4.2. Definitions

This section formally defines the paper’s main concepts.

Definition 1. Minimal Necessary Training Subset (MNTS): A subset Sm from the given dataset S that is sufficient to train an ML model M to achieve the model accuracy at the level or above the threshold T for a given ML algorithm A, e.g., 95% accuracy.

Thus, Sm is a result of some function F, Sm = F (S, M, A, T) that will be discussed later.

Definition 2. Maximal Unnecessary Training Subset (MUTS): A subset from dataset S after the exclusion of the minimal necessary training subset (MNTS) Sm from the following:

Definition 3. Minimal Magnitude of Training Subset: The number of elements |Sm| is the magnitude the minimal necessary training subset (MNTS) Sm.

Definition 4. Model Sureness (MS) Measure: The Model Sureness Measure U is the ratio of the number of unnecessary n-D points Su: |Su| = |S| − |Sm| to all points in set S:

Larger values of

U indicate that more unnecessary points can be excluded from the training data to discover a model by algorithm

A that satisfies threshold

T accuracy. This larger

U will also indicate a higher potential for user trust in the model.

This definition gives a concrete measure of the reduction in the data redundancy.

Definition 5. Model Sureness Lower Bound (MSLB): It is a number LB that is not any greater than the Model Sureness measure:

Definition 6. Tight Model Sureness Lower Bound (TMSLB): It is a lower bound LBT such that U − LBT ≤ ε, where ε is the allowed difference between U and LBT.

Definition 7. Model Sureness Upper Bound (MSUB): It is a number LUB that is no less than the Model Sureness measure:

Definition 8. Tight Model Sureness Upper Bound (TMSUB): It is a number LTU such that LTU − U ≤ ε, where ε is an allowed difference of U and LTU.

Definition 9. Upper Bound Minimal Training Subset: The subset SUB of n-D points from set S that were needed to produce a model with Model Sureness Upper Bound LTU.

The proposed Model Sureness measure directly captures the data redundancy. Noise is not represented explicitly in this measure, but it is reflected indirectly, since a high data redundancy may arise from factors such as repeated or near-duplicate cases rather than noise alone. The impact of noise can potentially be assessed by observing changes in the model accuracy as certain cases are removed. This idea is formalized in Definition 10.

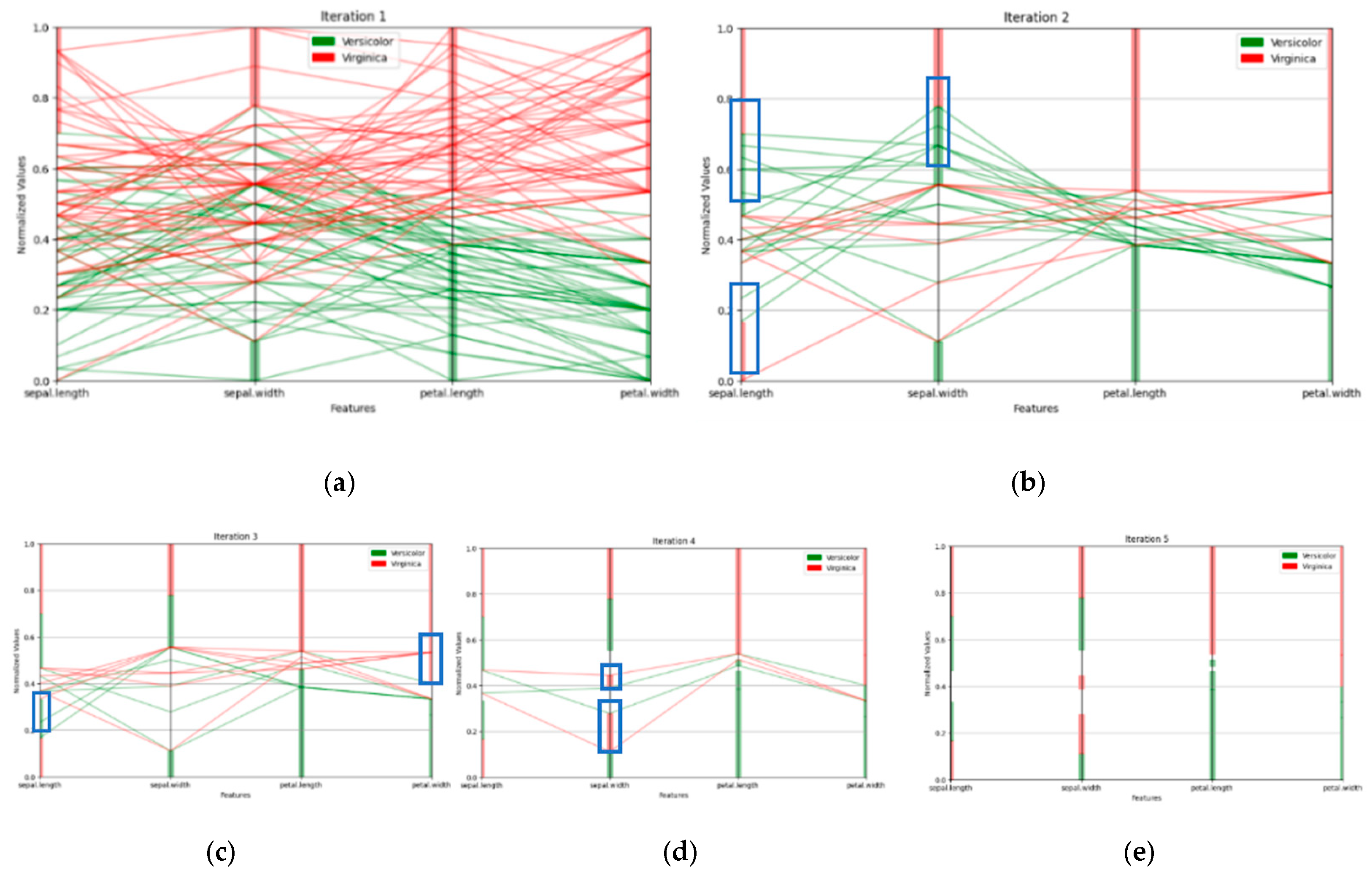

Changes in model accuracy can be measured on both the training and test datasets. A decrease in training accuracy may indicate the addition of more difficult cases, such as noisy cases, cases near class boundaries, or cases located in regions of class overlap. Changes in test accuracy may also indicate a mismatch between the distributions of the training and test data.

Section 5 presents examples of non-monotonic accuracy behavior that can be indicative of noise.

