An Improved Adaptive NSGA-II with Multiple Filtering for High-Dimensional Feature Selection

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- A population sparse initialization method, in conjunction with multiple filter techniques, is proposed to guide the initial solutions toward the optimal Pareto front, thereby accelerating algorithm convergence and reducing the iteration count.

- (2)

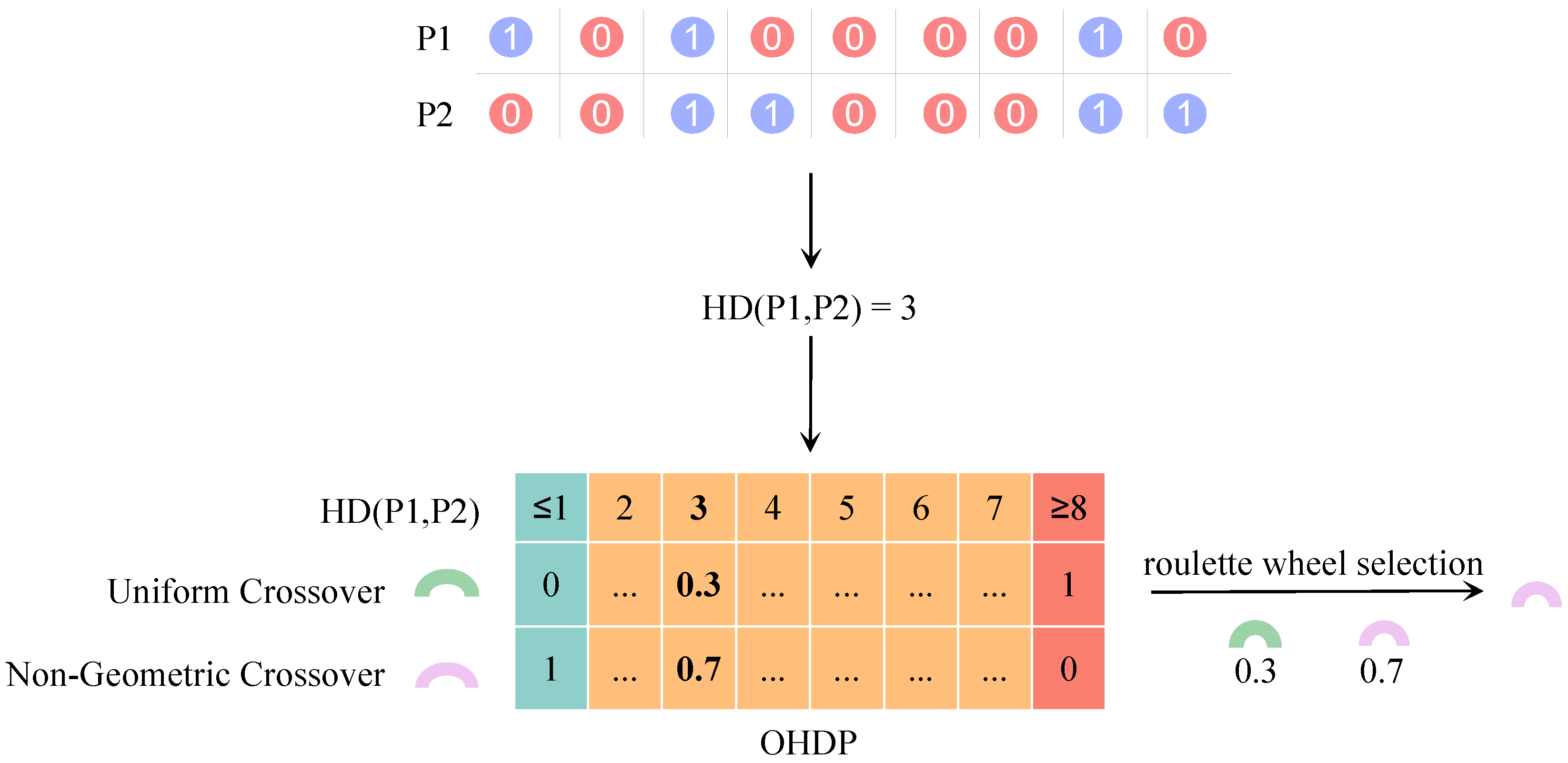

- An adaptive crossover mechanism is designed based on the similarities of parent individuals to ensure both the spread of solutions and the approach towards the optimal solution during the evolution process.

