1. Introduction

Technological breakouts in renewable energy sources (RESs) and the decrease in energy storage prices have exponentially led to increased system installations. Microgrid-decentralized local grids are the logical solution to decentralization and decarbonization in this new era. The US Department of Energy defines a microgrid as ‘a group of interconnected loads and distributed energy resources within clearly defined electrical boundaries that act as a single controllable entity with respect to the grid. A microgrid (MG) can connect and disconnect from the grid to enable it to operate in both grid-connected or island mode’ [

1]. Distributed generators (DGs) in the microgrid, typically RES, are intermittent and can be challenging, as these irregular power generators can disrupt the conventional operation of the utility grid (UG). Power fluctuations due to this erratic generation over considerable time periods must be mitigated since they can cause blackouts or other cascading problems.

Battery energy storage systems (BESSs) will reduce intermittency by installing RESs in large numbers or by installing grid-sized batteries as MGs are composed of multiple vulnerable components that must be integrated and optimized for interoperability and security. The failure of a critical component can initiate a cascade of failures, leading to the isolation of a part of the MG, and in extreme cases, blackouts. The conventional grid’s reliability is relatively high; therefore, introducing intermittent renewable sources will reduce grid reliability. System-integrated RES reliability studies are needed to ensure the integrity of MG safety-critical systems by assessing them at the component level due to their high uncertainty and variability. These assessments are vital to ensure dependable MG operation, which will benefit MG and utility grid (UG) owners by increasing revenue, power quality, and energy yield.

The challenges associated with renewable energy sources (RESs) have been recognized for decades [

2,

3], yet the lack of comprehensive field reliability data has limited quantitative assessment. Photovoltaic (PV) systems have been widely studied in stand-alone, stand-alone with BESS, and grid-connected modes. Early works applied failure mode and effect analysis (FMEA) and fault tree analysis (FTA) [

2], while subsequent studies employed quantitative reliability evaluations for large-scale PV systems, considering both grid-connected and islanded operation [

4]. Reliability, availability, and maintainability (RAM) analyses provided probabilistic models for PV subassemblies [

5], and FTA using exponential probability density functions helped identify critical components to improve reliability and reduce maintenance costs [

6]. Fuzzy reasoning Petri nets combined with FTA have also been used to analyze mechanical subsystems, enhancing fault prevention strategies [

7]. While these studies advanced PV reliability assessment, they largely focus on PV systems in isolation and do not consider their integration within a larger microgrid environment.

Wind turbines (WTs) similarly require detailed reliability quantification. Approaches such as FTA, failure mode, effects, and criticality analysis (FMECA), event sequence analysis, and structural reliability methods have been applied [

8]. Operational and maintenance cost assessments alongside RAM analyses have further informed subsystem reliability [

9]. Binary decision diagrams (BDDs) have been used to optimize maintenance scheduling and identify critical components in offshore turbines [

10,

11], and the power law process has been implemented to evaluate generators, gearboxes, and converters [

12]. FTA has also been employed to assess critical subassemblies in offshore WT farms [

13]. Despite these advances, studies often rely on limited field data, focus on subsystems in isolation, and rarely account for interactions within a complete microgrid framework.

Battery energy storage systems (BESSs) are increasingly integrated into power grids to enhance flexibility and support ancillary services [

14,

15]. Reliability models for AC/DC converters and battery modules have been proposed [

16], while FTA has been applied to identify failure modes in Li-ion batteries [

17,

18]. Nonetheless, existing analyses do not fully integrate BESS reliability with PV and wind systems in a grid-tied microgrid, limiting operational insights for combined RES and storage networks.

Microgrid-level studies address the broader integration of RES, power electronic interfaces, and operational contingencies. Reliability assessments considering cyber–physical interdependencies [

19], weather conditions, lifecycle management, and load profiles [

20,

21] have been performed, alongside economic evaluations of radial distribution networks using constrained nonlinear optimization [

22]. Analytical frameworks for operational transitions, such as islanded mode, have been proposed [

23], and studies on reliability metrics for European markets under varying RES penetration exist [

24,

25]. However, many of these works consider small-scale microgrids, focus primarily on islanded operation, or omit the critical role of power electronic converters and inverters. Studies using Monte Carlo simulations often address only isolated operation modes without evaluating grid-tied interactions [

26].

Although existing research has significantly advanced the reliability assessment of renewable energy systems, several critical gaps remain. First, most prior studies have analyzed individual subsystems in isolation—such as PV [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7], wind [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13], or BESS [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]—without adequately addressing the interactions and interdependencies among them when integrated into a grid-tied microgrid. This reductionist approach overlooks failure propagation pathways across different subsystems, leading to incomplete reliability insights. Second, while microgrid-level studies [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26] have attempted to incorporate multiple components, they often suffer from narrow scopes, focusing only on small-scale microgrids, single operation modes (typically islanded), or limited sets of components. Critical elements such as the utility grid interface, loads, and power electronic converters—which play pivotal roles in real-world operations—are frequently simplified or omitted altogether. Third, methodological limitations persist: the majority of studies rely on a single reliability assessment technique (e.g., FTA, RAM analysis, Monte Carlo simulation), which restricts the robustness of conclusions and provides limited guidance on the relative merits of alternative approaches.

To address these limitations, the present study develops a comprehensive fault tree model that integrates photovoltaics (PV), wind turbines (WTs), battery energy storage systems (BESSs), utility grid (UG), and load components into a single grid-tied microgrid framework. This holistic representation captures the true interdependencies between renewable sources, storage, load, and grid support, enabling a more realistic evaluation of system reliability under practical operating conditions. Unlike prior subsystem-specific or islanded-only analyses, our framework reflects the operational complexity of modern microgrids, including transitions between grid-tied and stand-alone modes.

Moreover, this study applies and compares multiple complementary reliability assessment methods, namely, exact fault tree analysis, Monte Carlo simulation, cut-set summation, cross-product, and the Esary–Proschan approximation (EP). While exact FTA provides benchmark accuracy, it is computationally intensive for complex systems with large numbers of components and cut-sets. Approximate and simulation-based methods, such as Monte Carlo and Esary–Proschan, offer alternative means of estimating system reliability with different trade-offs between accuracy and computational effort. By applying all these methods to the same microgrid model, this study (i) validates the consistency of results across approaches, (ii) highlights the strengths and weaknesses of each method, and (iii) offers practical guidance on method selection for reliability assessment of microgrids of varying size and complexity.

In achieving this, the present work not only overcomes the limitations of subsystem-focused or method-specific studies but also provides a comprehensive, validated, and practically useful framework for microgrid reliability analysis.

In this work, the authors have developed a comprehensive fault tree model of a microgrid incorporating photovoltaic (PV) systems, wind turbines, battery energy storage systems (BESSs), the utility grid (UG), and load components, thereby capturing the full operational and structural complexity often omitted in prior studies. To ensure a robust evaluation, the fault tree is analyzed using multiple solution methods, ranging from basic method to approximate and simulation-based techniques, enabling a balanced assessment of accuracy and computational efficiency. Furthermore, a range of availability metrics is calculated to complement reliability analysis, providing a more practical measure of the microgrid’s sustained performance under real-world operating conditions. The study also derives important measures that emphasize the physical aspects of the microgrid, quantifying the contribution of each subsystem to overall risk and system resilience. Finally, minimal cut-set analysis is employed to identify the most critical failure pathways, offering direct insights for targeted reliability improvements. Collectively, this integrated methodology advances beyond existing work by delivering a holistic and comparative framework for microgrid reliability and availability assessment.

The paper proceeds as follows. In

Section 2, FT basics and the FTs for each assembly are developed. The analysis of results is presented in

Section 3. Conclusions and future work are addressed in the final section.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 presents the FT model development and the associated qualitative interpretation of the system logic; quantitative approaches used to evaluate and solve the FT are described in

Section 3;

Section 4 documents the reliability and availability indices reported in this work; and diagnostic analysis based on minimal cut-sets and importance measures to identify structurally critical components and dominant contributors to the top event are presented in

Section 5.

Section 6 discusses the numerical results, including interpretation of differences among solution methods, while conclusions and future work are addressed in the final section.

2. Fault Tree Models

FTA analysis is a top-down failure analysis based on Boolean logic and is a directed acyclic graph with events and gates as nodes. The authors of [

27,

28] reviewed FTA basics, applications, modeling, methods, and analysis. Vesely et al. [

29] wrote a reactor safety study report discussing the basics and importance of FTA. The characteristics of the FTA discussed in [

30] identify it as the best choice to determine the reliability of complex systems such as an MG.

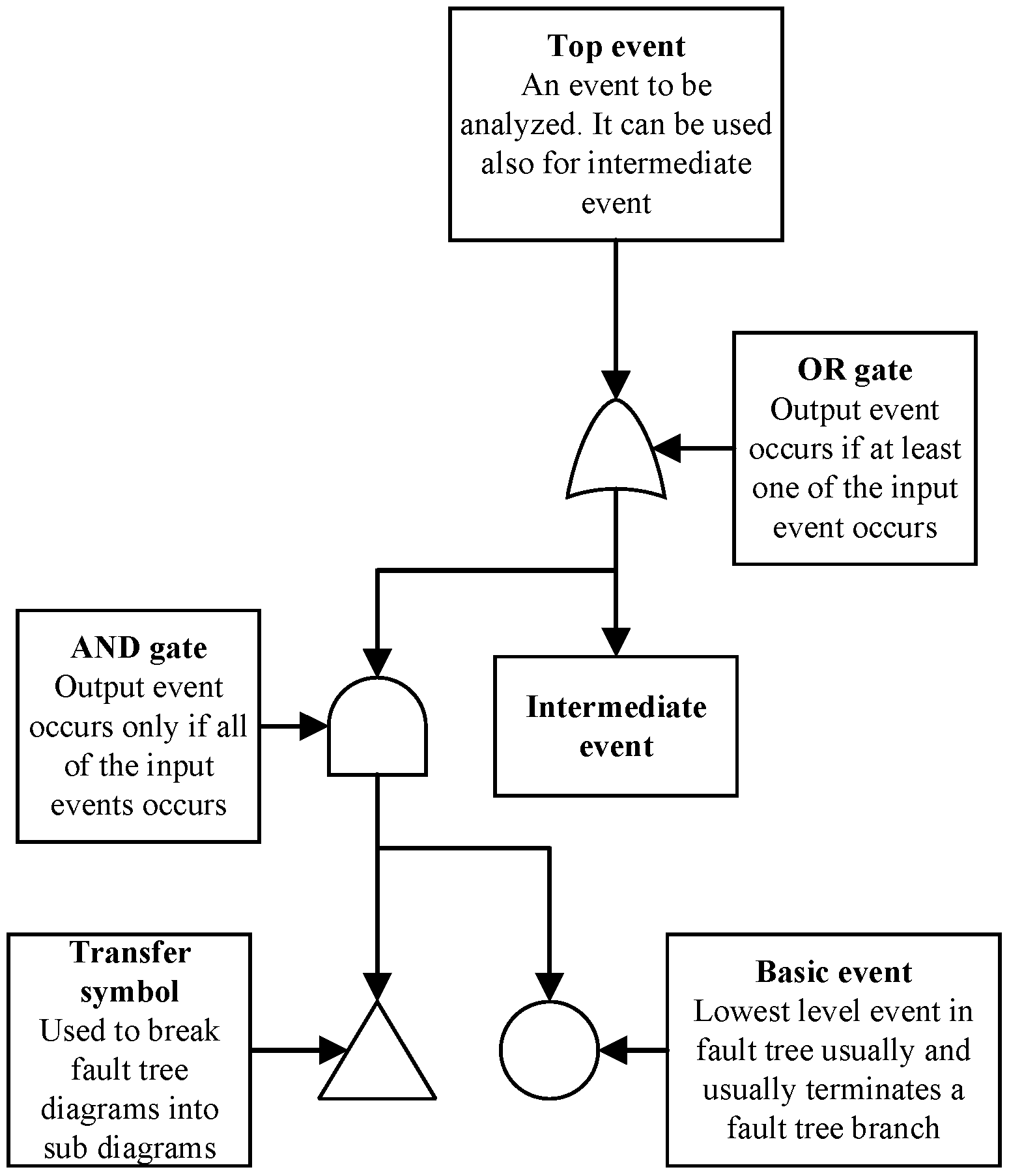

Figure 1 shows the general structure of a typical fault tree diagram with gates and event descriptions used in this work.

