Profiling Serum Oxylipin Metabolites Across Melanoma Subtypes and Immunotherapy Responders

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Oxylipin Quantification by UHPLC-MS

2.3. Experimental Data and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Clinical Characteristics

3.2. Mass Spectrometry Evaluation of Oxylipin Levels in Patient Serum

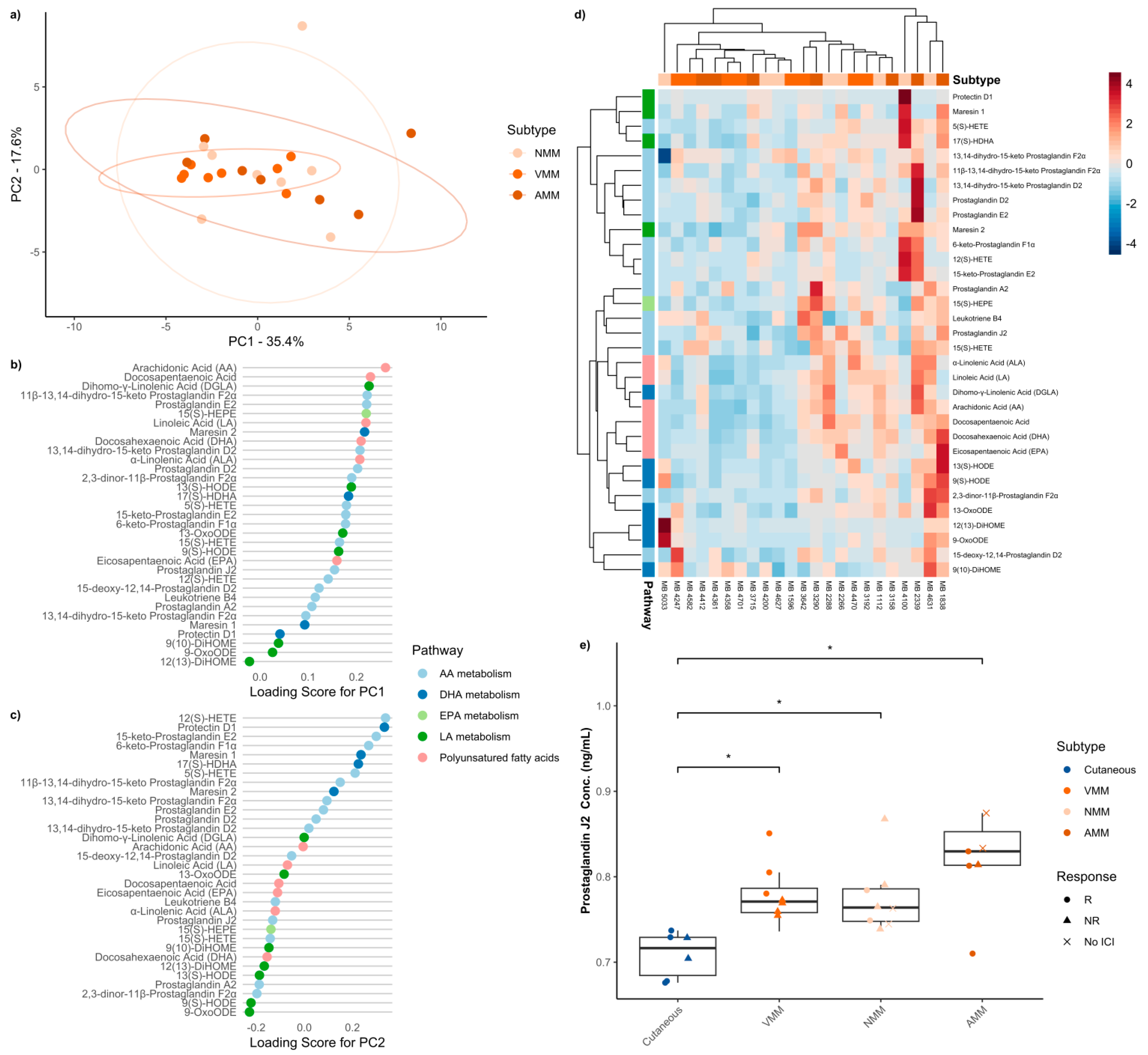

3.3. Baseline Serum Oxylipins Across Melanoma Subtypes

3.4. Baseline Serum Oxylipins Across Mucosal Melanoma Anatomic Locations

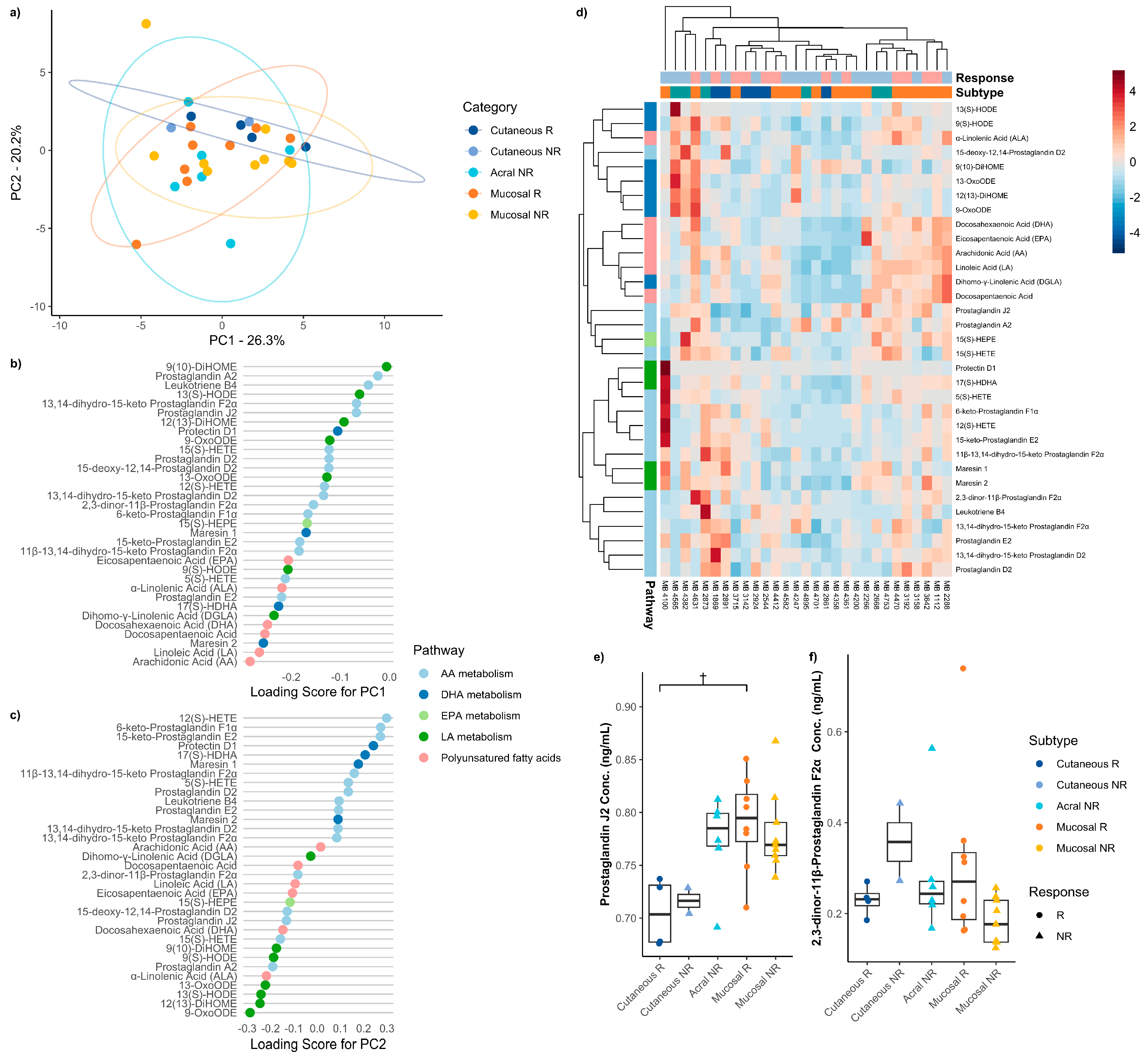

