A Reinforcement Learning-Based Link State Optimization for Handover and Link Duration Performance Enhancement in Low Earth Orbit Satellite Networks

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Traditional Handover Techniques in LEO Satellite Networks

2.2. AI-Based and Learning-Based Handover Strategies

2.3. Positioning of This Work

3. Proposed Method

3.1. Proposed Structure

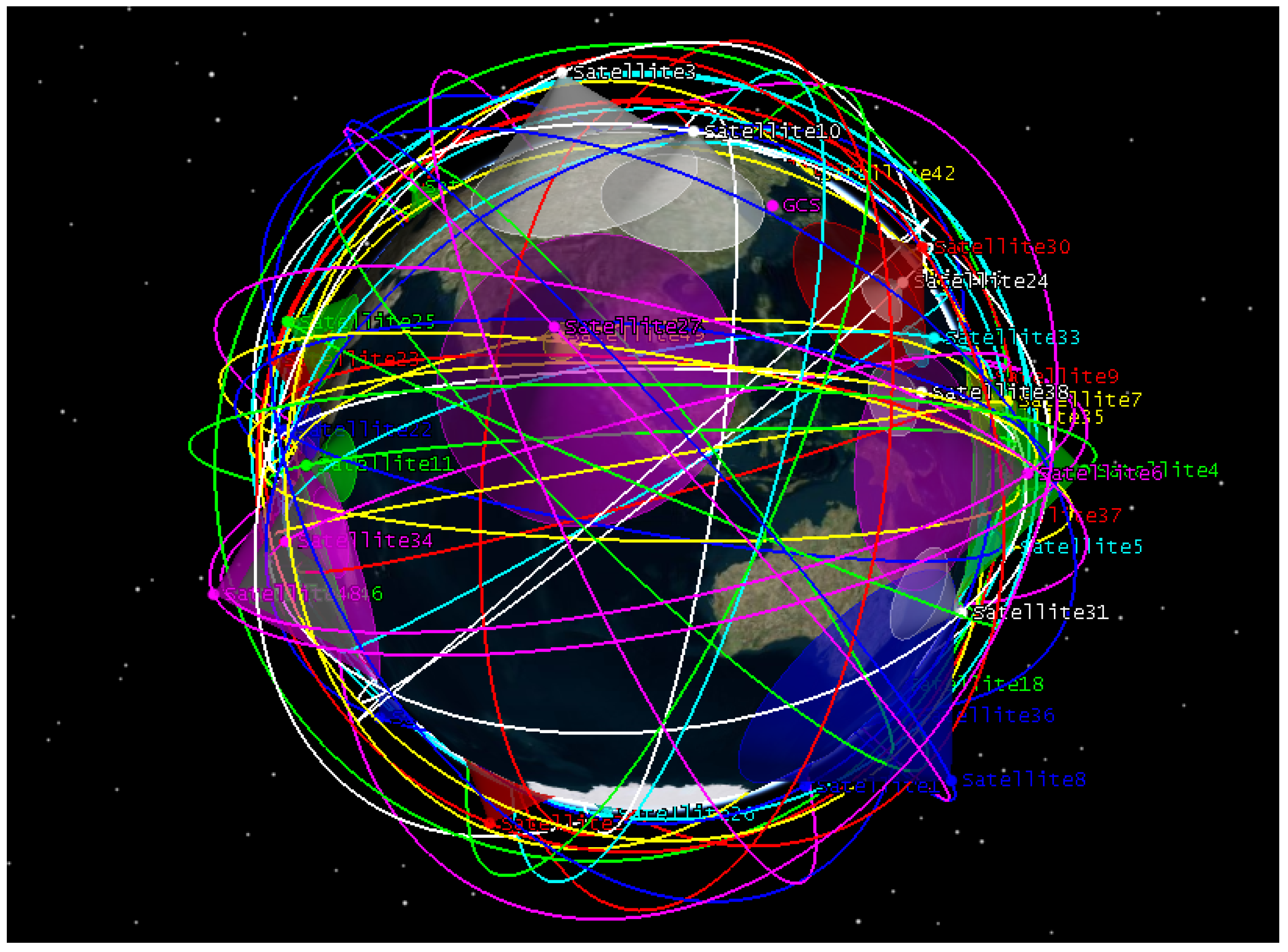

3.1.1. Existing Network Structure

3.1.2. Low Orbit Satellites

3.1.3. Reinforcement Learning-Based Approach

- SARSA follows an on-policy approach, effectively balancing exploration and exploitation.

