1. Introduction

Metabolic syndrome encompasses a constellation of interrelated risk factors—central obesity, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and insulin resistance—that predispose individuals to type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and hepatic–renal dysfunction [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Because these disturbances evolve concomitantly across multiple organs, there is growing interest in composite, non-invasive biomarkers capable of capturing this multisystem burden early [

6,

7,

8].

The triglyceride–glucose (TyG) index has emerged as a promising surrogate for insulin resistance, being simple to calculate and showing predictive value in various metabolic and cardiovascular contexts. Tamini et al. recently reported that TyG and its modified forms (e.g., TyG-BMI, TyG-WC) reliably predict metabolic-associated fatty liver disease and metabolic syndrome even in pediatric obesity cohorts [

9,

10].

Moreover, a narrative review in MDPI emphasized TyG’s clinical potential and limitations, highlighting that although it correlates well with metabolic outcomes, further standardization is needed [

9].

Meanwhile, the FIB-4 score, derived from age, AST, ALT, and platelet count, serves as a widely used non-invasive marker of hepatic fibrosis and has been explored beyond liver disease. Sumida et al. have shown that elevated FIB-4 is associated with incident cardiovascular disease and longitudinal decline in renal function [

11,

12].

Additionally, Hara et al. demonstrated that FIB-4–derived hepatic fibrosis may predict tubular injury in subjects with type 2 diabetes, suggesting cross-talk between liver and kidney in metabolic disease [

13].

Estimating eGFR via established formulas provides accessible insight into renal function, which is compromised early in metabolic and vascular aging. The interrelation of hepatic stress and renal decline is increasingly recognized, particularly in populations with metabolic dysfunction-related liver disease.

However, few studies have concurrently evaluated TyG, FIB-4, and eGFR across stratified metabolic risk groups, nor have they dissected their independent contributions in multivariate models. This gap limits our understanding of how insulin resistance, hepatic fibrosis, and renal function interplay as metabolic risk escalates.

Therefore, the present study aimed to (1) assess the interrelationships among TyG, FIB-4, and eGFR across metabolic risk strata, and (2) determine their independent predictive value using multivariate regression models. By integrating these complementary markers, we seek to clarify the trajectory of metabolic–hepatic–renal deterioration and potentially improve early stratification of high-risk individuals.

4. Discussion

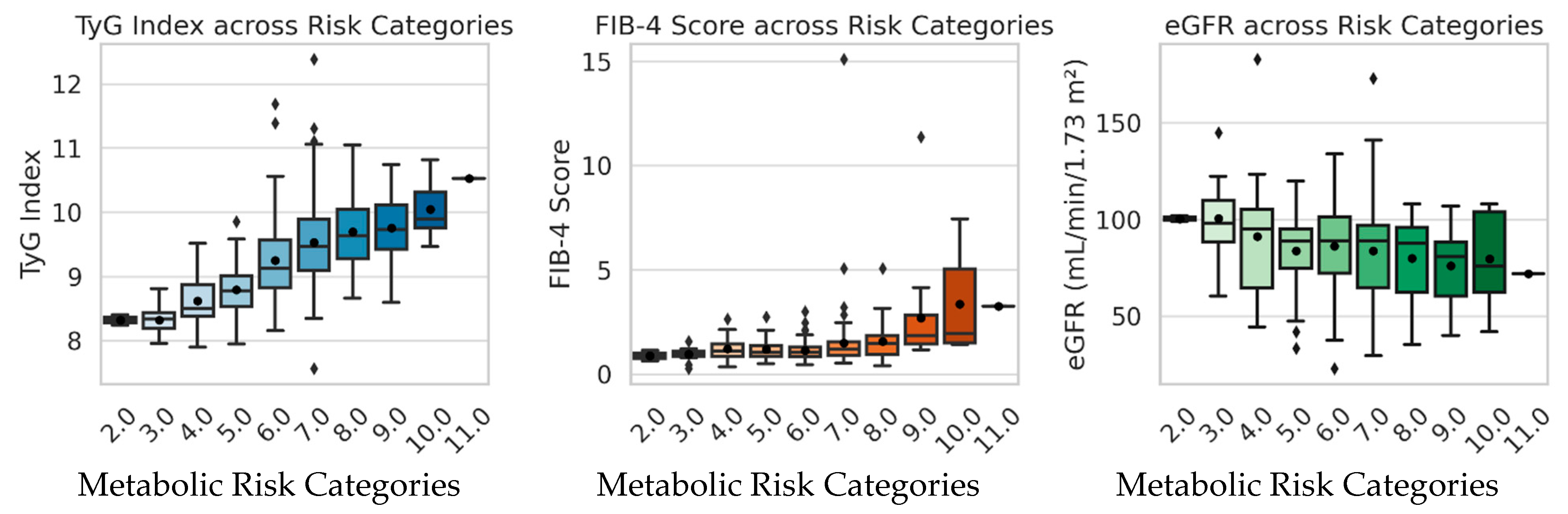

This study integrated metabolic, hepatic, and renal indicators—TyG index, FIB-4 score, and eGFR—to explore their interrelationships and predictive value across different categories of metabolic risk. The results revealed that both TyG and FIB-4 increased progressively with higher metabolic risk, while eGFR showed only a mild, non-significant decline. These findings suggest that hepatic alterations and insulin resistance become evident earlier in the metabolic continuum than overt renal impairment.