2. Related Work

2.1. MO Optimization Definition

2.2. Filtering Methods

2.2.1. ReliefF

2.2.2. Variable Association

2.2.3. Fisher Score

2.3. Geometric Crossover and Non-Geometric Crossover

2.4. Literature Review

3. Proposed Method

3.1. Framework of AF-NSGA-II

| Algorithm 1 Framework of AF-NSGA-II. |

|

| Algorithm 2 Get Feature Weights (). |

|

| Algorithm 3 Initialization(D, N, ). |

|

| Algorithm 4 AdaptiveCrossover(P). |

|

| Algorithm 5 Mutation(O, ). |

|

3.2. Computational Complexity Analysis

3.3. Objective Functions

3.4. Sparse Initialization Referring to Feature Weights

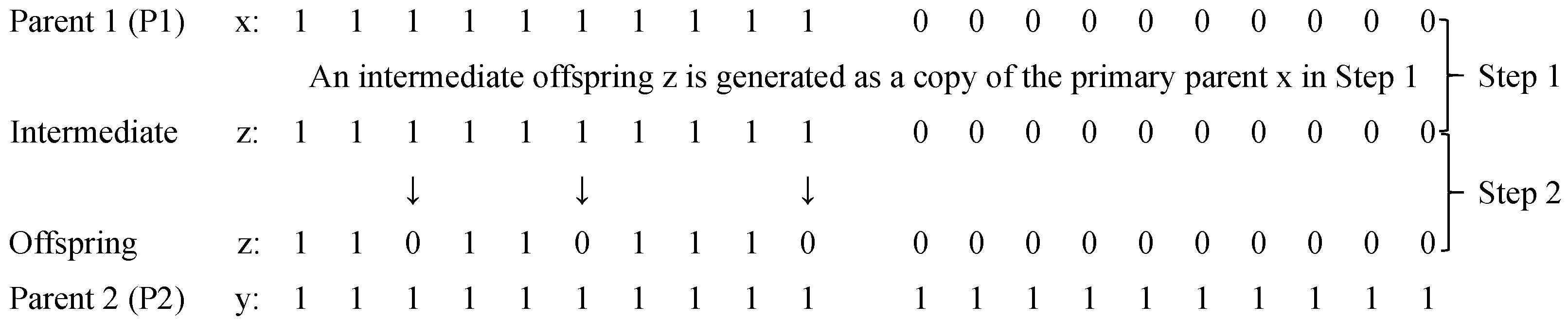

3.5. Adaptive Crossover Based on Parental Similarities

3.6. Mutation

4. Experimental Setup and Evaluation Criteria

4.1. Classifier and Datasets

4.2. Comparing Algorithms and Parameter Configurations

4.3. Performance Indicators

5. Experimental Evaluation

5.1. Quantitative Performance Evaluation

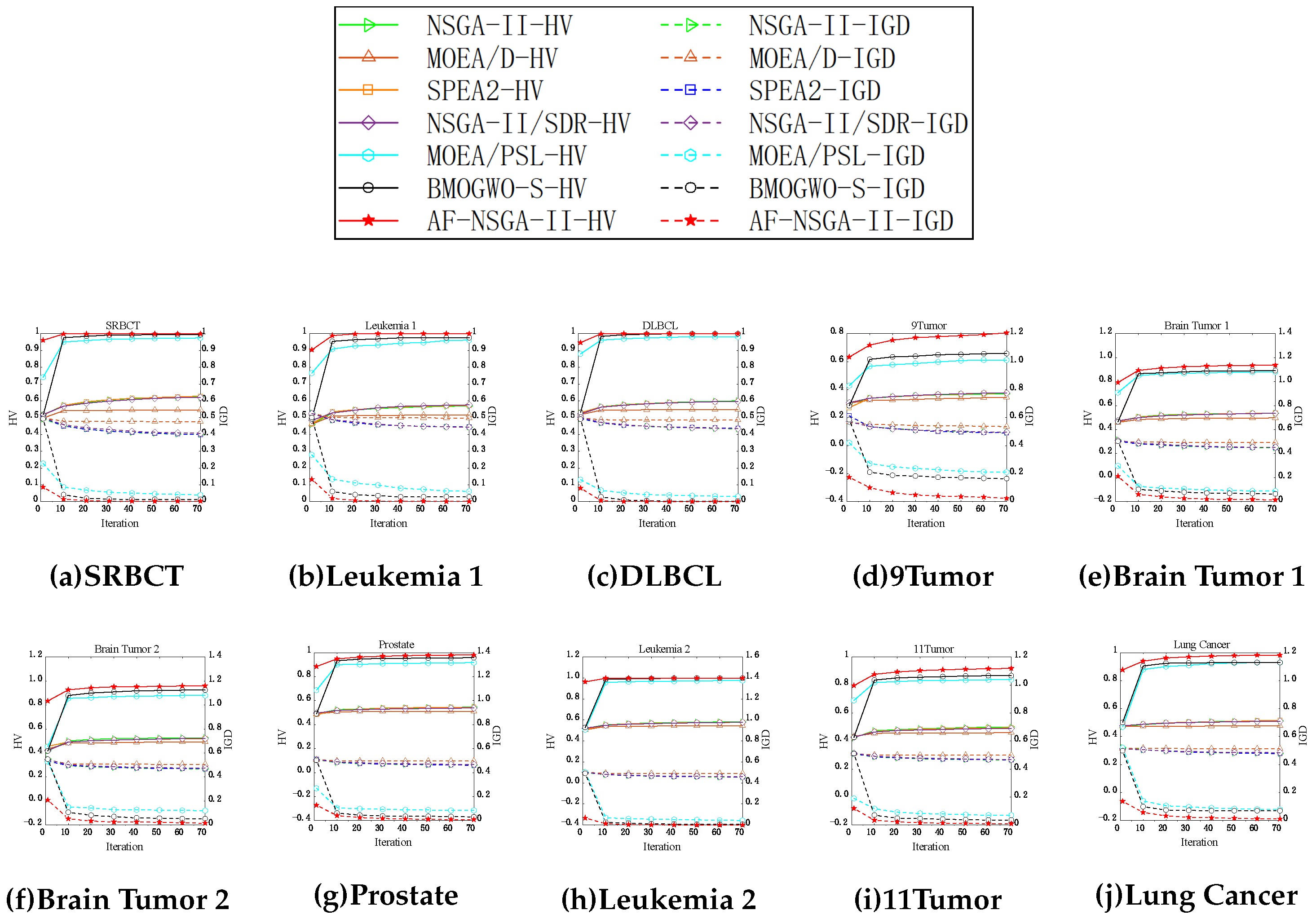

5.2. Assessment of Convergence Performance

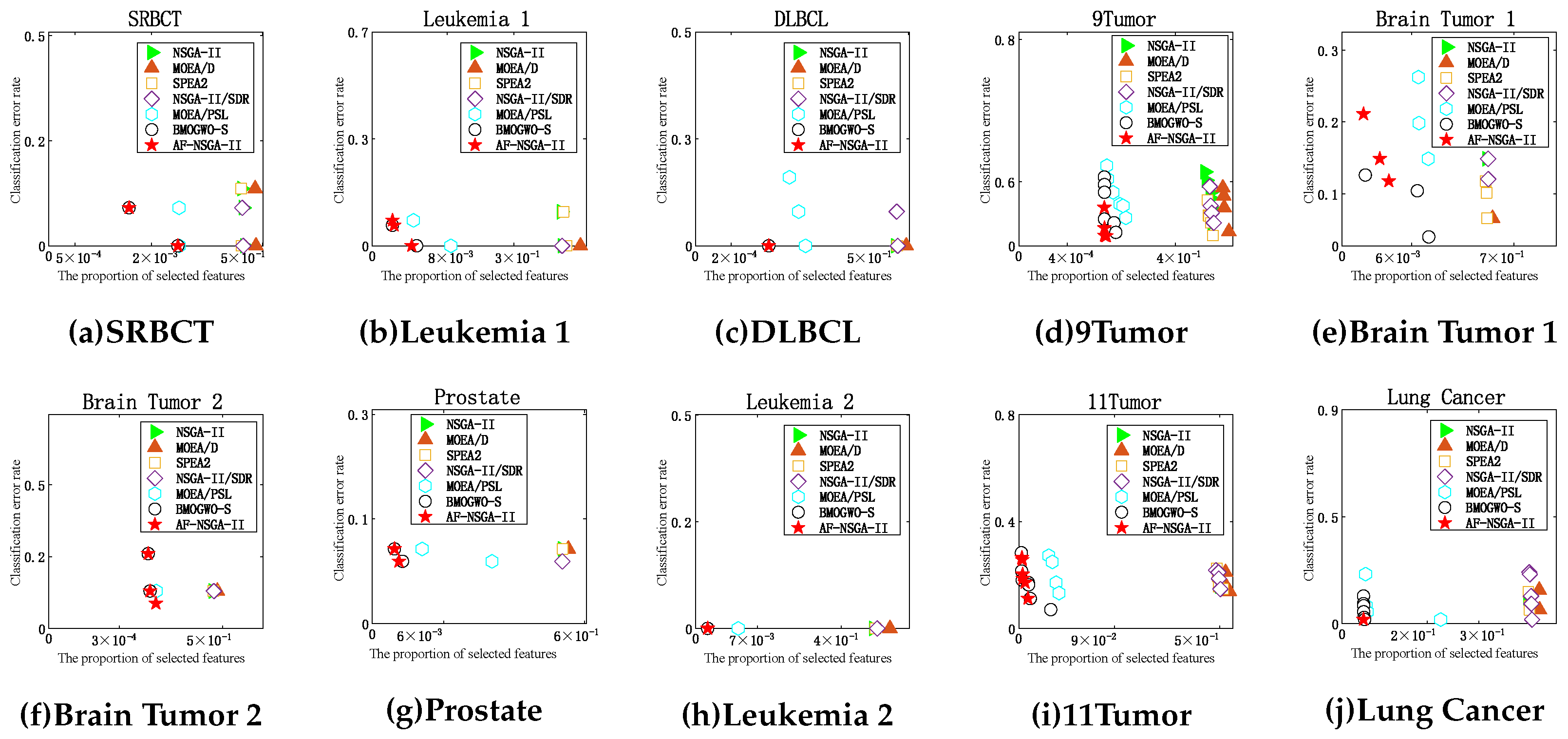

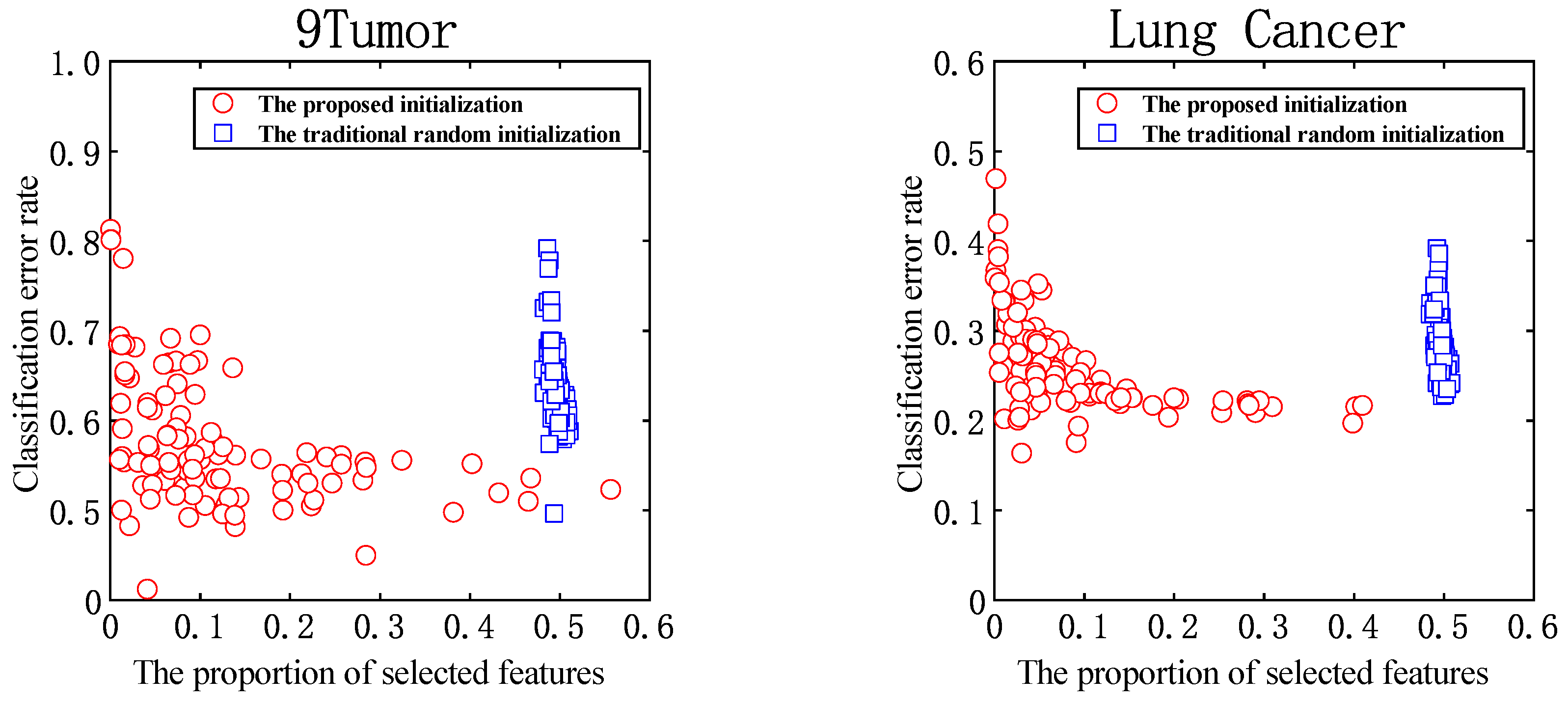

5.3. Analysis of Pareto Front

5.4. Ablation Study

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xue, Y.; Zhu, H.; Neri, F. A feature selection approach based on NSGA-II with ReliefF. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 134, 109987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.; Jiang, M.; Yen, G.G. Boosting scalability for large-scale multiobjective optimization via transfer weights. Inf. Sci. 2024, 670, 120607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, B.; Xue, B.; Zhang, M. Variable-length particle swarm optimization for feature selection on high-dimensional classification. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2018, 23, 473–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, C.T.; Liang, J.J.; Qu, B.Y.; Yu, K.J.; Song, H. Multimodal Multiobjective Optimization in Feature Selection. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC), Wellington, New Zealand, 10–13 June 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.P.; Wang, K.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, J.; Zhu, Z. Sparse large-scale multiobjective optimization based on evolutionary multitasking. Chin. J. Comput. 2025, 48, 358–380. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gong, D.W.; Gao, X.Z.; Tian, T.; Sun, X.Y. Binary differential evolution with self-learning for multi-objective feature selection. Inf. Sci. 2020, 507, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, B.; Zhang, M.; Browne, W.N. Particle swarm optimization for feature selection in classification: A multi-objective approach. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2012, 43, 1656–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Fu, Q.; Li, Q.; Ding, W.; Lin, F.; Zheng, Z. Multi-objective binary grey wolf optimization for feature selection based on guided mutation strategy. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 145, 110558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Gao, S.; Zhou, M.; Sato, S.; Cheng, J.; Wang, J. Information-Theory-based Nondominated Sorting Ant Colony Optimization for Multiobjective Feature Selection in Classification. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2023, 53, 5276–5289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.H.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, X.Y.; Wang, Y.L.; Du, C.H. Multi-objective feature selection based on artificial bee colony: An acceleration approach with variable sample size. Appl. Soft Comput. 2020, 88, 106041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Cai, X.; Neri, F. A multi-objective evolutionary algorithm with interval based initialization and self-adaptive crossover operator for large-scale feature selection in classification. Appl. Soft Comput. 