A Distributed Electric Vehicles Charging System Powered by Photovoltaic Solar Energy with Enhanced Voltage and Frequency Control in Isolated Microgrids

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- In order to evaluate the long-term effectiveness of the commercialized PVCS, a set of evaluation indexes are introduced, including the quality of service, economic benefits, environmental benefits, and impacts on the power grid.

- (2)

- The developed project aims to create an innovative solar charging park that eliminates the need for storage batteries. By utilizing advanced solar energy conversion and distribution technology, the park ensures that all electric vehicles can be charged efficiently and sustainably. This system represents a significant advancement in electric vehicle charging infrastructure, promoting the adoption of renewable energy and contributing to the reduction of carbon emissions.

- (3)

- The power distribution algorithms of the PV panels developed in the project allow for the maximum utilization of available solar energy while ensuring customer satisfaction by considering the desired SOC. With electric vehicles parked, it is possible to establish distinct charging priorities based on the duration of the vehicles’ parking time and the users’ needs. This system offers a low cost for users while providing a higher return for energy producers.

- (4)

- The solar charging station developed in the project enhances the sustainability of buildings by eliminating the impact of electric vehicle charging on the electrical grid, as consumption from the grid is greatly reduced or even eliminated. DER production can cause frequency and voltage fluctuations in microgrids. However, in this solution, the PV system has minimal impact on the microgrid and can even correct these fluctuations, ensuring more stable and efficient operation.

