Abstract

Background: Cardiac diseases remain one of the leading causes of death globally, often linked to ischemic conditions that can affect cellular homeostasis and metabolism, which can lead to the development of cardiovascular dysfunction. Considering the effect of ischemic cardiomyopathy on the global population, it is vital to understand the impact of ischemia on cardiac cells and how ischemic conditions change different cellular functions through post-translational modification of cellular proteins. Methods: To understand the cellular function and fine-tuning during stress, we established an ischemia model using neonatal rat ventricular cardiomyocytes. Further, the level of cellular acetylation was determined by Western blotting and affinity chromatography coupled with liquid chromatography–mass spectroscopy. Results: Our study found that the level of cellular acetylation significantly reduced during ischemic conditions compared to normoxic conditions. Further, in mass spectroscopy data, 179 acetylation sites were identified in the proteins in ischemic cardiomyocytes. Among them, acetylation at 121 proteins was downregulated, and 26 proteins were upregulated compared to the control groups. Differentially, acetylated proteins are mainly involved in cellular metabolism, sarcomere structure, and motor activity. Additionally, a protein enrichment study identified that the ischemic condition impacted two major biological pathways: the acetyl-CoA biosynthesis process from pyruvate and the tricarboxylic acid cycle by deacetylation of the associated proteins. Moreover, most differential acetylation was found in the protein pyruvate dehydrogenase complex. Conclusions: Understanding the differential acetylation of cellular protein during ischemia may help to protect against the harmful effect of ischemia on cellular metabolism and cytoskeleton organization. Additionally, our study can help to understand the fine-tuning of proteins at different sites during ischemia.

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular disease is one of the global leading causes of death. The most common behavioral risk factors for cardiovascular diseases include unhealthy lifestyles, lack of physical activity, smoking, and uncontrolled alcohol consumption [1]. Ischemic/coronary heart disease (IHD/CHD) can present as sudden cardiac death or acute myocardial infarction and is the most predominant of the cardiovascular diseases [2]. Ischemic heart disease occurs when blood flow [3] in the heart is restricted, often by the blockage of coronary arteries [4,5]. This can present clinically as a heart attack, arrhythmia, or heart failure [6]. Myocardial ischemia is primarily caused by atherosclerosis, which is plaque buildup on arterial walls that inhibits blood flow [5,6]. Blood flow carries oxygen to myocardial tissue, which is essential for the function of cardiac muscle fibers because they consume significant ATP [7]. Cardiomyocytes are rich in mitochondria that rely on aerobic metabolism for energy production and are therefore less efficient in utilizing anaerobic metabolic pathways during anoxic conditions, leaving them highly susceptible to ischemic conditions [8,9,10]. The search for therapeutic agents to act against ischemic heart disease can begin with the study of epigenomics [11]. Some CVD risk factors known to modify epigenetic markers are nutrition, smoking, pollution, stress, and the circadian rhythm [12,13]. Common epigenetic mechanisms include DNA methylation, histone modifications, and microRNA alterations, all of which enable the cell to respond to environmental changes [12]. They cause rearrangement of chromatin structure and accessibility of DNA without altering the DNA sequence, leading to modulation of the expression of certain genes [14]. Thus, epigenetics plays a critical role in the development of cardiovascular disease through post-translational modifications of DNA and regulation of gene expression [14]. Acetylation-mediated PTMs of protein were identified almost half a century ago and are evolutionarily conserved across species [15,16]. First, acetylation was identified in the histone protein, and then several cellular proteins were found to be acetylated [15]. Further study suggests that almost 70 percent of cellular acetylation was identified in the histone proteins [17]. Cells regulate histone protein acetylation via two classes of enzymes: lysine acyltransferases (KATs) and histone deacetylase (HDAC). Acetylation of histone protein regulates the chromatin structure and compactness and epigenetic regulation of gene expression [18]. Generally, it is found that acetylation causes the open configuration of chromatin, whereas deacetylation causes inhibition of transcription [19]. However, acetylation of cytoplasmic and mitochondrial proteins regulates the stability of proteins, enzyme activity, degradation of proteins, mitochondrial function, and cellular bioenergetics [20,21,22,23]. Acetylation of cardiac protein plays a critical role in cellular functions such as cardiac development, differentiation, sarcomere structure, and cellular metabolism [24,25,26,27,28]. Several studies previously identified the differential regulation of acetylation in cardiac proteins during disease conditions. For example, in cardiac hypertrophy, histone acetylation and deacetylation balance is dysregulated [29]. Further, studies have linked the role of HDAC with cardiac hypertrophy, and it was found that inhibition of HDAC is beneficial in reverse remodeling of the heart [30].

Here, we used an affinity-based quantitative mass spectroscopy method to identify the acetylation sites of the proteome during normoxia vs. ischemia using primary cardiomyocytes. Our study found that during ischemia, the level of total acetylation significantly reduced. Additionally, our study revealed that the acetylation of critical metabolic enzymes is altered during ischemia in cardiomyocytes.

2. Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

Neonatal Rat Primary Cardiomyocytes (NRVCs) were isolated from 1- to 2-day-old pups as described before [31]. In brief, left ventricular heart tissue was isolated from the neonatal rats and digested with trypsin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at 4 °C overnight. The next day, heart tissue was washed and digested with collagenase (Worthington Biochemical, Lakewood, NJ, USA). Cells were isolated from the digested heart tissue by differential plating. Cells were plated in the 100 mm culture disk (Genesee Scientific, San Diego, CA, USA) coated with collagen (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA). Initially, cells were grown in MEM media (Gibco, Waltham, MA, USA) with 10% FBS (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) and anti-anti (ThermoFisher) and then in DMEM (ThermoFisher) media with 2% FBS and penicillin–streptomycin (ThermoFisher).

2.2. Ischemic Conditions

The ischemic condition was created to replicate cardiac disease conditions in the heart, where cardiomyocytes have limited access to oxygen and blood. NRVCs in DMEM (ThermoFisher) media with 2% FBS (Sigma) were replaced with DMEM (ThermoFisher) media with no glucose and incubated in the hypoxia incubator (Eppendorf, Enfield, CT, USA). The hypoxic condition was created by 5% CO2, 0.1% O2, and N2 gas [32]. Cells were incubated in the hypoxic condition for 12 h at 37 °C. For the control experiment, cells were incubated in normoxic conditions created by DMEM media with high glucose (ThermoFisher), 2% FBS, and 5% CO2 at 37 °C for 12 h.