2022, 127, 109420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labani, M.; Moradi, P.; Jalili, M. A multi-objective genetic algorithm for text feature selection using the relative discriminative criterion. Expert Syst. Appl. 2020, 149, 113276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purshouse, R.C.; Fleming, P.J. On the evolutionary optimization of many conflicting objectives. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2007, 11, 770–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Li, W.; Cai, X.; Li, H.; Wei, C.; Zhang, Q.; Deb, K.; Goodman, E. Push and pull search for solving constrained multi-objective optimization problems. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2019, 44, 665–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Q.; Guo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Du, C.; Liu, X. Optimization study of energy saving control strategy of carbon dioxide heat pump water heater system under the perspective of energy storage. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 283, 129030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robnik-Šikonja, M.; Kononenko, I. Theoretical and empirical analysis of ReliefF and RReliefF. Mach. Learn. 2003, 53, 23–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reshef, D.N.; Reshef, Y.A.; Finucane, H.K.; Grossman, S.R.; McVean, G.; Turnbaugh, P.J.; Lander, E.S.; Mitzenmacher, M.; Sabeti, P.C. Detecting novel associations in large data sets. Science 2011, 334, 1518–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Wang, T.; Ding, W.; Xu, J.; Lin, Y. Feature selection using Fisher score and multilabel neighborhood rough sets for multilabel classification. Inf. Sci. 2021, 578, 887–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraglio, A.; Poli, R. Topological Interpretation of Crossover. In Genetic and Evolutionary Computation—GECCO, Proceedings of the Genetic and Evolutionary Computation Conference, Seattle, DC, USA, 26–27 June 2004; Deb, K., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; pp. 1377–1388. [Google Scholar]