Definition 10. Bounded Noise Reduction (BNR): A positive difference Ac(Small) − Ac(Full) > 0, where Ac(Small) is the accuracy on the Small dataset, indicating that the Full dataset can contain noise cases because their removal increased accuracy. For practical reasons, we often search only for an upper-bound minimal training data subset . Computing the exact Model Sureness measure value, or tight bounds on it, can require an exhaustive search involving model evaluations produced by algorithm over multiple subsets of dataset . The number of such model computations, denoted as , and the computational cost of each model computation, denoted as , depend on the algorithm , dataset , and specified accuracy threshold , formally defined below:

Definition 11. The number of times that algorithm A computes models {M} on subsets of dataset S is denoted as NMC.

Definition 12. The complexity of each model computation CMC by an algorithm A on a subset SRi of set S is denoted as CMC(SRi).

Definition 13. The total complexity of all model computation TMC by an algorithm A on all selected subsets {SRi} of set S is denoted as TMC(S) and it is a sum of all CMC(SRi):

Definition 14. The Convergence Rate R is defined where RunsSUCCESS is the number of runs the model was considered as “sure” and RunsTOTAL is the total number of runs attempted:

While we used the convergence criterion from Definition 14, other or additional criteria may be applied. If convergence fails, exit criteria can be used, as summarized below.

Convergence Criteria:

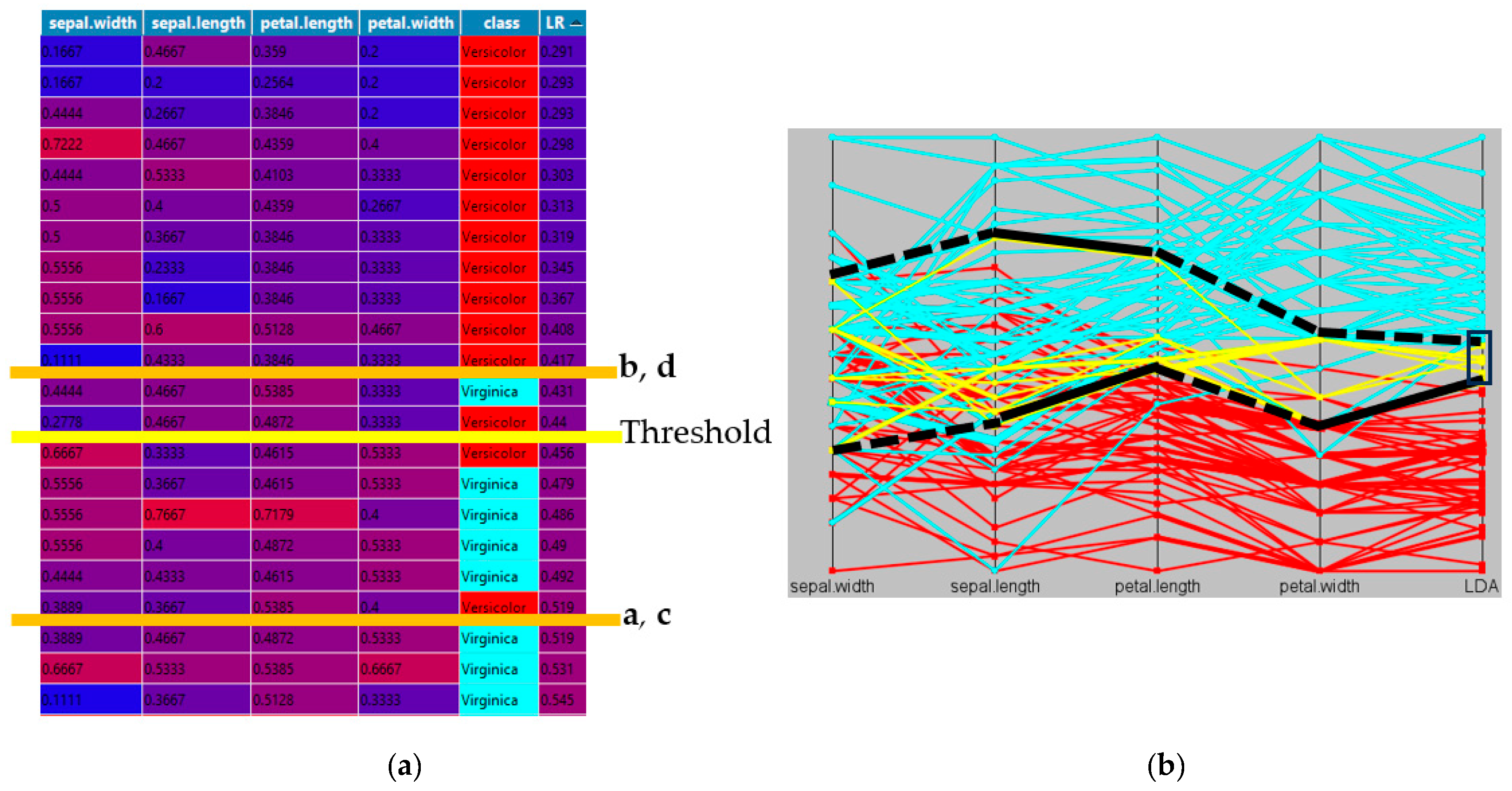

Model accuracy on test data. The primary convergence criterion studied in this work is the model accuracy on holdout test data. Testing ML models on unseen data evaluates their ability to generalize to new scenarios. Achieving some comparable test accuracy value (e.g., 95% or 99%) using a reduced training dataset indicates that certain training cases are redundant and not essential for the model performance. The lossless visualization of -dimensional data enables the identification of these redundant cases in the feature space. Evaluations using different holdout test sets may reveal different redundancy patterns, which can be examined through visualization.

Class-specific failure rate. This criterion is motivated by applications in which the misclassification of certain classes carries a higher risk than others. For example, in medical diagnosis, misclassifying malignant cases may be unacceptable, whereas some errors on benign cases may be tolerated to ensure conservative patient assessment.

Exit Criteria:

Limiting the number of training iterations. Setting an upper bound on the number of iterations (e.g., 100 or 1000) ensures that computations are completed in a predictable time frame. This also enables fair, apples-to-apples comparisons of different models in terms of computational cost, particularly when evaluating the suitability for deployment on hardware with limited computational resources.

Limiting model size. Imposing constraints on the model size (e.g., 1 MB or 5 GB) allows control over storage requirements, which is critical for model deployment on any resource-constrained platforms such as IoT devices and embedded systems.

Definition 15. The Per-Attribute Model Sureness Measure Z is the ratio of the number of unnecessary n-D points Su: |Su| = |S| − |Sm| to all points in set S per attribute. Let |D| be the number of attributes in the data D:

A hypercube is the generalization of the square with the center in point a and side length 2r, where r is a radius of the circle centered in point a.

Definition 16. The hypercube with the center n-D point a and side length 2r is a set of n-D points {w}, w = (w1, w2, …, wn) such that |ai − wi| ≤ r for all i∈ {1, 2,…, n}.

The hyper-rectangle (hyperblock) is a generalization of the rectangle with the center at point a and sides length 2ri.

