1. Introduction

Terahertz communication technology, with its vast available bandwidth, is widely regarded as one of the key enabling technologies for the future sixth-generation (6G) wireless communication systems. In recent years, it has attracted extensive research interest from both academia and industry [

1]. To achieve extremely high data rates, orthogonal frequency division multiplexing (OFDM) has become the primary physical-layer waveform candidate for terahertz communication systems, owing to its high spectral efficiency and strong resistance to multipath fading [

2]. However, at terahertz frequencies, communication systems face unprecedented phase noise challenges. The phase perturbations introduced by radio frequency oscillators not only cause a common rotation across all subcarriers, known as common phase error (CPE), but also destroy the orthogonality among subcarriers, leading to severe inter-carrier interference (ICI), which significantly limits system performance [

3].

To address this critical challenge, researchers have developed various phase noise suppression techniques, which can be broadly categorized into two classes: model-driven traditional signal processing methods and data-driven machine learning approaches [

4,

5]. Model-driven methods typically rely on pilots and explicit assumptions. In broadband terahertz scenarios, such methods often require dense pilot patterns and incur high computational complexity. Learning-based approaches can learn the compensation mapping directly from data; however, under practical operating conditions, it remains challenging for a single network architecture to simultaneously achieve reliable long-range phase tracking and effective suppression of composite impairments.

To overcome the limitations of existing phase noise compensation schemes in photonic terahertz OFDM system, this paper proposes a novel dual-branch adaptive compensation network named AdaPhaseNet. In this architecture, the Transformer branch focuses on the long-range temporal estimation and compensation of phase noise, while the CNN branch is responsible for enhancing the local features of the received signal to suppress non-phase impairments such as additive noise. The outputs of the two branches are dynamically weighted and fused in an adaptive fusion module, based on confidence scores provided by the Transformer branch, to generate the optimized signal. System performance is evaluated using two key metrics, bit error rate (BER) and error vector magnitude (EVM), and compared with baseline models including recurrent neural networks, long short-term memory networks, a single CNN, and a single Transformer. Experimental results demonstrate that AdaPhaseNet significantly outperforms existing methods in both compensation accuracy and system robustness.

The main contributions are summarized as follows:

A dual-branch adaptive phase noise compensation network named AdaPhaseNet is proposed and integrated into the digital signal processing chain at the receiver of a photonic terahertz OFDM system.

The impact of different input window sizes on phase noise estimation accuracy is evaluated, determining the optimal receptive field for the Transformer branch in AdaPhaseNet.

The impact of key parameters in AdaPhaseNet on system performance was analyzed, providing a basis for optimizing the network’s core components.

The proposed algorithm was experimentally validated. A comprehensive comparison between AdaPhaseNet and multiple baseline models was conducted in terms of BER and EVM performance, validating its superiority.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews related works on phase-noise compensation for OFDM systems.

Section 3 presents the proposed AdaPhaseNet and the methodology.

Section 4 describes the experimental setup.

Section 5 analyzes and optimizes the key parameters of AdaPhaseNet.

Section 6 discusses the experimental results.

Section 7 concludes the paper and outlines future research directions.

2. Related Works

As mentioned in

Section 1, phase noise compensation techniques for OFDM systems can generally be categorized into two types: conventional model-driven signal processing methods and data-driven learning-based approaches. Therefore, this section systematically reviews the research progress of both categories, analyzes their inherent limitations in depth, and, based on this discussion, further highlights the advantages of our proposed method for phase-noise compensation.

Traditional signal processing methods are built upon rigorous mathematical derivations. Their core idea is to utilize pilots or training sequences to estimate and compensate for the impact of phase noise [

6]. Among these, CPE compensation serves as a fundamental scheme, which estimates and corrects the common phase rotation across subcarriers. However, it completely ignores ICI, resulting in limited performance gains [

7]. To suppress ICI, more advanced schemes have been proposed. For instance, ICI cancellation algorithms based on frequency-domain comb-type pilots and the minimum mean square error (MMSE) criterion, or methods that model phase noise as time-varying parameters and employ Kalman filtering for tracking [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Although these traditional algorithms have clear structures and have been extensively studied, their inherent limitations become particularly prominent in terahertz communication scenarios [

12]. First, high-precision ICI compensation typically requires dense pilot patterns, which contradicts the core goal of pursuing extremely high spectral efficiency in terahertz communications. Second, the complex matrix operations involved lead to computational complexity that grows exponentially with the system bandwidth [

13], making them difficult to apply in broadband terahertz transmission scenarios [

14,

15].

To overcome the bottlenecks of traditional methods, data-driven approaches based on machine learning have emerged. These methods move away from the idea of explicitly modeling phase noise mathematically. Instead, they directly learn an end-to-end recovery mapping from the impaired signal to the ideal signal from large volumes of data [

16]. For example, deep neural network (DNN) have been employed to construct end-to-end receivers, implicitly performing joint channel equalization and phase noise suppression [

17]. Generative adversarial network (GAN) have been explored for generating training data or directly participating in the compensation process [

18]. Convolutional neural network (CNN) have been used to exploit the local correlations among subcarriers in the frequency domain to suppress ICI [

19]. Although these data-driven schemes demonstrate significant potential, they commonly suffer from a key drawback: difficulty in effectively capturing the inherent temporal dependencies of phase noise. It is important to note that phase noise is not white noise; its variation process exhibits significant memory or long-range correlation [

20]. This essential characteristic makes architectures like CNN, which primarily rely on local spatial feature extraction, less effective for achieving optimal compensation performance.

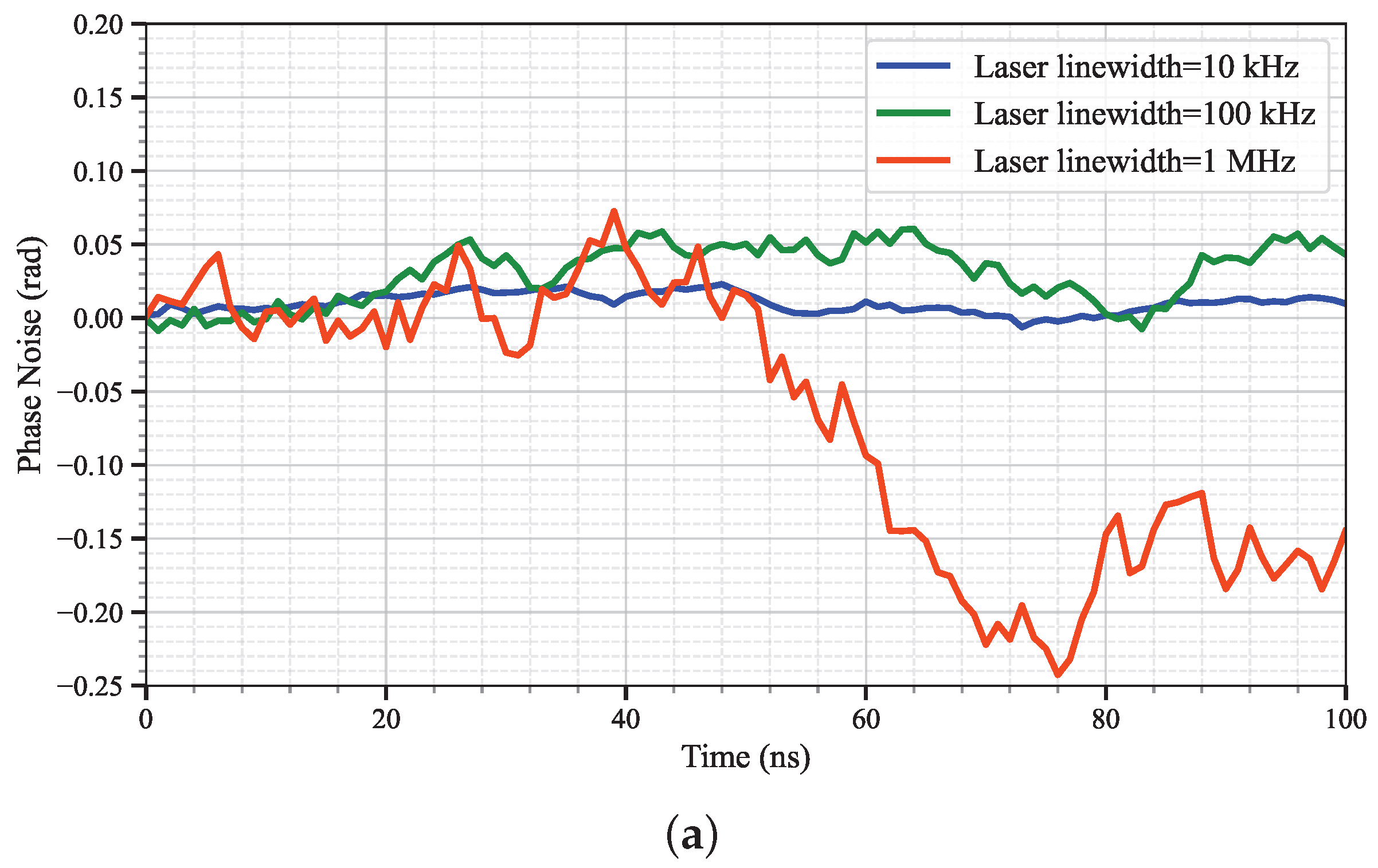

As shown in

Figure 1, we analyze the temporal characteristics of phase noise under different laser linewidth conditions through simulations.

