Corporate Social Responsibility during COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The COVID-19 Pandemic: Sanitary, Economic, and Social Consequences in the Spanish Setting

3. Literature Review

4. Choosing Well, Doing Good during the COVID-19 Pandemic

5. Methods

5.1. Population and Sample

5.2. Methodology

6. Results

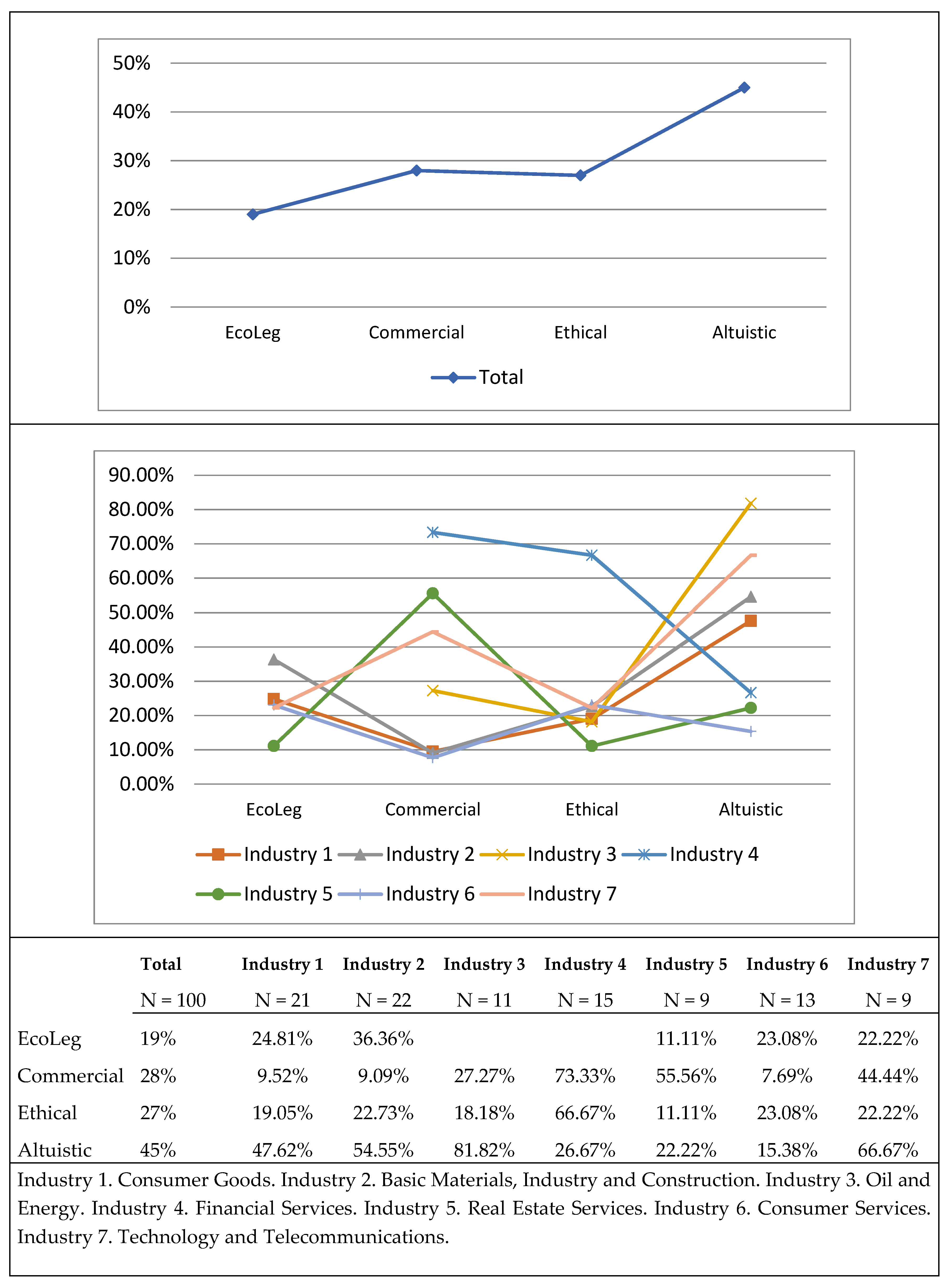

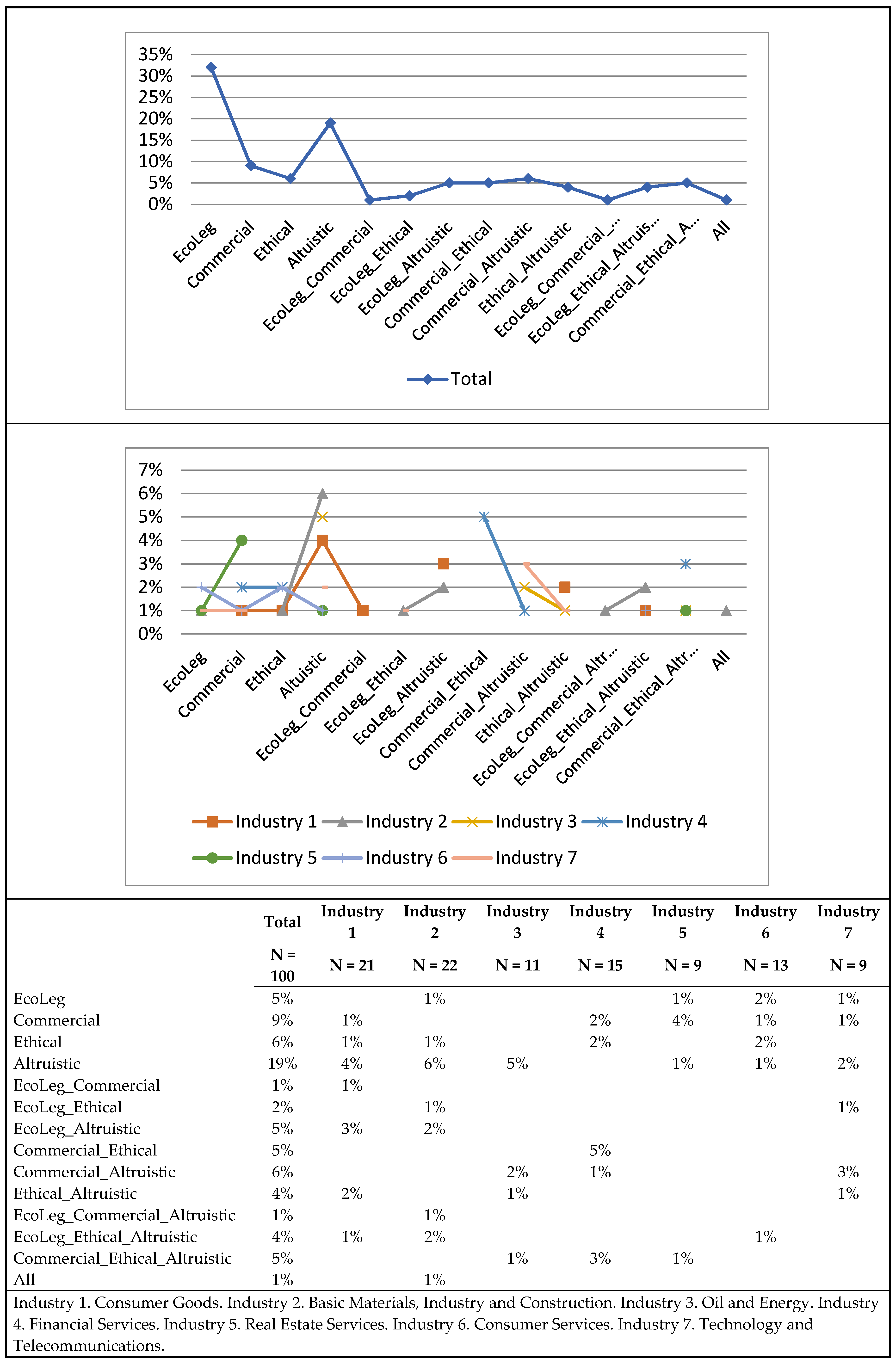

6.1. Descriptive Analysis of CSR Practices in the Face of the COVID-19 Pandemic

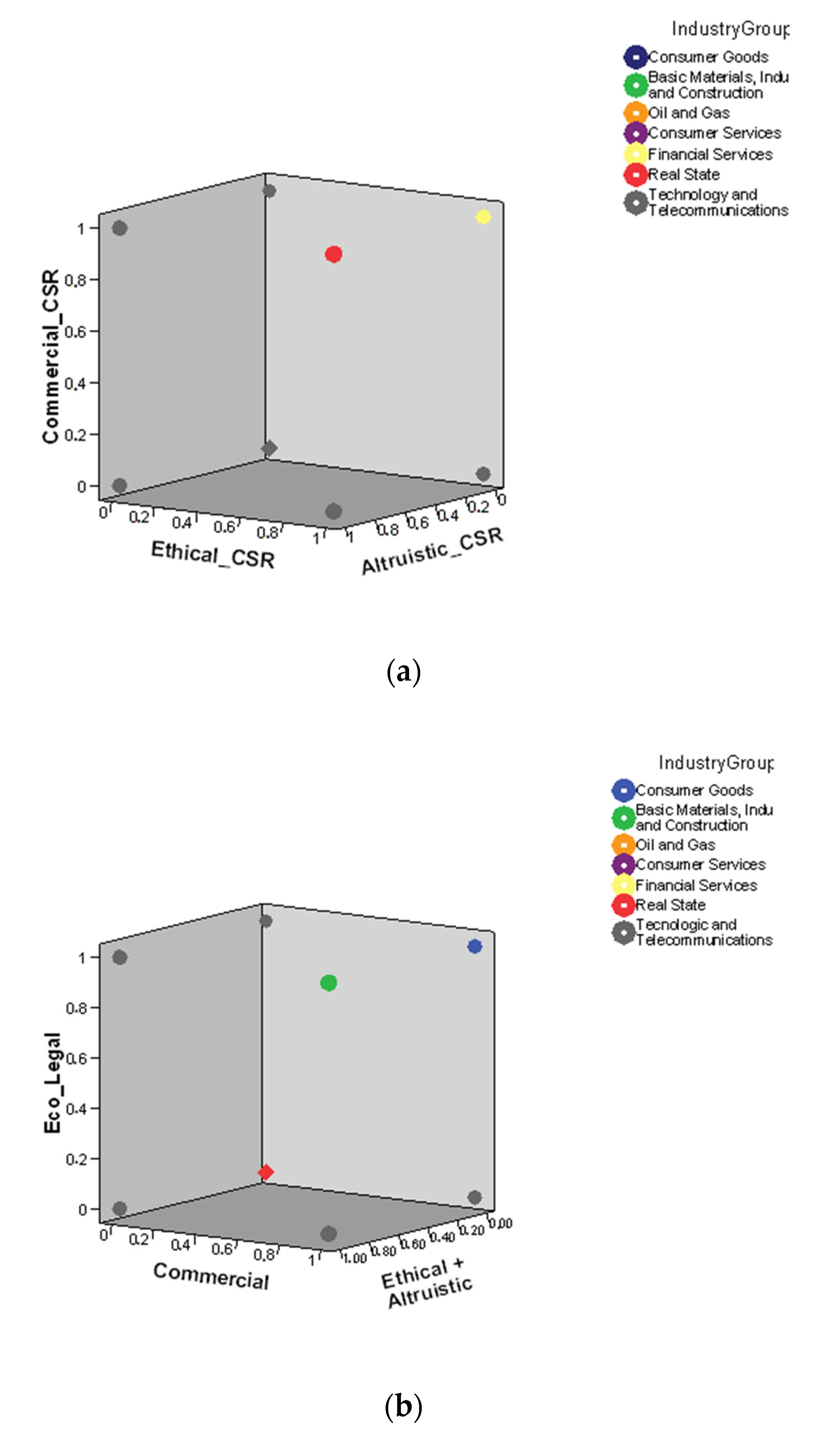

6.2. CSR and Industry Cluster Policies

7. Discussion of Results and Implications

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IMF. IMF World Economic outlook, abril de 2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.imf.org/es/Publications/WEO/Issues/2020/04/14/weo-april-2020 (accessed on 22 October 2020).

