MDB-YOLO: A Lightweight, Multi-Dimensional Bionic YOLO for Real-Time Detection of Incomplete Taro Peeling

Abstract

1. Introduction

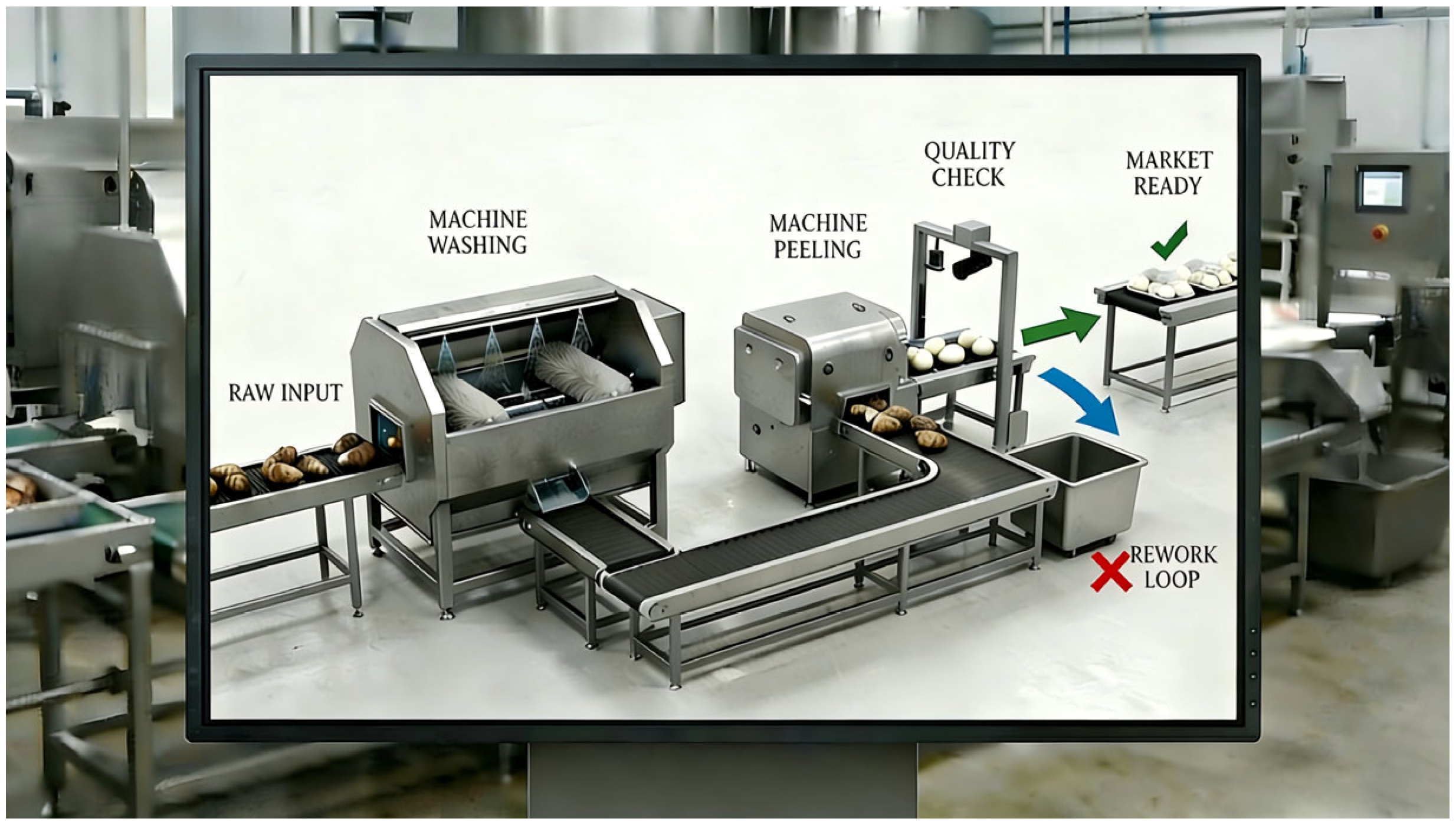

1.1. Industrial Context and Motivation

1.2. Problem Analysis and Data Characteristics

1.2.1. Challenge 1: Tiny Targets and Texture Interference

1.2.2. Challenge 2: Irregular Morphology

1.2.3. Challenge 3: Dense Occlusion and Stacking

1.3. Contributions

- (1)

- Construction of the Taro Peel Industrial Dataset (TPID): We established the first high-resolution, expert-annotated benchmark specifically for taro peeling defects. Comprising 18,341 densely annotated instances across 1056 images, the TPID incorporates a “Human-in-the-Loop” annotation protocol to ensure ground truth fidelity. It explicitly models industrial variables—including motion blur, illumination fluctuations, and object rotation—to rigorously map the stochastic distribution of real-world production environments.

- (2)

- Proposal of the MDB-YOLO Bionic Architecture: We designed a novel, lightweight detection framework that integrates three “bionic” attention mechanisms to resolve specific physical bottlenecks:

- Texture-Scale Adaptation: The integration of the C2f_EMA module with Wise-IoU (WIoU) employs efficient multi-scale attention to amplify the feature response of minute, low-contrast residues while preventing gradient contamination from low-quality examples.

- Geometric Reconstruction: A dynamic feature processing chain utilizing DySample for morphology-aware upsampling and ODConv2d for adaptive feature extraction allows the network to dynamically adjust its sampling field to fit the amorphous boundaries of peel fragments.

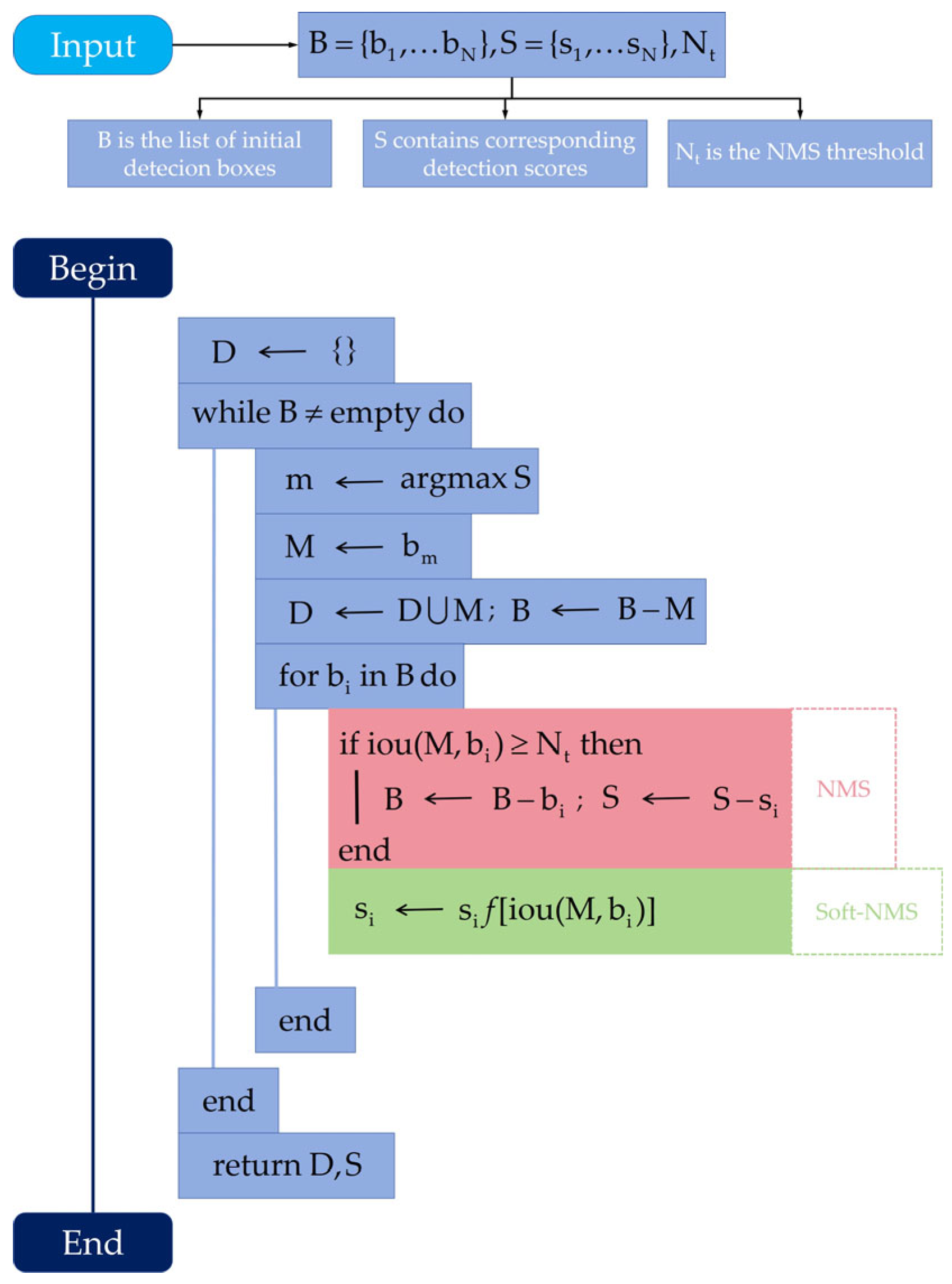

- Occlusion Management: The implementation of Soft-NMS with Gaussian decay effectively mitigates the recall drop caused by dense stacking on conveyor belts.

