The Impact of Self-Heating on Single-Event Transient Effect in Triple-Layer Stacked Nanosheets: A TCAD Simulation

Abstract

1. Introduction

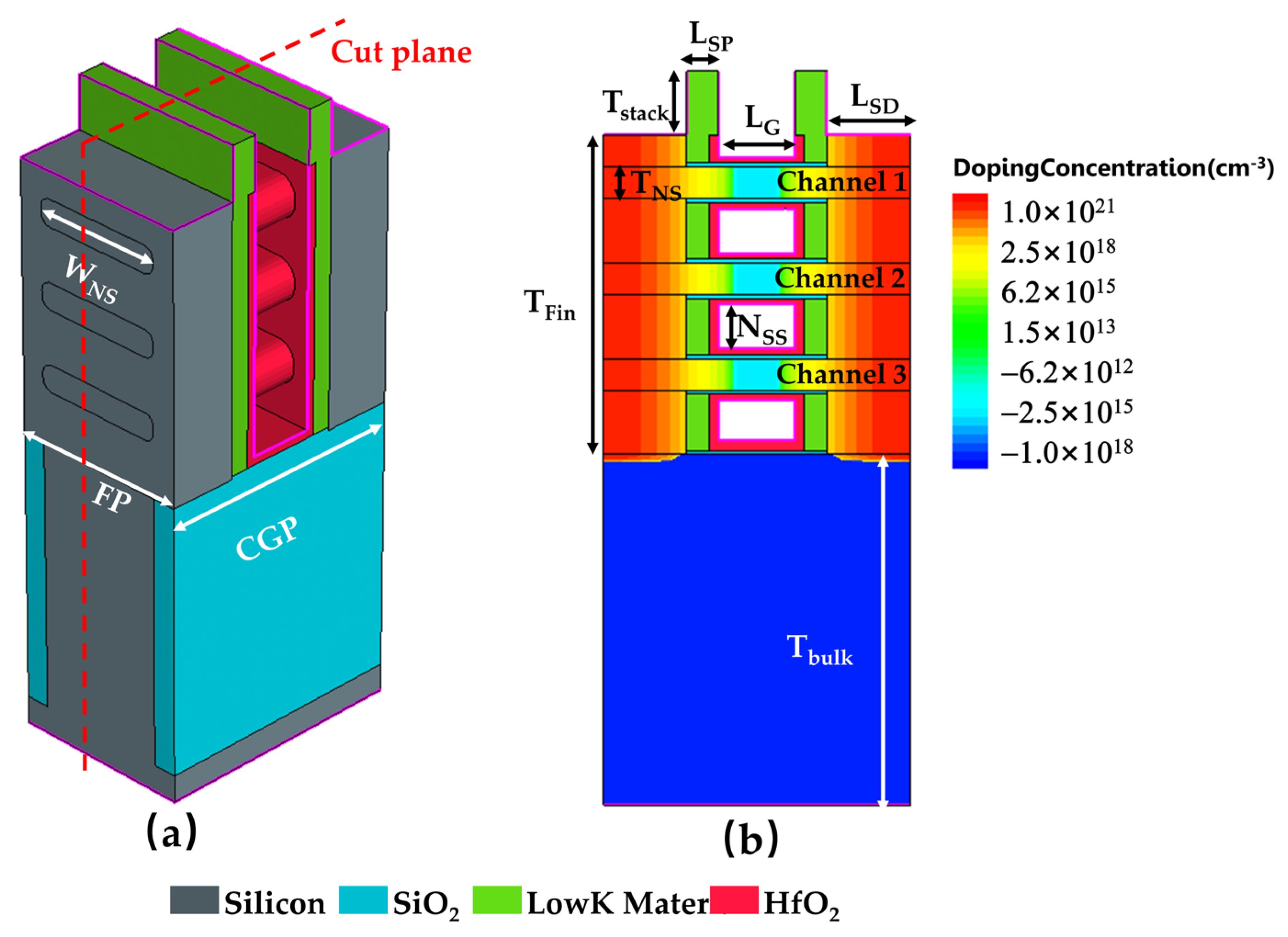

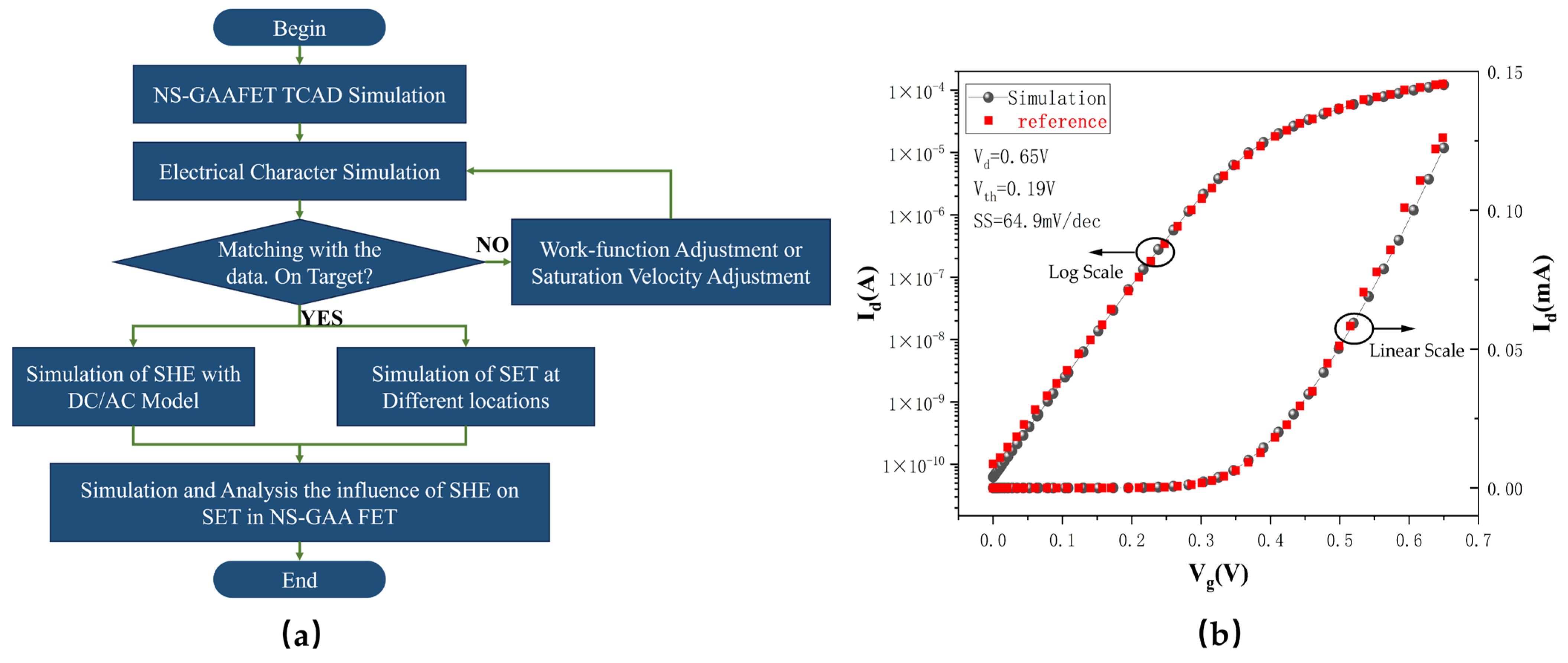

2. Device Structure and Simulation Setup

| Symbol | Description | Value | Symbol | Description | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LG (nm) | Gate Length [19] | 12 | WK (eV) | Gate Work Function | 4.48 |

| LSP (nm) | Spacer Length [19] | 5 | NSD (cm−3) | Source/Drain Doping Concentration [17] | 1 × 1021 |

| LSD (nm) | Source/Drain Length | 5.5 | NChannel (cm−3) | Channel Doping Concentration [17] | 1× 1015 |

| WNS (nm) | Nanosheet Width | 15 | Nbulk (cm−3) | Bulk Doping Concentration [17] | 1× 1018 |

| TNS (nm) | Nanosheet Thickness [19] | 5 | VDD(V) | Supply Voltage | 0.65 |

| EOT (nm) | Effect Oxide Thickness | 2.1 | NSS (nm) | Nanosheet Spacer | 7.7 |

| CGP (nm) | Contact Gate Pitch | 34 | KCh (W/cm·K) | Channel Thermal Conductivity [17] | 0.0807 |

| FP (nm) | Fin Pitch | 24 | KSD (W/cm·K) | Source/Drain Thermal Conductivity [17] | 0.1661 |

| Tstack (nm) | Stack Thickness | 10 | Kbulk (W/cm·K) | Bulk Thermal Conductivity [17] | 1.48 |

| Tbulk (nm) | Bulk Thickness | 55 | Koxide (W/cm·K) | Oxide Conductivity | 0.14 |

| TFin (nm) | Fin Thickness | 50 | Roxide/si (W/cm−2·K) | Distributed Interface Thermal Resistance | 2 × 10−4 |

