Virtual Testbed for Cyber-Physical System Security Research and Education: Design, Evaluation, and Impact

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Physical Testbeds

2.2. Virtual Testbeds

2.3. Hybrid Testbeds

2.4. Comparative Analysis of CPT Types

2.5. Overview of Virtual CPTs

2.6. Summary of Contributions

- Simulation and visualisation of the first transport-sector physical process using game engines.

- Improved network fidelity while maintaining resource efficiency, through lightweight Linux end nodes.

- Successfully testing end node DoS attacks, by carefully adjusting VirtualBox configuration.

- IDPS inclusion and custom rule implementation through OPNsense integration.

3. CPT Design and Implementation

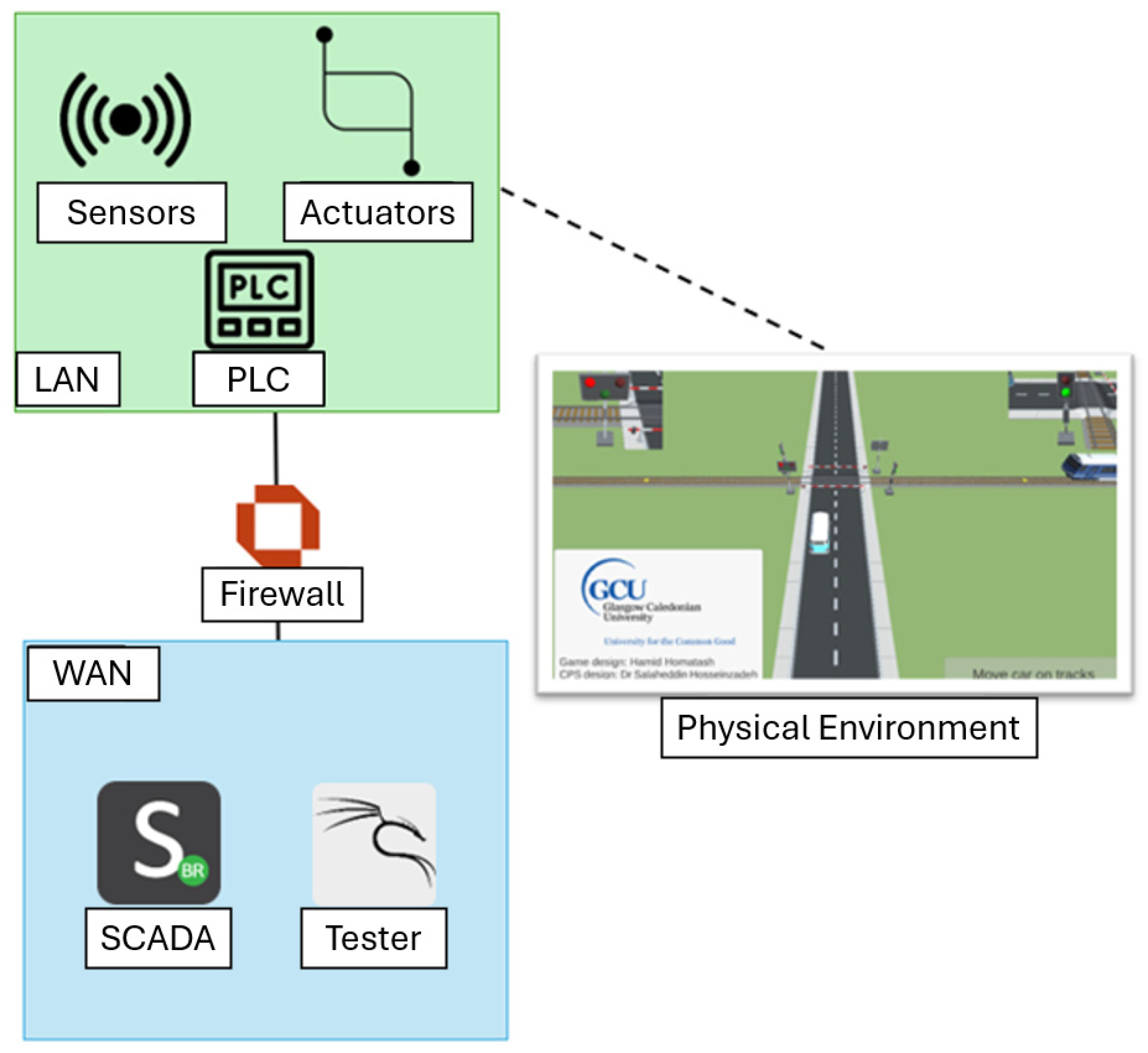

3.1. Physical Process

3.2. Architecture

- Level 0: field devices such as sensors and actuators.

