Image–Text Sentiment Analysis Based on Dual-Path Interaction Network with Multi-Level Consistency Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

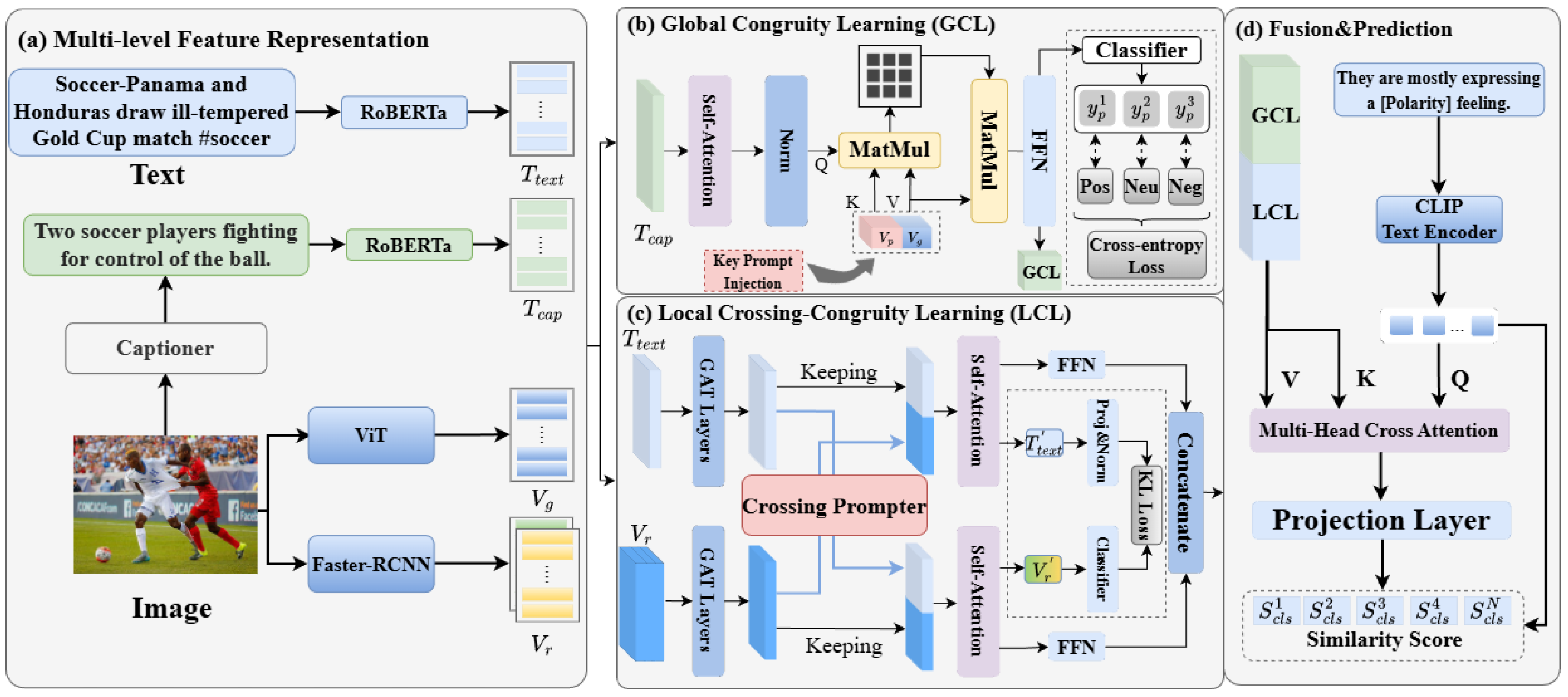

- We construct a multi-level feature representation module that establishes a multi-dimensional, multi-granularity representation space through four path parallel feature extraction. This approach of separating global and local features avoids the loss of emotional cues often observed in traditional feature concatenation methods.

