Affinity Purification of O-Acetylserine(thiol)lyase from Chlorella sorokiniana by Recombinant Proteins from Arabidopsis thaliana

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

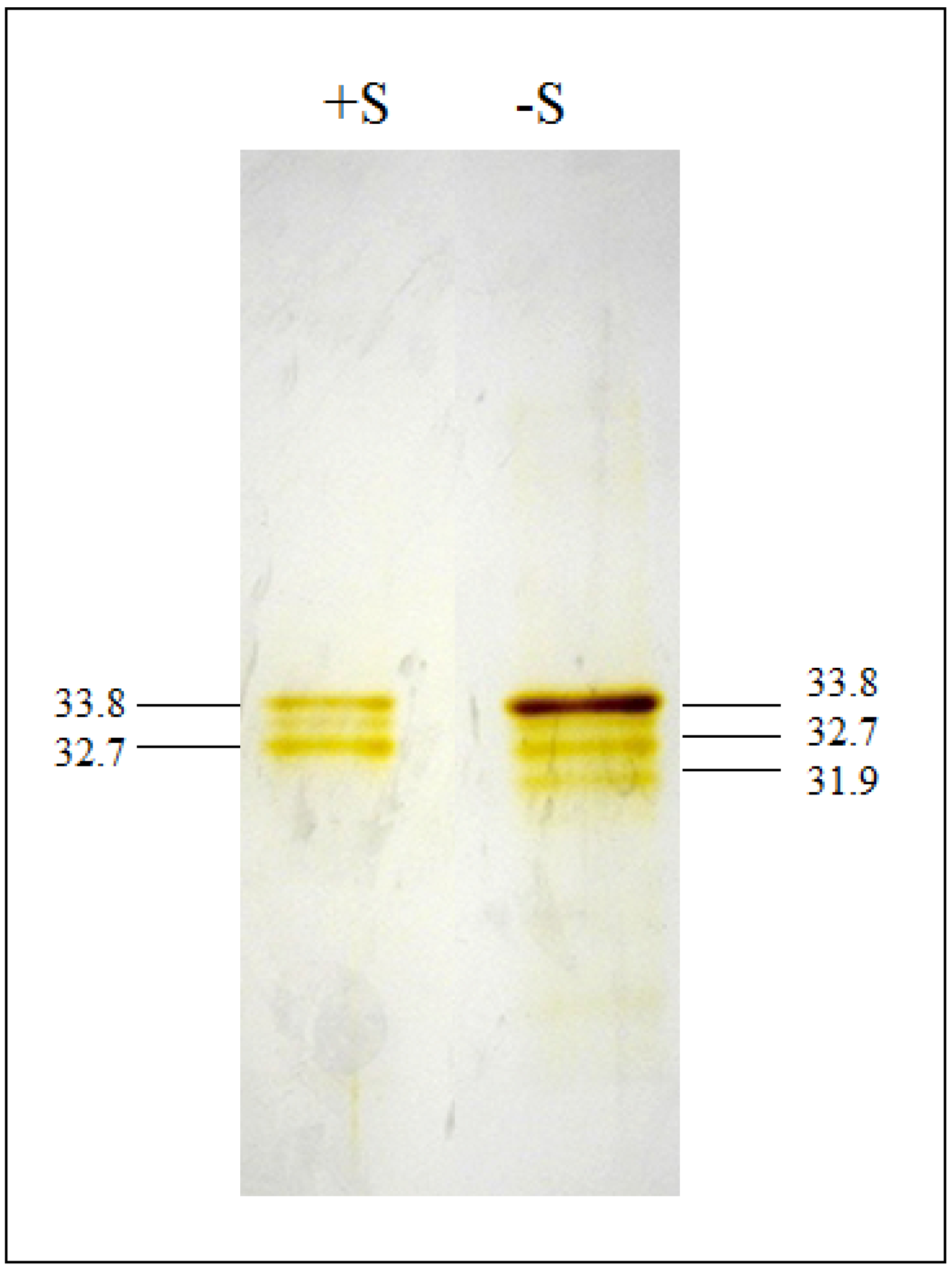

2.1. OASTLs Purification and CSC

| Fraction (+S) | Total Protein (mg) | OASTL Total Activity (U·mL−1) | OASTL Specific Activity (U·mg−1 prot) | Yield (%) | Purification Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude extract | 4.8 | 24.85 | 5.2 | 100 | 1 |