Definition 17. The hyperblock (HB) with the center n-D point a and side length 2ri is a set of n-D points {w}, w = (w1, w2, …, wn) such that |ai − wi| ≤ ri for all i∈ {1, 2,…, n}.

Definition 18. The hyperblock algorithm is an ML algorithm that produces on training dataset D a set of hyperblocks HBik such that if point a∈ HBkm then a∈ Class k.

Definition 19. The total number HBs that a hyperblock algorithm A generates will be called the HB algorithm HB complexity of algorithm A.

The HB complexity criterion can be computed for smaller datasets from BAP and similar algorithms. A lower HB complexity (fewer HBs) enables simpler visualization. A representative data subset S intuitively predicts independent test set classes of each case. The formal concept of Model Sureness captures it as follows: Let V = MS (D, W, S, T, A), where V is the value of the Model Sureness measure MS for training data D, test data W, smaller training data subset S, accuracy threshold T (e.g., 0.95), and ML algorithm A. The Model Sureness metric yields value V as a sureness measure of the model M, built by algorithm A, on data D, evaluated on test data W.

Consistent with this paper’s goal, a representative subset S should allow an accurate class prediction for each test case. The formal concept of Model Sureness captures it as follows: Let V = MS (D, W, S, T, A), where V is the value of the Model Sureness measure MS for training data D, test data W, smaller training data subset S, accuracy threshold T (e.g., 0.95), and ML algorithm A. The Model Sureness metric yields value V as a sureness measure of the model M, built by algorithm A, on data D, evaluated on test data W.

The values V act as a measure of representativeness of subset S for A, D, and W. Similarly, set C complements S in D, C = D\S. In addition, values V can measure the redundancy of subset C for D and W. Thus, V measures the representativeness of subset S, and the redundancy of subset C, in addition to being a sureness measure of model M.

These definitions are complementary, not circular. This is because the same value V characterizes different components involved in the Model Sureness measure without introducing other formal definitions. They clarify the role of different components involved in the MS measure. However, the major benefit from presenting them comes from a potential increase in user trust of the model M. Similarly, dot product x⋅y = cos(Q) = 0 defines orthogonality as a property of unit vectors x and y. It also allows us to state that the angle Q between vectors x and y is 90° and cos(Q) = 0.

4.3. Algorithms

Algorithms to compute the Model Sureness measure are executed repeatedly to analyze different training subset selections. In the experiments here, an accuracy threshold of 95% is used. This is also the default setting in the software developed [

Supplementary Materials] and is a user-defined parameter that can be adjusted to different tasks. Users should be familiar with the accuracy achieved when training on the full dataset to inform the threshold value. Otherwise, preliminary experiments can be conducted to determine an appropriate accuracy level.

The default number of iterations in the developed software is set at 100; however, this parameter is adjustable. In our experiments, 100 iterations were sufficient to obtain an accurate Model Sureness measure on different datasets. The step size depends strongly on the size of the dataset. In our experiments, using approximately 1% data as the initial step size proved to be a reasonable starting point and was subsequently adjusted based on analysis of the results. Below are the algorithms to compute Model Sureness.

Here, C is a user-selected criterion that the model is retrained on modified data until achieving. It is represented as a Boolean function such as model accuracy > 0.95.

with two additional parameters of

S for split percentage (0 <

S < 1), where the test subset percentage is the complement 1 −

S value, and

P is the number of splits to test.

C is a user-selected criterion which the model is built towards achieving. Note, the number of splits trained should be at least up to a number where the resultant Model Sureness ratios barely change with added splits tested.

Here, BDIR is a computation direction indicator bit. BDIR = 0 if the MDS algorithm starts from the full set of n-D points S and excludes some n-D points from S. Bit BDIR = 0 if the MDS algorithm starts from some subset of set S and includes more n-D points from set S. The accuracy threshold T is some numerical percentage value 0 to 1, e.g., 0.95 for 95%. A predefined max number of iterations to produce subsets is denoted as IMAX. This algorithm (1) reads the triple <BDIR, T, IMAX>, and (2) updates and tests the training dataset with the IMDS, EMDS, and AHSG algorithms described below.

Multi-split Minimal Dataset Search (MSMDS) Algorithm: For data that are not split previously into training and test subsets, the user can specify the split number and percentage. Then, the MDS algorithm is run a split number of times over percentage-sized splits. This gives two additional parameters of S for the split percentage (0 < S < 1), where the test subset percentage is the complement 1—S value, and P is the number of splits to test. This is characterized by the quartet of the following:

Inclusion Minimal Dataset Search (IMDS) Algorithm: This iteratively adds a fixed percentage of n-D points from the initial dataset S to the learnt subset Si, trains a selected ML classifier A, and evaluates accuracy on all known separate test data Sev, iterating until all data are added and assessed to reach threshold T, e.g., 95% test accuracy.

Exclusion Minimal Dataset Search (EMDS) Algorithm: Contrasting with the Inclusion Minimal Dataset Search, this algorithm starts on the entire training dataset S and removes data iteratively, retraining an ML algorithm to assess reaching threshold T.

Additive Hyperblock Grower (AHG) Algorithm: This iteratively adds data subsets to the training data, builds hyperblocks (hyperrectangles) on the data using the IMHyper algorithm [

85], and then tests the class purity per hyperblock on each data subset added.

The initial or final dataset size depends on the minimum cases needed for training, defining how many cases are added or remain after removal.

Section 4.4 discusses scaling and runtime, while

Section 4.5 covers computational complexity.

4.4. Computational Complexity

Different ML algorithms have widely different computational complexities. Thus, the scaling behavior of the Model Sureness computation depends heavily on the complexity of the selected ML algorithm, the number of runs , and the iteration step size , while other parameters may also influence the computation. In simplified terms, an upper bound on the computational complexity can be expressed as , where the term denotes the complexity of running the selected ML algorithm on the full dataset , , is the number of cases added or removed at each iteration step, and is the number of times algorithm is executed for a given pair .

Below, we analyze the computational complexity of the Multi-Split Minimal Dataset Search (MSMDS) algorithm. For the Minimal Dataset Search (MDS) algorithm alone, split-related terms are omitted from the complexity calculations. The MDS algorithm’s complexity matches MSMDS’s, except without the split-number parameter as a scalar multiplier .

Parameters of Complexity Estimates:

—total number of cases in the dataset;

—dimensionality of the data;

—step size (number of cases added or removed per iteration);

—number of iterations for a given data split;

—training split percentage; for example, indicates that 70% of the cases are used for training and are used for the testing;

—number of different train–test splits;

—number of training cases used in a given iteration;

—time required to train the model at a given iteration using cases in -dimensional space;

—an upper bound on ;

—time required to test the model on the test dataset;

—number of training cases in a given split.