2.3. Cell Harvesting and Protein Isolation

Cardiomyocytes were grown in culture plates and washed twice with cold 1X PBS buffer. Then, cells were lysed by incubating them in 0.1% RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1% IGEPAL, 50 mM Tric-HCl pH 8.0, 12 mM sodium deoxycholate, and 0.1% SDS), 1X mammalian protease inhibitor (Sigma), and 1X deacetylase inhibitors (MedChemExpress, Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA) for 10 min [33]. The cells were dislodged after incubation by scraping the plates on ice and transferring them to 1.7 mL microcentrifuge tubes. Lysed cells in the RIPA buffer were vortexed until properly mixed. The microcentrifuge tubes were centrifuged at 10,000× g for 10 min at 4 °C to separate cell debris, and supernatants containing proteins were collected for the experiments. Protein estimation was performed using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (ThermoFisher). Standardized dilutions were created using a protein standard to make a standard curve and determine the protein concentrations of the test samples.

2.4. Western Blotting

For Western blotting, protein samples were diluted with 0.1% RIPA buffer mixed with the 1X Laemmli sample and stored at −20 °C for use in further experiments. Levels of acetylation in normoxic and ischemic protein samples were detected by Western blotting as described before [34]. In brief, proteins were resolved on SDS-PAGE with a protein ladder (Proteintech, Manchester, UK) and then transferred to the PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) by electrophoresis. Proteins were transferred to the PVDF membrane by wet transfer or a trans-blot turbo transfer (Bio-Rad) according to the manufactured protocol. To block the non-specific binding of antibodies, membranes were incubated in a blocking buffer (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE, USA) for an hour at room temperature. Then, the membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with the primary antibodies. After washing twice with 1X PBST and once with 1X PBS, the membrane was probed with IRDye secondary antibodies (LI-COR) for 2 h at room temperature. Blots were scanned using the Odyssey scanner (LI-COR). These images were then analyzed and quantified using Image Studio (LI-COR) to compare their expression levels on the membrane. The following antibodies were used for the assay: total acetylation antibody (Cell Signaling, Middletown, DE, USA, Cat # 9814S, 1:1000), H3K9 acetylation (Abcam, Waltham, MA, USA, Cat# C5B11, 1:2000), β-actin (Proteintech, Cat# 66009-1-Ig, 1:3000), and secondary antibody goat anti-rabbit 800, goat anti-mouse 680 (LI-COR, Cat# 926-68070, 926-32211, 1:5000).

2.5. Protein Digestion, Affinity Purification of Acetylated Proteins, and Mass Spectrometry

A mass spectroscopy experiment was conducted to detect total protein acetylation with the help of a proteomic core (Creative Proteomics, Shirley, NY, USA) [35]. For the mass spectroscopy analysis, NRVCs were cultured in normoxic and ischemic conditions as described before. Proteins from the cultured cells were isolated using RIPA buffer. To determine the protein acetylation sites, equal amounts of proteins were pulled together from three replicates in each condition, and 2 mg pull proteins were used for the study. Proteins from each condition were diluted to 2 mL of 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate buffer. The disulfide bridges of the protein were reduced by treatment with the 10 mM Tris (2-carboxyethyl) phosphine (TCEP), and reduced cysteine residues were alkylated by 20 mM iodoacetamide (IAA). Precipitated protein was collected by centrifugation, resuspended, and digested with trypsin at an enzyme–substrate ratio of 1:200 (w/w). After digestion, TFA was added to 1% final concentration, and digested peptides were precipitated by centrifugation at 1780 g for 15 min. The peptides were dried using SpeedVac. Protein PTMs are usually in low abundance, and thus, acetylated-peptide enrichment is essential for large-scale acetylation profiling. Acetyl-peptides were enriched through acetyl lysine antibody-conjugated agarose beads (PTMBIO, Chicago, IL, USA). Agarose beads were mixed, and 40 µL of 50% bead slurry was aliquoted in a 0.6 mL tube. Beads were washed thrice with chilled PBS by centrifugation at 1000× g at 4 °C. The 2 mg peptides were dissolved in NETN buffer (100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris-HCl, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, pH 8.0). The peptide solutions were centrifuged at 12,000× g for 10 min at 4 °C to remove possible precipitates. Peptide solutions were mixed with the conjugated beads at 4 °C for 4 h with gentle shaking. Beads were washed four times with NETN buffer and twice with deionized water. Bound peptides were eluted with 1% trifluoroacetic acid. For the separation of peptides, Nanoflow UPLC (ThermoFisher Scientific), a trapping column (PepMap C18, 100 Å, 100 μm × 2 cm, 5 μm), and an analytical column (PepMap C18, 100 Å, 75 μm × 50 cm, 2 μm) were used with following conditions at a total flow rate of 250 nL/min: Mobile phase: A: 0.1% formic acid in water; B: 0.1% formic acid in 80% acetonitrile. LC linear gradient: from 2 to 8% buffer B in 3 min, from 8% to 20% buffer B in 50 min, from 20% to 40% buffer B in 26 min, and then from 40% to 90% buffer B in 4 min. The full mass spectroscopy scan was performed between 300 and 1650 m/z at the resolution 60,000 at 200 m/z, and the automatic gain control target for the full scan was set to 3 × 106 The MS/MS scan was operated in Top 20 mode using the following settings: resolution 15,000 at 200 m/z; automatic gain control target 1e5; maximum injection time 19 ms; normalized collision energy at 28%; and isolation window of 1.4. The charge state exclusion was as follows: unassigned, 1, >6; dynamic exclusion 30 s. The raw MS files were analyzed using the protein database Maxquant (1.6.3.4) and searched against Rattus norvegicus. The following parameters were set during the search: carbamidomethylation (C), oxidation (M) (variables), acetyl (K) (variables), and acetyl (N-term) (variables); the enzyme specificity was set to trypsin; the maximum missed cleavages were set to 5; the precursor ion mass tolerance was set to 10 ppm; and MS/MS tolerance was 0.6 Da.

