1. Introduction

As has been documented in some pieces of research, consumers very often favor the acquisition of nationally produced products above foreign products. In some cases, this is due to the influence that is wielded by the origin of those products on the customer’s intention to buy Baughn et al. [

1]. Ethnocentrism is one of the variables studied to better understand this behavioral pattern. In the sphere of consumption, ethnocentrism allows us to identify the level of influence that the group of origin exerts on the local consumer in relation to their buying habits and also in their perception of the quality of foreign, Shimp et al. and Sharma et al. [

2,

3].

Nonetheless, according to de Ruyter et al., Shankarmahesh, and Thelen et al. [

4,

5,

6], literature is scant when seeking information about the implications of the consumer’s ethnocentrism as applied to the services sector (SET). According to Vivek et al. [

7], ethnocentric tendencies are more at the fore when choosing a service provider (SET) in comparison to tendencies in relation to the selection of tangible products. Contrary to the fact that the marks or signals denoting the country of origin are disappearing from goods, the origin of service providers is indeed one of the factors that influence the intention to purchase.

According to Speece et al. [

8], the nationality of the staff the customer interacts with during the presentation of the service and the origin country of that service also impact the consumer’s perception and intention of buying, this is the reason why it is necessary to research ethnocentrism in the scope of services.

On the other hand, for Clark [

9], international services embrace a diverse range of activities, making it very complex to generalize them. For this reason, through the study of ethnocentrism in services, many psychological factors could be analyzed to know the possible attachment with a particular service, depending on the brand or country of origin of that service, Salciuviene et al. [

10].

These international services are accompanied on many occasions by a global brand that allows the identification of the services provider in the world. This global brand sets standard communication aspects through its logo, image, positioning, and final consumer type, Akaka et al. [

11]. This allows global brands to be accepted and have more desirability from the local consumer, Özsomer et al. [

12] and in this way, they are seen by the consumer as a high-quality brand with higher prestige and more functional and symbolic benefits, the reason why the global character from a brand directly impacts the product or service that comes with it, Dimofte et al., Özsomer, and Xie et al. [

13,

14,

15].

This may become more evident in the hedonic services sector given that these types of services are centered on a consumer experience in which the consumer seeks to obtain a personalized experience that satisfies their need for pleasure, emotion, and entertainment whilst utilitarian services, in contrast, possess a purely functional character, Bigné et al. [

16]. According to Pérez et al. [

17], catering services are hedonic services that are focused on pleasing consumers and affective responses may overwhelm cognitive responses. The relevance of analyzing this concept in terms of developing countries springs from this fact.

It is also important to point out that in the services context exists a higher perception of hedonic services as those services with a foreign name and for that reason, a preference for those brands, Salciuviene et al. [

10].

For this reason, a deeper study of ethnocentrism in hedonic services may provide an academic perspective to be used by multinational service companies wishing to develop their business in various parts of the world. Keeping in mind that companies that commence selling not only products but also services, increase their profitability between 8 to 8.5%, Crozet et al. [

18], the growing internationalization of this sector can only serve to increase interest in this study.

Nonetheless, the study of consumer ethnocentrism has concentrated on developed countries in which the importation of products is seen as something negative (especially when the country of origin is a developing country) and for this reason, ethnocentric consumers prefer to purchase national products. However, the purchase of imported products in developing countries can generate a type of symbolic consumption, playing the role of a status symbol and representing a means to stand out from the crowd, Wang et al. [

19].

Emerging markets are being presented with high growth of the middle-class consumer, who has greater acquisition power. For this reason, international enterprises have increased their presence in these countries through different commercial activities. Considering this, it is important that marketing specialists provide better attention to particular characteristics from these developing countries and their consumers since the literature has centralized in the study of big economies and not in developing countries. On the other hand, taking into account that in a majority of cases, global brands come from developed countries, it is crucial to understand the differences between the consumption patterns in emerging markets, compared with consumers in developed countries. So, diverse strategies could be generated for these global brands to be successful in emerging countries, Wang et al. [

20].

For this reason, the overvaluation from a usually western foreign culture and the corresponding underestimation from the national culture, is a common topic in studies from emerging market’s economics, Montero [

21]. For Van et al. [

22] the not ethnocentric segments with a big size could be attractive market niches for overseas companies, where marketing strategies can be made in the international component of the brand. While for local enterprises, the strategy of emphasizing the internal origin of their products could end up being negative. Meaning that it is necessary for international services enterprises to apply different strategies, depending on the consumer’s ethnocentrism in the country where they operate.

