A Digital Twins Platform for Digital Manufacturing

Abstract

1. Introduction

- A novel digital twin framework for creating and managing physical products, including physical twins consisting of materials, sensors, and actuators for measuring and affecting the product’s properties; a DT Description of the physical product, which incorporates an AI model for ensuring product consistency/quality; and digital threads for physical to virtual twin communication using existing standard industrial IoT protocols.

- A novel digital twin-based platform for digital manufacturing that manages the digital twin lifecycle and supports the development of digital manufacturing solutions that improve the productivity and resilience of manufacturing production lines.

- Functional assessment of the proposed platform through developing two digital manufacturing applications utilizing (i) a digital twin of a composite airframe product and (ii) a digital twin of an evaporator machine, demonstrating the platform’s capability to support digital manufacturing applications to improve product quality.

2. Related Work

2.1. Digital Twins

2.2. IoT Platforms Supporting Digital Twins

2.3. Digital Twins in Manufacturing

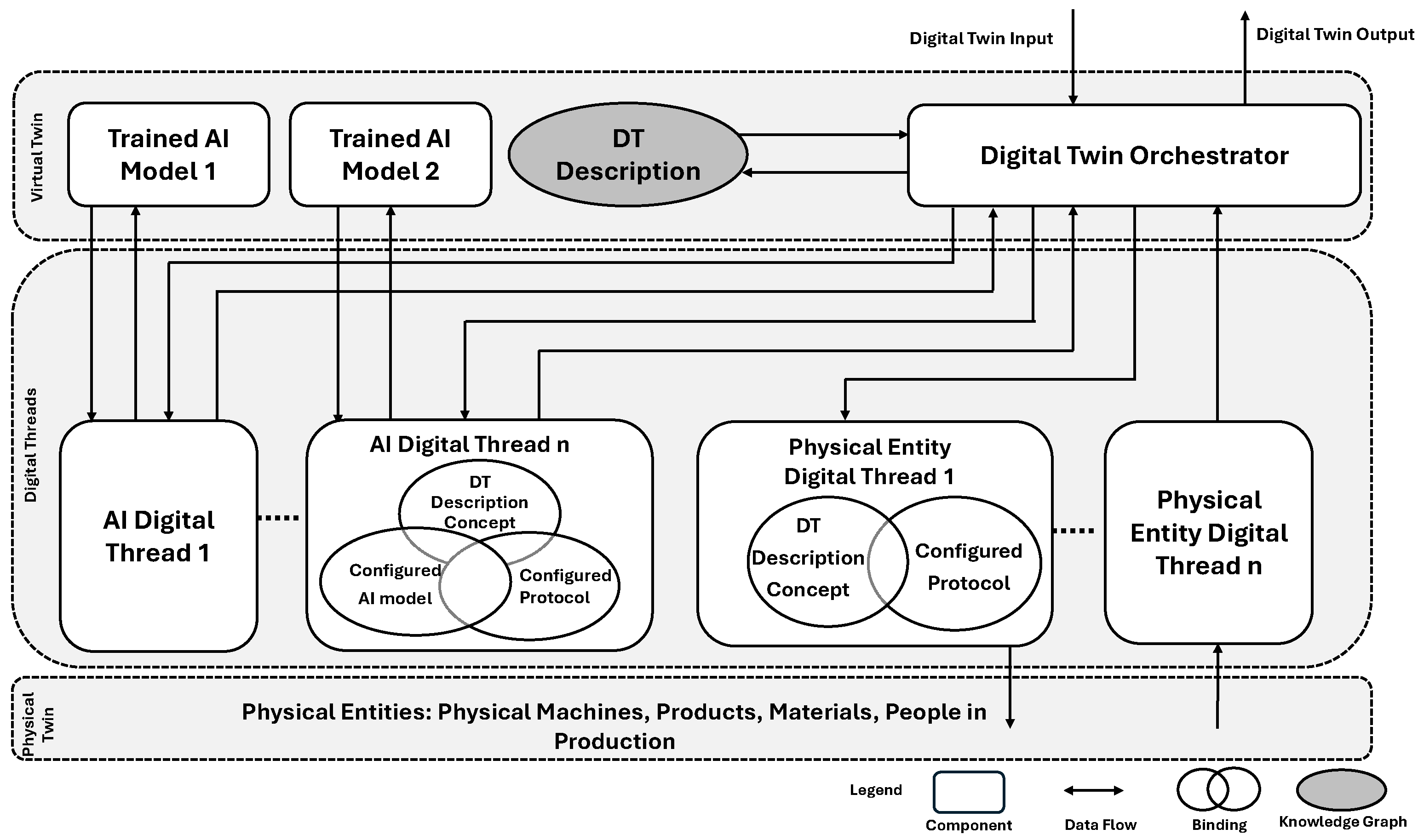

3. Digital Twin Framework

- No digital twin exists without sensors; state information must continuously reflect real-world conditions.

- Simulators generating synthetic data alone do not constitute digital twins.

- Abstraction for applications: Digital representations must enable manufacturing applications to interact without understanding implementation details.

- Three-layer architecture: physical twin, virtual twin (semantic DT Description), and digital threads for bidirectional connectivity.

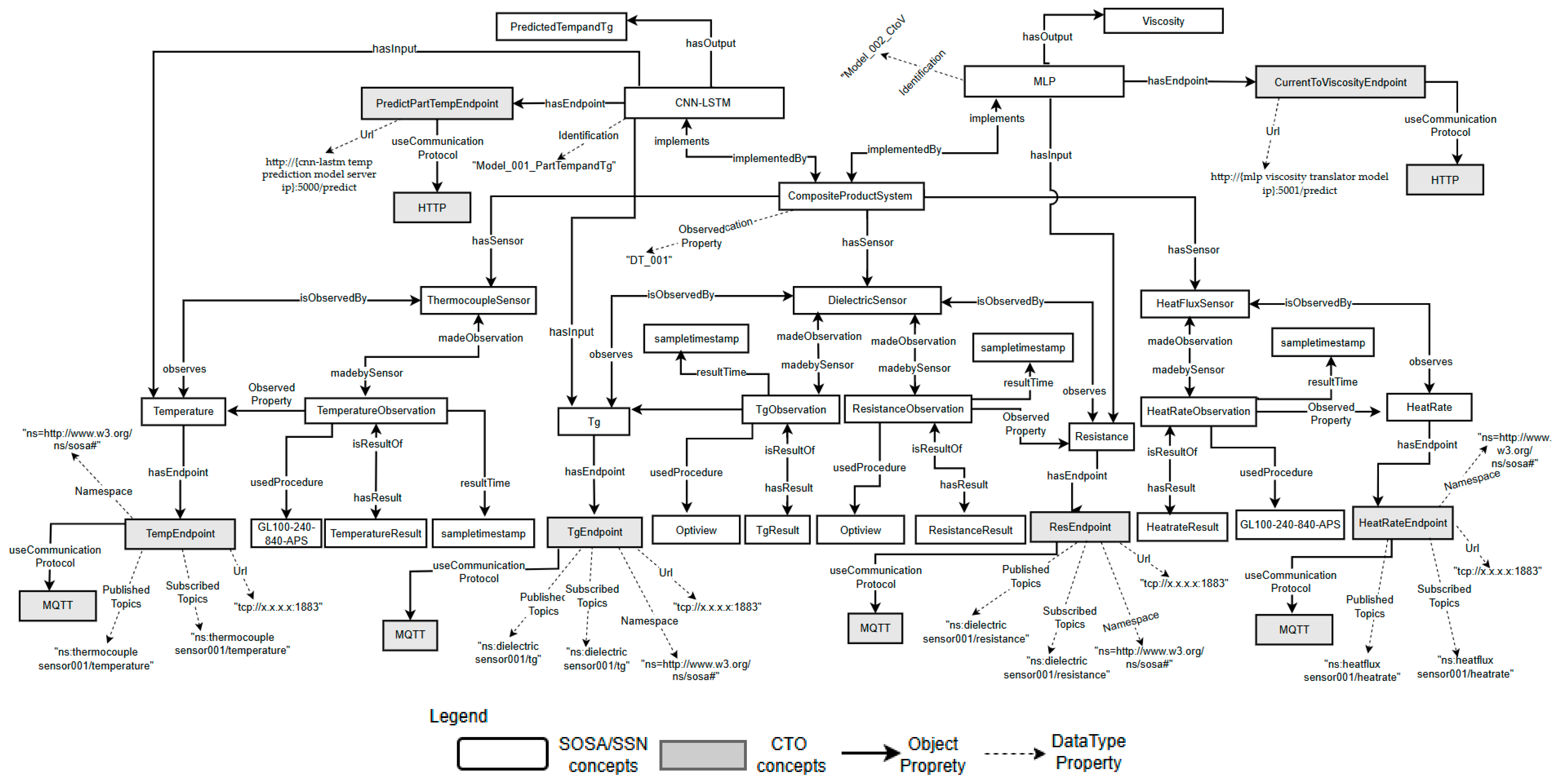

- CTM ontology-based semantically rich knowledge-graph-based representations for complex entities consisting of a physical entity and AI representation.

- Considering additional devices, sensors as the physical twin, when representing entities like products, materials, or people.

- Closed-loop AI control via semantic bindings of AI in the knowledge graph.

- Multi-protocol digital threads to allow for an individual-entity digital twin rather than a generic class-based digital twin.

