The SMA: A Novel 2D Matrix-Based Lightweight Block Cipher for IoT Security

Abstract

1. Introduction

- A compact 2D matrix-based permutation layer that achieves rapid full-bit diffusion within a lightweight structure, without increasing block or key sizes.

- An improved key scheduling mechanism that enhances round-key randomness and strengthens resistance to key-related cryptanalysis.

- A complete security and performance evaluation demonstrating that SMA satisfies lightweight cipher requirements and is efficient for mobile and IoT encryption applications.

2. Two-Dimensional Cipher Design Architecture

2.1. Two-Dimensional Cipher Structure

2.2. Two-Dimensional Matrix Permutation vs. MDS Diffusion Matrices

2.3. Advantages of the 2D Design

- Compact Implementation: Maintains the standard 64-bit block without expanding key or round parameters.

- High Diffusion Efficiency: Each round efficiently redistributes bits across rows and columns.

- Hardware and Software Flexibility: The matrix-based structure can be efficiently implemented in both microcontroller and software environments.

- Enhanced Security: The combination of rotation and transposition reduces the probability of differential and linear correlations, verified experimentally in Section 4.

3. Proposed SMA Block Cipher

3.1. Algorithm Specification

3.2. Encryption Algorithm

| Algorithm 1 Pseudocode of the SMA Block Cipher (Encryption) | |

| 1: | RoundKeysGeneration (Key) // produces K1...K20 |

| 2: | for i = 1 to 20 do |

| 3: | AddRoundKey (State, RoundKeyi) |

| 4: | SubNibble (State) |

| 5: | 2DMatrixPermutation(State) |

| 6: | end for |

| Algorithm 2 Pseudocode of the SMA Block Cipher (Decryption) | |

| 1: | RoundKeysGeneration (Key) // produces K1...K20 |

| 2: | for i = 1 to 20 do |

| 3: | 2DMatrixPermutation −1(State) |

| 4: | SubNibble −1 (State) |

| 5: | AddRoundKey (State, RoundKeyi) |

| 6: | end for |

3.2.1. AddRoundKey Layer

3.2.2. SubNibble Layer

| Algorithm 3 Pseudocode of SubNibble SMA Block Cipher | |

| 1: | function SubNibble(state [8]) // state: array of 8 bytes |

| 2: | for i from 0 to 7 do |

| 3: | high = (state[i] >> 4) // upper 4 bits |

| 4: | low = (state[i] & 0x0F) // lower 4 bits |

| 5: | high’ = SBOX[high] // PRESENT S-box lookup |

| 6: | low’ = SBOX[low] // PRESENT S-box lookup |

| 7: | end for |

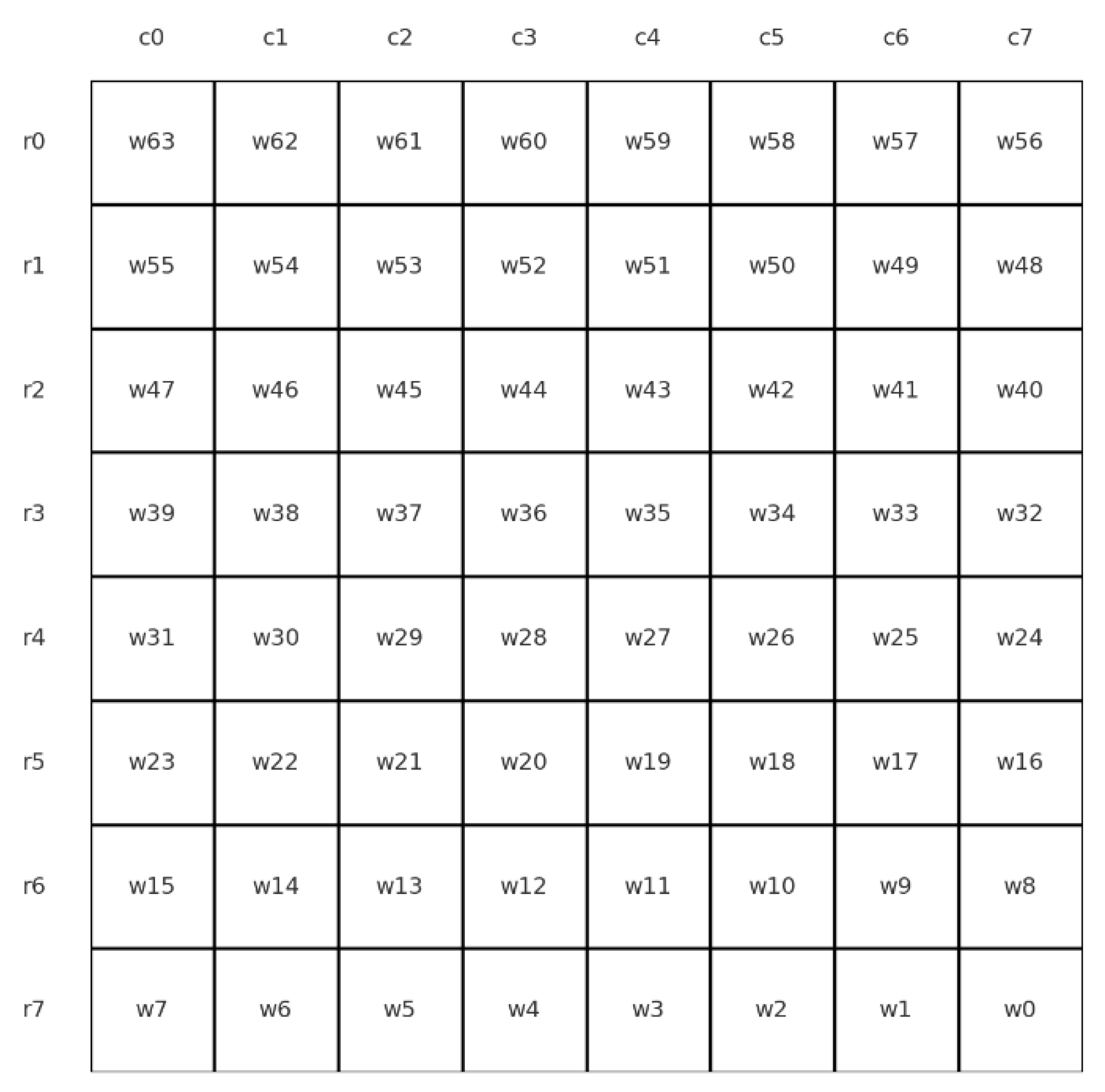

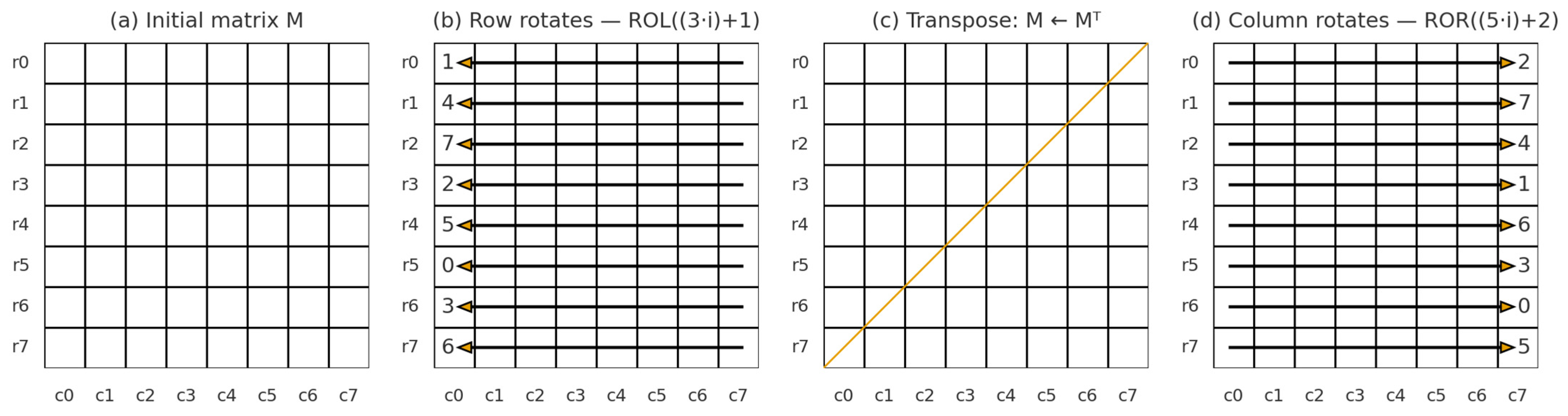

3.2.3. 2DMatrixPermutation Layer

3.3. Key Schedule Algorithm

- Bit-Rotation

- 2.

- S-box Substitution

- 3.

- Byte Swapping

- 4.

- Round Constant Addition

- 5.

