AI-Based Indoor Localization Using Virtual Anchors in Combination with Wake-Up Receiver Nodes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Works

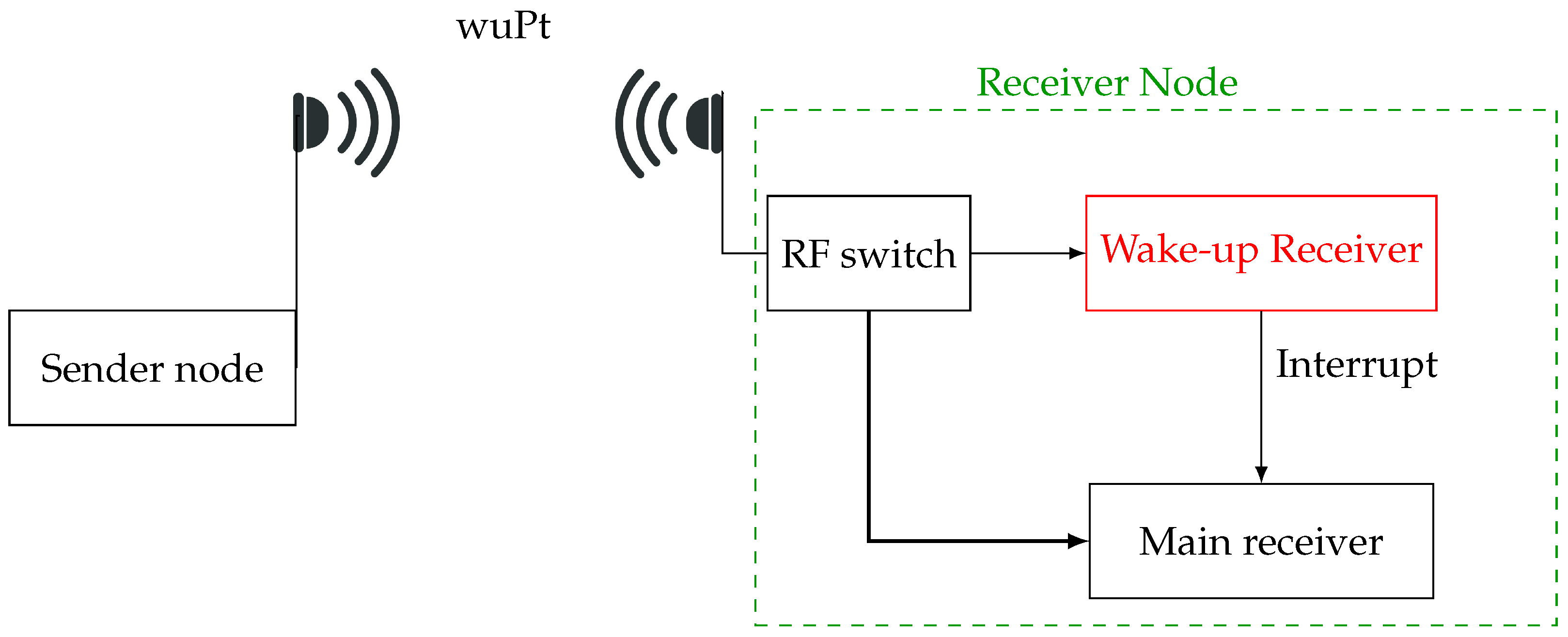

3. Hardware System Setup: Wake-Up Receiver Node

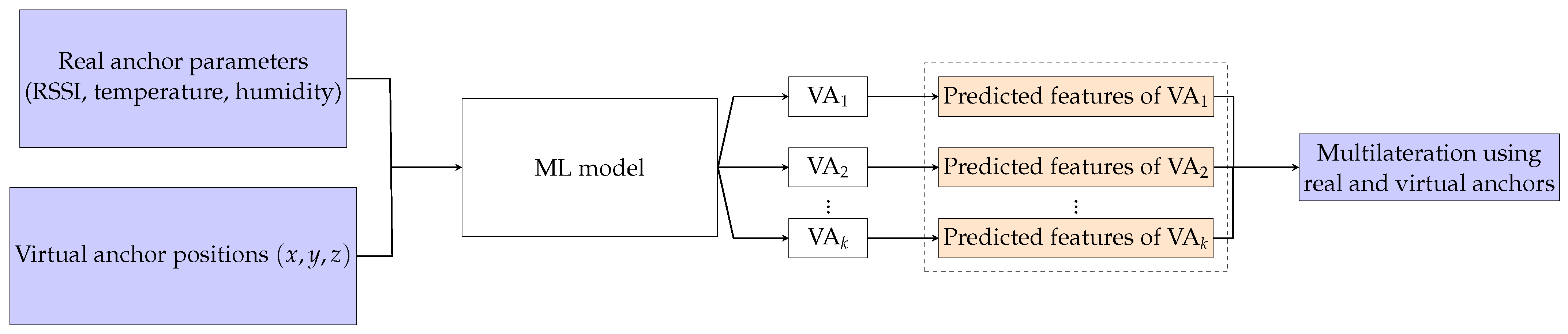

4. System Architecture and Theoretical Background