3.5. Baseline Serum Oxylipins Between Immune Checkpoint Therapy Responders and Non-Responders Across Melanoma Subtypes

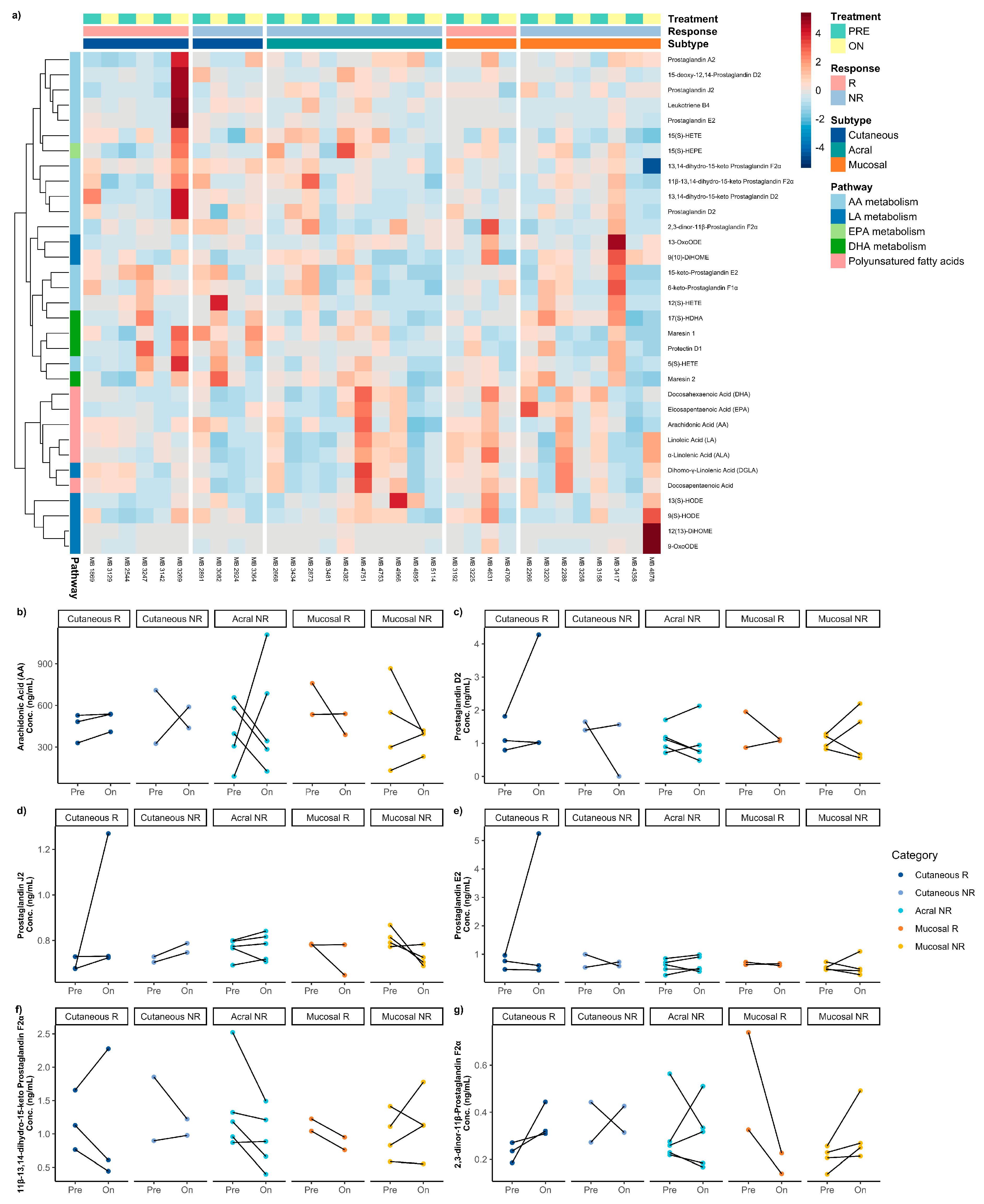

3.6. Difference Between Pre-Treatment and on-/Post-Treatment Oxylipins Across Melanoma Subtypes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AA | arachidonic acid |

