Optimization of Pumped Storage Capacity Configuration Considering Inertia Constraints and Duration Selection

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Assessment of Minimum Inertia Requirement in Power System

2.1. Minimum Inertia Based on the Constraint of RocoF

2.2. Minimum Inertia Based on the Constraint of Nadir

2.3. Minimum Inertia Requirement of the System

3. Optimal Configuration of Pumped Storage Considering Inertia Constraints

3.1. Objective Function

3.2. Constraints

3.2.1. Constraints on Wind Power and Photovoltaic Units Output

3.2.2. Constraints on Thermal Power Units

- Constraint on upper and lower limit of output power;where and are, respectively, the upper and lower limits of the output of the i-th thermal power unit.

- 2.

- Constraint on state;where is a Boolean variable representing the switching of the operating state of a thermal power unit during period t.

- 3.

- Constraint on ramp;where and represent the uphill and downhill climbing rates of the i-th thermal power unit, respectively; represents the unit scheduling duration. The additional item relaxes the constraints during start-up and shutdown by introducing , allowing the unit to break through the conventional climbing rate limit at the moment of start-up and shutdown, and avoiding the optimization model being unsolver due to strict constraints.

- 4.

- Constraint on minimum start-stop time;where and represent the continuous operation and shutdown times of the i-th thermal power unit, respectively; and are, respectively, the minimum allowable continuous operation and shutdown times for the i-th thermal power unit.

3.2.3. Constraints on Pumped Storage Units

- Constraint on duration-and-capacity bounding;

- 2.

- Constraint on rapid adjustment time of short-term unit;

- 3.

- Constraint on duration constraint of continuous support for medium and long-term units;

- 4.

- Constraint on full-station power coupling;

- 5.

- Constraint on state;where represents the Boolean variable indicating whether the d-class pumped storage unit is in the power generation condition at time t; is a Boolean variable indicating whether a d-class pumped storage unit is in the pumping condition at time t.

- 6.

- Constraint on storage capacity;where and are the minimum and maximum values of the upper reservoir capacity of the pumped storage power station, respectively; represents the storage capacity of the upper reservoir at time t; and are, respectively, the minimum and maximum values of the lower reservoir capacity of the pumped storage power station; represents the reservoir capacity at time t; and represent the water consumption of the pumped storage unit at time t under power generation and pumping conditions, respectively; is to optimize the water level of the upper reservoir at the end of the cycle; is the control target for optimizing the water level of the upper reservoir at the end of the cycle.

- 7.

- Constraint on upper and lower limit of output power;where and represent the minimum and maximum power values of d-class pumped storage units under power generation conditions, respectively; and are, respectively, the minimum and maximum power values of d-class pumped storage units under pumping conditions; and are respectively the power generation and pumping power of d-class pumped storage units at time t.