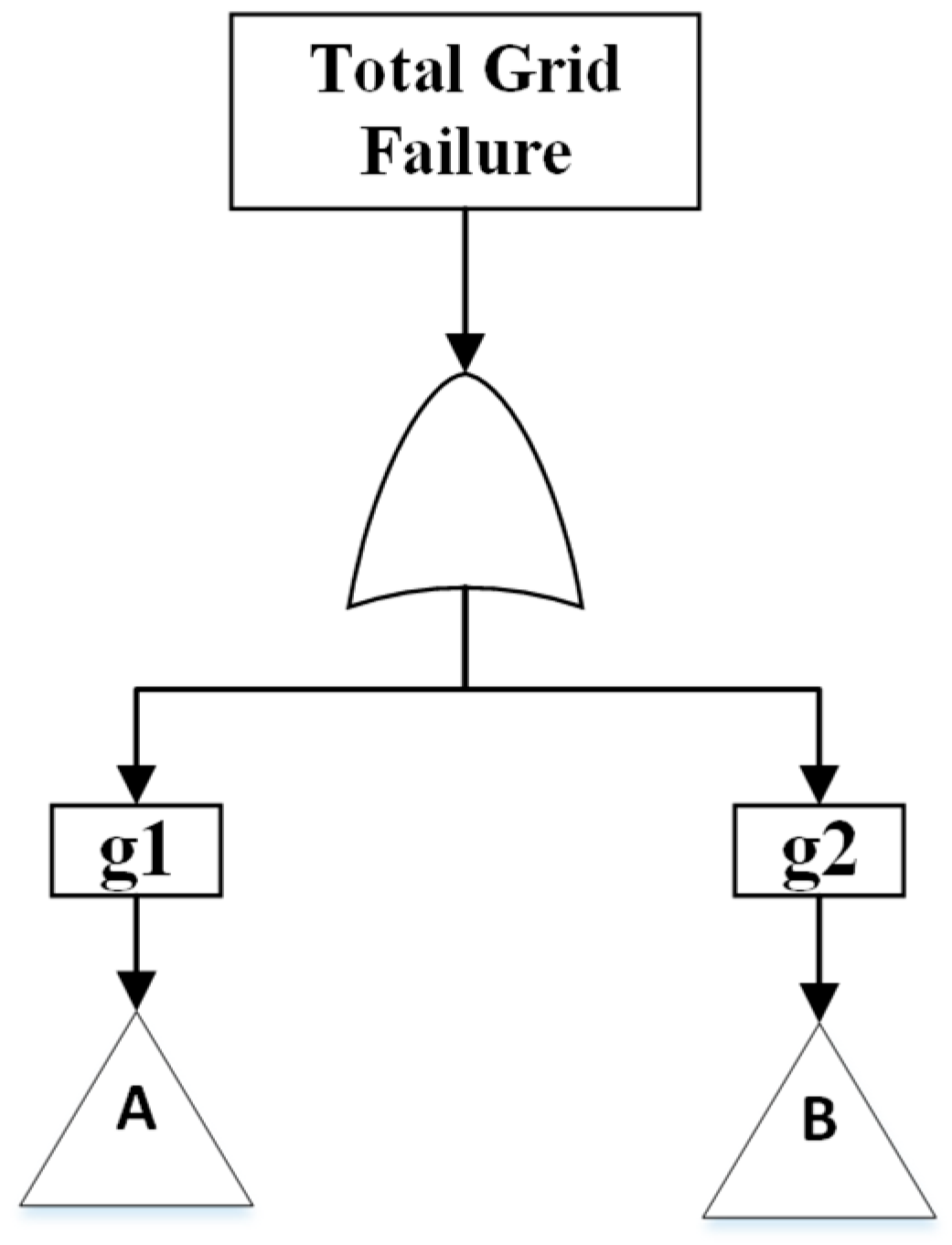

The top view of the FT model of the entire system considered in this work is shown in

Figure 2. The top event of this FT is the failure of the total system. The FT for the grid is divided into two major subsystems, namely, utility grid (g1) and microgrid (g2).

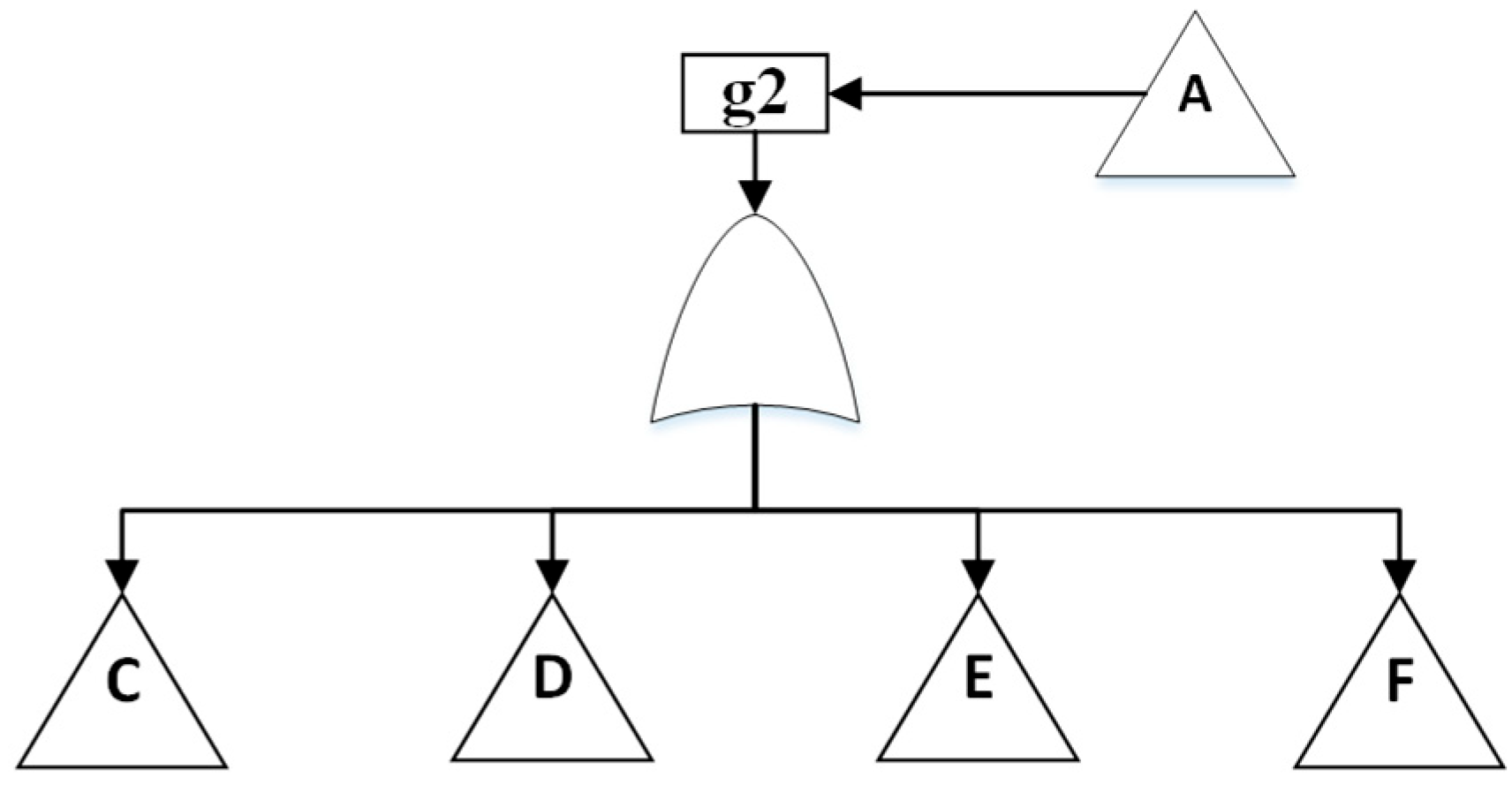

The proposed MG model (g2) has four subassemblies: PV farm (C), wind farm (D), BESS (E), and load (F), where C-F represent transfer trees derived from the fault tree. The top view of the MG FT model and its subassemblies is shown in

Figure 3.

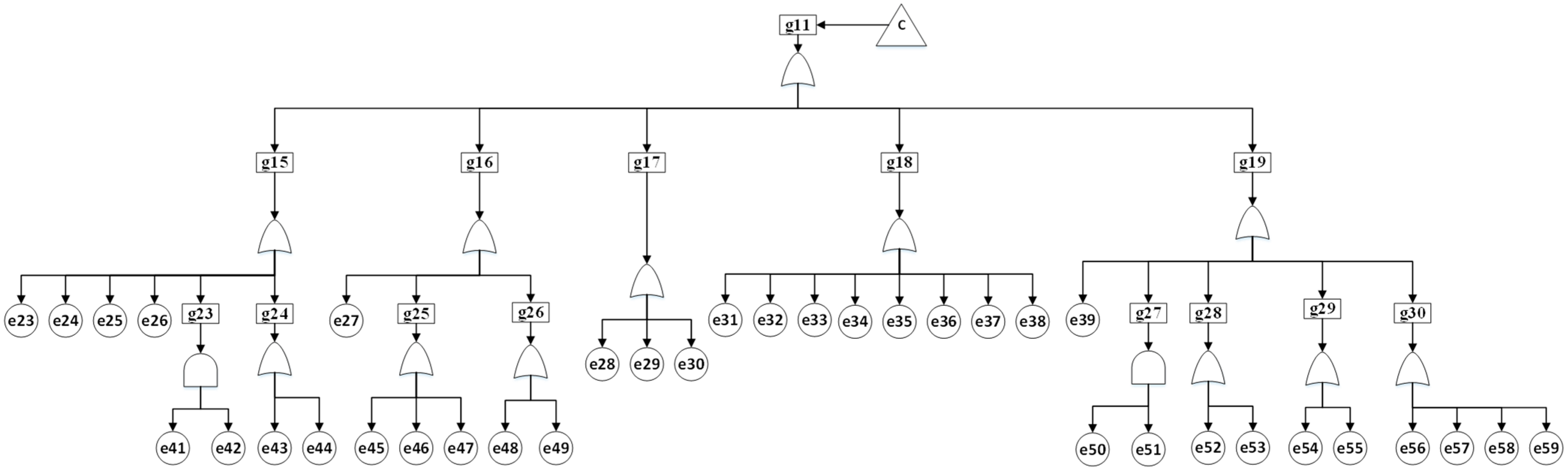

The PV system shown in transfer tree ‘C’ itself has five subassemblies (g15–g19), as depicted in

Figure 4. A detailed RAM (Reliability, Availability, and Maintainability) analysis was performed for PV systems in [

5]. However, based on the PV reliability block diagram in [

5] and drawing failure and repair rate data from [

2,

5,

20], a more comprehensive FT model of the PV farm is developed in the present work as shown in

Figure 4. The associated logic gate and basic event codes and their failure probability are shown in

Table 1 and

Table 2. Details of the PV module subsystems are as follows.

