UWB Positioning in Complex Indoor Environments Based on UKF–BiLSTM Bidirectional Mutual Correction

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

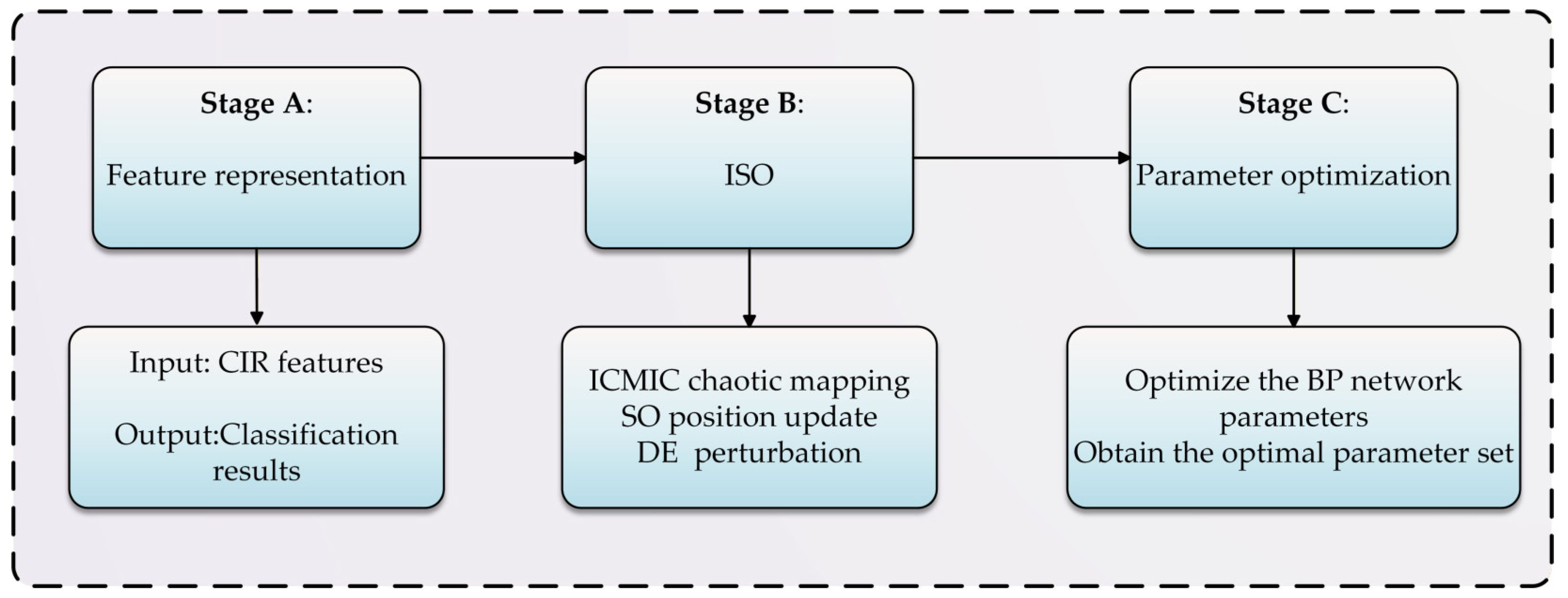

- An enhanced classification model is proposed by integrating multi-head self-attention (MHSA) with an improved snake optimization (ISO) algorithm. The self-attention mechanism captures correlations among channel impulse response (CIR) features, while the optimization strategy adaptively searches for optimal network parameters, thereby improving classification accuracy and model robustness.

- (2)

