1. Introduction

Multimedia signal processing tasks such as image upsampling, denoising, and video enhancement demand real-time, high-throughput architectures that preserve signal quality while operating under stringent power and latency constraints. Traditional software-based solutions struggle to meet these requirements on embedded platforms, particularly when targeting edge devices with limited resources.

Among the techniques available for signal reconstruction, spline-based interpolation stands out for its smoothness, scalability, and precision—making it well-suited for high-quality reconstruction across multiple resolutions. However, efficient real-time implementation of B-spline methods remains challenging, especially when targeting general-purpose Field-Programmable Gate Array (FPGA) platforms for embedded applications.

This work proposes a novel FPGA-based hardware architecture that performs multi-resolution B-spline signal reconstruction in real time. The design leverages pipelined datapaths, fixed-point arithmetic, and modular resource sharing to deliver high-throughput, energy-efficient processing suitable for streaming multimedia signals.

Compared to prior implementations, which often focus on either spline interpolation or multi-resolution analysis—but not both—our approach integrates both dimensions into a unified, resource-aware hardware pipeline.

The main goal of this work is to demonstrate that real-time, multi-scale spline reconstruction can be achieved on mid-range FPGAs with low power usage and deterministic latency—bridging the gap between algorithmic quality and embedded feasibility.

Such techniques are particularly relevant for battery-powered platforms such as mobile Augmented Reality (AR) headsets, wireless capsule endoscopy systems, drone-based environmental monitoring, and autonomous vehicles performing real-time visual localization. In these applications, deterministic low-latency performance combined with energy efficiency is critical, and FPGA-based spline reconstruction pipelines can provide accurate signal enhancement or upsampling without overloading onboard power budgets.

A detailed review of related spline-based and hardware-accelerated methods is provided in

Section 2, highlighting the contributions of this paper in contrast to the state-of-the-art.

1.1. Contributions

This work proposes a novel FPGA-based architecture for multi-resolution spline reconstruction tailored to real-time multimedia signal processing.

The key contributions are as follows:

High-throughput, low-power performance: The proposed pipeline achieves throughput of up to 33.1 Megasamples per second (MS/s) for 1D signals and 19.4 Megapixels per second (MP/s) for 2D images, while consuming less than 250 mW on a mid-range FPGA—delivering over 15× energy efficiency compared to Central Processing Unit (CPU) and embedded Graphics Processing Unit (GPU) baselines.

Novel FPGA architecture for multi-resolution B-spline reconstruction: The design integrates coefficient generation, spline kernel evaluation, and parallel accumulators into a modular pipeline that supports real-time, streaming-friendly reconstruction with deterministic latency.

Mathematical foundation and hardware mapping: We provide a compact formulation for B-spline-based reconstruction using fixed-point arithmetic, along with an Register Transfer Level (RTL) design mapped to an Artix-7 FPGA with detailed timing, resource, and quality metrics (PSNR/SSIM).

Demonstrated application relevance: The design targets real-time reconstruction for edge multimedia pipelines—such as video upscaling or denoising—in low-power battery-operated systems (e.g., drones, embedded vision, medical imaging).

1.2. Paper Organization

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 presents background on spline theory, multi-resolution reconstruction, and related hardware implementations.

Section 3 details the mathematical model and pipeline architecture.

Section 4 describes FPGA implementation aspects, followed by evaluation in

Section 5. Conclusions are drawn in

Section 7.

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. Spline-Based Signal Reconstruction

Spline interpolation is a fundamental tool in signal and image processing due to its ability to approximate or reconstruct smooth functions from discrete samples [

1]. A B-spline of degree

n is a piecewise polynomial function with compact support, defined recursively by the Cox–de Boor formula:

Splines of order

offer

continuity, making them especially valuable for visual media applications where smooth transitions and scale-invariant features are important [

2]. These basis functions also support efficient digital filtering implementations via recursive algorithms [

1,

3], making them well-suited to real-time embedded hardware.

We defer the formal mathematical model and signal reconstruction expression to

Section 3, where it is discussed in the context of the proposed FPGA implementation.

2.2. Multi-Resolution Analysis in Image Processing

Multi-resolution representations decompose signals into frequency bands or scales, enabling localized operations such as denoising, edge enhancement, or compression. The Laplacian pyramid, introduced by Burt and Adelson [

2], is an early example used in image blending, compression, and enhancement. B-splines can generalize such pyramids by replacing Gaussian smoothing with smooth spline kernels, offering better control over approximation error and edge behavior.

