Antiproliferative and Pro-Apoptotic Effects of Tuber borchii Extracts on Human Colorectal Cancer Cells via p53-Dependent Pathway Activation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Truffle Collection and Molecular Identification

2.2. Preparation of the Ethanolic Extract

2.3. Cell Cultures

2.4. Analysis of Cell Viability and Proliferation

2.5. Treatments

2.6. Preparation of Nuclear and Cytosolic Extracts

2.7. Western Blot Analysis

2.8. Analysis of Apoptosis

2.9. RT-qPCR Analysis

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

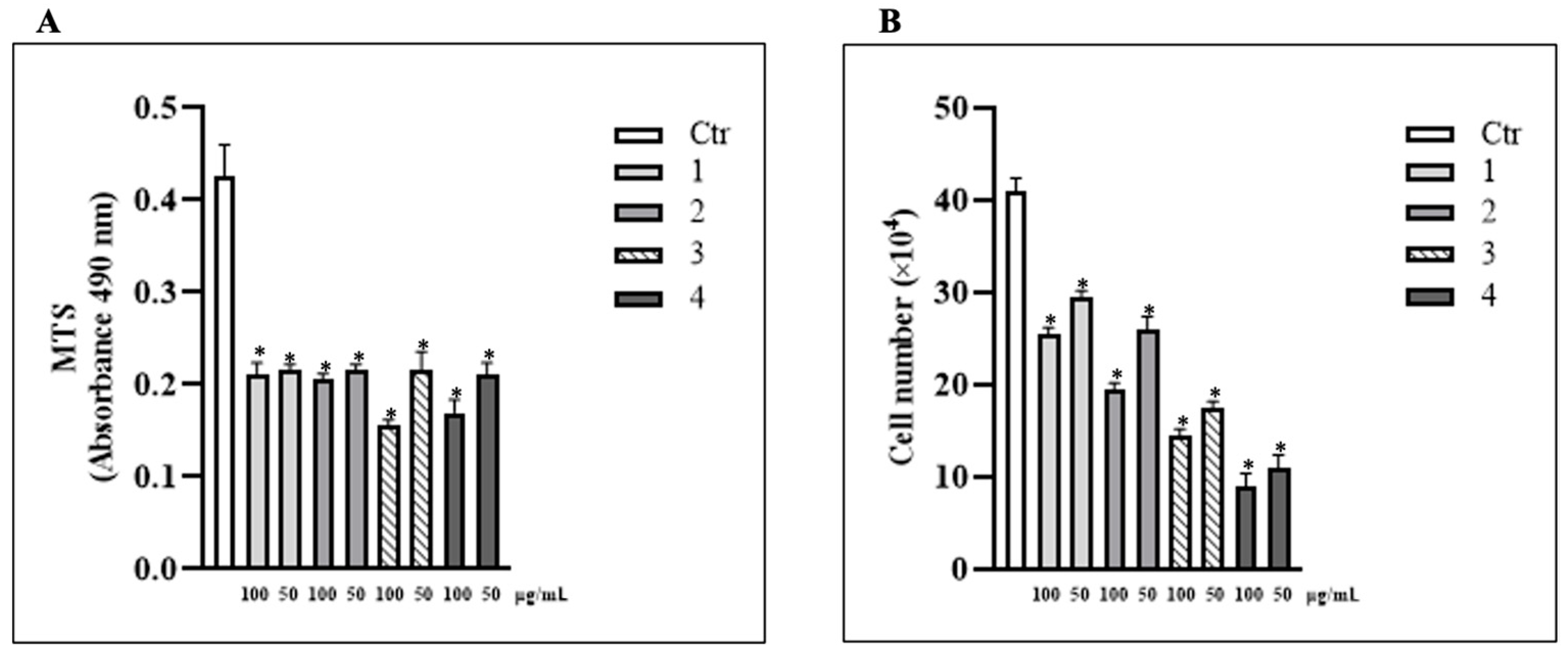

3.1. Treatment with T. borchii Induced a Proliferation Arrest of HCT 116 Cells

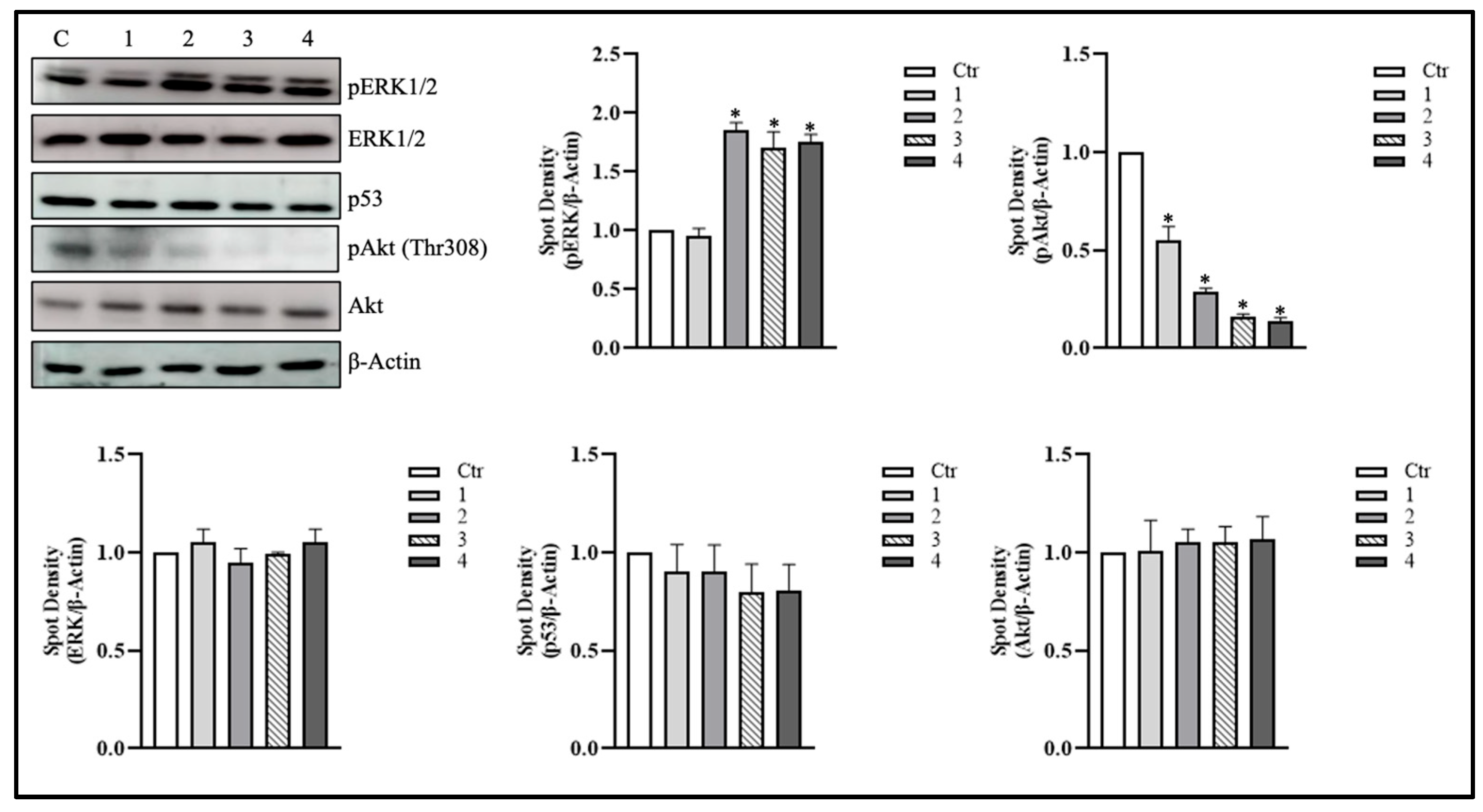