- Level 1: consists of the PLC.

- Levels 2 and 3: the SCADA system, HMI, and data historian.

- Level 3.5: Industrial DMZ, which hosts the firewall, router, and IDPS.

3.3. Components

3.3.1. Control Zone (Level 0–1)

3.3.2. Industrial Zone (Level 2–3)

3.3.3. Industrial Demilitarised Zone (Level 3.5)

3.4. Network Topology

- Identification: use of vulnerability scanners to discover weaknesses.

- Exploit: demonstration of exploitation of key vulnerabilities.

- Mitigation: use of OPNsense as the main defence mechanism.

4. Penetration Testing the VCPT

4.1. Vulnerability Scanning

4.2. Vulnerability Testing

4.2.1. Attacks on SCADA System

4.2.2. Attacks on Field Devices

4.3. Improving Security Posture

4.3.1. Custom IDPS Rules

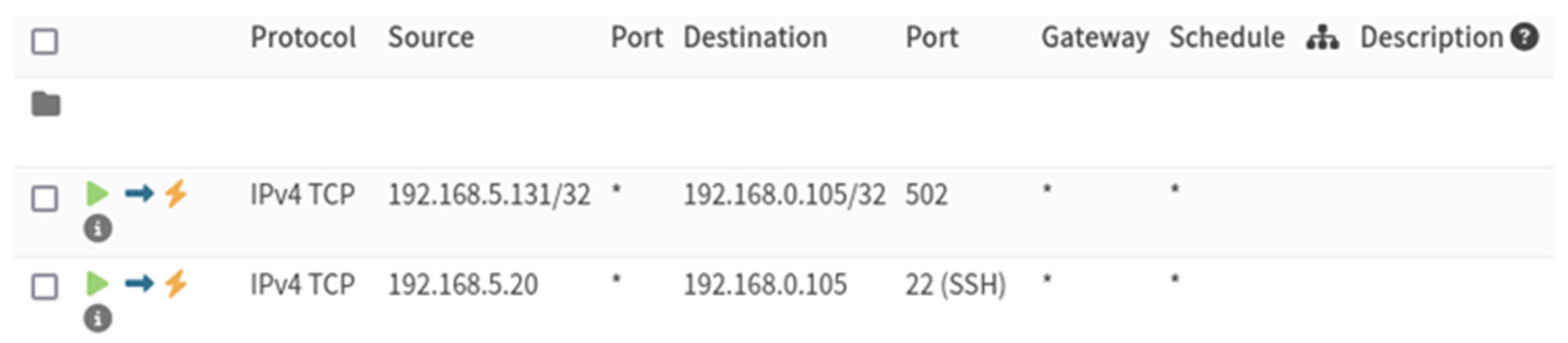

4.3.2. Custom Firewall Rules

- Permits traffic from the PLC to ScadaBR, through port 502;

- Blocks SSH traffic from PLC to all devices, except for tester machine (192.168.5.20).