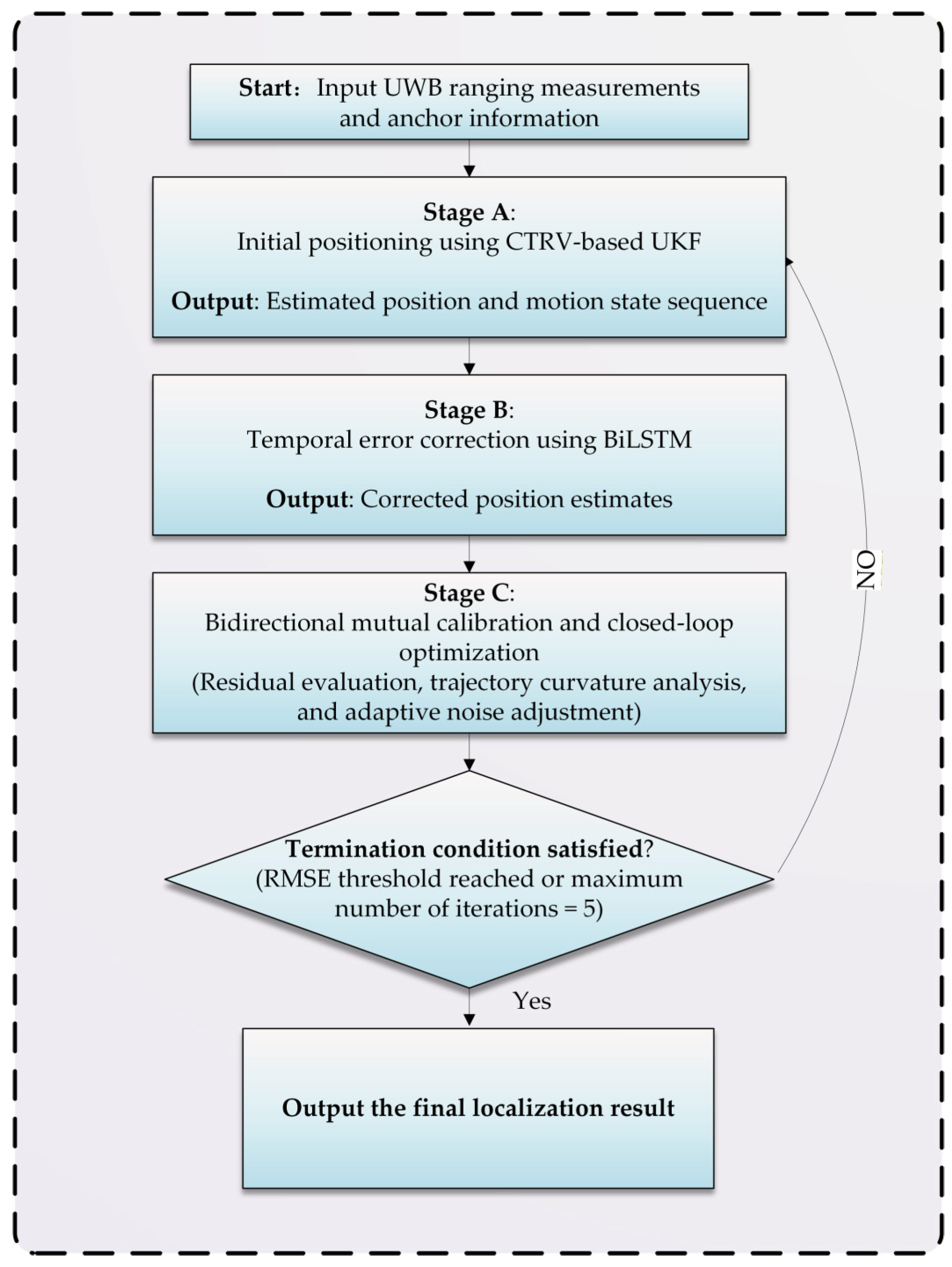

- A UKF–BiLSTM model with a bidirectional mutual calibration mechanism is proposed for NLOS error mitigation. The constant turn rate and velocity (CTRV) motion model is adopted to enhance the trajectory modeling capability of the UKF. Specifically, the UKF supplies physically constrained initial estimates to the BiLSTM. In turn, the BiLSTM leverages historical residuals to dynamically calibrate the UKF’s measurement noise statistics. This bidirectional interaction enables adaptive suppression of NLOS-induced errors under complex and time-varying conditions.