- OECD. Evaluating the Initial Impact of COVID-19 Containment Measures on Economic Activity. 2020. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/evaluating-the-initial-impact-of-covid-19-containment-measures-on-economic-activity/ (accessed on 22 October 2020).

- ILO. COVID-19 and the World of Work. 2020. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/coronavirus/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 22 October 2020).

- Aguinis, H.; Villamor, I.; Gabriel, K.P. Understanding employee responses to COVID-19: A behavioral corporate social responsibility perspective. Manag. Res. 2020, 18, 421–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Harris, L. The impact of Covid-19 pandemic on corporate social responsibility and marketing philosophy. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 116, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brammer, S.; Branicki, L.; Linnenluecke, M. COVID-19, societalization and the future of business in society. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2020, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ABC. Cuando el proveedor de material sanitario se llama Inditex. Available online: https://www.abc.es/espana/galicia/abci-coronavirus-galicia-cuando-proveedor-material-sanitario-llama-inditex-202004200035_noticia.html (accessed on 20 April 2020).

- CEOE. Especial impacto coronavirus. 2020. Available online: https://www.ceoe.es/es/contenido/actualidad/noticias/el-pib-caera-entre-un-5-y-un-9-en-2020-por-el-covid-19-y-el-paro-crecera-en-mas-de-medio-millon-de-personas (accessed on 22 October 2020).

- Kulachinskaya, A.; Akhmetova, I.G.; Kulkova, V.Y.; Ilyashenko, S.B. The Challenge of the Energy Sector of Russia during the 2020 COVID-19 Pandemic through the Example of the Republic of Tatarstan: Discussion on the Change of Open Innovation in the Energy Sector. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Objectives Report 2019; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- García-Sánchez, I.M.; Aibar-Guzmán, B.; Aibar-Guzmán, C.; Rodríguez-Ariza, L. “Sell” recommendations by analysts in response to business communication strategies concerning the Sustainable Development Goals and the SDG compass. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 255, 120194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, I.M.; Rodríguez-Ariza, L.; Aibar-Guzmán, B.; Aibar-Guzmán, C. Do institutional investors drive corporate transparency regarding business contribution to the sustainable development goals? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 2019–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponkratov, V.; Kuznetsov, N.; Bashkirova, N.; Volkova, M.; Alimova, M.; Ivleva, M.; Vatutina, L.; Elyakova, I. Predictive Scenarios of the Russian Oil Industry; with a Discussion on Macro and Micro Dynamics of Open Innovation in the COVID 19 Pandemic. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex 2020, 6, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deliu, D. The Intertwining between Corporate Governance and Knowledge Management in the Time of Covid-19—A Framework. J. Emerg. Trends Mark. Manag. 2020, 1, 93–110. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, M. Value-enhancing capabilities of CSR: A brief review of contemporary literature. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 127, 419–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Dou, J.; Jia, S. A meta-analytic review of corporate social responsibility and corporate financial performance: The moderating effect of contextual factors. Bus. Soc. 2015, 55, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lins, K.; Servaes, H.; Tamayo, A. Social capital, trust, and firm performance: The value of corporate social responsibility during the financial crisis. J. Financ. 2017, LXXII, 1725–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Gomez, S.; Arco-Castro, M.L.; Lopez-Perez, M.V.; Rodríguez-Ariza, L. Where does CSR come from and where does it go? A review of the state of the art. Adm. Sci. 2020, 10, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiral, O. Sustainability reports as simulacra? A counter-account of A and A+ GRI reports. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2013, 26, 1036–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiral, O. Accounting for the Unaccountable: Biodiversity Reporting and Impression Management. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 135, 751–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghesi, R.; Houston, H.; Naranjo, S. Corporate socially responsible investments: CEO altruism, reputation and shareholder interests. J. Corp. Financ. 2014, 26, 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köbel, J.F.; Busch, T.; Jancso, L.M. How media coverage of corporate social irresponsibility increase financial risks. Strateg. Manag. J. 2017, 38, 2266–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Pecharromán, X. Las empresas dan muestra de su compromiso social ante el Covid-19. Buen Gobierno 2020, 33, 3–7. Available online: http://eleconomista.com/ (accessed on 22 October 2020).