PV system operating life depends on the materials used and the manufacturing process. Therefore, it is important to model that dependency in reliability analysis. In the PV module subsystems, the basic event PV cell (g15) is based on the corrosion of the materials, which is one of the major factors influencing PV output. To model the degradation of the PV module due to temperature and insolation effects, the intermediate event external conditions (g23) is included. Other minor factors that can affect the PV output are Discoloration, By-Pass diode failure, Encapsulant failure, PV module open and short circuits, Hot-spot failure, and delamination. However, due to the lack of field data, these events or factors are not included in the PV FT model. However, as more data becomes available, this model can readily be updated and utilized.

FT model for the PV converter includes basic events like ‘PV converter (e27)’, which represents failure from improper manufacturing due to external factors like the improper arrangement and switching regulator.

Based on the architectural design, PV farms can have three inverter systems, namely central, micro, and string. To simplify the FT model in this study, the authors examined a central inverter system and discovered that the most critical component in the proposed MG model is the inverter cooling fan with a failure probability of 0.2597%. If unmonitored, a malfunction in this component can lead to failure of the PV inverter, which will eventually lead to the MG’s failure; therefore, a maintenance schedule must be rigorous.

The balance of system (BOS) generally includes all non-modular components of a PV system, including structural elements such as mounting and tracking systems, electrical infrastructure such as DC/AC cabling, and switchgear, as well as ancillary components like foundations, enclosures, monitoring equipment, and, in some cases, cooling or ventilation systems of the PV system and contributes to 10–50% of purchasing and installation costs. Failure of BOS non-modular components is responsible for the failure of 54% of the PV systems [

5]. So, it is extremely important that BOS be included as a part of the reliability analysis. The FT model of the BOS considered in this study is shown in subtree (g19). The proposed PV model is illustrated below in

Figure 4, and its associated logic gate and basic event codes, and their corresponding failure probability are shown in

Table 1 and

Table 2.

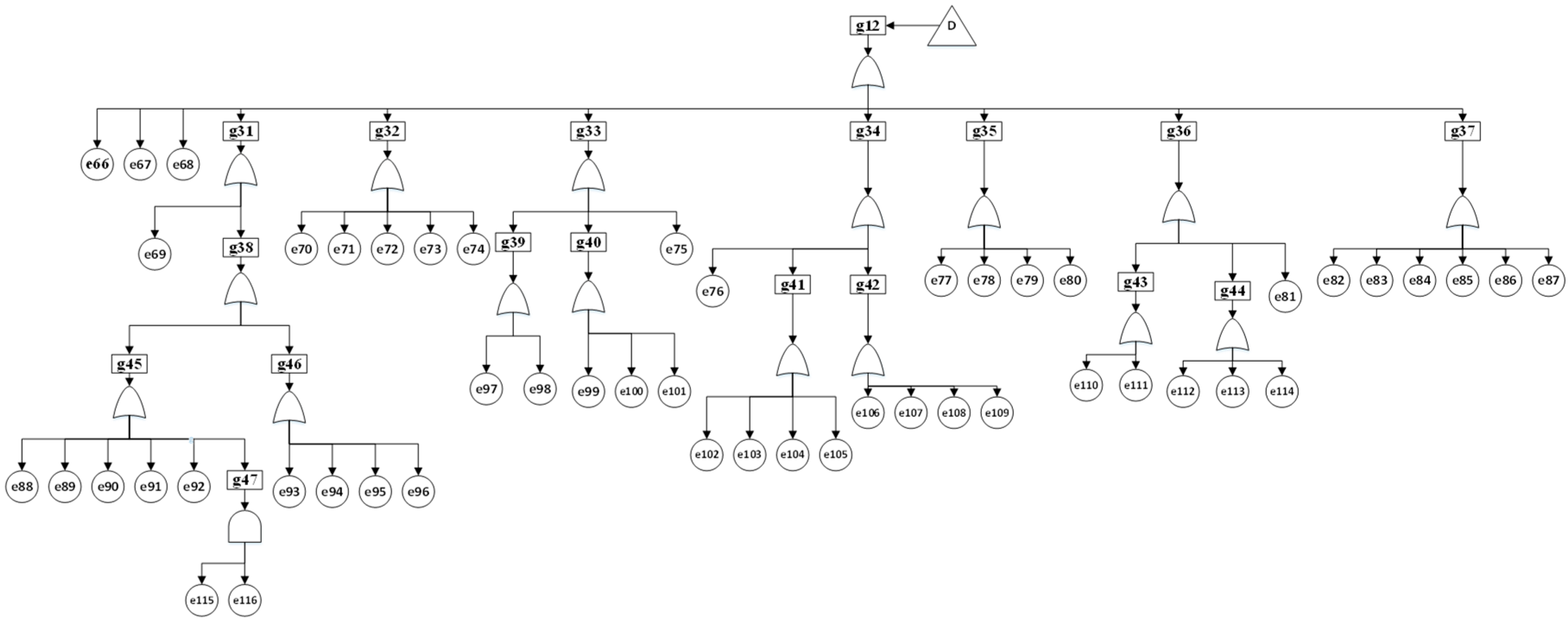

The wind turbine is the most installed RES in the world; the size and complexity of the WTs continue to grow. For failproof and cost-effective WTs operation, reliability assessment is an imperative technology. The FTA model for WT is developed with seven assemblies: generator (g31), support structure (g33), gearbox (g34), blades (g36, g44), control system (g46), hydraulic system (g35), and electrical components (g32). Failures in the WT can occur from electrical or mechanical causes; the model is developed using both physical and electronic components. The proposed WT model has seven subassemblies and three basic events. The proposed WT model is illustrated below in

Figure 5, and its associated logic gate, basic event codes, and their corresponding unavailability are shown in

Table 3 and

Table 4.

As stated, faults in WT generators can occur because of electrical or mechanical causes. Some of the most frequent events are open or short circuits in the stator or rotor winding, overheating, bearing failures from cracks or asymmetry, synchronization failures, accumulation of ice and dirt on blades, and manufacturing defects [

11]. As such, it is important to include these cases in the FT analysis. The WT generator FT model used in this study is shown as subtree g31, and the WT electronic component model is shown to be represented by g32.

From extreme weather conditions, manufacturing defects, fatigue, or corrosion, WT support structures and blades can fail, so they must be included in the reliability analysis. By considering weather conditions, an extensive FTA model is proposed in [

31] for the assessment of WT failure modes and their effects on public safety. For modeling purposes of this work, the WT support structures subsystem’s basic events are taken from [

31,

32]. To model the FT for WT blade failures, basic events and reliability data are drawn from [

10,

11,

31], and a simple model of that is presented in subtree g36.

The gearbox is another most vulnerable component in a WT. Gearbox failure has been extensively studied and documented because it can lead to considerable turbine downtimes and unplanned maintenance issues, increasing electricity costs. The most probable causes for WT gearbox failures are wear and tear, fatigue, corrosion, abrasion, design defect, excessive pressure, and degradation. A simple FT model for WT gearbox failure is shown in subtree g34. Simple FT models for the WT hydraulic system failure are shown in g35, and the WT control system is shown in g37. Basic events and failure data for these models are drawn from [

8,

10,

13,

32,

33].

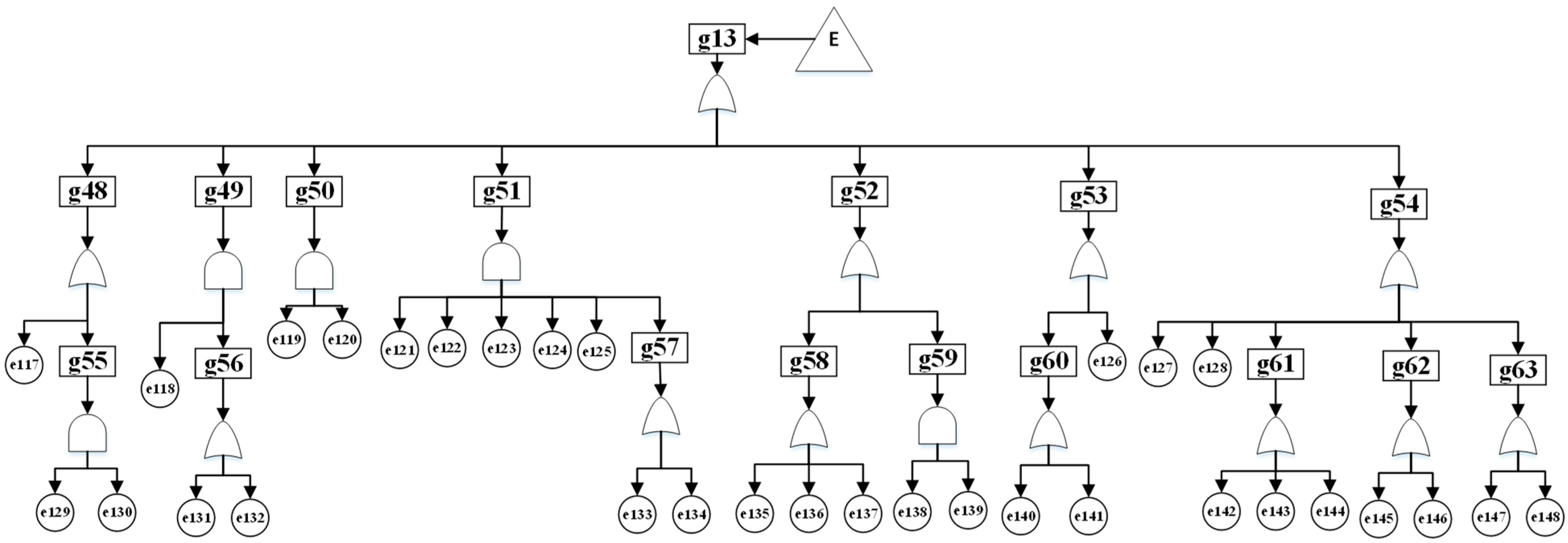

To reduce intermittency from the RES and provide ancillary services to MG and UG, BESS is included. Little to no work went into the reliability analysis of the energy storage, which typically involves Li-ion batteries in MGs. To build the FT model for the BESS basic events, failure, and repair rate data are taken from [

17,

18,

34,

35]. There are seven subtree events in the BESS FT model. The proposed FTA model for the BESS is illustrated in

Figure 6, and its associated logic gate, basic event codes, and their corresponding failure probabilities are shown in

Table 5 and

Table 6.