3.1. Physical Twin

3.2. Virtual Twin

3.2.1. DT Description

3.2.2. Trained AI Model(s)

3.2.3. DT Orchestrator (Conceptual Role)

3.3. Digital Threads

3.3.1. Physical Entity Digital Threads

3.3.2. AI Digital Threads

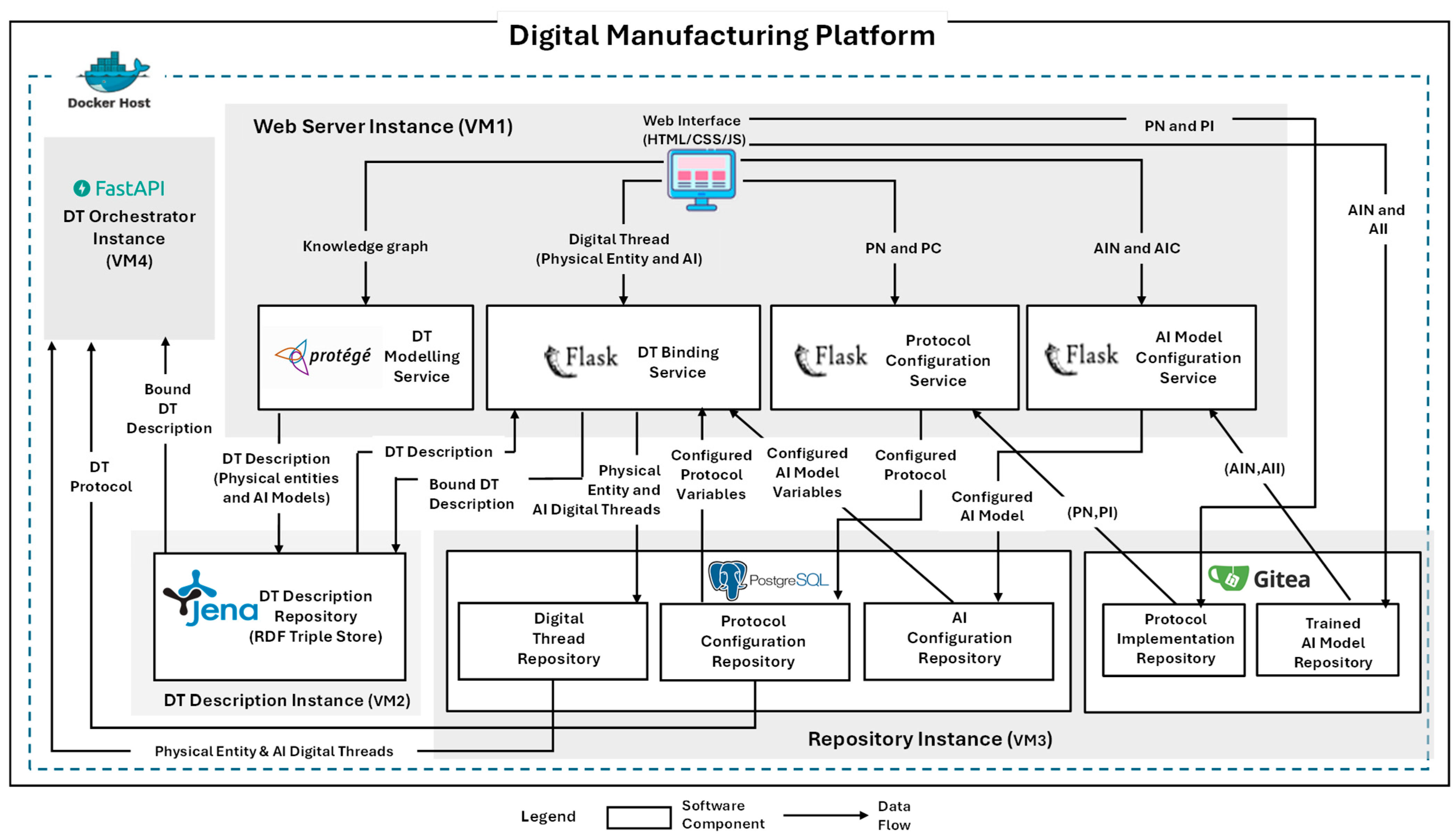

4. Digital Manufacturing Platform

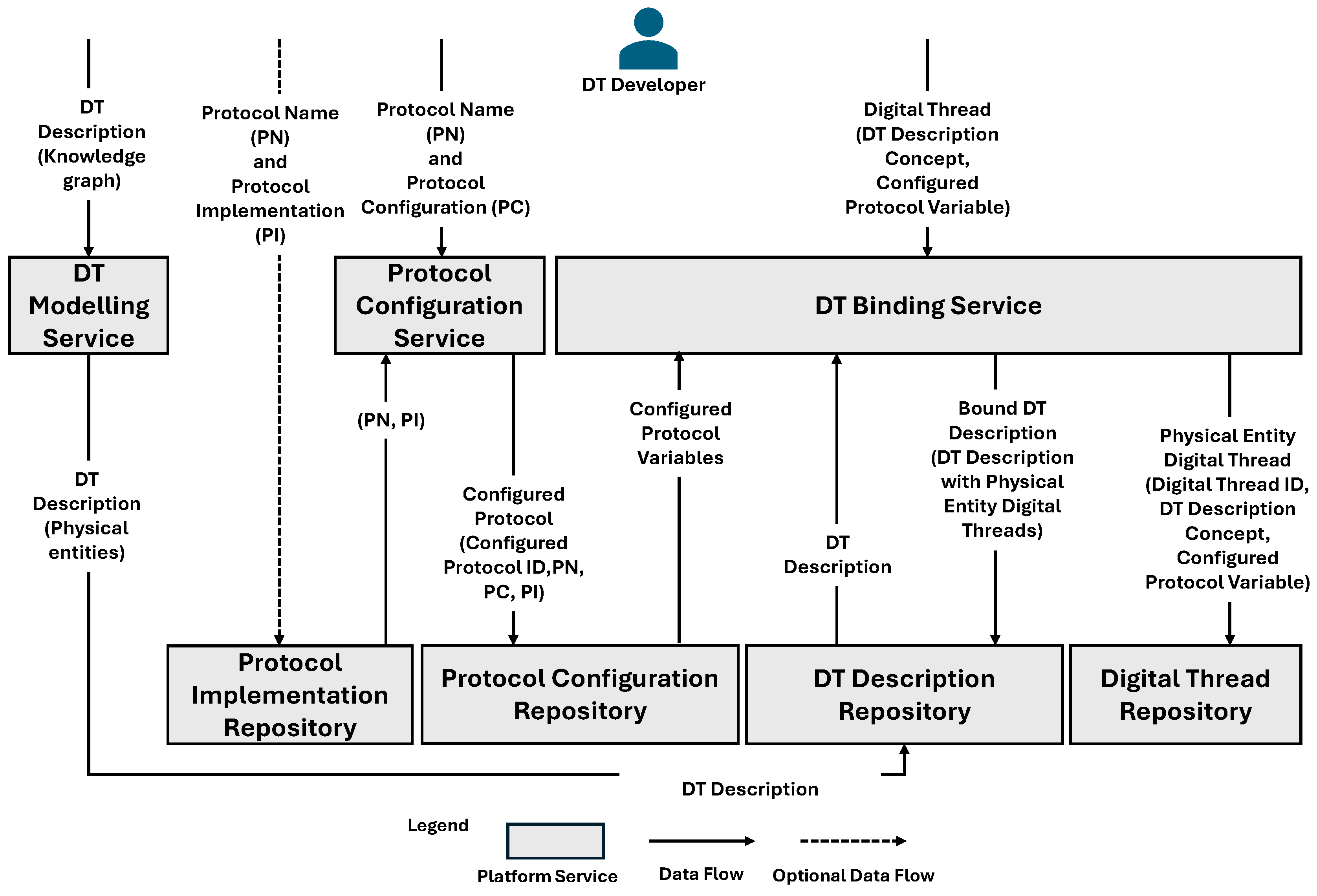

4.1. Digital Manufacturing Platform Supports Physical Entity Representation, Integration, and Interaction in DTs

4.1.1. DT Modelling Service

4.1.2. DT Description Repository

4.1.3. Protocol Implementation Repository

4.1.4. Protocol Configuration Service

4.1.5. Protocol Configuration Repository

4.1.6. DT Binding Service

4.1.7. Digital Thread Repository

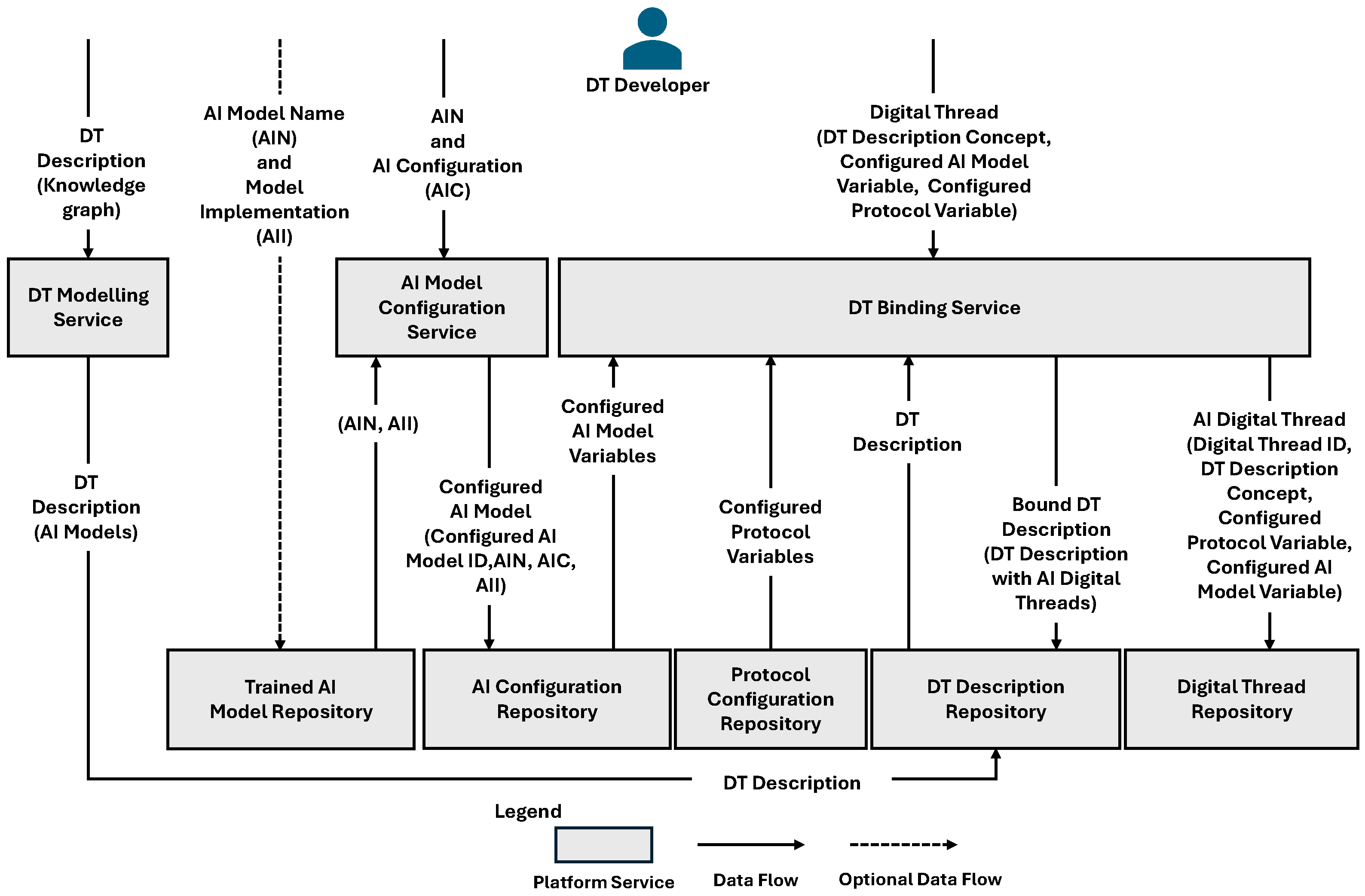

4.2. Digital Manufacturing Platform Supports AI Representation, Integration, and Interaction in DTs

4.2.1. Trained AI Model Repository

4.2.2. AI Model Configuration Service

4.2.3. AI Configuration Repository

4.2.4. DT Binding Service

4.2.5. Digital Thread Repository

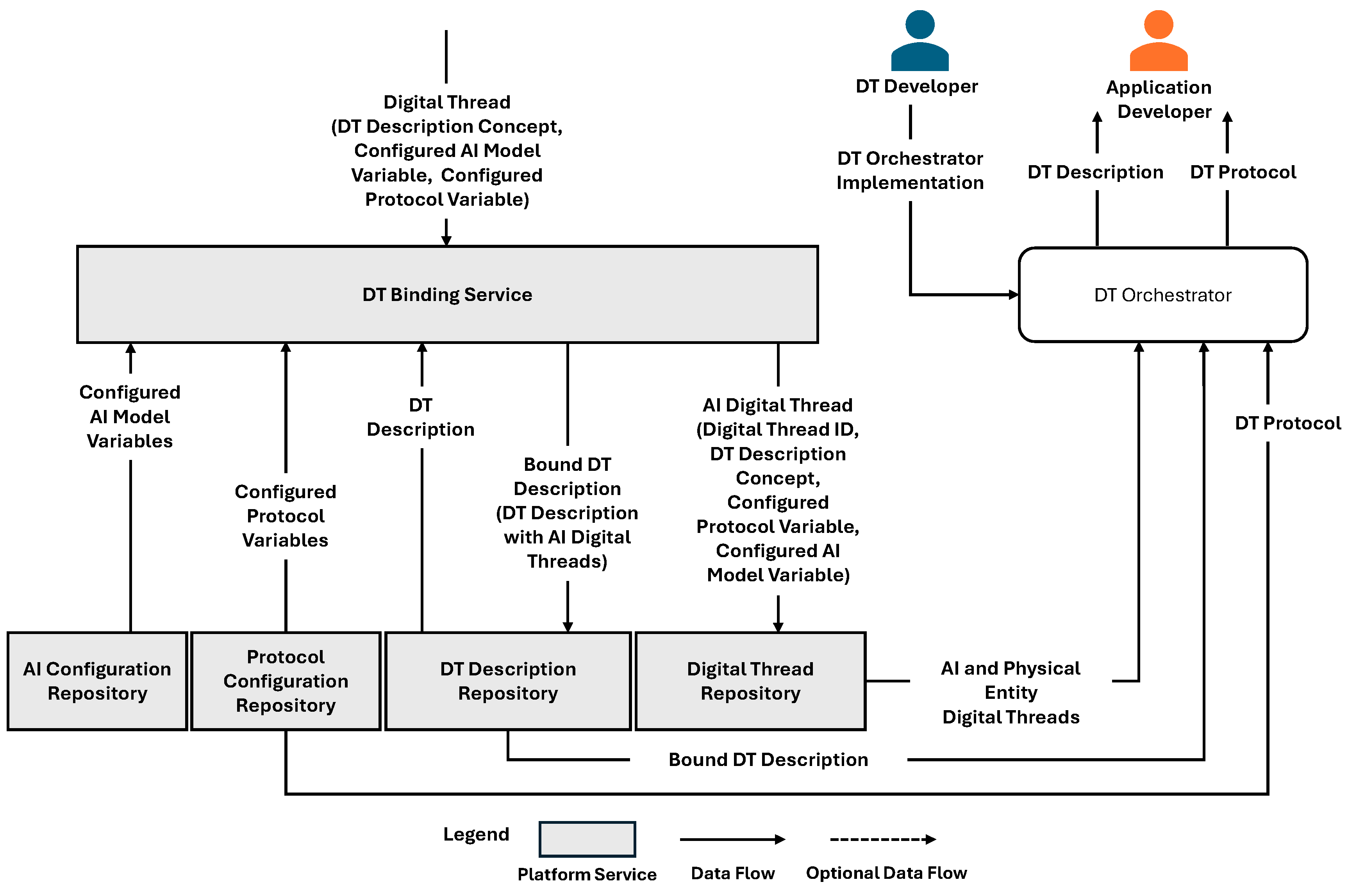

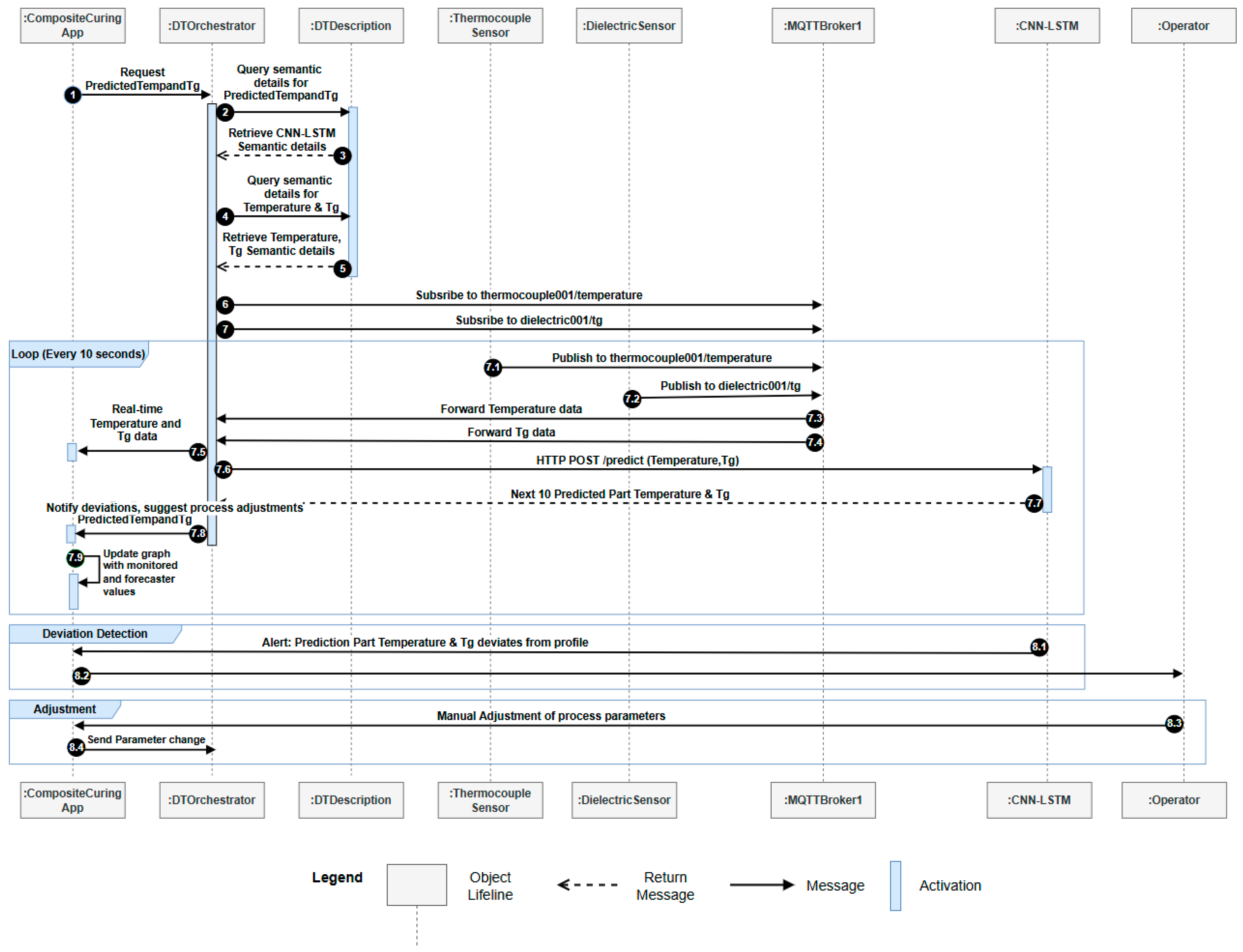

4.3. Digital Manufacturing Platform Supports DT Orchestration and Incorporation in Digital Manufacturing Applications

Instantiation of the Digital Twin

4.4. Scalability and Extensibility of the Digital Manufacturing Platform

4.5. Limitations of the Digital Manufacturing Platform

5. Proof-of-Concept Implementation of the Digital Manufacturing Platform

5.1. Implementation Environment and Experimental Setup

- Web Server Instance (8 GB RAM, 4 vCPU, 30 GB disk): Hosts four Docker containers via Docker Compose v5.0.1, comprising WebProtege v3.0.0 (https://hub.docker.com/r/protegeproject/webprotege (accessed on 15 September 2025)) for DT modelling and three Flask 3.0.3 microservices [83,84]:

- protocol-config-service:1.0: GET/protocols/{PN} and POST/configure (use protocol_config schema)

- ai-config-service:1.0: GET/models/{AN} and POST/configure (use ai_config schema)

- dt-binding-service:1.0: POST/digitalthreads → digital_threads schema

- Orchestrator VM Instance(s) (4 GB RAM, 2 vCPU, 30 GB disk): One dedicated instance per digital twin hosting dt-orchestrator-{dtId}:1.0 (FastAPI v0.128.0, port 80) serving DT-specific web UI and REST API with auto-generated OpenAPI/Swagger documentation.

- DT Description Instance (4 GB RAM, 2 vCPU, 30 GB disk): Deploys Apache Jena Fuseki 5.6.0 Docker container as RDF triple store using https://jena.apache.org/download/ (accessed on 22 January 2026).