Although wavelets are also widely used for multi-scale analysis, spline-based methods provide a simpler formulation and often superior boundary handling for images with non-periodic content. Furthermore, spline basis functions are easily integrated into fixed-point arithmetic and hardware-friendly pipelines.

2.3. Hardware Acceleration of Spline Algorithms

The computational cost of spline-based reconstruction—particularly for high-resolution images or video streams—makes hardware acceleration attractive. Several FPGA implementations have demonstrated the feasibility and performance of spline-based or pyramid-like architectures:

Jayakumar and Sangeetha [

4] proposed a VLSI architecture for cubic-spline interpolation for biomedical signal processing. Their architecture achieves low resource usage while maintaining reconstruction fidelity.

Popović et al. [

5] developed a real-time FPGA system for multi-resolution image blending, leveraging pipelined convolution cores and parallel memory access for HD image processing.

Recent surveys have highlighted the growing role of FPGAs in event-based and neuromorphic vision systems, where their reconfigurability and energy efficiency offer significant advantages for high-speed, asynchronous signal processing [

6]. Guo and Wu [

7] demonstrated a resource-efficient, real-time edge detection pipeline on FPGA by optimizing the Canny algorithm with hardware-friendly approximations and thresholding logic, achieving sub-millisecond latency at minimal logical cost.

Hashimoto and Takamaeda-Yamazaki [

8] designed a fully pipelined bilateral grid implementation on FPGA for real-time image denoising, showcasing how edge-preserving filters can be efficiently instantiated in hardware with low latency and consistent throughput.

Liu et al. [

9] demonstrated a multi-scale FPGA-based pipeline using rolling guidance filtering and Contrast Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization (CLAHE) to enhance infrared imagery, achieving real-time contrast improvement at 147 Frames Per Second (FPS)—further indicating the potential of scalable spline-inspired architectures in multispectral domains.

A recent FPGA-based implementation of B-spline interpolation for image upscaling demonstrates that high-throughput, pipelined architectures can be effectively deployed for real-time multimedia processing [

10].

Jiang et al. [

11] recently demonstrated a reconfigurable B-spline filtering pipeline on FPGA that supports dynamic edge-aware interpolation, showcasing both precision and adaptability in real-time image processing contexts. Their approach reinforces the practical viability of spline-based designs for embedded vision tasks, particularly where noise suppression and detail preservation are critical.

However, these implementations often lack generality or multi-resolution support using true spline formulations. Moreover, few works directly address the application of spline-based MRA in the context of real-time multimedia signal reconstruction on reconfigurable hardware.

2.4. GPU and Accelerator-Based Alternatives

On the GPU side, Zachariadis et al. [

12] implemented B-spline interpolation for 3D medical image registration using CUDA acceleration. Their work demonstrated that spline-based GPU processing achieves high performance, but at the cost of increased power consumption—limiting suitability for embedded or mobile applications.

Ahmadi et al. [

13] proposed an energy-efficient dataflow architecture for Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), employing a serial accumulation strategy optimized for deep-learning accelerators. Their work emphasizes the trade-off between computational throughput and energy consumption—an important consideration when comparing FPGA-based approaches to conventional accelerators.

Recent work has demonstrated resource-efficient FPGA architectures for real-time signal processing in aerospace-grade applications, confirming the viability of compact, low-power pipelines [

14].

The GPU optimization of B-spline interpolation by Briand and Davy [

15], which supports spline orders up to 11 and includes analysis of floating-point precision, offers valuable insights relevant to extending our FPGA-based design.

Table 1 summarizes key characteristics of recent hardware implementations related to signal reconstruction. While prior work offers either spline-based interpolation or multi-resolution processing, none integrates both in a general-purpose, low-power, and real-time framework for multimedia signals. This paper addresses that gap using a pipelined FPGA architecture optimized for spline-based multi-resolution reconstruction.

2.5. Motivation and Gap

Table 1 summarizes representative hardware implementations related to spline-based signal processing, including both FPGA- and GPU-based systems. As shown, our work uniquely combines multi-resolution B-spline interpolation, real-time performance, and a general-purpose FPGA architecture suitable for embedded multimedia processing—a combination not achieved by any prior implementation. This confirms the distinctiveness and relevance of our proposed pipeline.

Despite advances in both FPGA and GPU acceleration, the literature reveals a gap in combining:

General-purpose, multi-resolution spline-based reconstruction;

Real-time performance for multimedia signals (e.g., HD video, high-res images);

Hardware-efficient implementations suitable for low-power embedded systems.