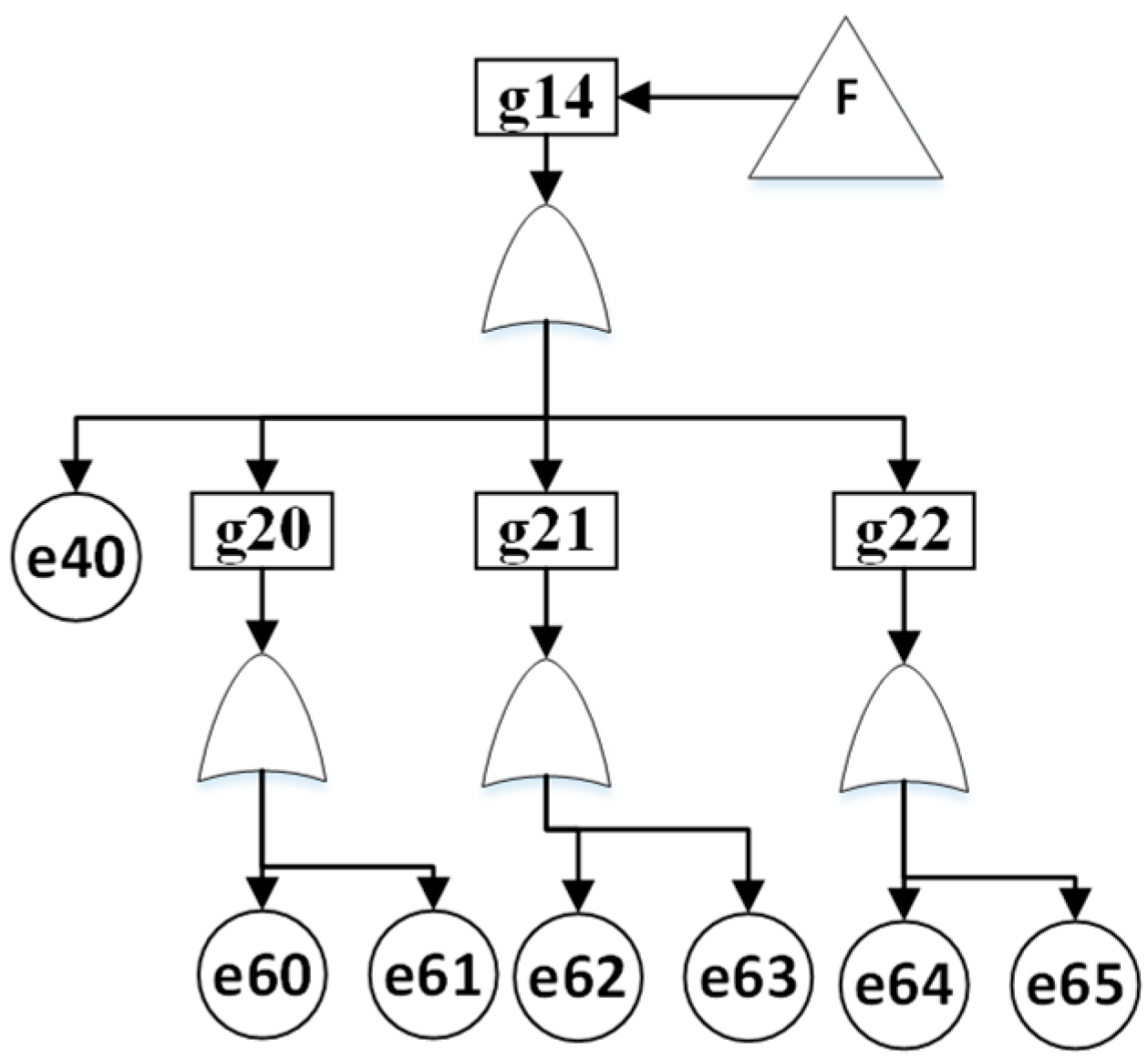

A simple load FTA model is presented in

Figure 7. The associated basic event and logic gate codes and failure probability are shown in

Table 7 and

Table 8.

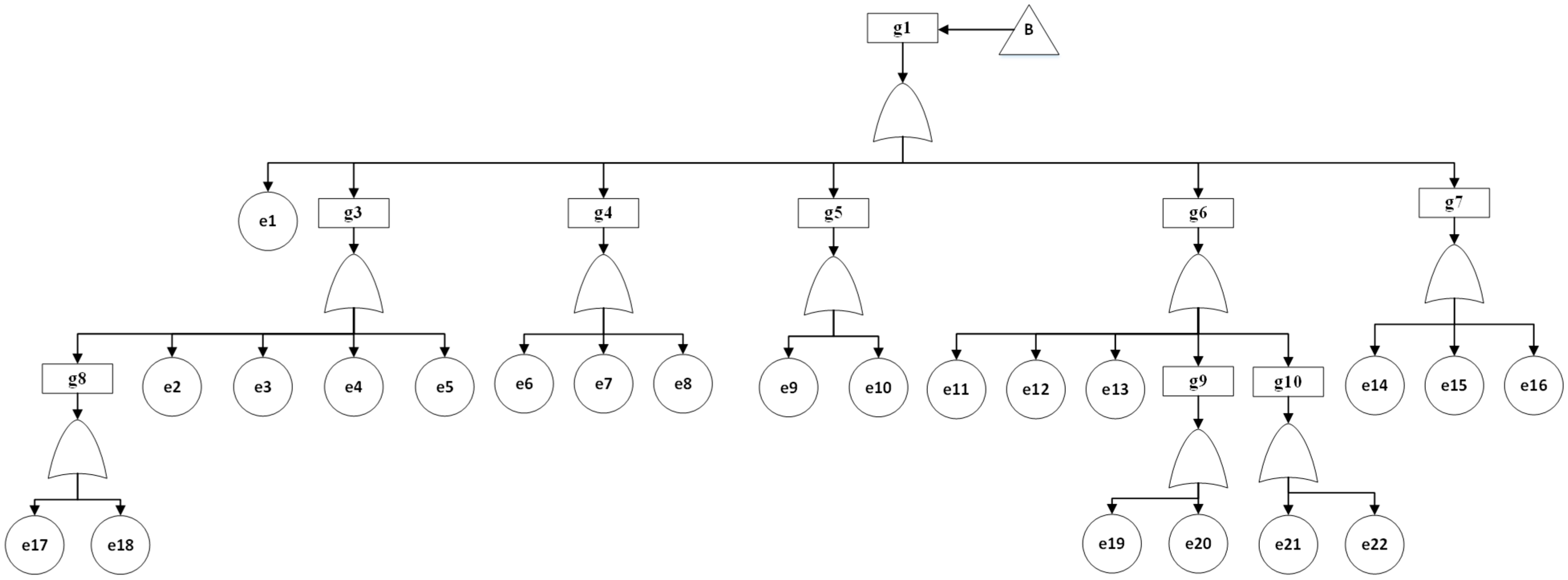

Previous peer-reviewed literature has determined that the conventional power grid has been extensively studied using FTA. Failure occurrence is rare in distribution systems; in this study, a simple FT model for the utility grid’s distribution end is developed. Authors of the present work used a methodology similar to previous models. The proposed utility grid FT model has five intermediate events and one basic event as shown in

Figure 8. Specifically, the FT models for UG transformers (g3), natural (e7) and manmade events (e6), transmission lines (g5), switchgear equipment (g6), and other key components like capacitor banks (e15) and voltage regulators (e16) are included in the model as shown in

Figure 8. Basic events and parameter data for this reliability evaluation of the utility grid are drawn from [

20,

21,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40]. The associated basic events and logic gate codes with their failure probability are shown in

Table 9 and

Table 10.

