1. Introduction

The rapid integration of UAVs into cellular networks has introduced significant challenges in maintaining seamless and reliable connectivity in dense urban environments [

1]. Unlike terrestrial users, UAVs operate at varying altitudes and travel long distances at high speeds. They frequently switch between base stations (BSs), which can degrade network performance [

2]. This switching can lead to increased latency, potential handover failures, and reduced Quality of Service (QoS) [

3]. UAVs’ high mobility and 3D trajectories expose them to complex radio conditions. They often maintain Line-of-Sight (LOS) links with multiple BSs but also experience intermittent Non-Line-of-Sight (NLOS) transitions due to urban obstructions [

4,

5]. Conventional handover mechanisms, such as received signal strength indicator (RSSI) based and hysteresis threshold-based techniques, are widely used in terrestrial networks. However, they struggle to handle the dynamic mobility of UAVs [

6]. These conditions lead to fluctuating signal quality and increased interference, especially from terrestrial users sharing the same spectrum [

7]. Additionally, existing cellular infrastructure is optimized for ground-level coverage, with base station antennas typically using downward-tilted beams [

8]. Consequently, UAVs often connect via antenna side lobes instead of the main beam. This leads to unstable connectivity, higher interference, and more frequent handovers [

9].

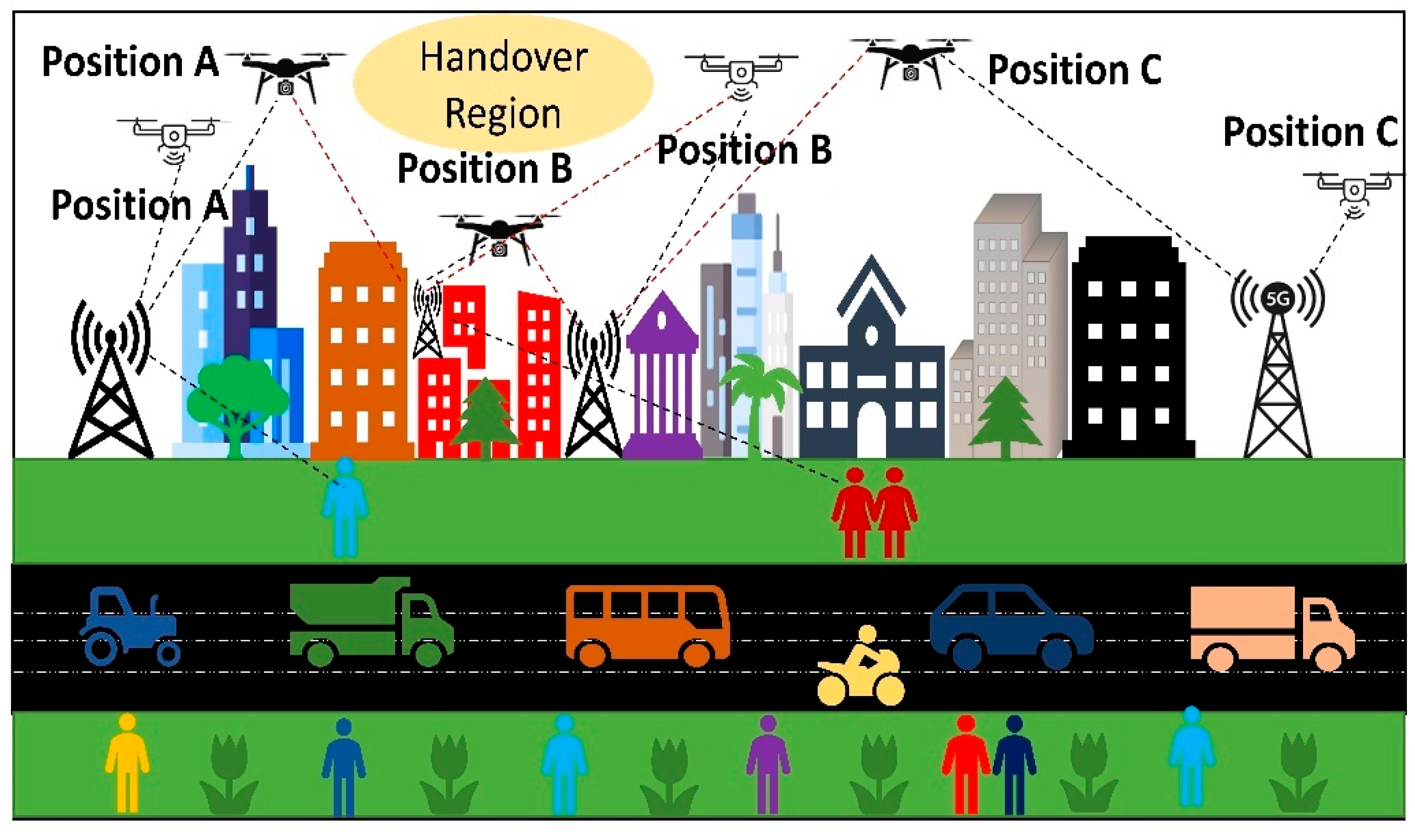

To illustrate these challenges,

Figure 1 depicts UAV behavior in a dense urban environment, showing their movement through Positions A, B, and C while maintaining connectivity with different BSs. The dashed black lines represent the desired communication links between UAVs and BSs, whereas the dashed red lines indicate interference from nearby cells. As the UAVs move across overlapping coverage areas, signal strength changes and handovers occur within the highlighted handover region. This figure highlights the connectivity challenges associated with interference, varying link quality, and frequent cell transitions, emphasizing the need for adaptive handover management.

This study proposes a novel framework that integrates XGBoost for predictive handover detection with reinforcement learning (RL)-based Q-learning for real-time handover decisions [

10,

11]. The framework is evaluated in a 10 km × 10 km simulated area containing a heterogeneous network of LTE and 5G NR BSs. Four UAVs operate within 5 km × 5 km quadrants, following sinusoidal trajectories with a total flight path of about 38.2 km. Network parameters are sampled every 100 ms over a 1376-s period. The dataset, generated using the 3GPP TR 36.777 UMa channel model, includes LOS/NLOS transitions and a frequency reuse-7 scheme, providing realistic conditions for developing and testing intelligent handover strategies [

12,

13]. In standard cellular networks, the 3GPP A3 event-based handover method triggers a handover when the signal from a neighboring cell becomes stronger than the serving cell by a predefined margin. While this method is simple and widely used, it often causes unnecessary handovers or link failures under high mobility and interference conditions, such as in UAV scenarios.

The proposed framework introduces a probabilistic gating mechanism that connects XGBoost predictions with Q-learning decisions. Specifically, the XGBoost model estimates the likelihood of a handover, and when this probability exceeds a calibrated threshold, the Q-learning agent initiates exploration of potential handover actions. This design reduces random exploration and focuses learning on connectivity-critical situations, improving both efficiency and stability. Unlike most existing episodic RL-based methods, which reset the environment after fixed intervals, the proposed approach uses a continuous learning process. This structure better reflects real UAV flights, where mobility and channel conditions evolve without interruption, allowing the agent to learn long-term signal and mobility patterns. Consequently, the framework achieves more adaptive and reliable handover behavior compared to both the standard 3GPP A3 event-based method and episodic RL approaches [

14]. Based on this framework, the main contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

A high-fidelity simulation framework for UAV mobility and connectivity in an urban environment, based on 3GPP UMa channel models with 100 ms resolution.

A handover management framework that combines XGBoost for predictive handover detection with Q-learning for adaptive decision-making.

The proposed PRQF framework is evaluated across four UAV operating quadrants and additionally tested in a 5G-dominant quadrant. It achieves an average handover reduction of 84% at 100 km/h and 83% at 120 km/h compared to the A3 event-based method.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews the existing literature on UAV handover and mobility management, highlighting challenges in maintaining seamless connectivity.

Section 3 discusses the system layout and problem formulation, providing the foundation for the proposed framework.

Section 4 outlines the methodology, detailing how XGBoost and Q-learning are integrated for handover optimization.

Section 5 presents simulation results and performance analysis. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper and discusses potential directions for future work.

2. State of the Art

Conventional approaches, designed for terrestrial users, rely on User Equipment (UE) history to predict target BSs [

15]. This significantly reduces handover failures and the ping-pong effect. These methods laid the foundation for more robust handover schemes. Multi-criteria fuzzy logic frameworks [

16] extend this concept by considering factors such as average RSRP, RSRP change rates, and BS traffic loads. These frameworks improve decision-making in multi-connectivity scenarios for cellular-connected UAVs. However, they often struggle to accommodate the dynamic, high-speed nature of aerial users.

In response to these limitations, advanced strategies that exploit UAV-specific mobility characteristics have emerged. Route-aware algorithms utilizing pre-configured flight path information [

17] achieve remarkable reductions in handovers and failures. They effectively eliminate the ping-pong effect and minimize signalling overhead. Handover skipping in High Altitude Platform Station (HAPS)-Ground networks [

18] further mitigates the impact of 3D mobility. This approach reduces handover rates, enhances coverage, and improves network throughput. These studies highlight the value of tailoring handover strategies to the specific requirements of aerial users.

Analytical approaches have also contributed to refining handover management. Stochastic geometry has been used to optimize distance and RSS-based associations in multi-tier UAV networks [

19]. These methods balance UAV density and altitude to maximize coverage for both aerial and terrestrial users. Graph theory and Lagrangian relaxation techniques have been proposed to minimize handovers during a UAV’s mission while maintaining communication quality [

20]. However, these approaches often rely on accurate trajectory data, which poses challenges in dynamic urban environments. The evolution of mobile networks, particularly with 5G and beyond, introduces additional complexity in ultra-dense, three-dimensional settings. This necessitates techniques that go beyond conventional methods to ensure seamless UAV connectivity.

Machine learning (ML) has revolutionized UAV handover management by enabling adaptive responses to dynamic network conditions. ML-based approaches incorporate UAV-specific factors such as speed, altitude, and interference [

21]. These approaches optimize handover and radio resource management, addressing issues like communication delays in urban environments. Fuzzy logic controllers tailored for high-mobility users, such as traveling trains and drones [

22], enhance QoS and Quality of Experience (QoE) by dynamically adjusting handover decisions. Despite these advancements, ML techniques face challenges in real-time handover prediction and optimization, particularly in dense urban environments where mobility patterns are highly variable.

Deep reinforcement learning (DRL) has shown significant promise in overcoming these limitations. A Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO)-based UAV Handover Decision scheme [

23] reduces handovers by up to 76% compared to conventional methods. It also maintains reliable connectivity above −75 dBm for over 80% of the time. Similarly, a proactive handover decision framework using DRL with PPO [

24] employs a state space incorporating UAV position, velocity, direction, and current base station ID, with actions selecting the optimal target BS. The reward function balances handover penalties against RSSI rewards via a tuneable weight, achieving 73–76% handover reductions in a 3D-emulated environment with random waypoint mobility and simplified path loss modelling. Another approach integrates service availability-aware Mobility Robustness Optimization (MRO) with Deep Q-Network (DQN) [

25]. This method improves service availability by over 40% and reduces handovers by more than 50%. Hybrid DRL frameworks, such as double deep Q-networks [

26], combine multiple ML techniques to optimize handover decisions in high-mobility and small-cell deployments. These frameworks address frequent handovers and interference in dense networks. Joint optimization of UAV trajectory and handover management represents a further advance. A Double Deep Q-Network (D3QN)-based algorithm [

27] reduces handovers by 70% and interference by 18%, with only a slight increase in transmission delay. A summary of related studies on UAV handover and connectivity management is provided in

Table 1, highlighting the methodologies, operational environments, and key contributions.

Several studies [

18,

21,

25,

27] often simplify UAV mobility by assuming straight-line trajectories and constant speeds, coupled with basic path loss models. While such simplifications reduce computational costs, they fail to capture the lateral motion typical of real UAV missions. In this work, UAVs follow sinusoidal flight paths at a fixed altitude, providing smooth lateral movement and continuous distance variation relative to BSs. This trajectory pattern reflects practical surveillance and mapping operations, producing natural signal fluctuations without the randomness or abrupt changes of waypoint-based mobility. Furthermore, the dataset generated under this configuration includes over 13,000 samples per UAV with 13 synchronized features, providing rich temporal and spatial diversity that supports accurate learning of connectivity behavior. The decision mechanisms used in earlier work also impose significant constraints. Fuzzy-logic-based schemes [

16,

22] rely on predefined membership functions and static categorizations, limiting adaptability to interference variations or sudden link degradation. Likewise, rule-based methods [

17,

20] depend on fixed thresholds and offline computations, making them less effective under dynamic channel conditions and high-speed UAV movement. These static mechanisms often respond too slowly to signal fluctuations, causing unnecessary handovers or degraded link continuity.