- Data Repository Instance (4 GB RAM, 2 vCPU, 30 GB disk): Deploys PostgreSQL v15.4 database dm_platform_db (postgres:v15.4; port 5432) with three repository schemas and Gitea 1.25.4 (https://docs.gitea.com/installation/install-with-docker (accessed on 10 January 2026)):

- PostgreSQL Schemas (dm_platform_db): The database contains three schemas. The protocol_config schema stores configured protocol, including configured_protocol_id, protocol_name, protocol_configuration (JSON), protocol_impl (Gitea ref). The ai_config schema stores configured AI model including configured_ai_model_id, ai_model_name, ai_model_configuration (JSON), ai_model_impl (Gitea ref). The digital_threads schema captures type (physical/ai), digital_thread_id, dt_concept (RDF URI), configured_protocol_id, configured_ai_model_id.

- Gitea hosts Repositories for Protocol implementations include mqtt_client.py, and Trained AI models includes cnn-lstm_temppredict:v1.0.

5.2. Implementation Challenges and Solutions

- Semantic Query Performance: Initial SPARQL queries over 50 K RDF triples exceeded 2 s latency. Apache Jena Fuseki 5.6.0 with TDB2 backend and query caching reduced response times to 38 ms, enabling real-time DT binding.

- Multi-Protocol Blocking: Concurrent MQTT, OPC UA, and HTTP streams caused blocking under high-frequency data. Python asyncio v3.11 with Digital Thread abstraction enabled non-blocking, concurrent protocol execution while maintaining semantic mappings.

- AI Model Reproducibility: Versioning risks across DT lifecycles. Git tagging + Docker image pinning (e.g., cnn-lstm-temppredict:v1.0) ensured reproducible inference and rollback capability.

- Container Orchestration: Startup ordering failures. Docker Compose v2.20.1 health checks and explicit depends on constraints achieved stable deployment sequencing.

- Network Latency: Nectar Cloud cross-instance communication. Internal Docker networking + PostgreSQL v15.4 connection pooling reduced orchestration latency to <5 ms.

- Repository Management: Plain Git lacked web access and authentication for protocol implementation code (e.g., mqtt_client.py) and trained AI model artifacts (e.g., cnn-lstm_temppredict:v1.0). Gitea 1.25.4 provided HTTP/SSH access, web UI, and authentication enabling scalable management across multiple digital twins.

5.3. Explicit Mapping Between the Proposed Framework and the Platform Implementation

6. Functional Assessment of Digital Manufacturing Platform Support Developing Different Digital Manufacturing Applications Using Digital Twins