3. Bioinformatics Analysis

The UniProt (https://www.uniprot.org, accessed on 10 December 2021) protein database was used to annotate identified proteins’ functions in the MS experiment. For the functional enrichment analysis of the identified proteins, a GO/KEGG functional annotation tool of ShinyGO 0.77 (http://bioinformatics.sdstate.edu/go77/ accessed on 8 December 2021) was used against the Rattus Norvegicus. For motif analysis of the identified acetylation sites of the protein sequence (amino acid), a probability Logo Generator for Biological Sequence (pLogo) from SchwartZLab was used. The protein database of Rattus Norvegicus was used as a background parameter. The identified acetylated proteins were searched using the STRING v11 database for protein–protein network analysis. Subcellular localization of the identified proteins was searched using UniProt software accessed in January 2022).

4. Statistical Data Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad version 9.0 software. The results were presented as a mean ± standard deviation. For statistical significance analysis between groups, an unpaired Student t-test was performed. * p < 0.05 is considered a significant change between the groups.

5. Results

5.1. Ischemic Condition Significantly Reduces the Cellular Acetylation Level

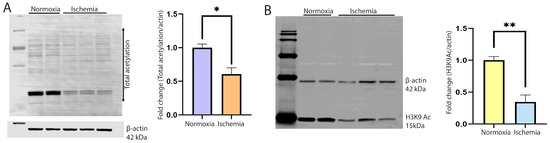

To monitor the changes in cellular acetylation, NRVCs were grown in no glucose and serum-free media in an ischemic condition created by reducing the oxygen level to 0.1% for 12 h at 37 °C. Control cells as a normoxia were grown in high glucose DMEM media having 2% FBS. Total proteins were isolated, and Western blots were performed with the total acetylation antibody. Our data found that the level of total acetylation in the ischemic NRVCs significantly decreased compared to the normoxic condition (Figure 1A). The published literature showed that histones are the main target of acetylation in the cells; we also detected the level of histone protein acetylation by Western blot. We used the H3K9ac antibody to detect the level of histone acetylation at lysine 9. Interestingly, we found that consistent with the total acetylation level, the level of H3K9 acetylation also significantly decreased (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Cellular acetylation is significantly reduced during ischemia. (A) Western blot shows the total acetylation of the cardiomyocytes during normoxia and ischemia. NRVCs were exposed to ischemic conditions for 12 h, and a Western blot was performed with the total acetylation antibody. β-actin was used as an internal loading control. The graph shows the quantification of the Western blot (* p < 0.05) (B). The Western blot shows the acetylation of histone protein. The blot was probed with the H3K9ac antibody. The graph shows the quantification of the Western blot (** p < 0.05).

5.2. Identification of Differentially Acetylated Positions in Proteins

As our Western blot data showed that acetylation levels significantly reduced during ischemia, we are further interested in the identification of the acetylation sites of the cellular proteins. Additionally, we performed a quantitative analysis of protein acetylation to understand how ischemia modulates protein acetylation (Supplementary Figure S1). Acetylated proteins were affinity purified using acetylation affinity beads of the digested proteins. The acetylation levels of purified proteins were determined by acetyl-proteomics using mass spectrometry. Based on the mass spectroscopy data, the differentially acetylated proteins in ischemic conditions were identified (Table 1). In this experiment, a total of 179 acetylation sites were identified (Table 1). The acetylation quantification showed that acetylation at 26 sites was upregulated (UP), as determined by a fold change greater than 1.5. There are 121 sites that are downregulated (DOWN), determined by a fold change of less than 1/1.5. There are 30 sites where it was unable to be determined if acetylation was upregulated or downregulated, labeled no change (NC). Additionally, we determined the function of identified proteins using the UniProt (https://www.uniprot.org) database (Table 2).

Table 1.

List of acetylated proteins identified in mass spectroscopy.

Table 2.

Functional annotations of genes.

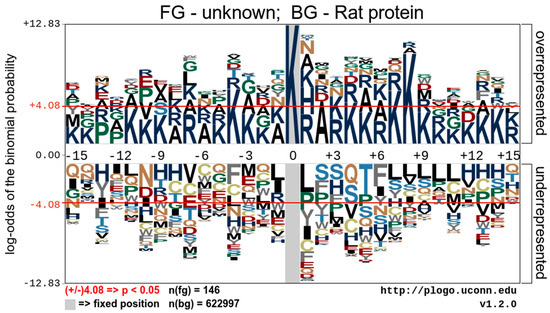

5.3. Sequence Motifs of Lysine Acetylation Sites

To understand the regulation of protein acetylation and identify the occupancy frequency of the surrounding amino acids of the identified proteins’ acetylation sites, we visualized the Kac protein motifs using the pLogo bioinformatic tool. The data show an overrepresentation of lysine at positions −4, 4, 7, and 8 relative to the acetylated lysine. It also contains an overrepresentation of alanine at position 2 relative to the acetylated lysine. There were no statistically significant underrepresented sequence motifs (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Analysis of the acetylation motifs of acetylated peptides identified by mass spectroscopy. A representative image shows the overrepresented and underrepresented amino acid residues surrounding acetylated lysine.

