Metabolic Shifts Induced by Treatment with Statin Influences Circulating Concentrations of the Stress Hormone, Cortisol, but Has Different Effects on Selected Cytokines, Adipokines and Neuropeptides in Lean and Fat Lines of Young Pigs

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Tissue Culture

2.2. Assays

2.3. RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

2.4. Real-Time PCR (qPCR)

3. Results

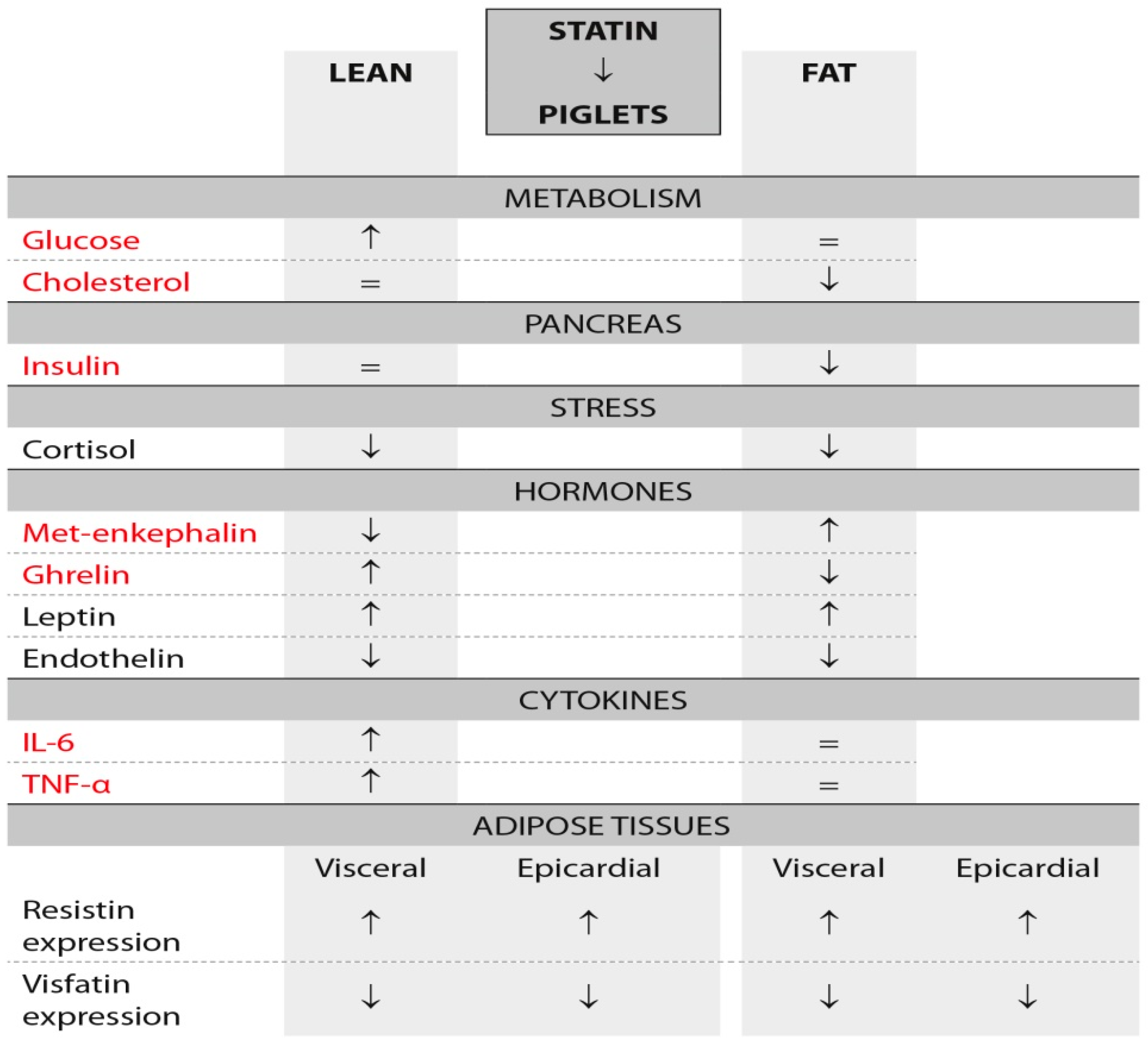

3.1. Plasma Concentrations of Cholesterol, Glucose, Insulin and Cortisol

3.2. Adipose Expression of Resistin and Visfatin

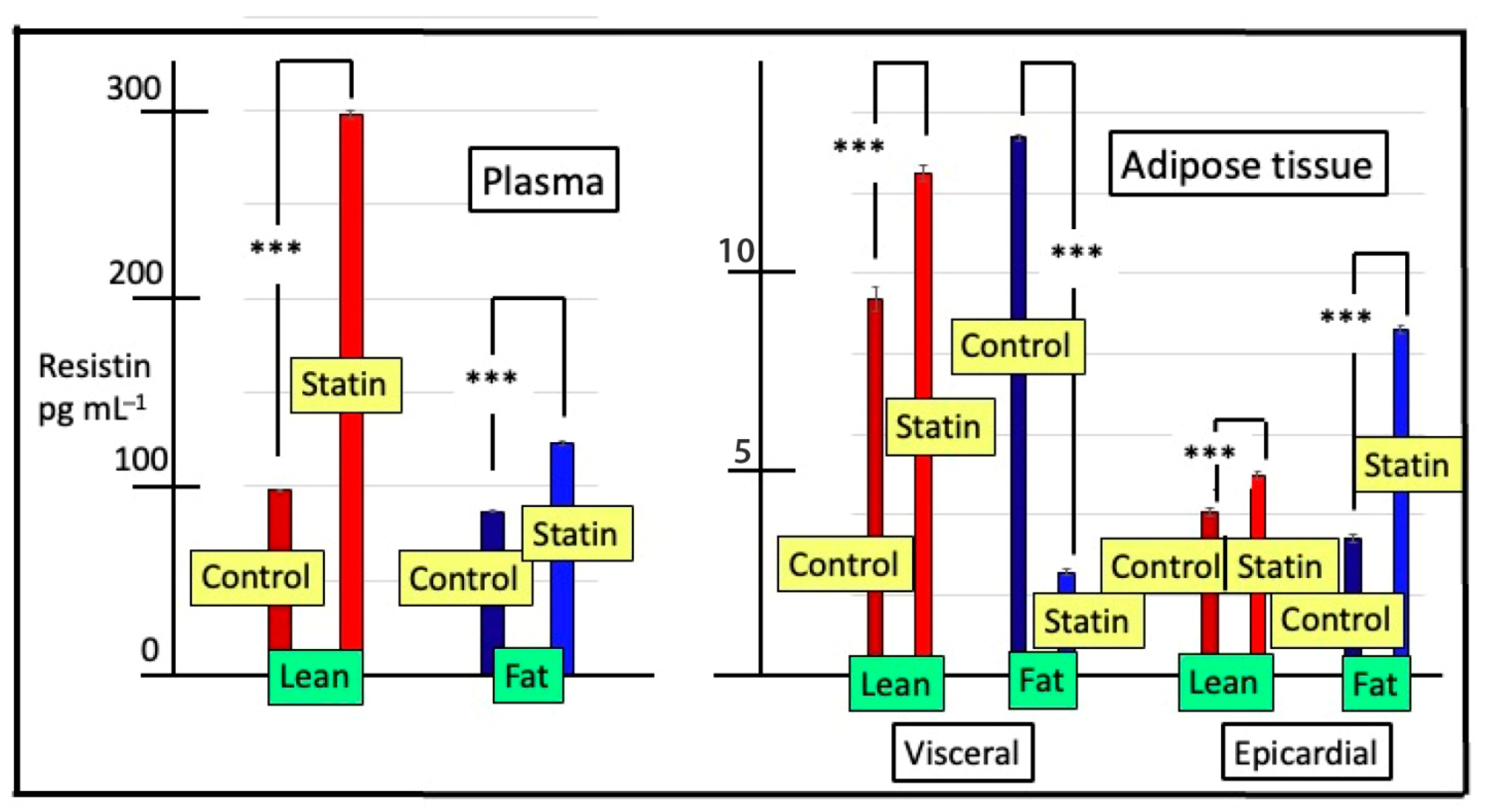

3.3. Plasma and Tissue Concentrations of Resistin

3.4. Plasma and Tissue Concentrations of Visfatin

3.5. Plasma Concentrations of Met-Enkephalin, Ghrelin, IL-6, TNFα, Leptin and Endothelin

3.6. Adipose Tissue Concentrations of Leptin, TNFα and Ghrelin

3.7. In Vitro Ghrelin Release from Hypothalamic, Pituitary and Adrenal Explants

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yuan, F.; Zhang, Q.; Dong, H.; Xiang, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.J. Effects of des-acyl ghrelin on insulin sensitivity and macrophage polarization in adipose tissue. Transl. Int. Med. 2021, 9, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiran, S.; Mandal, M.; Rakib, A.; Bajwa, A.; Singh, U.P. miR-10a-3p modulates adiposity and suppresses adipose inflammation through TGF-beta1/Smad3 signaling pathway. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1213415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Mansoori, L.; Al-Jaber, H.; Prince, M.S.; Elrayess, M.A. Role of inflammatory cytokines, growth factors and adipokines in adipogenesis and insulin resistance. Inflammation 2022, 45, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustafson, B.; Smith, U. Cytokines promote wnt signaling and inflammation and impair the normal differentiation and lipid accumulation in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 9507–9516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Proenca, R.; Maffei, M.; Barone, M.; Leopold, L.; Friedman, J.M. Positional cloning of the mouse obese gene and its human homologue. Nature 1994, 372, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Basinski, M.B.; Beals, J.M.; Briggs, S.L.; Churgay, L.M.; Clawson, D.K.; DiMarchi, R.D.; Furman, T.C.; Hale, J.E.; Hsiung, H.M.; et al. Crystal structure of the obese protein leptin-E100. Nature 1997, 387, 206–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiernan, K.; MacIver, N.J. The role of the adipokine leptin in immune cell function in health and disease. Front. Immunol. 2021, 11, 622468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, H.; Pan, H.; Wang, L.; Yang, H.; Zhu, H.; Gong, F. Ghrelin promotes proliferation and inhibits differentiation of 3T3-L1 and human primary preadipocytes. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratajczak, M.; Buczyński, J.T. Origins and development of the Polish indigenous Złotnicka spotted pig. Anim. Sci. Pap. Rep. 1997, 15, 137–147. [Google Scholar]

- Koseniuk, A.; Smołucha, G.; Natonek-Winiewska, M.; Radko, A.; Rubiś, D. Differentiating pigs from wild boars based on NR6A1 and MC1R gene polymorphisms. Animals 2021, 11, 2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slow Food Foundation for Biodiversity. 2024. Available online: https://www.fondazioneslowfood.com/en/ark-of-taste-slow-food/pulawska-pig/ (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- Nachtigal, P.; Jamborova, G.; Pospisilova, N.; Pospechova, K.; Solichova, D.; Zdansky, P.; Semecky, V. Atorvastatin has distinct effects on endothelial markers in different mouse models of atherosclerosis. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2006, 9, 222–230. [Google Scholar]