DRL approaches [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27] have introduced greater adaptability to UAV handover management; however, they still face notable challenges. Most are trained in episodic environments, where learning restarts after each fixed-duration episode. This structure prevents the agent from retaining long-term dependencies between mobility and signal quality, which are crucial for continuous UAV operation. In addition, on-policy algorithms such as PPO [

24] require new trajectory data for every update and large batch size for stable training, increasing computational and memory demands. These characteristics make real-time implementation difficult on UAV platforms, particularly since handover decisions are inherently discrete. To overcome these issues, the proposed PRQF introduces a unified design that integrates XGBoost-based probabilistic prediction with continuous Q-learning policy adaptation. This combination eliminates reliance on static thresholds and episodic resets, allowing the agent to learn and adapt during uninterrupted flight.

3. System Layout and Problem Formulation

This study focuses on optimizing handover management for cellular-connected UAVs operating as user equipment (UE) within a 10 km by 10 km area. The scenario considers a heterogeneous network with LTE and 5G NR BSs, while UAVs follow predefined sinusoidal trajectories to simulate aerial mobility [

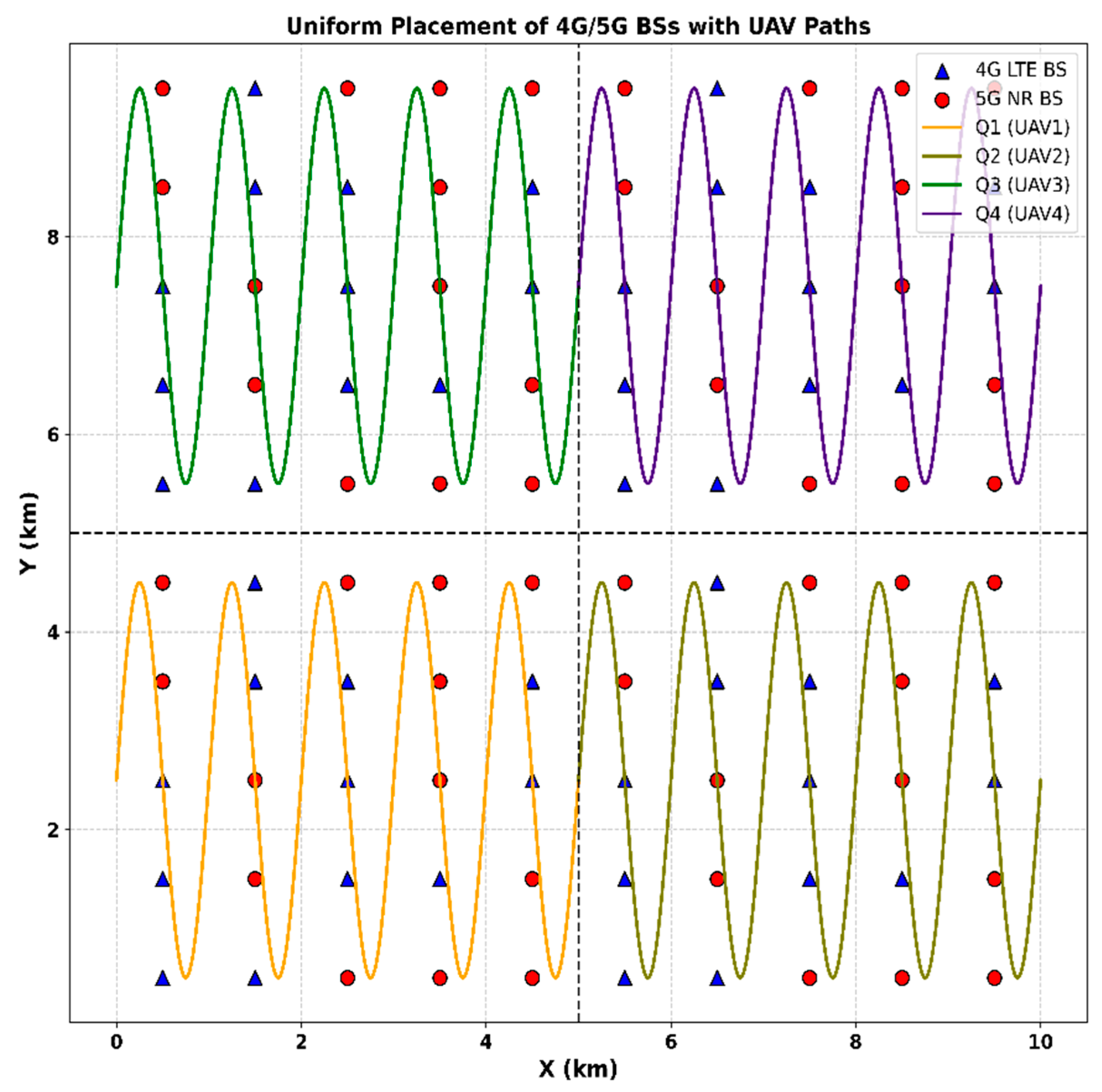

28]. The UAVs are distributed across four quadrants to ensure spatial diversity, balanced network load, and exposure to distinct coverage conditions. The objective is to evaluate handover performance and throughput under dynamic mobility and real-time network conditions, while also generating data to support future RL-based handover optimization. The simulation captures key metrics such as handover frequency, signal quality, and overall network performance, which are analyzed through spatial trajectories, temporal handover events, and statistical distributions. The overall scenario is illustrated in

Figure 2, showing LTE and 5G NR base station deployment and the sinusoidal flight paths of four UAVs in assigned quadrants.

The network consists of 100 sectorized BSs, including 50 LTE BSs and 50 5G NR BSs. The LTE BSs operate at 0.9 GHz with a transmit power of 36 dBm (4 W) per sector and an antenna height of 25 m, while the 5G NR BSs operate at 2.1 GHz with a transmit power of 39 dBm (7.94 W) per sector and an antenna height of 30 m. BSs are deployed on a grid with 1 km spacing, uniformly assigned to LTE or 5G via permutation of grid centers, ensuring a dense and balanced topology, as shown in

Figure 2. This placement, combined with sectorization, introduces spatial variability in coverage, interference, and handover patterns. The UAV mobility parameters corresponding to this setup are summarized in

Table 2.

Each BS employs three sectorial antennas, each covering a 120-degree azimuth plane (0–120°, 120–240°, 240–360°), providing full 360-degree coverage. The LTE bandwidth is 5 MHz, and the 5G NR bandwidth is 10 MHz, supporting high-capacity aerial communication. LTE BS sectors are configured with a horizontal beam width of 30°, a vertical beam width of 12°, an electrical down tilt of −6°, and a maximum directional gain of

[

29]. In contrast, 5G NR BSs utilize a high resolution 24-beam pattern per sector. Each beam covers a horizontal beam width of 5°, and the 24 beams are uniformly spaced across the sector [

30,

31], ranging from −32° to +32° relative to the sector center. This arrangement results in partial overlap between beams, ensuring full 120° coverage of the sector. The antenna gains for both LTE and 5G systems are modeled using the following directional gain formula:

where,

: Maximum antenna gain (LTE: 18 dBi, 5G: 24 dBi).

: Azimuth and elevation angles.

Beam center angles.

= 20 dB: maximum attenuation.

UAVs operate at a fixed altitude of 100 m within a 10 km by 10 km urban environment, each UAV is confined to one of four quadrants: (0–5 km, 0–5 km), (5–10 km, 0–5 km), (0–5 km, 5–10 km), and (5–10 km, 5–10 km). Within its quadrant, each UAV follows a sinusoidal trajectory defined by the equation:

where,

varies from 0 to 38.202 km and

and

represent the vertical bounds of the respective quadrant like 0 and 5 km for the first quadrant. The sine wave is scaled to produce a peak-to-peak vertical displacement of 0.8 H, which corresponds to an actual amplitude of 0.4 H, ensuring that the UAV remains within the quadrant bounds.

The period of the sinusoidal trajectory is 1 km, and the amplitude is scaled to 80% of the quadrant height to ensure the path remains within bounds. The total path length of approximately 38.202 km corresponds to the arc length of five sinusoidal cycles over a 5 km horizontal span, scaled to cover the full horizontal range of the quadrant. Each UAV moves at a constant speed, with two speed profiles considered: 100 km/h (27.78 m/s) and 120 km/h (33.33 m/s). This variation in speed is introduced to reflect possible differences in UAV mission requirements. Position updates occur every 100 milliseconds, resulting in discrete steps throughout the flight. Inter-cell interference is controlled using a frequency reuse-7 scheme, with BS frequencies assigned via K-means clustering to reduce co-channel interference [

32,

33,

34]. Only BSs using the same frequency as the serving BS contribute significantly to interference, while others have a negligible effect due to power control and distance. The network and antenna configurations used in the simulation are summarized in

Table 3.

The interference power at UAV

is calculated as:

Here,

represents the set of co channel BSs and

is the received power from

at the UAV. Inter UAV interference is not modeled, under the assumption that uplink interference is negligible due to the limited number of UAVs and their spatial separation across quadrants. Signal propagation is modeled according to the 3GPP TR 36.777 UMa specifications for aerial UEs [

35], incorporating both LOS and NLOS conditions. The three-dimensional distance between a UAV and a BS is given by:

is the horizontal distance,

= 100 m, and

is 25 m for LTE and 30 m for 5G [

36,

37].

Path loss is calculated using the following formulas:

For LOS conditions:

For NLOS conditions:

is the carrier frequency in GHz (0.9 GHz for LTE, 2.1 GHz for 5G).

The probability of Los is modeled as:

where,

is the elevation angle in degrees. Shadow fading is represented as a log normal random variable with a standard deviation of

for LOS conditions and

for NLOS conditions [

38]. The RSRP at UAV

from base station

is computed as [

39]:

is the Bs transmit power,

is the directional antenna gain,

is the path loss and

is the shadow fading component modeled as a gaussian random variable. The SINR [

40] for UAV

is given by:

is the thermal noise power, with a bandwidth

for LTE and 10 MHz for 5G, and a noise figure of 3 dB. The interference power

is the sum of received powers from co channel BSs. Handover decisions in cellular networks are based on 3GPP event A3 condition [

41], which triggers a handover from a serving cell to a target cell when:

where the offset is 2 dB and the hysteresis margin is 3 dB. A Time-To-Trigger (TTT) of 0.2 s is also applied to prevent unnecessary handovers caused by short-term signal fluctuations.