3.2.4. Constraints on Minimum Inertia of the System

3.2.5. Constraints on Power Balance

3.2.6. Peak-Valley Difference of the Load Curve

3.3. Model Solving

4. Case Analysis

4.1. Case Data

4.2. Results Presentation

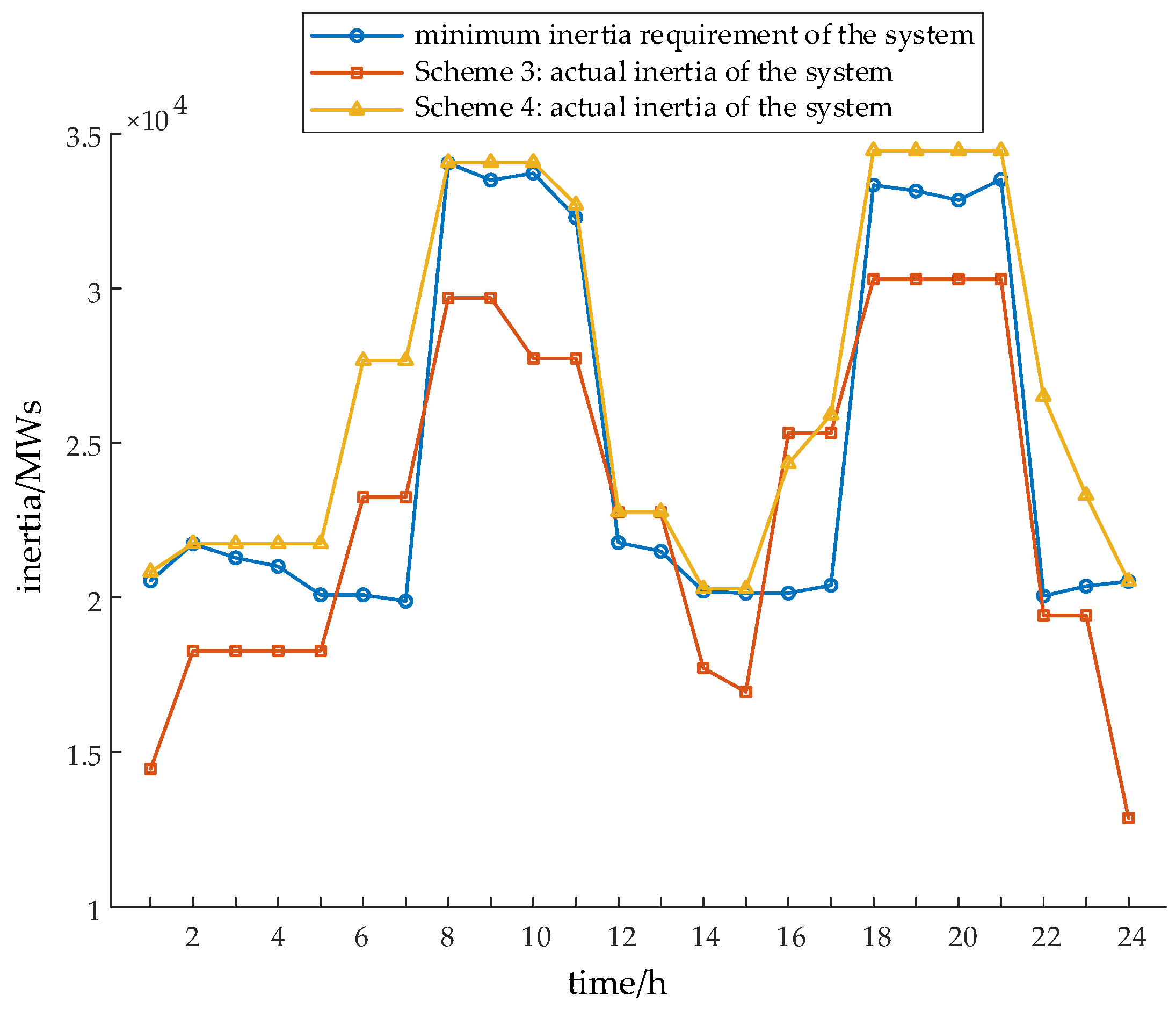

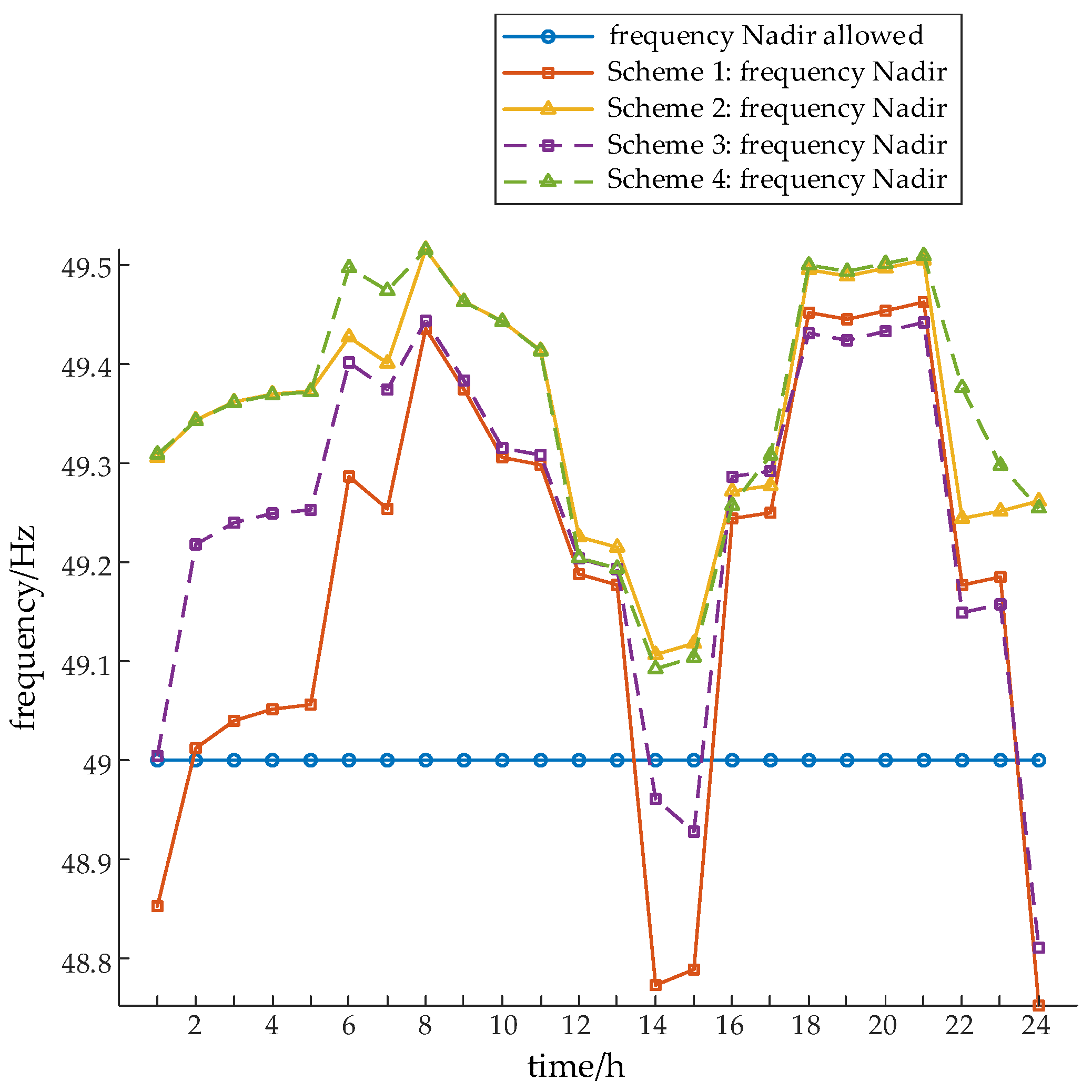

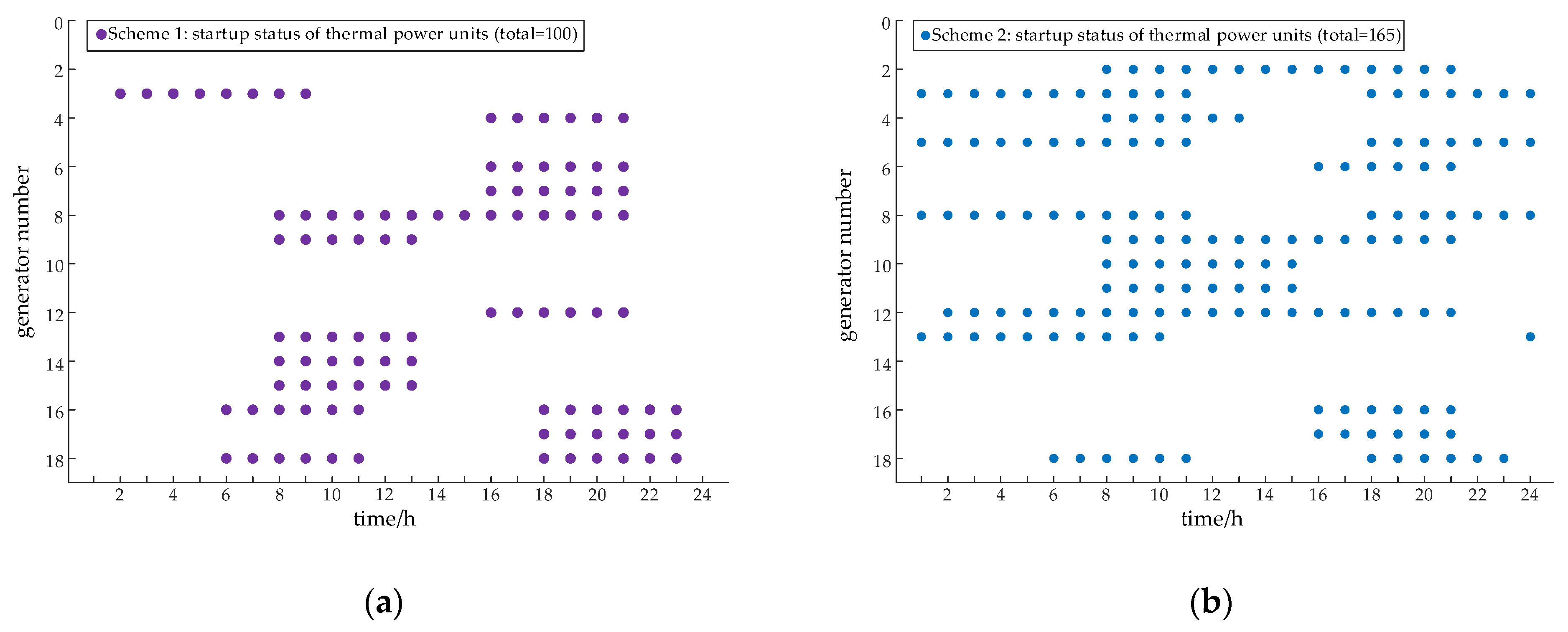

4.3. Influences on the Results Considering Inertia Constraints

- The comprehensive operating cost of the system in Scheme 2 is 4.39 million yuan higher than that in Scheme 1, and the comprehensive operating cost in Scheme 4 is 2.57 million yuan higher than that in Scheme 3. It can be seen that when considering the inertia constraint, the comprehensive operating cost has increased. The main reason for the increase in cost lies in the fact that the synchronous inertia of the system can only be provided by thermal power units, nuclear power units and pumped storage units. Therefore, when the system inertia is low, more thermal power units will be online, which in turn leads to an increase in the start-up and shutdown costs as well as the operating costs of thermal power;

- The cost of wind and solar power curtailment in Scheme 2 is 2.15 million yuan higher than that in Scheme 1, and in Scheme 4, it is 300,000 yuan higher than that in Scheme 3. It can be seen that when considering the inertia constraint, the cost of wind and solar power curtailment has in-creased. This is because thermal power units usually have a minimum technical output. When the power grid selects to operate more thermal power units, due to the constant load at a certain moment in the power grid, some new energy sources that could have been consumed are abandoned. At the same time, pumped storage units may be more used for frequency regulation rather than consuming renewable energy, further exacerbating the curtailment of wind and solar power.

