CharSPBench: An Interaction-Aware Micro-Architecture Characterization Framework for Smartphone Benchmarks

Abstract

1. Introduction

- CharSPBench is proposed as an interpretable micro-architecture bottleneck characterization framework for interaction-driven mobile workloads, addressing the limited applicability of existing analysis methods under realistic user interaction scenarios.

- An Intensity-Level Characterization (ILC) method is introduced to enable intensity-aware workload characterization across different benchmarks and interaction scenarios, facilitating the identification of dominant execution tendencies such as memory-intensive and frontend-bound behavior.

- A systematic micro-architecture analysis is conducted on multiple commercial mobile processor platforms under representative interaction scenarios, including sliding, switching, and quenching, from which eight representative micro-architecture performance insights are distilled.

2. Related Work

| Feature Sel. | Arch. Interp. | Fine-Grained Char. | Mobile-Aware | Interaction-Aware | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weingarten [14] | × | ✓ | × | × | × |

| Jang [16] | ✓ | ✓ | × | × | × |

| Criswell [19] | ✓ | × | ✓ | × | × |

| Li [27] | ✓ | × | × | × | × |

| Bai [17] | ✓ | ✓ | × | × | × |

| Wang [20] | ✓ | × | × | × | × |

| Bai [18] | ✓ | ✓ | × | × | × |

| Schall [21] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | × | × |

| CharSPBench | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

3. Background and Motivation

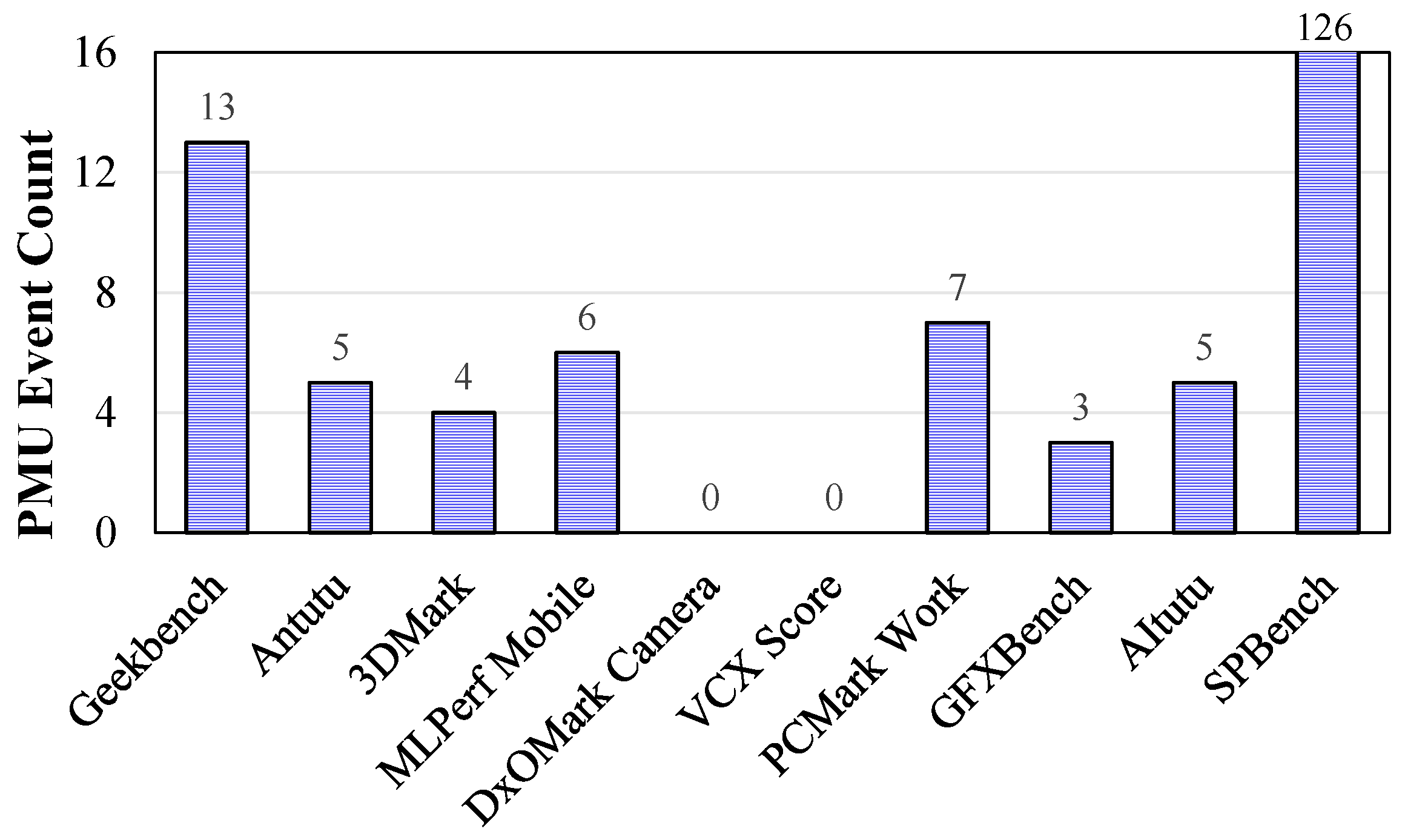

3.1. SPBench Overview

3.2. Algorithms Used in This Study

3.2.1. Stochastic Gradient Boosting Regression Trees

3.2.2. Z-Score Normalization

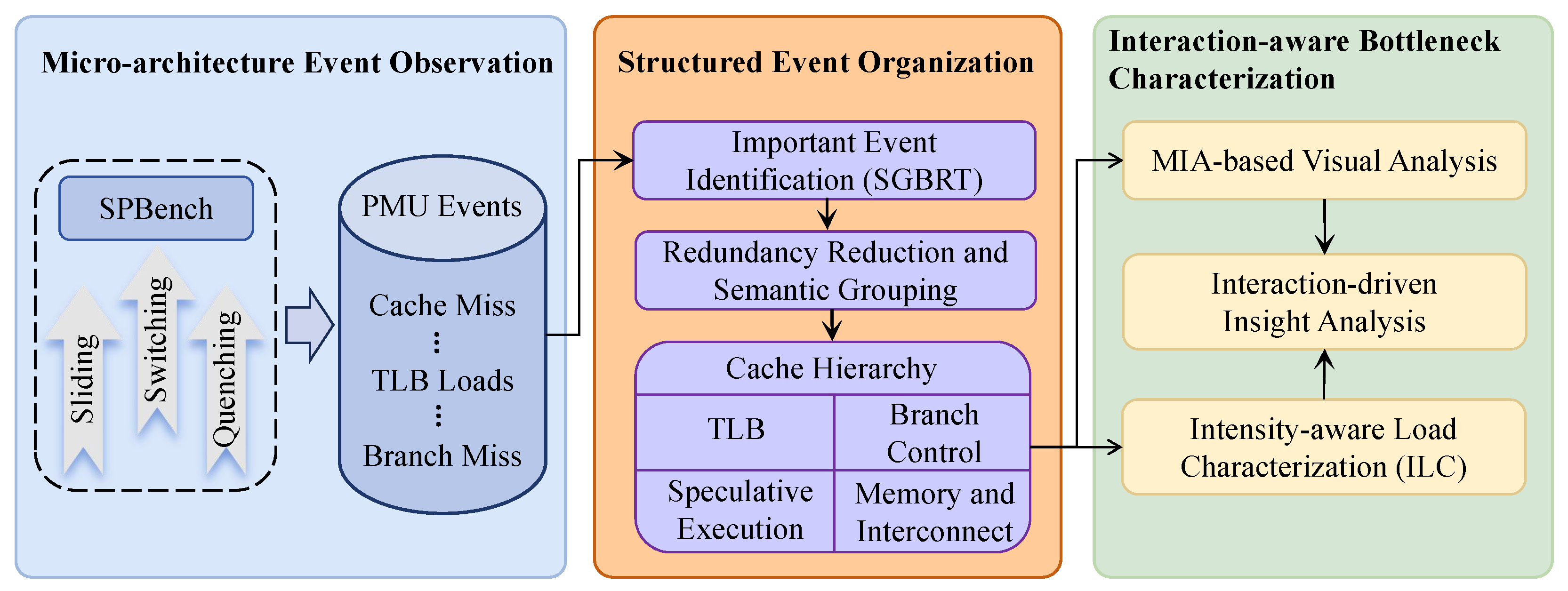

4. CharSPBench Methodology

4.1. Interaction-Driven Micro-Architecture Event Modeling and Structuring

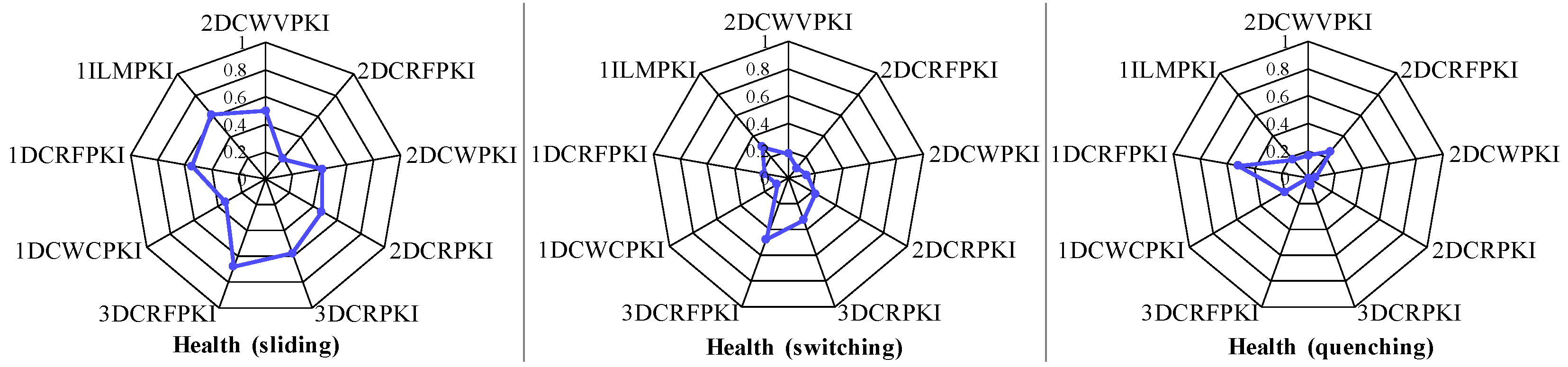

4.2. MIA-Based Analysis Procedure for Mobile Micro-Architecture

4.3. Intensity-Aware Load Characterization (ILC)

5. Experimental Setup

6. Results and Analysis

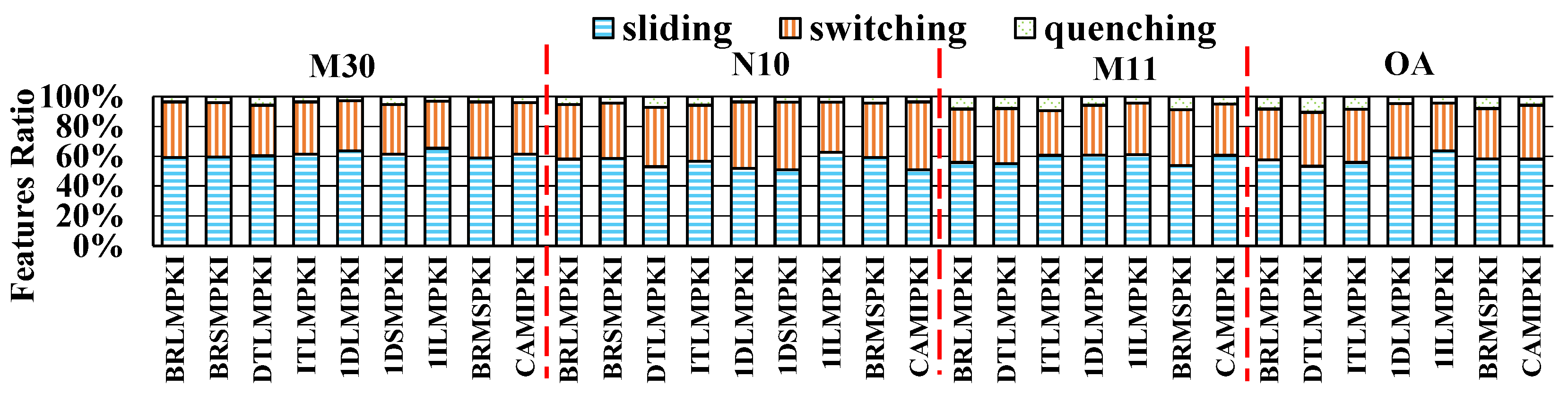

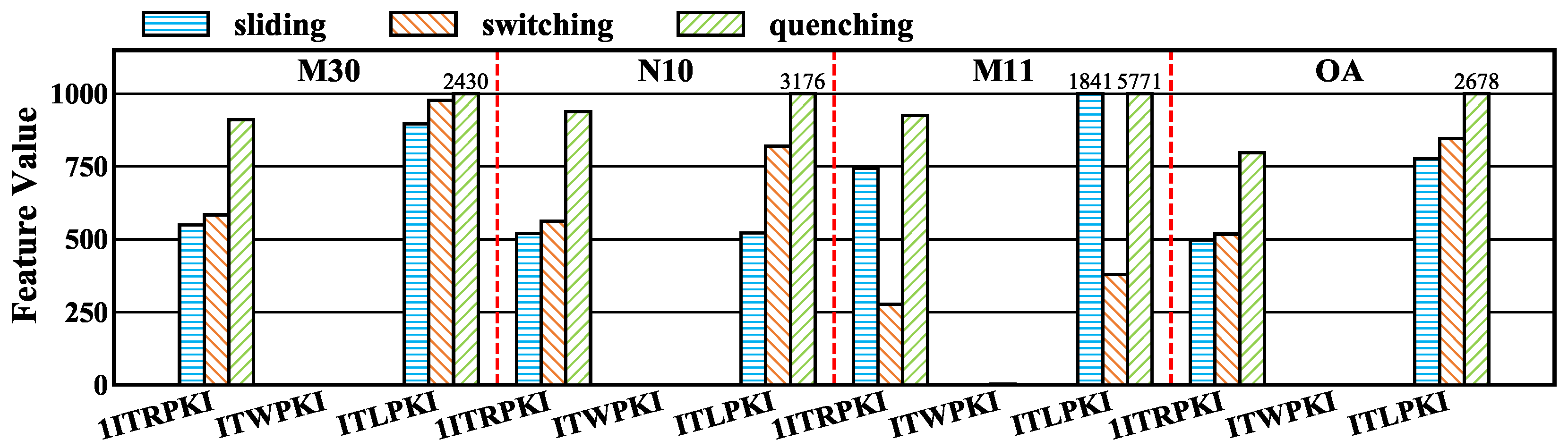

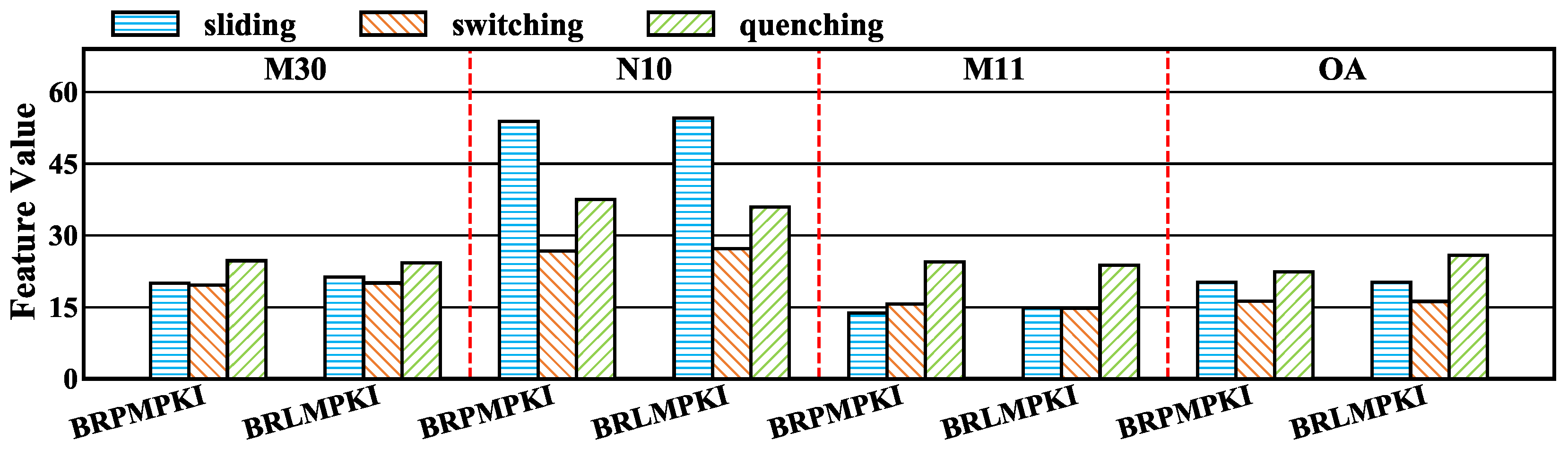

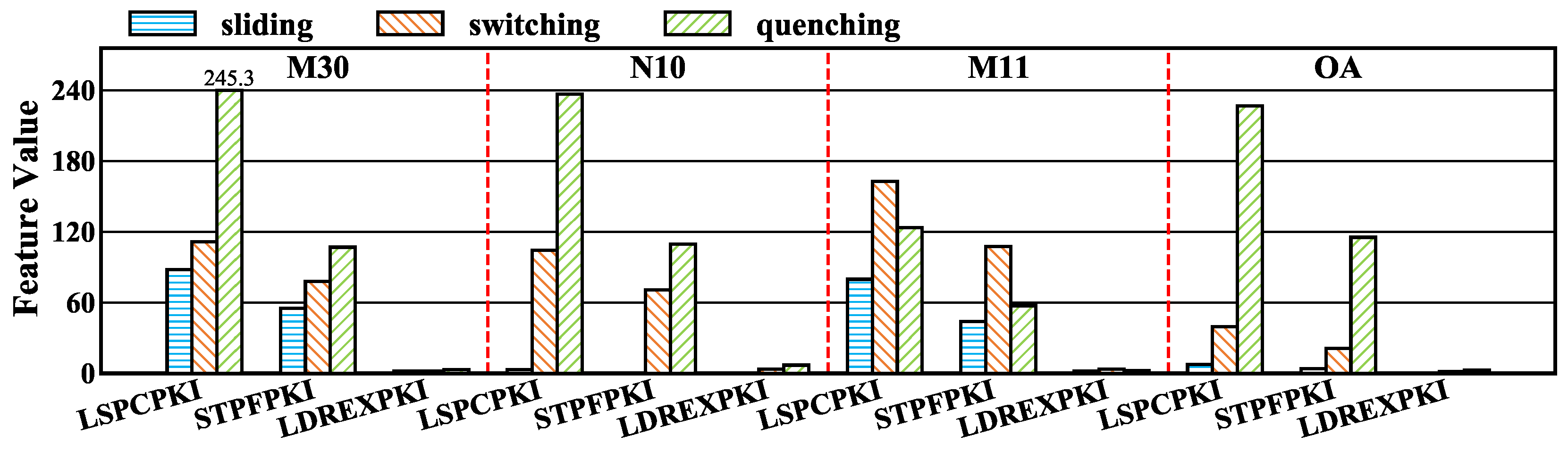

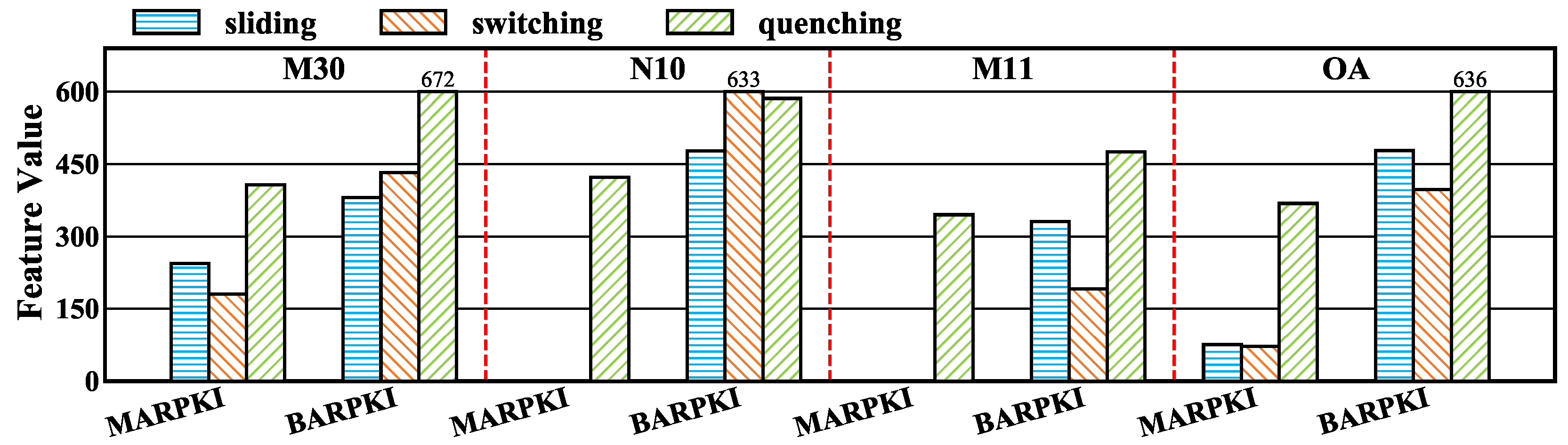

6.1. Preliminary Analysis of Interaction-Driven Miss-Related Features

6.2. Semantic Grouping and Redundancy Reduction of Important Micro-Architecture Features

6.3. Intensity Profiling of SPBench Benchmarks

6.4. Discussion of Implications

7. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ouyang, C.; Xin, J.; Zeng, S.; Li, G.; Li, J.; Yu, Z. Constructing a Supplementary Benchmark Suite to Represent Android Applications with User Interactions by using Performance Counters. ACM Trans. Archit. Code Optim. 2025, 22, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesavan, R.; Gay, D.; Thevessen, D.; Shah, J.; Mohan, C. Firestore: The nosql serverless database for the application developer. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 39th International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE), Anaheim, CA, USA, 3–7 April 2023; pp. 3376–3388. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Xia, T.; Wang, H.; Tu, Z.; Tarkoma, S.; Han, Z.; Hui, P. Smartphone app usage analysis: Datasets, methods, and applications. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2022, 24, 937–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hort, M.; Kechagia, M.; Sarro, F.; Harman, M. A survey of performance optimization for mobile applications. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2021, 48, 2879–2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Zhu, Y. Pes: Proactive event scheduling for responsive and energy-efficient mobile web computing. In Proceedings of the 46th International Symposium on Computer Architecture, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 22–26 June 2019; pp. 66–78. [Google Scholar]

- Bose, P.; Das, D.; Vasan, S.; Mariani, S.; Grishchenko, I.; Continella, A.; Bianchi, A.; Kruegel, C.; Vigna, G. Columbus: Android app testing through systematic callback exploration. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/ACM 45th International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE), Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 14–20 May 2023; pp. 1381–1392. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, H.; Liu, C.; Li, Z.; Qian, F.; Li, M.; Xiong, P.; Liu, Y. Aging or glitching? What leads to poor Android responsiveness and what can we do about it? IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2023, 23, 1521–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, F.; Wang, Z.; Gerber, A.; Mao, Z.; Sen, S.; Spatscheck, O. Profiling resource usage for mobile applications: A cross-layer approach. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Mobile Systems, Applications, and Services, Washington, DC, USA, 28 July–1 June 2011; pp. 321–334. [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Martin, D.; Laso, S.; Herrera, J.L. Enhancing Smartphone Battery Life: A Deep Learning Model Based on User-Specific Application and Network Behavior. Electronics 2024, 13, 4897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suo, K.; Shi, Y.; Hung, C.C.; Bobbie, P. Quantifying context switch overhead of artificial intelligence workloads on the cloud and edges. In Proceedings of the 36th Annual ACM Symposium on Applied Computing, Gwangju, Korea, 22–26 March 2021; pp. 1182–1189. [Google Scholar]

- Fried, J.; Ruan, Z.; Ousterhout, A.; Belay, A. Caladan: Mitigating interference at microsecond timescales. In Proceedings of the 14th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI 20), Banff, AL, Canada, 4–6 November 2020; pp. 281–297. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, Z.; Shao, C.; Li, H.; Tang, Z. Review of Task-Scheduling Methods for Heterogeneous Chips. Electronics 2025, 14, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korndörfer, J.H.M.; Eleliemy, A.; Simsek, O.S.; Ilsche, T.; Schöne, R.; Ciorba, F.M. How do os and application schedulers interact? an investigation with multithreaded applications. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Parallel Processing, Madrid, Spain, 26–30 August 2023; pp. 214–228. [Google Scholar]

- Weingarten, M.E.; Grieco, M.; Edwards, S.; Khan, T.A. Icicle: Open-Source Hardware Support for Top-Down Microarchitectural Analysis on RISC-V. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Symposium on Workload Characterization (IISWC), Irvine, CA, USA, 12–14 October 2025; pp. 464–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wei, S.; Tiwari, M. Revisiting Browser Performance Benchmarking From an Architectural Perspective. IEEE Comput. Archit. Lett. 2022, 21, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.; Jo, J.E.; Lee, J.; Kim, J. Rpstacks-mt: A high-throughput design evaluation methodology for multi-core processors. In Proceedings of the 2018 51st Annual IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Microarchitecture (MICRO), Fukuoka, Japan, 20–24 October 2018; pp. 586–599. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, C.; Huang, J.; Wei, X.; Ma, Y.; Li, S.; Zheng, H.; Yu, B.; Xie, Y. ArchExplorer: Microarchitecture exploration via bottleneck analysis. In Proceedings of the 56th Annual IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Microarchitecture, Toronto, ON, Canada, 28 October–1 November 2023; pp. 268–282. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, C.; Sun, Q.; Zhai, J.; Ma, Y.; Yu, B.; Wong, M.D. BOOM-Explorer: RISC-V BOOM microarchitecture design space exploration framework. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/ACM International Conference On Computer Aided Design (ICCAD), Munich, Germany, 1–4 November 2021; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Criswell, K.; Adegbija, T. A survey of phase classification techniques for characterizing variable application behavior. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 2019, 31, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Li, Y.; Wang, C.; Jia, T.; Chow, K.; Wen, Y.; Dou, Y.; Xu, G.; Hou, C.; Yao, J.; et al. Characterizing job microarchitectural profiles at scale: Dataset and analysis. In Proceedings of the 51st International Conference on Parallel Processing, Bordeaux, France, 29 August–1 September 2022; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Schall, D.; Margaritov, A.; Ustiugov, D.; Sandberg, A.; Grot, B. Lukewarm serverless functions: Characterization and optimization. In Proceedings of the 49th Annual International Symposium on Computer Architecture, New York, NY, USA, 18–22 June 2022; pp. 757–770. [Google Scholar]