- Round Key Extraction

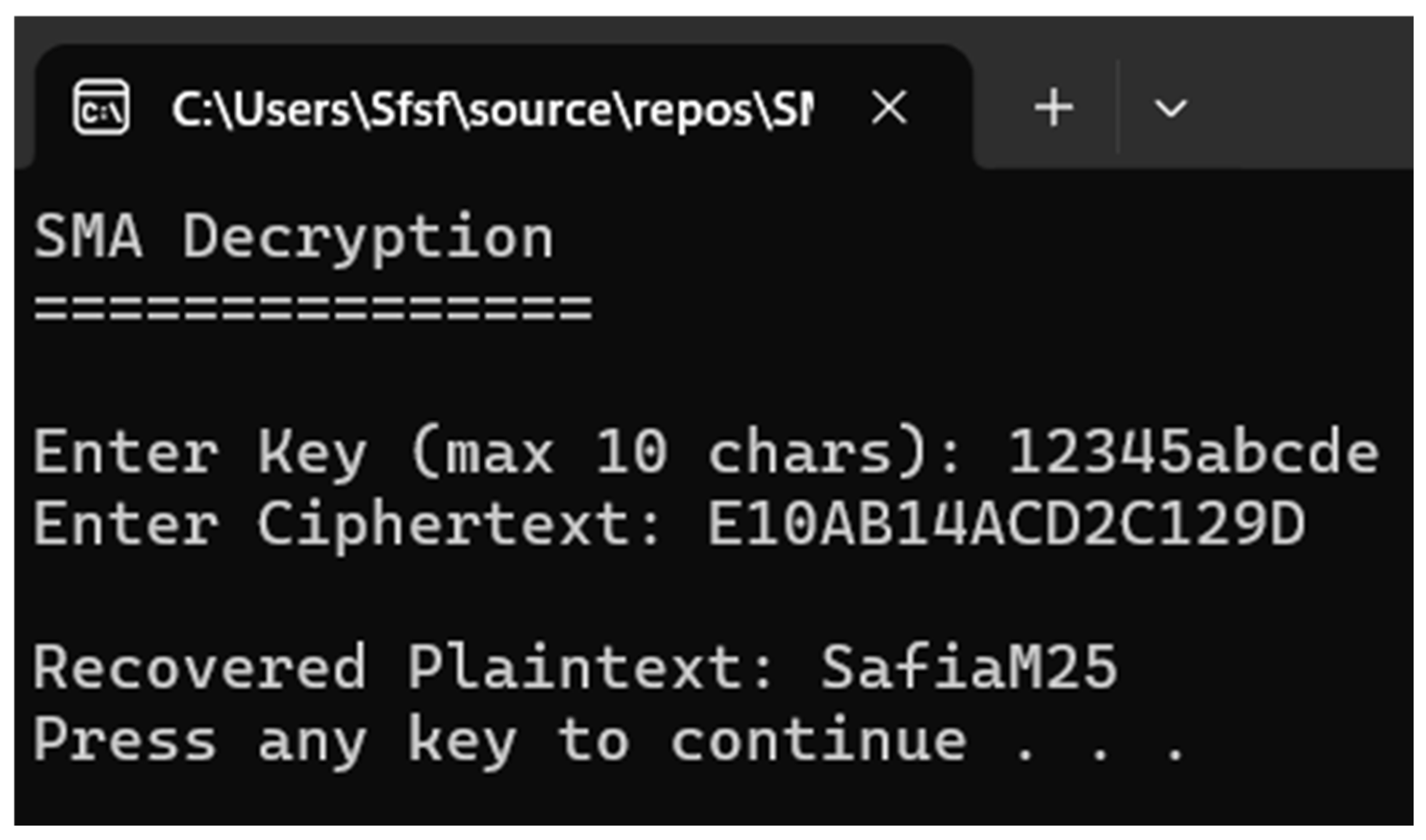

3.4. Test Vectors

4. Results

4.1. Avalanche Effect Tests

4.1.1. Correlation Coefficient Test

4.1.2. Bit Error Test

4.1.3. Key Sensitivity Test

4.2. Randomness Test

4.3. Cryptanalysis Attacks

4.3.1. Differential Cryptanalysis (DC)

4.3.2. Linear Cryptanalysis (LC)

4.3.3. Comparison DC and LC

4.4. Performance Evaluation

5. Discussion

6. Software Implementation

6.1. Desktop Application

6.2. IoT Simulation Environment

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jonsson, P.; Cerwall, P.; Lundvall, A.; von Koch, D.; Davis, S. Ericsson Mobility Report. 2025. Available online: https://www.ericsson.com/4aca6f/assets/local/reports-papers/mobility-report/documents/2025/ericsson-mobility-report-november-2025.pdf#page=34.07 (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Taylor, P. IoT Connections Worldwide 2034|Statista, 19 November 2025. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1183457/iot-connected-devices-worldwide/?srsltid=AfmBOoqOnd3slJCb3TbTBdhfl9BFWISru7zpS36K9f_DJRFz4bOgGotD (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Hamza, A.; Kumar, B. A Review Paper on DES, AES, RSA Encryption Standards. 2020. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/9336800/ (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Daemen, J.; Rijmen, V. AES Proposal: Rijndael; NIST Computer Security Resource Center: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 1999; pp. 1–45.

