The residual active components of goji berry residue (such as polysaccharides and polyphenols) can form complexes with feed proteins. Previous studies have shown that nanocrystals formed by self-assembly of goji leaf extract and whey protein can enhance the bioavailability of polyphenols and strengthen their antioxidant effects. These complexes may help protect muscle cell membrane integrity, potentially attenuate postmortem stress responses, and thereby improve meat tenderness; however, this proposed mechanism requires further experimental validation [

31]. Jiale Liao discovered that fermented goji berry residue supplementation could have a significant impact on improving the average daily gain, feed efficiency, and nutrient digestibility in Tan sheep, but it did not investigate its implications on muscle amino acid and fatty acid compositions and volatile compounds. Thus, it is still unclear what effect fermented goji berry residue has on the nutritional properties and flavor quality of Tan sheep muscle. Accordingly, the aim of the present study was to evaluate the effects of dietary inclusion of 4% fermented goji berry residue (FGB) on carcass traits and meat quality, with a particular focus on muscle fatty acid and amino acid profiles and flavor-related compounds. Using a combined RNA-seq transcriptomic and GC-TOFMS-based untargeted metabolomic approach, we further explored potential molecular mechanisms associated with changes in meat quality.

4.1. Impact of FGB on Meat Quality in Fattening Tan Sheep

An important visual attribute of meat that determines consumer choices of lamb is its meat color, which is measured in brightness (

L*), redness (

a*), and yellowness (

b*). According to the research, Chinese customers are usually more interested in the meat color traits of local lamb, and the issues related to food safety are closely associated with the meat color stability [

32]. To illustrate this, LD of lambs in rotating grazing (NG) had higher values of lightness (

L*) and yellowness (

b*), which can more likely match the preferences of consumers towards a fresh appearance [

33]. This study found that FGB supplementation significantly altered the meat color parameters of various muscles, and compared to the control group, FGB significantly increased the brightness

(L*) of LD, TM, and GM, while the redness (

a*) was only significantly increased in LD, consistent with previous research results [

7,

34]. A higher degree of redness (

a*) denotes more vividness of color and fresher meat, and fermented

Lycium barbarum residue can greatly enhance the vital visual characteristics of Tan lamb meat. Variations in pH have a direct influence on the stability and oxidation status of myoglobin and, thus, the color of meat. The higher the pH, the darker the coloration of the meat, and the lower the pH, the higher the L value [

35]. The pH

45min of the LD of the FGB group showed a downward trend, which can be one of the reasons why the L value of this muscle is high. In the processing of lamb, pH reduction can enhance the quality of meat, yet it can have an adverse effect on tenderness when it is too acidic [

36]. Tenderness is a very important factor in meat quality; it indicates the structure of muscle fibers and the content of fats. This finding proposes that the effect of FGB supplementation on muscle fiber structure or collagen composition of GM can be stronger. Furthermore, pH changes control the intensity and juiciness of the meat flavor by controlling the enzyme activities and the metabolic byproducts (e.g., lactate and volatile compounds) [

37]. In summary, the LD underwent a more detailed study of amino acids, flavor compounds, fatty acids, and volatile compounds to further explain the impact of fermented goji pomace supplementation on the quality and flavor of its meat in Tan sheep.

In addition, studies have shown that an increase in IMF can significantly enhance tenderness, juiciness, and flavor acceptance. Consumers rate the tenderness and flavor of lamb with high IMF (e.g., 4.4%) higher, but excessively high IMF (e.g., >4.4%) may lead to a greasy sensation and reduce acceptance [

38]. Our research found that the fat content of muscles at different parts in the control group was higher than 4.4%, which may be due to the use of fattening basic feed and cage feeding methods. However, the FGB group significantly reduced the fat content in muscles at parts such as LD, which may effectively reduce the greasy sensation caused by excessive fat content, thereby improving the flavor of fattened Tan sheep and increasing consumer acceptance. Our results also showed that shear force, cooking loss, and drip loss did not change significantly, which may be because the range in which IMF content affects tenderness and juiciness is mainly between 1% and 6% [