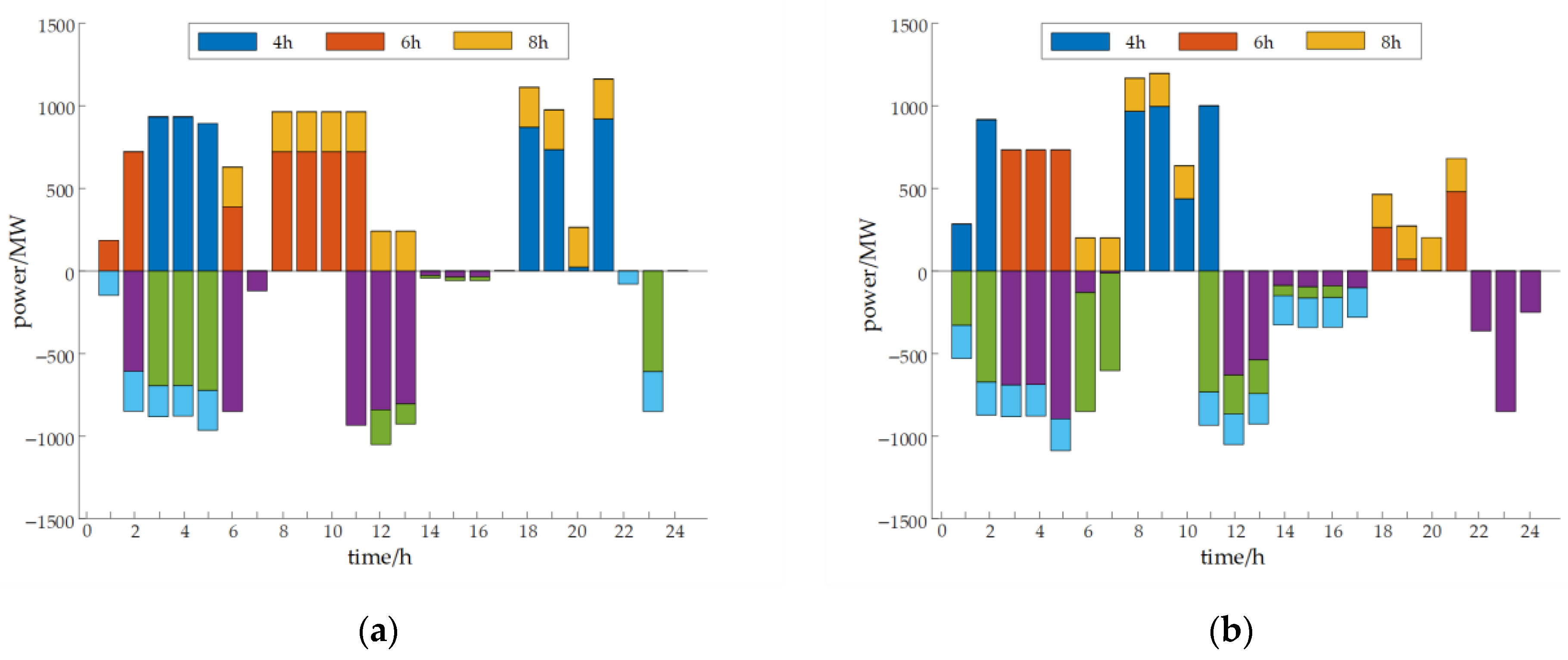

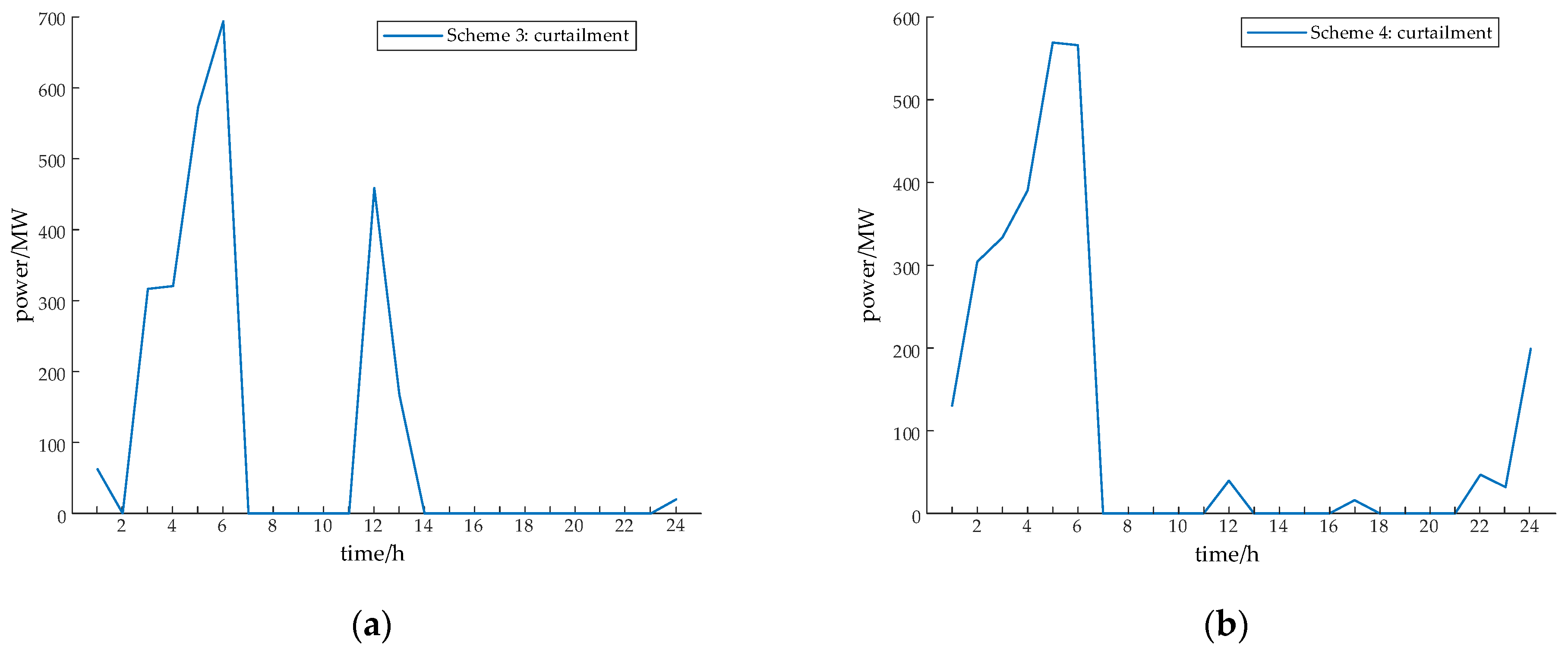

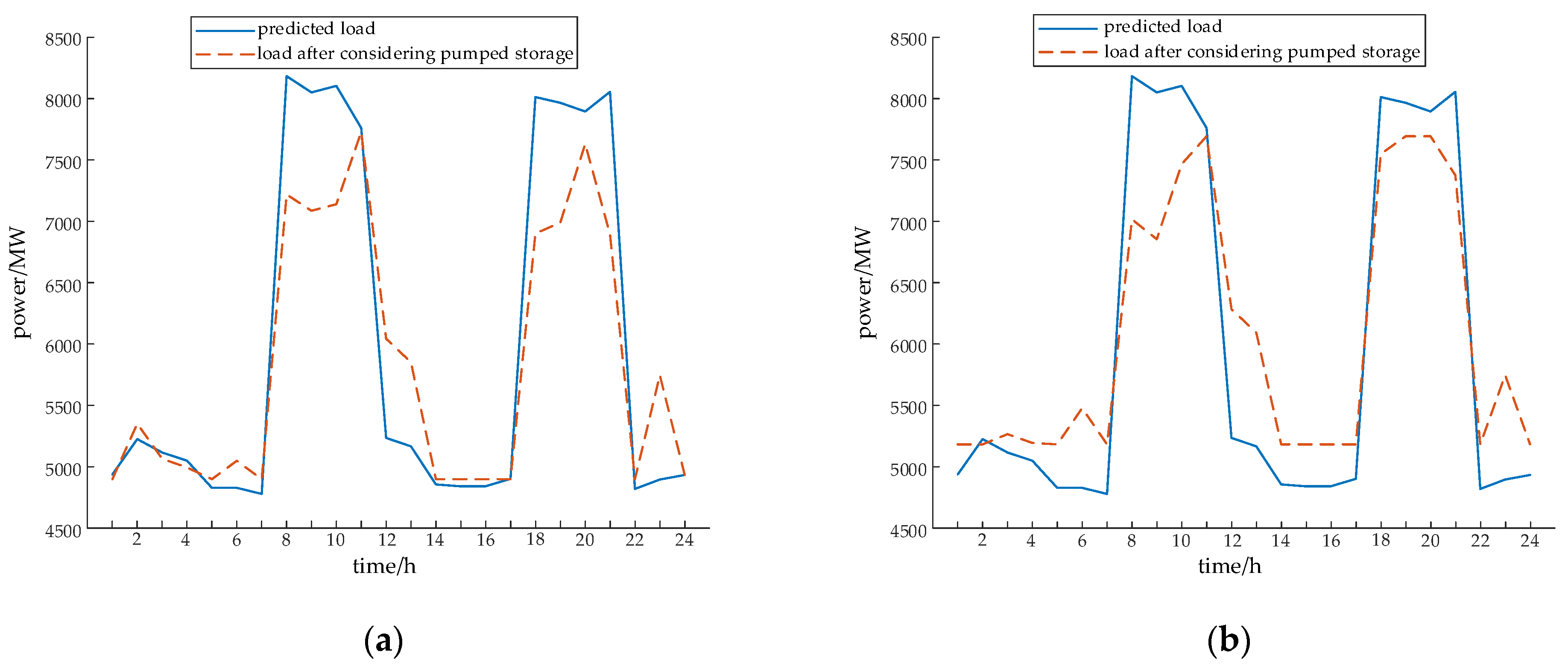

4.4. Influences on the Results Considering Duration Selection

- In Scheme 3, the operating cost of thermal power is reduced by 5.36 million yuan compared to Scheme 1, and in Scheme, it is reduced by 7.22 million yuan compared to Scheme 2. It can be seen that after considering the selection of pumped storage duration, the operating cost of thermal power has been significantly reduced. The reason is that in the hybrid configuration considering the selection of pumped storage duration, the 4 h unit provides rapid frequency regulation capability, sharing the instantaneous regulation pressure of thermal power. The 8 h unit undertakes long-term energy transfer, such as absorbing wind and solar power across time periods, reducing the fluctuation of thermal power output. Thermal power units have been able to operate stably within an efficient and economic range, avoiding frequent starts and stops as well as inefficient peak shaving;

- In Scheme 3, the proportion of thermal power operation cost in the comprehensive system operation cost decreased by approximately 25% compared to Scheme 1. In Scheme 4, the pro-portion of thermal power operation cost in the comprehensive operation cost decreased by approximately 25% compared to Scheme 2. It can be seen that after considering the selection of pumped storage duration, the proportion of thermal power operation cost in the total long-term dispatching has decreased. The reason lies in that the hybrid units have a more obvious substitution effect on the functions of thermal power, the regulating value of pumped storage units has significantly increased, and the system’s dependence on thermal power units has decreased;

- In Scheme 3, the cost of wind and solar power curtailment is reduced by 1.77 million yuan compared to Scheme, and in Scheme 4, it is reduced by 3.62 million yuan compared to Scheme 2. It can be seen that after considering the selection of pumped storage duration, the cost of wind and solar power curtailment has decreased. The reason lies in the fact that the regulation capacity of a single 6 h unit is