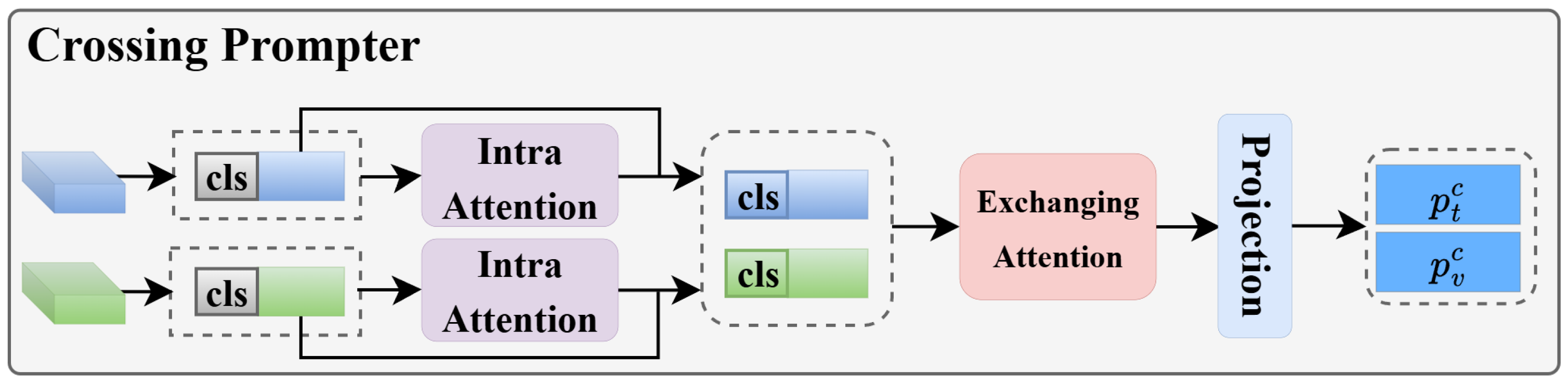

- We propose a complementary consistency learning framework GCL and LCL. The GCL module implements adaptive filtering of cross-modal global correlations through a collaborative mechanism combining multi-head cross-attention and self-attention gating. Dynamically generated Key Prompts guide the network to focus on semantically salient global regions across modalities. The LCL module introduces an innovative Crossing Prompter, which is specifically designed to enhance fine-grained local feature interactions and is integrated with a Graph Attention Network (GAT), constructing a fine-grained local feature interaction system.

- Furthermore, we perform contrastive learning between the concatenated feature vector of GCL and LCL and the text embeddings generated by the CLIP text encoder, which incorporate sentiment polarity. By contrasting the similarity with texts of different polarities, we achieve sentiment classification decisions. We conducted a series of validation experiments on the aforementioned dataset, which verified the effectiveness of the approach adopted in this paper.

2. Related Work

2.1. Multimodal Fusion

2.2. Image–Text Sentiment Analysis

3. Method

3.1. Overview

3.2. Model Design

3.3. Multi-Level Feature Representation

3.4. Multi-Level Consistency Learning Model

3.5. Fusion & Prediction

| Algorithm 1 DINMCL |

| Require: Training datasets M, sentiment label L, text T, image I, Ensure: Sentiment prediction results

