Dietary Inorganic Nitrate Accelerates Cardiac Parasympathetic Recovery After Exercise in Older Women with Hypertension: A Secondary Analysis of a Randomised Crossover Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

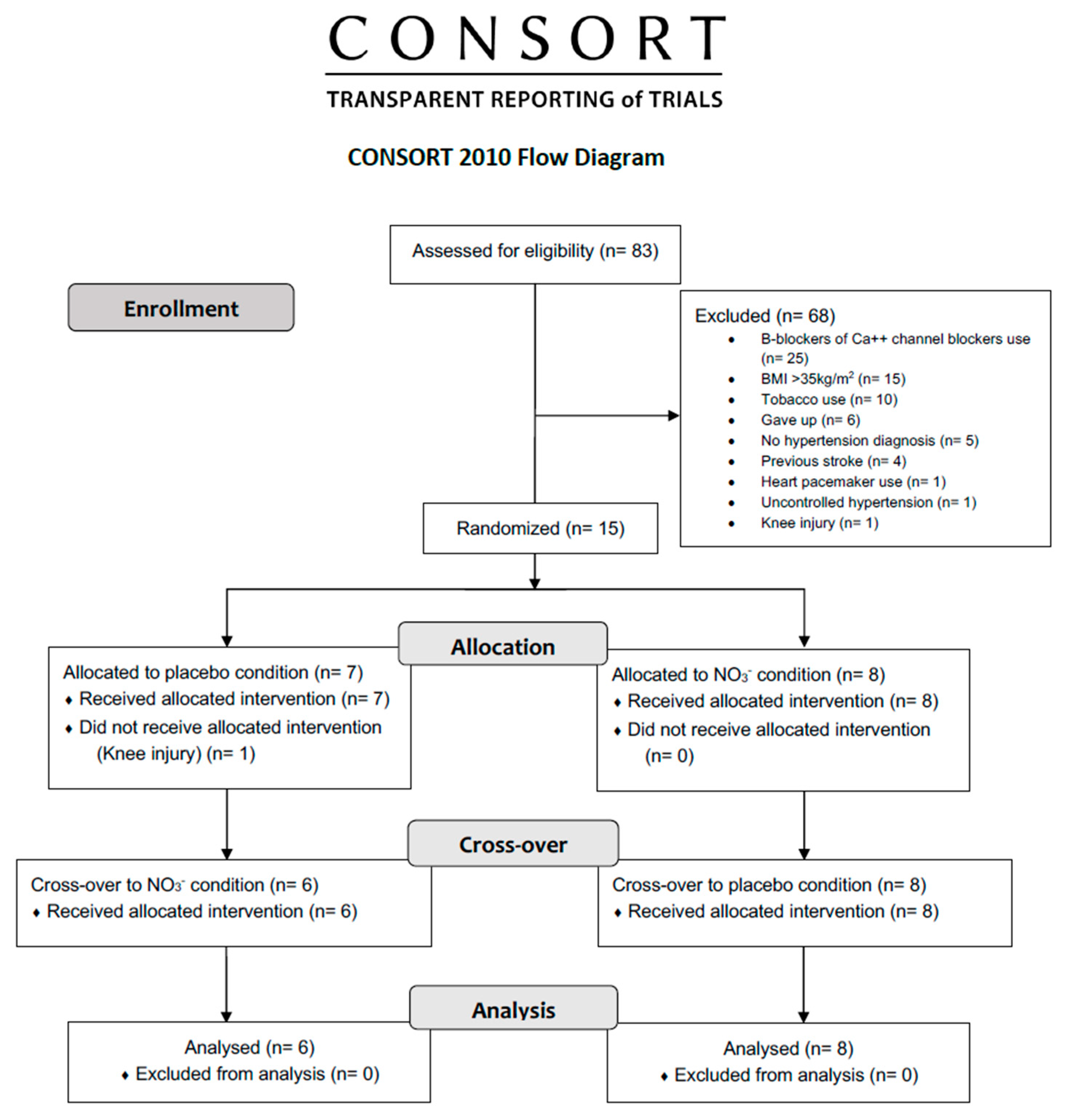

2.1. Trial Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Before Intervention Assessment

2.3.1. Anthropometry and Body Composition

2.3.2. Blood Pressure and Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing (CPET)

2.4. Intervention

2.4.1. Inorganic Nitrate Ingestion

2.4.2. Submaximal Aerobic Exercise

2.5. Outcomes

2.5.1. Cardiac Parasympathetic Recovery Analysis

2.5.2. Blood Collection and Processing

2.5.3. NO3− and NO2− Plasma Analysis

2.6. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Participants

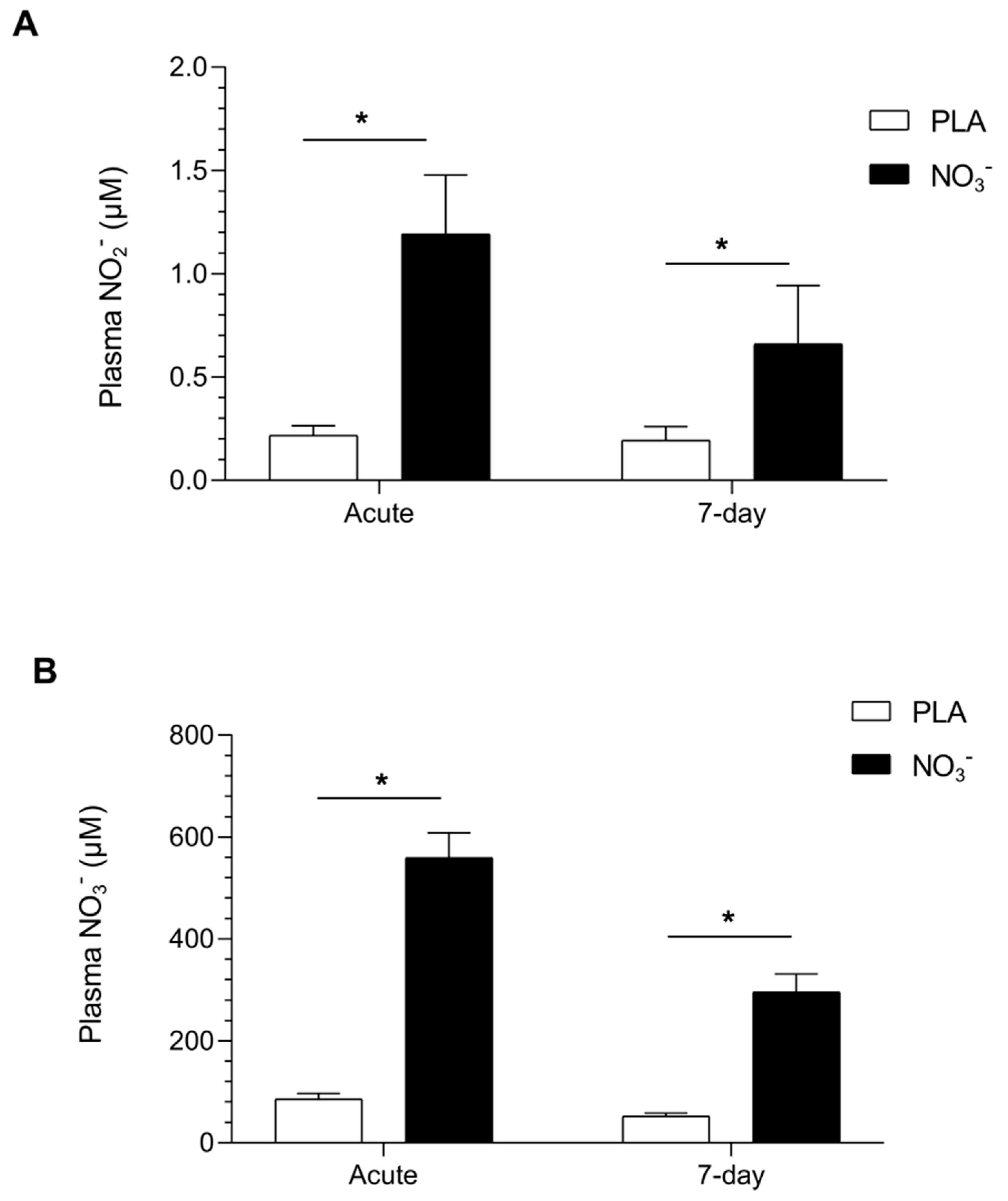

3.2. Nitric Oxide Stable Metabolites Plasma Concentrations

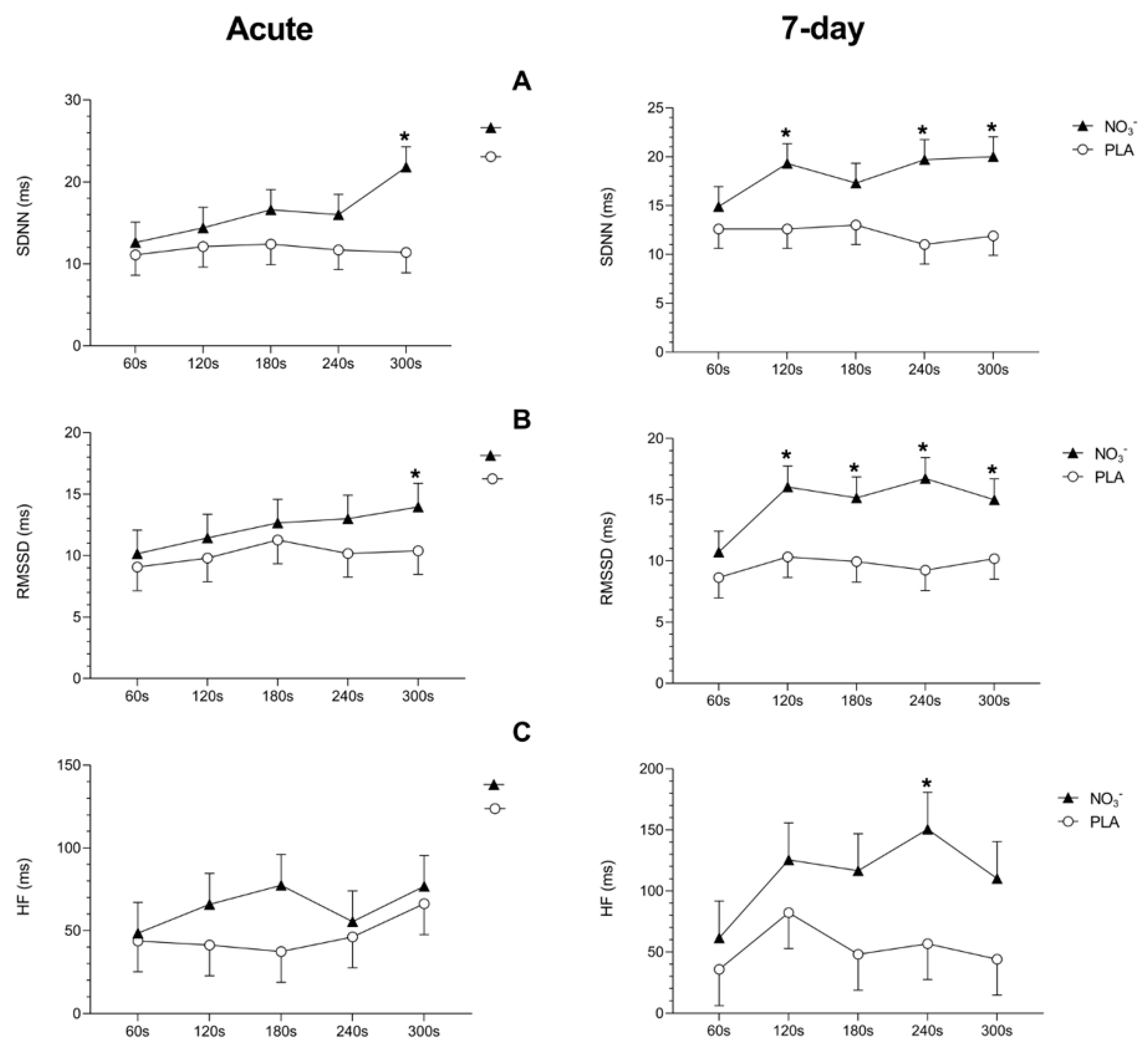

3.3. Cardiac Parasympathetic Recovery After Exercise

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lundberg, J.O.; Weitzberg, E.; Gladwin, M.T. The nitrate-nitrite-nitric oxide pathway in physiology and therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008, 7, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamim, C.J.R.; Gonçalves, L.d.S.; da Silva, L.S.L.; Júnior, C.R.B. Restoring nitric oxide production using dietary inorganic nitrate: Recent advances on cardiovascular and physical performance in middle-aged and older adults. Med. Gas. Res. 2025, 15, 200–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, J.O.; Weitzberg, E. Nitric oxide signaling in health and disease. Cell 2022, 185, 2853–2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamim, C.J.R.; Porto, A.A.; Valenti, V.E.; Sobrinho, A.C.d.S.; Garner, D.M.; Gualano, B.; Júnior, C.R.B. Nitrate Derived From Beetroot Juice Lowers Blood Pressure in Patients with Arterial Hypertension: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 823039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babateen, A.M.; Shannon, O.M.; O’bRien, G.M.; Olgacer, D.; Koehl, C.; Fostier, W.; Mathers, J.C.; Siervo, M. Moderate doses of dietary nitrate elicit greater effects on blood pressure and endothelial function than a high dose: A 13-week pilot study. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2023, 33, 1263–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellano, M.; Rizzoni, D.; Beschi, M.; Lorenza Muiesan, M.; Porteri, E.; Bettoni, G.; Salvetti, M.; Cinelli, A.; Zulli, R.; Agabiti-Rosei, E. Relationship between sym-pathetic nervous system activity, baroreflex and cardiovascular effects after acute nitric oxide synthesis inhibi-tion in humans. J. Hypertens. 1995, 13, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raimundo, R.D.; Laurindo, L.F.; Gimenez, F.V.M.; Benjamim, J.; Gonzaga, L.A.; Barbosa, M.P.C.R.; Martins, M.d.M.; Ito, E.H.; Barroca, A.L.; Brito, G.d.J.; et al. Beetroot Supplementation as a Nutritional Strategy to Support Post-Exercise Autonomic Recovery in Postmenopausal Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sartori, C.; Lepori, M.; Scherrer, U. Interaction between nitric oxide and the cholinergic and sympathetic nervous system in cardiovascular control in humans. Pharmacol. Ther. 2005, 106, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choate, J.K.; Paterson, D.J. Nitric oxide inhibits the positive chronotropic and inotropic responses to sympathetic nerve stimulation in the isolated guinea-pig atria. J. Auton. Nerv. Syst. 1999, 75, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, K.L.; Hildreth, K.L.; Meditz, A.L.; Deane, K.D.; Kohrt, W.M. Endothelial Function Is Impaired across the Stages of the Menopause Transition in Healthy Women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 97, 4692–4700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, C.J.; DeLorey, D.S. Effect of acute dietary nitrate supplementation on sympathetic vasoconstriction at rest and during exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. 2019, 127, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjamim, C.J.R.; da Silva, L.S.L.; Valenti, V.E.; Gonçalves, L.S.; Porto, A.A.; Júnior, M.F.T.; Walhin, J.