AuditableLLM: A Hash-Chain-Backed, Compliance-Aware Auditable Framework for Large Language Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

- This work designs a unified audit pipeline that supports diverse model update mechanisms, including full-parameter fine-tuning, parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT), and unlearning, while preserving task utility and model stability in the LoRA-based experimental setting.

- This work develops an audit layer that records verifiable, hash-chained logs of update events and metadata, enabling third-party verification without costly cryptographic primitives.

- This work introduces a multi-level verification suite that combines behavioral, parametric, and risk-oriented diagnostics to assess consistency and compliance properties of the audited adaptation process.

- This work demonstrates the practicality of the framework through experiments on LLM adaptation and data deletion tasks using the LLaMA model family with LoRA adapters and the MovieLens dataset.

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. Background

2.1.1. LLM Adaptation and PEFT

2.1.2. Continual Learning and Machine Unlearning

2.1.3. Verifiable Training and Hash-Chain Auditing

2.2. Related Work

2.2.1. Auditable and Verifiable Training

2.2.2. Auditable Logging, Blockchain, and FL-Based Auditing

2.2.3. Unlearning Verification

2.2.4. Membership Inference Attacks and Machine Unlearning

2.2.5. Comparison with the Proposed Framework

3. System Model and Design Objectives

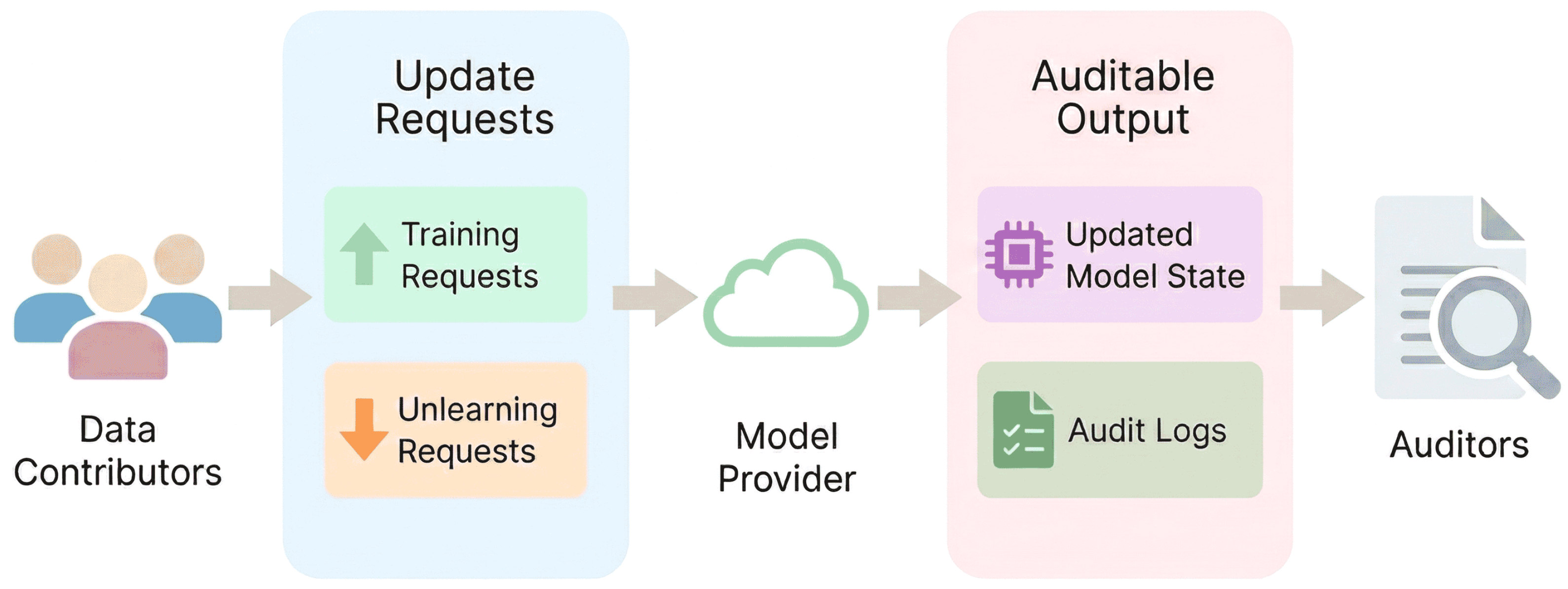

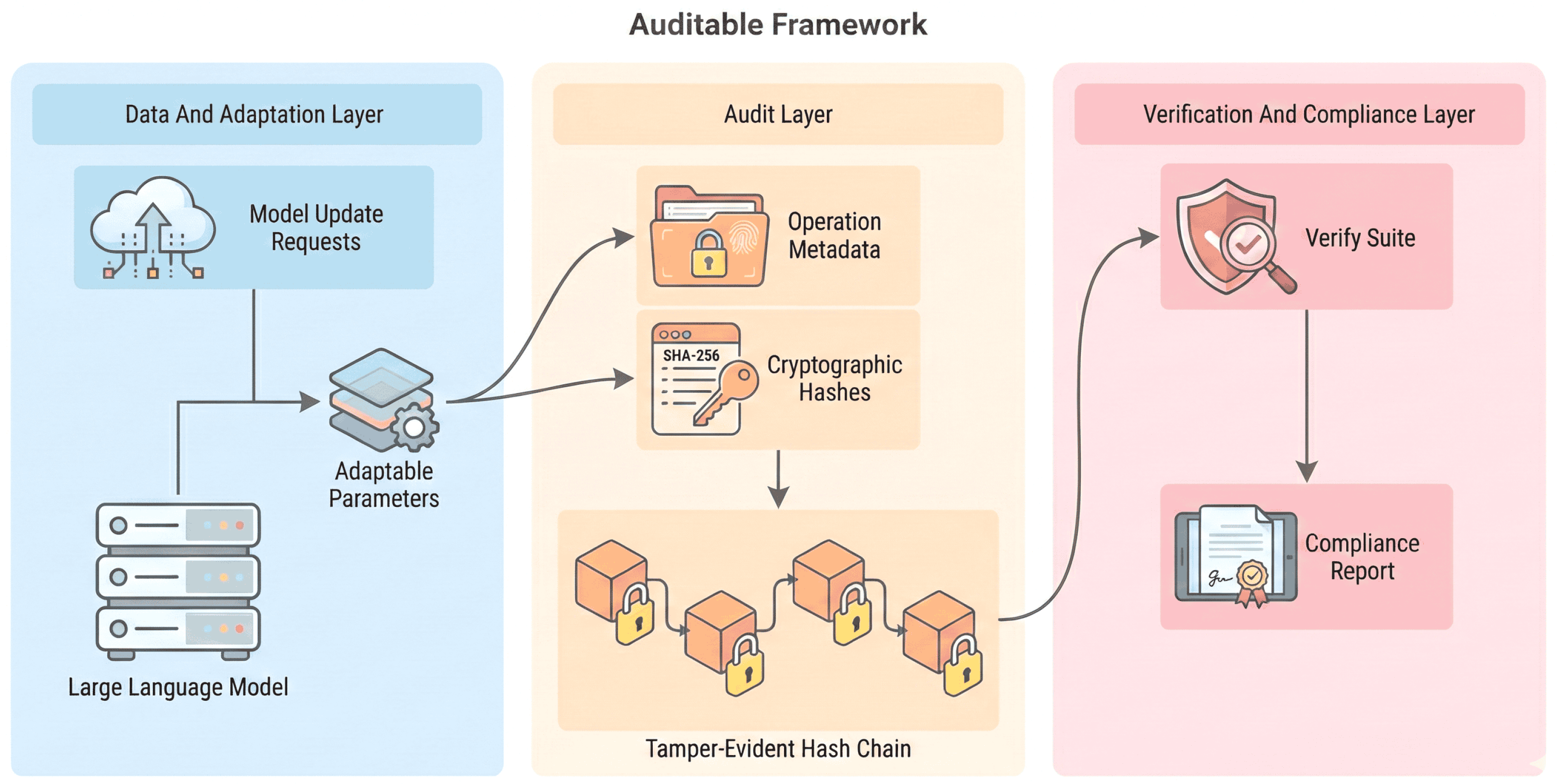

3.1. System Model Overview

3.2. Conceptual Components

3.2.1. Data and Adaptation Layer

3.2.2. Audit Layer

3.2.3. Verification and Compliance Layer

