Exploring the Cognitive Capabilities of Large Language Models in Autonomous and Swarm Navigation Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Introduction to the Project

- RQ1: Can a generic multimodal LLM generate semantically valid and safe navigation commands for a mobile robot without task-specific fine-tuning?

- RQ2: What are the latency implications and stability trade-offs of a client–server architecture in the context of real-time linguistic control?

- RQ3: How can nondeterministic model outputs be effectively constrained to ensure operational safety in physical environments?

1.2. Related Work

1.3. Extended Literature Review

1.3.1. From Foundation Models to Edge Deployment

1.3.2. Addressing Hallucination and Safety

1.3.3. Toward Language-Driven Swarms

2. Materials and Methods

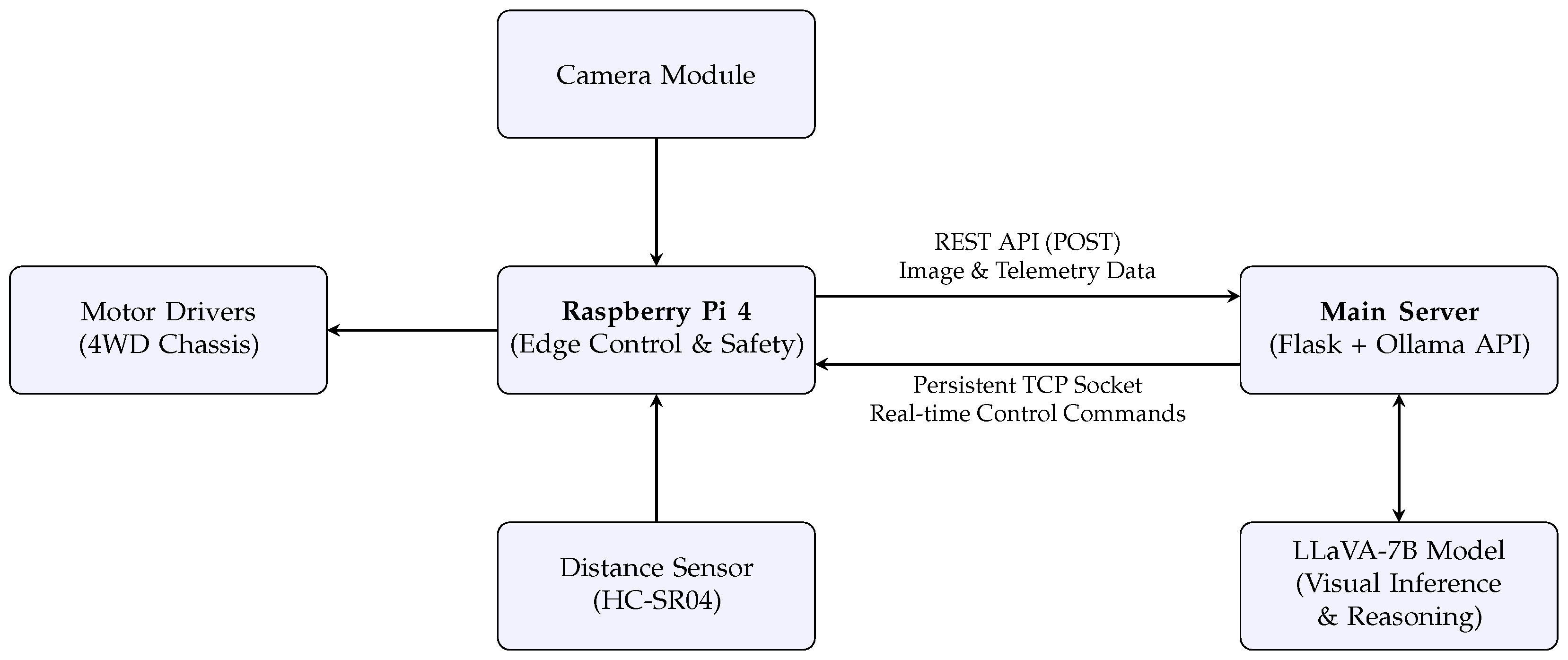

2.1. System Overview

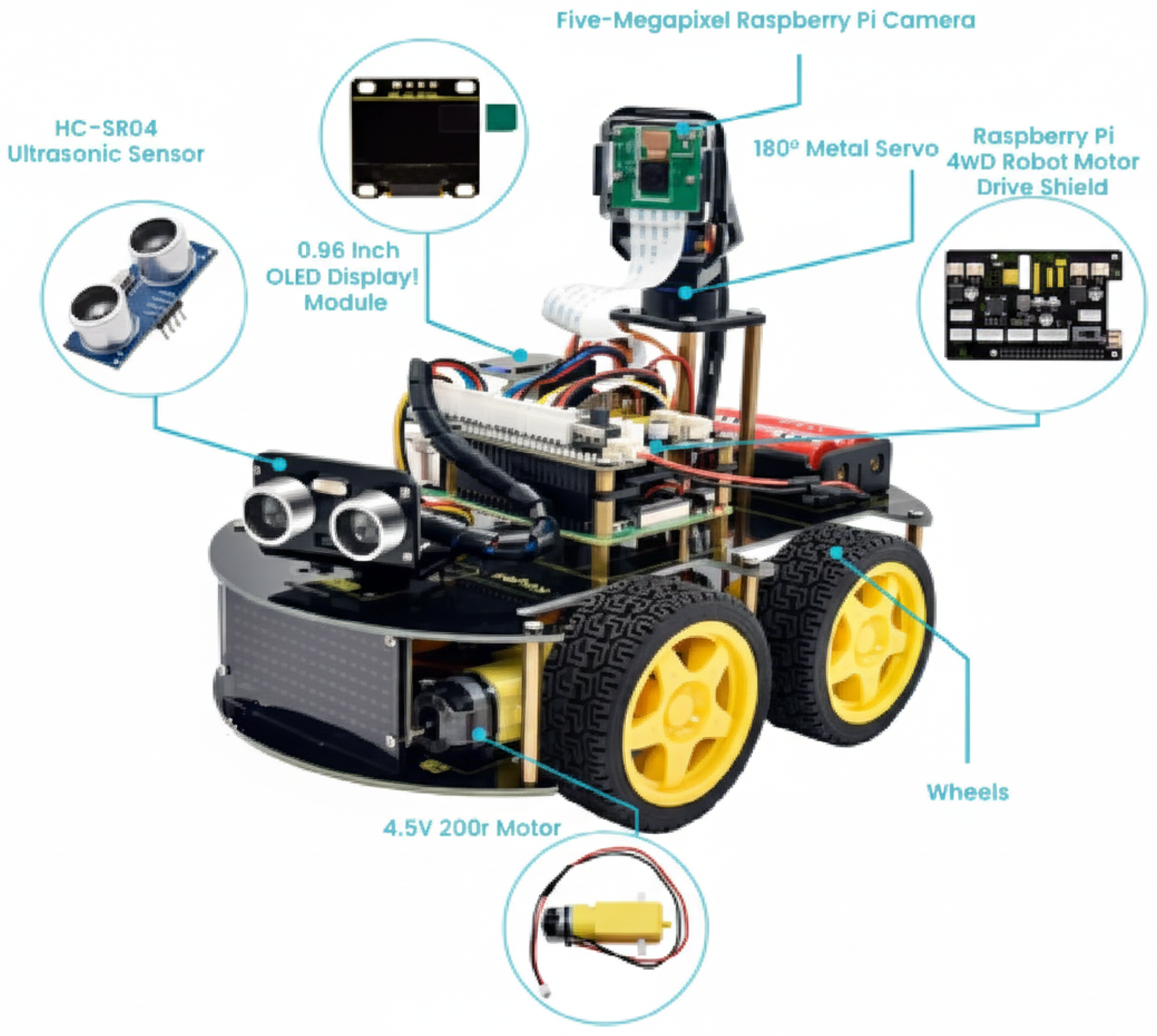

2.2. Robot Hardware Setup (Raspberry Pi 4)

- Five-megapixel Raspberry Pi Camera on a metal servo (active viewpoint control).

- HC-SR04 ultrasonic sensor (proximity and emergency stop).

- 4WD motor driver shield for PWM speed/steering, four V 200 rpm DC motors.

- 0.96 in OLED display and 8 × 16 LED matrix (diagnostics/status).

- Dual 18650 battery pack with DC–DC regulation (separate rails for logic and motors).

2.3. Software Environment and Model Configuration

2.4. Prompt Engineering

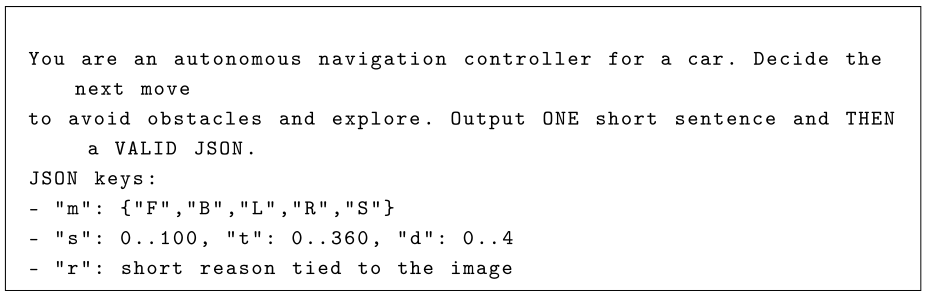

| Listing 1. System prompt (excerpt) and required JSON keys. |

|

2.5. Communication Protocol

- Robot → Server (REST, port 5053).

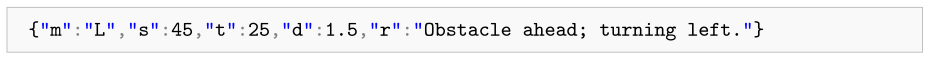

| Listing 2. Example decision JSON returned by the server. |

|

- Server → Robot (TCP socket).

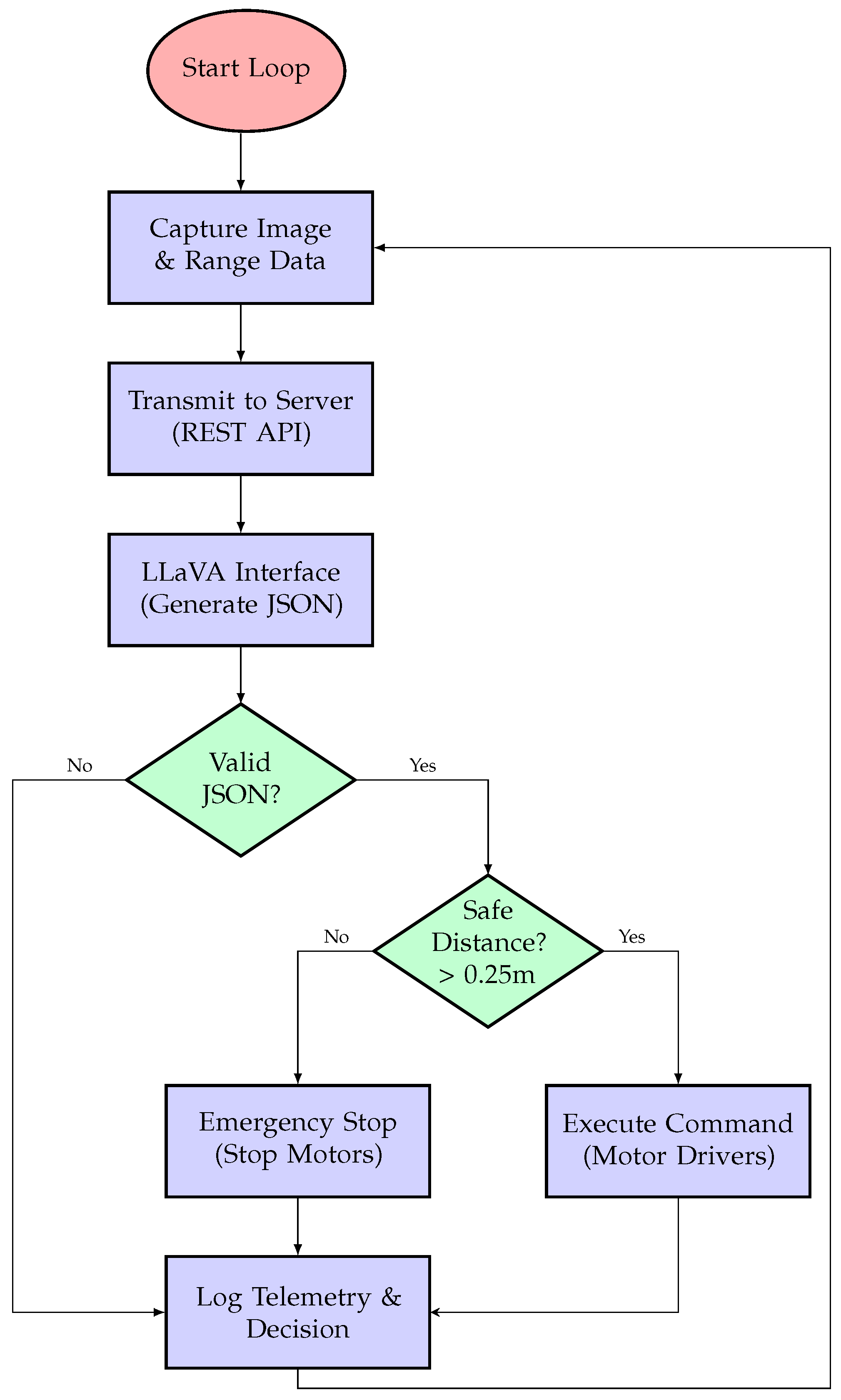

2.6. Safety and Validation

2.7. Experimental Procedure and Metrics

3. Experimental Setup and Evaluation Procedure

3.1. Tested Models

- LLaVA (standard 7B)—reference model with baseline prompt and system configuration [26].

3.2. Experimental Procedure

- Image acquisition: The Raspberry Pi 4 captured a frame from the front camera and the current distance from the ultrasonic sensor.

- Feature extraction: Lightweight edge-detection and object-localization routines identified elements such as walls, openings, or obstacles. The detected features (e.g., “obstacle front-left”) were encoded as text tokens and included in the model prompt.

- Inference via LLM: The chosen model (LLaVA or Llama3) received the symbolic description and, where applicable, the raw image. It generated a scene description and a JSON-formatted command defining motion parameters.

- Command validation and execution: The Raspberry Pi validated the JSON output against a schema and clamped values (, , ). Safe commands were then executed.

- Safety override: The ultrasonic distance sensor acted as a final safety layer; if the measured distance dropped below m, an emergency “Stop” command was triggered.

- Logging and feedback: Each step—image, JSON command, reasoning text, and execution result—was logged for quantitative and qualitative analysis.

3.3. Evaluation Metrics

- Inference latency (ms)—time between image capture and command execution.

- JSON validity rate (%)—share of syntactically correct control outputs.

- Decision coherence (%)—proportion of textual reasonings consistent with visual context.

- Collision avoidance rate (%)—fraction of cycles completed without triggering the safety override.

- Motion smoothness (%)—ratio of planned to corrective (stop/reverse) actions.

- Success rate (%)—proportion of autonomous runs that completed the predefined exploration horizon without any collision or safety-stop event. In this exploratory setting, this task-level measure complements the step-wise collision avoidance and smoothness metrics.

3.4. Experimental Environment

3.5. Ethical and Safety Considerations

3.6. Results Summary

3.7. Preliminary Observations

4. Results

4.1. Quantitative Performance Analysis

4.2. Scenario-Based Behavioral Analysis

4.2.1. Scenario A: Static Obstacles (Furniture)

4.2.2. Scenario B: Dynamic Actors (Pedestrians)

5. Discussion

5.1. Multimodal vs. Unimodal Reasoning

5.2. Qualitative Analysis of Reasoning and Failure Modes

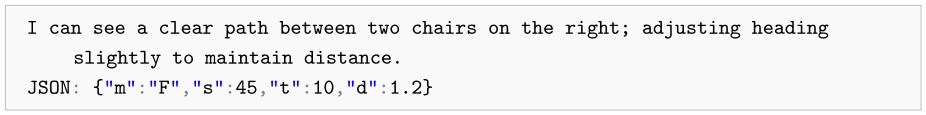

| Listing 3. Successful reasoning example (LLaVA-7B). |

|

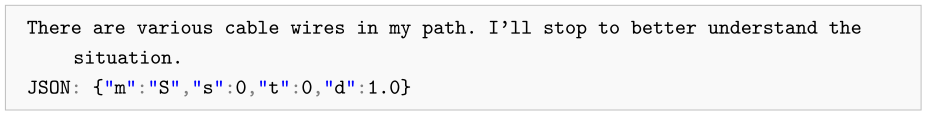

| Listing 4. Failure-mode example (LLaVA-standard). |

|

5.3. Latency and Architecture Trade-Offs

5.4. Safety and Determinism

5.5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| VLM | Vision–Language Model |

| MLLM | Multimodal Large Language Model |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| RL | Reinforcement Learning |

| REST | Representational State Transfer |

| TCP | Transmission Control Protocol |

| JSON | JavaScript Object Notation |

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| OCR | Optical Character Recognition |

| PWM | Pulse Width Modulation |

| FPS | Frames Per Second |

References

- Naveed, H.; Khan, A.U.; Qiu, S.; Saqib, M.; Anwar, S.; Usman, M.; Akhtar, N.; Barnes, N.; Mian, A. A comprehensive overview of large language models. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2025, 16, 1–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Katsumata, K.; Javanmardi, E.; Tsukada, M. Large Language Models for Human-Like Autonomous Driving: A Survey. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 27th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), St. Louis, MO, USA, 24–27 September 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Wang, M.; Zhang, J.; Li, D.; Duan, J. A Review of Large Language Models: Fundamental Architectures, Key Technological Evolutions, Interdisciplinary Technologies Integration, Optimization and Compression Techniques, Applications, and Challenges. Electronics 2024, 13, 5040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, D.; Osiński, B.; Levine, S. Lm-nav: Robotic navigation with large pre-trained models of language, vision, and action. In Proceedings of the Conference on Robot Learning, PMLR, Auckland, New Zealand, 14–18 December 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, E.; Zhao, Z.; Guo, Y.; Wong, K.K.; Li, Z.; Zhao, H. DriveGPT4: Interpretable End-to-End Autonomous Driving via Large Language Model. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 8186–8193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Ma, Y.; Cao, X.; Ye, W.; Zhou, Y.; Liang, K.; Chen, J.; Lu, J.; Yang, Z.; Liao, Y.; et al. A Survey on Multimodal Large Language Models for Autonomous Driving. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision Workshops (WACVW), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 4–8 January 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrun, S.; Burgard, W.; Fox, D. Probabilistic Robotics; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dorigo, M.; Theraulaz, G.; Trianni, V. Swarm Robotics: Past, Present, and Future. Proc. IEEE 2021, 109, 1152–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R.S.; Barto, A.G. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction, 2nd ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, W.; Wang, C.; Zhang, R.; Li, Y.; Wu, J.; Fei-Fei, L. VoxPoser: Composable 3D Value Maps for Robotic Manipulation with Language Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2307.05973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Song, Z.; Zhuang, Y.; Hao, J.; King, I. A Survey on Vision-Language-Action Models for Embodied AI. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.14093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, M.; Brohan, A.; Brown, N.; Chebotar, Y.; Finn, C.; Gopalakrishnan, K.; Hausman, K.; Herzog, A.; Ho, D.; Hsu, J.; et al. Do as I Can, Not as I Say: Grounding Language in Robotic Affordances. In Proceedings of the 6th Conference on Robot Learning (CoRL), Auckland, New Zealand, 14–18 December 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Pertsch, K.; Karamcheti, S.; Xiao, T.; Balakrishna, A.; Wu, B.; Le, A.; Lu, C.; Xu, E.; Vuong, Q.; et al. OpenVLA: An Open-Source Vision-Language-Action Model. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.09246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driess, D.; Xia, F.; Sajjadi, M.S.M.; Lynch, C.; Chowdhery, A.; Ichter, B.; Wahid, A.; Tompson, J.; Vuong, Q.; Yu, T.; et al. PaLM-E: An Embodied Multimodal Language Model. In Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Machine Learning, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–29 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Brohan, A.; Brown, N.; Carbajal, J.; Chebotar, Y.; Chen, X.; Choromanski, K.; Ding, T.; Driess, D.; Dubey, A.; Finn, C.; et al. RT-2: Vision-Language-Action Models Transfer Web Knowledge to Robotic Control. In Proceedings of the 7th Conference on Robot Learning, PMLR, Atlanta, GA, USA, 6–9 November 2023; Volume 229, pp. 2165–2183. [Google Scholar]

- Brambilla, M.; Ferrante, E.; Birattari, M.; Dorigo, M. Swarm Robotics: A Review from the Swarm Engineering Perspective. Swarm Intell. 2013, 7, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; An, Z.; Abrar, S.; Zhou, L. Large Language Models for Multi-Robot Systems: A Survey. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.03814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Introducing Meta Llama 3: The Most Capable Openly Available LLM to Date. Meta AI. 2024. Available online: https://ai.meta.com/results/?q=Llama+3%3A+The+Next+Generation+of+Llama+Foundation+Models (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Chu, X.; Qiao, L.; Lin, X.; Xu, S.; Yang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Wei, F.; Zhang, B.; Wei, X.; Shen, C. MobileVLM: A Fast, Strong and Open Vision Language Assistant for Mobile Devices. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2312.16886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Hu, J.; Mu, R. Safety of Embodied Navigation: A Survey. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.05855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawalski, M.; Chen, W.; Pertsch, K.; Mess, O.; Finn, C.; Levine, S. Embodied Chain-of-Thought Reasoning for Vision-Language-Action Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.08693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Raman, S.S.; Shah, A.; Tellex, S. Plug in the Safety Chip: Enforcing Constraints for LLM-driven Robot Agents. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Yokohama, Japan, 13–17 May 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravichandran, Z.; Robey, A.; Kumar, V.; Pappas, G.J.; Hassani, H. Safety Guardrails for LLM-Enabled Robots. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.07885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Zhao, J.; Yu, D.; Du, N.; Shafran, I.; Narasimhan, K.; Cao, Y. ReAct: Synergizing Reasoning and Acting in Language Models. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Vienna, Austria, 7–11 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- LLaVA: Large Language and Vision Assistant. Ollama Library. Available online: https://ollama.com/library/llava:7b (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- llava-hf/llava-1.5-7b-hf Model Card. Hugging Face. (Model Info. LLaVA-1.5 7B). Available online: https://huggingface.co/llava-hf/llava-1.5-7b-hf (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Grattafiori, A.; Dubey, A.; Jauhri, A.; Pandey, A.; Kadian, A.; Al-Dahle, A.; Letman, A.; Mathur, A.; Schelten, A.; Vaughan, A.; et al. The Llama 3 Herd of Models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2407.21783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payandeh, A.; Song, D.; Nazeri, M.; Liang, J.; Mukherjee, P.; Raj, A.H.; Kong, Y.; Manocha, D.; Xiao, X. Social-LLaVA: Enhancing Robot Navigation through Human-Language Reasoning in Social Spaces. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2311.12320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawte, V.; Chakraborty, S.; Pathak, A.; Sarkar, A.; Zaki, M.; Das, A.; Sheth, A.; Saha, T.; Gunti, N.; Roy, K.; et al. The Troubling Emergence of Hallucination in Large Language Models: An Extensive Definition, Quantification, and Prescriptive Remediations. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.04988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.; Gupta, K.D.; George, R.; Sarkar, M. Lite VLA: Efficient Vision-Language-Action Control on CPU-Bound Edge Robots. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2511.05642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.A.; Rahman, F.; Gupta, K.D.; Shujaee, K.; George, R. TinyLLM: Evaluation and Optimization of Small Language Models for Agentic Tasks on Edge Devices. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2511.22138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Model/Module | Manufacturer, City, Country | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| On-board computer | Raspberry Pi 4 Model B (4 GB) | Raspberry Pi Ltd., Cambridge, UK | Handles edge-level control, sensor data acquisition, local safety supervision, and communication with the main LLaVA inference server. |

| Camera | RPi 5 MP with servo mount | Raspberry Pi Ltd., Cambridge, UK | Provides real-time visual input and adjustable viewpoint for scene exploration. |

| Range sensor | HC-SR04 ultrasonic sensor | Yahboom, Shenzhen, China | Measures obstacle distance and triggers safety stop when the threshold is below m. |

| Drive system | 4WD motor driver shield + 4 × DC V 200 rpm motors | Yahboom, Shenzhen, China | Controls differential steering and speed using PWM signals. |

| Displays | 0.96 in OLED + 8 × 16 LED matrix | Yahboom, Shenzhen, China | Displays connection mode, debug data, and system status feedback. |

| Power supply | 2 × 18650 Li-Ion cells + DC–DC regulators | Yahboom, Shenzhen, China | Provides stabilized and isolated voltage for logic and motor subsystems. |

| Parameter | Description/Value |

|---|---|

| Model Type | Multimodal (image + text) |

| Output Format | One sentence (scene description) + structured JSON command |

| Inference Settings | Temperature 0.2, top-p 0.9, context window 4096 |

| Model | Latency [ms] | Valid JSON [%] | Coherence [%] | Safety Events [%] | Smoothness [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLaVA:7B (custom) | 185 ± 12 | 96.2 | 94.5 | 0.0 | 91.8 |

| LLaVA (standard) | 240 ± 18 | 88.7 | 82.1 | 4.5 | 83.4 |

| Llama3 (text-only) | 155 ± 9 | 100.0 | 61.3 | 21.5 | 67.8 |

| Model | Latency Stability | JSON Stability | Safety Stability |

|---|---|---|---|

| LLaVA:7B (custom) | High | High | High |

| LLaVA (standard) | Medium | Medium | High |

| Llama3 (text-only) | High | High | Low |

| Feature | Modular (CNN + Logic) | End-to-End RL | VLM Zero-Shot (Ours) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Training Required | Moderate (Object Det.) | High (Sim2Real) | None (Pre-trained) |

| Semantic Understanding | Low (Class Labels) | None (Black box) | High (Natural Language) |

| Inference Latency | Low (<50 ms) | Very Low (<10 ms) | High (∼200 ms) |

| Explainability | Medium | Low | High (Text Reasoning) |

| Error Type | Description/Example |

|---|---|

| Lighting artefacts | Hallucinated obstacles due to glare or shadows. |

| Overgeneralization | Commands based on incorrect assumptions about free space. |

| Delayed scene update | Reasoning referencing earlier frames in dynamic situations. |

| Ambiguous semantics | Vague or overly cautious descriptions (e.g., “something ahead”). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ewald, D.; Rogowski, F.; Suśniak, M.; Bartkowiak, P.; Blumensztajn, P. Exploring the Cognitive Capabilities of Large Language Models in Autonomous and Swarm Navigation Systems. Electronics 2026, 15, 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010035

Ewald D, Rogowski F, Suśniak M, Bartkowiak P, Blumensztajn P. Exploring the Cognitive Capabilities of Large Language Models in Autonomous and Swarm Navigation Systems. Electronics. 2026; 15(1):35. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010035

Chicago/Turabian StyleEwald, Dawid, Filip Rogowski, Marek Suśniak, Patryk Bartkowiak, and Patryk Blumensztajn. 2026. "Exploring the Cognitive Capabilities of Large Language Models in Autonomous and Swarm Navigation Systems" Electronics 15, no. 1: 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010035

APA StyleEwald, D., Rogowski, F., Suśniak, M., Bartkowiak, P., & Blumensztajn, P. (2026). Exploring the Cognitive Capabilities of Large Language Models in Autonomous and Swarm Navigation Systems. Electronics, 15(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010035