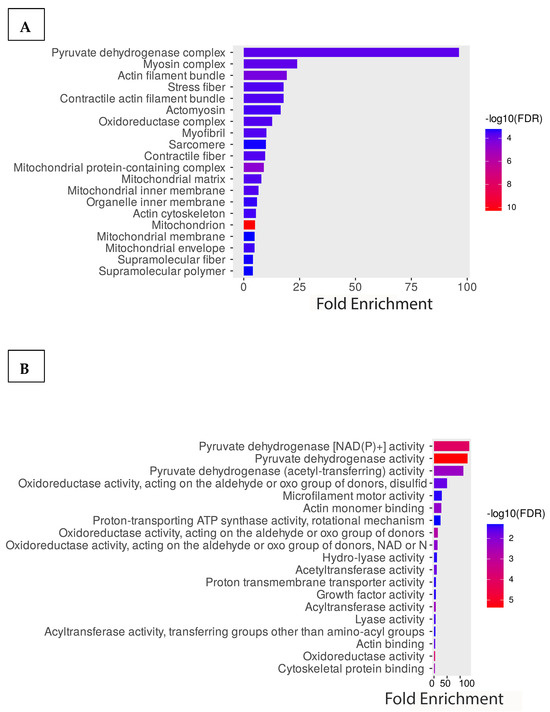

5.4. Functional Enrichment Analysis of the Acetylated Proteins

To better understand the acetylome of cardiomyocytes, we performed GO enrichment analysis of all identified proteins based on biological processes, molecular functions, and cellular components. The graph below illustrates the percentage of genes out of all the differentially associated proteins that are associated with a particular cellular component compared to the baseline percentage of genes in the background. The result indicated that the cellular component containing the highest comparative number of differentially acetylated genes is the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (Figure 3A). Additionally, cellular contractile proteins like myosin, actin, and stress fibers are enriched. Consistent with the cellular component result, the molecular function is also enriched with the metabolic enzymes involved in pyruvate dehydrogenase activity. Other enriched proteins belong to the category of oxidoreductase and motor activity of the cells (Figure 3B). Further enrichment analysis of the biological processes shows that most enriched proteins are involved in acetyl-CoA biosynthesis from pyruvate, the tricarboxylic acid cycle, and muscle tissue morphogenesis. Based on the significance, the highest enriched groups in the biological process are involved in cellular respiration (Figure 3C). Additionally, we performed an enrichment analysis of the identified protein using the KEGG pathways. Interestingly, consistent with the GO molecular functional analysis, highly enriched proteins are involved with cellular metabolic pathways such as the TCA, glyoxylate metabolism, carbon metabolism, pyruvate metabolism, and cardiac muscle contraction (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

Functional enrichment analysis of the acetylated proteins. GO enrichment analysis of the proteins is based on (A) cellular components, (B) molecular functions, and (C) biological processes. (D) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of the proteins.

We also used UniProt software to determine the identified protein’s subcellular localization in the cell. Our analysis showed that acetylated proteins are localized all over the cell, including the cytoplasm, cytoskeleton, endoplasmic reticulum, extracellular region, cell membrane, mitochondria, nucleus, ribosome, and peroxisome. However, most proteins are localized in mitochondria, the nucleus, and the cytoplasm (Supplementary Figure S2).

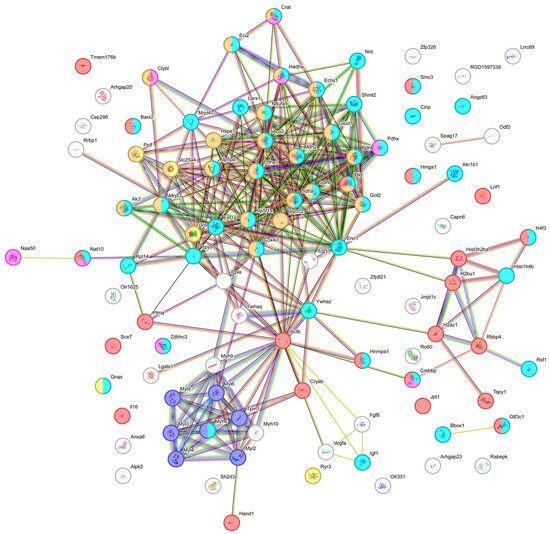

5.5. String Protein Web

A STRING protein web highlights the primary functions of acetylated proteins, indicating the groupings of physiological processes affected by lysine PTM. Many differentially acetylated proteins are connected with cellular metabolism, and this cluster of proteins was labeled cyan. The mitochondrial proteins labeled as brown are heavily involved in the transport of electrons and ATP synthesis, and they are critical in the process of oxidative phosphorylation. Ischemic conditions affecting these processes result in mitochondrial dysfunction and the development of disease conditions such as cardiovascular disease, stroke, etc. The cluster of proteins labeled in purple, such as the myosin regulatory light polypeptides 2, 3, 4, 6, and 9, plays a primary role in striated muscle contraction by regulating the movement of myosin head molecules for cross-bridge formation. These proteins are connected and primarily affect myosin 6, tropomyosin alpha-1 chain, and actin. Actin has key functions in cell motility and contraction in the cytoplasmic cytoskeleton. In addition, G- and F-actin regulate gene transcription, motility, and the repair of damaged DNA by localizing in the nucleus. Another grouping of deferentially acetylated nuclear proteins included histone cluster 1 H1 family member d, Histone H4-like protein, Histone H2A.Z variant, and Histone 2B. These proteins labeled red provide structural support for the chromatin and are also connected to RB-binding protein 4 and remodeling and spacing factor 1, which modulate chromatin organization and remodeling (Figure 4). The calcium and muscle contraction regulatory proteins were labeled as yellow. We also identified proteins involved in acyltransferase activity, such as Nat10 and Crebbp, which were labeled pink.

Figure 4.

STRING protein web grouping showing the primary functions of differentially acetylated proteins.

The functional importance of identified acetylated proteins in the heart is as follows:

Recently, the post-translational modifications of cellular proteins have received special attention due to the multiple roles they play in regulating cellular functions. Acetylation of cardiac proteins regulates several cellular functions, including gene expression, mitochondrial energy homeostasis, calcium homeostasis and calcium sequestration, cellular metabolism, cellular protein degradation and stability, signal transduction, and cardiac contractility [24,36]. Mitochondrial function: Our study identified several mitochondrial proteins that are differentially regulated during ischemia (Table 1). Studies suggest that hyperacetylation of mitochondrial proteins reduces cardiac energetics and promotes the development of oxidative stress and pathophysiological conditions. One of the critical enzymes enriched in the proteomic study is the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDH). Its acetylation during ischemic conditions significantly increased. PDH is an important enzyme that connects glycolysis to the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle pathway through the conversion of pyruvate to acetyl-CoA. Previous studies showed that increased acetylation compromises the enzyme activity of PDH and decreases the cellular acetyl-CoA level [37,38]. ATP5f1c is another mitochondrial protein found to be hyperacetylated in our study. ATP5f1c is a mitochondrial ATP synthase that generates ATP during oxidative phosphorylation. Studies suggest that hyperacetylation of this enzyme interferes with enzyme activity and induces metabolic dysfunction and senescence in the cardiac cells [39].