Figure 1a illustrates the time-domain evolution of phase noise

. When the laser linewidth is

Hz, the fluctuation amplitude of phase noise is constrained within approximately

rad over short time scales, exhibiting a relatively smooth and slow-varying characteristic. As the linewidth increases to

Hz and

Hz, the fluctuation amplitude of phase noise intensifies significantly, exceeding

rad and

rad, respectively. Moreover, the time-domain waveform shows more high-frequency and severe random fluctuations, indicating that the dynamic variation rate of phase noise significantly increases with linewidth.

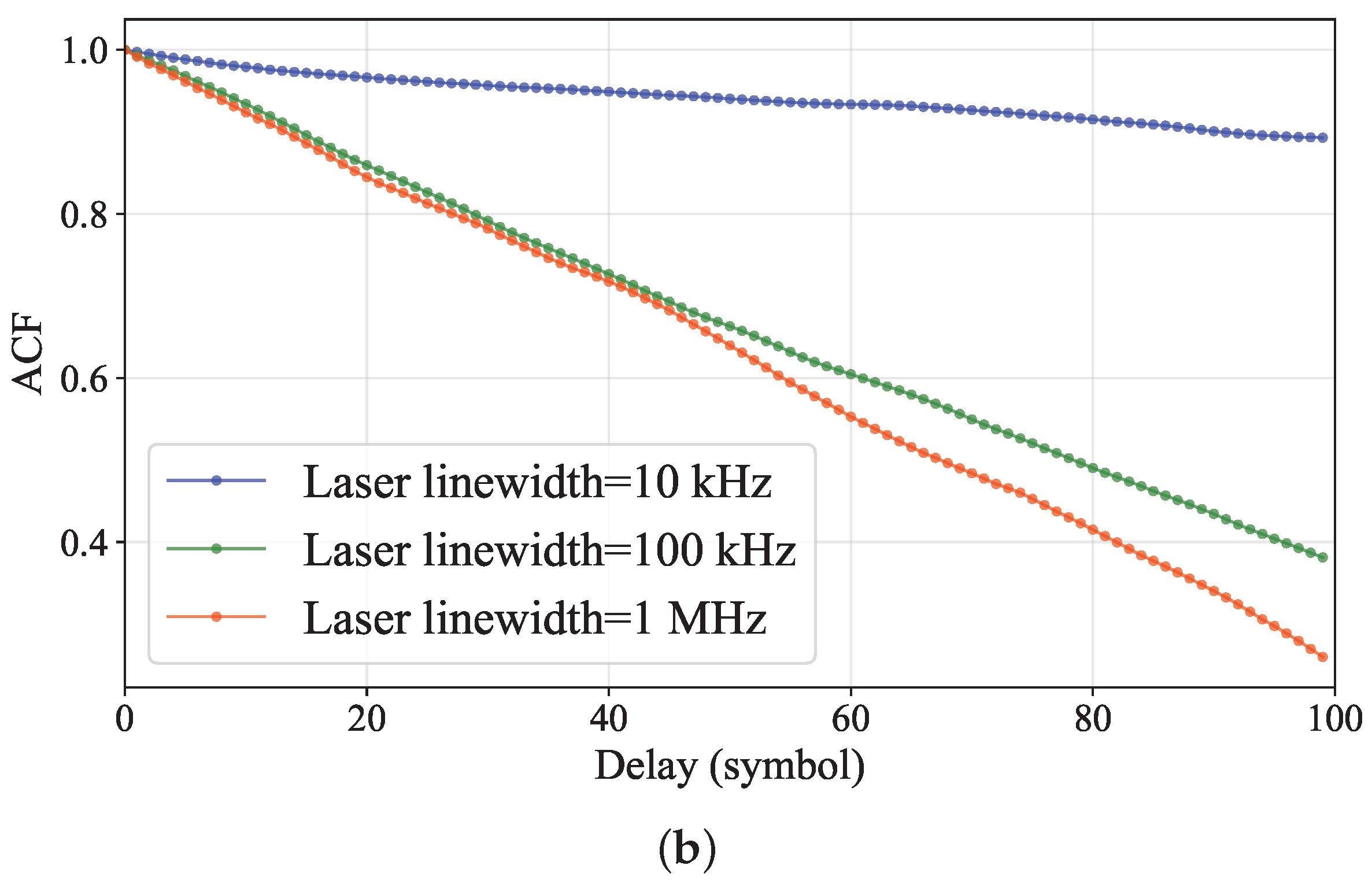

Figure 1b further reveals the temporal memory characteristics of phase noise through the autocorrelation function (ACF) curves. It can be observed that a smaller laser linewidth leads to a slower decay of the ACF, implying that the phase error at the current moment maintains a high correlation with historical values over a longer period, i.e., phase noise has a longer “memory length”. Conversely, when the linewidth increases, the ACF decay rate accelerates sharply, indicating that the temporal correlation of phase noise weakens rapidly, its randomness enhances, and the effective memory length shortens.

Based on the analysis above, phase noise, especially when the linewidth is small, constitutes a non-stationary process with significant long-range dependencies. This key observation provides important theoretical justification for employing the Transformer architecture in this work, owing to its effectiveness in capturing long-range temporal dependencies. Given the inherent temporal memory characteristics of phase noise, recurrent neural network (RNN) and their improved variants, such as long short-term memory (LSTM) networks, have been introduced into this field to explicitly model historical dependencies [

20]. Through their internal gated mechanisms, these networks aim to selectively remember and forget information, thereby theoretically enabling the capture of temporal dynamic features within sequences. However, RNN and LSTM often face challenges related to gradient vanishing or explosion during practical training. This essentially limits their effective memory span, making it difficult for them to stably learn long-term dependencies from distant history in long sequences.

In recent years, the Transformer architecture, based on the self-attention mechanism, has successfully overcome the limitations of RNN-based models in modeling long-range dependencies. Its core strength lies in its powerful capability for global sequence awareness—by computing the relevance weights between any positions in a sequence in parallel, it achieves dynamic and efficient integration of information across the entire sequence [

21]. This ability to directly capture long-range contextual dependencies is particularly crucial for accurately estimating signals with significant temporal correlation, such as phase noise, thus providing a more ideal modeling tool for such problems.

3. Methodology

In this section, we will explain AdaPhaseNet in detail, including its advantages, workflow and the core methods of its sub-modules.