4.1. Received Signal Strength Indicator (RSSI)

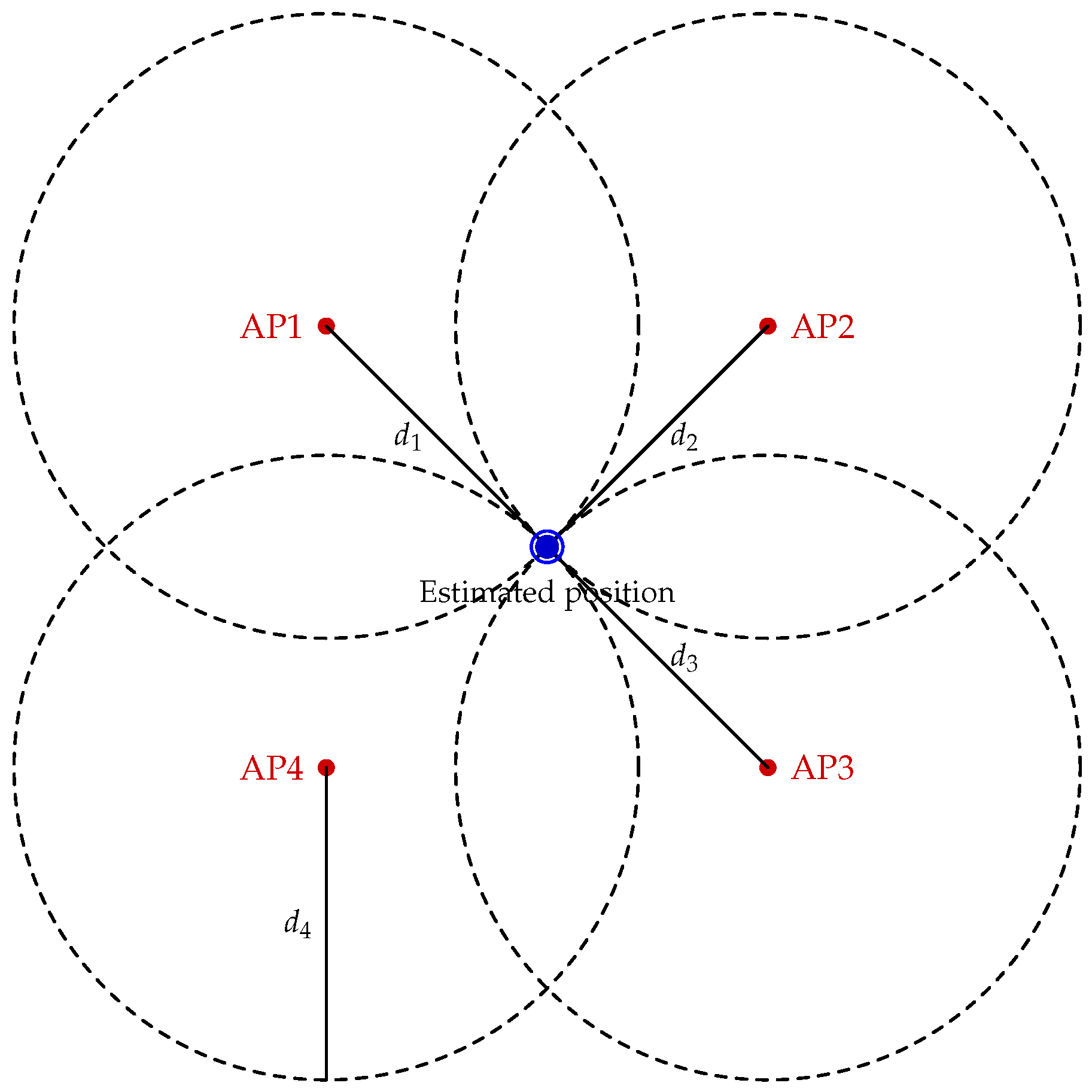

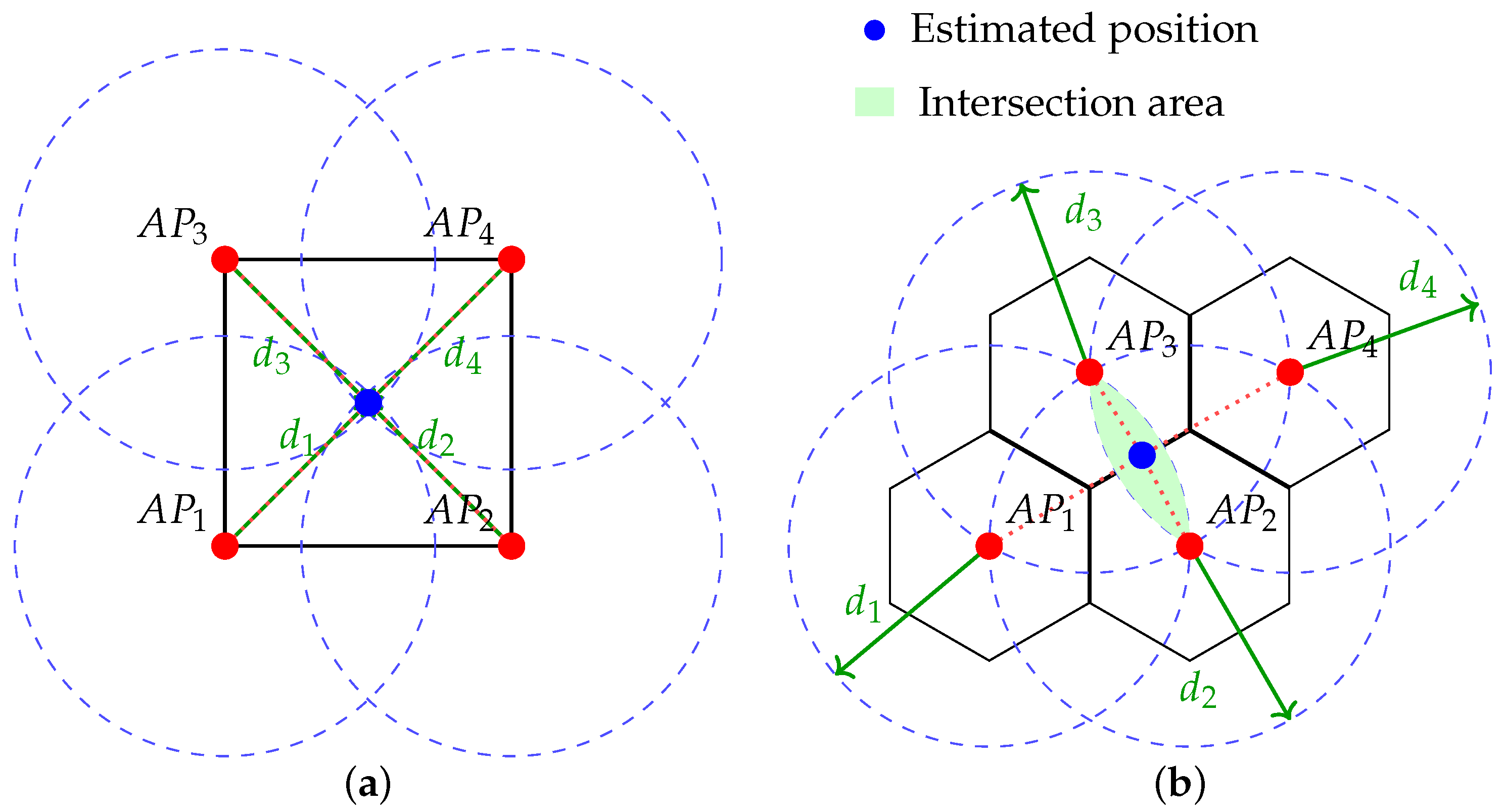

4.2. Multilateration

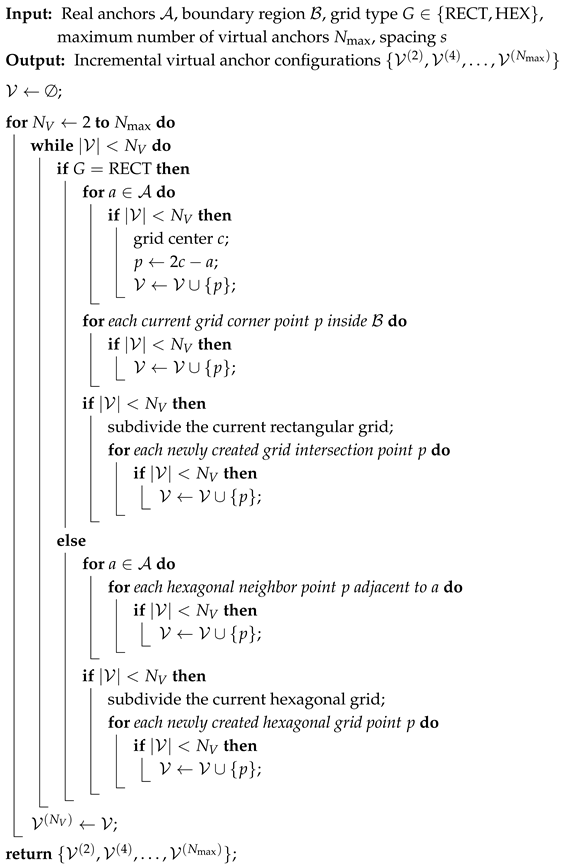

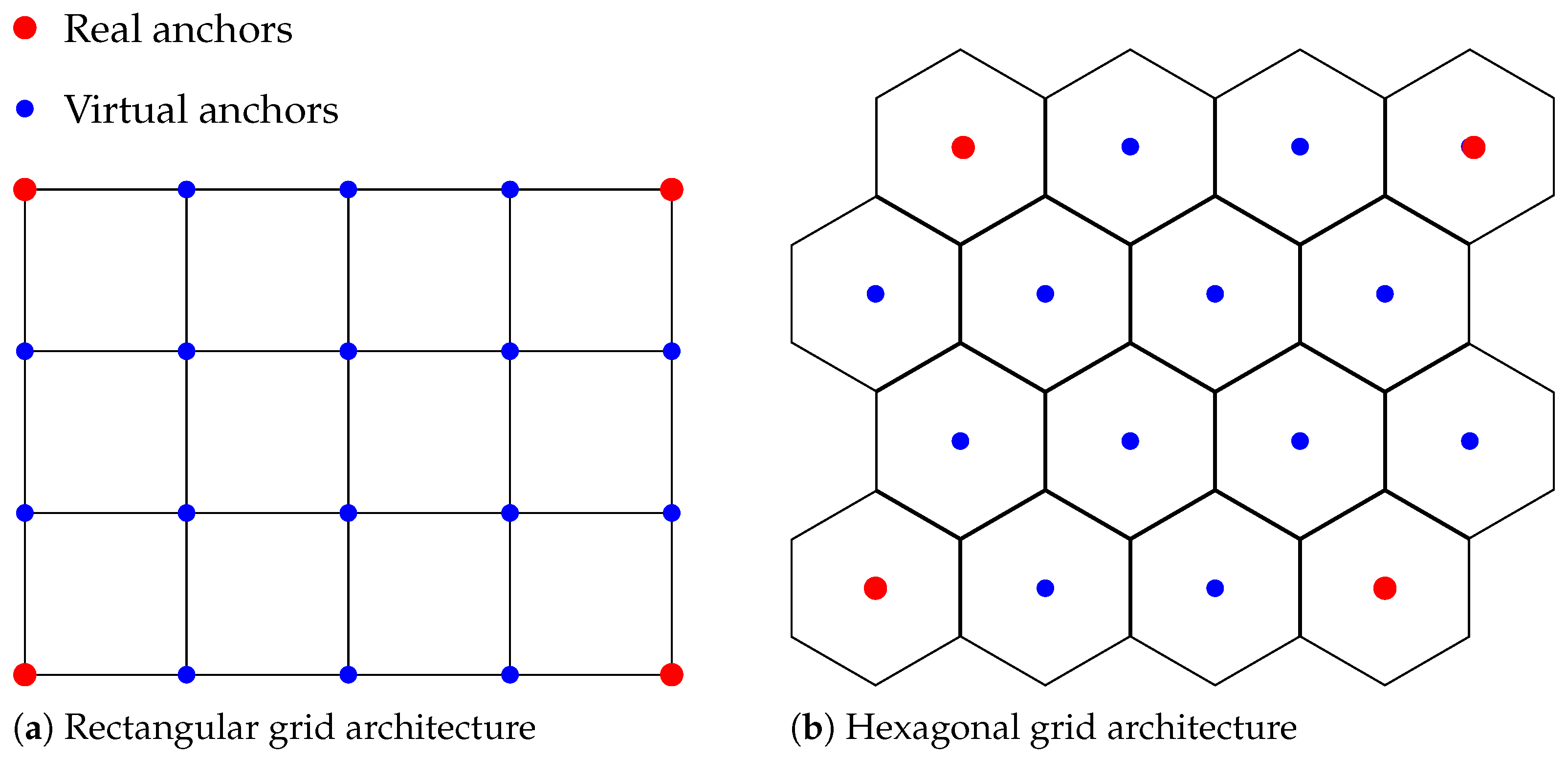

4.3. Virtual Anchors

4.4. Machine Learning Algorithms