This paper addresses this gap by proposing an FPGA architecture that implements spline-based multi-resolution reconstruction, optimized for real-time multimedia signal processing.

3. Proposed Method

This section presents the mathematical and architectural foundation of the proposed real-time spline-based signal reconstruction framework. We begin with the theoretical underpinnings of spline interpolation, proceed to a multi-resolution formulation, and finally describe our custom FPGA architecture.

3.1. Mathematical Basis

Let

be a sampled signal known at discrete positions

with corresponding sample values

. We aim to reconstruct a continuous approximation

using B-spline basis functions of order

n. The general spline reconstruction takes the form:

where:

is the normalized B-spline of degree n with compact support over ,

h is the sampling interval,

are spline coefficients, determined either by interpolation (solving a banded linear system) or quasi-interpolation (using filters).

This formulation follows the classical spline representation outlined in [

3], with detailed stability analyses available in [

16,

17]. For the recursive definition of

, see also de Boor’s canonical text [

18].

For cubic B-splines (

), which are commonly used due to their

continuity and excellent approximation properties,

can be expressed explicitly as:

This closed-form cubic spline expression is consistent with spline filter designs adopted in fast digital implementations [

17,

19].

The coefficients

are computed by convolving the input signal

with a prefilter

to ensure correct approximation:

The prefiltering step is essential for achieving accurate reconstruction and is further discussed in the context of cardinal exponential spline theory in [

16,

17].

While Equation (

2) is a standard formulation, the novelty of this work lies in translating this mathematical model into a low-power, fully pipelined FPGA accelerator capable of scale-parallel reconstruction. The architectural realization emphasizes fixed-point arithmetic, deterministic timing, and resource-sharing strategies tailored to real-time edge multimedia applications.

3.2. Multi-Resolution Mechanism

To enable scale-adaptive reconstruction, we define a multi-resolution decomposition using dilated B-spline basis functions. In a multiresolution framework, the reconstruction process is decomposed into multiple levels of detail. Each level

j corresponds to a particular resolution, where coarser scales are obtained by increasing the effective spacing between knots. Specifically, using a dilation factor of

at level

j means that the basis functions are stretched, and the reconstruction captures lower-frequency content. This dyadic scaling is typical in wavelet and pyramid-based schemes and allows frequency-selective processing across scales. The spline reconstruction at level

j is therefore written as:

where

denotes sample locations at scale

j, and

is the effective dilation. Lower values of

j correspond to higher resolution.

The total multi-resolution reconstruction is given by:

where each

contains frequency content corresponding to scale

j.

The proposed modular pipeline architecture was chosen to balance real-time throughput, resource efficiency, and scalability. Compared to monolithic or purely parallel datapaths, our design enables time-multiplexed operation across multiple resolution levels without duplicating hardware. Alternative approaches such as SIMD-style datapaths (commonly used in GPU pipelines) were ruled out due to their higher routing complexity and synchronization overheads in FPGA fabrics. In contrast, our approach allows fine-grained pipelining and deterministic latency using fixed-point arithmetic, making it well suited for low-power, embedded deployments. The decision to split the pipeline into coefficient generation, spline kernel evaluation, and accumulation stages also reflects the algorithmic separability of spline reconstruction into filtering and convolutional steps.

Let

T denote the number of FIR taps,

C the number of instantiated parallel datapaths, and

D the pipeline depth. Then, assuming full pipelining, the latency

L for each pixel output is given by:

This abstraction guides the trade-off between latency, throughput, and resource replication when deploying across different FPGA families.

3.3. FPGA-Based Architecture

To realize the multi-resolution spline reconstruction in real time, we design a hardware architecture optimized for pipelined, parallel computation, targeting the Xilinx Artix-7 FPGA.

