Historical Biobanks in Breast Cancer Metabolomics— Challenges and Opportunities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

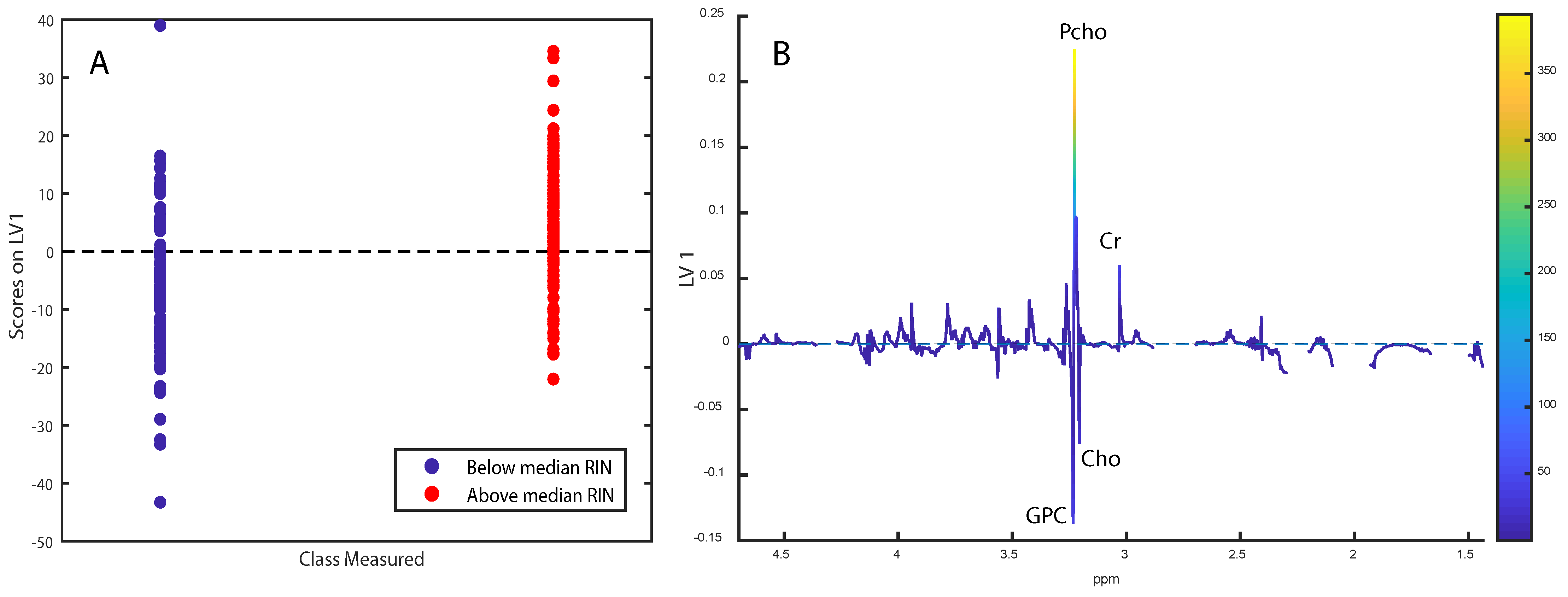

2.1. Tissue Integrity

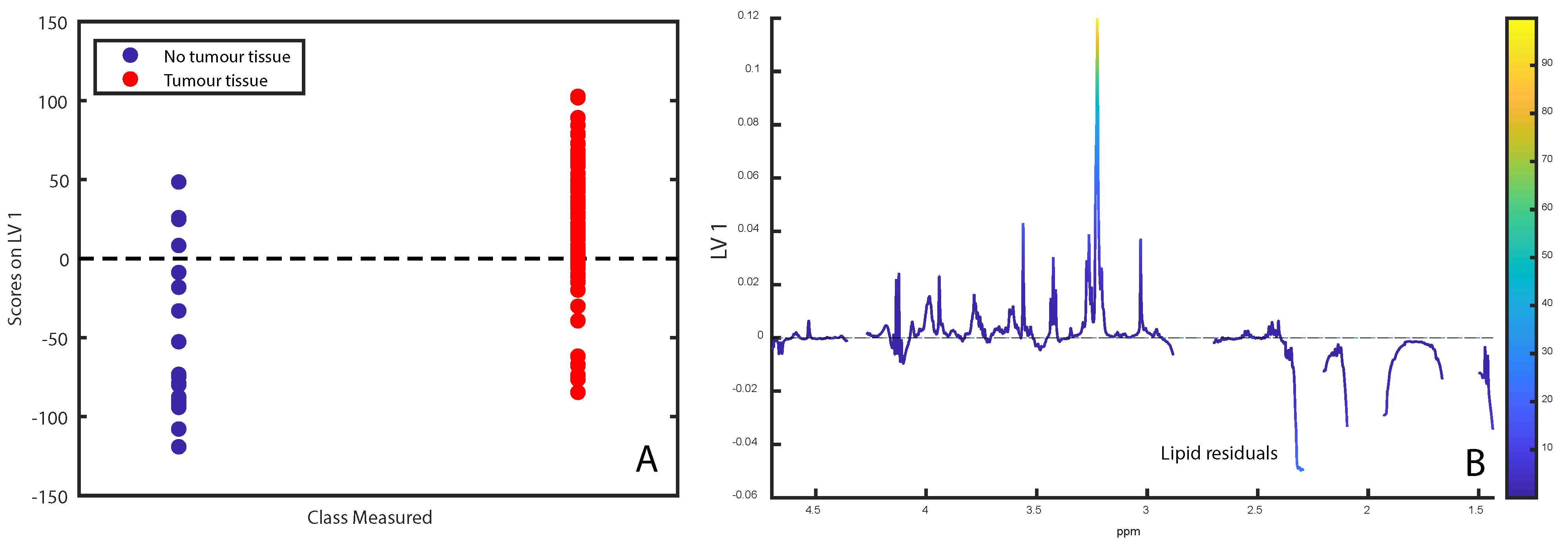

2.2. Histopathology and Immunohistochemistry

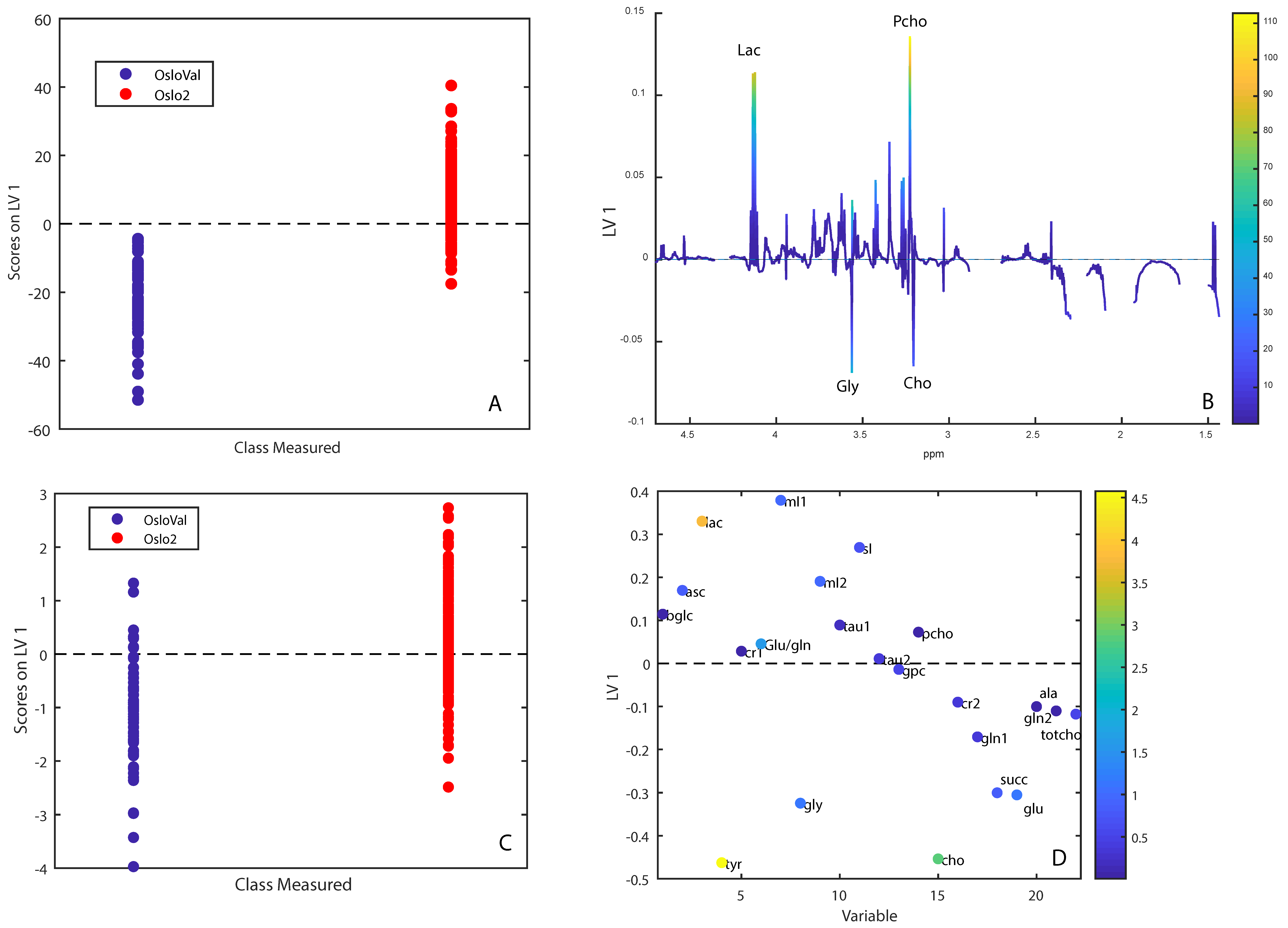

2.3. Metabolic Comparison of OsloVal and Oslo2

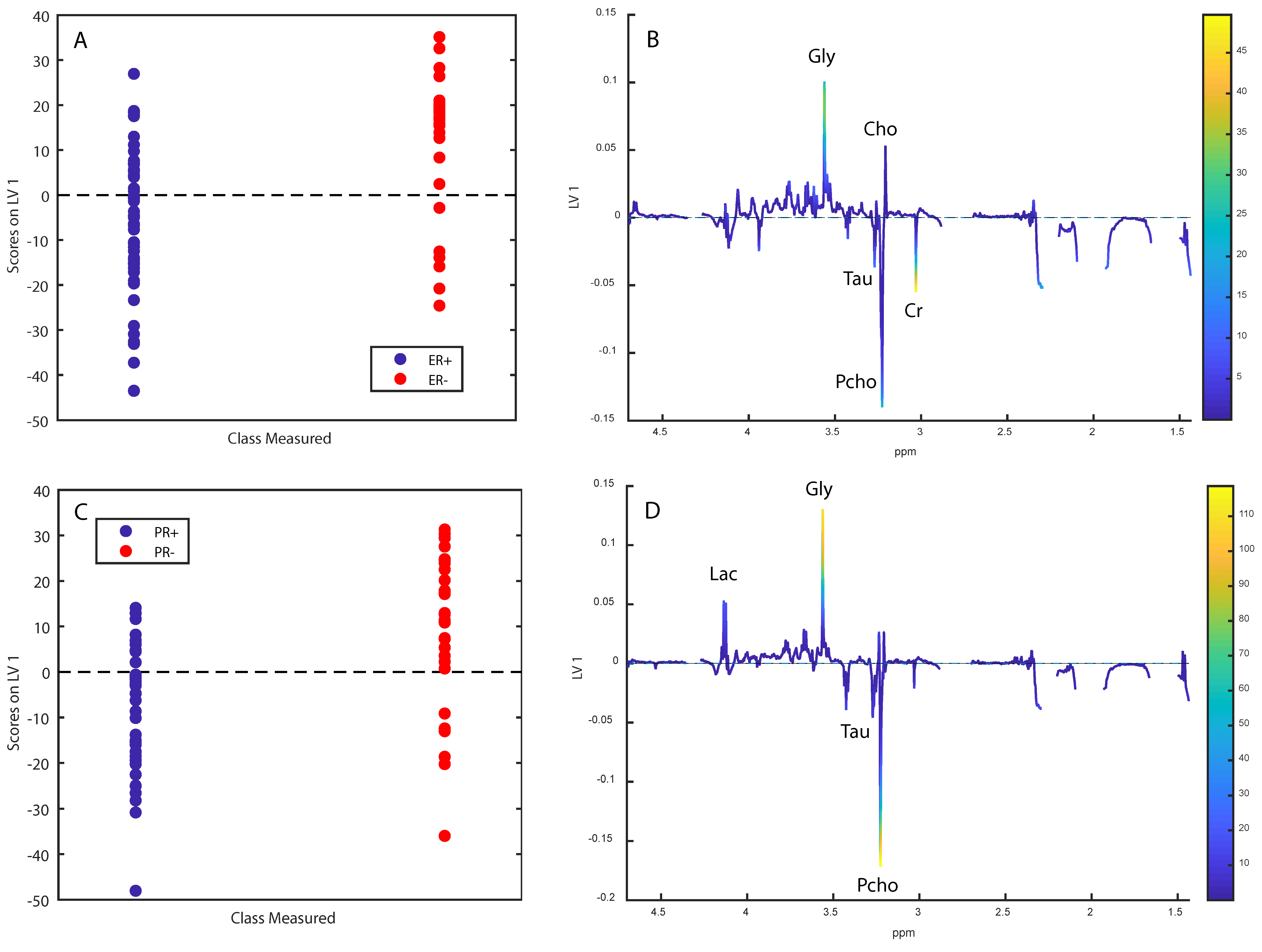

2.4. Metabolomic Analyses in OsloVal

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Sample Materials

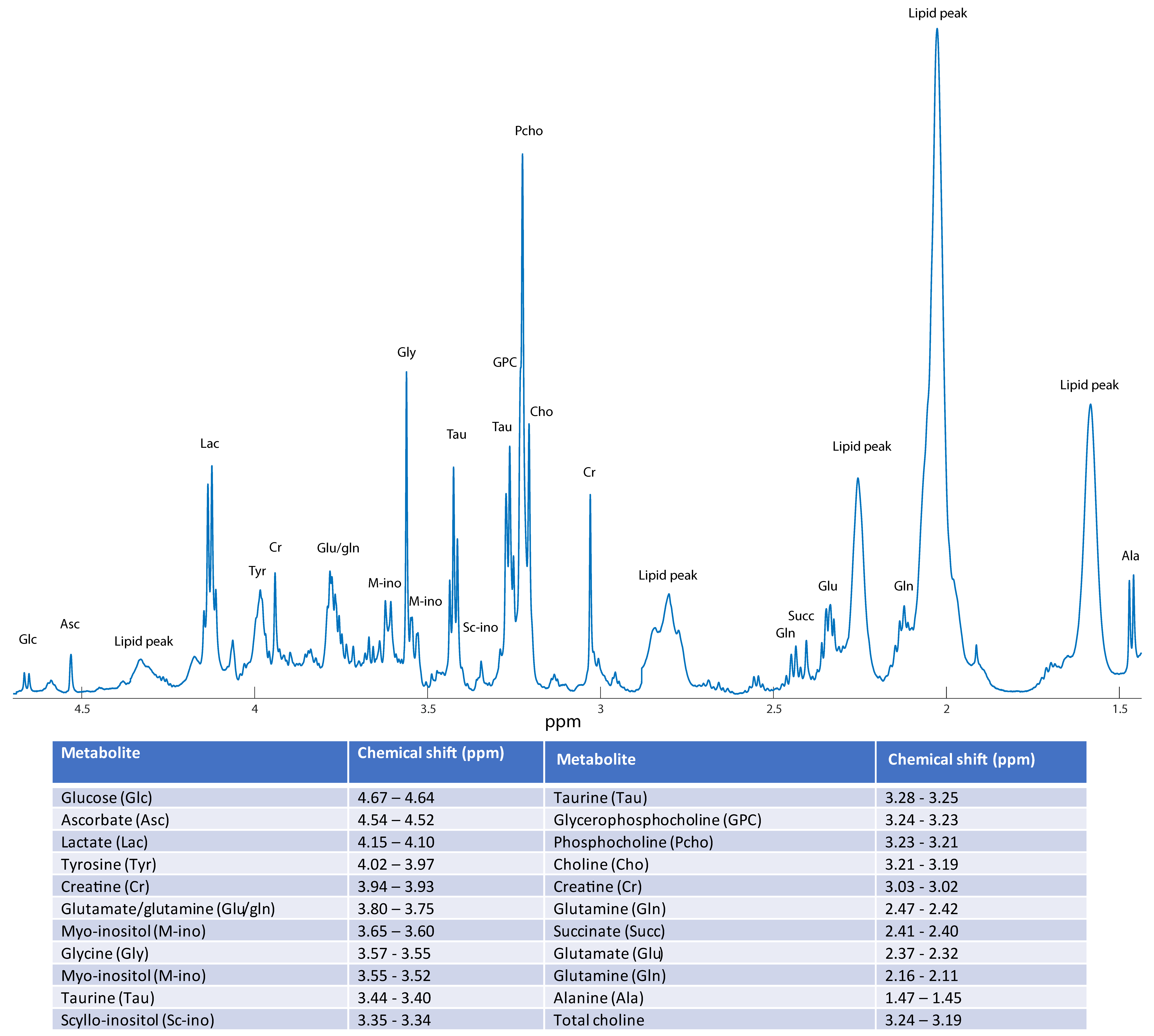

4.2. HR MAS MRS-Experiments

4.3. Spectral Preprocessing

4.4. Histologic Examination

4.5. Molecular Genetic Analyses

4.6. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Data Availability

References

- Perou, C.M.; Sørlie, T.; Eisen, M.B.; Van De Rijn, M.; Jeffrey, S.S.; Rees, C.A.; Pollack, J.R.; Ross, D.T.; Johnsen, H.; Akslen, L.A.; et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature 2000, 406, 747–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pozniak, Y.; Balint-Lahat, N.; Rudolph, J.D.; Lindskog, C.; Katzir, R.; Avivi, C.; Pontén, F.; Ruppin, E.; Barshack, I.; Geiger, T. System-wide