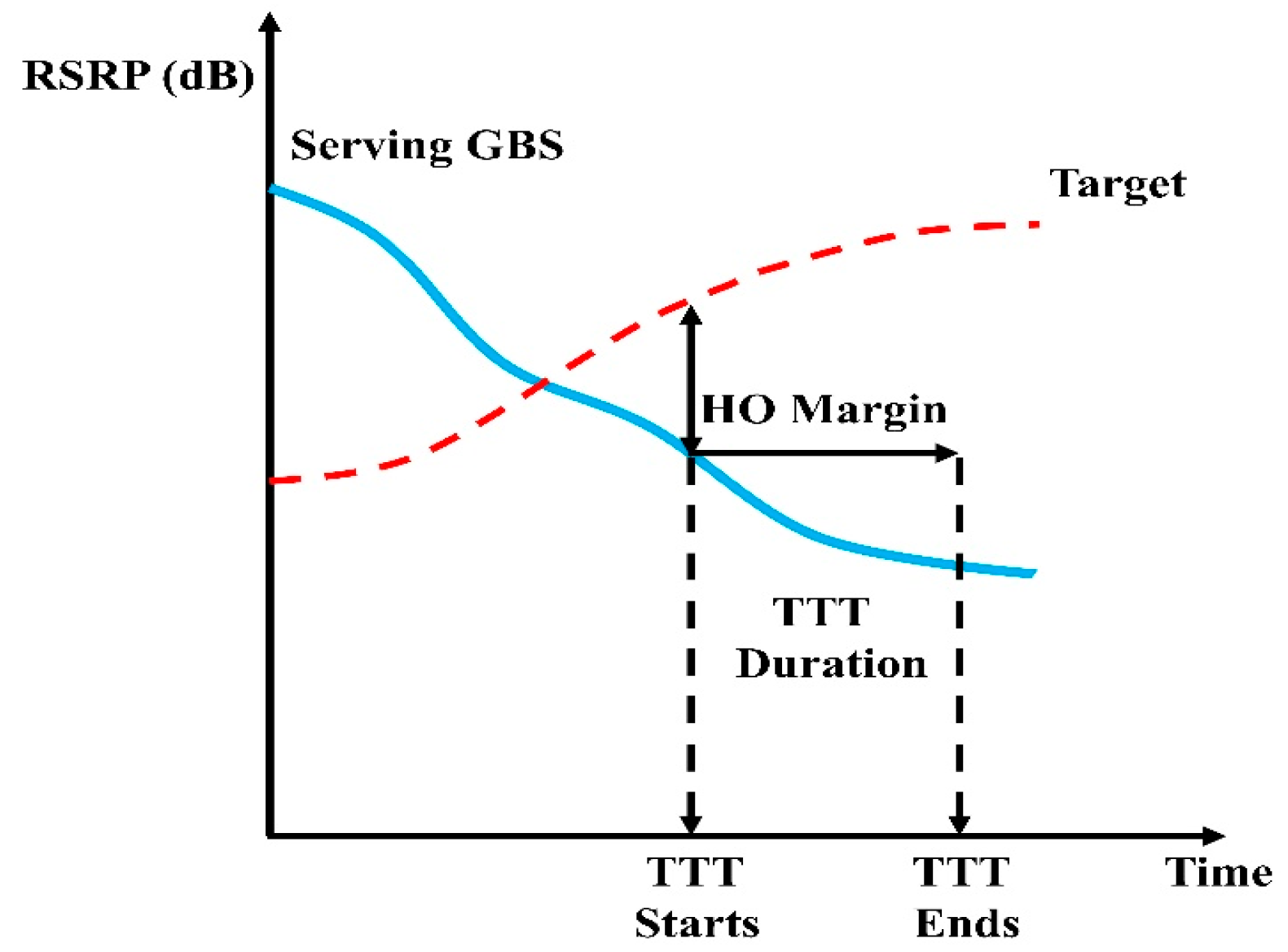

The handover mechanism is presented in the

Figure 3, where the blue curve represents the RSRP from the serving BSs, and the red dashed curve corresponds to the RSRP from the target BSs. A handover is initiated when the RSRP of the target BSs exceeds that of the serving BSs by a threshold equal to the sum of the offset and hysteresis margin. This difference is marked as the HO Margin in the figure. The vertical dashed lines indicate the beginning and end of the Time-To-Trigger (TTT) interval. Once the A3 condition (Equation (10)) is met, a timer is started (“TTT Starts”). If the condition remains valid throughout the entire TTT duration, the handover is executed at the end of the interval (“TTT Ends”). However, if the condition is no longer satisfied before the timer completes, the handover is cancelled. This timing mechanism helps to ensure robust and stable handover decisions by filtering out temporary fluctuations in signal strength. Throughput is determined using Adaptive Modulation and Coding (AMC), modeled as:

where

is the channel bandwidth and

represents the spectral efficiency as function of SINR. The spectral efficiency varies from 0.03 bits/s/Hz for SINR below −10 dB to a maximum of 6.57 bits/s/Hz for SINR above 40 dB, based on a detailed modulation and coding scheme (MCS) table with defined SINR thresholds [

42].

4. System Model and Methodology

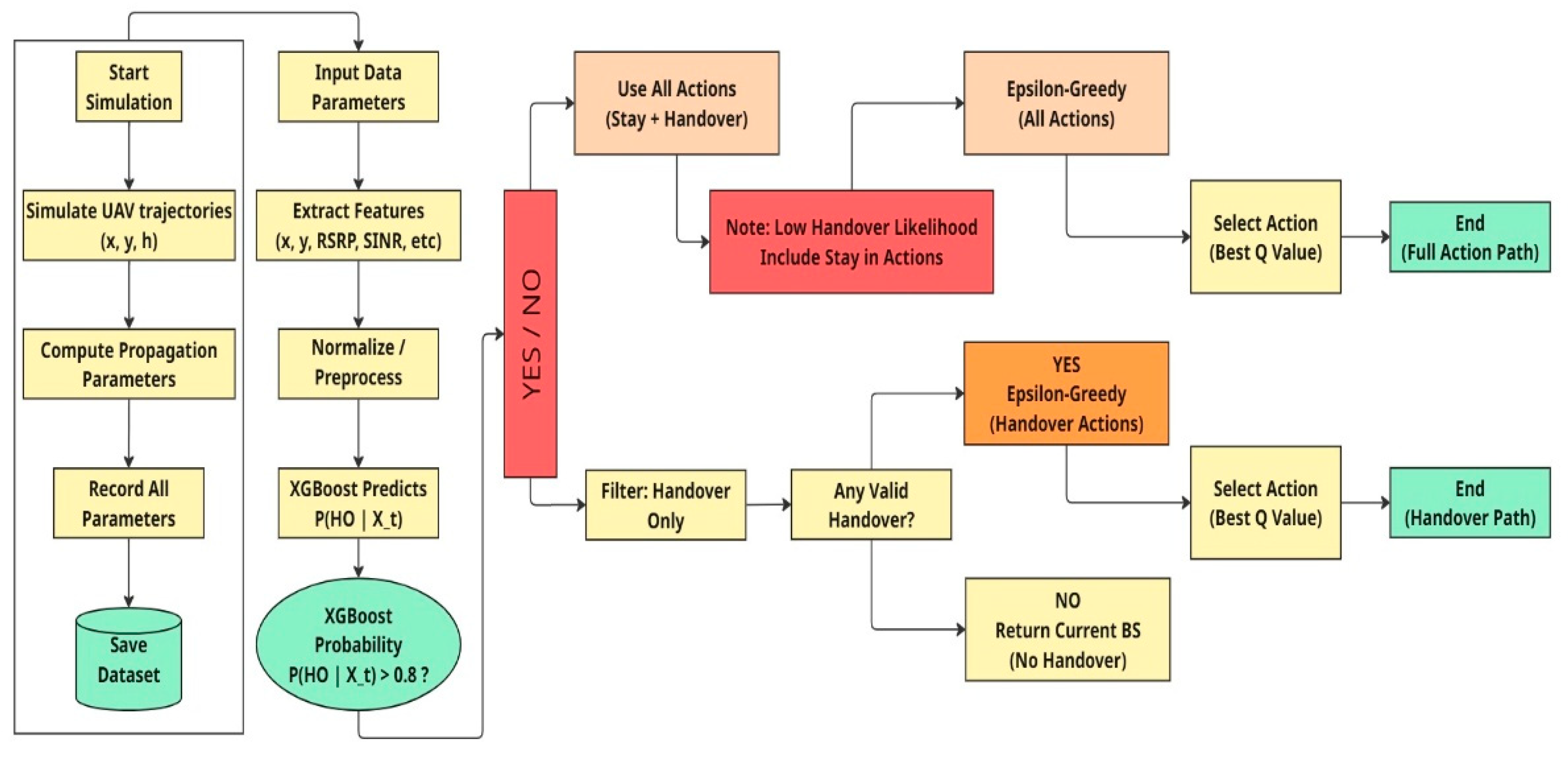

This section presents the materials and methods developed to address the challenge of handover management for cellular-connected UAVs in urban environments. The proposed methodology is based on a Predictive–Reactive Q-Learning Framework (PRQF) that combines supervised learning with RL to improve decision-making under changing network conditions. The approach comprises three main components. First, synthetic data is generated to simulate operational UAV mobility and network interactions. Second, an XGBoost classifier is used to predict handover probability and anticipate potential connectivity disruptions. Finally, a Q-learning–based reinforcement learning module adaptively optimizes handover policies in real time [

43,

44]. These components leverage signal propagation models, predictive analytics, and adaptive learning to maintain robust connectivity, maximize throughput, and reduce unnecessary handovers.

In the PRQF workflow, each UAV continuously extracts signal-quality features from surrounding LTE and 5G NR base stations, which reflect short-term fluctuations caused by directional beam scanning in 5G NR deployments [

45]. These beam-induced variations, together with the UAV’s position coordinates, are incorporated into the state representation and provided as input to an XGBoost classifier to estimate the probability of a cell-level handover. This predicted probability is then used to regulate the action space of the reinforcement learning agent by filtering candidate handover actions. Higher probability values activate handover candidates, whereas lower values favor maintaining the current connection. Based on this reduced action set, an ε-greedy policy selects the action with the highest expected long-term reward according to the learned Q-values [

46].

Figure 4 outlines this workflow, showing the stepwise combination of data simulation, handover prediction, and RL to guide UAV decision-making efficiently. The selected action results in either a complete action path or a handover path, ensuring adaptive and effective operation.

4.1. Dataset Generation

The initial and foundational phase of the proposed methodology involves the construction of a high-dimensional, multi-layered dataset. This dataset encapsulates a comprehensive range of spatiotemporal, physical-layer, network-layer, and control-plane features that characterize UAV mobility and wireless link behavior. The same high-fidelity simulation environment used for dataset generation also serves as the operational environment for the RL agent, ensuring consistent state transitions and realistic feedback during training. Each UAV trajectory produces approximately 13,760 time-stamped samples, corresponding to a total simulation duration of 1376 s with a 100 ms sampling interval (1376 s/0.1 s = 13,760 steps). The UAV follows a predefined sinusoidal trajectory at constant speeds of 100 km/h and 120 km/h in separate simulation runs. At 120 km/h, the UAV covers approximately 45.9 km within the 1376-s interval; upon completing the sinusoidal path, it reverses direction and retraces the same route to maintain trajectory continuity. Following dataset construction, physical-layer metrics are extracted in real time, including RSRP, SINR, and instantaneous measurements of noise and co-channel interference variance across frequency bands. At the network layer, the dataset includes the serving Radio Access Technology (RAT) identifier, which distinguishes between LTE and 5G NR systems. It also contains base station indexing, cell locations, and the neighborhood topology of available cells. QoS indicators are embedded, including throughput derived from AMC mechanisms and latency values associated with handover procedures. This dataset thus serves a dual purpose: training the XGBoost classifier for probabilistic handover prediction and defining the high-dimensional state and action spaces for RL-based decision optimization.

4.2. XGBoost Classifier for Handover Prediction

The XGBoost classifier [

47] operates as a probabilistic gating mechanism that constrains the RL agent’s exploration space. It ingests a high-dimensional input vector:

where spatial coordinates, physical-layer metrics, and QoS indicators are temporally synchronized to reflect the UAV’s state at time

. The classifier is trained using datasets generated from four UAV flights, each containing approximately 13760 time-stamped records corresponding to a 1376-s simulation sampled at 100 ms intervals. Before training, all features are converted to numerical form, missing values are removed, and z-score normalization is applied to achieve zero-mean, unit-variance scaling. The cleaned dataset is split into 80% training and 20% testing subsets using a fixed random seed to preserve reproducibility. The XGBoost classifier is implemented as an ensemble of gradient-boosted decision trees optimized by minimizing the regularized objective function:

where

denotes the binary logistic loss between the ground truth handover labels

and the model’s predicted scores

, and

represents the combined

regularization that controls overfitting. Each predicted score

represents the aggregated raw output (logit) from all boosted trees at iteration t. Applying a logistic sigmoid transformation converts this logit into a probabilistic estimate

, indicating the likelihood of a handover event given the UAV’s current state. The threshold value of 0.8 was selected empirically through receiver-operating-characteristic (ROC) analysis on the validation set. Thresholds between 0.6 and 0.9 were tested, and 0.8 achieved the best balance between precision and recall. Lower thresholds increased premature handovers, while higher thresholds delayed handover initiation and led to occasional link failures.

Although XGBoost introduces additional hyperparameters and computational overhead, its model size remains lightweight due to shallow tree depth and limited boosting rounds. The classifier operates as an independent gating module within the PRQF, allowing straightforward retraining if UAV trajectories or urban layouts change. Retraining can be performed on updated trajectory datasets without altering the PRQF architecture, thereby preserving modularity and adaptability. The model’s performance was evaluated using precision [

48], accuracy [

49], recall [

50], and F1-score [

51]. Accuracy measures the overall proportion of correctly classified predictions and can be calculated as:

Precision quantifies how many of the predicted handovers were correct, given by:

Recall indicates the model’s ability to identify all actual handovers and is computed as:

F1-score provides a harmonic balance between precision and recall, and is expressed as:

where TP, TN, FP, and FN denote true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives, respectively. A true positive corresponds to a correctly predicted handover, while a false negative indicates a missed handover.