3.2. T. borchii Extracts Induce ERK1/2 Phosphorylation in HCT 116 Cells

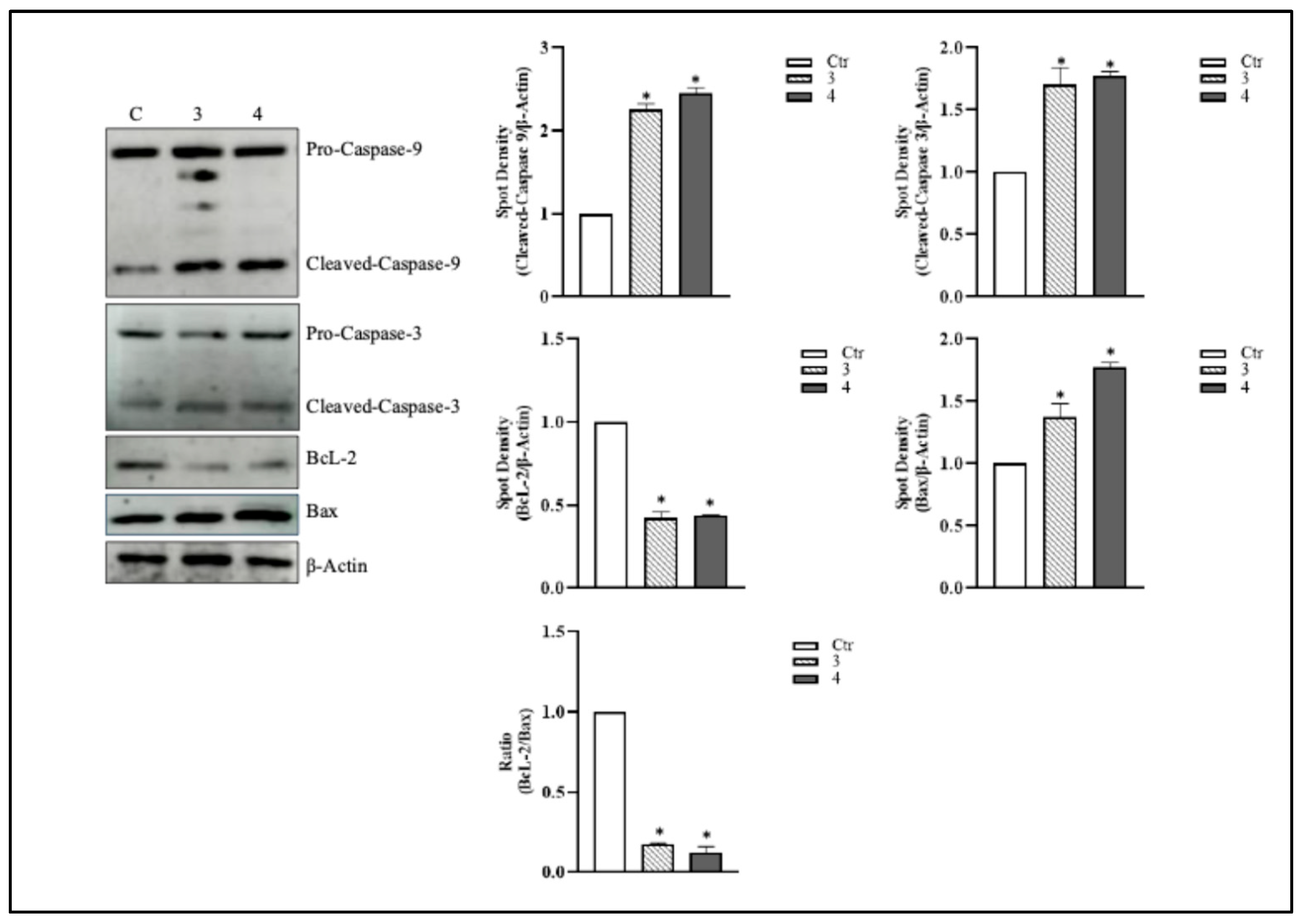

3.3. T. borchii Induces Apoptotic Cell Death in HCT 116 Cells

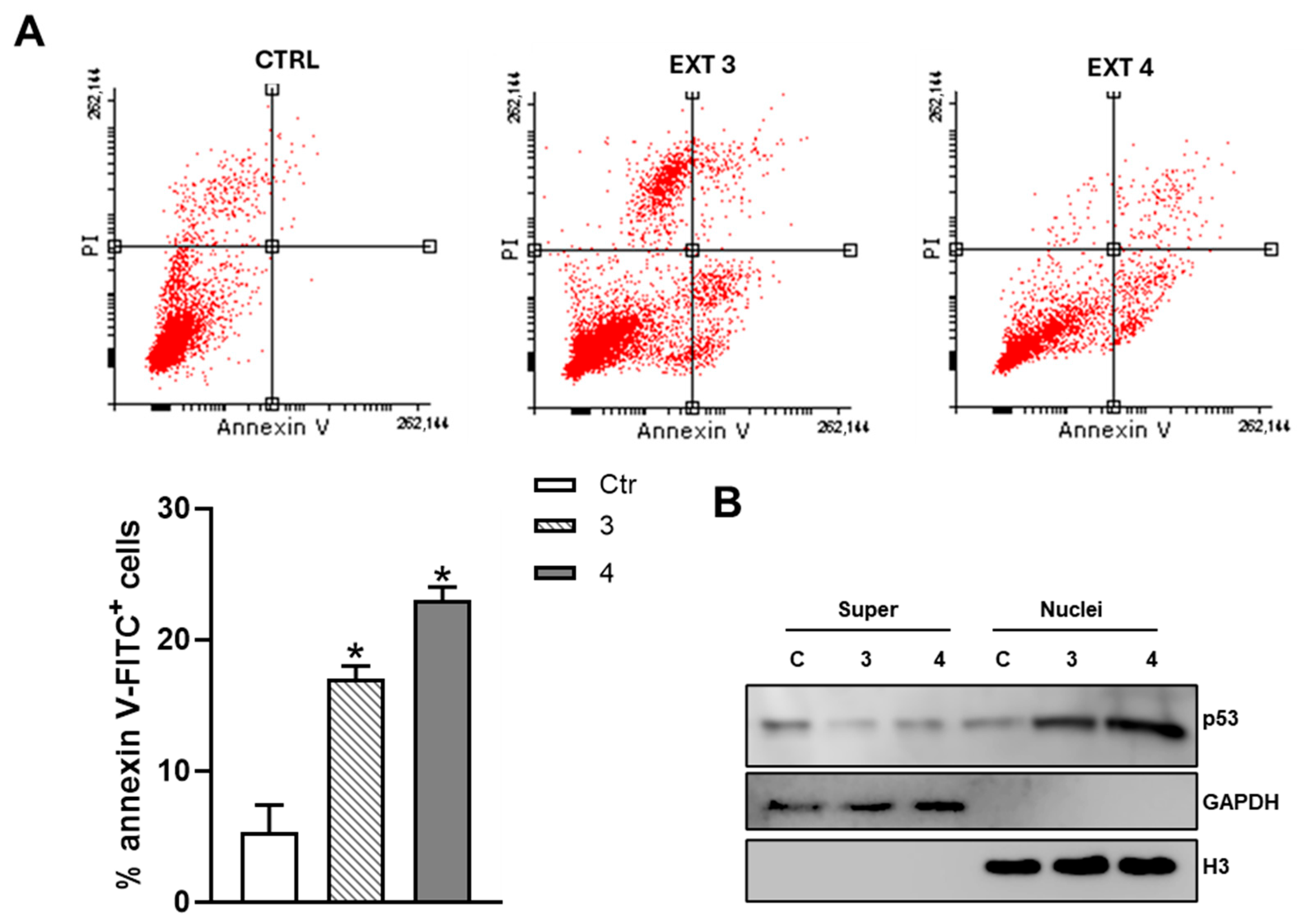

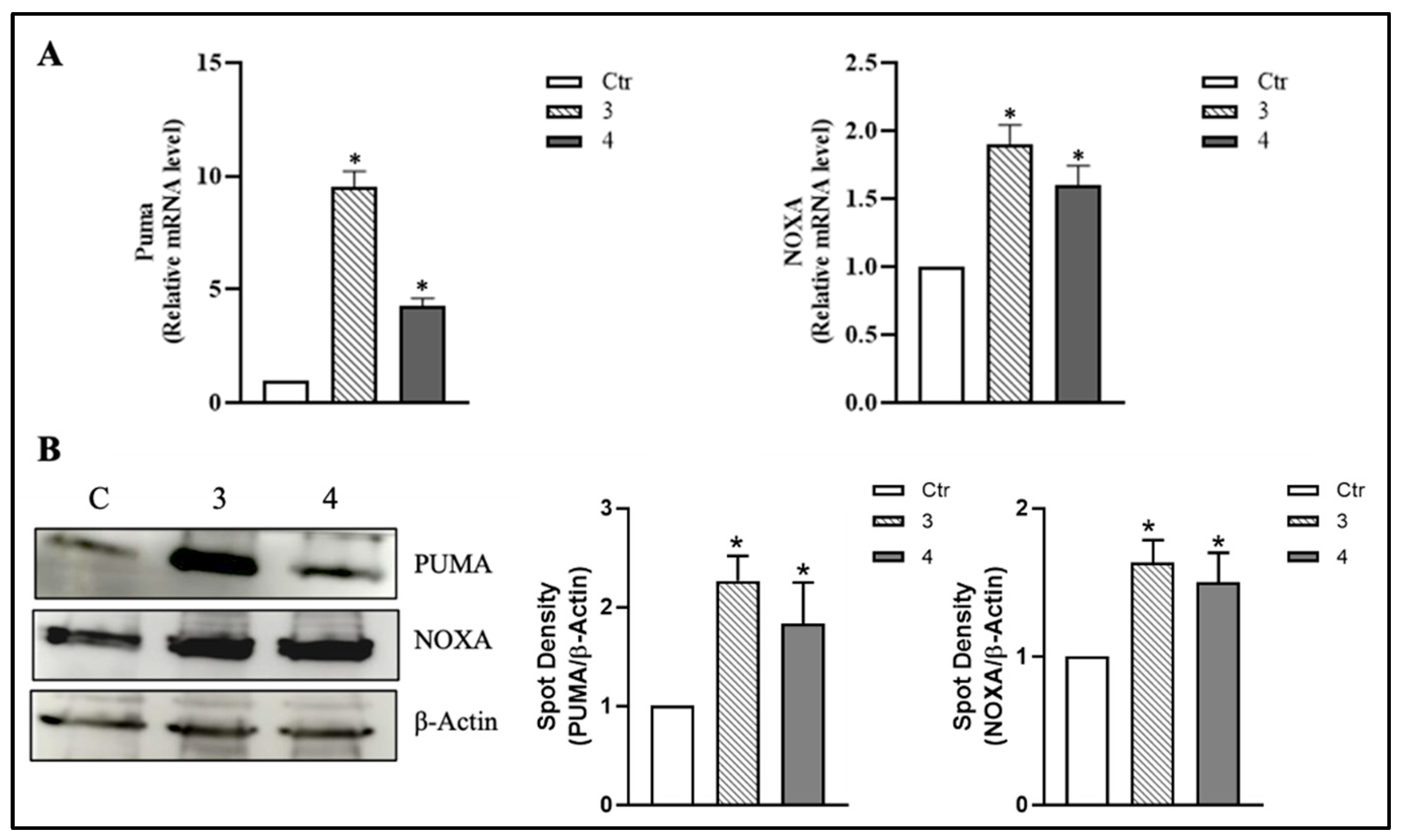

3.4. T. borchii Extracts Induce Nuclear Translocation of p53 and Up-Regulation of Its Pro-Apoptotic Targets PUMA and NOXA in HCT 116 Cells

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Akt | Protein kinase B |

| BAX | Bcl-2 Associated X-protein |

| Bcl-2 | B-cell lymphoma 2 |

| CRC | Colorectal cancer |

| ERK1/2 | Extracellular signal-Regulated Kinases1/2 |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| NOXA | Phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate-induced protein 1 |