2. Related Work

2.1. Physics-Based Methods

2.2. Deep Learning-Based NLOS Mitigation

2.3. Hybrid Model-Based NLOS Mitigation

3. NLOS Identification Model

3.1. Analysis of Parameters Related to NLOS Recognition

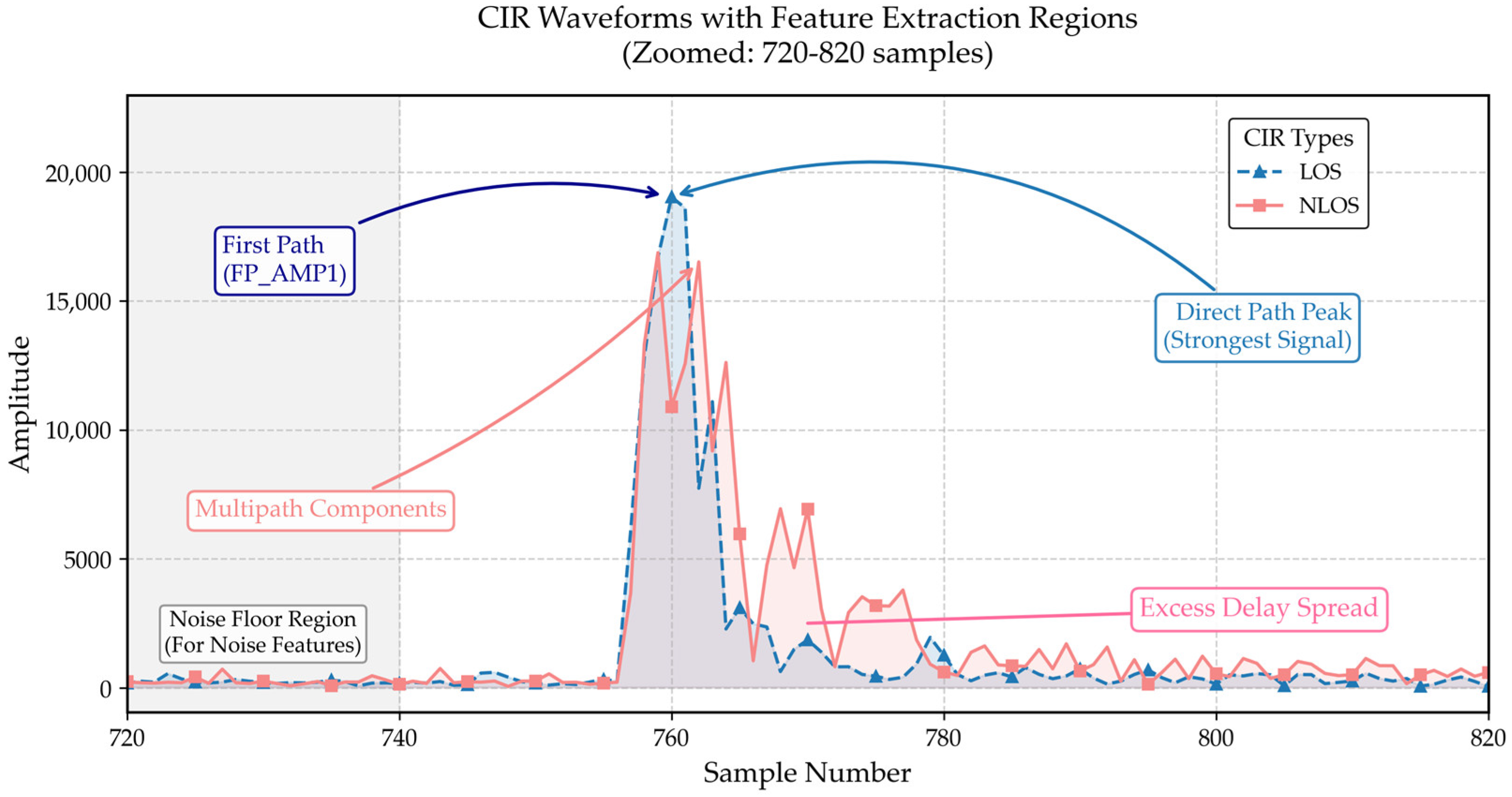

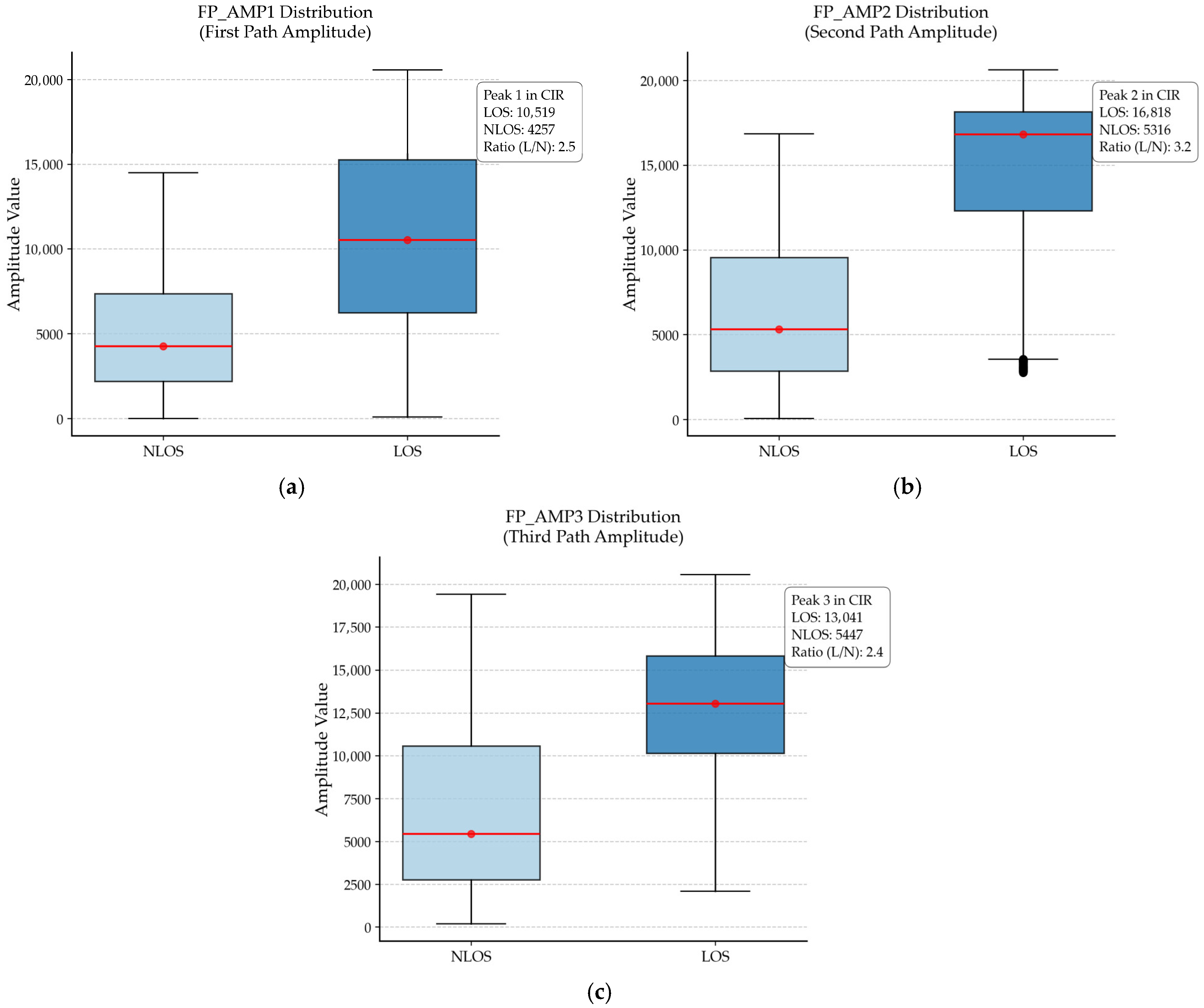

- (1)

- Direct path peak: under LOS conditions, a single sharp peak appears at approximately sample 760, with concentrated energy and rapid decay. This peak corresponds to the dominant direct path and represents a typical time-domain characteristic of LOS propagation.

- (2)

- Multipath components: in NLOS conditions, multiple low-amplitude peaks are distributed across the 750–800 sample range, indicating dispersed energy caused by rich multipath propagation.

- (3)

- First path (FP_AMP1): the first path is marked as the earliest significant peak in the LOS waveform, corresponding to the earliest arriving signal component. Its amplitude is therefore selected as an important discriminative feature.

- (4)

- Excess delay spread: under NLOS conditions, the CIR waveform exhibits an extended trailing response within the 760–780 sample interval, indicating temporal dispersion caused by signal propagation through reflected and diffracted paths.