|

4. Experiment

4.1. Dataset

4.2. Experimental Setup

4.3. Baselines

4.4. Comparison Experiments

4.5. Ablation Experiments

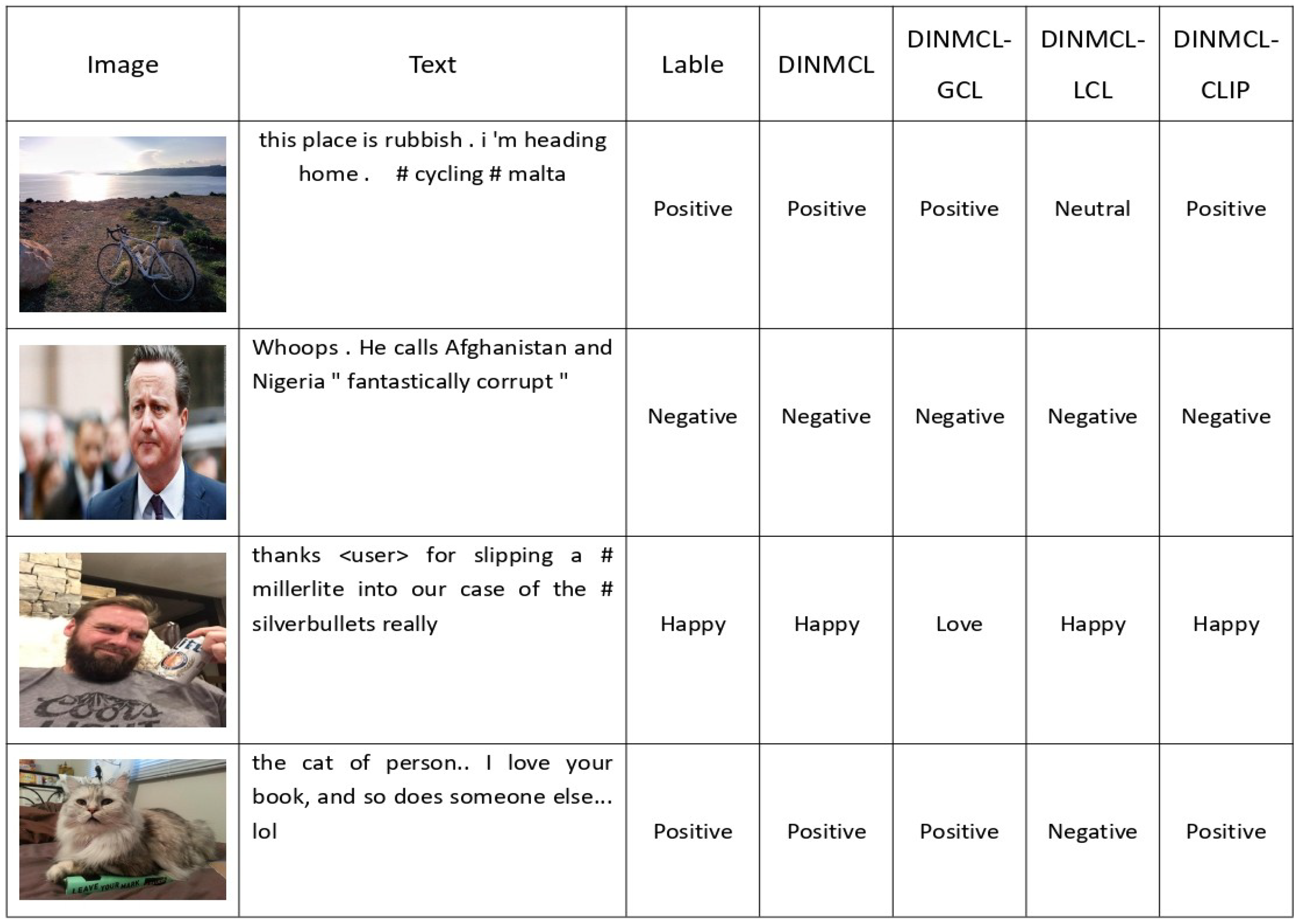

4.6. Case Study

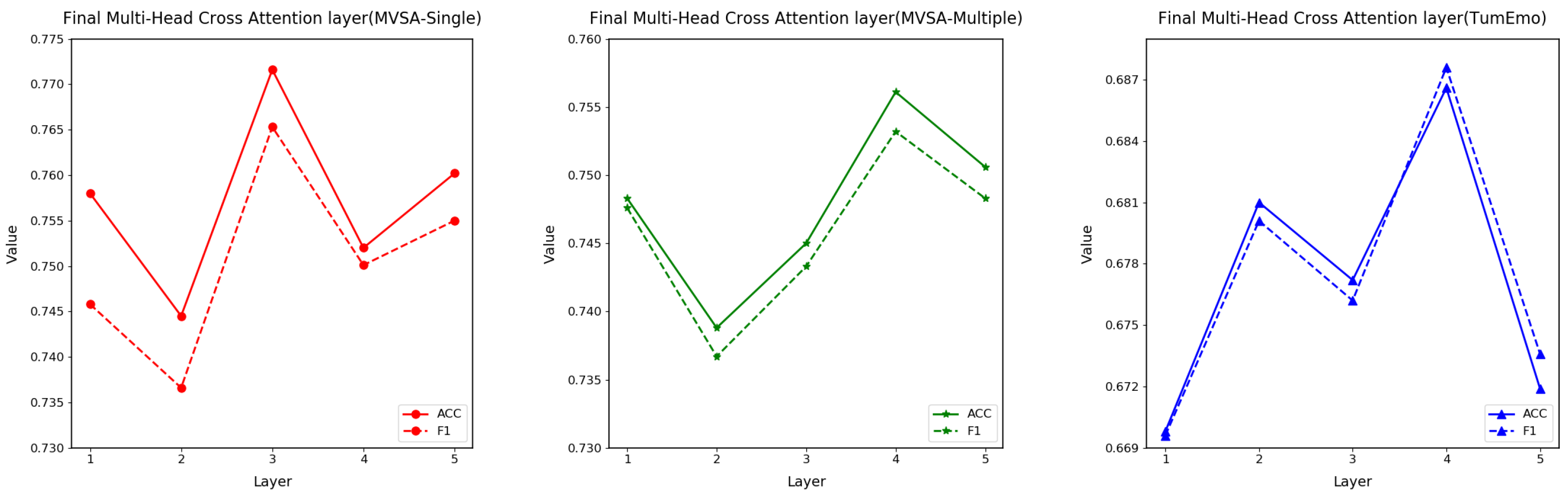

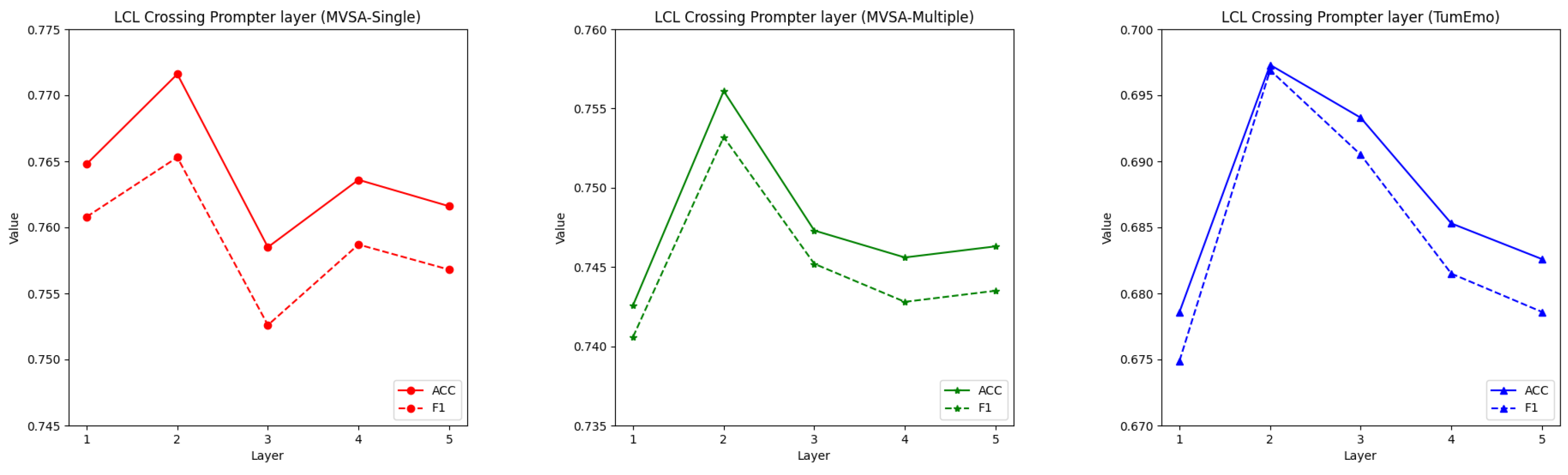

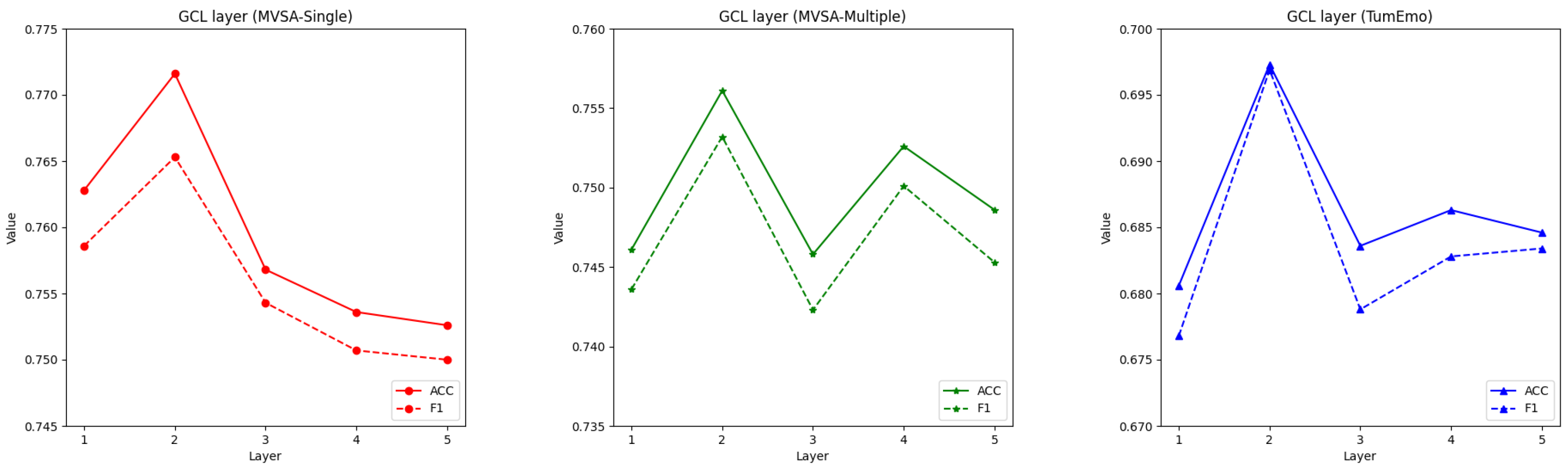

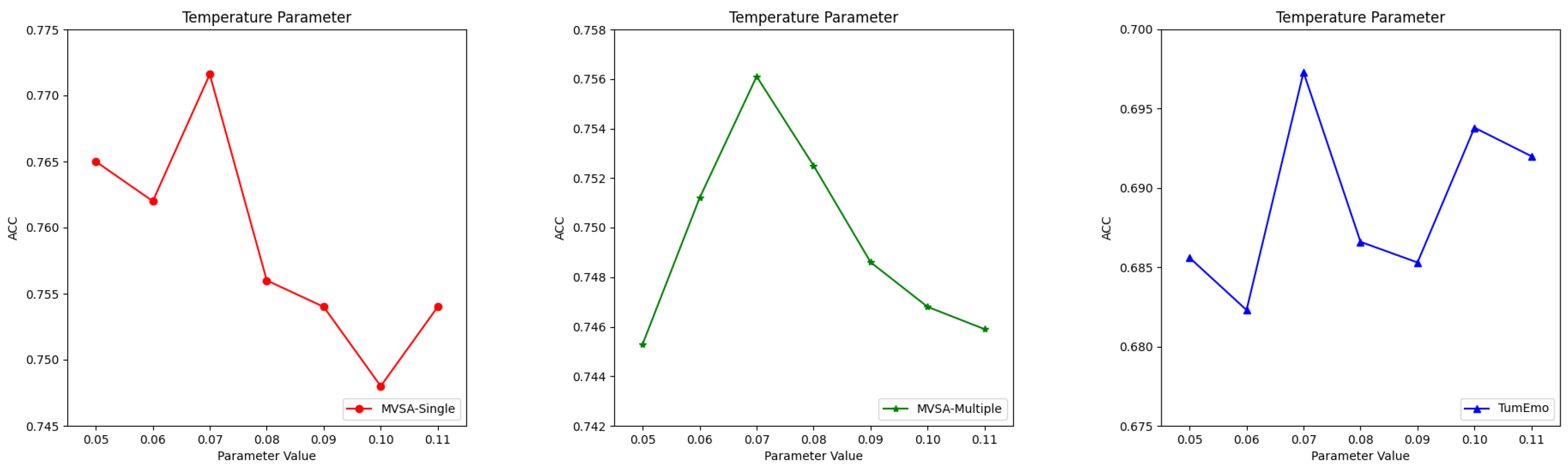

4.7. Parametric Experiments

4.8. Model Complexity Analysis

4.9. Cross-Dataset Generalization Evaluation

4.10. Fine-Grained Performance Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Abbreviation

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, C.; Hu, Z. Multimodal sentiment analysis of social media based on top-layer fusion. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 8th International Conference on Computer and Communications (ICCC), Chengdu, China, 9–12 December 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, N.; Mao, W. MultiSentiNet: A deep semantic network for multimodal sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM on Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Singapore, 6–10 November 2017; pp. 2399–2402. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, N.; Mao, W.; Chen, G. A co-memory network for multimodal sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the 41st International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research & Development in Information Retrieval, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 8–12 July 2018; pp. 929–932. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Tang, H. Multimodal Alignment and Fusion: A Survey. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2411.17040 (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- Yu, W.; Xu, H.; Yuan, Z.; Wu, J. Learning modality-specific representations with self-supervised multi-task learning for multimodal sentiment analysis. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2021, 35, 10790–10797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, A.; Chen, M.; Poria, S.; Cambria, E.; Morency, L.-P. Tensor fusion network for multimodal sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Copenhagen, Denmark, 9–11 September 2017; pp. 1103–1114. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosal, D.; Akhtar, M.S.; Chauhan, D.; Poria, S.; Ekbal, A.; Bhattacharyya, P. Contextual inter-modal attention for multi-modal sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Brussels, Belgium, 31 October–4 November 2018; pp. 3454–3466. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, F.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Z.; Xu, J.; Li, Z. Image-text sentiment analysis via deep multimodal attentive fusion. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2019, 167, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Li, Z.; Tang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Ma, H. Heterogeneous graph convolution based on in-domain self-supervision for multimodal sentiment analysis. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 213, 119240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Shen, Y.; Lakshminarasimhan, V.B.; Liang, P.P.; Zadeh, A.B.; Morency, L.-P. Efficient low-rank multimodal fusion with modality-specific factors. In Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1:Long Papers), Melbourne, Australia, 15–20 July 2018; pp. 2247–2256. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, Z.; Jin, Y.; Yan, X.; Wang, C.; Yang, S.; Ge, H. Cross-modal hashing retrieval with compatible triplet representation. Neurocomputing 2024, 602, 128293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Li, L.; Yang, J.; Zhao, S.; Liu, H.; Qian, J. Multimodal sentiment analysis with image-text interaction network. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2023, 25, 3375–3385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.-H.H.; Bai, S.; Liang, P.P.; Kolter, J.Z.; Morency, L.-P.; Salakhutdinov, R. Multimodal transformer for unaligned multimodal language sequences. In Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Florence, Italy, 28 July–2 August 2019; pp. 6558–6569. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, X.; Zhang, C.; Niu, Z.; Wu, X. Multi-level attention map network for multimodal sentiment analysis. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2023, 35, 5105–5118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Zhang, C.; Geng, B. Deep multimodal data fusion. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 56, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuerhong, G.; Dai, X.; Tian, L.; Wushouer, M. An end-to-end image-text matching approach considering semantic uncertainty. Neurocomputing 2024, 607, 128386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Cao, D.; Li, L.; Li, S.; Ji, R. Microblog sentiment analysis based on cross-media bag-of-words model. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Internet Multimedia Computing and Service, Xiamen, China, 10–12 July 2014; pp. 76–80. [Google Scholar]

- You, Q.; Luo, J.; Jin, H.; Yang, J. Cross-modality consistent regression for joint visual-textual sentiment analysis of social multimedia. In Proceedings of the Ninth ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 22–25 February 2016; pp. 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, N. Analyzing multimodal public sentiment based on hierarchical semantic attentional network. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Intelligence and Security Informatics (ISI), Beijing, China, 22–24 July 2017; pp. 152–154. [Google Scholar]

- Truong, Q.-T.; Lauw, H.W. VistaNet: Visual aspect attention network for multimodal sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Third AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Thirty-First Innovative Applications of Artificial Intelligence Conference and Ninth AAAI Symposium on Educational Advances in Artificial Intelligence, Honolulu, HI, USA, 27 January–1 February 2019; pp. 305–312. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhu, H.; Xue, Z.; Liu, Z.; Tian, J.; Chua, M.C.H.; Liu, M. An image-text consistency driven multimodal sentiment analysis approach for social media. Inf. Process. Manag. 2019, 56, 102097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poria, S.; Cambria, E.; Hazarika, D.; Majumder, N.; Zadeh, A.; Morency, L.-P. Context-dependent sentiment analysis in user-generated videos. In Proceedings of the 55th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 30 July–4 August 2017; pp. 873–883. [Google Scholar]

