorter, R.; Chutjian, A.; Cravens, T.E.; Djurić, N.; Hossain, S.; Lisse, C.M.; Macaskill, J.; Smith, S.; Simcic, J.; Williams, I. Absolute single and multiple charge exchange cross sections for highly charged C, O, and Ne ions on H2O, CO, and CO2. Phys. Rev. A 2007, 75, 032704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otranto, S.; Olson, R.E.; Beiersdorfer, P. Cometary X-rays: Line emission cross sections for multiply charged solar wind ion charge exchange. J. Phys. B 2007, 40, 1755–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liamsuwan, T.; Nikjoo, H. Cross sections for bare and dressed carbon ions in water and neon. Phys. Med. Biol. 2013, 58, 641–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beiersdorfer, P.; Lisse, C.M.; Olson, R.E.; Brown, G.V.; Chen, H. X-Ray Velocimetry of Solar Wind Ion Impact on Comets. Astrophys. J. 2001, 549, L147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suraud, M.G.; Hoekstra, R.; de Heer, F.J.; Bonnet, J.J.; Morgenstern, R. State selective electron capture into nl subshells in slow collisions of C5+ and N6+ with He and H2 studied by photon emission spectroscopy. J. Phys. B 1991, 24, 2543–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beijers, J.P.M.; Hoekstra, R.; Morgenstern, R. State selective charge transfer in slow collisions of O3+ with H and H2. J. Phys. B 1996, 29, 1397–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bliek, F.W.; Woestenenk, G.R.; Hoekstra, R.; Morgenstern, R. State-selective electron capture measurements for N4+-H and N4+-H2 collisions. Phys. Rev. A 1998, 57, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, D.; Cumbee, R.S.; Stancil, P.C. Charge Exchange of Highly Charged Ne and Mg Ions with H and He. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 2017, 232, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beiersdorfer, P. Laboratory X-Ray Astrophysics. Ann. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 2003, 41, 343–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, R.; Neill, P.A.; Beiersdorfer, P.; Harris, C.; Rakovic, M.; Wang, J.; Schultz, D.R.; Stancil, P.C. On the Significance of the Contribution of Multiple-Electron Capture Processes to Cometary X-Ray Emission. Astrophys. J. 2005, 629, L125–L128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1. |

| # | (nm) | Transitions | Collision Energy (keV/amu) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.113 | 0.375 | 3.75 | |||

| 1 | 17.3 | 4P–2S | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 |

| 2 | 18.8 | 4D–P, 4S–2P, 4P–2S | 6.1 ± 0.6 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.2 |

| 3 | 19.8 | 4D–2P, 4S–2P | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.1 |

| 4 | 22.7 | 3P–2S | 14 ± 1.4 | 7.2 ± 0.7 | 4.4 ± 0.4 |

| 5 | 24.8 | 3D–2P, 3P–2S | 2.7 ± 0.3 | 4.0 ± 0.4 | 10 ± 1.0 |

| 6 | 26.0 | 3S–2P, 3S–2P | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 1.8 ± 0.2 |

| 7 | 26.7 | 3D–2P | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 3.6 ± 0.4 |

| E (keV/amu) | 0.113 | 0.375 | 3.75 |

|---|---|---|---|

| v (km/s) | 170 | 309 | 979 |

| TS | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 2.8 ± 0.4 |

| TS | 2.4 ± 0.3 | 2.9 ± 0.4 | 2.5 ± 0.4 |

| SEC | 43.5 ± 2.6 | 24.0 ± 1.2 | 26.3 ± 1.1 |

| 2S | 24.4 ± 1.5 | 14.5 ± 0.8 | 17.7 ± 1.0 |

| 2P | 10.6 ± 0.7 | 7.4 ± 0.5 | 13.7 ± 1.0 |

| 1.2 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | |

| z | 24.4 ± 1.5 | 14.5 ± 0.8 | 17.7 ± 1.0 |

| w | 5.8 ± 0.4 | 3.8 ± 0.3 | 4.9 ± 0.4 |

| K | 11.1 ± 1.9 | 4.4 ± 0.8 | 1.6 ± 0.3 |

| K | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 |

| G | 4.5 ± 0.4 | 4.0 ± 0.4 | 3.9 ± 0.4 |

| H | 2.0 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 0.4 ± 0.1 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bodewits, D.; Hoekstra, R. Charge-Exchange Emission from Hydrogen-Like Carbon Ions Colliding with Water Molecules. Atoms 2019, 7, 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/atoms7010017

Bodewits D, Hoekstra R. Charge-Exchange Emission from Hydrogen-Like Carbon Ions Colliding with Water Molecules. Atoms. 2019; 7(1):17. https://doi.org/10.3390/atoms7010017

Chicago/Turabian StyleBodewits, Dennis, and Ronnie Hoekstra. 2019. "Charge-Exchange Emission from Hydrogen-Like Carbon Ions Colliding with Water Molecules" Atoms 7, no. 1: 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/atoms7010017

APA StyleBodewits, D., & Hoekstra, R. (2019). Charge-Exchange Emission from Hydrogen-Like Carbon Ions Colliding with Water Molecules. Atoms, 7(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/atoms7010017