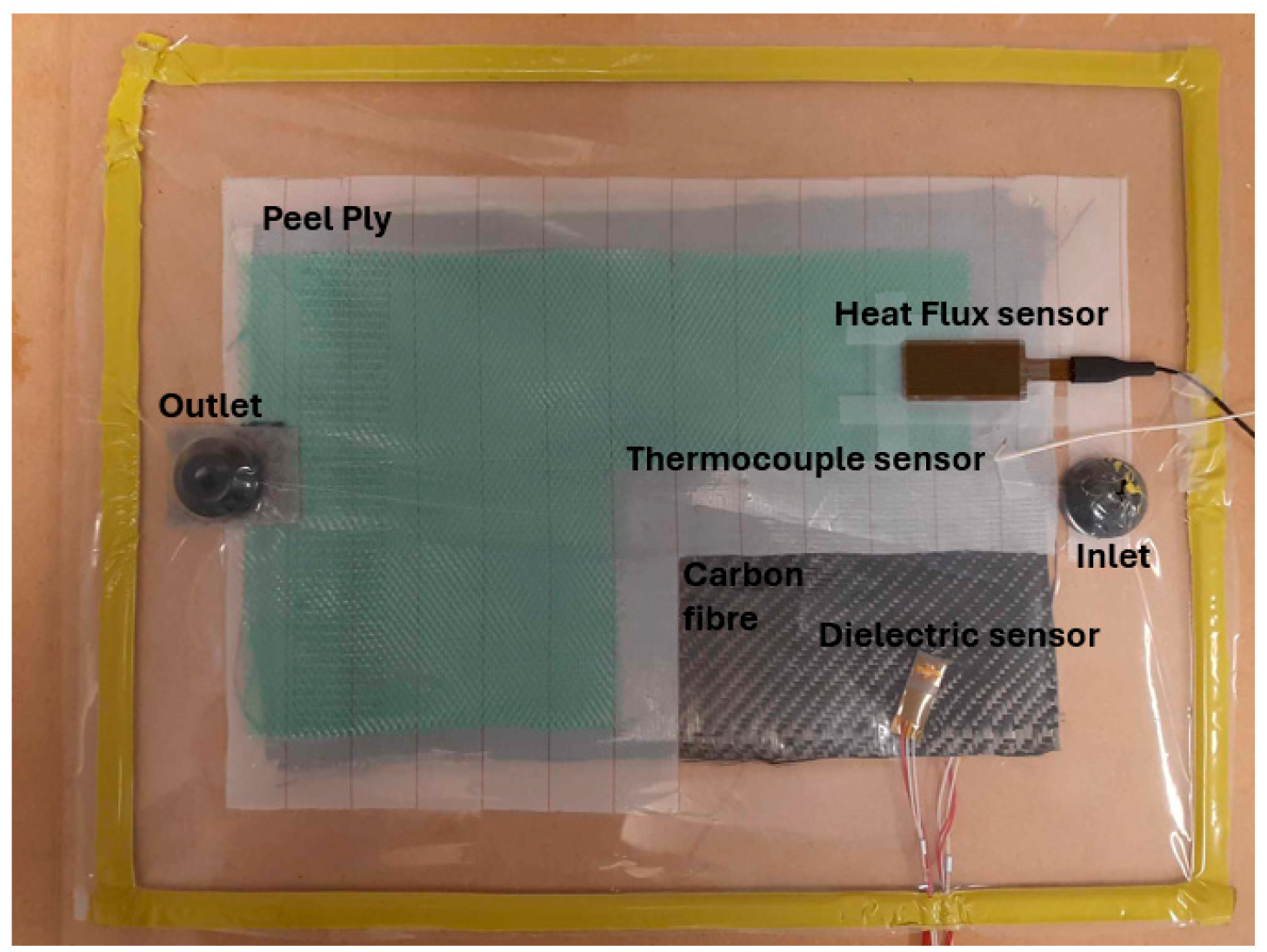

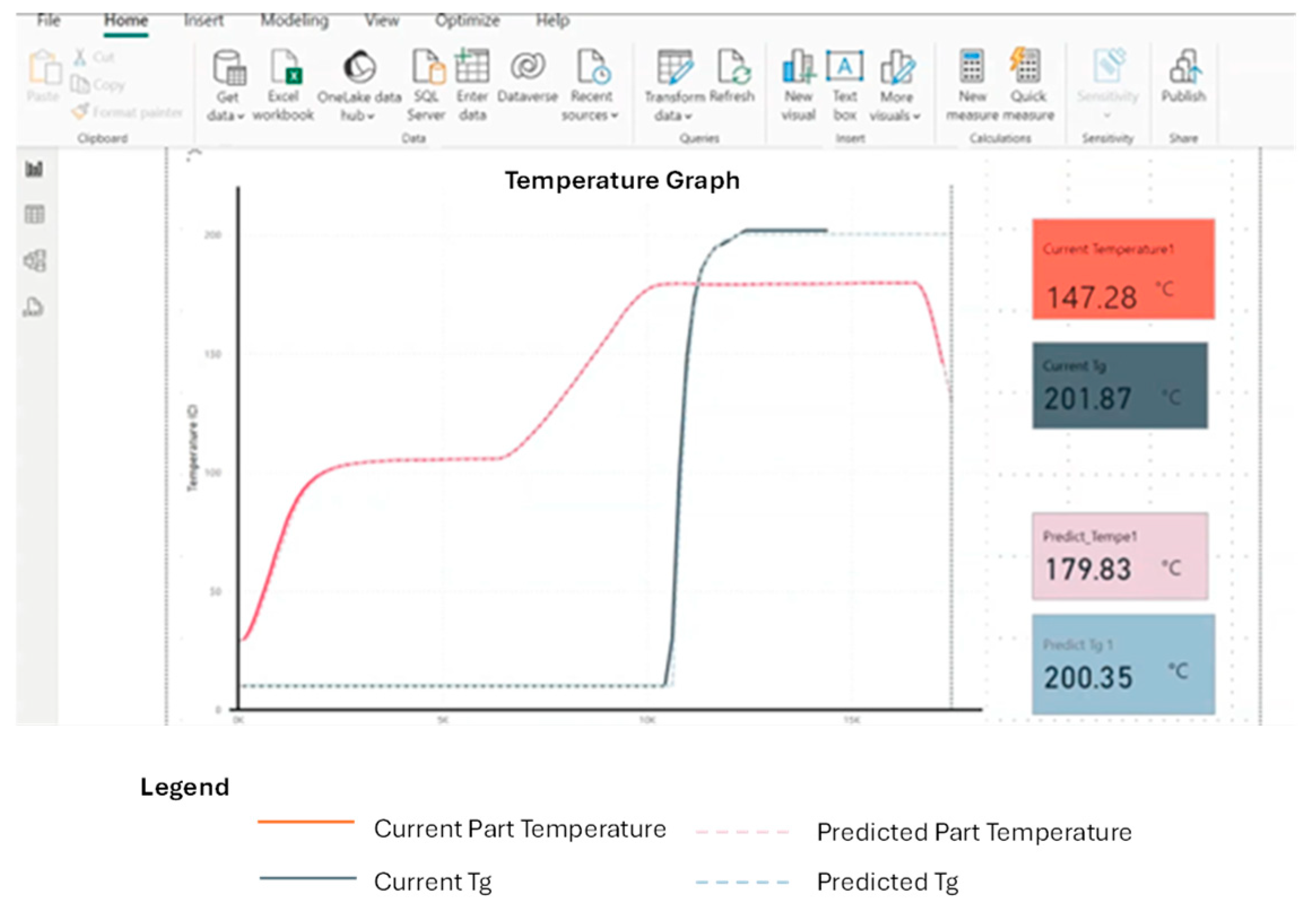

6.1. Composite Curing Application Use Digital Twin of Composite Airframe Part to Improve Product Quality

6.1.1. Digital Twin of Composite Airframe Part

- Physical twin

- 2.

- Virtual twin

- Physical Entity Representation

- AI Representation

- 3.

- Digital Threads

6.1.2. Development of Composite Curing Application to Improve Product Quality

- Physical Entity: dth_001 (temperature), dth_002 (Tg), dth_003 (interpolation)