- (3)

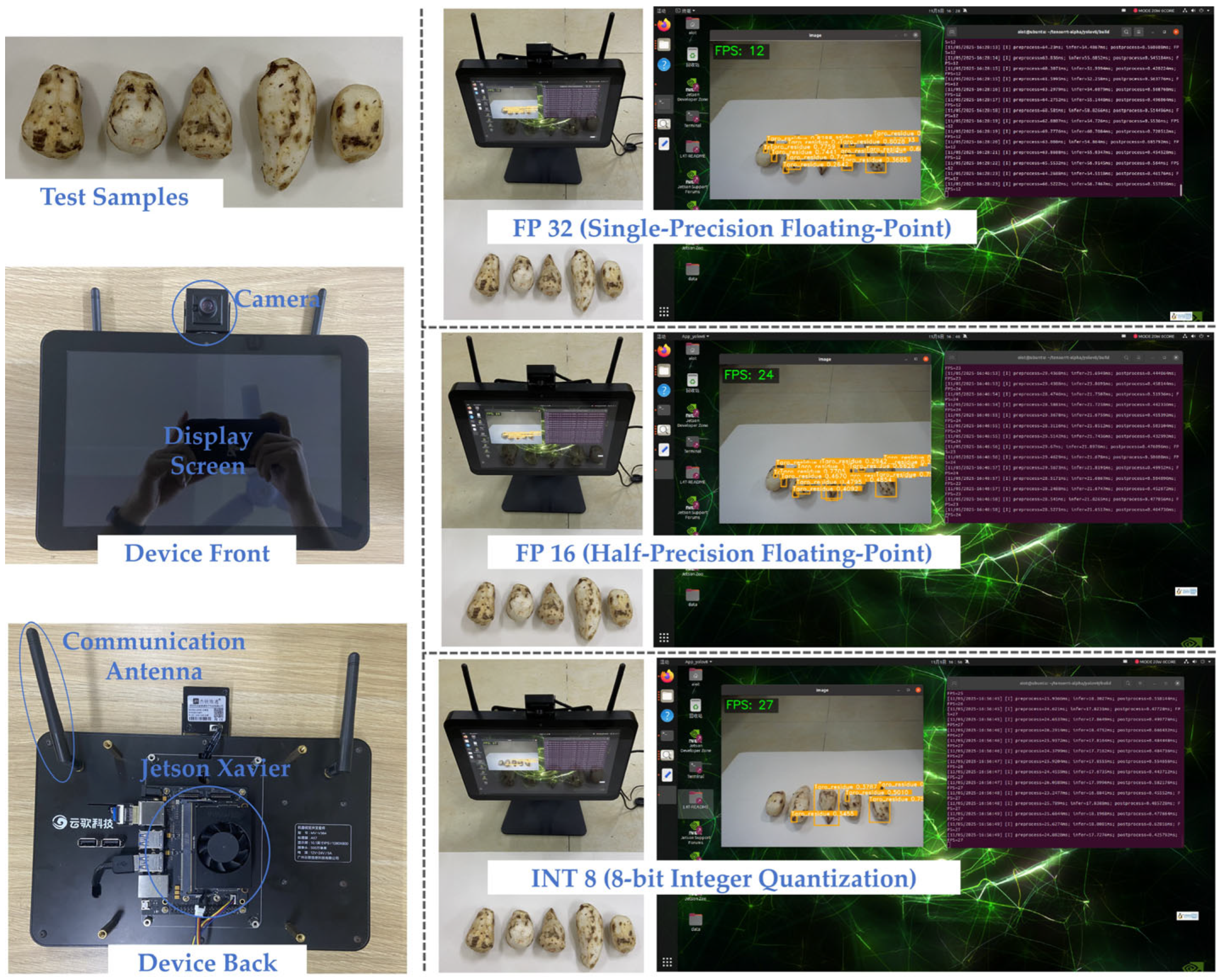

- Validation of High-Performance Edge Deployment: We demonstrated the practical viability of the model on an NVIDIA Jetson Xavier NX (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA) embedded platform. MDB-YOLO achieves a state-of-the-art mAP50-95 of 69.7%, significantly outperforming the baseline YOLOv8s and heavy transformer-based models (RT-DETR-L). Crucially, it maintains a real-time inference speed of 27 FPS (INT8 quantization), satisfying the strict throughput requirements of industrial manufacturing.

1.4. Organization of the Paper

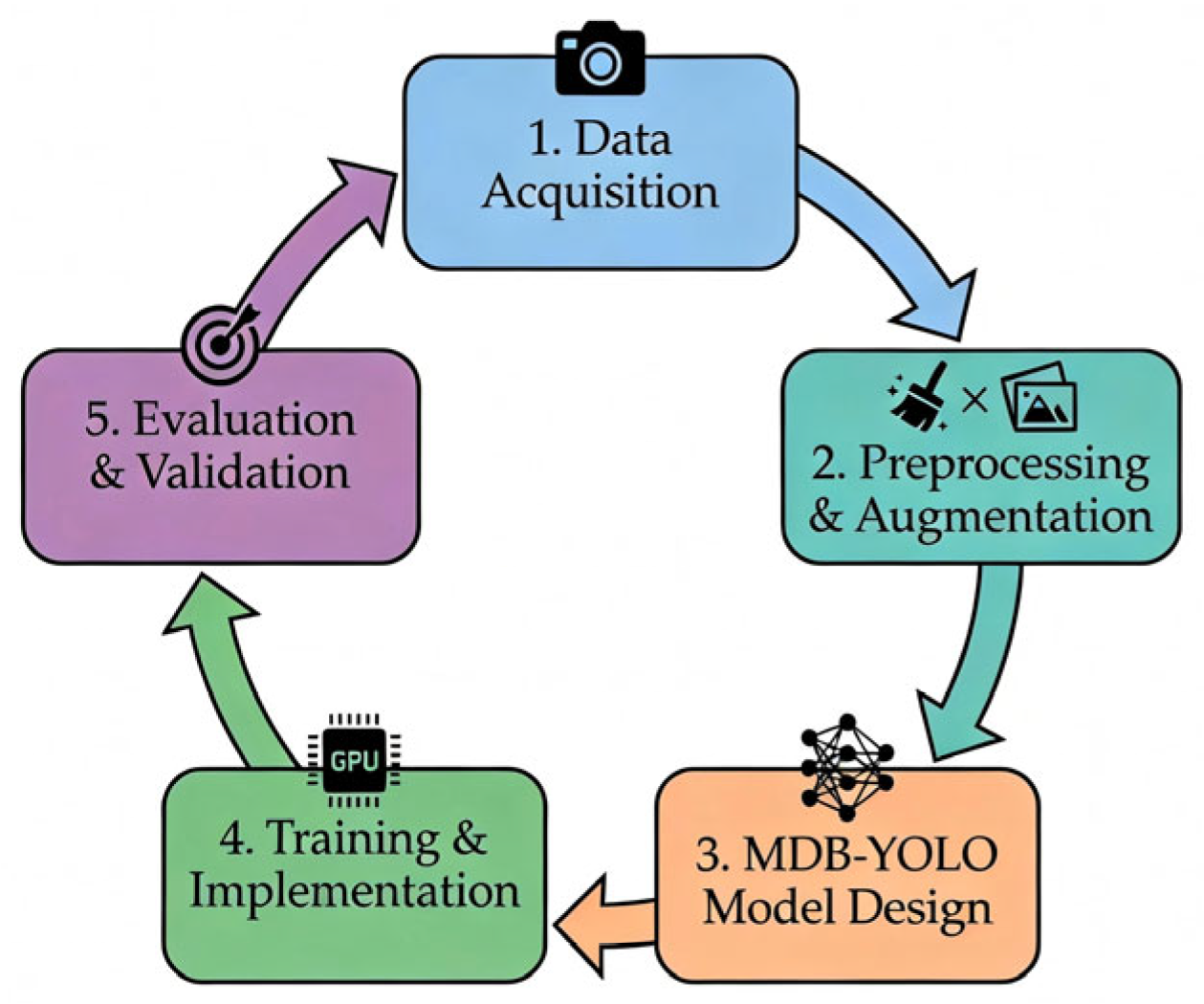

2. Methodology

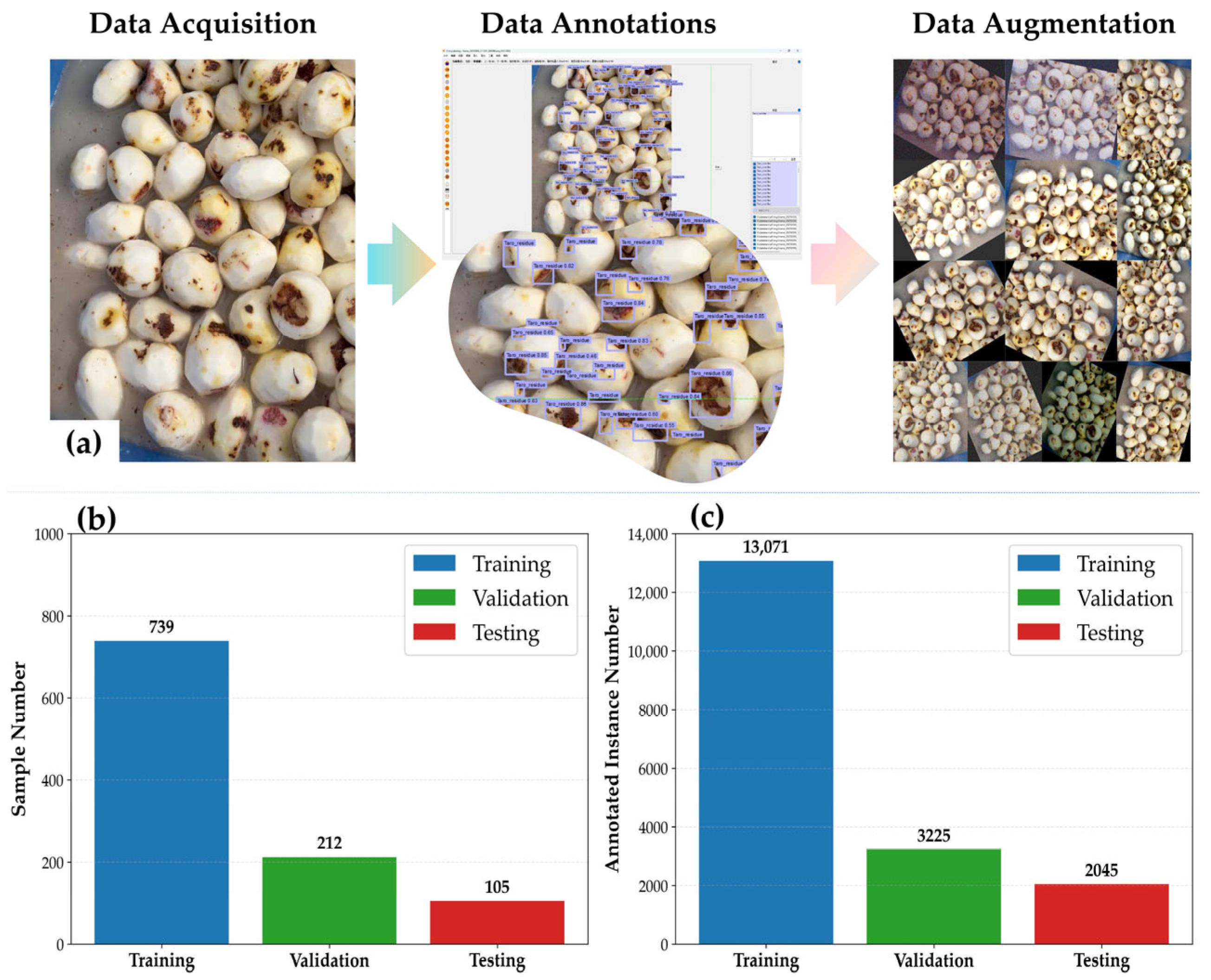

2.1. Taro Peel Industrial Dataset (TPID) Construction

2.1.1. Data Acquisition Infrastructure

2.1.2. Data Preprocessing and Augmentation Strategy

- Photometric Distortion (Addressing Lighting Variability): The factory environment is subject to lighting fluctuations throughout the day and across different seasons. To prepare the model for this, we applied random brightness and contrast adjustments (p = 0.6) and RGB channel shifting (p = 0.4). Additionally, we utilized Contrast Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization (CLAHE) (p = 0.2). Unlike global histogram equalization, which can amplify noise in the uniform background regions, CLAHE operates on small tiles and limits the contrast amplification. This is particularly effective for enhancing the local contrast between the peel and the flesh without overexposing the white taro body, thereby highlighting minute textural differences.