- Dhanda, S.S.; Singh, B.; Jindal, P. Lightweight Cryptography: A Solution to Secure IoT. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2020, 112, 1947–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanov, A.; Knudsen, L.R.; Leander, G.; Paar, C.; Poschmann, A. PRESENT: An Ultra-Lightweight Block Cipher. In Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems-CHES 2007, Proceedings of the 9th International Workshop, Vienna, Austria, 10–13 September 2007; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 450–466. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Bao, Z.; Lin, D.; Rijmen, V.; Yang, B.; Verbauwhede, I. RECTANGLE: A Bit-slice Lightweight Block Cipher Suitable for Multiple Platforms. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2015, 58, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banik, S.; Pandey, S.K.; Peyrin, T.; Sasaki, Y.; Sim, S.M.; Todo, Y. GIFT: A Small Present: Towards Reaching the Limit of Lightweight Encryption. In Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems–CHES 2017, Proceedings of the International Conference on Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems 2017, Taipei, Taiwan, 25–28 September 2017; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 10529, pp. 321–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansod, G.; Patil, A.; Sutar, S.; Pisharoty, N. NUX: An ultra lightweight cipher design for security in pervasive computing. In Proceedings of the Wireless On-Demand Network Systems and Services Conference WONS 2017, Jackson, WY, USA, 21–24 February 2017; Volume 9, pp. 5238–5251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, A.A.; Ab Halim, A.H.; Ridzuan, F.; Zakaria, N.H.; Daud, M. LAO-3D: A Symmetric Lightweight Block Cipher Based on 3D Permutation for Mobile Encryption Application. Symmetry 2022, 14, 2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Nikova, S.; Law, Y.W. KLEIN: A New Family of Lightweight Block Ciphers. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Radio Frequency Identification: Security and Privacy Issues, Amherst, MA, USA, 26–28 June 2011; Volume 7055, pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Nofaie, S.M.; Sharaf, S.; Molla, R. Design Trends and Comparative Analysis of Lightweight Block Ciphers for IoTs. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salunke, R.; Bansod, G.; Naidu, P. Design and Implementation of a Lightweight Encryption Scheme for Wireless Sensor Nodes. In Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 998, pp. 566–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Peyrin, T.; Poschmann, A.; Robshaw, M. The LED Block Cipher. In Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems–CHES 2011; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; Volume 6917, pp. 326–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adomnicai, A.; Berger, T.P.; Clavier, C.; Francq, J.; Huynh, P.; Lallemand, V.; Le Gouguec, K.; Minier, M.; Reynaud, L.; Thomas, G. Lilliput-AE: A New Lightweight Tweakable Block Cipher for Authenticated Encryption with Associated Data; NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2019.

- Elumalai, R.; Reddy, A.R. Improving Diffusion Power of AES Rijndael with 8x8 MDS Matrix. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 2011, 3, 1. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Improving-diffusion-power-of-AES-Rijndael-with-8x8-R.Elumalai-Dr.A.R.Reddy/4ccbbef57c622d835f41275ca107c54f92118117 (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Duval, S.; Leurent, G. MDS Matrices with Lightweight Circuits. IACR Trans. Symmetric Cryptol. 2018, 2018, 48–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leurent, G. MDS Matrices. In Symmetric Cryptography: Design and Security Proofs; John Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 99–109. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, C.E. Communication theory of secrecy systems. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1949, 28, 656–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Jap, D.; Roy, D.B.; Chakraborty, A.; Bhasin, S.; Mukhopadhyay, D. A Framework to Counter Statistical Ineffective Fault Analysis of Block Ciphers Using Domain Transformation and Error Correction. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2020, 15, 1905–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imdad, M.; Ramli, S.N.; Mahdin, H. An Enhanced Key Schedule Algorithm of PRESENT-128 Block Cipher for Random and Non-Random Secret Keys. Symmetry 2022, 14, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abikoye, O.C.; Haruna, A.D.; Abubakar, A.; Akande, N.O.; Asani, E.O. Modified Advanced Encryption Standard Algorithm for Information Security. Symmetry 2019, 11, 1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Majumdar, A.; Nath, S.; Dutta, A.; Baishnab, K.L. LRBC: A lightweight block cipher design for resource constrained IoT devices. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2023, 14, 5773–5787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, A.A.; Azni, A.H.; Ridzuan, F.; Zakaria, N.H.; Daud, M. Modifications of Key Schedule Algorithm on RECTANGLE Block Cipher. Commun. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2021, 1347, 194–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rukhin, A.; Soto, J.; Nechvatal, J.; Smid, M.; Barker, E. A Statistical Test Suite for Random and Pseudorandom Number Generators for Cryptographic Applications; DTIC: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, N.A.N.; Chew, L.C.N.; Zakaria, A.A.; Seman, K.; Norwawi, N.M. The Comparative Study Of Randomness Analysis Between Modified Version Of LBlock Block Cipher And Its Original Design. Int. J. Comput. Inf. Technol. 2015, 4, 867–875. [Google Scholar]

- Preishuber, M.; Hutter, T.; Katzenbeisser, S.; Uhl, A. Depreciating motivation and empirical security analysis of chaos-based image and video encryption. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2018, 13, 2137–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Dong, X.; Yu, H. MILP-based Differential Attack on Round-reduced GIFT. In Topics in Cryptology–CT-RSA 2019, Proceedings of the Cryptographers' Track at the RSA Conference 2019, San Francisco, CA, USA, 4–8 March 2019; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C.; Zhang, W.; Ding, T.; Xiang, Z. Improving the MILP-based Security Evaluation Algorithm against Differential/Linear Cryptanalysis Using A Divide-and-Conquer Approach. IACR Trans. Symmetric Cryptol. 2019, 2019, 438–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature | 2D Matrix Permutation | MDS Matrix Diffusion |

|---|---|---|

| Type of Operation | Pure permutation (bit/nibble rearrangement) using an 8 × 8 matrix. | Linear mixing using GF(2ⁿ) matrix multiplication. |

| Diffusion Mechanism | Bit-level rearrangement across rows/columns. | Optimal branch number from algebraic mixing. |

| Hardware Cost | Very low; only indexing. | High; many XORs and GF multipliers. |

| Software Cost | Extremely lightweight. | More expensive due to linear algebra operations. |