5. Evaluation of Pedagogical Effectiveness and User Experience

5.1. Methodology and Data Ethics

5.2. Analysis

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alguliyev, R.; Imamverdiyev, Y.; Sukhostat, L. Cyber-physical systems and their security issues. Comput. Ind. 2018, 100, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Shi, Y.; Karnouskos, S.; Sauter, T.; Fang, H.; Colombo, A.W. Advancements in Industrial Cyber-Physical Systems: An Overview and Perspectives. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2023, 19, 716–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duo, W.; Zhou, M.; Abusorrah, A. A Survey of Cyber Attacks on Cyber Physical Systems: Recent Advances and Challenges. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2022, 9, 784–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humayed, A.; Lin, J.; Li, F.; Luo, B. Cyber-Physical Systems Security—A Survey. IEEE Internet Things J. 2017, 4, 1802–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunes, V.; Peter, S.; Givargis, T.; Vahid, F. A Survey on Concepts, Applications, and Challenges in Cyber-Physical Systems. KSII Trans. Internet. Inf. Syst. 2014, 8, 4242–4268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, A.; Steindl, G.; Hollerer, S. Integrated Safety and Security by Design in the IT/OT Convergence of Industrial Cyber-Physical Systems. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 7th International Conference on Industrial Cyber-Physical Systems (ICPS), St. Louis, MO, USA, 12–15 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hollerer, S.; Brenner, B.; Bhosale, P.R.; Fischer, C.; Hosseini, A.M.; Maragkou, S.; Papa, M.; Schlund, S.; Sauter, T.; Kastner, W. Challenges in OT Security and Their Impacts on Safety-Related Cyber-Physical Production Systems. In Digital Transformation; Vogel-Heuser, B., Wimmer, M., Eds.; Springer Vieweg: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machtemes, R.; Hale, G.; Walhof, M.; Ginter, A. Waterfall Security Solutions. 2025 Threat Report. March 2025. Available online: https://waterfall-security.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/2025-OT-Cyber-Security-Threat-Report.pdf?mc_cid=53c324e382&mc_eid=0069fc2d69 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Törngren, M.; Sellgren, U. Complexity Challenges in Development of Cyber-Physical Systems. In Principles of Modeling; Lohstroh, M., Derler, P., Sirjani, M., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 10760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Gou, X.; Huang, T.; Yang, S. Review on Testing of Cyber Physical Systems: Methods and Testbeds. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 52179–52194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talukder, M.R.H. CPS Security Testbed: Requirement Analysis, Prototype Design and Protection Framework. Master’s Thesis, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Neema, H.; Potteiger, B.; Koutsoukos, X.; Karsai, G.; Volgyesi, P.; Sztipanovits, J. Integrated simulation testbed for security and resilience of CPS. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Symposium on Applied Computing, (SAC ‘18); Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 368–374. [Google Scholar]

- Graja, I.; Kallel, S.; Guermouche, N.; Cheikhrouhou, S.; Kacem, A.H. A comprehensive survey on modeling of cyber-physical systems. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2020, 32, 4850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, W.; Wei, Q.; Liu, K.; Wu, H. A survey of industrial control system testbeds. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sahu, A.; Wlazlo, P.; Mao, Z.; Huang, H.; Goulart, A.; Davis, K.; Zonouz, S. Design and evaluation of a cyber-physical testbed for improving attack resilience of power systems. IET Cyber-Phys. Syst. Theory Appl. 2021, 6, 208–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J. The Need of Testbeds for Cyberphysical System Security. IEEE Secur. Priv. 2024, 22, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles-Durazno, A.; Moradpoor, N.; McWhinnie, J.; Russell, G.; Porcel-Bustamante, J. Implementation and Evaluation of Physical, Hybrid, and Virtual Testbeds for Cybersecurity Analysis of Industrial Control Systems. Symmetry 2021, 13, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, M.; Donadel, D.; Turrin, F. A survey on industrial control system testbeds and datasets for security research. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2021, 23, 2248–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Peng, Y.; Jia, K.; Dai, Z.; Wang, T. The design of ics testbed based on emulation, physical, and simulation (eps-ics testbed). In Proceedings of the 2013 Ninth International Conference on Intelligent Information Hiding and Multimedia Signal Processing, Beijing, China, 16–18 October 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Adepu, S.; Kandasamy, N.K.; Mathur, A. EPIC: An Electric Power Testbed for Research and Training in Cyber-Physical Systems Security. In Computer Security. SECPRE/CyberICPS 2018; Katsikas, K.S., Cuppens, F., Cuppens, N., Lambrinoudakis, C., Anton, A., Gritzalis, S., Mylopoulos, J., Kalloniatis, C., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 11387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.K.; Lee, W.; Yun, J.H.; Kim, H.C. Implementation of programmable CPS testbed for anomaly detection. In Proceedings of the 12th USENIX Workshop on Cyber Security Experimentation and Test (CSET 2019); USENIX Association: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2019; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, C.M.; Palleti, V.R.; Mathur, A.P. WADI: A water distribution testbed for research in the design of secure cyber physical systems. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Workshop on Cyber-Physical Systems for Smart Water Networks (CySWATER ‘17), Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 21 April 2017; pp. 25–28. [Google Scholar]

- Mathur, A.P.; Tippenhauer, N.O. SWaT: A water treatment testbed for research and training on ICS security. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Workshop on Cyber-Physical Systems for Smart Water Networks (CySWater), Vienna, Austria, 11–14 April 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kundig, S.; Angelopoulos, C.M.; Rolim, J. Modelled Testbeds: Visualizing and Augmenting Physical Testbeds with Virtual Resources. In Information Technology & Systems (ICITS 2018); Rocha, A., Guarda, T., Eds.; Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 721. [Google Scholar]