- Moraglio, A.; Poli, R. Product Geometric Crossover. In Parallel Problem Solving from Nature—PPSN IX, Proceedings of the International Conference on Parallel Problem Solving from Nature, Reykjavik, Iceland, 9–13 September 2006; Runarsson, T.P., Beyer, H.G., Burke, E., Merelo-Guervós, J.J., Whitley, L.D., Yao, X., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 1018–1027. [Google Scholar]

- Ishibuchi, H.; Tsukamoto, N.; Nojima, Y. Diversity improvement by non-geometric binary crossover in evolutionary multiobjective optimization. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2010, 14, 985–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraglio, A.; Poli, R. Inbreeding Properties of Geometric Crossover and Non-geometric Recombinations. In Foundations of Genetic Algorithms, Proceedings of the International Workshop on Foundations of Genetic Algorithms, Mexico City, Mexico, 8–11 January 2007; Stephens, C.R., Toussaint, M., Whitley, D., Stadler, P.F., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, H.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, S.; Liu, T.; Shan, Y. A comprehensive survey on NSGA-II for multi-objective optimization and applications. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2023, 56, 15217–15270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdani, T.M.; Won, J.M.; Alimi, A.M.; Karray, F. Multi-objective Feature Selection with NSGA II. In Adaptive and Natural Computing Algorithms, Proceedings of the International Conference on Adaptive and Natural Computing Algorithms, Warsaw, Poland, 11–14 April 2007; Beliczynski, B., Dzielinski, A., Iwanowski, M., Ribeiro, B., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germnay, 2007; pp. 240–247. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Xue, B.; Zhang, M.; Liang, J. A Grid-dominance based Multi-objective Algorithm for Feature Selection in Classification. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC), Virtual, 28 June–1 July 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.U.; Nadeem, A.; Malik, M.Z. Fair feature subset selection using multiobjective genetic algorithm. In Proceedings of the Genetic and Evolutionary Computation Conference Companion, New York, NY, USA, 9–13 July 2022; GECCO ’22. pp. 360–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Zhou, J.; Wu, Q.; Zhou, M.; Wen, J. A Length-Adaptive Non-Dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm for Bi-Objective High-Dimensional Feature Selection. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2023, 10, 1834–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Ma, H.; Lv, S.; Wang, L.; Deng, S. Enhanced NSGA-II-based feature selection method for high-dimensional classification. Inf. Sci. 2024, 663, 120269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, R.; Xue, B.; Zhang, M. Sparse Learning-Based Feature Selection in Classification: A Multi-Objective Perspective. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. Intell. 2024, 9, 2767–2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijai, P. A hybrid multi-objective optimization approach with NSGA-II for feature selection. Decis. Anal. J. 2025, 14, 100550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, G.; Zhang, M. Fitness Functions in Genetic Programming for Classification with Unbalanced Data. In Proceedings of the AI 2007: Advances in Artificial Intelligence, Gold Coast, Australia, 2–6 December 2007; Orgun, M.A., Thornton, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 769–775. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, C.; Jin, Y. An evolutionary algorithm for large-scale sparse multiobjective optimization problems. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2019, 24, 380–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Zhu, H.; Liang, J.; Słowik, A. Adaptive crossover operator based multi-objective binary genetic algorithm for feature selection in classification. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2021, 227, 107218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinley, B.; Maher, J.; O’Riordan, C.; Morgan, F. Maintaining healthy population diversity using adaptive crossover, mutation, and selection. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2011, 15, 692–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Chen, S.; Xiong, H. A high-dimensional feature selection method based on modified Gray Wolf Optimization. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 135, 110031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, W.; Kang, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X. A problem-specific non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm for supervised feature selection. Inf. Sci. 2021, 547, 841–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Xue, B.; Zhang, M. A duplication analysis-based evolutionary algorithm for biobjective feature selection. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2020, 25, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, K.; Pratap, A.; Agarwal, S.; Meyarivan, T. A fast and elitist multiobjective genetic algorithm: NSGA-II. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2002, 6, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitzler, E.; Laumanns, M.; Thiele, L. SPEA2: Improving the Strength Pareto Evolutionary Algorithm; TIK Report; Technical Report No. 103; Computer Engineering and Networks Laboratory: Zurich, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, H. MOEA/D: A multiobjective evolutionary algorithm based on decomposition. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2007, 11, 712–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Cheng, R.; Zhang, X.; Su, Y.; Jin, Y. A strengthened dominance relation considering convergence and diversity for evolutionary many-objective optimization. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2018, 23, 331–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Lu, C.; Zhang, X.; Tan, K.C.; Jin, Y. Solving Large-Scale Multiobjective Optimization Problems With Sparse Optimal Solutions via Unsupervised Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2021, 51, 3115–3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Tashi, Q.; Abdulkadir, S.J.; Rais, H.M.; Mirjalili, S.; Alhussian, H.; Ragab, M.G.; Alqushaibi, A. Binary Multi-Objective Grey Wolf Optimizer for Feature Selection in Classification. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 106247–106263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitzler, E.; Thiele, L.; Laumanns, M.; Fonseca, C.M.; Da Fonseca, V.G. Performance assessment of multiobjective optimizers: An analysis and review. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2003, 7, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- While, L.; Hingston, P.; Barone, L.; Huband, S. A faster algorithm for calculating hypervolume. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2006, 10, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Dataset Name | #Feature | #Sample | #Class | %Smallest Class | %Largest Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SRBCT | 2308 | 83 | 4 | 13 | 35 |

