Role of Simple Spatial Gradient in Reinforcing the Accuracy of Temperature Determination of HED Plasma via Spectral Line-Area Ratios

Abstract

1. Introduction

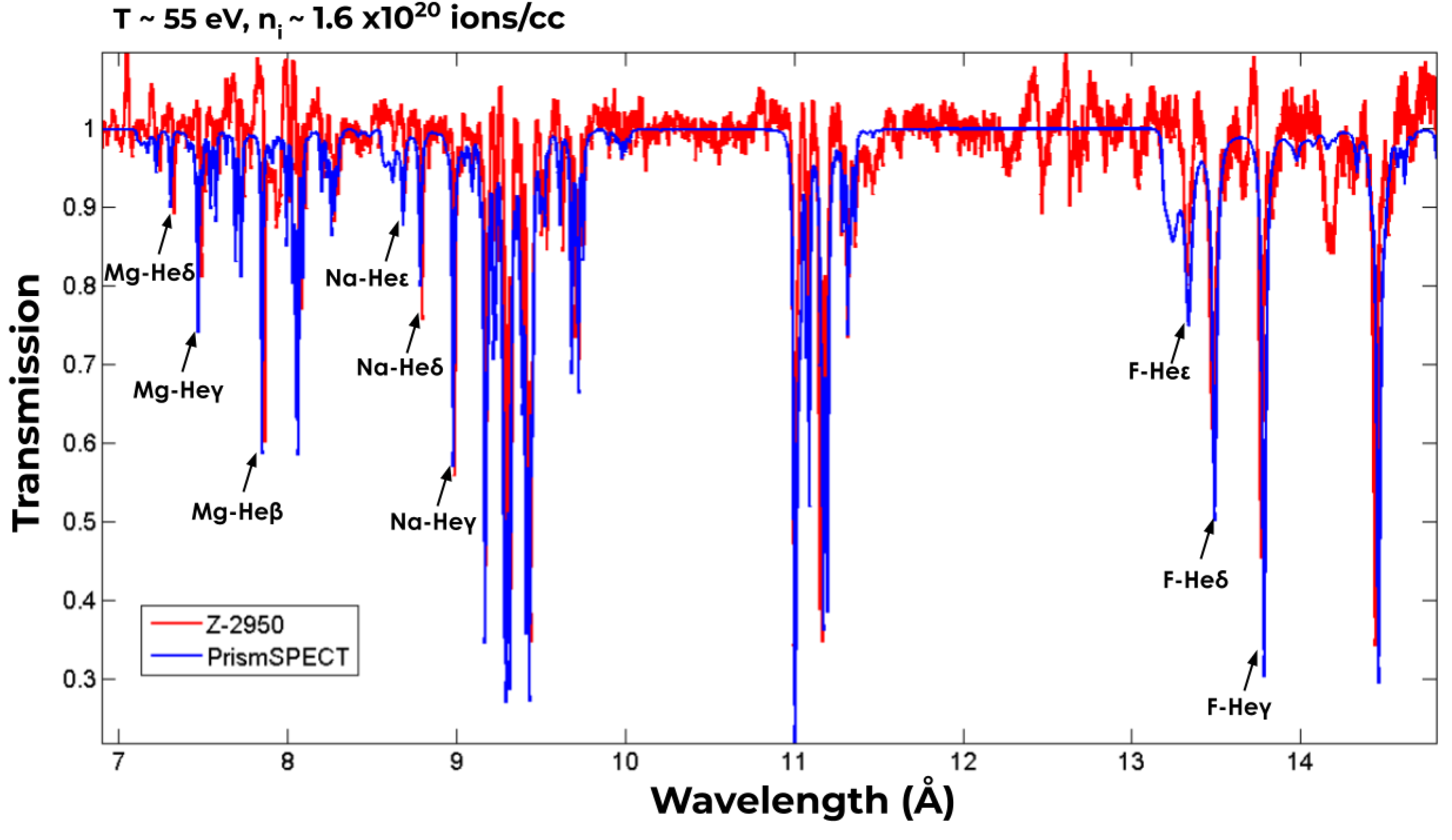

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

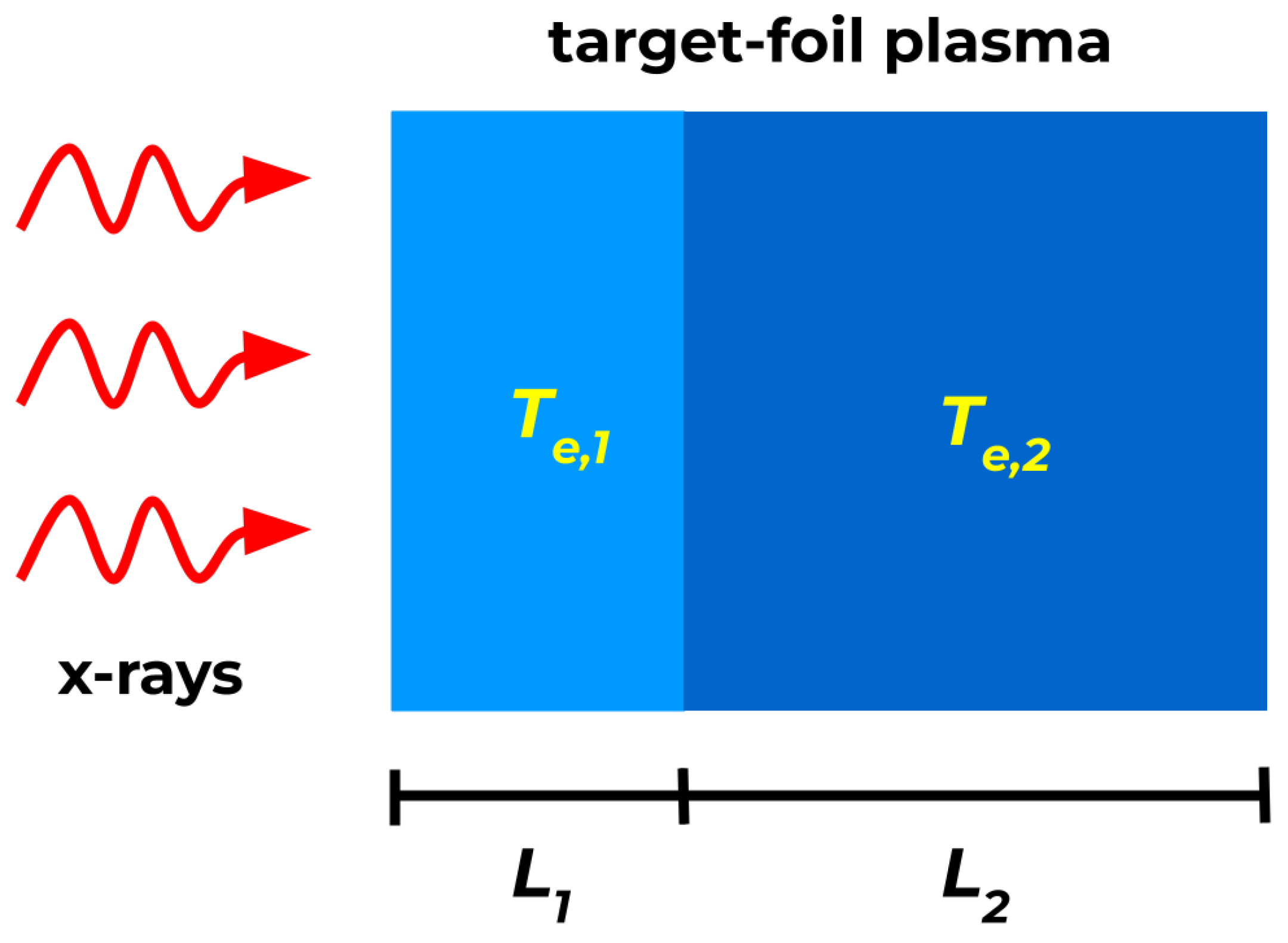

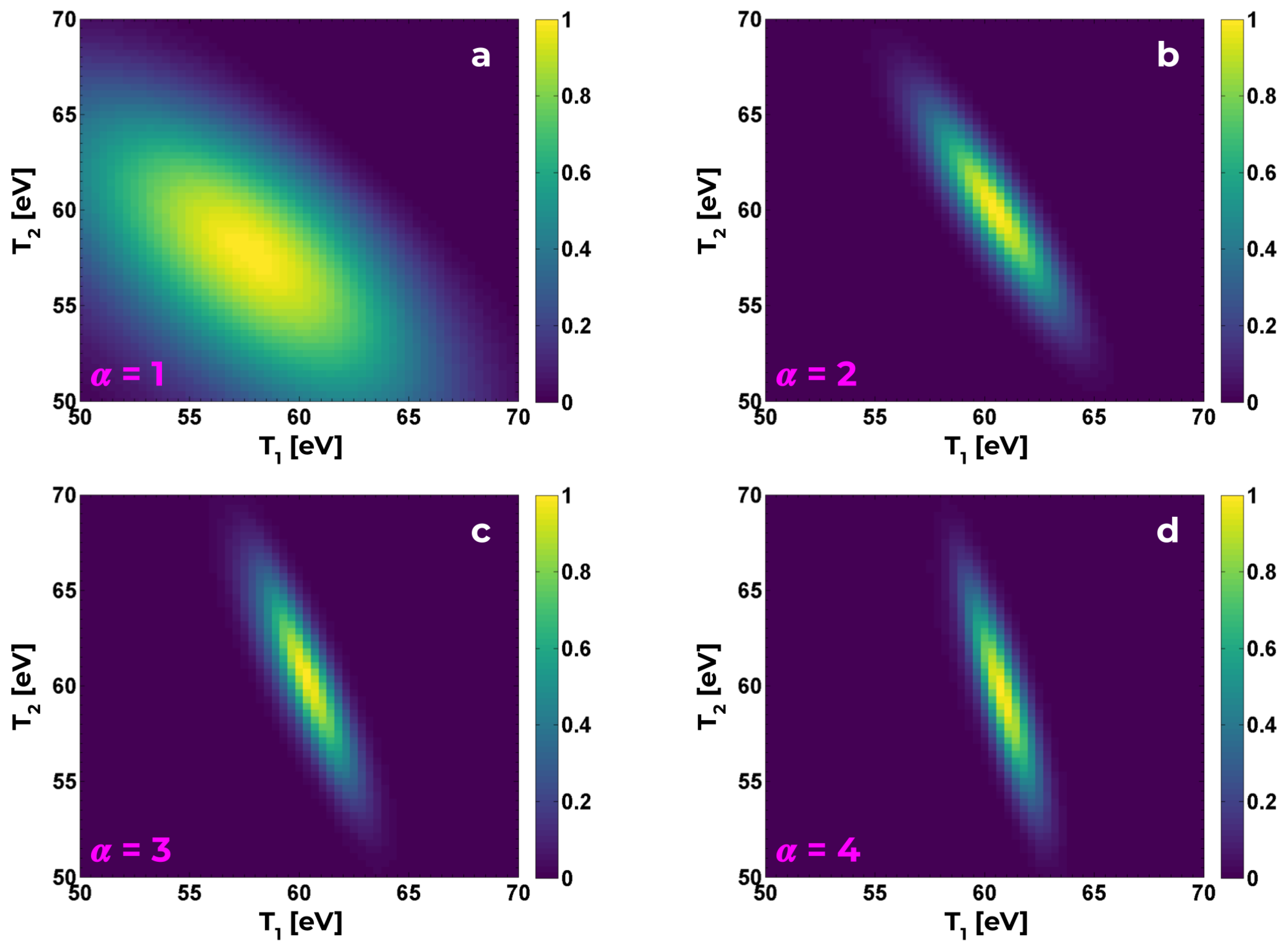

3.1. Description of Gradient Model

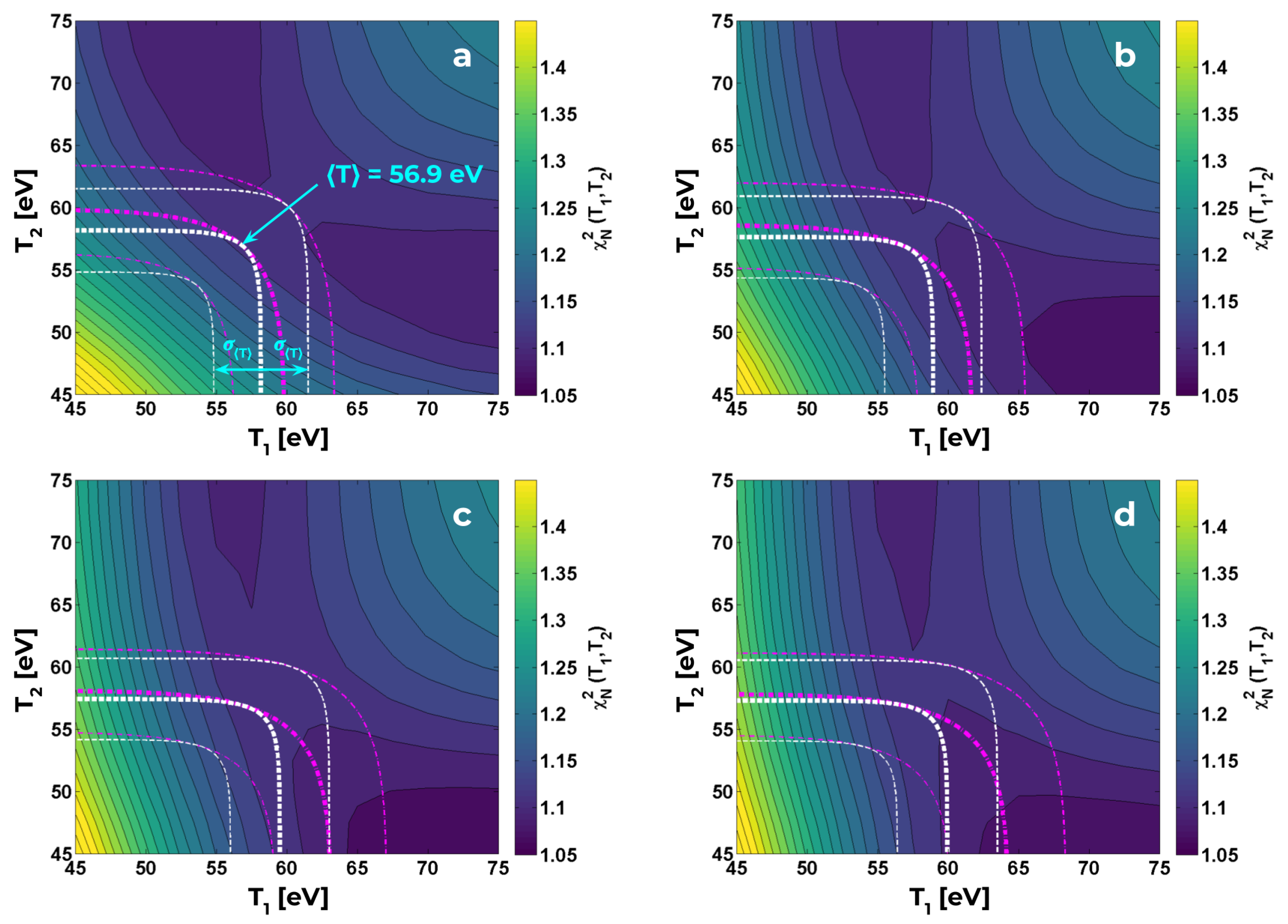

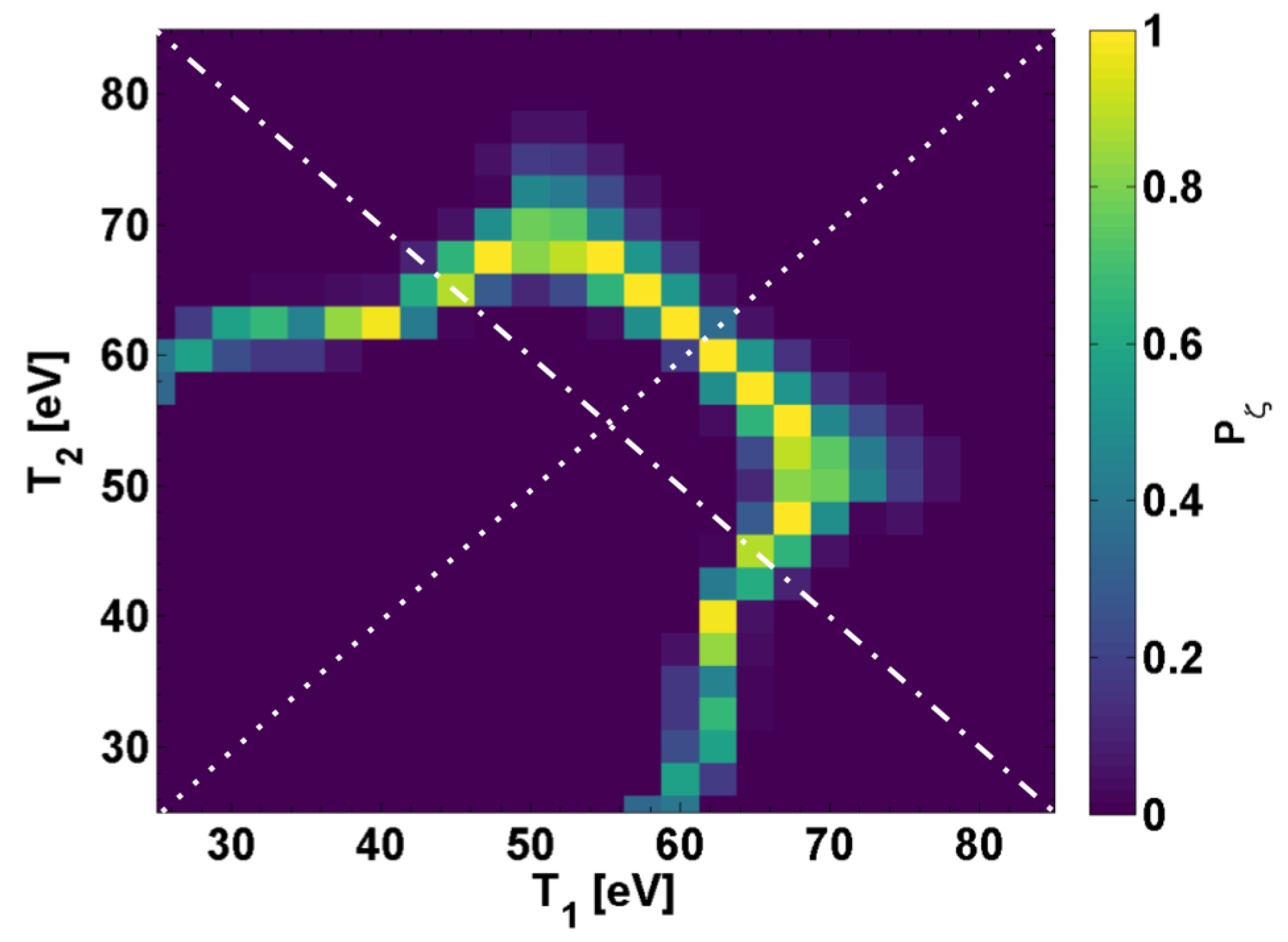

3.2. Minimization

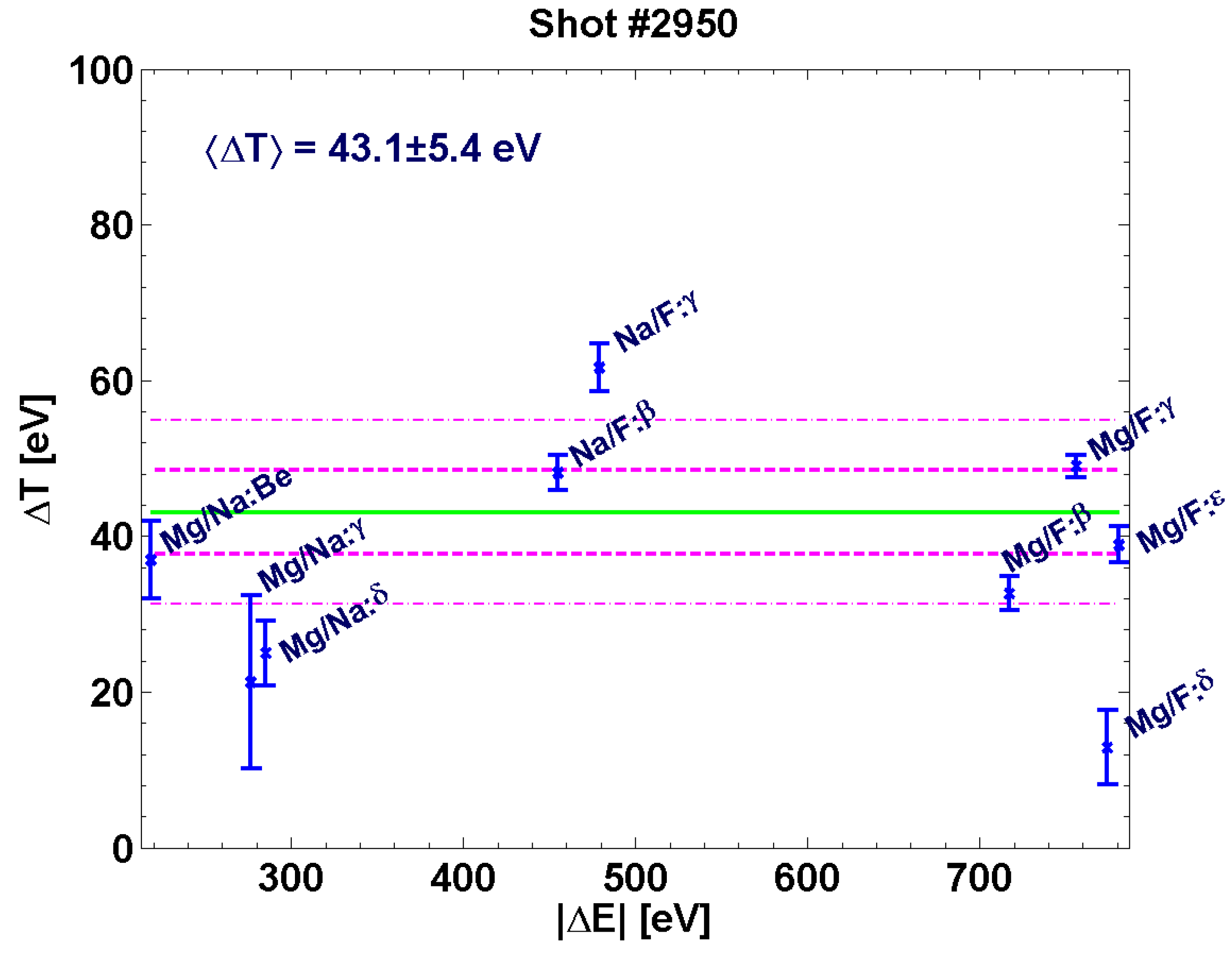

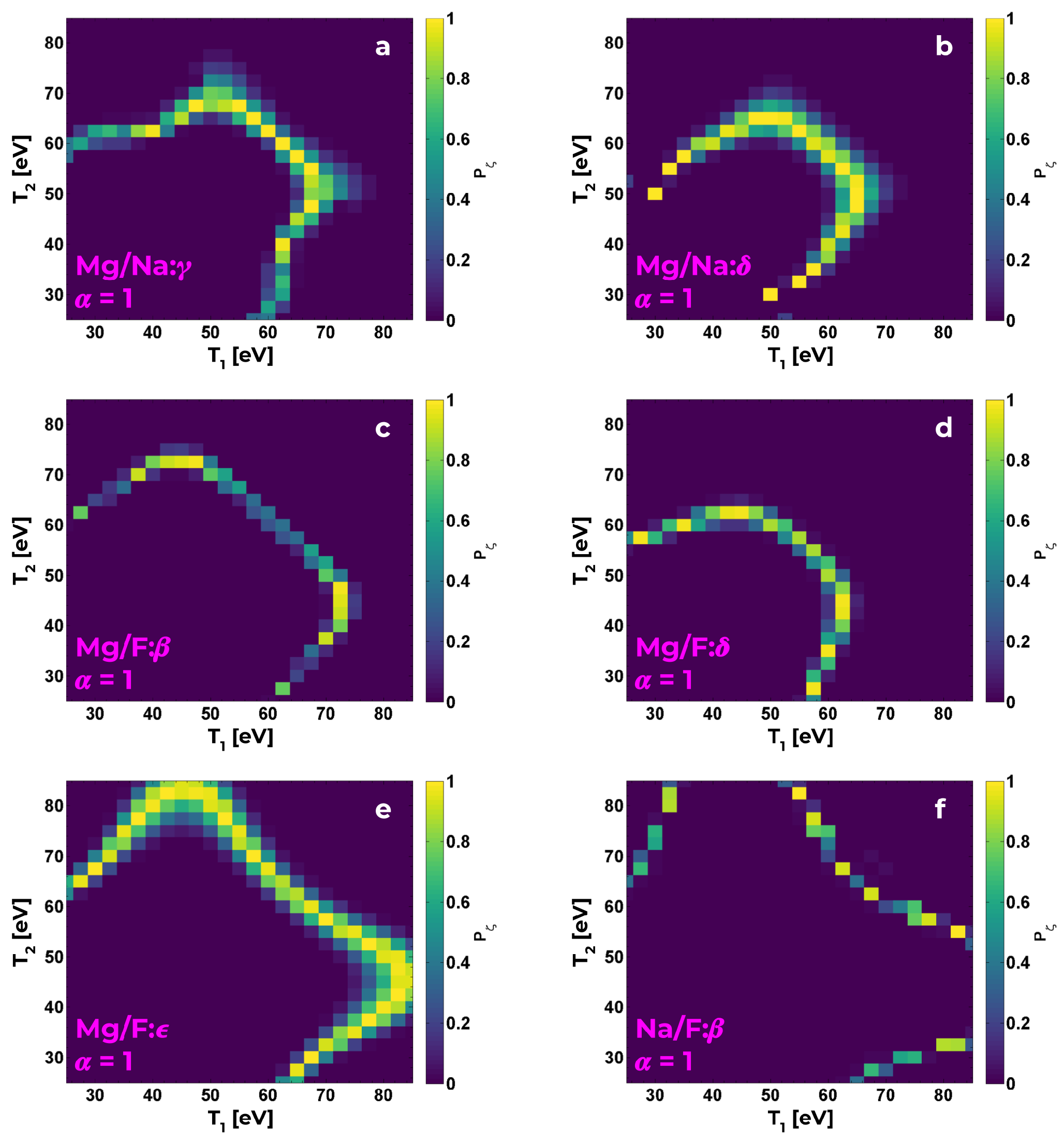

3.3. Quantitative Assessment via Line-Area Ratios