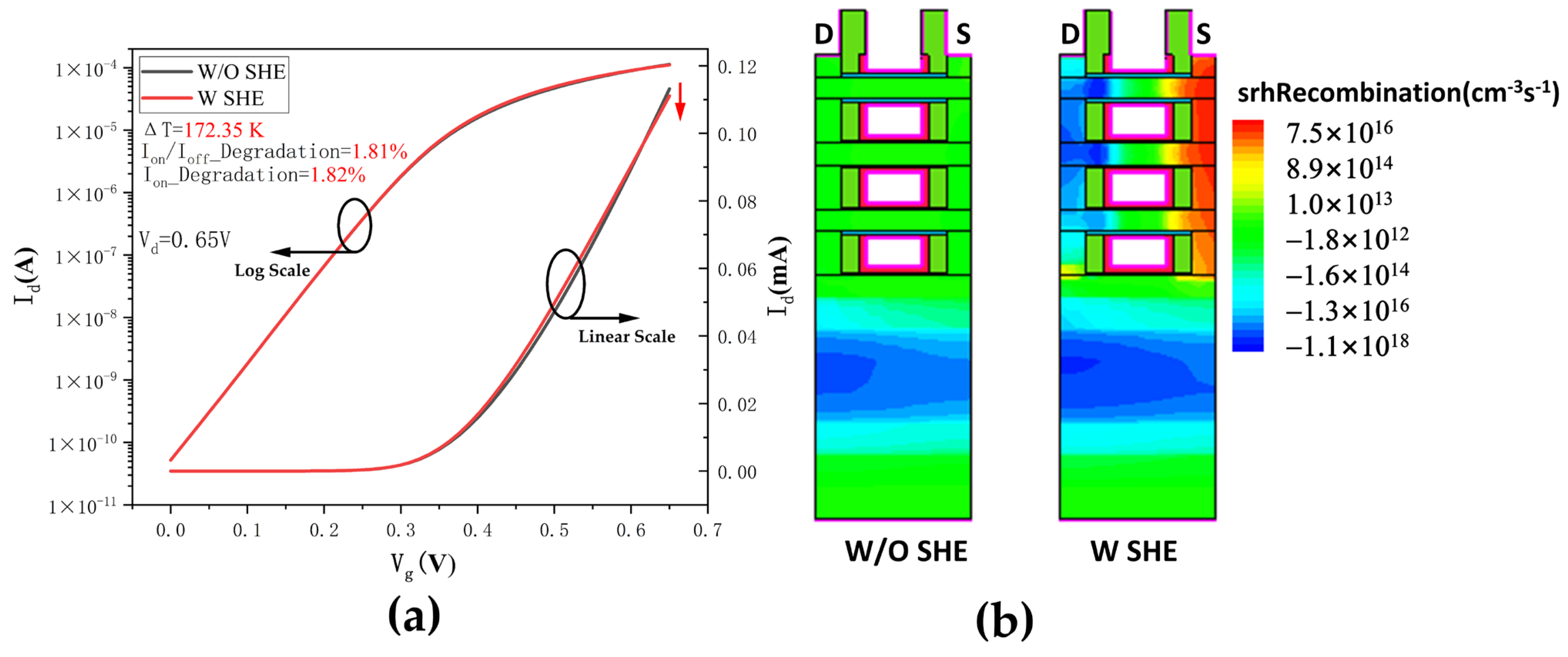

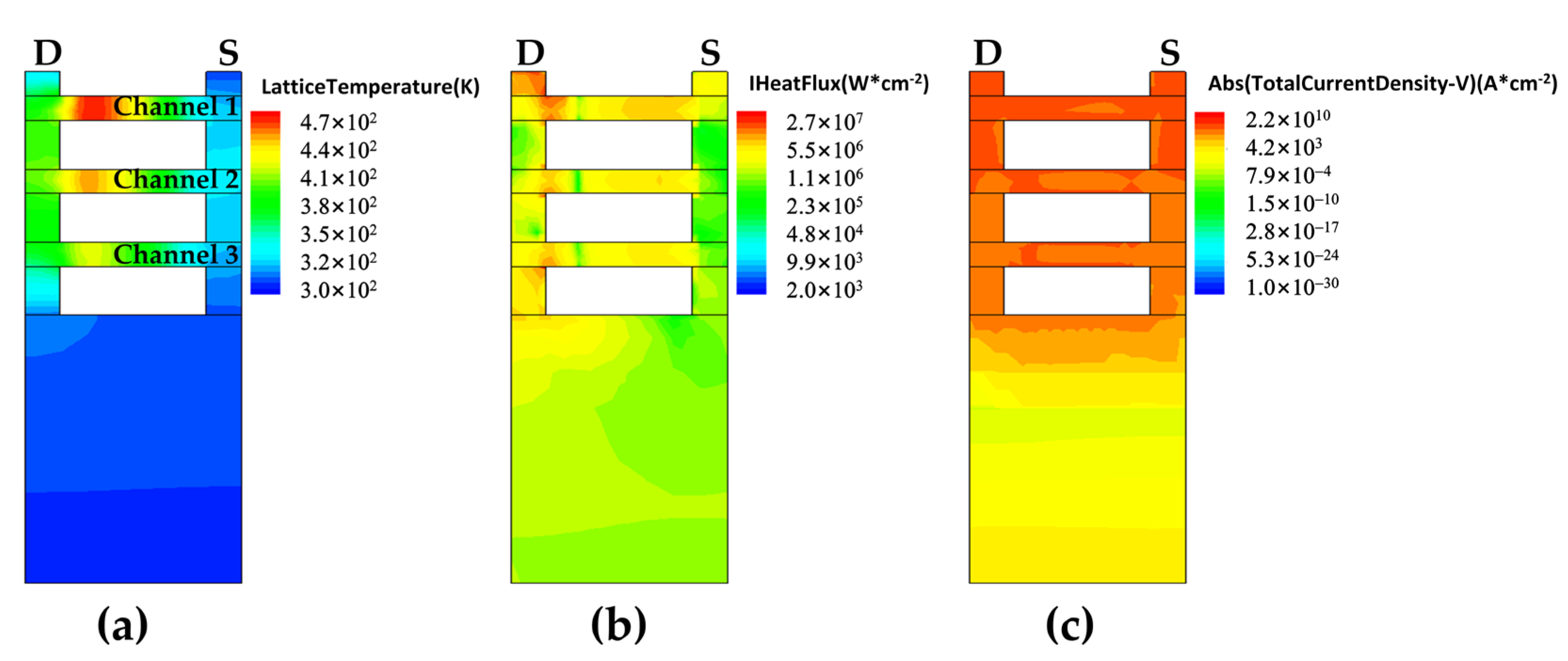

3. Results and Discussion

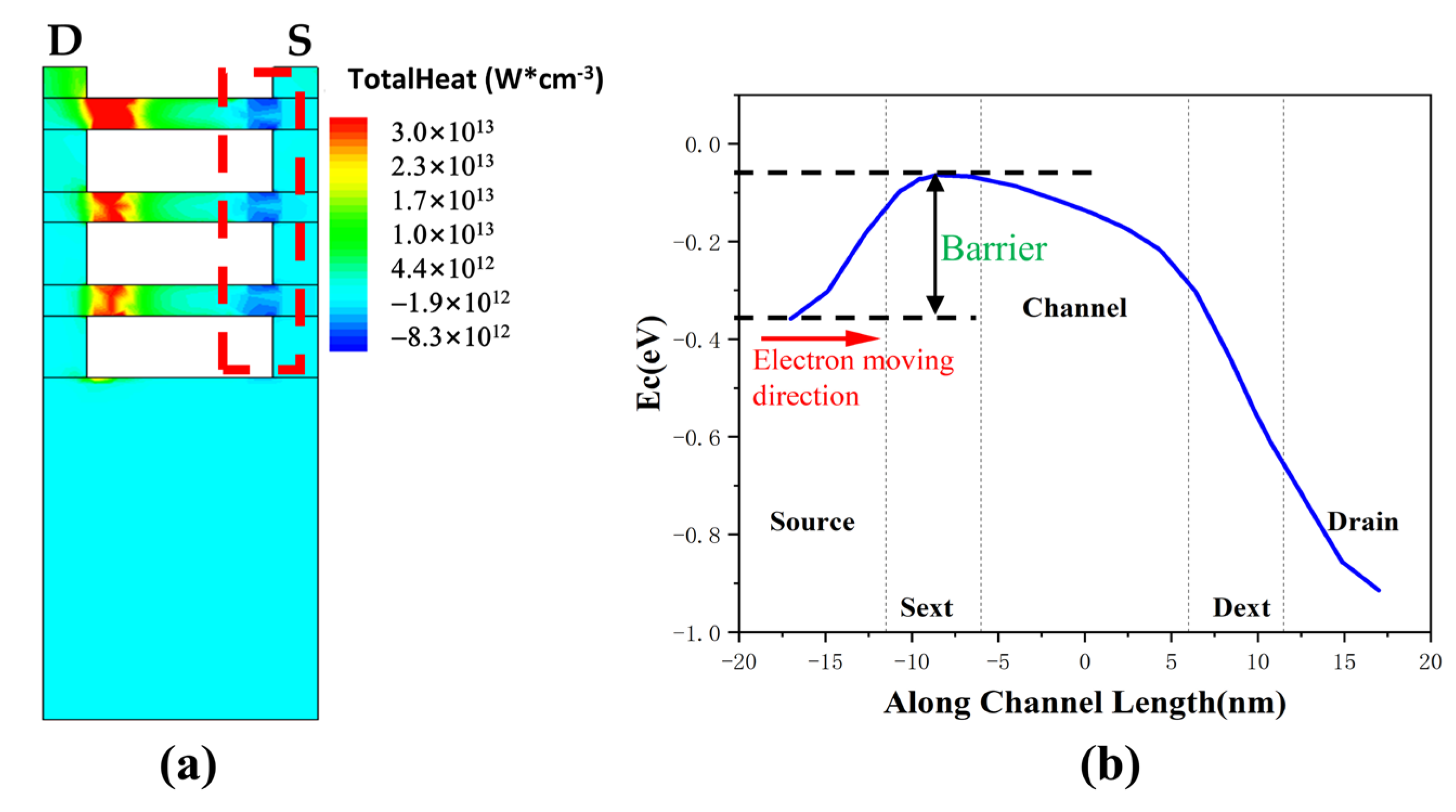

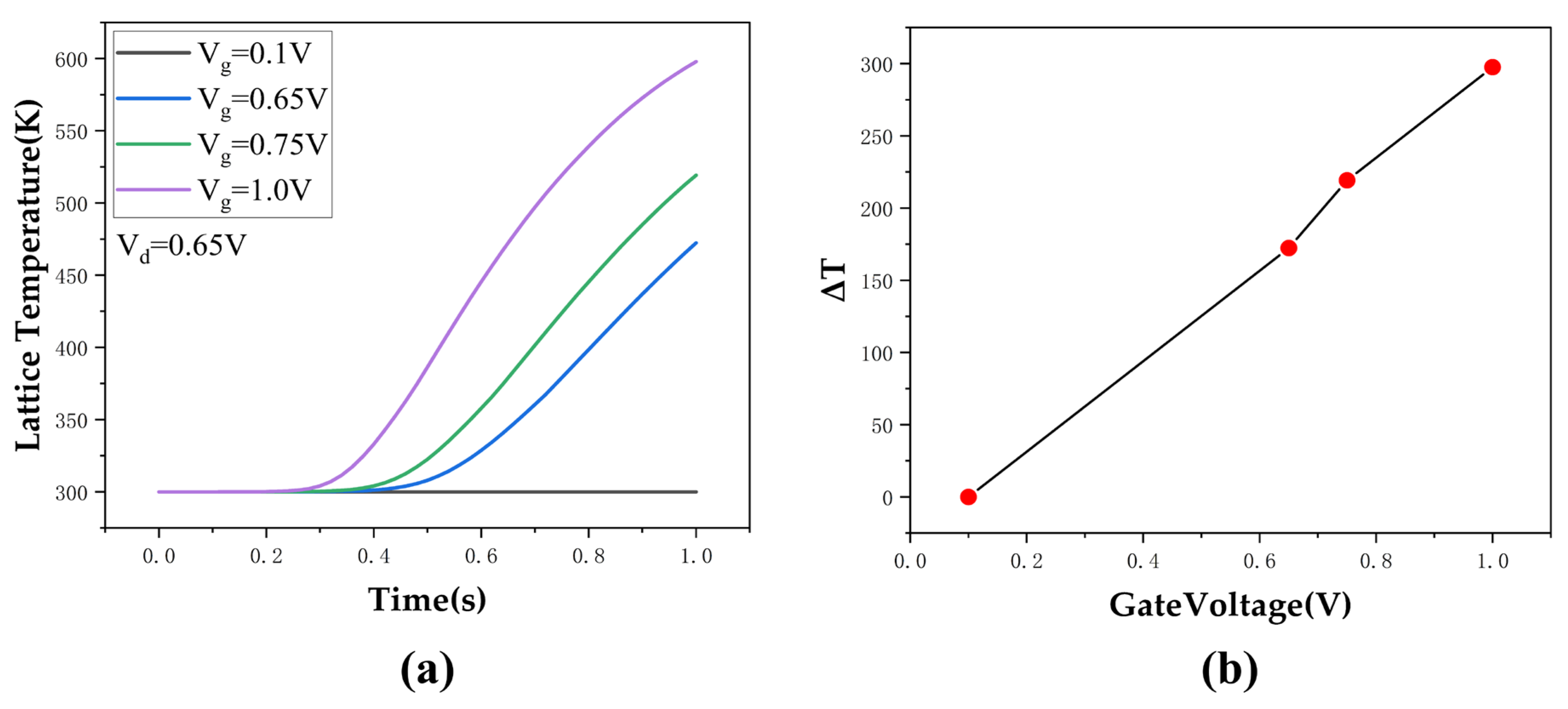

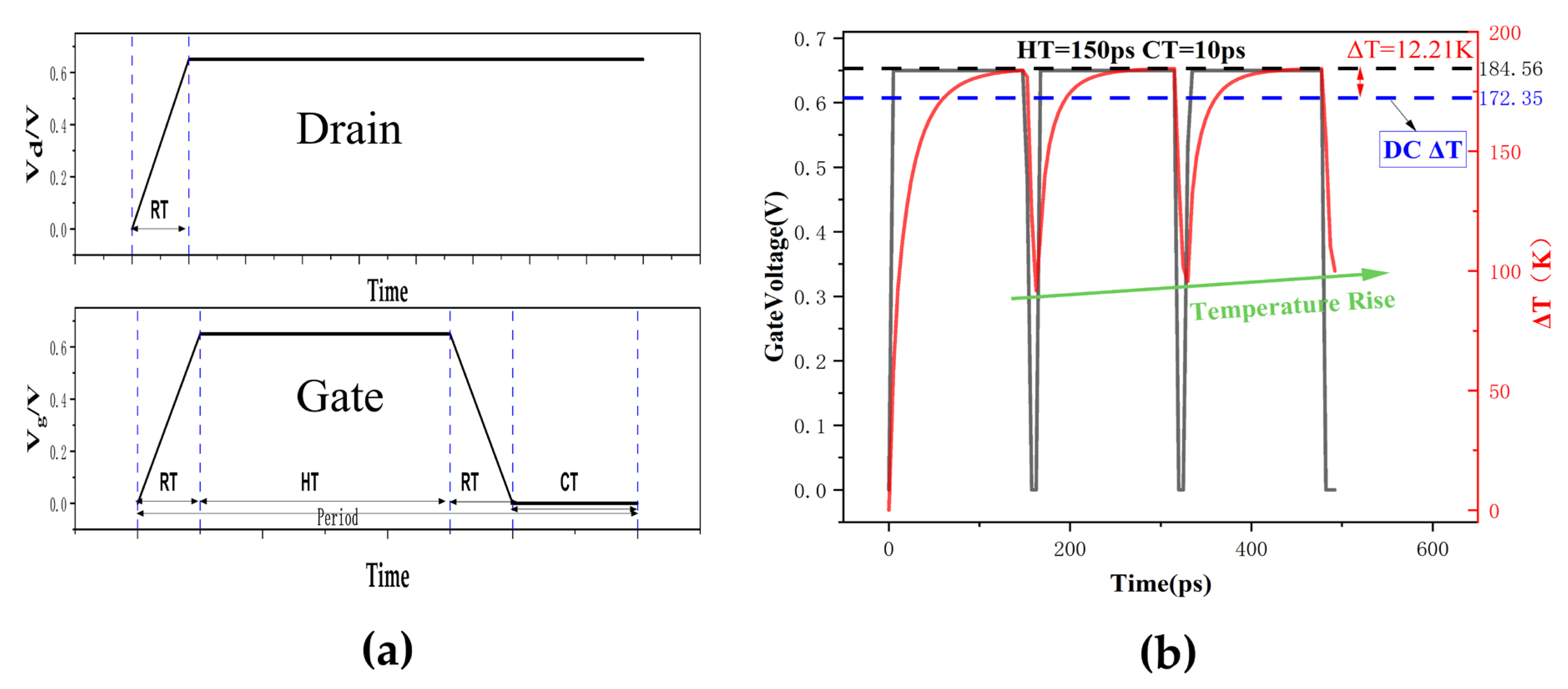

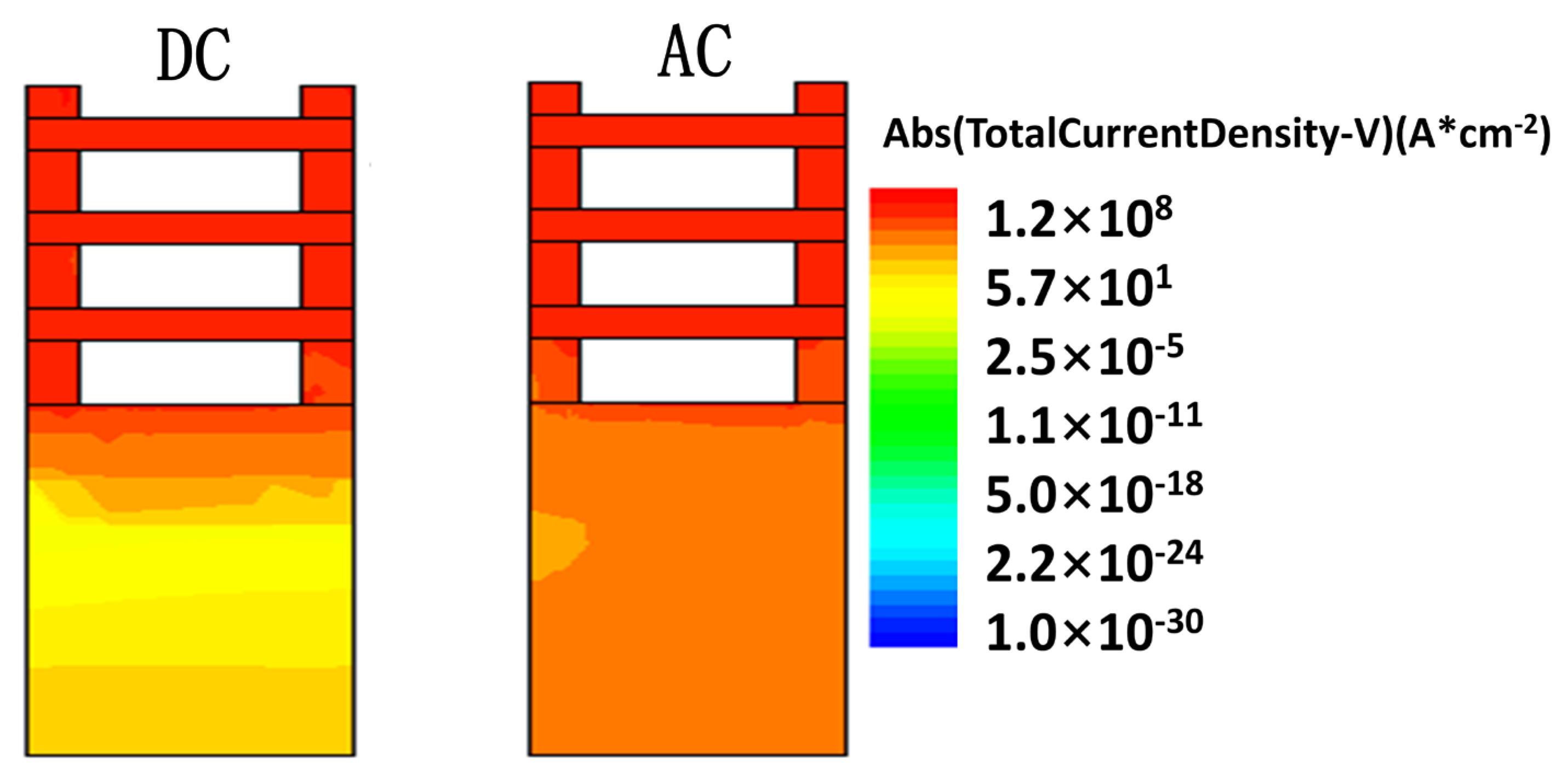

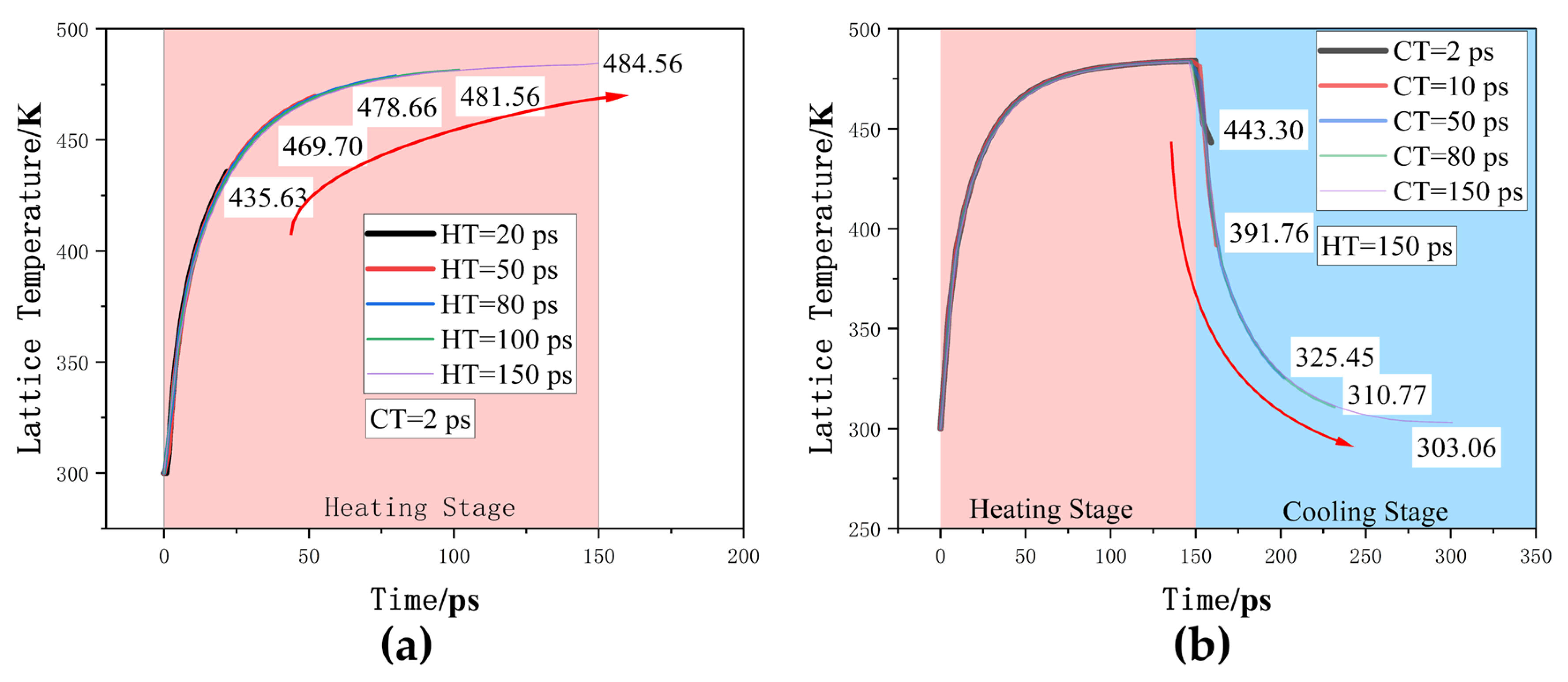

3.1. DC/AC Characteristic of SHE in Triple-Layer Stacked Nanosheets

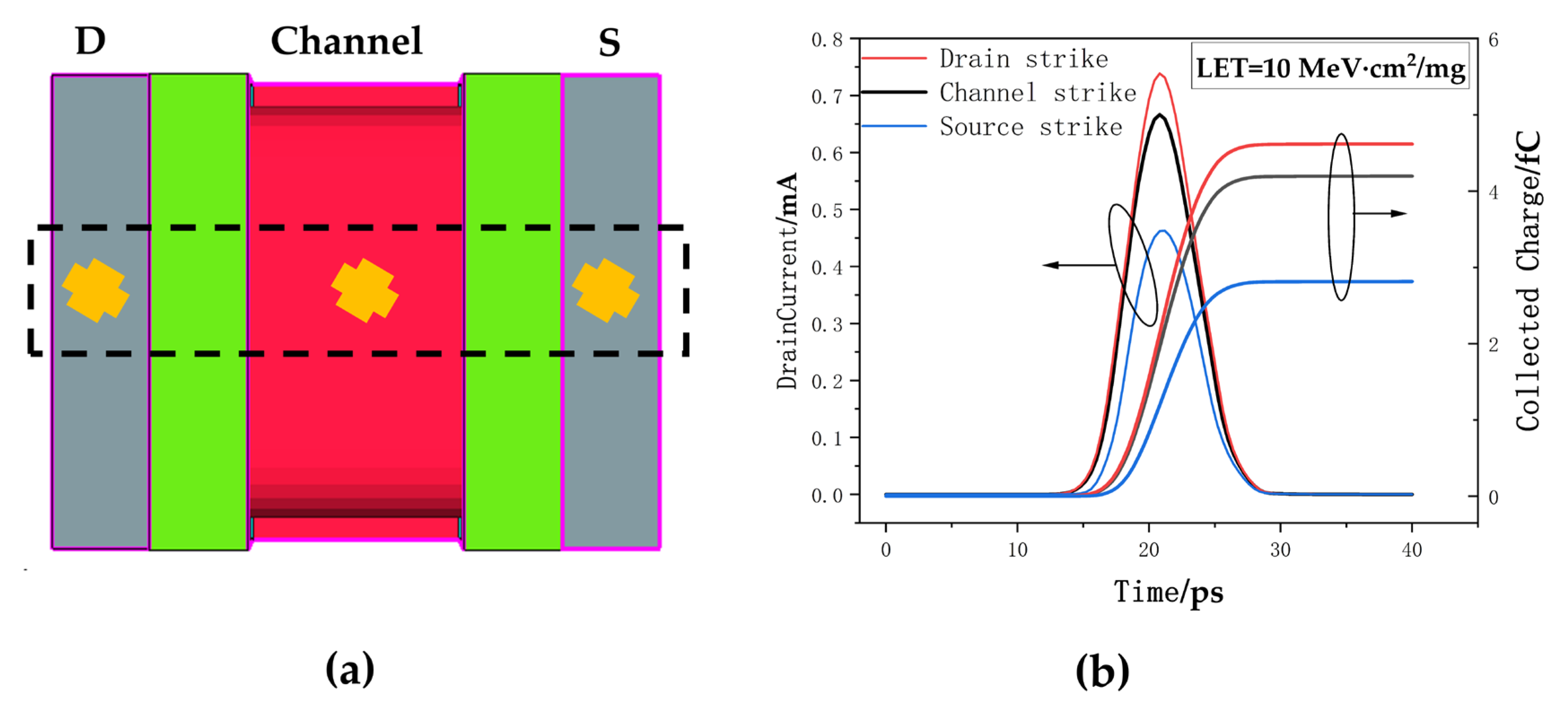

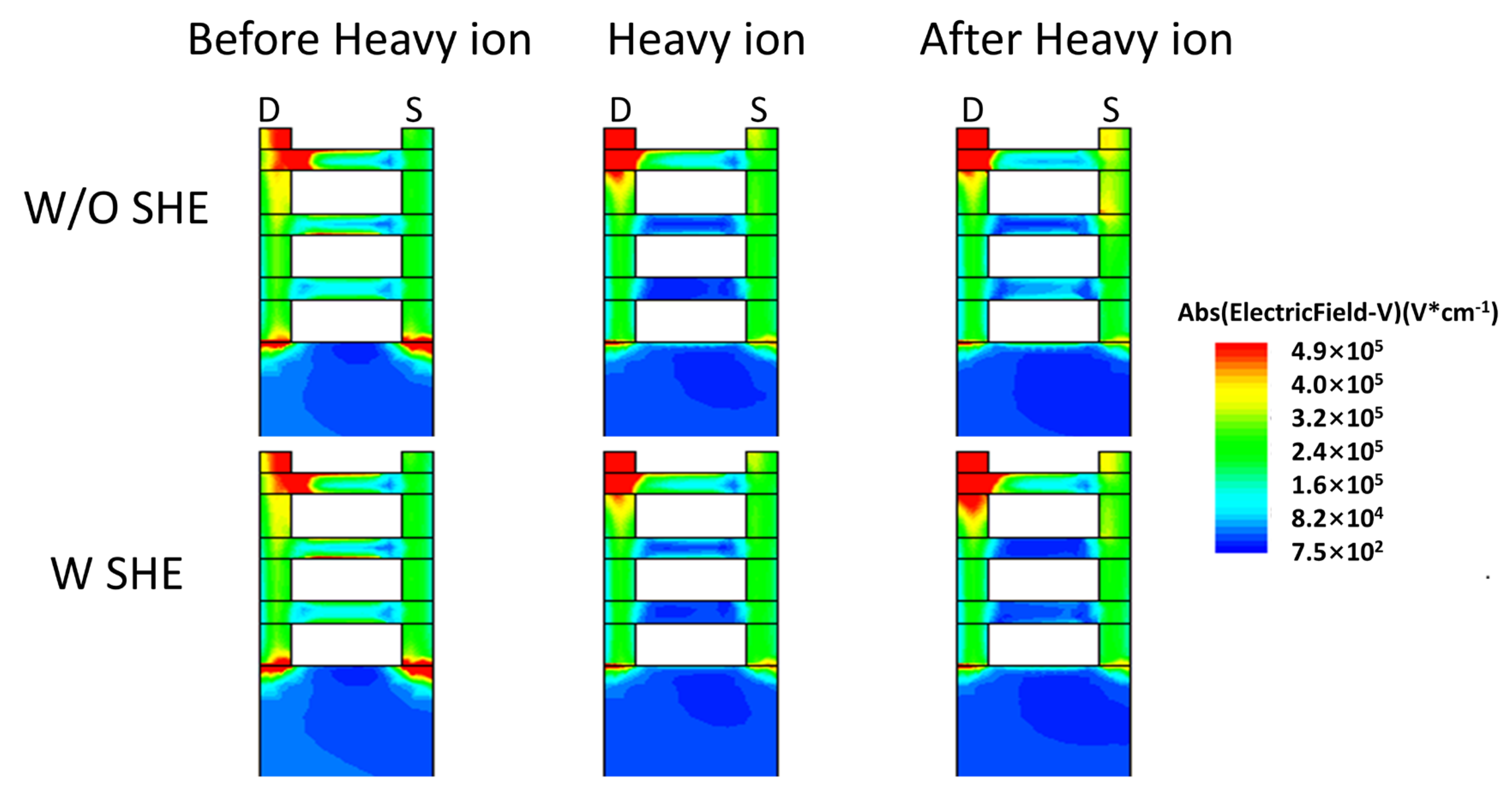

3.2. The Single-Event Transient Effect in Triple-Layer Stacked Nanosheets

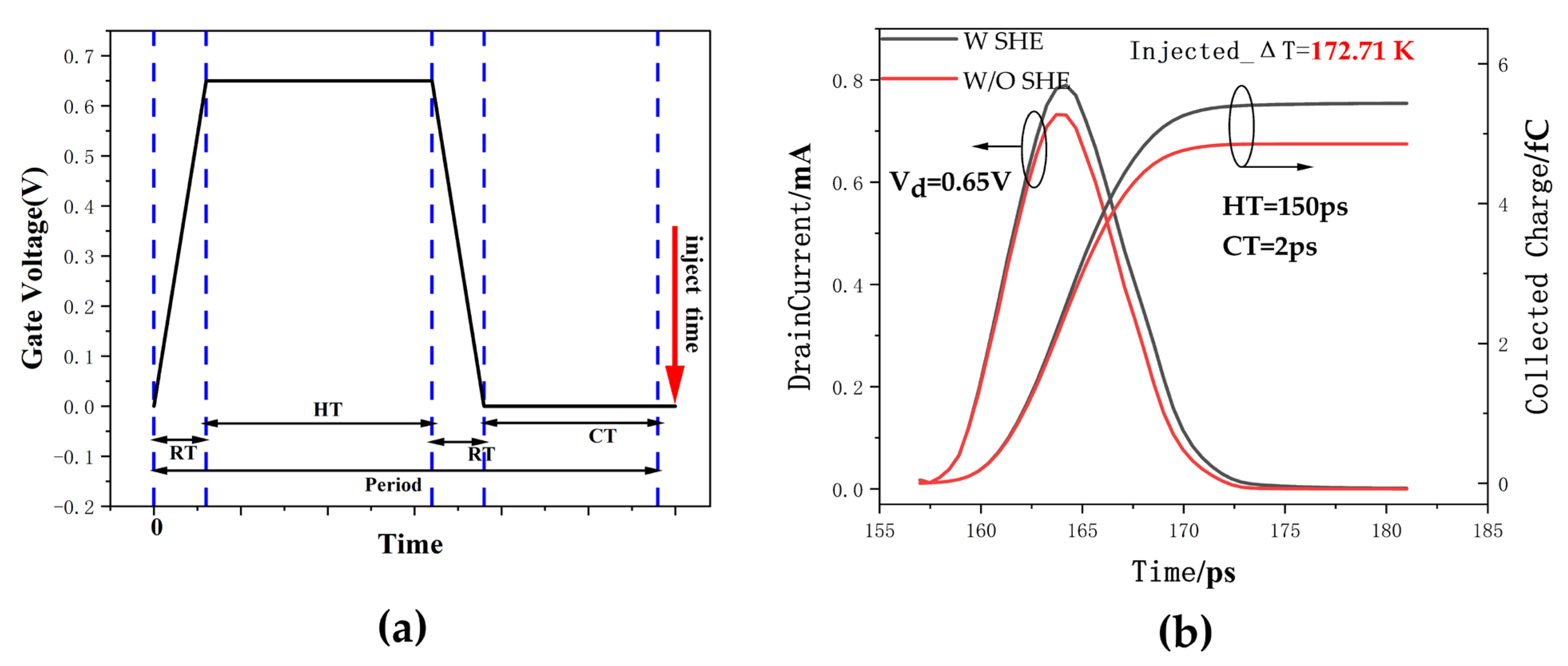

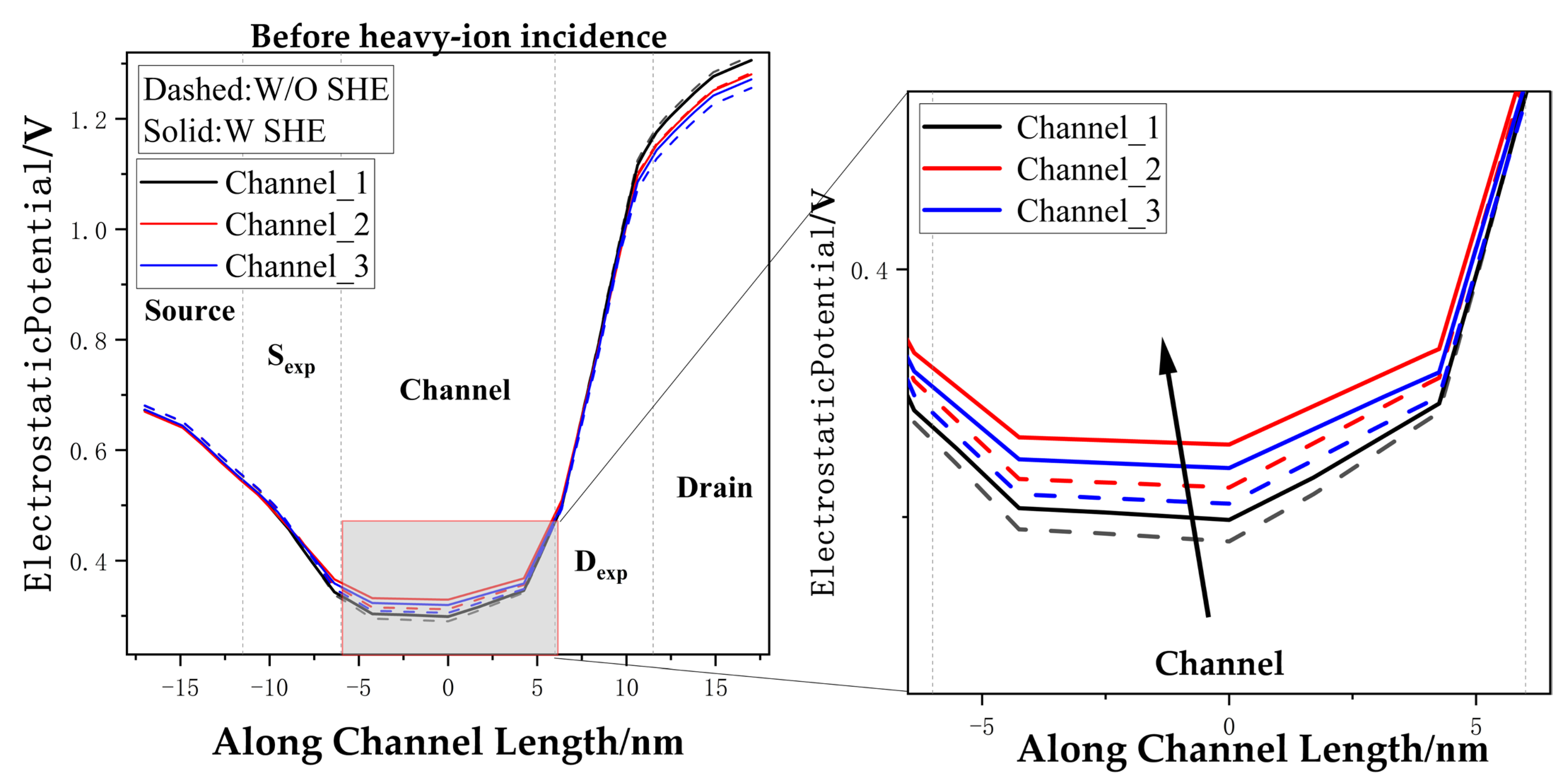

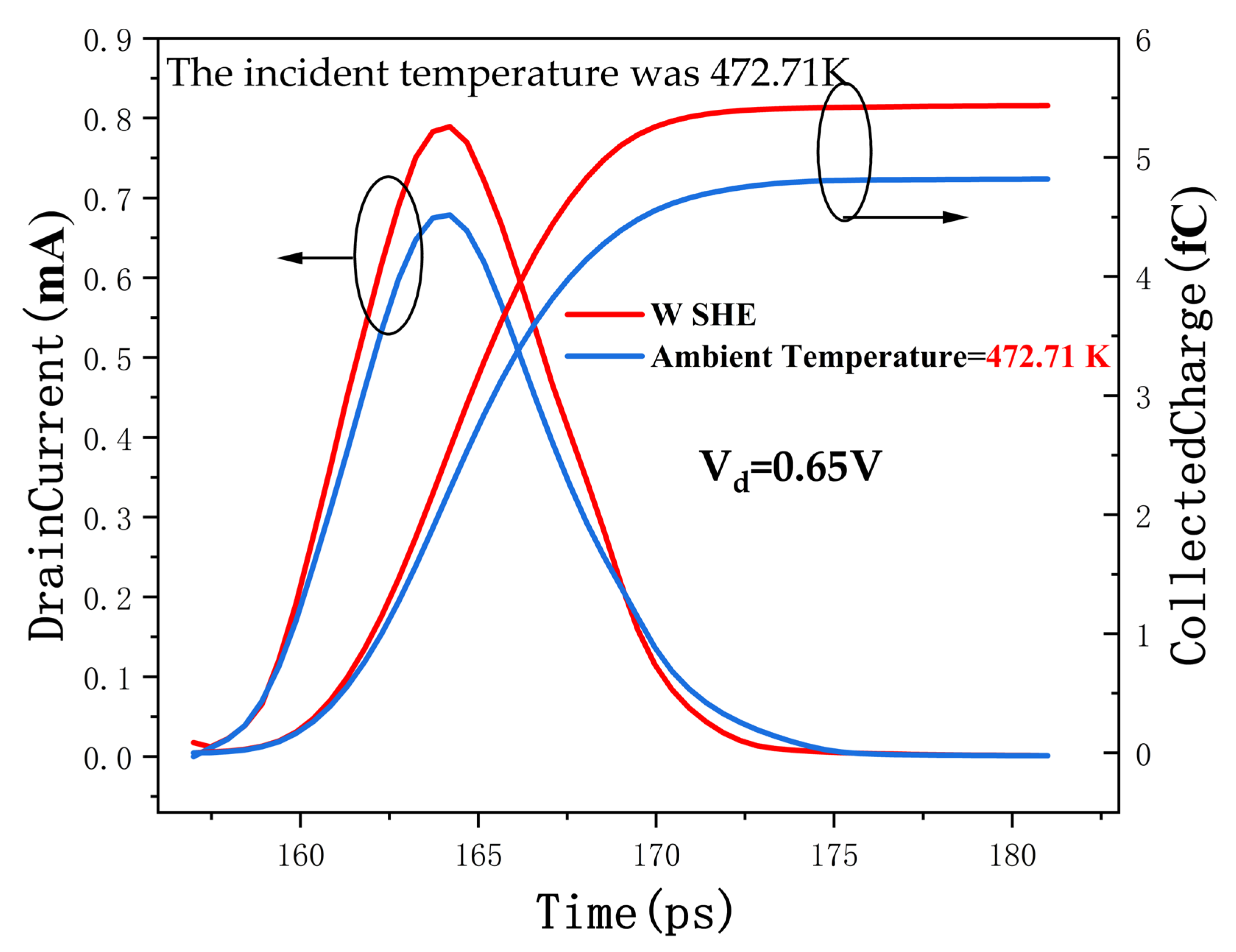

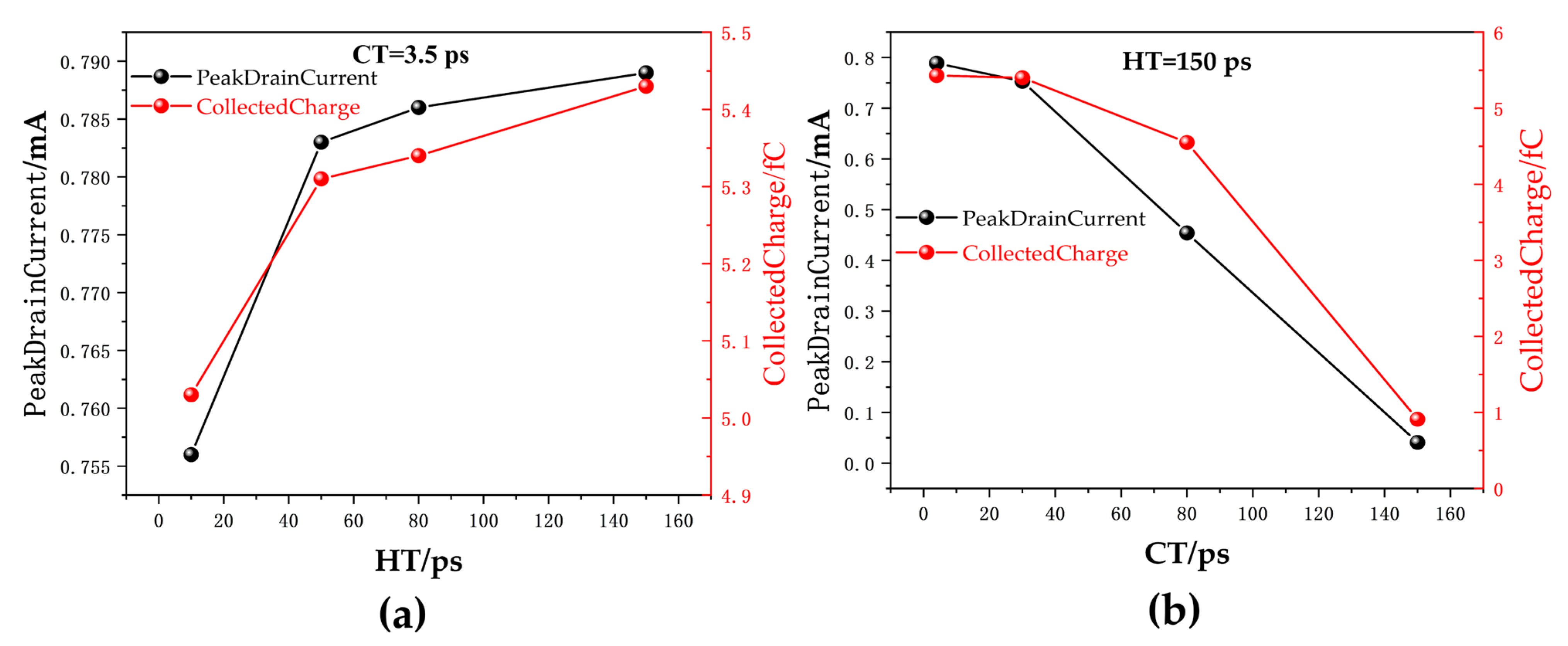

3.3. The Influence of SHE on SET in Triple-Layer Stacked Nanosheets