| 2 | Leukemia 1 | 5327 | 72 | 3 | 13 | 53 |

| 3 | DLBCL | 5469 | 77 | 2 | 25 | 75 |

| 4 | 9Tumor | 5726 | 60 | 9 | 3 | 15 |

| 5 | Brain Tumor 1 | 5920 | 90 | 5 | 4 | 67 |

| 6 | Brain Tumor 2 | 10,367 | 50 | 4 | 14 | 30 |

| 7 | Prostate | 10,509 | 102 | 2 | 49 | 51 |

| 8 | Leukemia 2 | 11,225 | 72 | 3 | 28 | 39 |

| 9 | 11Tumor | 12,533 | 174 | 11 | 4 | 16 |

| 10 | Lung Cancer | 12,600 | 203 | 5 | 3 | 68 |

| Datasets | NSGA-II | MOEA/D | SPEA2 | NSGA-II/SDR | MOEA/PSL | BMOGWO-S | AF-NSGA-II |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Mean | Mean | Mean | Mean | Mean | Mean | |

| (Std)W | (Std)W | (Std)W | (Std)W | (Std)W | (Std)W | Std | |

| DS01 | 6.23 | 5.46 | 6.28 | 6.21 | 9.75 | 9.93 | 9.99 |

| (6.53)− | (5.76)− | (6.36)− | (3.46)− | (8.92)− | (6.95)− | 1.56 | |

| DS02 | 5.69 | 5.16 | 5.73 | 5.76 | 9.61 | 9.73 | 9.99 |

| (7.93)− | (1.19)− | (1.14)− | (9.70)− | (2.65)− | (1.35)− | 1.72 | |

| DS03 | 6.00 | 5.48 | 5.97 | 5.97 | 9.81 | 9.98 | 9.99 |

| (5.57)− | (3.44)− | (5.42)− | (2.97)− | (1.16)− | (2.38)− | 1.17 | |

| DS04 | 3.70 | 3.45 | 3.75 | 3.75 | 6.12 | 6.57 | 8.05 |

| (1.17)− | (8.76)− | (9.97)− | (1.46)− | (2.78)− | (1.65)− | 3.29 | |

| DS05 | 5.36 | 4.97 | 5.37 | 5.35 | 8.80 | 8.91 | 9.37 |

| (1.32)− | (1.23)− | (7.05)− | (1.05)− | (3.44)− | (2.24)− | 1.31 | |

| DS06 | 5.27 | 4.91 | 5.18 | 5.20 | 8.79 | 9.10 | 9.59 |

| (8.36)− | (4.75)− | (5.57)− | (5.18)− | (1.77)− | (2.42)− | 1.30 | |

| DS07 | 5.46 | 5.10 | 5.45 | 5.39 | 9.16 | 9.47 | 9.73 |

| (9.48)− | (3.33)− | (5.39)− | (4.27)− | (1.50)− | (1.54)− | 8.78 | |

| DS08 | 5.82 | 5.44 | 5.77 | 5.78 | 9.76 | 9.96 | 9.99 |

| (5.11)− | (5.56)− | (3.98)− | (4.25)− | (1.22)− | (4.85)− | 8.33 | |

| DS09 | 5.00 | 4.59 | 4.94 | 4.89 | 8.39 | 8.66 | 9.18 |

| (9.82)− | (5.63)− | (9.40)− | (8.18)− | (1.04)− | (1.98)− | 1.42 | |

| DS10 | 5.13 | 4.78 | 5.17 | 5.10 | 9.29 | 9.27 | 9.81 |

| (1.00)− | (9.77)− | (1.04)− | (1.12)− | (4.06)− | (1.42)− | 9.21 | |

| +/−/≈ | 0/10/0 | 0/10/0 | 0/10/0 | 0/10/0 | 0/10/0 | 0/10/0 |

| Datasets | NSGA-II | MOEA/D | SPEA2 | NSGA-II/SDR | MOEA/PSL | BMOGWO-S | AF-NSGA-II |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Mean | Mean | Mean | Mean | Mean | Mean | |