In these terms, the total upper bound on the computational complexity is as follows:

Assume that is upper-bounded by constant . Thus, a simplified complexity upper bound is . If and are comparable, the resultant algorithmic complexity is quadratic with respect to these parameters. When , , and are treated as constants, the simplified expression indicates a linear algorithmic complexity with respect to the number of cases . In contrast, a brute-force exploration of all subsets of cases yields an exponential complexity of .

For the WBC dataset, which contains 683 cases, a 70%:30% split yields 478 training cases that can be selected from

possible combinations, which is approximately

and is intractable to explore exhaustively. Testing multiple test sets arising from this combinatorial number of training datasets is thus not feasible. Consequently, we used either a fixed test set, as is commonly done for MNIST, or test sets selected ourselves. These limited test sets may miss the worst-case data splits; thus, as part of future work, we propose identifying the worst-case splits using methods such as those described in [

6] to obtain a more complete Model Sureness measure.

Formula (1) does not provide a tight upper bound, because training a model on smaller data subsets typically requires less time than training on the full dataset assumed in (1). Another reason that (1) is not a tight bound is that a predefined accuracy threshold may be reached without executing the ML algorithm for all iterations. Consequently, (1) represents a worst-case estimate. A best-case estimate occurs when the ML algorithm achieves the required accuracy after a single run. In our experiments, reported in the next section, the computation time was reasonable, as demonstrated by the presented results.

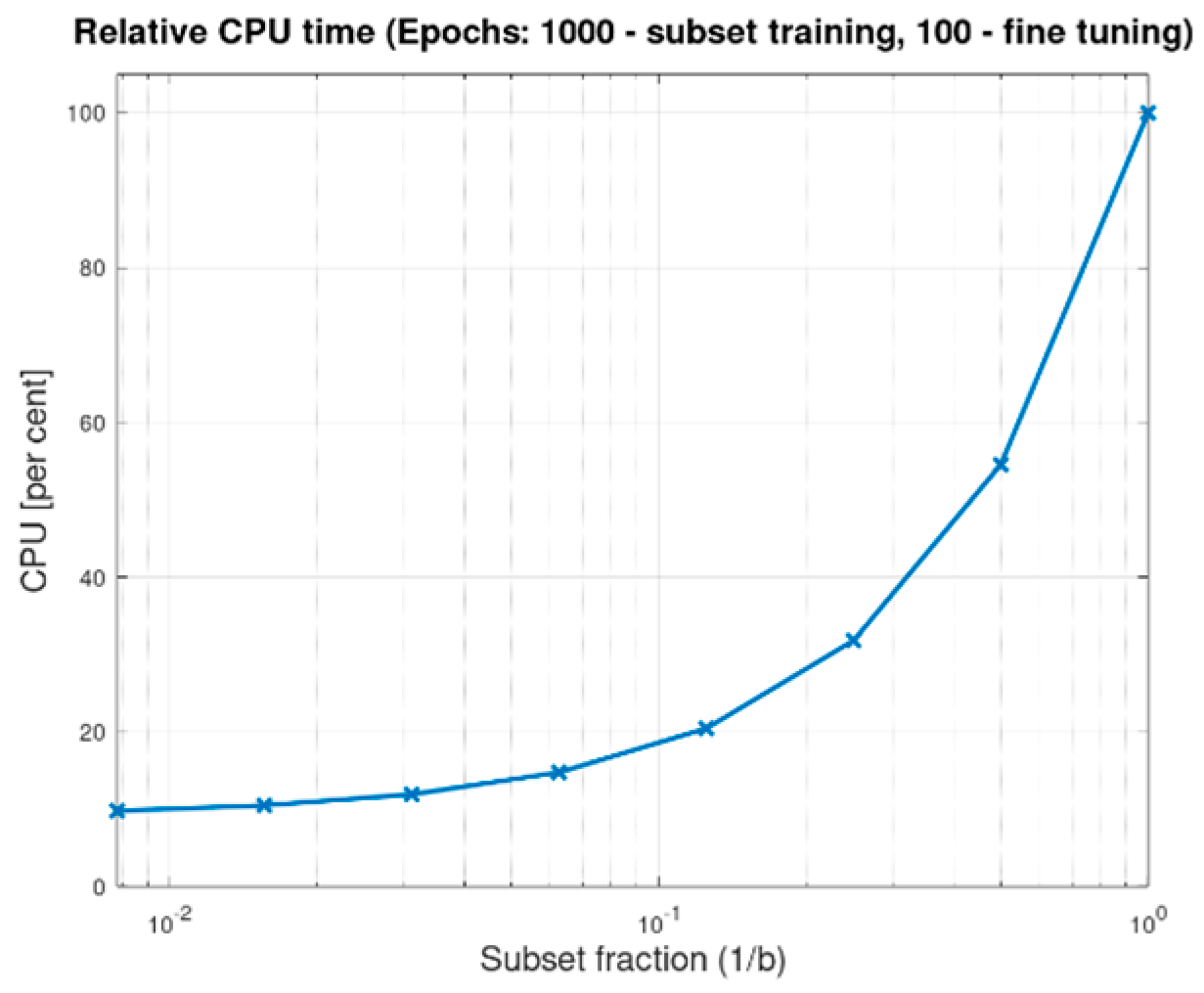

4.5. Scaling

To analyze the scaling of the Model Sureness measure computational method, we may consider two algorithms, and , with the same Model Sureness measure, for example, 0.8, but where algorithm requires half the computation time of algorithm to compute its Model Sureness measure, because is more complex. Algorithm therefore has an advantage in requiring fewer computational resources to compute its Model Sureness, in enabling additional experiments to identify different smaller subsets, and to explore Model Sureness more broadly. This advantage is particularly important for any algorithms with stochastic components, which can lead to models with varying accuracies across different runs. To account for this output variability, we run such algorithms multiple times and measure both the Model Sureness and its standard deviation.