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sreenivasulu, V.B.; Narendar, V. Characterization and Optimization of Junctionless Gate-All-around Vertically Stacked Nanowire FETs for Sub-5 Nm Technology Nodes. Microelectron. J. 2021, 116, 105214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Gu, J.; Xu, R.; Cao, L.; Li, J.; Wu, Z.; Wang, G.; Yao, J.; Zhang, Z.; Xiang, J.; et al. Optimization of Structure and Electrical Characteristics for Four-Layer Verti-cally-Stacked Horizontal Gate-All-Around Si Nanosheets Devices. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 646. [Google Scholar]

- Gaddemane, G.; Schuddinck, P.; Bhuwalka, K.; Rzepa, G.; Mirabelli, G.; Gupta, A.; Bömmels, J.; Matagne, P.; Yakimets, D.; Wu, H.; et al. Exploring GAA-Nanosheet, Forksheet and GAA–Forksheet Architectures: A TCAD-DTCO Study at 90 Nm and 120-Nm Cell Height. IEEE J. Electron Devices Soc. 2025, 13, 769–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, G.; Rathod, S.S.; Maheshwaram, S.; Manhas, S.K.; Saxena, A.K.; Dasgupta, S. Radiation Effects in Si-NW GAA FET and CMOS Inverter: A TCAD Simulation Study. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2012, 59, 1563–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalia, G.; Hegde, R.S. Study of Self-Heating Effects in Silicon Nano-Sheet Transistors. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Electron Devices and Solid State Circuits (EDSSC), Shenzhen, China, 6–8 June 2018; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, Y.; Lin, X.; Li, J.; Cheng, R.; Yu, X.; Zheng, Z.; Lu, J.; Chen, B.; Zhao, Y. Ultra