limited, while in a hybrid configuration, a 4 h unit can quickly respond to fluctuations in wind and solar power and reduce instantaneous power curtailment. The 8 h unit can charge a large amount of new energy during off-peak hours. The coordination of hybrid units can significantly enhance the capacity to consume renewable energy. In addition, in Section 3.3, the cost of wind and solar power cursory in Scheme 2 is 2.15 million yuan higher than that in Scheme 1, and in Scheme 4, it is 300,000 yuan higher than that in Scheme 3. It can be seen that under the inertia constraint, the regulation failure of the system under a single 6 h unit is due to the fact that the dispatching strategy forces pumped storage to prioritize frequency regulation, which cannot fully consume wind and solar power, and the regulation rate of a single 6 h unit is insufficient. The system is forced to rely on thermal power to provide instantaneous inertia support. As thermal power continues to operate, its technical output limit squeezes the space for new energy, further exacerbating power curtailment;

- The comprehensive operating cost of the system in Scheme 3 is 6.94 million yuan higher than that in Scheme 1, and in Scheme 4, it is 5.11 million yuan higher than that in Scheme 2. It can be seen that after considering the selection of pumped storage duration, the comprehensive operating cost of the system has increased. The reason lies in the increase in the cost-sharing ratio of pumped storage regulation. Although these incremental costs have pushed up the overall operating cost of the system, in essence, they are the necessary cost for the power system to transform from a fuel cost core to a regulation service core.

4.5. Influences on the Results Considering Inertia Constraints Under Mixed Durations

- When considering the inertia constraints, the total power rises from 1897.3 MW to 1933.3 MW. This is because the inertia constraint places higher demands on the system’s frequency regulation capability. The inertia provided by pumped storage is used in conjunction with thermal power and nuclear power units to jointly meet the inertia requirements of the power grid;