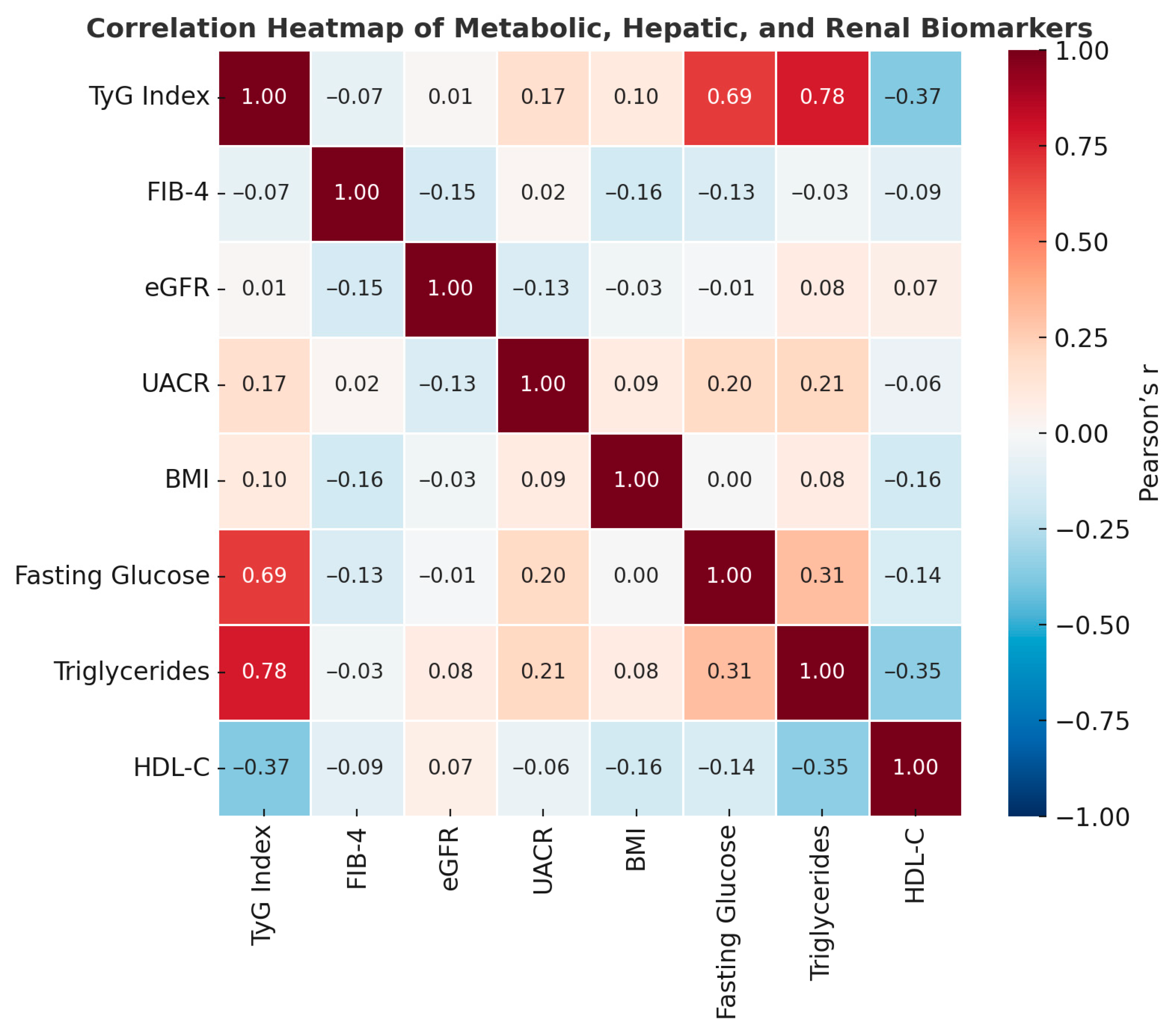

The strong correlations between TyG, triglycerides, and fasting glucose confirmed the robustness of TyG as a surrogate marker of insulin resistance. Its inverse association with HDL-C further emphasizes the dyslipidemic pattern characteristic of metabolic syndrome. Previous studies have established that elevated TyG values are closely linked to hepatic steatosis, arterial stiffness, and systemic inflammation, even among non-obese individuals [

10,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. The progressive rise in TyG observed across risk categories in our cohort supports its value as a sensitive marker for identifying early metabolic dysfunction [

22,

23,

24,

25].