fast (<1 ns) electrical characterization of self-heating effect and its impact on hot carrier injection in 14nm FinFETs. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM), San Francisco, CA, USA, 2–6 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, S.H.; Masuduzzaman, M.; Wahab, M.A.; Maize, K.; Gu, J.J.; Si, M.; Shakouri, A.; Ye, P.D.; Alam, M.A. Direct Observa-tion of Self-Heating in III–V Gate-All-Around Nanowire MOSFETs. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM), San Francisco, CA, USA, 15–17 December 2014; pp. 20.3.1–20.3.4. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, M.-C.; On, N.; Ji, H.; Nguyen, A.H.-T.; Choi, S.; Cheon, J.; Yu, K.-M.; Cho, S.-Y.; Kim, J.; Kim, S.; et al. Electrical Characterization of the Self-Heating Effect in Oxide Semiconductor Thin-Film Transistors Using Pulse-Based Measurements. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2018, 65, 2492–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubbareddy, M.; Sivasankaran, K.; Atamuratov, A.E.; Khalilloev, M.M. Optimization of Vertically Stacked Nanosheet FET Immune to Self-Heating. Micro Nano Struct. 2023, 182, 207633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Chen, W.; Du, G.; Kang, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X. Investigation of Self-Heating Effect on Stacked Nanosheet GAA Transistors. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Symposium on VLSI Technology, Systems and Application (VLSI-TSA), Hsinchu, Taiwan, 16–19 April 2018; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Bi, J.; Majumdar, S.; Mehmood, S.; Ji, L.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, C.; Fan, L.; Zhao, B.; Wang, H.; et al. The Influ-ences of Radiation Effects on DC/RF Performances of L g = 22 Nm Gate-All-around Nanosheet Field-Effect Transistor. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 2022, 37, 035010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bheemudu, V.; Vaithiyanathan, D.; Kaur, B. A Reliability Assessment of Junctionless (JL) Nanosheet (NS) FET under Heavy Ion Irradiation Conditions. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 20th India Council International Conference (INDICON), Telangana, India, 14–17 December 2023; pp. 1380–1385. [Google Scholar]