- AI Digital Thread: CNN-LSTM (Model_001) 10-ahead forecasting

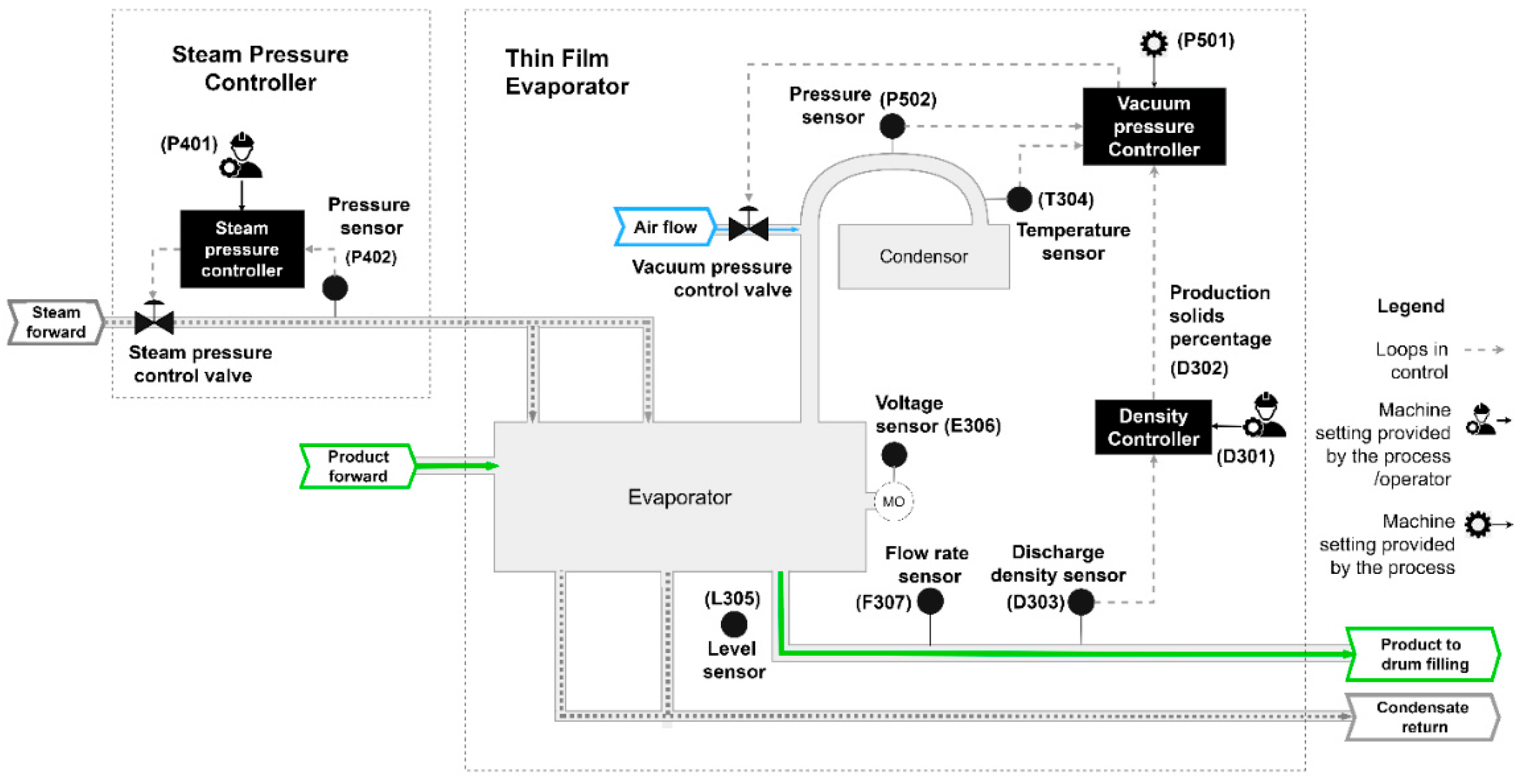

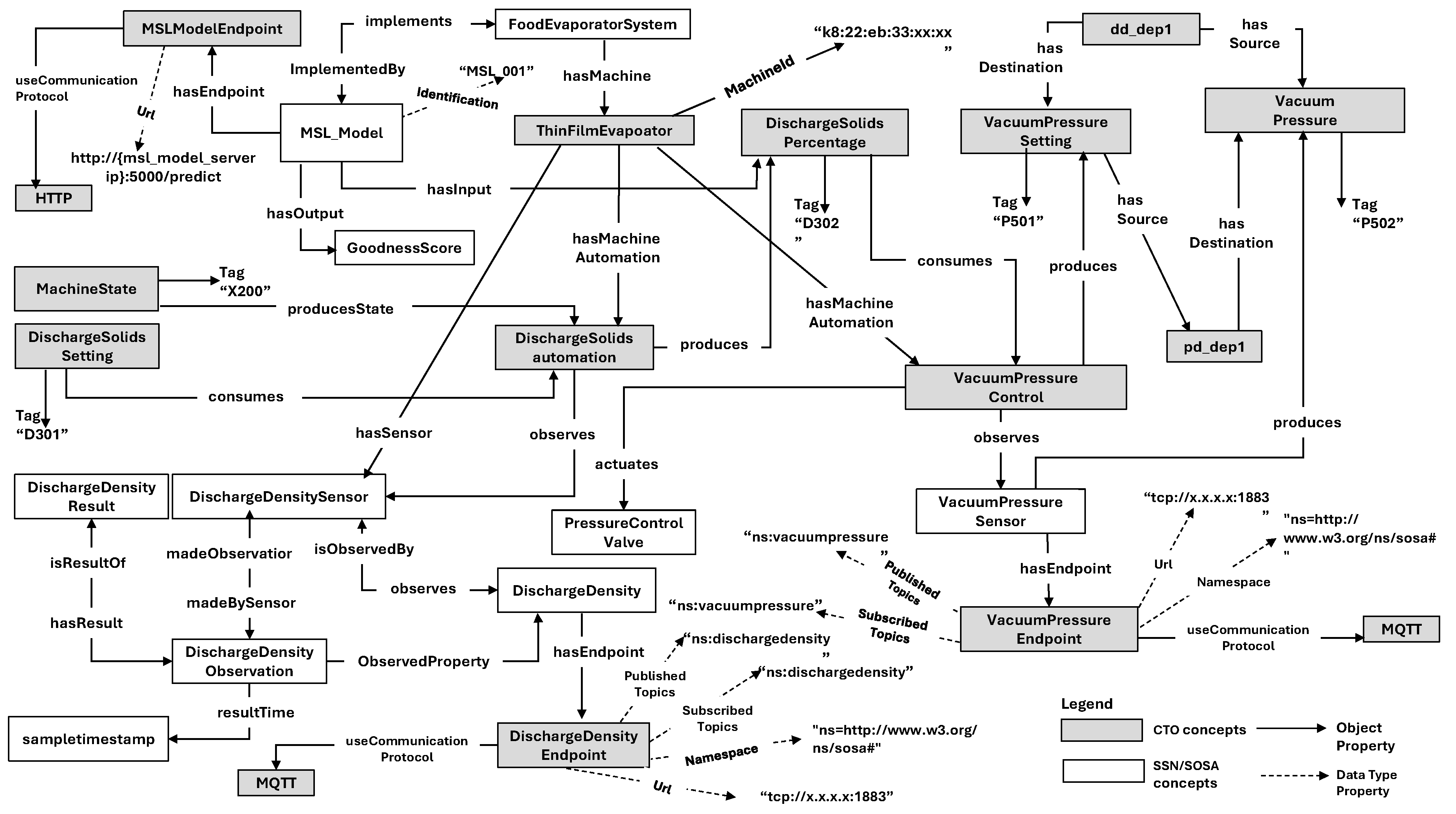

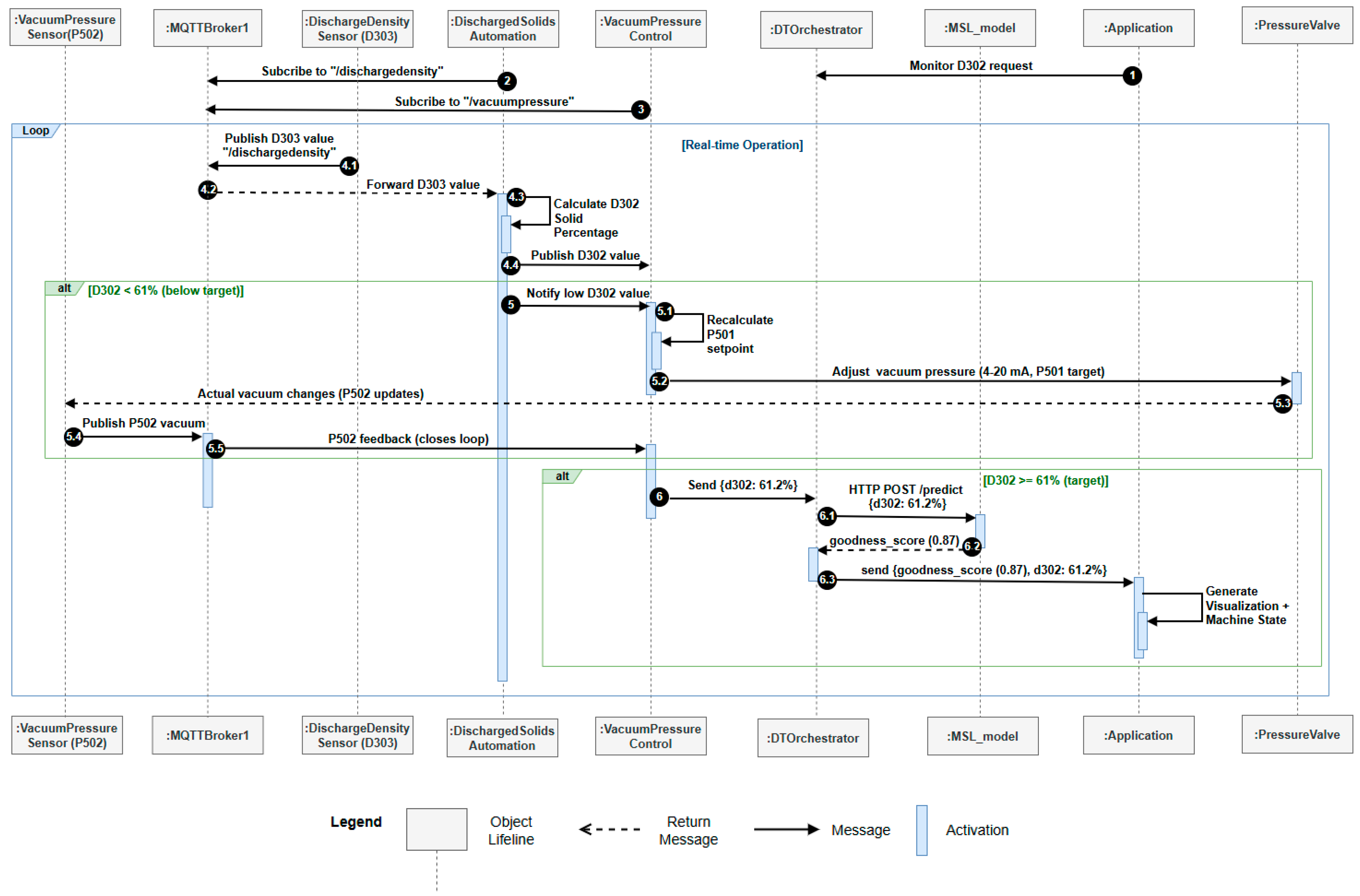

6.2. Product Quality Improvement Application Using a Digital Twin of a TFE Machine for Improving Product Quality

6.2.1. Digital Twin of TFE Machine

- 4.

- Physical Twin

- 5.

- Virtual Twin

- Physical Entity Representation

- AI Representation

- 6.

- Digital Threads

6.2.2. Development of Product Quality Improvement for Food Manufacturing

- Physical Entity: mqtt_004 (D303 → D302), mqtt_005 (P501 ↔ P502)

- AI Digital Thread: http_003/model_003 (MSL inference)

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DT | Digital Twin |

| DM | Digital Manufacturing |

| CTM | Cyber Twin Machine |

| IoT | Internet Of Things |

| IIoT | Industrial Internet of Things |

| RDF | Resource Description Framework |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

References

- Georgakopoulos, D.; Jayaraman, P.P. Digital twins and dependency/constraint-aware AI for digital manufacturing. Commun. ACM 2023, 66, 87–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Shen, W.; Wang, X. The Internet of Things in manufacturing: Key issues and potential applications. IEEE Syst. Man Cybern. Mag. 2018, 4, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreekumar, M.D.; Chhabra, M.; Yadav, R. Productivity in manufacturing industries. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. Technol. 2018, 3, 634–639. [Google Scholar]

- Sverko, M.; Grbac, T.G.; Mikuc, M. SCADA Systems With Focus on Continuous Manufacturing and Steel Industry: A Survey on Architectures, Standards, Challenges and Industry 5.0. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 109395–109430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khedher, A.; Henry, S.; Bouras. Integration between MES and product lifecycle management. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference Emerging Technologies and Factory Automation (ETFA), Toulouse, France, 5–9 September 2011; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarov, V.V.; Frolov, Y.B.; Parshina, I.S.; Ushakova, M.V. MES Systems as an Integral Part of Digital Production. In Proceedings of the 2020 13th International Conference Management of large-scale system development (MLSD), Moscow, Russia, 28–30 September 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamunuarachchi, D.; Georgakopoulos, D.; Banerjee, A.; Jayaraman, P.P. Digital twins supporting efficient digital industrial transformation. Sensors 2021, 21, 6829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, A.; Forkan, A.; Georgakopoulos, D.; Milovac, J.; Jayaraman, P.P. An IIoT Machine Model for Achieving Consistency in Product Quality in Manufacturing Plants. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2109.12964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, B.X.; Gunaratne, M.; Ravandi, M.; Wang, J.; Dharmawickrema, T.; Di Pietro, A.; Jin, J.; Georgakopoulos, D. Smart industrial Internet of Things framework for composites manufacturing. Sensors 2024, 24, 4852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, B.X.; Gunaratne, M.; Wang, J.; Muzaffar, C.; Ravandi, M.; Di Pietro, A. Revolutionizing Composites Manufacturing: A Closed-Loop IoT Framework for Industry 4.0. In AIAC 2025: 21st Australian International Aerospace Congress; Engineers Australia: Melbourne, Australia, 2025; pp. 304–309. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Schultz, M.; Cash, R.; Barrett, D.; McCarthy, M. Determination of Quality Parameters of Tomato Paste Using Guided Microwave Spectroscopy. Food Control 2014, 40, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Foundational Research Gaps and Future Directions for Digital Twins; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SiteWhere LLC. The Open Platform for the Internet of Things™. Available online: https://sitewhere.io/en/ (accessed on 15 June 2024).