With this in mind, the principal objective of this current study is to produce a proposal for SET analysis that enables comprehension of factors that explain consumer ethnocentrism in regard to international companies offering services of a hedonic character in developing countries with a global brand. To this end, we have focused on Starbucks in Colombia. It is worth noting that Starbucks began operations in Colombia in 2014. This North American coffee shop chain offers a brand-named experience that engages its customers in a multi-sensorial and hedonic manner via experiential marketing, Ding et al. [

23]. For the purposes of this investigation, Colombia is considered a developing country, owing to the fact that in 2018, it was placed last in social inequality; it is a country in which it takes 11 generations for a family to attain the average income, OECD [

24]. On the other hand, the per capita GDP of Colombia, according to the World Bank, is 6667 US dollars and according to the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) of 2017, the Human Development Index (HDI) of Colombia was 0.747.

According to The International Coffee Organization [

25], by May 2019, Colombia occupied the third place as a world coffee exporter, where its total production for the harvesting year 2018/2019 is estimated at 8.2 million sacks, 2.7% more than the previous period 2017/2018. It is also important to note that the USA is the main receptor of this Colombian coffee, with 46.5% of all exportations from this country, this is the reason why coffee is a very important product in the Colombian economy.

Hwang et al. [

26] consider that consumer loyalty allows for a preference towards one particular service provider; this generates commitment to buy from them again, social and emotional bonds, and leads to less sensitivity towards the price of the service, Ogba and Rowley [

27,

28]. Ethnocentric consumers tend to develop a marked loyalty towards national brands, Zeithaml et al. [

29].

For Burgess et al. [

30] the knowledge of marketing phenomena drifts almost exclusively from researches made in industrialized countries with a high income, for this reason, there is a need to generate new marketing inputs that come from emerging economies to contribute to the academic literature. In this way, it could be said that emerging markets are radically different than they are in traditional, capitalist, and industrialized societies. That is why the boom of these markets offers new investigation opportunities in marketing, Sheth [

31].

For Wang et al. [

20] more investigations are needed to know how the image of a global brand develops in an emerging market and also to know if these brands are able to adapt to that market through the addition of local cultural values. In the same way, to know if concepts such as national identity, patriotism, and ethnocentrism affect, in a very important manner, the development of these brands in those markets.

For this reason, it is needed to enlarge the research of global brands in these developing countries, even though the global brands show a solid image that provides them a competitive advantage compared to local brands, these brands should also face the resistance of consumers with a high level of ethnocentrism and patriotism, Wang and Chen; Wang and He, and He et al. [

19,

20,

32], besides global brands in the context of developing countries, should also face different challenges in terms of service delivery, of communication, specific cultural meanings, and local tension regarding the rivalry between global and local brands; and where some keys for the development of the global brand in a developing country should have the skills to work out a direct dialogue with the local culture, meaning its ability for local adaptation, without losing its globality.

On the other hand, also it is expected from these brands to be humble, instead of being haughty despite their global importance, Suarez et al. [

33]. This way, it is needed to go deeper into the concept of global brands in developing countries, with the ethnocentrism of the consumer in hedonic services, the reason why this study presents an academic input to the short amount of existing literature that embraces these topics as a whole.

With these facts in mind, this work provides a deeper understanding of how the level of ethnocentrism in the selection of services influences loyalty in the realm of hedonic services and considers antecedents such as patriotism, collectivism, and individualism in consumers in a developing country (which is also an exporter and regular consumer of one of the best coffees in the world); this approach involves looking at a foreign company from a developed country offering a service.