- Gaillardin, M.; Raine, M.; Martinez, M.; Duhamel, O.; Riffaud, J.; Lagutere, T.; Marcandella, C.; Paillet, P.; Richard, N.; Vinet, M.; et al. Analysis of Nanowire Field-Effect Transistors SET Response: Geometrical Considerations. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2019, 66, 1410–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Aierken, A.; Liu, X.; Liu, M.; Gao, C.; Wang, G.; Wang, D.; Majumdar, S.; Xuan, Y.; Liu, M.; et al. Heavy Ions Induced Single-Event Transient in SiGe-on-SOI HBT by TCAD Simulation. Micromachines 2025, 16, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekoya, M.A.; Liu, S.; Wang, X.; Xing, T.; Li, H.; Meng, F.; Du, X.; Li, Z.; Huang, T. Simulation and analysis of inverse-mode operation of single event transient mechanisms on NPN-SiGe HBT. Phys. Scr. 2024, 99, 055309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhao, Q.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Fan, J.; Hao, J.; Zhang, F.; Dong, Z. Study of electrical and thermal performance in single-event burnout of partial-SOI LDMOS transistors. Microelectron. Reliab. 2025, 169, 115736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Li, X.; Sun, Y.; Shi, Y. A Vertical Combo Spacer to Optimize Electrothermal Characteristics of 7-Nm Nanosheet Gate-All-Around Transistor. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2020, 67, 2249–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-C.; Jhan, Y.-R. 3D TCAD Simulation for CMOS Nanoeletronic Devices; Springer: Singapore, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Loubet, N.; Hook, T.; Montanini, P.; Yeung, C.-W.; Kanakasabapathy, S.; Guillom, M.; Yamashita, T.; Zhang, J.; Miao, X.; Wang, J.; et al. Stacked nanosheet gate-all-around transistor to enable scaling beyond FinFET. In Proceedings of the 2017 Symposium on VLSI Technology, Kyoto, Japan, 5–8 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Synop. Inc. Sentaurus Device User Guide. [Online]. 2015. Available online: https://kolegite.com/EE_library/books_and_lectures/%D0%90%D0%B2%D1%82%D0%BE%D0%BC%D0%B0%D1%82%D0%B8%D0%B7%D0%B0%D1%86%D0%B8%D1%8F%20%D0%BD%D0%B0%20%D0%9F%D1%80%D0%BE%D0%B5%D0%BA%D1%82%D0%B8%D1%80%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%B5%D1%82%D0%BE%20%D0%B2%20%D0%95%D0%BB%D0%B5%D0%BA%D1%82%D1%80%D0%BE%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%BA%D0%B0%D1%82%D0%B0/Sentaurus_Training/sd/sd_menu.html (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Kang, M.J.; Myeong, I.; Kang, M.; Shin, H. Analysis of DC Self Heating Effect in Stacked Nanosheet Gate-All-Around Tran-sistor. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 2nd Electron Devices Technology and Manufacturing Conference (EDTM), Kobe, Japan, 13–16 March 2018; pp. 343–345. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Liu, H.; Chen, S.; Wang, S.; Chong, C.; Liu, C. Performance Analysis and Optimization of an InGaAs/GaAsSb Heterojunction Dopingless Tunnel FET with a Heterogate Dielectric. Micromachines 2025, 16, 1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Boumaiza, S.; Wei, L. Self-Heating in Short-Channel GaN HEMTs: Maximum Channel Temperature and Equiva-lent Channel Temperature. In Proceedings of the 2022 6th IEEE Electron Devices Technology & Manufacturing Conference (EDTM), Oita, Japan, 6–9 March 2022; pp. 351–353. [Google Scholar]

- Pop, E.; Rowlette, J.A.; Dutton, R.W.; Goodson, K.E. Joule Heating under Quasi-Ballistic Transport Conditions in Bulk and Strained Silicon Devices. In Proceedings of the 2005 International Conference on Simulation of Semiconductor Processes and Devices, Tokyo, Japan, 1–3 September 2005; pp. 307–310. [Google Scholar]

- Myeong, I.; Son, D.; Kim, H.; Shin, H. Analysis of Self Heating Effect in DC/AC Mode in Multi-Channel GAA-Field Effect Transistor. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2019, 66, 4631–4637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Seo, Y.; Myong, I.H.; Kang, M.; Shin, H. Analysis on DC and AC Characteristics of Self Heating Effect in Nanowire. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2017, 17, 3056–3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atamuratov, A.E.; Rajapov, D.R.; Khalilloev, M.M.; Sivasankaran, K.; Balasubbareddy, M.; Yusupov, A. A Comprehensive Study of the Impact of the Gate Oxide Material Composition on the Self-Heating Effect in Nanosheet Field Effect Transistor. Silicon 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Y.; Xia, Y.; Xu, J.; Wang, S.; Ren, P.; Ji, Z.; Bao, H. Multiscale Thermal Simulation for GAAFET with First-Principles-Based Boltzmann Transport Equation. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2025, 72, 4700–4707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aneesh, Y.M.; Sriram, S.R.; Pasupathy, K.R.; Bindu, B. An Analytical Model of Single-Event Transients in Double-Gate MOSFET for Circuit Simulation. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2019, 66, 3710–3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramya, M.; Nagarajan, K.K. Investigation of Single Event Transients on RingFET Using 3D TCAD Simulations. Silicon 2022, 15, 875–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, G.; Xi, K.; Xu, G.; Bi, J.; Yin, H. Analysis of Single Event Effects in Capacitor-Less 1T-DRAM Based on an InGaAs Tran-sistor. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2021, 68, 1604–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajakumar, P.S.; Satheesh Kumar, S. Analysis of Single Event Transient Impact in Si/Si-Ge Gate-All-Around Nanowire FET Using TCAD. Results Eng. 2025, 25, 103930. [Google Scholar]

- Bi, J.-S.; Zeng, C.-B.; Gao, L.-C.; Liu, G.; Luo, J.-J.; Han, Z.-S. Estimation of Pulsed Laser-Induced Single Event Transient in a Partially Depleted Silicon-on-Insulator 0.18-Μm MOSFET. Chin. Phys. B 2014, 23, 088505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, A.; Koley, K.; Kumar, J.; Kumar, P. Investigation of Single-Event-Transient Effects Induced by Heavy-Ion in All-Silicon DG-TFET. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 109357–109365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, Y.; Bi, J.; Liu, X.; Aierken, A.; Liu, M.; Gao, C.; Wang, G.; Wang, D.; Wang, K.; Xuan, Y. The Impact of Self-Heating on Single-Event Transient Effect in Triple-Layer Stacked Nanosheets: A TCAD Simulation. Electronics 2026, 15, 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010085

Li Y, Bi J, Liu X, Aierken A, Liu M, Gao C, Wang G, Wang D, Wang K, Xuan Y. The Impact of Self-Heating on Single-Event Transient Effect in Triple-Layer Stacked Nanosheets: A TCAD Simulation. Electronics. 2026; 15(1):85. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010085

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Yuanda, Jinshun Bi, Xuefei Liu, Abuduwayiti Aierken, Mingqiang Liu, Changsong Gao, Gang Wang, Degui Wang, Kelin Wang, and Yundong Xuan. 2026. "The Impact of Self-Heating on Single-Event Transient Effect in Triple-Layer Stacked Nanosheets: A TCAD Simulation" Electronics 15, no. 1: 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010085

APA StyleLi, Y., Bi, J., Liu, X., Aierken, A., Liu, M., Gao, C., Wang, G., Wang, D., Wang, K., & Xuan, Y. (2026). The Impact of Self-Heating on Single-Event Transient Effect in Triple-Layer Stacked Nanosheets: A TCAD Simulation. Electronics, 15(1), 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010085