- Geometric Transformations (Addressing Pose Variability): Taro tubers are roughly spherical or ellipsoidal and roll randomly on the conveyor belt. Consequently, there is no fixed orientation for the defects; “up” and “down” are relative. To force the model to learn rotation-invariant features, we applied horizontal and vertical flips (p = 0.5), random 90-degree rotations (p = 0.7), and affine transformations including translation, scaling, and slight rotation (p = 0.5). This simulates the chaotic positioning of the taro as it moves down the line.

- Motion Blur Simulation (Addressing Conveyor Dynamics): Despite the use of industrial cameras with fast shutters, the relative motion of the conveyor belt (often moving at speeds > 0.5 m/s) can introduce slight motion blur. We applied Gaussian blur (p = 0.1) to a subset of training images. This forces the model to learn to “find edges in the blur,” enhancing its robustness to speed variations and mechanical vibrations inherent in the machinery.

- Mosaic Augmentation: We utilized Mosaic augmentation, which stitches four training images into a single composite. This technique is particularly valuable for small object detection as it significantly increases the number of objects per training batch and varies the background context. However, it is worth noting that while helpful for the initial training phases, this was strategically disabled in the final fine-tuning epochs to align with the real-world data distribution where images are single frames, not composites.

2.1.3. Annotation and Dataset Splitting

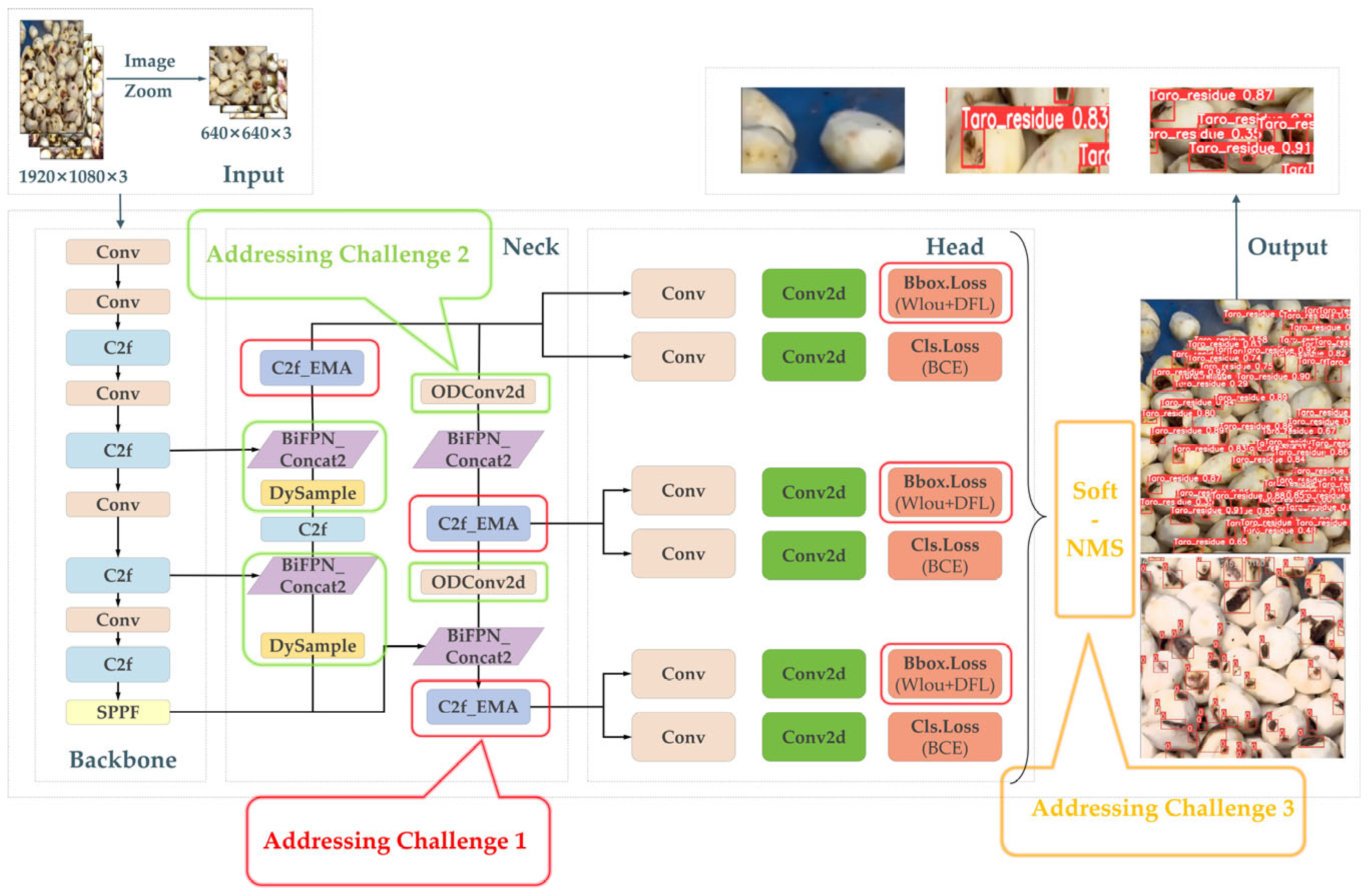

2.2. The MDB-YOLO Architecture

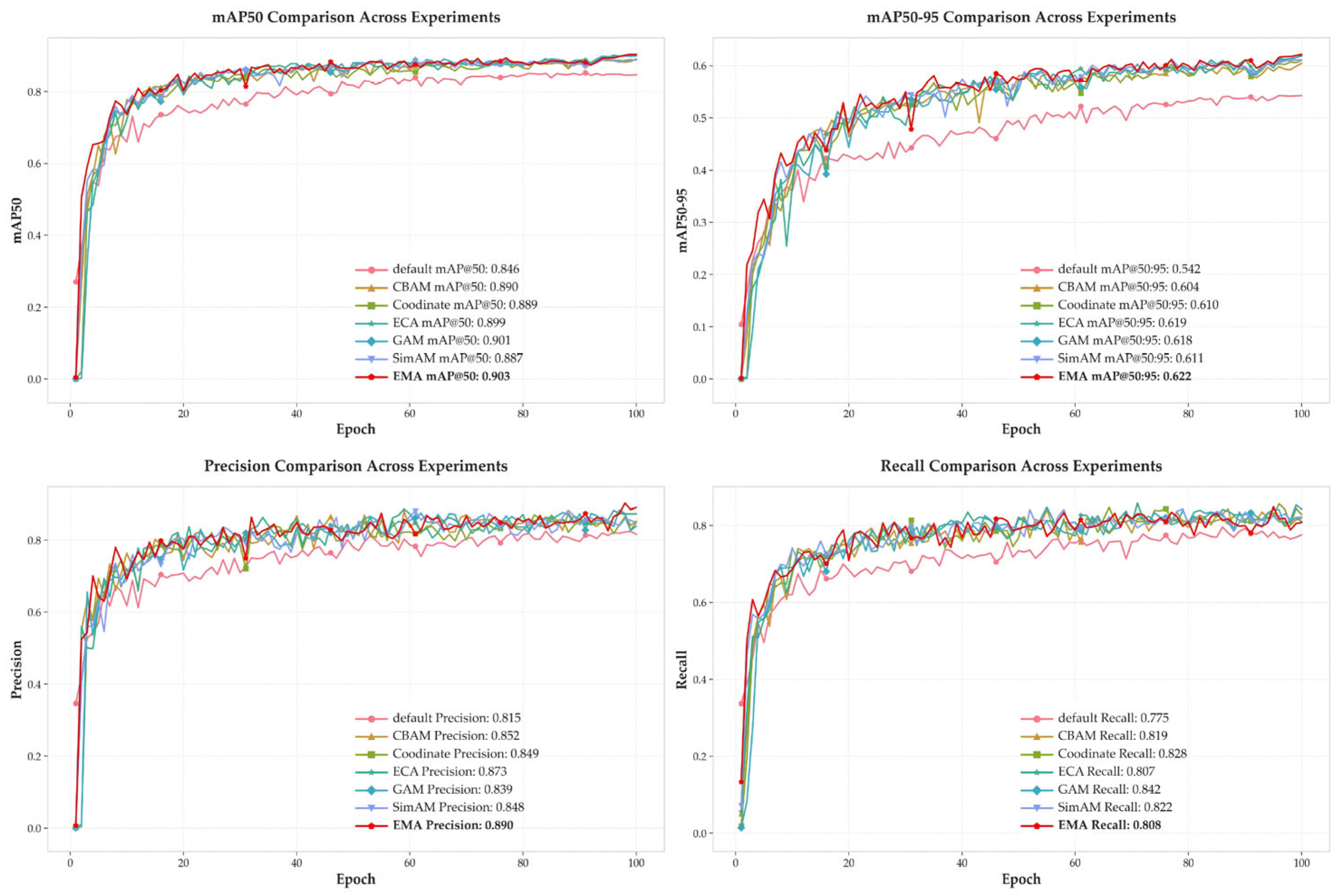

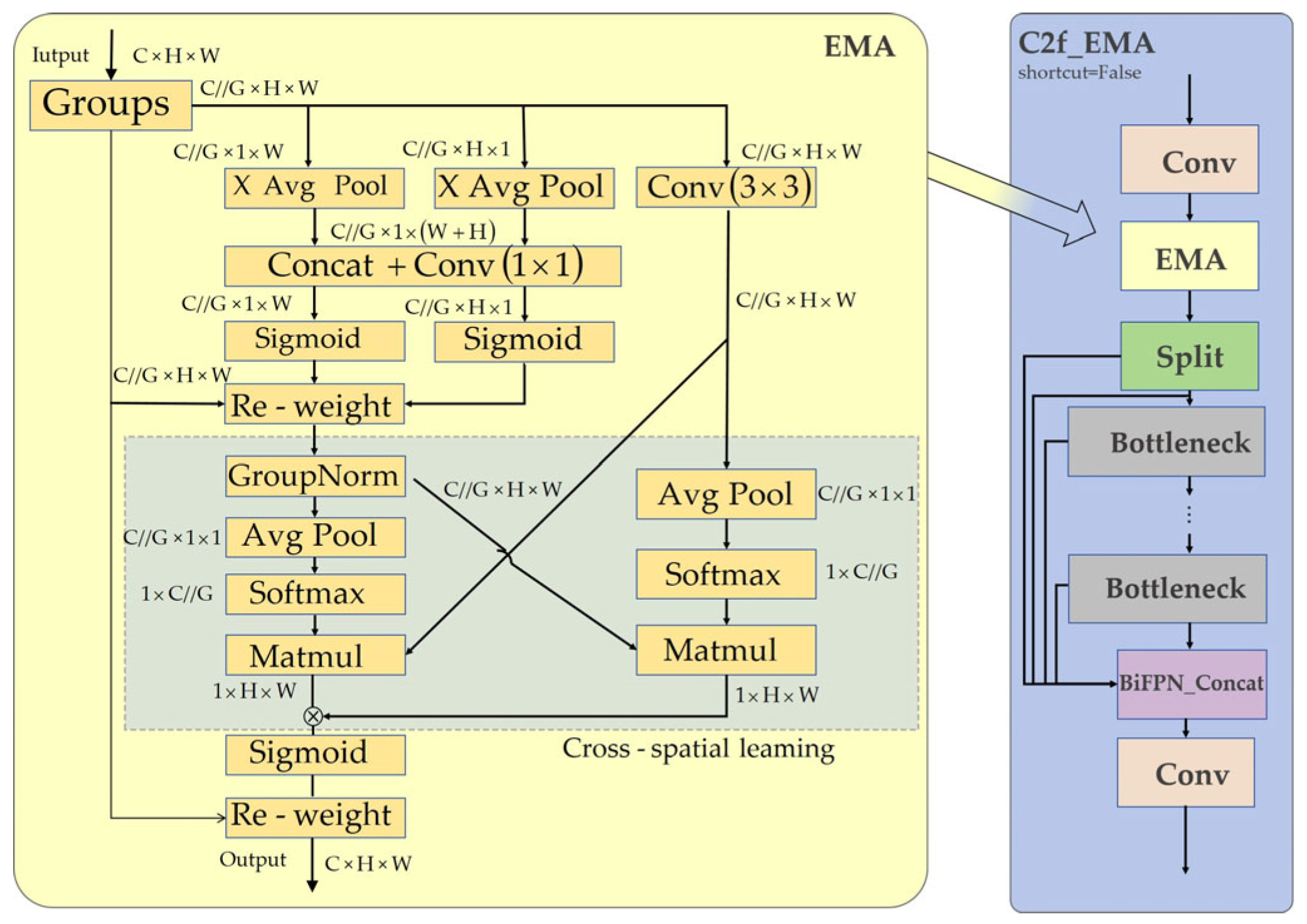

2.2.1. Addressing Challenge 1: The C2f_EMA Module and WIoU

2.2.2. Addressing Challenge 2: The Dynamic Feature Processing Chain

- (1)

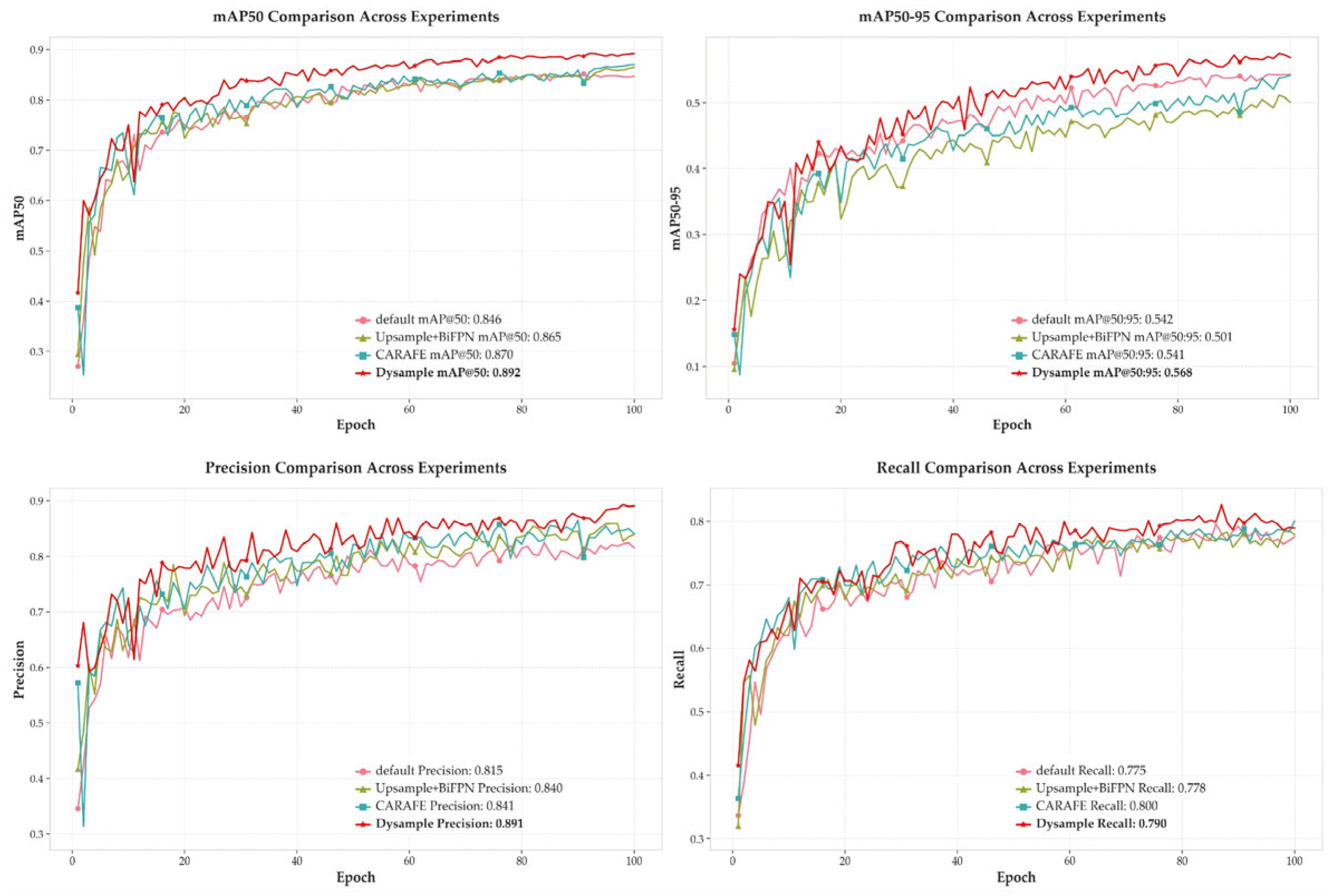

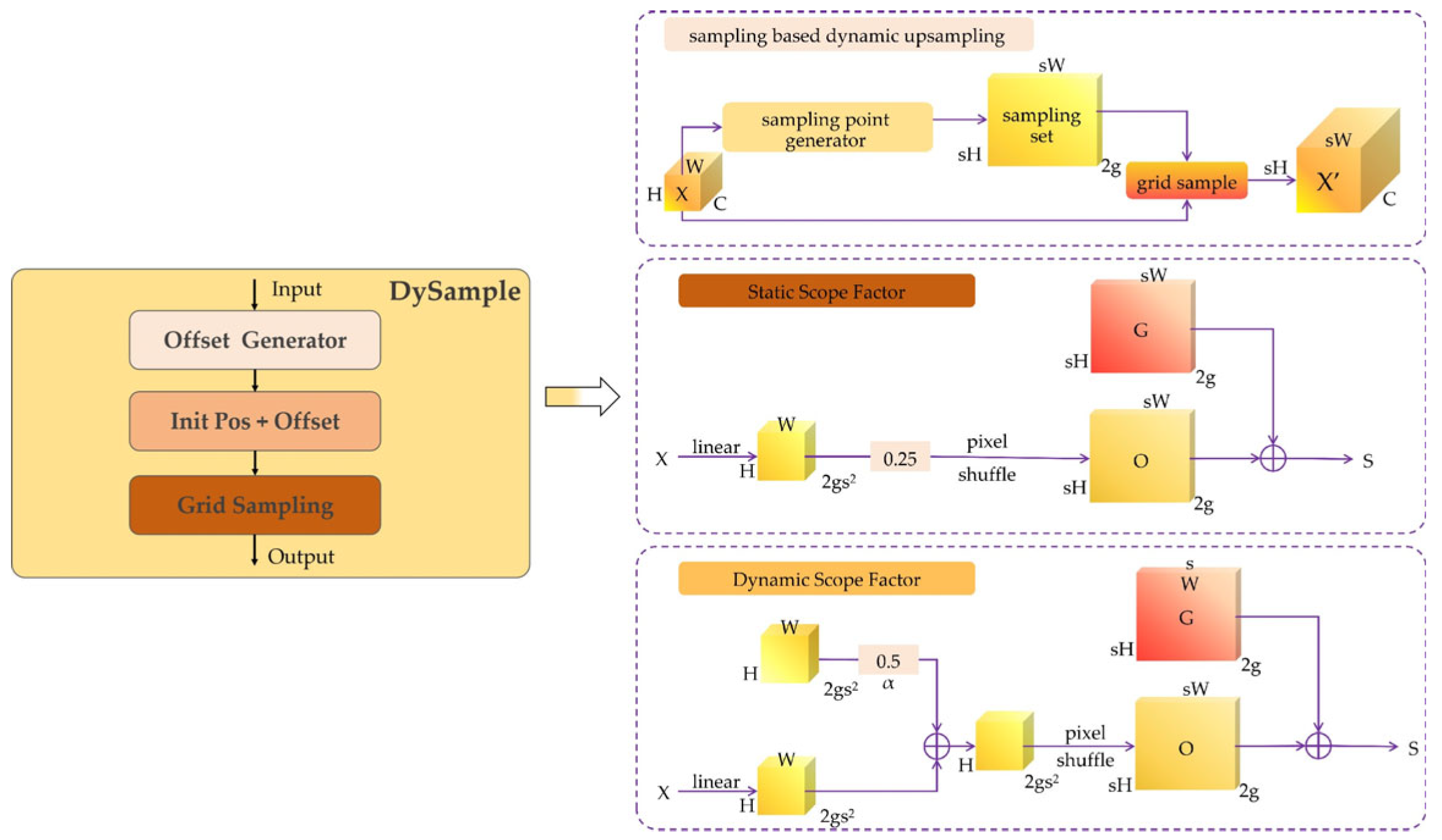

- Morphology Reconstruction (DySample): Standard upsampling (Nearest Neighbor Interpolation) is static; it simply duplicates pixels to increase resolution. For a curved, thin piece of peel, this results in a jagged, blocky edge that loses the original shape information—a phenomenon known as aliasing. We replaced this with DySample, a dynamic upsampling module [29]. We experimentally validated this choice against other upsampling methods, as detailed in Table 2.