-P.; Garner, D.M.; Gualano, B.; Júnior, C.R.B.; et al. Effects of dietary inorganic nitrate on blood pressure during and post-exercise recovery: A systematic review and me-ta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 215, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bescos, R.; Gallardo-Alfaro, L.; Ashor, A.; Rizzolo-Brime, L.; Siervo, M.; Casas-Agustench, P. Nitrate and nitrite bioavailability in plasma and saliva: Their association with blood pressure—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 226, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaffer, F.; Meehan, Z.M.; Zerr, C.L. A Critical Review of Ultra-Short-Term Heart Rate Variability Norms Research. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 594880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancia, G.; Grassi, G. The autonomic nervous system and hypertension. Circ. Res. 2014, 23, 1804–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valensi, P. Autonomic nervous system activity changes in patients with hypertension and overweight: Role and therapeutic implications. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2021, 20, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, C.R.; Blackstone, E.H.; Pashkow, F.J.; Snader, C.E.; Lauer, M.S. Heart-rate recovery immediately after exercise as a predictor of mortality. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 28, 1351–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderlei, L.C.M.; Pastre, C.M.; Hoshi, R.A.; Carvalho, T.D.d.; Godoy, M.F.d. Basic notions of heart rate variability and its clinical applicability. Rev. Bras. Cir. Cardiovasc. 2009, 24, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esco, M.R.; Williford, H.N.; Flatt, A.A.; Freeborn, T.J.; Nakamura, F.Y. Ultra-shortened time-domain HRV parameters at rest and following exercise in athletes: An alternative to frequency computation of sympathovagal balance. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2017, 118, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamim, C.J.R.; da Silva, L.S.L.; Sousa, Y.B.A.; da Silva Rodrigues, G.; de Moraes Pontes, Y.M.; Rebelo, M.A.; da Silva Gonçalves, L.; Tavares, S.S.; Guimarães, C.S.; da Silva Sobrinho, A.C.; et al. Acute and short-term beetroot juice nitrate-rich ingestion enhances cardiovascular responses following aerobic exercise in postmenopausal women with arterial hypertension: A triple-blinded randomized controlled trial. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 211, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamim, C.J.R.; Sousa, Y.B.A.; Porto, A.A.; Pontes, Y.M.d.M.; Tavares, S.S.; Rodrigues, G.d.S.; da Silva, L.S.L.; Goncalves, L.d.S.; Guimaraes, C.S.; Rebelo, M.A.; et al. Nitrate-rich beet juice intake on cardiovascular performance in response to exercise in postmenopausal women with arterial hypertension: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2023, 24, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamim, C.J.R.; Silva LSLda Gonçalves Lda, S.; Júnior, M.F.T.; Spellanzon, B.; Rebelo, M.A.; Tanus-Santos, J.E.; Bueno Júnior, C.R. The effects of die-tary nitrate ingestion on physical performance tests in 50–65 years old postmenopausal women: A pilot ran-domized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, and crossover study. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 43, 1642–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollenberg, M.; Ngo, L.H.; Turner, D.; Tager, I.B. Treadmill exercise testing in an epidemiologic study of elderly sub-jects. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 1998, 53, B259–B267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggett, D.L.; Connelly, D.M.; Overend, T.J. Maximal Aerobic Capacity Testing of Older Adults: A Critical Review. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2005, 60, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griesenbeck, J.S.; Steck, M.D.; Huber, J.C.; Sharkey, J.R.; Rene, A.A.; Brender, J.D. Development of estimates of dietary nitrates, nitrites, and nitrosamines for use with the short willet food frequency questionnaire. Nutr. J. 2009, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, K.V.C.; Costa, B.D.; Gomes, A.C.; Saunders, B.; Mota, J.F. Factors that Moderate the Effect of Nitrate Ingestion on Exercise Performance in Adults: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analyses and Meta-Regressions. Adv. Nutr. Int. Rev. J. 2022, 13, 1866–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, C.J.; Yang, J.N.; Scheer, F.A.J.L. The impact of the circadian timing system on cardiovascular and metabolic function. Prog. Brain Res. 2012, 199, 337–358. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D.P.; Jarczok, M.N.; Ellis, R.J.; Hillecke, T.K.; Thayer, J.F.; Koenig, J. Two-week test-retest reliability of the Po-lar® RS800CXTM to record heart rate variability. Clin. Physiol. Funct. Imaging 2017, 37, 776–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.E.V.; Fazan, R.; Marin-Neto, J.A. PyBioS: A freeware computer software for analysis of cardiovascular signals. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2020, 197, 105718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincon Soler, A.I.; Silva, L.E.V.; Fazan, R.; Murta, L.O. The impact of artifact correction methods of RR series on heart rate variability parameters. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2018, 124, 646–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarvainen, M.P.; Niskanen, J.-P.; Lipponen, J.A.; Ranta-Aho, P.O.; Karjalainen, P.A. Kubios HRV–Heart rate variability analysis software. Comput. Methods Progr. Biomed. 2014, 113, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahiri, M.K.; Kannankeril, P.J.; Goldberger, J.J. Assessment of Autonomic Function in Cardiovascular Disease: Physiological Basis and Prognostic Implications. J. AM Coll. Cardiol. 2008, 6, 1725–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, L.C.; Ferreira, G.C.; Amaral, J.H.; Portella, R.L.; Tella, S.d.O.; Passos, M.A.; Tanus-Santos, J.E. Oral nitrite circumvents antiseptic mouthwash-induced disruption of enterosalivary circuit of nitrate and promotes nitrosation and blood pressure lowering effect. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2016, 101, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, G.C.; Pinheiro, L.C.; Oliveira-Paula, G.H.; Angelis, C.D.; Portella, R.L.; Tanus-Santos, J.E. Antioxidant tempol modulates the increases in tissue nitric oxide metabolites concentrations after oral nitrite administration. Chem. Interact. 2021, 349, 109658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinheiro, L.C.; Ferreira, G.C.; de Angelis, C.D.; Toledo, J.C.; Tanus-Santos, J.E. A comprehensive time course study of tissue nitric oxide metabolites concentrations after oral nitrite administration. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 152, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feelisch, M.; Rassaf, T.; Mnaimneh, S.; Singh, N.; Bryan, N.S.; Jourd’Heuil, D.; Kelm, M. Concomitant S-, N-, and heme-nitros(yl)ation in biological tissues and fluids: Implications for the fate of NO in vivo. FASEB J. 2002, 16, 1775–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozemek, C.; Hildreth, K.L.; Blatchford, P.J.; Hurt, K.J.; Bok, R.; Seals, D.R.; Kohrt, W.M.; Moreau, K.L. Effects of resveratrol or estradiol on postexercise endothelial function in estrogen-deficient postmenopausal women. J. Appl. Physiol. 2020, 128, 739–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siervo, M.; Lara, J.; Ogbonmwan, I.; Mathers, J.C. Inorganic Nitrate and Beetroot Juice Supplementation Reduces Blood Pressure in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Nutr. 2013, 143, 818–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara, J.; Ashor, A.W.; Oggioni, C.; Ahluwalia, A.; Mathers, J.C.; Siervo, M. Effects of inorganic nitrate and beetroot supplementation on endothelial function: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Nutr. 2015, 55, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadoran, Z.; Mirmiran, P.; Kabir, A.; Azizi, F.; Ghasemi, A. The Nitrate-Independent Blood Pressure–Lowering Effect of Beetroot Juice: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Adv. Nutr. Int. Rev. J. 2017, 8, 830–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notay, K.; Incognito, A.V.; Millar, P.J. Acute beetroot juice supplementation on sympathetic nerve activity: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled proof-of-concept study. Am. J. Physiol. Circ. Physiol. 2017, 313, H59–H65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrijo, V.H.V.; Amaral, A.L.; Mariano, I.M.; de Souza, T.C.F.; Batista, J.P.; de Oliveira, E.P.; Puga, G.M. Beetroot juice intake with different amounts of nitrate does not change aerobic exercise-mediated responses in heart rate variability in hypertensive postmenopausal women: A randomized, crossover and double-blind study. J. Exerc. Sci. Fit. 2021, 19, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Values |