- Q-Learning adopts an off-policy mechanism to independently learn optimal actions with faster convergence.

- DQN, integrating neural networks with Q-Learning, ensures stable learning in complex state spaces using experience replay and target networks.

3.2. Design

3.2.1. Raw Data Construction

3.2.2. Dataset Generation

3.2.3. Reward Function Design

| Algorithm 1: Reward Computation Based on Selected Features |

| Input: Selected feature vector: Output: Reward value r Extract features: Convert features to scores: // Higher if distance is short Compute weighted sum: Apply penalty: if then return r |

3.3. Implementation

3.3.1. Reinforcement Learning Models

3.3.2. DQN Algorithm Configuration

4. Performance Evaluation

4.1. Experimental Setup

- OS: Windows 11

- CPU: Intel Core i7-14700K (20 cores, 28 threads)

- GPU: NVIDIA RTX 4090

- RAM: 32 GB

- Environment: Python 3.12 (Anaconda)

- Framework: OpenAI Gym (Custom Environment: ‘AERActionBasedEnv’)

4.2. Dataset and Preprocessing

4.2.1. Data Sampling

4.2.2. Feature Engineering and Normalization

4.3. RL Environment and Hyperparameters

4.3.1. State, Action, and Episode Configuration

4.3.2. Reward Function

- A penalty was applied if the elevation angle was below 30° (0.333 on a normalized scale).

- An additional penalty of −0.07 was imposed if the total reward was less than 0.2.

4.3.3. DQN Hyperparameters and Common Policies

- Network Architecture: Two hidden layers with 128 units each, using the ReLU activation function.

- Experience Replay Buffer Size: 10,000

- Batch Size: 32

- Loss Function: Mean Squared Error (MSE)

- Target Network Update Frequency: Every 10 episodes

4.4. Performance Evaluation Metrics

- Handover Frequency: The number of times the serving satellite ID changed per episode.

- Link Duration: The average ratio of steps during which a connection with the same satellite was maintained.

4.5. Experimental Results

4.6. Ablation Analysis of State Components

5. Conclusions

5.1. Summary of the Study

5.2. Contributions and Implications

6. Limitations and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kodheli, O.; Lagunas, E.; Maturo, N.; Sharma, S.K.; Shankar, B.; Montoya, J.F.M.; Duncan, J.C.M.; Spano, D.; Chatzinotas, S.; Kisseleff, S.; et al. Satellite communications in the new space era: A survey and future challenges. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2020, 23, 70–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzunalioglu, H.; Akyildiz, I.; Yesha, Y.; Yen, W. Footprint handover rerouting protocol for low Earth orbit satellite networks. Wirel. Netw. 1999, 5, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yang, Z.; Pan, G.; Zhang, H.; Luo, G.; Yang, H. Handover Technique in LEO Satellite Networks: A Review. In Proceedings of the 2024 13th International Conference on Communications, Circuits and Systems (ICCCAS), Chengdu, China, 10–12 May 2024; pp. 364–369. [Google Scholar]

- Handley, M. Delay is Not an Option: Low Latency Routing in Space. In Proceedings of the 17th ACM Workshop on Hot Topics in Networks (HotNets), Redmond, WA, USA, 15–16 November 2018; pp. 85–91. [Google Scholar]

- Barros, G.; Vieira, J.; Ganhao, F.; Bernardo, L.; Dinis, R.; Carvalho, P.; Oliveira, R.; Pinto, P. A Soft-Handover Scheme for LEO Satellite Networks. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE 78th Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC Fall), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2–5 September 2013; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, P.; Atiquzzaman, M.; Ivancic, W. Handover schemes in satellite networks: State-of-the-art and future research directions. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2006, 8, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Zhou, G.; Tsai, H. Load Balanced Handover Planning for LEO Satellite Communication Networks. In Proceedings of the 2024 Intermountain Engineering Technology and Computing (IETC), Orem, UT, USA, 28 June 2024; pp. 302–307. [Google Scholar]