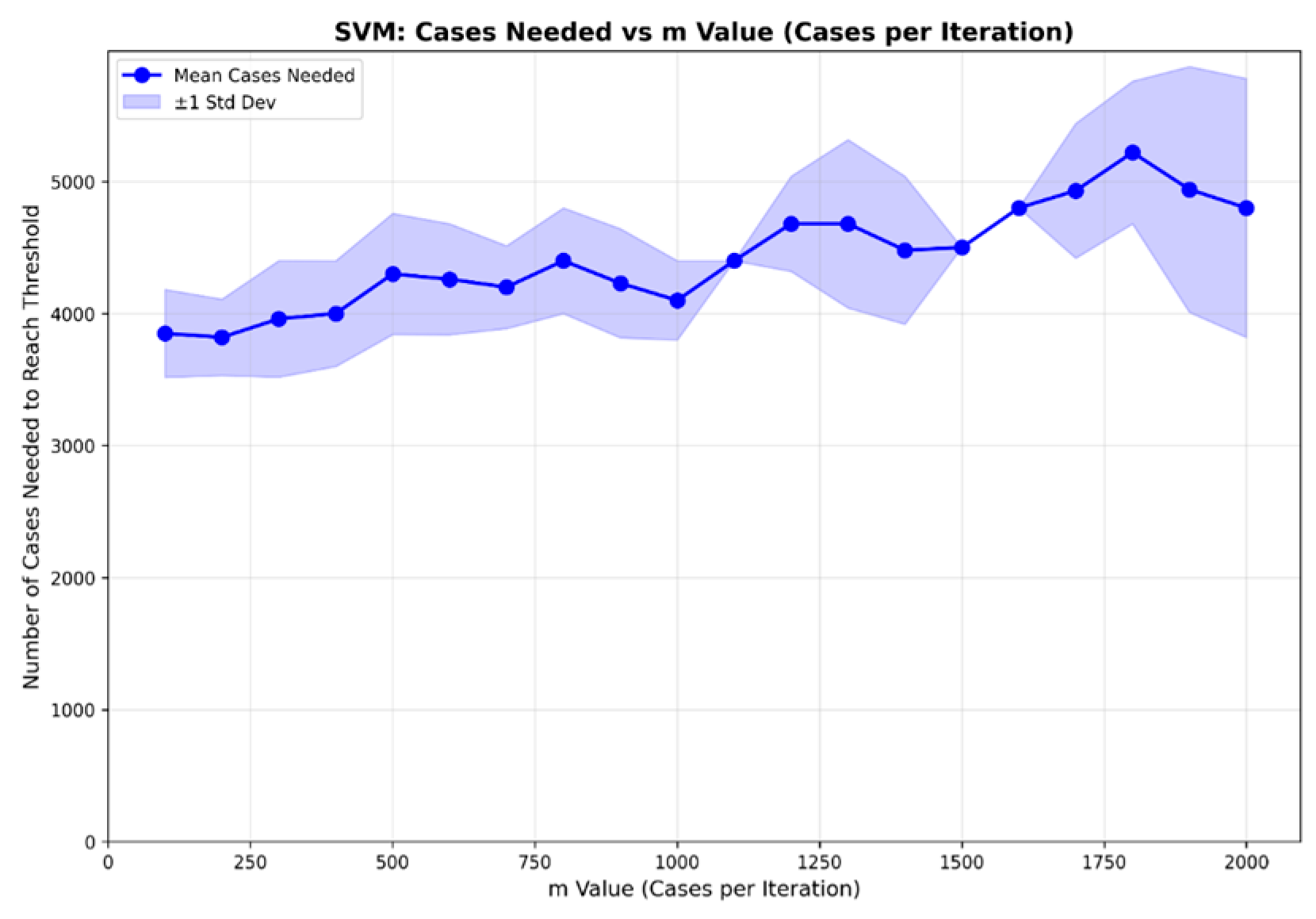

The following three benchmarks report the actual elapsed computational time for datasets of different sizes. These tests use a linear SVM as the algorithm and measure time scaling across different datasets and values of . All computational time-scaling tests were performed using multithreaded CPU execution on the same Intel 8-core i7-7700 CPU at 3.60 GHz, with 16 threads and 32 GB of RAM, running Debian Linux.