| (Std)W | (Std)W | (Std)W | (Std)W | (Std)W | (Std)W | Std | |

| DS01 | 4.00 | 4.76 | 4.00 | 4.06 | 3.96 | 1.26 | 2.47 |

| (5.19)− | (3.98)− | (5.00)− | (3.90)− | (1.49)− | (6.79)− | 1.94 | |

| DS02 | 4.43 | 4.98 | 4.44 | 4.43 | 6.18 | 2.96 | 9.20 |

| (8.12)− | (4.34)− | (8.07)− | (7.96)− | (4.13)− | (1.36)− | 1.64 | |

| DS03 | 4.33 | 4.85 | 4.37 | 4.35 | 3.06 | 2.57 | 0.00 |

| (4.49)− | (2.42)− | (3.96)− | (5.11)− | (1.49)− | (2.33)− | 0.00 | |

| DS04 | 4.94 | 5.37 | 4.91 | 4.96 | 2.11 | 1.64 | 2.24 |

| (1.36)− | (7.23)− | (8.62)− | (1.28)− | (3.80)− | (1.38)− | 1.61 | |

| DS05 | 4.48 | 4.92 | 4.49 | 4.54 | 8.88 | 6.46 | 1.39 |

| (5.10)− | (2.50)− | (5.48)− | (6.04)− | (2.90)− | (2.88)− | 9.70 | |

| DS06 | 4.67 | 5.05 | 4.68 | 4.74 | 1.19 | 6.67 | 1.69 |

| (4.13)− | (3.19)− | (5.19)− | (5.86)− | (2.43)− | (2.67)− | 1.13 | |

| DS07 | 4.62 | 4.96 | 4.62 | 4.68 | 8.44 | 4.28 | 1.48 |

| (4.75)− | (1.87)− | (2.28)− | (5.14)− | (2.12)− | (1.70)− | 7.85 | |

| DS08 | 4.55 | 4.90 | 4.56 | 4.58 | 4.22 | 6.45 | 3.39 |

| (2.38)− | (2.40)− | (2.05)− | (2.46)− | (2.16)− | (5.63)− | 5.77 | |

| DS09 | 4.64 | 4.97 | 4.65 | 4.67 | 6.99 | 3.56 | 8.08 |

| (3.48)− | (2.70)− | (3.56)− | (5.89)− | (1.28)− | (1.30)− | 3.78 | |

| DS10 | 4.79 | 5.12 | 4.79 | 4.85 | 7.99 | 7.13 | 1.29 |

| (8.43)− | (5.40)− | (5.45)− | (5.34)− | (4.95)− | (1.60)− | 7.93 | |

| +/−/≈ | 0/10/0 | 0/10/0 | 0/10/0 | 0/10/0 | 0/10/0 | 0/10/0 |

| Datasets | NSGA-II | MOEA/D | SPEA2 | NSGA-II/SDR | MOEA/PSL | BMOGWO-S | AF-NSGA-II |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Mean | Mean | Mean | Mean | Mean | Mean | |

| (Std)W | (Std)W | (Std)W | (Std)W | (Std)W | (Std)W | Std | |

| DS01 | 6.39 | 5.69 | 6.38 | 6.34 | 9.86 | 9.98 | 9.98 |

| (4.17)− | (5.59)− | (4.63)− | (3.66)− | (1.00)− | (2.96)− | 3.72 | |

| DS02 | 6.04 | 5.60 | 6.03 | 5.97 | 9.90 | 9.85 | 9.93 |

| (3.85)− | (3.21)− | (4.63)− | (2.00)− | (6.56)− | (2.89)− | 1.90 | |

| DS03 | 6.08 | 5.61 | 6.04 | 6.06 | 9.93 | 9.99 | 9.99 |

| (3.91)− | (2.50)− | (2.49)− | (4.34)− | (4.56)− | (5.26)≈ | 1.17 | |

| DS04 | 3.52 | 3.44 | 3.80 | 3.67 | 6.34 | 5.69 | 6.65 |

| (3.18)− | (3.47)− | (4.65)− | (4.27)− | (6.92)≈ | (7.41)− | 5.21 | |

| DS05 | 4.90 | 4.62 | 4.83 | 4.79 | 8.29 | 8.25 | 8.74 |

| (2.70)− | (1.87)− | (2.98)− | (2.16)− | (6.83)≈ | (3.81)− | 3.54 | |

| DS06 | 5.15 | 4.93 | 5.15 | 5.12 | 8.62 | 8.06 | 8.74 |

| (2.22)− | (6.66)− | (2.47)− | (2.15)− | (3.87)− | (9.33)− | 3.58 | |

| DS07 | 5.34 | 5.06 | 5.38 | 5.49 | 9.10 | 9.11 | 9.13 |

| (3.70)− | (3.27)− | (7.59)− | (4.61)− | (3.87)≈ | (8.43)− | 7.57 | |

| DS08 | 5.87 | 5.54 | 5.86 | 5.84 | 9.87 | 9.99 | 9.99 |

| (2.92)− | (1.92)− | (1.63)− | (3.28)− | (1.20)− | (1.22)≈ | 1.17 | |

| DS09 | 5.03 | 4.79 | 5.05 | 5.04 | 8.61 | 8.66 | 8.99 |

| (2.55)− | (1.71)− | (1.84)− | (2.57)− | (2.99)≈ | (3.34)≈ | 4.95 | |

| DS10 | 5.23 | 5.10 | 5.37 | 5.30 | 9.25 | 9.25 | 9.43 |

| (3.07)− | (2.08)− | (2.01)− | (1.92)− | (3.78)≈ | (6.15)≈ | 3.29 | |

| +/−/≈ | 0/10/0 | 0/10/0 | 0/10/0 | 0/10/0 | 0/5/5 | 0/6/4 |

| Datasets | NSGA-II | MOEA/D | SPEA2 | NSGA-II/SDR | MOEA/PSL | BMOGWO-S | AF-NSGA-II |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Mean | Mean | Mean | Mean | Mean | Mean | |