- When inertia constraints are taken into account, the proportion of configured power and con-figured capacity of the 4 h unit has both increased compared to when inertia constraints are not considered. This is because the 4 h unit has a faster response speed and is more suitable for providing inertia support;

- When inertia constraints are taken into account, the proportion of configured power and con-figured capacity of the 8 h unit is both lower compared to when inertia constraints are not considered. This indicates that the priority of dynamic stability requirements in the power system is higher than that of simple capacity scale.

5. Conclusions

- Inertia constraint is a key factor affecting the economic operation of the system and the consumption of new energy. To ensure the stability of the system frequency, it is necessary to maintain a sufficient level of synchronous inertia, which will force more thermal power units to be in an online state. The simulation results of this paper show that considering the inertia constraints will lead to a certain increase in the comprehensive operating cost of the system. Meanwhile, the minimum technical output of thermal power units limits their regulation flexibility, occupies the space for the consumption of new energy, and causes the cost of wind and solar power curtailment to rise;

- The duration selection strategy of pumped storage power stations has a significant impact on the system operation mode. The adoption of a mixed configuration mode of 4 h and 8 h units demonstrates significant synergistic advantages compared to a single 6 h configuration. In the hybrid configuration mode, the 4 h unit effectively shares the instantaneous frequency regulation pressure of the system with its rapid response capability, while the 8 h unit better undertakes the tasks of long-term energy transfer and new energy consumption. This division of labor enables thermal power units to operate under more efficient and stable conditions, significantly reducing the operating costs of thermal power and their proportion in the total cost. At the same time, it enhances the system’s capacity to absorb renewable energy and effectively lowers the costs of wind and solar power curtailment;