| PUMA | p53 upregulated modulator of apoptosis |

| Z-VAD-FMK | Carbobenzoxy-valyl-alanes-aspartyl-(O-methyl)-fluoromethylketone |

References

- Eng, C.; Yoshino, T.; Ruíz-García, E.; Mostafa, N.; Cann, C.G.; O’Brian, B.; Benny, A.; Perez, R.O.; Cremolini, C. Colorectal cancer. Lancet 2024, 404, 294–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, D.E.; Sutherland, R.L.; Town, S.; Chow, K.; Fan, J.; Forbes, N.; Heitman, S.J.; Hilsden, R.J.; Brenner, D.R. Risk factors for early-onset colorectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 20, 1229–1240.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.-Y.; Chen, J.-L.; Li, H.; Su, K.; Han, Y.-W. Different types of fruit intake and colorectal cancer risk: A meta-analysis of observational studies. World J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 29, 2679–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.-H.; Niu, Y.-B.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, F.; Liu, C.-X.; Fan, L.; Mei, Q.-B. Role of phytochemicals in colorectal cancer prevention. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 9262–9272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, P.V.; Fernandes, E.; Soares, T.B.; Adega, F.; Lopes, C.M.; Lúcio, M. Natural compounds: Co-delivery strategies with chemotherapeutic agents or nucleic acids using lipid-based nanocarriers. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padeliadu, S.; Giazitzidou, S. A synthesis of research on reading fluency develompent: Study of eight meta-analyses. Eur. J. Spec. Educ. Res. 2018, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Nam, K.; Zahra, Z.; Farooqi, M.Q.U. Potentials of truffles in nutritional and medicinal applications: A review. Fungal Biol. Biotechnol. 2020, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-C.; Nargotra, P.; Kuo, C.-H.; Liu, Y.-C. High-molecular-weight exopolysaccharides production from Tuber brochii cultivated by submerged fermentation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henkrar, F.; Khabar, L. Proximate Analysis of Lipid Composition in Moroccan Truffles and Desert Truffles. Ital. J. Food Sci. 2022, 34. Available online: https://www.itjfs.com/index.php/ijfs/article/view/2202 (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Yan, X.; Wang, Y.; Sang, X.; Fan, L. Nutritional value, chemical composition and antioxidant activity of three Tuber species from China. AMB Express 2017, 7, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segelke, T.; Schelm, S.; Ahlers, C.; Fischer, M. Food authentication: Truffle (Tuber spp.) species differentiation by FT-NIR and chemometrics. Foods 2020, 9, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldelli, S.; Aiello, G.; De Bruno, A.; Castelli, S.; Lombardo, M.; Stocchi, V.; Tripodi, G. Bioactive compounds and antioxidant potential of truffles: A comprehensive review. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, C.; Hellal, K.; Taş Küçükaydın, M.; Çayan, F.; Küçükaydın, S.; Duru, M.E. Volatile compound profiling of seven Tuber species using HS-SPME-GC-MS and classification by a chemometric approach. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 34111–34119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, N.; Marathe, S.J.; Croce, D.; Ciardi, M.; Longo, V.; Juilus, A.; Shamekh, S. An investigation of the antioxidant potential and bioaccumulated minerals in Tuber borchii and Tuber maculatum mycelia obtained by submerged fermentation. Arch. Microbiol. 2021, 204, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolocci, F.; Rubini, A.; Granetti, B.; Arcioni, S. Rapid molecular approach for a reliable identification of Tuber spp. ectomycorrhizae. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 1999, 28, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltarelli, R.; Palma, F.; Gioacchini, A.M.; Calcabrini, C.; Mancini, U.; De Bellis, R.; Stocchi, V.; Potenza, L. Phytochemical composition, antioxidant and antiproliferative activities and effects on nuclear DNA of ethanolic extract from an Italian mycelial isolate of Ganoderma lucidum. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 231, 464–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeppa, S.; Gioacchini, A.M.; Guidi, C.; Guescini, M.; Pierleoni, R.; Zambonelli, A.; Stocchi, V. Determination of specific volatile organic compounds synthesised during Tuber borchii fruit body development by solid-phase microextraction and gas chromatography/mass spectrometry: SPME-GC/MS of VOCs during tuber fruit body development. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2004, 18, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowry, O.H.; Rosebrough, N.J.; Farr, A.L.; Randall, R.J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 1951, 193, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Obaydi, M.F.; Hamed, W.M.; Al Kury, L.T.; Talib, W.H. Terfezia boudieri: A desert truffle with anticancer and immunomodulatory activities. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.-W.; Lee, E.-R.; Min, H.-M.; Jeong, H.-S.; Ahn, J.-Y.; Kim, J.-H.; Choi, H.-Y.; Choi, H.; Kim, E.Y.; Park, S.P.; et al. Sustained ERK activation is involved in the kaempferol-induced apoptosis of breast cancer cells and is more evident under 3-D culture condition. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2008, 7, 1080–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thamkachy, R.; Kumar, R.; Rajasekharan, K.N.; Sengupta, S. ERK mediated upregulation of death receptor 5 overcomes the lack of p53 functionality in the diaminothiazole DAT1 induced apoptosis in colon cancer models: Efficiency of DAT1 in Ras-Raf mutated cells. Mol. Cancer 2016, 15, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, G. The role of the dysfunctional akt-related pathway in cancer: Establishment and maintenance of a malignant cell phenotype, resistance to therapy, and future strategies for drug development. Scientifica 2013, 2013, 317186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, R.; Chen, R.; Li, H. Cross-talk between PI3K/Akt and MEK/ERK pathways mediates endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced cell cycle progression and cell death in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2009, 34, 1749–1757. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Lee, E.-R.; Kim, J.-Y.; Kang, Y.-J.; Ahn, J.-Y.; Kim, J.-H.; Kim, B.-W.; Choi, H.-Y.; Jeong, M.-Y.; Cho, S.-G. Interplay between PI3K/Akt and MAPK signaling pathways in DNA-damaging drug-induced apoptosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2006, 1763, 958–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radisavljevic, Z.M.; González-Flecha, B. TOR kinase and Ran are downstream from PI3K/Akt in H2O2-induced mitosis: Signaling Through PI3K/Akt/TOR/Ran. J. Cell. Biochem. 2004, 91, 1293–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Mao, W.; Ding, B.; Liang, C.-S. ERKs/p53 signal transduction pathway is involved in doxorubicin-induced apoptosis in H9c2 cells and cardiomyocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2008, 295, H1956–H1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maietta, I.; Del Peschio, F.; Buonocore, P.; Viscusi, E.; Laudati, S.; Iannaci, G.; Minopoli, M.; Motti, M.L.; De Falco, V. P90RSK regulates p53 pathway by MDM2 phosphorylation in thyroid tumors. Cancers 2022, 15, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, L.A.; Clarke, P.R. Apoptosis and autophagy: Regulation of caspase-9 by phosphorylation: Regulation of caspase-9 by phosphorylation. FEBS J. 2009, 276, 6063–6073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belcher, B.P.; Ward, C.C.; Nomura, D.K. Ligandability of E3 ligases for targeted protein degradation applications. Biochemistry 2023, 62, 588–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, H.; Zhang, K.; Pan, G.; Li, C.; Li, C.; Hu, X.; Yang, L.; Cui, H. Deoxyelephantopin induces apoptosis and enhances chemosensitivity of colon cancer via miR-205/Bcl2 axis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, J.; Cui, P.; Li, Y.; Yao, X.; Wu, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, C. LINC02418 promotes colon cancer progression by suppressing apoptosis via interaction with miR-34b-5p/BCL2 axis. Cancer Cell Int. 2020, 20, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, Q.B.; Bode, A.M.; Ma, W.Y.; Chen, N.Y.; Dong, Z. Resveratrol-induced activation of p53 and apoptosis is mediated by extracellular-signal-regulated protein kinases and p38 kinase. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 1604–1610. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.-X.; Ma, D.-Y.; Yao, Z.-Q.; Fu, C.-Y.; Shi, Y.-X.; Wang, Q.-L.; Tang, Q.-Q. ERK1/2/p53 and NF-κB dependent-PUMA activation involves in doxorubicin-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2016, 20, 2435–2442. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nakano, K.; Vousden, K.H. PUMA, a novel proapoptotic gene, is induced by p53. Mol. Cell 2001, 7, 683–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholamalizadeh, M.; Tajadod, S.; Majidi, N.; Aghakhaninejad, Z.; Mahmoudi, Z.; Mousavi, Z.; Amjadi, A.; Alami, F.; Torkaman, M.; Saeedirad, Z.; et al. Associations between diet and nutritional supplements and colorectal cancer: A systematic review. JGH Open 2024, 8, e13108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R.; Akash, S.; Rahman, M.M.; Nowrin, F.T.; Akter, T.; Shohag, S.; Rauf, A.; Aljohani, A.S.M.; Simal-Gandara, J. Colon cancer and colorectal cancer: Prevention and treatment by potential natural products. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2022, 368, 110170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Jayachandran, M.; Ganesan, K.; Xu, B. Black truffle aqueous extract attenuates oxidative stress and inflammation in STZ-induced hyperglycemic rats via Nrf2 and NF-κB pathways. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejedor-Calvo, E.; Amara, K.; Reis, F.S.; Barros, L.; Martins, A.; Calhelha, R.C.; Venturini, M.E.; Blanco, D.; Redondo, D.; Marco, P.; et al. Chemical composition and evaluation of antioxidant, antimicrobial and antiproliferative activities of Tuber and Terfezia truffles. Food Res. Int. 2021, 140, 110071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, J.-Y.; Chen, M.-H.; Lai, Y.-S.; Chen, S.-D. Antioxidant profile and biosafety of white truffle mycelial products obtained by solid-state fermentation. Molecules 2021, 27, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Liao, Y.; Na, J.; Wu, L.; Yin, Y.; Mi, Z.; Fang, S.; Liu, X.; Huang, Y. The involvement of ascorbic acid in cancer treatment. Molecules 2024, 29, 2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardelčíková, A.; Šoltys, J.; Mojžiš, J. Oxidative stress, inflammation and colorectal cancer: An overview. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahham, S.S.; Al-Rawi, S.S.; Ibrahim, A.H.; Abdul Majid, A.S.; Abdul Majid, A.M.S. Antioxidant, anticancer, apoptosis properties and chemical composition of black truffle Terfezia claveryi. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 25, 1524–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawaya, K.; Abou Najem, S.; Khawaja, G.; Khalil, M. Proapoptotic and antiproliferative effects of the desert truffle Terfezia boudieri on colon cancer cell lines. Evid. Based. Complement. Alternat. Med. 2023, 2023, 1693332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ori, F.; Leonardi, M.; Puliga, F.; Lancellotti, E.; Pacioni, G.; Iotti, M.; Zambonelli, A. Ectomycorrhizal fungal community and ascoma production in a declining Tuber borchii plantation. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodapasand, E.; Jafarzadeh, N.; Farrokhi, F.; Kamalidehghan, B.; Houshmand, M. Is Bax/Bcl-2 ratio considered as a prognostic marker with age and tumor location in colorectal cancer? Iran. Biomed. J. 2015, 19, 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Shibue, T.; Suzuki, S.; Okamoto, H.; Yoshida, H.; Ohba, Y.; Takaoka, A.; Taniguchi, T. Differential contribution of Puma and Noxa in dual regulation of p53-mediated apoptotic pathways. EMBO J. 2006, 25, 4952–4962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, L.; Zhang, C.; Yuan, J.; Zhu, K.; Tomás, H.; Sheng, R.; Yang, X.H.; Tu, Q.; Guo, R. Progress of ERK pathway-modulated natural products for anti-non-small-cell lung cancer activity. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cagnol, S.; Chambard, J.-C. ERK and cell death: Mechanisms of ERK-induced cell death--apoptosis, autophagy and senescence: ERK and cell death. FEBS J. 2010, 277, 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, N.; Lum, M.A.; Lewis, R.E.; Black, A.R.; Black, J.D. A novel antiproliferative PKCα-Ras-ERK signaling axis in intestinal epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 102121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Chen, Y.; Liu, G.; Li, C.; Song, Y.; Cao, Z.; Li, W.; Hu, J.; Lu, C.; Liu, Y. PI3K/AKT pathway as a key link modulates the multidrug resistance of cancers. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heavey, S.; O’Byrne, K.J.; Gately, K. Strategies for co-targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in NSCLC. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2014, 40, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Antibody | Code | Brand |