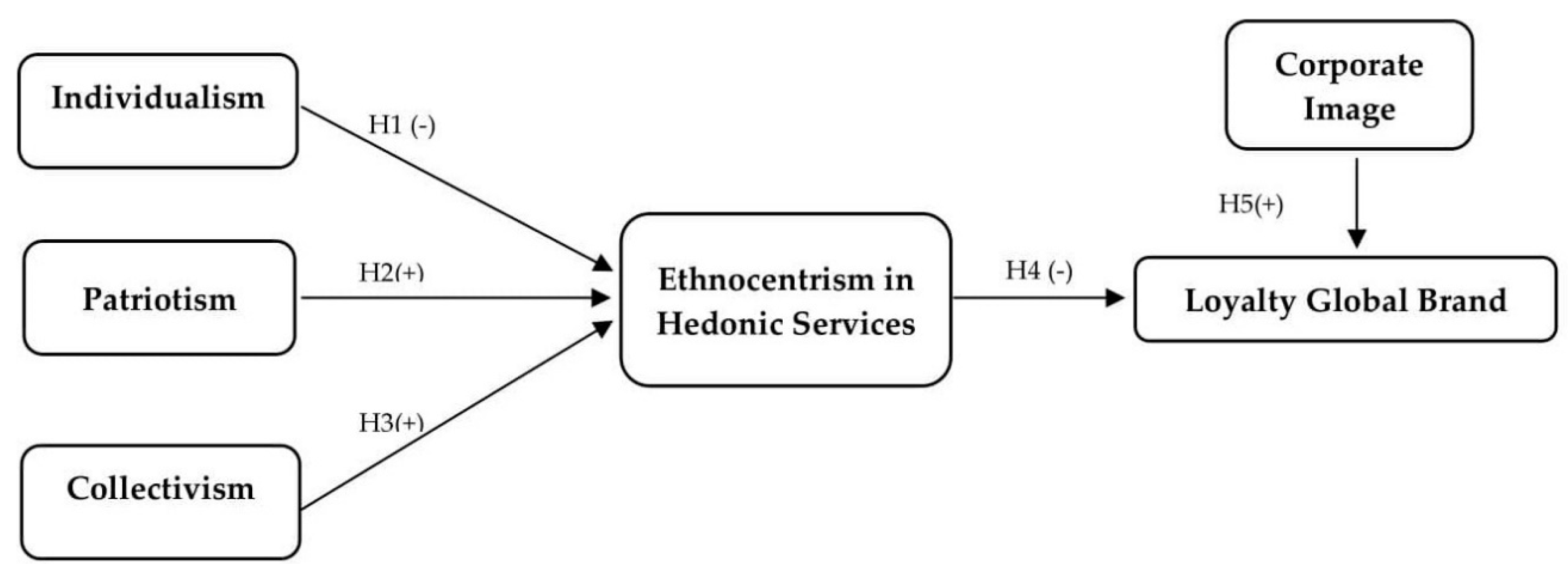

That is why the research presented has the following structure: after presenting the introduction, a literature check is conducted with SET as the main study variable over the variables patriotism, individualism, and collectivism; while loyalty is used as a consequence of the SET. On the other hand, image is used as an antecedent of loyalty. Therefore, it could be proposed that these relationships construct and present a theoretical model with its respective hypothesis. Next, the methodology used will be detailed to prove the previous hypothesis, which allows us to analyze the investigative work results. Finally, conclusions, implications, limitations, and future research lines are presented.

4. Analysis and Discussion of the Results

A descriptive summary of the results obtained in the study (see

Table 4) shows that the sampled participants possess an elevated ethnocentric character. All the measurements from this item are above 3.5 on a scale of 1 to 7 and 18 of the 24 items measured are above 4. Similarly, levels of patriotism are high given that five of the seven items are above 3.5. On the other hand, the sample also reflects an elevated collectivist character as seven of the eight items rated above 5. Nonetheless, a medium to high level of individualism is also observed given that four of the eight items are above 5. This result reflects the observations made by Robles et al. [

51] that, despite the collectivist character of Colombian society, it is also highly oriented towards success achieved in a competitive market. The resulting rivalry generated with other groups and even with other social classes increases status Hofstede [

52]. In contrast, loyalty towards Starbucks is relatively moderate whilst their image is highly rated. This can be understood as a result of the hedonic nature of their service.

The collected data were analyzed in two stages. The first stage consisted of validating the measuring instrument and in the second stage the structural model was assessed, Barclay et al. [

71]. Partial least squares regression was applied using Smart PLS version 3.0.

This technique was chosen due to the fact that the use of PLS continues gaining traction as it is employed in diverse marketing studies and at an international level. It allows the inclusion of both formative and reflective constructs, Diamantopoulos [

72]. In our case, the image construct was considered formative based on a study carried out previously by Palacios-Florencio et al. [

61] who considered that the construction of image includes formative indicators. In the analysis of these constructs, the weights factor must be analyzed instead of the factor loadings, Chin [

73]. The authors acknowledged the possible multicollinearity of formative indicators, Roldán [

74] On the other hand, modeling via PLS sought to predict the dependent variables, allowing the maximum expression of the R

2 ratio of the explained variance of the dependent variables. This allowed estimations of the parameters to be based on the capacity to minimize residual endogenous variance. In this case, PLS permits a better adaption to predictive studies when compared with other tools, Barroso [

75]. The decision to use PLS is also justified due to the predictive nature of this study, plus the fact that in this study, the image construct is considered a construct with formative indicators.