- Formby, D.; Rad, M.; Beyah, R. Lowering the barriers to industrial control system security with GRFICS. In Proceedings of the 2018 USENIX Workshop on Advances in Security Education (ASE 18), Baltimore, MD, USA, 13 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ekisa, C.; Briain, D.Ó.; Kavanagh, Y. VICSORT-A Virtualised ICS Open-source Research Testbed. In Proceedings of the 2022 Cyber Research Conference-Ireland (Cyber-RCI), Galway, Ireland, 25 April 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Maynard, P.; McLaughlin, K.; Sezer, S. An open framework for deploying experimental scada testbed networks. In Proceedings of the 5th International Symposium for ICS & SCADA Cyber Security Research 2018, Hamburg, Germany, 29–30 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mallouhi, M.; Al-Nashif, Y.; Cox, D.; Chadaga, T.; Hariri, S. A testbed for analyzing security of SCADA control systems (TASSCS). In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies (ISGT 2011), Anaheim, CA, USA, 17–19 January 2011; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Cintuglu, M.H.; Mohammed, O.A.; Akkaya, K.; Uluagac, A.S. A survey on smart grid cyber-physical system testbeds. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2016, 19, 446–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golder, A.; Gupta, D.; Roy, S.; Al Ahasan, M.A.; Haque, M.A. Automated Railway Crossing System: A Secure and Resilient Approach. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 14th Annual Ubiquitous Computing, Electronics & Mobile Communication Conference (UEMCON), New York, NY, USA, 12–14 October 2023; pp. 247–253. [Google Scholar]

- Bernieri, G.; Del Moro, F.; Faramondi, L.; Pascucci, F. A testbed for integrated fault diagnosis and cyber security investigation. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Control, Decision and Information Technologies (CoDIT), Saint Julian’s, Malta, 6–8 April 2016; pp. 454–459. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.; Tao, Y.; Yang, C.; Chen, H. MSICST: Multiple-Scenario Industrial Control System Testbed for Security Research. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2019, 60, 691–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smadi, A.A.; Ajao, B.T.; Johnson, B.K.; Lei, H.; Chakhchoukh, Y.; Al-Haija, Q.A. A Comprehensive survey on cyber-physical smart grid testbed architectures: Requirements and challenges. Electronics 2021, 10, 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonioli, D.; Tippenhauer, N.O. MiniCPS: A Toolkit for Security Research on CPS Networks. In Proceedings of the First ACM Workshop on Cyber-Physical Systems-Security and/or Privacy, Denver, CO, USA, 16 October 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almalawi, A.; Tari, Z.; Khalil, I.; Fahad, A. SCADAVT-A framework for SCADA security testbed based on virtualization technology. In Proceedings of the 38th Annual IEEE Conference on Local Computer Networks, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 21–24 October 2013; pp. 639–646. [Google Scholar]

- Ghaleb, A.; Zhioua, S.; Almulhem, A. SCADA-SST: A SCADA security testbed. In Proceedings of the 2016 World Congress on Industrial Control Systems Security (WCICSS), London, UK, 12–14 December 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Krotofil, M.; Larsen, J. Rocking the Pocket Book: Hacking Chemical Plants. In DefCon Conference; DEFCON: Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Maynard, P. ICS Testbed Framework. Github Repository. Available online: https://github.com/PMaynard/ICS-TestBed-Framework (accessed on 20 January 2026).

- Simulink; MathWorks: Natick, MA, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.mathworks.com/products/simulink.html (accessed on 20 January 2026).

- PowerWorld Simulator; PowerWorld Corporation: Champaign, IL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.powerworld.com/ (accessed on 20 January 2026).

- Factory I/O; Realism Ltd.: El Segundo, CA, USA, 2014. Available online: https://factoryio.com/ (accessed on 20 January 2026).