Clinical Proteomics of Breast Cancer Reveals Global Remodeling of Tissue Homeostasis. Cell Syst. 2016, 2, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haukaas, T.H.; Euceda, L.R.; Giskeødegård, G.F.; Lamichhane, S.; Krohn, M.; Jernström, S.; Aure, M.R.; Lingjærde, O.C.; Schlichting, E.; Garred, Ø.; et al. Metabolic clusters of breast cancer in relation to gene- and protein expression subtypes. Cancer Metab. 2016, 4, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aure, M.R.; Vitelli, V.; Jernström, S.; Kumar, S.; Krohn, M.; Due, E.U.; Haukaas, T.H.; Leivonen, S.K.; Vollan, H.K.M.; Lüders, T.; et al. Integrative clustering reveals a novel split in the luminal A subtype of breast cancer with impact on outcome. Breast Cancer Res. BCR 2017, 19, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giskeødegård, G.F.; Grinde, M.T.; Sitter, B.; Axelson, D.E.; Lundgren, S.; Fjøsne, H.E.; Dahl, S.; Gribbestad, I.S.; Bathen, T.F. Multivariate modeling and prediction of breast cancer prognostic factors using MR metabolomics. J. Proteome Res. 2010, 9, 972–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Euceda, L.R.; Haukaas, T.H.; Giskeødegård, G.F.; Vettukattil, R.; Engel, J.; Silwal-Pandit, L.; Lundgren, S.; Borgen, E.; Garred, Ø.; Postma, G.; et al. Evaluation of metabolomic changes during neoadjuvant chemotherapy combined with bevacizumab in breast cancer using MR spectroscopy. Metabolomics 2017, 13, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.D.; Giskeødegård, G.F.; Bathen, T.F.; Sitter, B.; Bofin, A.; Lønning, P.E.; Lundgren, S.; Gribbestad, I.S. Prognostic value of metabolic response in breast cancer patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy. BMC Cancer 2012, 12, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giskeødegård, G.F.; Lundgren, S.; Sitter, B.; Fjøsne, H.E.; Postma, G.; Buydens, L.M.; Gribbestad, I.S.; Bathen, T.F. Lactate and glycine-potential MR biomarkers of prognosis in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancers. NMR Biomed. 2012, 25, 1271–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haukaas, T.H.; Moestue, S.A.; Vettukattil, R.; Sitter, B.; Lamichhane, S.; Segura, R.; Giskeødegård, G.F.; Bathen, T.F. Impact of Freezing Delay Time on Tissue Samples for Metabolomic Studies. Front. Oncol. 