Digital Influencers, Food and Tourism—A New Model of Open Innovation for Businesses in the Ho.Re.Ca. Sector

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Influencers vs. Celebrities in the Social Media Era

2.2. Credibility, Value Perception, and Purchase Intentions

2.3. Social Media and Destination Image

2.4. Experience of “Local”/“Typical” and Social Media

2.5. Instagram and Influencers

2.6. The Chiara Ferragni Case

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Netnographic Analysis

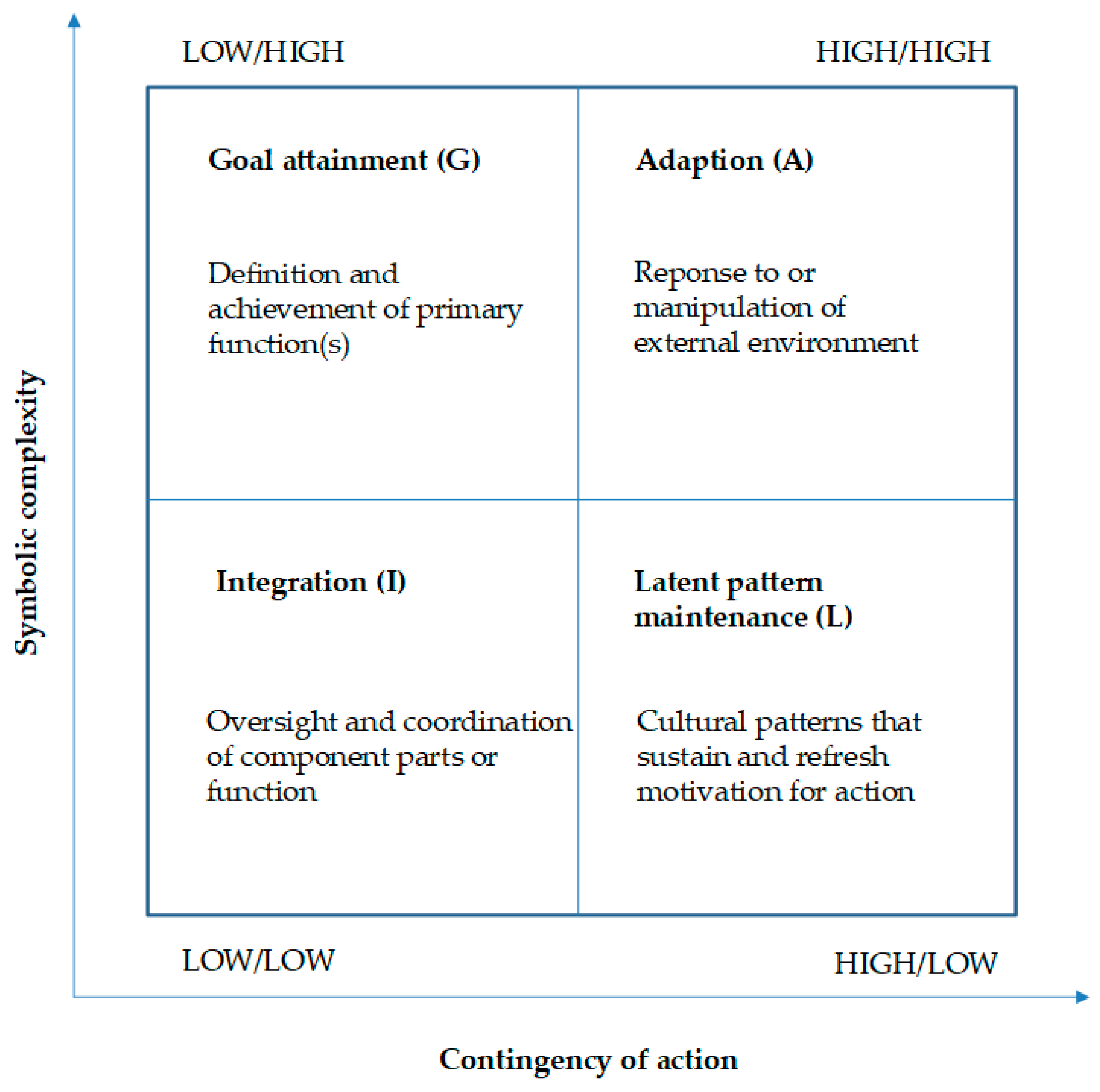

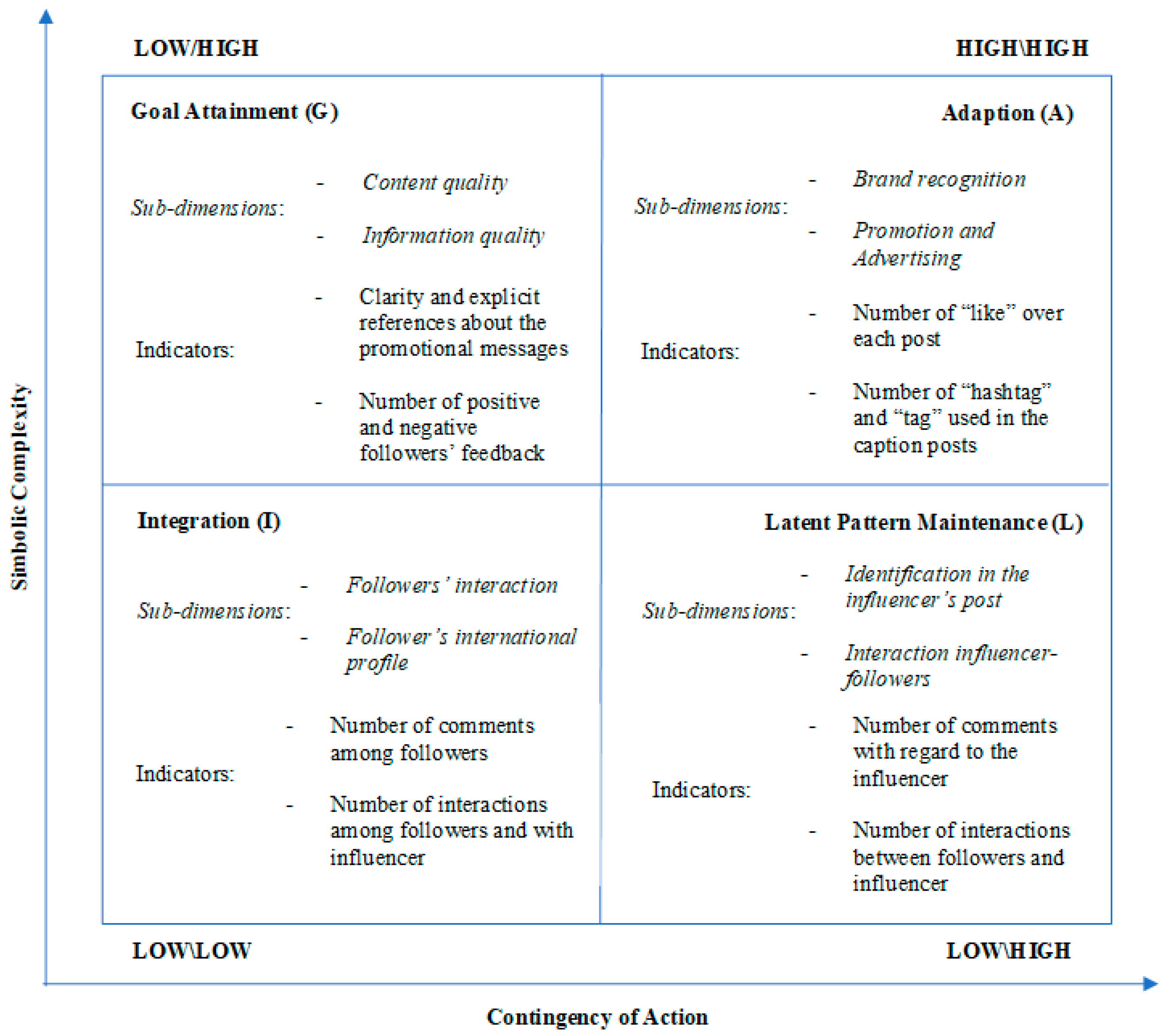

3.2. AGIL Method

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Data Analysis

3.4.1. Netnographic Analysis

- Data from these posts were stored using the Airtable software to create a hybrid spreadsheet–database. In the database, each row was one post extracted from C.F.’s account, and the columns were all data considered (relevant information) for the in-depth examination. Specifically, for each single post the following data were extracted:

- Publishing date;

- Place showed (by geolocation);

- Number of “like”;

- Comments;

- Photo caption;

- “hashtag” or “tag” (to other people or referred to the visited place);

- Number of pictures in the post (from a minimum of 1 to a maximum of 10 photos in total);

- Link associated to the original post.

3.4.2. AGIL Analysis

- Number of posts/stories (also with other involved people such mother, sisters, husband, children, and friends), caption, and use of special tags to identify tour operators or brands of facilities visited (how many times does it show to do unconcealed advertising);

- Number of posts for all categories and number of hashtags with #supplied and @ifexeperience tags, @destination tags, @food tags, @restaurant tags, etc. (for calculation out of total posts published over the weekend to measure the relative frequency);

- Number of feedback (positive/negative) for each post;

- Number of comments (positive/negative) between influencer and followers, from followers to influencer, among followers, and number of comments in the English language;

- Number of posts containing precise information on the characteristics of the product/service presented (information) and relative feedback (n. of emoji and comments such as positive/negative “feedback” that shows that the user has understood the message (about the product/service proposed), number of informational posts provided to followers for each type of topic observed;

- Number of comments of appreciation such as “me too” and appreciations about the place/product of a sharing type of latent content to the post published by the influencer (e.g., “I’ve been there”, “I got married there”, “I’d like to go there”, “I’ve been there too”, etc.).

- 1.

- For each topic, the total score assigned to all dimensions of the AGIL scheme was divided by the maximum score assignable all dimensions (tot. max.) (10 pts for each dimension multiplied by 4 dimensions, which is equal to 40 pts) indicated as TEmax.

- 2.

- For all the topics considered together, DEmax was calculated as the SUM scores assigned to each dimension divided by the maximum score (max,) assignable to each dimension, (max. 5 pts for 2 indicators multiplied by the n° of key-findings observed).

- 3.

- For all the topics considered together, DEΣ was calculated as the SUM scores assigned to each dimension divided by the sum of scores assigned to all dimensions

- 4.

- For each topic, DEmax was calculated as the total score assigned to each dimension of the AGIL scheme divided by the maximum score assignable to each dimension (5 pt × 2 = 10 pt)

- 5.

- For each topic, DEΣ was calculated as the total score assigned to each dimension of the AGIL scheme divided by the SUM of scores assigned to all dimensions (of the same topic)