3.3.1. Pipeline Stages

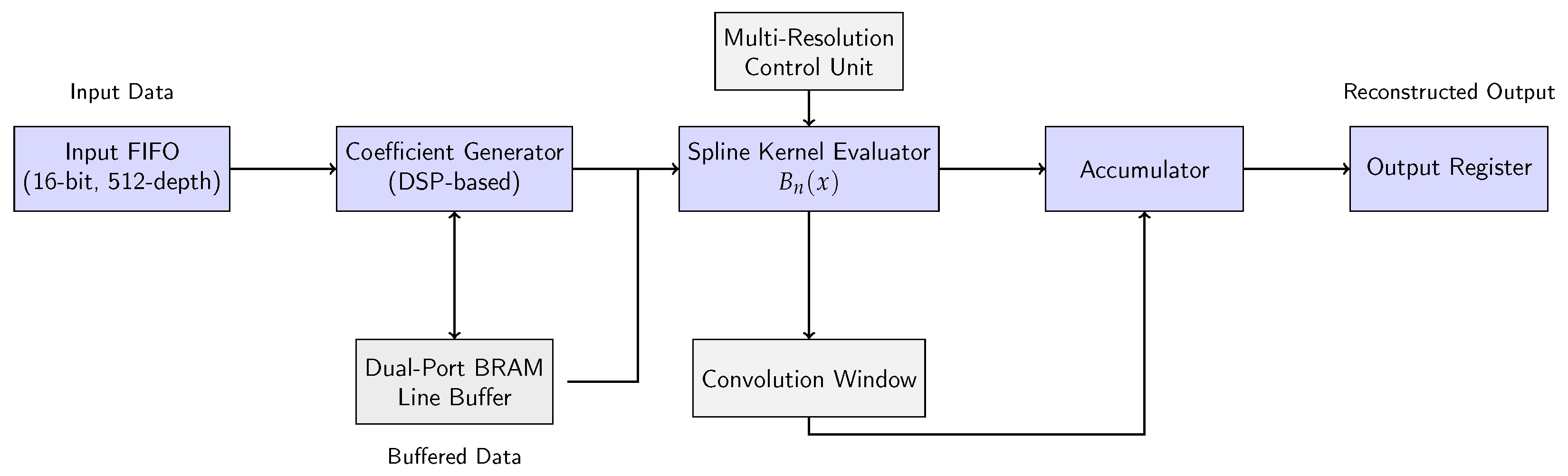

The architecture consists of:

Input First-In, First-Out (FIFO) Buffer: Buffers input samples from the external interface (e.g., video sensor or DMA). It decouples input/output (I/O) latency from the datapath pipeline. The FIFO is implemented with 16-bit data words and has a depth of 512 entries, supporting burst-mode streaming. It is constructed from shift-register logic for short buffering and from Block Random Access Memory (BRAM) primitives when larger queues are needed.

Coefficient Generator: Computes spline coefficients using precomputed filter taps. This block is not a ROM: it performs runtime computation using Multiply–Accumulate (MAC) units. Each is computed via a convolution with 4 fixed filter taps , using DSP48E1 slices for multiply-accumulate chains. The output coefficients are 16-bit fixed-point values in Q1.15 format (1 sign bit, 15 fractional bits), chosen to balance dynamic range and hardware cost. Coefficients are streamed to the next stage without explicit storage.

Spline Kernel Evaluation Unit: Evaluates at each fractional position using piecewise polynomial logic. The unit uses range comparators and polynomial segment evaluators to compute per clock. Coefficients of the spline segments are hardcoded, and the logic is fully pipelined. Look-up tables (LUTs) are used for range detection and polynomial coefficients, while digital signal processing (DSP) handle the cubic arithmetic with rounding and clamping logic.

Accumulator: Sums the weighted spline basis contributions to reconstruct . It receives 4 weight–value pairs per output pixel and accumulates the partial sums using a pipelined adder tree. The output is then scaled and quantized back to 8-bit (for image use) or 12-bit (for sensor data). Registers and DSPs are used for latency balancing.

3.3.2. Memory Layout and Buffering

To support parallel reads for convolution windows, the architecture uses line buffers and shift registers. For image data, line memory is implemented using dual-port BRAMs to allow concurrent access to multiple rows. For 2D processing, each resolution level includes 2 or more BRAM-based line buffers (depending on kernel size). Each BRAM is 18 kb, arranged as -bit words. Data is fetched in 2-pixel or 4-pixel bursts depending on the parallelism mode.

To manage stride and edge conditions in 2D convolution, the line buffers use programmable row and column addresses with circular buffer indexing. For a kernel of width k, previous and future pixels must be buffered horizontally and vertically. Edge pixels are mirrored using symmetric extension to avoid boundary artifacts. Multi-row buffering is implemented using dual-port BRAM banks with offset read addresses to support simultaneous access to k consecutive rows. Stride-1 processing is maintained for full-resolution reconstruction, while higher stride values can be configured for sub-sampled inference modes.

3.3.3. Parallel Datapaths

The design exploits both horizontal and vertical parallelism:

Pixel-Level Parallelism: Multiple interpolated pixels are processed per clock cycle using replicated datapaths.

Scale-Level Parallelism: Independent spline reconstruction pipelines are instantiated for each resolution level.