- The system optimization objective needs to strike a balance between stability and economy. Although the frequency safety of the system is guaranteed after considering the inertia constraint, and the configuration strategy that takes into account the duration selection brings about the optimization of the cost structure, its investment power cost is relatively high, resulting in an increase in the comprehensive operating cost of the system. This highlights a key challenge in the transition of power systems: the investment in flexibility and stability-enhancing resources such as pumped storage inevitably introduces additional costs. These costs can be viewed as necessary for shifting the system’s operational paradigm from being primarily fuel-cost-centric to one that values regulation services and security assurance. In this article, such costs can be regarded as the necessary cost for the system to shift from being centered on fuel costs to being centered on regulation services and security guarantees.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Parameters of Thermal Power Units

| Generator Number | Minimum Output/MW | Maximum Output/MW | Inertial Time Constant/s | Start-Stop Cost/CNY |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 72 | 180 | 3.5 | 6000 |

| 2 | 222 | 556 | 5.0 | 6000 |

| 3 | 135 | 338 | 5.7 | 6000 |

| 4 | 320 | 799 | 3.5 | 6000 |

| 5 | 195 | 487 | 5.0 | 6000 |

| 6 | 287 | 717 | 3.5 | 6000 |

| 7 | 293 | 733 | 3.5 | 6000 |

| 8 | 197 | 492 | 5.0 | 10,000 |

| 9 | 63 | 158 | 5.8 | 6000 |

| 10 | 63 | 158 | 5.8 | 6000 |

| 11 | 193 | 483 | 5.0 | 6000 |

| 12 | 72 | 180 | 5.8 | 6000 |

| 13 | 95 | 237 | 5.8 | 6000 |

| 14 | 288 | 719 | 3.5 | 6000 |

| 15 | 288 | 719 | 3.5 | 6000 |

| 16 | 288 | 719 | 3.5 | 10,000 |

| 17 | 288 | 719 | 3.5 | 6000 |

| 18 | 288 | 719 | 3.5 | 6000 |

References

- Zhang, J.L.; Xu, Z. Regional Inertia Configuration Method of Renewable Energy Power System Considering RoCoF Constraint. Acta Energiae Solaris Sin. 2023, 44, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, C.; Liu, M.Q.; Peng, J.Z.; Wang, Y.H.; Liu, Y.X.; Gao, S.L.; Zheng, Z.S.; Liao, J.Q. Disturbance Frequency Trajectory Prediction in Power Systems Based on LightGBM Spearman. Electronics 2024, 13, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.Y.; Gai, C.H.; Qi, H.; Sun, R.J. Review on Data-driven Dynamic Security Assessment of Power Systems. Shandong Electr. Power 2024, 51, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.X.; Yang, Y.; Huang, H.X.; Zhong, H.W. An Overview and Outlook of the Operation and Control of Large-scale Pumped Hydro Storages in Modern Power Systems. Proc. CSEE 2025, 45, 80–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.F.; Oh, U.J.; Prak, J.C.; Park, E.S.; Im, H.B.; Lee, K.Y.; Choi, J.S. A Review of World-wide Advanced Pumped Storage Hydropower Technologies. IFAC Pap. 2022, 55, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.Q.; Wen, Y.F.; He, Y.; You, G.Z.; Li, H.X. Estimation of Medium- and Long-term Inertia Level Tendency for Power System and Its Application. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2024, 48, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Zhu, Y.J.; Fu, Y. Wind-storage Cooperative Fast Frequency Response Technology Based on System Inertia Demand. Proc. CSEE 2023, 43, 5415–5429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.H.; Wen, Y.F.; Yang, W.F. Inertia Security Region: Concept, Characteristics, and Assessment Method. Proc. CSEE 2021, 41, 3065–3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.C.; Sun, H.D.; Li, W.F.; Yan, J.F.; Yu, Z.H.; Yang, C. Minimum Inertia Estimation of Power System Considering Dynamic Frequency Constraints. Proc. CSEE 2022, 42, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.D.; Sun, Y.R.; Xu, B.; Zhang, J.L.; Liu, Q. Minimum inertia and primary frequency capacity assessment for a new energy high permeability power system considering frequency stability. Power Syst. Prot. Control 2021, 49, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Z.D.; Zhang, N.; Teng, F. Frequency-Constrained Resilient Scheduling of Microgrid: A Distributionally Robust Approach. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2021, 12, 4914–4925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Yang, D.Y.; Cai, G.W. Dynamic Frequency Constraint Unit Commitment in Large-scale WindPower Grid Connection. Power Syst. Technol. 2020, 44, 2513–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.M.; Liu, L.; Cheng, H.Z.; Lu, J.Z.; Zhang, J.P.; Li, G. Review and Prospects of Planning and Operation Optimization for Electrical Power Systems Considering Frequency Security. Power Syst. Technol. 2022, 46, 250–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.X.; Li, F.X.; Cui, H.T. Analytical Method to Aggregate Multi-Machine SFR Model with Applications in Power System Dynamic Studies. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2018, 33, 6355–6367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Liu, D.; Yang, X.Y.; Liu, Z.W.; Ji, X.T.; Cao, K.; Wang, W. Optimal Operation Strategy of High Proportion New Energy Power System Based on Minimum Inertia Evaluation. Power Syst. Technol. 2023, 47, 502–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Wang, W.Q.; Wang, Y.F.; Wu, C.P. Optimal Dispatching of Wind-photovoltaic-thermal-storage Combined System Considering Minimum Inertia Constraints. Proc. CSU-EPSA 2024, 36, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.Q.; Wang, C.M.; Zheng, H.K.; Li, Y.K.; Han, J.B. Frequency constrained unit commitment and economic dispatch with storage in low-inertia power system. Adv. Technol. Electr. Eng. Energy 2020, 39, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedighizadeh, M.; Esmaili, M.; Mousavi-Taghiabadi, S.M. Optimal energy and reserve scheduling for power systems considering frequency dynamics, energy storage systems and wind turbines. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 228, 341–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.W.; Feng, X.M.; Wang, H.B. Analysis on the Competitiveness of Pumped Storage Power Station with Different Continuous Full Output Hours in the Electricity Spot Market. Hydropower Pumped Storage 2024, 10, 10–17+25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.D.; Ding, Q.L. A Preliminary Research on the Representation Form of Spatial-temporal Distribution Characteristics of Power System Inertia Under Large Disturbances. Proc. CSEE 2024, 44, 4601–4615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Y.K.; Wyman-Pain, H.; Li, F.R.; Bhakar, R.; Mishra, S.; Padhy, N.P. Demand Side Contributions for System Inertia in the GB Power System. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2018, 33, 3521–3530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Azizipanah-Abarghooee, R.; Azizi, S.; Ding, L.; Terzija, V. Smart frequency control in low inertia energy systems based on frequency response techniques: A review. Applied Energy 2020, 279, 115798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.Q.; Wen, Y.F.; Chi, F.D.; Wang, K.; Li, L. Research Framework and Prospect on Power System Inertia Estimation. Proc. CSEE 2021, 41, 6842–6856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.G.; Bao, Y.Q.; Yang, X.; Ji, Z.Y. Optimal Scheduling Strategy for Thermal Power Units Engaged in Deep Peak Regulation Under Multiple Operating Conditions. Proc. CSU-EPSA 2025, 37, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scheme | Total Cost of Full-Cycle Operation (107 CNY) | Start-Up and Shutdown Costs of Thermal Power Plants (104 CNY) | Operating Costs of Thermal Power (107 CNY) | Cost of Wind and Photovoltaic Power Curtailment (106 CNY) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.4414 | 22.0 | 2.4545 | 2.7816 |

| 2 | 3.8808 | 24.0 | 2.8920 | 4.9287 |

| 3 | 4.1352 | 20.8 | 1.9185 | 1.0156 |

| 4 | 4.3920 | 24.2 | 2.1701 | 1.3135 |

| Scheme | Configuration Power/MW | Configuration Capacity/MWh | Configuration Capacity Proportion/% | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 h | 6 h | 8 h | total | 4 h | 6 h | 8 h | total | 4 h | 6 h | 8 h | |

| 3 | 933.2 | 722.9 | 241.2 | 1897.3 | 3732.8 | 4337.4 | 1929.6 | 9999.8 | 37.3 | 43.4 | 19.3 |

| 4 | 1000.0 | 732.9 | 200.4 | 1933.3 | 4000.0 | 4397.4 | 1603.2 | 10,000.6 | 40.0 | 44.0 | 16.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhu, L.; Zhong, Z.; Hua, D.; Guo, J.; Gong, Z.; Liang, K.; Zheng, W.; Shi, L.; Wu, F.; Li, Y. Optimization of Pumped Storage Capacity Configuration Considering Inertia Constraints and Duration Selection. Electronics 2026, 15, 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010175

Zhu L, Zhong Z, Hua D, Guo J, Gong Z, Liang K, Zheng W, Shi L, Wu F, Li Y. Optimization of Pumped Storage Capacity Configuration Considering Inertia Constraints and Duration Selection. Electronics. 2026; 15(1):175. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010175

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Lingkai, Ziwei Zhong, Danwen Hua, Junshan Guo, Zhiqiang Gong, Kai Liang, Wei Zheng, Linjun Shi, Feng Wu, and Yang Li. 2026. "Optimization of Pumped Storage Capacity Configuration Considering Inertia Constraints and Duration Selection" Electronics 15, no. 1: 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010175

APA StyleZhu, L., Zhong, Z., Hua, D., Guo, J., Gong, Z., Liang, K., Zheng, W., Shi, L., Wu, F., & Li, Y. (2026). Optimization of Pumped Storage Capacity Configuration Considering Inertia Constraints and Duration Selection. Electronics, 15(1), 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010175