1. Introduction

Modern wireless, radar, and satellite communication systems increasingly require compact antenna structures capable of supporting multiple frequency bands. In particular, dual-band antennas operating in the X-band (8–12 GHz) and Ku-band (12–18 GHz) are essential for applications such as high-resolution radar imaging, satellite telemetry, CubeSat payloads, and high-capacity backhaul links. Recent 5G and emerging 6G studies further emphasize flexible spectrum usage and multi-band operation, reinforcing the need for integrating multiple frequency bands within a single antenna platform [

1,

2]. Such integration improves multifunctionality while reducing payload mass, volume, and system complexity. Representative examples include the CubeSat antenna in [

3] and the shared-aperture array in [

4], both demonstrating efficient dual-band operation within compact structures.

Despite these advantages, achieving reliable dual-band performance remains challenging due to the distinct electromagnetic characteristics of the X- and Ku-bands [

5]. Dual-band operation often requires additional parasitic elements, multilayer configurations, or frequency-selective substructures, which increase fabrication complexity and sensitivity to manufacturing tolerances. Reflectarray-based solutions and multilayer microstrip designs further increase mechanical thickness and alignment requirements [

6]. Single-layer approaches, while more compact, may suffer from inter-band coupling, degraded impedance matching, or distorted radiation characteristics. Moreover, maintaining stable gain, beamwidth, and polarization behavior across both bands remains a nontrivial task, particularly when band-isolating techniques such as frequency-selective surfaces are employed [

7,

8,

9].

To address these challenges, multi-objective optimization (MOO) has become an effective design strategy for dual-band antennas. MOO frameworks enable the simultaneous optimization of gain, impedance matching, and physical size by capturing trade-offs among competing objectives. Evolutionary and swarm-based algorithms, including NSGA-II and related methods, have been successfully applied to dual-band and broadband antenna designs [

10,

11,

12,

13]. Meta-heuristic techniques such as Genetic Algorithm (GA) [

14], Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [

15], Ant Colony Optimization (ACO) [

16], and Differential Evolution (DE) [

17] are particularly well suited for nonlinear electromagnetic optimization problems, with PSO and evolutionary approaches showing strong performance in multi-band configurations [

18,

19]. Hybrid strategies further enhance convergence behavior [

20], while bee-inspired algorithms such as Artificial Bee Colony (ABC) [

21] and Honey Bee Mating Optimization (HBMO) [

22] offer strong global search capability and robustness.

2. Theory and Design

The proposed antenna structure can be modeled as a vertically oriented monopole radiator loaded with concentric cylindrical dielectric layers. In classical antenna theory, the resonant length of a monopole is approximately one-quarter of the wavelength in the surrounding medium and can be expressed as:

where

c is the speed of light,

f is the operating frequency, and

is the effective dielectric constant of the surrounding medium. By introducing multiple concentric cylindrical layers with different radii (

R1,

R2,

R3) and dielectric constants (

) the effective permittivity becomes a function of the volumetric contributions of each layer:

In Equation (2), denotes the volume of the i-th dielectric layer.

This approach enables fine-tuning of both the resonant frequency and impedance characteristics. The choice of three dielectric layers represents a balance between design flexibility and optimization complexity. A two-layer structure limits the available degrees of freedom for achieving dual-band operation, whereas four or more layers increase the number of parameters, prolonging the convergence process of the optimization algorithm. Thus, the three-layer configuration provides sufficient freedom to simultaneously cover both X- and Ku-bands, while maintaining manageable complexity for both computation and fabrication.

The heights of the cylindrical layers were chosen to be equal to H1, in order to reduce the number of design variables and simplify the optimization process. From a fabrication perspective, equal heights minimize discontinuities between layers, ensuring mechanical robustness and stable electromagnetic performance. While spherical structures may theoretically provide isotropic characteristics, in practice they introduce significant manufacturing tolerances and complicate integration with monopole feeding. In contrast, cylindrical geometry naturally aligns with the monopole’s axis, facilitates seamless feeding integration, and allows precise control during additive manufacturing. Furthermore, cylindrical geometry provides a continuous radial dielectric profile, allowing more accurate adjustment of , while avoiding field concentration effects typically observed in prismatic or polygonal shapes. This ensures stable gain and bandwidth performance.

The novelty of the proposed design lies in the implementation of three concentric dielectric layers with distinct permittivity values, fabricated using 3D printing technology. The permittivity of each layer is tuned through the infill ratio, introducing a material-based optimization dimension in addition to conventional geometric control. This feature distinguishes the proposed antenna from traditional dual-band designs in the literature, offering a compact, easily realizable, and optimization-friendly structure that contributes both methodologically and technologically to antenna design.

The input impedance of a monopole antenna over a ground plane is classically defined as:

In the proposed concentric cylindrical configuration, however, the input impedance is redefined as a function of the effective dielectric constant:

The far-field component of a classical monopole antenna is expressed as:

where

k = (2

π/

λ). In the proposed model, the propagation constant is modified according to the effective permittivity:

Thus, the far-field expression becomes:

This modification directly links the effective electrical length (

) to the radiation properties, thereby influencing both the half-power beamwidth (HPBW) and directivity. In conclusion, the proposed three-layer concentric cylindrical monopole antenna distinguishes itself from conventional designs through its compactness, ease of fabrication, and optimization suitability. When combined with the HBMO algorithm, it achieves stable performance in both X- and Ku-bands, offering a novel and effective solution for high-frequency dual-band applications. The schematic and 3D view of the proposed dielectric-loaded monopole antenna are illustrated in

Figure 1. The structure consists of three cylindrical dielectric sections with different radii (

R1,

R2,

R3) and relative permittivities (

,

,

), along with a central feeding cavity. By adjusting the infill rate in the 3D printing process, each dielectric layer can be assigned a distinct permittivity value, providing additional degrees of freedom for optimization. To limit the number of variables, all dielectric layers share the same height (

H1) which is one of the optimization variables of the study antenna while the metallic ground plane thickness (

H2) is fixed at 0.1 mm. The design variables and their respective search ranges are summarized in

Table 2.