3.3. Design Objectives

4. Methodology and System Design

4.1. Methodological Rationale and Pipeline

4.2. Unified Update Mechanism

4.2.1. General Formulation

4.2.2. Parameter-Efficient Realization

4.2.3. Audit Integration

4.3. Audit Layer Construction

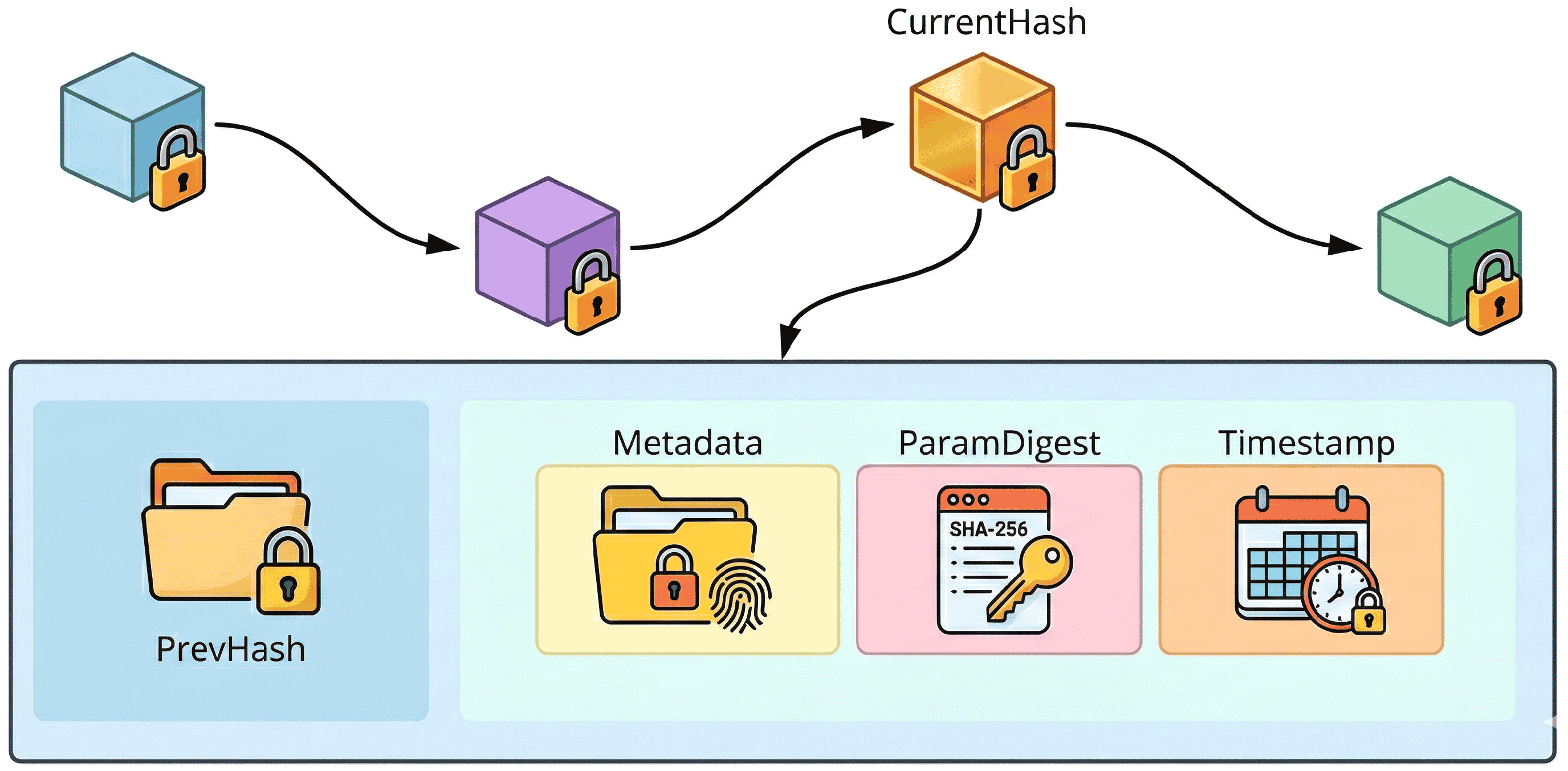

4.3.1. Audit Record Structure

4.3.2. Hash-Chain Construction

| Algorithm 1: Tamper-Evident Audit Chain Construction for AuditableLLM |

| Input: Previous hash , operation metadata , parameter delta , timestamp t |

| Output: Updated chain state |

| 1 Compute parameter digest |

| 2 Assemble record |

| 3 Compute new chain hash |

| 4 Store and in the append-only audit log |

| 5 return |

4.3.3. Provider-Side Procedure

4.3.4. Design Considerations

4.3.5. Log Storage and Retention

4.4. Verification and Compliance Layer

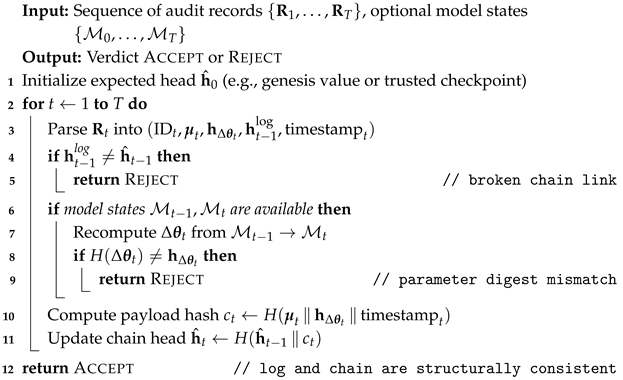

4.4.1. Structural Verification

- Hash-Chain Validation: Ensures that audit records form an unbroken chronological chain, confirming that no record has been inserted, removed, or modified.

- Parameter Commitment Verification: Recomputes digest commitments from model parameters and checks equality with logged commitments, verifying that the recorded deltas match actual model updates.

4.4.2. Computational Complexity

| Algorithm 2: Auditor-side verification of audit log and hash chain |

|

4.4.3. Verification Procedure

4.4.4. Behavioral Verification

4.4.5. Compliance Certification

4.4.6. Operational Flexibility

4.5. Threat Model and Security Assurance

4.5.1. Adversary Model

4.5.2. Malicious Clients/Contributors

4.5.3. Detection and Defense

4.5.4. Behavioral Anomaly Detection

4.5.5. Trust Boundary

4.5.6. Security Assurance

4.6. Integration and Problem-Solution Alignment