- Downs, J.J.; Vogel, E.F. A plant-wide industrial process control problem. Comput. Chem. Eng. 1993, 17, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oracle Corporation. Virtual Box. Available online: https://www.virtualbox.org/ (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- ScadaBR. Available online: http://www.scadasoftware.net/software/scadabr.html (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Electric Sheep Fencing, LLC. pfSense. Available online: https://www.pfsense.org/ (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Gomez, J.; Kfoury, E.F.; Crichigno, J.; Srivastava, G. A survey on network simulators, emulators, and testbeds used for research and education. Comput. Netw. 2023, 237, 110054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinzadeh, S.; Voutos, D.; Barrie, D.; Owoh, N.; Ashawa, M.; Shahrabi, A. Design and Development Considerations of a Cyber Physical Testbed for Operational Technology Research and Education. Sensors 2024, 24, 3923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Network Rail. Level Crossing Safety. Available online: https://www.networkrail.co.uk/communities/safety-in-the-community/level-crossing-safety/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Office of Rail and Road. Annual Report of Health and Safety on Britain’s Railways 2024 to 2025. Available online: https://www.orr.gov.uk/annual-report-health-and-safety-britains-railways-2024-2025 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Rail Accident Investigation Branch. Report 05/2025–Passenger Train Collision with a Road Vehicle at Redcar Level Crossing, Redcar and Cleveland, 1 May 2024. Department for Transport (Crown Copyright), April 2025. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/67ee5b5753fa8521c3248c63/R052025_250403_Redcar.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Network Rail. Giving You More Efficient and Reliable Level Crossings. Available online: https://www.networkrail.co.uk/stories/giving-you-more-efficient-and-reliable-level-crossings/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Williams, T.J. The Purdue enterprise reference architecture. Comput. Ind. 1994, 24, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assante, M.J.; Lee, R.M. The industrial control system cyber kill chain. SANS Inst. InfoSec Read. Room 2015, 1, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Unity Technologies. Unity. Available online: https://unity.com/ (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Alpine Linux. Available online: https://www.alpinelinux.org/about/ (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- de Brito, I.B.; de Sousa, R.T., Jr. Development of an Open-Source Testbed Based on the Modbus Protocol for Cybersecurity Analysis of Nuclear Power Plants. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 7942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OPNsense. Available online: https://opnsense.org/ (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- OPNsense Team. OPNsense Documentation. Available online: https://docs.opnsense.org/ (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Scarfone, K.; Souppaya, M.; Cody, A.; Orebaugh, A. Technical Guide to Information Security Testing and Assessment. In NIST Special Publication 800-115; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nessus. Tenable. Available online: https://www.tenable.com/products/nessus (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- MITRE Corporation. MITRE ATT&CK® Framework. Available online: https://attack.mitre.org/ (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- PortSwigger Ltd. PortSwigger. Available online: https://portswigger.net/ (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Abril, T.; Gamito, P.; da Motta, C.; Oliveira, J.; Dias, F.; Pinto, F.; Oliveira, M. Exploring a novel approach to cybersecurity: The role of ecological simulations on cybersecurity risk behaviors. Virtual Real. 2025, 29, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnitzler, K.; Holzberger, D.; Seidel, T. All better than being disengaged: Student engagement patterns and their relations to academic self-concept and achievement. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2021, 36, 627–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dove, G. The challenges of abstract concepts. In Handbook of Embodied Psychology: Thinking, Feeling, and Acting; Springer Nature: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 171–195. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, D.A. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development; FT Press: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lave, J.; Wenger, E. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Lampropoulos, G.; Sidiropoulos, A. Impact of gamification on students’ learning outcomes and academic performance: A longitudinal study comparing online, traditional, and gamified learning. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantafyllou, S.A.; Sapounidis, T.; Stamovlasis, D. Gamification and Computational Thinking in Education: A Review and a Meta-Analysis. In Technology, Knowledge and Learning; Springer Nature: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Gui, Y.; Cai, Z.; Yang, Y.; Kong, L.; Fan, X.; Tai, R.H. Effectiveness of digital educational game and game design in STEM learning: A meta-analytic review. Int. J. STEM Educ. 2023, 10, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srikant, S.; Aggarwal, V. A system to grade computer programming skills using machine learning. In Proceedings of the 20th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, New York, NY, USA, 24–27 August 2014; pp. 1887–1896. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez, A.; Saenz-de-Navarrete, J.; De-Marcos, L.; Fernández-Sanz, L.; Pagés, C.; Martínez-Herráiz, J.J. Gamifying learning experiences: Practical implications and outcomes. Comput. Educ. 2013, 63, 380–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, T.M.; Boyle, E.A.; MacArthur, E.; Hainey, T.; Boyle, J.M. A systematic literature review of empirical evidence on computer games and serious games. Comput. Educ. 2012, 59, 661–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deterding, S.; Dixon, D.; Khaled, R.; Nacke, L. From game design elements to gamefulness: Defining” gamification. In Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference: Envisioning Future Media Environments, Tampere, Finland, 28–30 September 2011; pp. 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Prince, M.J.; Felder, R.M. Inductive teaching and learning methods: Definitions, comparisons, and research bases. J. Eng. Educ. 2006, 95, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, M.; Clark, K.R. Game-based Learning and 21st century skills: A review of recent research. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 63, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| CPT Type | Network Fidelity | Flexibility | Scalability | Cost-Effective | Safety |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical | High | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Virtual | Low | High | High | High | High |