- Microsoft. Azure IoT. Available online: https://azure.microsoft.com/en-us/overview/iot/ (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Cumulocity GmbH. Sensor Library–Cumulocity IoT Guides. Available online: https://cumulocity.com/guides/reference/sensor-library/ (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Insights Hub IoT. Available online: https://plm.sw.siemens.com/en-US/insights-hub/ (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Thelen, A.; Zhang, X.; Fink, O.; Lu, Y.; Ghosh, S.; Youn, B.D.; Todd, M.D.; Mahadevan, S.; Hu, C.; Hu, Z. A Comprehensive Review of Digital Twin—Part 1: Modeling and Twinning Enabling Technologies. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2022, 65, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Easwaran, A.; Andalam, S. Challenges in Digital Twin Development for Cyber-Physical Production Systems. In International Workshop on Design, Modeling, and Evaluation of Cyber Physical Systems; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 11615, pp. 28–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nti, I.K.; Adekoya, A.F.; Weyori, B.A.; Nyarko-Boateng, O. Applications of artificial intelligence in engineering and manufacturing: A systematic review. J. Intell. Manuf. 2022, 33, 1581–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.; Jeon, J.; Choi, D.; Park, J.-Y. Application of Machine Learning Techniques in Injection Molding Quality Prediction: Implications on Sustainable Manufacturing Industry. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.; Kim, M.; Nichols, E.; Yoon, H.-S. AI-Driven Digital Twins for Manufacturing: A Review Across Hierarchical Manufacturing System Levels. Sensors 2026, 26, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolbotinović, Ž.; Milić, S.D.; Janda, Ž.; Vukmirović, D. AI-powered digital twin in the industrial IoT. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2025, 167, 110656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafto, M.; Conroy, M.; Doyle, R.; Glaessgen, E.; Kemp, C.; LeMoigne, J.; Wang, L. Modeling, Simulation, Information Technology and Processing Roadmap. Natl. Aeronaut. Space Adm. 2010, 11, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Grieves, M.W. Product Lifecycle Management: The New Paradigm for Enterprises. Int. J. Prod. Dev. 2005, 2, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, R.; Von Wichert, G.; Lo, G.; Bettenhausen, K.D. About the importance of autonomy and digital twins for the future of manufacturing. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2015, 48, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.; Snider, C.; Nassehi, A.; Yon, J.; Hicks, B. Characterising the Digital Twin: A systematic literature review. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2020, 29, 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlemann, T.H.; Lehmann, C.; Steinhilper, R. The digital twin: Realizing the cyber-physical production system for industry 4.0. Procedia CIRP 2017, 61, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borchert, S.; Rosen, R. Mechatronic Futures: Digital Twin—The Simulation Aspect; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladj, A.; Wang, Z.; Meski, O.; Belkadi, F.; Ritou, M.; Da Cunha, C. A knowledge-based Digital Shadow for machining industry in a Digital Twin perspective. J. Manuf. Syst. 2021, 58, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthelmey, A.; Lee, E.; Hana, R.; Deuse, J. Dynamic digital twin for predictive maintenance in flexible production systems. In Proceedings of the IECON 2019—45th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Lisbon, Portugal, 14–17 October 2019; pp. 4209–4214. [Google Scholar]

- Negri, E.; Fumagalli, L.; Macchi, M. A review of the roles of digital twin in CPS-based production systems. Procedia Manuf. 2017, 11, 939–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franciosa, P.; Sokolov, M.; Sinha, S.; Sun, T.; Ceglarek, D. Deep learning enhanced digital twin for closed-loop in-process quality improvement. CIRP Ann. 2020, 69, 369–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavropoulos, P.; Sabatakakis, K. Quality Assurance in Resistance Spot Welding: State of Practice, State of the Art, and Prospects. Metals 2024, 14, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocklisch, F.; Huchler, N. Humans and cyber-physical systems as teammates? Characteristics and applicability of the human-machine-teaming concept in intelligent manufacturing. Front. Artif. Intell. 2023, 6, 1247755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horr, A.M.; Drexler, H. Real-Time Models for Manufacturing Processes: How to Build Predictive Reduced Models. Processes 2025, 13, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, E.; Lazarro, O.; Sepulcre, M.; Gozalvez, J.; Passarella, A.; Raptis, T.; Ude, A.; Nemec, B.; Rooker, M.; Kirstein, F. The AUTOWARE Framework and Requirements for the Cognitive Digital Automation. In Proceedings of the IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology, Vicenza, Italy, 18–20 September 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gašpar, T.; Deniša, M.; Ude, A. A reconfigurable robot workcell for quick set-up of assembly processes. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.00865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamunuarachchi, D.; Banerjee, A.; Jayaraman, P.P.; Georgakopoulos, D. Cyber Twins Supporting Industry 4.0 Application Development. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Advances in Mobile Computing & Multimedia, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 30 November–2 December 2020; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 64–73. [Google Scholar]

- Rasheed, A.; San, O.; Kvamsdal, T. Digital Twin: Values, Challenges and Enablers From a Modeling Perspective. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 21980–22012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, A. Post-Processing and Visualization Techniques for Isogeometric Analysis Results. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2017, 316, 880–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasak, H.; Jemcov, A.; Tukovic, Z. OpenFOAM: A C++ Library for Complex Physics Simulations. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Coupled Methods in Numerical Dynamics IUC, Dubrovnik, Croatia, 19–21 September 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Perzylo, A.; Somani, N.; Rickert, M.; Knoll, A. An Ontology for CAD Data and Geometric Constraints as a Link Between Product Models and Semantic Robot Task Descriptions. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Hamburg, Germany, 28 September–2 October 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pk, R.; Manikandan, N.; Ramshankar, C.S.; Vishwanathan, T.; Sathishkumar, C. Digital Twin of an Automotive Brake Pad for Predictive Maintenance. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2019, 165, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, M.; Stjepandic, J.; Stobrawa, S.; von Soden, M. Automatic Generation of Digital Twin Based on Scanning and Object Recognition. In Proceedings of the 6th ISPE International Conference on Transdisciplinary Engineering, Tokyo, Japan, 30 July–1 August 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousi, N.; Gkournelos, C.; Aivaliotis, S.; Giannoulis, C.; Michalos, G.; Makris, S. Digital Twin for Adaptation of Robots’ Behavior in Flexible Robotic Assembly Lines, Procedia Manufacturing. Prod. Manuf. Res. 2019, 28, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semantic Sensor Network Ontology. Available online: https://www.w3.org/TR/vocab-ssn/ (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Mourtzis, D.; Papakostas, N.; Mavrikios, D.; Makris, S.; Alexopoulos, K. The role of simulation in digital manufacturing: Applications and outlook. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manufact. 2015, 28, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, C. Advancements and challenges of digital twins in industry. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2024, 4, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Fang, F.; Yan, N.; Wu, Y. State of the art in defect detection based on machine vision. Int. J. Prec. Eng. Manuf. Green Technol. 2022, 9, 661–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achouch, M.; Dimitrova, M.; Ziane, K.; Sattarpanah Karganroudi, S.; Dhouib, R.; Ibrahim, H.; Adda, M. On Predictive Maintenance in Industry 4.0: Overview, Models, and Challenges. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera Vidal, G.; Coronado Hernández, J.R. Complexity in manufacturing systems: A literature review. Prod. Eng. 2021, 15, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montori, F.; Liao, K.; Jayaraman, P.P.; Bononi, L.; Sellis, T.; Georgakopoulos, D. Classification and Annotation of Open Internet of Things Datastreams. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Web Information Systems Engineering, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 12–15 November 2018; pp. 209–224. [Google Scholar]

- Madithiyagasthenna, D.; Jayaraman, P.P.; Morshed, A.; Forkan, A.R.M.; Georgakopoulos, D.; Kang, Y.B.; Piechowski, M. A solution for annotating sensor data streams—An industrial use case in building management system. In Proceedings of the 2020 21st IEEE International Conference on Mobile Data Management (MDM), Versailles, France, 30 June–3 July 2020; pp. 194–201. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, I.; Park, S.J. HealthSOS: Real-Time Health Monitoring System for Stroke Prognostics. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 213574–213586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, I.; Park, S.J. Big-ECG: Cardiographic Predictive Cyber-Physical System for Stroke Management. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 123146–123164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawod, A.; Georgakopoulos, D.; Jayaraman, P.P.; Nirmalathas, A. An IoT-owned Service for Global IoT Device Discovery, Integration and (Re)use. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Services Computing (SCC), Beijing, China, 7–11 November 2020; pp. 312–320. [Google Scholar]

- Soldatos, J.; Kefalakis, N.; Hauswirth, M.; Serrano, M.; Calbimonte, J.-P.; Riahi, M.; Aberer, K.; Jayaraman, P.P.; Zaslavsky, A.; Žarko, I.P. OpenIoT: Open Source Internet–of–Things in the Cloud. In Proceedings of the Interoperability and Open-Source Solutions for the Internet of Things, Split, Croatia, 18 September 2014; pp. 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Compton, M.; Barnaghi, P.; Bermudez, L.; García-Castro, R.; Corcho, O.; Cox, S.; Graybeal, J.; Hauswirth, M.; Henson, C.; Herzog, A. The SSN ontology of the W3C semantic sensor network incubator group. J. Web Semant. 2012, 17, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, S.K.; Bonnet, C. Easing IoT application development through DataTweet framework. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 3rd World Forum on Internet of Things (WF-IoT), Reston, VA, USA, 12–14 December 2016; pp. 430–435. [Google Scholar]