The cost function given in Equations (8)–(12) is designed to evaluate the performance of each candidate solution generated by the optimization algorithm. This function includes return loss (S

11) and maximum gain at the desired operating frequency bands, with particular emphasis on achieving antenna designs that provide high gain and dual-band performance in the X and Ku bands. In order to achieve optimum antenna performance, a multi-objective cost function was formulated, incorporating impedance matching and gain at both X- and Ku-band frequencies:

with the objective terms defined as:

Here,

x is the vector of optimization parameters given in

Table 2. [

fc1,

fc2] and [

fc3,

fc4] represent the boundary values of the targeted operating bands. [

w1,

w2] are weighting coefficients used to adjust the importance of the cost terms

Ci = 1, 2, 3, 4.

These two performance metrics (Gain, S11) are deliberately selected as optimization objectives since they are among the most widely adopted figures of merit in meta-heuristic antenna optimization studies, particularly for antenna configurations, and they directly represent the antenna’s electromagnetic efficiency and radiation effectiveness. For antennas operating in the X and Ku bands, impedance matching governs efficient power transfer and usable bandwidth, while gain characterizes the overall radiation performance; other figures of merit are either strongly correlated with gain or become secondary for compact omnidirectional monopole structures.

In this study, the weighting coefficients are chosen as w1 = 0.3 and w2 = 0.7 to balance the significant difference in magnitude between the two objectives. Specifically, the reflection coefficient S11 can reach values as low as −30 dB, whereas the gain of the proposed antenna is approximately 8 dBi. Without appropriate weighting, the numerical scale of the S11 term would dominate the cost function and suppress the influence of the gain term. The selected weighting strategy ensures that both objectives contribute effectively to the optimization process, while also maintaining a computationally efficient and experimentally robust framework, since impedance matching and gain are the most reliably and repeatably measurable parameters for validating the optimized design.