|---|---|

| Height (m) | 1.56 (0.02) |

| Mass (kg) | 71.2 (2.5) |

| Fat-free mass (kg) | 39.8 (1.3) |

| Fat mass (kg) | 30.7 (1.6) |

| Visceral fat (kg) | 2.59 (0.2) |

| BMQE (score) | 4.54 (0.4) |

| Cholesterol (mmol/L) | 3.87 (0.2) |

| HDL (mmol/L) | 0.87 (0.05) |

| LDL (mmol/L) | 2.5 (0.2) |

| TGL (mmol/L) | 2.6 (0.4) |

| Plasma NO3− (μM) | 19.8 (1.5) |

| Plasma NO2− (μM) | 0.07 (0.01) |

| SBP/DBP (mmHg) | 137 (4)/82 (2.4) (Visit 1) |

| 137 (3.4)/83 (1.8) Visit 2) | |

| 138 (3.7)/82 (2.1) (Visit 3) |

| Variables | Acute | 7-Day | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | NO3− | p-Value | Placebo | NO3− | p-Value | |

| NO2− (μM) Plasma | 0.19 (0.03) | 0.93 (0.18) * | <0.001 | 0.19 (0.05) | 0.48 (0.1) * | <0.001 |

| NO3− (μM) Plasma | 71.7 (7.4) | 465 (58.5) * | <0.001 | 74.3 (11) | 382 (26.4) * | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Benjamim, J.; Lopes da Silva, L.S.; Alves Sousa, Y.B.; Gonçalves, L.d.S.; Rodrigues, G.d.S.; Rebelo, M.A.; Tanus-Santos, J.E.; Valenti, V.E.; Bueno Júnior, C.R. Dietary Inorganic Nitrate Accelerates Cardiac Parasympathetic Recovery After Exercise in Older Women with Hypertension: A Secondary Analysis of a Randomised Crossover Study. Metabolites 2025, 15, 789. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15120789

Benjamim J, Lopes da Silva LS, Alves Sousa YB, Gonçalves LdS, Rodrigues GdS, Rebelo MA, Tanus-Santos JE, Valenti VE, Bueno Júnior CR. Dietary Inorganic Nitrate Accelerates Cardiac Parasympathetic Recovery After Exercise in Older Women with Hypertension: A Secondary Analysis of a Randomised Crossover Study. Metabolites. 2025; 15(12):789. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15120789

Chicago/Turabian StyleBenjamim, Jonas, Leonardo Santos Lopes da Silva, Yaritza Brito Alves Sousa, Leonardo da Silva Gonçalves, Guilherme da Silva Rodrigues, Macário Arosti Rebelo, José E. Tanus-Santos, Vitor Engrácia Valenti, and Carlos R. Bueno Júnior. 2025. "Dietary Inorganic Nitrate Accelerates Cardiac Parasympathetic Recovery After Exercise in Older Women with Hypertension: A Secondary Analysis of a Randomised Crossover Study" Metabolites 15, no. 12: 789. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15120789

APA StyleBenjamim, J., Lopes da Silva, L. S., Alves Sousa, Y. B., Gonçalves, L. d. S., Rodrigues, G. d. S., Rebelo, M. A., Tanus-Santos, J. E., Valenti, V. E., & Bueno Júnior, C. R. (2025). Dietary Inorganic Nitrate Accelerates Cardiac Parasympathetic Recovery After Exercise in Older Women with Hypertension: A Secondary Analysis of a Randomised Crossover Study. Metabolites, 15(12), 789. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15120789