6. Analysis and Discussion

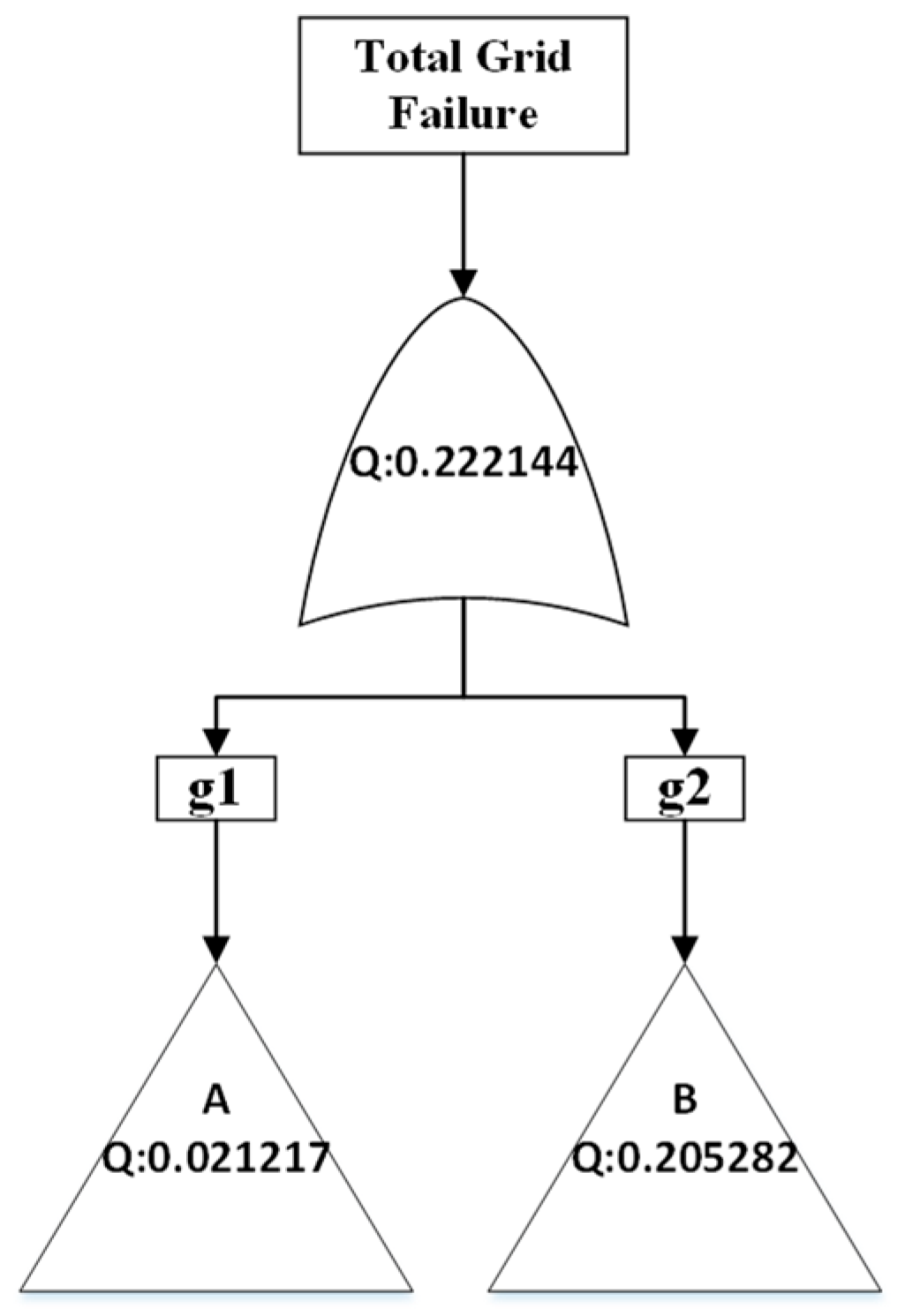

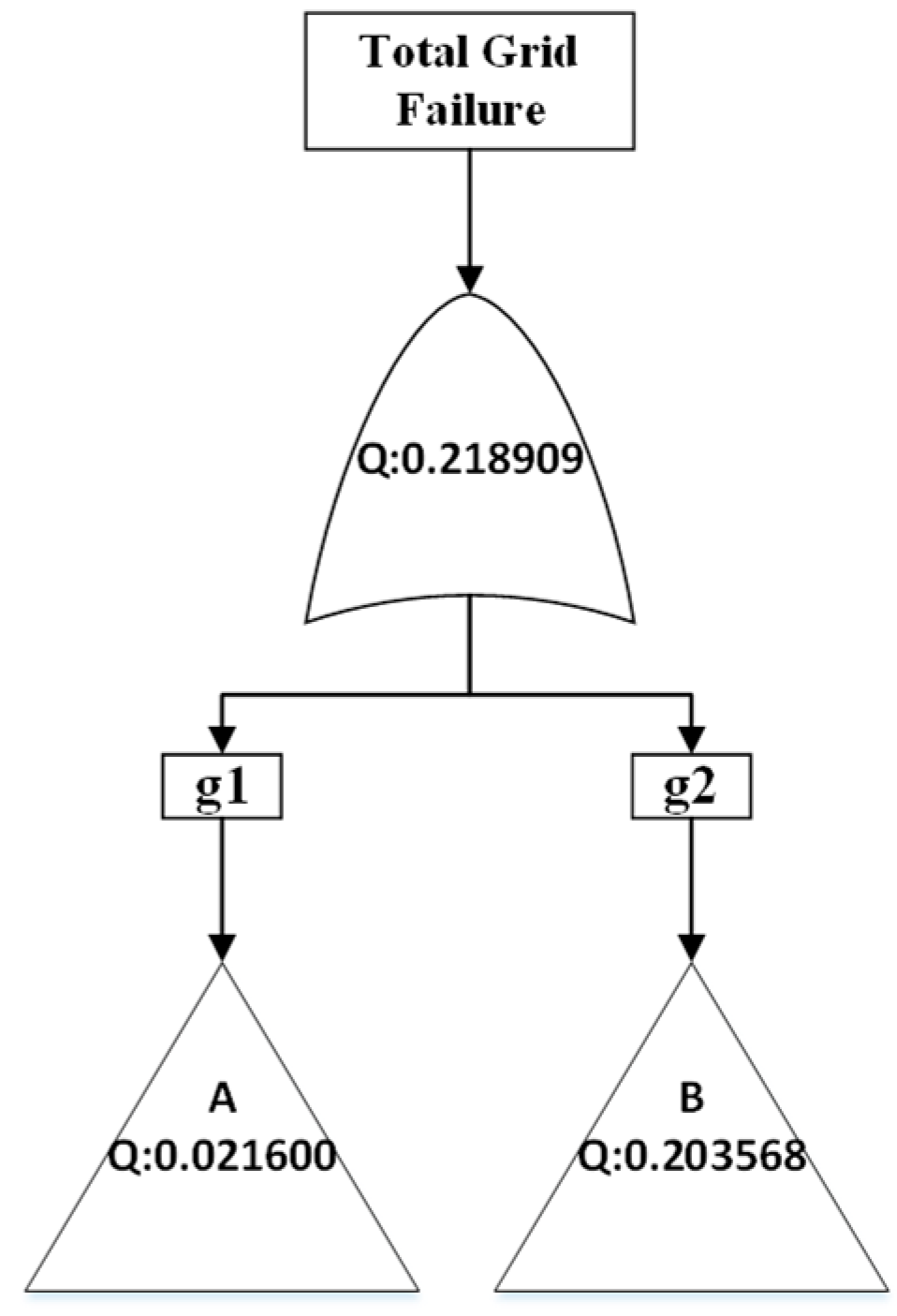

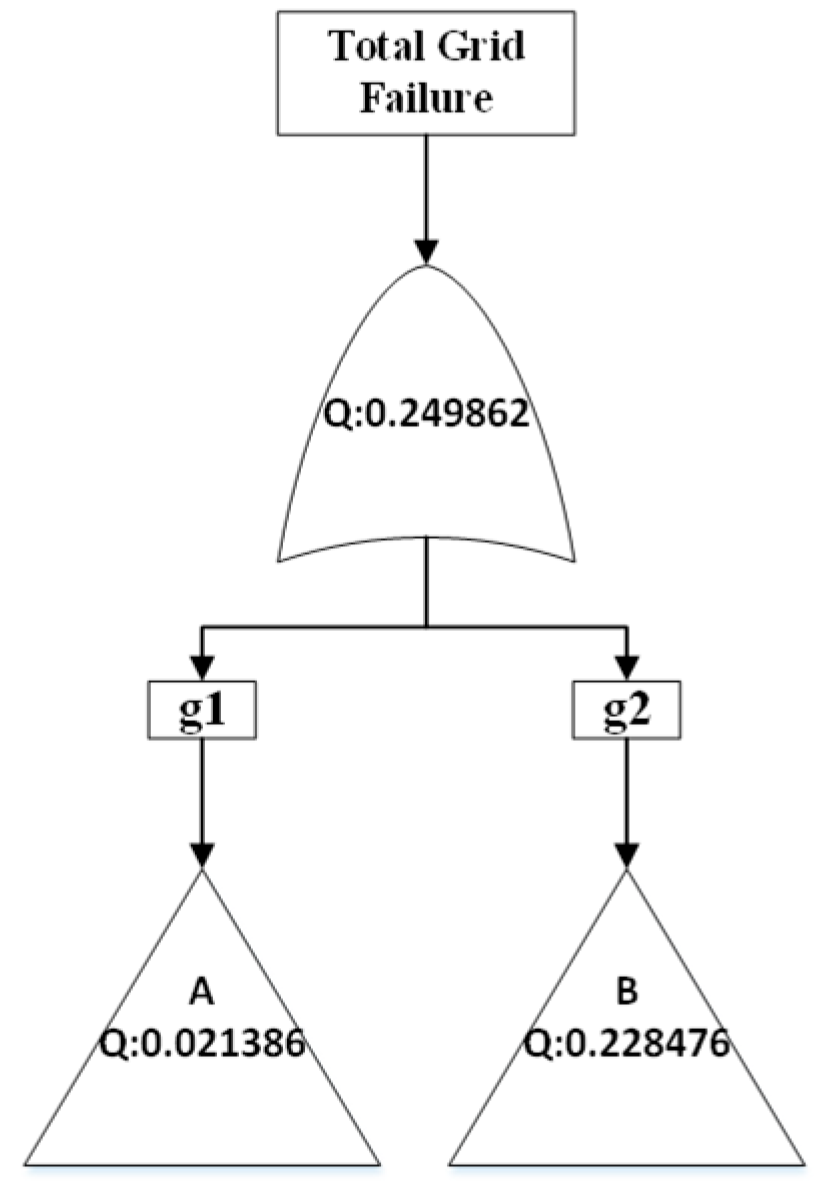

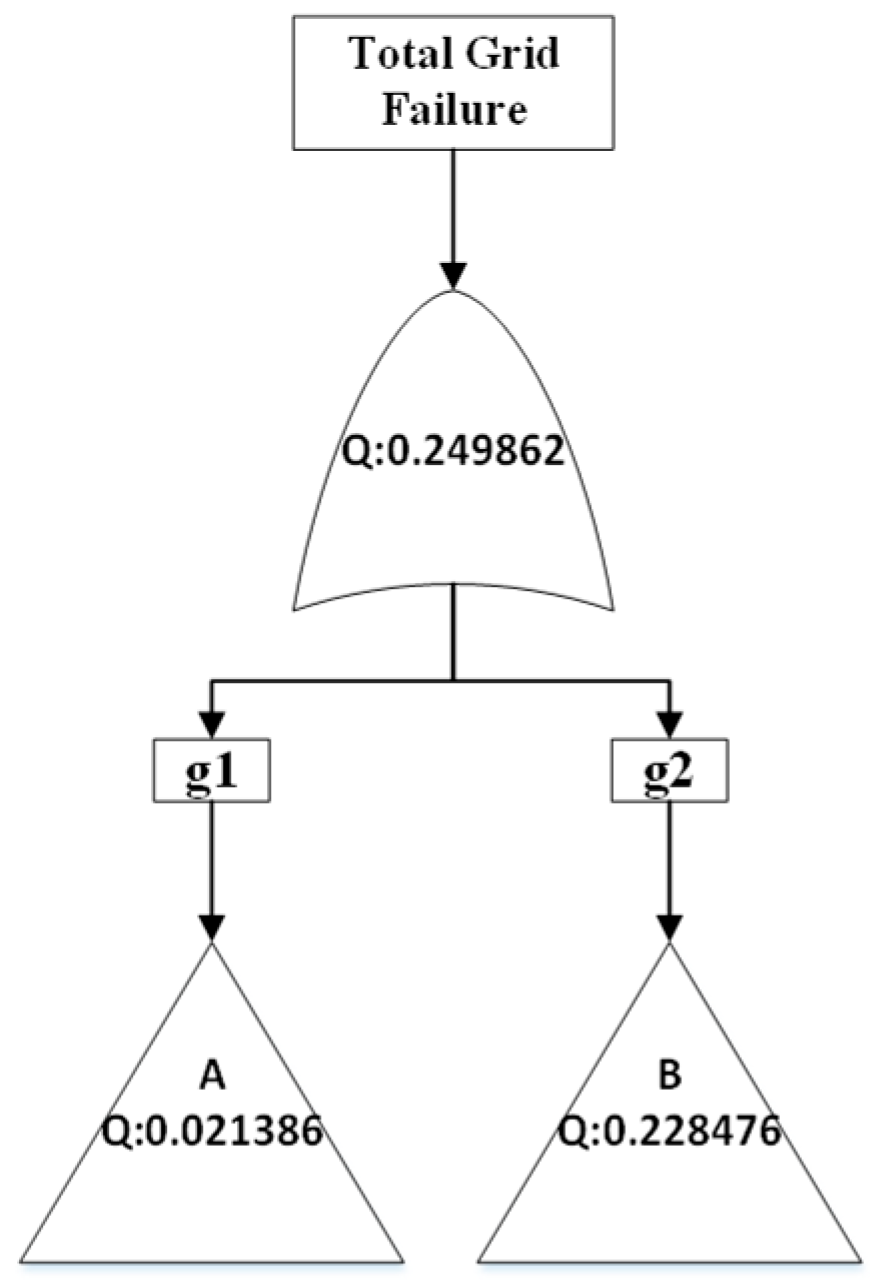

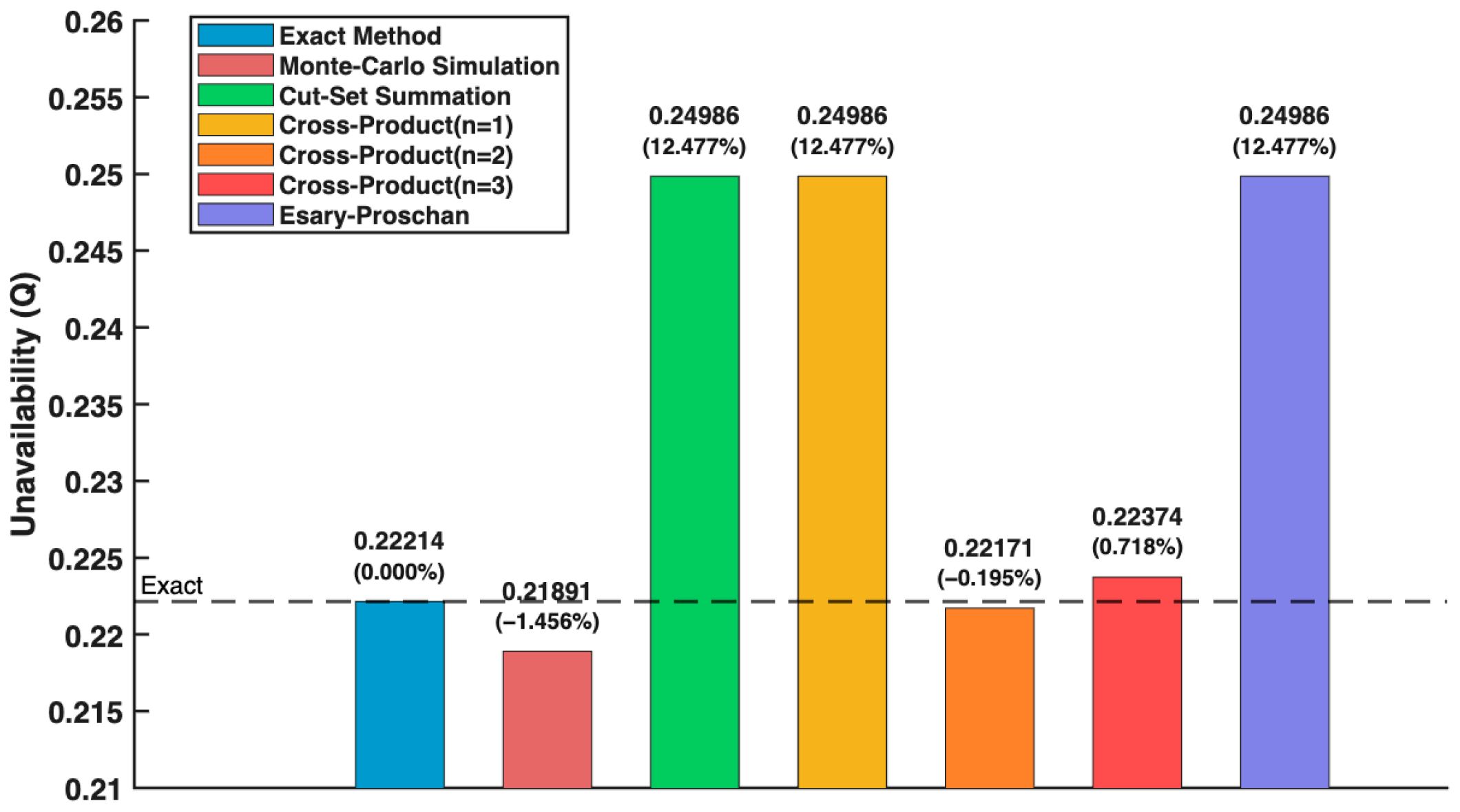

The probability of total system failure was calculated using different methods. As shown in

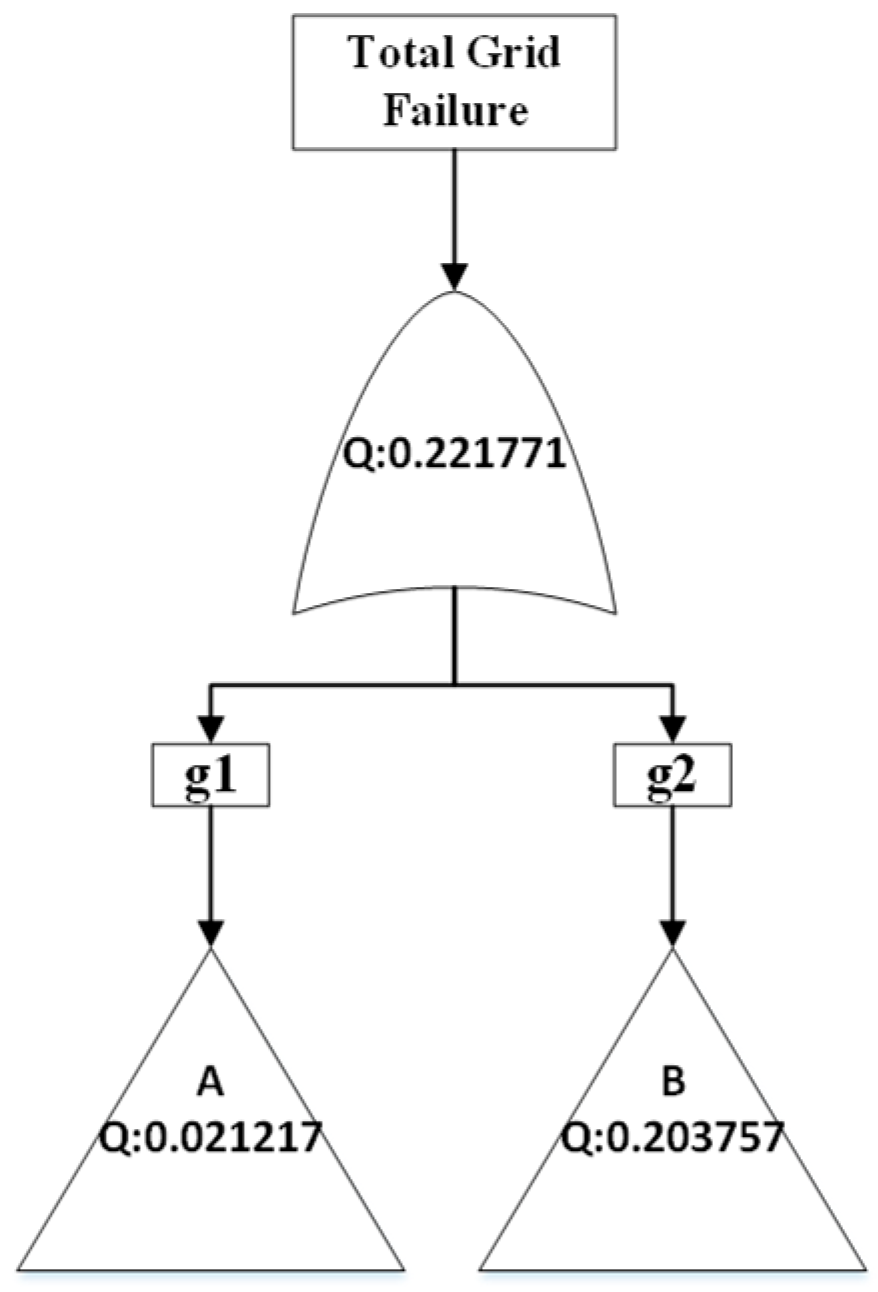

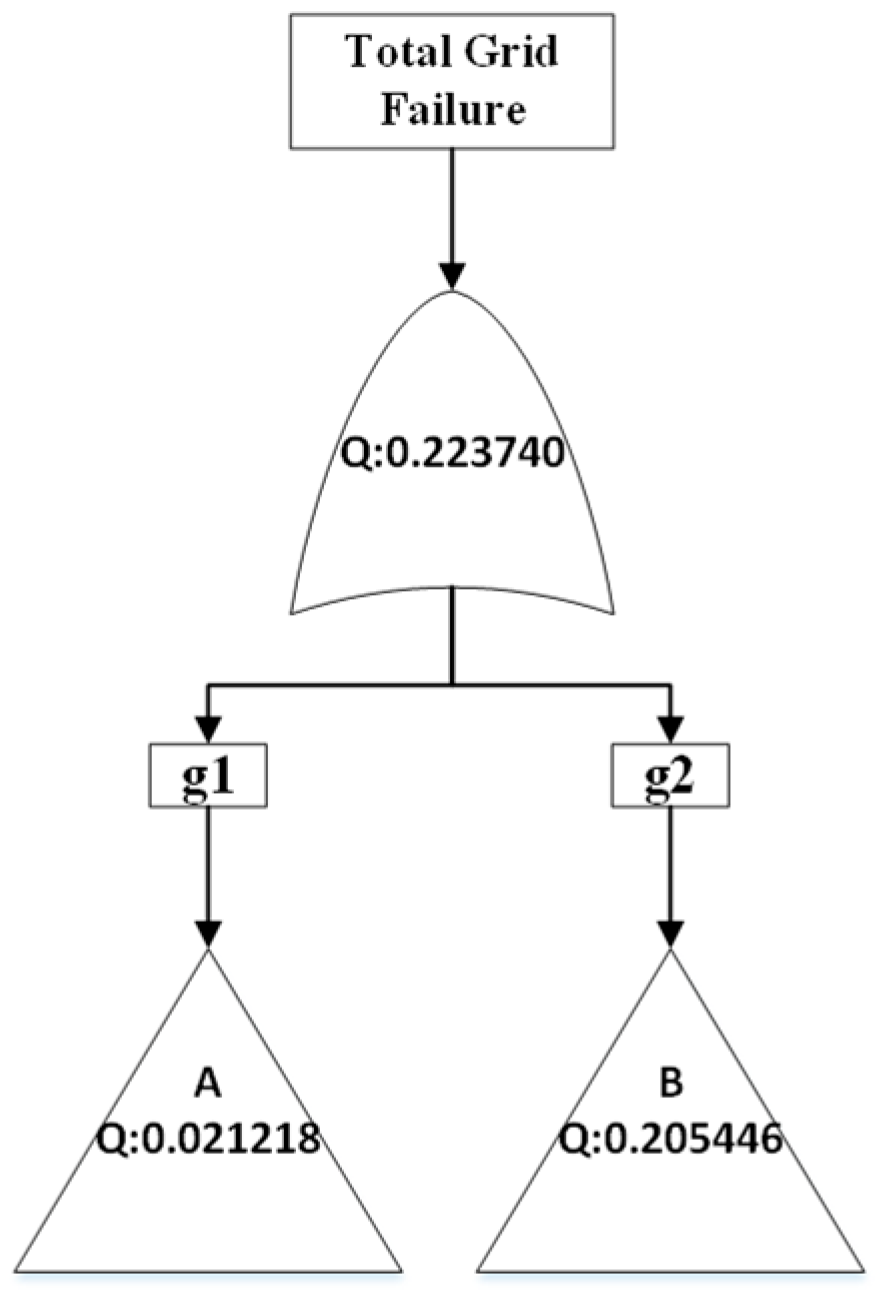

Figure 19, results are largely consistent across all methods and align with theoretical expectations discussed previously. The exact method serves as the baseline for comparison (Q = 0.22214) of all other methods. The Monte Carlo simulation results closely match those of the exact method, with a value of Q = 0.21891, deviating by only −1.456%, confirming that the stochastic simulation can be effectively used to calculate system reliability metrics for the system considered in this work. As previously discussed, exact and Monte Carlo simulation methods are extensively used in FT analysis. These methods are robust, but can be computationally intensive, especially for a complex system like MG, which has several independent events from different renewable sources.