4.3. Policy Optimization Through Predictive-Reactive Q-Learning Framework (PRQF)

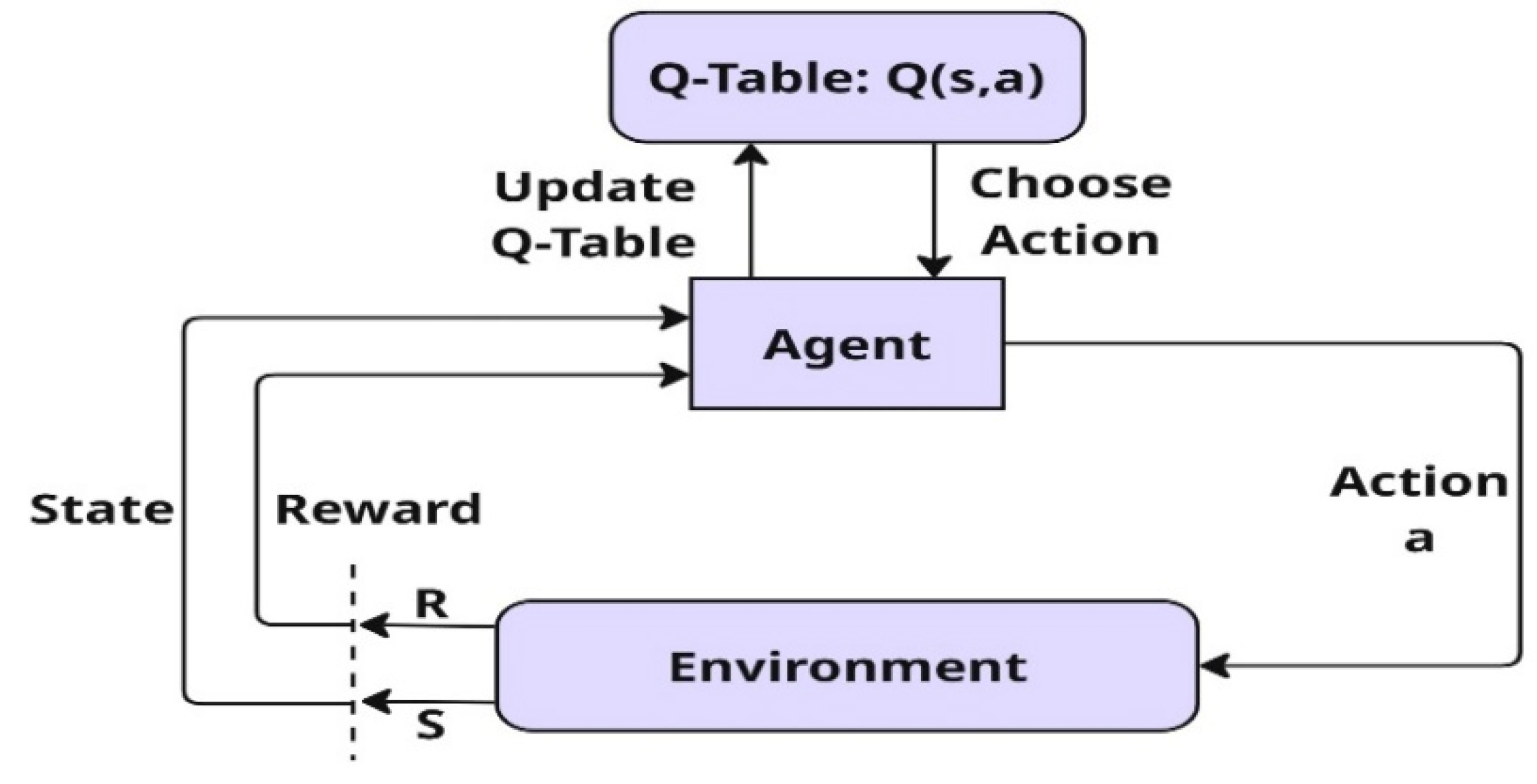

The proposed framework is built around a tabular Q-learning algorithm [

52], selected due to its computational efficiency and effectiveness in estimating optimal state–action values. This approach is well-suited for modeling the UAV handover decision process, which is formulated as a discrete Markov Decision Process (MDP) [

53], where the environment is discretized into a structured state space

. Each state

is defined as a tuple

, encoding the UAV’s spatial location, signal quality, serving RAT, and base station identifier at time

t. Spatial bins are formed by discretizing continuous UAV coordinates into 0.1 km grid cells, while SINR and RSRP values are quantized into predefined ranges to form categorical state levels. Action space A consists of discrete mobility decisions, including remaining connected to the current cell (stay) or initiating a handover to one of several candidate BSs across LTE and 5G NR. To reduce unnecessary transitions, candidate cells are dynamically filtered using an RSRP-based threshold such that only those satisfying

are retained. The agent’s objective is to learn a policy

that maximizes long-term return. This is achieved through a tailored reward function

defined as a piecewise mapping from post-action SINR values to scalar rewards, penalizing low-SINR outcomes and incentivizing high-quality links. Specifically, handovers that degrade SINR are assigned negative rewards, whereas stable connections with superior SINR and no handover event are rewarded positively, thus integrating both link quality and mobility cost considerations into the learning process. Learning is governed by the standard Bellman update rule [

54]:

where

is the learning rate and

is the discount factor for future rewards. An

-greedy exploration strategy is employed, with

gradually decaying.

The XGBoost-based handover forecasting module acts as an action filter: when the predicted handover probability

falls below a calibrated threshold, the agent limits its policy execution to non-handover actions. This integration embeds prior knowledge into the Q-learning loop and suppresses exploration in low-risk connectivity states. The key parameter values used in the PRQF model, including those for XGBoost and Q-learning, are summarized in

Table 4.

Figure 5 illustrates the Q-learning interaction loop, showing how the UAV agent observes its current state, selects an action, and receives a reward from the environment. The Q-table is then updated based on the observed SINR and chosen action, allowing the policy to improve over time. The framework operates within a high-fidelity UAV network simulator, which emulates realistic wireless propagation, mobility dynamics, and protocol interactions.

To clarify the learning workflow, Algorithm 1 presents the pseudocode of the proposed PRQF.

Initialize Q-table, learning rate α, discount factor γ, and ε for ε-greedy policy. Load trained XGBoost model for handover probability prediction. While UAV simulation is not complete, do: Observe current state s_t = (x_bin, y_bin, Cell_ID, RSRP_class, SINR_class, RAT). Predict handover probability p_h = P(HO | X_t) using XGBoost. If p_h ≥ θ (handover likely), then: Define action set A_t = {stay, valid handover candidates}. Else: Define action set A_t = {use all actions}. End if. Select action a_t ∈ A_t using ε-greedy strategy. Execute action a_t and observe next state s_{t+1} and SINR. Compute reward r_t based on SINR and handover cost: If SINR < 0 dB, then r_t = −1. Else if 0 ≤ SINR < 10 dB, then r_t = −0.5. Else if 10 ≤ SINR < 20 dB, then r_t = +0.5. Else r_t = +1. If handover occurred, then r_t = r_t − 0.2. Update Q(s_t, a_t) ← Q(s_t, a_t) + α [r_t + γ max_a′ Q(s_{t+1}, a′) − Q(s_t, a_t)]. Set s_t ← s_{t+1}. End while. Output optimized Q-table and evaluate performance (throughput, SINR, handover rate).

|

5. Simulation Results

The simulation models a 10 km × 10 km area with a heterogeneous LTE/5G network of 100 sectorized BSs and four UAVs following sinusoidal trajectories in separate quadrants. Each UAV operates at 100 m altitude, moving at a constant speed of 100 km/h and 120 km/h, with network and mobility parameters captured every 100 ms. The model integrates 3GPP-compliant propagation characteristics, including LOS/NLOS path loss, directional antenna gains, and interference modeling using frequency reuse-7 with power control. Handover events are governed by the A3 event condition with configurable margins and a Time-To-Trigger mechanism. Throughput is determined using AMC based on SINR. This setup enables detailed assessment of handover dynamics and throughput variation under unique aerial mobility in heterogeneous LTE/5G deployments. The following result analysis is structured into three stages: initial data characterization, prediction performance analysis, and policy performance evaluation.

5.1. Initial Data Characterization

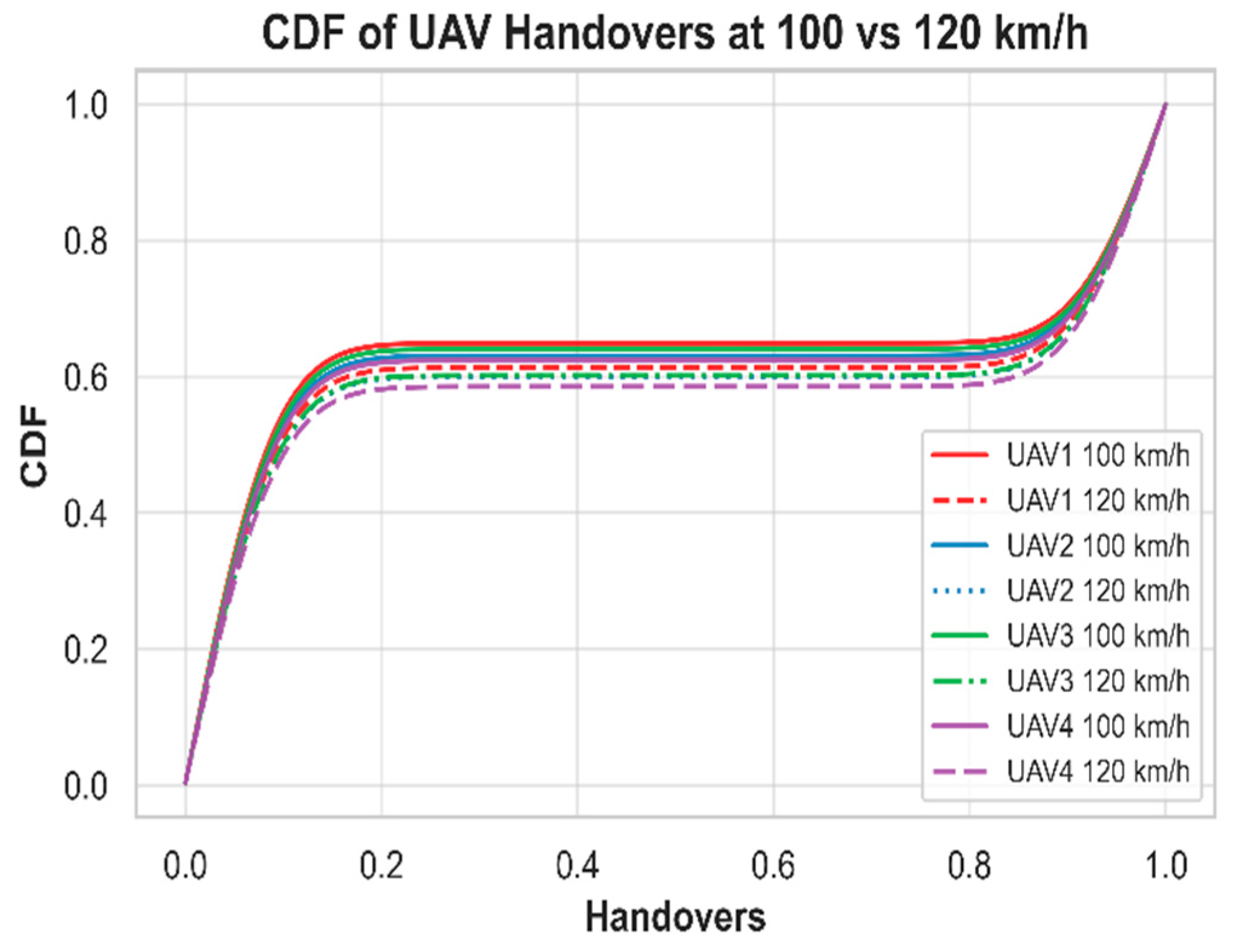

The baseline results derived from the conventional A3 handover event provide insights into the network dynamics experienced by the 4 UAVs. Two key performance indicators, handover frequency and throughput, are used to characterize the initial connectivity behaviour. The horizontal axis shows normalized handover counts, scaled from 0 to 1. This normalization enables fair comparison of UAVs with different absolute handover totals. In terms of handover patterns at 100 km/h,

Figure 6 shows that UAV 4 experiences the highest number of handovers. UAV 2 follows, exhibiting the second highest level of cell transitions. UAV 3 records a slightly lower handover intensity, while UAV 1 maintains the lowest number of transitions among the four UAVs. Although the mobility pattern is identical for all UAVs, this ordering indicates that each UAV can still encounter different network conditions along its path, which results in varying handover counts.