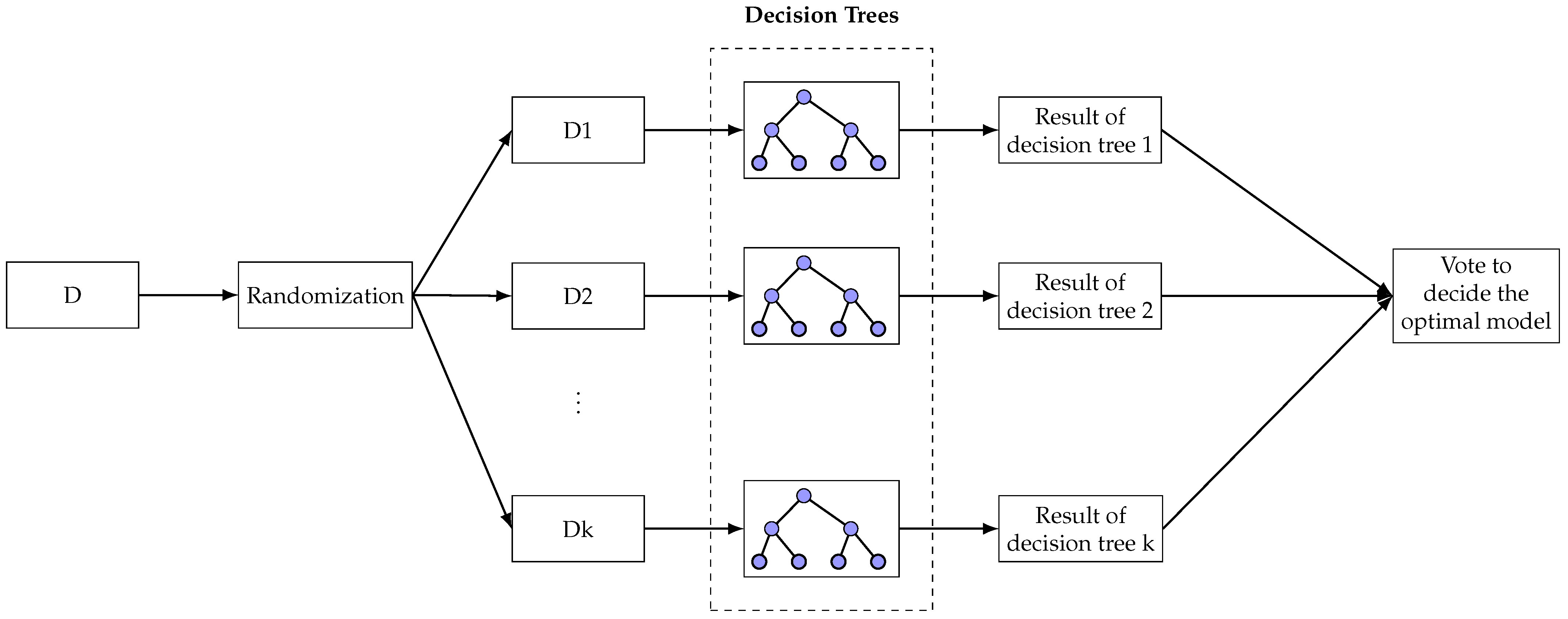

4.4.1. Random Forest Algorithm (RF)

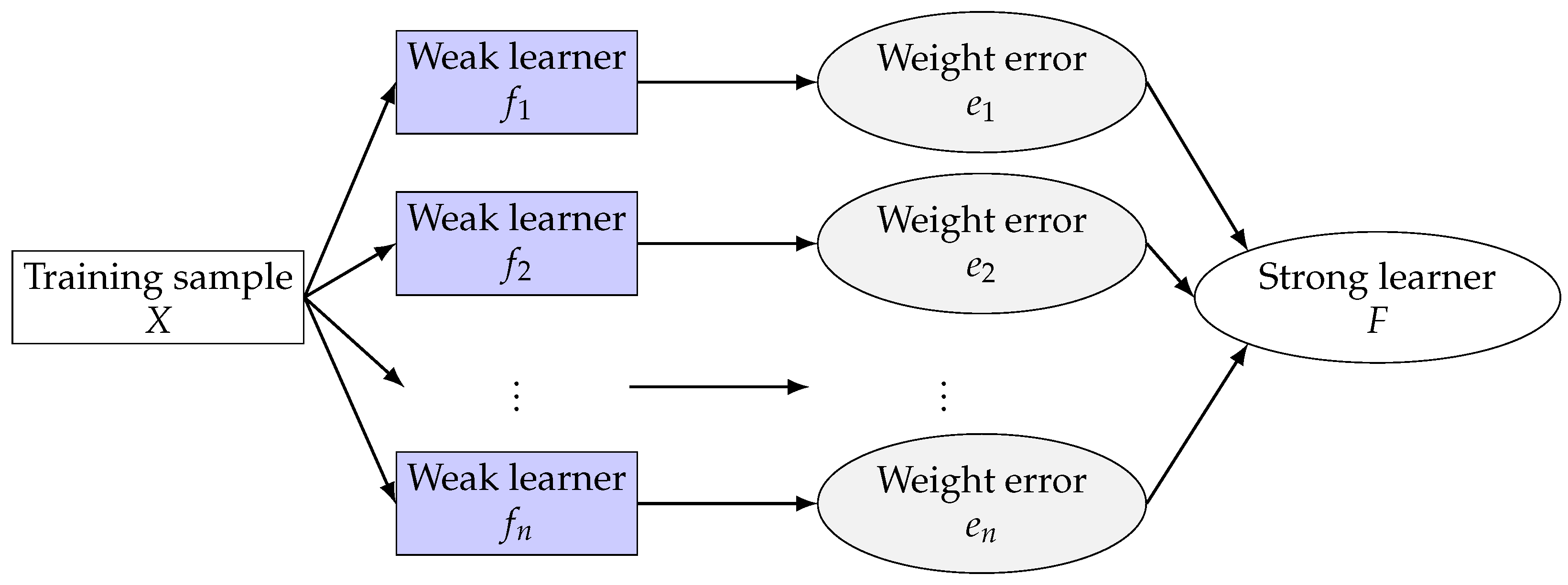

4.4.2. CatBoost Algorithm

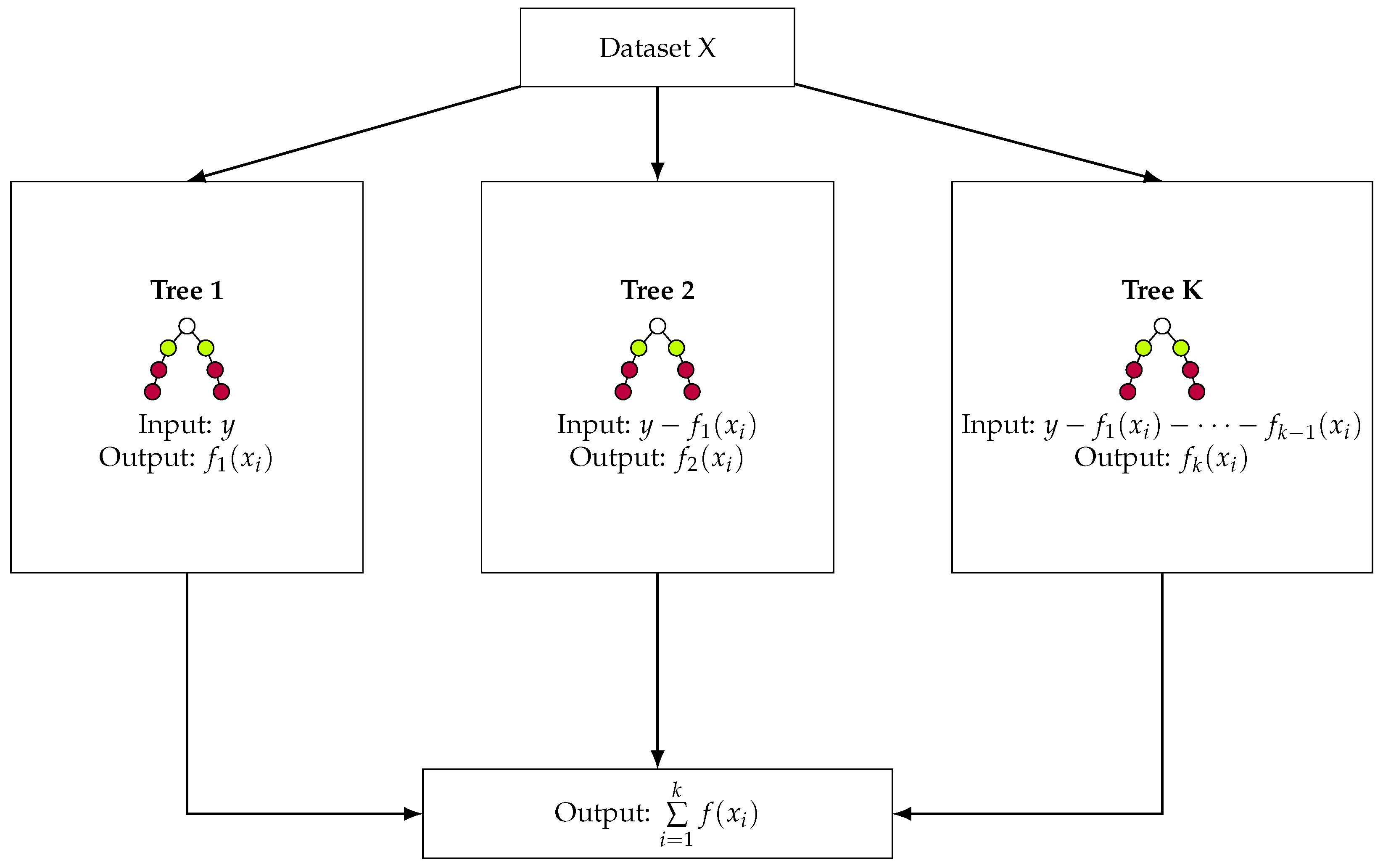

4.4.3. XGBoost Algorithm

4.5. Network Architecture and Deployment

| Algorithm 1: Incremental virtual anchor generation using structured grid rules |