- Verma, S.; Gustafsson, A. Investigating the emerging COVID-19 research trends in the field of business and management: A bibliometric analysis approach. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 118, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haessler, P. Strategic Decisions between Short-Term Profit and Sustainability. Adm. Sci. 2020, 10, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garriga, E.; Melé, D. Corporate Social Responsibility Theories: Mapping the Territory. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 53, 52–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melé, D. Business Ethics in Action, Seeking Human Excellence in Organizations; Palgrave, Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Melé, D. The firm as a “community of persons”: A pillar of humanistic business ethos. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 106, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, E.R. Modelling CSR: How Managers Understand the Responsibilities of Business Towards Society. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 91, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprinkle, G.B.; Maines, L.A. The benefits and costs of corporate social responsibility. Bus. Horiz. 2010, 53, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Carlo, E. The Real Entity Theory and the Primary Interest of the Firm: Equilibrium Theory, Stakeholder Theory and Common Good Theory. Chapter 1. In Accountability, Ethics and Sustainability of Organizations; New Theories, Strategies and Tools for Survival and Growth; Brunelli, S., Di Carlo, E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Akremi, A.; Gond, J.P.; Swaen, V.; DeRoeck, K.; Igalens, J. How do employees perceive corporate responsibility? Development and validation of a multidimensional corporate stakeholder responsibility scale. J. Manag. 2015, 44, 619–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, O.; Rupp, D.E.; Farooq, M. The multiples pathways through which internal and external corporate social responsibility influence organizational identification and multifoci outcomes: The moderating role of cultural and social orientations. Acad. Manag. J. 2017, 60, 954–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate social performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.M.; Park, S.Y.; Lee, H.J. Employee perception of CSR activities: Its antecedents and consequences. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1716–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DellaVigna, S.; List, J.; Malmendier, U. Testing for altruism and social pressure in charitable giving. Q. J. Econ. 2012, 127, 1–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnea, A.; Rubin, A. Corporate social responsibility as a conflict between shareholders. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 97, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, I.M.; Martínez-Ferrero, J. Chief Executive Officer ability, Social Responsibility and financial performance: The moderating role of the environment. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2019, 28, 542–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, I.M.; Hussain, N.; Martínez-Ferrero, J. An empirical analysis of the complementarities and substitutions between effects of CEO ability and corporate governance on socially responsible performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 1288–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, I.M. The moderating role of board monitoring power in the relationship between environmental conditions and corporate social responsibility. Bus. Ethics 2020, 29, 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desardine, M.; Bansal, P. One Step Forward, Two Steps Back: How Negative External Evaluations Can Shorten Organizational Time Horizons. Organ. Sci. 2019, 30, 761–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, I.M.; García-Meca, E. Do talented managers invest more efficiently? The moderating role of corporate governance mechanisms. Corp. Gov. 2018, 26, 238–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, I.-M.; García-Meca, E. Do able bank managers Exhibit specific attributes? An empirical analysis of their investment efficiency. Adm. Sci. 2020, 10, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souder, D.; Bromiley, P. Explaining temporal orientation: Evidence from the durability of firms’ capital investments. Strateg. Manag. J. 2012, 33, 550–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P.; DesJardine, M. Business sustainability: It is about time. Strateg. Organ. 2014, 12, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, C.; Bansal, P. Does long-term orientation create value? Evidence from a regression discontinuity. Strateg. Manag. J. 2017, 38, 1827–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, C.; Larraza-Kintana, M.; Garcés-Galdeano, L.; Berrone, P. Are family firms really more socially responsible? Entrep. Theory Pract. 2014, 38, 1295–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, I.M.; Araujo-Bernardo, C.A. What colour is the corporate social responsibility report? Structural visual rhetoric, impression management strategies, and stakeholder engagement. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1117–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, I.-M.; Hussain, N.; Khan, S.A.; Martínez-Ferrero, J. Do Markets Punish or Reward Corporate Social Responsibility Decoupling? Bus. Soc. 2020, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- More Than Research; Toluna. El consumidor español durante el confinamiento. 2020. Available online: https://www.distribucionactualidad.com/inditex-marca-valorada-coronavirus/ (accessed on 22 October 2020).