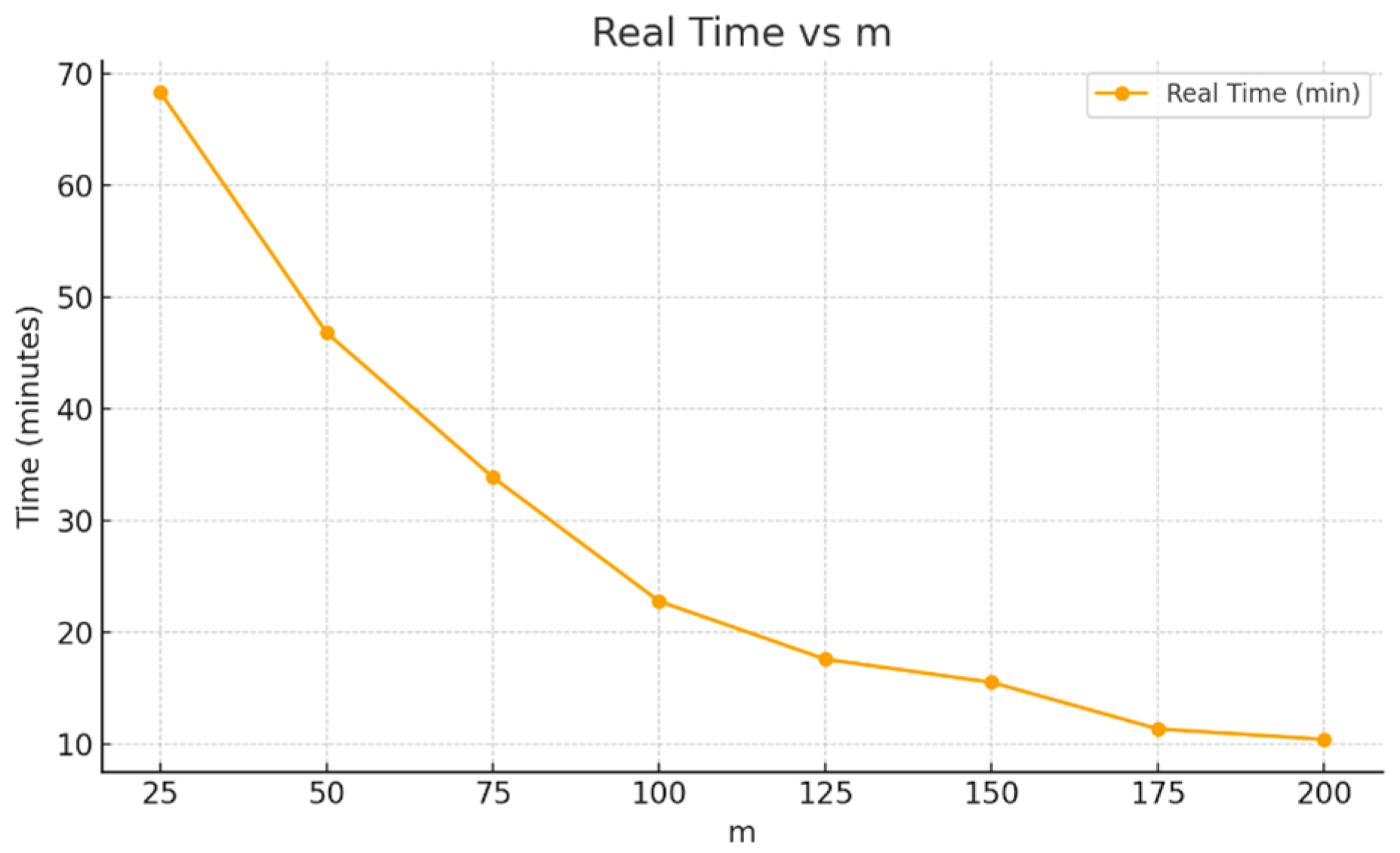

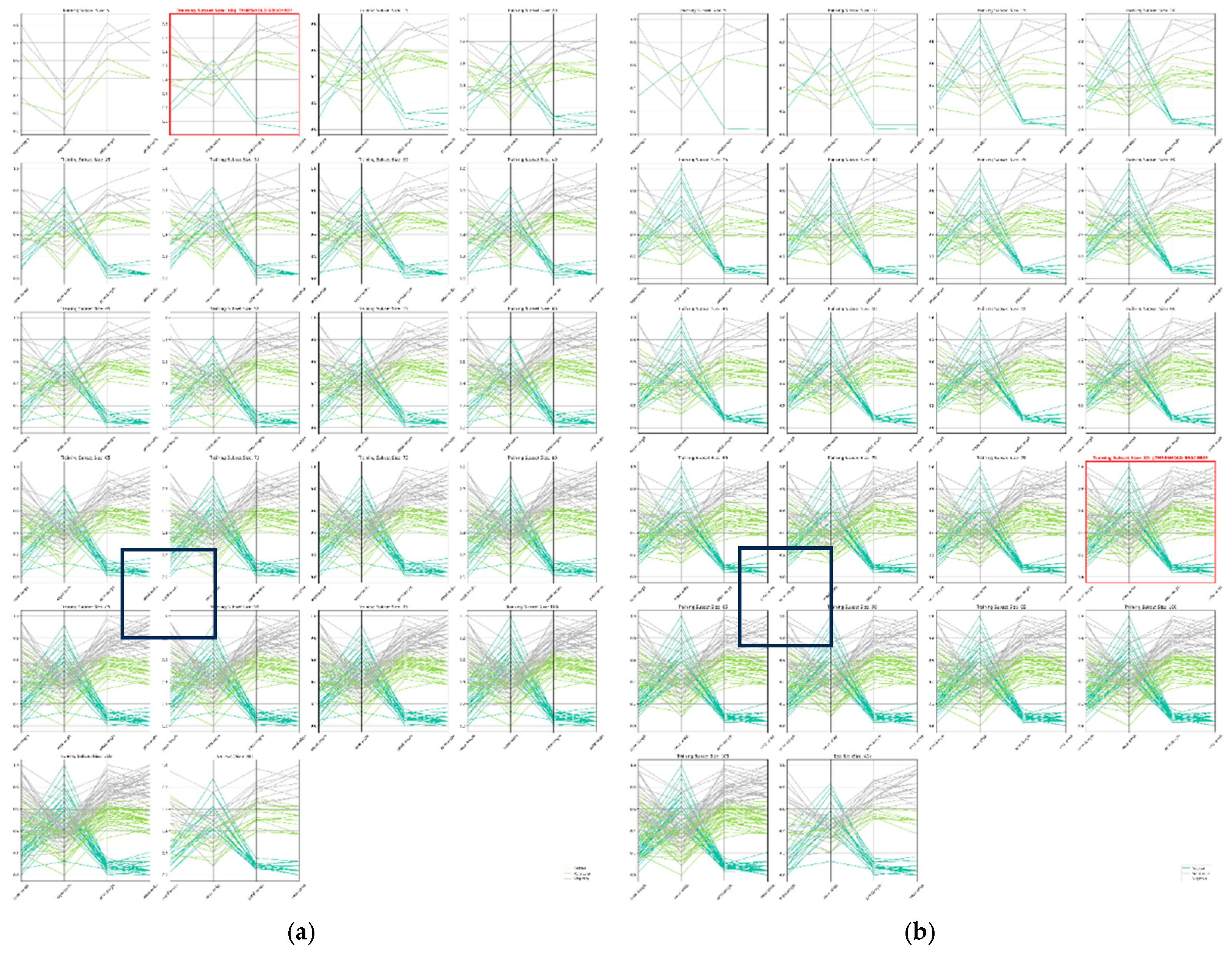

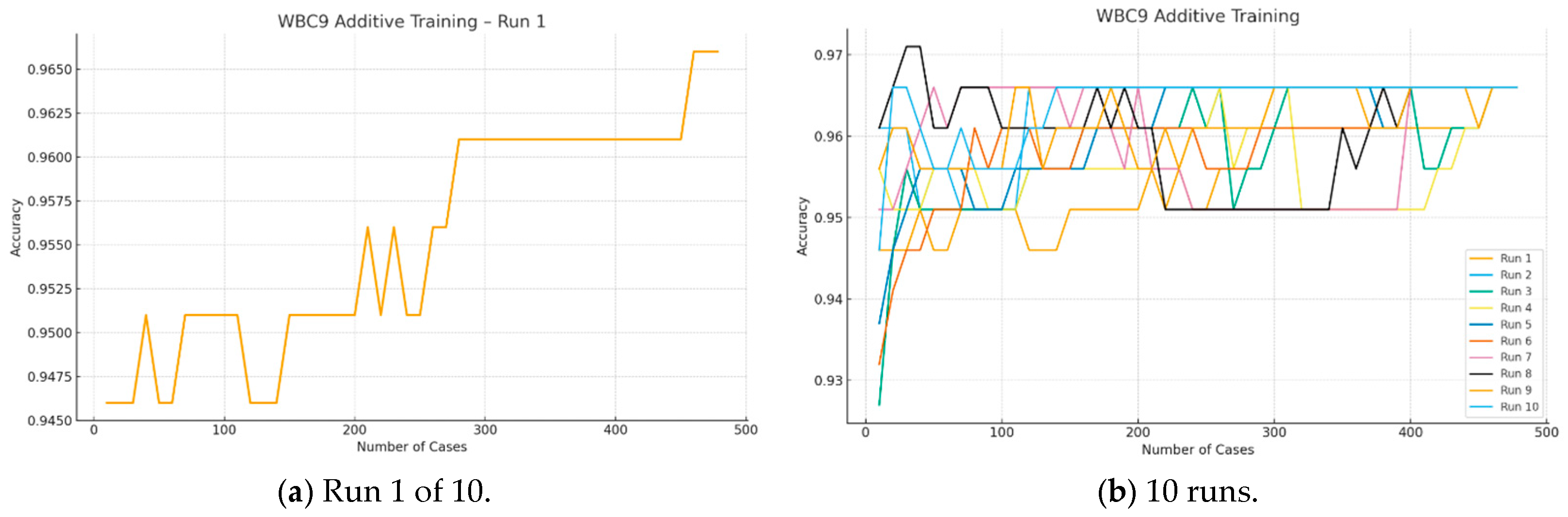

In the first experiment, we used the MNIST dataset, which is pre-split into 60,000 training cases and 10,000 test cases. In this experiment, 10 runs () were conducted for each value of (ranging from 25 to 200 cases) on the same data split, using BAP in a forward-direction for Model Sureness testing in which cases are added at each step. The ML algorithm used was a linear SVM. All tests in this study converged to a model accuracy of 95% or higher on the test data.