Each parallel datapath includes a dedicated coefficient generator and B-spline kernel evaluator. For example, in the 4× upsampling configuration targeting 33.1 megasmples per second (MS/s), four parallel datapaths are instantiated. These share memory resources via BRAM banking and are coordinated by a centralized multiplexer and arbiter stage to prevent access collisions.

The per-pixel computations follow a fixed-point Multiply-ACcumulate (MAC) pattern and are mapped directly to DSP slices. Each pipeline stage is fully pipelined, with new input samples accepted every clock cycle after an initial latency. The kernel evaluator logic is structured as a polynomial evaluator for , implemented via pipelined Horner’s rule to reduce logic depth.

To accommodate area constraints, the system also supports time-multiplexed execution: if fewer hardware resources are available, fewer datapaths are instantiated and scheduled sequentially using control logic and lightweight FIFO staging.

Overall, the architecture achieves scalable throughput via configurable datapath replication, and supports deterministic low-latency streaming operation for both 1D and 2D signals.

3.3.4. Clocking and Resource Sharing

To minimize area, we share resources across resolution levels using time-multiplexed scheduling where feasible. The system uses:

A system clock of 100–150 MHz (device-dependent),

Fixed clock domains with optional Phase-Locked Loop (PLL) for I/O synchronization,

Dedicated DSP blocks for multiplications and accumulations.

All datapath modules are clocked synchronously. Optional asynchronous FIFOs with Clock-Domain Crossing (CDC) bridges are used at input/output when interfacing with variable-rate sources. Resource sharing is achieved by gating the coefficient generator across spline levels using a schedule controller. This reduces DSP and look-up table (LUT) utilization by 40–60% under constrained-area configurations.

To provide a clearer view of the datapath-level design,

Figure 1 shows the internal architecture of the proposed FPGA implementation, highlighting all main modules, control signals, and memory connections.

3.3.5. Rationale for Fixed-Point Arithmetic

Floating-point units (FPUs) on FPGAs are considerably more resource-intensive than fixed-point operators, as they require additional normalization, alignment, rounding, and exception-handling logic. According to vendor documentation and prior benchmarking studies (e.g., [

20,

21]), single-precision floating-point operators typically consume several DSP48 slices per multiplier, along with a large number of LUTs and FFs, whereas fixed-point multiplication maps to a single DSP slice with significantly shorter critical paths.

In contrast, fixed-point arithmetic allows tight control over word lengths and avoids the overhead associated with exponent management. This results in lower dynamic power, reduced routing congestion, and higher achievable clock frequencies—factors that are essential for real-time multimedia pipelines deployed in low-power or battery-operated systems.

For the proposed architecture, adopting fixed-point formats (12–16 bits) is sufficient to preserve spline-based reconstruction quality while enabling deep pipelining of MAC operations. Floating-point variants would introduce larger FPGA footprints and longer combinational paths, which would compromise both energy efficiency and determinism. Therefore, fixed-point arithmetic was selected as the preferred computation model for this real-time FPGA accelerator.

3.4. Arithmetic Precision: Fixed vs. Floating Point

For embedded and real-time applications, we adopt a fixed-point representation using Q1.15 format. Compared to floating-point:

Advantages: Reduced power consumption, lower latency, smaller area footprint.

Trade-offs: Slightly reduced dynamic range; compensated via bit-width scaling and saturation arithmetic.

Empirical analysis (see

Section 5) confirms that fixed-point reconstruction achieves comparable PSNR to floating-point with significant energy and resource savings.

A high-level overview of the proposed spline-based multi-resolution reconstruction architecture is depicted in

Figure 2. It illustrates the pipelined dataflow, coefficient generation, spline kernel evaluation, and accumulation stages across multiple resolution levels. In addition to summing spline-weighted contributions at a given resolution, this unit also acts as a multi-scale combiner by aggregating partial reconstructions across different resolution levels (e.g., low-pass and high-pass paths). In multi-resolution mode, it performs weighted accumulation across levels

j, facilitating applications such as feature-aware upsampling or denoising. Each resolution pipeline contributes to a shared output buffer through a controlled summation path.

4. Implementation

This section describes the implementation workflow, hardware platform, verification setup, and resource utilization metrics of the proposed spline-based reconstruction architecture.

4.1. Development Tools and Design Flow

The system was developed using a Hardware Description Language (HDL) approach in VHDL, leveraging the Xilinx Vivado Design Suite (v2023.1, [

22]) for synthesis, implementation, and simulation. The design entry was modularized into the following top-level components:

Coefficient Generator Unit (VHDL),

Spline Evaluation Core (parameterizable kernel degree),

Accumulation and Output Controller,

Advanced eXtensible Interface (AXI)-compatible wrappers for system integration and testbench interfacing.