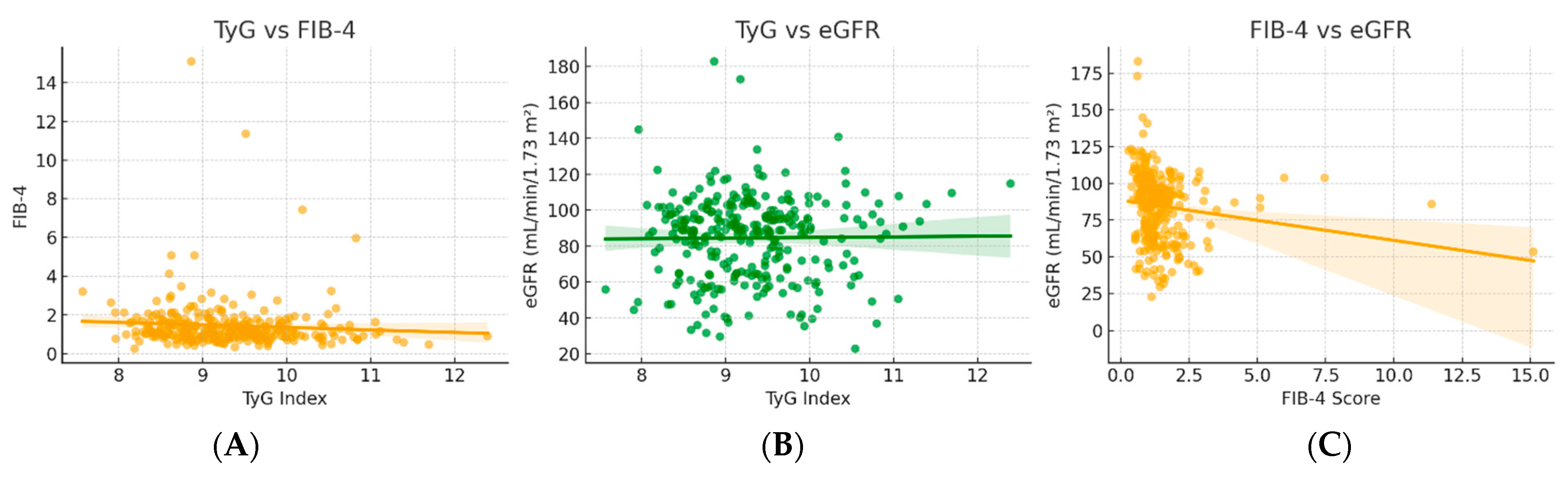

FIB-4 followed a similar pattern, rising significantly with increasing risk scores and correlating inversely with eGFR. This finding aligns with growing evidence of hepato–renal metabolic crosstalk, where hepatic stress and fibrotic remodeling accompany microvascular and renal dysfunction. Studies in metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) and diabetes cohorts have reported that higher FIB-4 scores predict a greater risk of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and cardiovascular complications [

11,

13,

26,

27,

28,

29]. In our model, FIB-4 independently predicted lower eGFR even after adjustment for age, blood pressure, and BMI, underscoring the systemic impact of hepatic dysfunction in metabolic disease progression.

