Multi-Analytical Insight into the Non-Volatile Phytochemical Composition of Coleus aromaticus (Roxb.) Benth.

Abstract

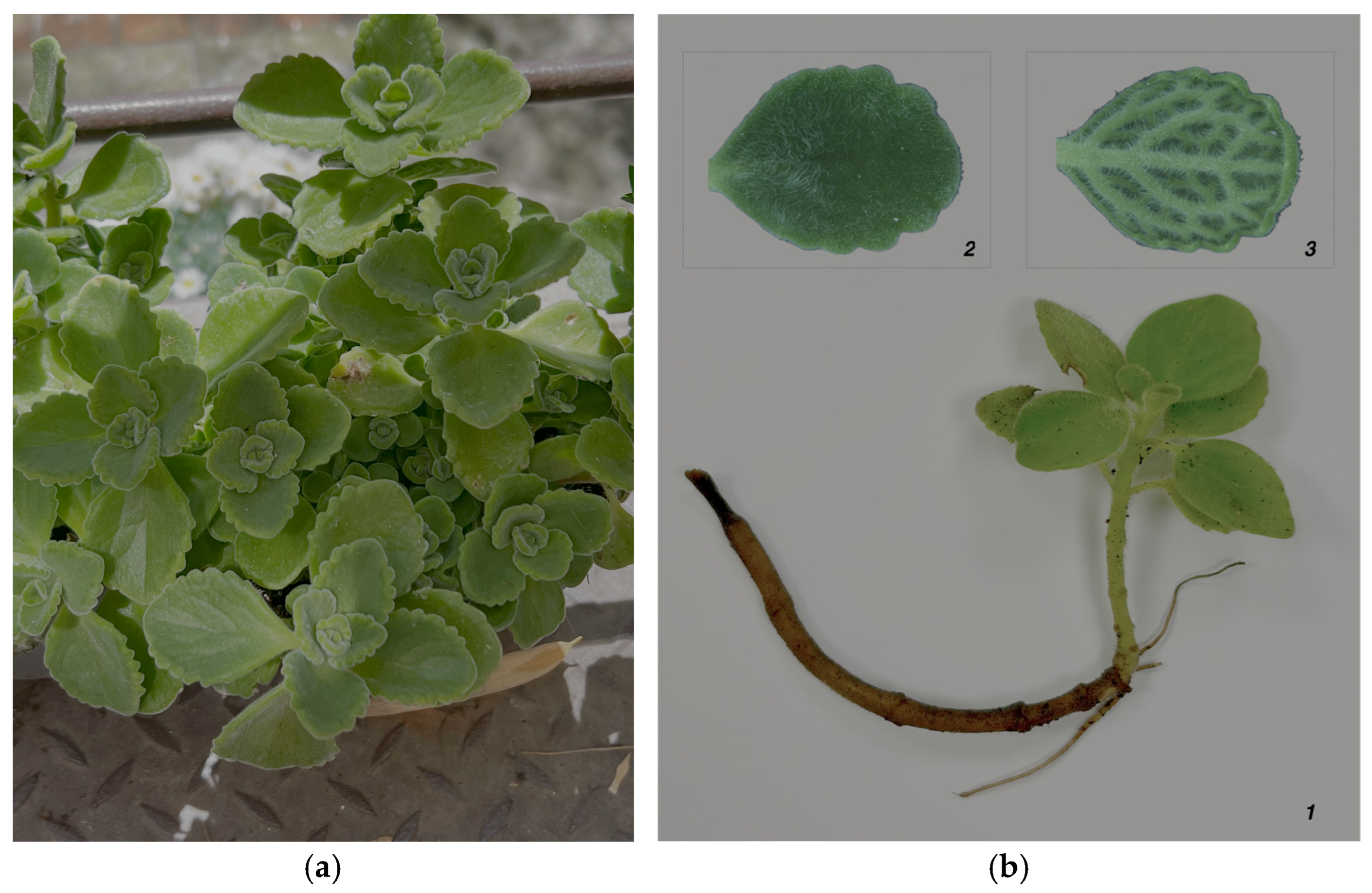

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

2.2. Samples Collection and Extract Preparation

2.3. HPTLC Analysis

2.4. HPLC Analysis

2.5. NMR Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Amino Acids Analysis

3.2. Organic Acids and Phenols

4. Discussion

4.1. Amino Acids Analysis

4.2. Organic Acids and Phenols

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Rf | Retention factor |

| Rt | Retention time |

| HPLC | High pressure liquid chromatography |

| HPTLC | High-performance thin-layer chromatography |

| NMR | Nuclear magnetic resonance |

| BDE | Bligh–Dyer extracts |

| HAM | Hydroalcoholic macerate |

| EAM | Ethyl acetate macerate |

| OP | Organic phase |

| HAP | Hydroalcoholic phase |

| Ala | Alanine |

| Arg | Arginine |

| Asn | Asparagine |

| Asp | Aspartic acid |

| Cys | Cysteine |

| Glu | Glutamic Acid |

| Gly | Glycine |

| His | Histidine |

| Ile | Isoleucine |

| Leu | Leucine |

| Lys | Lysine |

| Met | Methionine |

| Phe | Phenylalanine |

| Pro | Proline |

| Ser | Serine |

| Thr | Threonine |

| Trp | Tryptophan |

| Tyr | Tyrosine |

| Val | Valine |

| TSP | 3-(trimethylsilyl)-propionic-2,2,3,3-d4 acid sodium salt |

| HMS | Hexamethyldisiloxane |

References

- WFO—The World Flora Online Plectranthus amboinicus (Lour.) Spreng. Available online: https://www.worldfloraonline.org/taxon/wfo-0000275221 (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Paton, A.J.; Mwanyambo, M.; Govaerts, R.H.A.; Smitha, K.; Suddee, S.; Phillipson, P.B.; Wilson, T.C.; Forster, P.I.; Culham, A. Nomenclatural Changes in Coleus and Plectranthus (Lamiaceae): A Tale of More than Two Genera. PhytoKeys 2019, 129, 1–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rout, O.P.; Acharya, R.; Mishra, S.K.; Sahoo, R. Pathorchur (Coleus aromaticus): A Review of the Medicinal Evidence for Its Phytochemistry and Pharmacology Properties. Int. J. Appl. Biol. Pharm. Technol. 2012, 3, 348–355. [Google Scholar]