- Cirillo, F.; Solmaz, G.; Berz, E.L.; Bauer, M.; Cheng, B.; Kovacs, E. A Standard-based Open Source IoT Platform: FIWARE. IEEE Internet Things Mag. 2020, 3, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FIWARE Foundation. Smart Data Models. Available online: https://www.fiware.org/developers/smart-data-models/ (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Hlayel, M.; Mahdin, H.; Adam, H.A.M. Latency Analysis of WebSocket and Industrial Protocols in Real-Time Digital Twin Integration. Int. J. Eng. Trends Technol. (IJETT) 2025, 73, 120–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Qi, Q.; Wang, L.; Nee, A. Digital Twins and Cyber–Physical Systems toward Smart Manufacturing and Industry 4.0: Correlation and Comparison. Engineering 2019, 5, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Lechevalier, D. Standards Based Generation of a Virtual Factory Model. In Proceedings of the 2016 Winter Simulation Conference (WSC), Washington, DC, USA, 11–14 December 2016; pp. 2762–2773. [Google Scholar]

- Klar, R.; Arvidsson, N.; Angelakis, V. Digital twins’ maturity: The need for interoperability. IEEE Syst. J. 2023, 18, 713–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amjad, A.; Azam, F.; Anwar, M.W.; Butt, W.H. A Systematic Review on the Data Interoperability of Application Layer Protocols in Industrial IoT. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 96528–96545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, L.P.; Cat, T.N.; Nam, D.T.; Van Trong, N.; Le, T.N.; Pham-Quoc, C. OPC-UA/MQTT-Based Multi M2M Protocol Architecture for Digital Twin Systems. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligence of Things, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 25–27 October 2023; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 187, pp. 322–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, L.; Sobowale, A.; Lima, A.; Marujo, P.; Machado, J. OPC-UA in Digital Twins—A Performance Comparative Analysis. In International Conference Innovation in Engineering; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Yao, Z.; Verbeke, M.; Karsmakers, P.; Gorissen, B.; Reynaerts, D. Data-driven models with physical interpretability for real-time cavity profile prediction in electrochemical machining processes. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 160, 111807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kausar, M.A. Digital Twin-Enabled Anomaly Detection for Industrial IoT using Explainable AI. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2025, 187, 975–8887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.R.; McCarthy, I.P. Product recovery decisions within the context of extended producer responsibility. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2013, 34, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miehe, R.; Waltersmann, L.; Sauer, A.; Bauernhansl, T. Sustainable production and the role of digital twins–basic reflections and perspectives. J. Adv. Manuf. Process 2021, 3, e10078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soori, M.; Arezoo, B.; Habibi, M. Accuracy analysis of tool deflection error modelling in prediction of milled surfaces by a virtual machining system. Int. J. Comput. Appl. Technol. 2017, 55, 308–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soori, M.; Asmael, M. Virtual minimization of residual stress and deflection error in five-axis milling of turbine blades. Strojniski Vestnik/J. Mech. Eng. 2021, 67, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soori, M.; Arezoo, B.; Dastres, R. Machine learning and artificial intelligence in CNC machine tools, a review. Sustain. Manuf. Serv. Econ. 2023, 2, 100009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soori, M. Advanced composite materials and structures. J. Mater. Eng. Struct. 2023, 10, 249–272. [Google Scholar]

- Humfeld, K.D.; Gu, D.; Butler, G.A.; Nelson, K.; Zobeiry, N. A machine learning framework for real-time inverse modeling and multi-objective process optimization of composites for active manufacturing control. Compos. Part. B Eng. 2021, 223, 109150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dastres, R.; Soori, M. Artificial neural network systems. Int. J. Imaging Robot. (IJIR) 2021, 21, 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Xu, B.; Wood, J. Predict failures in production lines: A two-stage approach with clustering and supervised learning. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), Washington, DC, USA, 5–8 December 2016; pp. 2070–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Fizza, K.; Georgakopoulos, D.; Forkan, A.R.M.; Jayaraman, P.P.; Milovac, J.K. Improving the High-Quality Product Consistency in a Digital Manufacturing Environment. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2025, 21, 623–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastering API Orchestration: A Hands-On Guide. Available online: https://medium.com/tech-learnings/mastering-api-orchestration-a-hands-on-guide-f0bee5cb5aaa (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- API Orchestration: Combining Services. Available online: https://api7.ai/learning-center/api-101/api-orchestration-combining-services (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Flask Web Development. Available online: https://flask.palletsprojects.com/en/stable/ (accessed on 22 January 2026).

- Grinberg, M. Flask Web Development: Developing Web Applications with Python, 2nd ed.; O’Reilly Media, Inc.: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2014; Volume 95472, ISBN 978-1-4493-7262-0. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, B.X.; Eisenbart, B.; Nikzad, M.; Fox, B.; Blythe, A.; Blanchard, P.; Dahl, J. A novel heuristic optimisation framework for radial injection configuration for the resin transfer moulding process. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2023, 165, 107352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, B.X.; Eisenbart, B.; Nikzad, M.; Fox, B.; Wang, Y.; Bwar, K.H.; Zhang, K. Review of Approaches to Minimise the Cost of Simulation-Based Optimisation for Liquid Composite Moulding Processes. Materials 2023, 16, 7580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bamunuarachchi, D. Next Generation Industrial Internet of Providing Effcient Cyber Twins-Based Realization of Industry 4.0; Swinburne University of Technology: Hawthorn, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

| Repository | ID | PN or AIN | PC or AIC | PI or AII |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protocol Configuration (protocol_config) | mqtt_001 | MQTT | {broker:“tcp://x.x.x.x:1883”, topic:“/thermocouplesensor001/temperature”, qos:1} | http://x.x.x.x:3000/repo/mqtt.git |

| mqtt_002 | MQTT | {broker:“tcp://x.x.x.x:1883”, topic:“/dielectricsensor001/resistance”, qos:1} | http://x.x.x.x:3000/repo/mqtt.git | |

| http_001 | HTTP | {base_url:“http://x.x.x.x:8080/v1/models/temperature-prediction/”, method:“POST”} | http://x.x.x.x:3000/repo/http.git | |

| opcua_001 | OPC UA | {url:“opc.tcp://x.x.x.x:4840/”,security_mode:“None”, node_id:“ns=2;i=1001”, subscription_interval:500} | http://x.x.x.x:3000/repo/opcua.git | |

| AI Configuration (ai_config) | model_001 | CNN-LSTM | {output:“PredictedTempandTg”, input:“Temperature,Tg”} | http://x.x.x.x:3000/repo/cnn-lstm_temppredict.git |

| model_002 | MLP | {output:“Viscosity”, input:“Resistance”} | http://x.x.x.x:3000/repo/mlp_viscopredict.git |

| Type | Digital Thread ID | DT Concept | Configured Protocol Id | Configured AI Model Id |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical | dth_001 | Temperature | mqtt_001 | NULL |

| Physical | dth_002 | Resistance | mqtt_002 | NULL |

| AI | dth_003 | PredictedTempandTg | http_001 | model_001 |

| AI | dth_003 | Viscosity | http_002 | model_002 |

| Repository | ID | PN or AIN | PC or AIC | PI or AII |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protocol Configuration (protocol_config) | mqtt_004 | MQTT | {broker:“tcp://x.x.x.x:1883”, topic:“dischargedensity”, qos:1} | http://x.x.x.x:3000/repo/mqtt.git |

| mqtt_005 | MQTT | {broker:“tcp://x.x.x.x:1883”, topic:“vacuumpressure”, qos:1} | http://x.x.x.x:3000/repo/mqtt.git | |

| http_003 | HTTP | {base_url:“http://{msl_model_server_ip}:5000/predict/”, method:“POST”} | http://x.x.x.x:3000/repo/http.git | |

| opcua_002 | OPC UA | {url:“opc.tcp://x.x.x.x:5001/”, security_mode:“None”, node_id:“ns=2;i=1001”, subscription_interval:500} | http://x.x.x.x:3000/repo/opcua.git | |

| AI Configuration (ai_config) | model_003 | MSL | {output:“goodnessscore“, input:“DischargeSolidsPercentage”} | http://x.x.x.x:3000/repo/msl_001.git |

| Type | Digital Thread ID | DT Concept | Configured Protocol Id | Configured AI Model Id |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical | dth_004 | DischargeDensity | mqtt_004 | NULL |

| Physical | dth_005 | VacuumPressure | mqtt_005 | NULL |

| AI | dth_006 | GoodnessScore | http_003 | model_003 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gunaratne, M.; Georgakopoulos, D.; Banerjee, A. A Digital Twins Platform for Digital Manufacturing. Electronics 2026, 15, 583. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15030583

Gunaratne M, Georgakopoulos D, Banerjee A. A Digital Twins Platform for Digital Manufacturing. Electronics. 2026; 15(3):583. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15030583

Chicago/Turabian StyleGunaratne, Maheshi, Dimitrios Georgakopoulos, and Abhik Banerjee. 2026. "A Digital Twins Platform for Digital Manufacturing" Electronics 15, no. 3: 583. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15030583

APA StyleGunaratne, M., Georgakopoulos, D., & Banerjee, A. (2026). A Digital Twins Platform for Digital Manufacturing. Electronics, 15(3), 583. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15030583