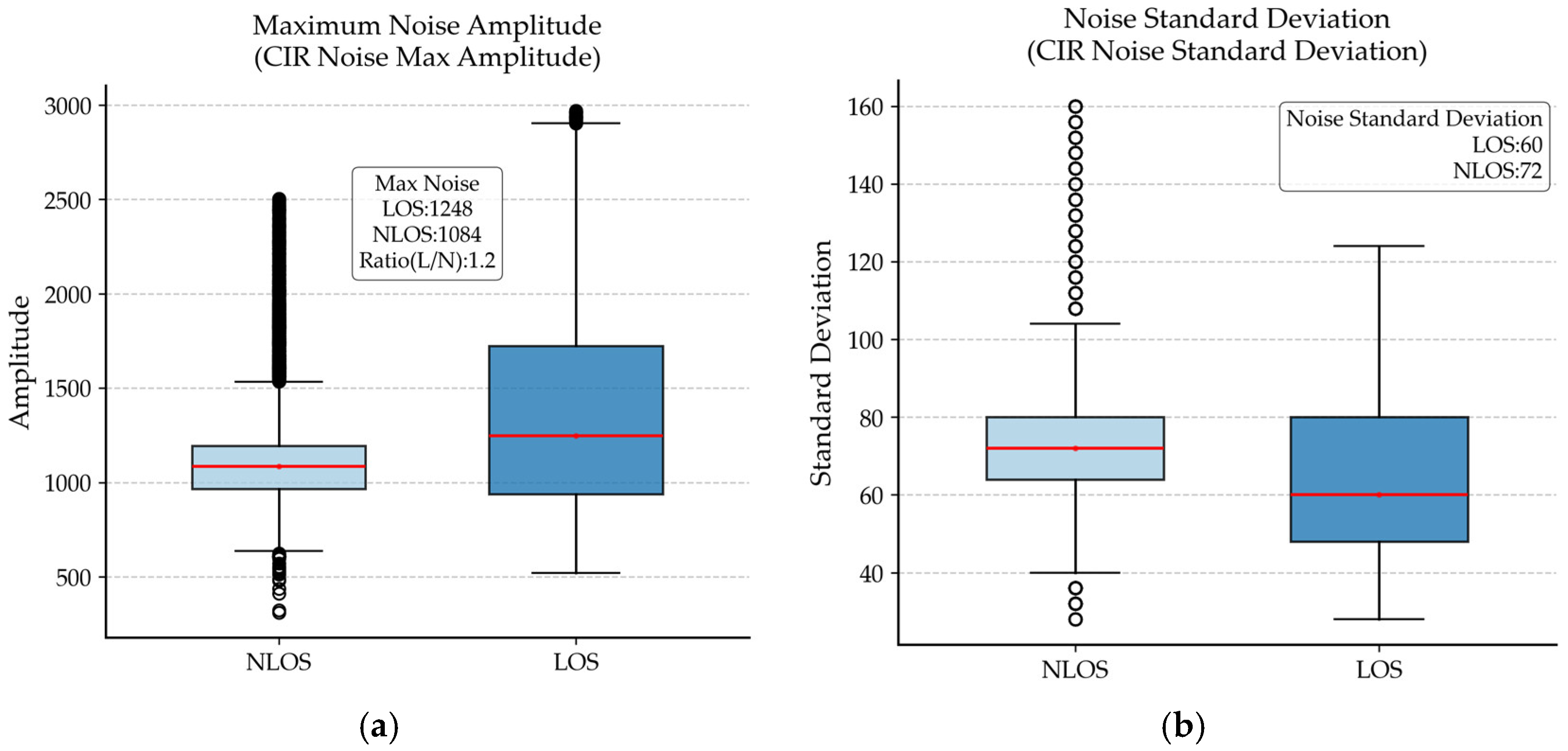

- (5)

- Noise floor region: the pre-arrival interval from samples 720 to 740 is designated as the noise floor region, from which noise-related statistical features, such as maximum noise amplitude and noise standard deviation, are extracted.

- (6)

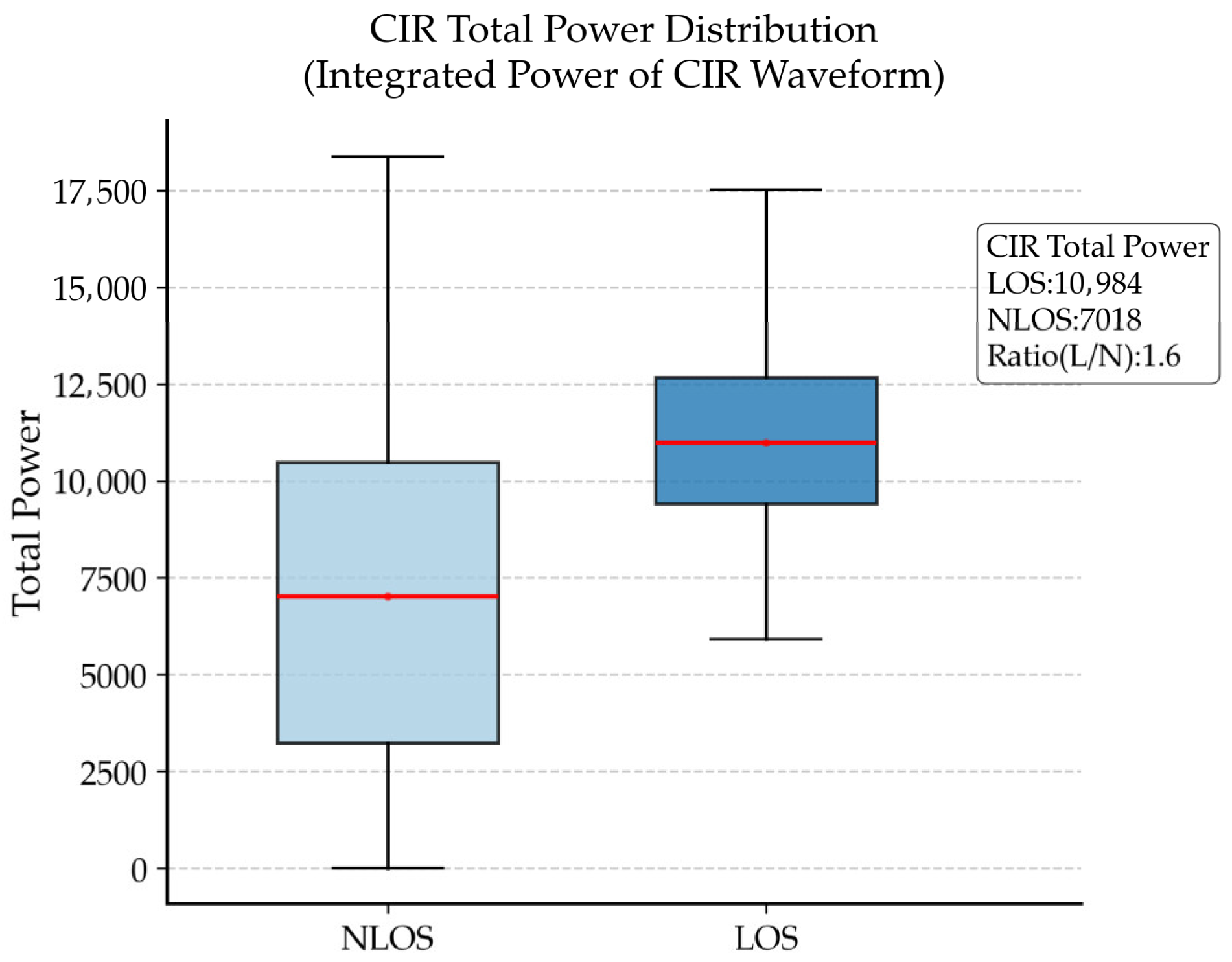

- Total power feature (CIR_PWR): CIR_PWR integrates the entire CIR waveform to represent the overall channel energy.

3.2. Snake Optimizer

3.3. ISO-MBP Model

- (1)

- Mutation: a mutant vector is generated for the current individual by randomly selecting three distinct individuals , , :where is the mutation factor, which is set to 0.3 in this study, and .

- (2)

- Crossover: a trial vector is generated using binomial crossover:where denotes the crossover probability, which is set to 0.8 in this study; is the index of the current dimension (); is a randomly selected dimension index that ensures at least one component is inherited from the mutant vector; and denotes a uniformly distributed random number in the interval .

- (3)

- Selection: the fitness values of the trial vector and the current individual are compared, and the better one is retained.

4. NLOS Error Mitigation Model

4.1. CTRV Model

4.2. UKF

- (1)

- Initialization: initialize the state and the corresponding covariance matrix .