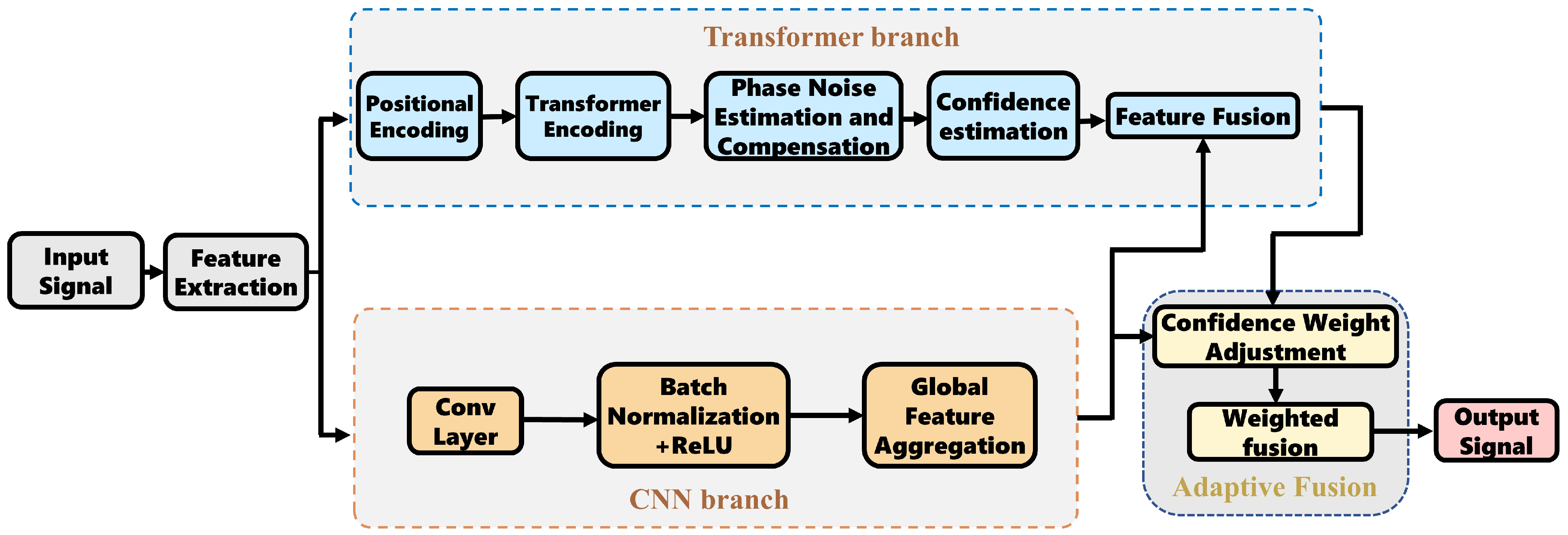

3.1. AdaPhaseNet

A single neural network architecture struggles to simultaneously accomplish the two critical tasks of “long-range phase tracking” and “local signal enhancement.” Specifically, while the Transformer excels at modeling the temporal dependencies of phase noise, it exhibits limitations in directly handling composite impairments such as additive noise and nonlinear distortion. Conversely, the CNN is proficient in local feature extraction and signal enhancement, but its inherently limited receptive field prevents it from effectively compensating for phase noise with long memory.

Building on this complementary nature, this paper innovatively proposes a novel dual-branch adaptive compensation network named AdaPhaseNet, the overall structure of which is shown in

Figure 2. This architecture aims to integrate the strengths of the Transformer and the CNN, achieving an intelligent balance between the strategies of “accurate phase rotation correction” and “signal enhancement” through an adaptive fusion mechanism.

The workflow of this architecture comprises three core steps:

Feature Extraction and Branch Input: The received noisy baseband signal undergoes preprocessing and is converted into two distinct feature representations. One path is used to generate a phase difference sequence, serving as the input to the Transformer branch to focus on the temporal characteristics of the phase noise. The other path retains the original I/Q waveform signals, which are fed into the CNN branch for local feature learning.

Specialized Subnetwork Processing: The two branches process the features in parallel. Leveraging its global self-attention mechanism, the Transformer branch accurately estimates the long-range correlated phase noise while simultaneously outputting a confidence score for its estimate. The CNN branch, through its hierarchical convolutional structure, performs blind enhancement on the original signal to effectively suppress non-phase impairments such as additive noise and inter-symbol interference.

Adaptive Fusion Output: The preliminary outputs from the two branches are combined in an adaptive fusion module. This module dynamically adjusts the contribution weight of each branch in the final output based on the real-time confidence provided by the Transformer branch, followed by a weighted fusion to generate the purified signal. This mechanism ensures the system maintains optimal compensation performance under various channel conditions.

3.2. Transformer

Transformer is a deep learning architecture based on self-attention. Its core lies in efficiently modeling global dependencies by computing correlation weights between any two elements in a sequence in parallel. This mechanism dynamically assigns attention weights to each position in the sequence by computing interactions between query (Q), key (K) and value (V) vectors. For a received symbol sequence of length L,

, the attention output Z is computed as follows:

where

,

,

are obtained by linear projection of the input sequence,

is the dimension of the key vector, and the scaling factor

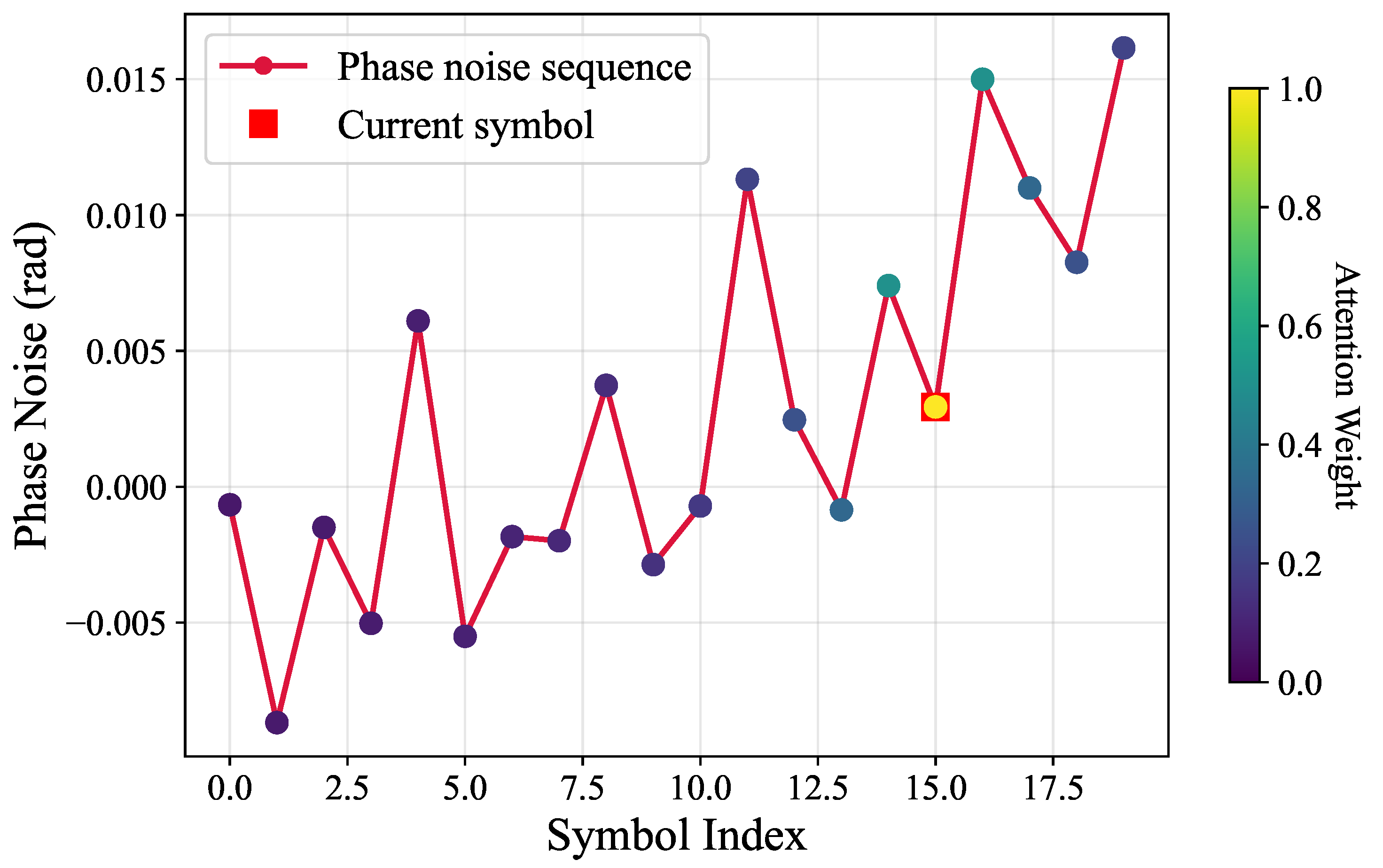

is used to stabilize gradients. The softmax function normalizes the attention weights, enabling adaptive weighted aggregation of historical information. Due to its parallel computing characteristics, Transformer can directly capture interactions between any long-distance positions in the sequence, significantly improving the modeling capability of long-range dependencies. Although this architecture originated in the field of natural language processing, its powerful sequence modeling capability has rapidly extended to time-series data tasks such as computer vision, speech recognition, and communication signal processing. Phase noise estimation and compensation is essentially a typical time-series modeling problem, and the self-attention mechanism of Transformer provides an ideal tool for accurately characterizing the temporal dependencies of phase noise. As shown in

Figure 3, the self-attention mechanism allows the current symbol to attend to all contextual information (both historical and future symbols) in the entire input sequence, where the color of the dots is light blue.