39,

40]. Although our fat content results decreased, they did so compared to the control group (>6%), and the reduced fat content was close to 6%, especially in LD tissue, which is in the desirable range for consumer acceptance. Therefore, our study found that fermented goji berry residue could reduce fat content to improve flavor acceptability without adversely affecting tenderness and juiciness, maintaining the water-holding capacity of Tan sheep muscle. The mechanism by which IMF influences flavor mainly involves lipid metabolism and fatty acid derivatives. The fatty acids in IMF produce key volatile compounds during oxidation [

41]. Changes in IMF are often accompanied by alterations in lipid composition, mainly in the composition and content of saturated fatty acids (SFAs), monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs), and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), which may enhance flavor and the nutritional health of fatty acids [

42]. Also, mutton is known to have a direct impact on the nutritional values and flavor due to the content of crude protein. In taste development, the aroma precursors of mutton (proteins and free amino acids) are closely associated with volatile organic compounds (VOCs), and proteins and their breakdown products (e.g., free amino acids and sulfur-based compounds) are major contributors to mutton flavor and aroma [

43]. Our analysis revealed that fermented goji berry residue had the potential to increase the protein content of the LD muscles in fattened Tan sheep that could benefit the amino acid content and volatile compounds and improve the nutritional quality and flavor of Tan sheep muscles. Thus, we proceed to select LD on a full-scale analysis of the amino acids, flavor compounds, fatty acids, and volatile substances to further examine how fermented goji berry residue supplement affects the quality and flavor of Tan sheep meat.

From an industry perspective, these findings suggest that fermented Goji berry residue (FGB) could be developed as a functional feed ingredient for finishing Tan sheep, with the dual benefits of improving carcass/meat quality traits (e.g., reduced excessive fat deposition and improved visual appearance) and valorizing goji-processing by-products. In practical feeding systems, incorporating FGB at a fixed inclusion level (4% in the present study) may provide a feasible strategy to partially replace conventional concentrate ingredients and enhance value-added lamb production, while simultaneously reducing the environmental burden associated with the disposal of goji residues. Nevertheless, before large-scale adoption, further work is needed to evaluate production cost, fermentation scalability, batch-to-batch compositional consistency, and formulation compatibility under commercial conditions (including impacts on palatability, feed intake, and on-farm economics).

4.2. Impact of FGB on the Amino Acid Profiling of Longissimus Dorsi Muscle in Finishing-Phase Tan Sheep

In terms of free amino acids (FAAs), the FGB group exhibited overall higher concentrations, which are known to enhance meat flavor [

44]. Although the total content of free amino acids (FAAs) was elevated in the FGB group, the relative proportions of individual free amino acids showed no substantial differences when compared to the control (CON) group. Among the essential amino acids, lysine (Lys) remained the most abundant, whereas glutamic acid (Glu), aspartic acid (Asp), and arginine (Arg) continued to dominate the non-essential amino acid fraction, in agreement with previously reported observations [

45,

46]. FAAs serve as important flavor precursors in lamb, contributing to bitterness, sweetness, and umami taste [

47]. Glutamic acid (Glu), in particular, is recognized as a key umami compound and, along with other FAAs, is associated with salty and broth-like flavor attributes in meat [

48]. In the LDM,

GLUL expression was upregulated, and the gene was enriched in the “Alanine, aspartate, and glutamate metabolism” and “Glutamatergic synapse” pathways.