- (2)

- Prediction step: according to Equations (23)–(25), a set of sigma points is generated and propagated through the state transition function to obtain the predicted sigma points . The predicted state mean and covariance are then computed as follows:where denotes the process noise covariance matrix.

- (3)

- Update step: regenerate the sigma points and compute the predicted observations:

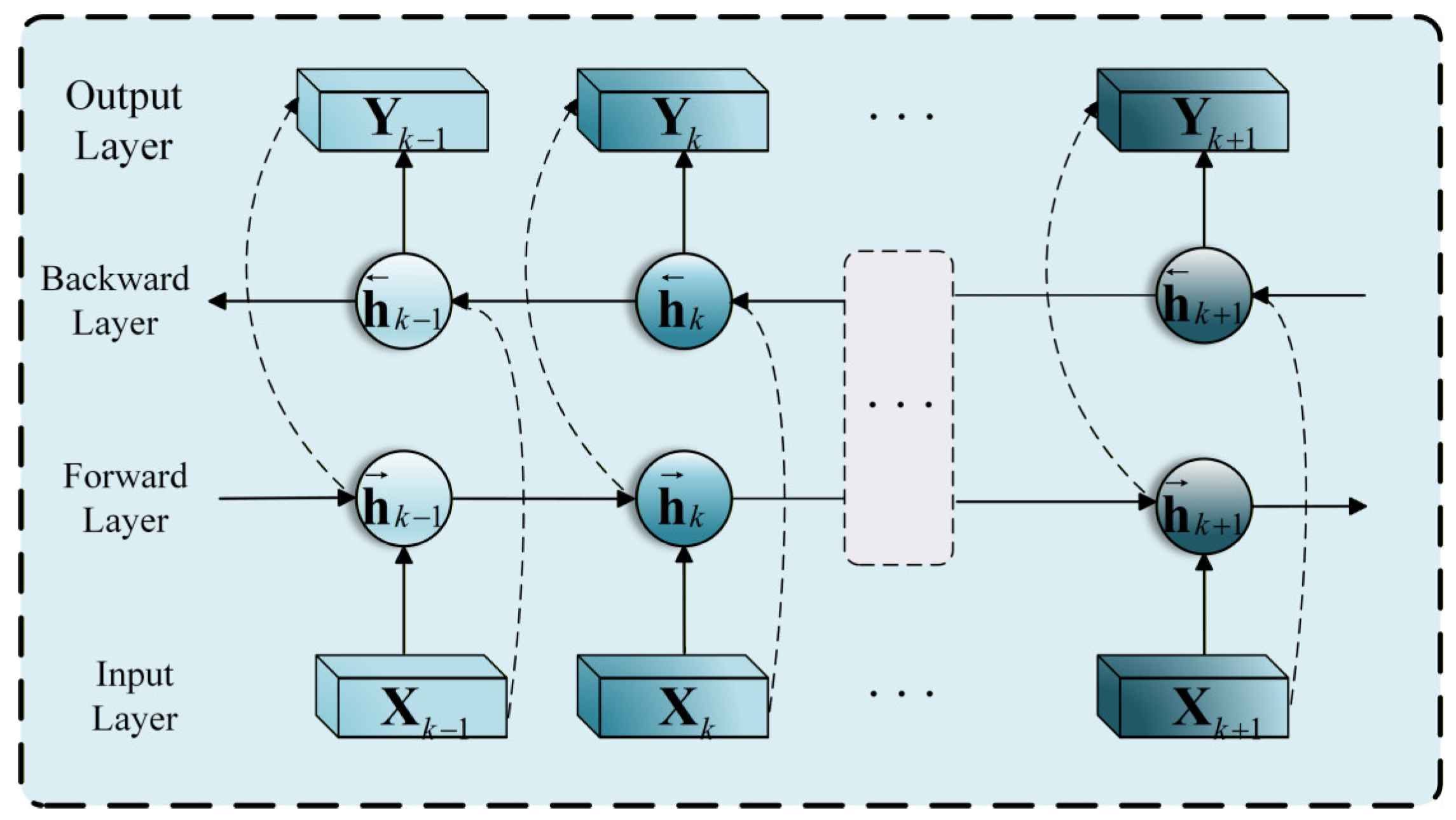

4.3. BiLSTM

- (1)

- Input layer: the layer is designed to receive input feature vectors , , and at time steps , and , where denotes the total input dimension. At each time step, the input integrates multi-source information:where is the vector of UWB ranging values, is the UKF state vector, and is the LSTM position estimate vector from the previous time step.

- (2)

- Forward LSTM layer: the layer processes the forward time sequence and computes the forward hidden states:

- (3)

- Backward LSTM layer: the layer processes the backward time sequence and computes the backward hidden states:

- (4)

- Output layer: the forward and backward hidden states are concatenated and passed through a fully connected layer to produce the final output:where is a linear projection layer.

4.4. UKF-BiLSTM Bidirectional Mutual Correction Model

- (1)

- Turning motion

- (2)

- Straight-line motion

5. Experimental Analysis

5.1. Dataset Description

- A.

- NLOS recognition dataset.

- B.

- NLOS error mitigation dataset.

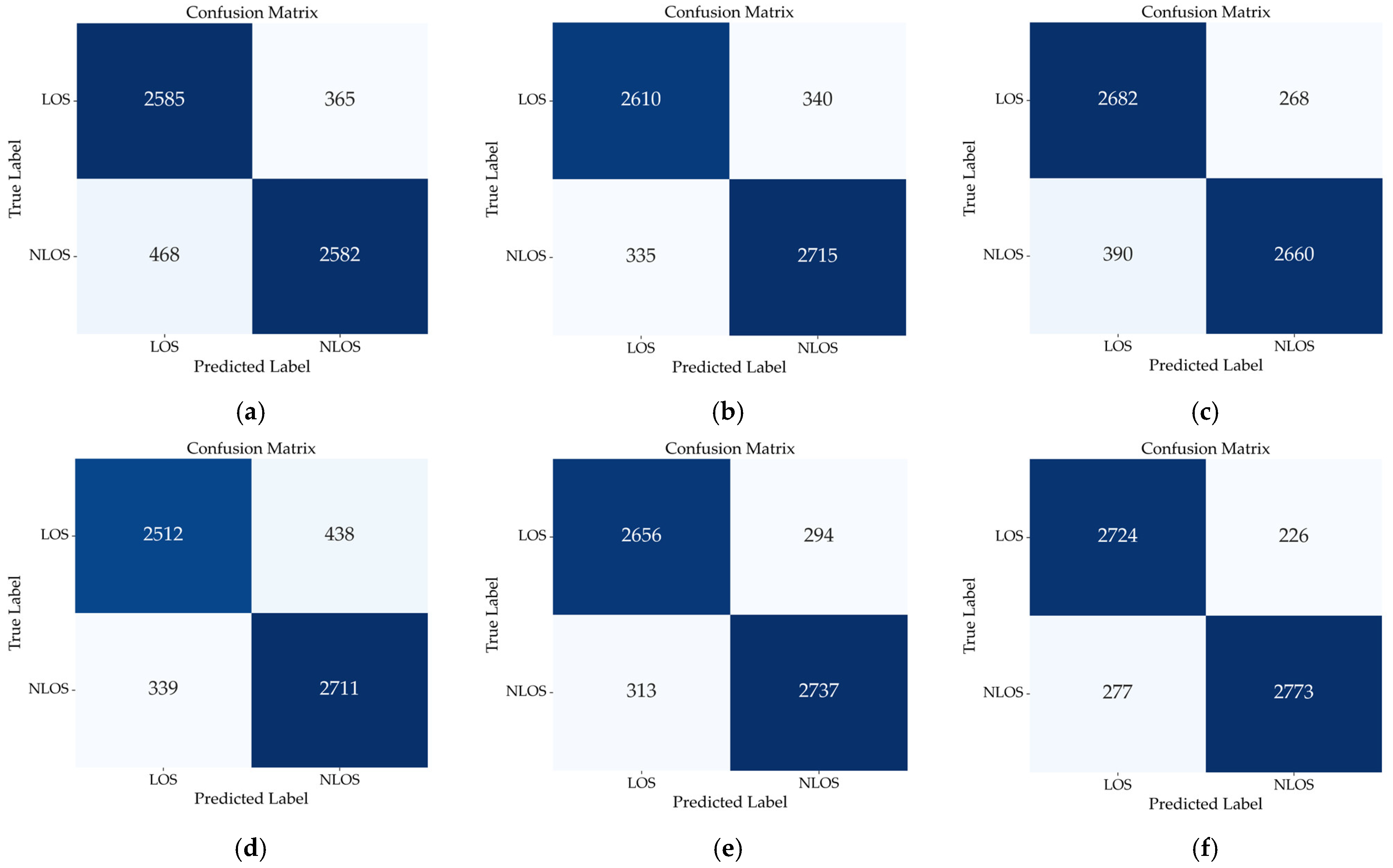

5.2. NLOS Identification Experiments

5.2.1. Configuration of Baseline Neural Network Models

5.2.2. Parameter Settings of Intelligent Optimization Algorithms

5.2.3. NLOS Classification Results

5.3. NLOS Error Correction Experiments

5.3.1. Unified Configuration of Comparative Models

5.3.2. Core Model Parameter Settings

5.3.3. Baseline Performance Evaluation

5.3.4. Comparative Analysis with State-of-the-Art Algorithms

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, X.; Zhang, C.; Peng, A. Enhanced propagation model constrained RSS fingerprints patching with map assistance for Wi-Fi positioning. Comput. Commun. 2023, 208, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galván-Tejada, C.E.; Carrasco-Jiménez, J.C.; Brena, R.F. Bluetooth-WiFi based combined positioning algorithm, implementation and experimental evaluation. Procedia Technol. 2013, 7, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Nie, B.; Zhang, R.; Zhai, S.; Li, H. ZigBee-based positioning system for coal miners. Procedia Eng. 2011, 26, 2406–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marano, S.; Gifford, W.M.; Wymeersch, H.; Win, M.Z. NLOS identification and mitigation for localization based on UWB experimental data. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2010, 28, 1026–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, L.; Brambilla, M.; Trabattoni, A.; Mervic, S.; Nicoli, M. UWB localization in a smart factory: Augmentation methods and experimental assessment. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez-González, J.; Ferrero-Guillén, R.; Verde, P.; Martínez-Gutiérrez, A.; Álvarez, R.; Torres-Sospedra, J. Time-based UWB localization architectures analysis for UAVs positioning in industry. Ad Hoc Netw. 2024, 157, 103419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Wen, K.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, K. A novel NLOS mitigation algorithm for UWB localization in harsh indoor environments. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2018, 68, 686–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Lian, Z.; Wang, P.; Wang, M.; Yue, Z.; Chai, H. Application of a long short-term memory neural network algorithm fused with Kalman filter in UWB indoor positioning. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eang, C.; Lee, S. An integration of deep neural network-based extended Kalman filter (DNN-EKF) method in ultra-wideband (UWB) localization for distance loss optimization. Sensors 2024, 24, 7643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Xu, Z.; Xia, J. Deep learning optimization positioning algorithm based on UWB/IMU fusion in complex indoor environments. Phys. Commun. 2025, 71, 102702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, E.; Zhu, Z.; Yi, J.; Wang, Y.; Kuai, E. UKF-FNN-RIC: A highly accurate UWB localization algorithm for TOA scenario. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 8508013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Bao, X.; Wei, Q.; Ma, Q.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Q. A Kalman filter for UWB positioning in LOS/NLOS scenarios. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Ubiquitous Positioning, Indoor Navigation and Location-Based Services (UPINLBS), Shanghai, China, 2–4 November 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Li, W.; Yang, G.; Jiao, Z.; Yan, J. Combining dilution of precision and Kalman filtering for UWB positioning in a narrow space. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5409. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Shmaliy, Y.S.; Ahn, C.K.; Tian, G.; Chen, X. Robust and accurate UWB-based indoor robot localisation using integrated EKF/EFIR filtering. IET Radar Sonar Navig. 2018, 12, 750–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.; Wei, M.; Li, S.; Wang, D. A fusion positioning system with environmental-adaptive algorithm: IPSO-IAUKF fusion of UWB and IMU for NLOS noise mitigation. Meas. Sens. 2025, 38, 101864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Wang, C.; He, C.; Zhuang, Y.; Xia, X.-G. Kalman-filter-based integration of IMU and UWB for high-accuracy indoor positioning and navigation. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 3133–3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, X. The IMU/UWB fusion positioning algorithm based on a particle filter. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2017, 6, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Wei, C.; Li, R.; Wang, J.; Yu, H. A novel cooperative localization method based on IMU and UWB. Sensors 2020, 20, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulose, A.; Han, D.S. UWB indoor localization using deep learning LSTM networks. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.T.A.; Lee, H.-G.; Jeong, E.-R.; Lee, H.L.; Joung, J. Deep learning-based localization for UWB systems. Electronics 2020, 9, 1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Yang, B.; Liu, T.; Zhang, H. Multi-Tag UWB Localization with Spatial-Temporal Attention Graph Neural Network. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 2531112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.; Yang, B.; Ding, K. Deep attention-based network combing geometric information for UWB localization in complex indoor environments. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 31488–31497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wang, Y.; Seow, C.K.; Sun, M.; Coene, S.; Huang, L.; Joseph, W.; Plets, D. Fuzzy Transformer Machine Learning for UWB NLOS Identification and Ranging Mitigation. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 8503817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Xu, S.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yu, T.; Lei, H. High-Precision UWB TDOA Localization Algorithm Based on UKF-FNN-CHAN-RIC. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 8506813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, M.; Wei, J.; Qin, J.; Guo, X.; Wang, H.; Li, S. Attention based LSTM framework for robust UWB and INS integration in NLOS environments. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthineni, K.; Artemenko, A.; Abode, D.; Vidal, J.; Nájar, M. PosGNN: A Graph Neural Network Based Multimodal Data Fusion for Indoor Positioning in Industrial Non-Line-of-Sight Scenarios. IEEE Open J. Veh. Technol. 2025, 7, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decawave. DW1000 User Manual; DecaWave Limited: Dublin, Ireland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hashim, F.A.; Hussien, A.G. Snake Optimizer: A novel meta-heuristic optimization algorithm. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2022, 242, 108320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bregar, K.; Hrovat, A.; Mohorcic, M. Nlos channel detection with multilayer perceptron in low-rate personal area networks for indoor localization accuracy improvement. In Proceedings of the 8th Jožef Stefan International Postgraduate School Students’ Conference, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 31 May 2016; Jožef Stefan International Postgraduate: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2016; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Bregar, K. Indoor UWB positioning and position tracking data set. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Y.; Chen, R.; Li, D.; Xiao, X.; Zheng, X. FCN-Attention: A deep learning UWB NLOS/LOS classification algorithm using fully convolutional neural network with self-attention mechanism. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2024, 27, 1162–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Deng, Z.; Tian, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Guo, J. A line-of-sight/non-line-of-sight recognition method based on the dynamic multi-level optimization of comprehensive features. Sensors 2025, 25, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hu, E.; Chen, Y.; Guo, C. Neurodynamic robust adaptive UWB localization algorithm with NLOS mitigation. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 14271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Env | Type | NLOS Conditions | Preprocessing |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Large residential apartment 9.18 × 12.06 m brick exterior + plasterboard interior | Few NLOS, only 5 outliers. | Basic deviation compensation |

| 1 | Compact residential apartment 3.60 × 6.69 m concrete exterior + plaster interior | Minimal NLOS, no abnormal values. | Basic deviation compensation |

| 2 | Industrial workshop 21.96 × 11.85 m dense metal equipment | High NLOS, strong multipath. | Basic deviation compensation DBSCAN denoising (metal reflection outliers) antenna delay compensation |

| 3 | Office 15.37 × 11.50 m concrete exterior + plasterboard partitions | Significant NLOS, 22 outliers. | Basic deviation compensation DBSCAN denoising (partition NLOS outliers) antenna delay compensation |

| Parameter Category | Parameter | BP Model | MBP Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Network architecture | Input layer | 10 | 10 |

| Hidden layer 1 | 150 | 150 | |

| Hidden layer 2 | 75 | 75 | |

| Output layer | 2 | 2 | |

| Training configuration | Attention mechanism | None | MHSA (6 heads) |

| Optimizer | Adam | Adam | |

| Learning rate | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| Training epochs | 200 | 200 |

| Parameter Category | Parameter | IPSO-MBP Model | ISO-MBP Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic configuration | Population size () | 10 | 10 |

| Maximum iterations () | 150 | 150 | |

| Parameter search range | |||

| Hybrid strategy | ICMIC chaotic map | ||

| DE scaling factor | |||

| DE crossover probability | |||

| Specific parameters |

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Model Parameters (K) | Training Time (s) | Inference Latency (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BP | 86.12% | 87.62% | 84.66% | 86.13% | 13.1 | 463 | 0.04 |

| MBP | 88.75% | 88.87% | 89.02% | 88.94% | 103.7 | 669 | 0.16 |

| ISO-BP | 89.03% | 90.85% | 87.21% | 88.91% | 13.1 | 411 | 0.07 |

| RF | 87.05% | 86.10% | 88.89% | 87.47% | 1.3 | 55 | 24.41 |

| IPSO-MBP | 89.88% | 90.30% | 89.74% | 90.02% | 103.7 | 1576 | 0.17 |

| FCN-Attention [31] | 88.24% | 85.85% | 91.56% | 88.62% | 1097.6 | - | 0.189 |

| DMOCF [32] | 93.50% | 93.52% | 93.70% | 93.61% | 15,090 | - | - |

| ISO-MBP | 91.62% | 92.46% | 90.92% | 91.67% | 103.7 | 1282 | 0.16 |

| Item | BiLSTM | CNN-LSTM | UKF-BiLSTM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input features | UWB ranging | -dim | -dim | -dim |

| UKF state | 5-dim | 5-dim | 5-dim | |

| Historical position | 2-dim | 2-dim | 2-dim | |

| Total feature dimension | + 7 | + 7 | + 7 | |

| Training configurations | Learning rate | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Optimizer | Adam | Adam | Adam | |

| Training epochs | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| Batch size | 32 | 32 | 32 | |

| Sequence length | 10 | 10 | 10 | |

| Hidden size | 64 | 128 | 64 | |

| Core architecture | Two-layer BiLSTM | CNN + three-layer LSTM | UKF–BiLSTM bidirectional mutual calibration | |

| Model | Parameter Category | Parameter Name | Env0 | Env1 | Env2 | Env3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BiLSTM | Network structure | Number of layers | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Hidden layer size | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | ||

| Sequence length | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | ||

| Training config | Learning rate | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| Batch size | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 | ||

| Training epochs | 100 | 100 | 300 | 100 | ||

| UKF | Initial state | Initial velocity | 0.4 m/s | 0.3 m/s | 0.8 m/s | 0.2 m/s |

| Process noise | Velocity noise | 0.15 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.08 | |