- Amuzie, C.; Swart, J.R.; Rogers, C.S.; Vihtelic, T.; Denham, S.; Mais, D.E. A Translational Model for Diet-related Atherosclerosis: Effect of Statins on Hypercholesterolemia and Atherosclerosis in a Minipig. Toxicol. Pathol. 2016, 44, 442–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lastuvkova, H.; Faradonbeh, F.A.; Schreiberova, J.; Hroch, M.; Mokry, J.; Faistova, H.; Nova, Z.; Hyspler, R.; Sa, I.C.I.; Nachtigal, P.; et al. Atorvastatin Modulates Bile Acid Homeostasis in Mice with Diet-Induced Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, S.; Matthan, N.R.; Lamon-Fava, S.; Solano-Aguilar, G.; Turner, J.R.; Walker, M.E.; Chai, Z.; Lakshman, S.; Chen, C.; Dawson, H.; et al. Colon transcriptome is modified by a dietary pattern/atorvastatin interaction in the Ossabaw pig. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2021, 90, 108570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierzchała-Koziec, K.; Dziedzicka-Wasylewska, M.; Scanes, C.G. Isolation stress impacts Met-enkephalin in the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical axis in growing Polish Mountain sheep: A possible role of the opioids in modulation of HPA axis. Stress 2019, 22, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chomczynski, P.; Sacchi, N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal. Biochem. 1987, 162, 156–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaffl, M.W. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001, 29, e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanska, K.; Zaobidna, E.; Rytelewska, E.; Mlyczynska, E.; Kurowska, P.; Dobrzyn, K.; Kiezun, M.; Kaminska, B.; Smolinska, N.; Rak, A.; et al. Visfatin in the porcine pituitary gland: Expression and regulation of secretion during the oestrous cycle and early pregnancy. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 18253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbe, A.; Kurowska, P.; Mlyczyńska, E.; Ramé, C.; Staub, C.; Venturi, E.; Billon, Y.; Rak, A.; Dupont, J. Adipokines expression profiles in both plasma and peri renal adipose tissue in Large White and Meishan sows: A possible involvement in the fattening and the onset of puberty. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2020, 299, 113584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocłoń, E.; Zubel-Łojek, J.; Latacz, A.; Pierzchała-Koziec, K. Hyperglycemia-induced changes in resistin gene expression in white adipose tissue in piglets. Ann. Anim. Sci. 2015, 15, 667–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos, C.; Latorre, P.; López-Buena, P. The effects of chromium picolinate and simvastatin on pig serum cholesterol contents in swine muscular and adipose tissues. Livest. Sci. 2016, 185, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busnelli, M.; Manzini, S.; Froio, A.; Vargiolu, A.; Cerrito, M.G.; Smolenski, R.T.; Massimo Giunti, M.; Cinti, A.; Zannoni, A.; Leone, B.E.; et al. Diet induced mild hypercholesterolemia in pigs: Local and systemic inflammation, effects on vascular injury—Rescue by high-dose statin treatment. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e80588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakata, M.; Nagasaka, S.; Kusaka, I.; Matsuoka, H.; Ishibashi, S.; Yada, T. Effects of statins on the adipocyte maturation and expression of glucose transporter 4 (SLC2A4): Implications in glycaemic control. Diabetologia 2006, 49, 1881–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casula, M.; Mozzanica, F.; Scotti, L.; Tragni, E.; Pirillo, A.; Corrao, G.; Catapano, A.L. Statin use and risk of new-onset diabetes: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2017, 27, 396–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainey, W.E.; Shay, J.W.; Mason, J.I. ACTH induction of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase, cholesterol biosynthesis, and steroidogenesis in primary cultures of bovine adrenocortical cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1986, 261, 7322–7326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainey, W.E.; Rodgers, R.J.; Mason, J.I. The role of bovine lipoproteins in the regulation of steroidogenesis and HMG-CoA reductase in bovine adrenocortical cells. Steroids 1992, 57, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahebkar, A.; Rathouska, J.; Simental-Mendía, L.E.; Nachtigal, P. Statin therapy and plasma cortisol concentrations: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Pharmacol. Res. 2016, 103, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janke, J.; Engeli, S.; Gorzelniak, K.; Luft, F.C.; Sharma, A.M. Resistin gene expression in human adipocytes is not related to insulin resistance. Obes. Res. 2002, 10, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyu, K.G.; Chua, S.K.; Wang, B.W.; Kuan, P. Mechanism of inhibitory effect of atorvastatin on resistin expression induced by tumor necrosis factor-alpha in macrophages. J. Biomed. Sci. 2009, 16, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, M.H.; Xia, T.; Chen, X.D.; Gan, L.; Feng, S.Q.; Qiu, H.; Peng, Y.; Yang, Z.Q. Cloning and characterization of porcine resistin gene. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 2006, 30, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curat, C.A.; Wegner, V.; Sengenès, C.; Miranville, A.; Tonus, C.; Busse, R.; Bouloumié, A. Macrophages in human visceral adipose tissue: Increased accumulation in obesity and a source of resistin and visfatin. Diabetologia 2006, 49, 744–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirichenko, T.V.; Markina, Y.V.; Bogatyreva, A.I.; Tolstik, T.V.; Varaeva, Y.R.; Starodubova, A.V. The role of adipokines in inflammatory mechanisms of obesity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poizat, G.; Alexandre, C.; Al Rifai, S.; Riffault, L.; Crepin, D.; Benomar, Y.; Taouis, M. Maternal resistin predisposes offspring to hypothalamic inflammation and body weight gain. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagl, V.; Grenier, B.; Pinton, P.; Ruczizka, U.; Dippel, M.; Bünger, M.; Oswald, I.P.; Soler, L. Exposure to zearalenone leads to metabolic disruption and changes in circulating adipokines concentrations in pigs. Toxins 2021, 13, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puchałowicz, K.; Kłoda, K.; Dziedziejko, V.; Rać, M.; Wojtarowicz, A.; Chlubek, D.; Safranow, K. Association of adiponectin, leptin and resistin plasma concentrations with echocardiographic parameters in patients with coronary artery disease. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Romero, B.; Muñoz-Prieto, A.; Cerón, J.J.; Martín-Cuervo, M.; Iglesias-García, M.; Aguilera-Tejero, E.; Díez-Castro, E. Measurement of plasma resistin concentrations in horses with metabolic and inflammatory disorders. Animals 2021, 12, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biernat, W.; Szczęsna, M.; Kirsz, K.; Zieba, D.A. Seasonal and nutritional fluctuations in the mRNA levels of the short form of the leptin receptor (lra) in the hypothalamus and anterior pituitary in resistin-treated sheep. Animals 2021, 11, 2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ichida, Y.; Hasegawa, G.; Fukui, M.; Obayashi, H.; Ohta, M.; Fujinami, A.; Ohta, K.; Nakano, K.; Yoshikawa, T.; Nakamura, N. Effect of atorvastatin on in vitro expression of resistin in adipocytes and monocytes/macrophages and effect of atorvastatin treatment on serum resistin levels in patients with type 2 diabetes. Pharmacology 2006, 76, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahebkar, A.; Giorgini, P.; Ludovici, V.; Pedone, C.; Ferretti, G.; Bacchetti, T.; Grassi, D.; Di Giosia, P.; Ferri, C. Impact of statin therapy on plasma resistin and visfatin concentrations: A systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Pharmacol. Res. 2016, 111, 827–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, K.Z.; Li, Y.R.; Zhang, D.; Yuan, J.H.; Zhang, C.S.; Liu, Y.; Song, L.M.; Lin, Q.; Li, M.W.; Dong, J. Relation of circulating resistin to insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes and obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, C.S.; Lee, K.T.; Lee, M.Y.; Su, H.M.; Voon, W.C.; Sheu, S.H.; Lai, W.T. Effects of atorvastatin and atorvastatin withdrawal on soluble CD40L and adipocytokines in patients with hypercholesterolaemia. Acta Cardiol. 2006, 61, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szotowska, M.; Czerwienska, B.; Adamczak, M.; Chudek, J.; Wiecek, A. Plasma concentrations of adiponectin, leptin, resistin and insulin were measured before initiation and after 2, 4 and 6 months of atorvastatin therapy. Kidney Blood Press. Res. 2012, 35, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Xia, T.; Zhou, L.; Chen, X.; Gan, L.; Yao, W.; Peng, Y.; Yang, Z. Gene organization, alternate splicing and expression pattern of porcine visfatin gene. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 2007, 32, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadoglou, N.P.E.; Velidakis, N.; Khattab, E.; Kassimis, G.; Patsourakos, N. The interplay between statins and adipokines. Is this another explanation of statins ‘pleiotropic’ effects? Cytokine 2021, 148, 155698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaminski, T.; Kiezun, M.; Zaobidna, E.; Dobrzyn, K.; Wasilewska, B.; Mlyczynska, E.; Rytelewska, E.; Kisielewska, K.; Gudelska, M.; Bors, K.; et al. Plasma level and expression of visfatin in the porcine hypothalamus during the estrous cycle and early pregnancy. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 8698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrzyn, K.; Kopij, G.; Kiezun, M.; Zaobidna, E.; Gudelska, M.; Zarzecka, B.; Paukszto, L.; Rak, A.; Smolinska, N.; Kaminski, T. Visfatin (NAMPT) affects global gene expression in porcine anterior pituitary cells during the mid-luteal phase of the oestrous cycle. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2024, 15, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, H.K.; Demirtas, B. The effect of hydrophilic statins on adiponectin, leptin, visfatin, and vaspin levels in streptozocin-induced diabetic rats. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2025, 398, 3977–3984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maillard, V.; Elis, S.; Desmarchais, A.; Hivelin, C.; Lardic, L.; Lomet, D.; Uzbekova, S.; Monget, P.; Dupont, J. Visfatin and resistin in gonadotroph cells: Expression, regulation of LH secretion and signalling pathways. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2017, 29, 2479–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, Y.; Liang, T.; Wang, G.; Li, Z. Ghrelin, a gastrointestinal hormone, regulates energy balance and lipid metabolism. Biosci. Rep. 2018, 38, BSR20181061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granata, R.; Ghigo, E.E. Products of the ghrelin gene, the pancreatic beta-cell and the adipocyte. Endocr. Dev. 2013, 25, 144–156. [Google Scholar]