GLUL is crucial in various physiological and pathological processes. Variants of this gene have been associated with coronary artery disease (CAD) and type 2 diabetes, influencing glutamate metabolism [

49]. Thus, we can assume that the high levels of GLUL found in the FGB group lambs could be increasing glutamate production, but their exact contribution to glutamate production in the intramuscular lambs is subject to further research. It is important to note that aspartic acid (Asp) levels were much higher in the FGB group than in the CON group. Asp is reported to add umami taste, particularly when supplemented by sodium salts acting the same way as monosodium glutamate (MSG) [

50]. Tasting of amino acid bitter-tasting (Arg, His, Ile, Leu, Met, and Val) found no significant changes in overall content between treatment groups. Despite the overall similarity in the proportional distribution of individual free amino acids between the control (CON) and FGB groups, the FGB treatment led to substantially higher absolute concentrations of sweet-tasting amino acids, most notably glycine (Gly) and threonine (Thr). This elevation consequently produced a marked increase in the total concentration of sweet-contributing free amino acids (FAAs). KEGG pathway enrichment analysis further revealed that differentially expressed genes were significantly associated with the glycine, serine, and threonine metabolism pathway, suggesting enhanced metabolic flux through this route in the FGB-supplemented animals.

CTH had high levels of expression in the LDM, but

PHGDH was not expressed. Earlier studies show that both

PHGDH and

CTH play a role in the serine–glycine–one-carbon (SGOC) metabolism in macrophages, and both genes are upregulated together due to HIV infection to impair the amino acid metabolism [

51]. Moreover, PHGDH, the rate-limiting enzyme in serine production, is subject to the activity regulation by the acetylation changes triggered by serine starvation [

52]. Thus, fermented goji pomace is probably capable of modulating Gly, Ser, and Thr levels in Tan sheep

Longissimus dorsi through the control of the gene expression patterns of the major glycine–serine–threonine metabolic pathway.

The perceived sweetness can also be increased by the synergistic effect of the sweet amino acid and other flavor compounds, such as inosine monophosphate (IMP) [

53]. The FGB group showed much higher levels of sweet-tasting amino acids, as well as inosine monophosphate (IMP), compared to controls, which shows that the joint action of increased umami and sweet amino acids can be used to collectively influence the sensation of flavor. This enhancement probably leads to high sensory attributes and the quality of meat in general. Moreover, improving the protein deposition, in particular, the effectiveness of muscle protein accretion, is one of the major goals in animal husbandry [

54]. Past research indicates that amino acids like arginine (Arg), histidine (His), and serine (Ser) contribute to protein accumulation [

55,

56,

57], which is in line with our results about amino acid and protein content. On the basis of this evidence, we postulate that fermented goji pomace dietary supplementation could increase the levels of Arg, His, and Ser in the

Longissimus dorsi, leading to protein synthesis.

4.5. Impact of FGB on Volatile Flavor Compounds in Longissimus Dorsi Muscle of Finishing Tan Sheep

A total of 13 compounds were detected in both the FGB and CON groups: Carbon disulfide (sweet, pleasing, ethereal odor), 2-Butanone (acetone-like odor, sweet, pleasant, pungent), 1-Butanol (rancid, sweet, strong characteristic, mildly alcoholic odor), Decane (alkane), Acetone (fruity odor, characteristic odor, pungent, sweetish), Acetic acid (pungent, sour, vinegar-like odor, burning taste, sharp), Phenylacetaldehyde (bitter, clover, cocoa, floral, grapefruit, green, hawthorn, honey, hyacinth, peanut), Octane (gasoline-like, alkane), and compounds with unknown aroma characteristics (Benzene, 1,4-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-; Heptane, 4-methyl-; 2,4-Dimethyl-1-heptene; Hydroxylamine, O-(2-methylpropyl)-; 1,3,5-Cycloheptatriene). These compounds can be considered typical “Tan sheep meat flavor” compounds.

