Screening and Interventions for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in the Limpopo Province, South Africa: Use of the Community Action Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting and Design

2.2. Population and Sampling

2.3. Ethical Considerations

2.4. Community Action Model (CAM)

- Step 1:

- Train. The study partnered with five community-based clinics to recruit and build the capacity of CHWs to screen for CVD risk factors and counseling on adherence to lifestyle interventions and treatment among rural communities. The CHWs received training on how to conduct health education, risk assessments, and motivational interviewing, and promote cardiovascular health and education. Training with CHWs assessed baseline knowledge and skills and informed the development of the training curriculum and technical assistance provided to the cohort, implementing an enhanced CVD prevention program.

- Step 2:

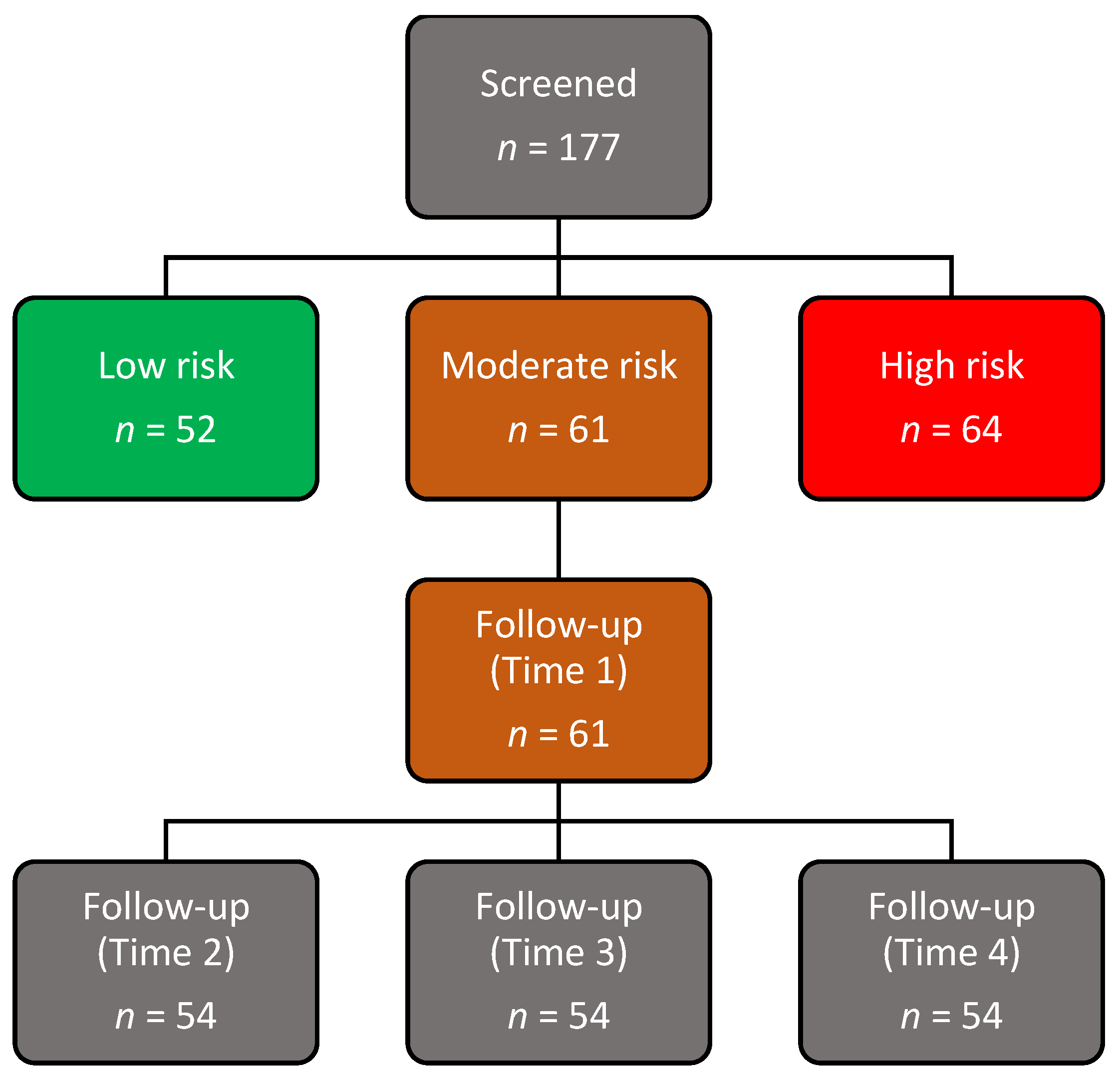

- Diagnosis. CHWs carried out community screening and profiling for the risk of developing a CVD during the second stage. In the diagnosis stage, community members aged 18 were screened utilizing quantitative research techniques and the non-laboratory INTERHEART Risk Score instrument.

- Step 3:

- Analysis. The third step entailed analyzing the results of the profiled communities to identify community members at a moderate and high risk of developing a CVD.

- Step 4:

- Implementation. This phase entailed the implementation of comprehensive CVD preventive measures, such as self-management strategies through educational programs that encouraged patients to engage in more physical activity and eat healthily for those who were at a moderate risk. Those who were found to be at a high risk were referred to the local clinics with a letter of recommendation from the CHW.

- Step 5:

- Enforce. The action’s enforcement is the last stage to guarantee that the intended CVD screening and prevention continue in rural communities. CHWs serve as the foot soldiers throughout each stage, while government entity officials serve as the coaches. A CVD prevention manual guide was eventually created by the researchers with help from the Limpopo Department of Health for use by the clinics in the province of Limpopo. In addition, we helped capacitate participating clinics by making blood pressure machines, weighing scales, and measuring tapes available. In order to help with patient screening even after the initiative was over, participating CHWs were provided with a blood pressure monitor, an umbrella, and a squeeze bottle for carrying water. These steps were taken to support the expansion of community CVD screening, ongoing clinic referrals, health promotion, public awareness, and the long-term viability of this initiative for the prevention and management of CVDs (see Figure 2).

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. The INTERHEART Risk Score Tool