Gene regulation and transcription: Further, acetylation of nuclear proteins plays an important role in chromatin structure and gene expression, stress response of cells, and development of cardiac disease. Our study identified several acetylated nuclear proteins, including histones (Table 1). We found that acetylation of histones significantly decreased during ischemia. Also, we have identified a cytidine acetyltransferase Nat10, which was hyperacetylated during ischemia. Nat10 plays a critical role in the regulation of Ac4C-mediated epigenetic regulation of mRNAs [40,41]. A study with a mouse model found that knockdown of Nat10 induces cardiomyocyte apoptosis and heart failure [42]. Further, it was found that Ac4C-mediated modification of mRNA enhances the stability of cellular protein BCL-XL, which promotes myocardial infarction-induced cardiac fibrosis development [43]. Furthermore, it was found that Nat10 can undergo autoacetylation, which is important for its activity [44]. Additionally, Nat10 plays a critical role during cellular energy stress through the regulation of cellular rRNA synthesis and autophagy to maintain cellular energy supply [45].

Metabolism: Growing evidence also suggests that acetylation of a cellular protein is critical for cardiac metabolism and energy balance. Metabolic enzymes involved in fatty acid oxidation and glucose metabolism are known to be acetylated. Our study found that several metabolic proteins involved in glycolysis, the TCA cycle, and fatty acid oxidation were differentially acetylated (Table 1). One of the metabolic enzymes found to be acetylated in ischemic conditions is insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1). IGF-1 plays a critical role in cardiovascular function through the regulation of cellular metabolism, development, cellular contractility, and heart function by regulating insulin levels, insulin sensitivity, and glucose metabolism [46,47]. Decreased expression of IGF-1 during myocardial infarction was linked with a worse prognosis [48]. Interestingly, it was found that the metabolic status of the heart can regulate the acetylation of IGF-1 [46]. Further, it was evident that IGF-1 regulates metabolic enzymes ENO2 and SIRT1 via their acetylation and cellular transcription by histone 3 and histone 4 acetylation [49].

Sarcomeric proteins and contractility: Acetylation also plays a critical role in the regulation of cellular contractility through calcium homeostasis [50,51]. In our study, we found that several sarcomeric proteins such as myosin, actin, and tropomyosin become acetylated. Studies suggested that acetylation of sarcomeric proteins plays a significant role in the stiffness of the sarcomere [52]. It was found that acetylation of sarcomeric protein titin causes less muscle stiffness, and HDAC6 can cause more titin stiffness, which can impact heart function [53]. Additionally, it was found that acetylation of myosin modulates its enzyme activity as well as motor function. We also detected the acetylation of the RyR3 protein at the divergent region 1 (DR1). DR1 region plays a critical role in the regulation of calcium homeostasis in the sarcoplasmic reticulum and actomyosin movement of the sarcomere [54,55]. We also detected actin acetylation in the cardiomyocytes. It was found that lysine acetylation of the actin protein can decrease the tropomyosin-mediated regulation of actomyosin activity [56].

Stress response: Acetylation also plays an important role in the stress response, protein folding, stability, and degradation of cardiac cells. One of the stress-induced proteins, TCP, was found to be acetylated in the ischemic cells. TCP plays a critical role in folding several cellular proteins, including myosin, actin, and tubulin [57]. Knockdown of the TCP protein can impact heart function [57]. Additionally, it was demonstrated that acetylation of TCP significantly increased during heat shock [58].

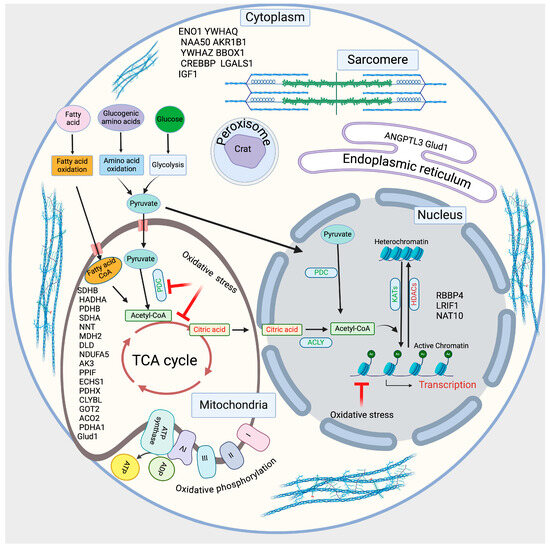

Additionally, we drew a schematic diagram based on the acetylated proteins identified in our study, which are involved in cellular metabolism, acetylation of cellular proteins, mitochondrial function, gene regulation, and sarcomere functions (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The schematic diagram shows the identified acetylated proteins involved in regulating cellular metabolism and acetylation.

6. Discussion

Acetylation of lysine is a conserved post-translation protein modification, which plays many important roles, including those involved in gene transcription, cellular metabolism, and cell survival via altering the function of proteins [42,43,44,45,46,59,60,61,62,63,64,65]. The current study aims to identify proteins that have been differentially acetylated due to ischemic conditions and analyze what biological pathways are the most impacted. The results show that 179 proteins were differentially modified due to post-translational modification by acetylation during ischemia. Bioinformatics analysis indicates that these acetylated changes are found to be localized in different subcellular organelles like mitochondria, nucleus, cytoplasm, etc. Protein enrichment analysis revealed that post-translationally modified proteins are involved in various cellular functions, such as protein synthesis, epigenetic modification, and metabolism. Our study identified major biological pathways that may be impacted by ischemic conditions, such as the acetyl-coA biosynthetic process from pyruvate, the tricarboxylic acid cycle, and ventricular cardiac muscle tissue morphogenesis. The cellular processes most impacted (pyruvate dehydrogenase complex) and molecular functions most impacted (pyruvate dehydrogenase NADP+ activity) were also identified. The pyruvate dehydrogenase complex catalyzes the oxidative decarboxylation of pyruvate to form acetyl CoA [66]. It plays a major role in aerobic respiration as the essential link between glycolysis (anaerobic metabolism) and the tricarboxylic acid cycle [66].