| (Std)W | (Std)W | (Std)W | (Std)W | (Std)W | (Std)W | Std | |

| DS01 | 3.97 | 4.74 | 3.98 | 4.01 | 2.39 | 1.80 | 1.30 |

| (4.33)− | (5.29)− | (5.61)− | (4.42)− | (1.43)− | (1.86)− | 2.74 | |

| DS02 | 4.36 | 4.84 | 4.39 | 4.36 | 3.53 | 2.11 | 6.20 |

| (4.45)− | (4.07)− | (4.08)− | (6.84)− | (1.59)− | (1.66)− | 1.02 | |

| DS03 | 4.33 | 4.83 | 4.35 | 4.33 | 1.15 | 1.83 | 0.00 |

| (3.18)− | (3.28)− | (3.23)− | (4.45)− | (1.37)− | (5.78)≈ | 0.00 | |

| DS04 | 4.67 | 5.05 | 4.61 | 4.67 | 1.08 | 1.68 | 6.73 |

| (1.51)− | (1.74)− | (2.40)− | (2.23)− | (5.25)≈ | (6.77)− | 4.63 | |

| DS05 | 4.37 | 4.73 | 4.40 | 4.41 | 9.98 | 9.59 | 5.12 |

| (1.51)− | (8.01)− | (1.08)− | (7.14)− | (5.33)≈ | (4.57)− | 3.07 | |

| DS06 | 4.59 | 4.92 | 4.63 | 4.66 | 6.34 | 1.09 | 3.39 |

| (8.15)− | (1.80)− | (2.04)− | (5.75)− | (4.28)− | (1.02)− | 3.93 | |

| DS07 | 4.54 | 4.89 | 4.55 | 4.59 | 4.32 | 2.40 | 2.19 |

| (3.56)− | (2.24)− | (5.71)− | (3.44)− | (4.23)≈ | (6.73)≈ | 7.85 | |

| DS08 | 4.53 | 4.89 | 4.55 | 4.57 | 1.37 | 5.43 | 9.80 |

| (3.22)− | (2.12)− | (1.79)− | (3.61)− | (1.32)− | (1.35)≈ | 1.29 | |

| DS09 | 4.66 | 4.96 | 4.65 | 4.69 | 5.94 | 5.04 | 3.63 |

| (6.23)− | (3.73)− | (4.58)− | (5.58)− | (1.64)− | (2.10)≈ | 2.65 | |

| DS10 | 4.62 | 4.87 | 4.58 | 4.61 | 7.46 | 6.07 | 3.94 |

| (1.17)− | (6.32)− | (5.21)− | (7.15)− | (5.14)− | (5.76)≈ | 2.83 | |

| +/−/≈ | 0/10/0 | 0/10/0 | 0/10/0 | 0/10/0 | 0/7/3 | 0/5/5 |

| No. | NSGA-II | F-NSGA-II | A-NSGA-II | AF-NSGA-II |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Mean | Mean | Mean | |

| (Std)W | (Std)W | (Std)W | Std | |

| DS01 | ||||

| ()− | ()− | ()− | ||

| DS02 | ||||

| ()− | ()− | ()− | ||

| DS03 | ||||

| ()− | ()− | ()− | ||

| DS04 | ||||

| ()− | ()≈ | ()− | ||

| DS05 | ||||

| ()− | ()− | ()− | ||

| DS06 | ||||

| ()− | ()− | ()− | ||

| DS07 | ||||

| ()− | ()− | ()− | ||

| DS08 | ||||

| ()− | ()− | ()− | ||

| DS09 | ||||

| ()− | ()− | ()− | ||

| DS10 | ||||

| ()− | ()− | ()− | ||

| +/−/≈ | 0/10/0 | 0/9/1 | 0/10/0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Fan, R.; Cheng, L.; Gong, B.; Liu, J. An Improved Adaptive NSGA-II with Multiple Filtering for High-Dimensional Feature Selection. Electronics 2026, 15, 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010236

Wang Y, Fan R, Cheng L, Gong B, Liu J. An Improved Adaptive NSGA-II with Multiple Filtering for High-Dimensional Feature Selection. Electronics. 2026; 15(1):236. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010236

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Ying, Renjie Fan, Lei Cheng, Bo Gong, and Jiahao Liu. 2026. "An Improved Adaptive NSGA-II with Multiple Filtering for High-Dimensional Feature Selection" Electronics 15, no. 1: 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010236

APA StyleWang, Y., Fan, R., Cheng, L., Gong, B., & Liu, J. (2026). An Improved Adaptive NSGA-II with Multiple Filtering for High-Dimensional Feature Selection. Electronics, 15(1), 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010236