With the UAV speed increased to 120 km/h,

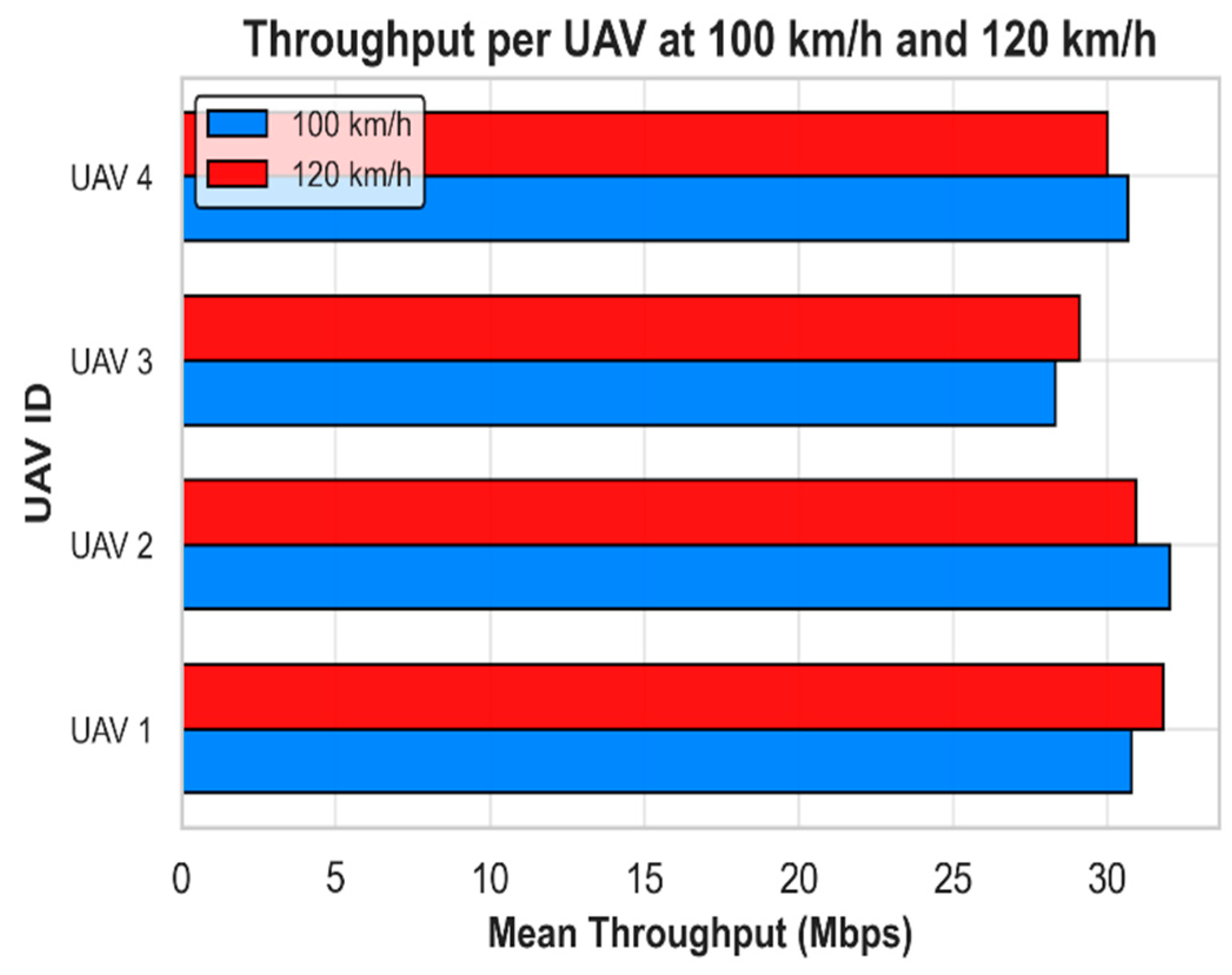

Figure 6 shows that the same ordering of handover activity is preserved, with UAV 4 exhibiting the highest number of handovers, followed by UAV 2, UAV 3, and UAV 1. Although the overall CDF structure remains consistent, all UAVs experience a moderate increase in handovers due to the higher mobility. The median number of handovers increases by approximately 8 to 12 percent when the speed rises from 100 km/h to 120 km/h, depending on the UAV. This reflects the expected rise in cell transitions as mobility increases, while still maintaining similar relative behaviour across the four UAVs. When examining throughput behavior, a consistent pattern is observed, as shown in

Figure 7. The horizontal axis represents the throughput in Mbps, ranging from low to high data rates measured for the UAVs. The colored axis lists the UAV IDs for comparison across the two speeds. For a speed of 100 km/h, UAV 2 achieves the highest mean downlink throughput with 32 Mbps, followed closely by UAV 1 at 30.8 Mbps, UAV 4 at 30.7 Mbps, and UAV 3 recording the lowest value of 28.3 Mbps. A similar ranking is maintained at 120 km/h, with UAV 2 again leading at 30.9 Mbps, followed by UAV 1 at 31.8 Mbps, UAV 4 at 30.0 Mbps, and UAV 3 at 29.1 Mbps. Notably, the throughput differences between UAVs are relatively small, and increasing speed from 100 km/h to 120 km/h produces only minor variations, with UAV 1 and UAV 3 showing slight improvements and UAV 2 and UAV 4 experiencing modest reductions. These results suggest that, under the evaluated conditions, the network provides robust and balanced downlink throughput across different UAVs and moderate speed variations, with platform-specific effects having limited impact on average data rates.

5.2. UAV Handover Prediction Analysis

The effectiveness of the XGBoost-based handover prediction framework was assessed using datasets collected from four UAVs. Each UAV operated within an assigned quadrant and provided approximately 13,760 synchronized time-stamped records. Each record included thirteen features such as the UAV’s horizontal position coordinates, SINR, and several network and physical-layer metrics. The preprocessing ensured all features were numeric, removed missing values, and applied z-score normalization. The model was trained to produce a probabilistic estimate of handover likelihood at each time step.

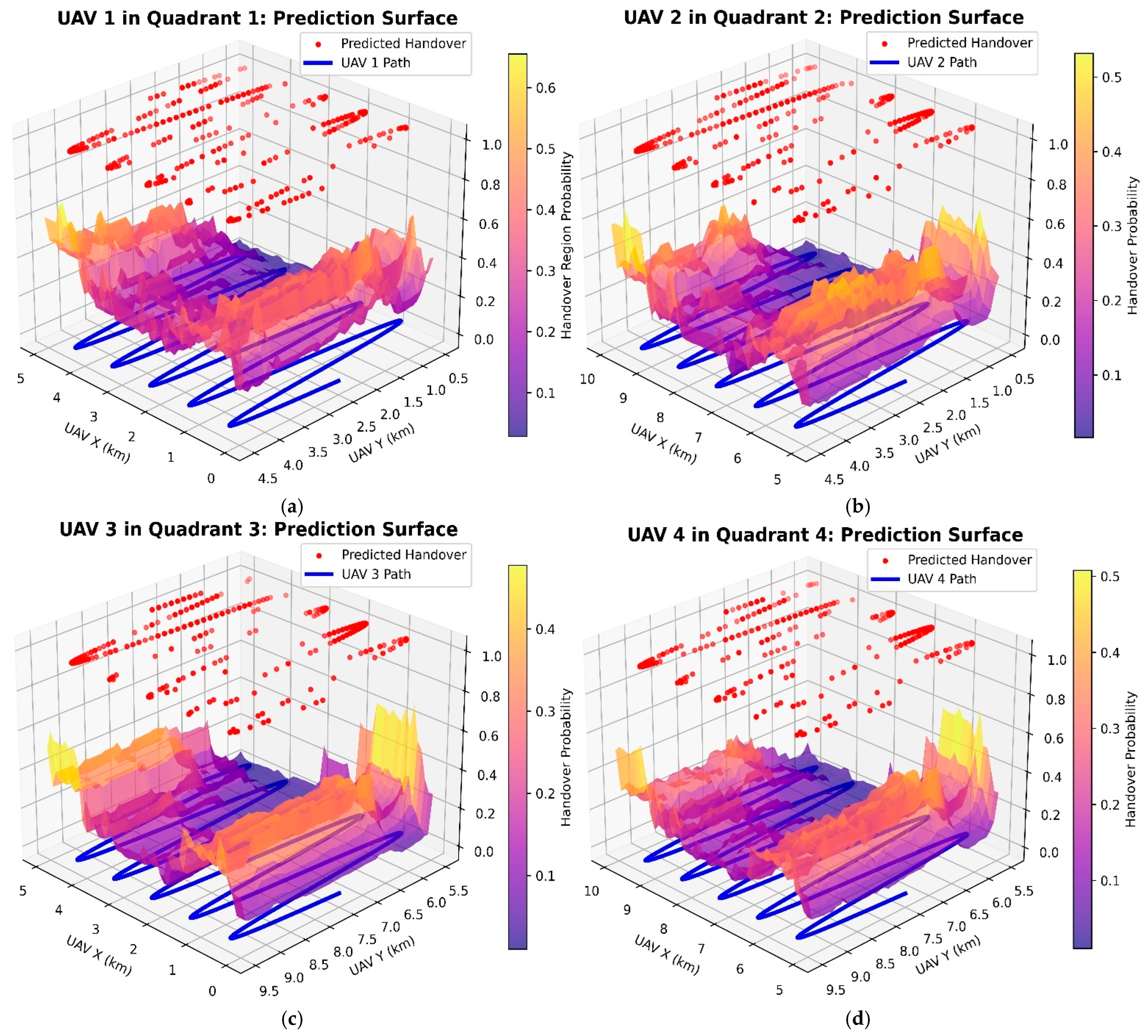

Figure 8a–d show three-dimensional prediction surfaces for each UAV quadrant. In each plot, the

x-axis and

y-axis give the UAV’s horizontal position in kilometers, matching its simulated flight trajectory. The

z-axis shows the predicted probability of a handover, from 0 (low likelihood) to 1 (high likelihood), with the color gradient further emphasizing this probability. The blue line in each plot traces the actual path taken by the UAV throughout its flight mission. Although the true altitude of the UAV in simulation is 100 m, for visualization purposes, the path is plotted at (z = 0) to ensure clarity and facilitate direct comparison with predicted handover events and the probability surface. Red dots appear along the trajectory, plotted at z = 1. These red dots mark specific locations where the XGBoost predictor assigns a handover probability greater than 0.8. This indicates states that are likely to result in an imminent handover. In the integrated Q-learning framework, these high-probability predictions act as an adaptive action filter. When the predicted probability is above a threshold, the RL agent can consider handover actions. If not, the agent only maintains the current connection. The spatial clustering and frequency of these predicted handovers show where the agent is allowed to consider handovers. This highlights the model’s sensitivity to channel conditions and its effectiveness in guiding policy learning to important regions.

Analysis of the results shows that for Quadrant 1 (

Figure 8a), the model identifies a distinct high-risk zone between approximately 1.5–4.5 km in the x-direction and 0.5–3.5 km in the y-direction, where the surface rises sharply to probabilities exceeding 0.5–0.6. This elevated region accurately captures the dense cluster of observed handover events along that segment of the path. Quadrant 2 (

Figure 8b) exhibits the smoothest and lowest prediction surface overall, with handover probabilities remaining mostly below 0.3–0.4 and only minor localized elevations; correspondingly, very few red dots appear along the trajectory, confirming excellent connectivity stability in this area. In Quadrant 3 (

Figure 8c), several sharp, narrow peaks reach probabilities of 0.4–0.5, and the measured handovers are tightly concentrated directly beneath these peaks, demonstrating precise localization of challenging spots by the model. Finally, Quadrant 4 (

Figure 8d) displays the most complex and problematic pattern: broad, interconnected bands of moderate-to-high probability (0.4–0.6) extend across large portions of the space, and handover events are densely scattered along almost the entire flight path, indicating persistent connectivity challenges throughout this quadrant.

Performance metrics for the XGBoost model, evaluated across all UAV trajectories, include an accuracy of 0.823, precision of 0.824, recall of 0.781, F1 score of 0.801, and ROC AUC of 0.86. Here, accuracy represents the overall proportion of correct predictions, precision measures how many predicted handovers were correct, and recall indicates how many actual handovers were successfully detected. The F1 score balances precision and recall, while the ROC AUC quantifies the model’s ability to distinguish between handover and no-handover states. This strong discriminative performance likely arises from the model’s ability to capture nonlinear interactions among key features such as UAV position, velocity, and signal strength, which provide clear separation between classes. Collectively, these results, shown in

Table 5, confirm that the model generalizes well across UAV trajectories. The Q-learning agent in the predictive-reactive framework continuously adapts its policy in response to residual prediction errors, ensuring stable connectivity across all UAVs.