| Elution | 0.13 | 19.2 | 149 | 77 | 29 |

| Fraction (–S) | Total protein (mg) | OASTL total activity (U·mL−1) | OASTL specific activity (U·mg−1 prot) | Yield (%) | Purification level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude extract | 1.4 | 35 | 25 | 100 | 1 |

| Elution | 0.02 | 20.4 | 1020 | 58 | 41 |

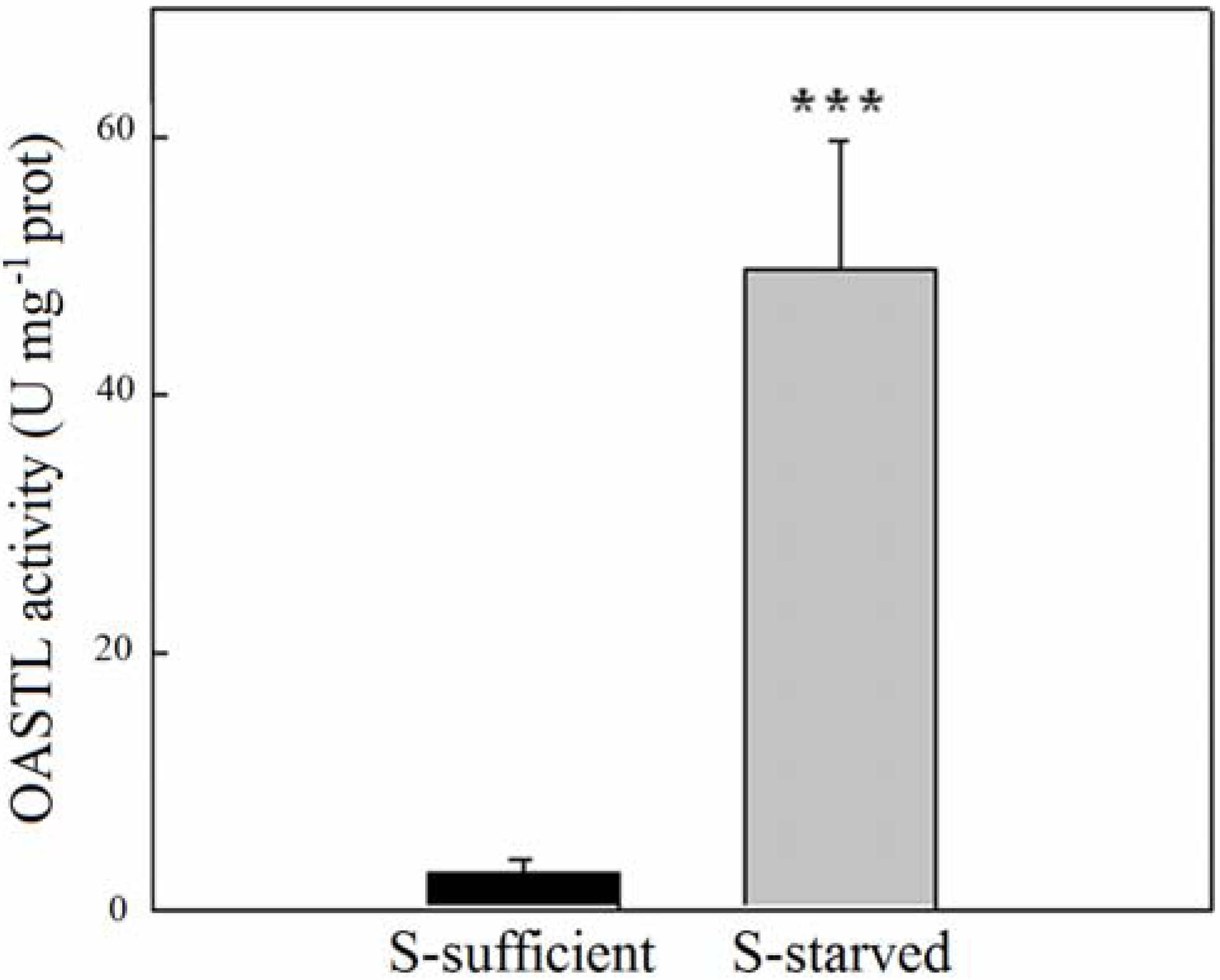

2.2. OASTL Activities

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Algal Growth Condition and Sulphate Starvation