- Wadikar, D.D.; Patki, P.E. Coleus aromaticus: A Therapeutic Herb with Multiple Potentials. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 53, 2895–2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, P.; Joseph, G.S.; Negi, P.S.; Varadaraj, M.C. Chemical Composition and Nutraceutical Potential of Indian Borage (Plectranthus amboinicus) Stem Extract. J. Chem. 2013, 2013, 320329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khare, R.S.; Banerjee, S.; Kundu, K. Coleus aromaticus Benth—A Nutritive Medicinal Plant of Potential Therapeutic Value. Int. J. Pharma Bio. Sci. 2011, 2, 488–500. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt, P.; Negi, P.S. Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activities in the Leaf Extracts of Indian Borage (Plectranthus amboinicus). Food Nutr. Sci. 2012, 03, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaran, A.; Joel Karunakaran, R. Antioxidant and Free Radical Scavenging Activity of an Aqueous Extract of Coleus aromaticus. Food Chem. 2006, 97, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, T.Z.; Kao, C.L.; Hsieh, Y.L.; Li, H.T.; Chen, C.Y. Chemical Constituents of the Leaves of Plectranthus amboinicus. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2019, 55, 124–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, B.S.S.; Shanbhoge, R.; Upadhya, D.; Jagetia, G.; Kumar, P.; Guruprasad, K.; Gayathri, P. Antioxidant, Anticlastogenic and Radioprotective Effect of Coleus aromaticus on Chinese Hamster Fibroblast Cells (V79) Exposed to Gamma Radiation. Mutagenesis 2006, 21, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Singh, O.P.; Prasad, Y.R.; De Lampasona, M.P.; Catalan, C. Studies on Essential Oils, Part 33: Chemical and Insecticidal Investigations on Leaf Oil of Coleus amboinicus Lour. Flavour Fragr. J. 2002, 17, 440–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathiresan, R.M. Effect of Manuring, Drying Methods and Soaking Time on the Allelopathic Potential of Coleus amboinicus/aromaticus on Eichhornia crassipes. Res. J. Agric. Biol. Sci. 2007, 3, 723–726. [Google Scholar]