| Diffusion Speed | Requires multiple rounds. | Full diffusion in one round. |

| Suitability for IoT | Excellent for constrained devices. | Less suitable for ultra-light devices. |

| x | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F |

| S(x) | 5 | E | F | 8 | C | 1 | 2 | D | B | 4 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 9 | A |

| c0 | c1 | c2 | c3 | c4 | c5 | c6 | c7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 0 |

| r1 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| r2 | 23 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

| r3 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 24 | 25 |

| r4 | 37 | 38 | 39 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 |

| r5 | 40 | 41 | 42 | 43 | 44 | 45 | 46 | 47 |

| r6 | 51 | 52 | 53 | 54 | 55 | 48 | 49 | 50 |

| r7 | 62 | 63 | 56 | 57 | 58 | 59 | 60 | 61 |

| c0 | c1 | c2 | c3 | c4 | c5 | c6 | c7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r0 | 1 | 12 | 23 | 26 | 37 | 40 | 51 | 62 |

| r1 | 2 | 13 | 16 | 27 | 38 | 41 | 52 | 63 |

| r2 | 3 | 14 | 17 | 28 | 39 | 42 | 53 | 56 |

| r3 | 4 | 15 | 18 | 29 | 32 | 43 | 54 | 57 |

| r4 | 5 | 8 | 19 | 30 | 33 | 44 | 55 | 58 |

| r5 | 6 | 9 | 20 | 31 | 34 | 45 | 48 | 59 |

| r6 | 7 | 10 | 21 | 24 | 35 | 46 | 49 | 60 |

| r7 | 0 | 11 | 22 | 25 | 36 | 47 | 50 | 61 |

| c0 | c1 | c2 | c3 | c4 | c5 | c6 | c7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r0 | 51 | 62 | 1 | 12 | 23 | 26 | 37 | 40 |

| r1 | 13 | 16 | 27 | 38 | 41 | 52 | 63 | 2 |

| r2 | 39 | 42 | 53 | 56 | 3 | 14 | 17 | 28 |

| r3 | 57 | 4 | 15 | 18 | 29 | 32 | 43 | 54 |

| r4 | 19 | 30 | 33 | 44 | 55 | 58 | 5 | 8 |

| r5 | 45 | 48 | 59 | 6 | 9 | 20 | 31 | 34 |

| r6 | 7 | 10 | 21 | 24 | 35 | 46 | 49 | 60 |

| r7 | 25 | 36 | 47 | 50 | 61 | 0 | 11 | 22 |

| Key | Plaintext | Ciphertext |

|---|---|---|

| 00000000000000000000 | 0000000000000000 | DE9FDF0E3D278FAC |

| FFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF | 0000000000000000 | 27A8CFB6B8454F8C |

| E79B03D8F421A4C6F392 | 0000000000000000 | DB45FD06A3F47BFE |

| 00000000000000000000 | FFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF | CD1E6AF218910360 |

| FFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF | FFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF | 75EB4818D8943A55 |

| E79B03D8F421A4C6F392 | FFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF | 5796BB627D3CF1AE |

| 00000000000000000000 | C56B90AD3EF84712 | DFDD9B5CEE90F938 |

| FFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF | C56B90AD3EF84712 | 6859C245565B7B41 |

| E79B03D8F421A4C6F392 | C56B90AD3EF84712 | 3F7AAE3F7C0D3ADA |

| Result (R) | Correlation Strength |

|---|---|

| (R = 0) | No correlation (non-linear or random relationship) |

| (0 < R ≤ 0.3) or (–0.3 ≤ R < 0) | Weak positive/negative linear correlation |

| (0.3 < R < 0.7) or (–0.7 < R < –0.3) | Moderate positive/negative linear correlation |

| (0.7 ≤ R < 1) or (–1 < R ≤ –0.7) | Strong positive/negative linear correlation |

| (R = 1) or (R = –1) | Perfect positive/negative linear correlation |

| Result | Key 1 | Key 2 | Key 3 | Key 4 | Key 5 | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R = 0 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.8% |

| 0 < R ≤ 0.3 and −0.3 ≤ R < 0 | 97.7 | 96.9 | 96.2 | 96.3 | 96.5 | 96.7% |

| 0.3 < R ≤ 0.7 and −0.7 ≤ R < −0.3 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 1.5% |

| 0.7 ≤ R < 1 and −1 < R ≤ −0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0% |

| R = ±1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0% |

| Input | Average Different Bits | Average Bit Error Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Plaintext 1 | 31.765625 | 0.496338 |

| Plaintext 2 | 32.359375 | 0.505615 |

| Plaintext 3 | 32.109375 | 0.501709 |

| Plaintext 4 | 31.812500 | 0.497070 |

| Plaintext 5 | 32.000000 | 0.500000 |

| Average | 32.009 (≈50.01%) | 0.5001 (≈50.01%) |

| Algorithm | Average Avalanche Effect |

|---|---|

| SMA (proposed) | 50.02% |

| LAO-3D | 50.05% |

| LED | 52.83% |

| LRBC | 58.00% |

| PRINCE | 51.18% |

| 49.08% | |

| QTL | 52.56% |

| SIMECK | 53.00% |

| TEA | 49.12% |

| Input | Average Different Bits | Average Bit Error Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Key 1 | 33.500000 | 0.523438 |