Figure 4 shows the results. Using a small step size of

cases required approximately 70 min, whereas an eight-times larger step of

cases required about 10 min. These times correspond to 10 runs; thus, each individual run took approximately 7 min and 1 min, respectively. Note that, for 60,000 training cases, a step of 25 cases represents only 0.042% of the dataset, and even the larger step of 200 cases corresponds to only 0.33% of the dataset. Therefore, both step sizes are well below 1% of the dataset—this enables a more fine-grained Model Sureness evaluation process.

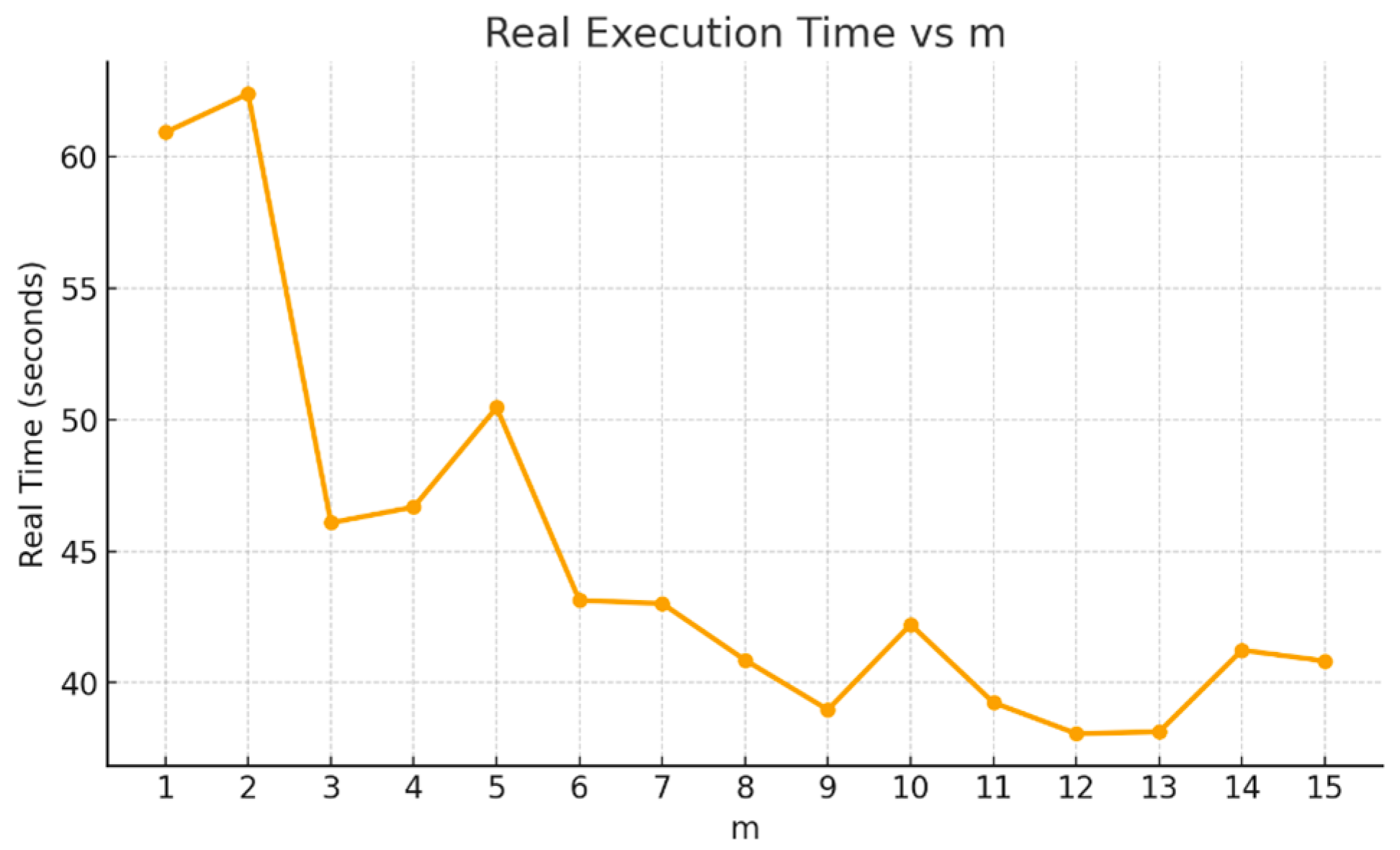

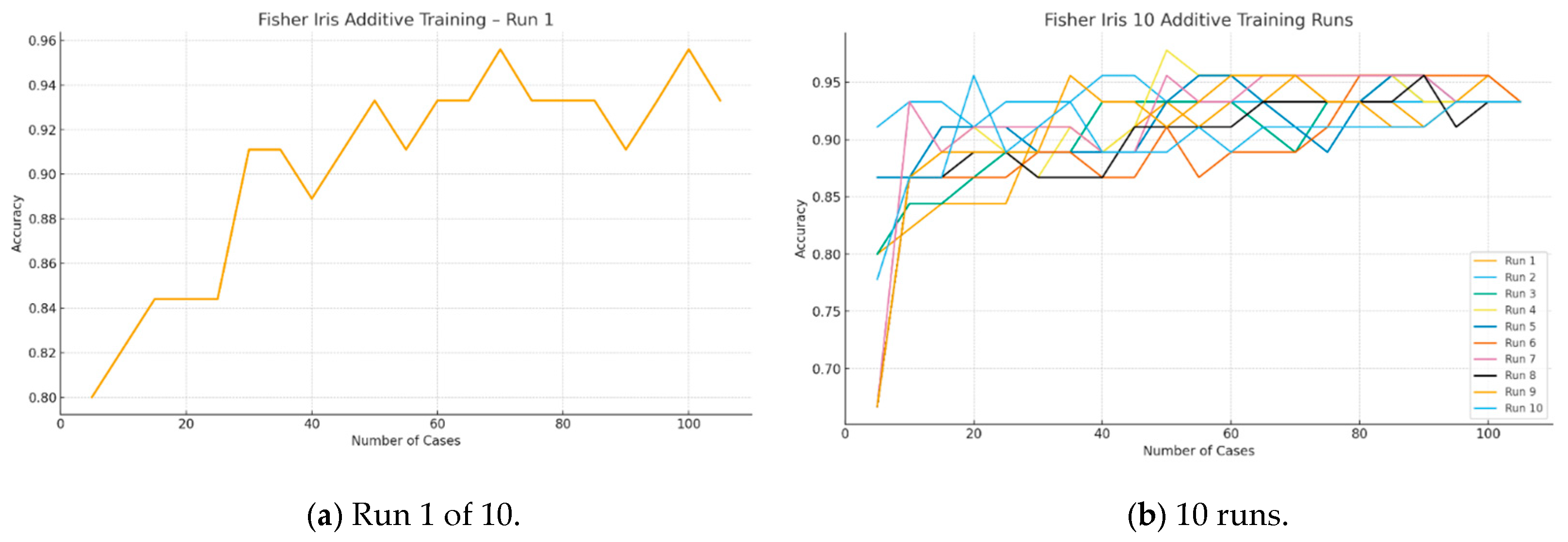

Figure 5 shows the results for the Fisher Iris dataset using a 70%:30% split of the 150 cases into training and test datasets. For a given split, we ran model training 100 times (