3.2. OASTL Enzymatic Activities

3.3. OASTL Affinity Protein Purification

3.4. Silver Staining

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mazid, M.; Khan, T.A.; Mohammad, F. Response of crop plants under sulphur stress tolerance: A holistic approach. J. Stress Physiol. Biochem. 2011, 7, 23–57. [Google Scholar]

- Saito, K. Sulfur assimilatory metabolism. The long and smelling road. Plant Physiol. 2004, 136, 2443–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, M.; Norici, A.; Hell, R. Sulfur and phytoplankton: Acquisition, metabolism and impact on the environment. New Phytol. 2005, 166, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, H.; Kopriva, S.; Giordano, M.; Saito, S.; Hell, R. Sulfur assimilation in photosynthetic organisms: Molecular functions and regulations of transporters and assimilatory enzymes. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2011, 62, 157–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska, M.; Sirko, A. Recent advances in understanding plant response to sulphur-deficiency stress. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2008, 55, 457–471. [Google Scholar]

- Aksoy, M.; Pootakham, W.; Pollock, S.V.; Moseley, J.L.; González-Ballester, D.; Grossman, A.R. Tiered regulation of sulfur deprivation responses in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and identification of an associated regulatory factor. Plant Physiol. 2013, 162, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melis, A.; Chen, H.C. Chloroplast sulphate transport in green algae genes, proteins and effects. Photosynt. Res. 2005, 86, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pootakham, W.; Gonzalez-Ballester, D.; Grossman, A.R. Identification and regulation of plasma membrane sulfate transporters in Chlamydomonas. Plant Physiol. 2010, 153, 1653–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratti, S.; Knoll, A.H.; Giordano, M. Did sulfate availability facilitate the evolutionary expansion of chlorophyll a+c phytoplankton in the oceans? Geobiology 2011, 9, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratti, S.; Knoll, A.H.; Giordano, M. Grazers and phytoplankton growth in the oceans: An experimental and evolutionary perspective. PLoS One 2013, 8, e77349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birke, H.; Heeg, C.; Wirtz, M.; Hell, R. Successful fertilization requires the presence of at least one major O-acetylserine(thiol)lyase for cysteine synthesis in pollen of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2013, 163, 959–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hell, R.; Wirtz, M. Molecular biology, biochemistry and cellular physiology of cysteine metabolism in Arabidopsis thaliana. Arabidopsis Book 2011, 9, e0154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, R.; Berkowitz, O.; Wirtz, M.; Hopkins, L.; Hawkesford, M.J.; Hell, R. Genomic and functional characterization of the oas gene family encoding O-acetylserine(thiol)lyase enzyme catalyzing the final step in cysteine biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Gene 2000, 253, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birke, H.; Müller, S.J.; Rother, M.; Zimmer, A.D.; Hoernstein, S.N.W.; Wesenberg, D.; Wirtz, M.; Hell, R. The relevance of compartmentation for cysteine synthesis in photoautrophic organisms. Protoplasma 2012, 249, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carfagna, S.; Salbitani, G.; Vona, V.; Esposito, S. Changes in cysteine and O-acetyl-l-serine levels in the microalga Chlorella sorokiniana in response to the S-nutritional status. J. Plant Physiol. 2011, 168, 2188–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchant, S.S.; Prochnik, S.E.; Vallon, O.; Harris, E.H.; Karpowicz, S.J.; Witman, G.B.; Terry, A.; Salamov, A.; Fritz-Laylin, L.K.; Maréchal-Drouard, L.; et al. The Chlamydomonas Genome Reveals the Evolution of Key Animal and Plant Functions. Science 2007, 318, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kredich, N.M. Gene regulation of sulfur assimilation. In Sulfur Nutrition and Sulfur Assimilation in Higher Plants; De Kok, L.J., Stulen, I., Rennenberg, H., Brunold, C., Rauser, W.E., Eds.; SPB Academic Publishing: Hague, The Netherlands, 1993; pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Bromke, M.A. Amino Acid Biosynthesis Pathways in Diatoms. Metabolites 2013, 3, 294–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Ballester, D.; Casero, D.; Cokus, S.; Pellegrini, M.; Merchant, S.S.; Grossman, A.R. RNA-seq analysis of sulfur-deprived Chlamydomonas cells reveals aspects of acclimation critical for cell survival. Plant Cell 2010, 22, 2058–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravina, C.G.; Chang, C.I.; Tsakraklides, P.G.; McDermott, J.P.; Vega, J.M.; Leustek, T.; Gotor, C.; Davies, P. The sac mutants of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii reveal transcriptional and posttranscriptional control of cysteine biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 2002, 130, 2076–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaran, S.; Yi, H.; Krishan, H.B.; Jez, J.M. Assembly of the cysteine synthase complex and the regulatory role of protein-protein interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 10268–10275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, M.; Birke, H.; Heeg, C.; Muller, C.; Hosp, F.; Throm, C.; König, S.; Feldman-Salit, A.; Rippe, K.; Petersen, G.; et al. Structure and function of the hetero-oligomeric cysteine synthase complex in plants. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 32810–32817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman-Salit, A.; Wirtz, M.; Hell, R.; Wade, R.C. A mechanistic model of the cysteine synthase complex. J. Mol. Biol. 2009, 386, 37–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, M.; Berkowitz, O.; Droux, M.; Hell, R. The cysteine synthase complex from plant. Mitochondrial serine acetyltransferase from Arabidopsis thaliana carries a bifunctional domain for catalysis and protein-protein interaction. Eur. J. Biochem. 2001, 268, 686–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, C.; Calo, L.; Romero, L.C.; Garcìa, I.; Gotor, C. An O-acetylserine(thiol)lyase homolog with l-cysteine desulfhydrase activity regulates cysteine homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2010, 152, 656–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.; de Winter, M.; Tramper, J.; Mur, L.R.; Snel, J.; Wijffels, R.H. Efficiency of light utilization of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii under medium-duration light/dark cycles. J. Biotechnol. 1999, 78, 123–137. [Google Scholar]