3.4. Sensitivity of Individual Line-Area Ratios

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGN | active galactic nuclei |

| HED | high-energy-density |

| KAP | potassium acid phthalate |

| LTE | local thermodynamic equilibrium |

| RAP | rubidium acid phthalate |

| RCC | return current can |

| TIXTL | time-integrated convex-crystal spectrometer |

| ZPDH | z-pinch dynamic hohlraum |

References

- Griem, H. Validity of Local Thermodynamic Equilibrium in Plasma Spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. 1963, 131, 1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzmann, D. Atomic Physics in Hot Plasmas; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kunze, H.J. Introduction to Plasma Spectroscopy; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; Volume 56. [Google Scholar]

- Mancini, R.; Bailey, J.; Hawley, J.; Kallman, T.; Witthoeft, M.; Rose, S.; Takabe, H. Accretion disk dynamics, photoionized plasmas, and stellar opacities. Phys. Plasmas 2009, 16, 041001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loisel, G.P.; Bailey, J.E.; Liedahl, D.; Fontes, C.; Kallman, T.; Nagayama, T.; Hansen, S.; Rochau, G.; Mancini, R.C.; Lee, R. Benchmark experiment for photoionized plasma emission from accretion-powered X-ray sources. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 119, 075001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagayama, T.; Bailey, J.; Loisel, G.; Rochau, G.; MacFarlane, J.; Golovkin, I. Numerical investigations of potential systematic uncertainties in iron opacity measurements at solar interior temperatures. Phys. Rev. E 2017, 95, 063206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loisel, G.; Bailey, J.; Nagayama, T.; Dunham, G.; Gard, P.; Rochau, G.; Colombo, A.; Edens, A.; Speas, R.; Looker, Q.; et