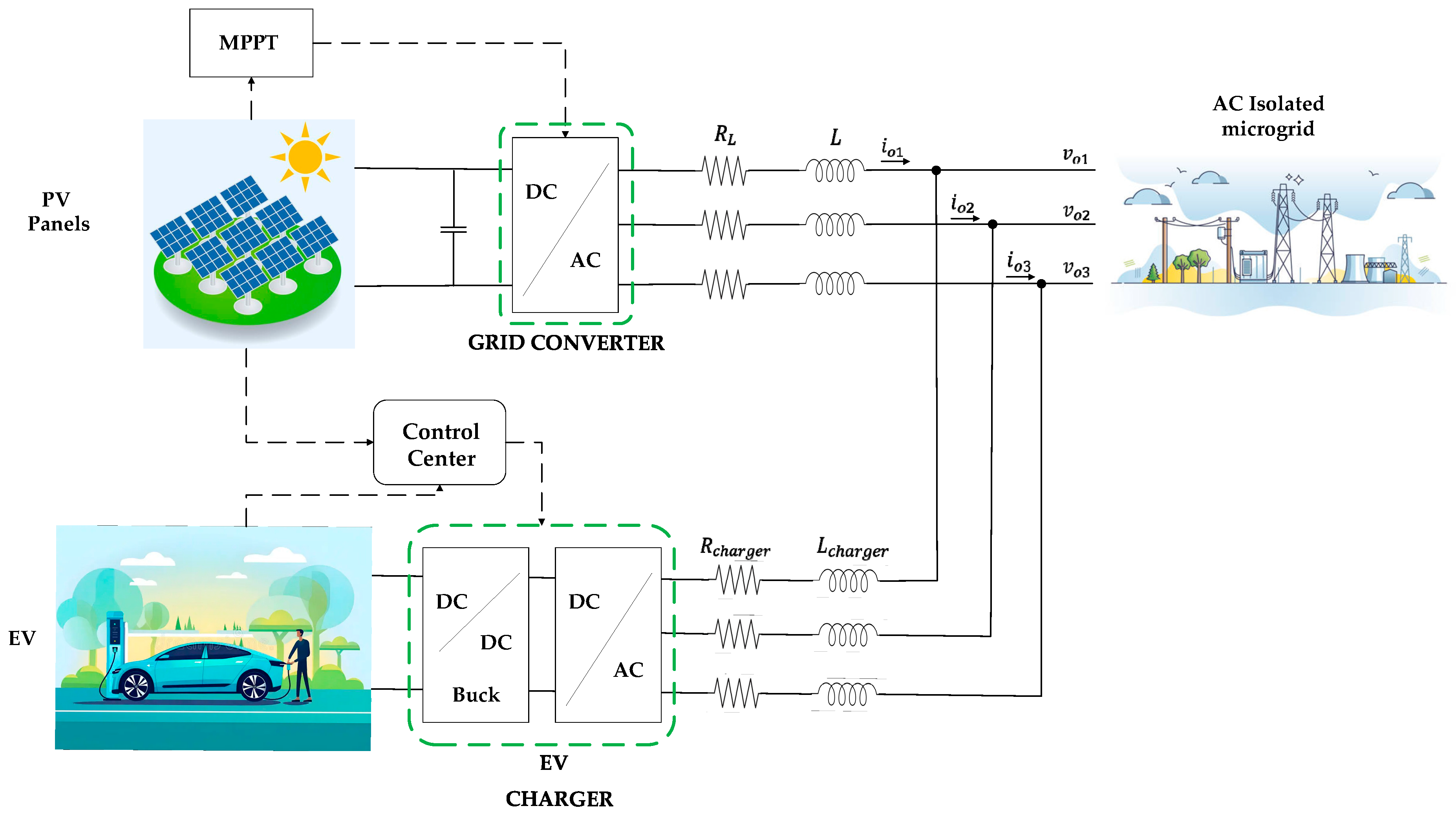

2. Proposed System

2.1. DC/AC Converter

2.1.1. Grid Current Controller

2.1.2. DC Voltage Controller

2.1.3. AC Voltage Droop Controller

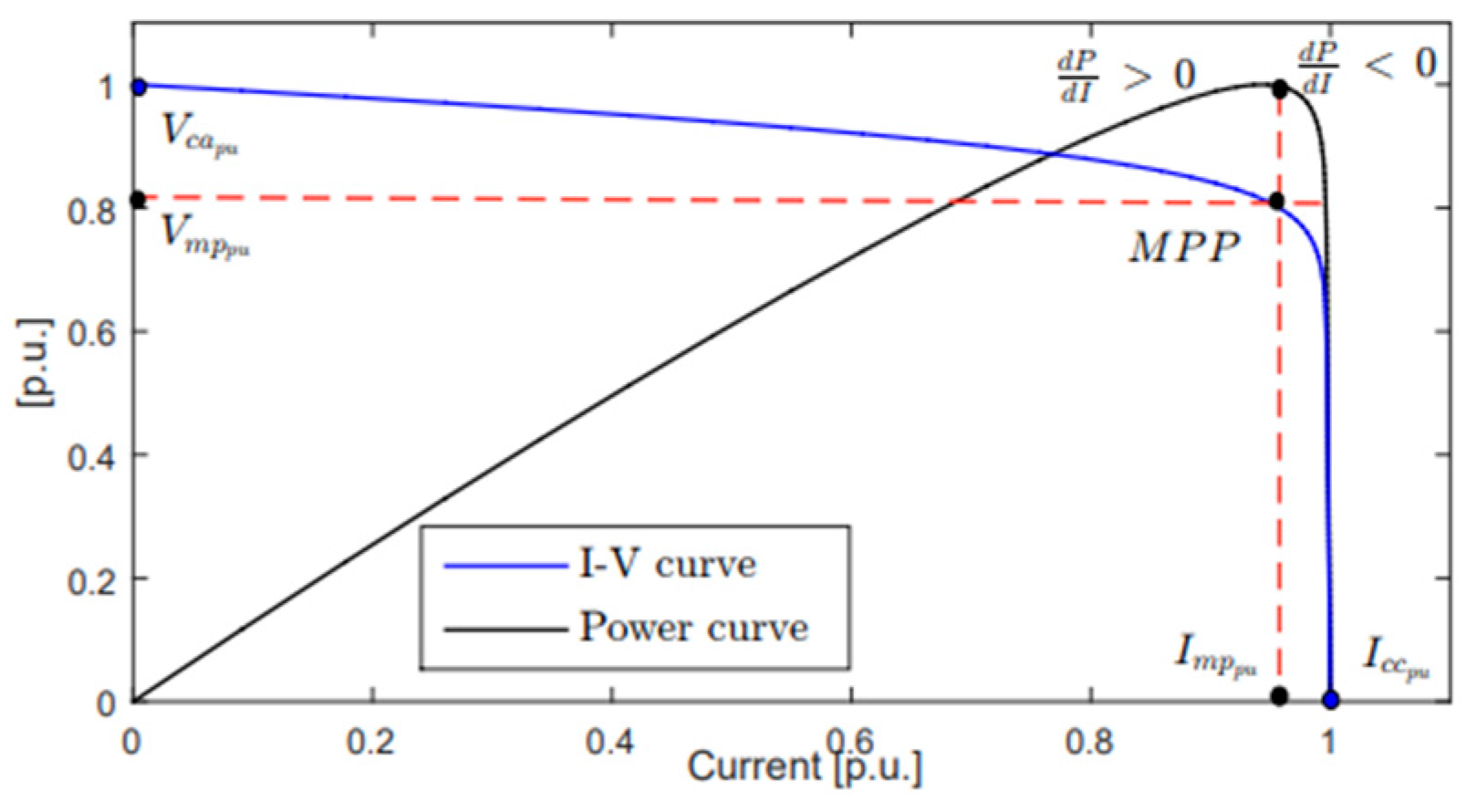

2.1.4. MPPT (Maximum Power Point Tracking)

2.2. Battery Charging System for EVs

2.2.1. Inductor Current Controller

2.2.2. Battery Voltage Controller

2.2.3. Frequency Droop Controller

3. Proposed Algorithm Frameworks

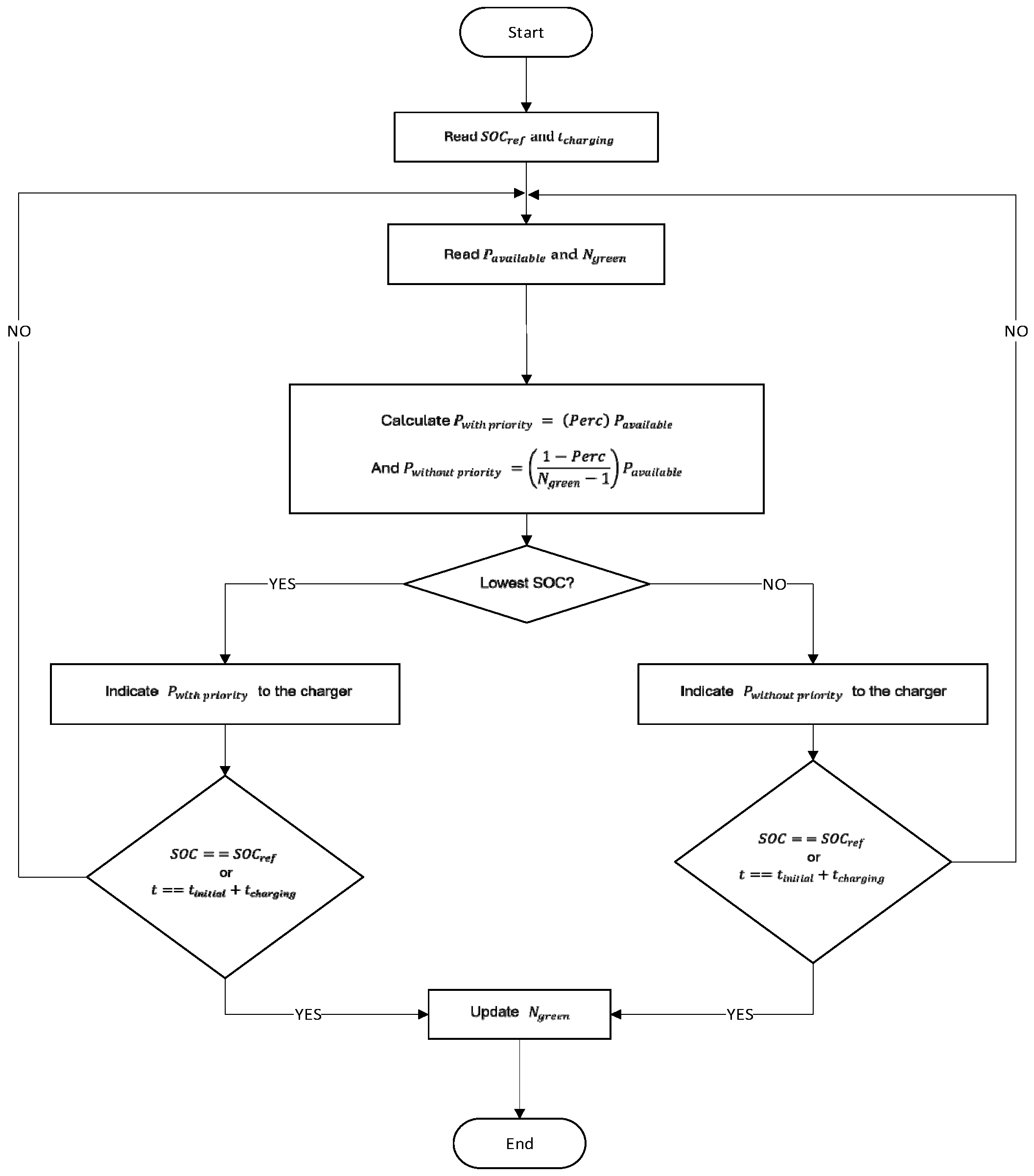

3.1. Charging Algorithms

3.1.1. Power Sharing Algorithm

3.1.2. SEWP Algorithm

3.2. Charging Modes

3.2.1. Green Mode (Solar Energy)

3.2.2. Red Mode (Microgrid Energy)

3.2.3. Yellow Mode (Mix of Solar with Microgrid Energy)

4. Simulation Results

4.1. Effectiveness

4.2. Simulation of the Distributed Electric Vehicles Charging System

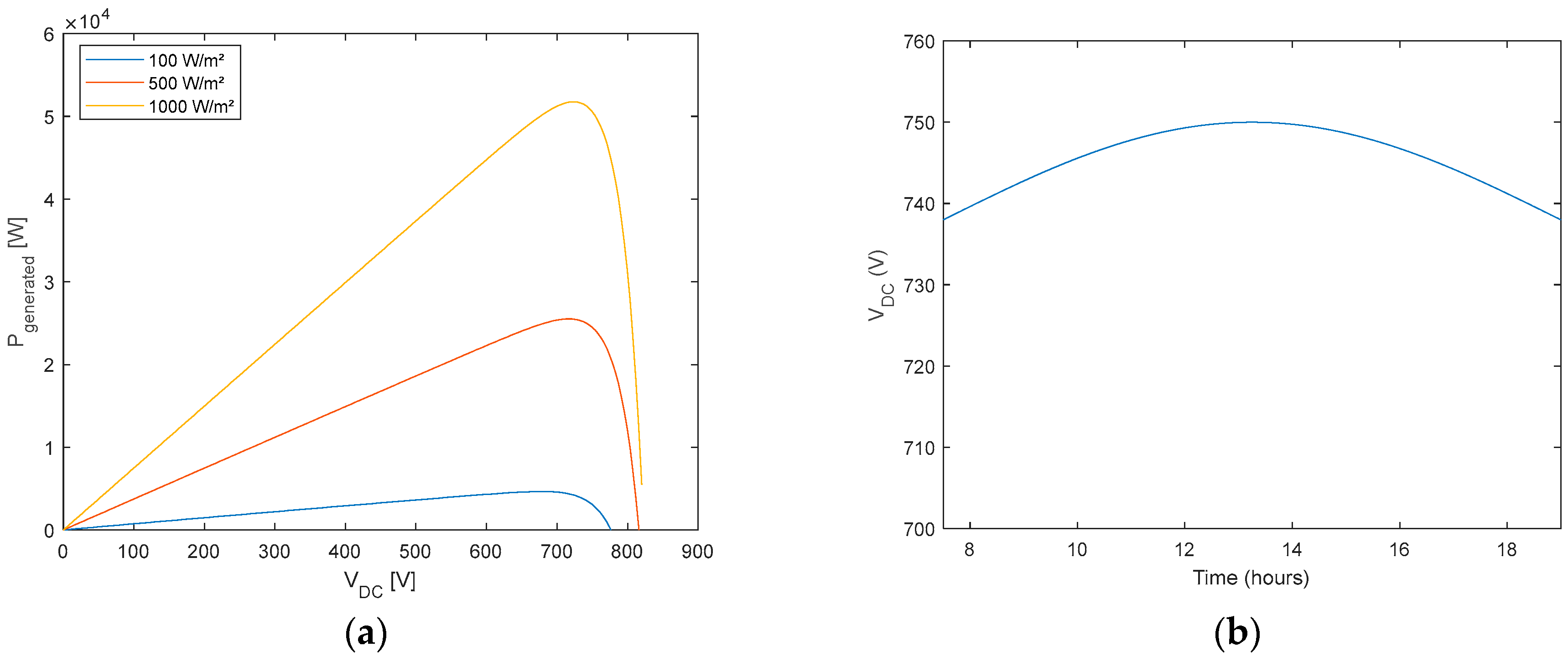

4.2.1. DC/AC Converter Simulation

4.2.2. DC/DC Converter Simulation

4.2.3. PVCS System Results

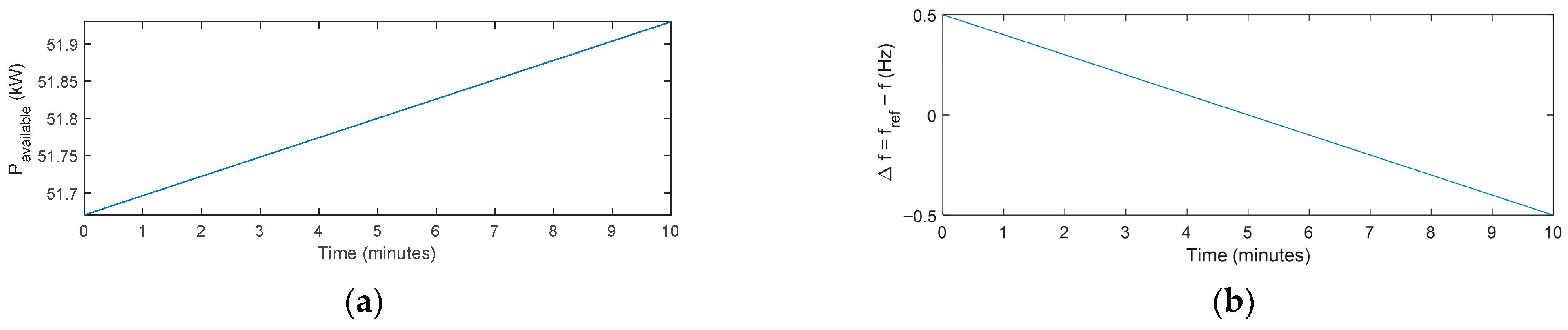

4.3. Impact of the PVCS on the Isolated Microgrid

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hasan, M.M.; Wu, C.B. Estimating energy-related CO2 emission growth in Bangladesh: The LMDI decomposition method approach. Energy Strategy Rev. 2020, 32, 100565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, Y.; Wadhwa, G.; Preethaa, K.; Paul, A. Forecasting Carbon Dioxide Emissions of Light-Duty Vehicles with Different Machine Learning Algorithms. Electronics 2023, 12, 2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.C.; Yang, Z.L.; Guo, Y.J.; Zhang, J.K.; Yang, H.K. Short-term load forecasting for electric vehicle charging stations based on deep learning approaches. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooftman, N.; Oliveira, L.; Messagi, M.; Coosemans, T.; Mierlo, J.V. Environmental Analysis of Petrol, Diesel and Electric Passenger Cars in a Belgian Urban Setting. Energies 2016, 9, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denholm, P.; Margolis, R. Evaluating the limits of solar photovoltaics (PV) in traditional electric power systems. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 2852–2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Ionel, D.M. Improving the Power Outage Resilience of Buildings with Solar PV through the Use of Battery Systems and EV Energy Storage. Energies 2021, 14, 5749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denholm, P.; Kuss, M.; Margolis, R. Co-benefits of large scale plug-in hybrid electric vehicle and solar PV deployment. J. Power Sources 2012, 236, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poullikkas, A. Sustainable options for electric vehicle techonologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 41, 1277–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, J.; Li, A.; Huang, F. Power Feasible Region Modeling and Voltage Support Control for V2G Charging Station Under Grid Fault Conditions. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twaisan, K.; Barisci, N. Integrated Distributed Energy Resources (DER) and Microgrids: Modeling and Optimization of DERs. Electronics 2022, 11, 2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Kim, H.-M. A Rule-Based Modular Energy Management System for AC/DC Hybrid Microgrids. Sustainability 2025, 17, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwasilu, F.; Justo, J.J.; Kim, E.-K.; Do, T.D.; Jung, J.-W. Electric vehicles and smart grid interaction: A review on vehicle to grid and renewable energy sources integration. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 34, 501–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouveia, C.; Rua, D.; Soares, F.J.; Moreira, C.; Matos, P.G.; Lopes, J.P. Development and implementation of Portuguese smart distribution system. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2015, 120, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazelpour, F.; Vafaeipour, M.; Rahbari, O.; Rosen, M.A. Intelligent optimization to integrate a plug-in hybrid electric vehicle smart parking lot with renewable energy resources and enhance grid characteristics. Energy Convers. Manag. 2014, 77, 250–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, D.; Anadon, L. Power price stability and the insurance value of renewable technologies. Nat. Energy 2024, 10, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Li, Y. Effects of diversified subsidies on the decisions of infrastructure operators considering charging infrastructure construction level and price sensitivity. Enviromental Dev. Sustain. 