|

5. Proposed Indoor Localization Application

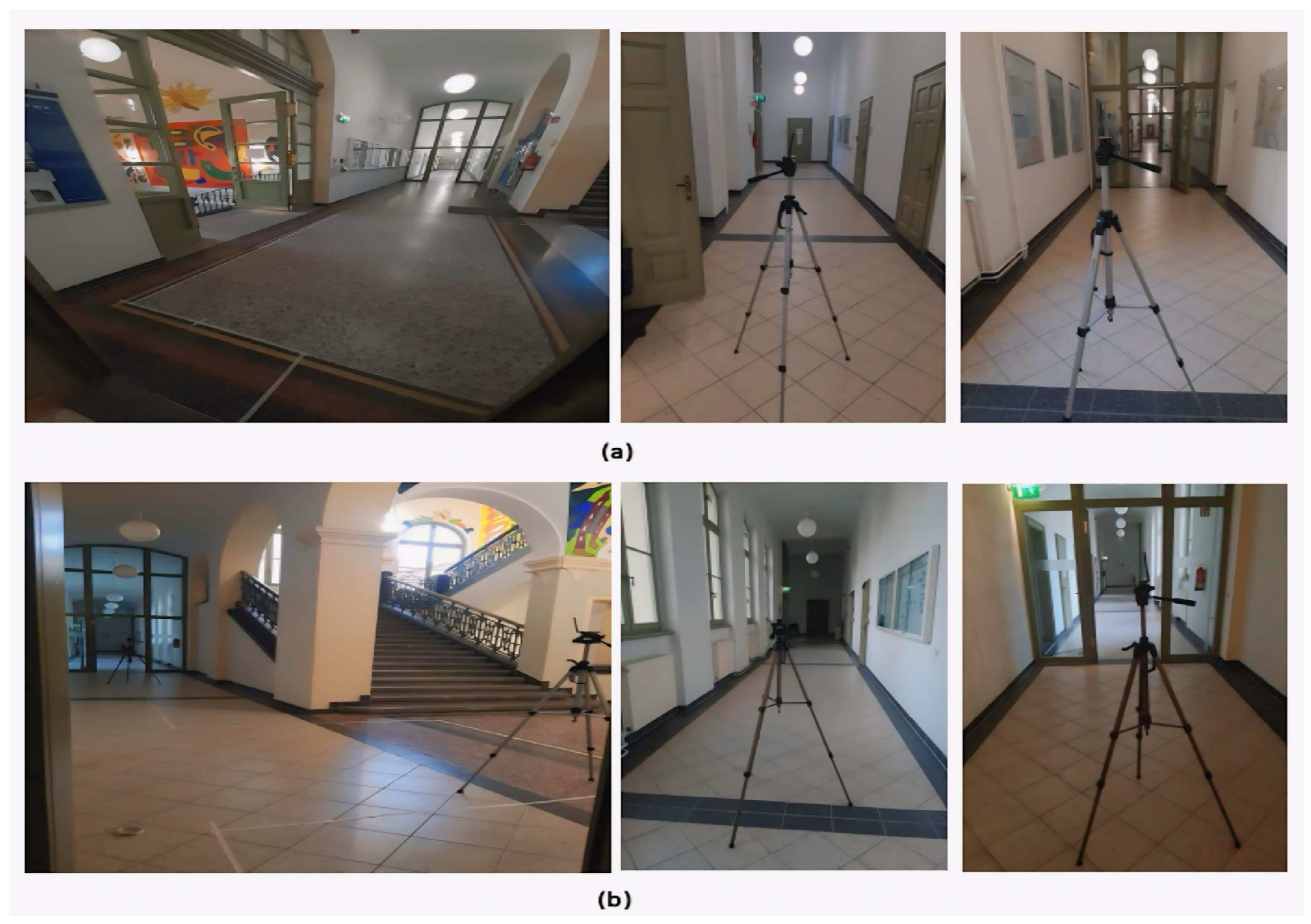

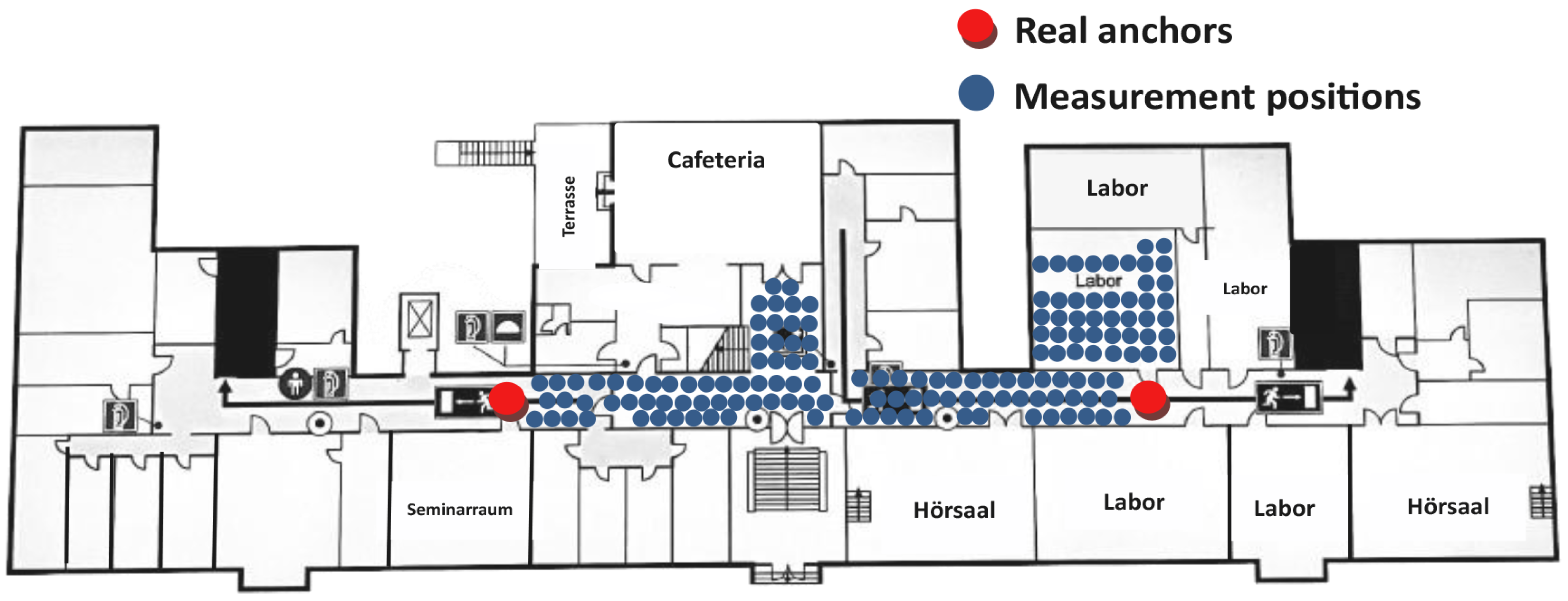

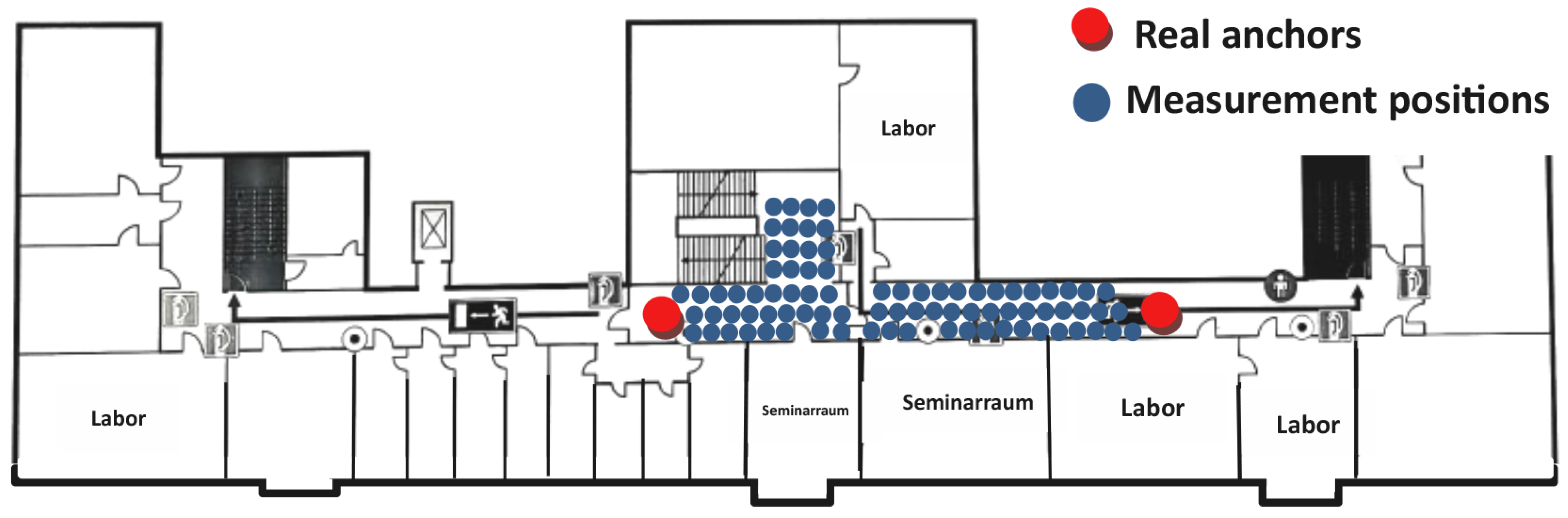

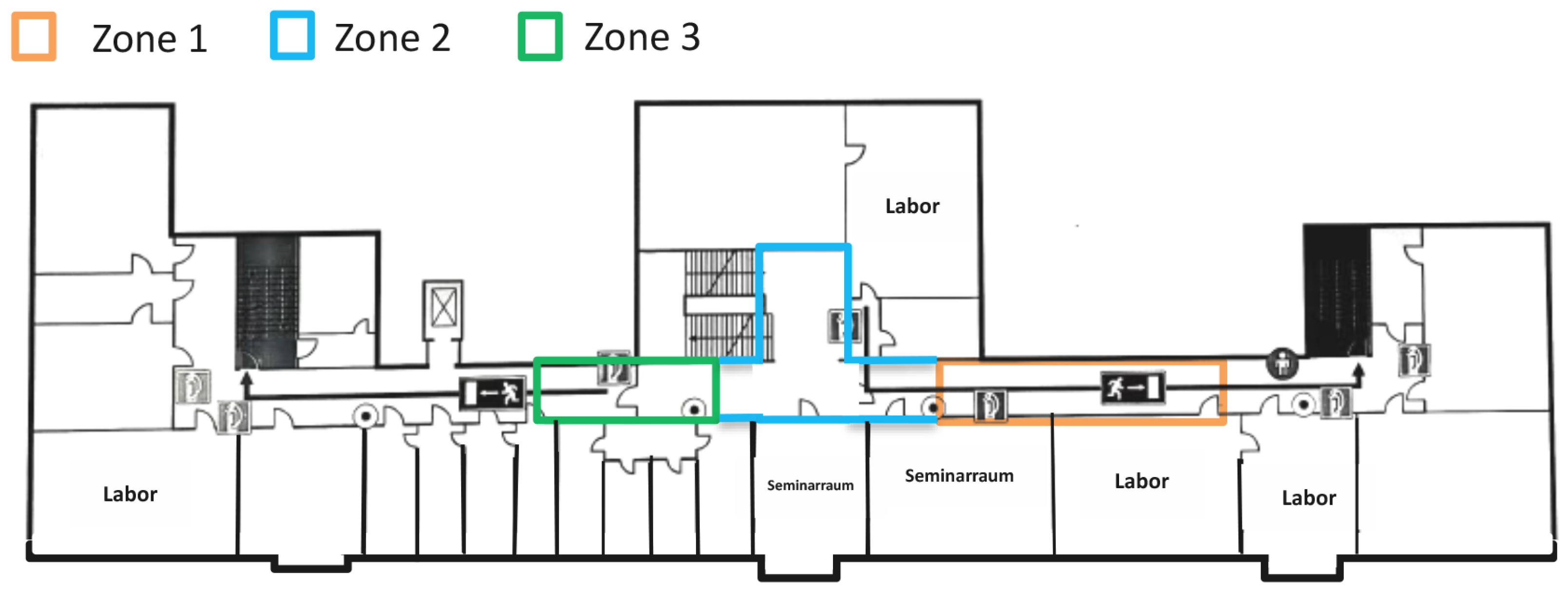

5.1. Environment Setup

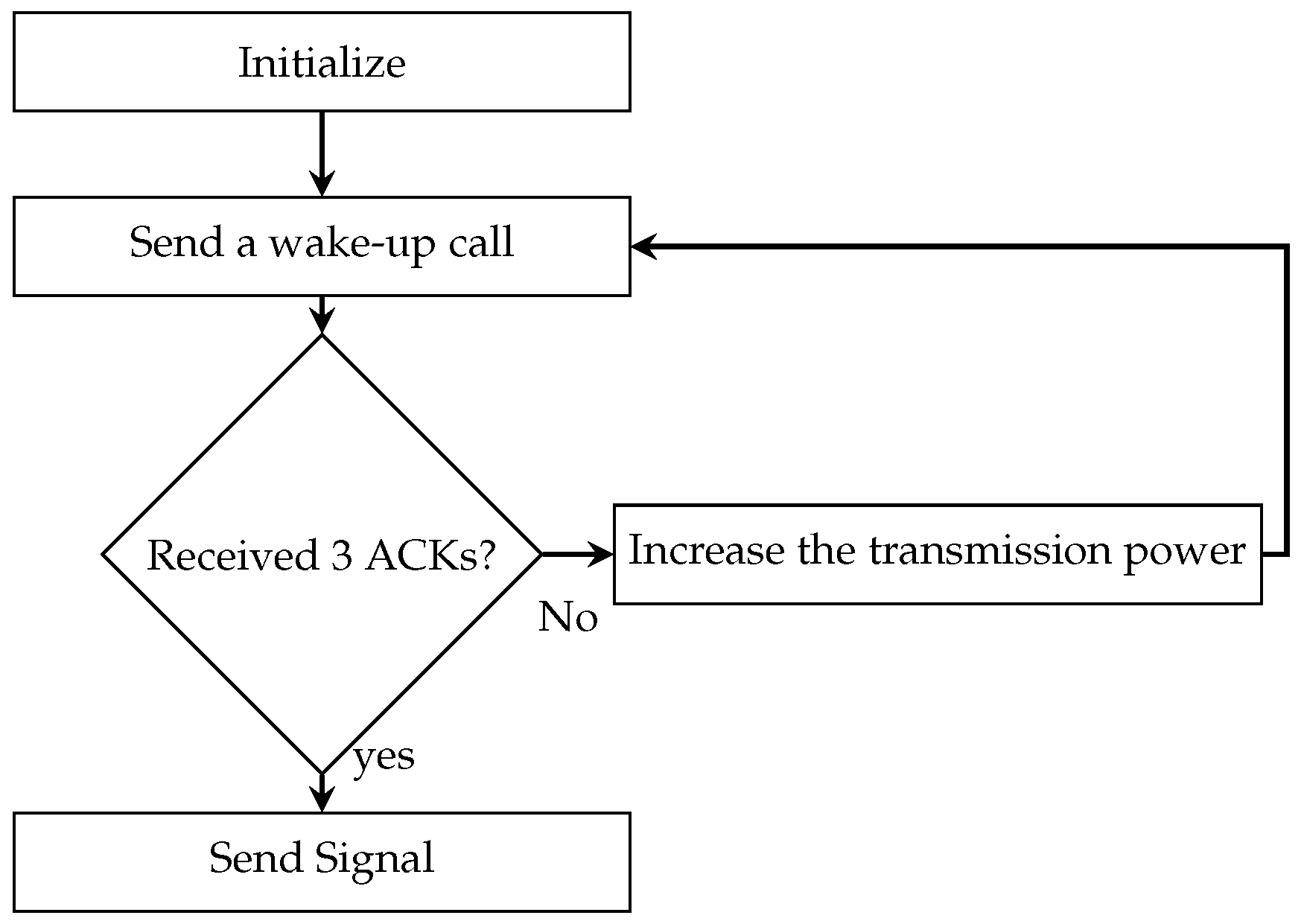

5.2. Communication Protocol

5.3. Data Collection

5.4. Data Preprocessing

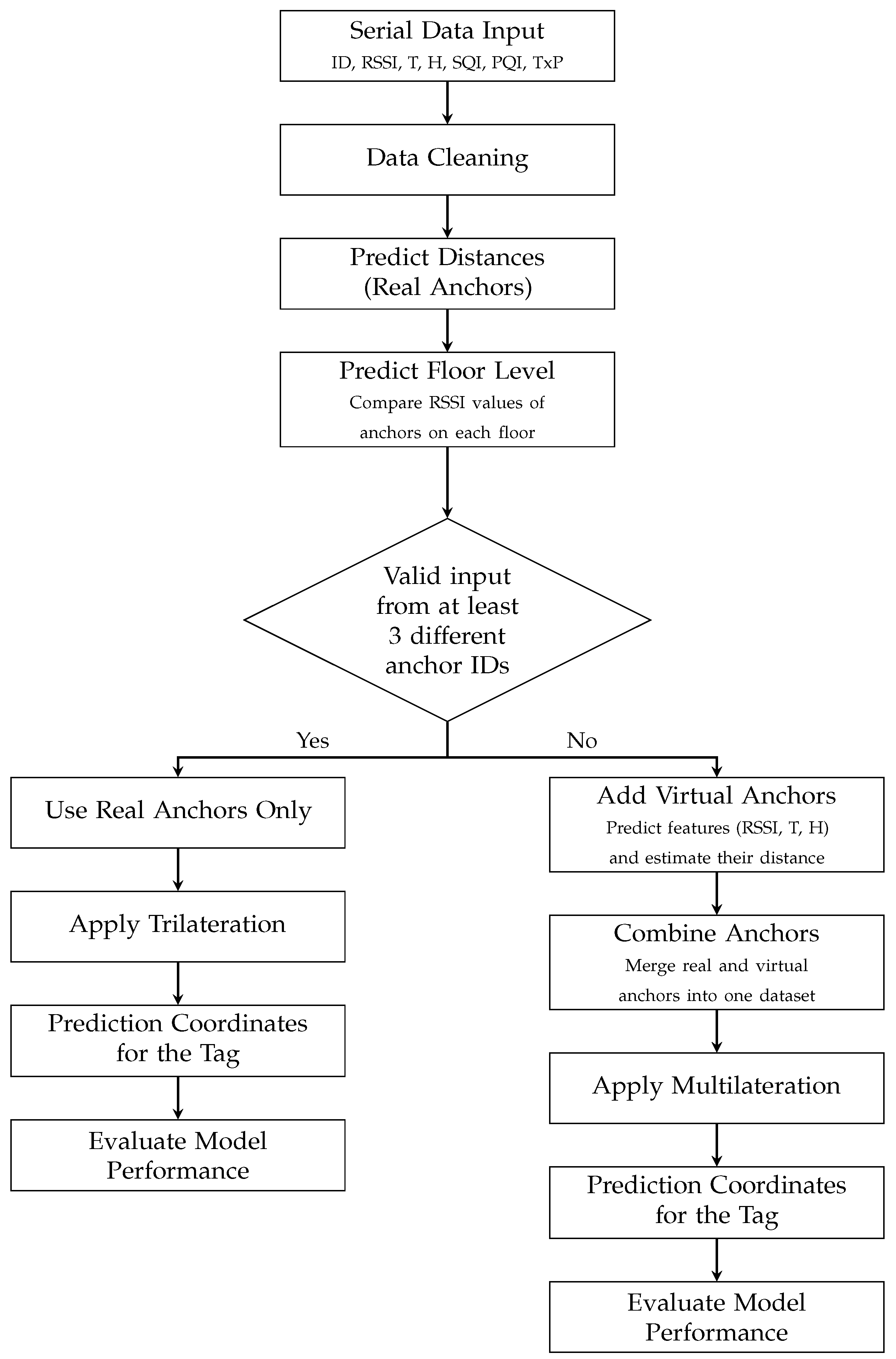

5.5. Proposed Offline Application

5.6. Proposed Online Application

6. Results and Discussion

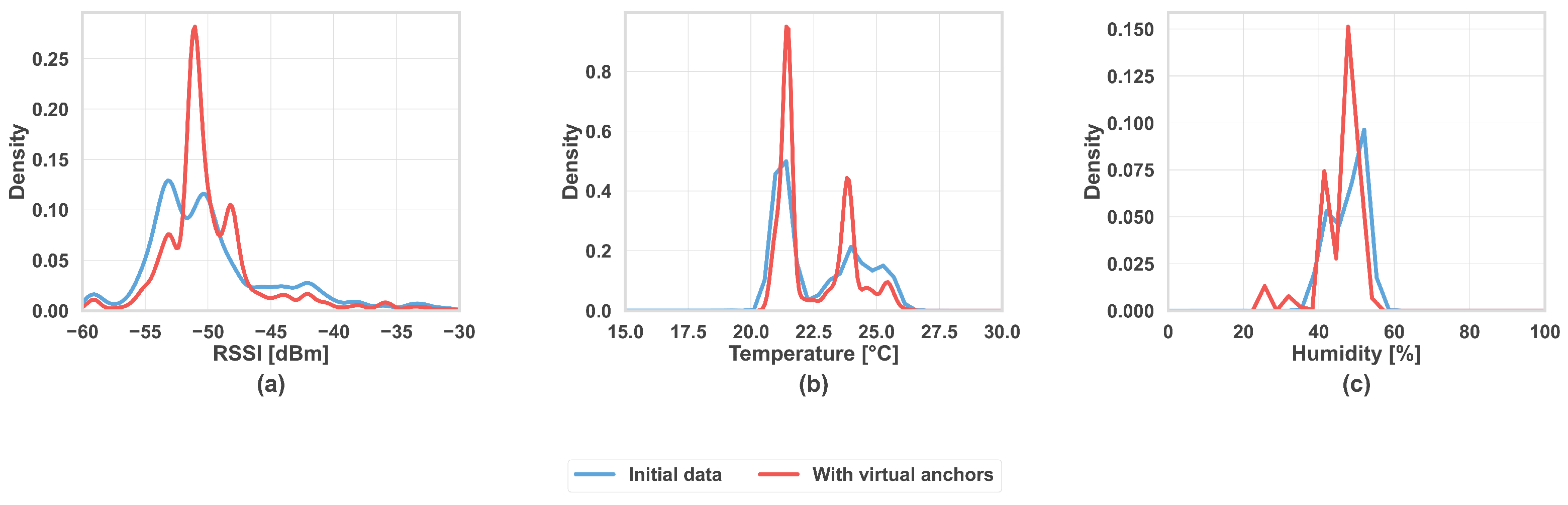

6.1. Prediction of Virtual Anchors

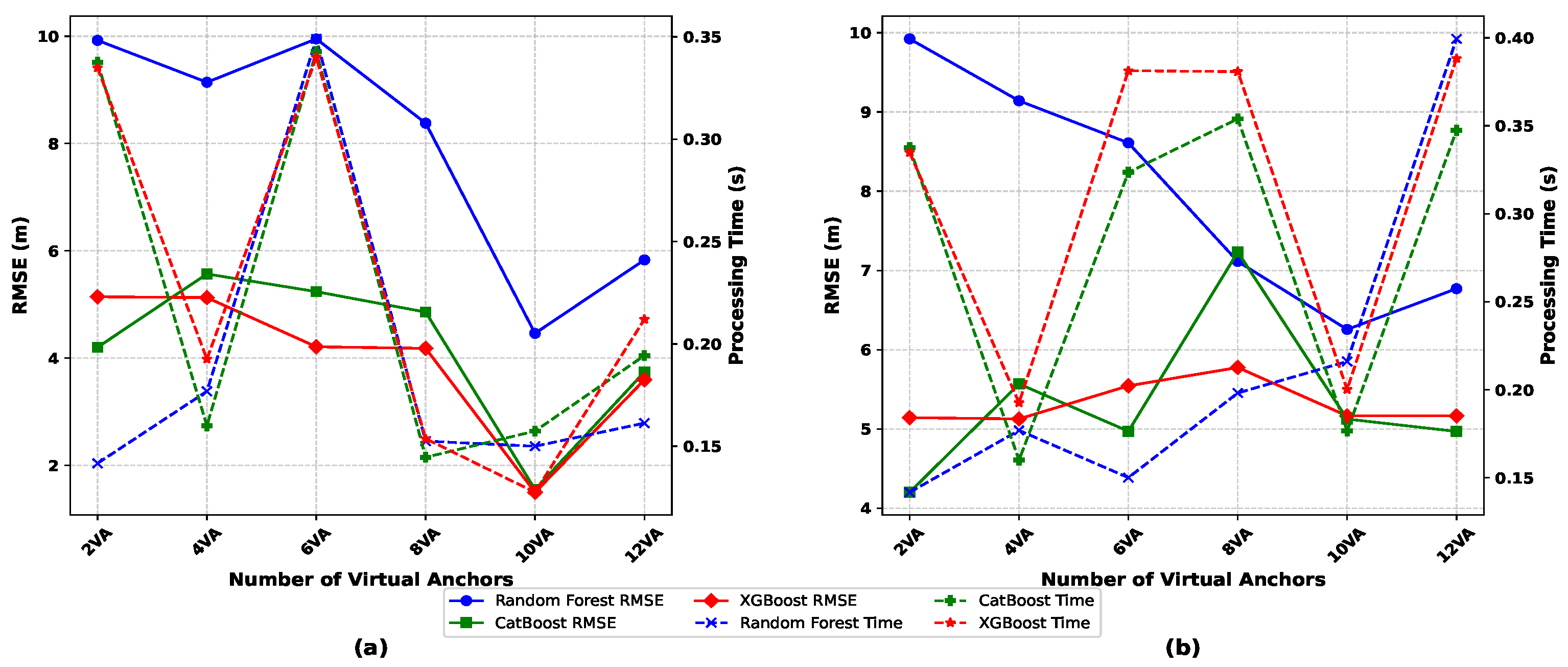

6.2. Distance Prediction Using Different Numbers of Virtual Anchors

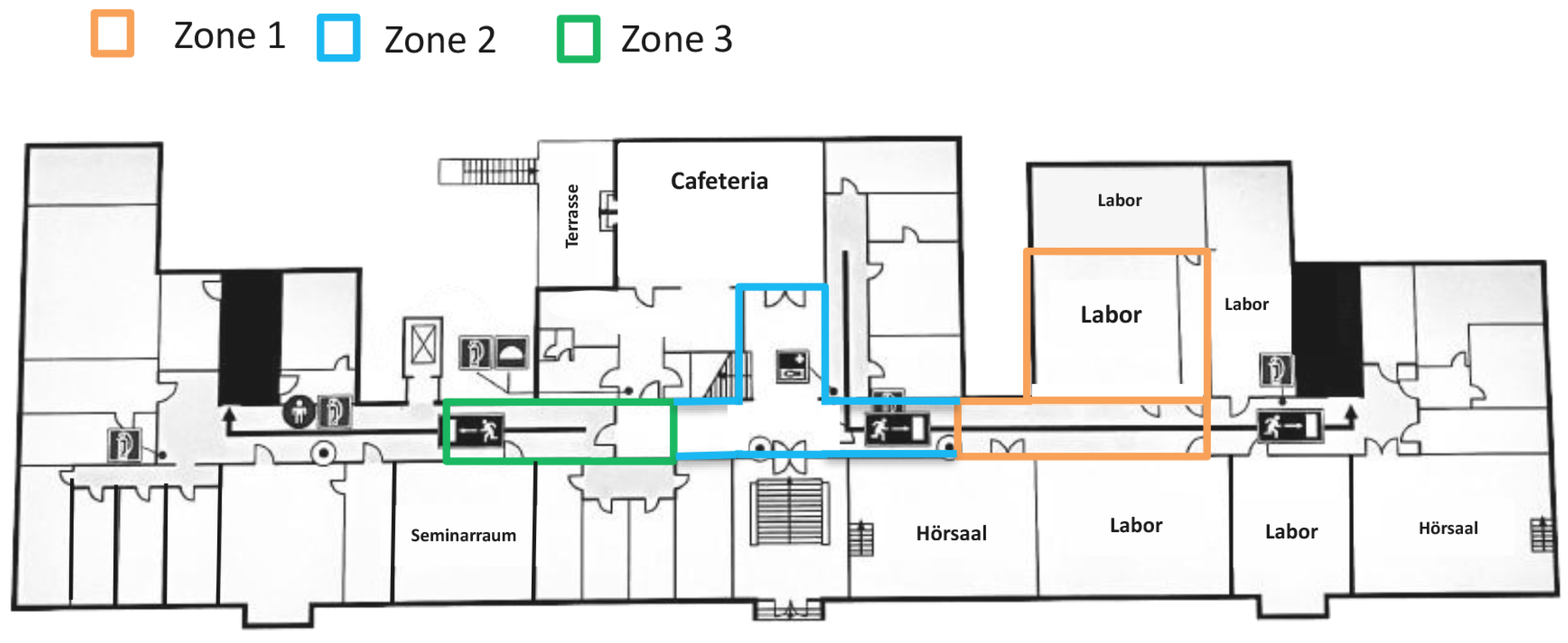

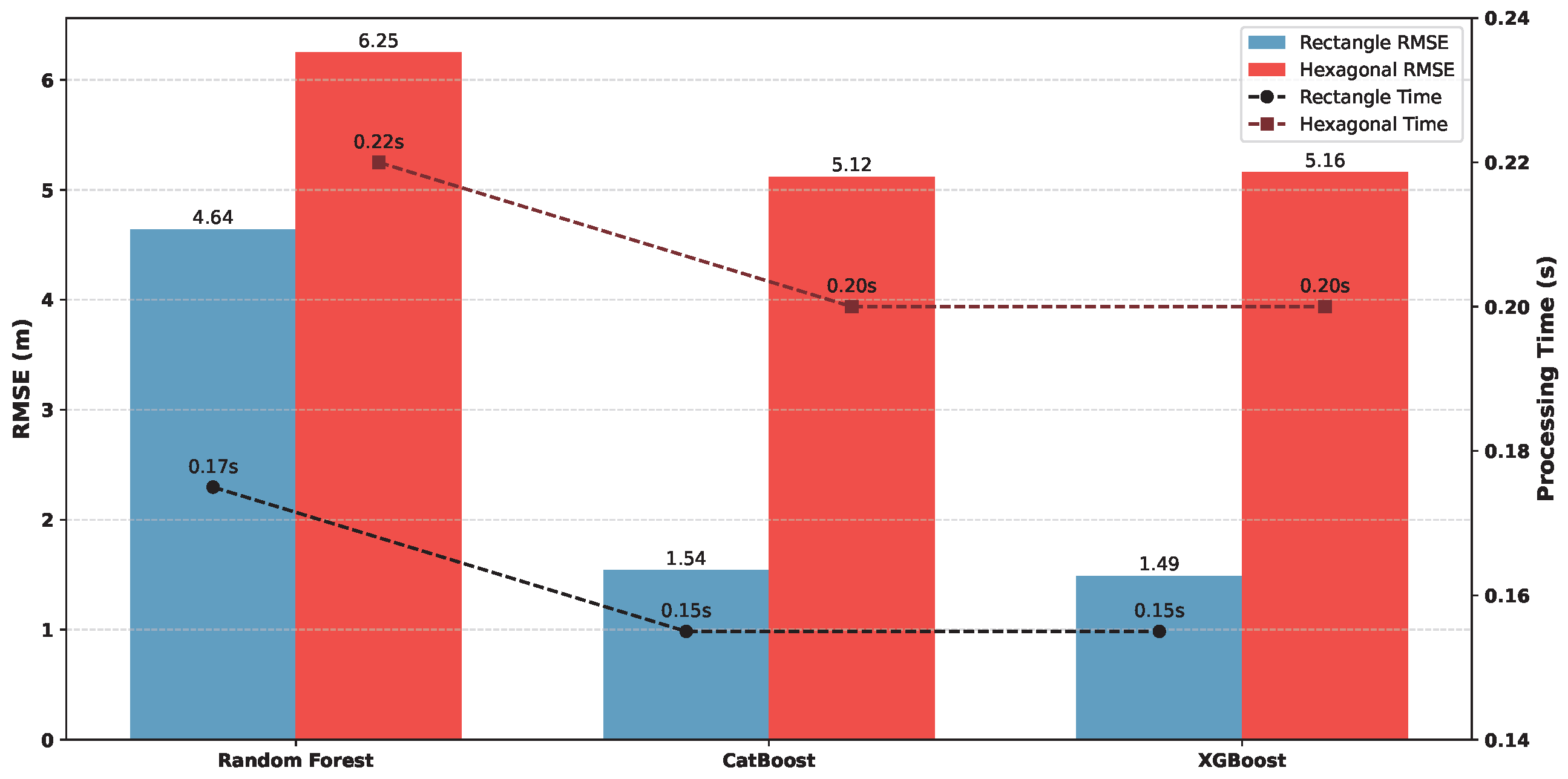

6.3. Performance Evaluation Using 10 Virtual Anchors

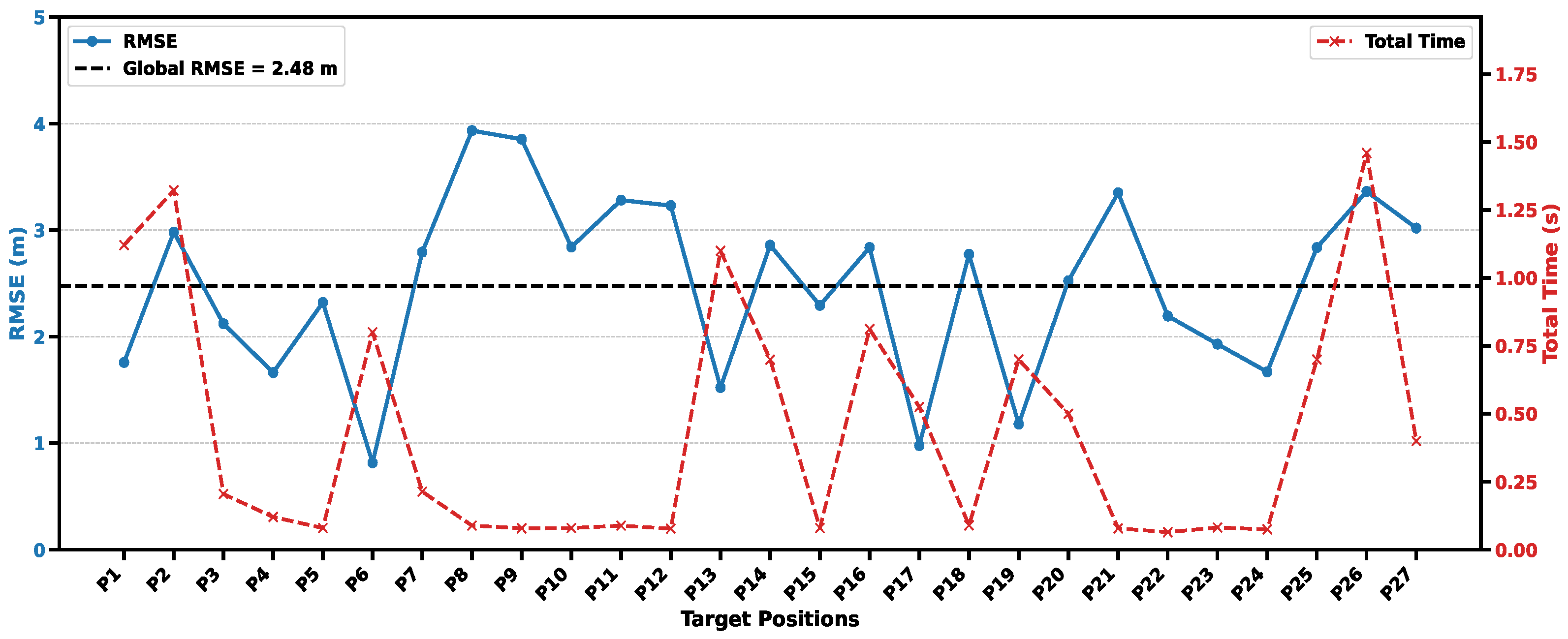

6.4. Performance Evaluation of the Online Process

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IPSs | Indoor Positioning Systems |

| GNSSs | Global Navigation Satellite Systems |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| TOA | Time of Arrival |

| TDOA | Time Difference of Arrival |

| AOA | Angle of Arrival |

| RSSI | Received signal strength indication |

| VAs | Virtual Anchors |

| ANNs | Artificial Neural Networks |

| WuRx | Wake-up receiver |

| WuPT | Wake-up Packet |

| LOS | Line of sight |

| NLOS | Non-line of sight |

| UWB | Ultra-Wide Band |

| XGBoost | Extreme Gradient Boosting |

| CatBoost | Category Boosting |

| RF | Random Forest |

| PQI | Preamble Quality Indicator |

| SQI | Synchronization Quality Indicator |

| Txp | Transmission Power |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

References