al. Transforming the opacity science on Z using novel time-resolved spectroscopy. Presented at the 64th Annual Meeting of the APS Division of Plasma Physics, Spokane, WA, USA, 17–21 October 2022; Available online: https://meetings.aps.org/Meeting/DPP22/Session/BI02.3 (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- MacFarlane, J.; Golovkin, I.; Wang, P.; Woodruff, P.; Pereya, N. SPECT3D—A Multi-Dimensional Collisional-Radiative Code for Generating Diagnostic Signatures Based on Hydrodynamics and PIC Simulation Output. High Energy Density Phys. 2007, 3, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, T.; Koepke, M.; Kozlowski, P.; Riggs, G.; Steinberger, T.; Golovkin, I. Establishing an Isoelectronic Line Ratio Temperature Diagnostic for Soft X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy. High Energy Density Phys. 2022, 45, 101019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, T.S. Evaluation of X-ray Spectroscopic Techniques for Determining Temperature and Density in Plasmas; West Virginia University: Morgantownm, WV, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Marjoribanks, R.; Richardson, M.; Jaanimagi, P.; Epstein, R. Electron-temperature measurement in laser-produced plasmas by the ratio of isoelectronic line intensities. Phys. Rev. A 1992, 46, R1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielman, R.; Breeze, S.; Deeney, C.; Douglas, M.; Long, F.; Martin, T.; Matzen, M.; McDaniel, D.; McGurn, J.; Nash, T.; et al. PBFA Z: A 20-MA Z-pinch driver for plasma radiation sources. In Proceedings of the 1996 11th International Conference on High-Power Particle Beams, Prague, Czech Republic, 10–14 June 1996; Volume 1, pp. 150–153. [Google Scholar]