| ACN | acetonitrile |

| AM | acral melanoma |

| CD8+ | CD8-positive T cells |

| CM | cutaneous melanoma |

| COX | cyclooxygenases |

| COX-2 | cyclooxygenase 2 |

| CR | complete response |

| CTLA-4 | cytotoxic T lymphocyte 4 |

| CYP | cytochrome P450 enzymes |

| DGLA | dihomo-gamma-linolenic acid |

| DHA | docosahexaenoic acid |

| EP4 | prostaglandin E2 receptor 4 |

| EPA | eicosapentaenoic acid |

| HDoHE | hydroxydocosahexaenoic acids |

| HEPE | hydroxyeicosapentaenoic acids |

| HETE | hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids |

| ICI | immune checkpoint inhibitor |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| LA | linoleic acid |

| LDH | lactate dehydrogenase |

| LOX | lipoxygenases |

| LT | leukotrienes |

| MeOH | methanol |

| MM | mucosal melanoma |

| NR | non-responders |

| PC | principal component |

| PCA | principal component analysis |

| PD | progressive disease |

| PD-1 | programmed death 1 |

| PG | prostaglandins |

| PGE2 | prostaglandin E2 |

| PGJ2 | prostaglandin J2 |

| 15d-PGJ2 | 15-deoxy-Δ12,14 prostaglandin J2 |

| PPARγ | peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma |

| PR | partial response |

| PUFA | polyunsaturated fatty acids |

| R | responders |

| RCF | relative centrifugal force |

| RECIST | response evaluation criteria in solid tumors |

| RvD1 | resolvin D1 |

| SID | stable isotope dilution |

| SD | stable disease/standard deviation |

| TMB | tumor mutational burden |

| TX | thromboxanes |

| UHPLC-MS | ultra high-pressure liquid chromatography mass spectrometry |

| UM | uveal melanoma |

References

- Gabbs, M.; Leng, S.; Devassy, J.G.; Monirujjaman, M.; Aukema, H.M. Advances in Our Understanding of Oxylipins Derived from Dietary PUFAs. Adv. Nutr. 2015, 6, 513–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serhan, C.N. Pro-resolving lipid mediators are leads for resolution physiology. Nature 2014, 510, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venza, I.; Visalli, M.; Oteri, R.; Beninati, C.; Teti, D.; Venza, M. Genistein reduces proliferation of EP3-expressing melanoma cells through inhibition of PGE2-induced IL-8 expression. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2018, 62, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellerin, L.; Carrié, L.; Dufau, C.; Nieto, L.; Ségui, B.; Levade, T.; Riond, J.; Andrieu-Abadie, N. Lipid metabolic Reprogramming: Role in Melanoma Progression and Therapeutic Perspectives. Cancers 2020, 12, 3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-H.; Roszik, J.; Cho, S.-N.; Ogata, D.; Milton, D.R.; Peng, W.; Menter, D.G.; Ekmekcioglu, S.; Grimm, E.A. The COX2 Effector Microsomal PGE2 Synthase 1 is a Regulator of Immunosuppression in Cutaneous Melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 1650–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, W.; Sampath, P.; Rojas, J.J.; Thorne, S.H. Oncolytic Virus-Mediated Targeting of PGE2 in the Tumor Alters the Immune Status and Sensitizes Established and Resistant Tumors to Immunotherapy. Cancer Cell 2016, 30, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albu, D.I.; Wang, Z.; Huang, K.-C.; Wu, J.; Twine, N.; Leacu, S.; Ingersoll, C.; Parent, L.; Lee, W.; Liu, D.; et al. EP4 Antagonism by E7046 diminishes Myeloid immunosuppression and synergizes with Treg-reducing IL-2-Diphtheria toxin fusion protein in restoring anti-tumor immunity. Oncoimmunology 2017, 6, e1338239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.Y.; McQuade, J.L.; Rai, R.R.; Park, J.J.; Zhao, S.; Ye, F.; Beckermann, K.E.; Rubinstein, S.M.; Johnpulle, R.; Long, G.V.; et al. The Impact of Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs, Beta Blockers, and Metformin on the Efficacy of Anti-PD-1 Therapy in Advanced Melanoma. Oncologist 2020, 25, e602–e605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triozzi, P.L.; Stirling, E.R.; Song, Q.; Westwood, B.; Kooshki, M.; Forbes, M.E.; Holbrook, B.C.; Cook, K.L.; Alexander-Miller, M.A.; Miller, L.D.; et al. Circulating Immune Bioenergetic, Metabolic, and Genetic Signatures Predict Melanoma Patients’ Response to Anti–PD-1 Immune Checkpoint Blockade. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 28, 1192–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da-Costa-Rocha, I.; Prieto, J.M. In Vitro Effects of Selective COX and LOX Inhibitors and Their Combinations with Antineoplastic Drugs in the Mouse Melanoma Cell Line B16F10. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruglov, O.; Vats, K.; Soman, V.; Tyurin, V.A.; Tyurina, Y.Y.; Wang, J.; Williams, L.; Zhang, J.; Carey, C.D.; Jaklitsch, E.; et al. Melanoma-associated repair-like Schwann cells suppress anti-tumor T-cells via 12/15-LOX/COX2-associated eicosanoid production. Oncoimmunology 2023, 12, 2192098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilbert, M.; Koch, E.C.; Rose, A.A.N.; Laister, R.C.; Gray, D.; Sotov, V.; Penny, S.; Spreafico, A.; Pinto, D.M.; Butler, M.O.; et al. Analysis of the Circulating Metabolome of Patients with Cutaneous, Mucosal and Uveal Melanoma Reveals Distinct Metabolic Profiles with Implications for Response to Immunotherapy. Cancers 2023, 15, 3708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoushtari, A.N.; Munhoz, R.R.; Kuk, D.; Ott, P.A.; Johnson, D.B.; Tsai, K.K.; Rapisuwon, S.; Eroglu, Z.; Sullivan, R.J.; Luke, J.J.; et al. The efficacy of anti-PD-1 agents in acral and mucosal melanoma. Cancer 2016, 122, 3354–3362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, S.P.; Larkin, J.; Sosman, J.A.; Lebbé, C.; Brady, B.; Neyns, B.; Schmidt, H.; Hassel, J.C.; Hodi, F.S.; Lorigan, P.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Nivolumab Alone or in Combination with Ipilimumab in Patients with Mucosal Melanoma: A Pooled Analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.; Couts, K.; Sheren, J.; Saichaemchan, S.; Ariyawutyakorn, W.; Avolio, I.; Cabral, E.; Glogowska, M.; Amato, C.; Robinson, S.; et al. Kinase gene fusions in defined subsets of melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2017, 30, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsoi, J.; Robert, L.; Paraiso, K.; Galvan, C.; Sheu, K.M.; Lay, J.; Wong, D.J.; Atefi, M.; Shirazi, R.; Wang, X.; et al. Multi-stage Differentiation Defines Melanoma Subtypes with Differential Vulnerability to Drug-Induced Iron-Dependent Oxidative Stress. Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 890–904.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benboubker, V.; Boivin, F.; Dalle, S.; Caramel, J. Cancer Cell Phenotype Plasticity as a Driver of Immune Escape in Melanoma. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 873116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Bruyn, D.P.; Bongaerts, M.; Bonte, R.; Vaarwater, J.; Meester-Smoor, M.A.; Verdijk, R.M.; Paridaens, D.; Naus, N.C.; de Klein, A.; Ruijter, G.J.G.; et al. Uveal Melanoma Patients Have a Distinct Metabolic Phenotype in Peripheral Blood. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenhauer, E.A.; Therasse, P.; Bogaerts, J.; Schwartz, L.H.; Sargent, D.; Ford, R.; Dancey, J.; Arbuck, S.; Gwyther, S.; Mooney, M.; et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur. J. Cancer 2009, 45, 228–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisz, J.A.; Zheng, C.; D’Alessandro, A.; Nemkov, T. Untargeted and Semi-targeted Lipid Analysis of Biological Samples Using Mass Spectrometry-Based Metabolomics. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019, 1978, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemkov, T.; Hansen, K.C.; D’Alessandro, A. A three-minute method for high-throughput quantitative metabolomics and quantitative tracing experiments of central carbon and nitrogen pathways. Rapid Commun. Mass. Spectrom. 2017, 31, 663–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulitschke, V.; Gruber, S.; Hofstätter, E.; Haudek-Prinz, V.; Klepeisz, P.; Schicher, N.; Jonak, C.; Petzelbauer, P.; Pehamberger, H.; Gerner, C.; et al. Proteome Analysis Identified the PPARγ Ligand 15d-PGJ2 as a Novel Drug Inhibiting Melanoma Progression and Interfering with Tumor-Stroma Interaction. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e46103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bregman, M.D.; Funk, C.; Fukushima, M. Inhibition of human melanoma growth by prostaglandin A, D, and J analogues. Cancer Res. 1986, 46, 2740–2744. [Google Scholar]