- Yun, J.J.; Liu, Z. Micro- and Macro-Dynamics of Open Innovation with a Quadruple-Helix Model. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.J.; Zhao, X.; Jung, K.; Yigitcanlar, T. The Culture for Open Innovation Dynamics. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valor, C.; Zasuwa, G. Quality reporting of corporate philanthropy. Corp. Commun. 2017, 22, 486–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelon, G.; Pilonato, S.; Ricceri, F. CSR reporting practices and the quality of disclosure: An empirical analysis. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2015, 33, 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farcane, N.; Deliu, D.; Bureană, E. A Corporate Case Study: The Application of Rokeach’s Value System to Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). Sustainability 2019, 11, 6612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Lockhart, J.; Bathurst, R. A multi-level institutional perspective of corporate social responsibility reporting: A mixed-method study. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 121739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Health Risks | Economic Risks at the Business Level | Socieconomic Risks |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Economic and Legal Responsibilities | Commercial CSR | CSR Ethics | Altruistic CSR | Strategic CSR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decisions that managers would make to guarantee the creation of value for shareholders, the job security of employees, and the quality of products and services. They suppose the fulfilment of laws and informal rules of the game | CSR actions closely related to business activity and aimed at obtaining economic benefits associated with attracting new customers or increasing the confidence of existing ones | Fair and equitable business decisions in order to avoid damages | Philanthropic actions aimed at preventing potential harm and alleviating negative externalities that affect the welfare state without necessarily entailing economic benefits for the company | Ethical and altruistic actions selected to guarantee the creation of value for shareholders and investors and aimed at generating benefits for the company through their impact on image and reputation |

| Industry | Population | Sample | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute | % | Absolute | % | |

| Consumer Goods | 29 | 18.24 | 21 | 21 |

| Basic Materials, Industry and Construction | 43 | 27.04 | 22 | 22 |

| Oil and Energy | 16 | 10.06 | 11 | 11 |

| Financial Services | 23 | 14.47 | 15 | 15 |

| Real Estate | 18 | 11.32 | 9 | 9 |

| Consumer Services | 20 | 12.58 | 13 | 13 |

| Technology and Telecommunications | 10 | 6.29 | 9 | 9 |

| TOTAL | 159 | 100 | ||

| 1. Investor Commitment: Economic Measures |

|---|

| INV.1. General letter to investors and other stakeholders with the company’s action plan to face the epidemic. Also available in other formats: video, webinars, etc. INV.2. Reorganization of productive activity INV.3. Approach focused on the preservation of liquidity (revalued measures depending on the evolution of the context):

|

| 2. Employee Commitment: Labor measures to ensure job security before COVID-19 |

EMP.1. Establishment of action protocols to guarantee occupational safety with measures focused on:

EMP.3. Special payment of between 250 and 1000 euros to each active employee during the period of confinement EMP.4. Free health and psychology office for employees and family EMP.5. Making educational technology platforms available to employees and their families EMP.6. Applause campaigns to employees at their jobs |

| 3. Customer Commitment: Commercial measures to ensure the continuity and quality of services |

CLI.1. Implementation of measures for the protection and security of general clients:

CLI.4. Design of specific products associated with the demands and opportunities of the COVID-19 situation |

| 4. Commitment to Suppliers and Partners: Liquidity measures and guarantees of continuity |

| SUP.1. Express commitment to pay all suppliers for orders placed SUP.2. Payment in advance or within 15 days to suppliers, creditors and collaborators to provide them with liquidity SUP.3. Special payment of between 250 and 1000 euros to collaborators (including franchisees) who work in the period of confinement SUP.4. Making sure that key suppliers and contractors have contingency plans that certify the continuity of their products or services and are coordinated with those of the company |

| 5. Society Commitment I: Cooperative initiatives with public institutions to contribute to the fight against this pandemic |

| SOC.1. Donation of creams and other pharmaceuticals, beds, cleaning equipment, medical supplies and personal protective equipment for front-line health workers and law enforcement agencies SOC.2. Programs to promote scientific research SOC.3. Campaigns to raise money from employees and other groups doubling each euro contributed by the participants to be used in the previously mentioned outreaches SOC.4. Commitment to the provision of services (energy, communications, etc.) and products (polypropylene, cellulose, etc.) that are necessary to face the health emergency SOC.5. Disposition of resources before the public administrations:

|

| 6. Society Commitment II: Social collaboration programs with different social agents |

SOC.7. Actions related to active public agents in the fight against the pandemic:

|

| 7. Society Commitment III: Other programs for society in general |

| SOC.10. Information campaigns in the media SOC.11. Blogs or Podcast with tips and recommendations on:

SOC.13. Actions related to students:

|

| TOTAL | INDUSTRY 1 | INDUSTRY 2 | INDUSTRY 3 | INDUSTRY 4 | INDUSTRY 5 | INDUSTRY 6 | INDUSTRY 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 100 | N = 21 | N = 22 | N = 11 | N = 15 | N = 9 | N = 13 | N = 9 | |

| INV_1 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

| INV_2 | 6.00% | 14.29% | 13.64% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| INV_3 | 13.00% | 9.52% | 22.73% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 11.11% | 23.08% | 22.22% |

| INV_4 | 10.00% | 4.76% | 9.09% | 0.00% | 20.00% | 0.00% | 15.38% | 22.22% |

| INV_5 | 6.00% | 4.76% | 0.00% | 27.27% | 13.33% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| EMP_1 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

| EMP_2 | 3.00% | 0.00% | 9.09% | 9.09% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| EMP_3 | 3.00% | 9.52% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 7.69% | 0.00% |

| EMP_4 | 0.01% | 0.00% | 0.01% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| EMP_5 | 0.01% | 0.00% | 0.01% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| EMP_6 | 1.00% | 0.00% | 4.55% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| CLI_1 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

| CLI_2 | 12.00% | 4.76% | 4.55% | 9.09% | 46.67% | 11.11% | 0.00% | 11.11% |

| CLI_3 | 25.00% | 9.52% | 9.09% | 27.27% | 66.67% | 55.56% | 0.00% | 33.33% |

| CLI_4 | 4.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 13.33% | 0.00% | 7.69% | 11.11% |

| SUP_1 | 3.00% | 4.76% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 13.33% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| SUP_2 | 4.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 9.09% | 20.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| SUP_3 | 1.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 7.69% | 0.00% |

| SUP_4 | 2.00% | 4.76% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 6.67% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| SOC_1 | 25.00% | 23.81% | 36.36% | 63.64% | 20.00% | 22.22% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| SOC_2 | 10.00% | 28.57% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 20.00% | 11.11% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| SOC_3 | 2.00% | 0.00% | 4.55% | 0.00% | 6.67% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| SOC_4 | 13.00% | 23.81% | 9.09% | 36.36% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 22.22% |

| SOC_5 | 21.00% | 9.52% | 40.91% | 18.18% | 0.00% | 11.11% | 15.38% | 55.56% |

| SOC_6 | 4.00% | 4.76% | 13.64% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| SOC_7 | 12.00% | 4.76% | 9.09% | 18.18% | 13.33% | 0.00% | 23.08% | 22.22% |

| SOC_8 | 14.00% | 9.52% | 22.73% | 9.09% | 13.33% | 0.00% | 15.38% | 22.22% |

| SOC_9 | 14.00% | 9.52% | 4.55% | 9.09% | 40.00% | 0.00% | 7.69% | 33.33% |

| SOC_10 | 2.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 15.38% | 0.00% |

| SOC_11 | 7.00% | 4.76% | 0.00% | 9.09% | 20.00% | 22.22% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| SOC_12 | 2.00% | 0.00% | 4.55% | 9.09% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| SOC_13 | 6.00% | 0.00% | 4.55% | 18.18% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 7.69% | 22.22% |

| CSR | Objective | COVID-19 Risks | Directs Actions | Indirect Actions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic and legal responsibilities | Guarantee the interests of shareholders, employees and customers in accordance with current regulations | Operational risks and liquidity and survival problems; new security risks for employees and customers | INV_2 INV_3 EMP_1 CLI_1 | INV_1 |

| Commercial CSR | CSR actions closely related to products and services | Business, individual, and family liquidity problems | CLI_3 CLI_4 | |

| Ethical CSR | Fair and equitable CSR actions in order to avoid damages | New security risks for employees and customers; liquidity and survival problems | EMP_2 EMP_3 CLI_2 INV_4 SUP_2 SUP_3 SUP_4 | EMP_6 SUP_1 |

| Altruist CSR | Philanthropic CSR actions aimed at preventing potential harm and alleviating negative externalities that affect the welfare state | Operational risks and liquidity problems; consequences of unemployment (including psychological help); health risks; need for training and leisure activities at home | INV_5 SOC_8 SOC_9 EMP_4 SOC_1 SOC_2 SOC_3 SOC_4 SOC_5 SOC_6 | SOC_12 SOC_7 SOC_10 SOC_11 EMP_5 SOC_13 |

| Health Risks | Economic Business Risks | Socioeconomic Risks |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Discovery of a vaccine or treatment against the disease: Investment in research and coordination of efforts 2. Need for sanitary material and protective equipment: manufacturing plants, stocks and logistics specialists 3. Need for more hospital areas for critically ill patients 4. Needs for facilities to accommodate mild and asymptomatic patients, unaffected elderly and other vulnerable groups | 1. New security risks for employees and customers:

3. Operating costs not correlated with income: Implementation of contingency plans and control systems to suppress unprofitable activities and lines 4. Coordination with suppliers and collaborators in the implementation of contingency plans to promote a win–win relationship. 5. Liquidity problems: Cash payment periods or within 15 days | 1. Unemployment: measures to revive the economy 2. Loss of income and emergence of situations of vulnerability: Aid programs for vulnerable groups taking advantage of the experience of the third sector 3. Globalized demand for psychological care due to the loss of loved ones or due to problems associated with the new personal and work situation: telephone or online clinics 4. Need for measures to alleviate the loneliness of patients and families: television campaigns For donation of mobiles, tablets, etc. 5. Need for training and leisure activities at home due to limited mobility: Development of educational and recreational apps and blogs with advice |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García-Sánchez, I.-M.; García-Sánchez, A. Corporate Social Responsibility during COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc6040126

García-Sánchez I-M, García-Sánchez A. Corporate Social Responsibility during COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity. 2020; 6(4):126. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc6040126

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía-Sánchez, Isabel-María, and Alejandra García-Sánchez. 2020. "Corporate Social Responsibility during COVID-19 Pandemic" Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 6, no. 4: 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc6040126

APA StyleGarcía-Sánchez, I.-M., & García-Sánchez, A. (2020). Corporate Social Responsibility during COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 6(4), 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc6040126