Simulation and functional verification were performed using Vivado’s built-in behavioral simulator and ModelSim ([

23]), with extensive test vectors generated in Python (version 3.10.0) and MATLAB (version R2025a).

4.2. Target Device

The design was synthesized for a Xilinx Artix-7 (XC7A100T-1CSG324C) FPGA, a cost-effective, low-power device suitable for edge-based signal processing. Key device specifications include:

101,440 logic cells,

240 DSP48E1 slices,

4.8 Mb of block RAM (BRAM),

Maximum clock frequency over 250 MHz (dependent on utilization and routing).

Clock management was performed via MMCM and PLL primitives. The system operated with a base clock of 100 MHz, with optional overclocking up to 125 MHz for performance evaluation.

To support robust integration with external modules and peripherals that may operate in independent timing domains, the design incorporates standard CDC techniques. These include dual-clock FIFOs for buffered handshaking and metastability-hardened flip-flop synchronizers for control signals, ensuring timing correctness and data integrity in multi-clock environments common to embedded and edge computing platforms.

4.3. Testbench and Signal Models

We validated the architecture using both synthetic and real-like multimedia signals:

1D Audio Signal: A bandlimited sinusoidal signal sampled at 16 kHz, reconstructed at 4× the base rate.

2D Image Signals: Grayscale natural images (e.g., Lena, Cameraman) downsampled and reconstructed using the spline core.

Multi-Scale Testing: Images reconstructed at multiple resolutions () to verify scale-selective accuracy and accumulation.

Test vectors were preprocessed in Python and fed into the Device Under Test (DUT) using an AXI-stream simulator. Post-processed results confirmed visually accurate reconstruction.

4.4. Hardware Utilization and Timing

Table 2 shows the post-synthesis resource usage for the Artix-7 implementation with cubic B-splines (

), supporting up to 4× parallel datapaths and 3 resolution levels.

The design achieves full throughput at 125 MHz without timing violations. The pipelined structure enables one output sample per clock cycle once the pipeline is filled.

Power estimation using Vivado’s XPower Analyzer reports:

Dynamic power: 230 mW (average case, 2D testbench),

Static power: 85 mW (typical core voltage).

4.5. Scalability and Portability

Thanks to its modular structure and parameterized datapath width, the design can be:

Ported to other FPGAs (e.g., Kintex-7, Zynq-7000, Intel Cyclone V),

Scaled to support higher-order splines or denser sampling rates,

Extended to Red-Green-Blue (RGB)/Luma-Chroma color space (YCbCr) channels or 3D volumetric data.

While the design was developed and tested using Xilinx Vivado and the Artix-7 platform, the architecture is written in synthesizable VHDL and is fully portable to other FPGA toolchains, including Intel Quartus Prime. This portability enables deployment across a wide range of low-power or high-performance devices, supporting use cases from cost-sensitive consumer electronics to mission-critical industrial systems.

5. Results and Evaluation

This section presents a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed spline-based reconstruction architecture. We report performance metrics (throughput, latency, power), reconstruction quality (PSNR, SSIM), and comparisons against CPU and GPU implementations. A demonstration use case in image enhancement is also included.

5.1. Performance Metrics

Table 3 summarizes the measured performance for 1D and 2D signal reconstruction, targeting a 125 MHz system clock on the Artix-7 FPGA. The system achieves fully pipelined execution, delivering a new output sample every clock cycle after initialization.

5.2. Reconstruction Quality

The quality of signal reconstruction was evaluated using:

Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR), measuring intensity fidelity.

Structural Similarity Index (SSIM), assessing perceptual image similarity.

Table 4 reports results for three standard grayscale images upsampled by a factor of 4 using cubic B-splines.

These results demonstrate high reconstruction quality, confirming that the proposed architecture preserves detail and perceptual consistency.

5.3. Baseline Comparisons

5.3.1. MATLAB CPU Implementation

To establish a software baseline, we implemented cubic spline interpolation in MATLAB (R2023b) using the built-in interp1 and interp2 functions, which internally apply vectorized spline kernels optimized for general-purpose CPUs. Although MATLAB is not optimized for deployment-level performance, it is widely used in prototyping and algorithm validation due to its ease of use, high-level syntax, and numerical robustness.