2.7. Measurements

2.8. Intervention Basket

2.9. Validity and Reliability

2.10. Statistical Analysis

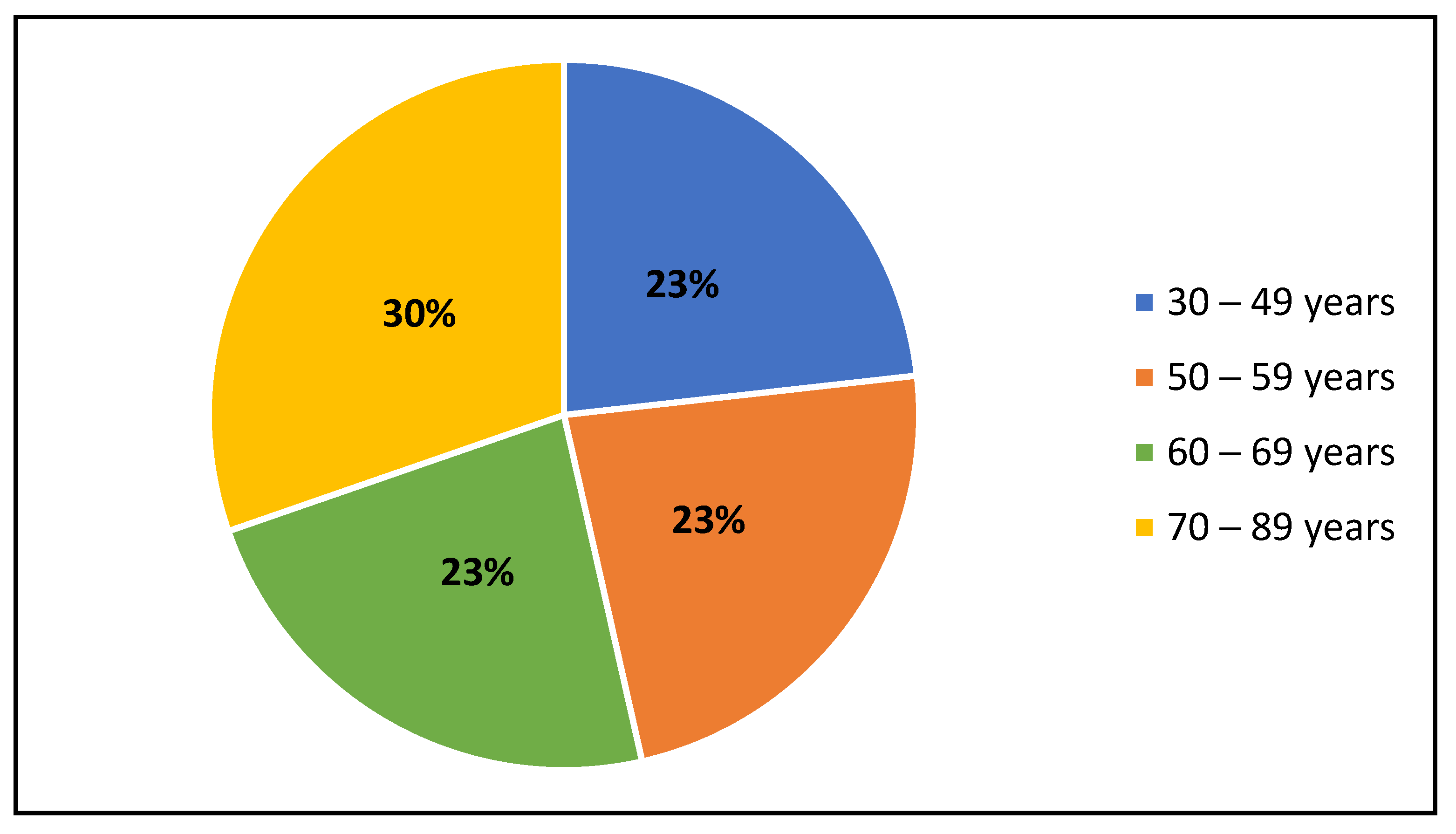

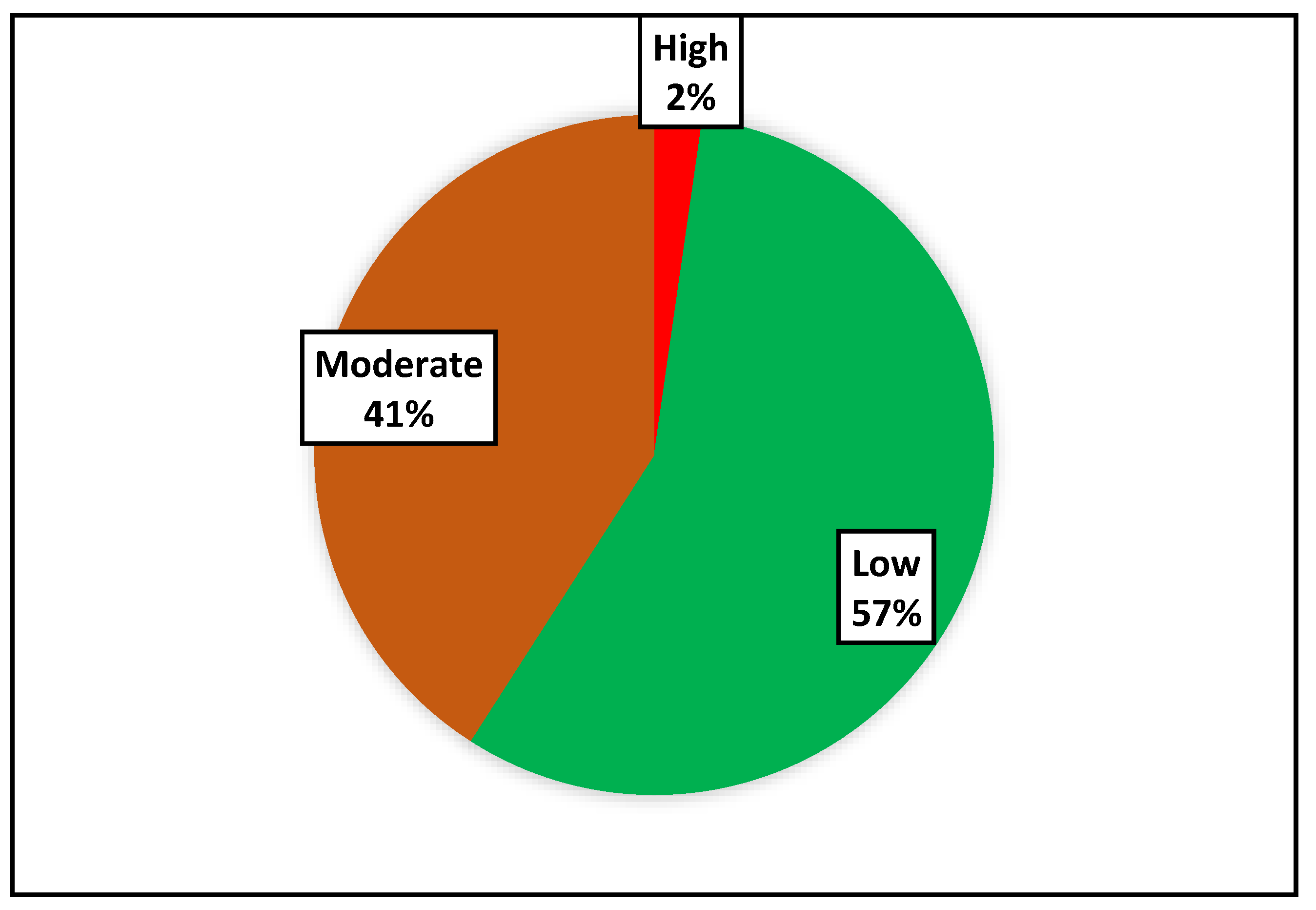

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Non Communicable Diseases. Who.int. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 28 July 2022).

- Mudie, K.; Jin, M.M.; Kendall, L.; Addo, J.; dos-Santos-Silva, I.; Quint, J.; Smeeth, L.; Cook, S.; Nitsch, D.; Natamba, B.; et al. Non-communicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa: A scoping review of large cohort studies. J. Glob. Health 2019, 9, 020409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peer, N.; Steyn, K.; Lombard, C.; Gwebushe, N.; Levitt, N. A high burden of hypertension in the urban black population of Cape Town: The Cardiovascular Risk in Black South Africans (CRIBSA) Study. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e78567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, M.D.; Dalal, S.; Volmink, J.; Adebamowo, C.A.; Njelekela, M.; Fawzi, W.W.; Willett, W.C.; Adami, H.O. Non-communicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa: The case for cohort studies. PLoS Med. 2010, 7, e1000244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Olmen, J.; Schellevis, F.; Van Damme, W.; Kegels, G.; Rasschaert, F. Management of chronic diseases in sub-Saharan Africa: Cross-fertilisation between HIV/AIDS and diabetes care. J. Trop. Med. 2012, 2012, 349312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nojilana, B.; Bradshaw, D.; Pillay-van Wyk, V.; Msemburi, W.; Somdyala, N.; Joubert, J.D.; Groenewald, P.; Laubscher, R.; Dorrington, R.E. Persistent burden from non-communicable diseases in South Africa needs strong action. S. Afr. Med. J. 2016, 106, 436–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutte, A.E. Urgency for South Africa to prioritise cardiovascular disease management. Lancet Glob. Health 2019, 7, e177–e178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J.; Manmathan, G.; Wilkinson, P. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: A review of contemporary guidance and literature. JRSM Cardiovasc. Dis. 2017, 6, 2048004016687211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niiranen, T.J.; Vasan, R.S. Epidemiology of cardiovascular disease: Recent novel outlooks on risk factors and clinical approaches. Expert Rev. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2016, 14, 855–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofori, S.N.; Odia, O.J. Risk assessment in the prevention of cardiovascular disease in low-resource settings. Indian Heart J. 2016, 68, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Package of Essential Noncommunicable (PEN) Disease Interventions for Primary Health Care. Who.int. 2020. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/334186/9789240009226-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 28 July 2022).