- El-Hawary, S.S.; El-sofany, R.H.; Abdel-Monem, A.R.; Ashour, R.S. Phytochemical Screening, DNA Fingerprinting, and Nutritional Value of Plectranthus amboinicus (Lour.) Spreng. Pharmacogn. J. 2012, 4, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewari, G.; Pande, C.; Kharkwal, G.; Singh, S.; Singh, C. Phytochemical Study of Essential Oil from the Aerial Parts of Coleus aromaticus Benth. Nat. Prod. Res. 2012, 26, 182–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toniolo, C.; Patriarca, A.; De Vita, D.; Santi, L.; Sciubba, F. A Comparative Multianalytical Approach to the Characterization of Different Grades of Matcha Tea (Camellia sinensis (L.) Kuntze). Plants 2025, 14, 1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampaoli, O.; Sciubba, F.; Conta, G.; Capuani, G.; Tomassini, A.; Giorgi, G.; Brasili, E.; Aureli, W.; Miccheli, A. Red Beetroot’s NMR-Based Metabolomics: Phytochemical Profile Related to Development Time and Production Year. Foods 2021, 10, 1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reich, E.; Schibli, A.; Widmer, V.; Jorns, R.; Wolfram, E.; DeBatt, A. HPTLC Methods for Identification of Green Tea and Green Tea Extract. J. Liq. Chromatogr. Relat. Technol. 2006, 29, 2141–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciubba, F.; Tomassini, A.; Giorgi, G.; Brasili, E.; Pasqua, G.; Capuani, G.; Aureli, W.; Miccheli, A. NMR-Based Metabolomic Study of Purple Carrot Optimal Harvest Time for Utilization as a Source of Bioactive Compounds. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, V.; Brasili, E.; Sciubba, F.; Ceci, A.; Giampaoli, O.; Miccheli, A.; Pasqua, G.; Persiani, A.M. Biostimulant Effects of Chaetomium globosum and Minimedusa polyspora Culture Filtrates on Cichorium Intybus Plant: Growth Performance and Metabolomic Traits. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 879076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wishart, D.S.; Sajed, T.; Pin, M.; Poynton, E.F.; Goel, B.; Lee, B.L.; Guo, A.C.; Saha, S.; Sayeeda, Z.; Han, S.; et al. The Natural Products Magnetic Resonance Database (NP-MRD) for 2025. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D700–D708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskaran, K.; Craft, D.L.; Eghbalnia, H.R.; Gryk, M.R.; Hoch, J.C.; Maciejewski, M.W.; Schuyler, A.D.; Wedell, J.R.; Wilburn, C.W. Merging NMR Data and Computation Facilitates Data-Centered Research. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 8, 817175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaeli, S.; Fromm, H. Closing the Loop on the GABA Shunt in Plants: Are GABA Metabolism and Signaling Entwined? Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Dou, N.; Zhang, H.; Wu, C. The Versatile GABA in Plants. Plant Signal. Behav. 2021, 16, 1862565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sita, K.; Kumar, V. Role of Gamma Amino Butyric Acid (GABA) against Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Legumes: A Review. Plant Physiol. Rep. 2020, 25, 654–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.I.R.; Jalil, S.U.; Chopra, P.; Chhillar, H.; Ferrante, A.; Khan, N.A.; Ansari, M.I. Role of GABA in Plant Growth, Development and Senescence. Plant Gene 2021, 26, 100283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, S.A.; Tyerman, S.D.; Xu, B.; Bose, J.; Kaur, S.; Conn, V.; Domingos, P.; Ullah, S.; Wege, S.; Shabala, S.; et al. GABA Signalling Modulates Plant Growth by Directly Regulating the Activity of Plant-Specific Anion Transporters. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arumugam, G.; Swamy, M.; Sinniah, U. Plectranthus amboinicus (Lour.) Spreng: Botanical, Phytochemical, Pharmacological and Nutritional Significance. Molecules 2016, 21, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellinger, J.; Kim, H.; Ralph, J.; Karlen, S.D. P-Coumaroylation of Lignin Occurs Outside of Commelinid Monocots in the Eudicot Genus Morus (Mulberry). Plant Physiol. 2023, 191, 854–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkomo, M.; Gokul, A.; Keyster, M.; Klein, A. Exogenous P-Coumaric Acid Improves Salvia hispanica L. Seedling Shoot Growth. Plants 2019, 8, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkomo, M.; Badiwe, M.; Niekerk, L.-A.; Gokul, A.; Keyster, M.; Klein, A. P-Coumaric Acid Differential Alters the Ion-Omics Profile of Chia Shoots under Salt Stress. Plants 2024, 13, 1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, M.; Wang, X.; Zhu, X.; Du, Y.; Zhou, P.; Wang, G.; Wang, N.; Bai, Y. Accumulation of Coumaric Acid Is a Key Factor in Tobacco Continuous Cropping Obstacles. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1477324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimmy, J.L. Coleus aromaticus Benth.: An Update on Its Bioactive Constituents and Medicinal Properties. All Life 2021, 14, 756–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitl, M.; Kladar, N.; Gavarić, N.; Božin, B. Rosmarinic Acid–Human Pharmacokinetics and Health Benefits. Planta Med. 2021, 87, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noor, S.; Mohammad, T.; Rub, M.A.; Raza, A.; Azum, N.; Yadav, D.K.; Hassan, M.I.; Asiri, A.M. Biomedical Features and Therapeutic Potential of Rosmarinic Acid. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 2022, 45, 205–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, A.; Tuberoso, C.I.G.; Jerković, I. The Role of Rosmarinic Acid in Cancer Prevention and Therapy: Mechanisms of Antioxidant and Anticancer Activity. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Method | Fresh Leaves | Solvents | Agitation | T/t |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bligh–Dyer (BD) | 1.2 g | 3 mL MeOH + 3 mL CHCl3 (vortex), then 1.5 mL water | Vortex 30 s; static overnight | 4 °C/12 h |