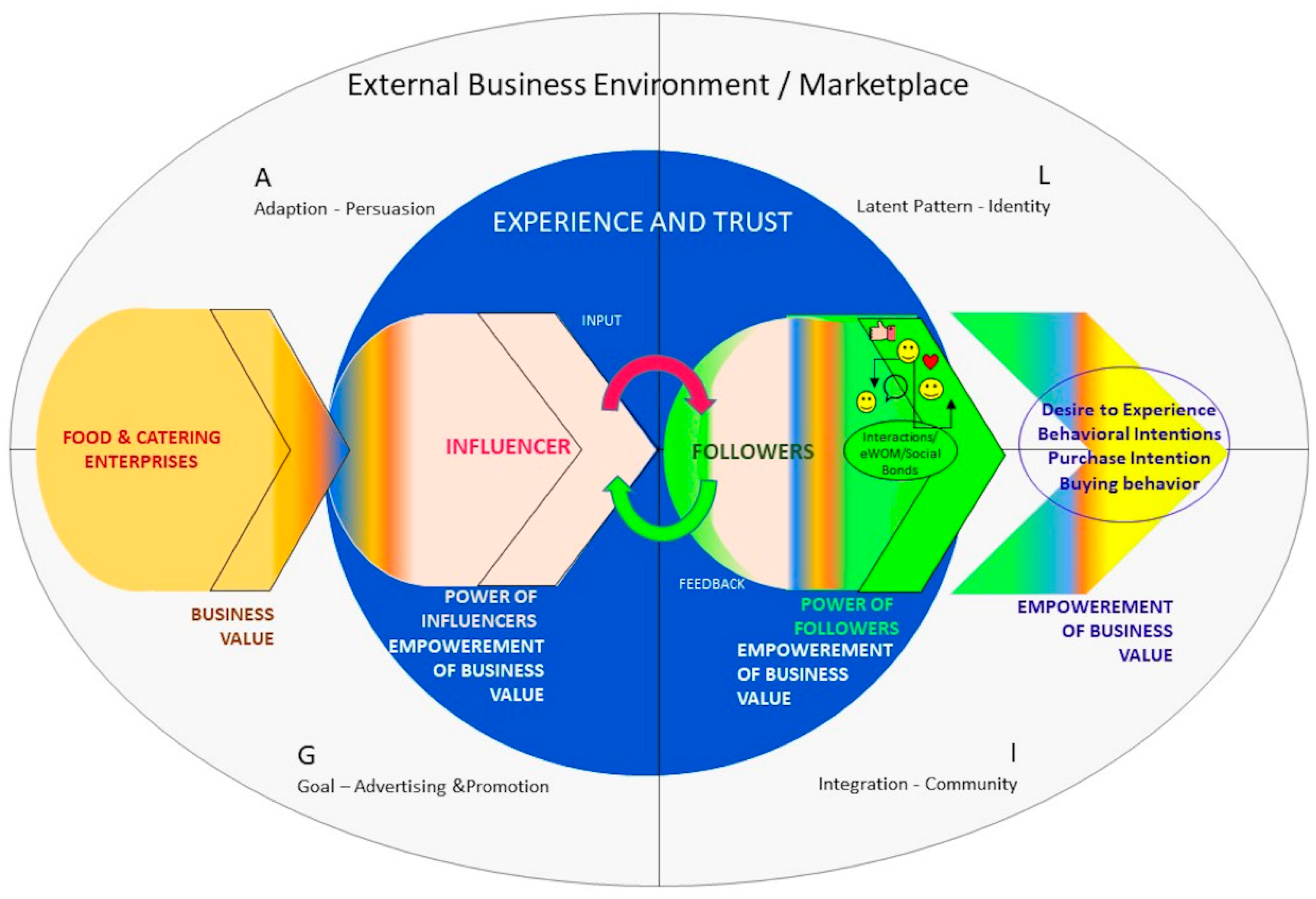

4. Results

4.1. Results of the Netnographic Analysis

- C.F. on the road to visit a touristic destination (one-day trip or weekend trip, rarely for more than 3 days);

- Presentation of landscapes during travel and of final destination;

- Presentation of the accommodation where C.F. is staying as a comfortable, stunning, and unique place to stay;

- Presentation of C.F.’s room, usually with something impressive (e.g., panoramic view from the window, luxurious bathroom, etc.);

- Presentation of food C.F. is eating at the hotel during breakfast or lunch;

- Storytelling of tourist visits at locations of interest in the selected destination, sometimes with a tourist guide (e.g., City, Museums, sites of historical, architectural, cultural or natural interest;

- C.F. at a traditional restaurant of the visited location eating local food prepared following typical local recipes;

- C.F. back in Milan, seated at a typical or traditional restaurant, often expensive (e.g., Marchesi 1824, in Milan) eating Italian food (very often pizza or pasta).

4.2. Results of AGIL Scheme

4.3. AGIL Dimensions in Each Key Factor

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cassia, F.; Magno, F. Assessing the Power of Social Media Influencers: A Comparison Between Tourism and Cultural Bloggers. In Predicting Trends and Building Strategies for Consumer Engagement in Retail Environments; IGI Global; Available online: https://www.igi-global.com/chapter/assessing-the-power-of-social-media-influencers/228220 (accessed on 3 November 2021).

- LINQIA. 2017. Available online: https://www.linqia.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/The-State-of-InfluencerMarketing2017_Final-Report.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2021).