The evaluation of the measurement model required analysis of the internal consistency of the scale, individual item reliability, and convergent and discriminant validity, Barclay et al.; Barroso et al. [

71,

72,

73,

74,

75]. To analyze the reliability of reflective constructs, the Cronbach α coefficient of composite reliability and the extracted average variance (AVE) were used. All values obtained via the Cronbach α values such as composite reliability showed scores above 0.7 although the AVE of patriotism is the only variable with a value below 0.5. In contrast, two of the items of the patriotism variable (PT8 and PT9) have loadings of less than 0.6 while the SET variable of the item (SET12) has a loading of less than 0.5. With these results in mind, and after carrying out the respective eliminations, when PT8 and PT9 are eliminated it is observed that the AVE of the patriotism variable is above 0.5. The item SET12 was also eliminated due to its loading below 0.5.

From the results presented in

Table 4, we can affirm the reliability and convergent validity of the scales used for measuring the different variables included in our model. Since the image variable is defined as a formative construct, its evaluation is made at the indicator level and via the evaluation of possible multicollinearity using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) and determination of the significance of weights. With respect to the FIV, all the items have a loading of less than 0.3 while the weight of four items (IMAG1, IMAG2, IMAG4, and IMAG6) is not significant. These indicators are eliminated from the results shown in

Table 5 due to their non-compliance with the previously outlined criteria.

Finally, to confirm the discriminant validity, an evaluation was made using the criteria put forward by Fornell [

76] and the Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio (HTMT), Henseler et al. [

77]. In relation to the criteria of Fornell [

76], the square root of the AVE of each variable should be greater than the correlations that this has with the other variables of the model. As can be observed in

Table 6, all the square roots of the AVE of each construct are greater than the correlation with any other construct in the model, Fornell [

76]. With respect to the (HTMT) ratio, authors such as Henseler et al. [

77] consider 0.90 as an appropriate maximum cut-off value. As can be observed in

Table 7, all the values of the (HTMT) ratio are below 0.9.

Once the psychometric properties of the measurement instrument were assessed, the analysis of the structural model via PLS proceeded based on the same criteria as was employed to calculate the significance of the parameters (a process of bootstrapping, of 5000 sub-samples of the size of the original sample was carried out). The R2 obtained via bootstrapping was the first stage in the evaluation of the predictive capacity of the structural model. This indicated the degree of variance in a construct explained by the predictor variables of the construct in the model.

In relation to the predictive power of the model, the criteria proposed by Falk et al. [

78] were followed. They considered that the minimum R

2 value is 0.1; this value indicates that the model presents a minimum level of significance.

Table 8 shows that the R

2 value of all the dependent factors is above 0.1 (as per the critical level). Next, the predictability of the model was evaluated by applying the Stone–Geisser (Q

2) test to each dependent construct via the blindfolding procedure. As can be observed in

Table 8, none of the Q

2 values had a score of zero or below zero which indicates the predictive relevance of the endogenous variables. After using the R

2 calculation to check the predictive power of the model—a measurement that determines the amount of variance of the endogenous variables, explained by the constructs they predict—levels of between 0 and 1 should result. As can be observed in

Table 8, all the values are above the established limit and as such, the previously formulated hypotheses possess an adequate predictive level that permits the assessment of the significance of the previously stated relationships.

The positive link that exists between patriotism and SET is evidenced by the results obtained. As such, the Hypothesis H1 is confirmed. Due to this and according to the significance of the relationship previously stated, it can be confirmed that this construct wields a positive and significant effect on SET (β = 0.312; p < 0.000). In the same way, collectivism also has a positive and significant influence on SET. This leads to the confirmation of Hypothesis H3 (β = 0.254; p < 0.000). Apart from this, a negative relationship is observed between individualism and SET, allowing us to confirm Hypothesis H2. Considering the significance of this result, we can conclude that individualism has a negative and statistically significant effect on SET (β = −0.100; p < 0.036). According to the results obtained, a positive and statistically significant relationship exists between SET and loyalty towards foreign brands (β = 0.148; p < 0.001), thus rejecting Hypothesis 4, given that this was proposed as a negative relationship between the two constructs. One possible explanation for this result is the hedonic nature of the service that Starbucks provides, as previously mentioned. The sample, however, is made up of a largely youthful public, 81% of those interviewed were aged between 18 and 35 and the majority had tertiary studies. For this segment of the population, foreign services generate a status that allows them to rise above the rest, socially speaking. This may explain their loyalty, in a positive sense, towards the brand. Finally, based on the information obtained, a positive and significant link exists between brand image and consumer loyalty. With this finding, Hypothesis H5 is also confirmed (β = 0.612; p < 0.000).