|---|---|---|

| Akt | 9272 | Cell Signaling |

| Bax | 2772 | Cell Signaling |

| BcL-2 | B3170 | Sigma-Aldrich |

| β-actin | 4970S | Cell Signaling |

| Caspase-3 | C8487 | Sigma-Aldrich |

| Caspase-9 | 05-572 | Upstate |

| ERK 1/2 | 9102 | Cell Signaling |

| GAPDH | 2118 | Cell Signaling |

| Histone H3 | 9715 | Cell Signaling |

| p53 | P5813 | Sigma-Aldrich |

| p-Akt 1/2 (Thr 308) | 9275 | Cell Signaling |

| p-ERK 1/2 | 9101 | Cell Signaling |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carinci, E.; Castelli, S.; Vitiello, L.; Pennesi, A.; Amicucci, A.; Zambonelli, A.; Ciriolo, M.R.; Stocchi, V.; Baldelli, S. Antiproliferative and Pro-Apoptotic Effects of Tuber borchii Extracts on Human Colorectal Cancer Cells via p53-Dependent Pathway Activation. Metabolites 2025, 15, 796. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15120796

Carinci E, Castelli S, Vitiello L, Pennesi A, Amicucci A, Zambonelli A, Ciriolo MR, Stocchi V, Baldelli S. Antiproliferative and Pro-Apoptotic Effects of Tuber borchii Extracts on Human Colorectal Cancer Cells via p53-Dependent Pathway Activation. Metabolites. 2025; 15(12):796. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15120796

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarinci, Emily, Serena Castelli, Laura Vitiello, Alessandro Pennesi, Antonella Amicucci, Alessandra Zambonelli, Maria Rosa Ciriolo, Vilberto Stocchi, and Sara Baldelli. 2025. "Antiproliferative and Pro-Apoptotic Effects of Tuber borchii Extracts on Human Colorectal Cancer Cells via p53-Dependent Pathway Activation" Metabolites 15, no. 12: 796. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15120796

APA StyleCarinci, E., Castelli, S., Vitiello, L., Pennesi, A., Amicucci, A., Zambonelli, A., Ciriolo, M. R., Stocchi, V., & Baldelli, S. (2025). Antiproliferative and Pro-Apoptotic Effects of Tuber borchii Extracts on Human Colorectal Cancer Cells via p53-Dependent Pathway Activation. Metabolites, 15(12), 796. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15120796