Volatile compound analysis revealed significantly elevated 1-Butanol and Carbon disulfide in FGB-supplemented meat (

p < 0.05), with acetic acid showing an increasing trend. Additionally, 16 unique flavor compounds were exclusively detected in the FGB group (

Table 8), collectively indicating substantial modification of Tan sheep meat’s sensory profile. While alcohol levels (notably 1-Butanol) were significantly elevated in FGB-supplemented meat—likely derived from lipid/protein degradation [

71]—their high odor thresholds limit aromatic contributions. Such changes in composition can contribute to flavor mildly, without adding much to aroma. Aldehydes and other compounds that produce meat flavor are primarily products of fat oxidation and degradation. Aldehydes are characterized by low odor thresholds and are reputed to cause greasy and off-flavors in meat [

72]. A majority of straight-chain aldehydes have an unpleasant smell, mainly because of the oxidation of unsaturated fatty acids. At low aldehyde concentrations, their typical odors, especially unsaturated aldehyde, may come out, which is relevant to taste. FGB supplementation lowered total aldehydes significantly compared to CON (

p < 0.05) and also significantly decreased phenylacetaldehyde, a Strecker aldehyde of methionine/phenylalanine degradation related to beer spoilage [

73] and beer off-flavors [

74]. This is a likely minimization of off-flavor possibilities in

Longissimus dorsi.

Proteins play a key role in binding flavor compounds as an essential matrix, due to the flavor being one of the vital sensory attributes [

54]. This paper demonstrates that when fermented goji berry pomace is added to the diet, the relative levels of the aldehydes decreased. This could be due to an augmentation of the muscle proteins, which eventually affected the liberation of aldehydes [

75,

76]. Nonetheless, the mediating mechanism of the muscle protein flavor is yet to be explored.

Hydrocarbons are the primary VOCs in the

Longissimus dorsi, with the highest relative content observed across all samples. These hydrocarbons primarily originate from the cleavage of fatty acid alkoxy radicals. The compounds detected in this study were mainly alkanes and terpenes, which have higher odor thresholds and only a minor direct impact on Tan sheep meat flavor. These compounds function as critical intermediates for flavor-enhancing heterocyclics, while key volatiles (acetic acid, butanoic acid, phenylacetaldehyde, and 3-methylbutanal) identified in Hungarian salami were also detected in our system. The relative content differences in these compounds due to the addition of fermented goji berry pomace may influence the flavor of Tan sheep meat [

77].