| Hybrid | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Sensor/Actuator | Function |

|---|---|

| PLC | Automation of the level-crossing operations |

| Traffic light signal and alarm | Signal vehicles of train arrival using lights and alarm |

| Train light signal | Singal trains about state of crossing |

| Barrier | Lowered or raised for traffic control |

| Train detection | Detect train arrival |

| Obstacle detection | Detect stranded vehicles on tracks |

| Vulnerability | Description | Severity |

|---|---|---|

| SCADA | ||

| CVE-2020-1938 (Ghostcat) | File inclusion and remote code execution (RCE) via AJP in Apache Tomcat | Critical |

| CVE-2021-26828 | Remote code execution (RCE) of JSP files via view_edit.shtm | Critical |

| CWE-1104 | Use of unmaintained components, Apache Tomcat 6.0.x end of life | Critical |

| CWE-89 | Improper neutralisation of special elements used in an SQL command (SQL injection) | High |

| CWE-204 CWE-307 | Observable response discrepancy Improper restriction of excessive authentication attempts | High |

| CWE-530 | Exposure of Apache Tomcat backup files | Medium |

| CWE-1021 | Improper restriction of rendered UI layers or frames, resulting in clickjacking | Medium |

| CVE-2021-26829 | Stored XSS vulnerability via system_settings.shtm | Medium |

| PLC and Field Devices | ||

| CWE-300 CWE-319 CWE-306 | Protocol (Modbus) accessible by any end node Clear text transmission and lack of encryption Missing authentication Resulting in false data injection, man-in-the-middle, etc. | High |

| OpenSSH vulnerabilities | ||

| CVE-2024-6387 CVE-2024-39894 | Arbitrary code execution to escalate root privileges | High |

| CVE-2023-48795 CVE-2023-51384 CVE-2023-51385 CVE-2025-32728 | Earlier versions of OpenSSH are vulnerable, which allows man-in-the-middle attacks Proper enforcement of DisableForwarding directive is not established | Medium |

| Action/ID | Description | Mitigated Vulnerability |

|---|---|---|

| Block/101 | HTTP GET request contains “=|whoami|ls|pwd” or similar | CVE-2020-1938 (Ghostcat) |

| Block/102 | HTTP POST request to “view_edit.shtm” contains “exec|bash” or similar | CVE-2021-26828 |

| Block/103 | more than 5000 SYN packets from same source in 5 s triggers the rule | DoS, SYN flood |

| Block/104 | more than 5000 ICMP requests from same source in 5 s triggers the rule | DoS, ICMP flood |

| Block/105 | more than 10 HTTP-POST attempts from same source in 5 s triggers the rule | Enumeration attack via HTTP-Proxy service |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Akeel, M.; Hosseinzadeh, S.; Zeeshan, M.; Homatash, H.; Owoh, N.; Ashawa, M. Virtual Testbed for Cyber-Physical System Security Research and Education: Design, Evaluation, and Impact. Electronics 2026, 15, 582. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15030582

Akeel M, Hosseinzadeh S, Zeeshan M, Homatash H, Owoh N, Ashawa M. Virtual Testbed for Cyber-Physical System Security Research and Education: Design, Evaluation, and Impact. Electronics. 2026; 15(3):582. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15030582

Chicago/Turabian StyleAkeel, Minal, Salaheddin Hosseinzadeh, Muhammad Zeeshan, Hamid Homatash, Nsikak Owoh, and Moses Ashawa. 2026. "Virtual Testbed for Cyber-Physical System Security Research and Education: Design, Evaluation, and Impact" Electronics 15, no. 3: 582. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15030582

APA StyleAkeel, M., Hosseinzadeh, S., Zeeshan, M., Homatash, H., Owoh, N., & Ashawa, M. (2026). Virtual Testbed for Cyber-Physical System Security Research and Education: Design, Evaluation, and Impact. Electronics, 15(3), 582. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15030582