Dysregulated acetylation and hyperactivity of lysine deacetylase (KDAC) enzymes are involved in cardiac dysfunction, and many other proteins may have similar effects. It is known that ischemic/reperfusion (I/R)-induced tissue injury can cause deacetylation through HDAC. The HDAC class of proteins removes acetyl groups from histones and non-histone proteins, which regulates the chromatin structure that turns off gene expression [67]. Dysregulated acetylation is identified in Figure 1 of this study, as total acetylation is significantly decreased in ischemic conditions. HDAC inhibitors have been reported to show beneficial outcomes for cardiac arrhythmia, cardiac fibrosis, cardiac hypertrophy, and myocardial infarction. Trichostatin A is a pan-HDAC inhibitor, which inhibits Class I and Class II HDACs and has been shown to decrease the gene expression levels of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) protein and the genes that it targets [67]. This signaling can promote cell survival, reduce vascular permeability, and ultimately reduce myocardial injury [67]. H3K9 acetylation plays a critical role in the regulation of transcription initiation. Studies suggest that H3K9 acetylation acts as a substrate of the super elongation complex (SEC) on chromatin. This complex formation promoted the pol II pause release and progression of the transcription cycle. In our study, H3K9 acetylation significantly decreased in ischemic conditions (Figure 1).

7. Future Perspectives

Increasing evidence shows that acetylation-mediated post-translational modification of cardiac proteins plays an important role in the cellular metabolism and development of CVDs. In the past, advancements have been made to identify the acetylation of proteins and their role in CVD. Our acetylome study provides a comprehensive understanding of the acetylation of proteins and its regulation during ischemia. Organizing and categorizing differentially acetylated proteins can be useful in identifying new potential targets for epigenetic-based therapy of ischemic heart disease. Combining the use of epidrugs with conventional therapy has been newly identified as beneficial in the treatment of patients with heart failure [68]. Currently, there are some drugs on the market that take advantage of the reversible nature of epigenetic-sensitive changes, such as vorinostat (Zolinza), belinostat (Beleodaq), romidepsin (Istodax), and panobinostat (Farydak), which all function as histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACis) [69]. In our study, we found that many mitochondrial proteins become acetylated during ischemia. Additionally, to our knowledge, we identified the acetylation of RyR3 for the first time. However, the role of acetylation in the DR1 in the regulation of cardiac calcium homeostasis and contractility is not clear. Therefore, more studies are needed to investigate the regulation of organ-specific acetylation, specifically the mitochondrial proteins, to modulate cardiac energy homeostasis.

8. Conclusions

PTMs play a critical role in the regulation of cardiac function, metabolism, and epigenetic regulation through the regulation of enzyme activity, its stability, and its localization. Our study identified several known and unknown acetylation sites in several cardiomyocyte proteins. Further studies are needed to explore the role of each identified acetylation of proteins and its connection to the cellular protein function, substrate binding, and localization. Additionally, by modulating the protein acetylation, it may be possible to alter cardiac energy status during disease conditions and improve CVDs. This study was limited due to time constraints and the availability of resources. However, given more time, specific proteins can be further explored to see how the changes in acetylation impact the protein’s stability and enzymatic activity and can provide a new drug target for CVDs.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/metabo14120701/s1, Figure S1: Experimental Workflows, and Figure S2: The pie chart shows the relative distribution of the acetylated proteins identified by mass spectroscopy in percentage.

Author Contributions

M.K.G., A.R., S.N., N.F., G.O., E.L.-N. and O.K. performed the experiments and analyzed the data, and M.K.G. wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant (1R01HL141045-01A1).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Central Florida (IPROTO202300054; approved on 25 April 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The material and data associated with the work will be available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the present and past Gupta lab members for their generous help with the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bays, H.E.; Taub, P.R.; Epstein, E.; Michos, E.D.; Ferraro, R.A.; Bailey, A.L.; Kelli, H.M.; Ferdinand, K.C.; Echols, M.R.; Weintraub, H.; et al. Ten things to know about ten cardiovascular disease risk factors. Am. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2021, 5, 100149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.A.; Hashim, M.J.; Mustafa, H.; Baniyas, M.Y.; Suwaidi, S.K.B.M.A.; AlKatheeri, R.; Alblooshi, F.M.K.; Almatrooshi, M.E.A.H.; Alzaabi, M.E.H.; Darmaki, R.S.A.; et al. Global Epidemiology of Ischemic Heart Disease: Results from the Global Burden of Disease Study. Cureus 2020, 12, e9349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswas, T.; Townsend, N.; Das Gupta, R.; Ghosh, A.; Rawal, L.B.; Mørkrid, K.; Mamun, A. Clustering of metabolic and behavioural risk factors for cardiovascular diseases among the adult population in South and Southeast Asia: Findings from WHO STEPS data. Lancet Reg. Health Southeast Asia 2023, 12, 100164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, P.; Theroux, P. Pathophysiology of coronary artery disease. Circulation 2005, 111, 3481–3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lusis, A.J. Atherosclerosis. Nature 2000, 407, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, C.; Wang, J.; Tian, J.; Tang, Y.-D. Coronary Artery Disease: From Mechanism to Clinical Practice. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020, 1177, 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Boyette, L.C.; Manna, B. Physiology, Myocardial Oxygen Demand. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zuurbier, C.J.; Bertrand, L.; Beauloye, C.R.; Andreadou, I.; Ruiz-Meana, M.; Jespersen, N.R.; Kula-Alwar, D.; Prag, H.A.; Eric Botker, H.; Dambrova, M.; et al. Cardiac metabolism as a driver and therapeutic target of myocardial infarction. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 5937–5954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glatz, J.F.; Zuurbier, C.J.; Larsen, T.S. Targeting metabolic pathways to treat cardiovascular diseases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Mol. Basis Dis. 2020, 1866, 165879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solaini, G.; Harris, D.A. Biochemical dysfunction in heart mitochondria exposed to ischaemia and reperfusion. Biochem. J. 2005, 390, 377–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.K. Therapeutic potential of epigenetic drugs. In Epigenetics in Human Disease; Elsevier: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024; pp. 761–778. [Google Scholar]