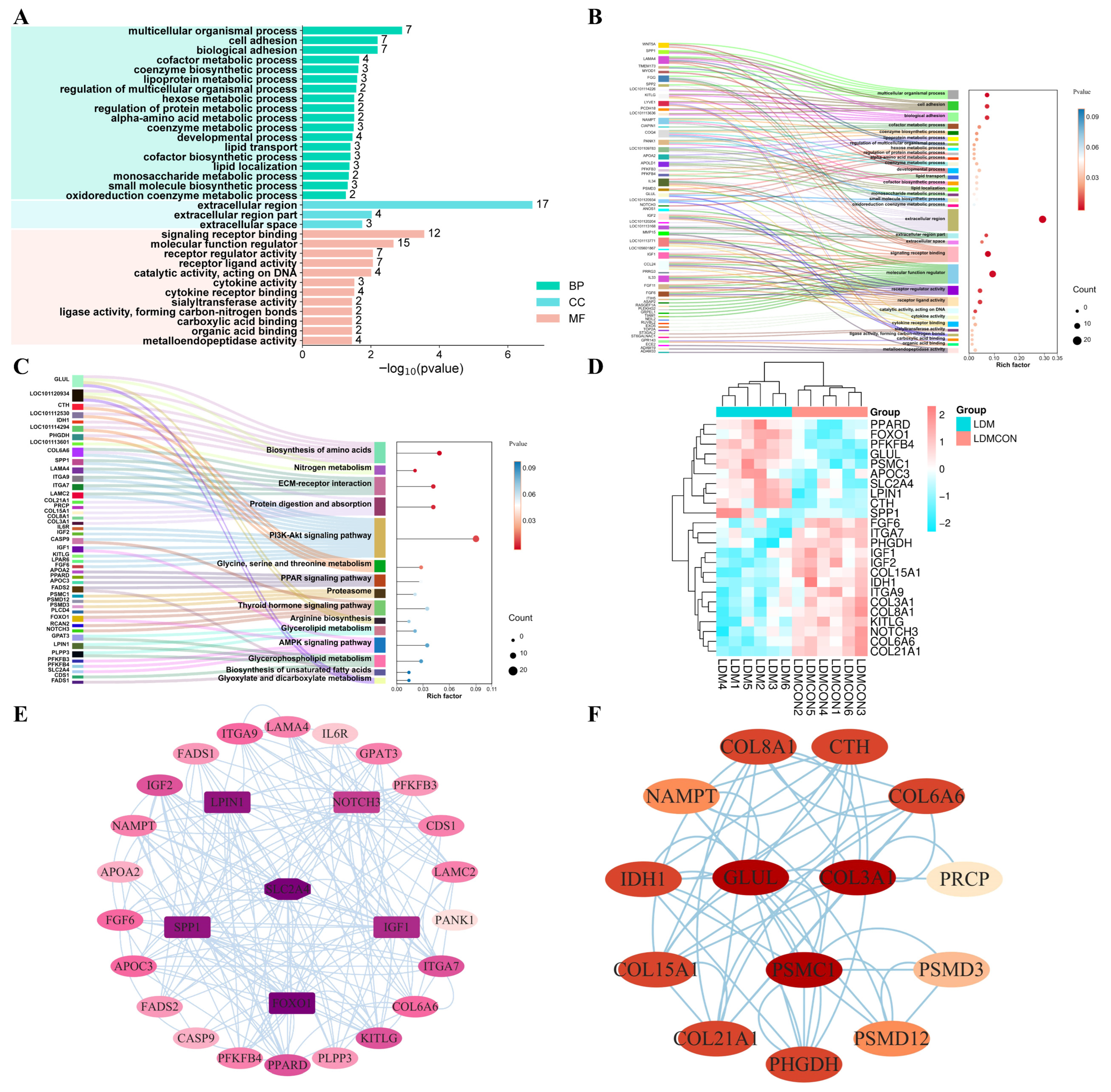

4.6. Integrated Metabolomic and Transcriptomic Analysis of FGB’s Mechanistic Impact on Amino Acid and Lipid Metabolism in Longissimus Dorsi Muscle of Finishing Tan Sheep

The mechanism by which nutritional factors are associated with lamb flavor through their impact on muscle metabolism may be related to gene regulation to some extent. Therefore, integrating transcriptomics and metabolomics analyses provides a powerful means to elucidate the regulatory mechanisms of meat quality formation in livestock and poultry [

78]. Our study reveals that fermented goji pomace modulates Tan sheep meat quality parameters by regulating amino acid and lipid metabolism pathways, thereby enhancing our understanding of molecular-level quality control mechanisms. KEGG enrichment analysis of metabolomic profiles between the LDM6 and LDMCON6 groups revealed significant overrepresentation of differential metabolites in pathways including butanoate metabolism, glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, PI3K-Akt signaling, HIF-1 signaling, alcoholic liver disease, pyruvate metabolism, and glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism (

Figure 2F,G). Taken together, the pathways of the enriched terms are mainly associated with amino acid metabolism and lipid metabolism, indicating that changes in the biochemical processes are major causes of the observed discrepancies in the

longissimus dorsi muscle quality and flavor in Tan sheep. Transcriptomic analyses of the LD revealed 382 DEGs between the LDM and LDMCON conditions, including 162 upregulated genes and 220 downregulated genes. GO and KEGG enrichment was further conducted on pathways and terms that are relevant to meat quality and flavor to select the most important genes involved in lipid and amino acid metabolism and visualize them in the form of Cytoscape. The degree value was used to rank the genes by their importance in the network, with the core genes shown in dark colors (

Figure 4E,F). The inclusion of genes like

FOXO1,

SLC2A4,

LPIN1,

IGF1,

SPP1,

COL3A1,

GLUL, and

PSMC1 in the middle of the PPI networks implies that they can have important roles in the regulation of the metabolic pathways involved in the determination of muscle quality and flavor.