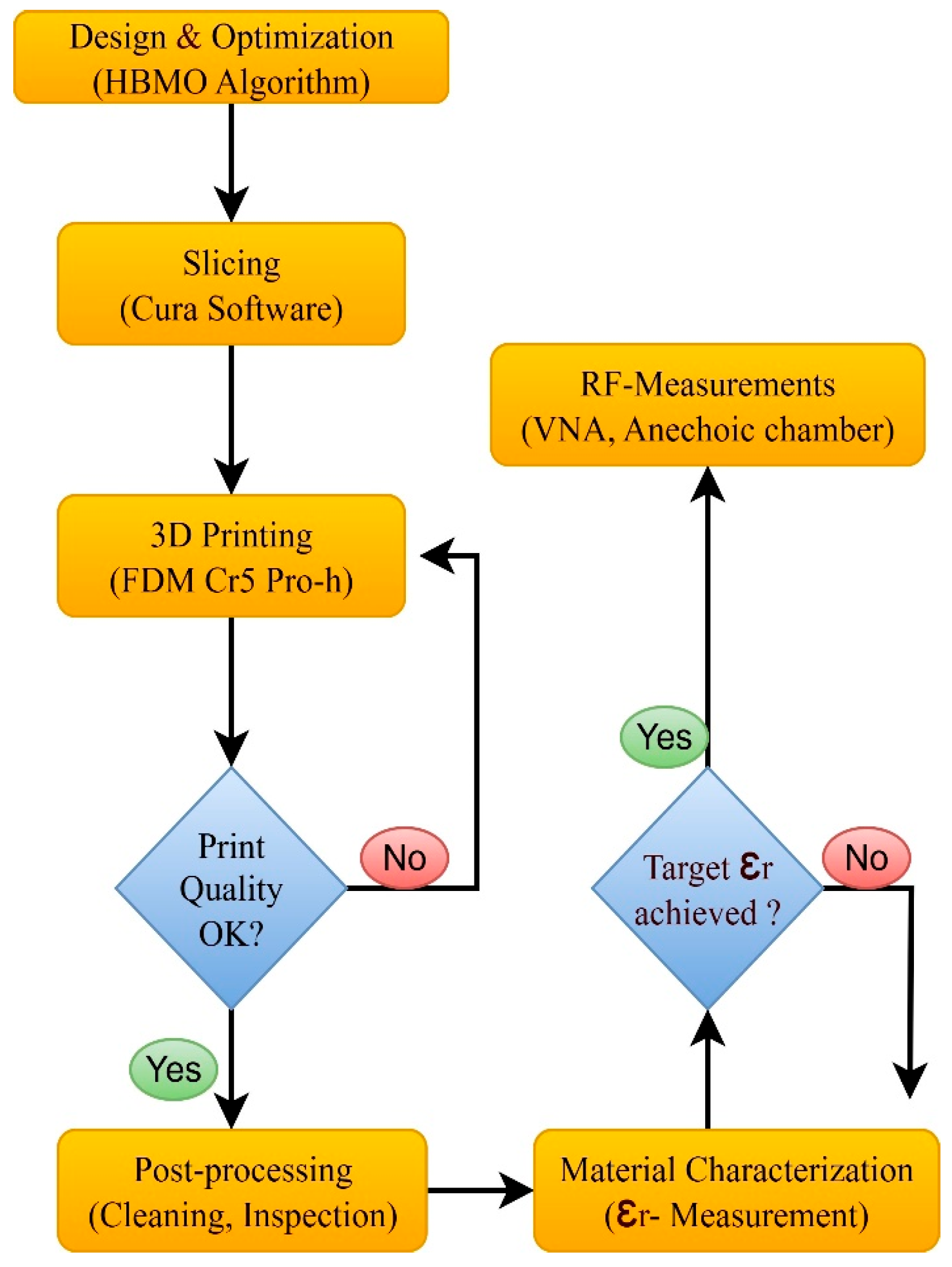

In the next section, the HBMO algorithm is employed to obtain the optimal geometrical design parameters of the antenna that satisfy the targeted performance criteria. To efficiently solve this optimization problem, the Honey Bee Mating Optimization (HBMO) algorithm was adopted as the core optimization engine. HBMO, a swarm-intelligence algorithm inspired by the mating behaviour of honey bee colonies, has recently proven highly effective for addressing multi-objective and nonlinear problems in electromagnetics. Its unique advantage stems from integrating the global search capability of evolutionary algorithms with the probabilistic refinement dynamics of simulated annealing, enabling both exploration and exploitation of the design space. In HBMO, the queen represents the current best solution, while drones correspond to alternative antenna designs defined by the vector “

x”. During the simulated mating flight, the queen probabilistically mates with drones according to their relative fitness values:

where Δ

f is the fitness difference between queen and drone, and

S(

t) denotes the queen’s speed, which decreases over iterations as:

The queen’s energy decays after each mating event:

With

γ being the energy decay factor. The spermatheca acts as a storage unit for drone genetic material, constrained by:

where

is the maximum spermatheca capacity. New candidate solutions are generated via recombination and mutation:

where

is a blending parameter and

is a random perturbation vector. The fitness of each offspring is then recalculated:

The optimization is terminated when the global best fitness stabilizes within a threshold:

In Equation (19) “

” denotes the convergence threshold of the algorithm. When the difference between the best solutions in two consecutive iterations is smaller than this small positive value, the algorithm is considered to have converged. For the proposed monopole antenna, HBMO systematically explored the multidimensional parameter space defined in

Table 2. Each candidate solution represented a unique combination of dielectric radii, permittivity values, and

H1, while the cost function evaluated their performance in terms of S

11, bandwidth, and gain. Through its iterative process, HBMO preserved high-performing solutions, eliminated inferior ones, and maintained diversity via crossover and mutation operations.

HBMO provides high convergence speed and stronger resilience against premature stagnation. This makes it particularly well-suited for the discontinuous and multi-modal nature of the electromagnetic design space. In addition, the flexibility of 3D printing, which enables permittivity control through infill ratio, combined with HBMO-driven optimization, allowed the development of a compact dual-band antenna. The final optimized monopole antenna demonstrates stable performance in both X- and Ku-bands, offering a balanced trade-off among miniaturization, gain, and bandwidth, thereby highlighting the effectiveness of HBMO-based optimization in conjunction with 3D-printed dielectric-loaded antenna structures.

Considering the design parameter constraints given in

Table 2, the cost function guides the HBMO algorithm in performing a global search within the design space to find the optimal antenna design. The HBMO algorithm selects the highest-performing antenna designs, analogous to how the fittest bees are selected in a colony. It then employs a mating strategy, applying crossover and mutation operations to the selected designs to generate a new population with inherited and varied characteristics. This cycle of selection, mating, and mutation is repeated over multiple generations, progressively refining the antenna design parameters and guiding the optimization toward an optimal solution. As a result, the design parameters listed in

Table 3 represent the optimal solutions for the targeted application.

The optimal relative permittivity values obtained using the HBMO algorithm were determined to

= 3,

= 2.4, and

= 2. These values were achieved using ABS300 PREPERM filament.