- Basu, P.; Tiwari, S.; Mohanty, J.; Karmakar, S. Multimodal sentiment analysis of #MeToo tweets using focal loss (grand challenge). In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Sixth International Conference on Multimedia Big Data (BigMM), New Delhi, India, 24–26 September 2020; pp. 461–465. [Google Scholar]

- Thuseethan, S.; Janarthan, S.; Rajasegarar, S.; Kumari, P.; Yearwood, J. Multimodal deep learning framework for sentiment analysis from text-image web data. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/WIC/ACM International Joint Conference on Web Intelligence and Intelligent Agent Technology (WI-IAT), Melbourne, Australia, 14–17 December 2020; pp. 267–274. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, N.; Mao, W.; Chen, G. Multi-interactive memory network for aspect based multimodal sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Third AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Thirty-First Innovative Applications of Artificial Intelligence Conference and Ninth AAAI Symposium on Educational Advances in Artificial Intelligence, Honolulu, HI, USA, 27 January–1 February 2019; pp. 371–378. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Feng, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, D. Multimodal sentiment detection based on multi-channel graph neural networks. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers), Virtual, 1–6 August 2021; pp. 328–339. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, X.; Pu, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Gu, J.; Xu, D. BIT: Improving image-text sentiment analysis via learning bidirectional image-text interaction. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Gold Coast, Australia, 18–23 June 2023; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.; Chen, K.; Xia, R. Hierarchical interactive multimodal transformer for aspect-based multimodal sentiment analysis. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2023, 14, 1966–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xu, B.; Zhu, C.; Zhao, T. CLMLF: A contrastive learning and multi-layer fusion method for multimodal sentiment detection. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: NAACL 2022, Seattle, WA, USA, 10–15 July 2022; pp. 2282–2294. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Ren, C.; Yu, Z. Multimodal sentiment analysis based on cross-instance graph neural networks. Appl. Intell. 2024, 54, 3403–3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L.; et al. PyTorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 32, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019; pp. 8024–8035. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Li, D.; Savarese, S.; Hoi, S. BLIP-2: Bootstrapping Language-Image Pre-training with Frozen Image Encoders and Large Language Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.12597. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, W.; Li, J.; Li, D.; Tiong, A.M.H.; Zhao, J.; Wang, W.; Li, B.; Fung, P.; Hoi, S. InstructBLIP: Towards General-purpose Vision-Language Models with Instruction Tuning. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.06500. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Li, C.; Wu, Q.; Lee, Y.J. Visual Instruction Tuning. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.08485. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, S.; Chen, K.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Ge, W.; Song, S.; Dang, K.; Wang, P.; Wang, S.; Tang, J.; et al. Qwen2.5-vl technical report. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.13923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. Convolutional neural networks for sentence classification. In Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), Doha, Qatar, 25–29 October 2014; pp. 1746–1751. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, P.; Shi, W.; Tian, J.; Qi, Z.; Li, B.; Hao, H.; Xu, B. Attention-based bidirectional long short-term memory networks for relation classification. In Proceedings of the 54th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 2: Short Papers), Berlin, Germany, 7–12 August 2016; pp. 207–212. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.-W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-Training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1810.04805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Ma, D.; Li, S.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H. Text Level Graph Neural Network for Text Classification. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1910.02356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Feng, S.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Y. Image-text multimodal emotion classification via multi-view attentional network. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2021, 23, 4014–4026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Yuan, Z.; Xu, H.; Gao, K. Crossmodal translation based meta weight adaption for robust image-text sentiment analysis. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2024, 26, 9949–9961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezani, E.B. Sentiment analysis applications using deep learning advancements in social networks: A systematic review. Neurocomputing 2025, 634, 129862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dataset | Train | Val | Test | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MVSA-Single | 3611 | 450 | 450 | 4511 |

| MVSA-Multiple | 13,642 | 2409 | 2410 | 17,024 |

| TumEmo | 156,204 | 19,525 | 19,536 | 195,265 |

| Parameter | MVSA-Single | MVSA-Multiple | TumEmo |

|---|---|---|---|

| Learning rate | |||

| Dropout | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Epoch | 30 | 30 | 60 |

| Optimizer | AdamW | AdamW | AdamW |

| GCL layer | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| LCL Crossing Prompter layer | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Final Multi-Head Cross Attention layer | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| Temperature parameter | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 |

| Batch size | 32 | 32 | 16 |

| Modality | Model | MVSA-Single | MVSA-Multiple | TumEmo | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acc | F1 | Acc | F1 | Acc | F1 | ||