- Gu, Y.; Lo, A.; Niemegeers, I. A survey of indoor positioning systems for wireless personal networks. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials 2009, 11, 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassin, A.; Nasser, Y.; Awad, M.; Al-Dubai, A.; Liu, R.; Yuen, C.; Raulefs, R.; Aboutanios, E. Recent advances in indoor localization: A survey on theoretical approaches and applications. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials 2016, 19, 1327–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.; Liu, P.; Liu, S.; Qi, W.; Huang, Y.; You, X.; Jia, X.; Li, X. Efficient joint DOA and TOA estimation for indoor positioning with 5G picocell base stations. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 8005219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yimwadsana, B.; Serey, V.; Sanghlao, S. Performance analysis of an AoA-based Wi-Fi indoor positioning system. In Proceedings of the 2019 19th International Symposium on Communications and Information Technologies (ISCIT); IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Guidara, A.; Derbel, F. A real-time indoor localization platform based on wireless sensor networks. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 12th International Multi-Conference on Systems, Signals & Devices (SSD15); IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhou, T. UWB indoor positioning algorithm based on TDOA technology. In Proceedings of the 2019 10th International Conference on Information Technology in Medicine and Education (ITME); IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 777–782. [Google Scholar]

- Gezici, S. A survey on wireless position estimation. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2008, 44, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailu, T.G.; Guo, X.; Si, H.; Li, L.; Zhang, Y. Theories and methods for indoor positioning systems: A comparative analysis, challenges, and prospective measures. Sensors 2024, 24, 6876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Park, J. An enhanced indoor positioning algorithm based on fingerprint using fine-grained csi and rssi measurements of ieee 802.11 n wlan. Sensors 2021, 21, 2769. [Google Scholar]