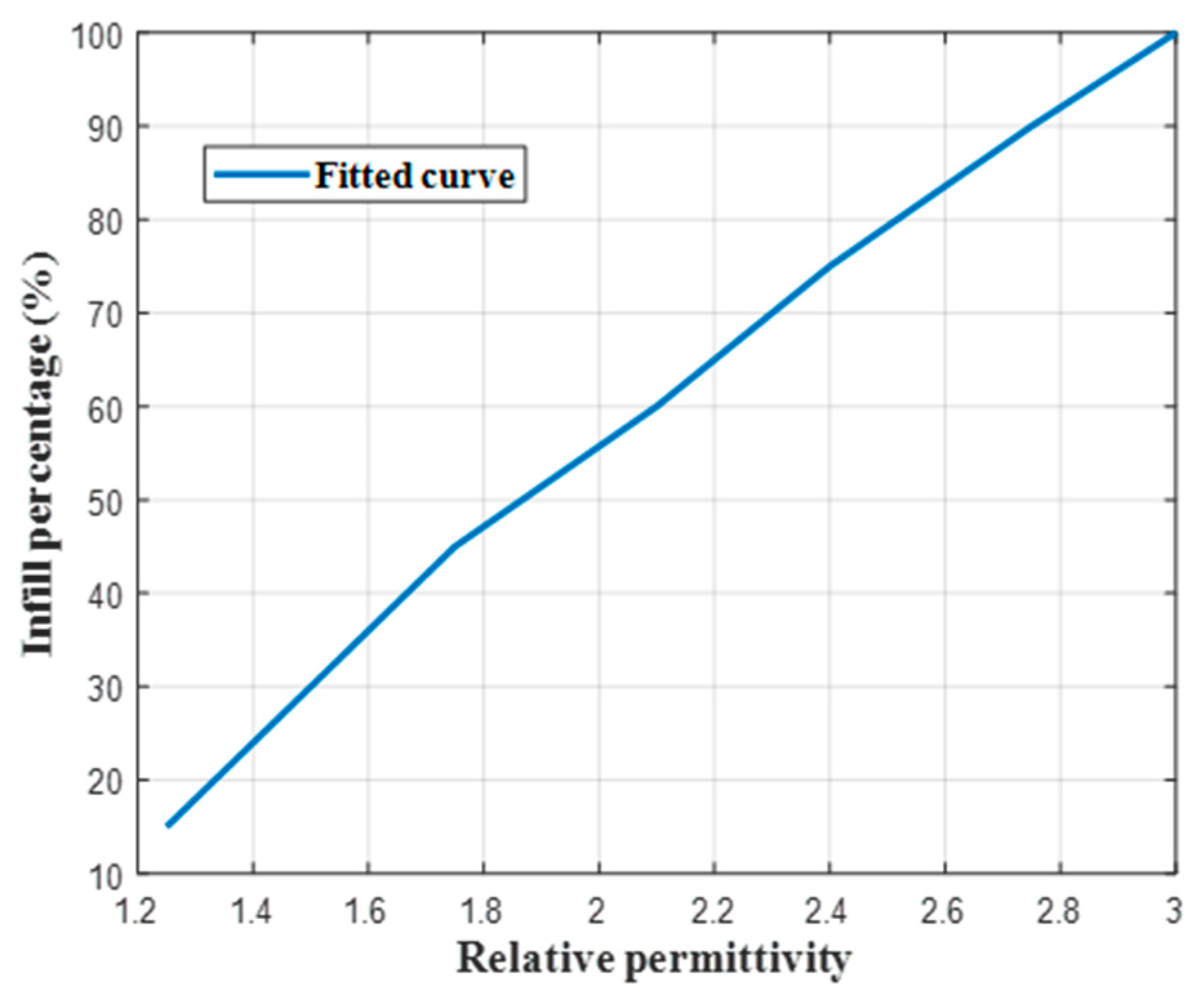

Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between relative permittivity and infill percentage. As shown in

Figure 1, the filament infill percentages were set to 100%, 75%, and 56% to achieve

,

, and

, respectively. A grid pattern was used as the infill geometry in the design.

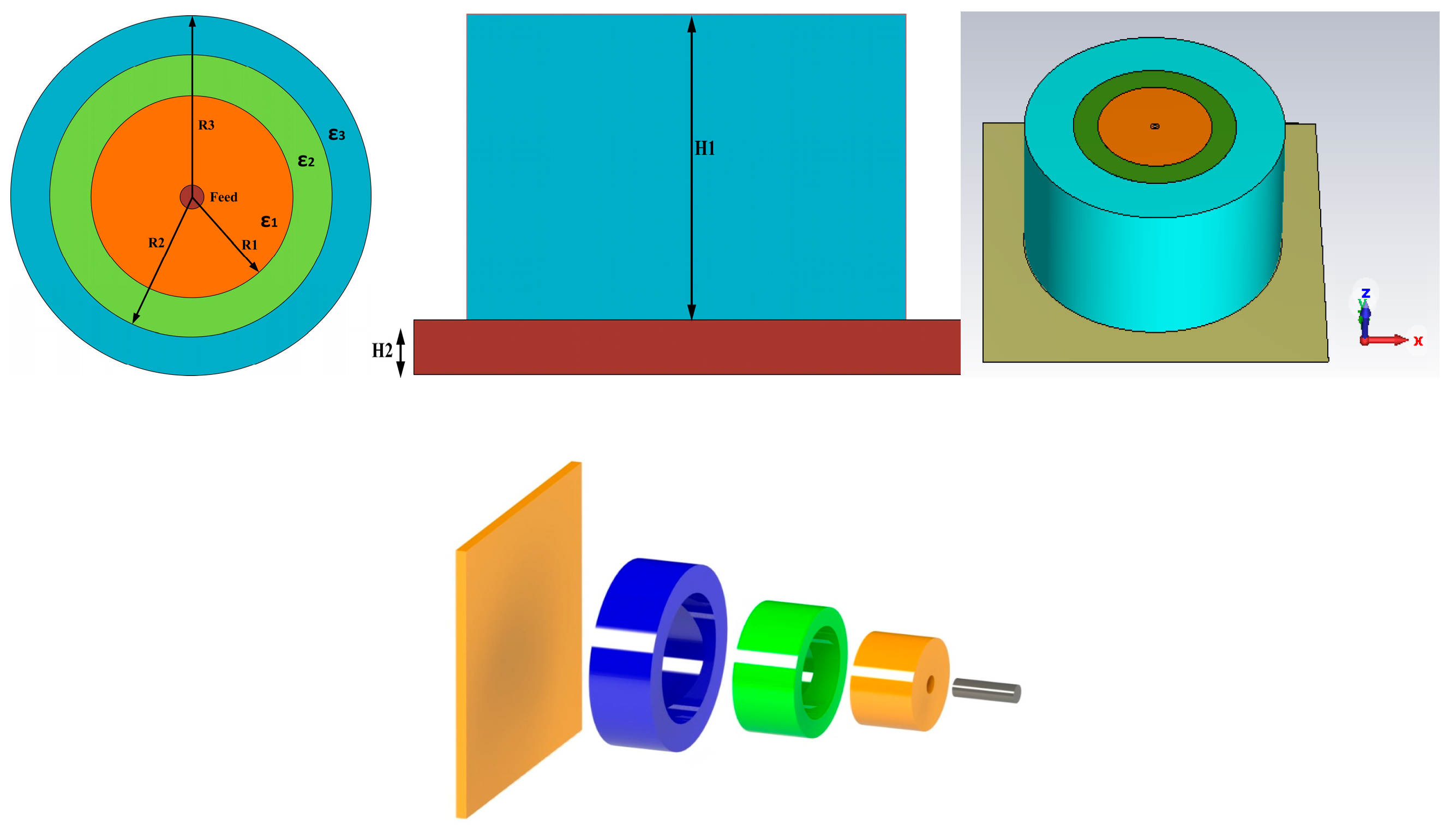

Figure 2 presents the top, side, and perspective views of the proposed cylindrical dielectric-loaded antenna structure. In the top view, the antenna consists of three concentric dielectric regions: the innermost core characterized by

the intermediate annular layer defined by

, and the outermost surrounding region specified by

. These layers are represented by radii

R1,

R2 and

R3, respectively, and are arranged symmetrically around the central feed to control the electromagnetic interaction within the structure. In the side view, the overall height of the dielectric stack is denoted by

H1, whereas

H2 corresponds to the thickness of the metallic ground plane; together, these parameters influence both the resonant frequencies and the radiation characteristics of the antenna.