| Text | CNN | 0.6819 | 0.5590 | 0.6564 | 0.5766 | 0.6154 | 4774 |

| BiLSTM | 0.7012 | 0.6506 | 0.6790 | 0.6790 | 0.6188 | 0.5126 | |

| BERT | 0.7111 | 0.6970 | 0.6759 | 0.6624 | - | - | |

| TGNN | 0.7034 | 0.6594 | 0.6967 | 0.6180 | 0.6379 | 0.6362 | |

| Image | ResNet50 | 0.6467 | 0.6155 | 0.6188 | 0.6098 | - | - |

| OSDA | 0.6675 | 0.6651 | 0.6662 | 0.6623 | 0.4770 | 0.3438 | |

| SGN | 0.6620 | 0.6248 | 0.6765 | 0.5864 | 0.4353 | 0.4232 | |

| OGN | 0.6659 | 0.6191 | 0.6743 | 0.6010 | 0.4564 | 0.4446 | |

| DuIG | 0.6822 | 0.6538 | 0.6819 | 0.6081 | 0.4636 | 0.4561 | |

| Image-Text | HSAN | 0.6988 | 0.6690 | 0.6796 | 0.6776 | 0.6309 | 0.5398 |

| MultiSentiNet | 0.6984 | 0.6963 | 0.6886 | 0.6811 | 0.6418 | 0.5962 | |

| CoMN | 0.7051 | 0.7001 | 0.6992 | 0.6983 | 0.6426 | 0.5909 | |

| MGNNS | 0.7377 | 0.7270 | 0.7249 | 0.6934 | 0.6672 | 0.6669 | |

| MVAN | 0.7298 | 0.7298 | 0.7236 | 0.7230 | 0.6646 | 0.6339 | |

| CLMLF | 0.7533 | 0.7346 | 0.7200 | 0.6983 | - | - | |

| ITIN | 0.7519 | 0.7497 | 0.7352 | 0.7349 | - | - | |

| CTMWA | 0.7591 | 0.7574 | 0.7402 | 0.7384 | 0.6857 | 0.6860 | |

| Blip2-flan-t5-xl | 0.7321 | 0.7310 | 0.7213 | 0.7186 | 0.6544 | 0.6528 | |

| Instructblip-vicuna-13B | 0.7386 | 0.7406 | 0.7277 | 0.7243 | 0.6612 | 0.6604 | |

| LLaVA-v1.6-34B | 0.7483 | 0.7476 | 0.7308 | 0.7289 | 0.6693 | 0.6686 | |

| Qwen2.5-VL-72B | 0.7596 | 0.7581 | 0.7413 | 0.7389 | 0.6843 | 0.6840 | |

| DINMCL (our) | 0.7716 | 0.7653 | 0.7561 | 0.7532 | 0.6973 | 0.6969 | |

| Model | MVSA-Single | MVSA-Multiple | TumEmo | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acc | F1 | Acc | F1 | Acc | F1 | |

| w/o Captioner | 0.7701 | 0.7612 | 0.7533 | 0.7476 | 0.6912 | 0.6921 |

| w/o ViT | 0.7681 | 0.7587 | 0.7486 | 0.7413 | 0.6859 | 0.6840 |

| w/o Faster-RCNN | 0.7677 | 0.7538 | 0.7457 | 0.7388 | 0.6813 | 0.6809 |

| w/o GCL | 0.7588 | 0.7576 | 0.7453 | 0.7445 | 0.6758 | 0.6736 |

| w/o LCL | 0.7610 | 0.7583 | 0.7471 | 0.7456 | 0.6783 | 0.6767 |

| w/o GCL Key Prompt | 0.7686 | 0.7588 | 0.7549 | 0.7468 | 0.6812 | 0.6803 |

| w/o LCL Crossing Prompter | 0.7688 | 0.7563 | 0.7492 | 0.7484 | 0.6801 | 0.6796 |

| w/o CLIP | 0.7667 | 0.7576 | 0.7512 | 0.7428 | 0.6906 | 0.6911 |

| w/o Fusion & Prediction | 0.7611 | 0.7522 | 0.7488 | 0.7411 | 0.6856 | 0.6883 |

| DINMCL (our) | 0.7716 | 0.7653 | 0.7561 | 0.7532 | 0.6973 | 0.6969 |

| Models | Params (M) | FLOPs (G) | Inference Time (ms) | Memory (GB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNN | 1.5 | 0.4 | 5.2 | 1.1 |

| BiLSTM | 3.2 | 0.1 | 3.8 | 0.9 |

| BERT | 110.0 | 22.0 | 32.5 | 3.5 |

| TGNN | 4.8 | 1.2 | 12.1 | 2.2 |

| ResNet50 | 25.6 | 4.1 | 8.9 | 2.5 |

| OSDA | 15.7 | 3.5 | 15.3 | 2.8 |

| SGN | 5.5 | 1.5 | 13.5 | 2.3 |

| OGN | 6.1 | 1.8 | 14.2 | 2.4 |

| DuIG | 12.3 | 2.9 | 14.8 | 2.6 |

| HSAN | 8.9 | 2.1 | 16.7 | 2.7 |

| MultiSentiNet | 18.5 | 4.3 | 18.5 | 3.1 |

| CoMN | 22.4 | 5.7 | 20.2 | 3.4 |

| MGNNS | 9.7 | 3.2 | 18.7 | 3.0 |

| MVAN | 10.5 | 3.6 | 19.1 | 3.2 |

| CLMLF | 14.2 | 4.8 | 21.3 | 3.5 |

| ITIN | 28.3 | 6.9 | 23.6 | 3.9 |

| CTMWA | 122.1 | 18.5 | 25.3 | 5.1 |

| BLIP2-FLAN-T5-XL | 3500.0 | 280.0 | 420.0 | 28.0 |

| InstructBLIP-Vicuna-13B | 13,000.0 | 850.0 | 680.0 | 52.0 |

| LLaVA-1.6-34B | 34,000.0 | 1150.0 | 950.0 | 89.0 |

| Qwen2.5-VL-72B | 72,000.0 | 1520.0 | 2150.0 | 145.0 |

| DINMCL (Ours) | 158.7 | 24.3 | 35.6 | 6.8 |

| Model | MVSA-Single → MVSA-Multiple | MVSA-Multiple → MVSA-Single | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acc | F1 | Acc | F1 | |