- Blundell, H.J.; Hine, P. Non-communicable diseases: Ditch the label and recapture public awareness. Int. Health 2019, 11, 5–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuster, V.; Kelly, B.B.; Vedanthan, R. Promoting global cardiovascular health: Moving forward. Circulation 2011, 123, 1671–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abubakar, I.I.; Tillmann, T.; Banerjee, A. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015, 385, 117–171. [Google Scholar]

- Jha, V.; Garcia-Garcia, G.; Iseki, K.; Li, Z.; Naicker, S.; Plattner, B.; Saran, R.; Wang, A.Y.M.; Yang, C.W. Chronic kidney disease: Global dimension and perspectives. Lancet 2013, 382, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Msemburi, W.; Pillay-van Wyk, V.; Dorrington, R.E.; Neethling, I.; Nannan, N.; Groenewald, P.; Bradshaw, D. Second national burden of disease study for South Africa: Cause-of-death profile for South Africa, 1997–2010. Cape Town S. Afr. Med. Res. Counc. 2014, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Zűhlke, L. Why Heart Disease Is on the Rise in South Africa. 2016. Available online: http://theconversation.com/why-heart-disease-is-on-the–rise-in-south-afric-66167 (accessed on 28 July 2022).

- Gaziano, T.A. Reducing the growing burden of cardiovascular disease in the developing world. Health Aff. 2007, 26, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druetz, T. Integrated primary health care in low-and middle-income countries: A double challenge. BMC Med. Ethics 2018, 19, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherr, K.; Cuembelo, F.; Michel, C.; Gimbel, S.; Micek, M.; Kariaganis, M.; Pio, A.; Manuel, J.L.; Pfeiffer, J.; Gloyd, S. Strengthening integrated primary health care in Sofala, Mozambique. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2013, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aida, B.; Damiati, S.; Sabir, D.K.; Onder, K.; Schuller-Goetzburg, P.; Plakys, G.; Katileviciute, A.; Khoja, S.; Kodzius, R. Management and prevention strategies for non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and their risk factors. Front. Public Health 2020, 788, 574111. [Google Scholar]

- Wandai, M.; Aagaard-Hansen, J.; Day, C.; Sartorius, B.; Hofman, K.J. Available data sources for monitoring non-communicable diseases and their risk factors in South Africa. S. Afr. Med. J. 2017, 107, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofman, K.J.; Lee, R. Intersectoral case study: Successful sodium regulation in South Africa. 2013. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/205179/9789290232339.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2022).