To understand the system’s behaviour, a sensitivity analysis of the ML-related parameters was conducted. For the XGBoost gating threshold θ, setting values too high (θ = 0.9–0.95) made the agent overly conservative, filtering out handover actions and causing UAVs to remain connected for extended periods even under suboptimal conditions. Conversely, lower thresholds (θ = 0.5–0.6) increased the frequency of handovers, but led to excessive transitions that reduced the intended stability of the system. The baseline value of θ = 0.8 provided a balanced trade-off, allowing sufficient exploration while avoiding unnecessary handovers. Similarly, the XGBoost learning rate (η) strongly influenced probability calibration: higher values (η = 0.3) caused the classifier to become overconfident, distorting gating behaviour, while very low values (η = 0.01) slowed convergence. We found η = 0.1 to be an adequate value that generates stable performance. The number of boosting rounds (M) also affected performance: small values (M = 100) underfit the data, increasing mispredictions, whereas very large values (M = 1000) risked overfitting; M = 500 provided the best balance. For the Q-learning update rate (α), higher settings (α = 0.1) produced unstable Q-value oscillations, while very low values (α = 0.005) slowed adaptation; the moderate value α = 0.01 ensured reliable convergence. Overall, these results demonstrate that the baseline parameters (θ = 0.8, η = 0.1, M = 500, α = 0.01) achieve behaviour aligned with the framework’s design objectives.

The size of the state–action space and the corresponding memory requirements were analyzed. Theoretically, the combined factors of UAV position (10 × 10 km grid with 0.1 km resolution), connection technology (LTE and NR), and discretized SINR levels yield approximately 14 million possible states. However, during simulation, each UAV produced 13,760 time-stamped samples, with many consecutive positions sharing identical serving conditions. After pruning low-relevance candidate cells by retaining only the serving and top neighboring LTE or NR cells, the effective explored state–action space was significantly smaller. UAV 1 recorded 5128 state–action pairs, UAV 2 had 3822, UAV 3 had 4877, and UAV 4 had 5325, with an average of 6 to 8 actions per state. The resulting Q-table memory footprint was roughly 3.7 MB for all UAVs combined, which is compact compared to the theoretical multi-gigabyte requirement of an unpruned space. The pruning and compact representation keep the framework computationally efficient for the current multi-UAV scenario. For larger areas, additional UAVs, or finer spatial granularity, the framework could employ compact function representations of the Q-values, such as parametric or tabular aggregation methods, to maintain efficiency while handling a larger state–action space, ensuring the approach remains scalable and effective in more complex deployment scenarios.

5.3. Policy Performance Analysis Using Predictive-Reactive Q-Learning Framework

The methodology of this work centers on a RL-based framework designed to address the challenges of handover management in dense networks. In environments characterized by frequent mobility, fluctuating signal conditions, and dense cellular deployments, conventional handover algorithms often struggle to maintain seamless connectivity and optimal network performance. The proposed approach addresses these limitations by formulating the handover decision process as a sequential learning problem, enabling the agent to adapt its actions in response to complex network dynamics and operational constraints.

At the core of the framework is a tabular Q-learning algorithm that models UAV–cellular interactions as an MDP. The agent observes a structured state space including spatial location, signal strength, and serving cell identifiers, and selects from discrete mobility actions guided by a reward function that balances link quality and handover cost. To enhance learning efficiency, an XGBoost-based prediction module operates as an action filter, limiting exploration to states with high handover likelihood. The effectiveness of the proposed framework is evaluated against three reference setups: (1) the conventional A3 event-based handover rule with fixed hysteresis, (2) a Deep Q-network (DQN) baseline adapted from recent literature [

25], and (3) a Q-learning variant to isolate the contribution of the predictive gating mechanism. The DQN baseline was chosen as a representative deep reinforcement learning method to illustrate the differences in exploration strategies between classical tabular Q-learning and neural network–based RL approaches. It employs an ε-greedy exploration strategy with discount factor γ ∈ [0,1) and ε decaying from 1 to 0.01 and is trained within the same continuous UAV simulation environment for fair comparison. Unlike episodic training with resets, both PRQF and DQN learn online from uninterrupted UAV–network interactions, ensuring a consistent and unbiased evaluation of long-term mobility performance. All baseline methods are provided with the same observation vector, and the candidate cell selection using a fixed RSRP difference threshold is applied uniformly across all evaluated algorithms, maintaining a consistent action space.

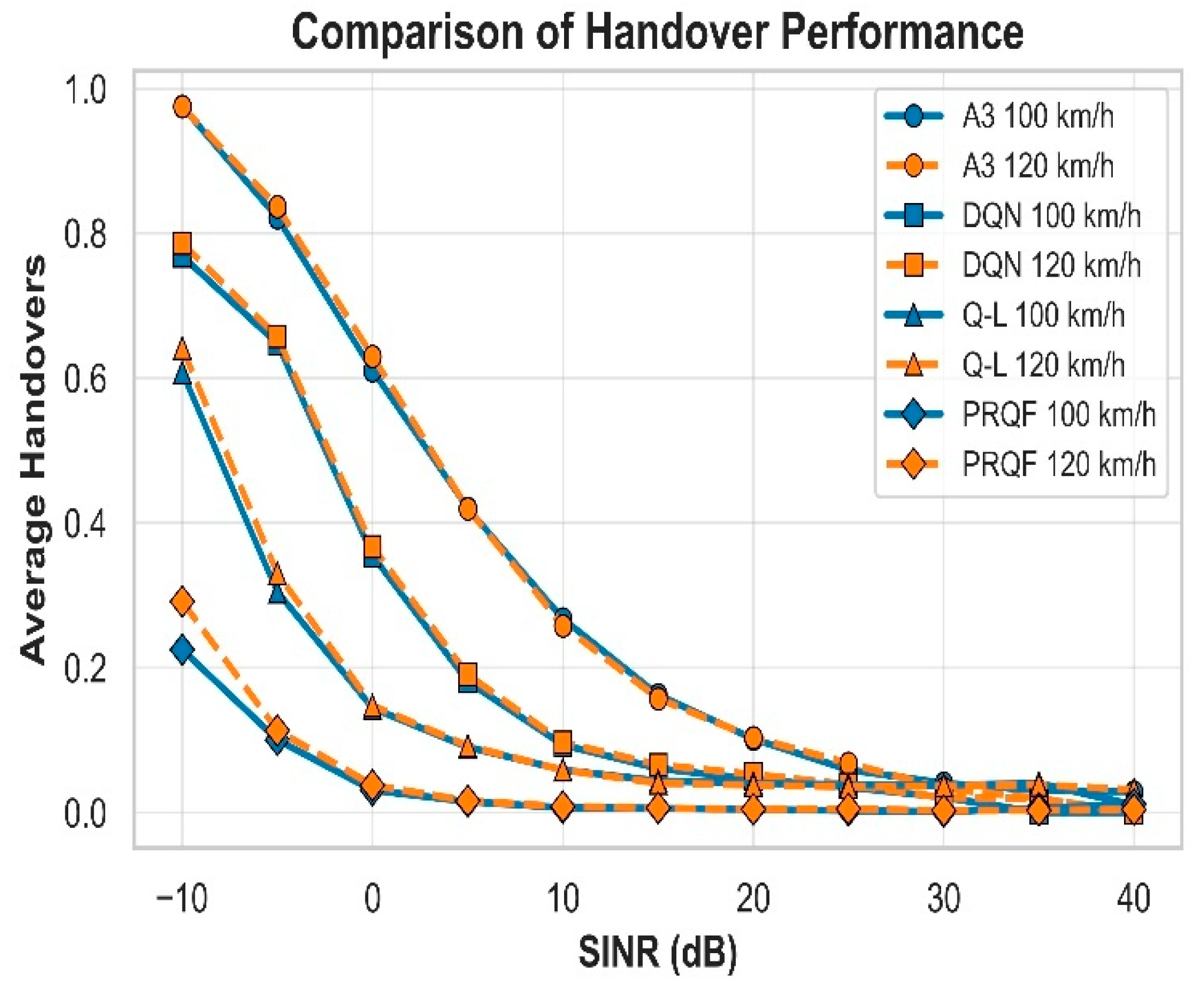

Figure 9 present the average handovers computed from all four UAVs combined, aggregated across a range of SINR bins under different mobility speeds and handover management strategies. In this plot, the

x-axis is divided into discrete SINR intervals (bins), allowing for a detailed comparison of performance at various signal qualities. The average handovers metric, calculated as the mean number of cell transitions per time interval within each SINR bin, serves as a direct indicator of network stability and connection quality. Lower average handover values correspond to more stable connections and fewer interruptions, highlighting the effectiveness of the handover management strategy. The proposed PRQF approach achieves the highest reductions, with an average decrease of 84% at 100 km/h and 83% at 120 km/h as shown in

Figure 9.

This indicates that PRQF substantially limits unnecessary handovers, improving network stability across varying signal conditions. The Q-learning component of the proposed method achieves moderate reductions, with 69% at 100 km/h and 67% at 120 km/h. These values demonstrate that even without the full hybrid gating mechanism, Q-learning alone can significantly improve handover performance compared to conventional methods. In comparison, the DQN approach from recent literature [

25] achieves lower reductions of 58% at 100 km/h and 59% at 120 km/h. While DQN provides improvements over conventional A3-based handover strategies, its performance is notably lower than the proposed method, highlighting the added value of the Q-learning and PRQF hybrid framework.

The PRQF architecture consists of two essential components: an XGBoost-based predictive gating module and a tabular Q-learning agent. The XGBoost classifier was evaluated independently as a probabilistic handover predictor, while the Q-learning agent was assessed separately to establish its baseline decision-making behavior. Comparing the full PRQF framework with the Q-learning variant isolates the effect of the gating mechanism, which achieves additional reductions in unnecessary handovers and improves overall stability. Since XGBoost produces only probability estimates and does not consider long-term reward or handover cost, it cannot serve as a standalone control policy. The DQN baseline, as implemented in this study, relies on generic reinforcement learning exploration strategies and lacks mechanisms for handling noisy or rapidly fluctuating SINR conditions. This absence of targeted filtering increases the likelihood of over-exploration and unnecessary handovers. In contrast, the PRQF framework incorporates the XGBoost predictor as a gating module that limits exploration to high-confidence scenarios. The comparison between PRQF, Q-learning, DQN, and the conventional A3 method therefore provides a comprehensive and balanced assessment of the contribution of each component within the proposed framework.

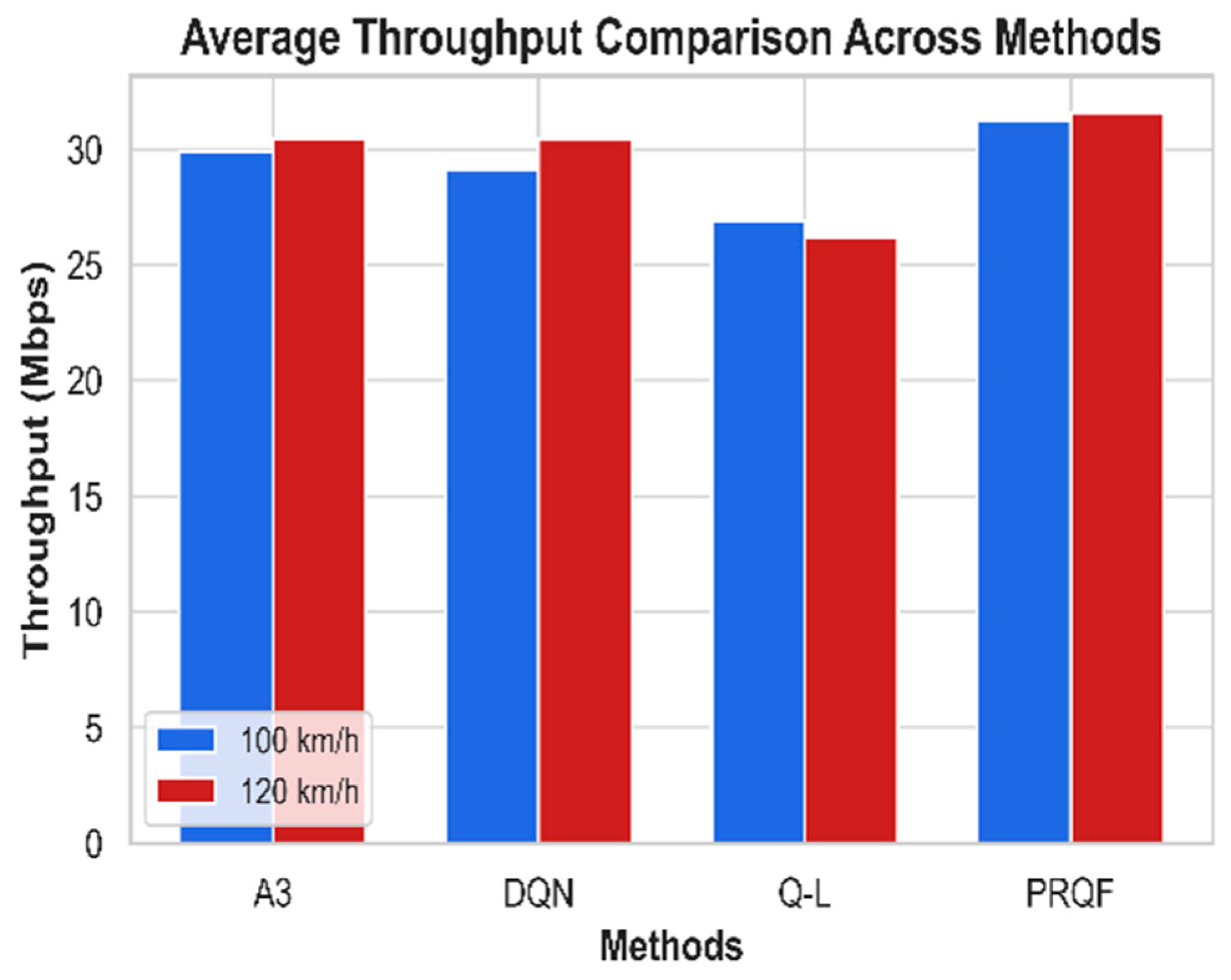

A comprehensive throughput analysis was performed to ensure that handover reduction does not compromise communication quality.