5. Experiments

5.1. Experiment Overview

- E0: Unified Audit Pipeline validates the framework-level stability, integrity, and efficiency of the hash-chained audit layer.

- E1: Auditable Fine-tuning verifies that the audit layer integrates into fine-tuning without affecting model performance or convergence stability.

- E2: Auditable Unlearning examines whether audit-integrated unlearning preserves forgetting efficacy and utility retention relative to the non-audited baseline.

- E3: Membership Inference Robustness evaluates whether unlearned models reduce membership leakage on the forget set to the level of a retrained-from-scratch baseline.

5.2. Experimental Setup

5.2.1. Dataset

5.2.2. Model

5.2.3. Hardware

5.2.4. Training Procedure

5.2.5. Membership Inference Protocol

5.2.6. Reproducibility Details

5.3. E0: Unified Audit Pipeline

5.3.1. Purpose

5.3.2. Method

- E0-A: Technical Integrity. A canonical audit manifest of 1000 entries is created, and three controlled tampering types are introduced: record deletion, record reordering, and digest corruption. Each modified manifest is independently verified using the verification suite, which checks chained-hash consistency and traceability. The verifier reports whether tampering is detected, the index of the first corrupted entry, and the total verification time.

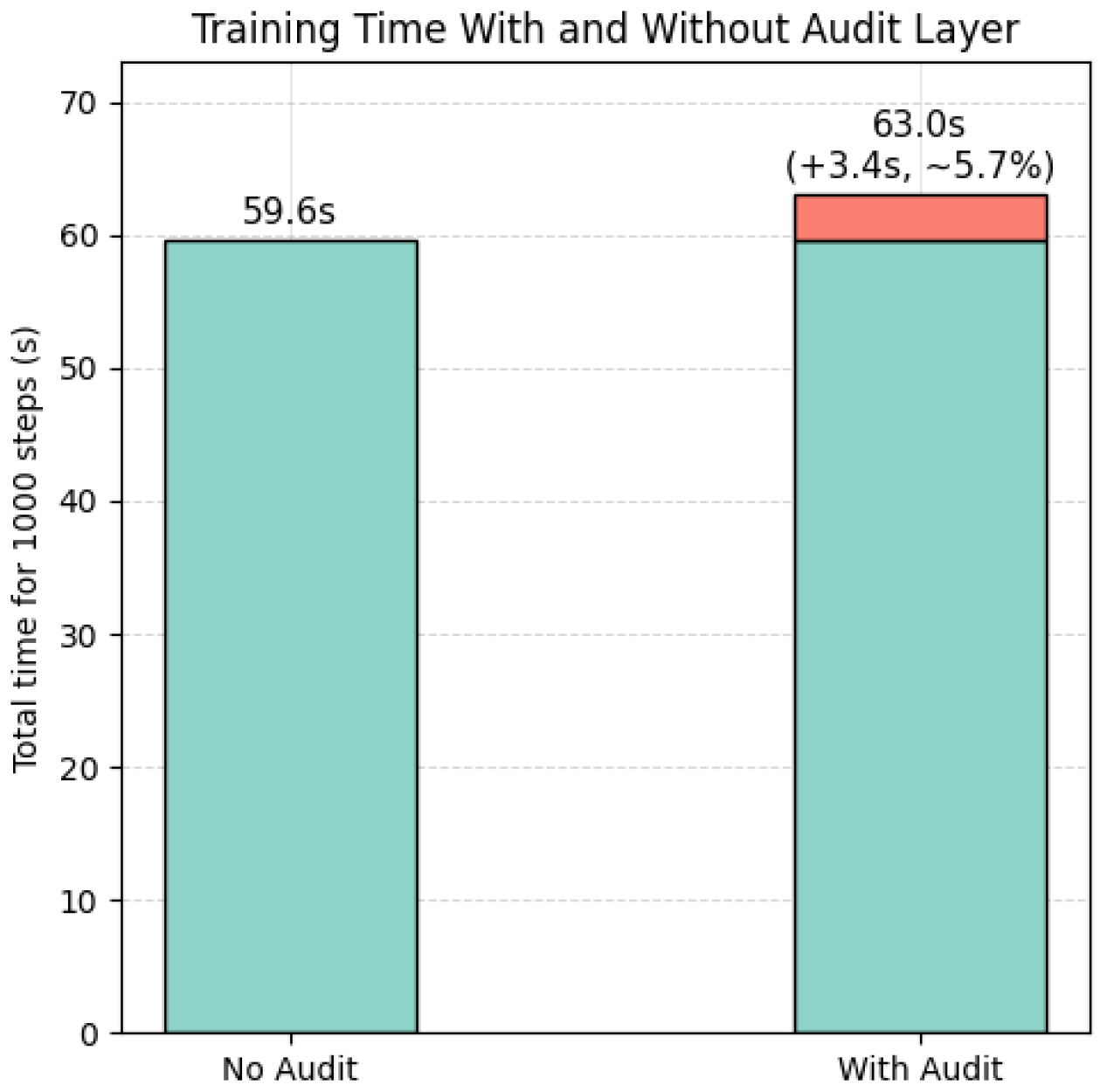

- E0-B: Audit Efficiency. The runtime and storage overhead introduced by the audit process are measured relative to a non-audited baseline. Metrics include per-step latency, total slowdown, raw and compressed log size, and verification time as a function of record count T. Each configuration is averaged over five independent runs on the same hardware described in Section 5.2.

5.3.3. Results

5.3.4. Discussion

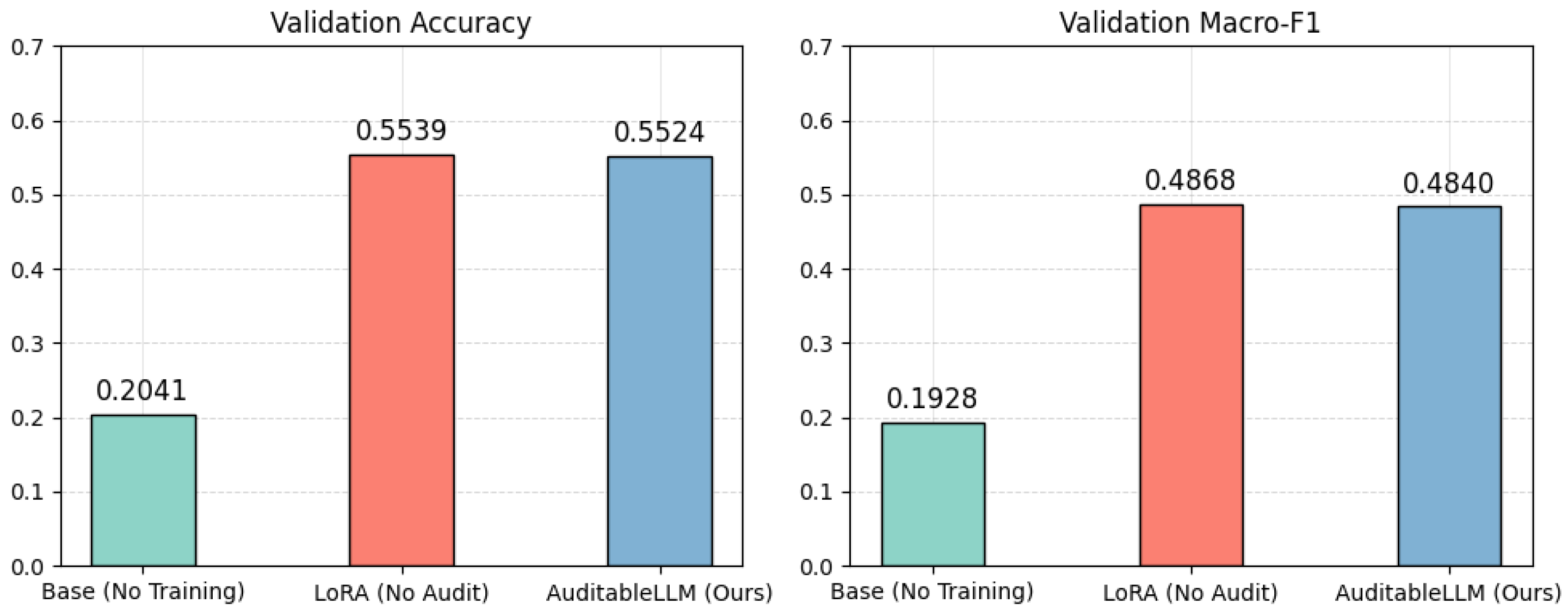

5.4. E1: Auditable Fine-Tuning

5.4.1. Purpose

5.4.2. Method

- LoRA Fine-tuning (No Audit)—baseline fine-tuning without audit logging.

- AuditableLLM (Ours)—identical fine-tuning setup with the audit layer enabled, which records operation metadata, cryptographic digests, and hash-chain links at every step.

5.4.3. Results

5.4.4. Discussion

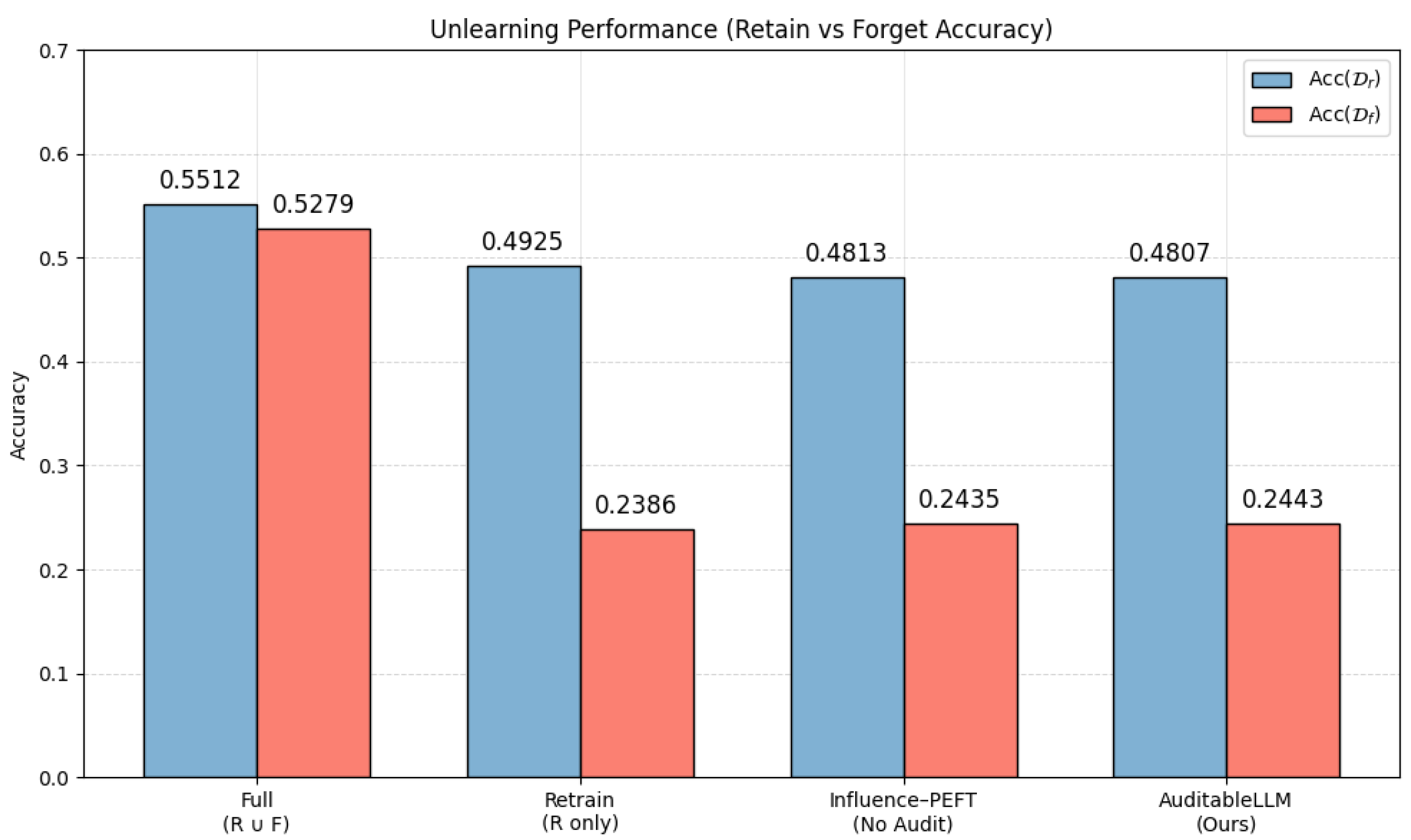

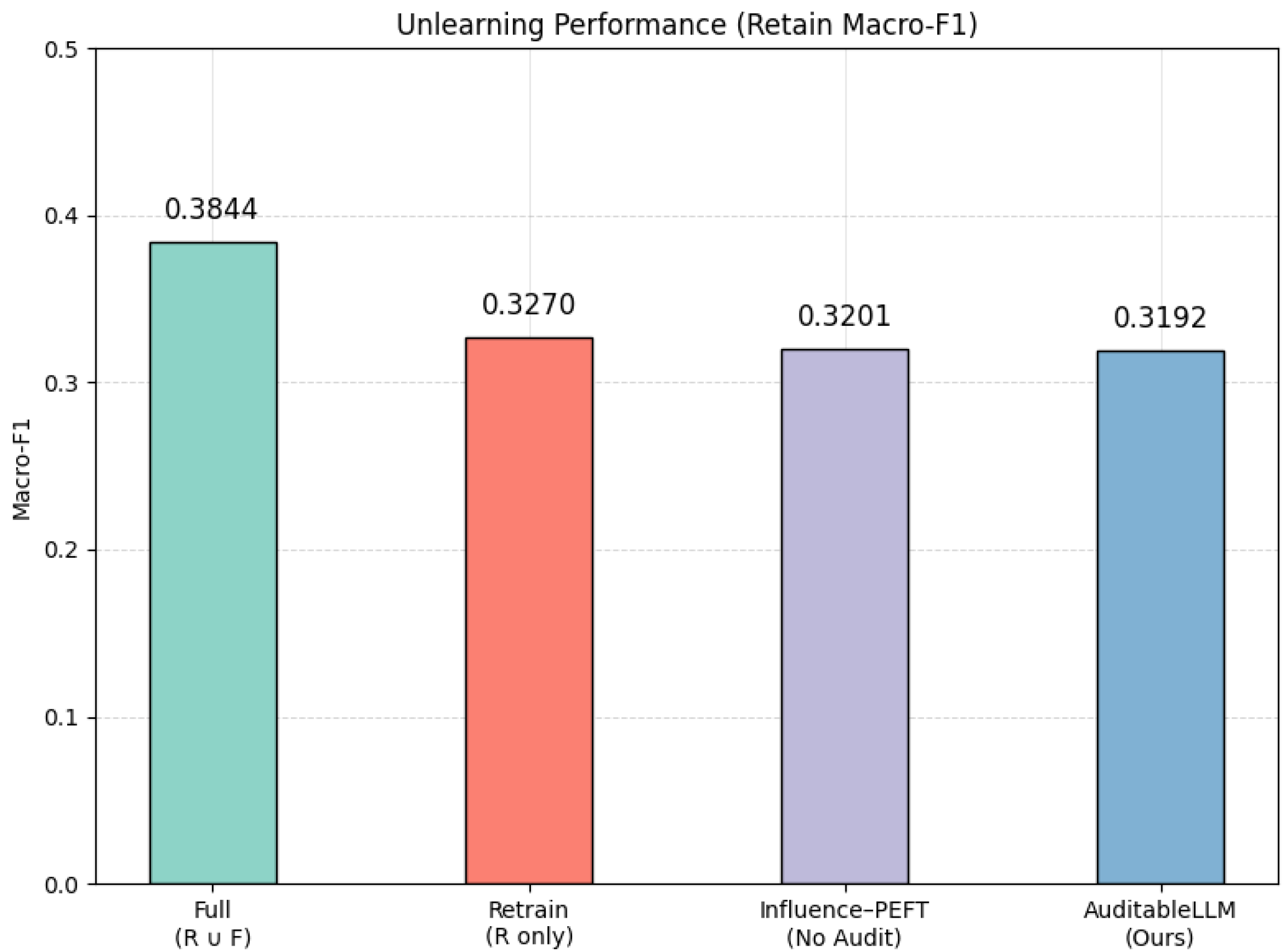

5.5. E2: Auditable Unlearning

5.5.1. Purpose

5.5.2. Method

- Full Training ()—baseline model trained on all data.

- Retrain (R only)—model retrained from scratch excluding deleted data.

- Influence-PEFT (No Audit)—standard influence-based unlearning baseline.

- AuditableLLM (Ours)—same unlearning process with audit layer integration.

5.5.3. Results

5.5.4. Discussion

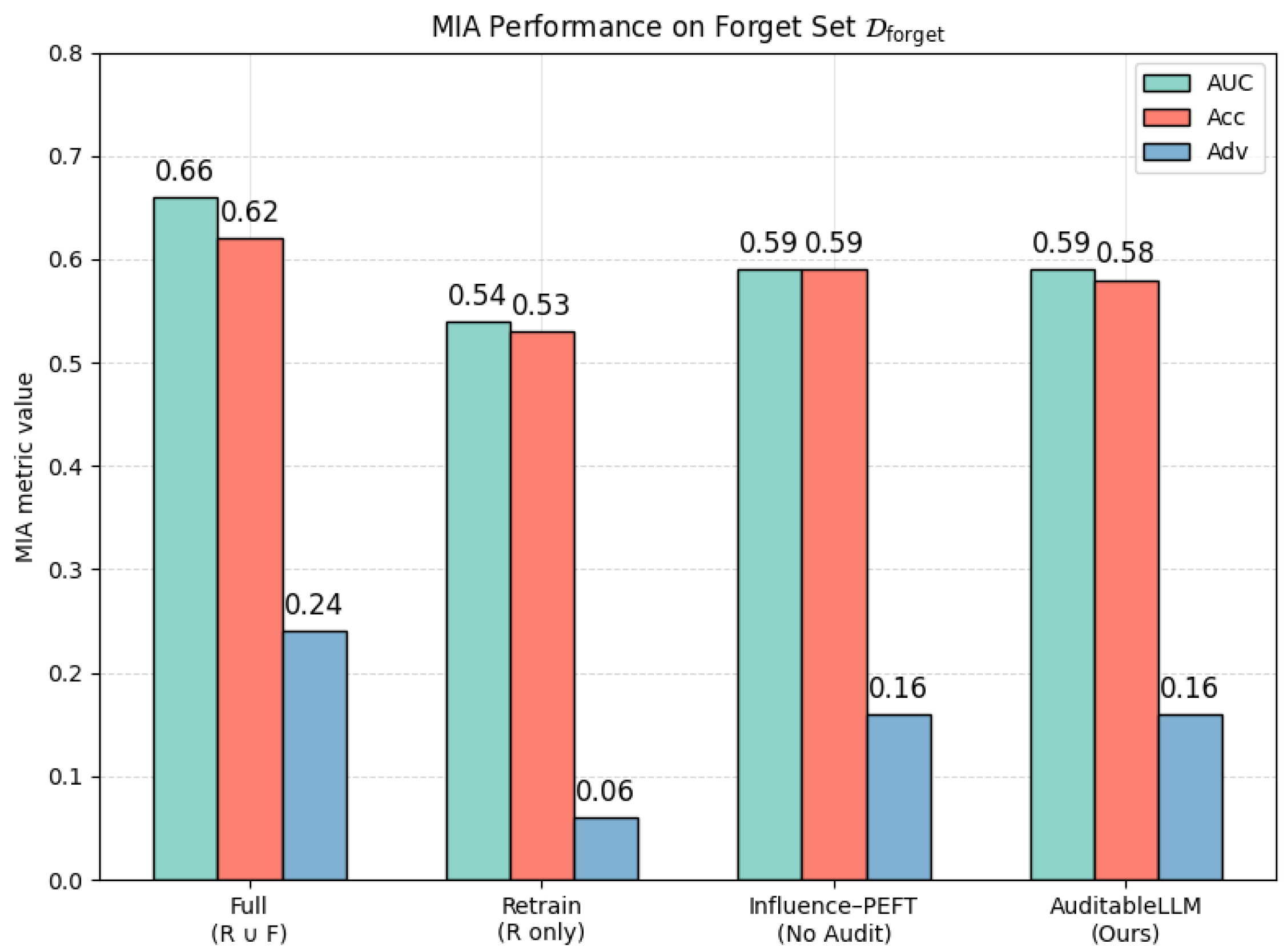

5.6. E3: Membership Inference Robustness

5.6.1. Purpose

5.6.2. Method

- Full Training ()—baseline model trained on all data.

- Retrain (R only)—model retrained from scratch excluding deleted data.

- Influence–PEFT (No Audit)—influence-based unlearning baseline.

- AuditableLLM (Ours)—same unlearning process with audit layer integration.

5.6.3. Results

5.6.4. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Limitations and Future Directions

- Dataset scale and external validity. The empirical evaluation is conducted in a small-to-mid-scale setting and uses a lightweight benchmark to enable repeated, instrumented adaptation and unlearning runs. Therefore, the current results primarily substantiate the feasibility, traceability, and overhead characteristics of the audit layer. The auditing mechanism itself is designed to attach to update transactions and its cost is driven primarily by the volume of logged update events and hash evaluations rather than the dataset size alone.

- Scalability and deployment. Extending the audit abstraction to frontier-scale LLMs and real-time MLaaS settings. In these environments, asynchronous updates, multi-tenant pipelines, and streaming adaptation introduce additional constraints for both performance and verifiability.

- Stronger cryptographic assurance. The present hash-chained audit layer is deliberately positioned as a lightweight, tamper-evident logging mechanism for LoRA-based adaptation under an honest-but-curious model provider. Extending these guarantees to stronger adversaries—for example, a fully malicious provider who trains models offline and later reports a fabricated but self-consistent history—calls for additional roots of trust (e.g., trusted time-stamping services, hardware-secured or remotely attested logging) and, potentially, the integration of heavier cryptographic proof systems such as proofs-of-learning and zero-knowledge proofs of training or unlearning. A natural direction for future work is to explore hybrid constructions in which AuditableLLM supplies the lightweight hash-chained logging substrate, while PoL- or ZK-style attestations (or trusted hardware) provide end-to-end origin authentication in the fully malicious setting.

- Cross-paradigm generalization. Applying the audit layer to additional model adaptation paradigms, such as prompt tuning, retrieval-augmented generation (RAG), and federated model updates, to validate the framework’s interoperability across heterogeneous architectures.

- Governance, privacy, and longitudinal assurance. Developing standardized evaluation benchmarks for audit persistence, data influence stability, and multi-cycle reliability. The hash-chain-backed audit layer already provides a chronological, tamper-evident view of all adaptation steps together with metadata that summarizes data provenance and training or unlearning configurations. This structure can be leveraged to investigate anomalous behavior, attribute it to specific updates, and roll back to known-good checkpoints, and it is naturally compatible with poisoning-aware and privacy-aware training pipelines. A promising direction for future work is to systematically integrate AuditableLLM with poisoning-robust and differentially private learning or unlearning algorithms. Such efforts could support the creation of auditable compliance standards bridging technical verification with legal accountability.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Union. Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 (General Data Protection Regulation); Official Journal of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016; pp. 1–88. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Ding, M.; Shaham, S.; Rahayu, W.; Farokhi, F.; Lin, Z. When Machine Learning Meets Privacy: A Survey and Outlook. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022, 54, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, E.; Otero, B.; Canal, R. A Survey of Machine and Deep Learning Methods for Privacy Protection in the Internet of Things. Sensors 2023, 23, 1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feretzakis, G.; Papaspyridis, K.; Gkoulalas-Divanis, A.; Verykios, V.S. Privacy-Preserving Techniques in Generative AI and Large Language Models: A Narrative Review. Information 2024, 15, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, T.; Yu, G.; Wang, Q. Privacy in Foundation Models: A Conceptual Framework for System Design. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2311.06998. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, B.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, X.; Yu, G.; Wang, Q.; Sun, C.; Li, C.; Qi, X.; He, Y.; Ni, W.; et al. SoK: Semantic Privacy in Large Language Models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.23603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houlsby, N.; Giurgiu, A.; Jastrzebski, S.; Morrone, B.; De Laroussilhe, Q.; Gesmundo, A.; Attariyan, M.; Gelly, S. Parameter-Efficient Transfer Learning for NLP. In Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning, Long Beach, CA, USA, 10–15 June 2019; Volume 97, pp. 2790–2799. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, E.J.; Shen, Y.; Wallis, P.; Allen-Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, W. LoRA: Low-rank Adaptation of Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, Virtual, 25–29 April 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dettmers, T.; Pagnoni, A.; Holtzman, A.; Zettlemoyer, L. QLoRA: Efficient Finetuning of Quantized Llms. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Oh, A., Naumann, T., Globerson, A., Saenko, K., Hardt, M., Levine, S., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2023; Volume 36, pp. 10088–10115. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco-Justicia, A.; Jebreel, N.; Manzanares, B.; Sánchez, D.; Domingo-Ferrer, J.; Collell, G.; Tan, K.E. Digital Forgetting in Large Language Models: A Survey of Unlearning Methods. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sai, S.; Mittal, U.; Chamola, V.; Huang, K.; Spinelli, I.; Scardapane, S.; Tan, Z.; Hussain, A. Machine Un-learning: An Overview of Techniques, Applications, and Future Directions. Cogn. Comput. 2024, 16, 482–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Li, Y.; Zhao, C.; Huai, M. A Survey of Security and Privacy Issues of Machine Unlearning. AI Mag. 2025, 46, e12209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yao, Y.; Jia, J.; Casper, S.; Baracaldo, N.; Hase, P.; Yao, Y.; Liu, C.Y.; Xu, X.; Li, H.; et al. Rethinking Machine Unlearning for Large Language Models. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2025, 7, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Yu, G.; Wang, Q.; Wang, X.; Ma, B.; Sun, C.; Ni, W.; Liu, R.P. Split Unlearning. In Proceedings of the 2025 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Taipei, Taiwan, 13–17 October 2025; pp. 948–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Yaghini, M.; Choquette-Choo, C.A.; Dullerud, N.; Thudi, A.; Chandrasekaran, V.; Papernot, N. Proof-of-Learning: Definitions and Practice. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), San Francisco, CA, USA, 24–27 May 2021; pp. 1039–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Jia, H.; Thudi, A.; Yaghini, M.; Choquette-Choo, C.A.; Dullerud, N.; Chandrasekaran, V.; Papernot, N. Proof-of-Learning Is Currently More Broken Than You Think. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 8th European Symposium on Security and Privacy (EuroS&P), Delft, The Netherlands, 3–7 July 2023; pp. 797–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, S.; Jiang, L.; Pan, S.; Cai, R.; Yang, S.; Yang, F. Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning in Large Language Models: A Survey of Methodologies. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Huynh, T.T.; Ren, Z.; Nguyen, P.L.; Liew, A.W.C.; Yin, H.; Nguyen, Q.V.H. A Survey of Machine Unlearning. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2025, 16, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le-Khac, U.N.; Truong, V.N. A Survey on Large Language Models Unlearning: Taxonomy, Evaluations, and Future Directions. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Shen, J.; Peng, M.; Lam, K.Y.; Yuan, X.; Liu, X. A Survey on Federated Unlearning: Challenges, Methods, and Future Directions. ACM Comput. Surv. 2025, 57, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, S.; Goel, A.; Jha, S.; Mahloujifar, S.; Mahmoody, M.; Policharla, G.V.; Wang, M. Experimenting with Zero-Knowledge Proofs of Training. In Proceedings of the 2023 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Copenhagen Denmark, 26–30 November 2023; pp. 1880–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Xu, J.; Chu, X.; Gao, S.; Yao, Y.; Gu, R.; Tang, Y. VFChain: Enabling Verifiable and Auditable Federated Learning via Blockchain Systems. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2022, 9, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, N.; Sun, K.; Wang, S.; Guitton, F.; Guo, Y. Privacy Preservation in Federated Learning: An Insightful Survey from the GDPR Perspective. Comput. Secur. 2021, 110, 102402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, L.; Nagisetty, V.; Ganesh, V. Amnesiac Machine Learning. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2021, 35, 11516–11524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Shen, J.; Liu, Z.; Tan, C.W.; Lam, K.Y. Toward Efficient and Certified Recovery From Poisoning Attacks in Federated Learning. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2025, 20, 2632–2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, B.C.; Amini, M.H.; Wu, Y. Security and Privacy Challenges of Large Language Models: A Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2025, 57, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Tian, Z.; Liu, A.; Yu, S. TAPE: Tailored Posterior Difference for Auditing of Machine Unlearning. In Proceedings of the ACM on Web Conference 2025, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 28 April–2 May 2025; pp. 3061–3072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokri, R.; Stronati, M.; Song, C.; Shmatikov, V. Membership Inference Attacks Against Machine Learning Models. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), San Jose, CA, USA, 22–26 May 2017; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr, M.; Shokri, R.; Houmansadr, A. Comprehensive Privacy Analysis of Deep Learning: Passive and Active White-box Inference Attacks against Centralized and Federated Learning. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), San Francisco, CA, USA, 19–23 May 2019; pp. 739–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, P.W.; Liang, P. Understanding Black-Box Predictions via Influence Functions. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 6–11 August 2017; Volume 70, pp. 1885–1894. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhofer, T.; Riepel, D.; Chandrasekaran, V.; Ghosh, E.; Ohrimenko, O.; Papernot, N. Verifiable and Provably Secure Machine Unlearning. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE Conference on Secure and Trustworthy Machine Learning (SaTML), Copenhagen, Denmark, 9–11 April 2025; pp. 479–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaik, T.; Tao, X.; Xie, H.; Li, L.; Zhu, X.; Li, Q. Exploring the Landscape of Machine Unlearning: A Comprehensive Survey and Taxonomy. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2025, 36, 11676–11696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thudi, A.; Jia, H.; Shumailov, I.; Papernot, N. On the Necessity of Auditable Algorithmic Definitions for Machine Unlearning. In Proceedings of the 31st USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 22), Boston, MA, USA, 10–12 August 2022; pp. 4007–4022. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, C.; Wu, J.; Yuan, Y.; Lu, J.; Zhang, K.; Su, A.; Wang, X.; He, X. Unified Parameter-Efficient Unlearning for LLMs. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Conference on Learning Representations, Singapore, 24–28 April 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Hu, Z.; Bai, Y.; Wu, J.; Wang, Q.; Feng, F. Recommendation Unlearning via Influence Function. ACM Trans. Recomm. Syst. 2025, 3, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnecke, A.; Pirch, L.; Wressnegger, C.; Rieck, K. Machine Unlearning of Features and Labels. In Proceedings of the 2023 Network and Distributed System Security Symposium, San Diego, CA, USA, 27 February–3 March 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichert, L.; Sikdar, S. Rethinking Evaluation Methods for Machine Unlearning. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2024, Miami, FL, USA, 12–16 November 2024; pp. 4727–4739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, F.M.; Konstan, J.A. The MovieLens Datasets: History and Context. ACM Trans. Interact. Intell. Syst. (TiiS) 2015, 5, 19:1–19:19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meta AI. Llama-3.2-1B-Instruct. Hugging Face Model Card, 2024. Available online: https://huggingface.co/meta-llama/Llama-3.2-1B-Instruct (accessed on 15 December 2025).

| Approach | Threat and Trust Model | Certified Object | Typical Deployment Requirement |

|---|---|---|---|

| PoL/PoT, ZK proofs of training [15,16,21] | Strong/fully malicious provider | Training executed as claimed (strong attestation of training provenance) | Requires proof-generation hooks, access to training transcripts/commitments, and verification infrastructure |

| Certified/verifiable unlearning, unlearning auditing [27,31,32,33] | Typically honest-but-curious to stronger settings (protocol-dependent) | Forgetting correctness/bounded influence of removed data | Often requires additional training steps, influence bounding, or extra evaluation rounds for certification |

| Blockchain-based audit logs [22] | Distributed trust/multi-party consensus | Tamper-resistant replicated history (ledger immutability) | Requires consensus/replication network and ledger maintenance in addition to local logging |

| Provenance/governance logging (no crypto chaining) [4,23] | Benign logging assumption | Operational lineage and documentation (non-cryptographic) | Standard logging pipeline; no cryptographic integrity binding |

| AuditableLLM (this work) | Honest-but-curious provider; verifiable third-party auditing | Tamper-evident update-history integrity + step-level traceability for adaptation/unlearning | Requires only local hash-chained logging and verification; no retraining proofs or consensus network |

| Approach | Verification Cost & Overhead |

|---|---|

| Proof-of-learning/proof-of-training (replay-based) [15,16] | |

| ZK proofs of training/verifiable computation (SNARK-based) [21] | |

| Verifiable/certified machine unlearning and unlearning auditing [27,31,32] | |

| Blockchain-based federated logging (e.g., VFChain) [22] | |

| Standard provenance logging/governance (no cryptographic chaining) [4,23] | |

| AuditableLLM (this work) |

| Design Objective | Challenge | Methodological Realization |

|---|---|---|

| System-Level Accountability | Absence of verifiable lineage for model evolution and data operations. | Hash-chained audit logs with cryptographic digests to ensure tamper-evident, verifiable update history. |

| Technical Efficiency | High retraining cost and instability in parameter updates. | Parameter-efficient modular fine-tuning (LoRA/QLoRA) enabling lightweight, stable model adaptation. |

| Verifiability and Reliability | Unverifiable or inconsistent model behavior after adaptation. | Dual-layer verification combining structural hash checks and behavioral consistency evaluation. |

| Tamper Type | Detection Rate | Avg. Verify Time |

|---|---|---|

| Record deletion | 100% | 0.037 s |

| Record reordering | 100% | 0.038 s |

| Hash corruption | 100% | 0.037 s |

| Metric | Value | Per Step | Main Contributor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time overhead | +3.4 s | 3.4 ms | Hash computation (97.1%) |

| Log size (raw) | 0.61 MB | 611 B | Digest fields (53.2%) |

| Log size (gzip) | 0.15 MB | 153 B | – |

| Verification (offline) | 0.04 s/1k | Hash recomputation |

| Method | Acc | F1 |

|---|---|---|

| Base Model (No Training) | 0.2041 | 0.1928 |

| LoRA Fine-tuning (No Audit) | 0.5539 | 0.4868 |

| AuditableLLM (Ours) | 0.5524 | 0.4840 |

| Method | Acc () | F1 () | Acc () |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full Training () | 0.5512 | 0.3844 | 0.5279 |

| Retrain (R only) | 0.4925 | 0.3270 | 0.2386 |

| Influence-PEFT (No Audit) | 0.4813 | 0.3201 | 0.2435 |

| AuditableLLM (Ours) | 0.4807 | 0.3192 | 0.2443 |

| Method | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Full Training () | 0.66 | 0.62 | 0.24 |

| Retrain (R only) | 0.54 | 0.53 | 0.06 |

| Influence–PEFT (No Audit) | 0.59 | 0.59 | 0.16 |

| AuditableLLM (Ours) | 0.59 | 0.58 | 0.16 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, D.; Yu, G.; Wang, X.; Liang, B. AuditableLLM: A Hash-Chain-Backed, Compliance-Aware Auditable Framework for Large Language Models. Electronics 2026, 15, 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010056

Li D, Yu G, Wang X, Liang B. AuditableLLM: A Hash-Chain-Backed, Compliance-Aware Auditable Framework for Large Language Models. Electronics. 2026; 15(1):56. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010056

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Delong, Guangsheng Yu, Xu Wang, and Bin Liang. 2026. "AuditableLLM: A Hash-Chain-Backed, Compliance-Aware Auditable Framework for Large Language Models" Electronics 15, no. 1: 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010056

APA StyleLi, D., Yu, G., Wang, X., & Liang, B. (2026). AuditableLLM: A Hash-Chain-Backed, Compliance-Aware Auditable Framework for Large Language Models. Electronics, 15(1), 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010056