- Kaelbling, L.; Littman, M.; Moore, A. Reinforcement Learning: A Survey. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 1996, 4, 237–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Deep Reinforcement Learning: An Overview. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1701.07274. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yarats, D.; Kostrikov, I.; Fergus, R. Image Augmentation Is All You Need: Regularizing Deep Reinforcement Learning from Pixels. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Virtual Event, 3–7 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Buhl, V.; Barber, D.; Kennedy, S.; Rogers, D. A Comparative Analysis on Using Low Earth Orbit and Geosynchronous Orbit Satellite Communication Systems to Support Telemedical Networks in Austere Environments. In Proceedings of the 58th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Honolulu, HI, USA, 7–10 January 2025; pp. 3397–3410. [Google Scholar]

- Juan, E.; Lauridsen, M.; Wigard, J.; Mogensen, P. Handover solutions for 5G low-earth orbit satellite networks. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 93309–93325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Bang, I.; Kim, T.; Lee, H.; Jung, B.C.; Chae, S.H. Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning Based Handover Strategy for LEO Satellite Networks. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2025, 29, 1117–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahouda, M.K.; Jin, S.; Joe, I. Machine learning-based solutions for handover decisions in non-terrestrial networks. Electronics 2023, 12, 1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, F.; Maattanen, H.L.; Torsner, J.; Pizzi, S.; Andreev, S.; Iera, A.; Koucheryavy, Y.; Araniti, G. Non-terrestrial networks in 5G & beyond: A survey. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 165178–165200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvan, K.; Siemuri, A.; Prol, F.; Välisuo, P.; Bhuiyan, M.; Kuusniemi, H. Precise orbit determination of LEO satellites: A Systematic review. GPS Solut. 2023, 27, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method Category | Learning Paradigm | State Information | Agent Type | Inference Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MARL-based Handover [13,14] | MARL | Local UE info | Multi-agent | High |

| Prediction-based Handover [12] | Rule/Optimization | Trajectory, Dwell-time | Non-learning | Low |

| Learning-assisted Mobility [15] | RL/ML | High-dimensional | Single/Multi | Medium–High |

| Proposed Method | Single-agent RL | GNSS-only (AER + Dir.) | Single-agent | Low |