- Peiu, S.N.; Iosep, D.G.; Danciu, M.; Scripcaru, V.; Ianole, V.; Mocanu, V.J. Ghrelin expression in atherosclerotic plaques and perivascular adipose tissue: Implications for vascular inflammation in peripheral artery disease. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, N. Expression, regulation and biological actions of growth hormone (GH) and ghrelin in the immune system. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 2009, 19, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnanapavan, S.; Kola, B.; Bustin, S.A.; Morris, D.G.; McGee, P.; Fairclough, P.; Bhattacharya, S.; Carpenter, R.; Grossman, A.B.; Korbonits, M. The tissue distribution of the mRNA of ghrelin and subtypes of its receptor, GHS-R, in humans. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2002, 87, 2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hattori, N.; Saito, T.; Yagyu, T.; Jiang, B.H.; Kitagawa, K.; Inagaki, C. GH, GH receptor, GH secretagogue receptor, and ghrelin expression in human T cells, B cells, and neutrophils. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001, 86, 4284–4291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansaldo, A.M.; Montecucco, F.; Sahebkar, A.; Dallegri, F.; Carbone, F. Epicardial adipose tissue and cardiovascular diseases. Int. J. Cardiol. 2019, 278, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, T.H. Epicardial adipose tissue: A new cardiovascular risk marker? Int. J. Cardiol. 2019, 278, 263–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goeller, M.; Achenbach, S.; Marwan, M.; Doris, M.K.; Cadet, S.; Commandeur, F.; Chen, X.; Slomka, P.J.; Gransar, H.; Cao, J.J.; et al. Epicardial adipose tissue density and volume are related to subclinical atherosclerosis, inflammation and major adverse cardiac events in asymptomatic subjects. J. Cardiovasc. Comput. Tomogr. 2017, 12, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | F/R | Primers | bp (bp) | Accession No. Non-Number Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18S rRNA | F R | 5′-CTTTGGTCGCTCGCTCCTC-3′ 5′-CTGACCGGGTTGGTTTTGAT-3′ | 115 | AY265350.1 |