Regarding lipid metabolism, in mammary epithelial cells,

FOXO1 controls the triglyceride production and lipid droplet generation by controlling the expression of lipid metabolism genes, including

CD36 and

STEAP4. In hepatocytes,

FOXO1 deficiency results in decreased expression of fatty acid oxidation-related genes, including

CPT1α and

ATGL, which exacerbates lipid accumulation [

79].

FOXO1 regulates lipogenesis via the AMPK and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways.

SLC2A4 (solute carrier family 2 member 4) has been shown to negatively regulate the deposition of lipids in pigs and sheep. Its expression can be increased, which stimulates the supply of energy to adipocytes due to the enhancement of the transport of glucose, which triggers lipogenesis [

80]. Furthermore,

SLC2A4 can be involved in fatty acid oxidation and energy metabolism in the thermogenic pathways of sheep, including other related genes like

ACSL1 and

CPT1A [

81]. In addition,

SLC2A4 has the potential to affect lipid homeostasis by regulating transmembrane fatty acid transport, possibly via miR-345-3p interaction. The role of its action is also linked to the insulin signaling pathway and the AMPK pathway, which is also a crucial element in fat deposition in sheep [

80,

82]. As an example, the decreased AMPK activity can mediate fat deposition in the growth of sheep by the

SLC2A4, and the fatty acid degradation and triglyceride metabolism may be mainly regulated by

FOXO1 and

SLC2A4, respectively [

83].

LPIN1 is particularly associated with triglyceride metabolism and fatty acid degradation. It has been established that the expression of

IGF1 is significantly enhanced in the fat tissue of obese individuals, including human and animal subjects. This increase is associated with increased lipogenic enzyme activity and is capable of promoting adipose deposition by the activation of the PI3K-AKT/AMPK signaling pathway [

16]. Thus, the feeding of fermented goji berry residues can have an impact on intramuscular fat levels and, consequently, on the nutritional and sensorial properties of Tan sheep meat through the regulation of the expression of critical genes (

FOXO1,

SLC2A4,

LPIN1,

IGF1).

Regarding the metabolism of the amino acids, COL3A1 (type III collagen) is of paramount importance to collagen synthesis, which is strongly connected to the requirement of certain amino acids, including proline and glycine. It has been found that PDHPS1 modulates the expression of

COL3A1, which affects the amino acid synthesis-related metabolic processes by inhibiting the

PKM2 (pyruvate kinase M2) expression and the Smad 2 phosphorylation. The modulation, in turn, affects the synthesis of glycolytic intermediates such as glucose and pyruvate [

84]. GLUL (glutamine synthetase) is an important enzyme that is vital in the glutamate–glutamine metabolism and the establishment of amino acid homeostasis. The studies have shown that

FOXO1 knockout could revert BaP-induced changes in glutamate–glutamine metabolism by increasing GLUL and SLC1A3, which emphasizes the repair role played by GLUL in amino acid metabolism [

85]. Moreover, it has been revealed that hepatic

GLUL mRNA expression among obese individuals positively correlates with the severity of MASLD and is accompanied by an increase in the levels of glutamate in the bloodstream, which indicates that

GLUL can also mediate the amino acid metabolism via the nitrogen metabolic imbalance [

86]. In another study, it was found that N-carbamylglutamate (NCG) supplementation had a significant effect on the ruminal fluid of sheep, mainly in glutamate- and nitrogen-related metabolites, suggesting that GLUL-related pathways could successfully be manipulated in sheep amino acid metabolism [

87]. In addition,

GLUL is a differentially expressed gene related to muscle growth in sheep, where its expression could be associated with the metabolic path of alanine, aspartate, and glutamate [

88].