| Key 2 | 31.050000 | 0.485156 |

| Key 3 | 32.725000 | 0.511328 |

| Key 4 | 31.787500 | 0.496680 |

| Key 5 | 32.525000 | 0.508203 |

| Average | 32.317 (≈50.50%) | 0.505 (≈50.50%) |

| Algorithm | Average Avalanche Effect |

|---|---|

| SMA (proposed) | 50.50% |

| LAO-3D | 50.00% |

| LED | 50.37% |

| LRBC | 55.75% |

| PRINCE | 49.06% |

| 46.42% | |

| QTL | 50.31% |

| SIMECK | 51.25% |

| TEA | 47.12% |

| No. | Data Category | Key Input | Plaintext Input | Derived Blocks | Derived Bits |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SKA | 196 random 80-bit keys | One all-zero 64-bit plaintext | 15,680 | 1,003,520 |

| 2 | SPA | One all-zero 80-bit key | 245 random 64-bit plaintext | 15,680 | 1,003,520 |

| 3 | PCC | 1 random 80-bit key | 15,625 random 64-bit texts | 15,625 | 1,000,000 |

| 4 | CBCM | 1 random 80-bit key | One all-zero 64-bit plaintext | 15,625 | 1,000,000 |

| 5 | RPRK | 1 random 80-bit key | 15,625 random 64-bit plaintext | 15,625 | 1,000,000 |

| 6 | LDK | 3241 specific 80-bit keys | 3241 random 64-bit texts | 3241 | 207,424 |

| 7 | HDK | 3241 specific 80-bit keys | 3241 random 64-bit texts | 3241 | 207,424 |

| 8 | LDP | 2081 random 80-bit keys | 2081 specific 64-bit texts | 2081 | 133,184 |

| 9 | HDP | 2081 random 80-bit keys | 2081 specific 64-bit texts | 2081 | 133,184 |

| Data Category | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Test | SKA | SPA | PCC | CBC | RPRK |

| Range of Acceptable Rejection: [0, 20] | |||||

| 1. Runs | 991/1000 | 989/1000 | 992/1000 | 990/1000 | 990/1000 |

| 2. Frequency | 988/1000 | 989/1000 | 992/1000 | 995/1000 | 989/1000 |

| 3. Spectral DFT | 989/1000 | 992/1000 | 990/1000 | 994/1000 | 986/1000 |

| 4. Block Frequency | 993/1000 | 994/1000 | 989/1000 | 988/1000 | 996/1000 |

| 5. Binary Matrix Rank | 991/1000 | 990/1000 | 987/1000 | 994/1000 | 991/1000 |

| 6. Approximate Entropy | 990/1000 | 990/1000 | 989/1000 | 986/1000 | 992/1000 |

| 7. Longest Runs of Ones | 991/1000 | 989/1000 | 987/1000 | 991/1000 | 989/1000 |

| 8. Serial | 992/1000 | 990/1000 | 993/1000 | 990/1000 | 991/1000 |

| 9. Cumulative Sums | 992/1000 | 990/1000 | 993/1000 | 994/1000 | 989/1000 |

| 10. Non-Overlapping Templates | 989/1000 | 990/1000 | 990/1000 | 990/1000 | 990/1000 |

| 11. Maurer’s Universal | 991/1000 | 994/1000 | 984/1000 | 983/1000 | 991/1000 |

| 12. Linear Complexity | 988/1000 | 990/1000 | 987/1000 | 990/1000 | 983/1000 |

| 13. Overlapping Templates | 990/1000 | 985/1000 | 988/1000 | 985/1000 | 990/1000 |

| Range of Acceptable Rejection: [0, 14] | |||||

| 14. Random Excursion | 608/613 | 621/628 | 632/639 | 620/627 | 594/600 |

| 15. Random Excursion Variant | 608/613 | 620/628 | 632/639 | 621/627 | 596/600 |

| Data Category | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Test | LDK | LDP | HDK | HDP |

| Range of Acceptable Rejection: [0, 20] | ||||

| 1. Runs | 990/1000 | 992/1000 | 989/1000 | 990/1000 |

| 2. Frequency | 988/1000 | 984/1000 | 988/1000 | 994/1000 |

| 3. Spectral DFT | 991/1000 | 990/1000 | 983/1000 | 988/1000 |

| 4. Block Frequency | 992/1000 | 991/1000 | 984/1000 | 991/1000 |

| 5. Binary Matrix Rank | 995/1000 | 988/1000 | 993/1000 | 982/1000 |

| 6. Approximate Entropy | 993/1000 | 985/1000 | 987/1000 | 989/1000 |

| 7. Longest Runs of Ones | 991/1000 | 995/1000 | 992/1000 | 992/1000 |

| 8. Serial | 989/1000 | 992/1000 | 989/1000 | 990/1000 |

| 9. Cumulative Sums | 988/1000 | 983/1000 | 991/1000 | 994/1000 |

| 10. Non-Overlapping Templates | 989/1000 | 989/1000 | 989/1000 | 988/1000 |

| 11. Maurer’s Universal | * | * | * | * |

| 12. Linear Complexity | * | * | * | * |

| 13. Overlapping Templates | * | * | * | * |

| Range of Acceptable Rejection: Not Available | ||||

| 14. Random Excursion | * | * | * | * |

| 15. Random Excursion Variant | * | * | * | * |

| Data Category | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Test | SKA | SPA | PCC | CBC | RPRK |