In this paper, we introduce the Transformer architecture into the phase noise estimation and compensation task in photonic terahertz OFDM systems. To satisfy the causality constraint of communication systems, a causal mask is used during both training and inference, ensuring that the estimation at time

t depends only on historical information (from time 1 to time

), preventing any leakage of future information. Specifically, for an input sequence of length

L, a causal mask matrix

is defined as:

where index

i denotes the position of the Query (

) and index

j denotes the position of the Key (

). In the self-attention computation, this causal mask is added to the original attention score matrix. The modified attention score matrix

is calculated as:

Finally, the attention weights

are obtained through the Softmax function:

Leveraging Transformer’s ability to capture long-range dependencies, we construct a phase noise estimator. This estimator takes a feature sequence composed of the instantaneous phase differences of the received signal as input, extracts deep temporal features through a multi-layer Transformer encoder, and finally outputs both the estimated phase noise and its confidence. Compared to traditional algorithms that rely on preset models or local stationarity assumptions, this data-driven method can directly learn the complex statistical characteristics and evolution patterns of phase noise from data, making it particularly suitable for handling high-intensity, non-stationary phase noise scenarios. This provides a new solution for enhancing the reliability of high-speed terahertz communication systems.

3.3. CNN

Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) is a type of deep learning architecture specifically designed to process data with a grid-like topology (such as images or time-series signals) that possesses the characteristics of local correlation and translation invariance. In this study, the CNN is constructed as a signal enhancement branch operating in parallel with the phase noise estimation branch. Its primary objective is to perform blind enhancement and purification of mixed impairments present in the received signal, excluding phase noise—such as additive noise, residual channel distortion, and nonlinear distortion. This branch takes the I/Q components of the original noisy signal as input. Through stacked one-dimensional convolutional layers, it automatically extracts the local structural features of the signal, thereby learning a nonlinear mapping function from the impaired signal to an enhanced signal.

The design core of this CNN branch lies in its hierarchical feature extraction and fusion mechanism. The network is composed of multiple stacked convolutional modules, with each module typically containing a one-dimensional convolutional layer, a batch normalization layer, and a ReLU activation function. The shallow convolutional kernels are responsible for capturing local, fine-grained features such as amplitude distortion and impulse noise. As the network depth increases, the receptive field progressively expands, allowing deeper layers to identify medium- to long-range waveform distortion patterns. Ultimately, the network reconstructs the enhanced signal through global feature aggregation. The entire processing flow does not rely on any explicit channel or noise models. It is entirely data-driven, thus enabling adaptive suppression of various unknown mixed impairments and improving the overall signal quality.

3.4. Adaptive Fusion Module

To intelligently integrate the outputs of the dual branches, we design an adaptive fusion module. This module takes the results from the front-end parallel processing as its input. The Transformer branch provides the signal along with its corresponding confidence score x. is the signal obtained after preliminary phase noise compensation and subsequent feature fusion with the CNN branch. Concurrently, the CNN branch provides the signal , which is the result after processing composite impairments. Subsequently, the fusion weight is dynamically calculated based on the confidence score x, and a weighted fusion of the two signals is performed to generate the final purified output signal .

The calculation mechanism for the confidence-based weight

is defined as follows. A threshold is set at

. When the confidence is high (

), it indicates that the phase noise estimation is relatively reliable. In this case, the fusion weight leans towards the Transformer branch. Conversely, when the confidence is low (

), greater reliance is placed on the robust signal enhancement result provided by the CNN branch. The weight

is calculated as follows:

Finally, the output signal

is generated by the following formula:

This design enables the system to smoothly and adaptively switch between the two strategies of “high-precision phase tracking” and “robust signal enhancement”, thereby maintaining excellent overall performance under various channel conditions.