Figure 10 presents the average throughput of the four methods at 100 km/h and 120 km/h. PRQF achieves the highest performance at both speeds based on the mean throughput across all UAVs. It reaches 31.27 Mbps at 100 km/h and 31.60 Mbps at 120 km/h. The small difference across the two speeds shows stable behaviour under mobility. A3 and DQN show moderate performance. A3 records 29.90 Mbps at 100 km/h and 30.45 Mbps at 120 km/h. DQN is slightly lower at 100 km/h with 29.15 Mbps but improves to 30.42 Mbps at 120 km/h. Both methods remain close to each other and follow a similar trend as speed increases. Q-L gives the lowest throughput among the four methods. It achieves 26.91 Mbps at 100 km/h and drops to 26.18 Mbps at 120 km/h. This shows reduced stability and weaker performance at higher speed.

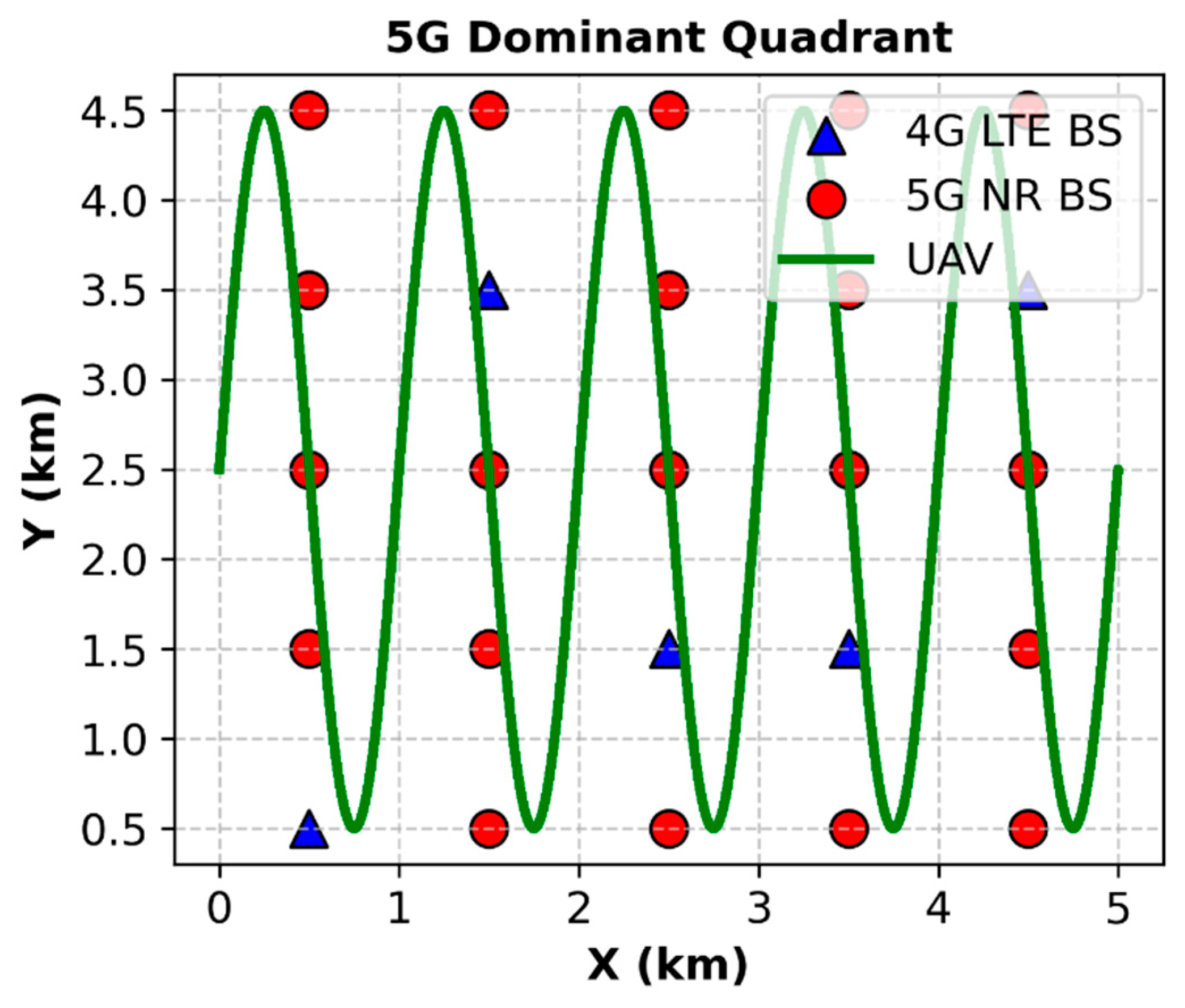

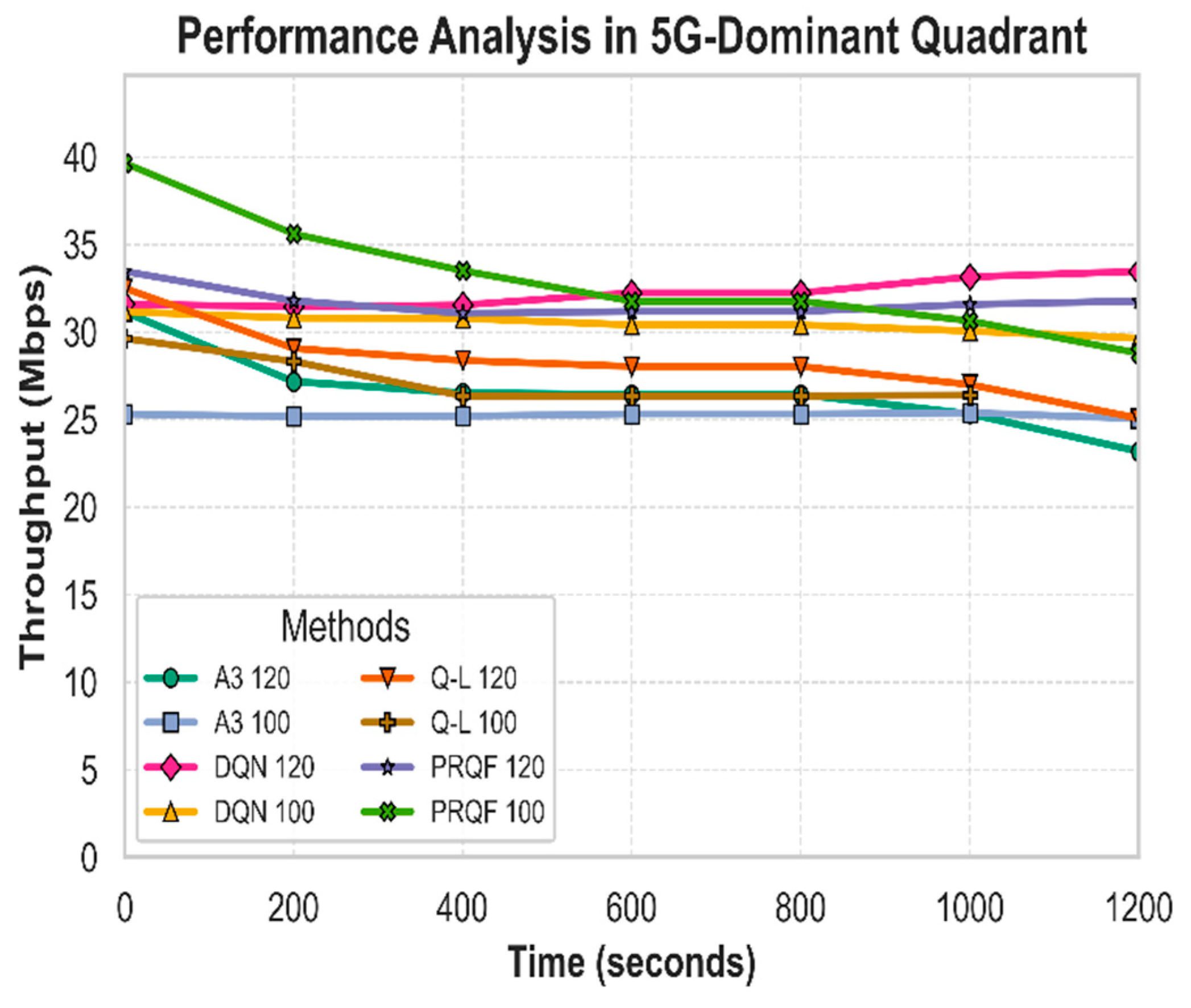

PRQF demonstrates the best combination of high throughput and minimal handover frequency, highlighting a clear trade-off advantage compared to other techniques. While some methods achieve throughput improvements at the cost of frequent handovers, PRQF maintains both link stability and high data rates, indicating that its hybrid adaptive filtering successfully balances these competing objectives. To further assess its robustness, PRQF is also evaluated in a 5G-dominant quadrant containing 20 5G NR base stations and 45 LTE base stations, as illustrated in

Figure 11. This scenario represents a substantially different deployment density compared to the balanced-density quadrants and introduces a far more handover-intensive environment due to denser NR coverage and more frequent cell-edge transitions. The same fixed XGBoost gating threshold (θ = 0.8) is retained in this setting to examine whether the gating behavior generalizes to a network with stronger signal fluctuations and higher handover opportunity rates.

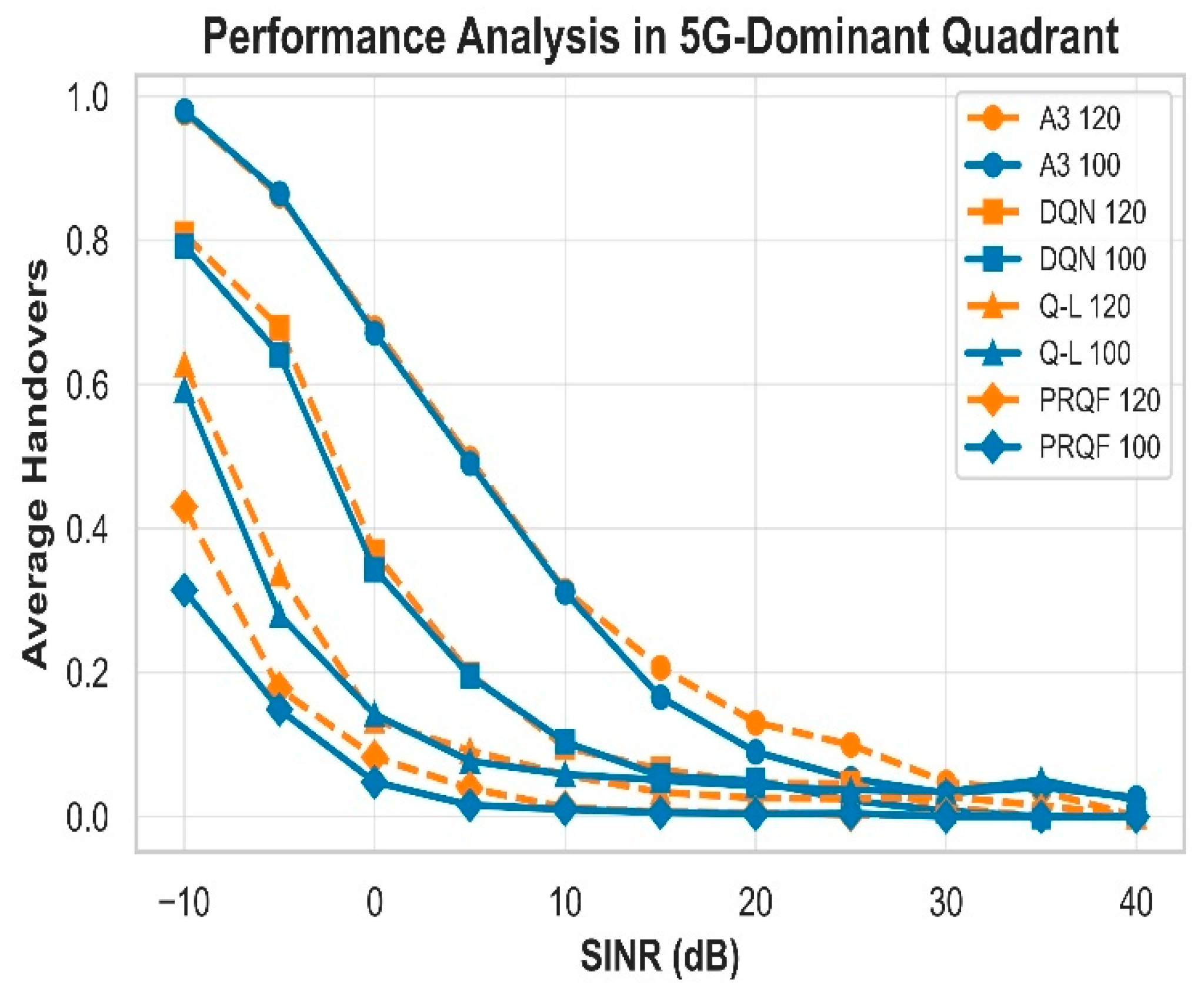

Under these conditions, PRQF continues to operate consistently, achieving the largest reductions in handover events relative to the A3 baseline: 80% fewer handovers at 100 km/h and 77% fewer handovers at 120 km/h (