| 1. Runs | 0.214439 | 0.353733 | 0.428095 | 0.605916 | 0.056426 |

| 2. Frequency | 0.474986 | 0.518106 | 0.781106 | 0.316052 | 0.769527 |

| 3. Spectral DFT | 0.568739 | 0.263572 | 0.751866 | 0.825505 | 0.034484 |

| 4. Block Frequency | 0.520102 | 0.520102 | 0.595549 | 0.120207 | 0.643366 |

| 5. Binary Matrix Rank | 0.401199 | 0.837781 | 0.889118 | 0.296834 | 0.088762 |

| 6. Approximate Entropy | 0.350485 | 0.202268 | 0.973718 | 0.119508 | 0.786830 |

| 7. Longest Runs of Ones | 0.344048 | 0.203351 | 0.442831 | 0.645448 | 0.175691 |

| 8. Serial | 0.226954 | 0.482009 | 0.504306 | 0.274938 | 0.04512 |

| 9. Cumulative Sums | 0.565090 | 0.50017 | 0.460819 | 0.213319 | 0.729832 |

| 10. Non-Overlapping Templates | 0.501299 | 0.486167 | 0.458299 | 0.498877 | 0.526183 |

| 11. Maurer’s Universal | 0.572847 | 0.251837 | 0.197981 | 0.043087 | 0.065230 |

| 12. Linear Complexity | 0.454053 | 0.251837 | 0.961869 | 0.510153 | 0.796268 |

| 13. Overlapping Templates | 0.444691 | 0.616305 | 0.995969 | 0.204439 | 0.585209 |

| 14. Random Excursion | 0.424006 | 0.375151 | 0.495624 | 0.746409 | 0.311922 |

| 15. Random Excursion Variant | 0.462252 | 0.583549 | 0.478043 | 0.522233 | 0.657168 |

| Statistical Test | LDK | LDP | HDK | HDP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Runs | 0.220159 | 0.512137 | 0.032274 | 0.377007 |

| 2. Frequency | 0.684890 | 0.248014 | 0.635037 | 0.861264 |

| 3. Spectral DFT | 0.313041 | 0.072514 | 0.302657 | 0.467322 |

| 4. Block Frequency | 0.751866 | 0.777265 | 0.612147 | 0.463512 |

| 5. Binary Matrix Rank | 0.093720 | 0.006472 | 0.244236 | 0.030197 |

| 6. Approximate Entropy | 0.715679 | 0.715679 | 0.794391 | 0.723804 |

| 7. Longest Runs of Ones | 0.979788 | 0.271619 | 0.632955 | 0.214439 |

| 8. Serial | 0.226564 | 0.392515 | 0.084211 | 0.311564 |

| 9. Cumulative Sums | 0.408575 | 0.226505 | 0.463478 | 0.477629 |

| 10. Non-Overlapping Templates | 0.468405 | 0.470064 | 0.513858 | 0.517539 |

| 11. Maurer’s Universal | * | * | * | * |

| 12. Linear Complexity | * | * | * | * |

| 13. Overlapping Templates | * | * | * | * |

| 14. Random Excursion | * | * | * | * |

| 15. Random Excursion Variant | * | * | * | * |

| Round | Input Mask of S-Box | Output Mask of S-Box | Probability | Cumulative Probability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0000000000000001 | 0000000040080000 | 2−2 | 2−2 |

| 2 | 0000000040080000 | 2000000001200C80 | 2−4 | 2−6 |

| 3 | 2000000001200C80 | 0C82A81822000100 | 2−10 | 2−16 |

| 4 | 0C82A81822000100 | E229A3C01A83F808 | 2−20 | 2−36 |

| 5 | E229A3C01A83F808 | B3257F2B6A2AA649 | 2−31 | 2−67 |

| Round | Input Mask of S-Box | Output Mask of S-Box | Bias | Correlation Potentials |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0000000000000001 | 0000000200080000 | −2−2 | −2−2 |

| 2 | 0000000200080000 | 0008000001201402 | 2−4 | −2−6 |

| 3 | 0008000001201402 | 1925F488C2180200 | 2−12 | −2−18 |

| 4 | 1925F488C2180200 | 437F69393F6174CE | −2−26 | 2−44 |

| Algorithms | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMA | LAO-3D | GIFT | PRESENT | RECTANGLE | ||||||