- Jara-Gutiérrez, Á.; Baladrón, V. The Role of Prostaglandins in Different Types of Cancer. Cells 2021, 10, 1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, K.; Omori, K.; Murata, T. Role of prostaglandins in tumor microenvironment. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2018, 37, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, D.D.; Thapa, M.; Aminzadeh-Gohari, S.; Redtenbacher, A.-S.; Catalano, L.; Feichtinger, R.G.; Koelblinger, P.; Dallmann, G.; Emberger, M.; Kofler, B.; et al. Targeted Metabolomics Identifies Plasma Biomarkers in Mice with Metabolically Heterogeneous Melanoma Xenografts. Cancers 2021, 13, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cutaneous (n = 6) | Acral (n = 7) | Mucosal (n = 23) | Uveal (n = 7) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasopharyngeal (n = 8) | Vulvovaginal (n = 8) | Anorectal (n = 7) | ||||

| Gender, No. (%) | ||||||

| Female | 3 (50.0) | 3 (42.9) | 5 (62.5) | 8 (100) | 3 (42.9) | 4 (57.1) |

| Male | 3 (50.0) | 4 (57.1) | 3 (37.5) | 0 (0) | 4 (57.1) | 3 (42.9) |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 72 ± 9 | 60 ± 11 | 70 ± 15 | 57 ± 16 | 62 ± 10 | 57 ± 9 |

| Range | (64–84) | (39–70) | (47–92) | (39–91) | (47–80) | (40–66) |

| ICI, No. (%) | ||||||

| None | 0 (0) | 1 (14.3) | 2 (25.0) | 1 (12.5) | 3 (42.9) | 4 (57.1) |

| Anti-PD-1 | 3 (50.0) | 4 (57.1) | 5 (62.5) | 4 (50.0) | 2 (28.6) | 1 (14.3) |

| Combination | 3 (50.0) | 2 (28.6) | 1 (12.5) | 3 (37.5) | 2 (28.6) | 2 (28.6) |

| Response, No. (%) | ||||||

| No ICI | 0 (0) | 1 (14.3) | 2 (25.0) | 1 (12.5) | 3 (42.9) | 4 (57.1) |

| Non-responder | 2 (33.3) | 6 (85.7) | 4 (50.0) | 4 (50.0) | 1 (14.3) | 0 (0) |

| Responder | 4 (66.7) | 0 (0) | 2 (25.0) | 3 (37.5) | 3 (42.9) | 3 (42.9) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Goodman, A.C.; Michel, K.M.; MacBeth, M.L.; Turner, J.A.; Tobin, R.P.; Robinson, W.A.; Couts, K.L. Profiling Serum Oxylipin Metabolites Across Melanoma Subtypes and Immunotherapy Responders. Metabolites 2026, 16, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010014

Goodman AC, Michel KM, MacBeth ML, Turner JA, Tobin RP, Robinson WA, Couts KL. Profiling Serum Oxylipin Metabolites Across Melanoma Subtypes and Immunotherapy Responders. Metabolites. 2026; 16(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleGoodman, Alexander C., Kylie M. Michel, Morgan L. MacBeth, Jaqueline A. Turner, Richard P. Tobin, William A. Robinson, and Kasey L. Couts. 2026. "Profiling Serum Oxylipin Metabolites Across Melanoma Subtypes and Immunotherapy Responders" Metabolites 16, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010014

APA StyleGoodman, A. C., Michel, K. M., MacBeth, M. L., Turner, J. A., Tobin, R. P., Robinson, W. A., & Couts, K. L. (2026). Profiling Serum Oxylipin Metabolites Across Melanoma Subtypes and Immunotherapy Responders. Metabolites, 16(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010014