4. Experimental Setup

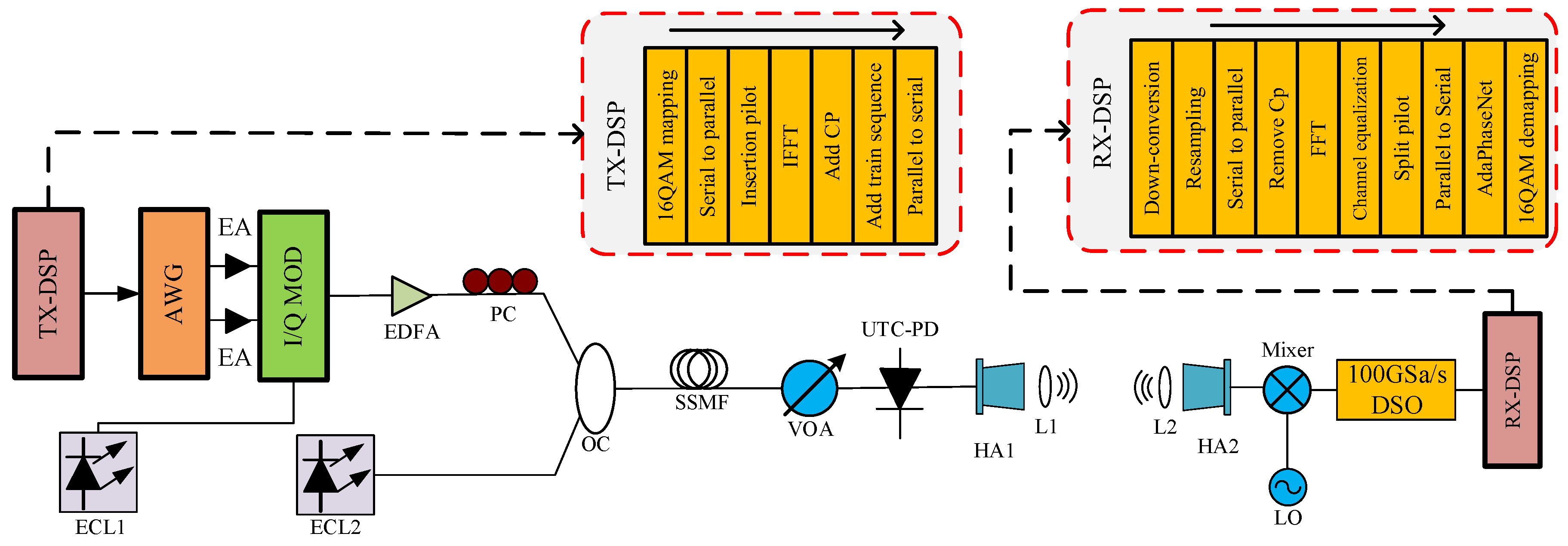

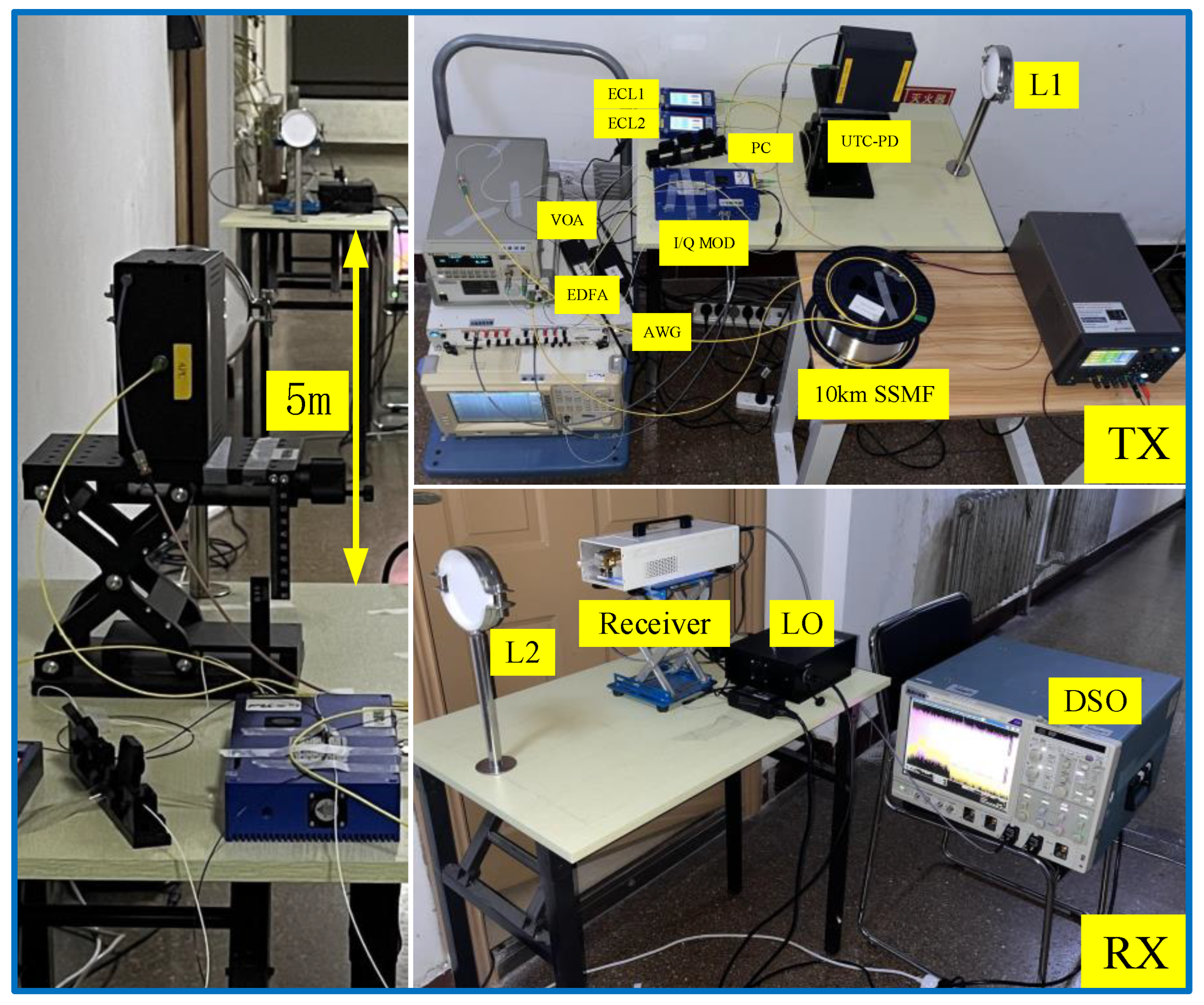

For algorithm validation, we constructed an experimental platform for a photonic terahertz communication system. The link diagram is shown in

Figure 4, and the equipment used in the experiment is presented in

Figure 5. At the transmitter, test data generated by a PRBS generator is modulated using 16QAM and 128-point IFFT-based OFDM. The experimental link operates at a bit rate of 4 Gbps. The modulated symbols are processed by a DAC with 12× oversampling to produce the baseband signal. Lasers ECL1 and ECL2 emit continuous waves CW1 and CW2 at wavelengths of 1550 nm and 1547.44 nm, respectively. The baseband signal from an arbitrary waveform generator (AWG) is amplified by an electrical amplifier (EA) and then impressed onto CW1 via an I/Q modulator. The modulated optical signal is further amplified by an erbium-doped fiber amplifier (EDFA), and its polarization is adjusted by a polarization controller (PC) before being combined with CW2 in an optical coupler (OC). The coupled signal travels through 10 km of standard single-mode fiber (SSMF) and enters a variable optical attenuator (VOA) to adjust the optical power to a level suitable for the uni-traveling-carrier photodiode (UTC-PD). The attenuated signal is fed into the UTC-PD to generate the photonic terahertz signal via heterodyne beating. This signal is radiated by the HA1, propagates over 5 m of free space to the receiver, and is focused using lenses (L1 and L2) to mitigate free-space loss.Notably, to focus on validating the effectiveness of the proposed algorithm and to reduce the difficulty of reproduction, we intentionally do not employ a terahertz power amplifier in the experimental setup.

At the receiver, the terahertz signal captured by antenna HA2 is mixed with a 327 GHz sinusoidal wave from a local oscillator (LO), down-converted to a 7 GHz intermediate frequency (IF) signal, and digitized by a digital oscilloscope (DSO) operating at 100 GSa/s. Finally, the captured signal undergoes the RX-DSP steps, including down-conversion, resampling, OFDM demodulation, and AdaPhaseNet-based processing, to recover the original data. AdaPhaseNet is placed after parallel to serial conversion and before symbol demapping, where the CPE/ICI induced by phase noise and residual local distortions are most prominent. This deployment enables the network to directly compensate for phase noise and mitigate residual local distortions after OFDM demodulation, and output high-quality signals. Without AdaPhaseNet, the receiver has to rely on the conventional DSP chain and perform symbol demapping directly after OFDM demodulation, which results in an increase in residual phase errors and degradation of the system performance under the scenario of strong phase noise.

5. AdaPhaseNet Key Parameter Analysis and Optimization

In AdaPhaseNet, the hyperparameters of the algorithmic modules and the network architecture jointly determine the theoretical performance ceiling and the practical learning efficiency of the system. Specifically, within the design of the adaptive fusion module, the choice of the threshold parameter has a decisive impact on system performance. In the Transformer-based phase noise estimator, the window size determines the temporal receptive field and the amount of physical information available to the network, which directly influences the theoretical upper bound of estimation accuracy. Meanwhile, hyperparameters such as batch size, network depth, and number of attention heads collectively govern the model’s ability to effectively learn features.Therefore, in this chapter, we first analyze the influence of different threshold settings on the system’s BER performance to select the optimal threshold. Subsequently, we examine the impact of window size on estimation performance to determine the optimal input dimension. Finally, we conduct systematic ablation experiments on the network architecture hyperparameters to optimize the network’s convergence and stability.

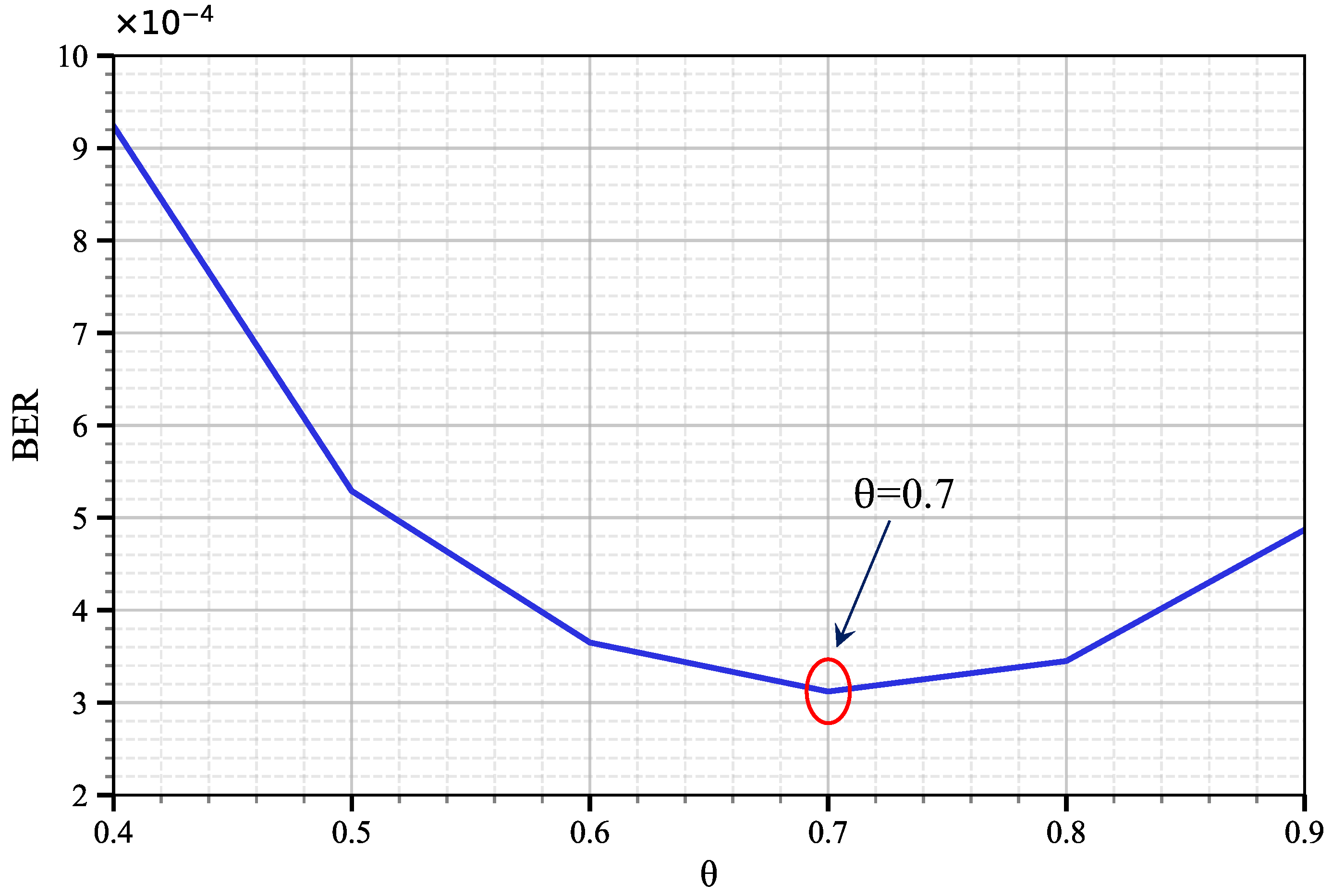

5.1. Adaptive Fusion Threshold Optimization and Performance Analysis

To determine the optimal threshold, we examined the variation in the system’s BER as

ranged from

to

. The results are shown in

Figure 6.