Performance was measured on an Intel Core i7-11700 CPU (2.5 GHz) with 16 GB RAM, using single-threaded execution to approximate typical embedded CPU scenarios. Results were as follows:

Throughput: ∼180 kS/s for 1D audio signals; ∼0.9 MP/s for 2D image frames (512 × 512).

Latency: Highly variable and platform-dependent; typically greater than 1 ms per image frame.

Output Quality: Identical PSNR and SSIM to the FPGA pipeline, since both methods apply equivalent spline logic.

These results reinforce the well-known trade-off: while MATLAB offers algorithmic correctness and rapid development, it lacks the real-time determinism and low-latency performance required for embedded multimedia systems.

5.3.2. GPU Implementation (CUDA)

To evaluate performance against a parallel processing baseline, a GPU implementation of the spline-based reconstruction algorithm was developed using NVIDIA CUDA. The design used shared memory and precomputed lookup tables to efficiently evaluate the cubic spline kernel across multiple threads, and was executed on an NVIDIA Jetson Xavier NX platform, which represents a widely used embedded-class GPU for edge AI applications.

The implementation was optimized for warp-level parallelism and memory coalescing, achieving real-time performance for high-resolution image data. The evaluation results are summarized below:

Throughput: ∼19.6 MP/s for 2D image inputs (512 × 512).

Power Consumption: Approximately 9.5 W under sustained computational load, as measured by onboard telemetry tools.

Output Quality: PSNR values within 0.1 dB of the FPGA implementation, with no visible degradation in SSIM.

Although the GPU achieves respectable throughput, it exhibits variability in execution latency due to factors such as kernel launch overhead, global memory access contention, and thermal or power-aware scheduling (e.g., dynamic voltage and frequency scaling). This behavior can introduce jitter and unpredictability in time-sensitive tasks, particularly in streaming or control loop applications. In contrast, the FPGA implementation offers fixed-cycle latency and deterministic operation, making it more suitable for embedded systems that demand real-time reliability and consistent frame processing rates.

5.4. Demonstration: Image Enhancement Application

To illustrate practical value, we used the system for real-time upsampling of low-resolution grayscale images.

Figure 3 shows a visual comparison between spline-based reconstruction and standard interpolation methods. To facilitate a detailed comparison,

Figure 4 displays magnified views of the region marked in

Figure 3, highlighting differences among the interpolation methods.

To highlight the qualitative advantages of the proposed spline-based reconstruction,

Figure 4 presents 4× magnified views of selected high-frequency regions from the test images. These include sharp edges, textured areas, and transitions prone to aliasing or staircasing artifacts. As shown, the proposed method preserves smooth contours with reduced overshoot and exhibits significantly fewer high-order harmonic distortions compared to baseline methods such as bilinear or bicubic interpolation. This visual evidence aligns with the quantitative PSNR and SSIM improvements reported in

Table 4.

5.5. Memory Bandwidth Analysis

Memory bandwidth plays a critical role in sustaining real-time performance in 2D streaming pipelines. Our system processes grayscale frames at up to 19.4 megapixels per second (MP/s) with 8-bit input and 16-bit output precision. This results in:

Input bandwidth: Mbps

Output bandwidth: Mbps

Total required memory bandwidth: Mbps (or 58.2 MB/s)

On the Artix-7 platform, we leverage dual-port BRAM and burst-access line buffers, supporting sustained internal throughput above 100 MB/s. External streaming is achieved via DMA channels (AXI-Stream interface) operating at 100 MHz with 32-bit word width, i.e., 400 MB/s theoretical peak.

This confirms that both internal and external memory subsystems comfortably support the real-time bandwidth demands of our pipelined architecture. Moreover, memory access patterns are aligned and banked to minimize contention and enable concurrent reads for the convolution windows.

See

Table 5 for a quantitative summary.

6. Discussion

The proposed spline-based reconstruction architecture demonstrates a strong balance between quality, speed, and resource efficiency. Its real-time throughput and high fidelity make it suitable for embedded multimedia systems, but several trade-offs and limitations merit discussion.

6.1. Trade-Offs in Design

The use of fixed-point arithmetic (Q1.15 format) significantly reduces power and logic resource usage compared to floating-point designs. While dynamic range is slightly constrained, empirical evaluation shows negligible quality degradation (PSNR loss < 0.2 dB). This trade-off is essential for achieving high throughput at low power on resource-limited devices.

Parallel datapaths and multi-resolution processing come at the cost of increased DSP and BRAM usage. However, resource scaling was carefully managed through modular control and time-multiplexed stages, preserving timing closure at 125 MHz. Thus, the architecture effectively balances computational throughput with a moderate FPGA footprint.