| Resistin Based on [14] | F R | 5′-ATGAAGCCATCAATGAGA-3′ 5′-GCCTGAGGGGCAGGTGAC-3′ | 89 | Nm_213783.1 |

| Visfatin Based on [15] | F R | 5′-CCAGTTGCTGATCCCAACAAA-3′ 5′-AAATTCCCTCCTGGTGTCCTATG-3′ | 95 | XM_003132281.5 |

| Cholesterol mMol L−1 | Glucose mMol L−1 | Insulin pg mL−1 | Cortisol ng mL−1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lean breed (PBZ) | ||||

| Control | 2.84 ± 0.11 a | 1.5 ± 0.09 a | 114 ± 4.31 a | 117 ± 3.12 d |

| Statin | 2.88 ± 0.09 a | 3.2 ± 0.16 b | 115 ± 3.44 a | 61.6 ± 1.36 b |

| Fat breed (Puławska) | ||||

| Control | 4.90 ± 0.10 b | 2.8 ± 0.51 b | 196 ± 4.00 b | 102 ± 2.60 c |

| Statin | 3.14 ± 0.09 a | 2.7 ± 0.43 b | 126 ± 3.71 a | 41.4 ± 0.93 a |

| Visceral Adipose | Epicardial Adipose | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resistin Expression | Visfatin Expression | Resistin Expression | Visfatin Expression | |

| Lean Breed (PBZ) | ||||

| Control | 1.00 ± 0.09 a | 1.00 ± 0.12 b | 1.00 ± 0.12 a | 1.00 ± 0.12 b |

| Statin | 2.63 ± 0.19 ab | 0.03 ± 0.006 a | 1.40 ± 0.06 a | 0.003 ± 0.001 a |

| Fat breed (Puławska) | ||||

| Control | 1.00 ± 0.12 a | 1.00 ± 0.09 b | 1.00 ± 0.12 a | 1.00 ± 0.12 b |

| Statin | 3.93 ± 0.09 c | 0.21 ± 0.018 a | 1.90 ± 0.12 b | 0.020 ± 0.0014 a |

| Groups | Tissue | |

|---|---|---|

| Hypothalamus | Pituitary | |

| Control lean | 0.75 ± 0.09 b | 0.41 ± 0.04 b |

| Statin lean | 0.29 ± 0.02 c | 0.51 ± 0.03 c |

| Control fat | 0.22 ± 0.02 c | 1.81 ± 0.11 a |

| Statin fat | 0.19 ± 0.02 a | 1.62 ± 0.10 d |

| Breed and Treatment | Plasma Concentrations of Visfatin pg mL−1 | Tissue Concentrations of Visfatin | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adipose Tissue | Hypothalamic pg mg−1 | Pituitary Gland pg mg−1 | |||

| Visceral ng mg−1 | Epicardial pg mg−1 | ||||

| Lean breed | |||||

| Control | 493 ± 10.7 d | 1.81 ± 0.017 a | 0.10 ± 0.007 a | 0.23 ± 0.012 b | 1.14 ± 0.029 b |

| Statin | 396 ± 8.7 c | 1.81 ± 0.016 a | 0.60 ± 0.015 b | 0.10 ± 0.011 a | 0.62 ± 0.015 a |

| Fat breed | |||||

| Control | 218 ± 1.03 a | 4.36 ± 0.093 c | 0.82 ± 0.017 c | 0.53 ± 0.011 c | 2.82 ± 0.019 d |

| Statin | 308 ± 1.28 b | 2.70 ± 0.071 b | 4.98 ± 0.030 d | 0.23 ± 0.009 b | 1.35 ± 0.021 c |

| Breed/Treatment | Met-Enkephalin pg mL−1 | Ghrelin ng mL−1 | IL-6 pg mL−1 | TNFα pg mL−1 | Leptin ng mL−1 | Endothelin pg mL−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lean | ||||||

| Control | 59.6 ± 2.03 b | 11.0 ± 0.71 a | 25.2 ± 0.86 b | 39.4 ± 0.93 b | 2.15 ± 0.019 a | 13.9 ± 0.09 c |

| Statin | 29.6 ± 0.87 d | 15.8 ± 1.16 ab | 30.2 ± 0.37 c | 41.8 ± 0.86 b | 2.53 ± 0.021 b | 10.0 ± 0.16 b |

| Fat | ||||||

| Control | 42.4 ± 1.21 a | 17.6 ± 1.08 b | 15.4 ± 0.51 a | 33.4 ± 0.51 a | 2.72 ± 0.014 b | 10.4 ± 0.51 b |