- Segu Nagesh, S.; Fernando, N.; Loke, S.W.; Neiat, A.G.; Pathirana, P.N. A Dependency-Aware Task Stealing Framework for Mobile Crowd Computing. Fut. Int. 2025, 17, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yu, F.; Zhang, S.; Yin, H.; Lin, H. Optimization of Direct Convolution Algorithms on ARM Processors for Deep Learning Inference. Mathematics 2025, 13, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrijević, N.; Lovreković, Z.; Salkić, H.; Šarčević, Đ.; Perišić, J. Benchmarking PHP–MySQL Communication: A Comparative Study of MySQLi and PDO Under Varying Query Complexity. Electronics 2025, 15, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, M.; Bernardo, M.V.; Váz, P.; Silva, J.; Martins, P. Adaptive and scalable database management with machine learning integration: A PostgreSQL case study. Information 2024, 15, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, S.; Ji, D.; Yi, W. Improving real-time performance of micro-ros with priority-driven chain-aware scheduling. Electronics 2024, 13, 1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Arora, R.; Samsi, S.; Patel, T.; Arcand, W.; Bestor, D.; Byun, C.; Roy, R.B.; Bergeron, B.; Holodnak, J.; et al. Ai-enabling workloads on large-scale gpu-accelerated system: Characterization, opportunities, and implications. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Symposium on High-Performance Computer Architecture (HPCA), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2–6 April 2022; pp. 1224–1237. [Google Scholar]

- Bucek, J.; Lange, K.D.; v. Kistowski, J. SPEC CPU2017: Next-generation compute benchmark. In Proceedings of the Companion of the 2018 ACM/SPEC International Conference on Performance Engineering, Berlin, Germany, 9–13 April 2018; pp. 41–42. [Google Scholar]

- Janapa Reddi, V.; Kanter, D.; Mattson, P.; Duke, J.; Nguyen, T.; Chukka, R.; Shiring, K.; Tan, K.S.; Charlebois, M.; Chou, W.; et al. MLPerf mobile inference benchmark: An industry-standard open-source machine learning benchmark for on-device AI. Proc. Mach. Learn. Syst. 2022, 4, 352–369. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Lee, V.; Wei, G.Y.; Brooks, D. Predicting new workload or CPU performance by analyzing public datasets. ACM Trans. Archit. Code Optim. (TACO) 2019, 15, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariofillis, V.; Jerger, N.E. Workload Characterization of Commercial Mobile Benchmark Suites. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Symposium on Performance Analysis of Systems and Software (ISPASS), Indiana, IN, USA, 5–7 May 2024; pp. 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraz, O.; Menezes, P.; Silva, V.; Falcao, G. Benchmarking vulkan vs. opengl rendering on low-power edge gpus. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Graphics and Interaction (ICGI), Porto, Portugal, 4–5 November 2021; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Bentéjac, C.; Csörgő, A.; Martínez-Muñoz, G. A comparative analysis of gradient boosting algorithms. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2021, 54, 1937–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mienye, I.D.; Sun, Y. A survey of ensemble learning: Concepts, algorithms, applications, and prospects. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 99129–99149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Singh, B. Investigating the impact of data normalization on classification performance. Appl. Soft Comput. 2020, 97, 105524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Xiong, W.; Eeckhout, L.; Bei, Z.; Mendelson, A.; Xu, C. Mia: Metric importance analysis for big data workload characterization. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 2017, 29, 1371–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Phone | Huawei Mate 30 5G | Samsung Galaxy Note10 5G |

| SoC | Kirin 990 5G | Snapdragon 855 5G |

| L1 Cache | Per Big Core: 64 KB Inst. & 64 KB Data Per Mid Core: 64 KB Inst. & 64 KB Data Per Little Core: 32 KB Inst. & 32 KB Data | Per Big Core: 64 KB Inst. & 64 KB Data Per Mid Core: 64 KB Inst. & 64 KB Data Per Little Core: 32 KB Inst. & 32 KB Data |

| L2 Cache | Per Big Core: 512 KB Per Mid Core: 512 KB Per Little Core: 128 KB | Per Big Core: 512 KB Per Mid Core: 256 KB Per Little Core: 128 KB |

| L3 Cache | 2MB | 2MB |

| Phone | Xiaomi Mi 11 Pro | OPPO OnePlus Ace |

| SoC | Snapdragon 888 5G | Dimensity 8100-MAX 5G |

| L1 Cache | Per Big Core: 64 KB Inst. & 64 KB Data Per Mid Core: 64 KB Inst. & 64 KB Data Per Little Core: 32 KB Inst. & 32 KB Data | Per Big Core: 64 KB Inst. & 64 KB Data Per Little Core: 32 KB Inst. & 32 KB Data |

| L2 Cache | Per Big Core: 1MB Per Mid Core: 512 KB Per Little Core: 128 KB | Per Big Core: 512 KB Per Little Core: 128 KB |

| L3 Cache | 4 MB | 4 MB |

| Features | Abbreviation |

|---|---|

| branch-load-misses | BRLMPKI |

| branch-store-misses | BRSMPKI |

| dTLB-load-misses | DTLMPKI |

| iTLB-load-misses | ITLMPKI |

| L1-dcache-load-misses | 1DLMPKI |

| L1-dcache-store-misses | 1DSMPKI |

| L1-icache-load-misses | 1ILMPKI |

| branch-misses | BRMSPKI |

| cache-misses | CAMIPKI |

| Subsystem Category | Micro-Architecture Feature | Abbreviation |

|---|---|---|

| Cache Hierarchy | raw-l2d-cache-wb-victim | 2DCWVPKI |

| raw-l2d-cache-refill-rd | 2DCRFPKI | |

| raw-l2d-cache-wr | 2DCWPKI | |

| raw-l2d-cache-rd | 2DCRPKI | |

| raw-l3d-cache-rd | 3DCRPKI | |

| raw-l3d-cache-refill | 3DCRFPKI | |

| raw-l1d-cache-wb-clean | 1DCWCPKI | |

| raw-l1d-cache-refill-rd | 1DCRFPKI | |

| L1-icache-load-misses | 1ILMPKI | |

| TLB (Address Translation) | raw-l1i-tlb-refill | 1ITRPKI |

| raw-itlb-walk | ITWPKI | |

| iTLB-loads | ITLPKI | |

| Branch Control | raw-br-mis-pred | BRPMPKI |

| branch-load-misses | BRLMPKI | |

| Speculative Execution | raw-ldst-spec | LSPCPKI |

| raw-strex-fail-spec | STPFPKI | |

| raw-ldrex-spec | LDREXPKI | |

| Memory and Interconnect | raw-mem-access-rd | MARPKI |

| raw-bus-access-rd | BARPKI |

| Benchmark | Cache Hierarchy | TLB Behavior | Branch Control | Speculative Execution | Memory and Interconnect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tmall | |||||

| Coolapk | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Netease | |||||

| Googledrive | |||||

| Yinxiang | |||||

| Baidu | ✓ | ||||

| Gifmaker | |||||

| PVZ | ✓ | * | ✓ | ||

| Wiz | ✓ | * | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Messenger | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | * |

| Meituan | |||||

| Ctrip | |||||

| Easymoney | ✓ | ✓ | * | ✓ | |

| Zhihu | |||||

| Health | * | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ouyang, C.; Yang, Z.; Li, G. CharSPBench: An Interaction-Aware Micro-Architecture Characterization Framework for Smartphone Benchmarks. Electronics 2026, 15, 432. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020432

Ouyang C, Yang Z, Li G. CharSPBench: An Interaction-Aware Micro-Architecture Characterization Framework for Smartphone Benchmarks. Electronics. 2026; 15(2):432. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020432

Chicago/Turabian StyleOuyang, Chenghao, Zhong Yang, and Guohui Li. 2026. "CharSPBench: An Interaction-Aware Micro-Architecture Characterization Framework for Smartphone Benchmarks" Electronics 15, no. 2: 432. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020432

APA StyleOuyang, C., Yang, Z., & Li, G. (2026). CharSPBench: An Interaction-Aware Micro-Architecture Characterization Framework for Smartphone Benchmarks. Electronics, 15(2), 432. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020432