The perspective views illustrate the three-dimensional configuration of the multilayer cylindrical geometry, highlighting the spatial arrangement and continuity of the dielectric layers. The exploded representation further clarifies how the regions are volumetrically assembled and demonstrates that the antenna is designed in a modular form suitable for straightforward fabrication using additive manufacturing techniques.

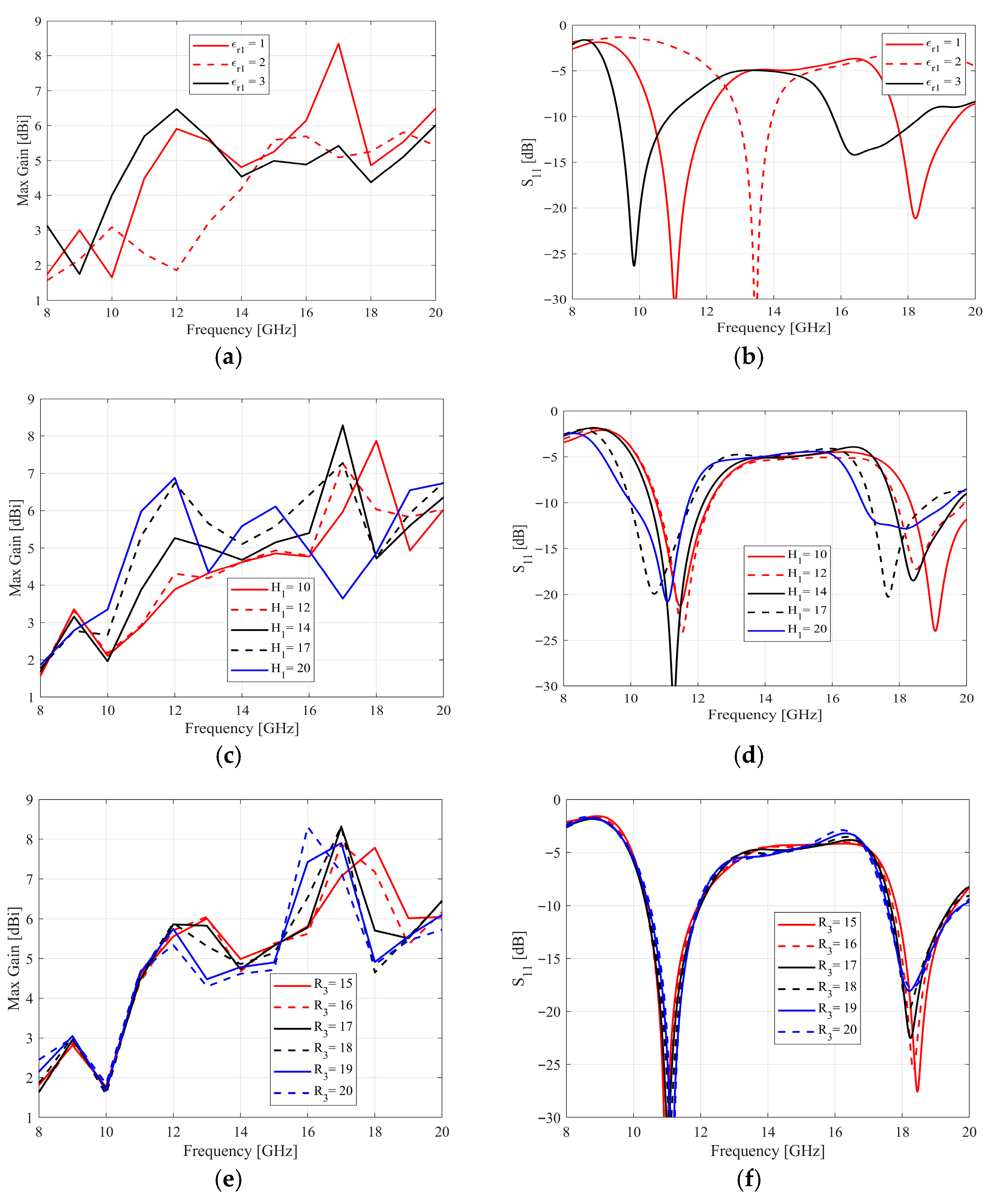

Figure 3 provides a comprehensive sensitivity analysis of the key design variables on the antenna gain and reflection coefficient (S

11), where

,

H1, and

R3 are individually swept while all other parameters are kept constant (

=

=

= 2,

H1 = 15,

R1 = 7.5,

R2 = 12.5,

R3 = 17.5), thereby justifying the robustness and effectiveness of the selected optimization parameters.

The proposed structure is inherently non-homogeneous due to the intentional use of dielectric layers with different relative permittivity values. This design philosophy is closely related to graded-index (GRIN) concepts, which have been widely employed in lens and dielectric antenna designs to manipulate wave propagation, enhance directivity, and achieve controlled beam shaping or focusing. In the present work, the gradual variation in permittivity along the structure establishes a tapered electromagnetic environment that enables a smooth transition between regions with different effective wave impedances. Such a graded permittivity profile mitigates abrupt impedance discontinuities, suppresses internal reflections, and stabilizes the phase progression of the propagating fields. Similar principles have been successfully demonstrated in 3D-printed dielectric antennas with designable permittivity, where tapered dielectric constants were exploited to achieve wideband impedance matching and controlled radiation characteristics [

30]. In this sense, the non-homogeneity of the proposed structure is not a fabrication artifact but a deliberate electromagnetic design strategy that contributes to the observed broadband behavior and stable radiation performance.