) to build models on the training data with step sizes ranging from a single case to 15 cases per step (

). Thus, for this small dataset, the step size

varies from approximately 1% to 15% of the training dataset. In this experiment, for each split, we performed 100 iterations, each time adding randomly sampled cases to the training data. Since we evaluated 15 different values of

, the algorithm was run 100 times for each value of

(e.g., for

, the algorithm was run 100 times).

Therefore, the entire model-training process was independently executed a total of

times. Moreover, instead of using only one singular 70%:30% training–test split, we employed 100 randomly generated splits (parameter

). This means that the linear SVM algorithm was run a total of

times for each value of

. The analysis of the results shown in

Figure 5 indicates that the most computationally intensive experiment required only approximately 170 s.

Figure 6 shows the results for the WBC dataset using 70% of the 683 cases for training, with 100 random splits and 100 model-training iterations per split. The step size

varied from 1 to 15 cases, corresponding to approximately 0.15% and 2.2% of the total dataset, respectively. The analysis of the results that is shown in

Figure 6 indicates that the most computationally intensive experiment required only about 70 s.

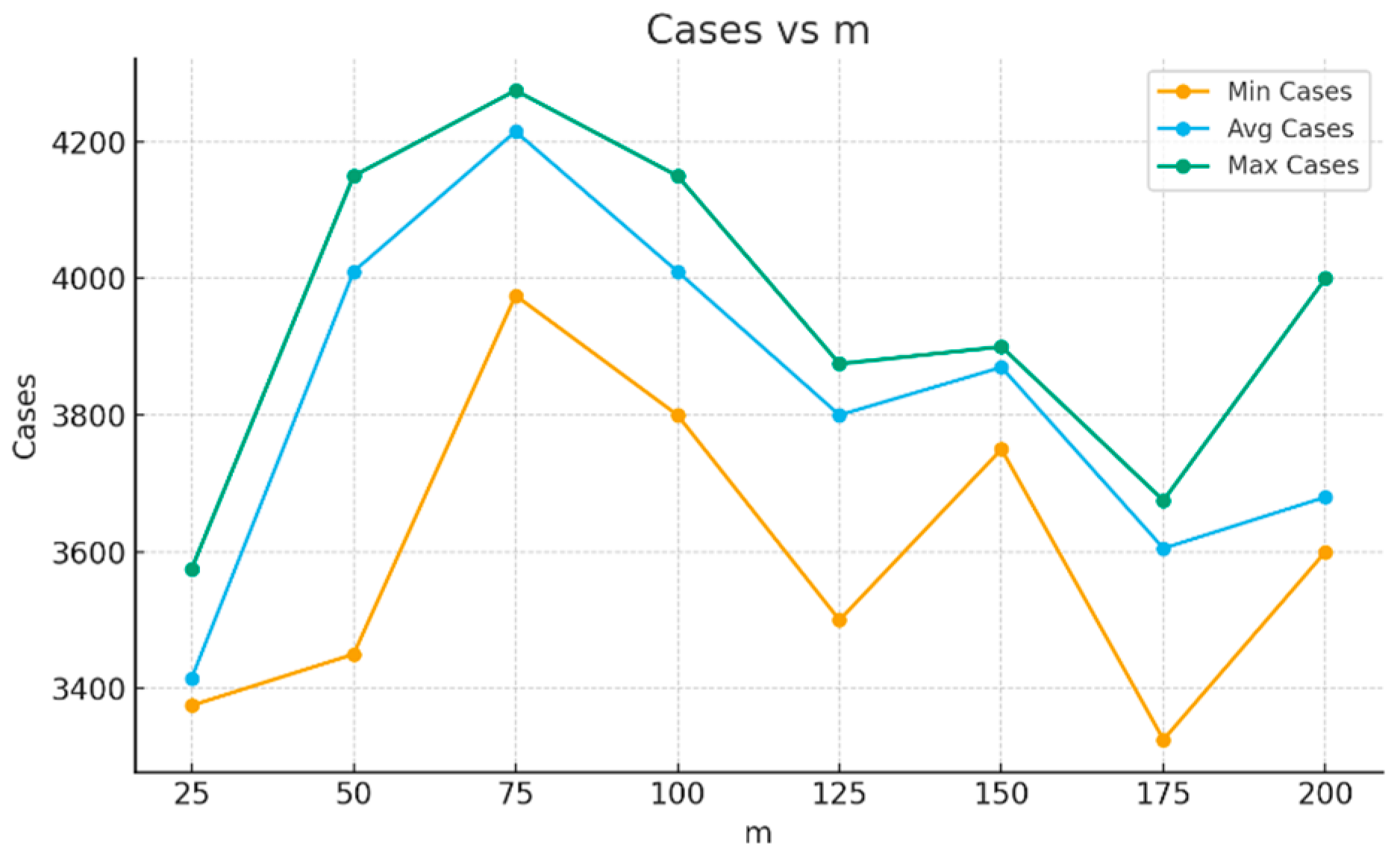

Figure 7 shows, for the MNIST handwritten digits dataset, the number of cases required for each test to converge to the 95% accuracy threshold. The green line represents the maximum number of cases, the blue line represents the average number of cases, and the orange line represents the minimum number of cases across the 10 runs. The average curve is close to the maximum curve, indicating that the average values are representative of most runs and that the maximum does not correspond to particularly unusual cases.

The number of cases on the average curve range from 3400 to 4200, or 5.7–7.0% of the full 60,000-case dataset. The maximum curve ranges from 3600 to 4300 cases, or 6.0–7.2% of the dataset. The minimum curve varies from 3400 to 3600 cases, corresponding to 5.7–6.0% of the data. Thus, although the curves in

Figure 7 are not monotonic, the variability for the maximum and average curves remains within approximately 2% of the total training data. The variability is more pronounced for the minimum (orange) curve; however, it is still relatively small, with the maximum value remaining below 4000 cases.