- Sanford, T.W. Overview of the dynamic hohlraum X-ray source at Sandia National Laboratories. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2008, 36, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochau, G.A.; Bailey, J.; Falcon, R.; Loisel, G.; Nagayama, T.; Mancini, R.; Hall, I.; Winget, D.; Montgomery, M.; Liedahl, D. ZAPP: The Z Astrophysical Plasma Properties collaborationa). Phys. Plasmas 2014, 21, 056308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagayama, T.; Bailey, J.E.; Loisel, G.; Hansen, S.B.; Rochau, G.A.; Mancini, R.; MacFarlane, J.; Golovkin, I. Control and diagnosis of temperature, density, and uniformity in X-ray heated iron/magnesium samples for opacity measurements. Phys. Plasmas 2014, 21, 056502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, E. Experiments on the testing of insulators using high voltage pulses. Elektrotechnische Z. 1924, 45, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Rochau, G.A.; Bailey, J.; MacFarlane, J. Measurement and analysis of X-ray absorption in Al and MgF2 plasmas heated by Z-pinch radiation. Phys. Rev. E 2005, 72, 066405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nash, T.; Derzon, M.; Chandler, G.; Fehl, D.; Leeper, R.; Porter, J.; Spielman, R.; Ruiz, C.; Cooper, G.; McGurn, J.; et al. Diagnostics on Z. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2001, 72, 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, J.; Rochau, G.; Mancini, R.; Iglesias, C.; MacFarlane, J.; Golovkin, I.; Pain, J.; Gilleron, F.; Blancard, C.; Cosse, P.; et al. Diagnosis of X-ray heated Mg/Fe opacity research plasmas. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2008, 79, 113104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loisel, G.; Bailey, J.; Rochau, G.; Dunham, G.; Nielsen-Weber, L.; Ball, C. A methodology for calibrating wavelength dependent spectral resolution for crystal spectrometers. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2012, 83, 10E133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagayama, T.; Bailey, J.; Loisel, G.; Rochau, G.; MacFarlane, J.; Golovkin, I. Calibrated simulations of Z opacity experiments that reproduce the experimentally measured plasma conditions. Phys. Rev. E 2016, 93, 023202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagayama, T.; Bailey, J.; Loisel, G.; Dunham, G.; Rochau, G.; Blancard, C.; Colgan, J.; Cossé, P.; Faussurier, G.; Fontes, C.J.; et al. Systematic study of L-shell opacity at stellar interior temperatures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 122, 235001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, T.; McWhirter, R. Validity criteria for local thermodynamic equilibrium in plasma spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. A 1990, 42, 6588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, W.; Liu, J. Rutherford backscattering spectrometry: Reminiscences and progresses. Mater. Chem. Phys. 1996, 46, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, M. Rutherford backscattering spectrometry (RBS). In Proceedings of the Workshop on Nuclear Data for Science and Technology: Materials Analysis, Trieste, Italy, 19–30 May 2003; Volume 34. [Google Scholar]

- Bevington, P.R.; Robinson, D.K. Data Reduction and Error Analysis; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Olivero, J.; Longbothum, R. Empirical fits to the Voigt line width: A brief review. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 1977, 17, 233–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiangdong, L.; Cheng, W.; Shensheng, H.; Zhizhan, X. Inter-stage line ratio of He-and Li-like Ti emissions for the electron temperature measurement. Plasma Sci. Technol. 2005, 7, 2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Riggs, G.A.; Koepke, M.E.; Lane, T.S.; Steinberger, T.E.; Kozlowski, P.M.; Golovkin, I.E. Role of Simple Spatial Gradient in Reinforcing the Accuracy of Temperature Determination of HED Plasma via Spectral Line-Area Ratios. Atoms 2023, 11, 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/atoms11070104

Riggs GA, Koepke ME, Lane TS, Steinberger TE, Kozlowski PM, Golovkin IE. Role of Simple Spatial Gradient in Reinforcing the Accuracy of Temperature Determination of HED Plasma via Spectral Line-Area Ratios. Atoms. 2023; 11(7):104. https://doi.org/10.3390/atoms11070104

Chicago/Turabian StyleRiggs, Greg A., Mark E. Koepke, Ted S. Lane, Thomas E. Steinberger, Pawel M. Kozlowski, and Igor E. Golovkin. 2023. "Role of Simple Spatial Gradient in Reinforcing the Accuracy of Temperature Determination of HED Plasma via Spectral Line-Area Ratios" Atoms 11, no. 7: 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/atoms11070104

APA StyleRiggs, G. A., Koepke, M. E., Lane, T. S., Steinberger, T. E., Kozlowski, P. M., & Golovkin, I. E. (2023). Role of Simple Spatial Gradient in Reinforcing the Accuracy of Temperature Determination of HED Plasma via Spectral Line-Area Ratios. Atoms, 11(7), 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/atoms11070104