- Lou, C.; Yuan, S. Influencer marketing: How message value and credibility affect consumer trust of branded content on social media. J. Inter. Adv. 2019, 19, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M. Influence for social good: Exploring the roles of influencer identity and comment section in Instagram-based LGBTQ-centric corporate social responsibility advertising. Int. J. Advert. 2021, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schouten, A.; Janssen, L.; Verspaget, M. Celebrity vs. Influencer endorsements in advertising: The role of identification, credibility, and Product-Endorser fit. Inter. J. Adve. 2020, 39, 258–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholamhosseinzadeh, M.; Chapuis, J.; Lehu, J. Tourism netnoghraphy: How travel bloggers influence destination image. Tour. Recreat Res. 2021, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djafarova, E.; Rushworth, C. Exploring the credibility of online celebrities’ Instagram profiles in influencing the purchase decisions of young female users. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 68, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingrassia, M.; Altamore, L.; Bacarella, S.; Columba, P.; Chironi, S. The wine influencers: Exploring a new communication model of open innovation for wine producers—A Netnographic, factor and AGIL analysis. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A.M.; Haenlein, M. Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Bus. Horiz. 2010, 53, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleck, N.; Korchia, M.; Roy, L.I. Celebrities in advertising: Looking for congruence or likability? Psychol. Mark. 2012, 29, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McCracken, G. Who is the Celebrity Endorser? Cultural Foundations of the Endorsement Process. J. Consum. Res. 1989, 16, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckler, S.; Childers, T. The Role of Expectancy and Relevancy in Memory for Verbal and Visual Information: What is Incongruency? J. Cons. Res. 1992, 18, 475–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chironi, S.; Ingrassia, M. Study of the importance of emotional factors connected to the colors of fresh-cut cactus pear fruits in consumer purchase choices for a marketing positioning strategy. Acta Hortic. 2015, 1067, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erz, A. Christensen ABH. Transforming consumers into brands: Tracing transformation processes of the practice of blogging. J. Interact. Market. 2018, 43, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magno, F.; Cassia, F. The impact of social media influencers in tourism. Anatolia 2018, 29, 288–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, C.; Quan, X. Something social, something entertaining? How digital content marketing augments consumer experience and brand loyalty. Int. J. Advert. 2021, 40, 376–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.N.; Newman, B.I.; Gross, B.L. Why we buy what we buy: A theory of consumption values. J. Bus. Res. 1991, 22, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Stepchenkova, S. Effect of tourist photographs on attitudes towards destination: Manifest and latent content. Tour. Manag. 2015, 49, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altamore, L.; Ingrassia, M.; Chironi, S.; Columba, P.; Sortino, G.; Vukadin, A.; Bacarella, S. Pasta experience: Eating with the five senses-A pilot study. AIMS Agric. Food 2018, 3, 493–520. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Luo, X.; Cao, Y. Investigating the influence of online interpersonal interaction on purchase intention based on stimulus-organism-reaction model. Hum. Cent. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2018, 8, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaulagain, S.; Wiitala, J.; Fu, X. The impact of country image and destination image on US tourists’ travel intention. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2019, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Wang, R.; Wei, Z.; Zhai, Q. Temporal-spatial measurement and prediction between air environment and inbound tourism: Case of China. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 287, 125486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chironi, S.; Altamore, L.; Columba, P.; Bacarella, S.; Ingrassia, M. Study of wine producers’ marketing communication in extreme territories—Application of the AGIL scheme to wineries’ website features. Agronomy 2020, 10, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arefieva, V.; Egger, R.; Yu, J. A machine learning approach to cluster destination image on Instagram. Tour. Manag. 2021, 85, 104318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirillova, K.; Fu, X.; Lehto, X.; Cai, L. What makes a destination beautiful? Dimensions of tourist aesthetic judgment. Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.E.; Xie, S.Y.; Wen, J. Coloring the destination: The role of color psychology on Instagram. Tour. Manag. 2020, 80, 104110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Kerstetter, D.L. From sad to happy to happier: Emotion regulation strategies used during a vacation. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 69, 104110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riemer, H.; Noel, H. The effect of emotionally-arousing ad appeals on memory: Time and fit matter. Int. J. Advert. 2021, 40, 1024–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sortino, G.; Allegra, A.; Inglese, P.; Chironi, S.; Ingrassia, M. Influence of an evoked pleasant consumption context on consumers’ hedonic evaluation for minimally processed cactus pear (Opuntia ficus-indica) fruit. Acta Hortic. 2016, 1141, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrecque, L.I.; Patrick, V.M.; Milne, G.R. The marketers’ prismatic palette: A review of color research and future directions. Psychol. Mark. 2013, 30, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, A.R.; Martinez, L.M.; Martinez, L.F.; Rando, B. Color in web banner advertising: The influence of analogous and complementary colors on attitude and purchase intention. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2021, 50, 101100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, Y.C.; Chiu, H.C.; Tang, Y.C.; Lee, M. Do colors change realities in online shopping? J. Interact. Mark. 2018, 41, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellia, C.; Scavone, V.; Ingrassia, M. Food and Religion in Sicily—A New Green Tourist Destination by an Ancient Route from the Past. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.V.M.; Chen, H.; Lee, Y.M. Factors influencing customers’ dine out intention during COVID-19 reopening period: The moderating role of country-of-origin effect. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 95, 102894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingrassia, M.; Bacarella, S.; Columba, P.; Altamore, L.; Chironi, S. Traceability and labelling of food products from the consumer perspective. Chem. Eng Trans. 2017, 58, 865–870. [Google Scholar]