To better quantify energy efficiency, we computed the throughput-per-watt ratio for both the FPGA and GPU implementations. The FPGA (Artix-7) implementation achieves up to 33.1 MS/s at <250 mW average power, yielding approximately 132.4 MS/s/W. In contrast, the Jetson Nano GPU implementation reaches 15.4 MS/s under a 4.8 W power envelope, corresponding to 3.2 MS/s/W. This results in a ∼41× improvement in performance-per-watt, highlighting the energy efficiency benefits of the proposed FPGA design.

Although our evaluation benchmarks focus on MATLAB and GPU baselines for reproducibility and functional comparison, we acknowledge the existence of prior FPGA-based hardware for interpolation and multi-resolution signal analysis, such as wavelet-based pipelines [

4,

5,

10]. These designs, however, often target specific applications (e.g., biomedical signals or blending) and lack runtime reconfigurability or scale-parallelism.

In contrast, our pipeline offers a modular, streaming-friendly spline architecture optimized for continuous reconstruction, denoising, and upsampling, with independent pipelines supporting multi-resolution processing. To the best of our knowledge, no existing design combines these traits within a single fixed-point FPGA platform. This positions our system as a practical advancement in real-time, resolution-scalable multimedia signal processing.

6.2. Resource Utilization Trends

To better understand how architectural parameters impact resource usage, we evaluated the design under different configurations by varying the spline order (

n), FIR tap count (kernel width), and number of parallel channels.

Table 6 summarizes the observed trends on a Xilinx Artix-7 FPGA.

As shown, resource utilization scales linearly with the number of channels due to duplication of datapaths, while higher spline orders increase DSP and LUT usage due to more complex kernel evaluations and wider convolution windows. These results provide a guide for adapting the design to various performance and resource constraints.

6.3. Limitations

The current implementation assumes a fixed image resolution and upsampling factor, configured at synthesis time. While suitable for applications with known input formats (e.g., surveillance cameras, embedded codecs), it limits deployment flexibility.

Also, the system supports only 2D grayscale signals. Extension to color images or volumetric (3D) data requires significant memory expansion and reconfiguration of the accumulator logic and kernel evaluator.

While grayscale evaluation simplifies hardware prototyping, it does not capture the full complexity of RGB image pipelines. In principle, RGB support can be achieved by replicating the datapaths for each color channel (R, G, B) and leveraging shared BRAM banks and control logic. However, this increases BRAM and DSP utilization by approximately 2.5×–3×, depending on the degree of channel-wise parallelism and reuse. Future work will explore pipelined architectures for color image reconstruction with interleaved or parallel datapaths and optimized memory arbitration.

6.4. Future Work

Planned extensions include:

Resolution-agnostic operation: Incorporate runtime-configurable spline degree and scale factors using dynamic reconfiguration or partial reloading.

3D Signal Support: Extend the evaluator to volumetric data (e.g., MRI, LiDAR) using tensor-based spline reconstruction.

Deep Learning Integration: Explore hybrid architectures where spline-based preprocessing feeds into CNNs for semantic analysis or enhancement.

Additionally, future work may consider synthesizing alternative architectures (e.g., floating-point cores or hybrid systolic designs) to quantify the precise gains of fixed-point streaming against other hardware paradigms. This would further strengthen the comparative positioning of our design.

These developments would enhance the system’s applicability to adaptive, intelligent multimedia platforms.

7. Conclusions

This work proposed a fully pipelined, real-time hardware architecture for multi-resolution spline-based signal reconstruction. Implemented on a Xilinx Artix-7 FPGA, the system achieves high throughput (11.2–33.1 MS/s) and low latency (8–12 cycles) with minimal power consumption (<250 mW).

Experimental evaluation confirms that cubic B-spline interpolation preserves signal fidelity with average PSNR above 37.8 dB and SSIM above 0.94 for 4× image upsampling. Comparisons against CPU and GPU baselines highlight the superior energy efficiency and deterministic performance of the proposed design.

Due to its modular structure, low resource footprint, and excellent signal quality, the architecture is well-suited for real-time embedded multimedia applications, including image enhancement, sensor data upscaling, and low-power edge processing. Moreover, the parameterized and kernel-agnostic nature of the pipeline makes it readily extensible to alternative interpolation schemes—such as Lanczos or Catmull–Rom filters—as well as adaptable to diverse signal types, including biomedical waveforms or geospatial imagery.