PSMC1 (proteasome 26S subunit ATPase) is an integral component of the proteasome system, involved in protein degradation and amino acid recycling. Additionally, endurance exercise may impact amino acid metabolism by altering protein degradation, potentially involving proteasomal components like

PSMC1. Thus,

PSMC1 may indirectly influence the dynamic balance of the free amino acid pool by regulating the rate of protein degradation [

89]. In summary,

COL3A1 regulates the distribution of specific amino acids (e.g., glycine and proline) through collagen metabolic demand and coordinates with glycolysis–TCA cycle metabolism [

84,

90]. GLUL, as a rate-limiting enzyme in glutamine synthesis, modulates nitrogen metabolism and the glutamate/glutamine ratio, influencing amino acid homeostasis in the liver and muscle [

87,

91]. Meanwhile,

PSMC1 may regulate protein degradation via proteasomal activity, releasing free amino acids for metabolism or new protein synthesis [

89,

92]. Therefore, feeding fermented wolfberry pomace may influence muscle development and protein deposition in muscles by regulating the expression of key genes

(COL3A1,

GLUL,

PSMC1), thereby improving the nutritional and flavor quality of Tan sheep meat.

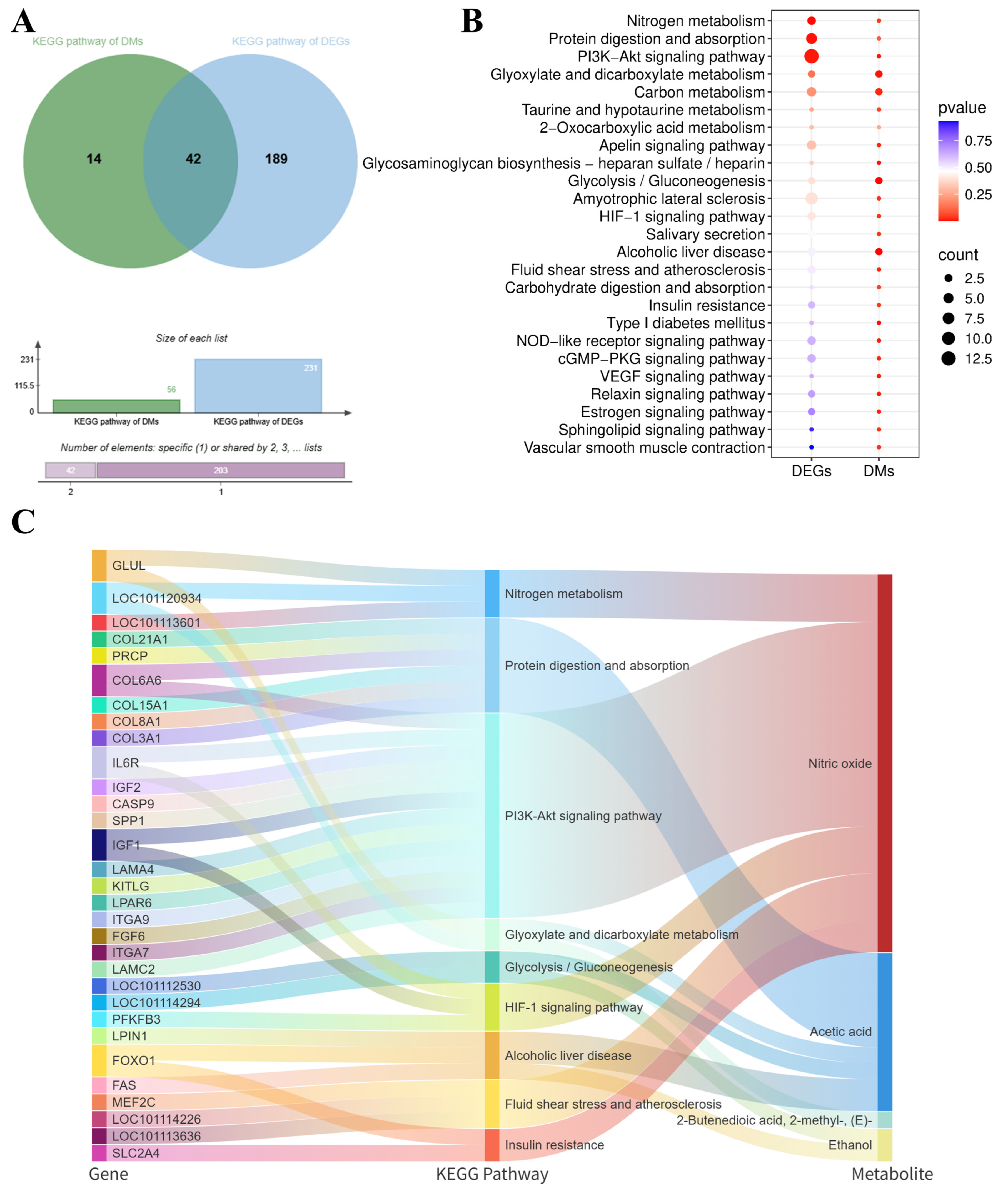

The integration of transcriptomic and metabolomic data provides a powerful approach for understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying lamb meat quality attributes. Notably, the enriched KEGG pathways identified from differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and differentially accumulated metabolites (DMs) showed significant overlap. Specifically, 42 KEGG pathways were found to be concurrently enriched by both DEGs and DMs, as shown in

Figure 6A. To visualize the relationships between genes, KEGG pathways, and metabolites, we employed a Sankey diagram to illustrate the significantly enriched KEGG pathways (

Figure 6B). These nine key KEGG pathways involved a total of 31 differentially expressed genes, including

GLUL,

COL21A1,

COL6A6,

COL15A1,

COL8A1,

COL3A1,

IL6R,

IGF2,

SPP1,

IGF1,

ITGA7,

PFKFB3,

FOXO1,

FAS, and