2016, 6, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moghen, A.; Halgunset, J. RNA-kvalitet i vevsprøver [RNA-quality in tissue samples]. Bioingeniøren 2015, 50, 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R.A.M.; Epis, M.R.; Horsham, J.L.; Kabir, T.D.; Richardson, K.L.; Leedman, P.J. Total RNA extraction from tissues for microRNA and target gene expression analysis: Not all kits are created equal. BMC Biotechnol. 2018, 18, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torell, F.; Bennett, K.; Rännar, S.; Lundstedt-Enkel, K.; Lundstedt, T.; Trygg, J. The effects of thawing on the plasma metabolome: Evaluating differences between thawed plasma and multi-organ samples. Metabolomics 2017, 13, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torell, F.; Bennett, K.; Cereghini, S.; Rännar, S.; Lundstedt-Enkel, K.; Moritz, T.; Haumaitre, C.; Trygg, J.; Lundstedt, T. Tissue sample stability: Thawing effect on multi-organ samples. Metabolomics 2015, 12, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.S.; Baek, H.M.; Kim, S.; Kim, M.J.; Youk, J.H.; Moon, H.J.; Kim, E.K.; Han, K.H.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, S.I.; et al. HR-MAS MR spectroscopy of breast cancer tissue obtained with core needle biopsy: Correlation with prognostic factors. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e51712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bathen, T.F.; Geurts, B.; Sitter, B.; Fjøsne, H.E.; Lundgren, S.; Buydens, L.M.; Gribbestad, I.S.; Postma, G.; Giskeødegård, G.F. Feasibility of MR metabolomics for immediate analysis of resection margins during breast cancer surgery. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sitter, B.; Bathen, T.F.; Jensen, L.R.; Axelson, D.; Halgunset, J.; Fjosne, H.E.; Lundgren, S.; Gribbestad, I.S. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy of breast cancer tissue used for tumor classification and lymph node prediction. Breast Cancer Res. BCR 2005, 7 (Suppl. 2), P7.01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Giskeødegård, G.F.; Cao, M.D.; Bathen, T.F. High-Resolution Magic-Angle-Spinning NMR Spectroscopy of Intact Tissue. In Metabonomics: Methods and Protocols; Bjerrum, J.T., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 37–50. [Google Scholar]