- Cappuccio, F.P.; Miller, M.A. Cardiovascular disease and hypertension in sub-Saharan Africa: Burden, risk and interventions. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2016, 11, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, M.; Kgatla, N.; Sodi, T.; Musinguzi, G.; Mothiba, T.; Skaal, L.; Makgahlela, M.; Bastiaens, H. Facilitators and barriers in prevention of cardiovascular disease in Limpopo, South Africa: A qualitative study conducted with primary health care managers. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2021, 21, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malema, R.N.; Mphekgwana, P.M.; Makgahlela, M.; Mothiba, T.M.; Monyeki, K.D.; Kgatla, N.; Makgatho, I.; Sodi, T. Community-Based Screening for Cardiovascular Disease in the Capricorn District of Limpopo Province, South Africa. Open Public Health J. 2021, 14, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mphekgwana, P.M.; Malema, N.; Monyeki, K.D.; Mothiba, T.M.; Makgahlela, M.; Kgatla, N.; Makgato, I.; Sodi, T. Hypertension Prevalence and Determinants among Black South African Adults in Semi-Urban and Rural Areas. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGorrian, C.; Yusuf, S.; Islam, S.; Jung, H.; Rangarajan, S.; Avezum, A.; Prabhakaran, D.; Almahmeed, W.; Rumboldt, Z.; Budaj, A. Estimating modifiable coronary heart disease risk in multiple regions of the world: The INTERHEART Modifiable Risk Score. Eur. Heart J. 2011, 32, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, N.P.T.; Tarrant, M.; Ngan, E.; So, H.K.; Lok, K.Y.W.; Nelson, E.A.S. Agreement between self-/home-measured and assessor-measured waist circumference at three sites in adolescents/children. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0193355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, E.; Atkins, N.; Stergiou, G.; Karpettas, N.; Parati, G.; Asmar, R.; Imai, Y.; Wang, J.; Mengden, T.; Shennan, A. European Society of Hypertension International Protocol revision 2010 for the validation of blood pressure measuring devices in adults. Blood Press. Monit. 2010, 15, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, J.O.H.N.; MacMahon, S.; Mancia, G.; Whitworth, J.; Beilin, L.; Hansson, L.; Neal, B.; Rodgers, A.; Mhurchu, N.; Clark, T. World Health Organization-International Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the management of hypertension. Guidelines sub-committee of the World Health Organization. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. 1999, 21, 1009–1060. [Google Scholar]

- Lindbohm, J.V.; Sipilä, P.N.; Mars, N.; Knüppel, A.; Pentti, J.; Nyberg, S.T.; Frank, P.; Ahmadi-Abhari, S.; Brunner, E.J.; Shipley, M.J. Association between change in cardiovascular risk scores and future cardiovascular disease: Analyses of data from the Whitehall II longitudinal, prospective cohort study. Lancet Digit. Health 2021, 3, e434–e444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | July-2021 (N = 61) % (95% CI) | Aug-2021 (N = 52) % (95% CI) | Nov-2021 (N = 51) % (95% CI) | Feb-2022 (N = 46) % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean-Age | 60.35 (56.5; 64.2) | |||

| Smoking status | ||||

| Yes | 10 (5; 21) | 8 (3; 19) | 2 (0.22; 12) | 0 |

| No | 90 (79; 96) | 92 (81; 97) | 98 (88; 99) | 100 |

| Waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) | ||||

| <0.873 | 30 (20; 43) | 36 (24; 50) | 49 (36; 62) | 37 (24; 53) |

| Between 0.873–0.963 | 50 (37; 63) | 49 (36; 63) | 42 (30; 56) | 54 (38; 68) |

| ≥0.964 | 20 (12; 32) | 15 (7; 28) | 9 (3; 19) | 9 (3; 23) |

| Depressed/Stressed | 47 (34; 60) | 42 (28; 58) | ||

| High salty food consumption (≥1 time/day) | 65 (52; 76) | 43 (29; 58) | 25 (15; 39) | 16 (7; 31) |

| High-fried food/trans saturated fat consumption (≥3 times/week) | 18 (10; 31) | 20 (11; 35) | 13 (6; 26) | 9 (3; 23) |

| Low fruit consumption (<1 time/day) | 48 (36; 61) | 67 (53; 79) | 44 (31; 58) | 35 (21; 51) |

| Low Vegetable consumption (<1 time/day) | 23 (14; 36) | 31 (19; 45) | 29 (18; 43) | 14 (6; 28) |

| Red meat/poultry consumption ≥ 2 times/day | 45 (33; 58) | 18 (10; 32) | 17 (9; 31) | 2 (0.3; 16) |

| Mild exercise | 55 (42; 67) | 53 (39; 67) | 53 (39; 67) | 22 (13; 39) |

| Pre-Intervention | Post-Intervention | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Mean (95% CI) | Min; Max | Mean (95% CI) | Min; Max | |

| Body weight (kg) | 74.75 (70.03; 79.46) | 34; 118 | 76.74 (71.40; 82.09) | 38; 117 | 0.285 |