- (2)

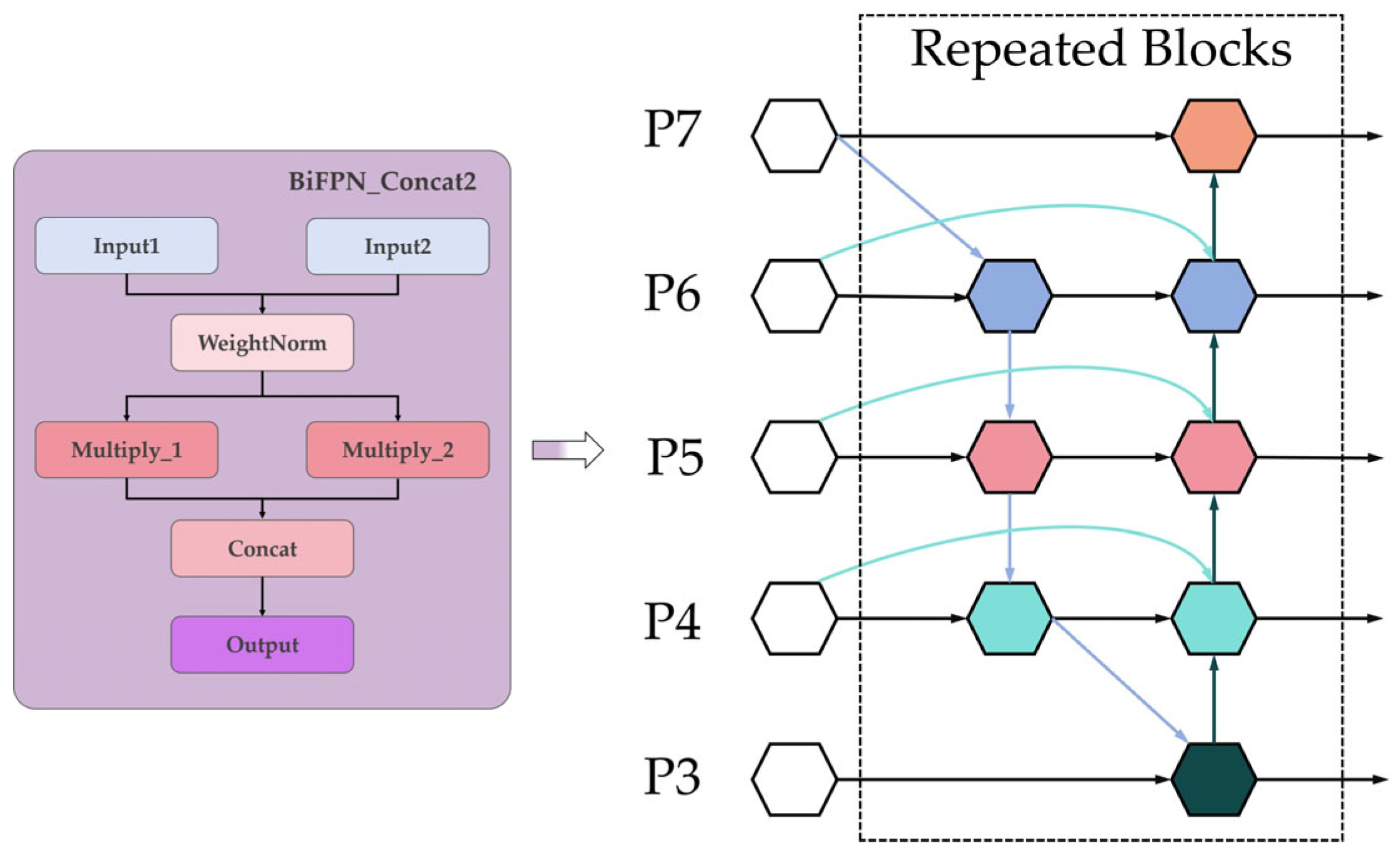

- Weighted Fusion (BiFPN_Concat2): Merging features from different scales is critical for detecting objects of varying sizes. The standard YOLOv8 uses a simplistic addition (summation) fusion [31,32]. However, this implicitly assumes that deep semantic features (from P5) and shallow textural features (from P3) are equally important. For our task, the shallow texture information is often more critical for identifying the peel than the abstract semantics. We adopted a modified BiFPN_Concat2 structure. This module utilizes learnable weights (wi) to balance the contribution of different feature inputs: It allows the network to automatically assign higher importance to the shallow layers when processing tiny texture-heavy targets. Furthermore, we use Concatenation rather than addition, preserving the full dimensionality of the features for subsequent processing. Figure 9 contrasts our weighted concatenation approach with the standard BiFPN design. This ensures that the subtle texture signals of tiny residues are not “washed out” by the stronger signals of larger objects [33,34].

- (3)