4. Results and Discussion

The measured and simulated S

11 parameters of the proposed antenna are compared across the 8–20 GHz frequency range, as illustrated in

Figure 7. Both curves demonstrate two distinct resonances, with measured minima appearing near 10 GHz and 18 GHz, corresponding to the intended X- and Ku-band operation. The measured S

11 reaches values below −25 dB at approximately 10 GHz and below −20 dB at 18 GHz, indicating excellent impedance matching at both bands. According to the measured results, a bandwidth of approximately 1.75 GHz is achieved in the X-band from 9.5 GHz to 11.25 GHz, while a 1.5 GHz bandwidth is obtained in the Ku-band between 17.2 GHz and 18.7 GHz.

The measured S-parameter results reveal two distinct resonance mechanisms responsible for the dual-band operation in the X- and Ku-band regions. The lower-frequency X-band resonance is primarily governed by the conductor-based quarter-wavelength resonance of the metallic monopole. This resonance exhibits strong impedance matching and a deeper S11 minimum, indicating efficient energy transfer from the feed to radiation. Owing to its conductor-dominated nature and relatively higher quality factor, this fundamental monopole mode provides a broader and more pronounced impedance bandwidth in the X-band.

In contrast, the higher-frequency Ku-band resonance originates from dielectric-induced resonant modes supported by the multilayer dielectric sleeve surrounding the monopole. These resonances arise from strong near-field coupling between the metallic radiator and the dielectric layers, enabling the excitation of hybrid conductor–dielectric modes. Unlike the monopole resonance, dielectric-assisted resonances involve different field confinement and energy storage characteristics, which inherently result in a narrower impedance bandwidth and a shallower S11 minimum. Consequently, the observed bandwidth asymmetry between the X- and Ku-bands is a direct outcome of the fundamentally different resonance mechanisms governing each band.

The outer dielectric layer plays a critical role in reinforcing this hybrid resonant behavior. While the introduction of dielectric material increases the effective permittivity and induces a slow-wave effect that influences the electrical length of the monopole, the outer dielectric layer also supports independent resonant modes, consistent with dielectric resonator antenna theory. Its presence enhances electromagnetic field confinement around the radiator, strengthens the coupling between the metallic and dielectric modes, and contributes to improved radiation efficiency. The progressive addition of dielectric layers particularly the outer layer leads to a consistent increase in realized gain across both bands, with a more pronounced impact at higher frequencies, thereby confirming its supportive role in enhancing the overall radiation performance of the antenna.

Although slight shifts and magnitude differences are observed between the simulated (dashed) and measured (black solid) results likely due to fabrication tolerances and material property variations the overall agreement confirms the design’s dual band performance. These results demonstrate that the antenna achieves sufficient bandwidth and low reflection levels in both target bands, validating its suitability for X/Ku-band applications requiring reliable impedance matching and minimal return loss.

Figure 8a presents the comparison between the simulated and measured gain of the proposed antenna. The results demonstrate that the multi-objective optimization strategy enhances the antenna’s dual-band behavior, yielding consistent gain characteristics within the respective −10 dB impedance bandwidths. For the X-band operation (9.5–11.25 GHz), the measured gain varies from approximately 3.4 dBi at the lower band edge (9.5 GHz) to 6.6 dBi at the upper band edge (11.25 GHz). In the Ku-band (17.2–18.7 GHz), the measured gain reaches about 7.1 dBi at 17.2 GHz and 5.3 dBi at 18 GHz.

Figure 8b presents the front-to-back ratio (F/B) evaluated at the operating frequencies of the proposed antenna in the X- and Ku-band ranges. In

Figure 8b, the “×” symbol denotes the extracted front-to-back ratio values at the selected operating frequencies.

Figure 8c illustrates the simulated radiation efficiency of the proposed antenna across the 8–20 GHz frequency range. In

Figure 8c, the dashed line represents the simulated radiation efficiency, while the shaded background region indicates the overall variation range of efficiency across the operating frequency band. The efficiency remains consistently high throughout the operational band, varying approximately between 80% and 92%. In

Figure 8d, the gain variation in the monopole antenna with progressive dielectric loading is presented to clearly illustrate the effect of the outer dielectric layer on the antenna performance, as discussed previously.