2023, 26, 11343–11377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoade, I.; Longe, O. A Comprehensive Review on Smart Electromobility Charging Infrastructure. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zentani, A.; Almaktoof, A.; Kahn, M. A Comprehensive Review of Developments in Electric Vehicles Fast Charging Technology. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kchaou-Boujelben, M. Charging station location problem: A comprehensive review on models and solution approaches. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2021, 132, 103376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, P.; Farias, T.; Brito, M.C. Day charging electric vehicles with excess solar eletricity for a sustainable energy system. Energy 2015, 80, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, H.-Y.; Rong, Y.; Shen, Z.-J. Infrastructure Planning for Electric Vehicles with Battery Swapping. Manag. Sci. 2013, 59, 1479–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulpule, P.; Yurkovich, S.; Rizzoni, G. Economic and environmental impacts of a PV powered workplace parking garage charging station. Appl. Sci. 2013, 108, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, J.V.; Leemput, N.; Geth, F.; Buscher, J.; Salenbien, R.; Driesen, J. Apartment Building Electricity System Impact of Operational Electric Vehicle Charging Strategies. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2014, 5, 264–272. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, J.V.; Leemput, N.; Geth, F.; Buscher, J.; Salenbien, R.; Driesen, J. Electric Vehicle Charging in an Office Building Microgrid With Distributed Energy Resources. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2014, 5, 1389–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guven, A. Integrating electric vehicles into hybrid microgrids: A stochastic approach to future-ready renewable energy solutions and management. Energy 2024, 303, 131968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Sood, Y.; Jaiswal, S. Modeling and Simulation of Green Electric Vehicle Charging Station using MATLAB. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Students’ Conference on Electrical, Electronics and Computer Science (SCEECS), Bhopal, India, 24–25 February 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mauler, L.; Duffner, F.; Zeier, W.G.; Leker, J. Battery cost forecasting: A review of methods and results with an outlook to 2050. Energy Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 4712–4739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassoune, A.; Khafallah, M.; Mesbahi, A.; Breuil, D. Electrical design of a photovoltaic-grid system for electric vehicles charging station. In Proceedings of the 2017 14th International Multi-Conference on Systems, Signals & Devices (SSD), Marrakech, Morocco, 28–31 March 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, Z.H.; Raisz, D. Power Flow and Voltage Control Strategies in Hybrid AC/DC Microgrids for EV Charging and Renewable Integration. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, V.; Seema, B. A Grid Connected PV Array and Battery Energy Storage Interfaced EV Charging Station. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2023, 9, 3723–3730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Lu, C.; Liu, H.; Wang, N.; Chen, L.; Wang, C.; Jiang, X.; Ye, C. Optimal Design and Energy Management of Residential Prosumer Community with Photovoltaic Power Generation and Storage for Electric Vehicles. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 33, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, A.S.; de Santana, T.; MacGill, I.; Ekins-Daukes, N.; Reinders, A. A Feasibility Study of Solar PV-Powered Electric Cars Using an Interdisciplinary Modeling Approach for the Electricity Balance, CO2 Emissions, and Economic Aspects: The Cases of The Netherlands, Norway, Brazil, and Australia. Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 2020, 28, 517–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheikh-Mohamad, S.; Celik, B.; Sechilariu, M.; Locment, F. PV-Powered Charging Station with Energy Cost Optimization via V2G Services. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.; Salehi, V.; Ma, T.; Mohammed, O. Real-Time Energy Management Algorithm for Plug-In Hybrid Electric Vehicle Charging Parks Involving Sustainable Energy. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2014, 5, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, J.; Morais, H.; Sousa, T.; Vale, Z.; Faria, P. Day-ahead resource scheduling including demand response for electric vehicles. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2013, 4, 596–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Li, V.; Lam, A. Optimal V2G scheduling of electric vehicles and unit commitment using chemical reaction optimization. In Proceedings of the IEEE Congress Evolutionary Computation (CEC), Cancun, Mexico, 20–23 June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Q.; Wang, J.; Zhou, M.; Ammari, A. Centralized charging strategy and scheduling algorithm for electric vehicles under a battery swapping scenario. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2016, 17, 659–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, T.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, B. Intelligent Energy Management Algorithms for EV-charging Scheduling with Consideration of Multiple EV Charging Modes. Energies 2019, 12, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razi, R.; Hajar, K.; Hably, A.; Bacha, S. A User-Friendly Smart Charging Algorithm Based on Energy-Awareness for Different PEV Parking Scenarios. In Proceedings of the 2021 29th Mediterranean Conference on Control and Automation (MED), Puglia, Itaty, 15 January 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Derbeli, M.; Napole, C.; Barambones, O.; Sanchez, J.; Calvo, I.; Fernández-Bustamante, P. Maximum Power Point Tracking Techniques for Photovoltaic Panel: A Review and Experimental Applications. Energies 2021, 14, 7806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, B.; Xu, X.; Gu, Y.; Deng, K.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Gao, X.; Wang, K.; Wei, Q. Improved Droop Control Strategy for Islanded Microgrids Based on the Adaptive Weight Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm. Electronics 2025, 14, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndeke, C.B.; Adonis, M.; Almaktoof, A. Basic Circuit Model of Voltage Source Converters: Methodology and Modeling. Applied Math. 2024, 4, 889–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özer, Ş.C.; Dağ, B.; Demirel, S.; Özdemir, M.A. Design and Implementation of Peak Current Modern with PI Controller for Coupled Inductor-Based High-Gain Z-Source Converter. Electronics 2024, 13, 2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merai, M.; Naouar, M.W.; Slama-Belkhodja, I.; Monmasson, E. An Adaptive PI Controller Design for DC-Link Voltage Control of Single-Phase Grid-Connected Converters. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2019, 14, 6241–6249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zayed, M.S.A.; Attia, H.E.M.; Emara, M.M.; Mansour, D.-E.A.; Abdelfattah, H. Development of a New Solid State Fault Current Limiter for Effective Fault Current Limitations in Wind-Integrated Grids. Electronics 2025, 45 14, 4054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Y.; Zhang, H.; Cao, X.; Zhang, R.; Ji, L.; Wei, X.; Liu, Y. Research on Grid-Connected Off-Grid Control Strategy for Bidirectional Energy Storage Inverter. Electronics 2024, 13, 4911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.R.; Bharatiraja, C.; Udhayakumar, K.; Devakirubakaran, S.; Sekar, K.S.; Mihet-Popa, L. Advances in Batteries, Battery Modeling, Battery Management System, Battery Thermal Management, SOC, SOH, and Charge/Discharge Characteristics in EV Applications. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 105761–105809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, O.; Dessaint, L.A. Experimental Validation of a Battery Dynamic Model for EV Applications. World Electr. Veh. J. 2009, 3, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Yan, S. Distributed energy sharing algorithm for Micro Grid energy system based on cloud computing. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2018, 46, 1689–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, M.; Rossi, C. A Review of EV Adoption, Charging Infrastructure Growth in Europe and Italy. Batteries 2025, 11, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madani, S.S.; Shabeer, Y.; Wang, Z.; Panchal, S.; Allard, F.; Chaoui, H.; Fowler, M.; Mekhilef, S.; Ziebert, C.; Dou, S.X.; et al. A Comprehensive Review on Lithium-Ion Battery Lifetime Prediction and Aging Mechanism Analysis. Batteries 2025, 11, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, P.; Singh, A.K.; Kumar, N. Electric vehicle battery state-of-charge estimation based on optimized deep learning strategy with varying temperature at different C Rate. J. Eng. Res. 2023, 11, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| EV nominal voltage | 400 V |