| Statin | 64.0 ± 0.84 c | 13.6 ± 0.93 ab | 12.2 ± 1.06 a | 35.2 ± 0.66 a | 3.51 ± 0.038 c | 7.72 ± 0.43 a |

| Breed/Treatment | Visceral Adipose Tissue | Epicardial Adipose Tissue | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leptin pg mg−1 | TNFα ng mg−1 | Leptin pg mg−1 | Ghrelin pg mg−1 | |

| Lean | ||||

| Control | 3.75 ± 0.030 a | 1.76 ± 0.019 a | 17.2 ± 0.196 a | 50.2 ± 1.36 a |

| Statin | 1.94 ± 0.026 a | 5.99 ± 0.054 c | 16.5 ± 0.201 a | 75.2 ± 1.07 c |

| Fat | ||||

| Control | 2.41 ± 0.023 c | 6.04 ± 0.025 c | 10.2 ± 0.093 c | 62.6 ± 1.03 b |

| Statin | 0.66 ± 0.017 b | 2.04 ± 0.020 b | 7.1 ± 0.086 b | 116 ± 3.03 d |

| Breed/Treatment | Release of Ghrelin as pg/mg Tissue/30 min | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothalamic Tissue | Pituitary Tissue | Adrenal Tissue | ||||

| Basal Release | Delta +Naltrexone | Basal Release | Delta +Naltrexone | Basal Release | Delta +Naltrexone | |

| Lean | ||||||

| Control | 10.4 ± 0.51 a | 4.2 ± 0.58 a | 22.6 ± 0.51 a | 4.4 ± 0.81 a | 17.6 ± 0.51 a | 11.0 ± 1.38 b |

| Statin | 13.2 ± 0.37 ab | 2.8 ± 0.92 a | 31.0 ± 1.14 b | 6.0 ± 1.34 a | 39.4 ± 0.81 c | 10.0 ± 0.77 b |

| Fat | ||||||

| Control | 14.8 ± 0.58 b | 10.0 ± 0.90 b | 32.0 ± 0.51 b | 2.8 ± 1.07 a | 29.4 ± 0.93 b | 4.4 ± 1.44 a |

| Statin | 23.2 ± 1.24 c | 10.0 ± 0.89 b | 31.8 ± 0.86 b | 12.0 ± 1.39 b | 41.2 ± 0.86 c | 9.0 ± 1.76 ab |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pierzchała-Koziec, K.; Scanes, C.G.; Zubel-Łojek, J.; Kucharski, M. Metabolic Shifts Induced by Treatment with Statin Influences Circulating Concentrations of the Stress Hormone, Cortisol, but Has Different Effects on Selected Cytokines, Adipokines and Neuropeptides in Lean and Fat Lines of Young Pigs. Metabolites 2025, 15, 797. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15120797

Pierzchała-Koziec K, Scanes CG, Zubel-Łojek J, Kucharski M. Metabolic Shifts Induced by Treatment with Statin Influences Circulating Concentrations of the Stress Hormone, Cortisol, but Has Different Effects on Selected Cytokines, Adipokines and Neuropeptides in Lean and Fat Lines of Young Pigs. Metabolites. 2025; 15(12):797. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15120797

Chicago/Turabian StylePierzchała-Koziec, Krystyna, Colin G. Scanes, Joanna Zubel-Łojek, and Mirosław Kucharski. 2025. "Metabolic Shifts Induced by Treatment with Statin Influences Circulating Concentrations of the Stress Hormone, Cortisol, but Has Different Effects on Selected Cytokines, Adipokines and Neuropeptides in Lean and Fat Lines of Young Pigs" Metabolites 15, no. 12: 797. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15120797

APA StylePierzchała-Koziec, K., Scanes, C. G., Zubel-Łojek, J., & Kucharski, M. (2025). Metabolic Shifts Induced by Treatment with Statin Influences Circulating Concentrations of the Stress Hormone, Cortisol, but Has Different Effects on Selected Cytokines, Adipokines and Neuropeptides in Lean and Fat Lines of Young Pigs. Metabolites, 15(12), 797. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15120797