- Savorani, F.; Tomasi, G.; Engelsen, S.B. icoshift: A versatile tool for the rapid alignment of 1D NMR spectra. J. Magn. Reson. 2010, 202, 190–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| OsloVal-Cohort Description, n = 74 | |

|---|---|

| Age | 57.7 (33–85) |

| ER-status | 49 ER+, 25 ER- |

| PR-status | 40 PR+, 30 PR-, 4 unknown |

| Grade (1-3) | 8 (Grade 1), 28 (Grade 2), 24 (Grade 3), 14 (Unknown) |

| T-stage | 30 (T1), 29 (T2), 5 (T3), 6 (T4), 4 (Unknown) |

| N-stage | 40 (N0), 21 (N1), 5 (N2), 6 (N3), 2 (Unknown) |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy * | 24 (Yes), 50 (No) |

| Endocrine therapy * | 24 (Yes), 50 (No) |

| Five year survival | 68% |

| Ten year survival | 54% |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Madssen, T.S.; Cao, M.D.; Pladsen, A.V.; Ottestad, L.; Sahlberg, K.K.; Bathen, T.F.; Giskeødegård, G.F. Historical Biobanks in Breast Cancer Metabolomics— Challenges and Opportunities. Metabolites 2019, 9, 278. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo9110278

Madssen TS, Cao MD, Pladsen AV, Ottestad L, Sahlberg KK, Bathen TF, Giskeødegård GF. Historical Biobanks in Breast Cancer Metabolomics— Challenges and Opportunities. Metabolites. 2019; 9(11):278. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo9110278

Chicago/Turabian StyleMadssen, Torfinn S., Maria D. Cao, Arne V. Pladsen, Lars Ottestad, Kristine K. Sahlberg, Tone F. Bathen, and Guro F. Giskeødegård. 2019. "Historical Biobanks in Breast Cancer Metabolomics— Challenges and Opportunities" Metabolites 9, no. 11: 278. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo9110278

APA StyleMadssen, T. S., Cao, M. D., Pladsen, A. V., Ottestad, L., Sahlberg, K. K., Bathen, T. F., & Giskeødegård, G. F. (2019). Historical Biobanks in Breast Cancer Metabolomics— Challenges and Opportunities. Metabolites, 9(11), 278. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo9110278