Figure 12). The tabular Q-learning baseline attains reductions of 68% and 66% at 100 km/h and 120 km/h, respectively, while DQN shows 58% and 56% reductions. These results indicate that the selected threshold maintains robust gating behavior and effective handover suppression across both the original and denser deployment scenarios examined in this study. This consistency across deployment densities indicates that PRQF’s decision mechanism remains resilient to increased spatial heterogeneity and intensified beam-level and cell-level dynamics.

In addition to handover reduction, PRQF consistently achieves the highest throughput, reaching 39.65 Mbps at 100 km/h and 33.46 Mbps at 120 km/h, while DQN and Q-L deliver moderate performance, and A3 remains the lowest, as shown in

Figure 13. PRQF’s adaptive action filtering effectively reduces handovers and maintains high throughput in 5G-dense environments. However, the figure also shows that DQN surpasses PRQF at some of the later time points, where it provides better throughput compared to PRQF.

Table 6 summarizes the computational and operational characteristics of the evaluated methods. It reports key computational metrics, including simulation runtime, average inference time, and relative computational complexity, together with handover performance indicators such as handover latency and packet interruption time. Average inference time denotes the mean processing time required to generate a handover decision at each decision step and is measured at the controller side. Relative computational complexity is defined as the normalized computational cost with respect to the baseline A3 method and is derived from the combined simulation runtime and per-decision inference overhead. Packet interruption time represents the average duration during which data transmission is temporarily disrupted during a handover event.

As shown in

Table 6, PRQF incurs higher computational overhead than A3, Q-L, and DQN, as reflected by increased simulation runtime, average inference time, and relative complexity. This overhead results from the integration of predictive link-quality estimation and queue-aware decision mechanisms, which require additional feature extraction, model inference, and reinforcement learning updates at each decision step. Consequently, PRQF is more computationally intensive than reactive or lightweight learning-based approaches. In terms of handover-related performance, PRQF exhibits slightly higher handover latency and packet interruption time per handover event. This behaviour is expected, as PRQF prioritizes informed and forward-looking decision making rather than rapid reactive switching based solely on instantaneous signal measurements. By incorporating predictive assessments of link evolution and traffic conditions, the algorithm avoids premature or unnecessary handovers caused by short-term signal fluctuations.

Although per-event handover latency and packet interruption time are marginally higher, PRQF improves robustness and stability under dynamic UAV mobility conditions. The algorithm reduces decision oscillations and suppresses unnecessary handovers, thereby preserving long-term service continuity. Furthermore, PRQF jointly considers LTE and NR characteristics within a unified framework, enabling more reliable adaptation to heterogeneous network conditions and rapid changes in network load. Such computational overhead aligns with ongoing trends in 5G-Advanced and 6G networks, where AI-assisted mobility management and edge-based decision making are increasingly supported by dedicated computing resources [

55,

56]. The results indicate an explicit trade-off between computational overhead and handover performance. PRQF introduces higher computational cost and slightly increased per-handover interruption in exchange for enhanced decision stability, improved resilience to mobility-induced dynamics, and more consistent long-term link quality. While lightweight schemes such as A3 remain suitable for scenarios with strict processing constraints, PRQF is better suited for deployments where handover reliability and stability are prioritized over minimal computational overhead.

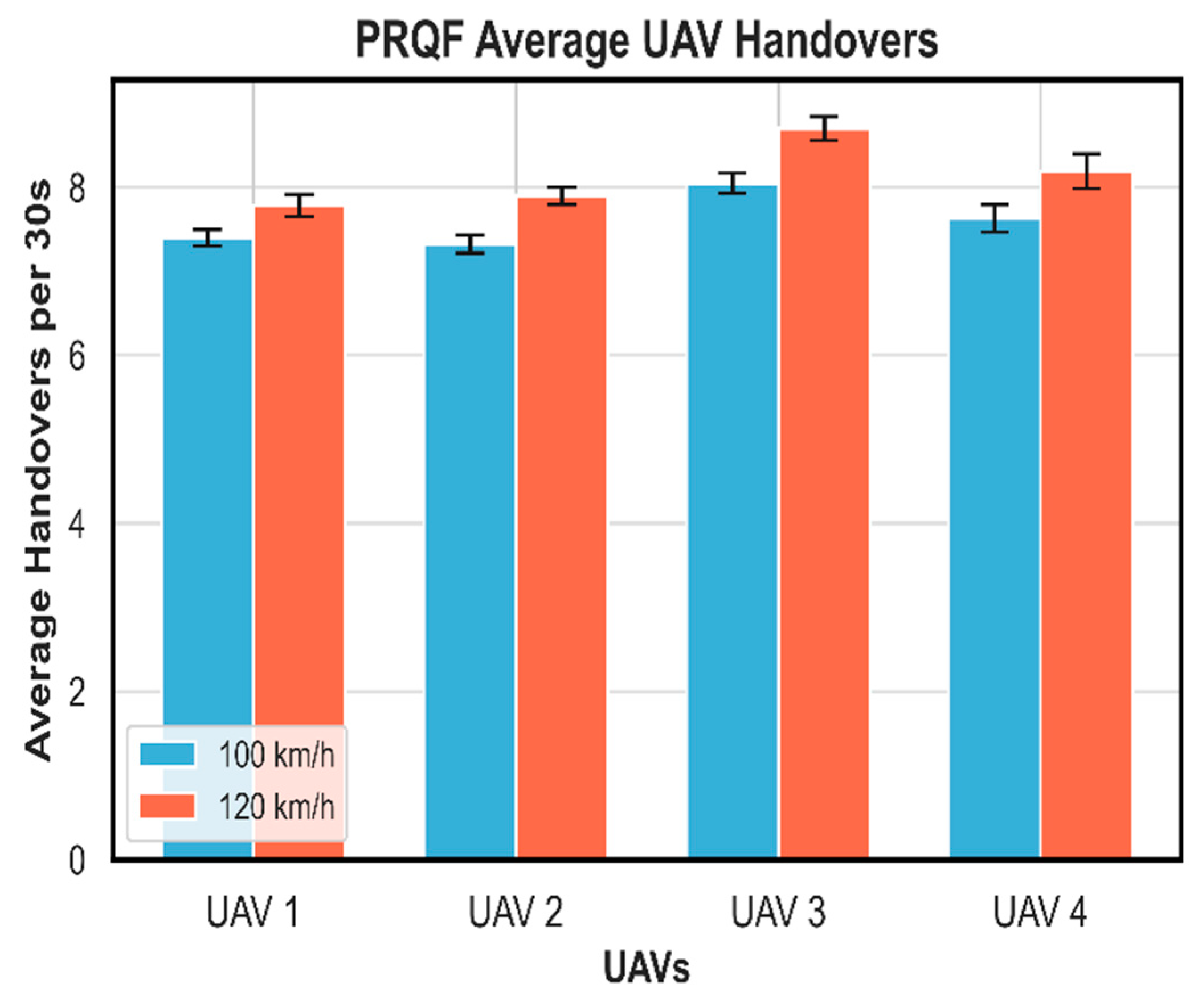

Multiple simulation runs are conducted to validate the stability of the results.

Figure 14 shows the average number of UAV handovers for PRQF, calculated over 30-s intervals and average across all runs, with error bars representing 95% confidence intervals. The trends remain consistent across UAVs, showing only a slight increase in handovers at 120 km/h compared to 100 km/h, which confirms the framework’s robustness under varying mobility conditions. These repeated simulations demonstrate that, despite fluctuations in network conditions, the proposed framework reliably reduces unnecessary handovers and maintains stable performance. Although the study considers four UAVs, the statistical consistency suggests scalability, indicating that performance is influenced more by local network topology than by the number of UAVs.

6. Conclusions & Future Research

This study introduces the PRQF, a hybrid intelligence approach that integrates XGBoost-based handover probability prediction with tabular Q-learning to enhance connectivity management for cellular-connected UAVs in dense urban environments. Deployed within a 10 km × 10 km heterogeneous LTE/5G NR network, the framework enables four UAVs to navigate sinusoidal trajectories at 100 km/h and 120 km/h while maintaining robust link quality. PRQF is evaluated against the standard A3 event-triggered mechanism, a deep Q-network (DQN) baseline, and a conventional tabular Q-learning model, using 3GPP-compliant Urban Macro propagation settings and 100 ms temporal resolution. The framework consistently outperforms all baselines across key performance metrics.

PRQF achieves an average handover reduction of 84% at 100 km/h and 83% at 120 km/h relative to the A3 policy, while sustaining better throughput across all methods and operating conditions. This improvement results from the probabilistic gating mechanism (θ = 0.8), which dynamically constrains exploration to high-likelihood handover scenarios, thereby minimizing unnecessary transitions without compromising responsiveness. The framework’s continuous learning paradigm, operating without episodic resets, enables the agent to capture long-term spatiotemporal dependencies in signal dynamics, yielding stable, high-quality connections even under rapid mobility and interference. Validation through repeated simulations confirms the reproducibility and scalability of these results, establishing PRQF as an effective solution for real-time aerial network optimization.

However, the study has certain limitations that shape its scope. The simulation assumes negligible inter-UAV interference, which is reasonable given the spatial separation and small number of UAVs but may not hold in denser deployments. Perfect position knowledge is assumed, using exact coordinates without considering localization errors from GPS or other onboard sensors. Although the tabular Q-learning approach demonstrates effectiveness for the current scenario, it may face scalability challenges with larger state-action spaces, more UAVs, variable altitudes, or complex urban layouts. The fixed 100 m altitude and sinusoidal trajectories simplify mobility and neglect vertical variations, irregular paths, or trajectory deviations that would occur in realistic missions. While these assumptions enable a controlled evaluation of PRQF, the impact of more diverse or adaptive UAV flight patterns on handover performance remains an open issue and will be addressed in future research. Finally, the controlled simulation environment does not account for dynamic factors such as urban obstructions, changing weather, or stochastic signal variations, which could affect handover performance in real-world deployments.

Future research will address these limitations to enhance realism and applicability. Multi-agent coordination strategies and distributed learning paradigms will be explored to manage denser UAV swarms and inter-UAV interference. Incorporating noisy position estimates through sensor fusion or robust state representations will improve robustness. Additionally, online, adaptive adjustment of the XGBoost gating threshold will allow the framework to dynamically respond to real-time variations in UAV speed, channel conditions, and handover likelihoods, further reducing unnecessary transitions and improving responsiveness. Transitioning to DRL approaches, such as DQN or D3QN, can handle high-dimensional state-action spaces more efficiently [

57]. The framework will also be extended to accommodate varying altitudes, irregular trajectories, and satellite-connected UAVs under constrained channel conditions, enabling 3D mobility and hybrid network operation [

58,

59,

60]. Future work will also examine the real-time feasibility and computational cost of the proposed framework to ensure scalability under practical deployment constraints. Finally, integrating real-time environmental factors, such as dynamic obstructions through raytracing, and conducting field trials with physical UAVs will validate performance in operational settings, paving the way for practical deployment in real-world heterogeneous networks.