| Body height (m) | 1.59 (1.57; 1.61) | 1.39; 1.79 | 1.56 (1.51; 1.61) | 0.58; 1.77 | 0.075 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.47 (27.64; 31.30) | 14.33; 48.13 | 30.43 (28.45; 32.42) | 16.23; 43.50 | 0.075 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 98.68 (95.02; 102.35) | 75; 150 | 100.29 (96.54; 104.04) | 70; 126 | 0.284 |

| Waist-to-hip ratio (cm) | 0.92 (0.87; 0.95) | 0.71; 1.41 | 0.90 (0.87; 0.92) | 0.76; 1.11 | 0.615 |

| Systole | 133.61 (127.65; 139.57) | 85; 202 | 130.70 (124.70; 136.69) | 86; 172.67 | 0.264 |

| Diastole | 79.69 (76.31; 83.08) | 54.67; 116 | 81.46 (78.22; 84.69) | 58.33; 102.33 | 0.268 |

| Prevalence | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | |||

| Obesity; BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 | 50 (37; 63) | 59 (44; 73) | <0.001 * | ||

| Obesity; WC ≥ 90 cm | 78 (66; 87) | 84 (70; 92) | <0.001 * | ||

| Obesity; WHR > 0.90 | 50 (37; 63) | 52 (37; 67) | 0.300 | ||

| Raised SBP (mmHg) | 37 (25; 50) | 30 (18; 45) | 0.006 * | ||

| Raised DBP (mmHg) | 20 (12; 32) | 25 (14; 40) | 0.064 |

| Post-Intervention | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Pre-Intervention | Age-Adjusted | Age, Smoke, Hypertension, Diabetes-Adjusted |

| Mean (95% CI) | Mean (95% CI) | Mean (95% CI) | |

| Body weight (kg) | 74.75 (70.03; 79.46) | 76.74 (72.88; 80.61) | 74.36 (68.40; 80.33) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 29.47 (27.64; 31.30) | 30.44 (29.08; 31.79) | 29.27 (27.27; 31.28) |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 98.68 (95.02; 102.35) | 100.29 (97.67; 102.88) | 99.76 (95.71;103.79) |

| Waist-to-hip ratio (cm) | 0.92 (0.87; 0.95) | 0.90 (0.88; 0.93) | 0.93 (0.89; 0.96) |

| Systole (mmHg) | 133.61 (127.65; 139.57) | 130.70 (125.38; 136.02) | 130. 89 (122.53; 139.26) |

| Diastole (mmHg) | 79.69 (76.31; 83.08) | 81.47 (78.59; 84.32) | 82.94 (78.56; 87.32) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mphekgwana, P.M.; Monyeki, K.D.; Mothiba, T.M.; Makgahlela, M.; Kgatla, N.; Malema, R.N.; Sodi, T. Screening and Interventions for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in the Limpopo Province, South Africa: Use of the Community Action Model. Metabolites 2022, 12, 1067. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo12111067

Mphekgwana PM, Monyeki KD, Mothiba TM, Makgahlela M, Kgatla N, Malema RN, Sodi T. Screening and Interventions for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in the Limpopo Province, South Africa: Use of the Community Action Model. Metabolites. 2022; 12(11):1067. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo12111067

Chicago/Turabian StyleMphekgwana, Peter M., Kotsedi D. Monyeki, Tebogo M. Mothiba, Mpsanyana Makgahlela, Nancy Kgatla, Rambelani N. Malema, and Tholene Sodi. 2022. "Screening and Interventions for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in the Limpopo Province, South Africa: Use of the Community Action Model" Metabolites 12, no. 11: 1067. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo12111067

APA StyleMphekgwana, P. M., Monyeki, K. D., Mothiba, T. M., Makgahlela, M., Kgatla, N., Malema, R. N., & Sodi, T. (2022). Screening and Interventions for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in the Limpopo Province, South Africa: Use of the Community Action Model. Metabolites, 12(11), 1067. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo12111067