The BER curve exhibits a distinct “U-shaped” trend, revealing the trade-off mechanism inherent in threshold configuration. When the threshold is set too low (), AdaPhaseNet activates the phase correction branch too frequently. However, in scenarios where channel conditions are acceptable and phase noise is not the dominant impairment, forced phase correction may introduce unnecessary estimation errors or amplify the residual additive noise from the CNN branch, leading to an increase in BER.As increases, phase correction becomes more conservative, avoiding overcorrection under favorable channel conditions. Consequently, the BER decreases rapidly. At , AdaPhaseNet achieves the best decision balance, reaching the global minimum BER. At this setting, the system can accurately determine when to rely on the Transformer branch for precise phase rotation and when to depend on the CNN branch for signal enhancement.When is further increased to , AdaPhaseNet tends to conservatively maintain the CNN-enhanced signal. However, in the presence of significant phase noise, it fails to fully leverage the correction capability of the Transformer, resulting in a slow rebound in BER.

The above analysis demonstrates that is the optimal threshold for the system under the tested conditions. This setting ensures that the adaptive fusion module can make nearly optimal fusion decisions in complex and varying impairment environments.

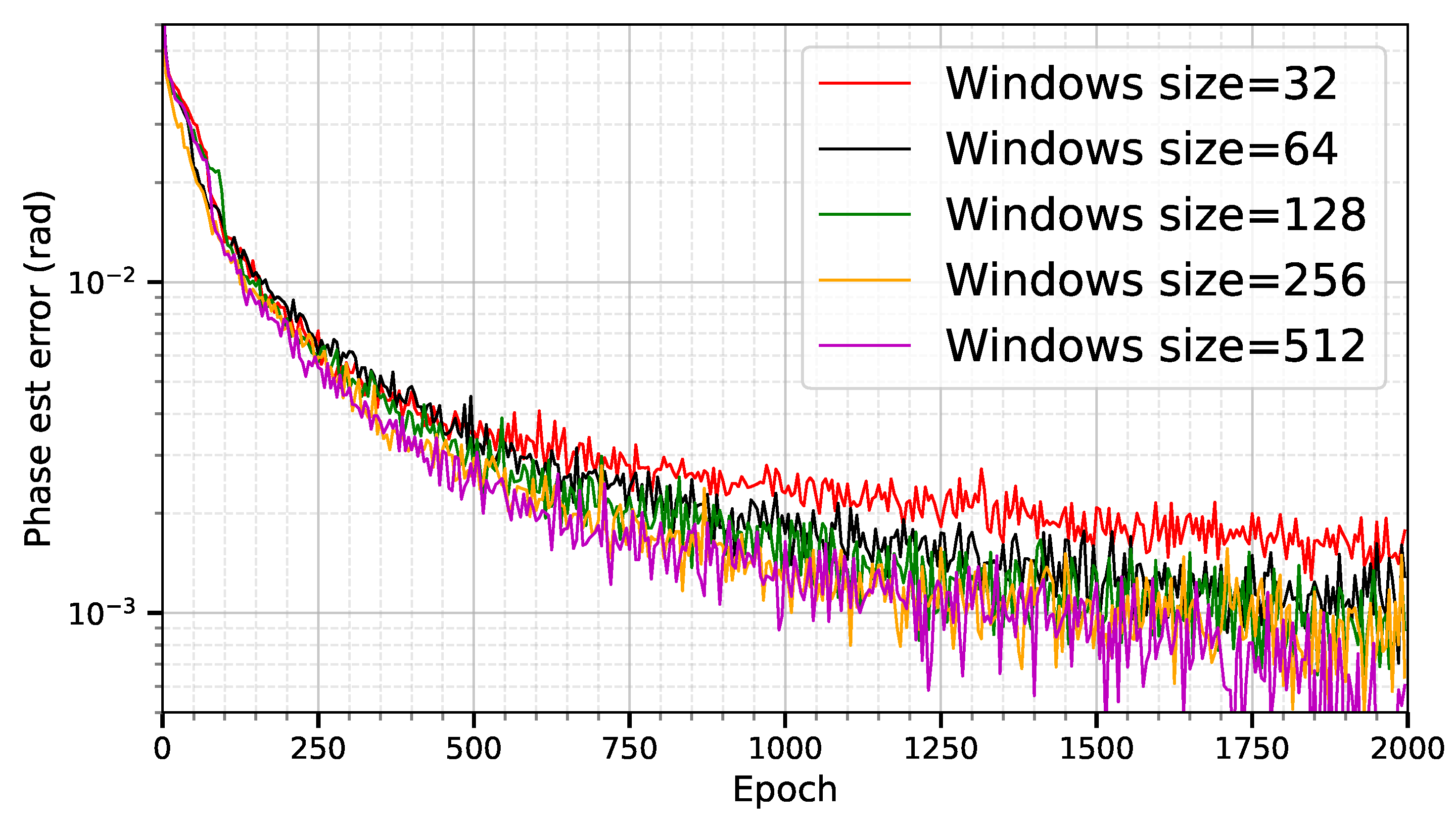

5.2. Impact of Window Size on Estimation Performance

As shown in

Figure 7, we examine the variation of phase noise estimation error with training epochs under different window sizes. The results indicate that the configuration with a window size of 32 exhibits the slowest convergence speed and the highest steady-state error, suggesting that a limited temporal receptive field severely constrains the Transformer model’s ability to capture the long-term correlation characteristics of phase noise. As the window size increases from 32 to 128, the model performance improves significantly: the error curve descends faster and eventually stabilizes at a lower level, verifying that expanding the temporal context window helps the self-attention mechanism identify noise features more effectively. When the window size is further increased to 256 and 512, the model achieves lower initial error early in training and maintains a stable decreasing trend throughout the training process, ultimately reaching the lowest steady-state error. This phenomenon indicates that a sufficiently large window size is a necessary condition for the model to fully learn the long-memory characteristics of phase noise and achieve high-precision, robust estimation.

It is worth noting that although the window size of 512 achieves the best accuracy performance, its corresponding computational and memory costs increase linearly with the window size. Balancing estimation accuracy, training stability, and computational efficiency, we ultimately select a window size of 256 for all subsequent experiments, aiming to maintain high accuracy while controlling model complexity.