| Attack | ||||||||||

| Round | DC | LC | DC | LC | DC | LC | DC | LC | DC | LC |

| 1 | 2−2 | 2−2 | 2−2 | 2−2 | 2−6 | 2−1 | 2−2 | 2−1 | 2−2 | 2−1 |

| 2 | 2−6 | 2−6 | 2−8 | 2−8 | 2−10 | 2−2 | 2−4 | 2−2 | 2−4 | 2−2 |

| 3 | 2−16 | 2−18 | 2−15 | 2−14 | 2−16 | 2−3 | 2−8 | 2−4 | 2−7 | 2−4 |

| 4 | 2−36 | * 2−44 | 2−27 | 2−20 | 2−20 | 2−5 | 2−12 | 2−6 | 2−10 | 2−6 |

| 5 | * 2−67 | – | 2−44 | 2−26 | 2−26 | 2−7 | 2−20 | 2−8 | 2−14 | 2−8 |

| 6 | – | – | * 2−64 | 2−32 | 2−30 | 2−10 | 2−24 | 2−10 | 2−18 | 2−10 |

| 7 | – | – | – | * 2−38 | 2−36 | 2−13 | 2−28 | 2−12 | 2−25 | 2−13 |

| 8 | – | – | – | – | 2−40 | 2−16 | 2−32 | 2−14 | 2−31 | 2−16 |

| 9 | – | – | – | – | 2−46 | 2−20 | 2−36 | 2−16 | 2−36 | 2−19 |

| 10 | – | – | – | – | 2−50 | 2−25 | 2−41 | 2−18 | 2−41 | 2−22 |

| 11 | – | – | – | – | 2−56 | 2−29 | 2−46 | 2−20 | 2−46 | 2−25 |

| 12 | – | – | – | – | 2−60 | 2−31 | 2−52 | 2−22 | 2−51 | 2−28 |

| 13 | – | – | – | – | * 2−64 | * 2−34 | 2−56 | 2−24 | 2−56 | 2−31 |

| 14 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2−62 | 2−26 | 2−61 | * 2−34 |

| 15 | – | – | – | – | – | – | * 2−66 | 2−28 | * 2−66 | – |

| 16 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2−30 | – | – |

| 17 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2−32 | – | – |

| 18 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | * 2−34 | – | – |

| Rounds | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Algorithm | Attack | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| SMA | DC | 1 | 2 | 5 | 10 | * 14 | – | – | – | – |

| LC | 1 | 2 | 6 | * 13 | – | – | – | – | – | |

| LAO-3D | DC | 1 | 3 | 6 | 11 | 17 | * 25 | – | – | – |

| LC | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 11 | * 13 | – | – | |

| GIFT | DC | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 13 | 16 | 18 |

| LC | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 12 | 15 | 18 | |

| PRESENT | DC | 1 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 10 | 12 | 14 | 16 | 18 |

| LC | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

| RECTANGLE | DC | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 11 | 13 | 14 |

| LC | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 12 | 14 | |

| Algorithm | SMA | RECTANGLE | KLEIN | LAO-3D | PRESENT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block Size (bit) | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 |

| Key Size (bit) | 80 | 80 | 80 | 128 | 80 |

| Rounds | 20 | 25 | 16 | 20 | 31 |

| Encryption Algorithm Components | 1. AddRound Key 2. SubNibble 3. Two-Dimensional Matrix Permutation | 1. AddRound Key 2. Substitution S-layer 3. Bit Permutation | 1. Sub Nibble 2. Rotate Nibble 3. Mix Nibble | 1. AddRound Key 2. Sub Column S-box 3. 3DRotation | 1. AddRound Key 2. Substitution S-box 3. Permutation |

| Encryption Speed (µs per block) | 0.200 | 0.300 | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.600 |

| Encryption Throughput (byte per second) | 34,770,055.19 | 24,497,646.66 | 16,514,405.91 | 15,836,964.78 | 13,957,267.38 |

| Encryption Throughput (block per second) | 4,346,256.90 | 3,062,205.83 | 2,064,300.74 | 1,979,620.60 | 1,744,658.42 |

| Cycles per Byte | 51.7974 | 73.5173 | 109.0563 | 113.7213 | 129.0367 |

| Cycles per Block | 414.3796 | 588.1381 | 872.4504 | 909.7703 | 1,032.2938 |

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| ROM usage | 260,755 bytes (≈254.7 KB) |

| RAM usage | 118,160 bytes (≈115.4 KB) |

| Platform | Contiki-NG + Cooja |

| Evaluation level | System-level |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Al-Nofaie, S.M.; Sharaf, S.; Molla, R. The SMA: A Novel 2D Matrix-Based Lightweight Block Cipher for IoT Security. Electronics 2026, 15, 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010172

Al-Nofaie SM, Sharaf S, Molla R. The SMA: A Novel 2D Matrix-Based Lightweight Block Cipher for IoT Security. Electronics. 2026; 15(1):172. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010172

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Nofaie, Safia Meteb, Sanaa Sharaf, and Rania Molla. 2026. "The SMA: A Novel 2D Matrix-Based Lightweight Block Cipher for IoT Security" Electronics 15, no. 1: 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010172

APA StyleAl-Nofaie, S. M., Sharaf, S., & Molla, R. (2026). The SMA: A Novel 2D Matrix-Based Lightweight Block Cipher for IoT Security. Electronics, 15(1), 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010172