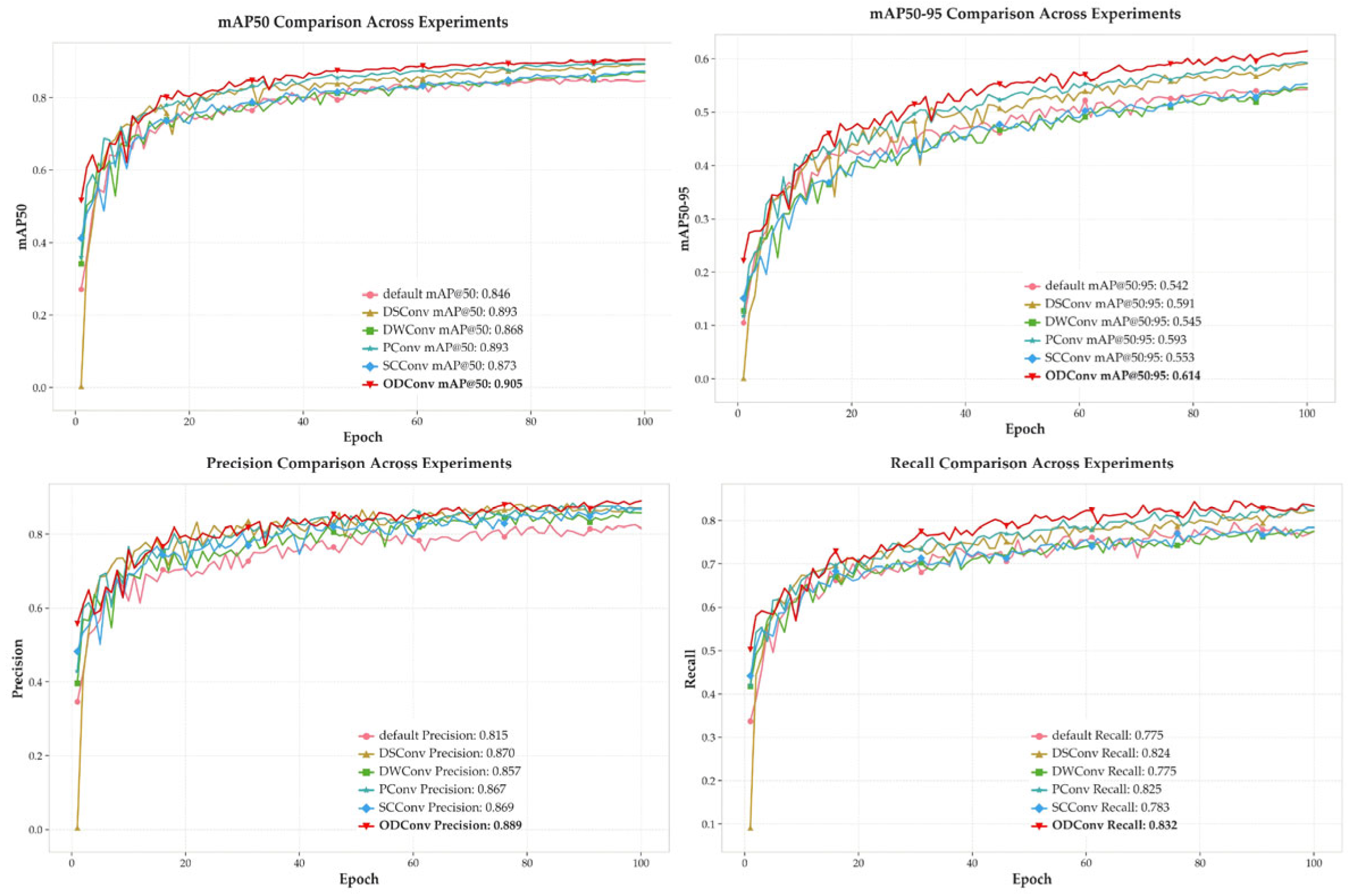

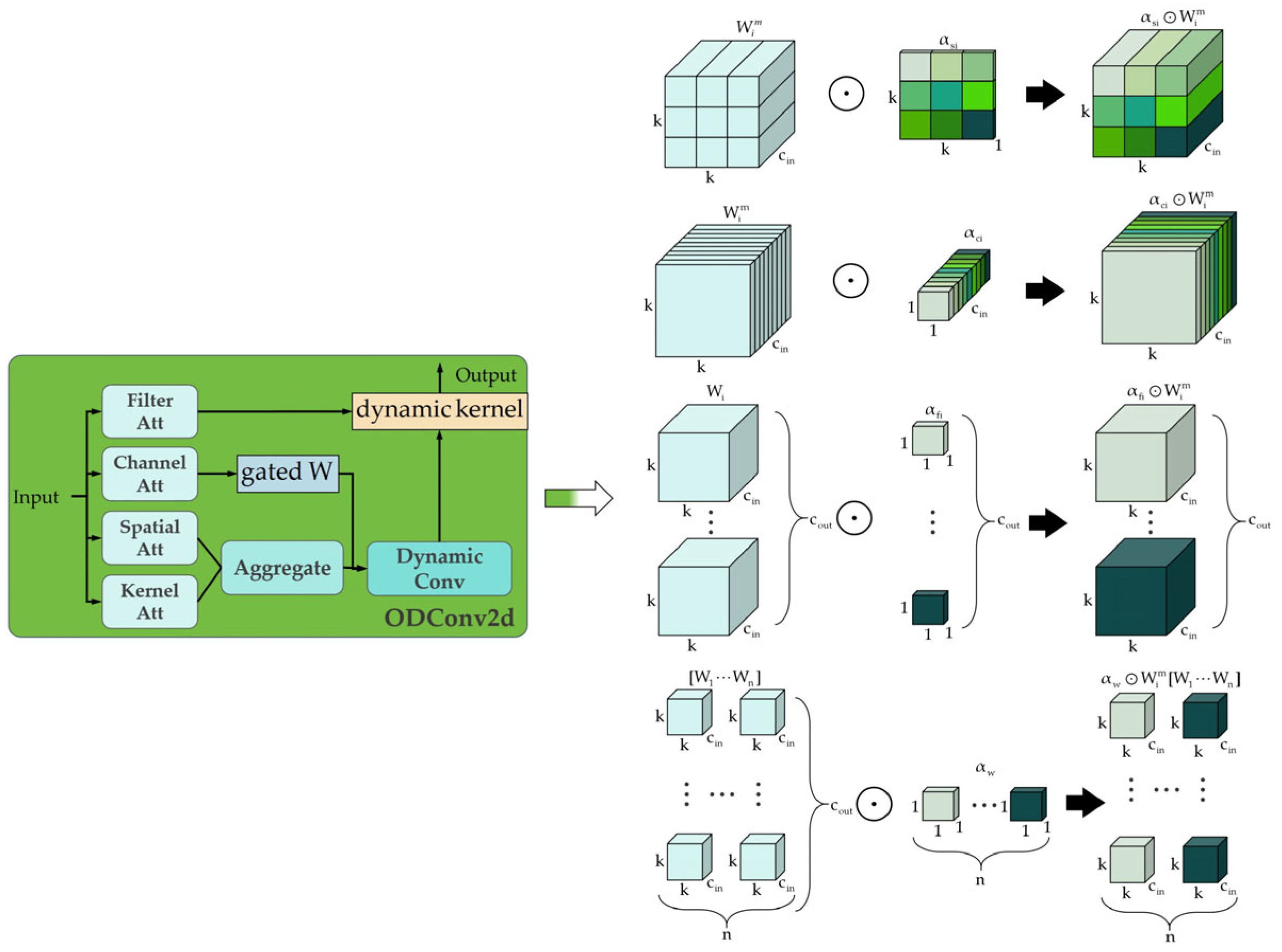

- Geometric Preservation (ODConv2d): Finally, in the downsampling path, we employ Omni-Dimensional Dynamic Convolution (ODConv2d) [35]. Standard static convolutions use a single kernel weight matrix for all inputs. ODConv2d, however, learns a multi-dimensional attention mechanism that dynamically modulates the convolution kernel across four dimensions: the spatial kernel size (αs), the input channels (αc), the output channels (αo), and the kernel number (αw). This means the convolution filter itself changes shape and emphasis based on the input. The superiority of ODConv over other dynamic convolution methods for our task is demonstrated in Table 3.

2.2.3. Addressing Challenge 3: Soft-NMS for Dense Occlusion

2.2.4. Model Layer Configuration and Complexity Analysis

2.3. Implementation Details and Training Configuration

3. Experimental Results and Analysis

3.1. Experimental Setup and Evaluation Metrics

3.2. Ablation Studies: Validating the Bionic Mechanisms

- Impact of C2f_EMA and WIoU: Comparing the baseline (Exp. 1) to the enhanced model (Exp. 2), the introduction of C2f_EMA and WIoU improved Precision from 0.892 to 0.905 and mAP50 from 90.8% to 91.7%. This confirms that the attention mechanism effectively highlights the tiny targets, while the robust loss function improves the quality of the bounding boxes by preventing overfitting to ambiguous boundaries.

- Impact of Soft-NMS: Perhaps the most dramatic single-step improvement came from replacing NMS with Soft-NMS (Exp. 1 vs. Exp. 4). With no other changes, mAP50-95 jumped from 65.7% to 68.6%. This 2.9% increase serves as powerful proof of the “dense occlusion” hypothesis—valid targets were indeed being suppressed by the baseline model, and Soft-NMS successfully recovered them.

- Impact of the Dynamic Chain: The combination of DySample, BiFPN_Concat2, and ODConv2d (Exp. 14) yielded a balanced improvement in both precision and recall. Specifically, DySample contributed a net growth of 0.9% in mAP50-95 compared to standard upsampling (Exp. 11 vs. Exp. 14), validating its ability to reconstruct irregular edges. ODConv2d further pushed Precision to 0.916 in intermediate experiments (Exp. 6), demonstrating its capacity to fit feature extraction to target geometry.

- Cumulative Performance: The final configuration (Exp. 20), which combined all modules with the optimized training strategy (closing Mosaic), achieved the peak performance: mAP50-95 of 69.7% and Recall of 88.0%. This represents a substantial leap over the baseline’s 65.7% mAP and 85.2% Recall, demonstrating the additive value of the proposed modifications.

3.3. Hyperparameter Experiments

3.4. Comparative Analysis with Prominent Models

- False Negatives (Missed Detections): All competitor models frequently fail to identify actual peel fragments, particularly those that are small or have low contrast. This is a critical failure for a quality control system;

- False Positives (Incorrect Detections): Multiple models, particularly the baseline YOLOv8s along with the YOLOv9s, v12s, and v13s, misidentify features of the conveyor belt, including the black seams, as defects. This phenomenon would result in an unacceptably high false-alarm rate in a production setting.

3.5. Edge Device Deployment and Quantitative Analysis

3.5.1. Deployment Hardware and Software Environment

3.5.2. Model Export and Optimization Pipeline

3.5.3. TensorRT Quantization Standards

- FP32 (Single-Precision): Uses 32-bit floating-point numbers for weights and activations. This maintains the highest theoretical accuracy, identical to the training environment, but has the slowest inference speed and highest memory footprint.

- FP16 (Half-Precision): Uses 16-bit floating-point format. It provides a significant boost in computation speed and memory bandwidth with a minimal and often negligible (typically <0.5%) loss in precision, making it ideal for real-time detection tasks.

- INT8 (8-bit Integer Quantization): Converts weights and activations to 8-bit integers. This standard maximizes inference efficiency and achieves the lowest latency, making it perfectly suited for highly resource-constrained edge devices, provided the (typically <2%) accuracy loss is acceptable for the task.

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Architectural Improvements

4.2. Performance vs. Efficiency Trade-Off

4.3. Economic Impact of the Precision–Recall Trade-Off

4.4. Hardware Compatibility and Deployment Feasibility

4.5. Limitations and Future Work

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDB-YOLO | Multi-Dimensional Bionic YOLO |

| YOLO | You Only Look Once |

| TPID | Taro Peel Industrial Dataset |

| EMA | Efficient Multi-Scale Attention |

| C2f | CSP 2-stage Feature fusion |

| DySample | Dynamic Upsampling |

| ODConv | Omni-Dimensional Dynamic Convolution |

| BiFPN | Bidirectional Feature Pyramid Network |

| WIoU | Wise-IoU |

| NMS | Non-Maximum Suppression |

| Soft-NMS | Soft Non-Maximum Suppression |

| mAP | mean Average Precision |

| TP | True Positives |

| FP | False Positives |

| FN | False Negatives |

| CLAHE | Contrast Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization |

| FPS | Frames Per Second |

| ONNX | Graphics Processing Units |

| GFLOPS | Open Neural Network eXchange |

| TensorRT | NVIDIA Tensor RunTime |

| FPN | Feature Pyramid Network |

| CIoU | Complete IoU |

| CRI | Color Rendering Index |

| INT8 | 8-bit Integer |

| FP16 | 16-bit Floating Point (Half-Precision) |

| FP32 | 32-bit Floating Point (Single-Precision) |

| AIoT | Artificial Intelligence of Things |

| IoU | Intersection over Union |

| P | Precision |

| R | Recall |

| AP | Average Precision |

References

- Temesgen, M.; Retta, N. Nutritional potential, health and food security benefits of taro Colocasia esculenta (L.): A review. Food Sci. Qual. Manag. 2015, 36, 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Kühlechner, R. Object detection survey for industrial applications with focus on quality control. Prod. Eng. 2025, 19, 1271–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogidi, O.I.; Wenapere, C.M.; Chukwunonso, O.A. Enhancing Food Safety and Quality Control With Computer Vision Systems. In Computer Vision Techniques for Agricultural Advancements; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 51–88. [Google Scholar]

- Dhal, S.B.; Kar, D. Leveraging artificial intelligence and advanced food processing techniques for enhanced food safety, quality, and security: A comprehensive review. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, S.; Dixit, A.K.; Shrivastav, A. Development and performance optimization of a taro (Colocasia esculenta) peeling machine for enhanced efficiency in small-scale farming. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 11336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, B.; Gebeyehu, S.; Kirui, L.; Maru, J. The contribution of potato to food security, income generation, employment, and the national economy of Ethiopia. Potato Res. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.; Ma, J.; Wang, Q.; Sun, D.W. Applications of machine learning techniques for enhancing nondestructive food quality and safety detection. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 1649–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, C.; Xue, N.; Li, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, X. Automatic cassava disease recognition using object segmentation and progressive learning. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2025, 11, e2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, F.; Guo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lv, H.; Zeng, F.; Lv, C. Improved YOLO v5s-based detection method for external defects in potato. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1527508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Zhong, M.; Zhu, W.; Rashid, A.; Han, R.; Virk, M.; Duan, K.; Zhao, Y.; Ren, X. Advances in computer vision and spectroscopy techniques for non-destructive quality assessment of citrus fruits: A comprehensive review. Foods 2025, 14, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Hua, Z.; Wen, Y.; Deng, H.; Zhao, Y.; Pu, L.; Song, H. Using an improved lightweight YOLOv8 model for real-time detection of multi-stage apple fruit in complex orchard environments. Artif. Intell. Agric. 2024, 11, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yun, L.; Yang, C.; Wu, M.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z. OW-YOLO: An improved YOLOv8s lightweight detection method for obstructed walnuts. Agriculture 2025, 15, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Gao, H.; Jia, Z.; Li, Z. BL-YOLOv8: An improved road defect detection model based on YOLOv8. Sensors 2023, 23, 8361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Wang, L.; Wu, L. An improved YOLOv8 algorithm for rail surface defect detection. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 44984–44997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Lyu, S.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Q. TPH-YOLOv5: Improved YOLOv5 Based on Transformer Prediction Head for Object Detection on Drone-captured Scenarios. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV) Workshops, Montreal, BC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 2778–2788. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, K.; O’Bryan, C.A.; Marcy, J.A.; Crandall, P.G. Detection and prevention of foreign material in food: A review. Heliyon 2023, 9, e02262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.W. Computer Vision Technology for Food Quality Evaluation, 1st ed.; Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Xiao, T.; Jiang, Y.; Shao, S.; Sun, J.; Shen, C. Repulsion Loss: Detecting Pedestrians in a Crowd. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 7774–7783. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, D.; He, S.; Zhang, G.; Luo, M.; Guo, H.; Zhan, J.; Huang, Z. Efficient multi-scale attention module with cross-spatial learning. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Rhodes Island, Greece, 4–10 June 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kweon, I.S. Cbam: Convolutional block attention module. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Q.; Zhou, D.; Feng, J. Coordinate attention for efficient mobile network design. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 13713–13722. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Wu, B.; Zhu, P.; Li, P.; Zuo, W.; Hu, Q. ECA-Net: Efficient channel attention for deep convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 11534–11542. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Shao, Z.; Hoffmann, N. Global attention mechanism: Retain information to enhance channel-spatial interactions. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2112.05561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, R.Y.; Li, L.; Xie, X. Simam: A simple, parameter-free attention module for convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Virtual, 18–24 July 2021; pp. 11863–11874. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, Z.; Chen, Y.; Xu, Z.; Yu, R. Wise-IoU: Bounding box regression loss with dynamic focusing mechanism. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.10051. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Z.; Wang, P.; Liu, W.; Li, J.; Ye, R.; Ren, D. Distance-IoU loss: Faster and better learning for bounding box regression. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New York, NY, USA, 7–12 February 2020; pp. 12993–13000. [Google Scholar]