- Ngangkham, M.; Ratha, S.K.; Prasanna, R.; Saxena, A.K.; Dhar, D.W.; Sarika, C.; Prasad, R.B. Biochemical modulation of growth, lipid quality and productivity in mixotrophic cultures of Chlorella sorokiniana. Springerplus 2012, 1, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.P.; Kviderovà, J.; Trisska, J.; Elster, J. Chlorella mirabilis as a Potential Species for Biomass Production in Low-Temperature Environment. Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 97. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, L.A.; Ogden, K.L.; Jia, F. Comparative Study of Biosorption of Copper(II) by Lipid Extracted and Non-Extracted Chlorella sorokiniana. Clean Soil Air Water. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, M.; Hell, R. Functional analysis of the cysteine synthase protein complex from plants: Structural, biochemical and regulatory properties. J. Plant Physiol. 2006, 163, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Kumada, Y.; Imanaka, H.; Imamura, K.; Nakanishi, K. Cloning, overexpression, purification, and characterization of O-acetylserine sulfhydrylase-B from Escherichia coli. Protein Expr. Purif. 2006, 47, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeg, C.; Kruse, C.; Jost, R.; Gutensohn, M.; Ruppert, T.; Wirtz, M.; Hell, R. Analysis of the Arabidopsis O-acetylserine(thiol)lyase gene family demonstrates compartment-specific differences in the regulation of cysteine synthesis. Plant Cell 2008, 20, 168–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaitonde, M.K. A spectrometric method for the direct determination of cysteine in the presence of other naturally occurring amino acids. Biochem. J. 1967, 104, 627–633. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, M.M. Rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabilloud, T. Silver staining of 2-D electrophoresis gels. Methods Mol. Biol. 1999, 112, 297–305. [Google Scholar]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Salbitani, G.; Wirtz, M.; Hell, R.; Carfagna, S. Affinity Purification of O-Acetylserine(thiol)lyase from Chlorella sorokiniana by Recombinant Proteins from Arabidopsis thaliana. Metabolites 2014, 4, 629-639. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo4030629

Salbitani G, Wirtz M, Hell R, Carfagna S. Affinity Purification of O-Acetylserine(thiol)lyase from Chlorella sorokiniana by Recombinant Proteins from Arabidopsis thaliana. Metabolites. 2014; 4(3):629-639. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo4030629

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalbitani, Giovanna, Markus Wirtz, Rüdiger Hell, and Simona Carfagna. 2014. "Affinity Purification of O-Acetylserine(thiol)lyase from Chlorella sorokiniana by Recombinant Proteins from Arabidopsis thaliana" Metabolites 4, no. 3: 629-639. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo4030629

APA StyleSalbitani, G., Wirtz, M., Hell, R., & Carfagna, S. (2014). Affinity Purification of O-Acetylserine(thiol)lyase from Chlorella sorokiniana by Recombinant Proteins from Arabidopsis thaliana. Metabolites, 4(3), 629-639. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo4030629