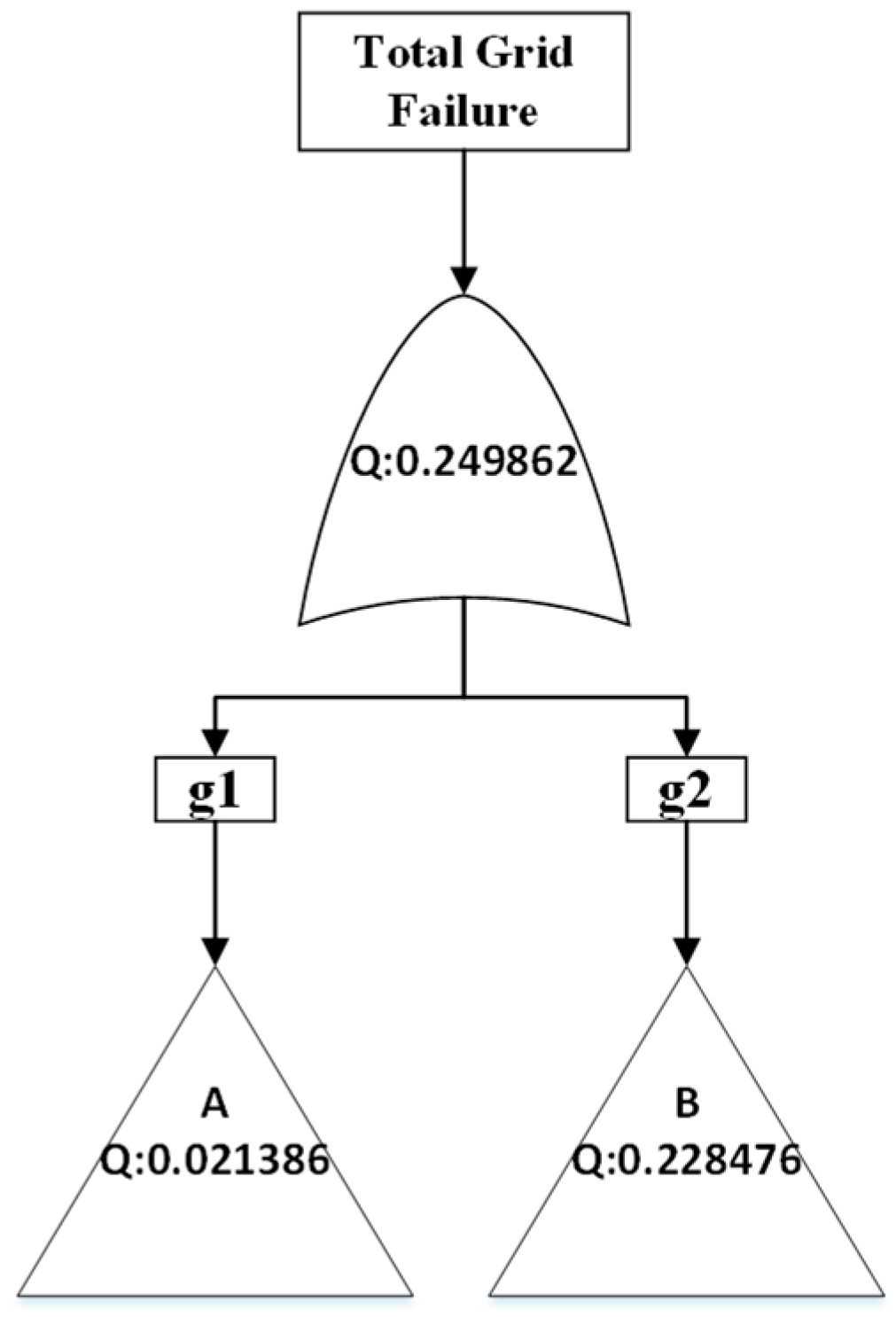

Cut-set approximation methods provide faster alternatives while offering results within valid ranges. The CSS method in this case yields a failure probability of 0.24986, representing a +12.477% deviation from the base case. This is expected, as the CSS method uses the first sum from Equation (1). The CSS method is the fastest of the approximation methods, but it is also the most inaccurate and provides an upper bound for the failure probability of the top gate.

The cross-product approximation method for n = 1 results is the same as the CSS method, which matches the theoretical descriptions discussed above. For instance, n = 2 produced Q = 0.22171 (deviation of −0.195% from exact method), and n = 3 produced Q = 0.22374 (deviation of +0.718%). These values are in proximity to the exact method, thus proving to be efficient alternatives for large fault trees.

Both the CSS and Esary–Proschan methods yielded identical results because MG’s FT cut-sets are mutually exclusive (they share no common components), and the rare-event approximation ensures that the higher-order intersection terms in the inclusion–exclusion expansion contribute insignificantly. So, Esary–Proschan’s expression simplifies the CSS method.

Flexibility to choose between multiple methods is essential for MG operators, as the size and complexity of FT’s vary widely and the morel complexity can vary substantially across systems and operating conditions. The exact method remains the benchmark for verifying approximation methods, but it may become computationally intractable for larger systems due to cut-set interactions, so it is most suitable for small-to-moderate FTs where the number of events or cut-sets is manageable. The EP method provides a computationally efficient solution for identifying dominant vulnerabilities in the system, such as points of failure at point of common coupling or primary distribution transformers. This method is effective when the top event of the FT (loss of power to critical loads) can be represented through a coherent and monotone structure dominated by OR gates and the objective is to obtain conservative bounds with moderate computational effort. The CSS method is recommended when minimal cut-sets can be identified and the overlap remains manageable. CSS provides higher accuracy when compared to first-order approximations and is effective for grid-tied MGs where minimal structural vulnerabilities drive the top event. The CP method is recommended when minimal cut-sets are available, cut-set overlaps are non-negligible, and full inclusion–exclusion principle to all orders is computationally expensive. High renewable energy systems introduce stochastic intermittency and time-dependent constraints, such as the State-of-Charge for BESS, and non-exponential failure distributions and environmental correlations (e.g., solar irradiance). The Monte Carlo simulation method is an indispensable tool to represent these effects because it can track chronological operations and accommodate arbitrary failure distributions or correlated environmental scenarios. While the computational overhead of the Monte Carlo simulation method is higher than that of analytical counterparts, it offers a level of operational realism that is otherwise unattainable. For MG owners, the choice to use the Monte Carlo simulation method represents a pragmatic trade-off: accepting a higher computational cost in exchange for the modeling fidelity required to manage the dynamic nature of modern renewable configurations.

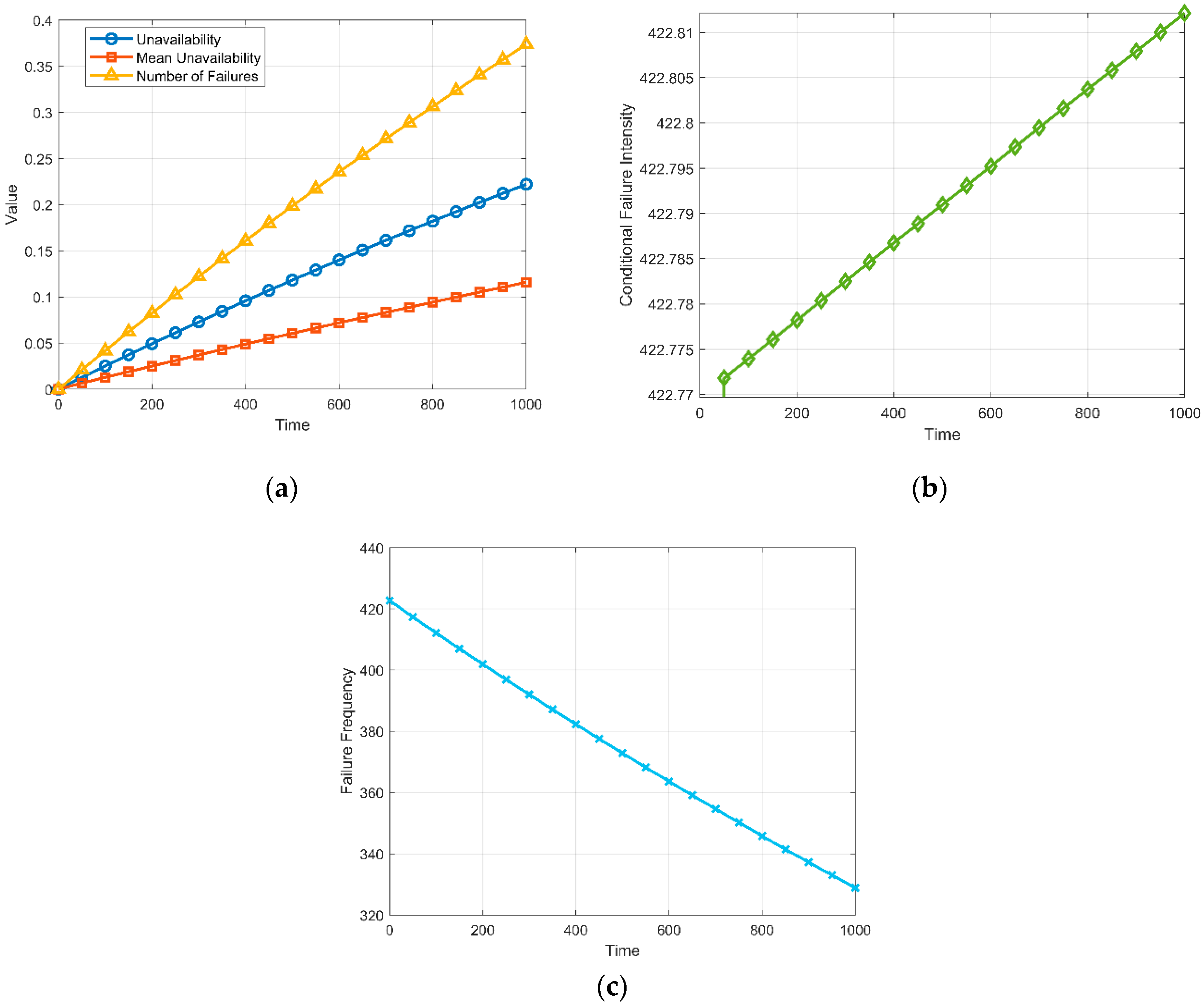

Availability metrics plotted in

Figure 16a exhibit a steady increasing trend over time, which is consistent with the reliability theory. These trends validate the expected degradation of system reliability with operating time. The CIF (

Figure 16b) remains almost constant around 422.77–422.81 with a slight upward variation, which is the typical expected trend for FT’s modeled under rare-event exponential failure distributions. The failure frequency (

Figure 16c) shows a decreasing trend (422.77 to 328.89) over the simulated duration. The observed trend is consistent with the theoretical assumptions, as time progresses, fewer working components remain to contribute to new failures, reducing the failure frequency.