| EV rated capacity | 80 Ah |

| EV internal resistance | 0.05 Ω |

| Minimum SOC | 20% |

| PV voltage at maximum power point, Vmp | 37.8 V |

| PV current at maximum power point, Imp | 9.39 A |

| ) | 1 mH |

| ) | 10 mF |

| ) | 3.57 mH |

| ) | 3.73 mH |

| ) | 10 mF |

| ) | F |

| ) | 10 kHz |

| 0.00889 | |

| 1.97 | |

| −0.0885 | |

| −0.393 | |

| 174.53 | |

| 0.0222 | |

| 49.0351 | |

| −0.0011 | |

| −0.0493 | |

| −0.005 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Baltazar, P.; Barros, J.D.; Gomes, L. A Distributed Electric Vehicles Charging System Powered by Photovoltaic Solar Energy with Enhanced Voltage and Frequency Control in Isolated Microgrids. Electronics 2026, 15, 418. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020418

Baltazar P, Barros JD, Gomes L. A Distributed Electric Vehicles Charging System Powered by Photovoltaic Solar Energy with Enhanced Voltage and Frequency Control in Isolated Microgrids. Electronics. 2026; 15(2):418. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020418

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaltazar, Pedro, João Dionísio Barros, and Luís Gomes. 2026. "A Distributed Electric Vehicles Charging System Powered by Photovoltaic Solar Energy with Enhanced Voltage and Frequency Control in Isolated Microgrids" Electronics 15, no. 2: 418. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020418

APA StyleBaltazar, P., Barros, J. D., & Gomes, L. (2026). A Distributed Electric Vehicles Charging System Powered by Photovoltaic Solar Energy with Enhanced Voltage and Frequency Control in Isolated Microgrids. Electronics, 15(2), 418. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020418