- Zafari, F.; Gkelias, A.; Leung, K.K. A survey of indoor localization systems and technologies. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials 2019, 21, 2568–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Chan, S.H.G. Wi-Fi fingerprint-based indoor positioning: Recent advances and comparisons. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials 2015, 18, 466–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, E.J.; Werner, M.; Schauer, L. Indoor navigation using virtual anchor points. In Proceedings of the 2016 European Navigation Conference (ENC); IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Esheh, J.; Affes, S. Effectiveness of data augmentation for localization in WSNs using deep learning for the Internet of Things. Sensors 2024, 24, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limkar, S.; Ashok, W.V.; Wadne, V.; Wagh, S.K.; Wagh, K.; Kumar, A. Energy-Efficient Localization Techniques for Wireless Sensor Networks in Indoor IoT Environments. J. Electr. Syst. 2023, 19, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.B.; Lim, K.W.; Ko, Y.B. Improved virtual anchor selection for AR-assisted sensor positioning in harsh indoor conditions. In Proceedings of the 2020 Global Internet of Things Summit (GIoTS); IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Booranawong, A.; Sengchuai, K.; Buranapanichkit, D.; Jindapetch, N.; Saito, H. RSSI-based indoor localization using multi-lateration with zone selection and virtual position-based compensation methods. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 46223–46239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrollo, G.; Konzen, A.A.; de Morais, W.O.; Pignaton de Freitas, E. Using smart virtual-sensor nodes to improve the robustness of indoor localization systems. Sensors 2021, 21, 3912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Großwindhager, B.; Rath, M.; Kulmer, J.; Bakr, M.S.; Boano, C.A.; Witrisal, K.; Römer, K. SALMA: UWB-based single-anchor localization system using multipath assistance. In Proceedings of the 16th ACM Conference on Embedded Networked Sensor Systems, Shenzhen, China, 4–7 November 2018; pp. 132–144. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Yu, S.; Wei, Z.; Zhou, Z. An Enhanced ZigBee-Based Indoor Localization Method Using Multi-Stage RSSI Filtering and LQI-Aware MLE. Sensors 2025, 25, 2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, F.; Jiang, Y.; Xiong, A.; Su, W.; He, L. A node localization algorithm based on multi-granularity regional division and the lagrange multiplier method in wireless sensor networks. Sensors 2016, 16, 1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meissner, P.; Gigl, T.; Witrisal, K. UWB sequential Monte Carlo positioning using virtual anchors. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference on Indoor Positioning and Indoor Navigation; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Leitinger, E.; Fröhle, M.; Meissner, P.; Witrisal, K. Multipath-assisted maximum-likelihood indoor positioning using UWB signals. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Communications Workshops (ICC); IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 170–175. [Google Scholar]

- Fromm, R.; Kanoun, O.; Derbel, F. An improved wake-up receiver based on the optimization of low-frequency pattern matchers. Sensors 2023, 23, 8188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schott, L.; Fromm, R.; Bouattour, G.; Kanoun, O.; Derbel, F. Analytical and experimental performance analysis of enhanced wake-up receivers based on low-power base-band amplifiers. Sensors 2022, 22, 2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souissi, R.; Ktata, I.; Sahnoun, S.; Fakhfakh, A.; Derbel, F. Improved rssi distribution for indoor localization application based on real data measurements. In Proceedings of the 2024 21st International Multi-Conference on Systems, Signals & Devices (SSD); IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 486–491. [Google Scholar]