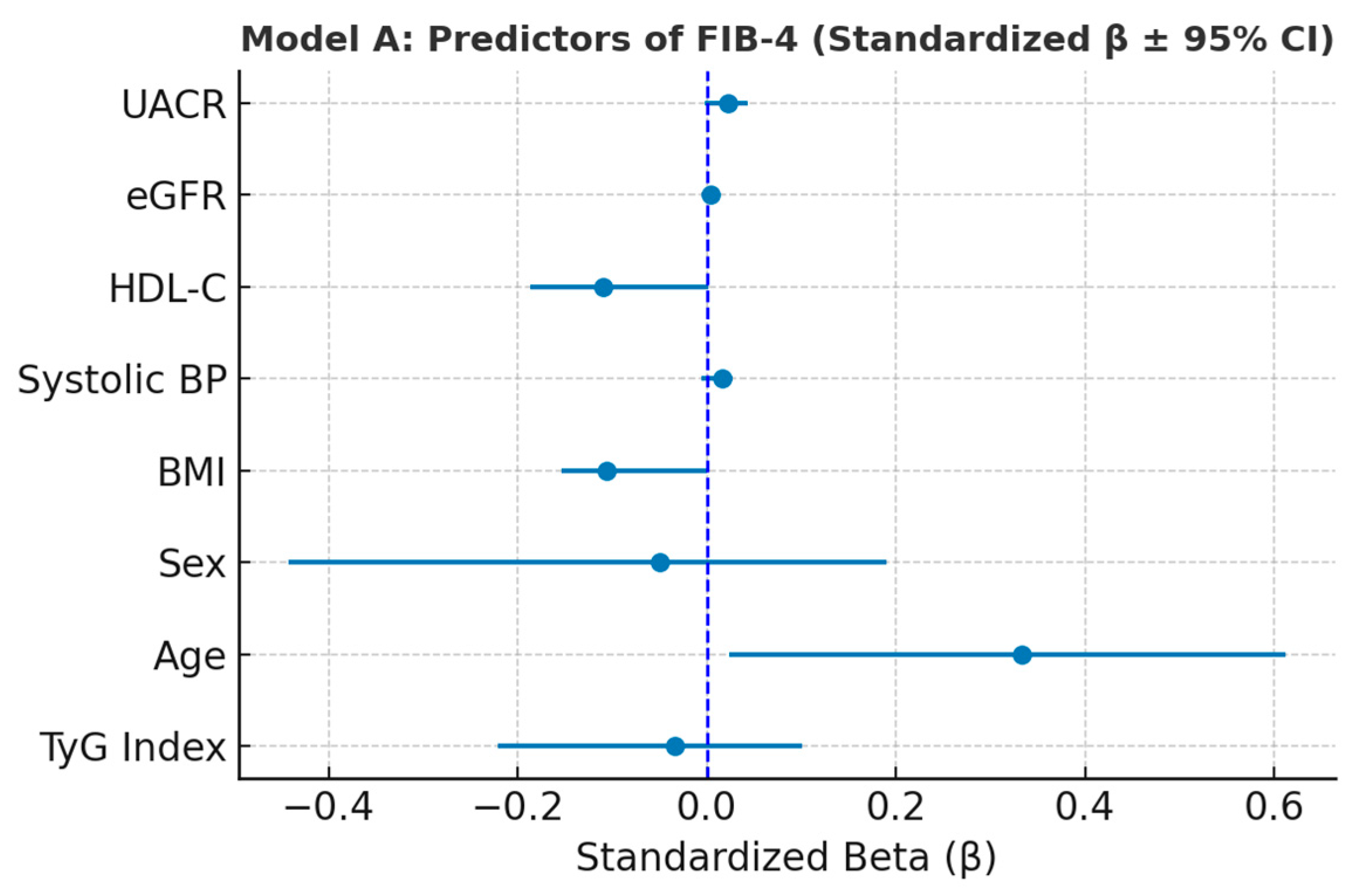

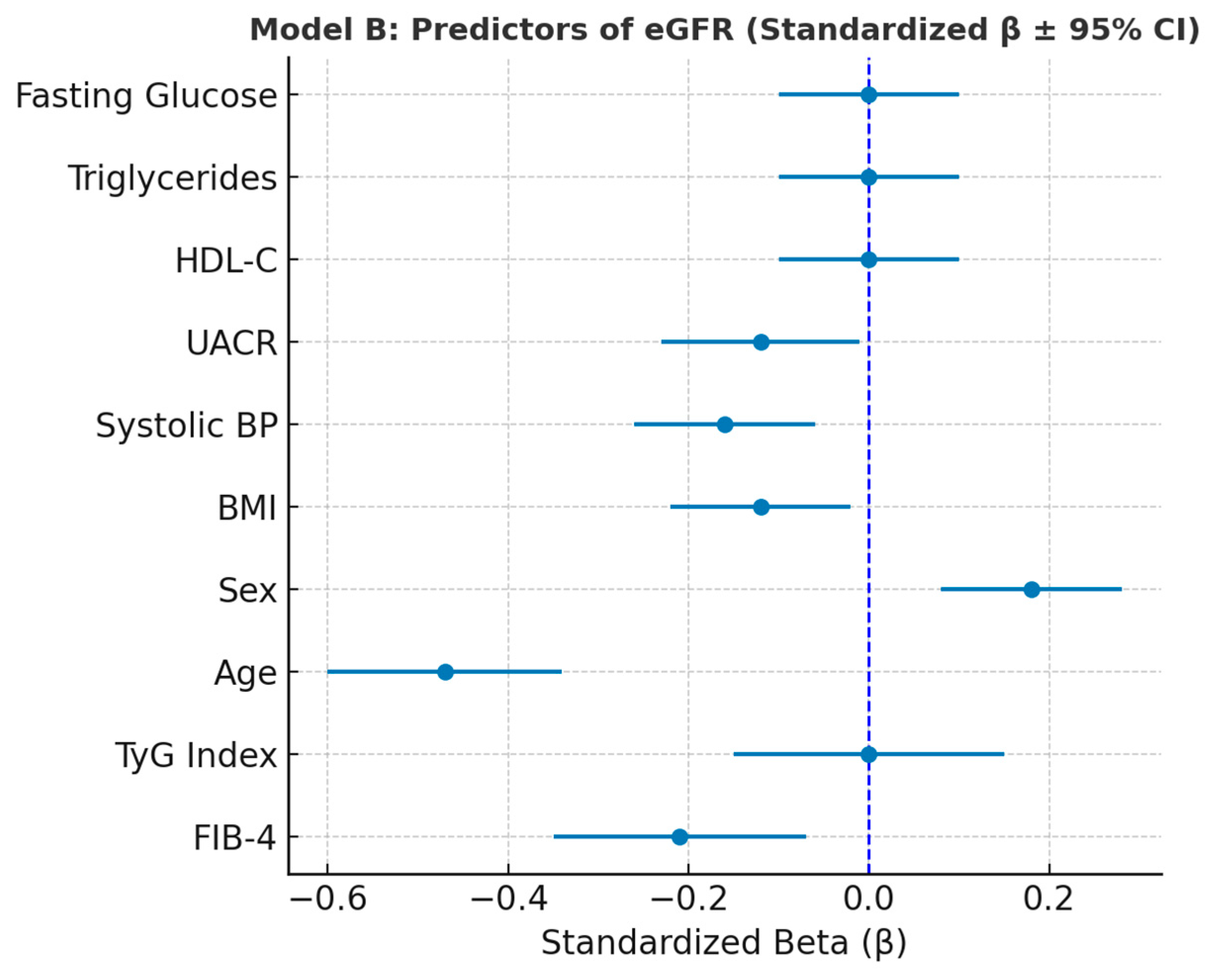

Multivariate regression analysis revealed age as the dominant determinant of both hepatic (FIB-4) and renal (eGFR) indices, consistent with physiological aging and cumulative metabolic stress. Systolic blood pressure, BMI, and UACR further contributed to eGFR decline, emphasizing the combined vascular and renal effects of metabolic load [

30]. Notably, TyG did not retain an independent association with eGFR or FIB-4 after adjustment, suggesting that insulin resistance exerts its effects indirectly through downstream mechanisms such as hypertension, hepatic injury, and microalbuminuria [

18].

These findings reinforce the concept of a metabolic–hepatic–renal continuum, where progressive insulin resistance initiates hepatic stress and fibrotic changes, followed by vascular and renal dysfunction. The integration of simple indices such as TyG, FIB-4, and eGFR provides a cost-effective strategy for early risk stratification in clinical and preventive settings.

Nevertheless, several limitations should be acknowledged. The cross-sectional design precludes causal inference, and residual confounding cannot be excluded. Additionally, liver fibrosis and renal function were assessed using surrogate indices rather than imaging or histological methods. Longitudinal studies with larger cohorts and mechanistic biomarkers (e.g., inflammatory cytokines, adipokines) are warranted to clarify the temporal relationships and underlying pathways connecting these organ systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S.P. and T.C.G.; methodology, A.M.; software, F.R.D.; validation, P.C.D., L.M. and F.M.; formal analysis, T.C.G.; investigation, T.C.G.; resources, M.S.P.; data curation, A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, T.C.G. and D.F.T.; writing—review and editing, T.C.G.; visualization, T.C.G.; supervision, F.M.; project administration, T.C.G.; funding acquisition, T.C.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by the University of Oradea, Oradea, Romania.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the University of Oradea (protocol code CEFMF/1 from 31 January 2023 and date of approval).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the University of Oradea for supporting the payment of the invoice through an internal project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ALT | Alanine aminotransferase |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| AST | Aspartate aminotransferase |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| BP | Blood pressure |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| CKD-EPI | Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration |

| eGFR | Estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| FIB-4 | Fibrosis-4 index |

| HDL-C | High-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| HC3 | Heteroscedasticity-consistent type 3 |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| MAFLD | Metabolic-associated fatty liver disease |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SBP | Systolic blood pressure |

| TG | Triglycerides |

| TyG | Triglyceride–glucose index |

| UACR | Urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio |

| VIF | Variance inflation factor |

References

- Dhondge, R.H.; Agrawal, S.; Patil, R.; Kadu, A.; Kothari, M. A comprehensive review of metabolic syndrome and its role in cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus: Mechanisms, risk factors, and management. Cureus 2024, 16, e67428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy-Matos, A.F.; Valério, C.M.; Júnior, W.S.S.; de Araujo-Neto, J.M.; Sposito, A.C.; Suassuna, J.H.R. Cardial-ms (cardio-renal-diabetes-liver-metabolic syndrome): A new proposition for an integrated multisystem metabolic disease. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2025, 17, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danciu, A.M.; Ghitea, T.C.; Bungau, A.F.; Vesa, C.M. The relationship between oxidative stress, selenium, and cumulative risk in metabolic syndrome. In Vivo 2023, 37, 2877–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroia, C.M.; Ghitea, T.C.; Vrânceanu, M.; Mureșan, M.; Bimbo-Szuhai, E.; Pallag, C.R.; Pallag, A. Relationship between vitamin d3 deficiency, metabolic syndrome and vdr, gc, and cyp2r1 gene polymorphisms. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghitea, T.C.; Vlad, S.; Bîrle, D.; Țiț, D.M.; Lazăr, L.; Nistor-Cseppento, D.C.; Behl, T.; Bungău, S. The influence of diet therapeutic intervention on the sarcopenic index of patients with metabolic syndrome. Acta Endocrinol. 2020, 16, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, S.; Zhou, X.; Fu, J. Noninvasive urinary biomarkers for obesity-related metabolic diseases: Diagnostic applications and future directions. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecoli, C.; Ait-Alì, L.; Storti, S.; Foffa, I. Circulating biomarkers in failing fontan circulation: Current evidence and future directions. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2025, 12, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giangregorio, F.; Mosconi, E.; Debellis, M.G.; Provini, S.; Esposito, C.; Garolfi, M.; Oraka, S.; Kaloudi, O.; Mustafazade, G.; Marin-Baselga, R. A systematic review of metabolic syndrome: Key correlated pathologies and non-invasive diagnostic approaches. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Wang, Y. The triglyceride–glucose index: A clinical tool to quantify insulin resistance as a metabolic myocardial remodeling bridge in atrial fibrillation. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamini, S.; Bondesan, A.; Caroli, D.; Marazzi, N.; Sartorio, A. The ability of the triglyceride-glucose (tyg) index and modified tyg indexes to predict the presence of metabolic-associated fatty liver disease and metabolic syndrome in a pediatric population with obesity. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumida, Y.; Yoneda, M.; Tokushige, K.; Kawanaka, M.; Fujii, H.; Yoneda, M.; Imajo, K.; Takahashi, H.; Eguchi, Y.; Ono, M.; et al. FIB-4 first in the diagnostic algorithm of metabolic-dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease in the era of the global metabodemic. Life 2021, 11, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haimi, M.; Baker, F.A.; Vinker, S.; Safadi, R.; Israel, A. Association between high fib-4 score and the risk of malignancy development and mortality: A retrospective longitudinal case–control study. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2025, 70, 3525–3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, T.; Watanabe, T.; Yamagami, H.; Miyataka, K.; Yasui, S.; Asai, T.; Kaneko, Y.; Mitsui, Y.; Masuda, S.; Kurahashi, K.; et al. Development of liver fibrosis represented by the fibrosis-4 index is a specific risk factor for tubular injury in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simental-Mendía, L.E.; Rodríguez-Morán, M.; Guerrero-Romero, F. The product of fasting glucose and triglycerides as surrogate for identifying insulin resistance in apparently healthy subjects. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 2008, 6, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterling, R.K. FIB-4: A simple, inexpensive and accurate marker of fibrosis in HCV-infected patients. Hepatology 2006, 44, 769–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levey, A.S.; Stevens, L.A.; Schmid, C.H.; Zhang, Y.; Castro III, A.F.; Feldman, H.I.; Kusek, J.W.; Eggers, P.; Van Lente, F.; Greene, T. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 150, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Chang, M.; Shen, P.; Wei, W.; Li, H.; Shen, G. Application value of triglyceride-glucose index and triglyceride-glucose body mass index in evaluating the degree of hepatic steatosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Lipids Health Dis. 2023, 22, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Li, C.; Fu, J.; Bai, L.; Wang, M.; Song, P.; Zheng, M. Association between the tyg index and mafld and its subtypes: A population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2025, 25, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Shen, C.; Kong, W.; Zhou, X.; Fan, H.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zheng, L. Association between the triglyceride glucose-body mass index and future cardiovascular disease risk in a population with cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome stage 0-3: A nationwide prospective cohort study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2024, 23, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Park, J.-Y.; Song, T.-J. Association between the triglyceride–glucose index and the incidence risk of heart failure: A nationwide cohort study. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2025, 35, 104127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Liu, C.; Wang, Y. The association between triglyceride-glucose index and the likelihood of cardiovascular disease in the U.S. Population of older adults aged ≥ 60 years: A population-based study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2024, 23, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Ji, H.; Sun, W.; An, X.; Lian, F. Triglyceride glucose (tyg) index: A promising biomarker for diagnosis and treatment of different diseases. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2025, 131, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y.; Li, P.; Sun, Z.; Murayama, R.; Li, Z.; Hashimoto, K.; Zhang, Y. Association of novel triglyceride-glucose-related indices with incident stroke in early-stage cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2025, 24, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagvajantsan, B.; Enebish, O.; Enkhtugs, K.; Dangaa, B.; Gantulga, M.; Ganbat, M.; Davaakhuu, N.; Tsedev-Ochir, T.-O.; Bayartsogt, B.; Yadamsuren, E.; et al. Blood pressure levels and triglyceride–glucose index: A cross-sectional study from a nationwide screening in mongolia. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; He, Z.; Wu, J.; Wu, J.; Liang, Y. Association between triglyceride glucose-waist-adjusted waist index and incident stroke in Chinese adults: A prospective cohort study. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1612864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleicher, E.M.; Gairing, S.J.; Galle, P.R.; Weinmann-Menke, J.; Schattenberg, J.M.; Kostev, K.; Labenz, C. A higher fib-4 index is associated with an increased incidence of renal failure in the general population. Hepatol. Commun. 2022, 6, 3505–3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaha, D.C.; Ilea, C.D.N.; Dorobanțu, F.R.; Pantiș, C.; Pop, O.N.; Dascal, D.G.; Dorobanțu, C.D.; Manole, F. The impact of SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on antibiotic prescriptions and resistance in a university hospital from romania. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seko, Y.; Yano, K.; Takahashi, A.; Okishio, S.; Kataoka, S.; Okuda, K.; Mizuno, N.; Takemura, M.; Taketani, H.; Umemura, A.; et al. Fib-4 index and diabetes mellitus are associated with chronic kidney disease in japanese patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagiannakis, D.S.; Stefanaki, K.; Petrea, F.; Zacharaki, P.; Giannou, A.; Michalopoulou, O.; Kazakou, P.; Psaltopoulou, T.; Vasileiou, V.; Paschou, S.A. Elevated fib-4 is associated with higher rates of cardiovascular disease and extrahepatic cancer history in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, H.; Asahara, S.I.; Nakamura, F.; Kido, Y. A high fibrosis-4 index is associated with a reduction in the estimated glomerular filtration rate in non-obese japanese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Kobe J. Med. Sci. 2024, 70, E39–E45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Relationship between urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) and metabolic parameters. Scatter plots illustrate weak positive associations between UACR and both fasting glycemia (blue) and triglycerides (dark red). Linear regression models (shown as black lines) indicate low but consistent trends (R2 = 0.044 and R2 = 0.041, respectively), suggesting that higher albuminuria is modestly associated with elevated glucose and lipid levels, reflecting early subclinical renal stress in metabolically impaired individuals.