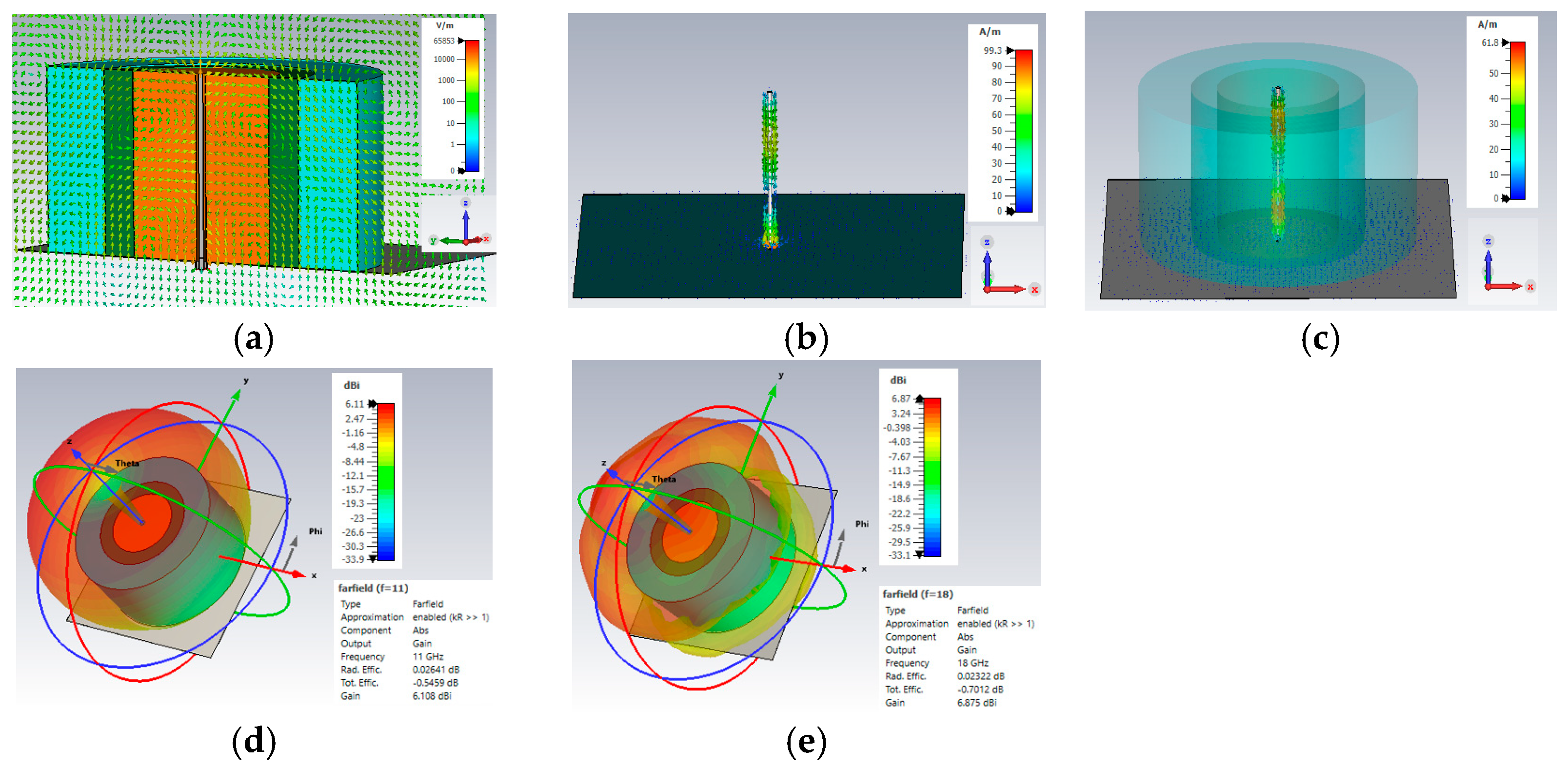

Figure 9 provides a detailed visualization of the electromagnetic field behavior within and around the proposed antenna structure. In

Figure 9a, the electric field distribution is shown across the multi-layer cylindrical dielectric, clearly illustrating how the

,

, and

regions guide and confine the field intensity as it propagates along the monopole. The strong field concentration near the feed and the gradual transition through the dielectric layers demonstrate the effectiveness of the multilayer loading in shaping the radiation mechanism.

Figure 9b presents the magnetic field distribution of the reference monopole without dielectric loading, revealing a relatively narrow and vertically oriented field region typical of an unloaded radiator. In contrast,

Figure 9c shows the magnetic field distribution when the proposed cylindrical dielectric loading is applied. The presence of the

,

layers leads to a more distributed and strengthened magnetic field profile, confirming the enhanced electromagnetic coupling and improved dual-band response provided by the optimized dielectric configuration.

Figure 9d,e display the simulated 3D far-field radiation patterns of the antenna at 11 GHz and 18 GHz, respectively. The electromagnetic behavior of the proposed dielectric-loaded monopole antenna was modeled and simulated using the CST Microwave Studio (version 2023) 3D electromagnetic solver. The radiation envelope at 11 GHz in

Figure 9d shows a well-defined monopole-like directional pattern with a maximum gain of approximately 6.2 dBi. At 18 GHz, as shown in

Figure 9e, the antenna maintains a similarly stable radiation profile, achieving a peak gain of 6.8 dBi. The smooth pattern shapes and consistent main-lobe directions across both frequencies confirm that the proposed dielectric-loaded geometry effectively supports dual-band operation without significant pattern distortion.