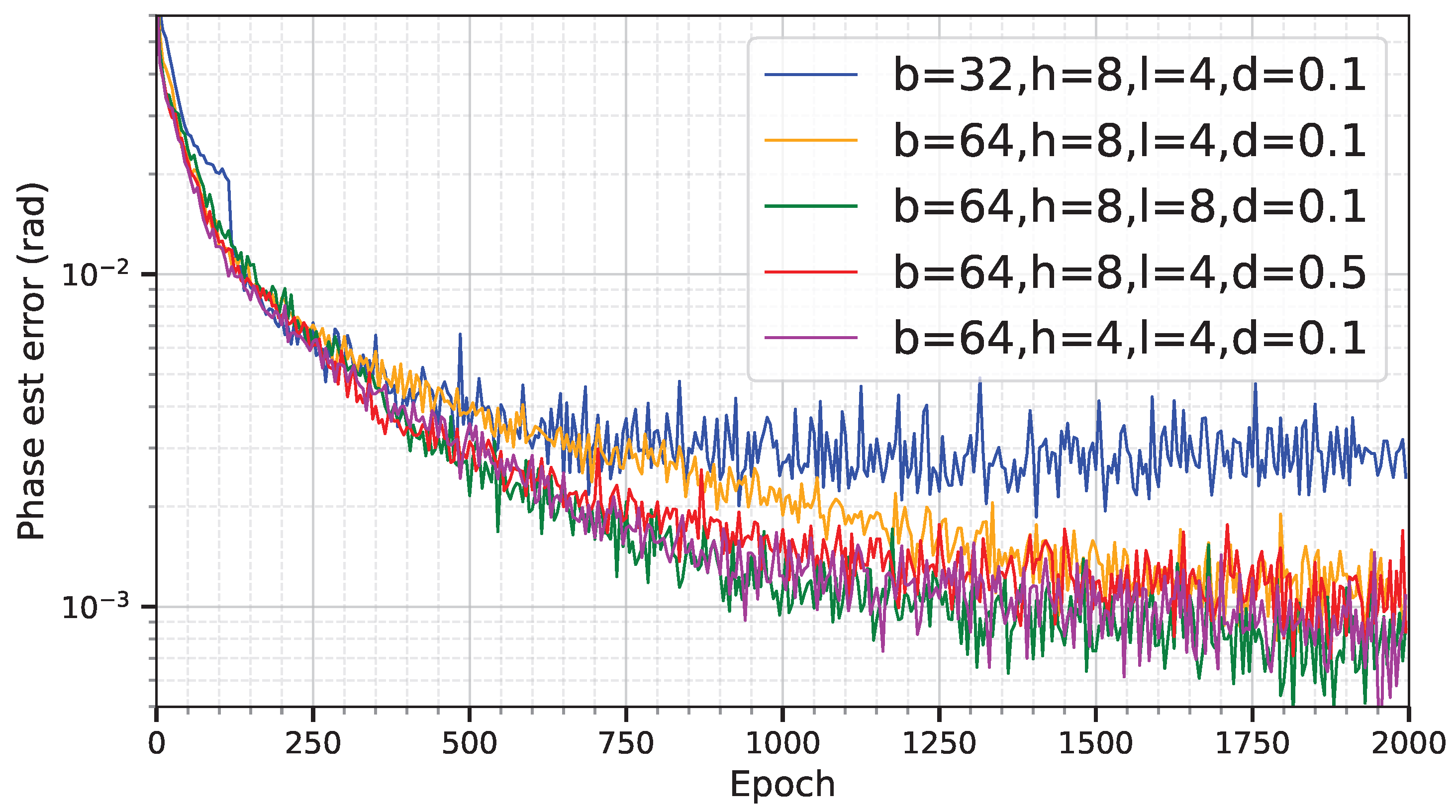

5.3. Ablation Study and Optimization of Transformer Architecture Hyperparameters

Figure 8 presents the sensitivity analysis results of the Transformer network to key architectural hyperparameters. We systematically conduct ablation studies on critical hyperparameters including batch size (

b), number of attention heads (

h), network layers (

l), and dropout rate (

d). The experimental results indicate that the stability of the training process significantly depends on the choice of batch size. Specifically, when

, the training exhibits noticeable high-variance oscillations, suggesting considerable noise in gradient estimation, which hinders effective convergence of the optimizer. In contrast, increasing the batch size to 64 results in a smoother and more stable convergence trajectory, demonstrating superior training characteristics.

Regarding regularization, the setting of the dropout rate has a significant impact on the model fitting performance. The results show that a relatively high dropout rate of is overly aggressive for the current regression task, leading to underfitting, as evidenced by its residual error being markedly higher than that of the configuration with . Furthermore, model capacity plays a crucial role in estimation accuracy: increasing the network depth from 4 to 8 layers enables the model to better learn the complex nonlinear features within the phase noise, consequently achieving the lowest validation loss among all tested configurations.

Based on the aforementioned analysis, this work ultimately selects , , , and as the optimal hyperparameter configuration for the Transformer-based phase noise estimator. This combination achieves the best balance between convergence stability and estimation accuracy.

6. Results and Discussion

After confirming the optimal parameter configuration (, , , , , ), we conducted a systematic evaluation of the BER and EVM performance of the proposed AdaPhaseNet network against multiple baseline models. EVM is a key metric for measuring the deviation between the received signal and the ideal reference signal, directly reflecting the recovery fidelity in the signal transmission and processing chain. Its computational procedure is as follows:

First, the EVM value in the linear domain (percentage form) is computed using the core formula:

where

denotes the complex amplitude of the

i-th symbol actually detected at the receiver (including amplitude and phase information),

represents the complex amplitude of the ideal reference symbol at the transmitter, and

N is the total number of OFDM symbols counted. To convert the linear-domain EVM to the dB form (the standard representation in the communication field), the formula is:

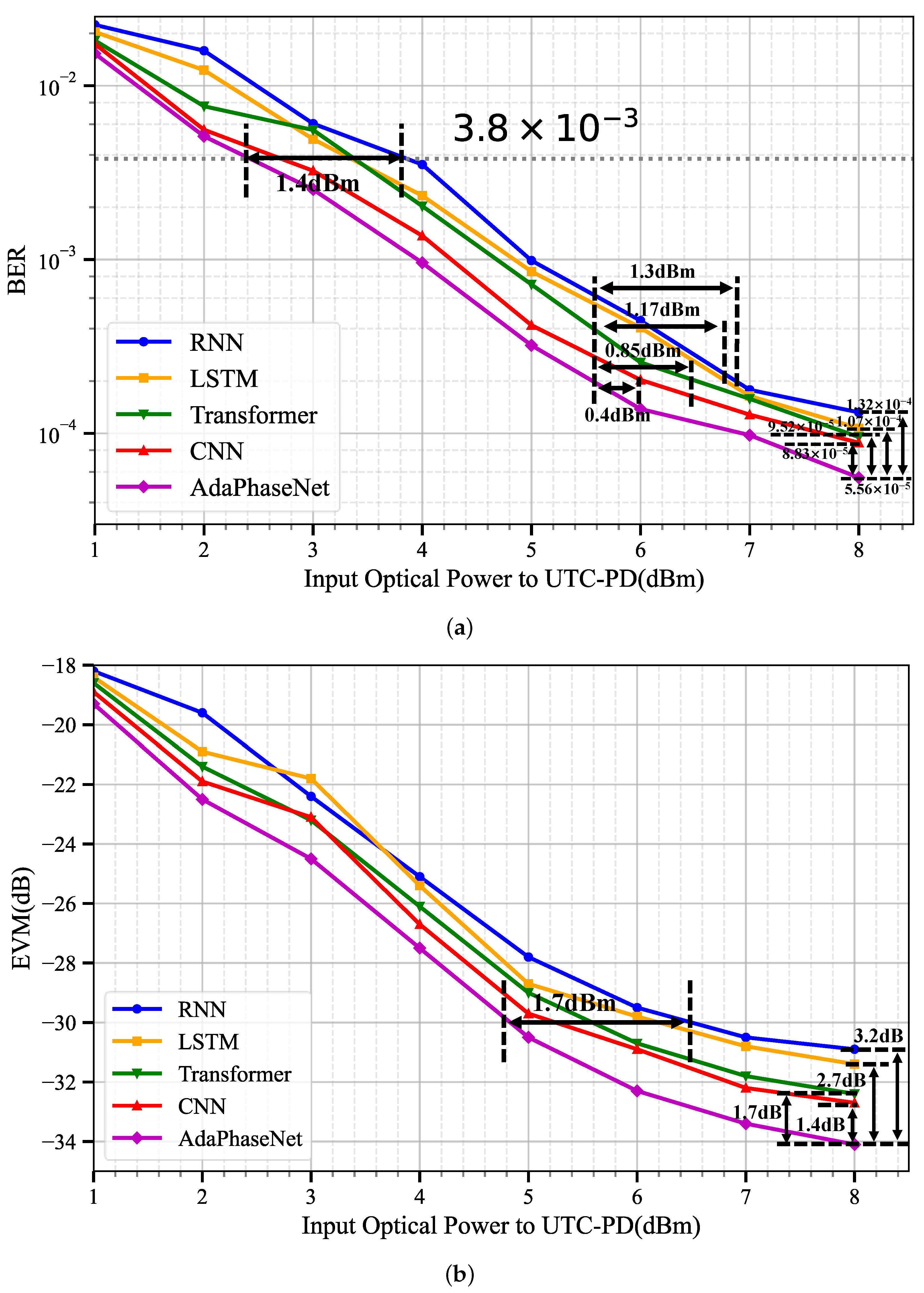

The comparative results are shown in

Figure 9. First, in the region of low input optical power to UTC-PD(denoted as

), e.g., 1–4 dBm, where channel conditions are relatively harsh and signal impairments are dominated by a combination of additive noise and phase noise, the strength of AdaPhaseNet lies in its adaptive fusion module. This module intelligently balances the outputs of the two branches. The CNN branch, leveraging its robust local feature extraction and filtering capabilities, effectively suppresses background noise, providing a reliable baseband signal for fusion. Concurrently, the Transformer branch focuses on tracking the trend of phase variation from the noise-corrupted signal. In this region, the bit error rate (BER) and error EVM performance of AdaPhaseNet is significantly and consistently superior to all baseline models. At a BER of

, AdaPhaseNet achieves a maximum

gain of approximately 1.4 dB compared to other baselines. In contrast, standalone RNN or LSTM models struggle to maintain stable long-range modeling capability under strong noise due to their inherent sequential processing defects and gradient issues. While the standalone Transformer model possesses stronger modeling capability, its ability to filter out local impairments like impulsive noise is inferior to that of CNN. The standalone CNN model, however, completely fails to handle long-range phase noise, exhibiting a clear performance bottleneck.