| Angular velocity noise | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.03 | ||

| Measurement noise | Measurement noise | 0.25 | 0.15 | 1.4 | 0.3 | |

| UKF params | Sigma params () | (0.1, 2, −2) | (0.1, 2, −2) | (0.01, 2, 0) | (0.1, 2, −2) | |

| Dynamic calibration | Q/R rate | 0.5/0.3 | 0.4/0.2 | 0.6/0.3 | 0.6/0.4 |

| Anchor | UKF/m | BiLSTM/m | Chan-Taylor/m | CNN-LSTM/m | UKF-BiLSTM/m |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 0.2228 | 0.0712 | 0.2653 | 0.5054 | 0.1108 |

| A2 | 0.2423 | 0.2809 | 0.4636 | 0.7742 | 0.1368 |

| A3 | 0.2292 | 0.3605 | 0.5717 | 0.6759 | 0.1505 |

| A4 | 0.2318 | 0.4049 | 0.6099 | 0.6554 | 0.1681 |

| A5 | 0.2151 | 0.4202 | 0.6192 | 0.8231 | 0.1774 |

| A6 | 0.2088 | 0.3454 | 0.6387 | 0.4710 | 0.1572 |

| A7 | 0.1896 | 0.2163 | 0.6537 | 0.5826 | 0.1435 |

| A8 | 0.2228 | 0.2496 | 0.3718 | 0.3575 | 0.1308 |

| Anchor | UKF/m | BiLSTM/m | Chan-Taylor/m | CNN-LSTM/m | UKF-BiLSTM/m |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 0.1572 | 0.1999 | 0.3060 | 0.1700 | 0.0798 |

| A2 | 0.1686 | 0.2074 | 0.3190 | 0.1263 | 0.1110 |

| A3 | 0.1378 | 0.1173 | 0.2958 | 0.1452 | 0.0768 |

| A4 | 0.1458 | 0.1214 | 0.2769 | 0.1479 | 0.0675 |

| A5 | 0.1759 | 0.1688 | 0.2051 | 0.1617 | 0.0640 |

| A6 | 0.1449 | 0.1542 | 0.2677 | 0.1830 | 0.0789 |

| A7 | 0.1330 | 0.1528 | 0.2461 | 0.1838 | 0.0675 |

| A8 | 0.1645 | 0.1950 | 0.2326 | 0.1678 | 0.0762 |

| Anchor | UKF/m | BiLSTM/m | Chan-Taylor/m | CNN-LSTM/m | UKF-BiLSTM/m |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 0.1720 | 0.2483 | 0.9699 | 0.2879 | 0.1573 |

| A2 | 0.1943 | 0.2614 | 1.0433 | 0.3735 | 0.1874 |

| A3 | 0.2394 | 0.2415 | 0.7547 | 0.2213 | 0.1906 |

| A4 | 0.2359 | 0.2426 | 0.7684 | 0.2065 | 0.2032 |

| A5 | 0.3163 | 0.2430 | 0.9395 | 0.2608 | 0.1933 |

| A6 | None | None | None | None | None |

| A7 | 0.4442 | 0.2172 | 0.8993 | 0.2469 | 0.1910 |

| A8 | 0.4150 | 0.2113 | 1.1244 | 0.2792 | 0.1849 |

| Anchor | UKF/m | BiLSTM/m | Chan-Taylor/m | CNN-LSTM/m | UKF-BiLSTM/m |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 0.3942 | 0.5320 | 0.3629 | 0.2460 | 0.0795 |

| A2 | 0.4419 | 1.0746 | 0.4576 | 0.2825 | 0.0964 |

| A3 | 0.5085 | 1.4742 | 0.4954 | 0.2906 | 0.0924 |

| A4 | 0.4570 | 1.1876 | 0.4439 | 0.2007 | 0.1123 |

| A5 | 0.3361 | 0.6734 | 0.3446 | 0.1765 | 0.1070 |

| A6 | 0.4036 | 0.5870 | 0.4151 | 0.2202 | 0.0775 |

| A7 | 0.3378 | 1.4528 | 0.3445 | 0.2053 | 0.1068 |

| A8 | 0.3559 | 0.6817 | 0.3631 | 0.2010 | 0.1153 |

| Environment | 3 Anchors | 4 Anchors | 6 Anchors | 7 Anchors | 8 Anchors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.2843 | 1.2756 | 0.2293 | - | 0.1800 |

| 1 | 0.2195 | 0.1729 | 0.1887 | - | 0.2129 |

| 2 | 1.1390 | 0.6590 | 0.4681 | 0.6249 | - |

| 3 | 2.1912 | 1.2607 | 0.3775 | - | 0.4219 |

| Method | Dataset | Scenario/Subset | RMSE (m) | MAE (m) | Parameters (K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F-BERT [21] | Private | STA-1 | 0.2537 | - | - |

| STA-2 | 0.2652 | ||||

| STA-3 | 0.1337 | ||||

| STA-4 | 0.1029 | ||||

| STA-GNN-M [23] | Private | N-4 | 0.140 | - | 266.5 |

| N-9 | 0.150 | ||||

| N-1 | 0.224 | ||||

| N-7 | 0.149 | ||||

| CNN-LSTM-DEKF [10] | Private | Laboratory | 0.205 | 0.192 | - |

| AR-PNN [33] | Public | Env0 | 0.14 | - | - |

| Ours | Public | Env0 | 0.1389 | 0.1053 | 82.2 |

| Env1 | 0.1158 | 0.0891 | 141.1 | ||

| Env2 | 0.2106 | 0.1756 | 142.7 | ||

| Env3 | 0.1024 | 0.0761 | 81.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Dong, Z. UWB Positioning in Complex Indoor Environments Based on UKF–BiLSTM Bidirectional Mutual Correction. Electronics 2026, 15, 687. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15030687

Wang Y, Dong Z. UWB Positioning in Complex Indoor Environments Based on UKF–BiLSTM Bidirectional Mutual Correction. Electronics. 2026; 15(3):687. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15030687

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yiwei, and Zengshou Dong. 2026. "UWB Positioning in Complex Indoor Environments Based on UKF–BiLSTM Bidirectional Mutual Correction" Electronics 15, no. 3: 687. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15030687

APA StyleWang, Y., & Dong, Z. (2026). UWB Positioning in Complex Indoor Environments Based on UKF–BiLSTM Bidirectional Mutual Correction. Electronics, 15(3), 687. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15030687