- Guidara, A.; Fersi, G.; Derbel, F.; Jemaa, M.B. Impacts of Temperature and Humidity variations on RSSI in indoor Wireless Sensor Networks. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2018, 126, 1072–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghdi, S.; O’Keefe, K. Combining multichannel RSSI and vision with artificial neural networks to improve BLE trilateration. Sensors 2022, 22, 4320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Yuan, C.; Yue, M.; Ma, T. A novel localization algorithm based on RSSI and multilateration for indoor environments. Electronics 2022, 11, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cengiz, K. Comprehensive analysis on least-squares lateration for indoor positioning systems. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 8, 2842–2856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathnayake, R.M.M.R.; Maduranga, M.W.P.; Tilwari, V.; Dissanayake, M.B. RSSI and Machine Learning-Based Indoor Localization Systems for Smart Cities. Eng 2023, 4, 1468–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wen, Z.; Su, H. An approach using random forest intelligent algorithm to construct a monitoring model for dam safety. Eng. Comput. 2021, 37, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuliana, H.; Basuki, S.; Hidayat, M.R.; Charisma, A.; Vidyaningtyas, H. Hyperparameter Optimization of Random Forest Algorithm to Enhance Performance Metric Evaluation of 5G Coverage Prediction. Bul. Pos Dan Telekomun. 2024, 22, 75–90. [Google Scholar]

- Prokhorenkova, L.; Gusev, G.; Vorobev, A.; Dorogush, A.V.; Gulin, A. CatBoost: Unbiased boosting with categorical features. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Montréal, QC, Canada, 3–8 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hancock, J.; Khoshgoftaar, T. CatBoost for big data: An interdisciplinary review. J. Big Data 2020, 7, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmasry, N.; Elshaarawy, M. Hybrid metaheuristic optimized Catboost models for construction cost estimation of concrete solid slabs. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Meng, X.; Kan, G.; Wang, J.; Li, G.; Liu, B.; Liu, C.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lu, J. Predicting the sound speed of seafloor sediments in the east China sea based on an XGBoost algorithm. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, V. Exploring Key XGBoost Hyperparameters: A Study on Optimal Search Spaces and Practical Recommendations for Regression and Classification. Int. J. All Res. Educ. Sci. Methods (IJARESM) 2024, 12, 2455–6211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souissi, R.; Ktata, I.; Sahnoun, S.; Fakhfakh, A.; Derbel, F. Analysis of Different Architectures for RSSI Based Indoor Localization using Trilateration Technique. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 4th International Maghreb Meeting of the Conference on Sciences and Techniques of Automatic Control and Computer Engineering (MI-STA); IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 446–451. [Google Scholar]

- Souissi, R.; Sahnoun, S.; Baazaoui, M.K.; Fromm, R.; Fakhfakh, A.; Derbel, F. A self-localization algorithm for mobile targets in indoor wireless sensor networks using wake-up media access control protocol. Sensors 2024, 24, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, S.; Luengo, J.; Herrera, F. Data Preprocessing in Data Mining; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 72. [Google Scholar]

- Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Friedman, J. The Elements of Statistical Learning; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Yaro, A.S.; Maly, F.; Prazak, P. Outlier detection in time-series receive signal strength observation using Z-score method with S n scale estimator for indoor localization. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- STMicroelectronics. SPIRIT1 Low Data Rate RF Transceiver Datasheet. Available online: https://www.mouser.in/pdfDocs/spirit1.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Chiu, C.C.; Wu, H.Y.; Chen, P.H.; Chao, C.E.; Lim, E.H. Indoor Localization Using 6G Time-Domain Feature and Deep Learning. Electronics 2025, 14, 1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, T.; Draxler, R.R. Root mean square error (RMSE) or mean absolute error (MAE)?—Arguments against avoiding RMSE in the literature. Geosci. Model Dev. 2014, 7, 1247–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parzen, E. On estimation of a probability density function and mode. Ann. Math. Stat. 1962, 33, 1065–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Technologies | Algorithms | Number of Physical Anchors | Number of Virtual Anchors | Tested Area | Deployment Type | Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [15] | UWB | Not defined | 1 | 25 | Open space: Office: | Real implementation | Open space: Office: |

| [16] | RSSI, ZigBee (2.4 Ghz) Multilateration | Not defined | 4 | 12 (3 per zone) | Room: Corridor: | Real implementation | Room: Corridor: |

| [17] | RSSI, Fingerprinting | ANN | 2 | 2 | Simulation | X-axis: Y-axis: | |

| [18] | UWB | Not defined | 1 | 4 | Room A: Room B: | Real implementation | Room A: Room B: |

| Anchor Number | Positions (x, y) | Floor |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | (1.56 m, 15.54 m) | 1 |

| 3 | (1.54 m, 53.82 m) | 1 |

| 4 | (1.44 m, 43.76 m) | 2 |

| 5 | (1.29 m, 19.48 m) | 2 |

| Number of Virtual Anchors | 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RF (m) | 3.07 | 3.87 | 3.58 | 4.39 | 2.73 | 4.61 |

| CatBoost (m) | 2.40 | 2.65 | 2.75 | 2.88 | 2.33 | 2.85 |

| XGBoost (m) | 2.26 | 2.67 | 2.62 | 2.84 | 2.02 | 2.79 |

| Number of Virtual Anchors | 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RF (m) | 3.07 | 4.12 | 4.03 | 3.75 | 4.64 | 4.64 |

| CatBoost (m) | 2.13 | 2.87 | 2.67 | 4.33 | 3.30 | 5.52 |

| XGBoost (m) | 2.27 | 2.85 | 2.83 | 4.18 | 3.18 | 6.19 |

| Zone | Distance Range Between VA and Target (m) | Path Loss Exponent | RMSE (m) | Environment Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zone 1 | 4.33–25 | 2.10–2.35 | 3.45 | NLOS |

| Zone 2 | 4.33–15.89 | 1.81–2.78 | 2.52 | NLOS, LOS |

| Zone 3 | 1.33–17.58 | 2.10–2.65 | 4.32 | NLOS |

| Zone | Distance Range Between VA and Target (m) | Path Loss Exponent | RMSE (m) | Environment Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zone 1 | 5.91–19.95 | 2.10–2.23 | 2.39 | NLOS |

| Zone 2 | 1.52–11.89 | 1.68–2 | 1.82 | LOS |

| Zone 3 | 6.59–14.07 | 1.84–1.93 | 2.08 | LOS |

| AI Algorithms | Model | Metrics | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| RF | Test Dataset | MAE | 1.93 m |

| R2 | 0.86 | ||

| Validation Dataset | MAE | 1.96 m | |

| R2 | 0.85 | ||

| CatBoost | Test Dataset | MAE | 1.59 m |

| R2 | 0.90 | ||

| Validation Dataset | MAE | 1.61 m | |

| R2 | 0.89 | ||

| XGBoost | Test Dataset | MAE | 1.01 m |

| R2 | 0.92 | ||

| Validation Dataset | MAE | 1.04 m | |

| R2 | 0.92 |

| AI Algorithms | Model | Metrics | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| RF | Test Dataset | MAE | 3.44 m |

| R2 | 0.76 | ||

| Validation Dataset | MAE | 3.48 m | |

| R2 | 0.75 | ||

| CatBoost | Test Dataset | MAE | 2.20 m |

| R2 | 0.85 | ||

| Validation Dataset | MAE | 2.25 m | |

| R2 | 0.84 | ||

| XGBoost | Test Dataset | MAE | 2.06 m |

| R2 | 0.88 | ||

| Validation Dataset | MAE | 2.09 m | |

| R2 | 0.88 |

| Model | RMSE (m) | Min RMSE (m) | Max RMSE (m) | 90% RMSE (m) | 70% RMSE (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XGBoost | 2.48 | 0.81 | 3.93 | 2.32 | 2.10 |

| Floor | Number of Positions | Area (m2) | RMSE (m) | Min RMSE (m) | Max RMSE (m) | 90% RMSE (m) | 70% RMSE (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Floor 1 | 14 | 196.5 | 2.42 | 0.98 | 3.36 | 2.29 | 2.05 |

| Floor 2 | 13 | 170.4 | 2.55 | 0.81 | 3.93 | 2.32 | 2.10 |

| Reference | Technology | Hardware Cost | Real Anchors | Tested Area | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [18] | UWB | High | 1 | Room A: Room B: | Room A: Room B: |

| [15] | UWB | High | 1 | Open space: Office: | Open space: Office: |

| [16] | RSSI Multilateration | Low | 4 | Room: Corridor: | Room: Corridor: |

| [17] | RSSI, ZigBee (2.4 GHz) Multilateration | Low | 2 | X-axis: Y-axis: | |

| This work | RSSI, WuRx | Low | 4 | 366.9 m2 2 floors | Offline: Online: |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chiboub, S.; Chabchoub, A.; Souissi, R.; Sahnoun, S.; Fakhfakh, A.; Derbel, F. AI-Based Indoor Localization Using Virtual Anchors in Combination with Wake-Up Receiver Nodes. Electronics 2026, 15, 584. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15030584

Chiboub S, Chabchoub A, Souissi R, Sahnoun S, Fakhfakh A, Derbel F. AI-Based Indoor Localization Using Virtual Anchors in Combination with Wake-Up Receiver Nodes. Electronics. 2026; 15(3):584. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15030584

Chicago/Turabian StyleChiboub, Sirine, Aziza Chabchoub, Rihab Souissi, Salwa Sahnoun, Ahmed Fakhfakh, and Faouzi Derbel. 2026. "AI-Based Indoor Localization Using Virtual Anchors in Combination with Wake-Up Receiver Nodes" Electronics 15, no. 3: 584. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15030584

APA StyleChiboub, S., Chabchoub, A., Souissi, R., Sahnoun, S., Fakhfakh, A., & Derbel, F. (2026). AI-Based Indoor Localization Using Virtual Anchors in Combination with Wake-Up Receiver Nodes. Electronics, 15(3), 584. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15030584