- Ordovás, J.M.; Smith, C.E. Epigenetics and cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2010, 7, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, N.W.S.; Loong, S.S.E.; Foo, R. Epigenetics in cardiovascular health and disease. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2023, 197, 105–134. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Soler-Botija, C.; Gálvez-Montón, C.; Bayés-Genís, A. Epigenetic Biomarkers in Cardiovascular Diseases. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gershey, E.L.; Vidali, G.; Allfrey, V.G. Chemical studies of histone acetylation. The occurrence of epsilon-N-acetyllysine in the f2a1 histone. J. Biol. Chem. 1968, 243, 5018–5022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Guo, L.; Fu, Y.; Huo, M.; Qi, Q.; Zhao, G. Bacterial protein acetylation and its role in cellular physiology and metabolic regulation. Biotechnol. Adv. 2021, 53, 107842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, B.K.; Gupta, R.; Baldus, L.; Lyon, D.; Narita, T.; Lammers, M.; Choudhary, C.; Weinert, B.T. Analysis of human acetylation stoichiometry defines mechanistic constraints on protein regulation. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannister, A.J.; Kouzarides, T. Regulation of chromatin by histone modifications. Cell Res. 2011, 21, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterner, D.E.; Berger, S.L. Acetylation of Histones and Transcription-Related Factors. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2000, 64, 435–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeza, J.; Smallegan, M.J.; Denu, J.M. Mechanisms and Dynamics of Protein Acetylation in Mitochondria. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2016, 41, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrico, C.; Meyer, J.G.; He, W.; Gibson, B.W.; Verdin, E. The Mitochondrial Acylome Emerges: Proteomics, Regulation by Sirtuins, and Metabolic and Disease Implications. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 497–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varland, S.; Silva, R.D.; Kjosås, I.; Faustino, A.; Bogaert, A.; Billmann, M.; Boukhatmi, H.; Kellen, B.; Costanzo, M.; Drazic, A.; et al. N-terminal acetylation shields proteins from degradation and promotes age-dependent motility and longevity. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Guan, K.-L. Mechanistic insights into the regulation of metabolic enzymes by acetylation. J. Cell Biol. 2012, 198, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.-F.; Tang, X. Acylations in cardiovascular biology and diseases, what’s beyond acetylation. EBioMedicine 2022, 87, 104418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-F.; Tang, W.W. Epigenetics in Cardiac Hypertrophy and Heart Failure. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 2019, 4, 976–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, R.; Zhang, L. Cardiac ECM: Its Epigenetic Regulation and Role in Heart Development and Repair. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilsbach, R.; Schwaderer, M.; Preissl, S.; Grüning, B.A.; Kranzhöfer, D.; Schneider, P.; Nührenberg, T.G.; Mulero-Navarro, S.; Weichenhan, D.; Braun, C.; et al. Distinct epigenetic programs regulate cardiac myocyte development and disease in the human heart in vivo. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nural-Guvener, H.F.; Zakharova, L.; Nimlos, J.; Popovic, S.; Mastroeni, D.; Gaballa, M.A. HDAC class I inhibitor, Mocetinostat, reverses cardiac fibrosis in heart failure and diminishes CD90+ cardiac myofibroblast activation. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair 2014, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funamoto, M.; Imanishi, M.; Tsuchiya, K.; Ikeda, Y. Roles of histone acetylation sites in cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1133611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Nie, J.; Wang, D.W.; Ni, L. Mechanism of histone deacetylases in cardiac hypertrophy and its therapeutic inhibitors. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 931475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, S.; Rabbani, M.; de Lima, I.; Kondrachuk, O.; Patel, R.; Shafiei, M.S.; Mukker, A.; Rajakumar, A.; Gupta, M.K. HOPX Plays a Critical Role in Antiretroviral Drugs Induced Epigenetic Modification and Cardiac Hypertrophy. Cells 2021, 10, 3458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Ito, H.; Adachi, S.; Akimoto, H.; Nishikawa, T.; Kasajima, T.; Marumo, F.; Hiroe, M. Hypoxia induces apoptosis with enhanced expression of Fas antigen messenger RNA in cultured neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. Circ. Res. 1994, 75, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.K.; Gulick, J.; Liu, R.; Wang, X.; Molkentin, J.D.; Robbins, J. Sumo E2 Enzyme UBC9 Is Required for Efficient Protein Quality Control in Cardiomyocytes. Circ. Res. 2014, 115, 721–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randhawa, P.K.; Rajakumar, A.; de Lima, I.B.F.; Gupta, M.K. Eugenol attenuates ischemia-mediated oxidative stress in cardiomyocytes via acetylation of histone at H3K27. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2022, 194, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandi, J.; Noberini, R.; Bonaldi, T.; Cecconi, D. Advances in enrichment methods for mass spectrometry-based proteomics analysis of post-translational modifications. J. Chromatogr. A 2022, 1678, 463352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Ge, J.; Li, H. Lysine acetyltransferases and lysine deacetylases as targets for cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2019, 17, 96–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozden, O.; Park, S.-H.; Wagner, B.A.; Song, H.Y.; Zhu, Y.; Vassilopoulos, A.; Jung, B.; Buettner, G.R.; Gius, D. SIRT3 deacetylates and increases pyruvate dehydrogenase activity in cancer cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 76, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakespear, M.R.; Iyer, A.; Cheng, C.Y.; Das Gupta, K.; Singhal, A.; Fairlie, D.P.; Sweet, M.J. Lysine Deacetylases and Regulated Glycolysis in Macrophages. Trends Immunol. 2018, 39, 473–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Xu, P.; He, Y.; Yi, Y.; Liu, Z.; Cai, J.; Huang, L.; Liu, A. Acetylation of Atp5f1c Mediates Cardiomyocyte Senescence via Metabolic Dysfunction in Radiation-Induced Heart Damage. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 4155565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Huang, F.; Wang, Y.; Long, Y.; Li, Y.; Kang, Y.; Gao, W.; Zhang, X.; Wen, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. NAT10-mediated mRNA N(4)-acetylcytidine reprograms serine metabolism to drive leukaemogenesis and stemness in acute myeloid leukaemia. Nat. Cell Biol. 2024, 26, 2168–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Yang, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, K.; Li, P.; Kong, C.; Wu, X.; Sun, H.; Zheng, R.; Sun, W.; et al. NAT10 Is Involved in Cardiac Remodeling Through ac4C-Mediated Transcriptomic Regulation. Circ. Res. 2023, 133, 989–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Du, T.; Zhuang, X.; He, X.; Yan, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhou, H.; Li, Y.; Liao, X.; He, J.; et al. Loss of NAT10 Reduces the Translation of Kmt5a mRNA Through ac4C Modification in Cardiomyocytes and Induces Heart Failure. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2024, 13, e035714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yushanjiang, F.; Fang, Z.; Liu, W. NAT10-mediated RNA ac4C acetylation contributes to the myocardial infarction-induced cardiac fibrosis. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2024, 28, e70141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, S.; Liu, X.; Zhang, C.; Xing, B.; Du, X. Autoacetylation of NAT10 is critical for its function in rRNA transcription activation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 483, 624–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Cai, S.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Z.; Luo, J.; Xing, B.; Du, X. Deacetylation of NAT10 by Sirt1 promotes the transition from rRNA biogenesis to autophagy upon energy stress. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, 9601–9616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macvanin, M.; Gluvic, Z.; Radovanovic, J.; Essack, M.; Gao, X.; Isenovic, E.R. New insights on the cardiovascular effects of IGF-1. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1142644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdellatif, M.; Trummer-Herbst, V.; Heberle, A.M.; Humnig, A.; Pendl, T.; Durand, S.; Cerrato, G.; Hofer, S.J.; Islam, M.; Voglhuber, J.; et al. Fine-Tuning Cardiac Insulin-Like Growth Factor 1 Receptor Signaling to Promote Health and Longevity. Circulation 2022, 145, 1853–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Guerra, J.L.; Castilla-Cortazar, I.; Aguirre, G.A.; Muñoz, Ú.; Martín-Estal, I.; Ávila-Gallego, E.; Granado, M.; Puche, J.E.; García-Villalón, L. Partial IGF-1 deficiency is sufficient to reduce heart contractibility, angiotensin II sensibility, and alter gene expression of structural and functional cardiac proteins. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0181760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.Y.; D’Ercole, A.J. Insulin-like growth factor-I stimulates histone H3 and H4 acetylation in the brain in vivo. Endocrinology 2006, 147, 5480–5490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; Gross, S.; Houser, S.R.; Soboloff, J. Acetylation of SERCA2a, Another Target for Heart Failure Treatment? Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 1285–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kho, C. Targeting calcium regulators as therapy for heart failure: Focus on the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca-ATPase pump. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1185261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, A.K.; Joca, H.C.; Shi, G.; Lederer, W.J.; Ward, C.W. Tubulin acetylation increases cytoskeletal stiffness to regulate mechanotransduction in striated muscle. J. Gen. Physiol. 2021, 153, e202012743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-H.; Major, J.L.; Liebner, T.; Hourani, Z.; Travers, J.G.; Wennersten, S.A.; Haefner, K.R.; Cavasin, M.A.; Wilson, C.E.; Jeong, M.Y.; et al. HDAC6 modulates myofibril stiffness and diastolic function of the heart. J. Clin. Investig. 2022, 132, e148333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahalingam, M.; Girgenrath, T.; Svensson, B.; Thomas, D.D.; Cornea, R.L.; Fessenden, J.D. Structural Mapping of Divergent Regions in the Type 1 Ryanodine Receptor Using Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer. Structure 2014, 22, 1322–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fearnley, C.J.; Roderick, H.L.; Bootman, M.D. Calcium Signaling in Cardiac Myocytes. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011, 3, a004242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, W.; Madan, A.; Foster, D.B.; Cammarato, A. Lysine acetylation of F-actin decreases tropomyosin-based inhibition of actomyosin activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 15527–15539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melkani, G.C.; Bhide, S.; Han, A.; Vyas, J.; Livelo, C.; Bodmer, R.; Bernstein, S.I. TRiC/CCT chaperonins are essential for maintaining myofibril organization, cardiac physiological rhythm, and lifespan. FEBS Lett. 2017, 591, 3447–3458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, M.K.; Shin, Y.; Ju, S.; Han, S.; Choe, W.; Yoon, K.-S.; Kim, S.S.; Kang, I. Heat Shock Response and Heat Shock Proteins: Current Understanding and Future Opportunities in Human Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, C.; Kumar, C.; Gnad, F.; Nielsen, M.L.; Rehman, M.; Walther, T.C.; Olsen, J.V.; Mann, M. Lysine Acetylation Targets Protein Complexes and Co-Regulates Major Cellular Functions. Science 2009, 325, 834–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narita, T.; Weinert, B.T.; Choudhary, C. Functions and mechanisms of non-histone protein acetylation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 20, 156–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peleg, S.; Feller, C.; Ladurner, A.G.; Imhof, A. The Metabolic Impact on Histone Acetylation and Transcription in Ageing. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2016, 41, 700–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francois, A.; Canella, A.; Marcho, L.M.; Stratton, M.S. Protein acetylation in cardiac aging. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2021, 157, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samant, S.A.; Pillai, V.B.; Sundaresan, N.R.; Shroff, S.G.; Gupta, M.P. Histone Deacetylase 3 (HDAC3)-dependent Reversible Lysine Acetylation of Cardiac Myosin Heavy Chain Isoforms Modulates Their Enzymatic and Motor Activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 15559–15569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Backs, J.; Olson, E.N. Control of Cardiac Growth by Histone Acetylation/Deacetylation. Circ. Res. 2006, 98, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trivedi, C.M.; Zhu, W.; Wang, Q.; Jia, C.; Kee, H.J.; Li, L.; Hannenhalli, S.; Epstein, J.A. Hopx and Hdac2 Interact to Modulate Gata4 Acetylation and Embryonic Cardiac Myocyte Proliferation. Dev. Cell 2010, 19, 450–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, E.; Rosenthal, R.E.; Fiskum, G. Pyruvate dehydrogenase complex: Metabolic link to ischemic brain injury and target of oxidative stress. J. Neurosci. Res. 2004, 79, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.; Zhuang, S. Histone acetylation and DNA methylation in ischemia/reperfusion injury. Clin. Sci. 2019, 133, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napoli, C.; Bontempo, P.; Palmieri, V.; Coscioni, E.; Maiello, C.; Donatelli, F.; Benincasa, G. Epigenetic Therapies for Heart Failure: Current Insights and Future Potential. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2021, 17, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarno, F.; Benincasa, G.; List, M.; Barabasi, A.-L.; Baumbach, J.; Ciardiello, F.; Filetti, S.; Glass, K.; Loscalzo, J.; Marchese, C.; et al. Clinical epigenetics settings for cancer and cardiovascular diseases: Real-life applications of network medicine at the bedside. Clin. Epigenetics 2021, 13, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).