- Bellia, C.; Safonte, F. Agri-food products and branding which distinguishes quality. Economic dimension of branded products such as pdo/pgi under EU legislation and value-enhancement strategies Prodotti agroalimentari e segni distintivi di qualità. Econ. Agro-Aliment./Food Econ. 2015, 17, 81–105. [Google Scholar]

- Ricci, E.C.; Stranieri, S.; Casetta, C.; Soregaroli, C. Consumer preferences for Made in Italy food products: The role of ethnocentrism and product knowledge. AIMS Agric Food 2019, 4, 88–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, C.; Pilato, M.; Bellia, C. Geographical indications in the UK after Brexit: An uncertain future? Food Policy 2020, 90, 101808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chironi, S.; Bacarella, S.; Altamore, L.; Columba, P.; Ingrassia, M. Consumption of spices and ethnic contamination in the daily diet of Italians-consumers’ preferences and modification of eating habits. J. Ethn. Foods 2021, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gon, M. Local experiences on Instagram: Social media data as source of evidence for experience design. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 19, 100435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langaro, D.; Hackenberger, C.; Loureiro, S. Storymaking: An investigation on the process of co-created brand storytelling in the sporting goods industry. Glob. Fash. Manag. Conf. 2019, 2019, 812–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- STATISTA. Available online: https://www.statista.com/ (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- HUBSPOT. Available online: https://www.hubspot.com/marketing-statistics (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Mohsin, M. 10 Instagram Stats Every Marketer Should Know in 2021. Available online: https://www.oberlo.com/blog/instagram-stats-every-marketer-should-know (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Schomer, A. Influencer Marketing Report 2020: Industry Stats & Market Research—Business Insider. 2019. Available online: https://www.businessinsider.com/influencer-marketing-report (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- WIKIPEDIA. Available online: https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chiara_Ferragni (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Chiara Ferragni—Unposted, Directed by Elisa Amoruso—Documentary. 2019. Available online: https://www.primevideo.com/detail/amzn1.dv.gti.c2b7574c-e740-d2e5-e525-5d61f4c423af (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Keinan, A.; Maslauskaite, K.; Crener, S.; Dessain, V. The Blonde Salad. Harvard Business School Case 515-074. 2015. Available online: https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=48520&source=post_page (accessed on 5 February 2022).