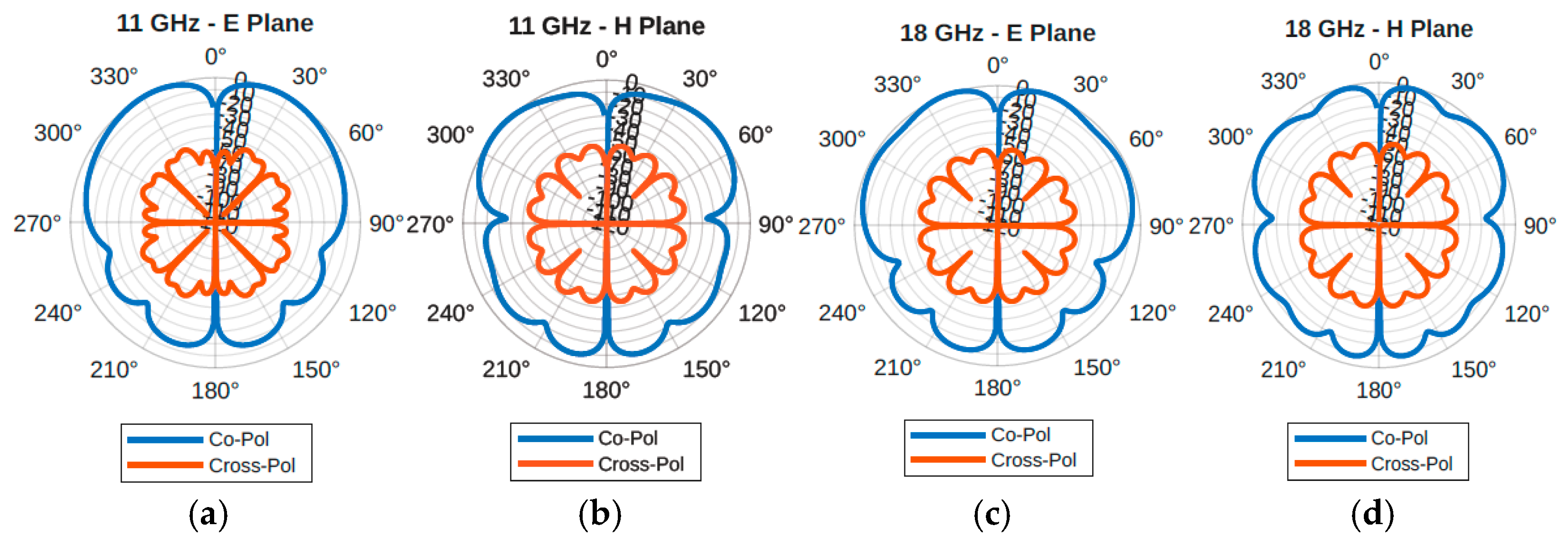

The radiation pattern measurements were carried out in an anechoic chamber to accurately characterize the far-field performance of the proposed antenna. The measurement setup was configured to obtain both co-polarized and cross-polarized radiation patterns in the E-plane and H-plane at the representative operating frequencies of 11 GHz and 18 GHz, corresponding to the two resonance bands of the antenna. During the measurements, the antenna under test (AUT) was mounted on a computer-controlled rotary positioner, allowing precise angular scanning from −180° to +180° with a constant angular step. A standard gain horn antenna, operating over the frequency range of interest, was employed as the reference antenna and was positioned at a distance satisfying the far-field condition. For co-polarized measurements, the polarization of the reference horn antenna was aligned with the dominant polarization axis of the AUT. The received signal level was recorded as a function of the rotation angle, yielding the co-polarized radiation pattern. Subsequently, for cross-polarized measurements, the reference antenna was rotated by 90°, while keeping all other measurement parameters unchanged, in order to capture the orthogonal polarization component. This procedure ensured a consistent and reliable comparison between co-pol and cross-pol characteristics. The E-plane patterns were obtained by fixing the azimuth angle (φ) and rotating the AUT in the elevation plane (θ), whereas the H-plane patterns were measured by fixing the elevation angle and rotating the AUT in the azimuth plane. At each angular position, the received power was sampled and normalized with respect to the maximum measured value to generate the normalized radiation patterns presented in the manuscript.

Experimental uncertainties mainly arise from vector network analyzer calibration, cable and connector losses, and alignment errors on the order of ±1–2° that may occur during radiation pattern measurements. Fabrication tolerances in the proposed antenna are primarily associated with the additive manufacturing process used to realize the dielectric layers. In particular, variations in dielectric layer thickness and effective relative permittivity may occur due to the layer-by-layer deposition process and infill-dependent material distribution. Experimental investigations on PREPERM ABS filaments have shown that the effective permittivity can be reliably controlled through the infill ratio, with typical deviations remaining within ±3–5% under practical printing conditions [

30]. Furthermore, the reported characterization confirms that moderate geometric inaccuracies and surface roughness inherent to fused deposition modeling have a limited influence on the electromagnetic response when the dielectric features are deeply subwavelength.

Figure 10a–d presents the measured 2D polar radiation patterns of the proposed cylindrical dielectric-loaded monopole antenna in both the E- and H-planes at 11 GHz and 18 GHz, including co-polarized and cross-polarized components. At 11 GHz, the

φ = 0° cut corresponds to the E-plane (

Figure 10a), while the

φ = 90° cut represents the H-plane (

Figure 10b). In both planes, the co-polarized radiation exhibits a dominant main lobe directed around

θ = 0°, indicating a broadside radiation characteristic, whereas the cross-polarized component remains significantly lower than the co-polarized level across most angular directions. Similarly, the radiation patterns at 18 GHz in the E- and H-planes (

Figure 10c and

Figure 10d, respectively) demonstrate comparable behavior, with the co-polarized patterns preserving the main-beam direction and overall lobe structure, while the cross-polarized radiation is effectively suppressed relative to the co-polarized component. Minor variations in sidelobe levels and pattern symmetry are observed due to the increased operating frequency.

The reference antennas listed in

Table 5 were selected based on their suitability for dual-band operation in the X- and Ku-bands, the use of comparable antenna topologies, and the availability of clearly reported polarization characteristics and validation approaches. It should be noted that the bandwidth values reported in

Table 5 are adopted directly from the original references. While all studies define the operating bandwidth based on an impedance matching criterion of (S

11 < −10 dB). In addition to designs operating in the X- and Ku-band ranges [

33,

34], a representative dual-band monopole antenna operating in the L- and S-band [

35] ranges is also included in the comparison, in order to enable a broader evaluation of gain and physical size performance across different frequency regimes. For a fair and frequency-independent comparison, the electrical sizes of all antennas listed in

Table 5 are expressed in terms of the free-space wavelength (

) evaluated at the lowest operating frequency band of each design. The comparison results demonstrate that the proposed antenna, despite its compact geometry, achieves maximum gain values that indicate a strong potential to compete with the antenna designs reported in the literature. Furthermore, unlike earlier 3D-printed implementations that rely on spherical geometries [

36] or homogeneous dielectrics, the presented design leverages a multilayer PREPERM ABS300 structure optimized through the HBMO algorithm, offering improved dual-band behavior without increasing physical size.