Reliability indices, such as SAIFI (System Average Interruption Frequency Index), SAIDI (System Average Interruption Duration Index), and CAIDI (Customer Average Interruption Duration Index), are well-documented in MG reliability studies. These indices are system-level and customer-focused, so they provide no insight into the contribution of individual components to overall unreliability. By contrast, the importance measures proposed in this work quantify the sensitivity of the system’s probability of failure to changes in the reliability of specific components. This is particularly important for MG operators, as the proposed measures in this work will enable them to identify internal vulnerabilities and optimize their maintenance schedules, thereby enhancing MG reliability.

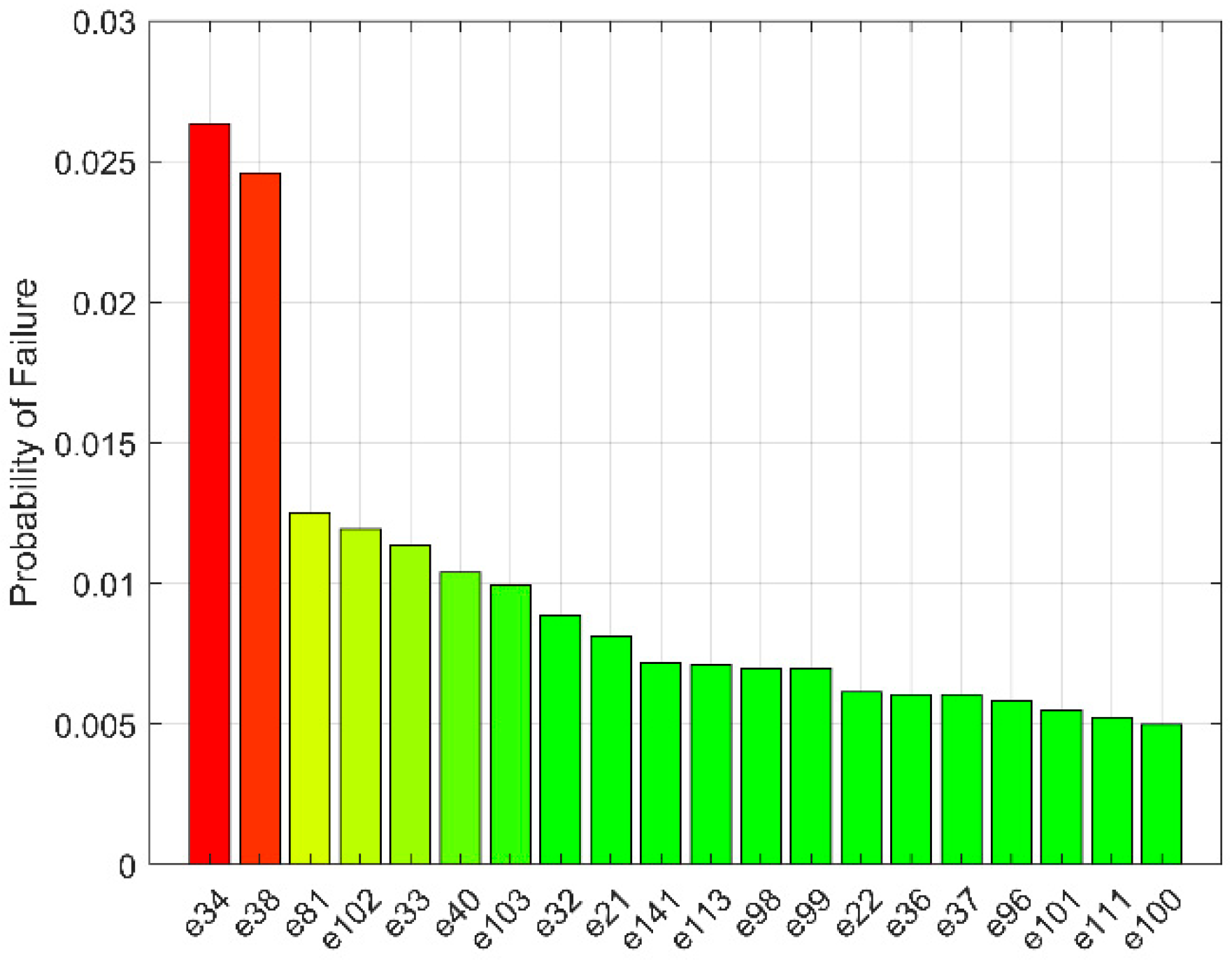

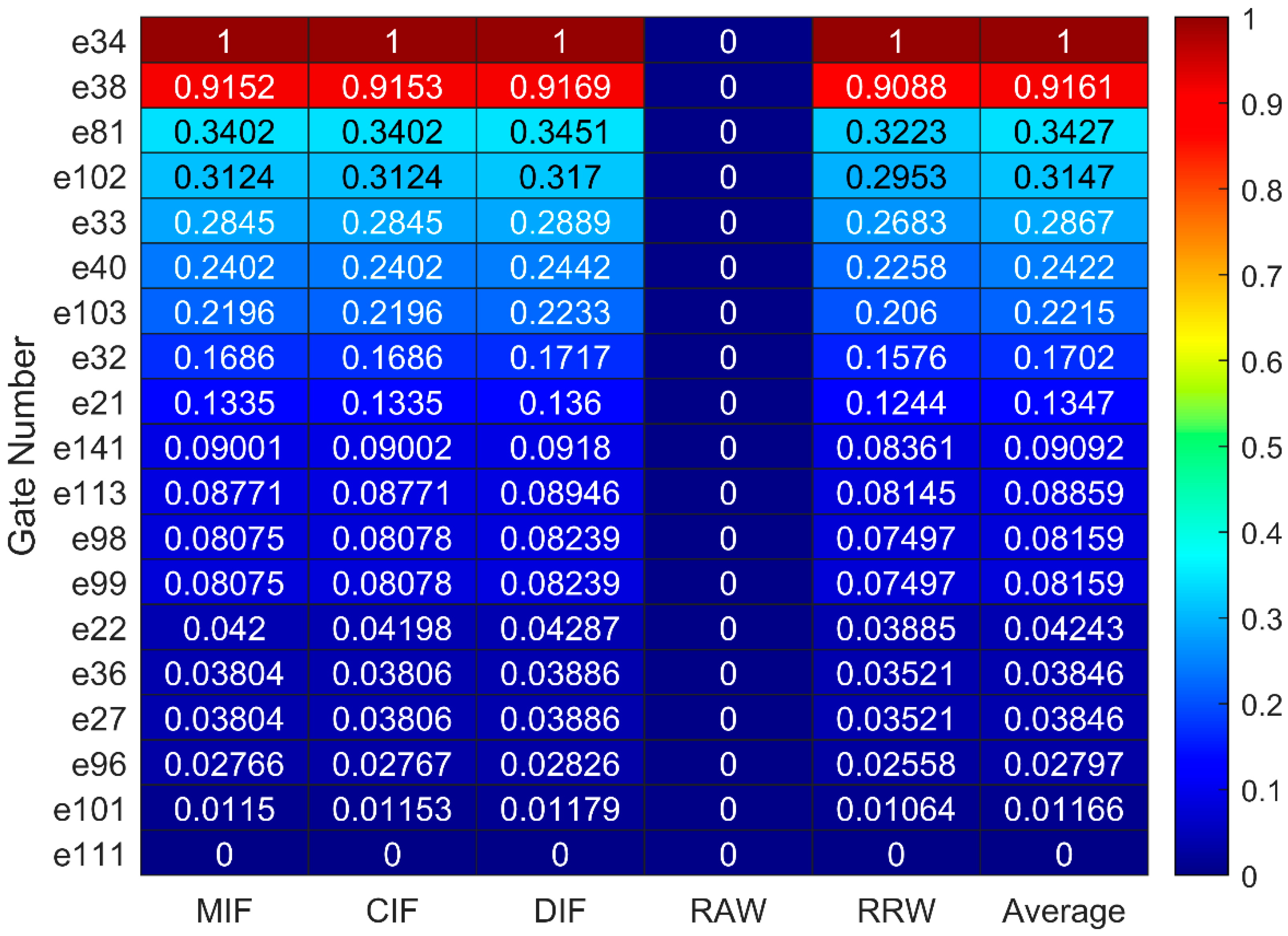

Figure 18 presents the normalized heatmap of the calculated importance measured for the top 20 events in the MG FT. Consistent results between the cut-set probabilities presented in

Figure 17 and the calculated importance measures provide strong validation of the results. The same events, such as e34, e38, e81, e102, and e33, emerge as most significant when evaluated for cut-set probabilities and importance measures. This confirms that the importance measures used in this work effectively capture the component-level vulnerabilities in the system. A large subset of dominant events exhibits the same value for RAW (4.501591), because the failure of each component is assumed to lead to the same single, critical top event (total system failure). This trend is expected given the tree structure is dominated by OR-gate logic, where the failure of a basic event directly propagates through the OR structure forcing the occurrence of top event with certainty, i.e.,

, which yields

yielding identical RAW values for the dominant events. In contrast, events located within subsystems connected through AND-gate logic do not force the top event with certainty, so RAW value deviates from the dominant event value. For instance, PV DC switch (e50) yields a RAW value of 2.359441, while weaker contributors approach a value of 1.0. To visualize the impact of the measures, a heatmap is presented in

Figure 18, with normalized values (where the normalization scales for each measure range from 0 to 1) making the results comparable despite differences in magnitude. It helps the operators to identify the most vulnerable components without distortion from scale differences.

Combined, the results from the proposed system offer a comprehensive and reliable approach for MG reliability assessment. By integrating multiple methods so that operators can choose an appropriate method based on FT size, availability metrics, and importance measures, providing component-level insights, this work proposes a robust methodology that balances computational efficiency with accuracy, providing MG operators with a flexible and practical reliability toolkit for safe and reliable operation.