- Emergenza COVID-19: Chiara Ferragni e Fedez in aiuto del San Raffaele. Available online: www.hsr.it (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- FORBES. Available online: https://forbes.it/2020/09/02/chiara-ferragni-agli-uffizi-direttore-schmidt-spiega-come-la-cultura-puo-diventare-il-petrolio-d-italia/ (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Kozinets, R.V. The field behind the screen: Using netnography for marketing research in online communities. J. Mark. Res. 2002, 39, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morais, G.M.; Santos, V.F.; Gonçalves, C.A. Netnography: Origins, foundations, evolution and axiological and methodological developments and trends. Qual. Rep. 2020, 25, 441–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozinets, R.V.; Scaraboto, D.; Parmentier, M.A. Evolving netnography: How brand auto-netnography, a netnographic sensibility, and more-than-human netnography can transform your research. J. Mark. Manag. 2018, 34, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parsons, T. An outline of the social system. In Theories of Society; Parsons, T., Shils, E.A., Naegele, K.D., Pitts, J.R., Eds.; Simoon & Shuster, The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1961; Available online: http://www.csun.edu/~snk1966/Talcott%20Parsons%20-%20An%20Outline%20of%20the%20Social%20System.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Ingrassia, M.; Altamore, L.; Columba, P.; Bacarella, S.; Chironi, S. The communicative power of an extreme territory–the Italian island of Pantelleria and its passito wine: A multidimensional-framework study. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2018, 30, 292–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briliana, V.; Ruswidiono, W.; Deitiana, T. How social media are successfully transforming the marketing of local street food to better serve the constantly-connected digital consumer. Adv. Econ. Bus. Manag. Res. 2021, 174, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeb, S.; Hussain, S.S.; Javed, A. COVID-19 and a way forward for restaurants and street food vendors. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2021, 8, 1923359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, L.M.; Chong, S.M.; Lim, H. Influencer marketing: Social media influencers as human brands attaching to followers and yielding positive marketing results by fulfilling needs. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 55, 102133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Y.; Chen, K.J.; Lin, J.S. When social media influencers endorse brands: The effects of self-influencer congruence, parasocial identification, and perceived endorser motive. Int. J. Advert. 2020, 39, 590–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samira, F.; Fangm, W.; Yufei, Y. Opinion leadership vs. para-social relationship: Key factors in influencer marketing. J. Ret. Cons. Serv. 2021, 59, 102371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinton, S.; Harridge-March, S. Relationships in online communities: The potential for marketers. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2010, 4, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H. Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology; HBS Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough, H. Business model innovation: It’s not just about technology anymore. Strategy Leadersh. 2007, 35, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chesbrough, H.; Vanhaverbeke, W.; West, J. (Eds.) . Open Innovation: Researching a New Paradigm; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough, H. Open Business Models: How to Thrive in the New Innovation Landscape; HBS Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bayona-Saez, C.; Cruz-Cázares, C.; García-Marco, T.; García, M.S. Open innovation in the food and beverage industry. Manag. Decis. 2017, 55, 526–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sadat, S.H.; Nasrat, S. The practice of open innovation by SMEs in the food industry. J. Innov. Manag. 2020, 8, 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.J.; Park, K.; Gaudio, G.D.; Corte, V.D. Open innovation ecosystems of restaurants: Geographical economics of successful restaurants from three cities. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2020, 28, 2348–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzarotti, V.; Manzini, R. Different modes of open innovation: A theoretical framework and an empirical study. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2009, 13, 615–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H.; Kim, S.; Agogino, A. Chez Panisse: Building an open innovation ecosystem. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2014, 56, 144–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.H.J.; Zhao, X.; Jung, K.H.; Yigitcanlar, T. The culture for open innovation dynamics. Sustainability 2020, 12, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Ruiz, E.; Ruiz-Romero de la Cruz, E.; Zamarreño-Aramendia, G.; Cristòfol, F.J. Strategic Management of the Malaga Brand through Open Innovation: Tourists and Residents’ Perception. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Chen, Y.; Lin, Z. Mapping destination images and behavioral patterns from user-generated photos: A computer vision approach. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 25, 1199–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, J.Y.J.; Kim, S. Effects of tourists’ local food consumption value on attitude, food destination image, and behavioral intention. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 71, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorno-Hinojosa, R.; Koria, M.; Ramírez-Vázquez, D.d.C. Open Innovation with Value Co-Creation from University–Industry Collaboration. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.Y.; Koseoglu, M.A.; Qi, L.; Liu, E.C.; King, B. The sway of influencer marketing: Evidence from a restaurant group. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 98, 103022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| AGIL Dimension | Meaning of AGIL Dimensions | Sub-Dimension | Indicator | DEmax 1 | DEƩ 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimension A ADAPTION | Persuasion (ability of the influencer to persuade followers and change preferences and behaviors) | Brand recognition | Number of “like” over each post | 76.67% | 27.71% |