| Hydroalcoholic maceration (HAM) | 6 g | MeOH:H2O = 7:3 30 mL | Rotary shaker, 150 rpm | 25 °C/24 h |

| Ethyl acetate Maceration (EAM) | 6 g | Ethyl acetate 30 mL | Rotary shaker, 150 rpm | 25 °C/24 h |

| MeOH/DCM/H2O partitioning (HAP + OP) | 6 g | 30 mL MeOH, 30 mL DCM, 15 mL H2O | Rotary shaker, 150 rpm | 25 °C/24 h |

| Compound | Amount (mg/100 g) |

|---|---|

| Amino Acids | |

| Alanine | 0.56 ± 0.08 |

| Asparagine | 7.51 ± 4.65 |

| γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) | 1.73 ± 0.77 |

| Glutamic acid | 2.92 ± 0.58 |

| Glutamine | 0.46 ± 0.19 |

| Threonine | 0.16 ± 0.05 |

| Flavonoid | EAM | OP | HAP | HAM | Rf |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apigenin | + | + | - | - | 0.89 |

| Luteolin | - | + | - | - | 0.83 |

| Quercetin | + | + | - | - | 0.86 |

| Rutin | - | - | X * | X * | 0.15 |

| Organic Acid | EAM | OP | HAP | HAM | Rf |

| Caffeic acid | +++ | - | + | + | 0.83 |

| Chlorogenic acid | - | - | - | - | 0.27 |

| Gallic acid | - | - | - | - | 0.75 |

| p-cumaric acid | - | - | - | - | 0.86 |

| Rosmarinic acid | - | - | ++ | + | 0.75 |

| Compound | Amount (mg/100 g) |

|---|---|

| Organic Acids | |

| Acetic Acid | 0.19 ± 0.03 |

| Caffeic Acid | 49.66 ± 2.65 |

| Formic Acid | 0.28 ± 0.11 |

| Fumaric Acid | 0.61 ± 0.05 |

| Malic Acid | 68 ± 19.5 |

| Rosmarinic Acid | 88.89 ± 14.09 |

| Flavonoids | |

| U01 (Apigenin glycoside 1) | 6.16 ± 0.51 |

| U02 (Apigenin glycoside 2) | 5.49 ± 0.33 |

| Compound | Amount (mg/100 g) |

|---|---|

| Carbohydrates | |

| Fructose | 22.56 ± 4.71 |

| Glucose | 2.62 ± 0.19 |

| Raffinose | 14.73 ± 0.93 |

| Sucrose | 6.79 ± 1.03 |

| Lipids and Sterols | |

| β-Sitosterol | 0.97 ± 0.51 |

| Campsterol | 1.57 ± 0.25 |

| Monounsaturated ω-9 fatty acid (ω-9 FA) | 33.03 ± 5.71 |

| Polyunsaturated ω-6 fatty acid (ω-6 FA) | 0.97 ± 0.22 |

| Polyunsaturated ω-3 fatty acid (ω-3 FA) | 6.87 ± 1.68 |

| Saturated fatty acid (SFA) | 141.11 ± 17.54 |

| Other Metabolites | |

| Choline | 1.79 ± 0.37 |

| Unknown Compounds | |

| U03 (2-Hydroxy-3-methylbutyric acid) | 2.73 ± 0.97 |

| U04 (Octenoic acid) | 1.56 ± 0.25 |

| U05 (Marlignan R) | 27.08 ± 4.59 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Toniolo, C.; Bortolami, M.; Patriarca, A.; De Vita, D.; Sciubba, F.; Santi, L. Multi-Analytical Insight into the Non-Volatile Phytochemical Composition of Coleus aromaticus (Roxb.) Benth. Metabolites 2026, 16, 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010015

Toniolo C, Bortolami M, Patriarca A, De Vita D, Sciubba F, Santi L. Multi-Analytical Insight into the Non-Volatile Phytochemical Composition of Coleus aromaticus (Roxb.) Benth. Metabolites. 2026; 16(1):15. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010015

Chicago/Turabian StyleToniolo, Chiara, Martina Bortolami, Adriano Patriarca, Daniela De Vita, Fabio Sciubba, and Luca Santi. 2026. "Multi-Analytical Insight into the Non-Volatile Phytochemical Composition of Coleus aromaticus (Roxb.) Benth." Metabolites 16, no. 1: 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010015

APA StyleToniolo, C., Bortolami, M., Patriarca, A., De Vita, D., Sciubba, F., & Santi, L. (2026). Multi-Analytical Insight into the Non-Volatile Phytochemical Composition of Coleus aromaticus (Roxb.) Benth. Metabolites, 16(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010015