- Gevorgyan, Z. SIoU Loss: More than a Penalty Term. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2205.12740. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.F.; Ren, W.; Zhang, Z.; Jia, Z.; Wang, L.; Tan, T. Focal and efficient IOU loss for accurate bounding box regression. Neurocomputing 2022, 506, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Lu, H.; Fu, H.; Cao, Z. Learning to upsample by learning to sample. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 2–6 October 2023; pp. 6027–6037. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Chen, K.; Xu, R.; Liu, Z.; Loy, C.C.; Lin, D. Carafe: Content-aware reassembly of features. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 3007–3016. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Hariharan, B.; Belongie, S. Feature pyramid networks for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 2117–2125. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Qi, L.; Qin, H.; Shi, J.; Jia, J. Path aggregation network for instance segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 8759–8768. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Pang, R.; Le, Q.V. EfficientDet: Scalable and Efficient Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 10781–10790. [Google Scholar]

- Doherty, J.; Gardiner, B.; Kerr, E.; Siddique, N. Bifpn-yolo: One-stage object detection integrating bi-directional feature pyramid networks. Pattern Recognit. 2025, 160, 111209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhou, A.; Yao, A. Omni-dimensional dynamic convolution. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Virtual, 25–29 April 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, Y.; He, Y.; Qi, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, G. Dynamic snake convolution based on topological geometric constraints for tubular structure segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 2–6 October 2023; pp. 6070–6079. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, A.G.; Zhu, M.; Chen, B.; Kalenichenko, D.; Wang, W.; Weyand, T.; Andreetto, M.; Adam, H. Mobilenets: Efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.04861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Kao, S.H.; He, H.; Zhuo, W.; Wen, S.; Lee, C.H.; Chan, S.H.G. Run, don’t walk: Chasing higher FLOPS for faster neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 12021–12031. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Wen, Y.; He, L. SCConv: Spatial and Channel Reconstruction Convolution for Feature Redundancy. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 6153–6162. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Bi, T.; Tian, C. An Omni-Dimensional Dynamic Convolutional Network for Single-Image Super-Resolution Tasks. Mathematics 2025, 13, 2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodla, N.; Singh, B.; Chellappa, R.; Davis, L.S. Soft-NMS--improving object detection with one line of code. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 5561–5569. [Google Scholar]

- Jocher, G.; Chaurasia, A.; Qiu, J. Ultralytics YOLO. 2024. Available online: https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Wang, C.Y.; Yeh, I.H.; Liao, H.Y.M. YOLOv9: Learning what you want to learn using programmable gradient information. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.13616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Chen, H.; Liu, L.; Chen, K.; Lin, Z.; Han, J.; Ding, G. YOLOv10: Real-Time End-to-End Object Detection. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.14458. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Ye, Q.; Doermann, D. YOLOv12: Attention-Centric Real-Time Object Detectors. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.12524. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, M.; Li, S.; Gao, Y. YOLOv13: Real-Time Object Detection with Hypergraph-Enhanced Adaptive Visual Perception. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.17733. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Lv, W.; Xu, S.; Wei, J.; Wang, G.; Dang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J. Detrs beat yolos on real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 17–21 June 2024; pp. 16965–16974. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Zheng, J.; Wan, W.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, Z. RT-DETR-EVD: An Emergency Vehicle Detection Method Based on Improved RT-DETR. Sensors 2025, 25, 3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siméoni, O.; Vo, H.V.; Seitzer, M.; Baldassarre, F.; Oquab, M.; Jose, C.; Khalidov, V.; Szafraniec, M.; Yi, S.; Ramamonjisoa, M.; et al. Dinov3. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.10104. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Shan, X.; Yan, Y.; Liu, C.; Lu, L.; Ji, X.; Chen, J. RT-DETRv4: Painlessly Furthering Real-Time Object Detection with Vision Foundation Models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2510.25257. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y.; Li, H.; Wu, P.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, X.; Wu, F. D-FINE: Redefine Regression Task in DETRs as Fine-grained Distribution Refinement. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Singapore, 24–28 April 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla, R.; Netto, S.L.; Da Silva, E.A. A survey on performance metrics for object-detection algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Systems, Signals and Image Processing (IWSSIP), Niterói, Brazil, 1–3 July 2020; pp. 237–242. [Google Scholar]

- Bochkovskiy, A.; Wang, C.-Y.; Liao, H.-Y.M. YOLOv4: Optimal Speed and Accuracy of Object Detection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.10934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Dollár, P.; Zitnick, C.L. Microsoft COCO: Common objects in context. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Zurich, Switzerland, 6–12 September 2014; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 740–755. [Google Scholar]

- Khalili, B.; Smyth, A.W. SOD-YOLOv8—Enhancing YOLOv8 for Small Object Detection in Traffic Scenes. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.04786. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, C.; Zhang, T.; Zheng, Y. Full-Scale Feature Aggregation and Grouping Feature Reconstruction-Based UAV Image Target Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5621411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Fu, Y.; Gu, L.; Yan, C.; Harada, T.; Huang, G. Frequency-Aware Feature Fusion for Dense Image Prediction. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 46, 4756–4771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yu, C.; Cheng, J.; Wang, Z.J.; Chen, X. MM-Net: A Mixformer-Based Multi-Scale Network for Anatomical and Functional Image Fusion. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2024, 33, 2197–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Er, M.J.; Chen, J.; Wu, J.G. Marine object detection based on improved YOLOv5. In Proceedings of the 2022 5th International Conference on Intelligent Autonomous Systems (ICoIAS), Fuzhou, China, 13–15 May 2022; pp. 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, J.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, K.; Wang, Z.; Yao, L. Dynamic Background Reconstruction via Masked Autoencoders for Infrared Small Target Detection. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 135, 108762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, C.D.; Le, T.M.D.; Do, T.H.; Bui, N.M.; Nguyen, T.H.; Ngo, Q.U.; Ngo, P.T.; Bui, D.T. Improving YOLOv8 Deep leaning model in rice disease detection by using Wise-IoU loss function. J. Meas. Control Autom. 2025, 29, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xu, C.; Zhang, S. Inner-IoU: More Effective Intersection over Union Loss with Auxiliary Bounding Box. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.02877. [Google Scholar]

| Epochs | mAP50 | mAP50-95 | Precision | Recall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| default (-) | 100 | 0.8466 | 0.5425 | 0.8157 | 0.7755 |

| GAM | 100 | 0.9 | 0.6184 | 0.8392 | 0.8424 |

| SimAM | 100 | 0.887 | 0.6112 | 0.8484 | 0.8223 |

| ECA | 100 | 0.8995 | 0.6196 | 0.8732 | 0.8099 |

| Coordinate | 100 | 0.8891 | 0.6104 | 0.8499 | 0.8284 |

| CBAM | 100 | 0.8904 | 0.6046 | 0.8528 | 0.8192 |

| EMA | 100 | 0.903 | 0.6217 | 0.8909 | 0.8078 |

| Epochs | mAP50 | mAP50-95 | Precision | Recall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| default (Upsample) | 100 | 0.8466 | 0.5425 | 0.8157 | 0.7755 |

| Upsample + BiFPN | 100 | 0.8648 | 0.501 | 0.8395 | 0.7788 |

| CARAFE | 100 | 0.8706 | 0.5414 | 0.841 | 0.8003 |

| Dysample | 100 | 0.8917 | 0.5681 | 0.891 | 0.7896 |

| Epochs | mAP50 | mAP50-95 | Precision | Recall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| default (Conv) | 100 | 0.8466 | 0.5425 | 0.8157 | 0.7755 |

| DSConv [36] | 100 | 0.8934 | 0.5916 | 0.87 | 0.824 |

| DWConv [37] | 100 | 0.8688 | 0.5456 | 0.8571 | 0.7758 |

| PConv [38] | 100 | 0.8936 | 0.5931 | 0.8673 | 0.8251 |

| SCConv [39] | 100 | 0.8735 | 0.5533 | 0.8693 | 0.7839 |

| ODConv | 100 | 0.905 | 0.6142 | 0.8895 | 0.8326 |

| Module Type | Configuration & Function | Feature Map Size (Stride) |

|---|---|---|

| Conv & C2f | CSPDarknet Backbone. Standard feature extraction path (P1–P5). Note: SPPF is used at the end (Layer 9). | P3: (80 × 80)/P4: (40 × 40)/P5: (20 × 20) |

| DySample | Dynamic Upsampling. Replaces nearest interpolation. Upsamples P5 features (20 × 20 → 40 × 40) with point-sampling. | 40 × 40 |

| BiFPN_Concat2 | Weighted Fusion. Fuses upsampled P5 with P4 backbone features using learnable weights. | 40 × 40 |

| C2f | Feature processing after fusion. | 40 × 40 |

| DySample | Dynamic Upsampling. Upsamples P4 features (40 × 40 → 80 × 80). | 80 × 80 |

| BiFPN_Concat2 | Weighted Fusion. Fuses upsampled P4 with P3 backbone features. | 80 × 80 |

| C2f_EMA | Small Object Refinement. Processes the high-resolution P3 feature map using EMA Attention to focus on tiny peel residues. | 80 × 80 (Stride 8) |

| ODConv2d | Dynamic Downsampling. Compresses P3 features (80 × 80 → 40 × 40) using Omni-Dimensional Dynamic Convolution for shape adaptability. | 40 × 40 |