Second, in the high

region (e.g., 5–8 dBm), where signal quality improves and the impact of additive noise diminishes, phase noise gradually becomes the dominant factor limiting system performance. The performance advantage of AdaPhaseNet further expands. At a BER of

, AdaPhaseNet achieves

gains of 1.3 dB, 1.17 dB, 0.85 dB, and 0.4 dB compared to four baselines (RNN, LSTM, Transformer, and CNN), respectively. When the

is 8 dBm, the BER of these baselines and AdaPhaseNet are

,

,

,

and

, respectively, corresponding to relative BER reductions of 57.9%, 48.0%, 41.6%, and 37.0%. Furthermore,

Figure 9b shows that at an EVM of approximately −33 dB, AdaPhaseNet achieves EVM gains of 3.2 dB, 2.7 dB, 1.7 dB, and 1.4 dB over the same baselines mentioned above, respectively.

The above results strongly demonstrate:

The designed Transformer branch possesses excellent sequential modeling capability for phase noise. Its causal masking and long-window design enable it to accurately estimate and compensate for phase perturbations with memory.

The effectiveness of the adaptive fusion module. It correctly places high confidence in the Transformer branch’s high-precision phase estimation results and “calibrates” the enhanced signal from the CNN branch, thereby outputting a signal with purer phase. In contrast, other baseline models, due to either architectural limitations or a singular optimization objective, fail to simultaneously achieve local signal purification and global phase tracking, thus reaching their performance limits in the high region.

Notably, although AdaPhaseNet achieves significant BER/EVM improvements over all baseline models across the entire power range, the BER observed in our experiment still remains on the order of to . We attribute this primarily to the hardware noise floor limitation of the experimental link. Specifically, some receiver-side instruments used in our setup (e.g., the oscilloscope and the mixer) are relatively old, and thus exhibit higher inherent noise and a higher effective noise figure. As a result, more pronounced noise and distortion are introduced during the down-conversion and sampling stages, which elevates the BER “floor”. Under such noise-limited conditions, the benefit of the proposed algorithm is reflected more in a stable gain relative to the baseline schemes (i.e., a clear BER reduction and EVM improvement under the same hardware platform and link conditions).

7. Conclusions

This paper addresses the severe phase noise challenge in photonic terahertz OFDM systems by proposing a dual-branch adaptive noise compensation network named AdaPhaseNet. Through a functionally specialized design, this architecture enables the Transformer branch to focus on capturing the long-range temporal dependencies of phase noise, while simultaneously employing the CNN branch to suppress local impairments such as additive noise. The core adaptive fusion mechanism dynamically integrates the outputs of the two branches based on confidence scores, achieving an intelligent balance between the strategies of “precise phase tracking” and “robust signal enhancement.” Although the model training process requires a certain amount of time, once trained, the network can process received signals in real-time, meeting the low-latency requirements of practical communication systems.

Experimental results validate the superiority of the proposed network. In terms of BER, AdaPhaseNet achieves optimal performance under all tested conditions, demonstrating significant gains, especially in the low BER region. Moreover, it consistently outperforms all baseline models on the EVM metric, proving its effectiveness in enhancing signal modulation quality.

Future work will focus on the following directions: first, investigating model lightweighting techniques to reduce computational and memory overhead, making it suitable for resource-constrained terminal devices; second, exploring joint optimization of the model for end-to-end systems; third, investigating the generalizability of this architecture to other frequency bands.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.C. and J.Y.; Data curation, J.Y.; Formal analysis, S.C.; Funding acquisition, J.Y.; Investigation, S.C. and T.L.; Methodology, S.C.; Project administration, J.Y.; Resources, J.Y.; Software, S.C.; Supervision, J.Y.; Validation, S.C. and L.Z.; Visualization, S.C. and L.Z.; Writing—original draft, S.C.; Writing—review & editing, J.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NO.62127802, NSFC).

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting reported results can be found from the author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rappaport, T.S.; Xing, Y.; Kanhere, O.; Ju, S.; Madanayake, A.; Mandal, S.; Alkhateeb, A.; Trichopoulos, G.C. Wireless Communications and Applications Above 100 GHz: Opportunities and Challenges for 6G and Beyond. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 78729–78757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarieddeen, H.; Alouini, M.S.; Al-Naffouri, T.Y. An Overview of Signal Processing Techniques for Terahertz Communications. Proc. IEEE 2021, 109, 1628–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollet, T.; Van Bladel, M.; Moeneclaey, M. BER sensitivity of OFDM systems to carrier frequency offset and Wiener phase noise. IEEE Trans. Commun. 1995, 43, 191–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morelli, M.; Mengali, U. A comparison of pilot-aided channel estimation methods for OFDM systems. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2001, 49, 3065–3073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.J.; Chi, N. Optical Fiber Communication Technology Based on Digital Signal Processing: Volume 2, Multi-Carrier Signal Transmission and New Algorithms such as Neural Networks; Tsinghua University Press: Beijing, China, 2020; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Schenk, T. RF Imperfections in High-Rate Wireless Systems; RF Imperfections in High-Rate Wireless Systems; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, J. Analysis of new and existing methods of reducing intercarrier interference due to carrier frequency offset in OFDM. IEEE Trans. Commun. 1999, 47, 365–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Bar-Ness, Y. OFDM systems in the presence of phase noise: Consequences and solutions. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2004, 52, 1988–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Bar-Ness, Y. A phase noise suppression algorithm for OFDM-based WLANs. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2002, 6, 535–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovic, D.; Rave, W.; Fettweis, G. Effects of Phase Noise on OFDM Systems With and Without PLL: Characterization and Compensation. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2007, 55, 1607–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehata, T.S.; El-Tanany, M. Joint iterative detection and phase noise estimation algorithms using Kalman filtering. In Proceedings of the 2009 11th Canadian Workshop on Information Theory, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 13–15 May 2009; pp. 165–168. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Shlezinger, N.; Guidi, F.; Dardari, D.; Eldar, Y.C. 6G Wireless Communications: From Far-Field Beam Steering to Near-Field Beam Focusing. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2023, 61, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavendra, M.; Giridhar, K. Improving channel estimation in OFDM systems for sparse multipath channels. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2005, 12, 52–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jornet, J.M.; Akyildiz, I.F. Channel Modeling and Capacity Analysis for Electromagnetic Wireless Nanonetworks in the Terahertz Band. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2011, 10, 3211–3221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.X.; Wang, J.; Hu, S.; Jiang, Z.H.; Tao, J.; Yan, F. Key Technologies in 6G Terahertz Wireless Communication Systems: A Survey. IEEE Veh. Technol. Mag. 2021, 16, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shea, T.; Hoydis, J. An Introduction to Deep Learning for the Physical Layer. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Commun. Netw. 2017, 3, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Li, G.Y.; Juang, B.H. Power of Deep Learning for Channel Estimation and Signal Detection in OFDM Systems. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 2018, 7, 114–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Li, G.Y.; Juang, B.H.F.; Sivanesan, K. Channel Agnostic End-to-End Learning Based Communication Systems with Conditional GAN. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Globecom Workshops (GC Wkshps), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 9–13 December 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Chen, X.; Qian, L.; Du, X.; Yu, C.; Kam, P.Y. Pilot-Aided Deep Learning Based Phase Estimation for OFDM Systems with Wiener Phase Noise. In Proceedings of the 2023 Asia Communications and Photonics Conference/2023 International Photonics and Optoelectronics Meetings (ACP/POEM), Wuhan, China, 4–7 November 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Li, Y.; Wu, G. DPD and Compensation under RF Impairments in the Hardware by BiLSTM. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 22nd International Conference on Communication Technology (ICCT), Virtual, 11–14 November 2022; pp. 1472–1476. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1706.03762. [Google Scholar]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |