1. Introduction

Stroke, occasionally called brain attack, is rapidly becoming one of the primary causes of death worldwide. According to the World Health Organization, brain stroke is the second most prevalent cause of fatalities and permanent disabilities worldwide. The brain, considered one of the most crucial organs in a person’s body, also has a key cognitive and behavioral function. Compared with the brains of other vertebrates, the cerebral cortex of the human brain is far more advanced. Three primary elements form the human brain (white matter, gray matter, and cerebrospinal fluid) [

1,

2,

3]. As a necessary aspect of the functioning of the human body, the brain is supplied with nutrients and oxygen through constant blood circulation. Brain stroke occurs when the brain’s blood supply is suddenly cut off or severely decreased. Brain stroke can be exceedingly dangerous and potentially results in a wide range of adverse outcomes, including major brain disorders, damage, facial drooping, weakness, long-term or short-term impairment, and even death [

3,

4]. Notably, almost 16 million people worldwide suffer a stroke every year, with 6 million losing their lives and another 6 million permanently disabled. In addition, each year in the United States, approximately 796,000 persons suffer from a stroke, with 650,000 of those being first strokes and 187,000 are recurrent strokes. Stroke is the leading contributor to the overall prevalence of neurological disorders in India, accounting for 37.9% of all cases and 7.4% of all deaths [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9].

Appropriate blood flow is necessary for the proper functioning of both the brain and heart. Strokes can occur because the brain does not receive enough blood or because of a blockage in the blood arteries that supply blood to the brain. Ischemic and hemorrhagic brain strokes are two categories of brain strokes. Ischemic stroke occurs when a clogged artery cuts off oxygen-rich blood into the brain. The presence of clumps in the brain can be categorized as thrombotic or embolic. Hemorrhagic stroke can cause brain bleeding. There are two main types of hemorrhagic brain strokes: subarachnoid and intracerebral. When comparing these two types of stroke, it is clear that ischemic stroke is the leading cause of death. Even though they only account for 10–15% of the total stroke incidence, hemorrhagic strokes are associated with very high mortality and morbidity rates, which have not decreased anywhere in the world over the past 20 years. Mortality is greater than 50 percent, with half of all deaths occurring in the first two days of the illness. Moreover, 3% of people experience subarachnoid hemorrhage, 10% experience intracerebral hemorrhage, and 87% experience ischemic stroke [

2,

8,

10]. Worldwide, 25% of the population over 25 years of age will experience stroke once throughout their lives, as reported by the World Stroke Organization. Every year, over 12 million people experience their first stroke, and over 6 million people lose their lives as a direct result of that stroke. A stroke affects not only the individual who suffers it but also their social circle, household, and place of employment. Numerous scientific investigations have been conducted to identify reliable indicators of stroke. Researchers have identified several risk factors for stroke in the brain, including age, sex, heavy alcohol use, systolic blood pressure, use of antihypertensive therapy, diabetes, smoking, history of cardiovascular disease, atrial fibrillation, left ventricular hypertrophy as measured by electrocardiogram, body weight, diet, and family history. Stroke is becoming more common and deadly, especially in third-world countries [

11,

12,

13,

14].

Stroke has rapidly become the leading cause of mortality and health-related impairments on a global scale. Significant financial consequences can be expected following treatment and for post-stroke care [

8,

15,

16]. Patients can benefit greatly from early diagnosis of brain stroke. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), electroencephalography (EEG), Positron Emission Tomography (PET), ultrasound imaging, and Computed Tomography (CT) are among the most commonly used diagnostic methods for stroke. These methods are widely used because of their high degrees of accuracy. However, concerns remain regarding the safety of these gadgets. For instance, X-ray light in CT scans may directly affect the patient’s body. In addition, many countries have a deficiency in the availability of these tools, or therapy is prohibitively expensive for most people [

2,

17]. Therefore, there is an immediate need for a portable, low-cost, time-saving, and highly accurate method to predict stroke. Early detection and diagnosis are aided by accurate detection of stroke. Stroke detection is complex. Stroke texture, form, and color vary widely, making detection difficult and time consuming [

2,

4]. However, numerous systems have been developed that use Artificial Intelligence (AI), ML, and Deep Learning (DL) to analyze brain activity and predict or identify individual strokes. A unique DL technique using Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) was empirically evaluated in [

18] to identify and categorize intracranial hemorrhage (ICH). The model was built with an AUC of 90.3% for ICH detection. Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) had an exceptionally high accuracy rate of 91.7% in classifying ICH into subtypes.

The purpose of this research [

19] was to evaluate the efficacy of employing support vector machines (SVMs) for the identification and classification of microwave-induced brain strokes. The approach showed that SVM can identify stroke and divide it into ischemic and hemorrhagic types. In a previous study [

2], the Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) was utilized to classify the severity of strokes. The proposed algorithm detected brain strokes with higher accuracy (98.3%). The primary purpose of this research [

13] is to develop a method for assessing an individual’s stroke risk based on their medical history and lifestyle choices. This study used five ML algorithms to analyze patients’ medical records and physical activity to detect and categorize strokes. With an accuracy of 82.1%, the decision tree algorithm was the most successful in predicting strokes based on various physiological parameters. The authors of the paper [

8] reviewed 177 articles published between 2010 and 2021 to assess the current state and obstacles of computer-aided diagnosis (CAD), ML, and DL methods that use CT and MRI as primary procedures for stroke identify and region segmentation.

The research paper [

7] presented a lightweight microwave head imaging system that utilizes a tiny 3D antenna with MTM technology. The system consists of an array of nine antennas, a head phantom that simulates tissue, a power network analyzer, and a computational device that gathers and stores dispersed data for later processing. Additionally, an MTM-loaded compact 3D antenna covering the frequency range of 1.95 to 4.5 GHz with 80% fractional bandwidth is described in this work for a portable microwave head imaging system. In work [

20], a hybrid threshold-based picture categorization and segmentation model was constructed to predict strokes. The approach presented herein employs a combination of a robust decision tree classifier and a feature selection algorithm to isolate the most relevant characteristics for stroke forecasting. The experimental results demonstrated that the existing model attained an accuracy of 98.23%. Using five different ML algorithms, ref. [

3] developed a system with an accuracy of up to 98.56% for predicting brain strokes. The primary goal of this study was to demonstrate that a combination of boosting techniques, ML algorithms, and ANNs can be used to predict the onset of stroke in the brain. Stroke Prediction Ensemble (SPE) is a framework described in [

21] that combines feature engineering and ensemble classification to provide stroke predictions. Empirical research has shown that the ensemble model has the highest accuracy of approximately 97.93%.

In the recent years, wearable devices have become the most preferable option in many healthcare monitoring and rehabilitation applications because they can provide continuous observation, are easy to access, and can be adapted to different clinical needs. Building on these advances, sensor-based platforms are now being developed to support stroke survivors along the full rehabilitation pathway, from hospital to home. For example, Zhang et al. proposed robust vital-sign monitoring using mmWave sensing with multi-point reflection modeling, which improves reliability under small body motions and challenging environments [

22]. In addition, Ni et al. introduced REHSense, a battery-free wireless sensing approach that leverages RF energy harvesting to enable sensing with extremely low power consumption [

23]. Compared to these methods, our prototype focuses on a practical BLE-based IoT stack (temperature and

sensors + smartphone fusion) that is easy to deploy with commercially available devices. In future work, we plan to investigate hybrid designs that incorporate contactless mmWave sensing and/or RF-energy-harvesting sensors to further improve user comfort and energy efficiency. Spinelli et al. introduced a user-centered wearable sleeve that integrates electromyography smart sensors, functional electrical stimulation, and virtual reality in a closed-loop system, enabling intensive, personalized upper-limb stroke rehabilitation and remote progress monitoring [

24]. Using DL, a CNN model was created to identify heart arrhythmia and forecast sudden stroke. The proposed classifier outperformed existing methods with an accuracy of 99.3%. The development of a monitoring system for stroke identification and prediction utilizing IoT and fog computing technologies was presented in this study [

25]. The monitoring system comprises three layers: the patient information layer, the cloud layer, and the fog computing gateway layer. The proposed system utilizes an ensemble classifier that combines random forest and boosting techniques. The monitoring system was evaluated using the accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity parameters. The simulation results indicated an accuracy of 93.64%. Stroke can be detected by recognizing abnormal gait patterns, and this research [

26] proposed a smartphone and hybrid classification algorithm-based technique to detect irregular gait patterns in a stroke patient at the initial stage. Accelerometer and gyroscope data from the smartphone sensors were used to build the models. The obtained data were processed using min-max normalization, and acceptable characteristics were chosen to develop a model utilizing hybrid classification approaches (Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), Decision tree (DT), and SVM) according to the majority voting technique. The study showed 99.40% accuracy for aberrant gait pattern detection in the early stages of stroke. The authors of this article [

27] discussed the process of developing an

monitoring device, which was initially utilized for detecting stroke in a patient. This system monitors and compares

values from the right and left arms simultaneously. If the percentage of

fell below 60%, the buzzer of this system would sound off as an alert.

In study [

28], the authors reviewed over 100 research articles to investigate the trends and challenges associated with wearable multi-modal technologies for predicting stroke risk. They presented many wearable technologies currently available to predict the risk of developing stroke, and contrasted the various properties of these wearables. Researchers discovered that wearable with high user-friendliness may have limitations in providing precise prediction outcomes. The authors of the study [

29] surveyed various portable, non-invasive diagnostic methods to simplify triage through the initial assessment of stroke type. After assessing 296 studies, 16 were selected for inclusion. Different diagnostic technologies, such as near-infrared spectroscopy (6), electroencephalography (4), ultrasound (4), volumetric impedance spectroscopy (1), and microwave technology (1), have been utilized by the devices studied. The median measurement time was 3 min (interquartile range [IQR], 3–5.6 min). They identified many technologies that accurately diagnose severe stroke and cerebral hematoma. The article [

30] examined the cost-effectiveness of additional short-protocol brain MRI following negative non-contrast CT for screening minor strokes in patients in emergency conditions with moderate and unclear neurological symptoms. This study demonstrated that performing an additional emergency brain MRI using a short protocol, following a negative non-contrast head CT, is a cost-effective solution for certain neurological patients with mild and nonspecific symptoms. This strategy reduces costs and increases quality-adjusted life-years (QUALYs).

A novel architecture for a mobile AI smart hospital framework was proposed in the study [

31] to improve stroke prediction and response time in emergencies. XAI architecture-based integrated AI software modules were developed and tested in this research. The main purpose of this work was to predict the occurrence of heart disease and stroke. The proposed techniques exhibited high accuracy, with the stacked CNN achieving nearly 98% accuracy in stroke diagnosis. The research [

32] aimed to detect early-stage strokes utilizing big data and bio-signal analysis technology and contribute to human health improvement. Experimental tests were conducted to assess the sensitivity of a stroke-detection system developed for elderly adults. The health symptoms and motion data of 80 stroke victims and 50 normal elderly individuals were recorded. The bio-signal data from the experiment were extracted, and a judgment model was built by combining the data from the participant’s 10-year health examination. Study [

33] aims to predict early brain strokes using DL and ML. XGBoost, Ada Boost, Light Gradient Boosting Machine, Random Forest (RF), DT, Logistic Regression (LR), K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), SVM-Linear Kernel, Naive Bayes (NB), and deep neural networks (3-layer and 4-layer ANN) classification models were used here. The RF classifier had the highest ML classification accuracy at 99%. The 4-Layer ANN method had a 92.39% accuracy compared to the 3-Layer ANN method using the selected features and found that ML techniques beat out deep neural networks. The work [

34] utilized the rapid response of EEG data to cerebral ischemia and clinical indicators to propose a “clinical indications + quantifiable electroencephalogram” multi-feature pattern recognition method. Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) attention and multi-feature were used to diagnose ischemic stroke. Using the data of 500 ischemic stroke patients, the diagnostic model obtained 0.81 accuracy, 0.82 sensitivity, and 0.81 F1-score. DICE coefficient of 0.91, precision of 0.94, and sensitivity of 0.89 were the training set evaluation indicators of their cascaded 3D deep residual network stroke precise segmentation algorithm.

Moreover, the above discussion shows that federated learning can fit very well with IoT-based smart healthcare systems. Abbas et al. [

35] present a comprehensive review of FL in healthcare, with a strong focus on how FL can work together with IoT devices, wearables, and remote monitoring platforms for predictive analytics and personalized care. They highlight key privacy, security, and interoperability issues and discuss solutions such as secure aggregation and differential privacy. However, this study stays at a high, system-level view and does not design or implement a concrete, real-time embedded stroke monitoring pipeline that combines FL with lightweight feature-optimized models on resource-constrained devices. At the algorithm level, Wang et al. [

36] propose a privacy-preserving FL framework for the Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) under edge computing. Their PPFLEC scheme protects gradient updates using a secret-sharing–based masking protocol and adds digital signatures to ensure integrity and defend against replay and collusion attacks. The framework is designed to work in unstable edge environments and keeps model accuracy comparable to standard FL while improving privacy and robustness. Yet, this work mainly focuses on secure communication and aggregation; it does not consider application-specific designs such as stroke risk scoring, feature selection on tabular clinical data, or the integration with a real-time IoT stroke monitoring device. Aminifar et al. [

37] present a privacy-preserving edge FL framework aimed at mobile health and wearable devices in IoT settings. They address strict resource limits (CPU, memory, and battery) and show that edge FL can support intelligent health monitoring, demonstrated on seizure detection using wearable sensors. Their work proves that FL can be pushed close to the data source, reducing latency and keeping sensitive data on devices. However, the study focuses on epilepsy and generic mobile-health pipelines; it does not target stroke, does not use structured stroke risk features like those in the Kaggle stroke dataset, and does not describe an embedded IoT gateway that combines optimized feature selection with real-time risk codes as in our system. For stroke specifically, Elhanashi et al. [

38] introduce TeleStroke, a real-time stroke detection system based on YOLOv8 and federated learning on edge devices. Their model detects stroke versus non-stroke cases from facial images that capture signs such as facial paralysis and is deployed on NVIDIA edge platforms to meet real-time constraints. FL is used to train across distributed clients while keeping patient images local, which improves privacy and model robustness. Yet, this work focuses on vision-only stroke detection with a heavy deep model and GPU hardware; it does not use low-cost IoT physiological sensors, does not combine clinical risk factors with vital signs, and does not explore lightweight, feature-optimized ML models suitable for embedded microcontroller-based monitoring as in our proposed framework.

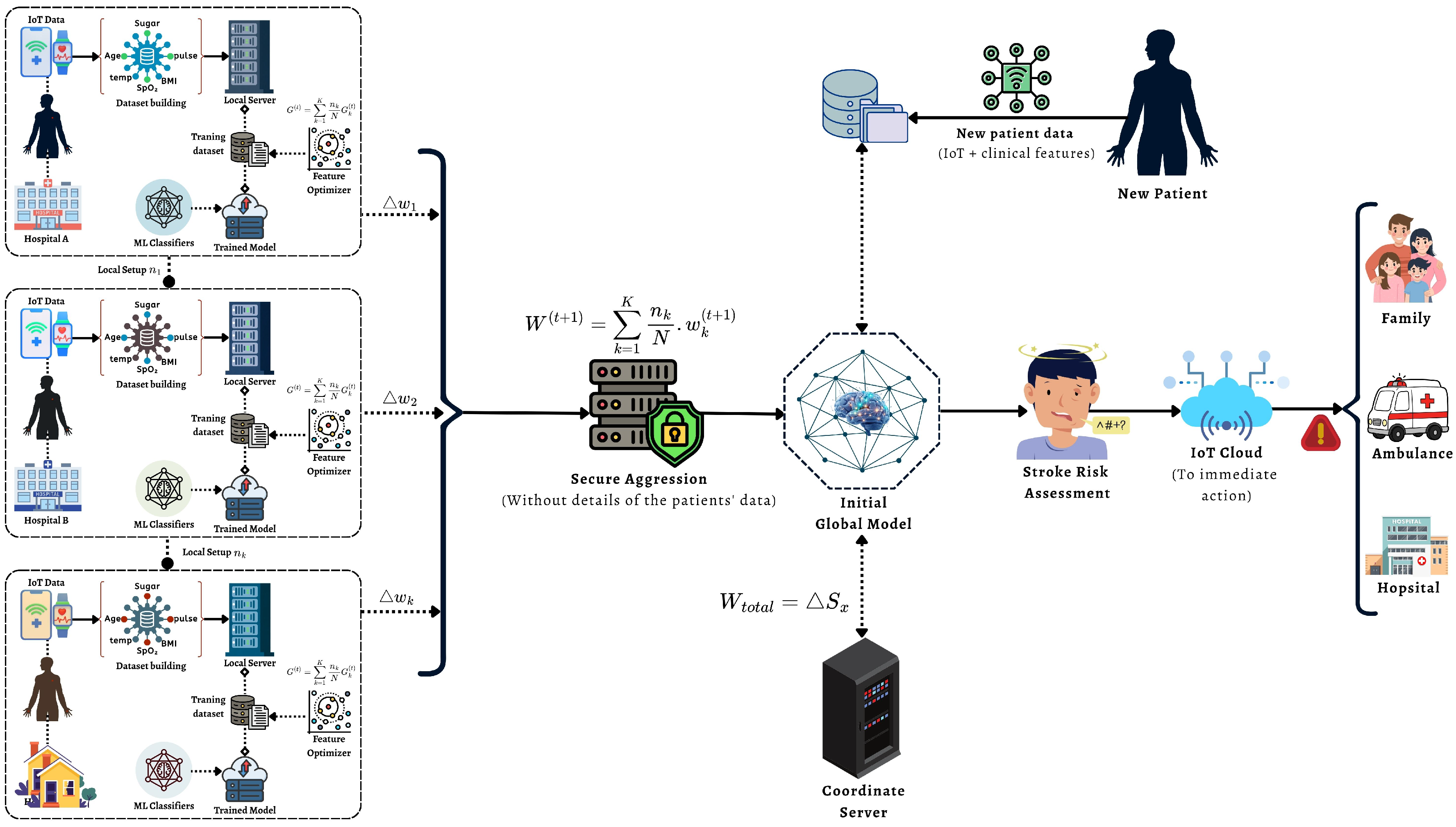

Although FL, ML, and IoT have been studied individually in healthcare, this work focuses on their joint integration for stroke-risk monitoring, where (i) FL builds a global model without centralizing raw data, (ii) feature optimization is evaluated within the FL pipeline to improve stability, and (iii) an IoT workflow applies the global model for real-time screening and alerting. This end-to-end design targets the practical gap between privacy-preserving model training and continuous patient monitoring in resource-limited settings. The main contribution of the proposed approach is described below:

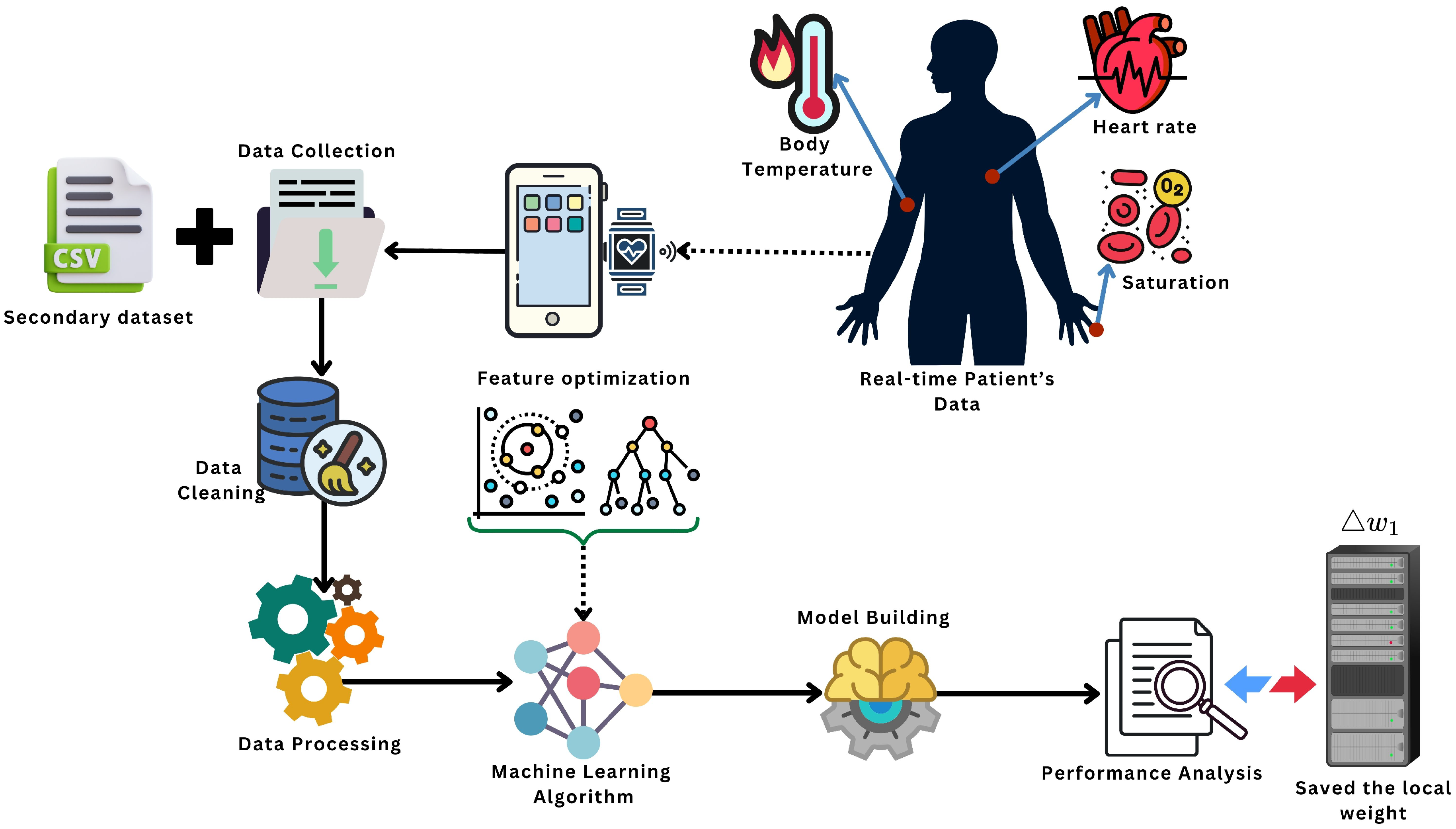

This paper presents an end-to-end stroke-risk framework that integrates federated learning (FL), machine learning (ML), and an IoT monitoring workflow to support early stroke risk screening while keeping data privacy in mind.

We design a federated training setup where client-side data remain local and only model parameters are exchanged, enabling multi-source learning without centralizing raw patient records.

We evaluate a feature optimization pipeline (feature importance, selection, and reduction) to identify the most informative stroke-related factors and to improve model stability across different classifiers.

We implement a round-based FedAvg training protocol in which clients train locally for E epochs and the server aggregates parameters over T communication rounds to obtain a global stroke-risk predictor.

We describe an IoT-assisted monitoring and alert workflow where physiological signals (e.g., temperature asymmetry and ) support real-time tracking and can trigger warnings to caregivers or emergency services when high risk is detected.

The manuscript is divided into five individual sections.

Section 2 details the proposed approach’s architecture and fundamental principles. In

Section 3, the outcomes are presented alongside an appropriate rationale. Finally,

Section 4 presents the conclusion of the manuscript along with the existing drawbacks and a summary of the future directions.

3. Results and Discussion

The result analysis of the proposed framework and the discussion are given in this section. The

Section 3.1 has the data analysis with ML algorithms, and the

Section 3.2 has the proposed IoT-based monitoring system’s data analysis for predicting and detecting brain stroke. Lastly, a short comparison and discussion of the previous works are given.

3.1. Results Analysis with ML-Based Architecture

A result analysis utilizing ML architectures for predicting brain strokes is provided in this section. All experiments were carried out on a desktop workstation with the following configuration. The system was equipped with an Intel 12th Gen Core i7–12700KF processor running at 3.60 GHz and 32 GB of RAM (31.8 GB usable). A dedicated NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3080 GPU with 10 GB of video memory was used to accelerate the training and evaluation of the machine learning models. The machine had a 64-bit operating system on an x64-based processor and a total storage capacity of 932 GB, of which only 143 GB was used. This configuration provided enough CPU power, GPU memory, and disk space to handle the datasets, model checkpoints, and repeated experiments required in this study without noticeable hardware bottlenecks.

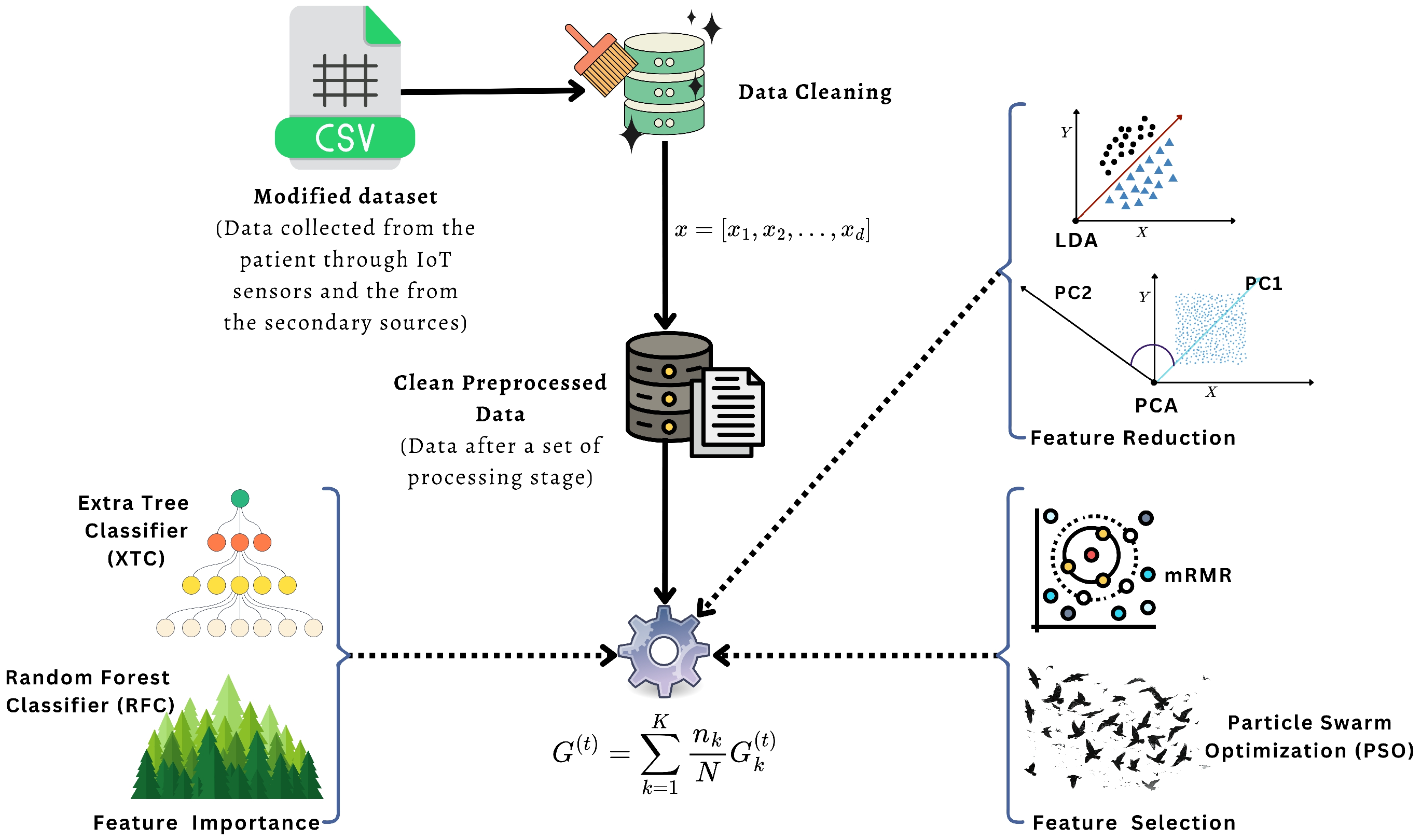

For feature optimization, we used six methods. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) reduced the feature space by keeping of the total variance (n_components = 0.95) with a fixed random seed (random_state = 42). Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) projected the data into at most components, where C is the number of classes (n_components = ). For Random Forest based selection (RFC) and Extra Trees based selection (XTC), we trained tree ensembles with n_estimators = 200, random_state = 42, and n_jobs = −1, and then kept only the features whose importance was above the median using SelectFromModel(threshold = “median”). The mRMR-style filter computed mutual information with random_state = 42 and selected the top-k features, where and d is the original number of features. Finally, the PSO-based selector used a Binary Particle Swarm Optimizer with n_particles = 20 and iters = 30. Its cost function combined classification error and feature ratio, with weights and . The optimizer options were c1 = 2.0, c2 = 2.0, w = 0.9, k = 5, and p = 2. The cost was evaluated using 3-fold cross-validation (cv = 3, scoring = “accuracy”) of a logistic regression base model with max_iter = 500 and random_state = 42.

For classification, we used six models and ignored logistic regression as a final classifier. The Support Vector Machine (SVM) used a radial basis function kernel (kernel = “rbf”) with probability estimates enabled (probability = True) and random_state = 42. The k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) classifier used n_neighbors = 5. The Gaussian Naive Bayes (NB) classifier used the default scikit-learn settings without extra-tuned hyperparameters. The Decision Tree (DT) classifier used random_state = 42 with default depth and splitting rules. The Random Forest (RF) classifier used an ensemble of n_estimators = 200 trees with random_state = 42 and n_jobs = −1 for parallel training. The XGBoost (XGB) model used n_estimators = 200, max_depth = 4, learning_rate = 0.1, subsample = 0.8, colsample_bytree = 0.8, and a binary logistic objective (objective = “binary:logistic”, eval_metric = “logloss”) with random_state = 42 and n_jobs = −1. All other hyperparameters for these classifiers were kept at their default values.

On the other hand, the Federated Learning (FL) evaluation was conducted as a controlled local simulation, where the training data are partitioned into clients using stratified splits and the server-side aggregation is executed in a centralized environment. Although this setting is useful for comparing FL and centralized training under identical conditions, it does not fully capture real-world FL deployments, where client data are often heterogeneous (non-IID), devices may have limited compute and memory, and training may be impacted by unreliable connectivity, client dropouts, and communication delays. Therefore, the reported FL results should be interpreted as a simulated benchmark; in future work, we will extend the evaluation using non-IID client partitions and communication-aware settings.

In our implementation, we set

and formed client datasets using

StratifiedKFold(n_splits=10, shuffle=True, random_state=42) to preserve the original class distribution across clients. We adopted the standard Federated Averaging (FedAvg) protocol: in each communication round

t, the server broadcasts the current global model parameters

to the selected clients, each client performs local training for

E epochs on its private data, and the server aggregates the updated client parameters to obtain

using weighted averaging proportional to client sample sizes.

Table 4 summarizes the FL hyperparameters used in our experiments. We set

,

,

, optimizer

Adam, and client fraction

.

To assess the efficacy of the proposed model, we utilized these performance evaluation metrics to assess the proposed models under different feature optimization and federated learning setups. Together, they capture overall correctness (Accuracy), the quality of positive predictions (Precision and Recall), and the balanced performance of the classifiers, even in the presence of class imbalance (F1-score and MCC). Let,

,

,

, and

denote true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives, respectively. The performance metrics are defined as:

Table 5 summarizes how many features are selected by each feature optimization method and lists the corresponding feature names. The results show that mRMR keeps a very compact subset, PSO and PCA keep 16 dimensions each (original and reduced), while LDA does not return an explicit feature subset in this setup. On other hand,

Table 6 illustrates the test performance of six classifiers combined with six feature optimization techniques under a global federated learning setup with 10 clients. All configurations reach accuracy above 82%, while PSO-, PCA-, and LDA-based models show very strong results, with several combinations (for example PSO+XGB and PCA+SVM) achieving close to perfect performance across all evaluation metrics. Also,

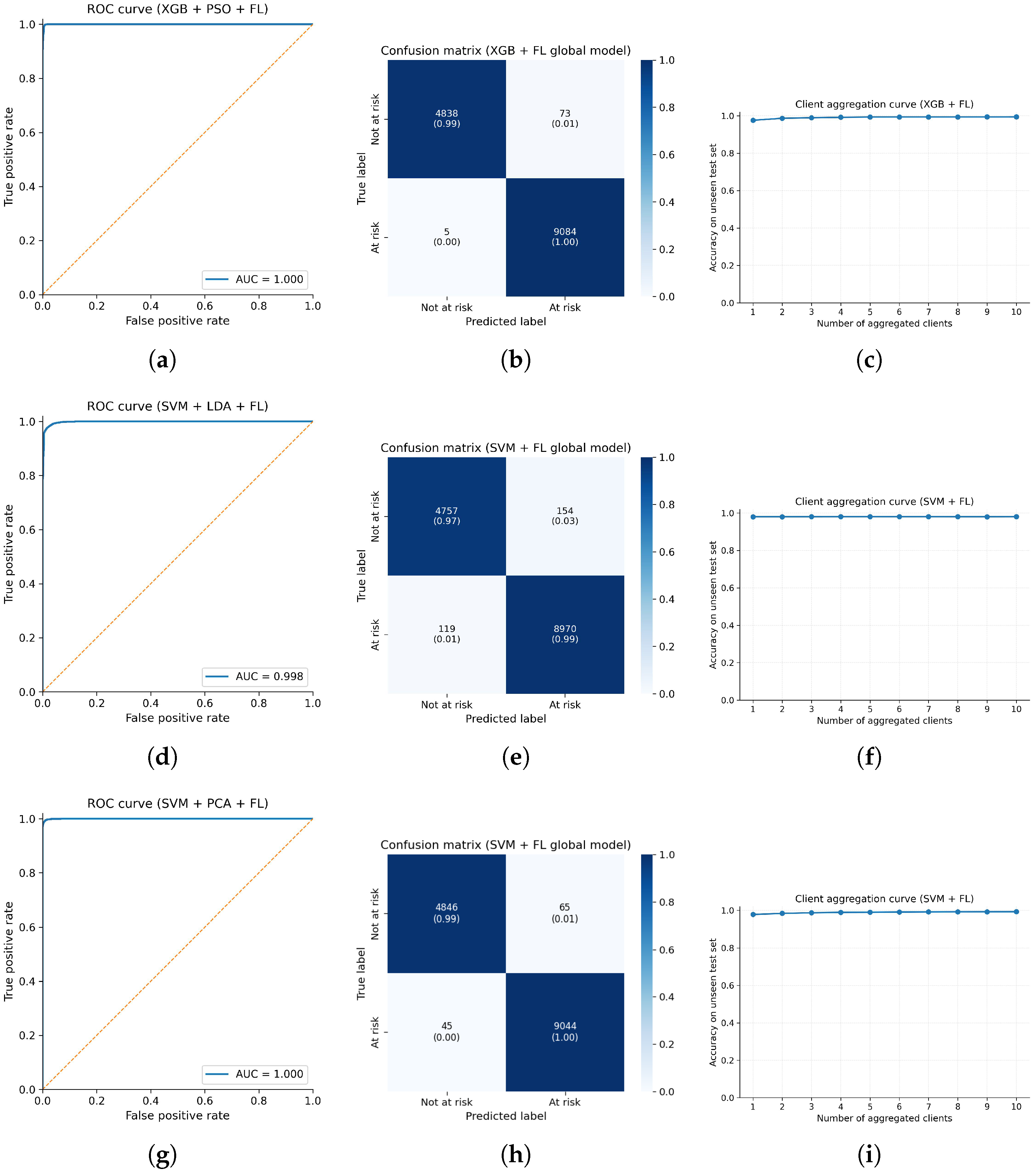

Table 7 shows the summary of the performed model in terms of time and space complexity. Besides, we report the top model for each feature optimization technique based on test accuracy, illustrated in

Figure 6. In this figure, the PSO + XGB + Global FL configuration achieves the best overall performance and therefore is assigned the highest time and space complexity, while the other models have slightly lower but still competitive computational requirements. In

Figure 7, a bar chart of the best-performing federated learning models across accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and MCC is depicted in order to present which combination of the techniques is most suitable for early stroke detection in this proposed scheme.

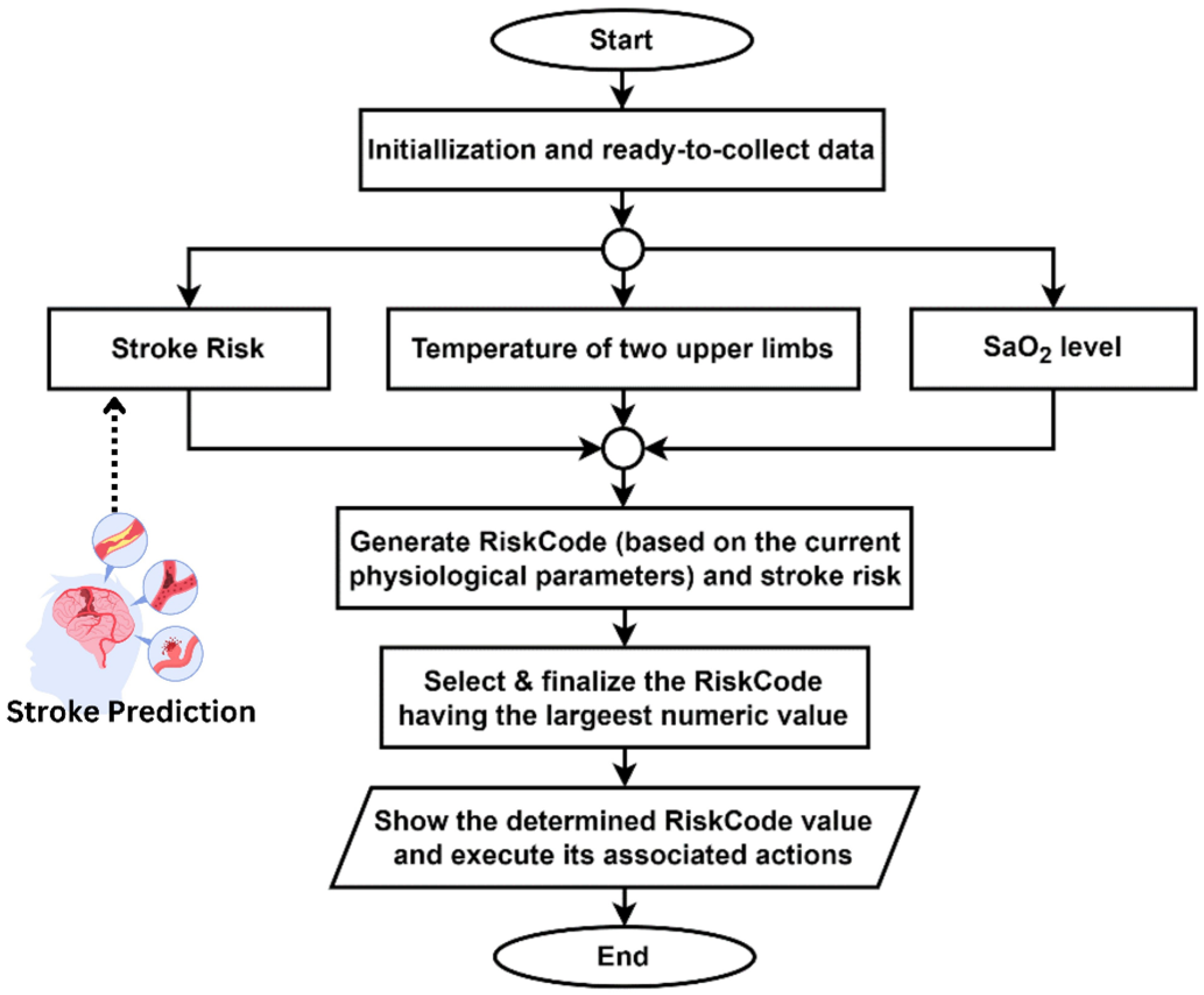

3.2. Experimental Data Analysis with IoT Embedded Orientation

The proposed IoT framework includes a scheme designed to evaluate a patient’s condition regarding stroke risk by utilizing real-time data from IoT sensors. The system takes the temperature data from two upper limbs and compares the temperature difference. Besides, it also takes SaO

2-level data using an oxygen meter. All the data is sent and stored through the smartphone app. Finally, the algorithm returns an output called RiskCode (RC). The term RiskCode (RC) used in

Table 3 is an algorithm-generated output. Depending on the stroke risk for a person predicted by the proposed ML-based architecture, it returns different RiskCodes for different physiological attribute ranges measured by IoT devices. Each RiskCode has its meaning, and the system takes different types of actions based on each RiskCode. Interpretations of these RiskCodes and their system actions are shown in

Table 2. The proposed algorithm is tested in multiple scenarios, showing expected results in every test case. The result data analysis of this test has shown in

Table 8. The algorithm is designed to always select the highest RiskCode value.

3.3. Discussion

This section describes a comparison between the proposed system and previous work, as illustrated in

Table 9. The related work shows that traditional ML, DL, and IoT-based systems have already achieved strong performance for stroke prediction and monitoring, with several approaches reporting accuracies above 95% [

2,

3,

13,

18,

20,

21]. However, most of these models are trained in a centralized way and require direct access to all patient data, which limits their applicability in real-world hospitals and home-care units where privacy and data-sharing rules are strict. In addition, only a few studies explicitly use feature optimization to reduce redundancy in tabular stroke-risk features, and even fewer combine such optimized models with IoT-based real-time monitoring.

Recently, federated learning has emerged as a natural fit for privacy-preserving healthcare applications. Abbas et al. [

35] provide a broad survey of FL in healthcare and describe how it can be integrated with IoT devices, wearables, and remote monitoring platforms. Their work highlights important system-level challenges (such as security, interoperability, and communication cost) but does not implement a concrete stroke-specific model or an embedded IoT monitoring pipeline. Wang et al. [

34] propose PPFLEC, a privacy-preserving FL framework for the Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) under edge computing. Their method focuses on secure aggregation and integrity protection of model updates and shows that FL can maintain accuracy close to centralized training, but it does not address stroke risk scoring or feature-optimized models on resource-limited devices. Aminifar et al. [

37] demonstrate that edge FL can run on mobile and wearable devices for seizure detection and general mobile-health monitoring, again emphasizing resource constraints and privacy but not targeting stroke or using structured symptom-based stroke datasets. For stroke specifically, Elhanashi et al. [

38] present TeleStroke, a federated YOLOv8-based system that detects stroke versus non-stroke cases from facial images on NVIDIA edge devices. TeleStroke confirms that FL can support real-time stroke detection at the edge, yet it uses a heavy vision model, focuses on facial paralysis cues only, and does not integrate low-cost physiological sensors or tabular risk features.

Compared with the above FL-based frameworks, the proposed work targets a different and complementary setting: tabular stroke-risk features combined with wearable physiological signals in an IoT environment. Our system uses the Kaggle stroke-risk dataset enriched with IoT sensor readings (temperature asymmetry and levels) and applies a feature-optimization block that includes RFC/XTC-based feature importance, mRMR and PSO-based feature selection, and PCA/LDA feature reduction. These optimized features are then used to train lightweight ML classifiers at each client, and a global stroke-risk model is obtained using the FedAvg aggregation rule in a federated setup. In this way, raw patient data never leave the local sites, yet the global model benefits from multi-site diversity.

From the experimental results, the PSO + XGB + FL pipeline achieves up to

99.44% accuracy, with AUC values close to 1.0, and other optimized pipelines such as PCA + SVM + FL and LDA + SVM + FL also reach accuracy above 98%. These results outperform previous centralized ML and DL methods on similar stroke datasets [

2,

3,

13,

18,

20,

21] while offering strong privacy guarantees through FL. At the same time, the client aggregation curves show that the global performance improves as more clients participate, indicating that the federated model is robust and scales well across distributed IoT environments. Unlike TeleStroke [

38], which requires GPU-based edge nodes and processes images only, our framework is designed for low-cost microcontroller-based devices, making it more suitable for resource-constrained settings.

Table 9 summarizes the key differences between the existing FL-based healthcare systems and the proposed federated stroke monitoring framework.