| Value added to touristic destination and typical local food | Promotion and advertising | Number of “hashtag” and “tag” used in the caption post | |||

| Dimension G GOAL ATTAINMENT | Advertising and Promotion (information about product/service) | Content quality | Clarity and explicit references about promotional messages | 85.00% | 30.72% |

| Feedback about information on touristic destination and typical local food provided | Information quality | Number of positive and negative followers’ feedback | |||

| Dimension I INTEGRATION | Power of Community | Interactions and bonds among followers | Number of followers’ interactions | 55.00% | 19.88% |

| Interaction and bonding among followers | Interactions and bonds among followers worldwide (international profiles) | Number of interactions among followers of different countries (not only Italian followers) | |||

| Dimension L LATENT PATTERN MAINTENANCE | Identification of followers with the Influencer | Identification with the influencer’s post/situation published | Number of comments with regard to the influencer | 60.00% | 21.69% |

| Peer-to-peer recommendations on tourist destination and typical local food | Interaction between the influencer and her followers | Number of influencer interactions with regard to her followers |

| Topic | TEmax 1 | Dimension Effectiveness | Tot. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | G | I | L | |||

| Posts of Touristic Destinations | 78% | 26% 2 | 29% 2 | 16% 2 | 29% 2 | 100% |

| 80% 3 | 90% 3 | 50% 3 | 90% 3 | - | ||

| Posts of Typical Food in Accommodations | 70% | 25% 2 | 29% 2 | 29% 2 | 18% 2 | 100% |

| 70% 3 | 80% 3 | 80% 3 | 50% 3 | - | ||

| Posts of Touristic Accommodations | 68% | 33% 2 | 33% 2 | 15% 2 | 19% 2 | 100% |

| 90% 3 | 90% 3 | 40% 3 | 50% 3 | - | ||

| Posts of Typical Local Food | 65% | 23% 2 | 35% 2 | 19% 2 | 23% 2 | 100% |

| 60% 3 | 90% 3 | 50% 3 | 60% 3 | - | ||

| Posts of Typical Food in a Touristic Destination | 60% | 29% 2 | 25% 2 | 25% 2 | 21% 2 | 100% |

| 70% 3 | 60% 3 | 60% 3 | 50% 3 | - | ||

| Posts of Accessories exhibition with a Touristic Background | 75% | 30% 2 | 33% 2 | 17% 2 | 20% 2 | 100% |

| 90% 3 | 100% 3 | 50% 3 | 60% 3 | - | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ingrassia, M.; Bellia, C.; Giurdanella, C.; Columba, P.; Chironi, S. Digital Influencers, Food and Tourism—A New Model of Open Innovation for Businesses in the Ho.Re.Ca. Sector. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc8010050

Ingrassia M, Bellia C, Giurdanella C, Columba P, Chironi S. Digital Influencers, Food and Tourism—A New Model of Open Innovation for Businesses in the Ho.Re.Ca. Sector. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity. 2022; 8(1):50. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc8010050

Chicago/Turabian StyleIngrassia, Marzia, Claudio Bellia, Chiara Giurdanella, Pietro Columba, and Stefania Chironi. 2022. "Digital Influencers, Food and Tourism—A New Model of Open Innovation for Businesses in the Ho.Re.Ca. Sector" Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 8, no. 1: 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc8010050

APA StyleIngrassia, M., Bellia, C., Giurdanella, C., Columba, P., & Chironi, S. (2022). Digital Influencers, Food and Tourism—A New Model of Open Innovation for Businesses in the Ho.Re.Ca. Sector. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 8(1), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc8010050