SLC2A4, which are closely associated with important biological function metabolites such as nitric oxide, acetic acid, 2-butenedioic acid (2-methyl-, (E)-), and ethanol.

These genes are closely associated with several important biofunctional metabolites such as nitric oxide, acetic acid, 2-butenedioic acid (2-methyl-, (E)-), and ethanol. Based on these findings, our study reveals that fermented goji pomace likely enhances Tan lamb meat quality and flavor attributes by modulating amino acid and lipid metabolism pathways. Key metabolites involved include nitric oxide, acetic acid, (E)-2-methyl-2-butenedioic acid, and ethanol. Through functional enrichment and protein–protein interaction (PPI) network analyses, we identified critical regulatory genes strongly associated with flavor-related amino acids (COL3A1, GLUL, PSMC1) and lipid metabolism (FOXO1, SLC2A4, LPIN1, IGF1, SPP1).

Overall, our results support the potential of fermented Goji berry residue (FGB) as a value-added feed ingredient for finishing Tan sheep, linking improvements in meat nutritional traits and flavor-related indicators with coordinated changes in amino acid and lipid metabolism. From a practical standpoint, this strategy may provide a feasible route for the upcycling of goji-processing by-products in Ningxia, thereby reducing waste-disposal pressure while contributing to premium lamb production. For industry translation, key issues that warrant further evaluation include (i) cost-effectiveness relative to conventional ingredients (including fermentation, drying, and logistics), (ii) scalability and quality control of fermentation (batch-to-batch consistency of bioactive components and nutrient composition), (iii) formulation compatibility and on-farm performance across production systems (palatability, intake, growth, carcass grading, and health outcomes), and (iv) sensory validation in consumer panels to confirm whether the observed biochemical changes translate into perceivable improvements in eating quality. Addressing these points in future trials will help determine the most appropriate inclusion level, feeding duration, and processing specifications for commercial application.