| HSAN | 0.6532 | 0.6455 | 0.6568 | 0.6456 |

| MultiSentiNet | 0.6612 | 0.6573 | 0.6525 | 0.6519 |

| CoMN | 0.6678 | 0.6632 | 0.6568 | 0.6533 |

| MGNNS | 0.7053 | 0.7006 | 0.6963 | 0.6947 |

| MVAN | 0.7066 | 0.7021 | 0.6989 | 0.6997 |

| CLMLF | 0.7235 | 0.7107 | 0.6879 | 0.6726 |

| ITIN | 0.7266 | 0.7215 | 0.7049 | 0.6987 |

| CTMWA | 0.7423 | 0.7388 | 0.7263 | 0.7187 |

| DINMCL (our) | 0.7705 | 0.7638 | 0.7557 | 0.7528 |

| Model | MVSA-Single | MVSA-Multiple | TumEmo | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balanced Acc | Macro-F1 | Balanced Acc | Macro-F1 | Balanced Acc | Macro-F1 | |

| HSAN | 0.6876 | 0.6538 | 0.6773 | 0.6682 | 0.6288 | 0.5147 |

| MultiSentiNet | 0.6842 | 0.6773 | 0.6835 | 0.6679 | 0.6283 | 0.5779 |

| CoMN | 0.6743 | 0.6689 | 0.6786 | 0.6735 | 0.6275 | 0.5659 |

| MGNNS | 0.6935 | 0.6872 | 0.6780 | 0.6679 | 0.6357 | 0.6342 |

| MVAN | 0.6897 | 0.6826 | 0.6771 | 0.6753 | 0.6375 | 0.6249 |

| CLMLF | 0.7356 | 0.7188 | 0.7163 | 0.6830 | - | - |

| ITIN | 0.7388 | 0.7378 | 0.7156 | 0.7189 | - | - |

| CTMWA | 0.7371 | 0.7389 | 0.7347 | 0.7286 | 0.6673 | 0.6649 |

| Blip2-flan-t5-xl | 0.7156 | 0.7143 | 0.7049 | 0.7086 | 0.6375 | 0.6353 |

| Instructblip-vicuna-13B | 0.7186 | 0.7173 | 0.7082 | 0.7010 | 0.6383 | 0.6377 |

| LLaVA-v1.6-34B | 0.7204 | 0.7213 | 0.7086 | 0.7097 | 0.6473 | 0.6347 |

| Qwen2.5-VL-72B | 0.7277 | 0.7276 | 0.7120 | 0.7167 | 0.6486 | 0.6471 |

| DINMCL (our) | 0.7711 | 0.7642 | 0.7537 | 0.7518 | 0.6947 | 0.6915 |

| Abbreviation | Full Name |

|---|---|

| DINMCL | Dual-path Interaction Network with Multi-level Consistency Learning |

| GCL | Global Congruity Learning |

| LCL | Local Crossing-Congruity Learning |

| BERT | Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers |

| BLIP | Bootstrapping Language-Image Pre-training |

| CLIP | Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training |

| CLMLF | Cross-modal Translation-Based Meta Weight Adaptation |

| CTMWA | Contrastive Learning-Multilayer Fusion |

| FFN | Feed-Forward Network |

| GAT | Graph Attention Network |

| ITIN | Interactive Transformer Integration Network |

| LLaVA | Large Language and Vision Assistant |

| MGNNS | Multi-channel Graph Neural Network |

| MVAN | Multi-view Attention Network |

| ReLU | Rectified Linear Unit |

| RoBERTa | A Robustly Optimized BERT Pretraining Approach |

| ViT | Vision Transformer |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ji, Z.; Wu, C.; Xu, Q.; Wu, Y. Image–Text Sentiment Analysis Based on Dual-Path Interaction Network with Multi-Level Consistency Learning. Electronics 2026, 15, 581. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15030581

Ji Z, Wu C, Xu Q, Wu Y. Image–Text Sentiment Analysis Based on Dual-Path Interaction Network with Multi-Level Consistency Learning. Electronics. 2026; 15(3):581. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15030581

Chicago/Turabian StyleJi, Zhi, Chunlei Wu, Qinfu Xu, and Yixiang Wu. 2026. "Image–Text Sentiment Analysis Based on Dual-Path Interaction Network with Multi-Level Consistency Learning" Electronics 15, no. 3: 581. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15030581

APA StyleJi, Z., Wu, C., Xu, Q., & Wu, Y. (2026). Image–Text Sentiment Analysis Based on Dual-Path Interaction Network with Multi-Level Consistency Learning. Electronics, 15(3), 581. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15030581