| BiFPN_Concat2 | Weighted Fusion. Fuses downsampled features with previous P4 features. | 40 × 40 |

| C2f_EMA | Medium Object Refinement. Refines P4 features with EMA Attention. | 40 × 40 (Stride 16) |

| ODConv2d | Dynamic Downsampling. Compresses P4 features (40 × 40 → 20 × 20). | 20 × 20 |

| BiFPN_Concat2 | Weighted Fusion. Fuses downsampled features with P5 features (from Layer 9). | 20 × 20 |

| C2f_EMA | Large Object Refinement. Refines P5 features with EMA Attention. | 20 × 20 (Stride 32) |

| Detect | Decoupled Head. Performs final bounding box regression (using WIoU) and classification. | Output Layers |

| Category | Parameter | Value/Configuration |

|---|---|---|

| General | Input Resolution | 640 × 640 |

| Batch Size | 32 | |

| Epochs | 200 | |

| Workers | 16 | |

| Cache Images | FALSE | |

| Optimizer | Optimizer | AdamW |

| Initial Learning Rate (lr0) | 0.002 | |

| Momentum | 0.9 | |

| Weight Decay | 0.0005 | |

| Scheduler | Linear Warm-up (warmup_epochs = 3.0) | |

| Augmentation (Standard) | HSV-H/S/V | 0.015/0.7/0.4 |

| Translate/Scale | 0.1/0.5 | |

| Flip (Left-Right) | 0.5 | |

| Mixup/Mosaic | 0.0/1.0 | |

| Copy-Paste | 0 | |

| Inference | Conf | 0.25 |

| Iou | 0.7 | |

| Strategy | Mixup/Mosaic | 0/0 (Closed to align with real-world data distribution) |

| Copy-Paste | 0.1 (Retained for density maintenance) | |

| Conf | 0.3 (Calibrated for sensitivity) |

| Exp. ID | Backbone Head | Upsampling | Fusion Neck | Down Sampling Conv | Loss Function | Post-Processing | P | R | mAP50 (%) | mAP50-95 (%) | Params (M) | FLOPs (G) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | C2f | Upsample | FPN + PAN | Conv | CIoU | NMS | 0.892 | 0.852 | 90.8 | 65.7 | 11.13 | 28.6 |

| 2 | C2f_EMA | Upsample | FPN + PAN | Conv | WIoU | NMS | 0.905 | 0.859 | 91.7 | 65.1 | 11.19 | 29.5 |

| 3 | C2f_EMA | Upsample | FPN + PAN | ODConv2d | CIoU | NMS | 0.883 | 0.856 | 91.0 | 65.0 | 13.39 | 27.7 |

| 4 | C2f | Upsample | FPN + PAN | Conv | CIoU | Soft-NMS | 0.901 | 0.846 | 90.5 | 68.6 | 11.14 | 28.6 |

| 5 | C2f_EMA | DySample | FPN + PAN | Conv | WIoU | NMS | 0.899 | 0.857 | 91.5 | 65.8 | 11.21 | 29.5 |

| 6 | C2f_EMA | DySample | FPN + PAN | ODConv2d | WIoU | NMS | 0.916 | 0.856 | 91.7 | 65.6 | 13.42 | 29.5 |

| 7 | C2f_EMA | Upsample | FPN + PAN | Conv | WIoU | Soft-NMS | 0.912 | 0.856 | 91.5 | 68.1 | 11.19 | 29.5 |

| 8 | C2f | Upsample | FPN + PAN | ODConv2d | CIoU | Soft-NMS | 0.878 | 0.858 | 90.3 | 68.3 | 13.39 | 27.7 |

| 9 | C2f_EMA | DySample | FPN + PAN | ODConv2d | WIoU | Soft-NMS | 0.882 | 0.863 | 90.7 | 67.4 | 13.42 | 29.5 |

| 10 | C2f | DySample | FPN + PAN | ODConv2d | WIoU | Soft-NMS | 0.883 | 0.866 | 91.0 | 68.3 | 13.45 | 28.6 |

| 11 | C2f_EMA | Upsample | FPN + BiFPN_Concat2 | ODConv2d | WIoU | Soft-NMS | 0.903 | 0.850 | 91.0 | 67.9 | 13.42 | 28.5 |

| 12 | C2f_EMA | Upsample | BiFPN_Concat2 | ODConv2d | WIoU | Soft-NMS | 0.890 | 0.862 | 91.2 | 67.9 | 13.42 | 28.5 |

| 13 | C2f | DySample | FPN + BiFPN_Concat2 | ODConv2d | WIoU | Soft-NMS | 0.900 | 0.855 | 91.0 | 68.5 | 13.45 | 28.6 |

| 14 | C2f_EMA | DySample | BiFPN_Concat2 | ODConv2d | WIoU | Soft-NMS | 0.908 | 0.859 | 90.8 | 68.8 | 13.45 | 28.6 |

| 15 | C2f_EMA | DySample | FPN + BiFPN_Concat2 | Conv | WIoU | NMS | 0.907 | 0.839 | 90.3 | 64.9 | 11.21 | 29.5 |

| 16 | C2f_EMA | DySample | BiFPN_Concat2 | Conv | CIoU | NMS | 0.900 | 0.842 | 91.1 | 65.4 | 11.21 | 29.5 |

| 17 | C2f_EMA | DySample | BiFPN_Concat2 | ODConv2d | CIoU | NMS | 0.894 | 0.851 | 90.9 | 65.2 | 13.45 | 28.6 |

| 18 | C2f_EMA | DySample | BiFPN_Concat2 | ODConv2d | WIoU | NMS | 0.899 | 0.855 | 91.2 | 65.2 | 13.45 | 28.6 |

| 19 | C2f_EMA | DySample | BiFPN_Concat2 | ODConv2d | CIoU | Soft-NMS | 0.880 | 0.861 | 90.6 | 68.6 | 13.45 | 28.6 |

| 20 | C2f_EMA | DySample | BiFPN_Concat2 | ODConv2d | WIoU | Soft-NMS | 0.909 | 0.880 | 92.1 | 69.7 | 13.44 | 28.4 |

| Logical Block | Experiment Parameters (default: iou = 0.7; mixup = 0) | mAP50 (%) | mAP50-95 (%) | P | R |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block A | conf = 0.25; copy_paste = 0; mosaic = 1 | 0.907 | 0.682 | 0.899 | 0.858 |

| conf = 0.25; copy_paste = 0; mosaic = 0 | 0.914 | 0.691 | 0.899 | 0.881 | |

| conf = 0.25; copy_paste = 0.1; mosaic = 1 | 0.908 | 0.684 | 0.905 | 0.853 | |

| conf = 0.25; copy_paste = 0.1; mosaic = 0 | 0.918 | 0.701 | 0.905 | 0.88 | |

| Block B | conf = 0.3; copy_paste = 0; mosaic = 1 | 0.906 | 0.682 | 0.891 | 0.858 |

| conf = 0.3; copy_paste = 0; mosaic = 0 | 0.91 | 0.688 | 0.921 | 0.857 | |

| conf = 0.3; copy_paste = 0.1; mosaic = 1 | 0.907 | 0.679 | 0.893 | 0.861 | |

| conf = 0.3; copy_paste = 0.1; mosaic = 0 | 0.921 | 0.697 | 0.909 | 0.88 |

| Model ID | Parameters (M) | GFLOPS | Inference Time (ms) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | mAP50 (%) | mAP50-95 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv5s | 9.11 | 23.8 | 4.1 | 88.9 | 84.1 | 90.8 | 64.9 |

| YOLOv8s | 11.14 | 28.6 | 2.7 | 89.2 | 85.2 | 90.8 | 65.7 |

| YOLOv9s | 7.17 | 26.7 | 1.4 | 88.2 | 84.8 | 90.5 | 64.4 |

| YOLOv10s | 7.22 | 21.4 | 1.2 | 88.2 | 82.8 | 89.2 | 64.2 |

| YOLOv11s | 9.41 | 21.3 | 1.2 | 88.6 | 84.1 | 90.6 | 65.7 |

| YOLOv12s | 9.23 | 21.2 | 1.8 | 87.8 | 84.0 | 90.3 | 64.1 |

| YOLOv13s | 9.53 | 21.3 | 3.2 | 89.3 | 85.9 | 91.2 | 65.1 |

| RT-DETR-L | 32.87 | 108 | 3.3 | 90.8 | 86.4 | 92.1 | 67.6 |

| MDB-YOLO | 13.44 | 28.4 | 1.1 | 90.9 | 88.0 | 92.1 | 69.7 |

| Model ID | Parameters (M) | GFLOPS | mAP50 (%) | mAP50-95 (%) | mAR50 (%) | mAR50-95 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT-DETRv4-S | 10.00 | 25.0 | 90.8 | 65.5 | 96.1 | 72.2 |

| D-FINE-S | 10.00 | 25.0 | 92.0 | 67.8 | 96.7 | 74.6 |

| MDB-YOLO (in standard pycocotools library) | 13.44 | 28.4 | 85.3 | 61.3 | 87.7 | 66.7 |

| MDB-YOLO (in YOLO internal validation tool) | 13.44 | 28.4 | 92.1 | 69.7 | N/A | N/A |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yu, L.; Feng, X.; Zeng, Y.; Guo, W.; Yang, X.; Zhang, X.; Tan, Y.; Sun, C.; Lu, X.; Sun, H. MDB-YOLO: A Lightweight, Multi-Dimensional Bionic YOLO for Real-Time Detection of Incomplete Taro Peeling. Electronics 2026, 15, 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010097

Yu L, Feng X, Zeng Y, Guo W, Yang X, Zhang X, Tan Y, Sun C, Lu X, Sun H. MDB-YOLO: A Lightweight, Multi-Dimensional Bionic YOLO for Real-Time Detection of Incomplete Taro Peeling. Electronics. 2026; 15(1):97. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010097

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Liang, Xingcan Feng, Yuze Zeng, Weili Guo, Xingda Yang, Xiaochen Zhang, Yong Tan, Changjiang Sun, Xiaoping Lu, and Hengyi Sun. 2026. "MDB-YOLO: A Lightweight, Multi-Dimensional Bionic YOLO for Real-Time Detection of Incomplete Taro Peeling" Electronics 15, no. 1: 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010097

APA StyleYu, L., Feng, X., Zeng, Y., Guo, W., Yang, X., Zhang, X., Tan, Y., Sun, C., Lu, X., & Sun, H. (2026). MDB-YOLO: A Lightweight, Multi-Dimensional Bionic YOLO for Real-Time Detection of Incomplete Taro Peeling. Electronics, 15(1), 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010097