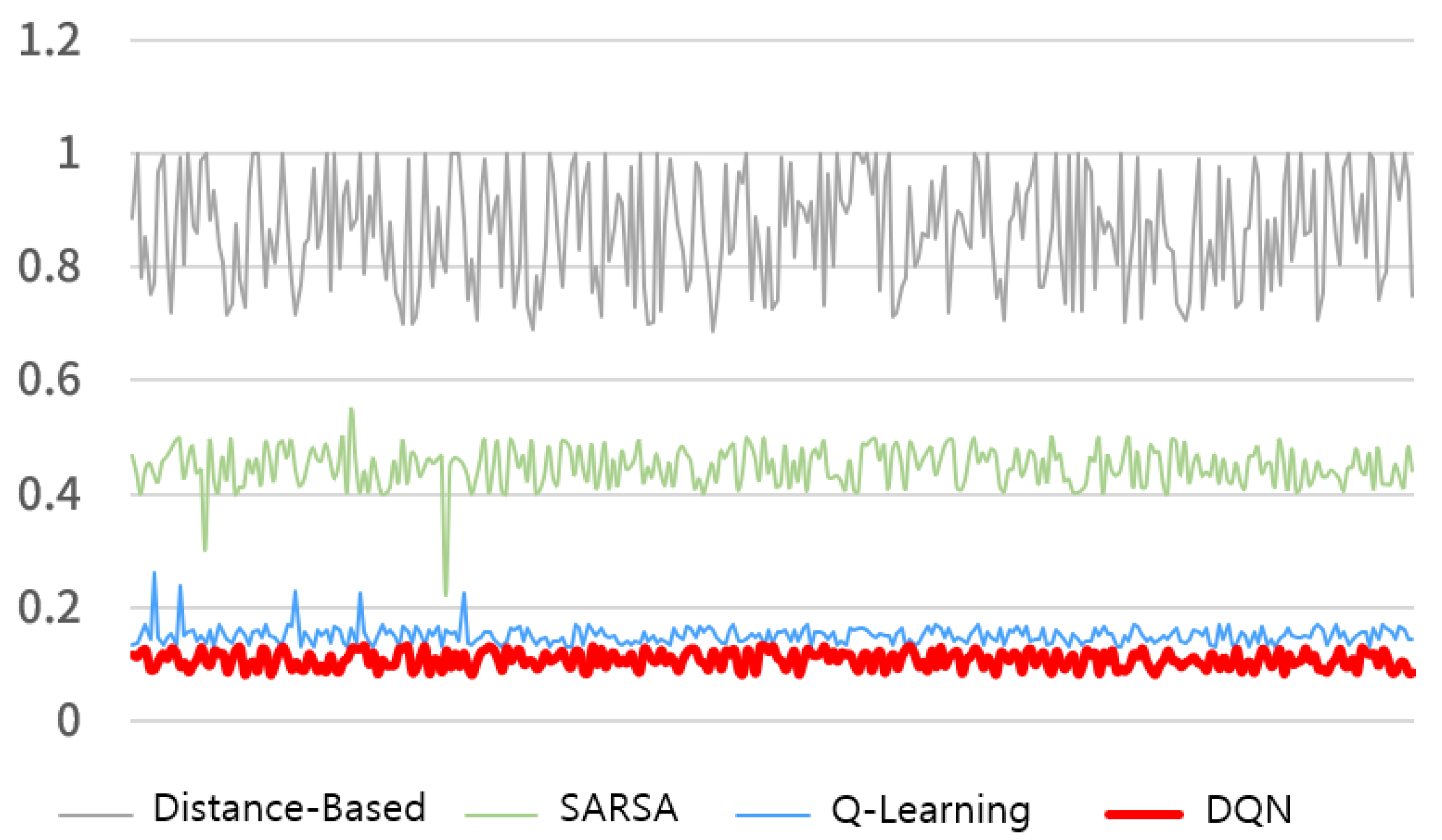

| Model | Avg. Handover Freq. | Avg. Link Duration |

|---|---|---|

| Distance-based | 0.8702 (±0.100) | 0.1719 (±0.050) |

| SARSA | 0.4411 (±0.080) | 0.2247 (±0.040) |

| Q-Learning | 0.1839 (±0.050) | 0.2810 (±0.020) |

| DQN | 0.1020 (±0.030) | 0.3001 (±0.020) |

| State Configuration | Avg.Handover Count | Avg.Link Duration Ratio |

|---|---|---|

| Full State | 0.104 | 0.301 |

| Direction Difference | 0.176 | 0.224 |

| Elevation | 0.162 | 0.241 |

| Range | 0.118 | 0.283 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jin, S.; Park, D.; Kim, S.; Lee, J.; Joe, I. A Reinforcement Learning-Based Link State Optimization for Handover and Link Duration Performance Enhancement in Low Earth Orbit Satellite Networks. Electronics 2026, 15, 398. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020398

Jin S, Park D, Kim S, Lee J, Joe I. A Reinforcement Learning-Based Link State Optimization for Handover and Link Duration Performance Enhancement in Low Earth Orbit Satellite Networks. Electronics. 2026; 15(2):398. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020398

Chicago/Turabian StyleJin, Sihwa, Doyeon Park, Sieun Kim, Jinho Lee, and Inwhee Joe. 2026. "A Reinforcement Learning-Based Link State Optimization for Handover and Link Duration Performance Enhancement in Low Earth Orbit Satellite Networks" Electronics 15, no. 2: 398. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020398

APA StyleJin, S., Park, D., Kim, S., Lee, J., & Joe, I. (2026). A Reinforcement Learning-Based Link State Optimization for Handover and Link Duration Performance Enhancement in Low Earth Orbit Satellite Networks. Electronics, 15(2), 398. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020398