Figure 2.

Correlation heatmap of metabolic, hepatic, and renal biomarkers. Pearson correlation coefficients illustrate strong positive associations between the TyG index, triglycerides, and fasting glucose, as well as moderate inverse relationships between FIB-4 and eGFR.

Figure 3.

Associations between insulin resistance (TyG) (A), hepatic fibrosis (FIB-4) (B), and renal function (eGFR) indices (C).

Figure 4.

Boxplots illustrating the distribution of TyG index, FIB-4 score, and eGFR across metabolic risk categories. TyG and FIB-4 values increase progressively with rising metabolic risk, indicating worsening insulin resistance and hepatic stress, whereas eGFR shows a mild, non-significant decline suggesting early subclinical renal involvement.

Figure 5.

Forest plot illustrating standardized regression coefficients (β ± 95% CI) for predictors of FIB-4 (Model A). Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) analysis confirmed the absence of multicollinearity among predictors included in Model A. All VIF values were below 1.6, well under the conventional threshold of 5, indicating that the independent variables contributed unique and non-redundant information to the model. These results validate the stability of the regression coefficients and support the reliability of the multivariate analysis (

Table 7).

Figure 6.

Forest plot showing standardized regression coefficients (β ± 95% CI) for predictors of eGFR (Model B).

Table 1.

Anthropometric and Metabolic Parameters.

| Parameter | Mean ± SD | Median | Min–Max |

|---|

| BMI (kg/m2) | 35.1 ± 4.6 | 34.0 | 30.0–54.1 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 111.1 ± 9.9 | 109 | 100–154 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 155.4 ± 56.1 | 139 | 69–407 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 42.4 ± 9.5 | 41 | 17–76 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 177.8 ± 152.8 | 137 | 51–1738 |

| TyG index | 9.29 ± 0.74 | 9.22 | 7.57–12.39 |

| FIB-4 score | 1.45 ± 1.30 | 1.19 | 0.27–15.11 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.86 ± 0.24 | 0.80 | 0.49–2.14 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 84.6 ± 23.3 | 89 | 23–183 |

| UACR (mg/g) | 28.4 ± 49.5 | 10.1 | 3.35–301.4 |

Table 2.

Sex-based Comparison (Mean Values).

| Parameter | Males | Females | Difference Trend |

|---|

| BMI | 34.7 | 35.6 | ≈similar |

| HDL-C | 39.6 | 45.2 | ↑ females |

| Triglycerides | 192.3 | 163.2 | ↑ males |

| TyG index | 9.38 | 9.20 | ↑ males |

| FIB-4 | 1.52 | 1.37 | ↑ males |

| eGFR | 81.9 | 87.1 | ↑ females |

Table 3.

Correlation matrix between metabolic, hepatic, and renal parameters in the study population.

| Relationship | Pearson r | Spearman ρ | Interpretation |

|---|

| TyG–Triglycerides | 0.78 | 0.90 | Very strong correlation (TyG includes TG in the formula) |

| TyG–Blood Glucose | 0.69 | 0.66 | Strong correlation → reflects insulin resistance |

| TyG–HDL-C | −0.37 | −0.37 | Inverse → lower HDL associated with insulin resistance |

| FIB-4–eGFR | −0.15 | −0.30 | Moderate inverse correlation → liver damage correlates with reduced kidney function |

| FIB-4–BMI | −0.16 | −0.19 | Weak, negative correlation → fibrosis more common in individuals with moderate BMI |

| UACR–Blood Glucose/TG | 0.20/0.21 | 0.08/0.09 | Tendency towards microalbuminuria in metabolic dysfunction |

Table 4.

Mean values of TyG index, FIB-4 score, and eGFR across metabolic risk categories.

| Risk Category | n | TyG Index (Mean ± SD) | FIB-4 (Mean ± SD) | eGFR (Mean ± SD) |

|---|

| 2 | 2 | 8.33 ± 0.11 | 0.89 ± 0.35 | 100.5 ± 2.1 |

| 3 | 13 | 8.32 ± 0.22 | 0.95 ± 0.33 | 100.6 ± 20.8 |

| 4 | 16 | 8.63 ± 0.44 | 1.23 ± 0.63 | 91.2 ± 33.6 |

| 5 | 44 | 8.80 ± 0.38 | 1.19 ± 0.50 | 83.8 ± 20.1 |

| 6 | 67 | 9.25 ± 0.64 | 1.14 ± 0.49 | 86.3 ± 21.6 |

| 7 | 81 | 9.53 ± 0.75 | 1.50 ± 1.67 | 84.0 ± 25.0 |

| 8 | 40 | 9.70 ± 0.60 | 1.58 ± 0.85 | 79.9 ± 21.4 |

| 9 | 16 | 9.76 ± 0.62 | 2.71 ± 2.47 | 76.2 ± 18.7 |

| 10 | 7 | 10.05 ± 0.46 | 3.37 ± 2.65 | 79.9 ± 26.0 |

Table 5.

Statistical comparison of TyG, FIB-4, and eGFR values across metabolic risk categories.

| Variable | ANOVA p-Value | Kruskal–Wallis p-Value | Significance |

|---|

| TyG index | 1.7 × 10−20 | 7.8 × 10−21 | significant differences (progressively increases with risk) |

| FIB-4 | 4.8 × 10−6 | 6.1 × 10−7 | significant (more advanced liver fibrosis at high risk) |

| eGFR | 0.15 | 0.13 | nonsignificant (decreasing trend with no clear differences) |

Table 6.

Multivariate linear regression coefficients for predictors of FIB-4 score (Model A).

| Variable | β (Unstandardized) | SE | βstd (Standardized) | p-Value | 95% CI (Lower) | 95% CI (Upper) |

|---|

| Constant | 1.323 | 0.974 | — | <0.001 | −0.586 | 3.233 |

| TyG index | −0.060 | 0.082 | −0.034 | <0.001 | −0.221 | 0.101 |

| Age | 0.039 | 0.008 | 0.333 | <0.001 | 0.024 | 0.054 |

| Sex (2 = female) | −0.126 | 0.161 | −0.049 | <0.001 | −0.442 | 0.190 |

| BMI | −0.030 | 0.015 | −0.106 | <0.001 | −0.059 | −0.000 |

| Systolic BP | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.017 | <0.001 | −0.005 | 0.007 |

| HDL-C | −0.015 | 0.008 | −0.109 | <0.001 | −0.031 | 0.002 |

| eGFR | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.004 | <0.001 | −0.005 | 0.005 |

| UACR | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.023 | <0.001 | −0.002 | 0.003 |

Table 8.

Multivariate linear regression coefficients for predictors of eGFR (Model B).

| Variable | β (Unstandardized) | SE | βstd (Standardized) | p-Value | 95% CI (Lower) | 95% CI (Upper) |

|---|

| Constant | 227.071 | 35.699 | 0.000 | <0.001 | 157.102 | 297.040 |

| TyG index | 0.075 | 0.913 | 0.004 | <0.001 | −1.714 | 1.864 |

| Age | −9.305 | 4.260 | −0.296 | <0.001 | −17.654 | −0.955 |

| Sex (2 = female) | −0.973 | 0.137 | −0.466 | <0.001 | −1.242 | −0.704 |

| BMI | 7.559 | 2.741 | 0.163 | <0.001 | 2.187 | 12.932 |

| Systolic BP | −0.588 | 0.274 | −0.117 | <0.001 | −1.124 | −0.051 |

| HDL-C | 0.024 | 0.061 | 0.021 | <0.001 | −0.097 | 0.144 |

| eGFR | −0.056 | 0.028 | −0.121 | <0.001 | −0.111 | −0.002 |

| UACR | −0.033 | 0.153 | −0.014 | <0.001 | −0.333 | 0.267 |

| Variable | 0.034 | 0.012 | 0.224 | <0.001 | 0.010 | 0.058 |

| Constant | 0.034 | 0.042 | 0.082 | <0.001 | −0.048 | 0.116 |

Table 9.

Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) for predictors included in the multivariate regression model for eGFR (Model B).

| Variable | VIF |

|---|

| FIB-4 | 1.20 |

| TyG index | 6.63 |

| Age | 1.44 |

| Sex | 1.16 |

| BMI | 1.18 |

| Systolic BP | 1.22 |

| UACR | 1.13 |

| HDL-C | 1.38 |

| Triglycerides | 3.74 |

| Fasting Glucose | 2.80 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).